Abstract

The research on the effects of metacognitive strategy awareness and self-regulation on second language reading achievements has come to confirmatory conclusions. However, the associations and possible interactions between metacognitive and self-regulatory capacities have been subject of debate. Theoretically, the relationship between the two global skills in affecting learning has ranged from rivaling alternatives to complementary associates. Accordingly, some recent perspectives have delineated the relative potency of the two concepts within models where metacognitive, behavioral, motivational and emotional dimensions of learning interact. This study resorted to structural equation modeling in outlining and testing the causal relationships between three types of metacognitive reading strategies, namely global, problem-solving, and support strategies, and self-regulation in affecting reading proficiency. The data were collected from 311 Iranian undergraduate students majoring in English using Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Questionnaire, Self-Regulation Questionnaire and reading proficiency test. By testing the hypothesized model against several fitness criteria, the causal relationships among the variables were confirmed indicating a positive relationship between three components of metacognitive awareness and reading proficiency by mediating role of self-regulation. The findings provide further conceptual support for dynamic models of self-regulated action and practical implications regarding the complementary role of metacognitive and self-regulatory engagements in reading development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Reading comprehension makes up an important component of second/foreign language acquisition. A satisfactory performance on high-stake standard tests requires an optimal level of automaticity which relies to a large extent on persistent effort to develop strategic reading skills. This long-term achievement demands the mobilization of all emotional, motivational, cognitive and metacognitive resources together to end up with a convenient level of reading ability. Strategy instruction has been practiced during the past three decades as a shortcut to fluent reading. However, the effectiveness of strategy training depends very much on fair allocation of various types of mental resources. This study implies that metacognitive training needs to be accompanied by the development of proper self-regulatory skills especially in motivational and emotional respects. The findings here hopefully provide instructors with useful insights into how to help enhance L2 learners’ reading comprehension and improve their reading strategies through effective use of self-regulation.

1. Introduction

Reading in a second language plays a crucial role in getting information from original L2 resources, and EFL students need to acquire the ability to read academic texts fluently and efficiently. The association between reading and understanding has been a major subject of enquiry for those second language researchers who adopt a cognitive approach to L2 reading. Reading comprehension is not an inactive process of obtaining meaning from the text. Beyond the decoding processes, reading involves a wide range of cognitive and metacognitive actions in which readers should take strenuous and dynamic control of their comprehension (Griffith & Ruan, Citation2005). A major aspect of successful reading comprehension depends to a large extent on the awareness and monitoring of the process of comprehension by L2 readers (Baker & Brown, Citation1984; Graves et al., Citation2001).

Metacognition in simple terms means knowledge about knowledge and learning how to learn. Short after the introduction of metacognition to education (J. H. Flavell, Citation1976; J. J. Flavell, Citation1979), second language acquisition researchers grew interested in the concept. A considerable amount of research has been carried out since then on the effect of metacognitive awareness and strategic reading on the development of reading proficiency (Sheorey & Mokhtari, Citation2001; Tavakoli, Citation2014; Zare, Citation2013; L. J. Zhang, Citation2010). In this regard, learners’ mastery of metacognitive reading strategies has been recognized as helping learners to enhance their reading skills (Cohen & Macaro, Citation2007; Koda, Citation2007).

Despite the surge of interest in metacognition of reading, the complexity imbedded in the definition and theorization of metacognition has been a source of skepticism and criticism toward the research concerning metacognitive awareness in reading. The perplexity invoked by the situation was even exacerbated by the introduction of the concept of self-regulation into L2 acquisition in the early 21st century such that outstanding figures in this area proposed the abandoning of metacognition studies in favor of studies on self-regulated learning (Dörnyei, Citation2005; Dörnyei & Skehan, Citation2003). The suggestion was that self-regulation is an umbrella concept that encompasses all cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, affective and motivational aspects of learning leading to real achievements in second language proficiency including reading (Zimmerman, Citation2000).

Therefore, the association between metacognition and self-regulation has been a source of bewilderment with regard to the understanding of reading comprehension process. Following a set of conceptualizations regarding the interrelatedness of metacognition and self-regulation (Dinsmore et al., Citation2008; Fox & Riconscente, Citation2008; Kaplan, Citation2008), there has been an increasing attempt to accommodate metacognition and self-regulation studies within one single framework. By the end of the second decade of the 21st century, the common impression among theoreticians and researchers is that metacognitive strategies enjoy a sufficient level of flexibility and vibrancy to become compatible with the prevailing concept of self-regulation (Griffiths, Citation2019). Therefore, any attempt within second language acquisition research to account for reading development within a unitary model entailing strategic reading and self-regulated reading will be of both theoretical and practical value. Hence, the specific problem under investigation in this study was to model the interaction between metacognitive reading strategies and self-regulation in affecting second language reading proficiency. The specific purpose is to examine how self-regulation plays the mediating role between metacognitive strategy awareness and second language reading proficiency.

2. Review of the related literature

2.1. The Relationship between metacognition and self-regulation

Metacognition (MC) and self-regulation (SR) have dominated educational psychology and affiliated fields including second language (L2) learning and teaching in the past few decades. The theoretical explications of the two pedagogical concepts have depicted the relationship between them as ranging from rivaling alternatives to interacting and complementing concepts. Despite the pervaded perplexities, the research on MC and SR has boastfully contributed to our understanding of learning and instruction.

The prevalence of presumptions regarding the centrality of some degree or form of awareness and control over cognitive processes involved in learning stimulated a plethora of research on metacognition in 1970s and 1980s (Baker & Beall, Citation2009). MC has been generally conceived as “knowledge about knowledge” (J. H. Flavell, Citation1976, p. 232) or “thinking about thinking” (Anderson, Citation2002, p. 23). It encompasses both knowledge or awareness and a control or regulation of such cognitive processes as monitoring, planning, evaluating, repairing, revising, and summarizing (J. H. Flavell, Citation1976). According to J. J. Flavell (Citation1979), MC is composed of four metacognitive elements of knowledge, experience, goals or tasks, and strategies or actions.

Self-regulation and the associated concept of self-regulated learning (SRL) were almost contemporary to metacognition in being introduced to the field of educational psychology in 1980s. Early writers on metacognition considered self-regulatory skills as a subcomponent of metacognition alongside metacognitive knowledge (Baker & Brown, Citation1984). Zimmerman (Citation2000, p. 14) conceptualized self-regulation as referring to “self-generated thoughts, feelings and actions that are planned and cyclically adapted to the attainment of personal goals”. This understanding of SR carries elements from MC as it makes a point of “planning toward personal goals” which necessitates metacognitive awareness and control. Dörnyei (Citation2005) defined SR as “the degree to which individuals are active participants in their own learning” (p. 191) where the learners’ active engagement in the learning process is foregrounded. Others have confirmed the inclusion of metacognitive concepts of strategy awareness and application when they have displayed SR as “the control that students have over their cognition, behavior, emotions and motivation through the use of personal strategies to achieve the goals they have established” (Panadero & Alonso-Tapia, Citation2014, p. 451). Hadwin et al.’s (Citation2011) definition of SR is even more congenial to metacognitive strategies: “Strategically planning, monitoring, and regulating cognition, behavior, and motivation” (p. 67).

SRL is the learning that results from self-regulation. It is an umbrella term that covers many aspects of MC and SR discussed in the literature (Panadero, Citation2017). SRL requires the active involvement of learners in cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, motivational and emotional aspects of learning (Zimmerman & Schunk, Citation2011). It has also been described as “learning how to learn” (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2019, p. 889).

Self-regulation often implies the control dimension of metacognition referring to such strategies as evaluating, monitoring and planning. In this sense, self-regulation might be considered as the regulatory component of metacognition (Baker & Beall, Citation2009). However, the relationship between metacognition and self-regulation has been the subject of lengthy debates. In Fox and Riconscente (Citation2008) delineation, metacognition is the knowledge or awareness of self whereas self-regulation entails acting upon self. Despite this distinction, they asserted that the two concepts are intertwined and “incestuously related” phenomena (p. 374). Schunk (Citation2008) postulated that metacognition, self-regulation and self-regulated learning are three important types of cognitive control processes. Similarly, by examining 255 related studies published within 5 years, Dinsmore et al. (Citation2008) concluded that MC, SR and SRL were nested in definition although there were remarkable differences in the measurement of the three notions. Kaplan (Citation2008) considered these three processes as subtypes of the higher-order mental capacity of Self-Regulated Action and reiterated that any boundary between them is “fuzzy and permeable” (p. 479). He proposed that the focus be shifted from looking for boundaries to multidimensional conceptualization by focusing on aspects of self, object and means. In this regard, one way to distinguish metacognition from self-regulation is to observe what aspect of human behavior is focused on: Metacognition involves a focus on cognition and self while self-regulation entails human behavior in environment.

2.2. Second language reading in lights of MC and SR

Reading involves comprehension monitoring and evaluation which entail both metacognitive engagement and self-regulation. Accordingly, the enrichment of metacognitive and self-regulatory capacity of second language learners has been studied and practiced as an essential factor in enhancing reading proficiency. The relationship between EFL learners’ metacognitive awareness/control and their reading achievements is an issue of very little controversy (Cohen & Macaro, Citation2007; Jafari & Shokrpour, Citation2012; Koda, Citation2007; Sheorey & Mokhtari, Citation2001; Tavakoli, Citation2014; Zare, Citation2013; L. J. Zhang, Citation2010; L. Zhang, Citation2014). However, there have been some studies in EFL contexts which have failed to approve the effect of metacognitive awareness on reading proficiency (e.g., Korotaeva (Citation2012) and Pammu et al. (Citation2014) in Russian and Indonesian contexts, respectively). The relationship between reading comprehension and self-regulation is a less attended area in SLA studies, but there is some research corroborating the positive effects of self-regulation on L2 reading (e.g., Maftoon & Tasnimi, Citation2014).

Research on language learning strategies has occasionally been criticized mainly due to the existing confusions regarding its definition, theorization or research methods. Some have even proposed the abandonment of metacognition research in favor of the related overarching notion of self-regulated learning capacity (Dörnyei, Citation2005), a suggestion that was characterized as “throwing the baby out with the bathwater” (Rose, Citation2012, p. 92). According to Souvignier and Mokhlesgerami (Citation2006), reading strategies must be taught to EFL learners in a way to make them able to apply those strategies in self-regulated reading. The teachability of self-regulated learning strategies adapted from Zimmerman’s three-stage model of self-regulation (Zimmerman, Citation2001) for improving reading proficiency has also been experimentally tested and approved by Morshedian et al. (Citation2017).

2.3. New dynamic models

Due to the confusions concerning the relative effectiveness of metacognitive and self-regulation skills in L2 reading development, there have recently been a set of studies that perceive a dynamic relationship between the three variables. Mbato (Citation2013) reported a mixed method action research in which Indonesian EFL learners’ SRL skills in reading improved as a result of teaching metacognitive skills to them. In another study, increasing metacognitive capacity of EFL learners through strategy-based instruction turned out to improve learners’ reading comprehension and self-regulation skills (Kavani & Amjadiparvar, Citation2018). Through methodological innovation, Zhang and colleagues (e.g., L. J. Zhang, Citation2010) have tried to study language learning strategies in lights of integrating components from metacognition and self-regulated learning skills.

In an attempt to depict the dissension concerning language learning strategy research in relation to self-regulation studies, Rose et al. (Citation2017) reviewed 24 articles published in 2010–2016 and recognized three types of research on language learning strategies. In addition to SR-oriented strategy research and traditional strategy-oriented research, they identified a third type of studies with a focus on new avenues of self-regulated learner strategies. For example, Ardasheva (Citation2016) designed a structural equation modeling of the relationship between language learning strategies and reading achievement by taking a set of individual difference factors into account as mediating or moderating variables. Teng and Zhang (Citation2016) constructed and validated a questionnaire for measuring self-regulated writing strategies of EFL learners by borrowing elemental concepts from both self-regulation and strategy research. According to them, metacognition is a dynamic system which is intertwined with cognitive and social behavioral variables.

Rose et al. (Citation2017) concluded that language learning strategy research and self-regulation research need not be given up one in favor of the other. Rather, these two concepts tend to complement each other in understanding learners’ self-directed learning. Therefore, a dynamic interaction between the elements from both metacognition and self-regulation in affecting reading comprehension has been suggested as a model to deal with the persisting confusion. In such a model, personal, behavioral and environmental elements interact with each other. One such model has been introduced in Oxford’s Strategic Self-Regulated model (Oxford, Citation2017) in which metacognitive strategies interact with motivational and emotional components of growth mindset, self-efficacy, autonomy, agency, hope and resilience to determine SRL. The model is inspired by complexity theory and the role of context is highlighted in it.

In the present study, a SEM approach was adopted for the purpose of building a causal-structural model by which the contribution of each of the aforementioned constructs could be estimated. The metacognitive outlining of the model is based on Mokhtari and Sheorey (Citation2002) who categorized metacognitive reading strategies into three broad types of Global, Problem-Solving and Support reading strategies (p. 436). Global reading strategies are general strategies that are typically used prior to reading and include such strategies as setting a goal, matching the content with the reading goal, skimming, using text features and contextual clues. Problem-solving strategies are often applied when confusions occur during reading and include such strategies as keeping concentration, adjusting reading rate, reflecting on reading, visualizing and guessing meaning from context. Support reading strategies assist the reader to evaluate comprehension both during and after reading including paraphrasing, note-taking, summarizing, using dictionaries and self-reflection (Mokhtari & Sheorey, Citation2002).

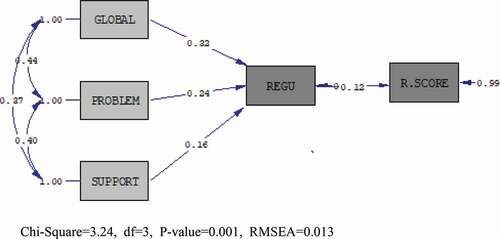

In the research carried out so far to examine the relative strength of global, problem-solving and support reading strategies with reading proficiency of second language learners, varied levels of correlation have been reported distinctively for these three types of reading strategies (Alhaqbani & Riazi, Citation2012; Jafari & Shokrpour, Citation2012; Tavakoli, Citation2014; Zare, Citation2013). Mohseni et al. (Citation2020) reported that improving EFL learners’ awareness and control over these three types of metacognitive strategies through experimental intervention secured the enhanced reading comprehension of different genres of texts. Figure shows the hypothesized structural model of the relationships between participants’ three types of metacognitive strategy awareness (GLOB, PROB, and SUP), self-regulation and reading proficiency.

Figure 1. Hypothesized structural model of the relationship between metacognitive reading strategies and reading proficiency by mediation of self-regulation.

Based on the model outlined above, the present study was intended to test the following hypotheses:

H1. There is a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ global reading strategy and self-regulation.

H2. There is a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ problem-solving strategy and self-regulation.

H3. There is a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ support reading strategy and self-regulation.

H4. There is a significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ self-regulation and reading proficiency.

H5. Self-regulation plays a mediating role between global reading strategy and reading proficiency.

H6. Self-regulation plays a mediating role between problem-solving strategy and reading proficiency.

H7. Self-regulation plays a mediating role between support reading strategy and reading proficiency.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

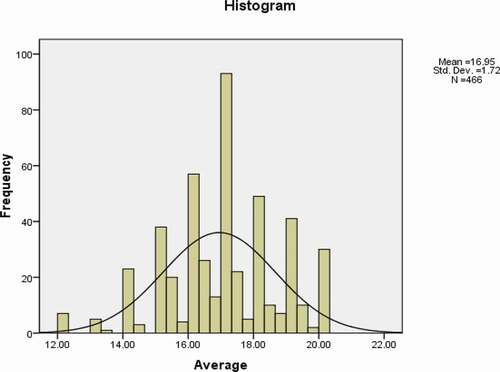

The participants in this study were 311 (110 males and 201 females) selected out of 466 undergraduate English students majoring in English Literature, Teaching, and Translation at three universities in Tabriz, Iran, namely Tabriz University (N = 156, n = 77), Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University (N = 145, n = 107), and Islamic Azad University, Tabriz branch (N = 165, n = 127). They were BA level students who had already passed 4–12 credit courses of Reading Comprehension and the two-credit course of Study Skills at university. They had studied English for 7 years at high school and pre-university centers, with some having attended intensive English classes at private language institutes. The average age of participants was 21, the youngest being18 and the oldest 43 years old. The participants were also screened by their average scores on reading comprehension courses they had taken as part of their degree program (Figure ).

Participation in this study was on a voluntary basis. The homogeneity of participants in terms of general advanced-level reading comprehension capabilities was ascertained through the administration of a standard reading proficiency adapted from archived versions of TOEFL iBT. Out of 466 initial participants, 311 testees whose scores fell between one standard deviation below and above the mean and were regarded as owning nearly the same reading proficiency level were selected for the study (Table ).

Table 1. Selection of the participants based on homogeneity

3.2. Instruments

The following three standard instruments were utilized for the measurement of the three variables involved in the model outlined here, i.e., reading strategy awareness, self-regulation and reading proficiency. A demographic survey was also attached to the questionnaires in order to collect data on participants’ gender, age, academic stage, and their average grades of reading comprehension course.

3.2.1. Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (MARSI)

The original version of Mokhtari and Reichard (Citation2002) MARSI is a 30-item survey designed to measure global strategies (what a reader does to prepare for reading a text), problem-solving strategies (what a reader does when struggling to understand a text), and support strategies (how a reader supports comprehension). A number of studies have investigated the reliability and validity of this scale. Mokhtari and Reichard (Citation2002) reported a Chronbach’s alpha of.89. Furthermore, reliability estimates utilizing Cronbach’s alpha in this study were examined to determine whether the questionnaire items showed an acceptable level of internal consistency (Table ).

Table 2. The results of the reliability statistics of the MARSI, SRL, and their subscales

Based on MARSI, Mokhtari and Sheorey (Citation2002) developed Survey of Reading Strategies (SORS) specifically for second language reading, and Mokhtari et al. (Citation2018) introduced a revised version of MARSI (MARSI-R) where they reduced the number of items to 15. Although SORS has been widely used in SLA research for assessing L2 learners’ perceived use of reading strategies, the original form of the inventory was decided to be used here since the theoretical association between the components of metacognitive awareness and self-regulated learning ability was the major focus of the present study. An additional reason in this regard was related to the proficiency level of EFL learners participating in this study. They were advanced-level students of English in academic context. The authors of MARSI and SORS themselves have asserted that MARSI is more appropriate for advanced-level learners of English while SORS is more appropriate for learners with low levels of English proficiency (Mokhtari et al., Citation2018, p. 239).

3.2.2. Self-regulated learning questionnaire

For the purpose of the present study, the self-regulation learning questionnaire developed by Hirata (Citation2010) to assess self-regulated learning (SRL) in Japanese context was used. The questionnaire includes 20 items in three subscales of self-regulated learning strategies, motivational orientation, and motivational beliefs. The variables related to each dimension are assessed on a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire had already been piloted by Radi Arbabi (Citation2013) with 68 Iranian learners of English as a foreign language to ascertain its reliability. However, we assessed its reliability with 311 EFL learners through a confirmatory factor analysis to determine whether it is useful for the Iranian context. The results of reliability statistics indicated that the questionnaire had an acceptable reliability rate (Table ).

English versions of both questionnaires were used here to keep up with validity requirements.

3.2.3. Reading proficiency test

A TOEFL iBT reading comprehension test with an already-approved content validity was used to gather data regarding the participants’ reading ability. According to Educational Testing Service (ETS), three types of tasks exist in the new TOEFL: Reading for basic comprehension, reading to learn, and inferencing.

3.3. Procedure

Data collection process started in February 2019. First, the standard reading proficiency test was administered to determine the participants’ levels on reading. According to the students’ scores on the test, the homogeneous population for the study including 311 students was selected. Then, the participants were asked to complete MARSI and SRL questionnaires. The participants were informed of the purpose of the study in order to remove any possible anxieties. Before distributing the test and questionnaires to the participants, they were told that their identities would be kept confidential and that no information revealing their identity would be used in the study. The collected data from the test and questionnaires were exported to SPSS 22.0 as a data file manager prior to running the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using LISREL 8.50 which was used as the estimation method in this study.

3.4. Data analysis

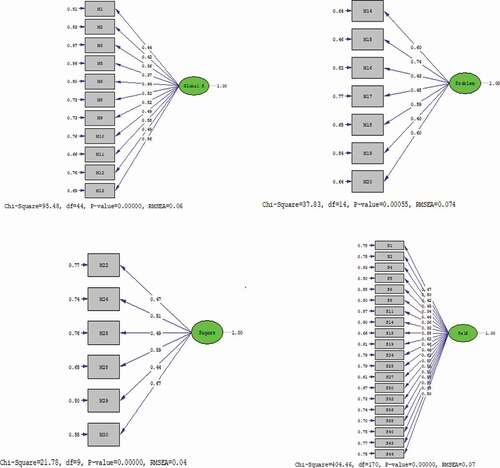

Following Anderson and Gerbing’s widely accepted approach (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1998), first the scales were tested (measurement model); then, the structural model was tested on the variable level. LISREL 8.5 was used for both tests. A confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated the necessity of deleting some items to improve model fit. MARSI measure was reduced from 30 to 24 items. Such a reduction of items on a measure is consistent with common practice (e.g., Aryee et al., Citation2005).

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) combines the capability of path analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and regression analysis. Therefore, SEM clearly has more power than other procedures for investigating a variety of independent and dependent variables simultaneously. Confirmatory Factor Analysis is a procedure used to test hypotheses regarding proposed factor structures. The procedure and the findings are indicated in Figure .

4. Results

Correlation analysis and SEM were utilized to test and examine the research questions of the study statistically. Before preparing data for further analysis, the distribution normality of scores on MARSI, SRL, and reading proficiency test were checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. According to K-S test, based on standard placement test, variables of GLOB, PROB, SUP, SRL, and Reading Proficiency scores had asymptotic Sig (2-tailed) values larger than 0.05. Therefore, the scores on them can be assumed to be normally distributed (Total GLOB: p = .080, total PROB: p = .079, total SUP: p = .075, total SLR: p = .090, and total reading proficiency score: p = .091).

The relationship between metacognitive strategy awareness, self-regulation and reading proficiency was calculated through Pearson’s product-moment correlation. The second correlation analysis was run to determine the relationship between subscales of metacognitive strategy awareness and self-regulation. A summary of correlations has been presented in Table .

Table 3. One Sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normal distribution

Table 4. Correlations between MARSI, subscales of MARSI, self-regulation and reading proficiency

Table indicates that there is a significant correlation between MARSI, SRL and reading proficiency. The correlation coefficient shows positive relationships between MARSI and SRL (r = .558, p < 0.05). It was also found that there is positive correlation between SR and reading proficiency (r = .489, p ≤ 0.05) as well. With regard to the correlations between subscales of reading strategies and SR, the highest correlations were found between GLOB and SR (r = .461, p < 0.05) and PROB and SR (r = .433, p < 0.05). As to the direct correlations between each of the three types of metacognitive reading strategies and reading proficiency, only a weak meaningful correlation (r = .112) was found with Global strategy, and there was no significant correlation between Support and Problem-Solving strategies and reading comprehension.

The next phase of study aimed at building a causal-structural model through which the associations among reading ability, three types of metacognitive awareness of reading strategies, and self-regulation could be estimated. The hypothesized relationships among the variables of the study as shown in Figure were tested through using structural equation modeling (SEM) based on the dataset collected in the main study. The model examines the influence of metacognitive awareness and self-regulation on reading proficiency. To examine the structural relations, the proposed model was tested using the LISREL 8.50 statistical package. Several criteria were used to evaluate the construct validity of the full structural model. Following what is conventional in SEM studies, in addition to Chi-square (X2) statistics, the use of which for such large samples can be debatable, other coefficients were also obtained, such as Chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (X2/df) magnitude, which should be less than three, the Normed Fit Index (NFI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) with a cut value greater than 0.90, and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of about.06 or.07 (Schreiber et al., Citation2006). The acceptable criteria for fit indices are presented in Table .

Table 5. Summary of evaluation of proposed SEM model’s fit indices

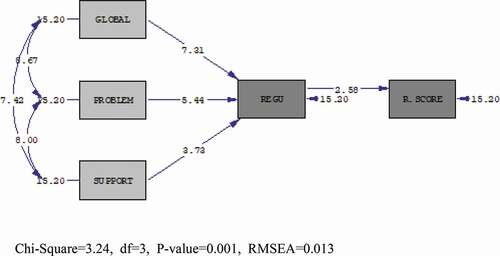

Based on the proposed model, the relationships among all variables, and also between all variables and metacognitive strategy awareness subscales was explored. To check the strengths of the causal relationships among the variables, the t-values and standardized estimates were examined. Estimates were displayed on the paths (Figures and ). The first one is based on the standardized coefficient (β) which explains the predictive power of the independent variable and presents an easily grasped picture of effect size. The closer the magnitude to 1.0, the higher the correlation and the greater the predictive power of the variable is. The second measure is the t-value (t) where t > 2 or t < −2 indicates a significant effect.

The results demonstrated that there are positive and significant causal relationships between Iranian EFL learners’ awareness of three types of metacognitive reading strategies (global reading strategies: β = .32, t = 7.31, problem-solving strategies: β = .24, t = 5.44, and support reading strategies: β = .16, t = 3.73) and self-regulation (β = .12, t = 2.58) with reading proficiency. Figures and indicate the schematic representation of the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) between awareness of three types of metacognitive reading strategies and reading proficiency by mediating role of self-regulation. As demonstrated, the model shows significant effects at the level of <5 percent.

Chi-Square = 3.24, df = 3, P-value = 0.001, RMSEA = 0.013

Chi-Square = 3.24, df = 3, P-value = 0.001, RMSEA = 0.013

A summary of the structural equation modeling of the relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ awareness of three types of metacognitive reading strategies and reading proficiency by mediating role of self-regulation has been presented in Table . Based on the approved model, the initial research hypotheses are confirmed as follows.

H1: As indicated in Table , there is a significant impact of global reading strategy on self-regulation (β = .32, t = 7.31). The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the first hypothesis is confirmed. It is established that there is a significant causal relationship between global reading strategy and self-regulation.

H2: There is a significant impact of problem-solving strategy on self-regulation (β = .24, t = 5.44). The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the second hypothesis is similarly verified. It shows that there is a significant causal relationship between problem-solving strategy and self-regulation.

H3: There is a significant impact of support reading strategy on self-regulation (β = .16, t = 3.73). The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the third hypothesis is statistically affirmed. It is established that there is a significant causal relationship between support reading strategy and self-regulation.

H4: As indicated in Table , there is a significant impact of self-regulation on reading proficiency (β = .12, t = 2.58). The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the fourth hypothesis is also affirmed. It can be said that there is a significant causal relationship between self-regulation and reading proficiency.

H5: There is a significant impact of global reading strategy on self-regulation (β = .0384). Moreover, there is a significant impact of self-regulation on reading proficiency (β = .12, t = 2.58). The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the fifth hypothesis is confirmed. It shows that self-regulation plays the mediating role between global reading strategy and reading proficiency.

H6: As indicated in Table , there is a significant impact of problem-solving strategy on self-regulation (β = .0288). Moreover, there is a significant impact of self-regulation on reading proficiency (β = .12, t = 2.58). The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the sixth hypothesis is approved. It shows that self-regulation plays the mediating role between problem-solving strategy and reading proficiency.

H7: A significant impact of support reading strategy on self-regulation (β = .0192) and a significant impact of self-regulation on reading proficiency (β = .12, t = 2.58) has been settled. The significance level equals.001, which is lower than 0.05 (p > 0.001). So the last hypothesis is confirmed. It is established that self-regulation plays the mediating role between support reading strategy and reading proficiency.

Table 6. Summary of SEM modeling

5. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the causal relationship between three types of metacognitive strategy awareness (global, problem-solving and support) and reading proficiency by mediating role of self-regulation through structural equation modeling. As indicated by the coefficients obtained for the correlation paths in structural equation model (Figures and ), the three types of metacognitive strategy awareness were significantly related to each other and were also significantly related to self-regulation. Global reading strategy moderately correlated with self-regulation with coefficient of 0.32 (P < 0.001) and problem-solving and support reading strategies indicated moderate correlation coefficients of 0.24 and 0.16 (P < 0.001) with self-regulation. Moreover, self-regulation had a coefficient of 0.12 (P < 0.001) with reading proficiency. Participants who had higher scores in self-regulation strategies tended to have higher scores on the reading comprehension. However, no dominant direct correlation was detected between the three types of strategies and reading proficiency.

The findings here can explain occasionally contradictory findings in different contextual situations between metacognitive reading strategies and reading proficiency. (Cohen & Macaro, Citation2007; Jafari & Shokrpour, Citation2012; Koda, Citation2007; Korotaeva, Citation2012; Pammu et al., Citation2014; Sheorey & Mokhtari, Citation2001; Tavakoli, Citation2014; Zare, Citation2013; L. Zhang, Citation2014; L. J. Zhang, Citation2010). The effectiveness of metacognitive strategic knowledge on reading achievements can vary depending on L2 learners’ resources of self-regulatory skills because in this study, MC affected reading proficiency only through self-regulation while no direct correlation was observed.

The mediating role demonstrated here for self-regulation is in accordance with the call by some SRL theoreticians to adjudge metacognition and self-regulation capacities of learners as interacting with each other within certain broad potentialities such as self-regulated action proposed by Kaplan (2008). In such delineation, learners’ awareness and control over strategies of language learning or language use does not suffice for regulation of learning. Rather, other aspects of regulating self including social, motivational and affective regulations need to be adjoined to skill-related strategies to yield successful learning. The concurrence between metacognition, self-regulation and self-regulated learning as three types of cognitive control processes has been accentuated in L2 reading development, too (Baker & Beall, Citation2009).

The findings of the study also afford further empirical support for the integrated and dynamic models of SRL. While acknowledging the important role played by complexity in illustrating the nature of regulating learning, Oxford (Citation2017) proposed that learners’ sociocultural context and psychological inner context be brought together within strategic self-regulated model to be functional for lasting achievements. She asserted that “learning strategies are part of complex systems—the contexts inside us and the contexts outside, all operating dynamically” (Oxford, Citation2017, p. 170). According to this view, cognitive, social, motivational and emotional strategies interact with each other in self-regulation of learning. Therefore, the integration and regulation of all these aspects of self are essential for the thriving learning.

In criticizing the efforts to present an integrative perspective of SRL in second language development, Thomas and Rose (Citation2019) called for disentangling language learning strategies research from SRL studies speculating that strategic learning is commonly used in other regulated situations like formal education settings. A reasonable remonstrance that might be posited in response to this argument is that the ultimate goal, even in “other-regulated” learning typical of formal instructions, is to help learners internalize scaffolded learning as “self-regulated” for their future learning. Thus, the attempt to raise the awareness and control of language learners over skill learning strategies detached from psychological and sociocultural contexts of self-regulation will not come out functional.

6. Conclusion

The mediating role of self-regulatory skills in the effectiveness of metacognitive strategies in reading proficiency development substantiated in this study indicates that strategy instruction by itself cannot ensure a high level of reading proficiency. Rather, self-regulatory skills which comprise a wide range of mental arrangements including motivational, emotional and social allocations determine the effectiveness of cognitive and metacognitive skills. This finding attests to the complexity perspective towards skill development which has been nurtured by some strategy experts. The practice of integrating such a complexity into language teaching curriculum and whether language teachers will feel competent and remain adherent to the requirements of such an integrative approach make up the main practical challenges in language teaching methodology and material development. While the present study adopted a narrow focus in modeling the dynamicity between metacognitive reading strategies, reading proficiency and self-regulatory skills, a more extensive coverage of language skills in the context of emotional, motivational and behavioral self-regulation is demanded for future research.

The dynamic and integrated procedures involved in SRL of language skills have a claim for further research where fair amount of attention is paid to emotional, motivational and social aspects of strategy learning and use. Through innovative methods, the efficacy of second language learners’ strategic knowledge in developing listening, speaking, reading, writing, vocabulary and grammar needs to be explored in relation to discriminating inner psychological factors such as their age and personality traits within different cultural and educational settings. Teachers’ awareness of this dynamism among a long list of variables must be raised. They must be held committed to provide opportunities in which overall self-related learning skills are promoted.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Davoud Amini

This article is the report of an MA thesis project carried out at Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University in Iran. Davoud Amini is assistant professor of TEFL at Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University. His areas of interest are psychology of second language acquisition and second language skills. He has published books and articles in these areas. Currently, he is the head of the English Department at Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University. Mostafa Hosseini Anhari is MA in TEFL. He is interested in second language learning strategies. Abolfazl Ghasemzadeh is associate professor of Educational Administration at Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University. His main research interest lies in educational leadership, administration, and human resource development of educational institutions. He has published over 50 journal papers in these areas.

References

- Alhaqbani, A., & Riazi, M. (2012). Metacognitive awareness of reading strategy use in Arabic as a second language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 24(2), 231–255. nflrc.hawaii.edu

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1998). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Anderson, N. J. (2002). The role of metacognition in second language teaching and learning. ERIC Digest, EDO. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics.

- Ardasheva, Y. (2016). A structural equation modeling investigation of relationships among school-aged ELLs’ individual difference characteristics and academic and second language outcomes. Learning and Individual Differences, 47, 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.02.010

- Aryee, S., Srinivas, E. S., & Tan, H. H. (2005). Rhythms of life: Antecedents and outcomes of work-family balance in employed parents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.132

- Baker, L., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Cognitive monitoring in reading. In J. Flood (Ed.), Understanding reading comprehension (pp. 21–44). International Reading Association.

- Baker, L., & Beall, L. C. (2009). Metacognitive processes and reading comprehension. In S. E. Israel & G. G. Duffy (Eds.), The handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 373–388). Routledge.

- Cohen, A. D., & Macaro, E. (2007). Language learner strategies: Thirty years of research and practice. Oxford University Press.

- Dinsmore, D. L., Alexander, P. A., & Loughlin, S. M. (2008). Focusing the conceptual lens on metacognition, self-regulation, and self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9083-6

- Dörnyei, Z., & Skehan, P. (2003). Individual differences in second language learning. In C. Doughty & M. Long (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 589–630). NY.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah.

- Flavell, J. H. (1976). Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), The nature of intelligence (pp. 231–235). Erlbaum.

- Flavell, J. J. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

- Fox, E., & Riconscente, M. (2008). Metacognition and self-regulation in James, Piaget, and Vygotsky. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9079-2

- Graves, M. F., Juel, C., & Graves, B. B. (2001). Teaching reading in the 21st century. Pearson Education.

- Griffith, P., & Ruan, J. (2005). What is metacognition and what should be its role in literacy instruction. In S. Israel, C. C. Block, K. Bauswerman, & K. Kinnucan-Welsch (Eds.), Metacognition in literacy learning (pp. 3–18). Erlbaum.

- Griffiths, C. (2019). Language learning strategies: Is the baby still in the bathwater? Applied Linguistics, 40(1), Forum, 1–6. doi:10.1093/applin/amy024

- Hadwin, A. F., Jarvela, S., & Miller, M. (2011). Self-regulated, co-regulated and socially shared regulation of learning. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 65–84). Routledge.

- Hirata, A. (2010). An exploratory study of motivation and self-regulated learning in second language acquisition: Kanji learning as a task focused approach [Unpublished master thesis]. Massey University.

- Jafari, S. M., & Shokrpour, N. (2012). The reading strategies used by Iranian ESP students to comprehend authentic expository texts in English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 1(4), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.4p.102

- Kaplan, A. (2008). Clarifying metacognition, self-regulation, and self-regulated learning: What’s the purpose? Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 477–484. doi:10.1007/s10648-008-9087-2.

- Kavani, R., & Amjadiparvar, A. (2018). The effect of strategy-based instruction on motivation, self-regulated learning, and reading comprehension ability of Iranian EFL learning. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1556196. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1556196

- Koda, K. (2007). Crosslinguistic constraints on second language reading development. Language Learning, 57(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.101997010-i1

- Korotaeva, I. V. (2012). Metacognitive strategies in reading comprehension of education majors. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 1895–1900. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/procedia-social-and-behavioral-sciences

- Maftoon, P., & Tasnimi, M. (2014). Using self-regulation to enhance EFL learners’ reading comprehension. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 5(4), 844–855. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.5.4.844–855

- Mbato, C. L. (2013). Facilitating EFL learners’ self-regulation in reading: Implementing a metacognitive approach in an Indonesian higher education context [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Southern Cross University.

- Mohseni, F., Seifoori, Z., & Ahangari, S. (2020). The impact of metacognitive strategy training and critical thinking awareness-raising on reading comprehension. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1720946. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1720946

- Mokhtari, K., Dimitrov, D. M., & Richard, C. (2018). Revising the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (MARSI) and testing for factorial invariance. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(2), 219–246. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.2.3

- Mokhtari, K., & Reichard, C. (2002). Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.249

- Mokhtari, K., & Sheorey, R. (2002). Measuring ESL students’ awareness of reading strategies. Journal of Developmental Education, 25(3), 2–10. https://ncde.appstate.edu/jde

- Morshedian, M., Hemmati, F., & Sotoudehnama, E. (2017). Training EFL learners in self-regulation of reading: Implementing an SRL model. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 33(3), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2016.1213147

- Oxford, R. (2017). Teaching and researching language learning strategies: Self-regulation in context. Routledge.

- Pammu, A., Amir, Z., & Maasum, T. (2014). Metacognitive reading strategies of less proficient tertiary learners: A case study of EFL learners at a public university in Makassar, Indonesia. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 118, 357–364. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/procedia-social-and-behavioral-sciences

- Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(422). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

- Panadero, E., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2014). How do students self-regulate? Review of Zimmerman’s cyclical model of self-regulated learning. Anales De Psicologia/Annals of Psychology, 30(2), 450–462. http://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/analesps.30.2.167221

- Radi Arbabi, H. (2013). The relationship between critical thinking, self-regulation and EFL students’ writing skills at Bu-Ali Sina University [Unpublished Master Thesis]. Bu-Ali Sina University.

- Rose, H. (2012). Reconceptualizing strategic learning in the face of self-regulation: Throwing language learning strategies out with the bathwater. Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amr045

- Rose, H., Briggs, J. G., Boggs, J. A., Sergio, L., & Ivanova-Slavianskaia, N. (2017). A systematic review of language learner strategy research in the face of self-regulation. System, 72, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.12.002

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., &, King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. doi:10.3200/JOER.99.6.323–338.

- Schunk, D. H. (2008). Metacognition, self-regulation, and self-regulated learning: Research recommendations. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9086-3

- Sheorey, R., & Mokhtari, K. (2001). Differing perceptions of reading strategy use between native and non-native college students. In R. Sheorey, K. Mokhtari, & R. S. Kouider Mokhtari (Eds.), Reading strategies of first and second language learners (pp. 131–141). Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc.

- Souvignier, E., & Mokhlesgerami, J. (2006). Using self-regulation as a framework for implementing strategy instruction to foster reading comprehension. Learning and Instruction, 16(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.12.006

- Tavakoli, H. (2014). The effectiveness of metacognitive strategy awareness in reading comprehension: The case of Iranian University EFL students. The Reading Matrix, 14(2), 314–336. http://www.readingmatrix.com/files/11-24o5q41u.pdf

- Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2016). A questionnaire-based validation of multidimensional models of self-regulated learning strategies. The Modern Language Journal, 100(3), 674–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12339

- Thomas, N., & Rose, H. (2019). Do language learning strategies need to be self-directed? Disentangling strategies from self-regulated learning. TESOL Quarterly, 53(1), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.473

- Zare, P. (2013). Exploring reading strategy use and reading comprehension success among EFL learners. World Applied Sciences Journal, 22(11), 1566–1571. doi:10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.22.11.1493.

- Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning (SRL) in second/foreign language. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 883–897). Springer.

- Zhang, L. (2014). A structural equation modeling approach to investigating test takers’ strategy use and reading test performance. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 16(1), 153–188. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/main-editions-new/a-structural-equation-modeling-approach-to-investigating-test-takers-strategy-use-and-reading-test-performance/

- Zhang, L. J. (2010). A dynamic metacognitive systems account of Chinese university students’ knowledge about EFL reading. TESOL Quarterly, 44(2), 320–353. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2010.223352

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social-cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2001). Theories of self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview and analysis. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (2nd ed., pp. 1–37). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2011). Self-regulated learning and performance: An introduction and an overview. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 1–12). Routledge.