Abstract

Academic integrity has become one of the most discussed issues in higher education over the past decade. When writing research outputs, students increasingly search for easy fixes. The awareness and perception of plagiarism among postgraduate students and probable socio-demographic factors such as gender, age, and academic level disparities were discussed. This study focuses on a sample of 1054 postgraduate students in a developing country. The collected data were analysed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions, and the proposed hypothesis was tested using a Structural Equation Modeling approach. The findings showed a statistically significant difference between postgraduate students’ academic level and their awareness of plagiarism. However, neither the postgraduate students’ gender nor on academic level significantly affected the perceived reasons for engaging in plagiarism. Implications for academic managers, librarians, lecturers, postgraduate students, and researchers are also provided.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Academic integrity has become one of the most discussed issues in higher education. This has been attributed to the growing instances of academically dishonest conduct among students. When writing research outputs, students are increasingly searching for easy fixes. This situation raises concerns because our academic discourse appears to be losing touch with ethical values. This study set out to determine how students felt about plagiarism, whether they were aware of it, and whether variables such as gender, age, and academic level impacted their reasons for plagiarism. The University of Cape Coast was chosen because it is the topmost-ranked University in Ghana and West Africa and it is among the top five Universities in Africa. Students must receive instruction on plagiarism to comprehend and value the idea. The teaching of the principles of academic writing must be provided to students.

1. Introduction

Academic integrity has become one of the most discussed issues in higher education over the past decade. This has primarily been attributed to the growing instances of academically dishonest conduct among graduate and undergraduate students (Amzalag et al., Citation2022; Nasir et al., Citation2011). A phenomenon that has been attributed to poor writing skills and lack of feedback from lecturers on writing assignments as well as the increasing rise in internet access and the advent of artificial intelligence-based educational tools such as ChatGPT, GetGenie, QuillBot, Spinbot, etc (Abbas et al., Citation2021; Chaudhry et al., Citation2023). Academic misconduct is generally defined as any action that unfairly violates the rules of research or education, resulting from dishonest behaviour, unfair practice, irregularity, cheating, and plagiarism (Amzalag et al., Citation2022). Similarly, Siaputra and Santosa (Citation2015) identified five types of academic misconduct: fabrication, falsification, cheating, sabotage and professorial misconduct. According to Löfström (Citation2015), the most severe forms of academic misconduct were related behaviours, such as taking an exam for another student, duplicating or purchasing papers, and using cheat sheets. These are undoubtedly academic misconduct that could provide the culprit with an unfair advantage over people who act honourably.

A survey by Curry and Rainey (Citation2007) examined the instances of cheating among American university students, and 75% admitted cheating at least once during their academic career. In addition, a study by Morgan (Citation2016) reported that 50,000 university students confessed to having been involved in academically dishonest conduct. A similar study by Taylor et al. (Citation2002) on the realities of academic dishonesty in Australia and New Zealand revealed that 14 higher education institutions recorded 342 cases within a single academic year. A study conducted in two Nigerian institutions showed that 54.2 % of undergraduate pharmacy students had been involved in some form of academic dishonesty in their academic endeavors (Ubaka et al., Citation2013). In Ghana, the literature pegs the prevalence rate of academic dishonesty among tertiary students between 4.7% to 62.4% (Mensah et al., Citation2018; Saana et al., Citation2016).

Plagiarism is one of the most commonly discussed aspects of academic integrity (Mwamwenda, Citation2006). The Ministry of National Education Regulation (MNER), (Citation2010) defines plagiarism as the deliberate or accidental attempt to obtain credit or value for a scientific paper by citing some or all of the work and/or scientific work of any other person and publishing it under his/her own name without citing the original source. It can be deduced that a person or group of individuals who engage in plagiarism, each working independently, on behalf of a group, or on behalf of an agency, is referred to as a plagiarist. Usually, it refers to using other works, ideas, or words without credit. Forms of academic integrity breaches such as plagiarism call for students and staff education. Therefore, users need to be aware and have knowledge on plagiarism to have academic integrity.

On the other hand, Reinhardt et al. defined awareness as knowledge of the history of something, an occasion, or a phenomenon. In addition to knowledge of an item or event, awareness can be related to skills, abilities, and operational methods. Awareness and perception impact a person’s judgment and behavior (Alimorad, Citation2018). Alasmar (Citation2019) posited that perception is the process of identifying, organizing, and interpreting sensory information. In this study, awareness refers to postgraduate students’ knowledge of plagiarism, while perception denotes postgraduate students’ views of what constitutes plagiarism.

Students who claim that other people’s work is their own are simply cheating; however, this is not just an academic issue; it is also ethical, and the resultant academic work is unethical if intellectual property rights are infringed. Whether deliberate or inadvertent, the increasing incidence of plagiarism raises serious concerns about academic integrity, student learning, and the legitimacy of higher education degrees conferred on plagiarists (Amponsah et al., Citation2021). However, it must be noted that academic dishonesty is not only an educational problem but also a societal or professional problem, as students who are involved in academically dishonest conduct have the strongest tendency to conduct themselves in an unethical or dishonest manner in the workplace (Mulisa & Ebessa, Citation2021; Nasir et al., Citation2011; Rakovski & Elliott, Citation2007). Therefore, members of the academic community are expected to uphold the principles of fairness, honesty, respect, trust, and responsibility (Amzalag et al., Citation2022; Mwamwenda, Citation2006). In turn, Eaton (Citation2023) indicated that academic integrity address issues of equity, diversity and inclusion.

Although there has been some empirical research on plagiarism, most of these studies appear to be highly informed by developed-country experiences (Nova & Utami, Citation2018; Tran et al., Citation2022; Tremayne & Curtis, Citation2021; Wang & Zhang, Citation2022). This made it impossible to perform cross-country comparisons of the results. There has not been any rigorous analysis of students’ attitudes, experiences, knowledge, or perspectives about copied content at Ghanaian University. Furthermore, without a deeper understanding of plagiarism’s meaning to Ghanaian students, effective educational measures to promote academic integrity cannot be developed. This study, the first of its type in Ghana, set out to determine how students felt about plagiarism, whether they were aware of it, and whether variables such as gender, age, and academic standing had an impact on their reasons for engaging in plagiarism. It is crucial to examine awareness and perception, and how they relate to demographic characteristics, since doing so may help to determine the most suitable ways to deal with this phenomenon.

1.1. Relevant literature and hypotheses development

Plagiarism is predominant at all levels of education (Du, Citation2020; Newton, Citation2016; Tremayne & Curtis, Citation2021) and is influenced by students’ awareness and perception of it. There is some amount of literature on socio-demographic differences in the perceptions and awareness of plagiarism among undergraduate students (Fatima et al., Citation2019; Issrani et al., Citation2021; Jereb et al., Citation2018; Newton, Citation2016; Tremayne & Curtis, Citation2021). Tran et al. (Citation2022) investigated to understand better how postgraduate Vietnamese and New Zealand university students perceive plagiarism. They discovered significant distinctions between the two groups’ perceptions and plagiarism practices. Prior experience, culture, age, gender, academic level, and field of study impacted students’ perceptions.

Similarly, Nova and Utami (Citation2018) examined student perceptions of plagiarism using plagiarism-detection software. Using a qualitative method, novice students were asked to give their thoughts on the originality report of their coursework after submitting them to check for plagiarism. From the analysis of the responses, the researchers deduced that the students who complained about the software had limited knowledge about plagiarism and awareness of the software; however, interestingly, some of the students were able to predict the outcome of the originality report of their coursework from the use of the software, which was in line with the results of the software. From these results, they deduced that the students were aware of plagiarism and its constituents.

Newton (Citation2016) studied whether students can detect plagiarism in terms of having a full understanding of the consequences and being confident about their knowledge of plagiarism. Undergraduate and postgraduate students were assessed in real-life situations using interactive research instruments. After analysing their data, the researchers found that postgraduate students were more aware of plagiarism and recommended more severe punishment than undergraduate students. A study by Iyer and Eastman (Citation2006) indicated differences in the tendency to engage in plagiarism based on student academic discipline and gender. Using a sample size of 353 participants, their results showed that men were more likely to engage in plagiarism than women. However, they found no significant differences between academic level and plagiarism.

Similarly, Tremayne and Curtis (Citation2021) investigated how socio-demographic factors, awareness, and perceptions affect plagiarism. Their study found that women are less likely to plagiarise and are more aware of plagiarism. Jereb et al. (Citation2018) also explored gender differences and the awareness of plagiarism. Using a survey method and a sample size of 139, they found that men have little or no education about plagiarism, whereas women have a greater understanding of plagiarism; hence, they are less likely to engage in plagiarism. Bateman and Valentine (Citation2010) suggested that women are more conscious of the consequences of unethical behaviour and therefore adhere to ethical rules, so they are not likely to engage in unethical behaviour.

In contrast, Thompsett and Ahluwalia (Citation2010) found no significant gender differences in terms of awareness and tendency to engage in plagiarism. Still, their findings are limited due to the sample size used in the study. Overall, their research findings showed that most of the study participants had some knowledge about plagiarism but needed more understanding due to the training recommendation the participants requested when answering the research questionnaire.

Becker and Ulstad (Citation2007) suggested that including ethical courses as part of academic disciplines reduces unethical behaviours. They emphasised that through these courses, students are exposed to the penalties and rules associated with unethical behaviour. Their findings show that students may engage in unethical behavior but may not be able to identify whether those behaviours equate to academic misconduct. Furthermore, their study confirmed that gender differs in unethical behaviour, with women being more ethical than men. These studies have examined one or two demographic factors compared to this research, which explored the gender, age, and academic level of students simultaneously. In addition, the existing literature on the subject matter appears to be highly informed by developed-country experiences. This made it impossible to perform cross-country comparisons of the results. Therefore, the researchers wanted to examine postgraduate students’ socio-demographic variables (gender, age, academic level) on the perception and awareness of plagiarism to fill this research gap from a developing country perspective.

1.2. Hypotheses

This study aimed to examine the socio-demographic variables (gender, age, academic level) of postgraduate students’ perceptions and awareness of plagiarism. In line with this study’s objective, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H1:

There is no statistically significant relationship between perceptions of plagiarism among men and women.

H2:

There is no statistically significant difference between the age of postgraduate students and their awareness of plagiarism.

H3:

There is no statistically significant relationship between postgraduate students’ ages and their perceptions of plagiarism.

H4:

There is no statistically significant difference between students’ academic levels and their perception of plagiarism.

H5:

There is no statistically significant difference between students’ academic level and their awareness of plagiarism.

H6:

There is no statistically significant difference in the gender of postgraduate students or their awareness of plagiarism.

2. Methods

2.1. Context

The University of Cape Coast (UCC) was chosen because it is the topmost-ranked University in Ghana and West Africa and is among the top five Universities in Africa. Globally, the UCC is 24th regarding research influence and is among the top 400 universities (Times Higher Education World University Rankings, Citation2023). The university has a plagiarism policy to which all postgraduate students must strictly adhere. All postgraduate students must register for a Turnitin account (antiplagiarism detection software) and utilize it in their academic pursuits throughout their stay on campus. The participants of this study were postgraduate students from the UCC.

2.2. Study design

A cross-sectional survey research design was adopted for this study because of its ability to produce quantitative descriptions of large populations by examining their representative sample (Siedlecki, Citation2020).

2.3. Research instrument

A structured questionnaire via Google Forms was developed to gather data in September-November 2022. The questionnaire items were constructed in English. This was because the targeted respondents had a firm grasp of grammar structures of the English language and could be classified as proficient English users according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. The questionnaire consisted of three sections. Section 1 collected data on participants’ demographics. Section 2 solicited respondents’ perceptions of plagiarism, while Section 3 focused on respondents’ awareness of plagiarism. The respondents’ identifiable information were not recorded. The research instrument was pretested on 30 postgraduates students who participated in annual electronic resources training for postgraduate students. To minimise data contamination, the students used in the pre-test were excluded from the actual study.

2.4. Population and sampling

A total of 2609 postgraduate students of the UCC were included in the study. However, of 1054 responded to the questionnaire. A multilevel sampling approach was used to provide a proportional representation of university participants. First, the institutions were divided into colleges using a stratified sampling approach. Purposive sampling was used in each college to identify postgraduate students in various fields. Respondents were recruited through social media announcements made on WhatsApp. Students who showed interest in the topic by responding to social media announcements voluntarily responded to an online survey.

2.5. Variables

The demographic information collected included sex, age, academic level, and college affiliation. The questionnaire consists of 24 Likert-scale questions. Seven questions were on awareness of Turnitin, nine on the perception of plagiarism, and eight on Turnitin. Respondents had to indicate their agreement or disagreement with the statements on a scale of 1 to 5 (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Some Turnitin awareness questions are “I am aware that the University of Cape Coast has a plagiarism policy” and “I am aware that the University of Cape Coast has a plagiarism detection software called Turnitin.” Regarding the perception of plagiarism, the students were asked “paying for a paper to be written for you is a form of plagiarism” and “copying text from a book, article, or web page and submitting it as yours without indicating the source is a form of plagiarism”.

2.6. Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and voluntary participation was ensured. The survey responses were anonymous, and we did not collect identifiable information about the participants.

2.7. Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21.0. A regression analysis of the latent variables was performed to explore the relationships between various research variables. The Partial Least Square (PLS) algorithm was used for the regression analysis.

3. Results

Of the total population of 1054, 98.5% of the respondents indicated that they were aware that the UCC has a plagiarism detection software called Turnitin. Additionally, it was determined that the majority of participants were males (62.4%). It was also discovered that the majority of the postgraduate students were in the college of education studies discipline. College as used in the current study refers to the respondents’ field of study. Similarly, most postgraduate students pursue MPhil/MCom degrees. The results are presented in Table .

Table 1. Demographic statistics of the respondents

The results were examined using the SEM approach once data were collected. A regression analysis of the latent variables was initially performed to investigate the links between various study variables. Regression analysis was performed using the partial least square (PLS) technique. The PLS is a regression technique that selects components that increase predictive performance and delivers more stable coefficient values, resulting in improved overall predictive performance and more stable coefficient values (Ozogul et al., Citation2013). Sarstedt et al. (Citation2019) state that PLS enables simultaneous model measurement and structural optimization.

For the reliability and validity of the study, all loaded indicators were over the acceptable minimum level of 0.7. According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), factor loadings must be at least 0.70 to indicate reliability. Thus, the final model was used as the foundation for future PLS-SEM evaluation.

3.1. Construct reliability, indicator reliability and convergent validity

An assessment of the model determines its fitness latent variables by examining the internal consistency construct reliability, indicator reliability, and convergent validity according to the PLS-SEM results. The numerous reliability and validity items found in this study are listed in Table .

Table 2. Construct reliability and validity

The Cronbach’s alpha values were all above .70, ranging from .742 to 1.000, as shown in Table . Table shows that all constructions have a composite reliability above the criterion of.7 indicates they are stable (Gefen & Straub, Citation2005). In addition, according to Henseler et al. (Citation2015), composite reliability can be used to measure construct reliability. In this study, the composite reliability ranges from .827 to 1.000. According to Saunders et al. (Citation2009), internal consistency reliability entails matching responses to each item in the questionnaire with responses to other questions. Table shows that the composite reliability values for all the latent variables were greater than .60. Given the chosen sample size, this shows that the scale can be deemed dependable (Hair et al., Citation2019).

The study again relies on the rho_A finding because it is considered a far more stringent measure of indication reliability than CA (Hair et al., Citation2019). Table shows that all the constructs’ rho_A scores were greater than .70, ranging from .864 to 1.000, indicating that they met the reliability criteria. Consequently, the scale can be regarded as trustworthy or reliable.

Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) recommended an extracted minimum average variance (AVE) of .50 to demonstrate convergent validity for a built-in item load model. This implies that each latent variable should be assessed. This is true for all constructs in this study; the minimum AVE was.550 (see Table ). The proportion of variation captured by the construct concerning measurement error for that construct is indicated by an AVE value of ”.550” or more. Because all latent variables have AVE values larger than the minimum criterion of .50, the results show that the model is convergent. Multiple items used to measure the same notion have convergent validity, which means they agree with each other (MacKenzie et al., Citation2011).

3.2. Discriminant Validity (DV)

The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio and Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criteria were largely used to test the DV. According to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the squared root of the AVE in each latent variable can be used to show discriminant validity. Compared to Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion, the HTMT ratio is regarded as a superior and higher-quality measure of discriminant validity (DV), and Sarstedt et al. (Citation2019) proposed using it to assess DV. As a result, the DV was evaluated in the study using the HTMT score.

All construct values in Table fall below the HTMT of 1.0. According to Henseler et al. (Citation2015), the HTMT ratio should not exceed 1.00. This proves that each construct is unique.

Table 3. Discriminant and convergent validity of constructs

3.3. Structural modeling and hypothesis testing

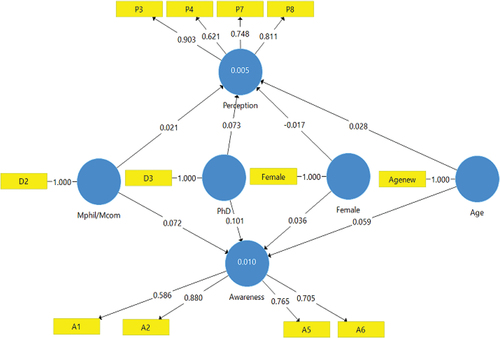

Figure shows the model extracted from the PLS algorithm used to test the six formulated hypotheses.

3.4. Assessment of the structural model

The study presented its assumptions after determining that the measurement model satisfied the PLS-SEM criterion. As advised by Hair et al. (Citation2019), this was accomplished by determining the direction and strength using the path coefficient (β) and degree of significance with t-statistics derived through 5000 bootstraps generated at a 10% significance level. In light of the foregoing, Table present the results of the study’s six hypotheses.

Table 4. Significance of the model

The findings for the six research hypotheses are presented in Table . Following Hair et al. (Citation2019), p-values were used to present the results. They advised that p-values of 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01 can be used to determine the significance of a study. Additionally, to support the study’s hypothesis, the anticipated direction of the route coefficients was explained using Gefen and Straub’s (Citation2005) criterion. According to him, a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.10 indicate a weak or small correlation. In addition, a correlation coefficient of 0.30 represents a moderate correlation, while a correlation coefficient of 0.50 represents a large or strong correlation.

The results in Table reveal that out of the six research hypotheses, only one was rejected (H5, and the remaining five were accepted. That is, Hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4, and H6.

4. Discussion

This study examined the socio-demographic characteristics that lead students to be academically dishonest. Many developed and developing countries deploy plagiarism detection software to safeguard the integrity of student work. Thus, previous studies in developed economies have demonstrated that some socio-demographic characteristics of students have a powerful influence on their perceptions and awareness of plagiarism (Jereb et al., Citation2018; Thompsett & Ahluwalia, Citation2010; Tremayne & Curtis, Citation2021).

The majority of participants were males (62.4%). This is reflective of the gender distribution across the study population. However, despite the gender disparity, no statistically significant relationship existed between males’ and females’ perceptions of plagiarism. Students plagiarism has no bearing on gender. It can be concluded that since the categories of students were all postgraduate students, there was no difference in their perception of plagiarism. These findings are consistent with those of prior studies conducted by Du (Citation2020) and Hensley et al. (Citation2013), who reported no gender differences in students’ perceptions of plagiarism. However, these findings contradict those of studies by Issrani et al. (Citation2021), Reilly et al. (Citation2018), and Peterson and Parr (Citation2012), who report statistically significant gender differences in students’ perceptions of plagiarism.

The current study’s findings also demonstrated no statistically significant relationship between the age of postgraduate students and their awareness of plagiarism. It could be that students’ awareness of plagiarism has no bearing on their age. This result supports the view of Idiegbeyan-Ose et al. (Citation2016), who concluded that no relationship exists between students’ awareness of plagiarism and their age. The distribution does not reflect any pattern that suggests whether awareness increases or decreases as age increases. There is no discernible trend in the academic dishonesty of plagiarism that indicates whether awareness rose or diminished with the age of the students.

Another focus of this study was to examine the relationship between postgraduate students’ age and their perceptions of plagiarism. The study revealed no statistically significant relationship between postgraduate students’ ages and their perception of plagiarism. It can be concluded that students’ perceptions of plagiarism do not differ according to the age of postgraduate students. These results suggest that postgraduate students across age groups agree on the factors contributing to plagiarism. The findings are aligned with published research showing no significant relationship between postgraduate students’ age and their perception of plagiarism (Alimorad, Citation2018; Tran et al., Citation2022). This contradicts the view of Hu and Lei (Citation2015), who indicated that older postgraduate students perceive plagiarism more seriously than younger students.

Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between the postgraduate students’ academic levels and their perception of plagiarism. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups of postgraduate students, suggesting that they had the same perception of plagiarism. This conclusion agrees with Newton’s (Citation2016) view that no significant difference exists between students’ academic levels and their perceptions of plagiarism. The findings are in complete variance with published research showing a significant relationship between postgraduate students’ academic level and their perception of plagiarism (Sutton et al., Citation2014; Tran et al., Citation2022).

Additionally, there was a statistically significant difference between the postgraduate students’ academic levels and their awareness of plagiarism. In this study, postgraduate students’ academic levels differed in their awareness of plagiarism, which may be related to the assessment procedures they encountered. Another possible reason might be the different levels of years spent on the various postgraduate programs. The findings are aligned with published research showing statistically significant differences between postgraduate students’ academic levels and their awareness of plagiarism (Du, Citation2022; Perkins & Roe, Citation2020).

Another focus of this study was to examine the statistically significant differences between the gender of postgraduate students and their awareness of plagiarism. The study revealed no statistically significant difference in the gender of postgraduate students and their awareness of plagiarism. This finding implies that postgraduate students’ awareness of plagiarism has no bearing on their gender. However, these findings contradict Jereb et al. (Citation2018), who reported statistically significant gender differences in students’ awareness of plagiarism.

5. Implication of this study

The findings of this study may have some effect on academic managers, librarians, lecturers, postgraduate students, and researchers. The findings of study can be leveraged upon by academic managers, research administrators, librarians and lecturers in creating appropriate training courses and seminars for all postgraduate students and implementing them in the curriculum. Additionally, educators and researchers need to be more conscious of their obligation to teach students ethical principles, academic integrity and sound scientific methodology throughout the curriculum. This can contribute significantly to addressing the menace of plagiarism. The study finding would help increase awareness of plagiarism and other academically dishonest conduct. It is believed that increased awareness of the negative consequences of plagiarism would help, if not eradicate, its occurrence. It also hoped that the study finding would set the tone for a more open conversation between university instructors and their students in designing educational interventions that would help address the menace.

6. Conclusion, limitations and future work

This is the first study to examine the socio-demographic variables (gender, age, academic level) on postgraduate students’ perceptions and awareness of plagiarism at a Ghanaian University. SEM was used to assess outcomes. A regression analysis was performed using the PLS technique. The results of this study could serve as a starting point for subsequent research in most developing countries and be employed in selecting appropriate participants in future studies. The findings of this study highlight postgraduate students’ perceptions and awareness of plagiarism. The findings revealed no statistically significant relationship between the perception of plagiarism among men and women. Similarly, there was no statistically significant relationship between the age of the postgraduate students and their awareness of plagiarism. The study also revealed no statistically significant relationship between postgraduate students’ age and their perception of plagiarism. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between the postgraduate students’ academic levels and their perception of plagiarism.

However, there was a statistically significant difference between the postgraduate students’ academic levels and their awareness of plagiarism. This situation raises concerns because our academic discourse appears to be losing touch with ethics and ethical values, which unfairly violates the rules of research or education. Therefore, all postgraduate students must receive explicit instruction and formal education on finer points of plagiarism if they are to comprehend and value the idea. In-depth teaching of the principles of academic writing must be provided to postgraduate students. This finding shows that all postgraduate students need to be included in creating intervention programs that aim to reduce occurrences by developing suitable training seminars and courses. Finally, there was no statistically significant difference between the gender of the postgraduate students and their awareness of plagiarism. This implies that postgraduate students’ awareness of plagiarism is gender-neutral.

It is important to note that the scope of the current study was restricted to a Ghanaian University. This may affect the generalizability of our findings. However, these findings could provide valuable insights for managers of academic and research institutions to unearth the factors that contribute to plagiarism and defeat academic integrity. Again, because this study was conducted in one geographical area, more research is required to corroborate the findings. Another problem is using a single instrument, which may not provide a true picture of Ghanaian postgraduate students’ perceptions. Taking lessons from the above-stated limitations of the current study, it is highly recommended that nationwide mixed-method research be conducted to portray a clearer picture of how Ghanaian postgraduate student perceive plagiarism and the factors that shape their perception of plagiarism.

Availability of data

The datasets used and analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isaac Nketsiah

Isaac Nketsiah is the founding Technology Transfer Officer at the Directorate of Research, Innovation and Consultancy of the University of Cape Coast (UCC). He is also the Turnitin Account Administrator at the same university. Isaac’s research focuses on ethics, intellectual property management and SMEs management.

Osman Imoro

Osman Imoro holds a Ph.D. in Information Science (UNISA) and head of E-Resources at the Sam Jonah Library, UCC. Osman research domains include institutional repositories, information literacy and e-resources management.

Kwaku Anhwere Barfi

Kwaku Anhwere Barfi is the sectional head and an academic Librarian in the Department of Information Technology and Research Support. He holds a PhD. in Information Science.

Eunice Amoah

Eunice Amoah holds a Master’s degree in Public Administration and a certificate in Early Childhood Education from the University of New Mexico.

Cosmas Rai Amenorvi

Cosmas Rai Amenorvi is a Senior Research Fellow in the Quality Assurance and Academic Planning Directorate of the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana.

References

- Abbas, A., Fatima, A., Arrona-Palacios, A., Haruna, H., & Hosseini, S. (2021). Research ethics dilemma in higher education: Impact of internet access, ethical controls, and teaching factors on student plagiarism. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 6109–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10595-z

- Alasmar, R. (2019). Philosophy and perception of beauty in architecture. American Journal of Civil Engineering, 7(5), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajce.20190705.12

- Alimorad, Z. (2018). The good, the bad, or the ugly: Examining Iranian EFL university teachers’ and graduate students’ perceptions of plagiarism. TEFLIN Journal - a Publication on the Teaching and Learning of English, 29(1), 19–44. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v29i1/19-44

- Amponsah, B., Dey, N. E., & Oti-Boadi, M. (2021). Attitude toward cheating among Ghanaian undergraduate students: A parallel mediational analysis of personality, religiosity and mastery. Educational Psychology, 8(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2021.1998976

- Amzalag, M., Shapira, N., & Dolev, N. (2022). Two sides of the coin: Lack of academic integrity in exams during the corona pandemic, students’ and lecturers’ perceptions. Journal of Academic Ethics, 20(1), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09413-5

- Bateman, C. R., & Valentine, S. R. (2010). Investigating the effects of gender on consumers’ moral philosophies and ethical intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 393–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0386-4

- Becker, D. A., & Ulstad, I. (2007). Gender differences in student ethics: Are females really more ethical? Plagiary: Cross-disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication, and Falsification. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.5240451.0002.009

- Chaudhry, I. S., Sarwary, S. A. M., El Refae, G. A., & Chabchoub, H. (2023). Time to revisit existing student’s performance evaluation approach in higher Education sector in a New Era of ChatGPT — a case study. Cogent Education, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2210461

- Curry, P., & Rainey, J. (2007). University gets tough on cheating. Available at: http://www.uga.edu/gm/300/Fear/Tough.html (accessed on April 15).

- Du, Y. (2020). Evaluation of intervention on Chinese graduate students’ understanding of textual plagiarism and skills at source referencing. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1601680

- Du, Y. (2022). Adopting critical-pragmatic pedagogy to address plagiarism in a Chinese context: An action research. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 57, 101112.

- Eaton, S. E. (2023). Academic and research integrity as transdisciplinary fields of scholarship and professional practice. In S. E. Eaton (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-079-7_165-1

- Fatima, A., Sunguh, K. K., Abbas, A., Mannan, A., & Hosseini, S. (2019). Impact of pressure, self-efficacy, and self-competency on students’ plagiarism in higher education. Accountability in Research, 27(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1699070

- Fornell, C. G., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01605

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity invariance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hensley, L. C., Kirkpatrick, K. M., & Burgoon, J. M. (2013). Relation of gender, course enrollment, and grades to distinct forms of academic dishonesty. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.827641

- Hu, G., & Lei, J. (2015). Chinese university students’ perceptions of plagiarism. Ethics Behaviour, 25(3), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2014.923313

- Idiegbeyan-Ose, J., Nkiko, C., & Ifeakachuku, O. (2016). Awareness and perception of plagiarism of postgraduate students in selected Universities in Ogun State, Nigeria. Library Philosophy & Practice (E-Journal). http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1322

- Issrani, R., Alduraywish, A., Prabhu, N., Alam, M. K., Basri, R., Aljohani, F. M., Alolait, M. A., Alghamdi, A. Y., Alfawzan, M. M., & Alruwili, A. H. (2021). Knowledge and attitude of Saudi students towards plagiarism: A cross-sectional survey study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312303

- Iyer, R., & Eastman, J. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty: Are business students different from other College students? Journal of Education for Business, 82(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.82.2.101-110

- Jereb, E., Urh, M., Jerebic, J., & Šprajc, P. (2018). Gender differences and the awareness of plagiarism in higher education. Social Psychology of Education, 21(2), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9421-y

- Löfström, E. (2015). Academic integrity in social sciences. In Handbook of academic integrity. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-079-7_47-1

- MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 293–334. https://doi.org/10.2307/23044045

- Mensah, C., Azila-Gbettor, E. M., & Asimah, V. (2018). Self-reported examination cheating of alumni and enrolled students: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10805-017-9286-X

- Ministry of National Education Regulation. (2010). Article 17 on plagiarism prevention and control in colleges. Jakarta.

- Morgan, J. (2016). University financial health check 2016. Times Higher Education. https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1097708/6.Article_University_financial_health_check_2016.pdf

- Mulisa, F., & Ebessa, M. A. (2021). The carryover effects of college dishonesty on the professional workplace dishonest behaviors: A systematic review. Cogent Education, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1935408

- Mwamwenda, T. S. (2006). Academic integrity: South African and American university students. The Journal of Independent Teaching and Learning, 1(1), 34–44. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC131630

- Nasir, M. S., Aslam, M. S., & Nawaz, M. M. (2011). Can demography predict academic dishonest behaviors of students? A case of Pakistan. International Education Studies, 4(2), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v4n2p208

- Newton, P. (2016). Academic integrity: A quantitative study of confidence and understanding in students at the start of their higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199

- Nova, M., & Utami, W. (2018). EFL students’ perception of Turnitin for detecting plagiarism on academic writing. International Journal of Education, 10(2), 141–148. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/209015/

- Ozogul, G., Johnson, A. M., Atkinson, R. K., & Reisslein, M. (2013). Investigating the impact of pedagogical agent gender matching and learner choice on learning outcomes and perceptions. Computers & Education, 67(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.02.006

- Perkins, M., Gezgin, U. B., & Roe, J. (2020). Reducing plagiarism through academic misconduct education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1–15.

- Peterson, S. S., & Parr, J. M. (2012). Gender and literacy issues and research: Placing the spotlight on writing. Journal of Writing Research, 3(3), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2012.03.03.1

- Rakovski, C. C., & Elliott, S. L. (2007). Academic dishonesty: Perceptions of business students. College Student Journal, 41(2), 466–475. https://projectinnovation.biz/csj_2006.html

- Reilly, D., Neumann, D. L., & Andrews, G. (2018). Gender differences in reading and writing achievement: Evidence from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). American Psychologist, 74(4), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000356

- Saana, S. B. B., Ablordeppey, E., Mensah, N. J., & Karikari, T. K. (2016). Academic dishonesty in higher education: Students perceptions and involvement in an African institution. BMC Research Notes, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2044-0

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Becker, J.-M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order models. Australasian Marketing Journal, 27(3), 197–211.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Siaputra, I. B., & Santosa, D. A. (2015). Handbook of academic integrity. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-079-7_4-1

- Siedlecki, S. L. (2020). Understanding descriptive research designs and methods. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 34(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000493

- Sutton, A., Taylor, D., & Johnston, C. (2014). A model for exploring student understandings of plagiarism. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.706807

- Taylor, L., Nicky, E., & de Lambert, K. (2002). Academic dishonesty realities for New Zealand tertiary education staff and New Zealand tertiary education institutions. In Brisbane: Proceedings of the ATEM-AAPPA Conference, 2002.

- Thompsett, A., & Ahluwalia, J. (2010). Students turned off by Turnitin? Perception of plagiarism and collusion by undergraduate bioscience students. Bioscience Education, 16(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3108/beej.16.3

- Times Higher Education World University Rankings. (2023). https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/university-cape-coast

- Tran, M. N., Hogg, L., & Marshall, S. (2022). Understanding postgraduate students’ perceptions of plagiarism: A case study of Vietnamese and local students in New Zealand. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 18(3), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00098-2

- Tremayne, K., & Curtis, G. J. (2021). Attitudes and understanding are only part of the story: Self-control, age and self-imposed pressure predict plagiarism over and above perceptions of seriousness and understanding. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(2), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1764907

- Ubaka, C., Gbenga, F., Sunday, N., & Ndidiamaka, E. (2013). Academic dishonesty among Nigeria pharmacy students: A comparison with United Kingdom. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 7(27), 1934–1941. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJPP2013.3587

- Wang, H., & Zhang, Y. (2022). The effects of personality traits and attitudes towards the rule on academic dishonesty among university students. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 14181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18394-3

Appendix: Questionnaire

Ademic integrity: Do socio-demographic differences in perception and awareness of plagiarism matter?

Questionnaire

Dear Participant,

You are being invited to consider participating in a study that involves research on understanding socio-demographic differences in perception and awareness of plagiarism. We will be most grateful if you could take time off your busy schedule to answer this questionnaire. The answers given will be used for academic purposes only. Please be assured that information provided will be treated with absolute confidentiality. Participation in this survey is highly valued, but strictly voluntary. You are free to withdraw consent at any time.

Questions and Person to Contact

The researchers will answer all questions that you may have to clear your doubts. If you have any questions, please send them to the corresponding author, Isaac Nketsiah – [email protected]Mobile: +233 245,890,114. Many thanks for your cooperation.

Section A – Biodata

Gender of the respondent. 1. Male [] 2. Female []

Age of the respondent … … … … … … … .

What College do you belong?

College of Agricultural and Natural Sciences []

College of Health and Allied Sciences []

College of Education Studies []

College of Distance Education []

College of Humanities and Legal Studies []

(4) Level of study a) MPhil/MCom [] b). PhD []

Section B- Awareness of Turnitin

Kindly indicate your appropriate response on your awareness of plagiarism

The scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Not sure, 4 = Agree, 5 = strongly agree.

Section C– Perception of Plagiarism

Kindly indicate your appropriate response on what constitute plagiarism

The scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Not sure, 4 = Agree, 5 = strongly agree.

Thank you so much for your time.