Abstract

This article reports on a mixed-method research into the representation of source culture in an English language textbook series used at a major university in the Arabian Gulf. The current study utilized Ideology Critique Methodology and was framed within the Critical Research Paradigm. The research used a structured questionnaire, followed by open-ended questions administered to 30 purposefully chosen language teachers. The study attempted to ascertain, in the light of Muslim teachers’ perceptions, the representation of Islamic (and Saudi) culture, the extent of a multicultural outlook, and presence of any culturally inappropriate or offensive material in the contents of a most popular English language textbook series. The study endorsed the idea of appropriation of English according to variable contexts and opposed predominance of western culture in TESOL course books at the expense of local cultures.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The representation of English language learners’ own culture in their language textbooks and learning materials, side by side the Anglo-American culture and cultures of other countries in the world, has significant educational value. This study deals with the issue of cultural representation in a highly popular English language textbook series. It evaluates the representation of Islamic (and Saudi) culture in this textbook series in addition to the presence of any culturally inappropriate materials. It also considers the scope for the representation of other international cultures in English language textbooks to promote intercultural communication, which can gradually help reduce international political and ideological tensions. Highlighting the issue of (mis)representation of Islamic and Arab (Saudi) culture in a most popular English language textbooks, the findings of the study suggest that equitable representation of local cultures in English language textbooks can also have a motivational effect on English language learners.

1. Introduction

Let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend. (Mao-Tse-Tung)

“ELT has … lost its innocence” (Widdowson, Citation2004, p. 362). With these unkind words, Canagarajah (Citation2006) concluded his article, written on the 40th anniversary of TESOL Quarterly. With the loss of innocence, the steady march of TESOL has been checked by some intriguing questions. As the field has lost its innocence without losing its charm, it still enchants people all over the world with a qualification strongly desired, a profession highly valued, and an enterprise deeply entrenched. However, in this rapidly globalizing world, if TESOL has to move towards “an international family (as envisioned in the logo of the 25th anniversary [TESOL Quarterly] issue), it will not be in terms of the centre [Inner circle (Kachru, Citation1985)]. The international family will be achieved through mutual questioning, active negotiation, and radical integration” (Canagarajah, Citation2006, p. 29). In this spirit, we tried to find an answer to the question vigorously debated among TESOL professionals and academics (e.g. Canagarajah, Citation2006; Kachru, Citation1990; Lowenberg, Citation1993; Ngugi wa, Citation1986; Norton, Citation1997; Pennycook, Citation1994; Phillipson, Citation1992; Tollefson, Citation1991; Widdowson, Citation2004): Are we, the language teachers, being inadvertently used by multinational corporate interests, which are bent on weakening the cultural and linguistic resources of ESL/EFL learners in a manner that leads to “the carnage of local cultures” (Norton & Macpherson, Citation1997, p. 641)?

There are 1.8 billion speakers of English (as first, second, and foreign language) in the world, which divided by the estimated population of the earth, 6.6 billion, equates to about 27% (CIA World Factbook, July 2007 estimation). As Kachru (Citation1985) observes: “with its diffusion, English ceases to be an exponent of only one culture—the Western Judaeo-Christian culture; it is now perhaps the world’s most multicultural language, a fact which is, unfortunately, not well recognized” (p. 20). With an exponentially growing number of English learners, the TESOL industry is also massively expanding. According to The Times’ (2000) 18 years old estimates, the English language textbook industry alone is worth over £5,455 billion (Mahboob, Citation2011). In this rapidly flourishing industry, the Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, represent a considerable proportion of the market. As the policymakers in the Arabian Gulf have acknowledged the English language as a vital necessity for development and modernization, Saudi Arabia has given privileged status to English language teaching in educational institutions across the country (Syed, Citation2003). During the last decade, the number of English language learners has greatly increased in the kingdom and English is also introduced at primary level. However, what remains critically uninvestigated, in this context, is the textual representation of the culture of (Saudi) Muslims, who are being influenced by the globalization of English with far-reaching implications. In this marketing and industrialization of English, we must be aware and wary of attempts (inadvertent or deliberate) at “colonization of the mind”, by way of explicitly or implicitly presenting only western norms, values, traditions, and practices in textbooks (Mahboob, Citation2011).

Given the crucial role of the nature of cultural representation in TESOL resource materials, we decided to undertake a small-scale research study in order to critically evaluate a popular language textbook series published by a renowned British publisher, which has been used at an English language institute of a Saudi University for five years as a main syllabus resource. While examining the contents of these textbooks, we were intrigued by the absence of material relevant to students’ source culture, which, in general, is identified with Muslims all over the world. If at all, any attempts were made to create relevance to the Saudi local culture and diverse international cultures, they were either insignificant or merely cosmetic. Our initial findings compelled us to further investigate the issue by involving our colleagues in this study. Consequently, we engaged 30 of the Muslim faculty members and collected data from them in order to corroborate our preliminary assumptions about the representation of source culture and international cultures in this textbook series.

In a nutshell, the present study attempted to ascertain, in the light of Muslim teachers’ perceptions, the representation of Islamic (and Saudi) culture, the extent of an international cultural outlook, and the presence of any culturally inappropriate or offensive material in the contents of a most popular TESOL textbook series.

1.1. The context of the study

The roots of English language in the Middle East and the Arabian Gulf can be traced back to the Colonial period in the early 19th century (Weber, Citation2011), but in Saudi Arabia (KSA), English language teaching first began as a high school subject in the late 1950s (Al-Haq & Smadi, Citation1996). However, a major shift in the status of English language in KSA came with the post 9/11 (2001) political scenario when the English language was acknowledged, probably under social and political pressure from some quarters, as a necessity for development and modernization in the country, declaring it a compulsory subject across all school levels (Mahboob & Elyas, Citation2014). With the privileged status of English as a compulsory foreign language in the country already established, the launch of the late King Abdullah’s vision 2020 for his country in 2007 led to the adoption of English as a medium of instruction for all science departments in the Saudi universities. As a result, these universities have established new English language departments, institutes or centres to run a Foundation Year Programme (FYP) with a major focus on TESOL. The site of this study is a big English Language Institute (ELI), which caters to the EFL needs of about 7000–8000 university students each year. The ELI has a faculty consisting of above 200 English language instructors hailing from different parts of the world. A clear majority of the faculty comprises Muslims or Western-Muslim convert teachers. The Mission of the ELI is to provide intensive instruction of English as a Foreign Language to Foundation Year students in order to enhance their English language skills and facilitate their academic progress. The foundation year is split into four quarters of seven weeks each. In each quarter, one student textbook and a workbook have to be covered following a tight weekly pacing schedule. At the end of each quarter, successful students are promoted to the next level. Following the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), the ELI offers courses starting from Beginner (A0) to Intermediate (B1). The textbook series critiqued in the current research has been used as a main syllabus resource for five academic sessions. In the second year, a Special Edition of the series came out, which is a (slightly) modified version of the international edition of the textbook series. The special edition mainly aimed to make the course books more suitable for the “conservative” environment of Saudi Arabia.

2. Theoretical framework

The current study is designed within the ambit of the Critical Research Paradigm, which aims to challenge the existing social order and cultural practices in favour of the underprivileged, by taking an activist stance—with action as a goal of research (Habermas, Citation1984). In practice, this paradigm envisages researchers to be transformative intellectuals who liberate people from their historical, mental, emotional, and social situations (Crotty, Citation2003; Guba & Lincoln, Citation1994). The current research intends to problematize “Culture” in language teaching—an important domain in Critical Applied Linguistics (CALx). Pennycook (Citation2001) states:

CALx … involves a constant scepticism, a constant questioning of the normative assumptions of applied linguistics. It demands a restive problematization of the givens of applied linguistics, and presents a way of doing applied linguistics that seeks to connect it to questions of gender, class, sexuality, race, ethnicity, culture, identity, politics, ideology and discourse (p. 10).

Pennycook (Citation2004) identifies transformative pedagogy—a teaching approach that hopes to bring a positive change in any given situation—as one of the main features of CALx. As CALx challenges the overriding presence of the cultural norms and values of the Inner Circle countries in TESOL course books, this study also examines the phenomenon of the promotion of certain cultures and marginalization of others.

3. Literature review

3.1. Emergence of English as an International language (EIL)

It might smack of callousness, but it is a fact that the World Wars, which brought so much death and destruction to the people of Europe, proved to be a blessing in disguise for the countries colonized by the British Empire. The Empire, weakened by vagaries of the Wars, was left with no option but to change its colonial control strategy from coercion to consent (Fairclough, Citation1989). Physical control over the lives of the colonized had become too expensive and risky to manage, which eventually led to the invention of new measures for implicit and mental forms of colonization. One aspect of this new strategy was the dominance of English and ELT, which Pennycook (Citation1994) calls a product of colonialism and Phillipson (Citation1992) describes as linguistic imperialism, aimed at imposing “its own cultural values, military and economic power, wants and needs upon the periphery through TESOL and so-called ‘aid’” (Phan Le Ha, Citation2008, p. 72).

In any case, there is no denying the fact that English has acquired the status of a dominant international language (Crystal, Citation2003; McKay, Citation2003a; Seidlhofer, Citation2003). “For better or worse, by choice or force” (Sharifian, Citation2009, p. 1), English has spread far and wide and is being used for multifarious purposes. On the one hand, it plays a hegemonic, schismatic, and marginalizing role in certain societies (e.g. former British colonies like Pakistan and India); on the other, it is an empowering tool for those who are destined to or desirous of acquiring proficiency in it. In some contexts (e.g. Pakistan), excellent ability in the English language will ensure a good job, a higher social standing, and thereby prosperity in life (Rahman, Citation2002). In other places, it can be utilized to serve a different purpose. During our teaching career in Saudi Arabia, we have encountered a number of students who, not in the least attracted towards the culture of the inner circle countries, were learning English for the purpose of using it as a means to spread the message of Islam worldwide. Without doubt, the status of English as an International Language (EIL) gives its speakers the right to appropriate the language for their own purposes (Canagarajah, Citation1999). Sidhwa (Citation1996), a renowned Pakistani novelist, contends that “English … is no longer the monopoly of the British. We, the excolonised, have subjugated the language, beaten it on its head and made it ours” (p. 231). It is worth stating that the rapidly globalizing world has paved the way for the emergence of the new paradigm of English as an International Language (EIL). Composed of the inner and outer circles of English varieties described in Kachru’s model, EIL aims to lend space to the cultural norms and values of EFL/ESL learners across the world (McKay, Citation2002). Hence, Seidlhofer (Citation2003) rightly believed that EIL would soon include countries from the expanding circle due to its speedy spread across the Globe.

3.2. Culture and TEILFootnote1/TESOL

Culture in language learning is not an expendable fifth skill, tacked on, so to speak, to the teaching of speaking, listening, reading, and writing. It is always in the background, right from day one, ready to unsettle the good language learners when they expect it least, making evident the limitations of their hard-won communicative competence, challenging their ability to make sense of the world around them (Kramsch, Citation1993, p. 1).

The term Culture is quite elusive in its scope and nature. Hinkel (Citation1999) has summed up this problem as such: There are “as many definitions of culture as there are fields of inquiry into human societies, groups, systems, behaviours, and activities” (p. 1). In a TESOL context, culture can be delineated in the following two key strands: a) Culture as a heritage product which includes religion, history, great figures of history, festivals, literature, art, etc.; b) Culture as a community of practice which represents traditions, legends, folklore, popular music, dress codes, patterns of behaviour, food, etc. (Beaudrie, Ducar, & Relaño-Pastor, Citation2009; National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project, Citation1996).

The research in the later part of the 20th century has amply testified to the fact that whether culture is taught implicitly or explicitly, it cannot be dispensed with due to its inherent presence in the language learning context (Byram, Citation1997; Cook, Citation1999; Cunningsworth, Citation1995; Kramsch, Citation1993; Liddicoat & Scarino, Citation2013). Hence, the question is not whether Culture should be taught, rather how it should be presented and taught (Nault, Citation2006). Byram (Citation1989, p. 3) believes that culture teaching should have “a rightful place” in language teaching and it should not look like something “incidental to the real business of language teaching.” The EIL paradigm strongly emphasizes learners’ understanding of their own culture, because that will help them develop an understanding of the target culture and other international cultures (McKay, Citation2002). Likewise, Stern (Citation1992) also stresses the need to acquire “knowledge about the target culture, awareness of its characteristics and differences between the target culture and the learner’s own culture” (p. 212).

The Post-Modern perspective, in the TESOL context, re-signifies culture as a concept referring to “Discourse, Identity, and Power” (Kramsch, Citation2004). Discourse means a “way of using language, of thinking, feeling, believing, valuing, and of acting that can be used to identify oneself as a member of a socially meaningful group or ‘social network’” (Gee, Citation1990, p. 143). Identity signifies “how people understand their relationship to the world, how that relationship is constructed across time and space, and how people understand their possibilities for the future” (Norton, Citation1997, p. 410). A post-modern perspective not only considers all cultures to be of equal worth but also declares that they are objects of moral and ideological struggle. The recent ban on Muslim schoolgirls wearing headscarves in France highlights the issue of moral and ideological rights being questioned, which led to struggles for identity rights among Muslims (Taylor, as cited in Kramsch, Citation2004). In view of these developments, Hansen (Citation2004) argues for a redefined role of culture: “Foreign Language Studies must learn to conceive of culture as an open, multi-voiced, and dialogical interaction full of contradictions, rather than as the deterministic, homogeneous, and closed structure that belonged to the era of the nation-state” (p. 9).

In TESOL context, Cortazzi and Jin (Citation1999) have proposed a balanced approach to cultural representation in language textbooks and resource materials. They argue for a three-dimensional approach in language textbooks and resource materials which can lead to successful intercultural communication (see ). The first is a representation of the source culture, drawing on learners’ own culture as content which they are already familiar with. The second should be target culture materials based on the culture of a country where English is spoken as an L1. The third segment of cultural materials should be derived from the international target culture, which includes a great variety of cultures of English and non-English speaking countries around the world (McKay, Citation2003b).

C1 refers to source culture, C2 denotes target culture, and C3, C4, and C5 stand for a variety of cultures in different parts of the world (Aliakbari, Citation2004).

3.3. Representation of Islamic (and Saudi) culture in TESOL/TEIL

There are around 1.6 billion Muslims in the world, which is about 23% of the world population (Pew Research Centre, Citation2011). Unlike secularized Christendom, where religion has been relegated to the position of an exclusively personal affair, Islam plays a major role in various spheres of Muslims’ lives (Troudi, Citation2005). Culture, in general, affects our way of life, but Islamic culture particularly influences the thoughts and actions of its adherents, from what they eat and drink to what they believe and practise to how they conceptualize and understand the world around them (Schmitt, Citation2009).

Hinkel (Citation1999) argues that learning or teaching a second or foreign language without paying attention to the culture is hardly accomplished. In a similar vein, Rich and Troudi (Citation2006, p. 616) underscore TESOL practices as “neither value-free nor apolitical.” Therefore, TESOL practices which tend to perpetuate “a colonial discourse of inferiorizing, marginalizing, and excluding” certain cultures, religions or creeds have far-reaching effects leading to further racialization and schism in the globalizing world (Van Dijk, as cited in Rich & Troudi, Citation2006, p. 617). However, such regressive trends in TESOL still continue in one way or another. As the English language has gained further ground in the Middle East, particularly after the second Gulf war, the effect of Western culture upon the cultural identity of young Arab Muslims is easily observable. According to Zughoul (Citation2003), a major factor responsible for this trend is the TESOL course content exported to Middle Eastern countries from the UK and the USA.

3.3.1. Islamic and Saudi cultural commonalities

Notwithstanding the variety of and differences between Muslim cultures, there are numerous similarities and important shared aspects of Muslim culture which have existed with little change through the centuries (Schmitt, Citation2009). For the Muslims all over the world, the culture is influenced by the fundamental beliefs that there is no God but Allah and that Muhammad (peace be upon him) is His messenger. For Muslims, the life and character of the Prophet Muhammad inspire not only profound reverence but passionate and unconditional love that reinforces their Muslim identity. According to Lewis (Citation2003), Islam is not only a matter of faith and practices; it is also an identity and loyalty. Undoubtedly, Islam plays a central role in worldly affairs, social rituals, and beliefs of Muslims. The Quran is considered to be the source of many aspects of Islamic culture. Festivals like Eid ul-Fitr, Eid ul-Adha, Hajj and Lailat al Miraj (The Night of Ascension) are classic examples of the influence of religion in the lives of Muslim people (Borade, Citation2012). In more specific terms, the collective identity of Saudis and most Muslim Arabs may be defined as having three elements: the Islamic, the Arab, and the tribesman (which in the narrow, local sense consists of traditional factors such as tribe, extended family or geographical region) (Nevo, Citation1998). However, considering itself the leader of the Islamic world, Saudi Arabia has expended tremendous efforts in inculcating the fundamental Islamic beliefs, religious practices and values in the Saudi Muslims as well as Muslims all over the world. Schmitt (Citation2009) has wisely observed:

The very fact that one can talk about Muslims, rather than Arabs, Turks, or Africans, indicates that religion plays a significant role in society. Religion in the Muslim world is widely viewed as a positive thing, integral to social harmony and supportive of stability and unity. It is often also viewed as more public than it is in the secular West or in East Asia. This leads to an emphasis on both a relationship with God and morality. Thus questions of both day-to-day living and more general philosophical issues are heavily influenced by religious thought. For example, any visitor to a Muslim nation is reminded of this by the Adhan, or the call to prayer, five times a day, and even secular Muslim nations generally have more legal restrictions on issues viewed as personal moral issues in the West, such as pornography, homosexuality, and abortion (p. 2).

The above quote cogently sums up the foregoing discussion about the commonalities of Islamic culture ingrained in the lives of Muslims in general and Saudi Muslims in particular where the practice of religious beliefs and rituals is highly appreciated and monitored.

3.3.2. Intercultural communication (to dilute islamophobia)

The EIL paradigm also conceives of English as a means to promote intercultural communication. Not only that, Byram and Wagner (Citation2018) argue that “language educators need to make a conscious decision to teach languages for intercultural communication” (p. 147). Intercultural communication is defined as “communication on the basis of respect for individuals and equality of human rights as the democratic basis for social interaction” (Byram et al., Citation2002, p. 9). Intercultural communication aims to facilitate interaction with people of other cultures, promote understanding and acceptance among people from varied cultures, and check the human tendency to stereotype people (Kilickaya, Citation2004).

In a world haunted by global terrorism, nuclear weapons, and Islamophobia, with debates raging on the theory of “The clash of civilizations” with a renewed vigour (Huntington, Citation1996), intercultural communication can play a vital role in reconciling mutually antagonistic cultures that are bent on exterminating each other. Payne (Citation2006) posits that the Quran expounded, 1400 years ago, the idea of intercultural communication:

O humankind, We created you from a single pair of a male and a female and made you into nations and tribes, that you may know each other (The Quran, 49:13).

As getting to know each other certainly requires learning languages, Prophet Mohammed asked Zayd, one of his companions, to learn the language of the Jews for Him. Prophet of Islam, later on, used Zayd’s language skills to communicate with the Jews. Payne (Citation2006) asserts that awareness is central to greater mutual understanding of each other. As TESOL professionals, we must challenge popular stereotypes about different cultures, and endeavour to discover shared viewpoints and mutually beneficial goals through intercultural communication. Therefore, culture in TESOL can be an illuminating factor (Schmitt, Citation2009), which can quell the fear of a “clash of civilizations” (Islamic vs. Western), and contribute to better understanding of different cults, creeds and religions if it is wisely handled giving fair representation to C1, C2 and C3, C4, C5.

3.4. Previous research on cultural representation in English textbooks in the Saudi context

We searched thoroughly through the available research databases for studies undertaken on English textbooks taught in Saudi Arabia, and found some master’s level theses and unpublished papers on textbook evaluation in the Saudi context, but we felt obliged not to cite them because they were either quite restrictive or less rigorous as regards the nature and scope of their research. However, we came across one significant work in the area of textbook evaluation which was partially relevant to our topic. Al-Hijailan (Citation1999) evaluated the third grade English textbook titled: “English for Saudi Arabia” for his PhD thesis. He investigated the quality of the third-grade secondary textbook vis-à-vis course objectives set by the Saudi Ministry of Education. He also evaluated the representation of culture in this textbook and found that even though the textbook did not fully match the objectives set by the Ministry, learners’ source culture was appropriately employed, which made learning English easier, faster, and more interesting.

4. Research questions

In line with the aims of the current study to evaluate the representation of Islamic (and Saudi) culture, the presence of any culturally inappropriate or offensive material, and the extent of an international cultural outlook in the contents of a most popular TESOL textbook seriesFootnote2, in light of the perceptions of Muslim teachers working at the research site, we endeavoured to answer the following research questions:

How is the Islamic (and Saudi) culture represented in the compulsory TESOL course books used at a Saudi Arabian university?

What cultural values and traditions are mainly represented in these course books?

To what extent do these course books promote intercultural communication?

5. The study design

5.1. Methodology

“The starting point of the critique of ideology has to be a full acknowledgment of the fact that it is easily possible to lie in the guise of truth”, says Zizek (Citation2012, p. 8). In line with critical research paradigm, the current study used ideology critique methodology; the primary goal of which is “to discover and make visible the dominant ideology or ideologies embedded in an artefact and the ideologies that are being muted in it” (Foss, Citation2009, p. 295). Ideology critique also attempts to liberate us from self-deception, false consciousness, and deceitful manoeuvres by countering powerful groups who promote and legitimize their particular interests at the expense of others (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2007).

5.2. Participants and sampling

The research study participants were selected from the male Muslim teachers (Muslim convert native English speakers and non-native Muslim English speakers) working at the English Language Institute of a Saudi Arabian University. They were all qualified and experienced language teachers. Their total TESOL experience ranged between 5 to 22 years approx., and their minimum experience in the Saudi TESOL context was at least 3 years. The sample consisted of 30 Muslim teachers hailing from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Syria, Pakistan, India, Canada, the UK, and South Africa. We used purposive sampling for the current study in order to access the Muslim teachers who seemed to have considerable experience in the field of TESOL, good knowledge of Islamic cultural heritage and Saudi Arabian cultural values and norms, and a thorough familiarity with the contents of the English textbooks used in the research context. Purposive sampling is a non-random selection of research participants, based on their qualities or knowledge, helpful in advancing understanding of the subject under research. We considered purposive sampling the most suitable for the current study, as it facilitated the collection of in-depth information from those who were in a strong position to impart it (Cohen et al., Citation2007).

One obvious caveat in the selection of participants for the study is the absence of female teachers’ voices, which also raises the issue of equitable gender representation in the research. In fact, the data for this study are collected only from male participants primarily due to constraints dictated by the conservative nature of the research context where mixing of unrelated men and women is strictly forbidden, precluding the inclusion of female faculty’s voices in the data.

5.3. Data collection instruments

The study utilized a mixed-method approach. A two-part instrument, comprising a closed-ended questionnaire (Part One) and six open-ended questions (Part Two), was used for data collection (see Table & Appendix 1). Kilickaya (Citation2004) developed useful guidelines for the evaluation of cultural content in textbooks for English as an international language, considering sociocultural factors, intercultural communication, learners’ needs, hidden curriculum, generalizations, and dissemination of inappropriate cultural information. Consistent with the conception of culture in the current study, Kilickaya’s (Citation2004) “Guidelines to Evaluate Cultural Content in Textbooks” were partly adapted in the data collection instrument. Overall, the data collection instrument was developed on the basis of a broad literature review on the chosen topic. It incorporated some of the most pregnant themes discussed and debated by renowned scholars in the field of critical applied linguistics and TESOL (e.g. Canagarajah, Citation2006; Kachru, Citation1990; Ngugi wa, Citation1986; Norton, Citation1997; Pennycook, Citation1994; Phillipson, Citation1992; Widdowson, Citation2004). The study also considered the significance of the representation of Islamic culture in TESOL in post-9/11 global political scenario. Part One of the questionnaire comprised six statements to be evaluated on the Likert scale. The participants were requested to indicate their level of (dis)agreement by putting a cross (X) in the appropriate box. Part Two contained six open-ended questions on the research topic and an option for the participants to share any thoughts or ideas on the subject.

Table 1. Frequency Distribution of Participation Responses in Percentage

Questionnaires are one of the most frequent instruments for data collection in educational research (Oppenheim, Citation1992), and these are particularly useful for establishing opinions (Cohen et al., Citation2007). However, according to several research studies, self-reporting questionnaires are not entirely reliable, and can sometimes lead to incomplete understanding of the situation (see McDonald, Citation2008). More importantly, considering Pintrich and Schunk’s (Citation2002, p. 11) emphasis on the value of doing qualitative research “for raising new questions and new slants on old questions”, we collected data through a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. Hence, the qualitative, open-ended questions afforded us the opportunity to understand the situation from the teachers’ point of view in a non-controlling and open way (Patton, Citation2002) and build up rich and elaborate descriptions of the phenomena under study (Ernest, Citation1994).

5.4. Quality and rigour of the research

The “scientific holy trinity” of validity, reliability, and generalizability are contested terms in the field of qualitative, interpretive research (Kvale, Citation1995, p. 20). Some researchers, such as Mouton (Citation1996), tend to gauge the reliability and validity of qualitative research in ways similar to quantitative research; others, like Eisner (Citation1998), reject this notion and argue that reliability and validity are incompatible with qualitative research. In this regard, Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985, p. 219) propose a parallel term trustworthiness to substitute validity and reliability. The trustworthiness of a research embodies four aspects comprising credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability (see Shenton, Citation2004). These criteria have been widely appreciated and some recent publications have advocated the implementation of these terms in qualitative research (Bryman, Citation2008).

For credibility (truth and value) of the current research, we have used a mixed-method approach employing credible tools for data collection and presented a clear rationale for our choice. Moreover, we have had prolonged engagement and familiarity with the research context. For dependability (consistency or reliability) and confirmability (accuracy and neutrality), we have provided an audit trail in the form of details of methodological and procedural decisions in sections 5.3 and 6 and discussed the ontological and epistemological assumptions of the study in sections 2 and 5.1. For transferability (generalizability/applicability of findings to similar contexts), we have provided details of the research context and presented thick descriptions of the phenomena under study in an effort to create scope for teachers in similar contexts to connect their own experience with the import of our study.

Upholding the highest standards of ethical research practice, we abided by all the necessary ethical conventions in the course of data collection. We obtained permission from the relevant authorities to conduct our research on the site. All the participating teachers were given detailed information about the objectives of the study. Participation in the research process was voluntary and the participants were briefed about their right to withdraw from the research at any time. Furthermore, they were assured of total anonymity and confidentiality in the whole process of the research.

6. Data analyses

Survey Questionnaire data (Part One) were analysed with the help of descriptive and exploratory statistics (Cohen et al., Citation2007), distributing the frequency of the participants’ responses into percentages in a multi-column table (see Table ). The quantitative data helped decipher the major trends in the data and form a general opinion about the phenomena under investigation. However, to inform the research questions with a deeper understanding of the matter under research, we conducted a thematic analysis of the qualitative data collected through the open-ended questionnaire.

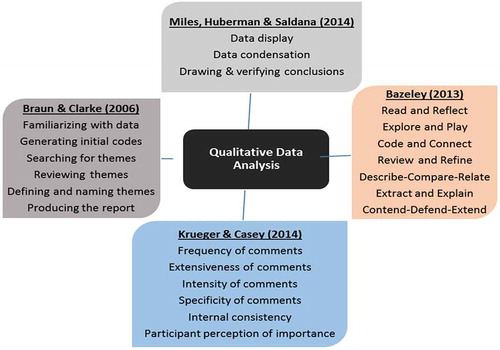

Until the last few years, thematic analysis was considered a fluid and loosely-demarcated approach, despite the fact that the first magisterial work “Qualitative Data Analysis” by Miles and Huberman was published in 1994, laying down elaborate and systematic procedures for coding and thematic data analysis. Nevertheless, some recent high-quality publications on the subject by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), Bazeley (Citation2013), Miles, Huberman and Saldana (Citation2014), and Krueger and Casey (Citation2014) have tremendously contributed to the strength of thematic analysis in qualitative research (see Figure ).

For the current study, Miles et al.’s (Citation2014) framework for qualitative data analysis was mainly utilized, which consists of three simultaneous flows of activity: data display, data condensation, and conclusion drawing. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step guide for thematic analysis of the qualitative data was also considered to add further vigour to the data analysis process. Notwithstanding the fact that our broad literature review influenced our coding process, we endeavoured to follow an inductive and iterative approach throughout the data analysis process. First, vital information in the data was highlighted. Second, the key points of the data were carefully perused and inductively coded. Third, the coded data were condensed into 42 loose categories and transferred into a matrix. Finally, after much deliberation, these categories were collapsed under five major themes in order to facilitate interpretation and further conceptualization of the crucial issues that emerged in the process of data analysis.

7. Findings and discussion

7.1. Quantitative data: revelations

The findings of the closed-ended questionnaire are presented in Table and a brief discussion of the quantitative data is given below:

In terms of representation of Islamic culture in the course book series, not a single teacher agreed that it represented Islamic culture in any way. The results about the presence of Saudi culture in this series were no different, with 90% of the teachers disagreeing with the statement, while 10% remained neutral on this issue. The first two findings spoke volumes about a disregard for Islamic and Saudi culture in these course books. Conversely, 90% of the teachers believed that these books reflected the western culture of inner circle countries, which testified to the predominance of western culture, presumptively, at the expense of local culture. Only 30% of the teachers thought that these books included material (although superficial in nature, see details below) on a variety of cultures from different parts of the world, which implicitly reflected a mindset that considered the culture of inner circle countries as superior and more civilized. As far as cultural sensitivities in terms of material being inappropriate and offensive are concerned, the majority of the teachers seemed satisfied with the special edition of the course book series, which definitely made the book more acceptable and marketable in the “conservative” Arab country. Only 23% of the teachers were of the view that the series contains some culturally inappropriate or offensive material. The fact that merely 10% of the teachers assumed that these books promoted intercultural understanding indicated that the publishers/authors were least concerned about intercultural communication, so vital in this globalized world haunted by various phobias.

7.2. Qualitative data: major themes

A concise discussion of the major themes and sub-themes that emerged from the data is set forth below:

7.2.1. A disregard for Islamic (and Saudi) cultural representation

The modernization agenda envisages that “underdeveloped” nations must do away with their religious and traditional institutions and adopt ways of “modern” industrialized countries in order to be recognized as developing or developed countries (Tollefson, Citation1991). This mindset is usually inherent in technological and educational materials exported to the “backward” and “conservative” Islamic countries. The TESOL coursebook series being critiqued in the current study also seem to be influenced by the modernization theory. Considering the culture of Muslim Arab countries as antiquated and regressive, its representation in the course book series is completely disregarded. As observed by some of the participants:

The books do not reflect an Islamic country’s culture at all except very few photos of Arab people in Arab/Saudi dress. They do not talk about festivals, everyday life or pastimes of an Islamic country. They are completely unsatisfactory. There is very little or no representation of the Saudi Arabian culture with reference to their food, festivals, young generation and their aspirations, and Saudi family system, etc. (T 7).

I strongly disagree that these course books give any regard to Islamic culture. Apart from a few pictures from the Arab world and some Muslim names, it does not give any importance to Islamic culture. Changing the pictures and names does not mean that the culture of the target community is adequately represented (T 12).

However, one can find some Islamic names and a few pictures of women in abayas [long gowns] and headscarf, which is superficial and cosmetic in its nature and apparently done to make the book more marketable in an Islamic country. The use of such decorative strategies was highlighted in these words:

This course book series pays only that much attention to Islamic culture so as to make it marketable in the Saudi context (T 20).

I don’t think there’s anything Islamic in these course books. To show one or two pictures of a lady with the headscarf and to throw in a few Arabic names are not sufficient to be considered Islamic culture (T 13).

The same thread was picked up by yet another participant:

I do not believe that the books really give any importance to the Islamic culture. There is no mention of Islamic traditions, celebrations, festivals, and heroes. There is no reference to the magnificent Islamic architecture. If you just place a few pictures of women in hijab and a man in headgear (Ghutra), you can’t say that you have highlighted Islamic culture, a lot more could be done (T 2).

Such an approach of neglecting and marginalizing, as commented by a participant that “[f]or me, the Islamic culture is neglected and marginalized in these books” (T 10), can be counterproductive. Mohd-Ashraf (Citation2005) argues that many Muslim parents in Malaysia thought that English was being used as a tool to transfer western culture and ideologies which contradicted Islamic teachings and principles, which led to resentment towards the English language in Malaysian institutions. In the Middle East, one of the major factors responsible for the lack of success in English language learning is the absence of localized resource materials and instructional methods that give due representation to Islamic and Arab culture. The resource materials, methods, and approaches imported from English speaking countries are, more often than not, “culturally alienating and Islamically inappropriate” in the Arabian Gulf context, and hence, demotivating for the Arab Muslim language learners (Karmani, Citation2005a, p. 94). A teacher has highlighted this aspect as follows:

The representation [of Islamic and Saudi culture] is not significant and there is a clear need to give more space to the local culture, because identification with their own culture in the text that they are studying will help in removing the mental barriers that most of the students have when they come to learn English. A more localized version of the book will certainly result in helping the learners overcome their prejudice against learning English and resisting it less (T 24).

Al-Attas (cited in Mohd-Ashraf, Citation2005), a prominent contemporary Muslim thinker, maintains that, in general, Muslim identity is defined by the beliefs, values, and institutions of Islam; therefore, while using and learning English, Muslims see a conflict between their cultural values and worldview and those conveyed through English language materials. No doubt, there are areas where Islamic and western worldviews may converge. However, in order to resolve conflicting viewpoints, Muslim scholars such as Al-Attas and Wan Daud suggest that such western concepts, values, and ideas should be separated from the course materials, and infused with Islamic cultural values and norms. They term this process “Islamization” of contemporary knowledge (Mohd-Ashraf, Citation2005, pp. 114–5). One can be optimistic that the application of a similar process will lead to developing a version of English that is more representative of Islamic culture, and this new variety of English will find a comfortable niche among World Englishes.

7.2.2. Cultural appropriateness and offensiveness

Thanks to software like Photoshop, the issues of culturally inappropriate and offensive visuals in the course book series were easily resolved after one year of using the standard edition. The special edition catered to cultural sensitivities in term of dress code and hence it was more acceptable:

Many of the things that were offensive to the sensibilities of Saudi students have been removed or appropriated in the Special Edition (T 24). I can’t say that the cultural norms and values in the book show any offence to the local teaching context. However, they don’t help much in teaching certain items which are beyond the boundaries of the students’ background knowledge (T 9).

Nevertheless, there is a caveat in the process of transfiguring the pictures of women shown in the textbook series. As a teacher reprovingly stated: “It is culturally sensitive but in a fake way” (T 11). Quite a few pictures of women were replaced with Arab/Saudi Muslim women in abaya and hijab. The rest were touched up and their heads, arms, and legs were covered with the help of computer software, which on the one hand, gave a false representation of western culture, and on the other, rendered the whole exercise of developing the Special Edition dubious and questionable. Notwithstanding these fundamental flaws, the publisher should be given the benefit of the doubt, as they were given short notice to make the books more culturally acceptable.

7.2.3. Predominance of Western culture (esp. British and American)

… Insofar as the battle between “Islam and English” is concerned, we need to be far more conscious of the extent to which we as English language teachers are reproducing or even delivering global ideologies particularly when they are diametrically in conflict with the worldviews of our Muslim learners (Karmani, Citation2005b, p. 266).

The above quote succinctly sums up the primary concern and ensuing responsibility of language teachers in post-modern times. For example, one exploitative ideology inherent in the course book series is “consumerism.” “This course book encourages consumerism which I think is in contradiction with the Islamic culture of the learner” (T 13). Consumerism is the mother of excessive spending, and thus antithetical to Islamic teachings. The Quran views such practices as “corruption on earth” (fasad-fil-ardh). Therefore, Ali Abi Talib, the fourth caliph of Islam, interpreted it in these words: “The poor are hungry because the rich are wasteful.” Consumerism is just one example of western capitalistic values promoted in this series. One of the participants rather bitterly commented:

No, and we don’t expect anything as substantial as that [representation of Islamic culture] from these books or any other such book. If they stop short of conflicting the Islamic belief and practices and rubbing the western cultural peculiarities on the minds of our students, we would be more than pleased (T6).

A critical look at these course books can also reveal the imperialistic tendencies of the ex-colonialists implicit in the text and visuals:

I think there is a clear dominance of the English culture in this series. We rarely find a proper representation of other cultures. Moreover, it seems a deliberate effort is made to keep the English culture in the “centre”. Even if visuals and pronunciation are considered, the dominant accent used in this series is RP that represents that this series contradicts with the major thesis proclaimed by proponents of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) or World Englishes (WE). We also observe that the English mannerism and etiquette is promoted and considered the ideal practice for a “civilized world” (T10).

Sometimes coursebook writers, advertently or inadvertently, convey an idea that has far-reaching implications. They attempt to change public opinion in favour of the political agendas of powerful lobbies. A critical example of such hegemonic designs is captured in the following observation:

Manipulation of the thought patterns of the learner is systematically achieved [through these books]. One example is the article on “The children in Gaza”: At the outset, it seems really innocent and genuine, but when you are made to believe that the kids in Gaza are more literate than the same percentage of kids in the United States, that’s just preposterous and in simple terminology, LIES. To what end I wonder … (T13).

As highlighted in the findings, the English language should no longer remain a tool of colonial dominance and cultural invasion as it used to be in the past when English departments were established in British colonies for teaching English literature and promoting English culture. The fact that the linguistic dominance of English is fast disappearing, and it has now become a global language should be accepted and respected. More importantly, it is high time that the alleged agenda of western imperialism for mental colonization be discarded, and instead of placing the local cultures on the periphery, they should be given appropriate representation in English language textbooks.

7.2.4. Negligible role in intercultural communication

The English as an International Language (EIL) paradigm conceives of English as a medium of intercultural communication (Seidlhofer, Citation2003). Instead of disempowering learners through linguistic and cultural imperialism (Liddicoat et al., Citation1999), intercultural communication should be promoted to empower the learners through engaging in dialogues with various cultures from around the globe. Understanding of different cultures will expand the mental horizons of learners and deepen their understanding of humanity at large. These course books also fall short of achieving this objective in TESOL:

Again, yes, up to some extent but mostly it is disproportionate in dealing with different cultures. More research-based and deep-rooted cultural changes with the aim of promoting intercultural communication are direly needed to make this series more appealing and beneficial. Currently, these books are not promoting any intercultural understanding. They just include certain limited aspects of other cultures in pieces (T16).

If the intercultural understanding has to be accomplished, TESOL policymakers and syllabus designers will have to offer an equitable share to prominent cultures in the world. Consequently, Islamic culture, linked to 1.6 billion Muslims all over the world, must find a place in TESOL course books produced all over the world. These course books have to be re-conceptualized with this objective:

Prima facie, it [the textbook series] may have an international outlook but it’s mono-cultural and Eurocentric in essence. Promoting intercultural understanding would only come after some considerable representation of Islamic culture occurs (T19).

7.2.5. Motivational effect of culturally relevant resource materials on EIL learners

As Richards and Lockhart (Citation1994) stress that “there are often cultural differences between the beliefs systems of learners from different cultural backgrounds” (p. 56), the English textbooks, which do not culturally correspond to Saudi learners’ Islamic identity, impact their beliefs and attitudes regarding the target language, often resulting in poor language learning motivation (Elyas & Picard, Citation2010). In our context, due to culturally unfamiliar course materials, “students seem to read the course books as a duty and as something which does not relate to their lives. This sense of strangeness seems to suggest to them that the English language is not to be used in real life but only in the classroom” (T 7). We can see a similar vein in another comment:

I think that course books with material related to learner’s own cultural background are much more useful in helping the learner feel at home with the language he is aimed to acquire. If a learner does not identify with the culture that the target language is representing, it is likely that it will take longer for him to acquire the language as he may unconsciously create mental barriers. If the culture being represented is offensive to the cultural sensitivities of the learner, he is likely to develop a resistance against acquiring the target language (T 24).

According to Mucherah (Citation2008), culture is embedded in language, and it provides food for language to digest. Every language learner learns better if the learning material is based on his/her cultural values, societal norms, and experiential background. The experiential background is actually the culture a language learner has been living in since his childhood. This simple principle is at the heart of not only syllabus design, but also pedagogical phenomena:

Familiar themes, norms, and values can only motivate and accelerate the learning process. I strongly believe that an individual’s prior knowledge [of their own culture] plays a significant role in language learning; a learner’s knowledge is an asset for both the learner himself/herself and the teacher (T19).

A large number of Saudi students, particularly the ones coming from small cities, come to the institution with prejudice against the English language, partly because they don’t think they need to learn it and partly because they believe that it is the language of the non-Muslims. This observation shared by several teachers in the research context also suggests that course books with the bulk of course material related to learners’ cultural background can remove these prejudices and help in creating an environment conducive to language learning.

8. Conclusion

The present study attempted to highlight the status and significance of Islamic culture in the modern, multicultural world and its absence from TESOL course books. In particular, it accentuated the need for cultural relevance of the English language course books taught in Saudi Arabia. The dominant trend of exclusion and marginalization of local cultures from TESOL course books raises many political, socio-cultural, and pedagogical questions, which deserve the careful attention of language policymakers and publishers. Being an established language for multi-purpose international communication and a vehicle for accessing the knowledge of medical sciences, latest research and technology, and business administration, English language can play an important role in the Arabian Gulf (Karmani, Citation2005a). Adhering to one of the key tenets of postmodernism, there is a need for an effort at the policy level to promote local identities and realities and deconstruct grand-narratives, such as the one that English belongs exclusively to the British, North Americans, and Australians (see Holliday, Citation1994, pp. 12–13). Rather, the English language should be appropriated by users elsewhere in the world and used for academic or business purposes as well as a medium of intra-national (e.g. India) and inter-national communication.

Once again, Canagarajah (Citation2006) has a piece of advice for TESOL professionals: We should move “[f]rom the us/them perspective of the past … to a we perspective that is more inclusive. TEIL needs to be conducted with multilateral participation. Teachers in different communities have to devise curricula and pedagogies that have local relevance” (p.27). On a macro level, TESOL policy-makers need to allow an epistemic break from the “West-oriented, Centre-based knowledge systems” (Kumaravadivelu, Citation2012, p. 15), and take a sensitive look at the TESOL/EIL situation with the aim to achieve a balance between local and global concerns regarding the representation of source cultures in English language curricula and materials (McKay, Citation2012).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muhammad Athar Shah

Muhammad Athar Shah holds a Doctorate (EdD) in TESOL from University of Exeter, UK. He spent ten years in the Arabian Gulf, working at Qatar University, Doha and King Abdulaziz University, KSA. Recently, he joined OISE, University of Toronto to pursue his career as an educational researcher. His research interests include language and culture, teacher professional learning and excellence, and teacher education policies.

Tariq Elyas

Tariq Elyas is an Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics at King Abdualziz University, KSA. Previously, he worked as the Vice Dean for Graduate Studies, Director of the MA TESOL Program, and the Research Unit Head of the Prince Khalid Al-Faisal Centre for Moderation. Currently, he is the General Manager of International Scientific Indexed Journals and Books at KAU. Dr Elyas has background in research on World Englishes, Teacher Identity, Policy Reform, e-Learning, and Critical Pedagogy. He has published in prestigious journals and contributed to TESOL Encyclopedia (2018).

Notes

1. TEIL stands for “Teaching English as an International Language”; and the term TESOL may be considered an umbrella term for ELT, EFL, ESL, TEFL, TESL, etc.

2. The name of the course book series has been anonymised. The study primarily aims to highlight the issue of representation of source culture in TESOL textbooks. We have no intention to deprecate an otherwise popular coursebook series.

References

- Al-Haq, F.-A.-A., & Smadi, O. (1996). The status of English in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) from 1940-1990. In A. W. Conrad & A. Rubal-Lopez (Eds.), Post-imperial English: Status change in former British and American colonies, 1940-1990 (Vol. 72, pp. 457–19). China: Walter de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110872187.457

- Al-Hijailan, T. A. (1999). Evaluation of English as a foreign language: Textbook for third grade secondary boys’ schools in Saudi Arabia (Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation). Mississipe State University.

- Aliakbari, M. (2004). The place of culture in the Iranian ELT textbooks in high school level. Paper presented at 9th Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics Conference at Nam Seoul University, Korea. http://www.paaljapan.org/resources/proceedings/PAAL9/pdf/Aliakbari.pdf

- Bazeley, P. (2013). Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical strategies. London: Sage.

- Beaudrie, S., Ducar, C., & Relaño-Pastor, A. M. (2009). Curricular perspectives in the heritage language context: Assessing culture and identity. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 22(2), 157–174. doi:10.1080/07908310903067628

- Borade, G. (2012). Muslim culture and traditions. Retrieved from http://www.buzzle.com/articles/muslim-culture-and-traditions.html

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Byram, M. (1989). Cultural studies in foreign language education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters LTD.

- Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publication. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/T/DG4/linguistic/Source/Guide_dimintercult_EN.pdf

- Byram, M., & Wagner, M. (2018). Making a difference: Language teaching for intercultural and international dialogue. Foreign Language Annals, 51(1), 140–151. doi:10.1111/flan.12319

- Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2006). TESOL at 40: What are the issues? TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 9–34. doi:10.2307/40264509

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. London: Routledge.

- Cook, V. (1999). Going beyond the native speaker in language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 33(2), 185–209. doi:10.2307/3587717

- Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (1999). Cultural mirrors: Materials and methods in the EFL classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in second language teaching and learning (pp. 196–220). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Crotty, M. (2003). The foundation of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Cunningsworth, A. (1995). Choosing your course book. Oxford: Heinemann.

- Eisner, E. W. (1998). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Elyas, T., & Picard, M. (2010). Saudi Arabian educational history: Impacts on English language teaching. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 3(2), 136–145. doi:10.1108/17537981011047961.

- Ernest, P. (1994). An introduction to research methodology and paradigms. Exeter: RSU, School of Education, University of Exeter.

- Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. London: Longman.

- Foss, S. (2009). Rhetorical criticism: Exploration and practice. Illinois: Waveland Press.

- Gee, J. (1990). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. New York: The Falmer Press.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigm in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 99–136). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action . In T. McCarthy (Ed.), Volume one: Reason and the rationalization of society (Vol. 1). Boston, MA: Beacon.

- Hansen, H. L. (2004). Foreign language studies and interdisciplinarity. In H. L. Hansen (Ed.), Disciplines and interdisciplinarity in foreign language studies (pp. 7–20). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Hinkel, E. (ed.). (1999). Culture in second language teaching and learning. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the World: Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11–30). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kachru, B. B. (1990). World Englishes and applied linguistics. World Englishes, 9(1), 3–20. doi:10.1111/j.1467-971x.1990.tb00683.x.

- Karmani, S. (2005a). Petro-Linguistics: The emerging nexus between oil, English, and Islam. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 4(2), 87–102. doi:10.1207/s15327701jlie0402_2.

- Karmani, S. (2005b). English, ‘Terror,’ and Islam. Applied Linguistics, 26(2), 262–267. doi:10.1093/applin/ami006

- Kilickaya, F. (2004). Guidelines to Evaluate Cultural Content in Textbooks. The Internet TESL Journal, 10(12). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Kilickaya-CulturalContent/

- Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kramsch, C. (2004). Language, thought and culture. In A. Davies & C. Elder (Eds.), The handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 235–261). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Individual Identity, Cultural Globalization, and Teaching English as an International Language: The Case for an Epistemic Break. In L. Alsagoff, S. L. McKay, G. Hu, & W. A. Renandya(Eds.), Principles and practices for teaching English as an international language (pp. 9–27). New York: Routledge.

- Kvale, S. (1995). The social construction of validity. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(1), 19–40. doi:10.1177/107780049500100103

- Le Ha, P. (2008). Teaching English as an international language: Identity, resistance and negotiation. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- Lewis, B. (2003). The crisis of Islam: Holy war and unholy terror. New York: Modern Library.

- Liddicoat, A. J., Crozet, C., & Bianco, J. L. (1999). Striving for the third place: Consequences and implications. In J. L. Bianco, A. J. Liddicoat, & C. Crozet (Eds.), Striving for the third place: Intercultural competence through language education (pp. 181–187). Melbourne: Language Australia Ltd.

- Liddicoat, A. J., & Scarino, A. (2013). Intercultural language teaching and learning. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lowenberg, P. H. (1993). Issues of validity in tests of English as a world language: Whose standards?. World Englishes, 12(1), 95–106. doi:10.1111/j.1467-971X.1993.tb00011.x

- Mahboob, A. (2011). English: The industry. Journal of Postcolonial Cultures and Societies, 2(4), 46–61. https://www.academia.edu/1441288/English_-_The_Industry

- Mahboob, A., & Elyas, T. (2014). English in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. World Englishes, 33(1), 128–142. doi:10.1111/weng.12073

- McDonald, J. D. (2008). Measuring personality constructs: The advantages and disadvantages of self-reports, informant reports and behavioural assessments. Enquire, 1(1), 1–19. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/sociology/documents/enquire/volume-1-issue-1-dodorico-mcdonald.pdf

- McKay, S. L. (2002). Teaching English as an international language: Rethinking goals and approaches. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McKay, S. L. (2003a). Teaching English as an international language: The Chilean context. ELT Journal, 57(2), 139–147. doi:10.1093/elt/57.2.139.

- McKay, S. L. (2003b). The cultural basis of teaching English as an international language. TESOL Matters, 13(4), 1–2. Retrieved from http://www.tesol.org/s_tesol/sec_document.asp?CID=192&DID=1000

- McKay, S. L. (2012). Principles of Teaching English as an International Language. In L. Alsagoff, S. L. McKay, G. Hu, & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Principles and Practices for Teaching English as an International Language (pp. 337–346). New York: Routledge.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. London: Sage.

- Mohd-Ashraf, R. (2005). English and Islam: A clash of civilizations? Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 4(2), 103–118. doi:10.1207/s15327701jlie0402_3

- Mouton, J. (1996). Understanding social research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

- Mucherah, W. (2008). Immigrants’ perceptions of their native language: Challenges to actual use and maintenance. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 7(3), 188–205. doi:10.1080/15348450802237806

- National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project. (1996). Standards for foreign language learning: Preparing for the 21st century. Retrieved from http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3392

- Nault, D. (2006). Going global: Rethinking culture teaching in ELT contexts. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19(2), 314–328. doi:10.1080/07908310608668770.

- Nevo, J. (1998). Religion and national identity in Saudi Arabia. Middle Eastern Studies, 34(3), 34–53. doi:10.1080/00263209808701231.

- Ngugi wa, T. O. (1986). Decolonising the mind : The politics of language in African literature. London: James Currey; Nairobi: EAEP; Portsmouth: Heinemann.

- Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409–429. doi:10.2307/3587831.

- Norton, B., & Macpherson, S. (1997). Ngugi wa Thiong’o: An African Vision of Linguistic and Cultural Pluralism. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 641–645. doi:10.2307/3587848.

- Oppenheim, N. (1992). Questionnaire design, interview and attitudes measurement. London: Pinter.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Payne, N. (2006). Western-Islamic relations and contributions of the intercultural field. Intercultural Islam. SIETAR Europa. Retrieved from http://www.sietareu.org/images/stories/magazine/issue1_item02_westislam.htm

- Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. New York: Longman.

- Pennycook, A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: A critical introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Pennycook, A. (2004). Critical applied linguistics. In A. Davies & C. Elder (Eds.), Handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 784–807). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Pew Research Center. (2011). The future of the global Muslim population (2010–2030). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://pewforum.org/ The-Future-of-the-Global-Muslim-Population.aspx

- Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in Education: Theory, research and applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Rahman, T. (2002). Language, Ideology and power: Language learning among Muslims of Pakistan and North India. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Rich, S., & Troudi, S. (2006). Hard times: Arab TESOL students’ experiences of racialization and othering in the United Kingdom. TESOL Quarterly, 40(3), 615–627. doi:10.2307/40264548.

- Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Schmitt, T. L. (2009). Working Together: Bringing Muslim students into the ESL classroom. TESOL’s ICIS Newsletter, 7(3), 1–3. Retrieved from https://www.tesol.org/convention-2018/tesol-2018-convention-news/2011/10/26/icis-news-volume-7-3-(december-2009)

- Seidlhofer, B. (2003). A concept of international English and related issues: From ‘real English’ to ‘realistic English’?. Language Policy Division, DG-IV-Directorate of School, Out-of-School and Higher Education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Sharifian, F. (Ed.). (2009). English as an international language: Perspectives and pedagogical issues. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. doi:10.3233/EFI-2004-22201.

- Sidhwa, B. (1996). Creative processes in Pakistani English fiction. In R. J. Baumgardner (Ed.), South Asian English: Structure, use and users (pp. 231–240). Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Stern, H. H. (1992). Issues and options in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Syed, Z. (2003). The sociocultural context of English language teaching in the Gulf. TESOL Quarterly, 37(2), 337–341. doi:10.2307/3588508.

- Tollefson, J. (1991). Planning language, planning inequality: Language policy in the community. NewYork: Longman.

- Troudi, S. (2005). Critical content and cultural knowledge for teachers of English to speakers of other languages. Teacher Development, 9(1), 115–129. doi:10.1080/13664530500200233.

- Weber, A. S. (2011). Politics of English in the Arabian Gulf. Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, Sarajevo. Retrieved from http://eprints.ibu.edu.ba/13/

- Widdowson, H. G. (2004). A perspective on recent trends. In A. P. R. Howatt & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), A history of English language teaching (2nd ed., pp. 353–372). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Zizek, S. (2012). The spectre of ideology. In S. Zizek (Ed.), Mapping ideology (pp. 1–33). London: Verso Books.

- Zughoul, M. R. (2003). Globalization and EFL/ESL pedagogy in the Arab World. Journal of Language and Learning, 1(2), 106–146. http://webspace.buckingham.ac.uk/kbernhardt/journal/jllearn/1_2/zughoul.html

Appendix 1.

Open-ended Questions

Please respond to the following questions in detail.

Does the XXX English textbook series give any importance or regard to Islamic culture? Explain.

To what extent are you satisfied with the representation of Arab (Saudi) culture in the XXX English textbook series?

What kind of cultural values, norms and practices are presented in the XXX English textbook series?

How far the cultural norms and values reflected in the XXX English textbook series are appropriate for your teaching context?

Do you think that the XXX English textbook series has an international outlook and represents a variety of cultures (e.g. Western, Asian, Middle Eastern and African)? Explain.

How successful is the XXX English textbook series in promoting intercultural understanding (e.g. Islamic culture vis-à-vis Western culture)?

You may add anything else relevant to the topic discussed above.