Abstract

This research investigates the factors influencing plagiarism from the perspective of the fraud diamond framework. It aims to obtain empirical evidence that higher pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and competencies influence an increase in plagiarism. Currently, information technology has rapidly advanced, and artificial intelligence has become more sophisticated. Issues related to artificial intelligence in higher education primarily focus on concerns about threats to academic integrity and the potential for use in committing plagiarism. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the role of understanding of artificial intelligence in increasing plagiarism and moderating the influence of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and competencies on plagiarism. Research data were collected through surveys of postgraduate students in accounting and business from public and private universities in Indonesia and Malaysia, with 377 respondents. This study documents that higher levels of pressure, rationalization, competencies, and understanding of artificial intelligence lead to increased plagiarism. However, this research was unable to provide evidence that opportunity influences plagiarism. Meanwhile, evidence suggests that understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive influence of rationalization on plagiarism. Conversely, this research did not find evidence that understanding of artificial intelligence moderates the influence of pressure, opportunity, and competencies on plagiarism.

Public Interest Statement

This study examines a specific type of academic misconduct, i.e., plagiarism—the prevalence of plagiarism cases discovered by academics worldwide motivated this research. Using survey data from postgraduate accounting and business students in Indonesia and Malaysia, this study identifies several factors that drive students to commit plagiarism. Students are more likely to plagiarize when overwhelmed by heavy workloads, tight deadlines, competitive pressures, and the need to achieve certain goals. They tend to rationalize their actions, believing that plagiarism causes no harm. Additionally, students with confidence in their skills and competencies are more prone to plagiarize. The rapid and ongoing advancements in artificial intelligence and information technology provide quick and easy access to vast amounts of information, further facilitating plagiarism. Students who understand and comprehend how to utilize artificial intelligence may be more inclined to engage in plagiarism.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Plagiarism refers to a prominent form of academic misconduct, characterized by the act of appropriating another individual’s words or ideas and presenting them as one’s own without proper attribution (Park, Citation2003). In a highly competitive setting, where scientific accomplishments are utilized as evidence of an individual’s competency, plagiarism is occasionally employed to accelerate the acquisition of esteemed positions.

Plagiarism occurs in countries with diverse cultural backgrounds (Putra et al., Citation2023). A German politician allegedly committed plagiarism. In his dissertation, 49 out of 265 pages are suspected of unattributed quotations and direct copying from other works. Indonesia has seen notable instances of plagiarism, such as replicating the scientific work of peers and students and dissertations that resemble various scientific articles. Plagiarism cases are further complicated when they involve one’s own work, also called self-plagiarism. An instance of self-plagiarism that sparked controversy occurred between a prominent Dutch economic scientist and one of his doctoral students. Most of the dissertations these students authored were derived from his previous publications, lacking appropriate references (Putra et al., Citation2023).

Researchers have developed an interest in examining the causes of plagiarism due to the prevalence of plagiarism in higher education across multiple countries, some of which even involve prominent figures in those countries. Husain et al. (Citation2017) categorize the components investigated in prior research on plagiarism into five primary classifications: institutional, academic, personal, technological, and external factors. In addition, the study conducted by Uzun and Kilis (Citation2020) examined the antecedents of plagiarism, employing the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) as a theoretical framework. In contrast to the classification conducted by Husain et al. (Citation2017) along with the theory implemented by Uzun and Kilis (Citation2020), this study examines the determinants of plagiarism by adopting the fraud diamond framework (Wolfe & Hermanson, Citation2004). According to the statement mentioned earlier, fraud is attributed to four key factors: pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and competencies. The rationale behind employing the fraud diamond framework lies in the fact that plagiarism, as a type of fraudulent activity, holds significant relevance to research when viewed through the lens of fraud framework.

When examining the factors influencing plagiarism, it is crucial to also consider environmental factors in the academic world. An environment characterized by rapid advancements in information technology and artificial intelligence, widespread internet connectivity, and immediate access to diverse knowledge strengthens the potential for plagiarism to arise (Smith et al., Citation2023). The integration of artificial intelligence within the academic sphere has a dualistic nature. Though it facilitates convenient access to diverse material, it also presents a potential challenge to the preservation of academic integrity (Sullivan et al., Citation2023); therefore, it has the potential to encourage plagiarism (Köbis & Mossink, Citation2021). The present context possesses the capacity to foster the impact of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and competency on the occurrence of plagiarism. Hence, the objective of this study is to examine and gather empirical evidence regarding the impact of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, competencies, and understanding of artificial intelligence on plagiarism. In addition, the objective of this study is to empirically obtain evidence regarding the role of understanding of artificial intelligence in moderating the effects of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and competence on plagiarism.

This study is designed as a survey of accounting and business postgraduate students in Indonesia and Malaysia. Conducting a study on plagiarism among accounting and business post-graduate students, as well as the factors that contribute to it, is crucial due to the prevalence of this problem among business students (Khalid et al., Citation2020), a significant amount of plagiarism among students studying business (Perkins et al., Citation2020), as well as the high proportion of students majoring in business who have admitted to engaging in academic misconduct (Hendy & Montargot, Citation2019). Students of business will, in fact, advance to leadership positions in the industry. If the student believes that involvement in the business world necessitates unethical conduct, this could prove to be a very hazardous situation. Similar concerns arise in the accounting profession when it comes to academic misconduct, such as plagiarism, which can have detrimental effects and ultimately precipitate unethical conduct among professionals (Golden & Kohlbeck, Citation2020).

Through the analysis of data collected from 377 postgraduate students majoring in accounting and business from Indonesia and Malaysia, this study successfully demonstrated the positive influence of pressure, rationalization, competencies, and understanding of artificial intelligence on plagiarism. Furthermore, this study succeeded in finding evidence that understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive influence of rationalization on plagiarism. Nevertheless, this study failed to provide empirical evidence that opportunity positively affects plagiarism. Similarly, this study could not empirically obtain any evidence that understanding of artificial intelligence moderates the positive influence of pressure, opportunity, and competencies on plagiarism. The results of this study contribute to offering further evidence that the fraud diamond framework can be utilized not only in financial fraud research but also in academic fraud research. They also have the potential to serve as a foundation for public and private universities in Indonesia and Malaysia to develop strategies and policies aimed at mitigating plagiarism.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 contains a review of pertinent literature and the hypotheses development. Section 3 provides details of the research methods. Empirical analysis and discussions are presented in Section 4. Section 5 presents the conclusions of this study.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Plagiarism

Plagiarism is a prevalent form of academic misconduct that involves appropriating another individual’s words or ideas and presenting them as one’s own without proper attribution (Park, Citation2003). Although plagiarism is not a new phenomenon, it continues to pose a significant challenge for the academic and educational communities. Present-day advancements in information technology and artificial intelligence sophistication enable the proliferation of plagiarism in an ever more diverse array of forms.

Intentional plagiarism and unintentional plagiarism are two distinct categories of plagiarism. Intentional plagiarism is executed with a comprehensive understanding of the concept of plagiarism, its definition, and strategies for its prevention. Unintentional plagiarism, on the other hand, occurs inadvertently as a result of insufficient knowledge and skills to prevent it (Selemani et al., Citation2018). Plagiarism refers to the act of appropriating the ideas or work of another, hence necessitating academics to refrain from engaging in intentional plagiarism (Specht, Citation2019). Researchers have developed various classifications of plagiarism, as suggested by Walker (Citation1998), who distinguishes between sham paraphrasing, which involves presenting the copied text as a paraphrase by removing quotations, illicit paraphrasing, which encompasses other forms of plagiarism such as plagiarizing with the permission of the original author, verbatim copying without citations, self-plagiarism, ghostwriting, and copying other students’ assignments without their consent or stealing. According to Mozgovoy et al. (Citation2010), academic plagiarism can be categorized into five distinct forms. These forms include verbatim copying, concealing plagiarism through paraphrasing, employing technical strategies to exploit vulnerabilities in existing plagiarism detection systems, intentionally utilizing inaccurate references, and engaging in challenging forms of plagiarism. Both human and computer systems can detect several forms of plagiarism, including concept plagiarism, structural plagiarism, and cross-language plagiarism. Elaborating further, Eisa et al. (Citation2015) classified plagiarism into two distinct categories, i.e. literal plagiarism and intellectual plagiarism. Literal plagiarism refers to duplicating content with alterations, whereas intellectual plagiarism encompasses several forms such as paraphrasing, summarizing, translating, and incorporating ideas from other sources. Meanwhile, Foltýnek et al. (Citation2019) distinguish plagiarism into characters-preserving plagiarism, syntax-preserving plagiarism, semantics-preserving plagiarism, idea-preserving plagiarism, and ghostwriting.

2.2. Fraud diamond framework

A framework established by Cressey in 1953 served as the foundation for the fraud diamond, which Wolfe and Hermanson (Citation2004) later expanded. Originally designed to distinguish fraud and its motivations from other financially motivated crimes, such as burglary and robbery, Cressey’s framework is called the fraud triangle.

According to the fraud triangle, fraudulent activities are facilitated by perceived pressure, perceived opportunity, and rationalization. Perceived pressure refers to the external influence or motivation experienced by an individual, which motivates them to engage in fraudulent or unethical behavior (Vousinas, Citation2019). The source of perceived pressure is non-shareable economic issues. A concern is deemed non-shareable by individuals due to the social censure they perceive to be associated with the matter. Additionally, high self-esteem may deter people from discussing their concerns (Dorminey et al., Citation2012). Perceived opportunity refers to an individual’s subjective view of specific circumstances that they can intentionally exploit for personal gain. Simultaneously, the individual possesses a sense of assurance over the low likelihood of detecting self-beneficial conduct and its potential adverse consequences (Vousinas, Citation2019). Perceived opportunity therefore necessitates the capacity to perpetrate fraud undetected. Perceived opportunity can manifest due to deficiencies in the oversight and evaluation of authority and control delegated to individuals (Dorminey et al., Citation2012). Rationalization refers to the deliberate attempt made by an individual to mitigate cognitive dissonance. Fraudsters perceive the predicament they encounter as an anomaly, enabling them to avoid being perceived unfavorably. Rationalization engenders a sense of indifference among fraud perpetrators toward the fraudulent activities they have perpetrated (Dorminey et al., Citation2012), and provides a rationale for engaging in fraudulent activities (Smith et al., Citation2021).

The fraud triangle was expanded by Wolfe and Hermanson (Citation2004) with the inclusion of a fourth construct, specifically capabilities or competencies, resulting in the formulation of the fraud diamond framework. Competencies are associated with an individual’s perception of their personal attributes and capabilities (Vousinas, Citation2019; Wolfe & Hermanson, Citation2004). Competencies refer to the requisite abilities, qualities, and expertise necessary for the successful execution of fraudulent activities, hence enabling the realization of opportunities. An individual’s perception of their own competence and capacity to engage in plagiarism is influenced by their belief in the low likelihood of being detected if they perform such an act (Smith et al., Citation2021).

Academic misconduct, including plagiarism, is essentially a type of fraudulent activity. The factors surrounding academic misconduct resemble to instances of financial fraud. Hence, the fraud diamond components can be effective inside the realm of academic misconduct, encompassing acts such as plagiarism. Students perceive a need to attain specific objectives and believe that they cannot succeed without engaging in plagiarism and having the chance to plagiarize in different forms. Students argue that engaging in plagiarism for certain reasons justifies the acceptability of such behavior. In addition to this, students possess the ability to engage in acts of plagiarism. Every component of the fraud diamond serves as a prognostic indicator for instances of plagiarism (Burke & Sanney, Citation2018). In the following section of this paper, each element of the fraud diamond is explained as a determinant of plagiarism.

2.2.1. Pressure and plagiarism

The first dimension of the fraud diamond relates to pressure, specifically, the individual’s inclination to undertake specific behaviors to satisfy personal interests (Bierstaker et al., Citation2024). The individual’s perceived pressure will drive them to engage in unethical behavior, and motivating them to perpetrate and conceal fraudulent activities (Umar et al., Citation2020).

Academic pressure refers to the influence exerted by internal and external sources on individuals to attain specific academic accomplishments. This pressure subsequently motivates individuals to engage in illicit conduct such as plagiarism (Smith et al., Citation2021). The inclination to engage in academic misconduct, such as plagiarism, arises from various significant variables. Students engage in plagiarism as a means to deliver an image of intelligence and success to their peers, families, or employers. The motivation for students to engage in plagiarism can be attributed to several factors, including their impressions of the extensive nature of tasks assigned by lecturers, the limited time available to complete them, and the perceived difficulty in completing these assignments without resorting to plagiarism. Moreover, plagiarism can be motivated by a student’s goal to uphold their GPA and financial support (Al Serhan et al., Citation2022; Smith et al., Citation2021, Citation2023; Utami & Purnamasari, Citation2021). Additional factors that motivate students to engage in cheating including plagiarism incorporate group pressures, weak academic performance, excessively challenging assessment tasks, high assessment weightings, and limited opportunities for feedback (Ahsan et al., Citation2022).

Regardless of the underlying reasons, if students consider that the advantages of engaging in plagiarism outweigh the perceived drawbacks, such as the likelihood of being found and the potential punishments, they are more likely to engage in plagiarism (Smith et al., Citation2021). As the level of pressure on a student increases, the likelihood of the student engaging in academic cheating or academic fraud behavior (Al Shbail et al., Citation2021; Alshurafat et al., Citation2023; Choo & Tan, Citation2008; Wardani & Putri, Citation2023) including plagiarism also increases (Al Serhan et al., Citation2022). Hence, this research proposes a hypothesis, as follows:

H1: Pressure has a positive effect on plagiarism.

2.2.2. Opportunity and plagiarism

In the fraud diamond framework, opportunity constitutes the second dimension. Weak controls that lead individuals to believe that their fraudulent activities will go undetected establish opportunities, among other factors (Umar et al., Citation2020). Fraud arises when the circumstances provide a favorable environment for people to engage in. Opportunity, in this context, refers to a combination of individual and environmental factors that facilitate the occurrence of unethical behavior (Smith et al., Citation2021; Wolfe & Hermanson, Citation2004).

The absence of effective systems for detecting and preventing academic fraud, such as plagiarism, presents an opportunity within the academic realm (Bierstaker et al., Citation2024). A student perceives a favorable circumstance to engage in plagiarism when other students have committed it without facing consequences, when professors are aware of the plagiarism but fail to impose any penalties on students, or when academic guidelines do not explicitly outline stringent penalties for the act of plagiarism (Al Serhan et al., Citation2022; Bierstaker et al., Citation2024; Burke & Sanney, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2021). The circumstances that present this opportunity cause students to perceive a minimal likelihood of plagiarism detection as a risk. Before plagiarizing, students are self-assured that they have a minimal chance of being punished and that they can complete the task successfully (Smith et al., Citation2021). When students perceive a lack of sufficient supervision and an inadequate detection mechanism, resulting in a high likelihood of academic misconduct (Al Shbail et al., Citation2021; Alshurafat et al., Citation2023; Choo & Tan, Citation2008; Wardani & Putri, Citation2023) and plagiarism, they are more likely to engage in such behavior without concern for detection (Bierstaker et al., Citation2024). Thus, this research hypothesizes:

H2: Opportunity has a positive effect on plagiarism.

2.2.3. Rationalization and plagiarism

Rationalization, as the third dimension of the fraud diamond, refers to the internal conflict individuals undergo to rationalize the fraudulent activities they are engaging in. Rationalization is a cognitive process employed by humans to justify and rationalize unethical behaviors, including acts of cheating. Before engaging in unethical behavior and fraudulent acts, individuals must engage in rationalization. This construct is founded upon an individual’s ethical views or principles (Al Serhan et al., Citation2022). The final stage in an individual’s ethical decision-making process is rationalization, occurring before the development of intention to engage in an unethical activity and/or its actual execution. The rationalization process depends on how an individual perceives their capabilities, opportunities, and motivation (Smith et al., Citation2021).

Rationalization enables students to perceive plagiarism through the lens of their own beliefs. Regarding plagiarism, students often justify their actions by citing academic pressures and the desire to uphold their reputation within the academic community. Students rationalize plagiarism in response to perceived injustices, citing the prevalence of the behavior among peers or the belief that it does not negatively impact others (Smith et al., Citation2021). As the level of rationalization increases, so does the likelihood that a student will engage in academic fraud (Al Shbail et al., Citation2021; Alshurafat et al., Citation2023; Choo & Tan, Citation2008; Wardani & Putri, Citation2023) including plagiarism. Drawing upon this line of reasoning, this study proposes a hypothesis:

H3: Rationalization has a positive effect on plagiarism.

2.2.4. Competencies and plagiarism

Wolfe and Hermanson (Citation2004) incorporated the competency dimension into the fraud diamond as the fourth dimension. Competencies refer to an individual’s self-perception of their capabilities and qualities (Vousinas, Citation2019; Wolfe & Hermanson, Citation2004). Capabilities refer to the requisite skills, qualities, and competence necessary for the perpetration of fraudulent activities, hence enabling the actualization of opportunities (Smith et al., Citation2021).

In the realm of plagiarism, competencies refer to the cognitive abilities, creativity, and understanding possessed by students that are deemed adequate for engaging in acts of plagiarism. Competencies encompass students’ assurance that their instances of plagiarism will not be identified. The students’ perception of their own capabilities and aptitude to engage in plagiarism is influenced by their confidence in the low likelihood of being detected if they perform such acts (Smith et al., Citation2021). There is a positive correlation between a student’s competencies, encompassing their skills, expertise, and confidence in engaging in plagiarism, and their inclination to participate in such activities. Therefore, this study hypothesizes:

H4: Competencies have a positive effect on plagiarism.

2.3. Understanding of artificial intelligence

The rapid advancement of information technology has led to a corresponding increase in the sophistication of artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence systems can be categorized into two distinct classifications: strong and weak artificial intelligence (Dehouche, Citation2021). The concept of strong artificial intelligence, alternatively referred to as artificial general intelligence, refers to a theoretical kind of artificial intelligence that possesses cognitive capacities comparable to those of humans (Grace et al., Citation2018). In contrast, weak artificial intelligence, alternatively referred to as narrow artificial intelligence, is designed to execute particular cognitive functions and is presently prevalent in individuals’ everyday routines (Dehouche, Citation2021).

Artificial intelligence is a subject of considerable debate, particularly due to the growing prevalence of ChatGPT and its potential impact on higher education. The primary concern regarding artificial intelligence in higher education revolves around the potential risks it exposes to academic integrity (Sullivan et al., Citation2023) and its possible application in the context of plagiarism (Köbis & Mossink, Citation2021). Rapid and ongoing progress in information technology and artificial intelligence offers quick and immediate access to a wide range of information. This creates new possibilities for plagiarism to become more prevalent. It is expected in this study that students with a strong grasp of artificial intelligence and its applications may be more inclined to participate in plagiarism, leading to the following hypothesis:

H5: Understanding of artificial intelligence has a positive effect on plagiarism.

2.4. The moderating role of understanding of artificial intelligence

Presently, the realm of academia is situated within a context characterized by progressively advanced breakthroughs in information technology and artificial intelligence, alongside the growing prevalence of internet connectivity. Rapid and ongoing advancements in the field of information technology and artificial intelligence have facilitated enhanced ease and immediate accessibility to a wide range of information. As such, this phenomenon presents a broader scope for the occurrence of plagiarism compared to earlier times (Smith et al., Citation2023).

The relationship between pressure, opportunity, rationalization, competencies, and plagiarism is believed to be influenced by an individual’s understanding of artificial intelligence. In circumstances characterized by heightened academic pressure, students may be inclined to engage in acts of plagiarism. When students possess a comprehensive understanding of artificial intelligence, they are more likely to employ this knowledge as a means to alleviate academic stress. In other words, there is a positive correlation between the level of pressure experienced by students and their understanding of artificial intelligence, resulting in an increased likelihood of students engaging in acts of plagiarism. The understanding of artificial intelligence among students also presents potential avenues for their engagement in acts of plagiarism. In addition, students’ understanding of the diverse skills exhibited by artificial intelligence is progressively motivating them to justify plagiarism. Students are becoming more convinced that their act of plagiarism is acceptable and can be justified due to the availability of artificial intelligence, which enables them to engage in plagiarism. Similarly, the understanding of artificial intelligence among students is progressively enhancing their existing skills and capabilities, thereby fostering a greater propensity for engaging in acts of plagiarism. This research proposes four moderating roles in comprehending artificial intelligence, based on logical reasoning:

H6a: Understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive influence of pressure on plagiarism.

H6b: Understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive influence of opportunity on plagiarism.

H6c: Understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive influence of rationalization on plagiarism.

H6d: Understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive influence of competencies on plagiarism.

3. Research method

3.1. Population and respondent

The study’s population consisted of postgraduate students pursuing master’s and doctoral degrees in accounting and business from both public and private universities in Indonesia and Malaysia. This study applied a methodology that involves selecting research samples from the most readily available members of the population. Hence, the research employed a non-probability sampling technique referred to as convenience sampling. The G*power Software is utilized to identify the minimum sample size, which is dependent on the number of predictors of one outcome variable.

The participation of respondents in this study is voluntary. The research instrument explicitly states this and also indicates that respondents can withdraw from participation at any time without providing any explanations or facing any penalty. Furthermore, this research protects the rights and confidentiality of respondent identities. The research instrument explicitly states that the information and responses provided by respondents throughout the questionnaire will be used for academic purposes only, treated as strictly confidential, and kept anonymous. If students agree to participate in the research, they are asked to select the ‘agree’ option for a statement of consent: ‘I hereby declare my consent to participate in this research and allow the researcher to keep and process the survey data that I have completed for the benefit of the study.’

3.2. Research data

The data utilized in this study is classified as primary data. The data collection approach employed was an online questionnaire survey developed in a Google form. Postgraduate students pursuing master’s and doctoral degrees in accounting and business at state and private universities in Indonesia and Malaysia were surveyed using questionnaires distributed through WhatsApp and other social media platforms. The survey questionnaire consists of two items of respondent participation statements, 34 items for six constructs (Appendix), and nine questions related to the demographic profile.

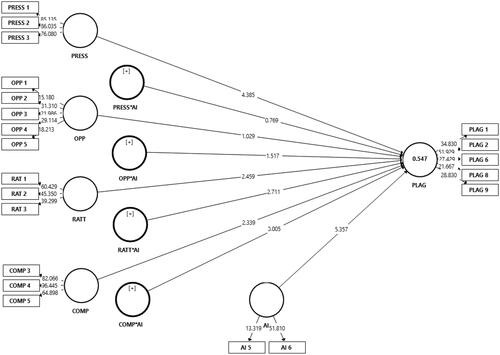

The minimum sample size was determined utilizing the G*power Software, resulting in a minimum requirement of 114 samples. This calculation was derived from the research model that the highest number of predictors pointed to in one outcome variable is nine (). It assumed a medium effect size of 0.15 and a required power of 0.80 at an alpha (α) level of 0.05 (Khasni et al., Citation2023). Three hundred seventy-seven responses were collected from postgraduate students studying in Indonesia (176 students) and Malaysia (201 students). No missing value issues were found such that all 377 observations could be used as a dataset for analysis. The respondents’ demographic profiles are detailed in .

Table 1. Respondents’ demography.

As exhibited in , the study found that the majority of the respondents were female (61.54%) and fell within the age range of 31 to 40 years (48.28%). The predominant level of education pursued is a master’s degree (62.60%). Most of the respondents studied at state universities (93.10%) and located in Malaysia (53.32%).

3.3. Research variables

This study incorporates dependent variables, independent variables, and moderating variables. The present study employs pressure, opportunity, rationalization, competency, and understanding of artificial intelligence as independent variables, with plagiarism serving as the dependent variable. Additionally, an understanding of artificial intelligence serves also as a moderating variable.

This study employs the plagiarism typology established by Foltýnek et al. (Citation2019) to identify indicators of plagiarism, specifically characters-preserving plagiarism, syntax-preserving plagiarism, semantics-preserving plagiarism, idea-preserving plagiarism, and ghostwriting. The classification of academic plagiarism was created by considering linguistic elements, specifically lexicon, syntax, and semantics. Foltýnek et al. (Citation2019) extended the scope of language by including the element of concept expression. Ghostwriting involves the engagement of a third party to compose original written content. A total of nine items (PLAG 1 – PLAG 9) were employed in this study to assess plagiarism, with the items being derived from Mavrinac et al. (Citation2010) and Ahmadi (Citation2014). Responses from respondents are gathered using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ (rated as 1) to ‘always’ (rated as 5) regarding the frequency of plagiarism.

The development of indicators for pressure, opportunity, and rationalization variables was based on Wolfe and Hermanson (Citation2004); meanwhile, the competency indicators are derived from Fadersair and Subagyo (Citation2019). The present study employed a set of four items to measure pressure (PRESS 1 – PRESS 4), five items to measure opportunities (OPP 1 – OPP 5), four items to measure rationalization (RAT 1 – RAT 4), and six items to measure competencies (COMP 1 – COMP 6) (Kumar et al., Citation2023; Mavrinac et al., Citation2010; Nurcahyono & Hanum, Citation2023; Oktarina & Ramadhan, Citation2023; Theotama et al., Citation2023). Respondents were instructed to indicate their level of agreement with the issues using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represented ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 represented ‘strongly agree’. The understanding of artificial intelligence is demonstrated by a set of 6 statement items (AI 1 – AI 6), derived from Jeffrey (Citation2020) and Uzun and Kilis (Citation2020). Respondents were requested to conduct a self-assessment of their level of understanding regarding their understanding of artificial intelligence using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 denoted ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 representing ‘strongly agree’.

3.4. Data analysis method

Following the hypotheses developed, this study utilizes a moderation research model, incorporating two types of effects to elucidate the relationship between variables. The initial impact is a direct one, illustrating the direct influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable. On another note, the second impact is the contingent effect, which takes into account the presence of moderating variables that can either strengthen or weaken the original impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2020). Partial least squares (PLS) modeling was employed to conduct hypothesis testing.

As an additional analysis, this research divides the sample into two subsamples, i.e. samples of students studying at universities in Indonesia and Malaysia. The findings of this analysis are expected to demonstrate any differences between the two countries.

4. Data analysis results and discussions

4.1. Data analysis results

Partial least squares (PLS) modeling is employed in this study to examine the measurement model and structural model (Ringle et al., Citation2015). The selection of PLS was based on its independence from normality assumptions, which is particularly advantageous in survey research where normal distribution is not typically assumed (Chin et al., Citation2003).

4.1.1. Measurement model

Initially, the outer loading test was conducted on all items in the questionnaire to assess composite reliability. This test aims to determine if all indicators exhibit reliable internal consistency. The threshold for the outer loading test is a minimum of 0.7. The test results show that several items have an outer loading of less than 0.7, or do not meet the threshold. The type of construct in this study is reflective, meaning that each item within a construct is substitutable or one item can be represented by another. Therefore, this study removes items with an outer loading of less than 0.7. The items and the outer loading results after the elimination of several items are presented in .

Table 2. Outer loading test.

The data collection in this study is based on a single source, thus necessitating the examination of the Common Method Bias issue through the full collinearity test (Kock, Citation2015; Kock et al., 2012). A VIF ≤ 5 indicates the absence of bias in the single source data. The obtained VIF value of less than 5 indicates that the single source data bias does not present a significant concern in the analysis of this study dataset. The findings of the test are displayed in .

Table 3. Full collinearity test.

Concerning the measurement model, this study evaluates the construct’s validity and reliability through the utilization of Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The acceptable threshold for the Composite Reliability value is 0.7 or higher, whilst the Average Variance Extracted value should be 0.5 or higher. The test results, as depicted in , indicate the absence of any issues related to construct validity and reliability.

Table 4. Construct validity and reliability tests.

In addition, the discriminant validity test is conducted to determine the extent to which a construct exhibits distinctiveness or uniqueness in comparison to other constructs. The Fornell-Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were employed to conduct the testing. When the Fornell-Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) of a construct is lower than 0.9, it is considered that the construct is distinct from other constructs. displays the results of the Fornell-Larcker Criterion (Panel A) and HTMT (Panel B), revealing that all constructs exhibit a value of less than 0.9, suggesting that each construct is distinct from the others.

Table 5. Discriminant validity tests.

4.1.2. Structural model

Following the measurement model test, a structural model test was conducted. The path model and the analysis results are illustrated in .

Meanwhile, the path coefficients are displayed in . The study found pressure (0.339 significant at the level of 1%), rationalization (0.192 significant at the level of 1%), competencies (0.188 significant at the level of 1%), and understanding of artificial intelligence (0.202 significant at the level of 1%) influence plagiarism positively. Opportunity does not affect plagiarism. The results of this study support the H1, H3, H4, and H5, while H2 is not supported. In terms of moderation effects, this study discovered that understanding of artificial intelligence strengthens the positive impact of rationalization on plagiarism (0.216 significant at the level of 1%). Understanding of artificial intelligence does not moderate the relationship between pressure, opportunity, competencies, and plagiarism. The results of this study successfully support H6c, while H6a, H6b, and H6d are not supported.

Table 6. Path coefficients.

4.1.3. Additional analysis

This research splits the sample into two subsamples and tests the influence of pressure, opportunity, rationalization, competency, and understanding of artificial intelligence on plagiarism and the moderating role of understanding of artificial intelligence for each subsample. The path coefficients are presented in . Panels A and B depict the results for the subsamples of students in Indonesia and Malaysia, respectively.

Table 7. Path coefficients for subsamples test.

The findings in the two subsamples demonstrate slight differences. For the Indonesian subsample, the test results indicate a significant positive influence of pressure and competencies on plagiarism. Understanding of artificial intelligence is found to strengthen the influence of rationalization on plagiarism but weaken the influence of opportunity on plagiarism. Meanwhile, for the Malaysian subsample, pressure, competencies, and understanding of artificial intelligence reveal significant positive influences on plagiarism. Additionally, an understanding of artificial intelligence is found to only strengthen the influence of rationalization on plagiarism.

4.2. Discussions

Following the research conducted by Al Serhan et al. (Citation2022), Bierstaker et al. (Citation2024), Smith et al. (Citation2021), Smith et al. (Citation2023), and Utami and Purnamasari (Citation2021), the present study’s results indicate the higher students’ perceived pressure, the higher the occurrence of plagiarism. A sense of competition among peers to publish articles constitutes the majority of the pressure that students feel in this situation. To be eligible for the final examination, postgraduate students in accounting and business are obligated to publish articles in reputable journals. Although students are subject to study period restrictions, the article publication procedure can be lengthy. Because some peers have achieved publication success while they have failed to meet this stipulation, students are consequently subjected to a sense of pressure. Students’ behavior also affects plagiarism. Poor scheduling and time management skills may lead students to seek shortcuts by plagiarizing. Students who are inclined to take risks, work in a non-native language, and anticipate lower grades are more likely to engage in plagiarism. Some students, driven by the potential for higher grades with minimal effort, consider plagiarism to be cost-effective (Ahsan et al., Citation2022). Students are compelled to accomplish their objectives through plagiarism as a result of these pressures.

The results of this study also indicate the higher students’ ability to rationalize their behavior, the higher the prevalence of plagiarism. These findings align with the research conducted Al Serhan et al. (Citation2022) and Smith et al. (Citation2021). This implies that students are more inclined to engage in plagiarism when they possess a greater sense of assurance that their actions are not unethical. Students attempt to rationalize their actions with a variety of justifications, including the fact that a large number of their peers do the same. Plagiarism is additionally impacted by the growing competency of students, which aligns with Smith et al. (Citation2021). Competencies refer to the attributes that empower students to identify instances of plagiarism, encompassing the sentiments of innocence that might accompany such breaches. Plagiarism also increases as a result of students’ understanding and competence of diverse forms of artificial intelligence, including the capacity to retrieve or collect information in a digital setting. The aforementioned findings validate the concerns expressed by Köbis and Mossink (Citation2021) as well as Sullivan et al. (Citation2023) regarding the potential implications of the rapid development of artificial intelligence on academic integrity and the facilitation of plagiarism.

Students’ understanding of artificial intelligence can strengthen the effect of rationalization on plagiarism. Those who grasp how artificial intelligence works know it can assist significantly in the initial stages of research. They perceive artificial intelligence as an effective tool for addressing broad topics, recognizing its ability to analyze extensive datasets and pinpoint key themes and trends across various fields. This thorough overview, aided by advanced analytical capabilities, allows students to narrow their research topics more effectively (Hutson, Citation2024). As artificial intelligence tools become more accessible, students who view plagiarism as common, harmless, and widespread among their peers may find additional justification for believing that engaging in plagiarism will not adversely affect others.

In contrast to numerous prior investigations (Al Serhan et al., Citation2022; Bierstaker et al., Citation2024; Smith et al., Citation2021; Citation2023; Utami & Purnamasari, Citation2021), opportunity does not appear to be a significant determinant of plagiarism. Despite the perception among students that penalties for plagiarism are insufficiently enforced, thereby creating an environment conducive to plagiarism, students are not motivated to engage in such activities. Furthermore, the present research discovered that an understanding of artificial intelligence did not strengthen the positive impact of pressure and competence on plagiarism. Overall, the research results suggest that the available opportunities do not encourage student plagiarism. Various factors influence plagiarism among accounting and business students, including pressure, competencies, understanding of artificial intelligence, and the perception of plagiarism.

When the test was separately executed on two different subsamples, i.e. students in Indonesia and Malaysia, it was consistently found in both contexts that the higher the pressure and competencies, the higher the plagiarism. Similarly, it was consistently found that opportunities and rationalization do not affect the level of plagiarism. Meanwhile, slightly different results were found regarding students’ understanding of artificial intelligence. The existence of artificial intelligence was perceived differently by students in Indonesia and Malaysia. However, these differences in perception did not have an impact when understanding of artificial intelligence interacted with rationalization, as this interaction consistently strengthened the tendency to plagiarize in both contexts.

Consistent with the research findings, higher education institutions must assist students in effectively coping with the stress they experience, particularly the stress arising from peer competition in publishing. In addition to this, institutions of higher education must engage in deliberations on the ethical dimensions of artificial intelligence. The inevitable advancement of artificial intelligence is an unavoidable phenomenon. Hence, higher education institutions must be proactive, open, and forward-thinking to effectively respond to the ever-evolving and dynamic world of artificial intelligence. Following this perspective, institutions of higher education must establish a conducive atmosphere that fosters academic integrity, while also proactively addressing the potential obstacles presented by artificial intelligence. Accordingly, investing in cutting-edge technology that upholds academic integrity is deemed vital, such as the frequent updates of plagiarism detection software.

5. Conclusion

This study succeeded in finding empirical evidence related to several factors that contribute to the occurrence of plagiarism among postgraduate students in accounting and business. These factors consist of pressure, rationalization, competencies, and understanding of artificial intelligence. The higher the academic pressure perceived by students, the higher the student’s confidence in their capabilities and skills, and the higher the student’s level of understanding of artificial intelligence, the higher the student’s tendency to plagiarize. Likewise, when students justify cheating more, the more students are involved in plagiarism. However, no evidence was found to suggest that as the level of opportunity increases, so does the prevalence of plagiarism. Furthermore, this study discovered evidence that the positive influence of rationalization on plagiarism increases with the level of understanding a student has regarding artificial intelligence. Nevertheless, an understanding of artificial intelligence fails to strengthen the impact of opportunity, pressure, and skill on instances of plagiarism.

The findings of this study highlight several implications for both theory and practice. Firstly, this study enhances our understanding of the factors contributing to plagiarism among postgraduate students in accounting and business by incorporating artificial intelligence as a dimension into Cressey’s (1953) well-known fraud diamond framework. Recognizing artificial intelligence as a determinant of plagiarism offers new insights into its potential negative influence on students’ attitudes towards plagiarism if not effectively monitored and controlled.

Secondly, apart from looking into the direct links between pressure, opportunity, rationalization, competencies, understanding of artificial intelligence, and plagiarism, this study provides new insights into how understanding artificial intelligence can strengthen the relationship between rationalization and plagiarism. Thirdly, this research adds new empirical evidence to the existing literature, particularly from the perspective of emerging countries.

Given the widespread issue of academic plagiarism, this study recommends that universities implement academic intervention tools, such as text-matching software like Turnitin and other similar programs, to detect similarities between text submissions (Heckler et al., Citation2013; Scheg, Citation2013). Additionally, universities should adopt bespoke English for Academic Purposes (EAP) programs, as proposed by Perkins et al. (Citation2020), to address and reduce plagiarism and detect instances of cheating.

However, the present study is subject to significant limitations due to its cross-sectional methodology and reliance on single-source data. This particular design possesses the capacity to give rise to issues related to Common Method Bias. Nevertheless, this study has conducted full collinearity testing, and the results indicate that the issue of single-source data bias is not significant. In addition, the questionnaire prompts students to indicate the frequency with which they engage in acts that are indicative of plagiarism. The possibility for self-incrimination exists within the responses provided by students, thereby suggesting that the reported frequency may be lower than the actual occurrence. Nevertheless, the survey administration technique employed in this study was specifically modified to guarantee the preservation of respondent anonymity and the confidentiality of all submitted responses.

oaed_a_2375077_sm2263.docx

Download MS Word (47.1 KB)Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude to the Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia, and to the Faculty of Business and Economics, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia for supporting this research collaboration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available on request from the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sari Atmini

Sari Atmini (corresponding author): A lecturer at the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia. Obtained a doctorate from Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. Research interest: Financial Accounting.

Ruzita Jusoh

Ruzita Jusoh: A professor at the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Business and Economics, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Research interest: Management Accounting.

Arum Prastiwi

Arum Prastiwi: A lecturer at the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia. Obtained a doctorate from Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia. Research interest: Financial Accounting and Corporate Social Responsibility.

Setyo Tri Wahyudi

Setyo Tri Wahyudi: A professor at the Department of Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia. Research interest: Business Statistics.

Kurniasari Novi Hardanti

Kurniasari Novi Hardanti: A doctorate student at the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia.

Nadafajar Nurmani’ah Widiarti

Nadafajar Nurmani’ah Widiarti: Graduated from Master Study Program in Accounting, Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia.

References

- Ahmadi, A. (2014). Plagiarism in the academic context: A study of Iranian EFL learners. Research Ethics, 10(3), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016113488859

- Ahsan, K., Akbar, S., & Kam, B. (2022). Contract cheating in higher education: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Assessment Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(4), 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1931660

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al Serhan, O., Houjeir, R., & Aldhaheri, M. (2022). Academic dishonesty and the fraud diamond: A Study on attitudes of UAE undergraduate business students during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(10), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.10.5

- Al Shbail, M. O., Esra’a, B., Alshurafat, H., Ananzeh, H., & Al Kurdi, B. H. (2021). Factors affecting online cheating by accounting students: the relevance of social factors and the fraud triangle model factors. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 20, 1–16.

- Alshurafat, H., Al Shbail, M. O., Hamdan, A., Al-Dmour, A., & Ensour, W. (2023). Factors affecting accounting students’ misuse of chatgpt: an application of the fraud triangle theory. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 22(2), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-04-2023-0182

- Bierstaker, J., Brink, W. D., Khatoon, S., & Thorne, L. (2024). Academic fraud and remote evaluation of accounting students: An application of the fraud triangle. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05628-9

- Burke, D. D., & Sanney, K. J. (2018). Applying the fraud triangle to higher education: Ethical implications. Journal of Legal Studies Education, 35(1), 5–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlse.12068

- Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018

- Choo, F., & Tan, K. (2008). The effect of fraud triangle factors on students’ cheating behaviors. Advances in Accounting Education: Teaching and Curriculum Innovations, 9, 205–220.

- Dehouche, N. (2021). Plagiarism in the age of massive Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT-3). Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 21, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.3354/esep00195

- Dorminey, J., Fleming, A. S., Kranacher, M.-J., & Riley, R. Jr. (2012). The evolution of fraud theory. Issues in Accounting Education, 27(2), 555–579. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-50131

- Eisa, T. A. E., Salim, N., & Alzahrani, S. (2015). Existing plagiarism detection techniques: A systematic mapping of the scholarly literature. Online Information Review, 39(3), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-12-2014-0315

- Fadersair, K., & Subagyo, S. (2019). Perilaku kecurangan akademik mahasiswa akuntansi: dimensi fraud pentagon (Studi kasus pada mahasiswa Prodi Akuntansi Ukrida). Jurnal Akuntansi Bisnis, 12(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.30813/jab.v12i2.1786

- Foltýnek, T., Meuschke, N., & Gipp, B. (2019). Academic plagiarism detection: A systematic literature review. ACM Computing Surveys, 52(6), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1145/3345317

- Golden, J., & Kohlbeck, M. (2020). Addressing cheating when using test bank questions in online classes. Journal of Accounting Education, 52, 100671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2020.100671

- Grace, K., Salvatier, J., Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Evans, O. (2018). When will AI exceed human performance? Evidence from AI experts. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 62, 729–754. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.1.11222

- Heckler, N. C., Forde, D. R., & Bryan, C. H. (2013). Using writing assignment designs to mitigate plagiarism. Teaching Sociology, 41(1), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X12461471

- Hendy, N. T., & Montargot, N. (2019). Understanding Academic dishonesty among business school students in France using the theory of planned behavior. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(1), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2018.12.003

- Husain, F. M., Al-Shaibani, G. K. S., & Mahfoodh, O. H. A. (2017). Perceptions of and attitudes toward plagiarism and factors contributing to plagiarism: A review of studies. Journal of Academic Ethics, 15(2), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9274-1

- Hutson, J. (2024). Rethinking plagiarism in the era of generative AI. Journal of Intelligent Communication, 4(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.54963/jic.v4i1.220

- Jeffrey, T. (2020). Understanding college student perceptions of artificial intelligence. Systemics. Cybernetics and Informatics, 18(2), 8–13.

- Khalid, F. M., Rauf, F. H. A., Othman, N. H., & Zain, W. N. W. M. (2020). Factors influencing academic dishonesty among accounting students. Global Business Management Research, 12(4), 701–711.

- Khasni, F. N., Keshminder, J., Chuah, S. C., & Ramayah, T. (2023). A theory of planned behaviour: Perspective on rehiring ex-offenders. Management Decision, 61(1), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2021-1051

- Köbis, N., & Mossink, L. D. (2021). Artificial intelligence versus Maya Angelou: Experimental evidence that people cannot differentiate AI-generated from human-written poetry. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106553

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G; Texas A&M International University. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

- Kumar, V., Verma, A., & Aggarwal, S. P. (2023). Reviewing academic integrity: Assessing the influence of corrective measures on adverse attitudes and plagiaristic behavior. Journal of Academic Ethics, 21(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-022-09467-z

- Mavrinac, M., Brumini, G., Bilić-Zulle, L., & Petrovecki, M. (2010). Construction and validation of attitudes toward plagiarism questionnaire. Croatian Medical Journal, 51(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2010.51.195

- Mozgovoy, M., Kakkonen, T., & Cosma, G. (2010). Automatic student plagiarism detection: Future perspectives. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 43(4), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.43.4.e

- Nurcahyono, N., & Hanum, A. N. (2023). Determinants of academic fraud behavior: The perspective of the pentagon fraud theory. Paper Read at 1st Lawang Sewu International Symposium on Humanities and Social Sciences 2022 (LEWIS 2022).

- Oktarina, D., & Ramadhan, N. S. (2023). Academic fraud behavior of accounting students in dimensions of fraud hexagon theory. Journal of Auditing, Finance, and Forensic Accounting, 11(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.21107/jaffa.v11i1.18432

- Park, C. (2003). In other (people’s) words: Plagiarism by university students–literature and lessons. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(5), 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930301677

- Perkins, M., Gezgin, U. B., & Roe, J. (2020). Reducing plagiarism through academic misconduct education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-00052-8

- Putra, I. E., Jazilah, N. I., Adishesa, M. S., Al Uyun, D., & Wiratraman, H. P. (2023). Denying the accusation of plagiarism: Power relations at play in dictating plagiarism as academic misconduct. Higher Education, 85(5), 979–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00875-z

- Ringle, C., Wende, S., & Becker, J. (2015). SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH.

- Scheg, A. G. (2013). The impact of Turnitin to the student-teacher relationship. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 2(1), 29–38.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2020). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. Wiley.

- Selemani, A., Chawinga, W. D., & Dube, G. (2018). Why do postgraduate students commit plagiarism? An empirical study. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0029-6

- Smith, K., Emerson, D., Haight, T., & Wood, B. (2023). An examination of online cheating among business students through the lens of the Dark Triad and Fraud Diamond. Ethics & Behavior, 33(6), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2022.2104281

- Smith, K. J., Emerson, D. J., & Mauldin, S. (2021). Online cheating at the intersection of the dark triad and fraud diamond. Journal of Accounting Education, 57, 100753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2021.100753

- Specht, D. (2019). Reading, desk research, taking notes and plagiarism. In Media and communications study skills student guide (pp. 27–45). The University Of Westminster Press.

- Sullivan, M., Kelly, A., & McLaughlan, P. (2023). ChatGPT in higher education: Considerations for academic integrity and student learning. Journal of Applied Learning Teaching, 6(1)

- Theotama, G., Waskita, Y. D., & Hapsari, A. N. S. (2023). Fraud hexagon in the motives to commit academic fraud. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis, 26(1), 195–220. https://doi.org/10.24914/jeb.v26i1.7395

- Umar, H., Partahi, D., & Purba, R. B. (2020). Fraud diamond analysis in detecting fraudulent financial report. International Journal of Scientific Technology Research, 9(3), 6638–6646.

- Utami, D. P. W., & Purnamasari, D. I. (2021). The impact of ethics and fraud pentagon theory on academic fraud behavior. Journal of Business Information Systems, 3(1), 49–59.

- Uzun, A. M., & Kilis, S. (2020). Investigating antecedents of plagiarism using extended theory of planned behavior. Computers & Education, 144, 103700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103700

- Vousinas, G. L. (2019). Advancing theory of fraud: The SCORE model. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(1), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-12-2017-0128

- Walker, J. (1998). Student plagiarism in universities: What are we doing about it? Higher Education Research Development, 17(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436980170105

- Wardani, D. K., & Putri, A. T. (2023). The fraud triangle of accounting student’s academic cheating. Proceeding International Conference on Accounting and Finance (pp. 32–39). https://journal.uii.ac.id/inCAF/article/view/27412

- Wolfe, D. T., & Hermanson, D. R. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. CPA Journal, 74(12), 38–42.