Abstract

This study explores into Japanese cultural meaning of nature. The paper studies Japanese domestic tourists to a mountain trail near Tokyo. East Asian concept of nature distinctively identifies itself as a unity between nature and humanity. To gain a more defining understanding of Shintoism-inspired meaning of nature, we surveyed on the meaning of nature, experiences and benefits sought and type of things they wanted to see during their visit. Two-stage content analysis identify two themes that are indicative characteristics of Shintoism; woods/forests and Kami (gods). While there is shared notion of nature within the East Asian meaning of nature, Japanese appear to have Shintoism-influenced concept of nature, distinct from other East Asian countries. Implications for future research are provided.

Keywords:

Public Interest Statement

This article investigated Japanese domestic tourists’ perspectives when it comes to visiting nature-based destinations. It was apparent that the meaning of nature for the Japanese tourists have links to the society’s cultural and religious backgrounds. As such, Shintoism, the country’s native religion, seems to be reflected in the visitors’ sense-making of nature. To the Japanese, nature and human are considered one. This notion of “oneness” is a distinct East Asian cultural trait and shared by other countries, such as China and Korea. Nature can also be viewed as something that can be re-invented according to traditional and modern life of things in Japan. Tourism industry sector that targets East Asian, Japanese market in particular, may benefit by implementing new product planning and development strategies that are more than a slight modification from the existing ones, which are dominantly focused on European and Western tourists.

1. Introduction

This paper studies Japanese domestic tourists in order to understand a Shintoism-influenced concept of nature. The present work aims to gain a better understanding of whether Shinto-religion traits-turned cultural-habitus of Japan have implications for contemporary domestic nature-based tourism. Nature-based experiences in the fast-growing markets of East Asia should not be viewed as homogeneous or replicas of Euro-West experiences within the region (Cater, Citation2006; Choo & Jamal, Citation2009; Li, Citation2008; Packer, Ballantyne, & Hughes, Citation2014; Weaver, Citation2002). In tourism, experiences are co-created through interactions between service providers and tourists (Lee & Prebensen, Citation2014; Prebensen, Vittersø, & Dahl, Citation2013). Recognizing points of departure, in terms of what nature means to tourists is an essential element about which the tourism industry should be informed.

Nature-based tourism activities have grown rapidly in Europe and other Western parts of the world. But this has not been the case for Asia. Until the advent of the twenty-first century, as a whole, Asia was a “place” visited by international (largely Western) tourists. Accordingly, the main discussions in the region have been more on product development or adopting Western practices in order to provide better tourist experiences for Western tourists (Dowling & Weiler, Citation1997; Lew, Citation1996).

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, debates have emerged regarding Asian forms of ecotourism. For example, Weaver (Citation2002) has argued that distinct forms of Asian ecotourism exist, albeit influences from the West were strong. On the other hand, Cater (Citation2006) purports that Asian ecotourism is indeed a Western construct, and subsequently, Asian practices of ecotourism-relevant activities need to be researched (Cater, Citation2006). More recently, studies have demonstrated distinct forms of ecotourism in China (Buckley, Cater, Linsheng, & Chen, Citation2008) and in South Korea (Choo & Jamal, Citation2009; Lee, Lawton, & Weaver, Citation2013; Lee & Mjelde, Citation2007). In the Japanese market, the importance of tour guides in ecotourism is highlighted, linking this phenomenon to the country’s tourism policy framework (Yamada, Citation2011).

Shintoism is a Japanese indigenous animistic and shamanistic religion. Shinto (the way of the gods) has had a profound influence on the meaning of travel in Japan (Graburn, Citation2004). Shintoism has been adopted twice as the state religion: first, between the 7th and 8th centuries; and second, between the 19th and 20th centuries. In the seventh century, the adoption of Shintoism coincided with a time when amorphous Japanese indigenous belief gained a certain shape. This occurred due to a link between Shintoism and the Emperor - the physical and quintessential being of Japan. The link between religion and the Emperor was an attempt to bind people to the governing power. After gaining power from a previously disorganized country, the Emperor himself was declared to be the divine descendant of the Sun-goddess (Amaterasu) (Underwood, Citation2008). As a result of the political decision to adopt Shintoism as its national level religion, Japanese society espoused its central philosophy. Recent researchers, however, reveal that within the modern history of Japan, the native religion is also known for its legacy of being associated with building Japanese nationalism. Relatedly, this legacy has been intertwined with negative connotations of ultra-nationalism (Jensen & Blok, Citation2013). Within tourism studies, attention has turned to better understanding the motivations of Japanese domestic tourists, and potentially any inherent connection to Shintoism (Krag & Prebensen, Citation2016).

While Shintoism is a religion that provided a fundamental life philosophy to the Japanese, it has also been adopted as part of political practice and quite possibly might have been subjected to political maneuvering. Such use of religion or ideologies as part of political gains is not unique to the Japanese setting. History has witnessed similar trends beyond Japan. It is, therefore, important to note that the current paper takes the position of viewing Shintoism not as a “pure religion or spiritual concept” per se, but rather as a cultural belief and habitus (Bourdieu, Citation1990) at a national level. In this sense, Shintoism here is espoused in line with the approach taken by Heintzman (Citation2009), evaluating the spirituality in nature-based recreational activities. The approach acknowledges various elements, from which antecedent conditions are the most relevant conditions germane to the current study. The current paper based on personal history, connections to spirituality, experiences and exposures to religions; accordingly, takes the position that there are degrees of difference in portraying Shintoism traits among contemporary Japanese nationals.

To determine the specific traits of Shintoism in the Japanese concept of nature, this paper is organized into three main sections. The first section reviews relevant literature on East Asian understandings of nature, Shintoism in Japanese tourism and the main traits of the Japanese native religion. Second, the study method is explained and addresses the research approach, chosen method, data collection and analysis. The third section presents the study findings along with discussions in relation to the reviewed literature. Study limitations and future research directions are offered along with concluding remarks.

2. Understanding East Asian nature and tourism

For a number of decades, efforts to understand East Asian meanings of nature informed by regional religious and philosophical bases have emanated both from the natural and social sciences domains. For example, writing in Science, White (Citation1967) started a discussion on the relevant influence of Zen Buddhist ideology on society’s concept of nature. Comparing Judaeo-Christian societies’ dominant values wherein the environment exists for the benefit of humanity, White highlights the relevance of religion in understanding social perceptions of nature. The Judaeo-Christianity (religion)-informed perception of nature is deeply grounded in Genesis in the Bible. Specifically, God created the world in 7 days and humans, in the form of God, had the right to use God’s other creations for their own benefit.

An essential part of Zen Buddhist ideology – the intrinsic value of nature, that is, its inherent value or value “for its own sake” (James, Citation2003, p. 143), contrasts with the Judaeo-Christian concept of nature. Intrinsic value refers to the state of having meaning by its existence itself without being proven to be beneficial to others by becoming a tool for other existences in the world (James, Citation2004). The value of existence is believed to be a unique Zen Buddhist philosophy and not identified in Indian Buddhism (Lafleur, Citation2000). Zen Buddhism, known synonymously as East Asian Buddhism in the West in fact refers to a form of Japanese Buddhism and in Chinese, it is 禪 or Ch’an and in Korean 선 or Sŏn (Lee & Prebensen, Citation2014). Pointing out Zen Buddhist intrinsic value is significant here because when Buddhism arrived in Japan from China partly by way of Korea in the 6th and 7th centuries; the long-standing Shintoism had a great influence in shaping Zen Buddhism in Japan (Fujisawa, Citation2015). Similar to the different versions of East Asian Buddhism in the three countries, China and South Korea practice their own forms of ecotourism: Chinese Shengtai luyou (Buckley et al., Citation2008) and South Korean Shengtae Gwangwang(생태관광) or ecology tourism (Lee et al., Citation2013), while sharing the nature-human unity concept of East Asia.

Tourism researchers have partly adopted findings from environmental studies, and have applied them to tourism settings. Reflecting on the links between environment and tourism, Holden (Citation2016) asserts that the concept of environment is informed by the cultural and religious backgrounds of a given society. Similarly, this position can be further extrapolated to the meaning of sustainability in tourism, which also cannot be seen as a monolithic concept. The socially constructed concept of nature is an important aspect that needs to be noted.

Within East Asian tourism and tourists, the focus has been on unity between nature and humanity, informed by the region’s religious and cultural traits (Li, Citation2008; Wen & Ximing, Citation2008). Enquiries into the East Asian concept of nature brought out somewhat puzzling findings to date. While the cultural philosophies of the regions highlight the unity between nature and humanity, the researchers’ interpretations on the East Asian tourism and tourists’ use of nature and environment in tourism appear to be rather anthropocentric (Arlt, Citation2006; Hashimoto, Citation2000). The mixed state of interpretations on East Asian environmental attitudes may be attributed to our currently insufficient understanding of the East Asian construct of the relationship between nature and humanity. Knowledge of a Shintoism- influenced concept of nature in tourism will contribute to a better understanding of East Asian meanings of nature in tourism.

3. Shintoism-influenced concept of nature in Japan

The distinctive East Asian view of nature and human as a unity (Tu, Citation1985; Tucker, Citation1991) is prominent in the Japanese perception of nature. Affirming an East Asian perception of nature, the Japanese native religion Shintoism, views a tripartite relationship between Kami (神 or deity), human beings and nature. This means that within Shintoism beliefs, there are no clear distinctions between one or the others (Ueda, Citation2004). This Shintoist and East Asian view of nature is comparable to that of Western Judaeo-Christian distinctions between humans, nature and God (Prebensen & Lee, Citation2013).

It should be noted here that Shintoism is not the only native religion in Japan. For example, Japanese fear nature and have a certain tendency to wear away something in the hope of avoiding natural disaster (Terada, Citation1948). Also, there is another unique Japanese native religion: Shugendo. This native religion seeks enlightenment, hence its later incorporation into Buddhism. In the hope of seeking enlightenment, people perform hard practices/tasks, such as, carrying casks in mountains (Miyake, Citation2001).

Further consistent with the East Asian concept of nature, there was no word for nature in the ancient Japanese language (Fukushima, Citation1975). The ancient Japanese did not perceive nature as an object that was separate from human beings, subsequently, there was no specific Japanese word, which referred to “nature”. Similarly, the Japanese had a tendency to perceive the world only in subjective and/or objective settings. That is, the Japanese would perceive the universe as a collection of numerous individuals, consequently, they did not have an abstract word that comprehensively captured “nature”. In the absence of a specific word referring to nature, they used `the heaven and earth, mountains, and rivers’ or “mountains and rivers, grasses and trees”. It was around 1900, the time when European scientific culture entered Japan that the Japanese started to objectify nature and to use the term shizen (自然) as an equivalent to “nature” in Western languages (Nonaka, Citation1999).

When we consider specific aspects of Shintoism in relation to tourism or travel, two specific points should be highlighted. First, Shintoism provided religious legitimacy to travel and secondly it provided infrastructure for travel in the pre-modern Japanese society. Not dissimilar to the Euro/Western societies, traveling was a very rare activity to people before the Kamakura period or up until 1185 in Japan (Kawaguchi, Citation1998). During the Edo Period (1603–1868), the only cross-domain-border travel that was permitted apart from business trips was for religious (pilgrimage) and medical purposes. Special recognition for religious travel by authorities demonstrates the influence of Shintoism on travel. With the recognized significance of travel for those practicing Shintoism, Kumano Kodo(熊野古道)or major routes were built during this period to enable lords’ processions. Shukubamachi(宿場町) or accommodation facilities) were also developed during the Edo Period. Owing to the offerings and protection afforded by the residents along the main routes and rich people, those without resources were still able to fulfill their purpose for traveling. In 1830, about five million people, equating to about one in six people at that time in Japan, visited Ise Shrine on the Kumano Kodo route (Kanamori, Citation2002).

As the current paper aims to identify Shintoism-relevant traits in contemporary nature-based tourists, delineating specific Shintoism characteristics might be appropriate. There are two distinct characteristics in Shintoism: existence of multiple Kami (god) and the significance of woods/forest. With its distinct trait of multiple Kami (god), Shintoism is described as “incurably polytheistic and is able to create new Kami from time to time” (Underwood, Citation2008, p. 18). In this regard, the way in which Buddhism was introduced and settled in the country may describe this aspect of Shintoism. Indeed, when Buddhism came to Japan, around the beginning of the sixth century, it went through a transformation from a human-centered religion to a nature-centered one (Umehara, Citation1990; Umehara & Yasuda, Citation1993). From then until now, the bulk of its history relates to being accepted in Japanese society as a religion. There is little doubt that Buddhism has dominated Japanese spiritual life for a long time, but it has accepted some indigenous Japanese traits. These traits include worshiping indigenous deities (deities of the heaven and earth) and ancestors since such worshipping existed well before the arrival of Buddhism as part of Shintoism characteristics (Takatori, Citation1993). One specific philosophy embraced by both Buddhism and Shintoism, which enables a strong affinity between the two religions, is the sense of non-permanence. This shared worldview, that there is no permanent state of being in the universe, has contributed to the firm establishment of Buddhism in Japan (Terada, Citation1963).

For the second central trait in Shintoism, we now turn to the significant meaning of woods and forests. Woods, forests and mountains are considered as the ultimate sign of strength and abundance of life because water and Sun provide the life base for trees that make up the woods, forests and ultimately mountains (Sonoda, Citation2000). Most Japanese woods are found in the mountains, where there are Satoyama (里山, forests that people have used for a living) and Okuyama (奥山, deep in the mountains where people do not enter). The first type, Satoyama was inseparable from local life as the low-rising hills were incorporated within the ecological system of local life (Kawai, Citation1995). On the other hand, the second type, Okuyama was thought to be a place where ancestors’ spirits and deities resided. Thus, it was not seen as a place for enjoyment or frivolous activities.

Shintoism has been omnipresent in the Japanese society throughout history. In modern history of East Asia, this Japanese native religion is also known for its legacy to build Japanese nationalism, which in often cases, has been intertwined with negative connotations of ultra-nationalism. Jensen and Blok (Citation2013), highlight that Shintoism certainly has an ideological function but it is not the sole function (p. 93). While recognizing the existence of the debates on the ultra-nationalism-building Shintoism, the current study limits its scope to the narrow focus of Shintoism’s influence on the construction of the meaning of nature.

4. Method

This study employed a two-staged content analysis of a structured qualitative data-set. After conducting content analysis to identify patterns of the collected data, summative content analysis was used to search for Shintoism-specific aspects in the data. Self-administered questionnaires with open- ended questions: (a) the meaning of nature, (b) what kind of benefits are sought when visiting nature-based attractions, (c) what are the experiences sought and (d) what are the things that the visitors would like to see; were distributed to nature-week event participants in a mountain near Tokyo. The chosen site was Gotenba Trail Station, the starting point of a trail up to Mt. Fuji. This site is located in a World Cultural Heritage zone in Japan. Japanese native speaking authors of this paper and trained research assistants approached potential survey participants and explained the aims of the study. They also explained that participation was voluntary and that survey participants could withdraw any time, if they wished to discontinue their participation. Two groups of lead-researcher and research-assistants made individual approaches to visitors regarding survey participation. In total, 156 usable surveys were collected for this study.

As a first step of the analysis, content analysis (Holsti, Citation1969; Kaid, Citation1989) was employed. This was used to gain an overall understanding of the collected data. Two Japanese native speaking researchers and two non-Japanese speaking researchers collaborated for data collection, analysis and interpretation. The collected data were in Japanese language. The responses were translated into English language in order to facilitate the non-Japanese speaking researchers’ active participation in the analysis and interpretation stages along with the Japanese-speaking researchers, who worked with the original Japanese answers to the questions. Thus, the two teams of Japanese speaking and non-Japanese speaking researchers respectively proceeded with the content analysis of the original and translated data-set, regularly comparing results with each other. Particular attention was given to adequate levels of correspondence between Japanese and English-translated words when comparing the results of the content analysis. This ensured that when the next stage of analysis was performed, the two teams referred to mutually compatible, although not necessarily identical, social meanings that were determined in the original and the translated data sets. This approach recognized and managed possible misinterpretations of the languages used as part of a qualitative research data-set (Polkinghorne, Citation2005). It should be noted that this study was based on text-based answers to open-ended questions. The often-used theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) in qualitative research was not viable, thus, we resorted to static sampling with all collected data-set.

As the aim of this study was to identify any Shintoism-inspired meanings of nature, summative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) was used for the second stage of the analysis. Keywords were derived from the interests of researchers or reviewed literature in a summative content analysis approach. That is, the searched-for key words or ideas were not solely derived from the data as expressed in the respondents’ text-based answers. This approach was also comparable to a directed content analysis approach where codes are defined before and during data analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Adopting a summative approach in content analysis, key words that appeared to reflect two main Shintoism aspects – multiple Kami (god) and significance of woods/forests were searched for in respondents’ answers.

The questions posed to respondents did not explicitly solicit any religious or philosophical value-related words or expressions. Thus, the researchers contextualized the Shintoism aspects within the contemporary visits to the nature-based attraction. For example, when analyzing the answers on the meaning of nature, we searched whether any particular meanings were endowed to woods/forests. On the question of kind of experiences sought by the visitors, we looked for any symbolically meaningful experiences or activities in the contemporary Japanese society. This was in recognition of Shintoism’s multiple Kami (god) aspect – the polytheistic nature of the religion. The polytheistic nature of belief enables Japanese to create new Kami (god) from time to time. As Underwood (Citation2008) puts it, this may reflect a society’s dynamic cultural creation of meanings reflecting time and spatial boundaries. We also looked for whether some experiences were given more meaning if they were associated with woods or forests. Similarly, on the question of what visitors would like to see, we searched whether the Japanese domestic visitors gave any special meanings to particular flora or fauna in the woods compared to others that were not associated with woods/forests. When analyzing the benefits sought, we looked for any particular characteristics in the benefits sought from woods or forests compared to other forms of nature, such as, sky, water and so forth (see Table ).

Table 1. Shintoism aspects and the focus of analysis

A series of discussions between the two-language based research members took place throughout the analysis and interpretation stages. At all times, attention was given to make certain the social and cultural integrity of the original language. This ensured that the survey results would not be misrepresented or unreasonably extrapolated. When such a tendency appeared to be occurring, researchers agreed to speak to Japanese people and also referred to social and mainstream published media channels for more contextualized social background information. This practice, although not directly checking with survey respondents, served as a form of member checking (Seale, Citation1999) in guiding the analysis process.

5. Through the lenses of Shintoism

We asked about the meaning of nature, particular experiences and benefits sought and the preferred things to see, while visiting a nature-based attraction near Tokyo. Through the two-step analysis, the findings are presented in Table .

Table 2. Summary of findings

The findings show that across the three questions on the meaning of nature; sought experiences and benefits when visiting nature-based attractions that the responses were closely related to seeking relaxation from nature. This is represented by ideas, such as, “Relaxation/diversion” (35/78 = 45%), “Healing and relaxation” (53/131 = 40.5%) and “Refreshed by nature” (77/114 = 67.5%) being the most significantly captured themes. On the surface, the overall picture does not appear very different from the tourists’ experiences, which had non-Shintoism backgrounds (e.g. Mehmetoglu, Citation2005; Silverberg, Backman, & Backman, Citation1996). On closer inspection, however, respondents talked about receiving inspirational healing from the natural elements like mountains, rivers, streams trees and the like. This specific pointing to the individual elements of nature may have a link to Shamanism, which influenced the formation of Shintoism. In Shamanism, all elements of nature and the environment have their own soul or spirit regardless of whether the element has life or not (Fairchild, Citation1962). In this way, the identified Japanese sense of healing in the responses has certain links to Shintoism characteristics in Woods/Forests and Kami.

The most frequent things respondents said that they wanted to see were “Trees and leaves, Rocks, Mountain, Animals in mountain/forest, Flowers, Lakes” (72/130 = 65%). Even if the Japanese have started to objectify nature and to use the term shizen(自然) as an equivalent to “nature” in Western languages, in the survey the respondents did not use the word to refer to “nature”. Instead, the specific denotation of the individual elements in nature reflects the Japanese Shintoism-influenced habitus (Fairchild, Citation1962). With the presence of the observable traits of Shintoism, the following three themes are presented here with a more focused deliberation on each topic.

5.1. Fureau (ふれあう) or Interacting with nature in Shinto (way of gods)

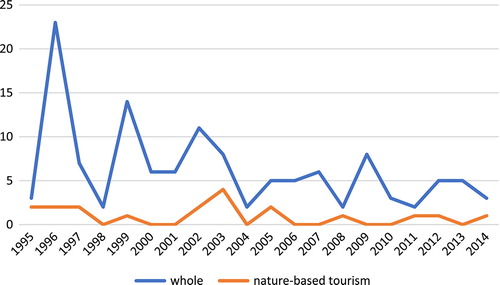

The word Fureau (ふれあう) or to interact is defined as the act of touching one another, or the act of becoming familiar with something by directly encountering and seeing it, such as, in encountering a masterpiece. While not frequently recounted, the surveyed visitors mentioned this idea as benefits or the experience sought. This might demonstrate the possibility of a Japanese-unique form of ecotourism or nature-based tourism, comparable to the Chinese Shengtai luyou and the South Korean Shengtae Gwangwang(생태관광) or ecology tourism. Indeed, the term Fureau (ふれあう) or interacting with nature has been used by researchers in Japan, including the field of tourism. One way of determining the frequency of the use is to turn to the country’s academic database service, Cinii. Cinii Articles (NII Academic Information Navigator) is a database service, which enables one to search information found in academic articles published in academic society journals, university research bulletins or articles included in the National Diet Library’s Japanese Periodicals Index Database. Searches in the Cinii Articles database revealed the number of articles that included the phrase “shizen to fureau” (interact with nature) or “shizen tono fureai” (interaction with nature) in the title (Figure ).

Figure 1. Frequency use of the words “shizen to fureau” or “shizen tono fureai” in academic journals in Japan from 1995 to 2014

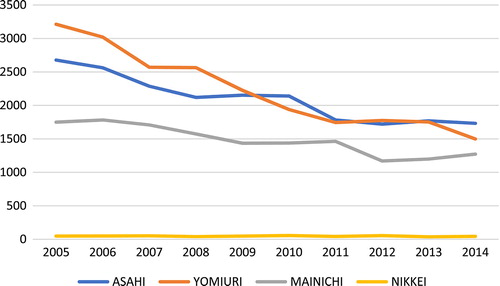

Looking into the result carefully, it has been noted that the phrases “interact with nature” or “interaction with nature” are mostly used in the context of children’s education, such as, for environmental education and experiencing nature, or in the context of medicine, such as, forest therapy. To further gain understanding on the use of these terms in the society, national newspapers of Japan were also searched. A clear presence of the terms’ usages was evident in major newspapers in the country (Figure ).

Figure 2. Frequency use of the words fureau or fureai in national newspapers in Japan from 2005 to 2014

Unsurprisingly, Nikkei, a financial newspaper, had the lowest rate of the terms’ use. While, for some reason, the usage appears to be steadily declining, it is nonetheless a clear presence in the society. This presence, in turn, could reflect the Japanese form of nature perception comparable to other East Asian examples (e.g., Chinese Shengtai luyou and the South Korean Shengtae Gwangwang).

While the notion of Fureau (interacting) has been the focus here, it is important to be aware that the non-interacting aspect (Kakurisuru or bunrisuru) is just as important in the Japanese notion of nature. This is because the non-interacting dimension (Kakurisuru or bunrisuru) indicates making a space in order to isolate from nature (Hamaguchi, Citation1988). Among the Japanese people, these two inconsistent senses live together without problems. Given this dualistic perception on nature of Japan, the ways in which western influences have developed are areas for further research.

5.2. Forest bathing

As an experience, forest bathing was the second most mentioned activity. As shown in Table , when respondents talked about relaxation in nature, it associated with the concept of healing. Respondents employed the specific term “healing” in answer to the questions on the meaning of nature and benefits sought. This indicates a link between healing from nature, its elements and forest bathing.

The practice of forest bathing is not unique to Japan. Indeed, there has been a long tradition of forest bathing for the benefit of improving health in Korea (Shin, Yeoun, Yoo, & Shin, Citation2010). While South Korea does not share the Japanese Shintoism as a religion or as cultural habitus, both Japanese and Korean cultural habitus on nature were traditionally shaped by long-standing tradition of Shamanism. Further, both countries’ practices are related to healing by nature and its elements. The concept of healing from nature-based experiences, such as forest bathing has been widely used in Korea and it also has been adopted in today’s tourism industry (Bae, Lee, Kim, & Piao, Citation2014). While it is not a unique phenomenon in Japan, forest bathing, as a practice to link the natural element of the forest and woods to the benefit of human healings, can be reasonably assessed as an influence from Shamanism and, subsequently, a Shintoism-influenced Japanese concept of nature.

5.3. Is Ghibli a modern Kami?

A response that describes the exquisite natural beauty of the visited mountain area “as perfect as seen in Ghibli” caught all of the authors’ attention but more from the non-Japanese side. To the non-Japanese researchers, this response did not even appear as a positive description on natural beauty. How could one describe something as pristine as nature to human-crafted modern animation? However, with assistance from earlier works on the Japanese animation films and Shintoism, this response is deemed to open up an extremely intriguing point on the Japanese notion of nature. That is to say, the quintessential Shintoism element Kami (gods) in the twenty-first century world with technology shapes a great deal of people’s lives; the very notion of nature may be contested and shaped by the latest technological advancement. The film industry, particularly, the world-famous Japanese animation films might be acting as the new Kami for nature.

Indeed, there are some examples of Japanese animation films that can be attributed to the idea: Ghibli as a modern Kami. Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli is a national animator, who represents things Japanese and aspects of the Japanese people. According to Miyazaki, the greatest distinguishing feature of Studio Ghibli lies in the way that it portrays nature, where nature is not subordinate to humans or the films’ characters. Critically analyzing Ghibli films, including Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro in 1988, Pom Poko in 1994 and Howl’s moving Castle in 2004, Wilson and Wilson (Citation2015) provide a strong and analytical argument that the Ghibli films are the contemporary agents of Shintoism (along with Daoism) on nature. Further, nature depicted in Miyazaki’s animations has been described as not being easily comprehended, as it is multifaceted and depicts a state of nature that continues to change with the intermixing of disparate components. The animations have depicted the mystique of a multifaceted nature, which are deeply associated with water and trees/woods (Sugita, Citation2015). Such association in Miyazaki’s works reflects Shinto motifs (Boyd & Nishimura, Citation2016). Additionally, Wright (Citation2005), upon analyzing several of Hayao Miyazaki’s works from a religious studies perspective, argues that the key concept of Miyazaki’s films lies in viewing the world through Shinto animism and the mystical relationship between humanity and nature.

Placed in the context of the earlier studies, natural beauty described in relation to the Ghibli films reminds us of the quintessential Shintoism nature by Underwood (Citation2008): “incredibly polytheistic and is able to create new Kami from time to time” (p. 18, emphasis added). Is Ghibli a modern Kami? Further research needs to follow.

6. Limitations and future study directions

Like any other research, the current study has limitations and these can inform the direction of future studies. First, a more interdisciplinary approach should be taken in future research. The current study essayed, within the given limitations, to comprehend and adopt the relevant literature from various disciplines. But this can be further expanded to include more relevant literature, particularly, written in languages other than English. Secondly, the current study employed a set of open-ended questions for the respondents to communicate using their own words. This had an advantage, such as in the discovery of Ghibli possibly a modern Kami. However, the limited space to provide their responses and the nature of pencil and paper questionnaire data collection proved to be limited to get into deeper meanings of what was provided by the respondents. We, therefore, suggest a more innovative approach to methods in future study endeavors. This may include research techniques that can capture deeper levels of meanings (e.g. in-depth interviews, observations with conversations, etc.) as well as diverse use of materials, such as films. Finally, it would be a valuable investment to study whether the domestic and international tourism experiences of Japanese tourists display different tendencies when it comes to a Shintoism-influenced concept of nature. Research efforts into furthering our understanding on East Asian and a Shintoism-influenced Japanese concept of nature must continue.

Funding

The publication charges for this article have been funded by a grant from the publication fund of UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Young-Sook Lee

This is part of a bigger research initiative between two universities (Waseda University, in Japan and UiT The Arctic University of Norway in Norway). With growing importance and numbers of tourists from Asia to Norway, Tourism Professor (Young-Sook Lee), Marketing Professor (Nina K. Prebensen), Sports Scientists (Professor Seiichi Sakuno and Professor Kazuhiko Kimura) conducted the initial research to better understand the meaning of nature from the Japanese Shintoism perspective. Prof. Lee’s areas of research include East Asian tourism and Arctic tourism. Prof. Sakuno’s areas of research include sport organization and community sport management. Prof. Prebensen specializes in consumer behavior, value co-creation and tourism. Prof. Kimura’s areas of research include sport management and sport tourism.

References

- Arlt, W. G. (2006). Thinking through tourism in Japan. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development , 3 (3), 199–207.10.1080/14790530601132377

- Bae, Y. M. , Lee, Y. , Kim, S. M. , & Piao, Y. H. (2014). A comparative study on the forest therapy policies of Japan and Korea. Journal of Korean Forest Society , 103 (2), 299–306.10.14578/jkfs.2014.103.2.299

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). Structures, habitus, practices. The logic of practice , 52–65.

- Boyd, J. W. , & Nishimura, T. (2016). Shinto perspectives in Miyazaki’s Anime film “Spirited Away”. Journal of Religion & Film , 8 (3), Article: 4.

- Buckley, R. , Cater, C. , Linsheng, Z. , & Chen, T. (2008). Shengtai Luyou: Cross-cultural comparison in ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research , 35 (4), 945–968.10.1016/j.annals.2008.07.002

- Cater, E. (2006). Ecotourism as a western construct. Journal of Ecotourism , 5 (1–2), 23–39.10.1080/14724040608668445

- Choo, H. , & Jamal, T. (2009). Tourism on organic farms In South Korea: A new form of ecotourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 17 (4), 431–454.10.1080/09669580802713440

- Dowling, R. K. , & Weiler, B. (1997). Ecotourism in Southeast Asia. Tourism Management , 18 (1), 51–57.10.1016/S0261-5177(97)86740-4

- Fairchild, W. P. (1962). Shamanism in Japan. Folklore Studies , 21 , 1–122.10.2307/1177349

- Fujisawa, C. (2015). Zen and Shinto: A history of Japanese philosophy . Open Road Media.

- Fukushima, Y. (1975). Shizen hogo towa nanika [What is the conservation of nature?]. In Shizen no hogo [The conservation of nature]. Jiji Press ( in Japanese).

- Glaser, B. , & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory . London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

- Graburn, N. (2004). The Kyoto tax strike: Buddhism, Shinto, and tourism in Japan. In E. Badone & S. R. Roseman (Eds.), Intersecting journeys: The anthropology of pilgrimage and tourism (pp. 125–139). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Hamaguchi, E. (1988). Nihonrashisa no saihakken [Rediscovery of Japanese]. Kogansha ( in Japanese).

- Hashimoto, A. (2000). Environmental perception and sense of responsibility of the tourism industry in Mainland China, Taiwan and Japan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 8 (2), 131–146.10.1080/09669580008667353

- Heintzman, P. (2009). Nature-based recreation and spirituality: A complex relationship. Leisure Sciences , 32 (1), 72–89.10.1080/01490400903430897

- Holden, A. (2016). Environment and tourism . Routledge.

- Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Hsieh, H. F. , & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research , 15 (9), 1277–1288.10.1177/1049732305276687

- James, S. P. (2003). Zen Buddhism and the intrinsic value of nature. Contemporary Buddhism , 4 (2), 143–157.10.1080/1463994032000162965

- James, S. P. (2004). Zen Buddhism and environmental ethics . Aldershot: Hampshire Ashgate.

- Jensen, C. B. , & Blok, A. (2013). Techno-animism in Japan: Shinto cosmograms, actor-network theory, and the enabling powers of non-human agencies. Theory, Culture & Society , 30 (2), 84–115.10.1177/0263276412456564

- Kaid, L. L. (1989). Content analysis. In P. Emmert & L. L. Barker (Eds.), Measurement of communication behavior (pp. 197–217). New York, NY: Longman.

- Kanamori, A. (2002). Edo shomin no tabi [Travel of public in the Edo era]. Heibonsha Limited (in Japanese).

- Kawaguchi, J. (1998). Nihon no tabi sengohyaku nen [Fifteen hundred years of tourism in Japan]. Kousai Publishing (in Japanese).

- Kawai, M. (1995). Naze midori o motomerunoka [Why do you find green?: Recurrence to the true character of human]. In M. Yamaguchi , M. Kawai , T. Matsui , K. Higuchi , K. Nakamura , & Y. Nakamura (Eds.), Hito ha naza shizen o motomerunoka [Why does the person demand nature?]. Mita Publishing ( in Japanese).

- Krag, C. W. , & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). Domestic Nature-Based Tourism in Japan: Spirituality, Novelty and Communing. In Advances in Hospitality and Leisure (pp. 51–64). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Lafleur, W. (2000). Enlightenment for plants and trees. In S. Kaza & K. Kraft (Eds.), Dharma rain (pp. 109–116). Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

- Lee, C. K. , & Mjelde, J. W. (2007). Valuation of ecotourism resources using a contingent valuation method: The case of the Korean DMZ. Ecological Economics , 63 (2), 511–520.10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.12.011

- Lee, Y. S. , Lawton, L. J. , & Weaver, D. B. (2013). Evidence for a South Korean model of ecotourism. Journal of Travel Research , 52 (4), 520–533.10.1177/0047287512467703

- Lee, Y. S. , & Prebensen, N. K. (2014). Value creation and co-creation in tourist experiences: An East Asian cultural knowledge framework approach. In Creating Experience Value in Tourism (p. 248). Wallingford: Cabi.

- Lew, A. A. (1996). Adventure travel and ecotourism in Asia. Annals of Tourism Research , 23 (3), 723–724.10.1016/0160-7383(96)84666-4

- Li, S. F. M. (2008). Culture as a major determinant in tourism development of China. Current Issues in Tourism , 11 (6), 492–513.

- Mehmetoglu, M. (2005). A case study of nature-based tourists: Specialists versus generalists. Journal of Vacation Marketing , 11 (4), 357–369.10.1177/1356766705056634

- Miyake, H. (2001). Shugendo . Kodansha ( in Japanese).10.3998/mpub.18465

- Nonaka, R. (1999). Nihon bungaku ni okeru shizenkan [The view of nature in Japanese literature]. In Kurumisawa, Y. (Ed.), Kankyomondai to shizenhogo [Environmental issue and nature conservation] (pp. 51–66). Seibendo Publishing ( in Japanese).

- Packer, J. , Ballantyne, R. , & Hughes, K. (2014). Chinese and Australian tourists' attitudes to nature, animals and environmental issues: Implications for the design of nature-based tourism experiences. Tourism Management , 44 , 101–107.10.1016/j.tourman.2014.02.013

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 52 (2), 137–145.10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

- Prebensen, N. K. , & Lee, Y. S. (2013). Why visit an eco-friendly destination? Perspectives of four European nationalities. Journal of Vacation Marketing , 19 (2), 105–116.10.1177/1356766712457671

- Prebensen, N. K. , Vittersø, J. , & Dahl, T. I. (2013). Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Annals of Tourism Research , 42 , 240–261.10.1016/j.annals.2013.01.012

- Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative inquiry , 5 (4), 465–478.10.1177/107780049900500402

- Shin, W. S. , Yeoun, P. S. , Yoo, R. W. , & Shin, C. S. (2010). Forest experience and psychological health benefits: The state of the art and future prospect in Korea. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine , 15 (1), 38–47.10.1007/s12199-009-0114-9

- Silverberg, K. E. , Backman, S. J. , & Backman, K. F. (1996). A preliminary investigation into the psychographics of nature-based travelers to the southeastern United States. Journal of Travel Research , 35 (2), 19–28.10.1177/004728759603500204

- Sonoda, M. (2000). Shinto and the natural environment. In J. Breen & M. Teeuwen (Eds.), Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami (pp. 32–46). Abington, OXON: Roitledge.

- Sugita, S. (2015). Nature and Asian Pluralism in the Work of Miyazaki Hayao . Retrieved from http://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/a03903/

- Takatori, M. (1993). Shinto no seiritsu [Establishment of Shintoism]. Heibonsha Limited (in Japanese).

- Terada, T. (1948). Nihonjin no shizenkan [A Japanese view of nature]. Iwanami Shoten Publisher ( in Japanese).

- Terada, T. (1963). Nihonjin no shizenkan -kaiban [The Japanese view of nature - revised edition]. Iwanami Shoten Publisher ( in Japanese).

- Tu, W.-M. (1985). Confucian Thought: Selfhood as creative transformation . Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Tucker, M. E. (1991). The relevance of Chinese neo-confucianism for the reverence of nature. Environmental History Review , 15 (2), 55–69.10.2307/3984970

- Ueda, T. (2004). Tonbo to shizenkan [Dragonfly and Japanese perception of nature]. Kyoto University Press ( in Japanese).

- Umehara, T. (1990). Nihon towa nannanoka [What is Japan?]. NHK Publishing ( in Japanese).

- Umehara, T. , & Yasuda, Y. (1993). Mori no bunmei -Junkan no shisou [Civilization of the forest: Circulatory thought]. Kodansha Ltd ( in Japanese).

- Underwood, A. C. (2008). Shintoism: The indigenous religion of Japan . Pomona Press.

- Weaver, D. (2002). Asian ecotourism: Patterns and themes. Tourism Geographies , 4 (2), 153–172.10.1080/14616680210124936

- Wen, Y. , & Ximing, X. (2008). The differences in ecotourism between China and the West. Current Issues in Tourism , 11 (6), 567–586.10.1080/13683500802475927

- White, L. (1967). The historic roots of our ecological crisis. Science , 155 (3767), 1203–1207.10.1126/science.155.3767.1203

- Wilson, C. , & Wilson, G. T. (2015). Taoism, Shintoism, and the ethics of technology: An ecocritical review of Howl’s Moving Castle. Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities , 2 (3), 189–194.

- Wright, L. (2005). Forest spirits, giant insects and world trees: The nature vision of Hayao Miyazaki. The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture , 10 (1), 3–3.10.3138/jrpc.10.1.003

- Yamada, N. (2011). Why tour guiding is important for ecotourism: Enhancing guiding quality with the ecotourism promotion policy in Japan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research , 16 (2), 139–152.10.1080/10941665.2011.556337