Abstract

Access to higher education is essential to the achievement of social justice and economic development of a society. This study examines differences in the status quo of the equity of college admission examinations between China and the US by comparing news reports in the two countries. Interesting differences were revealed between the two media. China Daily centered more densely on equality in opportunities of exam taking and was inclined to inquire into how its college entrance exam is connected with dominant and pro forma inequality and the restraining force of policy associated with starting point equity, while the New York Times was concerned more on process equity and outcome equity, aiming to level off existing and potential disparities by detecting mechanisms of discrimination more deeply rooted and implicit in the implementation of the system. It is believed that the findings can lend a more in-depth understanding of the approach to social realities of educational equity in the two countries and hopefully provide useful implications for policy formulation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This research investigates how educational equity is perceived and constructed in the public discourse of China and the US. News reports from the two countries were compared, which revealed interesting differences between the two countries. The Chinese media was found to tend to focus on equality in exam-taking opportunities, how its college entrance exam was connected with dominant and pro forma inequality, and how policy framed starting point equity; the New York Times was concerned more on process equity and outcome equity, aiming to level off existing and potential disparities by detecting mechanisms of discrimination more deeply rooted and implicit in the implementation of the system. These findings can give us a better contextualized understanding of the social realities of educational equity and provides useful implications for policy formation.

1. Introduction

Educational equity has been widely acknowledged as a vital foundation for the promotion of social justice as well as sustainable economic and social advancement. Higher education, an important sector in education, is vital to a nation’s continued social and economic progress. Creating opportunities for equal access to higher education contributes to economic competitiveness, social stability, and cultural richness as well as private benefits such as higher salaries, better employment, and social mobility, and improved quality of life. Therefore, access to higher education is essential to the achievement of social justice and economic development of a society. The past decades have witnessed increasing importance attached to the proper management of access to higher education as a tool of government policy (e.g., Green et al., Citation2003; Ross & Lin, Citation2006; Spreen & Vally, Citation2006; Zhang & Kong, Citation2009). China and the US have been highly concerned about the role of college admission exam in achieving educational fairness and social equality in general. Despite significant progress achieved in the two countries in maximizing access to higher education, particularly with regard to enrolment expansion to social groups that are underprivileged, discussion has been going on as to how newly-emerging issues can be detected and addressed in educational reform.

This investigation aimed to inquire into Chinese and American concepts of educational equity and quality, using insight from a specific case study of media discourse on college entrance examinations. Media-based discourse, having been used extensively in areas such as political science and sociology, can provide a basis for policy decisions which have an impact on the shape of their societies, particularly in opportunities for social mobility (Eggins, Citation2010). But it has rarely been used in education studies. Therefore, this study conducted an in-depth comparison of the opinions given by reports of Chinese and American media concerning the equity of college admission test to complement the contextualized conceptualization of educational equity. It is believed that a better understanding of the approach to social realities of educational equity in the two countries and a contextualized understanding of the phase of development in achieving educational equity and conceptualization of the term can provide useful implications for policy formulation.

2. Conceptualization of equity

“Educational equity,” often used interchangeably with “educational equality,” entails the realization of equal educational rights and opportunities, equal access to education resources and fair treatment for all members of a society. An essential characterization is fairness which basically means that personal and social circumstances (e.g., gender, socio-economic status or ethnic origin) should not be an obstacle to achieving educational potential (OECD, Citation2007). Distinctions have been made between “equality” and “equity” in academic work. The former promotes free treatment for all and guarantees continuation of initial inequalities associated with different starting points (Maiztegui Oñate & Santibanez-Gruber, Citation2008). It may result in outcomes that are advantageous to some and disadvantageous to others. The latter emphasizes achieving results or outcomes of policies and practices that benefit all. Castelli et al. (Citation2012) propose a broader conceptualization, contending that it must both include and transcend the limited practices of equality which theoretically are not necessarily “fair,” and recognize the existence of unequal treatment in education processes and disadvantaged starting points. Such a difference is also present at the political-institutional level. For example, the initial prerequisite of the European Gerese project was that equity distinguishes between fair and unfair equalities and inequalities (Bottani & Benadusi, Citation2006). This indicates that delicate scrutiny can help conduct more comprehensive evaluation and offer an insightful perspective on the outcome of social treatment.

Such distinction may imply different stages of development in different social settings. Nordstrum (Citation2006) contends that as equality in education means sameness for all in all aspects such as funding and participation, the notion is more applicable to developed countries where educational opportunities are made accessible to all. But since past circumstances may not have been equal, just action is needed to restore fairness into the situation, thus making the case for “equity” which embeds the need for additional measures to even the playing field (Castelli et al., Citation2012). It speaks to a system that targets through equitable redistributive policies those who start at a disadvantage. In other words, equity is relevant to such places where equality in education is in question and those who are poor are left behind in quality schooling.

More complex views have evolved. In Eggins (Citation2010), there exist two different conceptions of equality: one is a formal equality of identical treatment for all; the other is the view that inequalities are acceptable if they produce advantages for the less favored members of society. Castelli et al. (Citation2012) suggests the inclusion of efficiency and quality and put forward three pragmatic dimensions: 1. Equity as equal opportunities for all; 2. Equity as equal treatment for all; 3. Equity as equal results for all. The first dimension takes into account of multifarious factors connected with students’ access to education. Equity as equal treatment for all puts stress on the elimination of all possible forms of discrimination that are harmful to people, especially those that are “deeply rooted” or “implicit” in the system” (p. 2246). The third dimension focuses on the objectives and results of existing preventive and compensatory measures. The above three dimensions of equality can translate roughly into starting point equity, process equity, and outcome equity as proposed by Husen (Citation1990) and fall coherently under a general principle of equity. This tri-dimensional framework of “equity” as equal opportunities, equal treatment, and equal results represents a comprehensive conceptualization of the term and provides a constructive perspective for more systematic examinations of the realization of educational equity in specific contexts.

3. Equity in higher education: China and the US

Scholars from both countries have been studying the role of college entrance exam in realizing social equality from perspectives including economics, policy, law, culture, education, and ethics. The most noticeable expansion of higher education systems are found in the less developed but rapidly rising nations (Eggins, Citation2010). In China, high school graduates are mostly admitted into universities through taking the national College Entrance Examination (CEE) (called Gaokao in Chinese). In the socioeconomic context of marketization since the late 1980s, China has gone through a transition from elite to mass higher education spurred by a radical expansion policy in 1999 (J. Li, Citation2009; Li & Lin, Citation2008; Li et al., Citation2014). The admission rate rose from 3.5% in 1991 to 34.5% in 2013, with over 27 million students enrolled in the year (Ministry of Education, Citation2014). Strenuous efforts have been made to reduce regional differences and urban-rural gap, such as greater investment in educational resources and increasing greater quota to remote regions in college admission. Nevertheless, the current system has been questioned on several grounds. The college entrance exam per se has also been under criticism for its ambiguous reflection of college admission standard, insufficient evidence for structural and content validity, as well as failure to represent fully the quality of students (Zhou, 2010). There also exist contemporary forces pushing toward rising inequalities. Students from groups with more cultural, social and economic capital have been found to have greater access to enrollment opportunities (W. Li, Citation2007; Yang, Citation2006; Zhang, Citation2013). Issues such as fair educational opportunities for underdeveloped regions, low-income families, and immigrants remain thorny (Chen, Citation2011; H. Liu, Citation2006; B. Liu, Citation2010). As claimed by Wang (Citation2011, p. 277), the current mechanism is “fundamentally flawed” which excludes certain social groups from fair competition.

In the US, the federal government has also resorted to setting macro targets and strategic laws and regulations to safeguard educational equity. A major criticism of the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), the most predominately used college admission exam, is its connection with the increasing difficulty for some social groups to receive higher education. Factors including transgenerational transmission of education, race, gender, and legacy status, family income, the exam content have all been found to be correlated with test results (Ermisch & Del Bono, Citation2010; Freedle, Citation2002; Hurwitz, Citation2011; Kahlenberg, Citation2010; Machin & Murphy, Citation2010; Nurnberga et al., Citation2012; Rosser, Citation1989; Veronica & Wilson, Citation2010; Young, Citation2003). A project has been launched by the College Board to improve the construct validity of the SAT to reduce equity gap between ethnic groups (Sternberg, Citation2006). It has also been pointed out that a greater emphasis on test scores in college admission is bolstered by class-based polarization. This vicious cycle of exclusion and adaptation “intensifies and expedites the escalation of class inequality” (Alon, Citation2009, p. 166). The use of affirmative action in college admissions has also been supported by various studies (e.g., Pike, Citation2007), in view of its effect of promoting greater interaction among diverse groups and reducing inequality. The general trend is a transition from the priority given to “inherited merit” through a “commitment to formal equality”, towards the adoption of affirmative action for under-represented groups (Clancy & Goastellec, Citation2007, p. 136). A strong conviction is that the concept of justice must be applied to all citizens in the country (Castelli et al., Citation2012).

It would be interesting to carry out horizontal comparisons between the two nations to find out similarities and differences in the way educational equity is conceptualized in effect. As put forward by Clancy (Citation2006), reliable and up-to-date comparative data can inform the evolvement, changing levels and measures in attainment of equal access to higher education, and help the system identify the targets of opportunity, evaluate policy initiatives, and borrow policies to reduce social inequalities. In this case, media, which is inevitably involved in its own way in policymaking, provides a unique perspective on the continuously changing social environment and interpretations of social issues.

4. News discourse: interplay with reality

The Media, as a pervasive social practice, are foundational to “the symbolic landscape” within which people make sense of the world and their place in it” (Hodgetts & Chamberlain, Citation2009, 843). They assume an important role in reflecting and affecting which and when issues are important for the public and policymakers (Soroka, Citation2003). As stated by Bird and Dardenne (Citation1988, p. 70), they are “orienting, communal and ritualistic’ and “endows events with artificial boundaries constructing meaningful totalities out of scattered events.” Hence, any transformation into news texts is consonant with the ideological consensus of a given society or culture through the conscious selection of the situational context and involves subjective or group-based presuppositions of norms, values, goals, and interests (van Dijk, Citation1988; Fairclough, Citation1995). Issues are framed to an audience in such a way as to clearly define a specific “problem” that needs to be addressed, to increase public perception of the importance of a topic, and to promote causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation (Altheide, Citation1997; Entman, Citation1993).

Empirical agenda-setting research has demonstrated powerful links among media subjects and content, public concern, social reality, and policymaking across a wide variety of issues. The media can draw and sustain public attention to particular issues, establish the nature, sources, and consequences of policy issues in ways that fundamentally change the attention paid to those issues as well as the different types of policy solutions sought (Soroka, Citation2003). They are contributive to maintaining social order and system by performing functions typically including surveillance, interpretation, linkage, transmission of values, and entertainment (Bonvillain, Citation1993; Dominick, Citation1994). Topic selection, quantitative increase, and changes in content represent an integral part of the processes shaping public opinion, making it possible to track changes and development and have historical understanding of social affairs (Merriam, Citation1998; Pavelka, Citation2014). The frequency of media reports on certain events can measure not only the frequency of those events in reality, but the intensity and change of beliefs in building up the theoretical foundation of boosting human action (Floriscu, Citation2014).

News discourse, a dynamic representational discourse where values are formed, reflected and disseminated, observations and interpretations of social events are distributed, and meanings are produced and inherited in specific, political, and cultural context, represents an important social force at play for social dynamics. It can provide a unique perspective on the continuously changing social environment and approach to social issues. Therefore, this paper aims to find out whether and how mainstream media in China and the US differ in reflecting and shaping social ideology in connection with educational equity, to complement studies on population survey data (e.g., Zhang & Kong, Citation2009) or case studies (e.g., Halai, Citation2011). Specifically, through examining how equity is addressed from the perspective of the way specific issues are framed, and comparing the content, perspective and scope of mainstream media reports on college entrance exam, we can be further informed of the status quo, focus of concern and the conceptualization concerning educational equity in the two countries. It is also hoped that some useful implications be yielded for the ongoing education reform in the two countries, particularly China, a developing nation confronted with more grave challenges in achieving educational equity and social equity at large.

5. Data collection

The news media compared in this study were the New York Times and China Daily. The New York Times, founded by the New York Times Company, has the largest circulation among the metropolitan newspapers in the United States, and has been regarded within the industry as a national “newspaper of record” (The New York Times, Citation2016). It has had a presence on the Web since 1996, and has been ranked one of the top websites and the most visited newspaper site with more than twice the number of unique visitors as the next most popular site. China Daily, a state-run paper, has the widest print circulation of any English-language newspaper in China. The online edition of China Daily was established in December 1995, becoming one of the first major online Chinese newspapers.

Although it would be more ideal to compare New York Times with a Chinese newspaper, other major newspapers in China are also largely state-controlled. The New York Times has been characterized as taking liberal stands by Rasmussen Reports (2007) which has been confirmed by several articles published by the newspaper itself (e.g., 21 December 2015), especially with Bill Keller becoming its executive editor. The editorial policies of China Daily, which has been undergoing a transition from state-controlled to an integration with market power, distinguish itself from most Chinese language newspapers in being slightly more liberal (Heuvel & Dennis, Citation1993). Also, no other major newspapers in China provide access to electronic archive at their website and make keyword search possible. Although China Daily primarily serves those who are foreigners in China and those who wish to improve their English, and is pro-government and more conservative than the New York Times, any transformation into news texts reflects personal as well as general experiences, opinions and attitudes, and is consonant with the ideological consensus of a given society or culture through the conscious selection of the situational context (van Dijk, Citation1988; Fowler, Citation2007). As it is almost unrealistic to find newspapers comparable in all aspects in the two countries in view of the macrosocial settings, nature of newspapers and availability of discourse, China Daily was selected as the source of Chinese news discourse for this study to be compared with the New York Times.

The articles, dated between 2001 and 2016, were collected from the official websites of the New York Times (www.nytimes.com) and China Daily (www.chinadaily.com.cn) which allow keyword search. The selection was based on the following criteria. First, the tests searched for were “college entrance exam” and “Gaokao” in China Daily, and “SAT” in the New York Times. Another criterion adopted was that the articles should all revolve on “equity” “equality” and “fairness” in opportunities for higher education. Specifically, the keywords used for the search included various lexical forms of the three terms, namely “fair” “fairness” “fairly” “equal” “equality” “equally” “equity” “equities” and “equitable” “equitably.” The corpus obtained was then examined carefully and screened by selecting reports that centered on educational equity and excluding articles on other topics. The resulting data set consists of 121 reports in China Daily (including 89 news articles and 32 opinion pieces) and 56 (including 47 featured stories and 9 opinion pieces) in the New York Times. The comparison of the perception of educational equity was primarily based on discussions of how specific issues were approached by the two newspapers.

6. Analyses

6.1. Overall attitude toward CEE

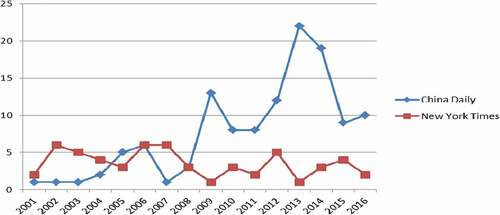

The distribution of these reports across the years was compared between the two newspapers to catch a glimpse of the general social context where these reports were produced. It can be seen in that the number of such reports in the New York Times was generally constant and did not fluctuate as drastically as those in China Daily across the past 16 years. China Daily showed a sharp rise since the year 2009, including 98 reports accounting for 83% of the total. This suggests that in recent years there has been a striking growth of attention in China to the fairness of higher education opportunities, which is likely to be a result of the nation attaching increasing importance to the improvement of people’s livelihood and the realization of equalization of public service.

The two media displayed apparent differences in the overall attitude towards the CEE. Thirty-nine reports in China Daily (32% of the total) were positive about the CEE: the general tone was that it is still the widely-accepted and most appropriate method of admission in China. Especially when the test takers far outnumber students enrolled by college, “the exam has guaranteed equal rights for everyone to receive education in institutions of higher learning” (21 June 2008); also, “still fair disadvantaged students can change their status and fate through the CEE” (27 December 2006). The support for this attitude in the reports can be summed up as follows: “there will never be absolute equality when it comes to a specific student” (3 August 2005); “government policies cannot guarantee a fair deal for every individual, but are designed to protect the interests of the majority” (3 August 2005). The exam is considered “the fairest criterion for admission” to college (7 July 2015). The underlying ideology was that individual interest is secondary to collective interest which should not be sacrificed in pursuit of the former. However, there was a lack of grounded discussion as to how the CEE guarantees the benefit of the majority or to challenge the tenability of using such a method of admission.

In contrast, the 56 reports of the New York Times were overall critical of the SAT. For example, it was pointed out that “the whole thing” has become “a foolish exercise” (9 April 2006). The validity of such test was challenged in several reports (e.g., 17 February 2001; 22 February 2006; 28 July 2002; 9 March 2014; 5 May 2015; 8 May 2015; 1 November 2015). It was criticized that reliance on SAT to rank students for college admission is not “compatible with the American view on how merit should be defined and opportunities distributed” (17 February 2001). More specific comparison will be presented below. It has to be noted that since the articles in the newspapers were written by different authors, it is likely that “equity” and “equality” were used interchangeably with no attribution of specific academic connotations. Therefore, academic distinctions will not be made on the journalistic use of the two terms in the following discussion.

6.2. Use of key terms

The use of the two terms in the two newspapers was summed up and compared (see Table ). More specifically, among the 143 occurrences of “equality” in China Daily, the majority (n = 89) were collocated directly with abstract stances of “education” regarding opportunities of exam taking, access to education, distribution of educational resources, emphasizing equal treatment as a principle to be safeguarded (e.g., [1]). It was not made clear how specific practices or educational realities are related to equity. In comparison, the majority of instances (n = 45) in the New York Times occurred with more concrete issues, including, exam prep, access to coaching, assessment of aptitude for people with and without disabilities, outcomes of SAT, number of opportunities for exam taking (e.g., [2]), scrutizing the specific situation that is potentially detrimental to equity or spotlight the actual inequities (e.g., [2]).

Table 1. Frequency of “equity” and “equality”

[1] Despite its shortcomings, the national university entrance examination system is considered the last line of defense for education equality in China. (China Daily, 19 August 2004)

[2] The percentage has more than doubled since 1990, amid a troubling inequity: Affluent students are far more likely than poor ones to have documented disabilities and therefore to receive accommodations (New York Times, 8 November 2003).

In [2], “documenting disabilities” and unrestricted exam taking were identified as causes of inequity with the rationale given unequivocally. China Daily evidently focused on equality as a static principle while the New York Times paid closer attention to the equity of specific practices. The following part will probe into the focal points of concern of the two newspapers (see Table ) related with educational equity, followed by a detailed discussion of these focal points within the framework of the tri-dimensional framework of educational equity.

Table 2. Topics related with educational equity

6.3. Respective unique topics

Some issues reported were found peculiar to the two newspapers, respectively.

6.3.1. China Daily

6.3.1.1. Children of migrant workers

Children of migrant workers are the disadvantaged group that has received most attention, for whom the basic right of taking the exam, not the result of the exam, is an issue of utmost importance. Currently, due to the regulation on residence registration, migrant workers are under many restrictions which prevent them from taking part in the CEE in the city where they live. This topic was covered densely in China Daily, as reported in 15 articles. As quoted in a report in September (2009), most children will give up the exam and choose to go to vocational schools or go straight to work instead. It was argued (26 April 2005) that: “the current household registration system is the last obstacle to achieving equal schooling rights for migrant workers’ children.” A report on 31 March 2011 stated clearly that the country is encouraging local governments to roll out plans to allow students to take the exam where they live rather than where they are registered. In this case, such discussions focusing on the exam-taking opportunity of these underprivileged children clearly concerns the starting point equity which may represent an important step to empower them to realize social mobility.

6.3.1.2. Provincial discrepancy in admission criteria

Regional discrepancy in cut-off score of college admission is another topic that stood out in China Daily. In China, the cut-off line and quota vary from province to province, the fairness of which has been called into question. For example, as argued in three reports (28 May 2008; May, 28, 2010; 29 August 2010; 12 December 2013; 16 November 2013; 26 May 2016): this system is unfair because it is much harder for highly qualified applicants in some provinces to enter competitive universities than for less stellar students from places like Beijing, Shanghai and Hainan. This has led to migration and house buying where the cut-off line is much lower to acquire local household residency so as to be qualified to sit the exam locally. The differential treatment of students from different provinces in admission has bred speculation targeting at achieving a greater chance of being admitted (3 August 2005). This indicates that outcome equity (chances of admission), in effect, is intertwined with controversy over starting point equity, i.e. the exam taking opportunity.

Overall, these two topics dealing with the dispute over differential treatments based on household residency revolved around equal opportunities for all, which is the gist of starting point equity. In particular, the offspring of migrant workers are disadvantaged, considering that they are not given the opportunity to sit the college exam at the place where they live. On the other hand, policies prescribing such differential treatments have a great impact on the change of being admitted, given the quota discrepancy, which ultimately takes a toll on outcome equity.

6.3.2. New York Times

6.3.2.1. Ethnic minorities

The New York Times covered ethnic minorities (primarily African Americans and the Latinos) frequently. On the one hand, the two groups lagging behind in SAT score and college admission has long been an uneasy topic. On the other hand, there has been some voice for limiting Asian-American admissions, considering the higher score and the rising population of this group on campus and the diminishing African-Americans on campus (e.g., 7 January 2007). The affirmative action formulated in the 1960s is mainly applicable to African Americans and the Latinos, not benefiting the Asian Americans in college admission who in reality often have to give place to the former. The focal point is not over the qualification of test taking, but the more practical issue of helping the disadvantaged group reach the criteria of college admission, or to be more direct, get a higher SAT score. As pointed out in three articles (22 February 2006; 27 February 2001; 14 October 2012; 27 June 2016), test score seems to have fossilized such discrepancies though. In other words, media attention to the connection between ethnic backgrounds and ultimate admission results represents a type of civic discourse on outcome equity in education.

6.3.2.2. Family background

The New York Times also highlighted directly the discrepancy in social hierarchy in connection with test result. Test result was statistically correlated with family income: “for every extra 1,000 a family earns, children’s combined math and verbal scores go up 12 to 31 points” (Feburary 22, 2006). Moreover, the SAT result was also found to be related to parents’ education (10 March 2012): the gap between parents with a master or higher degree and those who dropped out of high school was as huge as 272 points (21 September 2003). y. The report on 27 June 2016 points out that “The test measured family income not ability”. Such correlation between family backgrounds and test results reveals potential inequities implicit in the pursuit of higher education, which reveals the conccern of the media about outcome equity. In the light of such situations, it was suggested that the number of times the test can be taken a year be restricted to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor and test design be tilted to the poor, which can be seen as attempts to improve process equity. It was even proposed that such social variables be incorporated into the calculation of the SAT result to enhance the opportunity for the disadvantaged to gain access to higher education, so as to promote outcome equity.

6.4. Common topics

Apart from the above-mentioned aspects peculiar to the two media, respectively, a wide scope of topics were covered by both media, in different density and depth though.

6.4.1. Topic covered more densely in China Daily

6.4.1.1. Regional gap

China Daily carried 19 reports on the gap between the urban and rural areas and between the east and west. A term that emerged repeatedly was the allocation of educational resource, collocated with words including “disparity” “gap” “uneven” “unfair” “lack” “limited” “unbalanced” “imbalance” “inequality.” In other words, the two gaps were largely attributed to the allocation of educational resources, marking discrepancies in starting point equity for college admission. In a report on 22 July 2009, it was made clear that to address such issues; the nation has promulgated affirmative policy and granted more favor in college admission and the test score to further realize outcome equity.

In the New York Times, regional discrepancy, reported four times, was exactly the opposite of China. In a report on 27 August 2003, students from the rural and big cities have been behind students from the outskirts in SAT score; the distinction is outstanding in the metropolitan area which includes the central city and its suburbs. This discrepancy is intertwined with the racial issue: the outskirt is mostly habited by the white middle and upper class while African Americans and other ethnics tend to live in the urban area. For example, in a report on 24 January 2007, it was pointed out that students living in the city have better-educated parents and do not begin at the same starting line in the track event as students from the suburbs whose parents are comparatively better-educated. All this is in effect about discrepancy in the access to education resources between the rich and the poor, which is closely related with the result of the test and college admission and could put outcome equity in jeopardy.

6.4.1.2. Cheating

China Daily far outnumbered the New York Times in frequency of reports on test cheating (13 vs. 4). According to five of the articles, cheating was severe and in varied forms such as the use of hi-tech, bribing the proctor or official in charge, capitalizing connections and collusion with the teaching staff. It was emphasized that cheating has a great negative impact on fair play and the implication of teachers broke the bottom line of fairness of CEE. The prevailing view was to impose penalty such as disqualification of the candidate and making a record of student’s credit by way of maintaining fairness, which could promote process equity.

The other eight articles focused on cheating aimed at sitting the exam or obtaining the additional points, including: forging one’s nationality, taking part in the CEE with others’ ID or by abusing one’s power, counterfeiting one’s grade of learning to take part in the exam earlier. A shared assertion is that such speculation represents a loss of integrity and is detrimental to equality of CEE as a starting point for higher education, hence, should be punished severely.

The New York Times covered cheating in merely four articles. The form of cheating was comparatively less varied, consisting primarily of the use of text messaging, posting test questions online and using surrogate exam takers, hiring people to memorize or take picture of exam questions. The focus was laid on how the exam security company could find out cheating by resorting to technological and statistical analysis of the answer sheet, to identify the most egregious cases, not the borderline ones (27 March 2012). With regard to surrogate exam taker, students are required to provide photo which will be sent back to the school (12 October 2012). In sum, the reports emphasized detection as a step in reaching the goal of prevention, not on penalty, to ensure equity in the exam-taking process.

In brief, comparatively speaking, Chinese reports outnumbered the US in the reports on regional gaps and cheating, with different perspectives regarding the way equity is constructed within the parameter of equity of the high-stake college entrance exam.

6.4.2. Topic covered more densely in the New York Times

6.4.2.1. Content of the test

Thirteen articles dealt with this topic, calling into question a wide spectrum of issues concerning the validity of the SAT, including: inability of the SAT to provide directions for high school learning (22 February 2006); inappropriate and incomplete definition of “ability” (17 February 2001; 18 January 2004); being a test of test-taking ability and coaching (17 February 2001; 8 May 2015) poor predictability of job performance (4 February 2004); vagueness of the range of purpose of the test (7 January 2007); poor performance of many capable and creative candidates (9 April 2006). A debate was also carried out over whether the SAT should be a reflection of what is learnt at high school, or more geared to students’ ability and reduce the classroom content so as to reduce the racial gap (20 November 2008; 13 October 2006; 5 May 2015) with the purpose of improving fairness during the process of seeking higher education.

During the past decade, the SAT experienced two major changes. In 2005, the SAT adopted a new change, replacing verbal analogies with writing. The New York Times covered this change five times, scrutinizing potential drawbacks that may arise: being unfair to immigrants whose native language is not English (Lewin, 2002); being disadvantageous to non-suburban kids who have no sufficient aid with writing given the size of the class (13 March 2005); incapability of fairly foretelling one’s writing ability in college (McGrath, 2004); being meaningless for the improvement of writing and thinking (28 June 2002). A further revision of the test set to debut in the spring of 2016, which requires students to demonstrate in-depth knowledge of subjects they study in school. This change was reported in three articles (5 May 2015; 8 May 2015; 12 February 2016) which criticized the test for still emphasizing speed over subject knowledge and continuing being a norm-referenced exam ranking students rather than measuring what they actually know. In short, the ongoing inspection on the content of the exam concentrated not only on the validity of the test but also on fairness of the test for different groups of people, attempting to address process equity that is intertwined with differences in financial and racial backgrounds.

In comparison, there were only three reports in China Daily on the content of the exam: two on 11 June 2009 and 10 June 2014 mentioned briefly that some writing topics were a disadvantage to candidates in the rural area where education resources are scarce and those who are not familiar with the given topic; one on 26 October 2013 which reported on the washback effect of reducing English score in the college entrance exam. Relatively speaking, the content of the exam is not yet a focus of concern in China in the discussion over educational equity. Therefore, test validity seems to have received more attention from the American media as a factor connected with the promotion of equity in the process of exam taking.

6.4.2.2. Candidates with disabilities

Six reports in the New York Times revolve around accommodations for candidates with various disabilities. About 2% of the two million high school students who take SAT’s each year get some accommodations typically including extra time because of their documented disabilities (15 June 2002). The debate over this issue centers on three issues. Firstly, how should “disability” be defined? As physical problems and learning disabilities are both identified as disabilities (8 January 2011), students are asked both to provide authentication and proof that accommodations are needed during studies (4 November 2010). The second issue concerns how far to accommodate students with disabilities. It is to be decided how much additional time on a test fairly compensates for varied disabilities such as blindness, dyslexia and attention deficit order (15 June 2002). It has been feared that unmerited accommodations undermines the integrity of the exam (4 November 2010). The third issue concerns whether to flag the score on the score report. In 2003, after a lawsuit, the College Board cancelled flagging of scores obtained with accommodations to avoid stigmatizing the disabled. But a report on 15 June 2002 revealed that this change would “open the floodgates to families that think they can beat the system by buying a diagnosis, and getting their kid extra time,” and ultimately hurt the kids who do have real disabilities, because white affluent families can obtain accommodations more easily than other families. Therefore, discourse on social inclusion often got tangled with the protection of the interests of those who are financially and racially disadvantaged in terms of the process and outcome of exam taking. The implementation of compensatory treatment of people with disabilities could in effect give rise to speculations, which has complicated the process of educational equity.

China Daily only sparsely reported on the disabled in three articles which focused on the possibility of taking the exam. The disabled were given for the first time equal access to the same national standard exam in Beijing with the accommodation of providing large-size papers (7 June 2005). The report spoke highly of this new policy, stating that it gives the blind a greater control over the future. No in-depth inspection of the issue was carried out. But there was a call for more accommodation for all physically challenged people to have equal access to education, as quoted in reports on 3 December 2013 and 16 May 2015. Overall, limited attention was given to students with disabilities whose equal right of sitting the exam is not guaranteed. Existing measures aimed to make it possible for people with disabilities to take the exam to achieve starting point equity for this disadvantaged group who could be included in that.

6.4.2.3. Coaching

The New York Times carried six reports on coaching, all being special features. These reports challenged coaching by raising two sharp questions: is the SAT result a reflection of students’ aptitude or the amount of coaching (28 May 2006)? Is it fair for people who could not afford coaching (3 October 2004)? These questions were based on the fact that coaching could indeed improve test result and there existed a vast difference between the rich and the poor in this spending; hence, it has particular relevance to fairness in access to higher education. As satirized in an article on 15 July 2002, what the SAT measures accurately is who can afford coaching or costly private or public schools. Discussion on coaching mingled with the issue of financial disadvantage which related to starting point equity and ultimately undermined outcome equity.

In China, it is common for students to take part in various coaching lessons, but the ongoing talk has been around the excessive burden coaching has placed on students; its relevance to education equity has not become an issue of much contention in China Daily, except for a brief mentioning of poor families unable to afford tutors or special classes in a report on 7 December 2011. The possible connection of coaching with equity in higher education has not aroused considerable attention in China Daily.

6.5. Reform in the use of test score

Both media contended for a change to the overreliance on the standardized tests in college admission, on different grounds though. Rather than educational equity, China Daily tended to focus on the validity of the exam in terms of its washback effect on test-takers: 14 reports making a point of diversifying assessment, advocating more autonomy of students, alleviating the harm of exam-oriented education, and elevating students’ creativity. The center of concern is the impact of the CET on all-round development of students, not educational equity per se.

Nine articles in the New York Times appealed for cutting down the weight of the SAT in college admission. Apart from perspectives similar to those of China Daily, such as overreliance on the SAT which would cause damage to the entire education system, lack of diversity on college campus and balance in academic quality, and inadequacy in helping teachers and students to learn, the New York Times mainly revolved around its possible relevance to educational equity, pointing out that once scoring errors occur, the risk would be huge for the test taker. Some university presidents (17 February 2001) even recommended abandoning the SAT score in college admission, on the ground that the way the score is used contradicts the way value is defined and opportunity fairness. This discussion on the use of SAT scores was stemmed from the concern with outcome equity, that is, the possibility whether the results of admission discriminate certain candidates.

The conceptualization of educational equity in the way these topics were addressed will be compared and discussed below.

7. Discussions

7.1. Overall attitude to the test

The two media demonstrated contrastive attitude towards the test. China Daily was generally positive about the CET in terms of its contribution to educational equity. China’s large population and limited education resources seem to make it natural to give priority to the competitiveness and efficiency of the test as a means of selection which supposedly ensures equal footing for high school graduates. Under such circumstances, the propaganda is that interests of individuals should give way to collective interests and fairness in a more global sense. Also, it should be noted that China’s CEE is designed, implemented, and administered directly by the Ministry of Education of the country; its mainstream media are more or less centralized by the government although marketization has enabled major media outlets to cater more to audience demands (Zhao, Citation2006). Social conflicts seemed to be downplayed. There are two other factors to be considered. There has been the long-lasting impact of keju system (Imperial Examination System) through which officials were selected in ancient China. There is also a fear among the public that any other arrangements other than the CEE could be more unfair for disadvantaged groups. One may easily imagine the abuses of economic, social, and political powers in recommendation letters or any other alternative standards for college admission.

By comparison, the New York Times was much more critical of the exam per se as well as the implementation and use of it with regard to its role in the realization of educational equity. This can probably be accounted for on several fronts: the test is written and organized by College Board, a non-government organization; the mechanism is overseen by an independent watchdog called Fair & Open Testing; meanwhile, the social atmosphere of the New York Times is more liberal.

A consensus shared by the newspapers was the need to reform the test, specifically, to reduce the weight of the test in college admission, and improve the content and form of the exam; such a need was justified from two different perspectives though. On the other hand, unlike China Daily which placed stress on the viability of the test as a tool of assessment and its washback effect on the manner of learning and carried out little substantial debate on its connection with educational equity per se, the New York Times was more engaged in discussing how the current system can be redressed to enhance fairness of education.

Concerned as both countries were about the disadvantaged, as suggested by the two media, the detailed inquiry into the specific topics discussed in the two newspapers provides interesting insights into the status quo of educational equity concerning college admission test in China and the US.

7.2. Conceptualization of educational equity in China

China Daily emphasized equal rights for sitting in the exam and distribution of educational resources. In other words, phasing out obstacles to equal opportunities of taking the exam stood out as a key issue. It can be inferred that in the tri-dimensional framework of educational equity, China is more inclined to inquire into how the exam is connected with starting point equity, focusing more on the qualification to take the exam, less on the process of exam taking or the effectiveness of the CEE in getting more disadvantaged groups into college. The basic right of children of migrant workers has not been guaranteed; test takers with disabilities or financial disadvantages have not drawn considerable attention. The gap between the urban and the rural, the east and the west in equal access to higher education is associated with the unbalance of the country’s educational resource, which primarily include, in the Chinese context, the number of universities located in a province and college admission quota assigned to a province. In this sense, the regional inequality in college admission is directly linked to the uneven distribution of provincial quota arrangement for college admission which is province-specific. Migrant children are not allowed to take CEE when they stay in a city out of the province where they were registered.

This focus on starting point equity is closely connected with the cultural and social settings of China. In China, there is a tradition for the exam to be seen as a life-changing “tool” for success for students. For urban Chinese students, they need to go to a good university to secure a good career, while for rural students, they have to climb a long and steep ladder in order to move to the big cities in hope of having a better life. Gaokao is considered an extremely high-stakes test that can determine the fate of test takers after more than 10 years of hard study. Meanwhile, with a huge population and limited resources, education in a country as big as China is not as accessible as in countries like the US; competition in Gaokao is naturally much fiecer. The test held annually has being drawing considerable attention from the entire society. In a sense, ensuring equal opportunities to take the test has been of utmost importance in the effort to fulfill the promise of educational equity.

On the other hand, although news reports in China appear to have discussed less frequently “process” or “outcome” inequity, the admission system could be quite complicated. Within a province, it focuses directly on formal equity. Yet it becomes a different matter when operated across province. In China, disadvantaged groups are not necessarily small in size. Disadvantaged rural teenagers actually accounted for over half of the national population in their age group. Meanwhile, the population of China’s ethnic minorities is more than 110,000,000. China has operated preferential college admission policies (within provinces), as well as allocating more college admission quotas to minorities-concentrated provinces (across provinces), in order to reduce outcome inequality in college access. News reports studied here seemed to pay little attention to this preferential policy for college admission of ethnic minorities who can not only have points added to their CEE scores for admission to university, but also be eligible for a preparatory year of college before beginning to ensure they are ready for college admission. Some ethnic minorities, such as Mongolians, Uyghurs, Tibetans, and others who have an ethnic script can take the college entrance examination in the script of their native language. Also, some key universities are asked to allocate admission quotas specifically to poverty-driven areas. These issues have not become matters of public attention, compared to other issues concerning starting point equity.

On the other hand, provincial quotas, household registration, and regional differences in cut-off admission score also have given rise to issues concerning process and outcome equity, in particular, cheating in test-taking qualification. Relevant coverage in media, in essence, reflects the national strategic emphasis on fairness of opportunity (which is roughly equivalent to equality of exam-taking opportunities as the key to education equity), i.e. starting point equity. In turn, focus on these issues can be, at least partly, attributed to the fact that Chinese universities, despite reforms in the recent decade, mostly admit their students solely on the basis of CEE scores, making it an extremely high-stake exam, which may result in many parents being willing to be opportunists to gain benefits for their children.

Another reality that stands out in China Daily was an orientation towards the macro policy which is deemed as of central importance in ensuring fairness of opportunities; specific regulations and the appropriateness of existing practice were seldom scrutinized. It can be said, the Chinese media has been largely concentrated on dominant and pro forma inequality and the restraining force of the policy, hardly with support of empirical data and account of more recessive social effects initiated by issues concerning specific validities of the test. In other words, although preoccupied primarily with various issues concerning starting point equity, China is yet to spare more effort to detect, scrutinize, and fight potential process or outcome inequity.

7.3. Conceptualization of educational equity in the US

Comparatively speaking, the New York Times was clearly more concerned about the complex manifestations of “equity” with respect to the specific role the exam plays in the realization of admission to college. Analyses of the coverage of relevant topics reveal that the US appears more committed to outcome equity. It is preoccupied with whether the way the test is administered is fair for different social groups, particularly the disadvantaged. It is also devoted to identifying directly various social factors, such as race, family income, parents’ education, which help foresee the SAT score; prudence has been shown to ensure equal test preparation so that opportunities for higher education can be brought about. The newspaper went into depth discussing whether different social groups are able to go to college, particularly competitive ones, as a result of taking the exam. Meanwhile, the content and validity of the exam were also examined to secure the realization of fairness for different social groups and avoid excessive emphasis on its competitiveness.

Besides, the New York Times also addressed the issue of process equity, looking into the underlying value, specific rules, and technical support in test implementation with respect to whether and how equity can be materialized. The fact that American universities tend to take into account a variety of other factors (such as reference letters, community services, and extra-curricular skills) besides SAT scores to admit students has made its college admission a comparatively less competitive system, allowing the public and the media to be concerned about more concrete issues to further refine the implementation of the system per se. In shorter terms, the US appears more devoted to leveling off both existing and potential disparities caused by unequal and differential starting points through detecting mechanisms of discrimination more deeply rooted and implicit in the implementation of the system as well as the realization of equity in test results.

It can be said that starting point equity has largely been materialized in college entrance examination; also, given that admission decisions are not merely based on the SAT score, there has been an intense and constant attention to test results and the effect on admission. Issues concerning whether there exist bias or covert inequity in the process and outcome are discussed and debated lively in the media. In other words, whether and to what extent socially disadvantaged groups can be fairly represented on college campus is intimately connected with the result of the balance game of multifarious interests and social forces. The ongoing scrutiny in the news discourse may reflect the fears in the public about limited accessibility of opportunities for social advancement and widening class divisions.

8. Conclusions

More or less biased as the two newspapers are in agenda setting and stance, they do reflect to various degrees the national sentiments towards particular educational issues. China appears more concerned with starting point equity, focusing more on the availability of equal opportunities to take the exam. In other words, equality of exam-taking opportunities is, in a sense, treated as the key to educational equity. Less attention has been paid to the process of exam taking or effectiveness of the exam in giving disadvantaged groups greater access to higher education. Comparatively speaking, the US is more committed to process equity and outcome equity, probing further into the latent inequity in employing the exam as a yardstick for college admission, and detecting discrimination more deeply rooted and implicit in the implementation of the system which prevents socially disadvantaged groups from being fairly represented on college campus. By and large, starting point equity has been effectuated in college entrance examination in the US; covert inequity in the process and outcome is in the spotlight in public discourse. Such discrepancies are closely connected with the complexity of cultural and social settings as well as college admission systems in the two countries.

Although educational equity is a long-term goal to be attained in both countries, it can be said that the US, already beyond starting point equity, has gone further in the pursuit of educational equity. There exist in China wide arrays of problems or risks that have not received much attention, particularly those potential issues that may emerge in the phases of process equity and outcome equity when policy is formulated to ensure starting point process.

Developing countries probably can work towards equity from a more developmental perspective. In order to materialize educational equity to a maximum extent and go beyond pro forma equity, it is far from enough to set starting point equity as the only goal to be achieved. In formulating and evaluating educational policies, more comprehensive, substantive, and in-depth investigation and discussion and ambitious efforts are called for to transcend starting point equity and see to it that process equity and outcome equity are taken into account. It has to be admitted that major discrepancies exist between the two countries and newspapers in social and ideological settings; additionally, given the stage of economic development and the size of disadvantaged population, China can only be able to, after a time-lag for years, follow the American stages to focus on process and outcome inequality. It also has to be noted that there may be biases in these two newspapers in terms of the way the topics are addressed. Nevertheless, the issues directly addressed or alluded to in the two media are thought-provoking and can at least lend us some insights in terms of the measurement of educational equity and the policy-making when compensating for social inequities and exclusion and guarantee better opportunities for disadvantaged individuals or groups. Other aspects of educational equity can also be examined from the perspective of media discourse. Besides, future research can look into the public sentiments involving educational equity as represented in other types of media (e.g., we media) in the Web 2.0 era so as to obtain richer insights, not only from mainstream media but also from other walks of life, into how educational equity is perceived and approached in different cultures.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ming Wei

Ming Wei is an associate professor at the School of International Studies, the University of International Business and Economics in China. She previously taught at Beijing Foreign Studies University from 1999 until 2004 when she started to pursue her doctoral degree at the Oklahoma State University in the US. Her research interest is currently the discourse approach to various topics in educational, social and cultural settings.

References

- Alon, S. (2009). The evolution of class inequality in higher education: Competition, exclusion, and adaptation. American Sociological Review, 74(5), 84–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400503

- Altheide, D. L. (1997). The news media, the problem frame, and the production of fear. The Sociological Quarterly, 38(4), 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1997.tb00758.x

- Bird, E., & Dardenne, R. (1988). Myth, chronicle and story: Exploring the narrative qualities of news. In C. James (Ed.), Media, myths, and narratives: Television and the press, (pp. 67–86). Sage Publications.

- Bonvillain, N. (1993). Language, culture and communication: The meaning of messages. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- Bottani, N., & Benadusi, L. (eds.). (2006). Uguaglianza ed equità nella scuola. Erickson.

- Castelli, L., Ragazzi, S., & Crescentini, A. (2012). Equity in education: A general overview. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 2243–2250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.194

- Chen, J. (2011). Analysis on the trend of reform of university entrance examination system. Educational Research, 10, 64–68.

- Clancy, P. (2006). Access and equity: National report of Ireland. An internal paper, New Century Scholars Program of Fulbright.

- Clancy, P., & Goastellec, G. (2007). Exploring Access and Equity in Higher Education: Policy and Performance in a Comparative Perspective. Higher Education Quarterly, 61(2), 136–154.

- Dominick, J. (1994). The dynamics of mass communication. McGrow-Hill.

- Eggins, H. (2010). Access and equity: Comparative perspectives. Sense Publishers.

- Entman, R. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Ermisch, J., & Del Bono, E. (2010). The link between the education levels of parents and the educational outcomes of Teenagers. The Sutton Trust.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. Edward Arnold.

- Floriscu, O. (2014). Positive and negative influences of the mass media upon education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 149, 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.08.271

- Fowler, R. (2007). Language in the news. Routledge.

- Freedle, R. (2002). Correcting the SAT’s ethnic and social-class bias: A method for re-structuring SAT scores. Harvard Educational Review, 72(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.73.1.8465k88616hn4757

- Green, A., Preston, J., & Sabates, R. (2003). Education, equality, and social cohesion: A distributional approach. Compare, 33(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305792032000127757

- Halai, A. (2011). Equality or equity: Gender awareness issues in secondary schools in Pakistan. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.012

- Heuvel, J. V., & Dennis, E. E. (1993). The unfolding lotus: East Asia’s changing media: A report of the freedom forum media studies center at Columbia University in the City of New York. The Center.

- Hodgetts, D., & Chamberlain, K. (2009). Teaching & learning guide for social psychology and media: Critical consideration. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(5), 842–849. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00199.x

- Hurwitz, M. (2011). The impact of legacy status on undergraduate admissions at elite colleges and universities. Economics of Education Review, 30(3), 480–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.12.002

- Husen, T. H. (1990). Education and the global concern. Pergamon Press.

- Kahlenberg, R. D. (2010). Rewarding strivers: Helping low-income students succeed in college. Century Foundation Press.

- Li, J., & Lin, J. (2008). China’s move to mass higher education: An analysis of policy making from a rational framework. In D. P. Baker & A. W. Wiseman (Eds.), The worldwide transformation of higher education: International perspectives on education and society(pp. 265–295). JAI Press.

- Li, J. (2009). Fostering citizenship in China’s move from elite to mass higher education: An analysis of students’ political socialization and civic participation. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(4), 382–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.10.001

- Li, S., Whalley, J., & Xing, C. (2014). China’s higher education expansion and unemployment of college graduates. China Economic Review, 30, 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2013.08.002

- Li, W. (2007). Family background, financial constraints and higher education attendance in China. Economics of Education Review, 26(6), 725–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.09.001

- Liu, B. (2010). An analysis on the institutional change and reform path of college entrance examination in China. Educational Research, 6, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2013.08.00a2

- Liu, H. (2006). On the nature and phenomena of college entrance examination competition. Journal of Higher Education, 12, 27–31.

- Machin, S., & Murphy, R. (2010). The social composition and future earnings of postgraduates. The Sutton Trust.

- Maiztegui Oñate, C., & Santibanez-Gruber, R. (2008). Access to education and equity in plural societies. Intercultural Education, 19(5), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980802531432

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

- Ministry of Education. (2014). Annual statistical communique′ of education. People’s Education Press.

- Nordstrum, L. E. (2006). Insisting on equity: A redistribution approach to education. International Education Journal, 7(5), 721–730.

- Nurnberga, P., Schapirob, M., & Zimmermana, D. (2012). Students choosing colleges: Understanding the matriculation decision at a highly selective private institution. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.07.005

- OECD. (2007). Ten steps to equity in education. www.oecd.org.

- Pavelka, J. (2014). The factors affecting the presentation of events and the media coverage of topics in the mass media. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.482

- Pike, G. (2007). Evaluating the rationale for affirmative action in college admissions: Direct and indirect relationships between campus diversity and gains in understanding diverse groups. Journal of College Student Development, 48(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0018

- Ross, H., & Lin, J. (2006). Social capital formation through Chinese school communities. Research in the Sociology of Education, 15, 43–69.

- Rosser, P. (1989). The sat gender gap: Identifying the causes. Center for Women Studies.

- Soroka, S. N. (2003). Media, public opinion, and foreign policy. Press/Politics, 8(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X02238783

- Spreen, C. A., & Vally, S. (2006). Education rights, education policies and inequality in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 26(4), 52–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.09.004

- Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The Rainbow project: Enhancing the SAT through assessments of analytical, practical, and creative skills. Intelligence, 34(4), 321–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.01.002

- The New York Times. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 6, 2016, from http://www.britannica.com/topic/The-New-York-Times.

- van Dijk, T. A. (1988). News as discourse. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Veronica, M., & Wilson, M. (2010). Unfair treatment: The case of Freedle, the SAT, and the standardization approach to differential item functioning. Harvard Educational Review, 80(1), 106–134. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.80.1.j94675w001329270

- Wang, L. (2011). Social exclusion and inequality in higher education in China: A capability perspective. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.08.002

- Yang, D. (2006). The ideal and reality of Chinese education equity. Peking University Press.

- Young, J. R. (2003, October 10). Researchers charge racial bias on the SAT. The Chronicle of Higher Education,40(7).

- Zhang, C., & Kong, J. (2009). An empirical study on the relationship between educational equity and the quality of economic growth in China: 1978-2004. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.035

- Zhang, Y. (2013). Does private tutoring improve students’ National College Entrance Exam performance?—A case study from Jinan, China. Economics of Education Review, 32, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.09.008

- Zhao, Y. (2006). The state, the market, and media control in China. In T. Pradip & N. Zahoram (Eds.), Who owns the media: Global trends and local resistance(pp. 179–212). Southbound Press.