Abstract

Despite the increasing recognition of positive life skills interventions to enhance the psychological and physical well=being of individuals, there is an absence of a valid and reliable Arabic measure of Life Skills (LS) amongst youth. This study aims at validating an Arabic Life Skills Scale (A-LSS) to assess the effectiveness of life skills interventions. A randomly selected sample of 1200 university students in Lebanon participated in this study. The exploratory-to-confirmatory factor analyses strategy was followed to examine the factor structure of the LSS. For that purpose, the sample was divided into two subsamples. The exploratory factor analysis results showed a nine-factor solution, with a strong reliability for the total scale (McDonald’s omega ω = 0.95) and all subscales (ω ranging from .68 to .91). The confirmatory analysis results showed excellent fit indices (CFI = .98, TLI = .97, GFI = .95; RMSEA = .031 [90% CI .028–.034] and SRMR = .061), after correlating residuals of items 53 and 54. Measurement invariance across genders was verified at the configural, scalar and metric levels. The A-LSS showed high reliability and validity of LS among Lebanese university students. This scale can be used as a valid tool to measure effectiveness of life skills health promotion interventions.

1. Background

Life Skills (LS) are considered the foundation for educational and occupational success as they expand individual’s qualities and capacities and increase the likelihood of achievement throughout life (WHO, Citation2003). LS encompass teamwork, goal setting, and time management; emotional, social, and communication skills; skills in leadership, problem solving and decision-making (Cronin & Allen, Citation2017). Life skills are the skills that make it possible for people to be involved in the design, maintenance and further development of their individual and communal life. The development of a clear concept of skills is necessary to guide research and interventions at the individual, social and cultural levels. However, it is difficult to define specific skills given the inexhaustible complexity of the world and therefore of life. Defining specific life tasks and corresponding sets of life skills that apply to all situations in all areas of human life is impossible. Life tasks may be displayed. However, you may need a systematic reductionist approach that is based on the idea of a generic set of domain-specific general human life tasks, manifesting in any concrete life task, and correspondingly, a generic set of general human life skills (Bertelsen, Citation2021).

General life skills produce specific action directions that are needed in specific situations. For example, common relational skills can evoke a variety of relational actions that meet the needs of a particular situation, such as family, friends, or school. Overall, this points to an elaboration of the concept of goal-directed and solution-focused prospection, or an elaboration of prospection based on the notion of personally lived and coexistent ally organized life projects realized by sets of life task/life skill units (Bertelsen, Citation2021). Therefore, we will be focusing on specific life skills domains that proved, if integrated in life skills interventions, to enhance the health outcomes of the population.

LS interventions focusing on time and house management, self-care, communication skills, goal settings, and career guidance proved to enhance the psychological and physical well-being, and development of an individual, especially among university students (Cronin et al., Citation2018). Interventions targeting LS have shown effectiveness in avoiding negative health behaviors, related to mental ill-health (Spaeth et al., Citation2010; Fox et al., Citation2011) and physical health (Ferland et al., Citation2014; Steptoe & Wardle, Citation2017). It is therefore essential that health promotion interventions aiming to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors enhance LS and coping mechanisms among Lebanese university students who are suffering from multiple crisis; financial, political, and health which affect both their mental and physical health outcomes (Kebede et al., Citation2020). However, this type of health promotion LS programs are rarely implemented. In Lebanon, the population is facing dire economic state; high levels of unemployment; protracted political instability; and demographic change as a function of the influx of Palestinian and Syrian refugees, exposing them to adverse health outcomes (UNDP, Citation2020). Therefore, the need for LS scales and LS interventions, in such context, is crucial.

Life Skills can be acquired and enhanced with the aim of bringing success in all spheres of life and for leading quality and productive life. Life Skills can be observed and assessed through specific measures. A visible change in behavior could be overtly seen through life skills enhancement training (Subasree & Radhakrishnan Nair, Citation2014).

Despite the need for identification of LS that affect youth behaviors, no valid LS measurement scale exists in Arabic. Furthermore, globally there is a limitation in the development of valid LS scales for university students. There is one life skills scale designed by Shimamoto and Ishii (Citation2006) in Japan, which was classified into two general skills: skills used mainly in personal situations (planning, knowledge summarization, self-esteem, and positive thinking), and skills used generally in interpersonal situations (intimacy, leadership, empathy, and interpersonal manner) with subscale and total scale scores found to be moderately reliable and valid. However, none of the skills addressed health behaviors. Other LS scales were limited to assess LS among children (Babadi & Meshkani, Citation2011; Luckey & Nadelson, Citation2011) or high school students (Erawan, Citation2010). While Erawan’s scale was found to be highly reliable and valid, the scale was designed to assess LS among teenagers only (Erawan, Citation2010). Another 112-item scale was developed by Casey Family Programs, called the Casey Life Skills Assessment (CLSA), targeting youth 14 years and older (Casey Family Programs, Citation2012). The scale consisted of seven domains that were identified based on competencies needed for youth to achieve long-term goals related to maintaining healthy relationships, work and study habits, planning and goal-setting, using community resources, daily living activities, budgeting and paying bills, computer literacy, and youth permanent connections to caring adults. According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, Citation2013), 47 LS tools were used to assess youth development and LS worldwide; limited reliability and validity was demonstrated among these tools when tested in Arab countries. Therefore, a valid and reliable Arabic LS assessment tool is required to assess the gaps in knowledge regarding LS among Lebanese university students and to facilitate tailored LS programming and interventions.

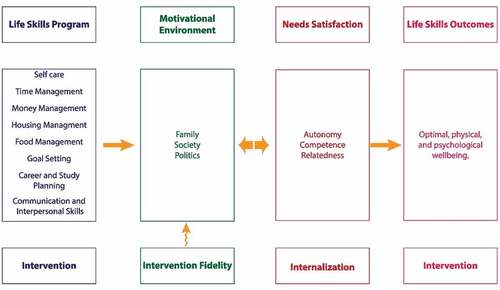

1.1 Conceptual framework adopted

In health promotion, we are always concerned with personal-health, health-related, and protective-health behaviors, therefore, we will infuse the comprehensive model synthesized by Hodge et al. (Citation2013) into the ecological framework by adding constructs from a motivational theory; Basic Needs Theory (BNT). BNT is mini-theory of self-determination (Ryan and Deci 2000a). It suggests that human function and development are a result of the interaction between the distal factors of the ecological model and humans’ psychological needs (proximal factors), which are summarized in three basic constructs; autonomy (individuals perceive themselves as origin of their own decisions and sense of self), competence (ability of individuals to excel in their lives), and relatedness (feeling of security being a part of a social network). Satisfaction of these psychological needs is assumed to directly enhance psychological and physical well-being (Deci and Ryan Citation2000). Therefore, the suggested scale is not only a scale to measure individuals’ beliefs but to study the combination of individuals’ performance and the influence of the distal factors on the students’ autonomy, competencies, and relatedness to adopt certain behavior. Our suggested CLSA scale is designed to be aligned with theory-based life skills interventions. Without the development of a conceptual framework, it is difficult to determine whether individual life skills interventions achieve optimal psychological and physical well-being. By developing this conceptual framework, we seek not only to identify the proximal and distal factors that influence university students’ behaviors but to identify and articulate the key underlying psychological mechanisms (i.e., basic needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness) that contribute to optimal human functioning and better ability to take wise and informed decisions that lead to positive psychosocial and physical development. The CLSA, although was not tested for reliability and validity, it was used in several countries and with different age groups, targeting different levels of the ecological model; individuals knowledge and practices, in addition to how individuals are interacting with their families, communities, and policies (Casey Family Planning, 2012), making it the optimal scale to adopt in our current study especially that its domains are formed of constructs that are aligned with the main components of health promotion life skills-based interventions (Figure ).

Our study aims to validate an Arabic LS Scale (A-LSS) developed through the adaptation of the Casey LS scale to integrate cultural considerations of Lebanese young adults facing multiple crises. This scale will then be used to measure the effectiveness of LS-based interventions designed to help youth become mentally and physically healthier in Lebanon and in similar Arab populations.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the concerned universities. An informed-consent form was attached to the first page of both hard and soft copies of the survey. It states clearly that the participation of the students is totally voluntary and their decision in pursuing or stopping or even withdrawing from the study will not affect their relation with their university in anyway. Information on potential harms and benefits of the study and the contact information of all the researchers are indicated in the consent form.

2.2. Participants

A total of 1200 university students representing the target population have participated in the study. Seven universities have agreed to participate in this study. Recruitment efforts targeted a sample with a region and sex distribution proportional to that of the total number of students enrolled in each university. The student affairs office and university registrars randomly sent the link of the survey to 500 students from their student database (computer-based selection). The Arabic version of the questionnaire was administered. The response rate was 34.28%. . The participants are 32% males and 68% females and their mean age is 21.1 years (SD 8.7).

2.3. Instruments

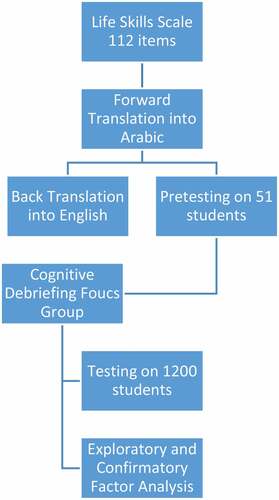

The A-LSS used in this study was adapted from the original English version of Casey Life Skills Assessment (CLSA), (Casey Family Programs, Citation2012) which is formed of 112 items measuring seven dimensions of life skills; Daily Living (17 items), Self-Care (17 items), Relationships and Communication Skills (18 items), Food and House management (23 items), Work and Study Life (20 items), Career and Education Planning (9 items), Goal Setting/Looking Forward (8 items). WHO guidelines were followed for cross-cultural adaptation of the scale, using a forward translation of the questionnaire, followed by a back translation (WHO, Citation2015). Pre-testing and cognitive interviewing which serves to identify potentially problematic questions, ambiguities and difficulties which could lead to unintended answers among respondents, were conducted before a final testing of the questionnaire took place (WHO, Citation2015). The steps followed for the validation process are shown in Figure . The full version of the Arabic validated scale is attached as an appendix.

2.4. Forward translation to Arabic

The English version of the Casey LSS was forward translated to Arabic by a single bilingual translator who is familiar with the concepts included in the questionnaire. The translator’s mother-tongue is Arabic, and is fluent in English. The translated questionnaire was then reviewed by an expert panel to verify the idioms and structure of the translated version. The expert panel consisted of the original translator, healthcare professionals an expert in LS and a member of the Institutional Review Board (Antunes et al., Citation2012).

2.5. Back-translation into English

The Arabic version of the LSS was then back-translated into the English language by a native English speaker translator, who is fluent in Arabic and has no prior knowledge of the questionnaire (WHO, Citation2015). The back-translated English questionnaire was compared to the original English one, by the expert panel, where any discrepancy between the two versions was discussed. As in the initial translation, emphasis in the back-translation was on conceptual and cultural equivalence, and not linguistic equivalence (WHO, Citation2015).

2.6. Pre-testing

The pre-final (after the back translation stage) A-LSS was then tested on a sample (status and sex distribution proportional to that of the total number of students at university level excluding any student who doesn’t speak both Arabic and English languages) composed of 51 students who completed the survey in Arabic language. According to Perneger et al. (Citation2015), the sample size for pre-test phase in scale validation requires 30–50 participants. Then, as part of the cognitive debriefing, four focus groups were conducted with a group of students who completed the survey in both languages (six to seven students from different universities, backgrounds, and university years have participated in each focus group). These students were selected based on their acceptance to be contacted for the validation phase (A statement was added to the survey asking for a voluntary participation in the focus group discussions). The interview guide developed included questions about students’ understanding of the questionnaire in the same way as the original would be understood” and asking them to restate the meaning of each translated question. Participants were also questioned about the presence of any unclear or offending expressions, culturally unacceptable questions as well as the time needed for a student to complete the survey.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The final version of the LS Survey was tested on a larger sample of 1200 participants (an approximate of 10 participants per item (Antunes et al., Citation2012). We followed the strategy described by Swami and Barron (Citation2019) to examine the factor structure of the LSS, consisting of an EFA-to-CFA strategy. We split the main sample using the SPSS computer-generated random technique; the description of the two samples is shown in Table . There were no significant differences between the two subsamples in terms of mean age (t(1193) = .842, p = .400), and BMI (t(1198) = .264, p = .792), as well as the distribution of women and men (χ2(1) = .163, p = .687) and governorates (χ2(5) = 4.248, p = .514).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

2.8. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

To explore the factor structure of LSS, we computed a principal component analysis EFA on the first subsample using the SPSS software v.22. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (which should ideally be ≥ .80) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (which should be significant) ensured the adequacy of our sample (Hair et al., Citation2010). Item retention was based on the recommendation that items with “fair” loadings and above (i.e., ≥ .40) and high communality (>0.3) will be retained.

2.9. Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory analysis was conducted on the second subsample to test the factorial structure of the LSS obtained in the EFA. We used weighted least squares with mean and variance (WLSMV) estimation method, which is more appropriate for ordinal data. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in RStudio (Version 1.4.1103 for Macintosh), using the Lavaan and semTools packages. Values greater than .90 and .95 for the CFI and TLI, values closer to 1.00 for the GFI indicate a better model fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Mulaik et al., Citation1989). However, values for the RMSEA at or below .08 are expected to represent a good model fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Mulaik et al., Citation1989).

To examine gender invariance of the LSS scores, we conducted multi-group CFA (Chen, Citation2007). Measurement invariance was assessed at the configural, metric, and scalar levels (Vandenberg & Lance, Citation2000). Following the recommendations of Cheung and Rensvold (Citation2002) and Chen (Citation2007), we accepted ΔCFI ≤ .010 and ΔRMSEA ≤ .015 or ΔSRMR ≤ .010 (.030 for factorial invariance) as evidence of invariance.

Missing data constituted less than 5%, thus, was not replaced. To assess reliability, McDonald’s omega values were computed for each factor and the total scale. Values ≥.70 were considered acceptable (Dunn et al., Citation2014). Finally, we examined the skewness and kurtosis values for the temperament subscales scores, which were within defined range (skewness and kurtosis between −1 and +1; (Hair, Citation2010)). Therefore, the sample was considered normally distributed. Consequently, Pearson correlation test was used to test the convergent and divergent validity of the scales. The latter analysis was done using SPSS software v.22.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

The cognitive debriefing conducted by the researchers, who were well trained to facilitate focus groups, showed that students had a clear understanding of the questions as well as a minimal ambiguity related to the culture difference in each context. The following are examples of questions that research team has edited to for suitability to the culture-context.

Factor analysis was conducted and showed a high Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (0.917), with a significant Bartlett’s test of Sphericity (χ2 = 23,186.65; df = 1830; p < 0.001). Anti-image correlations were all adequate. The total variance explained was 55.86% spread on nine factors with variance ranging from 24.77% for factor 1 to 2.24% for factor 9. Items that did not load were removed. A total of 61 items remained in the final analysis, which were distributed as follows: (Factor 1: Money and Housing Management; Factor 2: Goal Setting; Factor 3: Time Management and Planning Skills; Factor 4: Relationship and Communications; Factor 5: Sexual and Social Protection; Factor 6: Work Life; Factor 7: Job Preparation; Factor 8: Seeking Advice and Factor 9: Career and Education Planning; Table ). Moreover, the McDonald’s omega showed a strong reliability for the total scale (ω = 0.95) and all subscales (ω ranging from .68 to .91).

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of the LSS scale items using the promax rotation on the first subsample

3.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

We conducted a CFA on subsample 2 using the nine-factor solution obtained in the EFA on subsample 1; the fit indices were excellent as follows: CFI = .97, TLI = .96, GFI = .97; RMSEA = .065 [90% CI .063–.067] and RMR = .074.

To improve this original model, we examined the modification index (MI) as recommended (Bryant et al., Citation1999). More specifically, the MI provide an estimate increase in the chi-square for each parameter if it were to be freed (Perry et al., Citation2015). In the current study, the MI outlined a strong positive covariance (i.e., of .90) between items 53 and 54. Accordingly, a modified model considering this covariance was created; the fit indices improved more as follows: CFI = .98, TLI = .97, GFI = .95; RMSEA = .031 [90% CI .028–.034] and SRMR = .061.

The standardized loading factors, standard errors and p-values are summarized in Table .

Table 3. The standardized loading factors, standard errors and p-values

3.3. Measurement invariance between males and females

We tested for gender invariance of the nine-factor structure of the LSS scale. All indices suggested that configural, metric, and scalar invariance were supported across gender (Table ).

Table 4. Measurement invariance across gender in the second subsample

4. Discussion

This study is the first to validate a life skills scale in Arabic. The cross-cultural adaptation recommended by WHO was adopted by including a forward- and back-translation of Casey LSS. The use of an exploratory and confirmatory approach to study the dimensionality of the measure delivered a structure composed of nine dimensions whose psychometric properties were optimal in terms of internal consistency and reliability. The development and validation of a short scale like the one presented in this paper has increased in the last decade (e.g., Blanca et al., Citation2020; Postigo et al., Citation2020) due to the benefits of reducing application time for both research and practice, something that is also offered by A-LSS.

The dimensions of A-LSS ((1) Financial and housing management, (2) Goal settings, (3) Time Management and Planning Skills, (4) Relationships and communications, (5) Sexual and social protection, (6) Work life, (7) Job preparation, (8) Seeking advice, (9) Career and education planning) cluster items that are usually included within health promotion interventions addressing life skills.

The validated A-LSS addressed the different constructs of the socio-ecological model and basic needs theory where its factor loadings are reflecting not only the proximal skills needed for individuals (e.g., time, money, and house management) to enhance their well-being but also other skills related to the interaction with families, friends, and communities (e.g., seeking advice, relationships and communications); this entails individuals’ autonomy, competence and relatedness and their interaction with their environment. These are crucial in designing life skills interventions. The results are very similar to a study conducted by García Alba et al. (Citation2021) where they found that the life skills are featuring three main pillars: (1) taking care of oneself and one’s home, (2) operating in the community as a citizen and (3) living and being financially independent. This could represent the process of transitioning into adulthood, which implies the progressive acquisition of new roles and responsibilities towards oneself and the others and culminates with preparing and finding a job, being able to sustain mature relationships and establishing their own home and financial plans. These dimensions could constitute a simple but significant framework to lead autonomy-development in youth, as young people can benefit from the early gradual development of areas related to personal every-day autonomy at home and in the community, whereas those related to emancipating—getting a job, finding a place of their own to live, etc.—should be addressed later on and supported through life skills programs (Harder et al., 2020).

Based on Johnston et al. (Citation2013) review of 34 life skills papers, life skills are also related to workplace, productivity, accomplishments (Rubin & Morreale, Citation1996), academic performance (Britton & Tesser, Citation1991; Humphrey, Citation2011) overall health (Claessens et al., Citation2007), and psychological well=being (Brackett & Mayer, Citation2003; Judge et al., Citation2005). This can explain the presence of factors, in this study, related to work, education, and health such as money and house management, sexual and social protection, and seeking advice regarding health and financial issues. These factors are not included in other LSS developed by Erawan (Citation2010) and Cronin and Allen (Citation2017), but similar to the scale developed by Subasree and Radhakrishnan Nair (Citation2014) consisting of nine domains mentioned in our study. As there is an absence of life skills scale targeting young adults, the results of this study were compared with the scale developed by Erawan (Citation2010), where the factor analyses of the final 120-item measure yielded to only three factors (Knowledge, Attitude, and Skills). The reliability of Erawan study was 0.92 for the overall scale, which is similar to our study that showed a McDonald’s omega 0.95. Contrary to the scales evaluated by USAID (Citation2013) used in the Arabic language such as Passport to Success Scale, this scale showed a high level of validity and reliability. The process of adaptation of the scale to the social and cultural context in addition to it being valid and reliable, the A-LSS can be used to assess life skills among youth as well as to measure the effectiveness of life skills-based health promotion interventions that aim to enhance the overall well=being of university students.

4.1. Limitations

Although our study covers the required sample size to validate a scale, with subjects from various Lebanese regions, public and private sectors, and different academic backgrounds and classes, the study would benefit from additional evaluation of the questions across various age groups and among other Arab nationalities in the future. Additional research is also needed to assess other properties, e.g., convergent and divergent validities, test–retest, etc. in addition to the initial psychometric properties assessed in this paper. One other limitation faced was related to the data collection phase where a large number of surveys were incomplete and many students complained about the length of the survey that took around 35 minutes to be filled; the validated scale, however, is shorter than the original one and can be easily filled in less than 10 minutes. Despite all the limitations stated, this study was the first in the Arab region to validate a LS scale that shows a high level of reliability and validity as well as high test–retest reliability.

4.2. Conclusion

This study shows that the Arabic LS scale can be used in the Lebanese context to assess life skills among young adults. It has an acceptable reliability and validity of the LS among the Lebanese university students to be used for LS intervention assessments and evaluations.

Abbreviations

Life Skills: LS

Arabic Life Skills Scale: A-LSS

Life Skills Scale: LSS

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The ethical approval was taken by all the participated universities and the consent forms were taken from all the participants. Ethical approval reference numbers:

American University of |Beirut: SBS- 2019-0081

Lebanese American University: LAU-SOP-WK1.16 April 2019Modern University for Business and Science: MU-20190307-15

Other participated universities: used same ref as American University of |Beirut

Authors’ contributions

DM: Data collection, analysis, and writing

SH: analysis, writing and editing

WK, MA: Data collection and editing of the manuscript

KB and NHA: Writing and editing.

ZH: Writing and editing

TKK: IRB approvals and Writing

PS: Supervising, proof reading and analysis

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the universities that participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Antunes, B., Daveson, B., Ramsenthaler, C., Benalia, H., & Ferreira, P. L. (2012). The palliative care outcome scale (POS) manual for cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation. https://pos-pal.org/doct/Manual_for_crosscultural_adaptation_and_psychometric_validation_of_the_POS.pdf

- Babadi, A., & Meshkani, M. (2011). Life skill scale: Reliability instrument to measure life skills in elementary schools. https://www.sid.ir/paper/188615/en

- Bertelsen, P. (2021). A taxonomical model of general human and generic life skills. Theory & Psychology, 31(1), 106–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354320953216

- Blanca, M. J., Escobar, M., Lima, J. F., Byrne, D., & Alarcon, R. (2020). Psychometric properties of a short form of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ-14). Psicothema, 32(2), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.28

- Brackett, M. A., & Mayer, J. D. (2003). Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(9), 1147–1158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254596

- Britton, B. K., & Tesser, A. (1991). Effects of time-management practices on college grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 405e410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.3.405

- Bryant, F. B., Yarnold, P. R., & Michelson, E. A. (1999). Statistical methodology. Academic Emergency Medicine, 6(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00096

- Casey Family Programs. (2012). Casey life skills practice guide.

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Claessens, B. J., van Eerde, W., Rutte, C. G., & Roe, R. A. (2007). A review of time management literature.Personnel Review. 36(2), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480710726136

- Cronin, L. D., & Allen, J. (2017). Development and initial validation of the life skills scale for sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 28, 105–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.001

- Cronin, L. D., Allen, J., Mulvenna, C., & Russell, P. (2018). An investigation of the relationships between the teaching climate, students’ perceived life skills development and well-being within physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1371684

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The' what' and' why' of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

- Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

- Erawan, P. (2010). Developing life skills scale for high school students through mixed methods research. European Journal of Scientific Research, 47(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/e567102014-001

- Ferland, A., Chu, Y. L., Gleddie, D., Storey, K., & Veugelers, P. (2014). Leadership skills are associated with health behaviours among Canadian children. Health Promotion International, 30(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau095

- Fox, P., Caraher, M., & Baker, H. (2011). Promoting student mental health. Ment. Health Found, 2(1), Available from. http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/?entryid5=39405andq=684278%c2%acStudent+Mental+Health%c2%ac

- García Alba, L., Postigo Gutiérrez, Á., Gullo, F., Muñiz, J., & Fernández Del Valle, J. C. (2021). PLANEA independent life skills scale: Development and validation. Psicothema, 33(2), 268–278. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2020.450

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hodge, K., Danish, S., & Martin, J. (2013). Developing a conceptual framework for life skills interventions. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(8), 1125–1152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012462073

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. structural equation modeling. A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118Humphrey

- Humphrey, N., Kalambouka, A., Wigelsworth, M., Lendrum, A., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2011). Measures of social and emotional skills for children and young people: A systematic review. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 71(4), 617e637. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410382896

- Johnston, J., Harwood, C., & Minniti, A. M. (2013). Positive youth development in swimming: Clarification and consensus of key psychosocial assets. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 25(4), 392–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2012.747571

- Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. A. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 257–268. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.257

- Kebede, T. A., Stave, S. E., & ILO, M. K. (2020). Facing Multiple Crises: Rapid assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable workers and small-scale enterprises in Lebanon.

- King, P. E., Schultz, W., Mueller, R. A., Dowling, E. M., Osborn, P., Dickerson, E. (2005). Positive youth development: Is there a nomological network of concepts used in the adolescent development literature? Applied Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0904_4

- Luckey, K. L., & Nadelson, L. S. (2011). Developing a life skills evaluation tool for assessing children ages 9-12. Journal of Youth Development, 6(1), 108–130. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2011.202

- Mulaik, S., James, L., Alstine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.430

- Perneger, T. V., Courvoisier, D. S., Hudelson, P. M., & Gayet-Ageron, A. (2015). Sample size for pre-tests of questionnaires. Quality of Life Research, 24(1), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0752-2

- Perry, J. L., Nicholls, A. R., Clough, P. J., & Crust, L. (2015). Assessing model fit: caveats and recommendations for confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation modeling. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 19(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2014.952370

- Postigo, Á., García-Cueto, E., Cuesta, M., Menéndez-Aller, Á., Prieto-Díez, F., & Lozano, L. M. (2020). Psicothema. In T. B. Romero, M. Melendro, & C. Charry (Eds.), Assessment of the enterprising personality: A short form of the BEPE battery. Vol. 4 (32), 575–582. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2020.193

- Rubin, R. B., & Morreale, S. P. (1996). Setting expectations for speech communication and listening E. A. JonesEd. Preparing competent college graduates: Setting new and higher expectations for student learning New directions for higher educationVol. 96, 19e29.Jossey-Bass

- Shimamoto, K., & Ishii, M. (2006). Development of a daily life skills scale for college students. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.5926/jjep1953.54.2_211

- Spaeth, M., Weichold, K., Silbereisen, R. K., & Wiesner, M. (2010). Examining the differential effectiveness of a life skills program (IPSY) on alcohol use trajectories in early adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 334–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019550

- Steptoe, A., & Wardle, J. (2017). Life skills, wealth, health, and wellbeing in later life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(17), 4354–4359. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1616011114

- Subasree, R., & Radhakrishnan Nair, A. (2014). The life skills assessment scale: The construction and validation of a new comprehensive scale for measuring life skills. OSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 19(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-19195058

- Swami, V., & Barron, D. (2019). Translation and validation of body image instruments: Challenges, good practice guidelines, and reporting recommendations for test adaptation. Body Image, 31, 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.014

- UNDP. (2020). Poverty, growth and income distribution in Lebanon. https://www.undp.org/arab-states/publications/poverty-growth-and-income-distribution-lebanon

- USAID. (2013). Scan and review of youth development measurement tool Life Skills.

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002

- World Health Organization. (2003). Skills for health: skills-based health education including life skills: An important component of a child-friendly/health-promoting school. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2015). Management of substance abuse - process of translation and adaptation of instruments. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/