Abstract

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Islamic Republic of Iran remained a member of the United Nations and except for three core instruments, i.e. ICERD, ICCPR and ICESCR, that had already been signed during the time of the Shah, the Iranian regime signed two further instruments, i.e. CRC and CRPD, though this time with reservations. Throughout the years, the Iranian delegation has met with relevant UN mechanisms to discuss human rights issues in Iran in relation to each instrument. What has transpired from the dialogues, however, is a change of the use of language and position by the delegation in defence of the regime. The analysis demonstrates resistances, ambiguities and dichotomies in the responses of the delegation to accusations of human rights violations but also an adaptation of a human rights language over the years. The analyses carried out in this paper are based on the summary reports, concluding observations, State reports, the list of issues and their replies, reports of independent Special Procedures and reports of civil society organizations, as pertaining to each convention signed and ratified by Iran and as are available in electronic form.

Public Interest Statement

In recent decades, Iran has become a key political player in the world. At the same time, the Iranian government’s violations of the human right have received increasing attention by the United Nations (UN), an entity tasked to promote human rights principles and to prevent human rights violations by states. To monitor the human rights situation in each country, the UN requires the states to periodically submit reports of their activities based on the international human rights treaties they have committed to. Subsequently, a dialogue is initiated between the UN and the member states, intended to promote the human rights principles and to improve inadequacies. This article presents an analysis of the electronically available reports submitted by the Islamic Republic of Iran and the ensuing dialogues with the UN. The analysis of these records reveals that over the years Iran has adapted its responses to ease the dialogue with the UN instead of truly improving the human rights situation in the country.

1. Introduction

On 24 October 1945, the same day the United Nations (UN) officially came into existence once the UN Charter was ratified 1 by a majority of signatories (UN, Citation2015a), 2 Iran was admitted into the UN. The admittance of Iran to the UN took place during the reign of Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi (from 16 September 1941 until his overthrow in 1979). After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, despite the intensification and systematization of human rights violations and despite the creation of ideological antipathy towards the West, Iran remained a member state to the UN. Even though the UN Charter does not provide any means of withdrawal from the United Nations for the states, the Islamic Republic of Iran has neither attempted nor proposed to withdraw from the UN like a few other states such as Indonesia (Schwelb, Citation1967), the US 3 and Philippines (McKirdy, Citation2016) who have attempted and proposed to withdraw from the UN in the past. Similarly, Iran has not been expelled from the UN by the General Assembly as reserved in Articles 5 4 and 6 5 of the Charter despite Iran’s persistent violation of the human rights principles. Although no state has been expelled or suspended from the UN since its inception, under other articles, a few states such as the People’s Republic of China (Bolton, Citation2000), South Africa (Office of Publica Information, Citation1974) and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (UN General Assembly, Citation1992) have been suspended or expelled from participating in UN activities. This is of importance since it shows that the Islamic Republic of Iran has willingly committed itself to the provisions of and the principles contained in the ratified treaties and the international human rights law. This must, therefore, be kept in mind throughout the discussion in this paper, which looks into Iran’s commitment to the principle of the universality of human rights. This paper also examines and analyses the dialogues between the Iranian delegation and the relevant treaty-based bodies of the UN over the years.

This article is based on the treaties signed by Iran, both before and after the 1979 Revolution (Helfer, Citation2012) 6 (UN, Citation2015a). Table shows all the functioning treaty-based bodies relevant to Iran. The analyses carried out in this paper are based on the summary reports, concluding observations, State reports, the list of issues and their replies, reports of independent Special Procedures and reports of civil society organizations, as pertaining to each convention signed and ratified by Iran and as are available in electronic form. Not having all documents readily available is one of the limitations of this article. Another limitation is the wide gap between the Islamic Republic’s submission of the periodic reports. There are, however, sufficient accessible documents to gather outstanding data, to analyse and to draw conclusions.

Table 1. Different human rights monitoring mechanisms of the United Nations system based on Iran’s commitment to the relevant treaties

2. UN treaty-based bodies: Dialogue

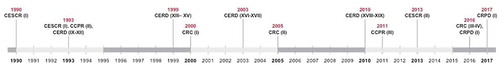

As a UN member, Iran has signed and ratified only five out of ten 7 core international human rights instruments. Figure shows the years when the periodic reports of the Islamic Republic were electronically made available and reviewed under relevant UN human rights instruments. This paper is structured based on this timeline. Prior to delving into the Islamic Republic’s commitment to international norms and considering Iran’s on-going dialogue with each relevant treaty-based body at the UN, however, it is worth discussing the nature of the political system in Iran and its expressions. The next two sections are dedicated to this task. The subsequent section will cover the historical contingency of each of the five core international instruments. It will also look into the reasons and possible circumstances around which Iran committed itself to them.

3. Hybridity of the post-1979 regime

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, a hybrid or a contemporary authoritarian regime was born. According to David Lewis, unlike some authoritarian states such as North Korea and Turkmenistan that “outlaw almost all types of non-state associations”, Iran, as a contemporary authoritarian state, permits “the existence of formally autonomous organizations engaging in activities beyond the direct control of the state”, “while resisting any trajectory towards democratization” (Lewis, Citation2013). During the regime change, both the necessary transition and transformation for the establishment of a sustainable democracy failed. Heidrun Zinecker states that in order for transition to go through a full cycle, policies that “guarantee the political participation of the lower classes by the redistribution of the economic factors of production in their favour in order to overcome marginality” need to be enacted (Zinecker, Citation2009). The other sign of a successful transition to democracy is the complete socioeconomic transformation, which should ideally change from “rent economy (with marginality) to a market economy (without marginality)”. 8 The inability of the state to complete full cycles of transformation and transition after the revolution, caused the Iranian regime to land on a “grey area between authoritarianism and democracy” (Zinecker, Citation2009).

Koesel states that religious entities are usually influential in “mobilizing against authoritarian rule”. However, the religious entity that mobilized the 1979 Revolution in Iran overthrew the Shah but replaced “one form of authoritarianism with another” (Karrie, Citation2014) hence making the new regime, which is “distinguished by its unique clericalism”, a hybrid regime (Arjomand, Citation2009). The uniqueness of the Iranian regime is owed to the members of the parliament and the President who are elected but are “subordinated to clerical authority” and to a “theocratic republic” which is a “system of collective rule by clerical assemblies or councils under clerical ruler”, all of whom are under the shadow of one Supreme Leader (Arjomand, Citation2009). With the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, a new constitution was drafted. This constitution was later on amended to give the Supreme Leader an “unlimited power” (Khiabany, Citation2010), which has been a surviving factor of the regime all these years. In general, the Iranian regime and the Islamic ideology it has put in place, are an “incoherent mixture of various ideologies” with the aim to create a pure Islamic state with citizens fully obedient to Islam, to perpetuate “clerical rule” in that country (Parvin & Vaziri, Citation1992, p. 90) and to create an “ideal identity”, an “ideal society” and an “ideal state”. The ideologies that would conform to such idealisms based on Sharia law were constructed in a hybrid climate, consequently propelling every expression emanating from the regime towards ambiguity and dichotomy. This has forced the nation into facing an identity crisis (Papanek, Citation1994).

4. Expressions of hybridity: Ambiguity and dichotomy

The expressions of hybridity in the fabric of the Islamic Republic of Iran are many. This section, however, limits the discussion to human rights within the Iranian Constitution since it bears the fundamental principles of the regime’s governance. In its Constitution, the Iranian regime has bestowed to all Iranians a variety of fundamental universal rights, such as freedom of speech and assembly, freedom of religion, right to education, social security, and a fair trial, just to name a few. However, by placing these rights into the Constitution, a dichotomy has been created between the notions of popular sovereignty and the sovereignty of God. On the one hand, Articles 1 and 2 of the Constitution confer “longstanding belief” by the Iranian people in the “sovereignty of truth and Qur’anic justice” and sovereignty of God while on the other, Article 6 demands that the “affairs of the country must be administered on the basis of public opinion expressed by the means of elections … or by means of referenda in matters specific in other articles of this Constitution” (IRI, Citation1979). This is why the Iranian Constitution has also been known to comprise “hybrid of authoritarian, theocratic and democratic elements” (Fukuyama, Citation2009).

Another example of the expression of hybridity in the form of ambiguity and dichotomy is with regards to the Islamic belief that attributes the “ultimate sovereignty” to God (Tamadonfar, Citation2001). In Article 56 (Chapter V) of the Constitution, the sovereignty of God is explicitly recognized. It specifies that “[a]bsolute sovereignty over the world and man belongs to God, and it is He Who has made man master of his own social destiny. No one can deprive man of this divine right, nor subordinate it to the vested interests of a particular individual or group” (IRI, Citation1979). The regime has exercised the opposite of this very same article of the Constitution and “asserts that the sovereignty of God on earth is exercised by his deputies, the Shi’i clergy” (Tamadonfar, Citation2001). It is on this basis that Khomeini established his doctrine of velayat-e faqih, translated as “rule of the supreme jurist” (Khiabany & Sreberny, Citation2001). Through the creation of ideological ambiguities and dichotomies, the Iranian regime has “attempted to legitimate the on-going suppression of fundamental rights in the Islamic Republic” (Schirazi, Citation1997).

Parvin and Vaziri believe that the dichotomy is in fact between the Iranian regime’s “Islamic ideology” and “true Islamic policies and actions”. In their view, the regime’s Islamic ideology attempts to bring about an “overall unity of the populace under Islam”. The clergy has made an effort to “achieve cultural hegemony”, a process that enforces a certain direction on social life by the ruling group on the ruled (Lears, Citation1985), but to no avail. They have only succeeded in achieving a cultural hegemony amongst “the least educated, most economically disadvantaged, and most culturally impoverished citizens” (Parvin & Vaziri, Citation1992, pp. 86–87). For everyone else who cannot leave Iran, “compliance with Islamic rule and the clerical cultural hegemony” has been “involuntary”, “transitory” and “volatile” (Parvin & Vaziri, Citation1992, p. 87).

In response to Iran’s defeat in an attempt to obtain a seat on the UN Human Rights Council in 2006, Hillel Neuer, Executive Director of UN Watch, 9 stated that “Iran’s domestic and foreign policy is hostile to the very principles of human dignity and the principles of the universal declaration of human rights” (IRIN, Citation2006). In general, by making the law ambiguous and using phrases such as “except in cases sanctioned by law”, “exception will be specified by law”, “except as provided by law” or “except in cases provided by law” etc., the Iranian regime has created a situation where it is left with a free hand to violate its own domestic laws whenever it suits it but is able to simultaneously show the international community that its domestic laws are in conformity with the international human rights norms.

5. Historical contingency: Commitment to international rights norms

Table shows three of the five core instruments that Iran is committed to but which were signed and ratified at the time of the Pahlavi regime. ICERD was signed in March 1967 exactly in the month and the year when the Kurdish revolt erupted in Iran. The Kurdish struggle for independence and autonomy has been ongoing in the Middle East, most specifically in Iran, Turkey and Iraq where the Kurds are primarily concentrated. The Kurds have been one of the largest ethnic groups against which “cultural and sociopolitical discrimination” have been aimed. The uneven social, economic and political developments, which resulted from the Shah’s modernization programs and the introduction of the White Revolution of 1963–1977 further marginalized the Kurds (Entessar, Citation2010). The eruption of the Kurdish revolt did not produce a good image of Iran, at the time when the Shah was seeking the support of the Western world especially that of the United States, which was one of the five permanent members of United Nations Security Council. During his reign, the Shah aimed to follow “centuries of diplomatic tradition and universally-accepted tenets of international law” and to build bridges with the international community (Carolyn, Citation2001). Therefore, the Kurdish revolt may have been a key event behind the adoption of ICERD. It might also have been a strong force behind Pahlavi regime’s signing (1968) and ratifying (1975) of the ICCPR and ICESCR, both of which took place during Pahlavi’s introduction of the White Revolution between 1963 and 1977. The Shah wanted to “prove himself a reformer” (Summitt, Citation2004); hence, he signed and ratified all the aforementioned treaties with no reservations or declarations.

Table 2. International human rights instruments signed and ratified during Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi’s reign

After the 1979 revolution, not only did Iran not withdraw from the aforementioned conventions, it also adopted two further ones, as illustrated in Table . The Islamic Republic of Iran signed CRC in 1991 and ratified it in 1994. The circumstances around the adoption of this convention could have been due to reports that began to emerge highlighting the sharp increase in juvenile executions in Iran since the 1990s (Amnesty International, Citation2015a). However, upon signature and ratification of this convention, the Islamic Republic of Iran made a reservation, which will be discussed later. The fifth Convention, CRPD, was acceded 10 in 2009 but Iran also made a declaration to this Convention more specifically to its Article 46. This declaration will also be covered in a later section. The accession of this Convention without a signature took place only five months after the controversial presidential election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, which led to the Iranian Green Movement 11 that was prolonged well into 2010. Whether the Movement was a precursor to the rapid accession (without signature) of CRPD or whether the accession of CRPD was a distraction to the regime’s crackdown on protests remains a supposition at best.

Table 3. International human rights instruments signed and ratified after the 1979 Islamic revolution

6. 1990

6.1. ICESCR (reporting cycle I)

Even though since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, various treaty-based bodies have reviewed Iran’s human rights performance, the only records made available electronically are those starting from the year 1990 onwards. In 1990, the CESCR examined Iran’s state report during the first reporting cycle. One of the main claims that Iran makes in this report is that “there is no form of discrimination in the educational system of the Islamic Republic of Iran which could lead to the unequal accessibility of different social groups to education”. 12 This is while, according to Amnesty International, since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, discrimination against certain minority groups, more severely against the Baha’is, were sanctioned and legally supported by the authorities as high up as the Supreme Leader. The discriminatory practices have barred the Baha’is from “accessing higher education in universities and other institutions” (Amnesty International, Citation2014).

Based on a report by Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre, in the very same year in which the committee examined Iran’s State report, Ayatollah Khamenei instructed President Rafsanjani to address “the Baha’i Question”. The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution then prepared a “confidential” 13 memorandum to which Khamenei added his signature. It instructs the government’s “dealing with them [the Baha’is]” to be “in such a way that their progress and development are blocked”. More specifically on education, it is stated in the memorandum that the Baha’is “must be expelled from universities, either in the admission process or during the course of their studies, once it becomes known that they are Baha’is” (IHRDC, Citation2006). This is while prior to 2003, university entrance exam forms included “a declaration of religion” and no one was permitted to leave it blank (BIC, Citation2016a). Later in that year, possibly due to international pressure, “the declaration of religious affiliation on the application for the national university entrance examination” was removed. However, university entry in Iran has a two-tier admission process. Therefore, those who can now write the entrance exams without discrimination face the same problem when it comes to registration at the university of their choice (BIC, Citation2015). Other groups including Ahl-e Haq, Sufis, and Sunni Muslims also face restrictions, though not to the same extent as the Baha’is. However, such restrictions limit the enjoyment of their right to education (Amnesty International, Citation2014). In its concluding observation, the committee also showed concern over the educational situation of ethnic groups such as Armenians and Kurds in addition to the right to education of refugee groups. 14 Since the 1990s, for example, when Iran changed its strategy towards refugees in order to encourage mass repatriation, the Afghan refugees were denied access to education and other essential services such as healthcare (Small Media, Citation2015). It was only in 2015 when the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, issued an order (Iranian Diplomacy, Citation2015) permitting all Afghan children to attend schools regardless of their residency status (Al-Monitor, Citation2015). Two years onwards from the date of the order, however, a research showed that, instead of attending schools, Afghan children are “being recruited to fight in Syria”. This is even more troubling as the “government has proposed offering incentives such as a path to citizenship for families of foreign fighters who die, become injured, or are taken captive during ‘military missions’” (HRW, Citation2017).

Based on the concluding observations, the committee also showed great concern over the rate of enrolment in rural areas, which lags behind compared to urban areas in addition to women and their access to education without discrimination. While it is not clear in what language or tone the Iranian delegation defended its position since the summary reports are not available, it is clear from the concluding observations that excuses were made as to why the rate of enrolment in rural areas lagged behind compared to urban areas in order to absolve the government of its responsibilities. The delegation blamed the discrepancy on “drop-out rate, the lack of qualified teachers, the consequences of the war, and the destruction of school-building by two earthquakes”. However, research shows that although in the 1990s, Iran experienced a decline in poverty, yet according to Hayati et al., “the overall figures are the result of a sharp fall in urban poverty offsetting an increase in rural poverty”. Hayati et al. accorded this to “high population growth rate; low labour productivity level and growth rates; … inconsistent socio-economic policy, over-reliance on particular sectors—such as oil and a lack of appropriate planning” (Karami, Hayati, & Slee, Citation2006). It must be noted that the delegation’s claim of the lack of qualified teachers also goes back to state policy. At the beginning of the 1979 Revolution when the Bazargan ministry fell, the Revolutionary Council assumed the role of the government on the Supreme Leader’s behest. The then Minister of Education, Muhammad Ali Raja’i, appointed by this Council “began a purge of all Baha’is in the educational system”. According to Douglas Martin, “in an edict”, the Baha’i teachers were not only discharged but were also held “responsible for repayment of all salaries they had previously received” (Martin, Citation1984).

The Iranian delegation also claimed that “in no way were women considered second-class citizens”. 15 This is while the Iranian regime has refused to sign and ratify the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) to this day. According to many non-governmental organizations such as Human Rights Watch, severe discrimination exists in Iran’s laws and policies against women (Begum, Citation2015). For instance, Iranian women are barred from entering stadiums. They need permission from their husbands in order to leave the country; they are forced to wear hijab; their children and the guardianship of the children are given to the male side of the family, either to the father or to the paternal grandfather (HRW, Citation2015). In this 1990 dialogue with the committee, the Iranian delegation portrays Iran’s human rights problems regarding women, ethnic and religious minorities to be non-existent and the human rights issues creating discrepancies between more affluent groups and those living under less fortunate circumstances to be no fault of the government. This is while even the minorities recognized by the Iranian regime are not immune from human rights violations. For instance, the activities of those belonging to religious minorities such as Christianity, which is recognized in Article 13 of the Iranian Constitution along with Zoroastrianism and Judaism, are closely monitored by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance 16 and the Ministry of Intelligence and Security. 17 Proselytizing is prohibited and incurs death penalty and those Muslims who convert to Christianity, or any other religion, are also considered apostates and may face death penalty (United States Department of State, Citation2014). Iran’s position in 1990, therefore, was a complete denial of human rights violations despite the clear discriminatory policies and the overwhelming cases.

7. 1993

In 1993, three committees namely CCPR, CESCR and CERD examined Iran’s periodic reports, which were submitted to relevant treaty bodies as a legal obligation of the State. While in 1990, the states were required to report on three separate sets of articles at a time, after 1990, they were no longer required to report in such manner. Instead, they had to report on the whole Convention. Therefore, the 1993 reporting cycle for CESCR was again considered the initial periodic cycle.

7.1. ICESCR (reporting cycle I)

7.1.1. Resistance

There were many evident resistances on the part of the Iranian delegation during this initial periodic review. One was regarding the committee members’ statements based on documentation received, which illustrated that the Iranian authorities were committing massive violations of human rights 18 to which the Iranian delegation held that the “subject had no place in the Committee’s work”. The delegation felt that the Committee had “a primarily legal and not a political task and it was its duty to be precise in its work”.

Also based on reports and evidence made available to the Committee by non-governmental organizations and the Special Rapporteur, 19 the Committee confirmed that there “had been practically no progress in ensuring greater respect for the human rights of religious communities” 20 in Iran. Not acknowledging the independent and non-partisan nature of the reports, the delegation took exception to the Committee’s conclusion stating that “although it was true that the Islamic Republic of Iran was accused of massive human rights violations by a number of countries which had been wielding some measure of political hegemony since the end of the cold war, it was not accurate to speak of a worldwide consensus, since some States did not agree with those accusations and others had no opinion on the matter”. 21 The Committee had to then remind the Iranian delegation that the Committee members functioned as independent experts and any “questions asked were precise and related to specific violations of particular human rights”. The Committee requested from the delegation to give “precise and specific” responses. 22

Another form of resistance is the imposition of blame culture. In response to the Committee’s comments that the Iranian regime had violated the human rights of the Iranians for over the past 14 years, the delegation blamed the situation on the war, which was “initiated by an aggressor”. 23 The delegation claimed that this aggressor “had been supported by those very States that accused [Iran] of human rights violations”. 24 The Committee pointed out that “[t]he fact that the Islamic Republic of Iran might have been subjected to an act of aggression did not entitle it to violate the rights of individuals or of minorities”. 25 The Committee also felt that the Iranian delegation denied the human rights violations mentioned in the report prepared by Reynaldo Galindo Pohl, the Special Representative of the Commission on Human Rights from 1986 till 1995 26 rather than “providing any specific response” to questions. 27 The Iranian delegation responded that when Reynaldo Galindo Pohl visited the country, he had observed that, “many allegations against [Iran] had been exaggerated”. Due to this observation, he was accused of cooperating with Iran and “concealing alleged human rights violations”. 28 That is why the Special Rapporteur had to change the tone of his report. In such a short span of time from 1990 to 1993, the Iranian delegation somewhat changed its tone and took a few other approaches to its responses. It refused to address the human rights violations under various pretexts such as the denial of their existence, their irrelevance to the work of the Committee and the intrusion of external elements. By doing so, the Iranian delegation undermined the work of the Committee, derailed from topic, introduced irrelevant involvement of other states for what is an internal obligation of the state and generally avoided responding to the specific questions of the Committee with regards to the human rights situation in the country.

Such expressions of hybridity point to the confusing laws and regulations of the Islamic Republic, which lack one coherent policy. One specific theme, which is dominantly raised during the dialogues and which shows the emission of the expression of hybridity outside the Iranian borders is the case of Salman Rushdie.

7.1.2. Hybridity

During the review under discussion, the Committee repeatedly questioned the Iranian delegation regarding a fatwa issued by Khomeini ordering Muslims to kill Salman Rushdie who authored the novel The Satanic Verses. What transpired from the dialogue was that the Iranian delegation felt this matter had “nothing to do with the internal law of the Islamic Republic of Iran and with its commitment to implement the Covenant”. 29 The Iranian delegation further explained that this “was a religious fatwa decreed according to criteria that had nothing to do with Iranian domestic law”. 30 This is significant since, in this instant, the delegation tried to portray the government and the domestic laws as independent of the Supreme Leader when in reality the Supreme leader controls and dominates every aspect of life in the country. The Committee, therefore, concluded that the Iranian government was only “making a technical presentation to the Committee on the application of the Covenant, while at the same time maintaining that on the cultural side there was another system with its own coordinates and terms of reference”. The case of Rushdie, according to the Committee, proves that “over and above the State there [is] another system with its own rules”. 31

Challenging the Iranian delegation’s stance on the religious fatwa, the Committee referred to the information provided by the League for the Defence of Human Rights in Iran, which stated “Under the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, fundamental rights can only be exercised strictly within the limits of Islamic rules as defined in the Constitution itself by the Supreme Guide”. In other words, the “latter takes precedence over all powers, judicial, executive and legislative, and can at any time issue a fatwa, which then takes on the force of a law applicable by the various State organs, or abrogate a law adopted by the Parliament which is judged to be contrary to Islamic principles”. 32 The Committee, therefore, found that the fatwa did not only “belong to the religious domain but also bound the Government”. 33 The delegates, of course, denied this fact insisting, “the Government was not bound by a fatwa”. 34

The Salman Rushdie case is only one example that demonstrates the expression of the hybridity of the Islamic Republic of Iran in the international setting. Even though the review took place in 1993, the events surrounding the fatwa against Rushdie took place in 1988, coincidentally when the Iran-Iraq war ended. This is significant because one of the slogans of the Supreme Leader of the time, Khomeini, which rallied the people for eight long years, counted for heavy losses and had profound religious connotations for Muslims was “the path to Quds goes through Karbala”. This implied that the Iranian troops should liberate Israel first by conquering Iraq on their way to Jerusalem (Asadi, Citation2011). In August 1987, however, Khomeini was forced to succumb to a ceasefire by formally accepting the Security Council Resolution 598 in 1988. The timing of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, also based on religious grounds, seems to suggest a deliberate diversion from an embarrassing defeat from a charismatic leader who thought of the decision to accept the ceasefire as being “more deadly than drinking from a poisoned chalice”. All these events may have played a role in the way the Iranian delegation, who took an ideological approach towards foreign policy, responded to the Committee. According to Soltani and Ekhtiari Amiri, between 1981 and 1989, an ideological approach was dominantly taken towards foreign policy, which was heavily based on “Islamic principles and assumptions”. It was during this period that the fatwa was issued. Iran’s initial report post-1990, however, was due in June 1990 and Iran submitted its report in January 1992. 35 During this period, meaning the period between 1989 and 1997, a pragmatist approach was taken where Iran accepted to “adapt itself with realities of international policies”. It “declared that it would respect international regularities and organizations” (Soltani & Ekhtiari Amiri, Citation2010). It is, therefore, interesting how the devoted servants of the regime, more specifically the subordinates of the Supreme Leader, recant the obligation to follow his orders for the sake of appearing in line with the policies of the international community. This may be the start of an altogether different approach to the dialogue between Iran and the UN Committees. It could also be the beginning of the adaptation of a language more in line with the international human rights norms.

7.2. ICCPR (reporting cycle II)

7.2.1. Sovereignty of the Quran and popular sovereignty

One of the expressions of hybridity in the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran is the dichotomy that has been created between the notions of popular sovereignty and the sovereignty of God. On the one hand, Articles 1 and 2 of the Constitution confer “longstanding belief” by the Iranian people in the “sovereignty of truth and Qur’anic justice” and sovereignty of God while on the other, Article 6 demands that the “affairs of the country must be administered on the basis of public opinion expressed by the means of elections … or by means of referenda in matters specific in other articles of this Constitution” (IRI, Citation1979).

In one instance, speaking on behalf of all Muslims, the Iranian delegation asserted that they all believe “that sovereignty over the entire world [is] exercised only by God” and that the monotheism practiced in Iran is “in no way in conflict with the principles of human rights”. 36 The Iranian delegation further maintained, “the popular revolution that had taken place in Iran was the product of many years of struggle. The people had expressed their will and set up a State based on Islamic principles. The majority of the population had approved the Constitution and was satisfied with it. The Government derived its legitimacy from the expression of the popular will”. 37 Through this statement, the Iranian delegation portrays the Islamic government to be a popular choice, yet, in a different place, it states, “Society and the social order must be governed by Islamic principles, which could not be changed”. 38 This statement plus the political system put in place, as will be discussed later, do not allow for the public will to be any different from that of the state.

The dichotomy between what the Iranian delegation tries to portray to the international community and what actually takes place on the ground in relation to popular sovereignty and sovereignty of God is further strengthened by the fact that there are laws in place on crimes against Divine Will, which as the Committee found are “vague” and “very broad”. 39 This is while, by the delegation’s own admission, “submission to God’s commands must be voluntary: for another human being to obtain such submission by force would be contrary to the Divine teachings”. 40 The Committee, therefore, found the application of the domestic law in Iran lacking “transparency” and “predictability” hence not compatible with the provisions of the Covenant. 41 Here, while the denial of human rights violations continue, the dialogue gives the impression that since the Islamic government is a popular choice, its actions, whether they are in violation of human rights or not, are endorsed by the people. One added element to the dialogue, which has been lacking thus far, is the introduction of God’s will, which is above and beyond any earthly power and the Islamic Republic has taken it upon itself to be its executer. The fact that the crimes against the Divine Will are vague and broad and that God’s sovereignty is dichotomously intertwined with popular sovereignty attests to the regime’s lack of regard for the people, their intellect and spiritual capacities. By presenting God’s will and the voluntary submission to his commands as evidence to the regime’s respect for human rights, no room is left for a more realistic dialogue between the representatives of the head of the state, whose responsibility is to set realistic goals and to execute them, and an international organization, whose job is to monitor factual human rights situation in the country.

7.2.2. Ne plus ultra doctrine

Despite all the ambiguities and dichotomies that stand out in the Iranian delegation’s portrayal of domestic norms and the delegation’s adamant citation of the Iranian law for the purpose of demonstrating conformity with the Covenant, the Islamic law seems to prevail over the Covenant. 42 In other words, shariah law is the ne plus ultra of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s governance. Ne plus ultra is defined as “the highest point capable of being reached or attained” (Fellmeth & Horwitz, Citation2009).

The lack of transparency and predictability of the application of domestic law forced the Committee to question the actual application of the Covenant into the Iranian legislation. The Committee saw Iran’s application of the Covenant as inadequate, which was “principally due to policy decisions at the highest levels”. 43 The delegation argued that there were many people in Iran with “various traditions”, yet the “unifying element for many centuries” has been Islam. The delegation noted that it could be “argued that each State party should simply apply [the Covenant’s] provisions to the letter” but gave the notion that it is the people of Iran who were “not satisfied with the rigid application of human rights instruments and [who] wanted account taken of their traditions, culture and religious context in order to evaluate the human rights situation in the country”. 44 The delegation stated that in order to meet this popular demand, the Islamic countries had elaborated their own Islamic Declaration of Human Rights in order to address the aforementioned issues, which “in the view of Islamic countries” were not addressed in the UDHR and the Covenant. 45 The Committee felt that the “predominance of the shariah must cause problems for a State party which had signed and ratified the Covenant without entering any reservations, as was the case with Iran”. The Iranian delegation gave the impression that “the State party actually had mental reservations about the implementation of the covenant, since it seemed to find it normal to impose restrictions or to fail to enforce certain rights if the shariah so required”. 46

The Committee found that the ambiguous references to shariah law “predominated in the Iranian legal system”. Therefore, the “law was not really transparent and predictable and it could not be said what rule would be applied in a particular case. Consequently, it was not easy to determine whether or not there was incompatibility”. 47 There was an impression that “although international treaties had the force of law, they were nevertheless subject to a higher law”. 48 Elsewhere in the report, the Committee conveyed that it seemed “the implementation of the Covenant was causing problems for Iran, which very frequently invoked the argument that the Covenant was in conflict with the precepts of Islam”. Considering Iran is a signatory to the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, the Committee found that shariah law seemed to be the “supreme standard” and “took precedence over all international treaties or instruments, and even over the Iranian Constitution”. 49 This portrayed to the Committee that Iran was “adopting a ne plus ultra doctrine and implementing the Covenant up to a certain level only”. 50

Even though Iran had declared respect for “international regularities and organizations”, according to Soltani and Ekhtiari Amiri, taking a pragmatist approach between 1989 and 1997, Iran’s foreign policy was “based on geo-political necessities” during this period. Nazila Ghanea-Hercock argues that the UN Sub-Commissions comprise independent experts and not governments (Ghanea-Hercock, 2002). Therefore, Iran’s pragmatist approach did not necessarily apply to UN mechanisms directly. Ultimately, however, the United Nations Security Council consists of permanent and non-permanent members representing various States. Hence, the delegation’s failure to provide practical information and the lack of transparency only stalled international pressure on the human rights violations in Iran especially since it took the Islamic Republic nearly ten years to appear in front of the Committee once again.

In addition, during this dialogue, instead of completely denying violation of human rights, the Iranian delegation proposes flexibility on the implementation of human rights principles and a need for religion, culture and tradition to be taken into account based on people’s desire, not the government’s. It must be noted that this stance was taken in 1993 along with the many different ones discussed thus far. The delegations appearing in front of each Committee, however, were comprised of different groups of representatives. Hence, it is not clear whether such contradictions were created on purpose to avoid the real issues or the regime was just in chaos and did not have a clear policy to carry out the dialogues with the UN Committees.

7.3. ICERD (reporting cycles IX–XII)

7.3.1. Resistances

It took the Islamic Republic of Iran eight years to appear in front of the Committee again and it is clear from the summary reports of ICERD that Iran was quite resistant in responding to any questions that the Committee put forward. To start with, the 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th State reports, 51 which were combined into one document, contained only 11 paragraphs out of which seven were quotations from the Quran, the Iranian Constitution and Iranian legal instruments. Out of the remaining four paragraphs, two indicated that Iran “[did] not accept any discrimination among various tribes and ethnic groups subjects to and within Iran” 52 either constitutionally or legally and the other two reported accession of the government to other conventions. 53 Hence, the Committee found the report to be “brief, incomplete, abstract and too general in nature”. 54 In its concluding observations, the Committee reiterated its disappointment in the insufficient manner in which the state compiled its report, which did not allow the Committee to assess how and whether the Convention was implemented. The Committee found the mere rejection of all forms of racial discrimination by the Iranian government insufficient “to prove fulfilment of its obligations under the Conventions”. 55

7.3.2. Portrayal of racial discrimination: Dichotomy & ambiguity

While reports prior to 1990 are not available in electronic format, the summary record of the 12th periodic report 56 of the Islamic Republic of Iran alludes to the fact that in its eighth periodic review, Iran had claimed, “racial discrimination in Iran did not exist”. This is while many reputable non-governmental organizations such as International Federation for Human Rights, the Iranian League for the Defence of Human Rights and Human Rights Watch have reported on “the severe discriminations against ethnic communities and religious minorities in Iran” throughout the years (FIDH & LDDHI, Citation2010; HRW, Citation1997). It is perhaps due to the continuous effort of various organizations in exposing the discriminations that the Iranian regime felt the need to produce a more convincing explanation in its 12th periodic review. The Committee found that eight years after the submission of the eighth periodic review, the Iranian regime had made an improvement by noting in its 12th periodic report that the governing body in Iran “does not accept any discrimination among various tribes and ethnic groups subjects to and within Iran”. 57 However, it also found this statement to be a mere “declaration of intent” rather than a “conclusion drawn from objective analysis”. 58

The resistance to providing accurate information and the deliverance of ambiguous statements used to portray human rights in Iran seemed to be discursive in nature meaning that they digressed from subject to subject (Oxford Dictionaries, Citationn.d.). The Iranian delegation jumped from the notion that the regime does not accept discrimination among “various tribes and ethnic groups”—hence admitting the existence of different races—to the claim that the “Iranian society [is] not multiracial”.

This is in contradiction to an earlier statement made by the Islamic Republic. In the eighth periodic state report, it was claimed that different ethnic groups such as “Kurdish, Baluchi, Arabic, Turkish and Turkomen-speaking ethnic groups” 59 exist in Iran. The defence the Iranian delegation put forward with regard to this contradiction was that the various languages spoken by different people do not claim for racial distinction; “they [are] simply Iranians who spoke different languages”. 60 The Iranian delegation depicted the ethnic groups in Iran as possessing the same rights as every other Iranian citizen and being “treated equally, or even privileged”. 61 The delegation “suggested the Committee should examine whether there was a genuine problem, or whether, on the contrary, an attempt was being made to create one” 62 thus, portraying Iran as free from human rights violations and abuses based on discrimination. This is while, when examining the main governmental policies of the Islamic Republic starting from the Iranian Constitution, as “a significant indicator of the governmental limits on the position and role of ethnic and religious minorities in Iran”, the ethnic groups have not been served with “explicit Constitutional recognition” (Ghanea-Hercock, Citation2004).

Article 19 of the Constitution states “All people of Iran, whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong, enjoy equal rights; color, race, language and the like, do not bestow any privilege” (IRI, Citation1979). According to a Human Rights Watch report (HRW, Citation1997), however, “more than 271 Iranian Kurdish villages were destroyed and depopulated between 1980 and 1992. Between July and December 1993 alone, during a major offensive against Kurdish armed groups, 113 villages were bombed” 63 as a continued effort on the part of the regime to suppress the Kurdish independent struggles. Arab culture has also been stamped out. “There is no Arabic-language newspaper dealing with domestic issues in Khuzestan … Arabic is not taught in elementary schools, and the Arabic teaching in secondary schools focuses exclusively on religious texts. The governor of Khuzestan is not an Arab, and very few high-ranking government officials are from an Arab background”. 64 Last but not least, the Baluchi grievances have also been “related to discrimination against them in the economic, educational, cultural and political fields” (Ghanea-Hercock, Citation2004). During the dialogue with the Committee, the delegates stated that the Iranian government wishes to “adopt an open stance and not to brush aside Iran’s problems”, which is, yet again, in contradiction to the point the Iranian delegation made earlier that an attempt was being made to create a problem where none existed.

8. 1999

In 1999, Iran’s submission of its 13th, 14th and 15th periodic reports based on ICERD, submitted as one document in 1998, were reviewed by the relevant Committee. They were due in 1994, 1996 and 1998 respectively.

8.1. CERD (reporting cycles XIII–XV)

There is a clear contrast in the way the Iranian delegation responds to the Committee in 1999, six years after its previous review. The delegation seemed more willing to cooperate stating that “the way had been paved towards further useful dialogue with the Committee”. The delegation found some of the Committee’s concerns new. However, instead of showing resistance, as it had done in previous years, it conveyed “the Islamic Republic would make a point of taking them into consideration in its next report”. The delegation even went further in showing its sincerity stating that it was “not only prepared to answer all questions explicitly related to racial discrimination and the Convention but, given the climate of sincerity, would also address questions that had been raised outside the Committee’s mandate, in order to allay its concerns. It would supply written replies to any left unanswered for lack of time”. 65 This change in attitude and tone of response could be attributed to the change in the political climate in Iran, which initiated with the election of Khatami as the president in 1997. Khatami, according to Soltani and Ekhtiari Amiri, took a Reformist approach and swayed Iran towards improving “its reputation in international society”. Therefore, Iran’s foreign policy changed focus to “détente, dialogue and peaceful co-existence with other countries” while promoting “values such as civil society, freedom of speech, rule of law and pluralism” within the country (Soltani & Ekhtiari Amiri, Citation2010).

8.1.1. Primacy of law: Dichotomy & ambiguity

Despite the sudden willingness to cooperate, there were still certain amounts of ambiguity and dichotomy in the delegation’s responses. One of the main concerns of the Committee, for instance, was regarding the implementation of the provisions of the Convention into the domestic law and the role of the Iranian courts. In the 13th to the 15th periodic review of Iran’s state report, 66 the Committee raised concern over Iran’s 1999 core document. In its paragraph 80, Iran states, “ratified international instruments had the force of law and were binding”. In paragraph 81, 67 however, it simply indicated that “those international instruments 68 would “influence” the legislation and implementation of laws, and that the practice of the ordinary courts and Supreme Court would “in the future” establish whether an individual could invoke provisions of international instrument in legal proceedings”. 69

In response to this discrepancy, the Iranian delegation argued that “the Convention had been approved by Parliament and that, pursuant to article 9 of the Civil Code, any duly ratified international instrument assumed the same binding status as domestic law and could therefore be invoked directly by the courts”. The delegation, however, reported that the need to invoke the provisions of the instrument had not arisen by either the plaintiff, the defendant or the judge. The delegation attributed the cases where claims of racial discrimination failed to be brought to the courts to “ignorance” since “the provisions of the relevant instruments had been widely disseminated and there were certainly no obstacles to bringing such matters to court”. 70 According to a 1997 report by Human Rights Watch, however, “[i]n an atmosphere in which the rule of law is beset by uncertainty and contradictions, vulnerable groups such as religious and ethnic minorities are likely to be among the primary targets of abuse. Isolated cases in which the courts have ruled in favor of religious minorities do not disprove the observation that courts cannot be relied upon to protect for religious minorities the rights provided in domestic law” (HRW, Citation1997). Even though the language used during this reporting cycle’s review seems to be calmer and more cooperative, yet the ambiguities and dichotomies still subtly exist. This is due to the fact that hybridity is firmly established in the Islamic Republic and its expressions are inevitable within a contemporary authoritarian setting.

9. 2000

9.1. CRC (reporting cycle I)

As the timeline in Figure illustrates, only the periodic report based on CRC was reviewed in the year 2000. CRC is the first core Convention that was ratified after the 1979 Islamic Revolution and it is also the first one subjected to a reservation by Iran. As was mentioned earlier, CRC was signed in 1991 and ratified in 1994, just a few years after the Iran-Iraq war had ended. During this period, Hashemi Rafsanjani was the president (1989–1997) and he took a pragmatist approach towards foreign policy. “Iran’s foreign policy was based on geo-political necessities and paid less attention to ideological assumptions”, according to Soltani and Ekhtiari Amiri (Soltani & Ekhtiari Amiri, Citation2010). This approach seems not to have extended to Iran’s dealings with the United Nations, however, at least not with regards to signing binding International treaties. Upon signature, Iran made a reservation “to the articles and provisions which may be contrary to the Islamic Shariah, and preserve[d] the right to make such particular declaration, upon its ratification”. Subsequently, upon ratification, the Iranian Government reserved “the right not to apply any provisions or articles of the Convention that are incompatible with Islamic Laws and the International legislation in effect” (UN, Citation1989).

9.1.1. Reservations

Due to its importance, the Committee was obviously concerned about Iran’s reservations to the provisions of the Convention. With regard to the reservation made to CRC, the Iranian delegation stressed, “in any country with a large bureaucracy, time was needed to approve or adopt decisions”. According to the delegation, the authorities “had consulted and were continuing to consult various governmental organizations and NGOs on the subject of the Convention, and their position was not set in stone”. 71 This suggests flexibility while portraying an optimistic promise on Iran’s part to withdraw its reservation especially since, according to the delegation, “[f]rom the examination of the compatibility of the Convention with both domestic and Islamic law, no fundamental contradictions had … emerged” 72 by the year 2000, nine years after CRC was adopted by Iran. While this was initially promising, the delegation further stated that it “hoped that a compromise could be reached to enable Iran to maintain its reservation to the Convention, about which it felt strongly. While it respected the Covenant, it preferred a different interpretation of certain aspects, such as age limits”. 73 In its concluding observations, the Committee found the “broad” and “imprecise” nature of Iran’s general reservation very concerning and stated that such reservation “potentially negates many of the Convention’s provisions and raises concern as to its compatibility with the object and purpose of the Convention”. 74

9.1.2. Invented tradition

Despite the delegation’s attempt to portray a positive undertaking on the part of the state to eliminate all forms of discrimination, 75 the Committee was of the belief that the delegation’s report only “dealt mainly with legislative provisions without presenting a critical evaluation of the situation of children in the country and without providing sufficient information on observance of the principle of non-discrimination, on the civil rights of children and in particular their freedom of expression and of religion, and on the administration of justice”. 76 However, even with the delegation’s report of the legislative provisions, the Committee was alerted to the way the children were presented. The Committee felt that in Iran’s periodic report, 77 the children were presented from a “paternalistic point of view”. The reservation made by Iran to this treaty has created a further barrier to the dialogue on human rights violations, especially when such violations stem from laws and regulations that are out-dated.

With the coming of Khomeini, a set of laws and regulations were enforced that only resemble the laws that were introduced roughly 1400 years ago during the time of Prophet Mohammad. Eric Hobsbawm suggests that in cases of “rapid transformation of society” that weaken or destroy the “social patterns for which ‘old’ traditions had been designed”, an invention of tradition could result (Hobsbawm, Citation2000, p. 4). Hobsbawm defines an invented tradition as a “set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past” (Hobsbawm, Citation2000, p. 1). Applying this theory to the case of Iran, which had undergone a rapid cultural, social and economic change by the time Pahlavi era ended yields interesting results.

Based on Hobsbawm’s theory, an invented tradition is usually constructed by a single initiator. Khomeini, as the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, introduced a supposedly unique ideology overtaking an old tradition whose tenets were no longer supported by their “institutional carriers” established by the monarchy. In an invented tradition, however, this is not because the “old ways are no longer available or viable, but because they are deliberately not used or adapted” (Hobsbawm, Citation2000, pp. 4–8). Khomeini claimed and made his ideology “appear” to be based on a “tradition”, which was “linked to an immemorial past”, which according to Parvin and Vaziri was inherited from Prophet Mohammad himself, to the Imams, and ultimately to the “learned theologians, the Faqihs” (Parvin & Vaziri, Citation1992, p. 81). However, since his ideology had to be “Re” traditionalised, it was no longer connected to any particular tradition. It was just designed to mimic. Therefore, as Eric Hobsbawm believes every tradition to be, Khomeini’s alternative ideology was “recent in origin”, “constructed”, “invented” and then rapidly “formally instituted” (Hobsbawm, Citation2000, p. 1).

This invented tradition left convenient and/or intentional gaps that are filled whenever needed and however desired by the regime. Such gaps have contributed to the severity of human rights violations and the impunity of their perpetrators in Iran. During this review, the Committee also found a dichotomy between the Iranian laws and regulations and their actual practices. With the case of the rights of the children, the Committee stated that the “formal guarantees of non-discrimination in the Constitution were not backed up by national legislation and customs”. 78 The judges, for example, do not “apply legislation dating from before the revolution”. That implies that, “in areas not covered by post-revolution legislation, they appl[y] their own expertise rather than the law”. 79 In a report by the International Coalition against Violence in Iran (ICAVI), it is stated that such invented laws and regulations only promote violence against children. Infants and young children are constantly incarcerated with their mothers, juveniles are continuously executed and guardians are legally allowed to marry their adopted children (ICAVI, Citation2014). Human rights violations against children are, of course, not limited to the above. In the year 2000, the delegation continued to show flexibility while requesting compromise in the interpretation of certain human rights principles. In addition, responses such as the authorities continue to consult with various governmental organizations and NGOs seem to be provided only to stall the state obligation to protect children especially when Iran keeps failing to submit its reports in a timely fashion.

10. 2003

In 2003, CERD met with the Iranian delegation once again for its XVI-XVII reporting cycle. While the Iranian delegation provided more thorough and detailed information in its state report, 80 the resistances continued to manifest themselves in the form of dichotomy and ambiguity especially in the primacy of law.

10.1. ICERD (reporting cycle XVI–XVII)

10.1.1. Primacy of law: Dichotomy & ambiguity

Once again in 2003, as in 1999, the Committee found discrepancy between paragraph 81 of Iran’s core document, 81 which should explain “the general legal framework for human rights protection, including matters relating to the Convention”, 82 and paragraph 45 of Iran’s 16th and 17th periodic reports 83 “regarding whether the Convention could be invoked before administrative bodies and the courts”. 84 In paragraph 45 it is stated,

According to article 9 of the Civil Code of the Islamic Republic of Iran, regulations under treaties signed by the Government in accordance with the Constitution, are legally binding. Therefore all the provisions of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, including article 4, are automatically incorporated into Iranian domestic legislation without need for new legislation, and constitutes legal reference in court.

The ambiguity resided in paragraph 80 of Iran’s core document, which begged clarification on the “distinction regarding the binding nature of international instruments ratified by the Islamic Consultative Assembly and approved by the Council of Guardians and those approved only by the Islamic Consultative Assembly”. 85 The Iranian delegation stated that the “International instruments must be approved by the Majlis 86 and endorsed by the [C]ouncil of Guardians”. 87

What the delegation fails to demonstrate here is the power relation behind the Iranian political structure. The Supreme Leader or the velayat-e faqih is the single most powerful religious and political figure in Iran and as such appoints six individuals to serve on the Guardian Council of the Constitution, which is a 12-member council. The head of the Judiciary, also appointed by the Supreme Leader, nominates the other six individuals, who must then be approved by the Majlis or the Islamic Consultative Assembly. Therefore, the Supreme Leader appoints the entire Council either directly or indirectly. The members of the public who nominate themselves for Majlis or the parliament also go through a screening process and have to be, in turn, approved by the Guardian Council before they can be elected by the public. The Supreme Leader, therefore, controls a seemingly democratic process while portraying a fair judicial check and balance. It is through this system that the international instruments and their implementations need to be approved. It well may be that the Iranian delegation’s claim that in practice no invocation had ever occurred 88 is true. How could one invoke the provisions of the Convention when in practice they are severely violated by the judicial system, whose head is appointed by the Supreme Leader?

11. 2005

After five years, in 2005, the Iranian delegation appeared in front of the CRC once again. It was also during this year that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected as the sixth president of Iran (2005–2013). According to Soltani and Ekhtiari Amiri, during Ahmadinejad’s presidency, Iran’s foreign policy resembled the war year period. During the years 1981–1989, an ideological approach was taken towards foreign policy, established on the belief that “foreign policy should be based on Islamic principles and assumptions” (Soltani & Ekhtiari Amiri, Citation2010). This policy led to a disregard for international organizations and criticism of interventionist policies of certain influential states. Ahmadinejad especially criticized human rights because of its “selective and instrumental application”. He believed that human rights are “another tool for putting pressure on countries that are against United States” (Soltani & Ekhtiari Amiri, Citation2010). Even though the delegation appeared in front of the Committee in 2005, the actual state report was submitted in 2002, before the transition took place and one of the main concerns of the Committee, meaning Iran’s general reservation to the Convention, remained the same.

11.1. CRC (reporting cycle II)

11.1.1. Reservation

In the second periodic review, Iran provided a lengthy report informing the Committee of the various measures taken by the government in education and protection of the most vulnerable children. 89 What it failed to do, however, was to provide “specific information on the implementation of the Convention, or a critical evaluation of the effects of the measures that had been taken to deal with the situation of children”. 90 Important issues such as the definition of the child, the right to life, freedom from discrimination and justice for minors were not addressed at all and these go back to the Islamic Republic’s general reservation to the Convention. 91 Referring to Iran’s general reservation, the Committee felt that it hindered the implementation of the principles of the Convention and it was still unclear which articles the Iranian government did not agree with. Thus, the Committee found it more difficult to comprehend the reservation to the current Convention since the other instruments ratified by the Islamic Republic bore no reservations. 92

The Committee insisted on knowing whether the position of the government had changed regarding its reservation or not since there was no indication in the written replies that any thoughts had been put into the withdrawal of the reservation. 93 However, instead of addressing the issue concerning the reservation, the delegation used the influx of Afghan and Iraqi refugees as a great challenge facing the government since the initial periodic review but commended itself on making positive changes and developing a “spirit of transparency, as demonstrated by the dialogue with the Committee” 94 despite difficulties. In its concluding observations, however, the Committee reiterated many of the same concerns and recommendations it made during the first periodic cycle. 95 Even with such an excuse as the influx of refugees, the challenge faced by the government post-1992 when the policy shifted, has been to pressurise and to repatriate the refugees. While this tactic has ended for Iraqi refugees, it is still on-going for the Afghans in Iran. Over the years, the Afghan refugees have increasingly faced “higher barriers to humanitarian aid and social services, arbitrary arrest and detention, and have little recourse when abused by government or private actors” (HRW, Citation2013; Moinipour, Citation2017; Van Engeland-Nourai, Citation2008).

This is especially true of the concerns over the “broad” and “imprecise” nature of the reservation made to the Convention by the Islamic Republic. The Iranian delegation assured the Committee that the Convention was “an integral part of domestic Iranian law since its ratification and was legally binding…”. 96 This is while by 2005, Iran had not as yet withdrawn its reservation and the Committee emphasized that such a reservation “potentially negates many provisions of the Convention and raises concern as to its compatibility with the object and purpose of the Convention”. 97 This observation was not exclusive to the implementation of the provisions of the Convention. The Committee also found Iran’s policies to be “fragmentary” with no “overall strategy” 98 while some of the practices on which these policies were imposed made their “origin” questionable. The Committee strongly noted that the origin of these policies did not seem to be “an inherent part of Islamic culture”. 99

In 2005, Iran started using international human rights language to point out the steps it had taken towards the education and protection of the children even though it failed to address the fundamental questions regarding how and whether such measures improved the lives of the children. In addition, the most important question here is if the Iranian government felt it necessary to take measures to protect and educate the children, why has it not withdrawn the reservation it has put in place on CRC? Is the regime threatened by the full implementation of CRC? By the delegation’s own admission, one of the issues holding back the government from removing its reservation is the age established in the international law as the limit to that of a child. Under the Iranian law, the age of maturity of a boy is set at 15 and set at 9 for girls while the international human rights law sets both at 18. The age limit set by Iran threatens the wellbeing and security of many vulnerable children. It allows for child labor, forced child marriage, domestic abuse and violence, juvenile execution, life imprisonment, corporal punishment and more (CRIN, Citation2015). This shows that Iran’s preparation of fuller periodic reports and a seemingly more cooperative and flexible approach to the dialogues with the UN Committees are a mere ruse to get away with human rights violations but show good faith in the eyes of the international community.

12. 2010

In 2010 only the state report on CERD was reviewed. Iran provided a detailed report, 100 which was received with satisfaction from the Committee. 101 However, once again, the Committee was disappointed that the report bore “insufficient information on the practical implementation of the Convention”. 102 At the same time, the delegation felt that some of the issues raised by the Committee “fell outside the scope of its mandate” but conveyed that it will “endeavour to answer them, in a spirit of cooperation”. 103 While the delegation’s spirit of cooperation appears to be in good faith, the human rights issues in Iran go beyond verbal promises. The issues are firmly rooted in the Iranian legal framework. In a parallel report submitted to the Committee by Amnesty International, it is stated that “while the legal framework in Iran would appear, on its face, to afford protection to members of minorities, in practice they are subject to discrimination by the authorities in many aspects of life and are unable to enjoy economic, social and cultural rights or their civil and political rights without discrimination, as provided by the Convention” (Amnesty International, Citation2010).

12.1. ICERD (reporting cycle XVIII–XIX)

12.1.1. Religious discrimination and the primacy of law

One of the issues that not only the CERD but also other Committees such as the CESCR have raised since the 1990s, at least since the electronic copies of the official dialogues have been made available, is the case of the Baha’is in Iran. In 2010, as in previous years, the delegation insisted that the case of the Baha’is did not concern the Committee because article 5 of the Convention “concerned religious issues related to ethnicity, not religious issues in general. As such, it did not cover the situation of the Baha’is or similar cases”. The feeling against religious minorities, especially the Baha’is, was so strong that the delegation felt that “such issues should not be included in its report”. However, the Iranian delegation clearly did not wish to lose the reputation it was gaining of being cooperative and transparent. The delegation, therefore, “reaffirmed [its] Government’s willingness to cooperate with the Committee in its work”. 104 Despite the fact that in earlier years, the delegation attempted to portray Iran as a nation free from discrimination, in the 2010 periodic review, the Committee still questioned Iran on its human rights records and condemned it for subjecting groups “to discriminatory ideological selection”. 105 The parallel report submitted to the Committee by Amnesty International illustrates that human rights violations of 2009, after the controversial presidential election of Ahmadinejad, had a particularly severe impact on minorities, “not least because the authorities [had] sought to blame members of minority groups in Iran—notably Baha’is—for fermenting unrest and scapegoat them” (Amnesty International, Citation2010). Official reports from the Baha’i International Community also show that the discrimination against the Baha’is became systematic and a matter of state policy right from the beginning of the Islamic Revolution (BIC, Citation2016b). In a joint report from several civil society organizations to the Committee, it is stated that the Iranian Constitution “has refused to recognise a number of faith” including the Baha’i faith and various branches of Sufis (CitationFIDH, LDDHI, & DHRC, 2010), which deprives them of status under the law.

The delegation felt that the Baha’is do not belong to any particular ethnic, religious or linguistic group. Therefore, the Committee has no say in the matter. However, to show its good faith, the delegation stated, “all citizens were equally entitled to services such as health care, education and housing”. 106 What it failed to convey and to acknowledge was the existence of many state policies that have either barred the Baha’is from entering universities or have caused them to be expelled afterwards “by the requirement to declare their allegiance to Islam or one of the three officially recognised religions 107 in application forms” (CitationFIDH, LDDHI, & DHRC, 2010).

The reality of the human rights situation in Iran seems to be the precedence of the Islamic law over the provisions of the Convention. For the first time, in 2010 periodic review, the Iranian delegation narrowed down the power of the “clerics” to the position of the Supreme Leader in deciding on “citizens’ rights”, which according to the delegation are “enshrined in different laws and regulations, particularly in the Act concerning the protection of citizenship rights”. The delegation held that “the general policies applicable to such rights had been endorsed by the Supreme Leader”. 108

Upon the Committee’s request for the Iranian delegation to “explicitly acknowledge the primacy of the Convention over domestic legislation, in order to prevent possible conflicts between the two in future”, 109 the Iranian delegation maintained, “all provisions of ratified international conventions were on a par with national legislation”. However, it confessed, “the primacy of international law over domestic law was not recognized in Iran”. Notwithstanding, in order to show good faith, the delegation professed that “any laws adopted before the Islamic Revolution that had been explicitly identified as being incompatible with Islamic law or the Constitution of the Islamic Republic were revoked, but the [ICERD] remained fully in force …”. 110 The data suggest that in 2010, a bolder stance was taken by the delegation to explicitly maintain that the primacy of international law over domestic law is not recognized in Iran. Yet, upon confessing to such a statement, the Iranian delegation, once again in “good faith”, holds that ICERD is fully in force. Considering the contrast with the delegation’s first statement, this seems to be nothing but a hypocritical presentation.

13. 2011

In 2011, Iran’s third periodic report on the ICCPR was reviewed with an 18 year gap from the second periodic review. During the 2011 review, the HR Committee found the responses to most of its specific questions non-comprehensive and incomplete. 111 Similar to the dialogue in 1992–1993 where the Iranian delegates found the application of the Convention to be rigid, in 2011, they asked for “the cultural specificities of the State party… [to] be taken into account when discussing the Covenant’s application”. 112

13.1. ICCPR (reporting cycle III)

While over the years, the State reports had become more detailed, though mostly not in response to the Committee’s questions, 113 and the language of the dialogues more in line with the provisions of the Convention, on certain issues, such as human rights violations against religious minorities, more specifically against the Baha’is, there was a marked change in attitude on the part of the delegation. In previous reviews, there was a simple denial of any existence of discrimination in the country. In 2011, however, the delegation emphasised that the Islamic Republic does not recognize the Baha’i faith as a religion. The delegation based the definition of individual right to freedom of thought, belief and expression on Articles 18 and 19 of the Convention but was quick to make them contingent upon not being harmful to other people's freedom and to the “security, order, health and morals of the society”. 114 This is an important issue worth examining since it involves the largest non-Muslim religious minority in Iran. As one of the civil society organizations, the Baha’i International Community also submitted information to the Committee, in which a few principles of the religion are mentioned. Some of these principles seem to threaten the position of the clergy in Iran. One is that “there is no clergy in the Baha’i Faith”. According to the statistics provided, there are Baha’i communities in over 180 countries without a threat to any state (BIC, Citation2011) as unity in diversity and equality of men and women are a few of their religious tenets.

Based on an overwhelming information received by various civil society organizations such as Amnesty International, Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre, Human Rights Watch and the Special Rapporteur’s report, the Committee found the Baha’is to be arbitrarily detained, falsely imprisoned, their properties confiscated and destroyed, their graves desecrated, 115 denied employment and Government benefits and denied access to higher education. 116 Despite this evidence, the delegation insisted that the law protects everyone equally and everyone enjoys equal rights in Iran. In turn, the delegation accused the Committee of asking “very vague” questions, which were “accusative” in nature and which tarnish “the position of the Committee for the realization of constructive dialogue”. The delegation, then, conveyed the emphatic expectation of the Islamic Republic of Iran from the Committee “to adopt a fair approach to issues”. 117 What seems to have transpired in 2011 is similar to what Ayn Rand calls “argument from intimidation” by the Iranian delegation. Such intimidation is subtle and is not as obvious as argument from intimidation normally used in politics. However, it does contain similar elements. By turning the argument around and intimidating the Committee, the Iranian delegation forestalls the debate and bypasses “logic by means of psychological pressure”. The delegation also threatens “to impeach [the] opponent’s character by means of … argument, thus impeaching the argument without debate” (Rand, Citation2018). Therefore, instead of addressing the real issues, the Iranian delegation threatens the position of the Committee, which is unbiased and comprises independent human rights experts without any political ambitions or partisanship.

13.1.1. Will of the people