Abstract

Large scale land acquisition has led to land related problems in many countries. Various studies have blamed chiefs as the primary cause of the problems associated with large scale land investments without critical analysis of their viewpoints on such land deals. This paper has therefore examined the challenges affecting chiefs in large scale land acquisitions by valuing their perspectives using jatropha investments and its transformation in Ghana. A mix of qualitative methods including interviews and review of documents on five large scale jatropha investment sites in Ghana was embraced. The findings of the study indicate that the problems in large scale land acquisitions are to be attributed to several actors connected to the land deals rather than blaming only the chiefs. The study has identified three key challenges affecting chiefs, which have resulted in problematic land deals: [i] state non-interference policy; [ii] insecure nature of land ownership; and [iii] land annexation by brokers. Based on the findings, the study recommends that measures need to be put in place to help value and tackle issues blaming chiefs as the cause of land related problems in Ghana. The findings also present lessons on the need for the state and other concerned stakeholders to develop comprehensive guidelines which inculcate third party lease contracts to guide chiefs’ decisions and actions in the lease of lands for large scale projects.

Public Interest Statement

The problems of large scale land acquisition have become enormous over the years especially in the developing countries. Such problems include rural land alienation due to tenure insecurity and conflicts. Usually, chiefs are blamed for such problems as they are considered as the custodians of land. This paper has examined the blame perspectives in tandem with the challenges affecting chiefs leading to such problems using cases of large scale Jatropha investments and their transformations in Ghana. The challenges are: the state refusal to interfere in chieftaincy issues, the insecure of land ownership by chiefs and the fear of land brokers taking over land transactions. The findings of the study present lessons on the need for Ghana and other developing countries to develop comprehensive guidelines to guide actions and decisions of chiefs in large scale land deals in order to tackle large scale land problems.

1. Introduction

Over the years, large scale agricultural investment has become an integral component of Ghana’s agricultural sector. This development has been attributed to the persistent rise in commodity prices on the international market, the strategic concerns of importing countries, the wide array of viable commercial opportunities within the agricultural sector and the presumption of large vacant lands in Ghana (Anseew, Alden-Wily, Cotula, & Taylor, Citation2012; Borras & Franco, Citation2012; FAO, Citation2012). In large scale land investments in Ghana, chiefs are key actors who are consulted by investors for land acquisitions (Yaro & Tsikatai, Citation2014). This has resulted in several concerns regarding the appropriation of lands for large scale investments such as jatropha at the expense of the rural poor (Campion & Acheampong, Citation2014) with chiefs becoming the main actors blamed for such land appropriations (Mamdani, Citation1996; Yaro & Tsikatai, Citation2014). Agricultural commercialisation has been perceived with mixed feelings. Whilst it is seen as a signal for agricultural modernisation and evolvement of the traditional land tenure, commercialisation is liable to the disenfranchisement of the land rights of many local members (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2012). This is because, it tends to manipulate the land rights of the rural members through a coercive mechanism with the quest to satisfy ideological desires of powerful actors, thereby worsening poverty and inequalities of affected individuals. Yaro and Tsikatai (Citation2014) have clearly indicated that through commercialisation, chiefs in Ghana appropriate the proceeds of land sales without due recognition of their people.

Why are chiefs blamed for land tenure insecurity in Ghana? Why these attributions to chiefs when problems on land acquisition come up? This paper makes a case that these problems are not to be attributed to only the chiefs but other several actors within the land sector. As part of its arguments, the paper considers land use decisions and third-party leasing contracts/risks, and how it contributed to the problems of large scale land acquisition. It should be noted that the primary intention of this paper is not to argue for chiefs and their attributed defects, but systematically explore the challenges which confront land stakeholders in the land market, with a special emphasis on the interaction between chiefs and other key land stakeholders; both Government and private institutions. Since the study is premised on jatropha investment and subsequent transformation, it became adequately relevant to provide appropriate context for the focus on jatropha. Hence, the literature on jatropha, its boom, bust and transformation has been discussed. Again, to better appreciate the driven occurrences on blames and challenges of chiefs, there was the need to understand the historical overview of chiefs’ legitimacy, authority and property rights from the pre-colonial to the current modern state government. This has also been discussed in the study.

2. Large scale jatropha investment: Its drivers, outcomes and transformation

In the early parts of the twenty-first century, jatropha became a prominent global agricultural crop (Cushion, Whiteman, & Dieterle, Citation2010). Several donors and development partners offered funding support for international and local NGOs and investors to venture into jatropha (Bassey, Citation2009). The specific drivers, outcomes of jatropha investment and subsequent transformation have been espoused in the subsequent sub-sections of the paper.

2.1. The drivers of large scale jatropha investment

Before global jatropha hype, it is well-known that the Olmeca people of Mexico planted jatropha for medicine in the thirtieth Century BC (Leonti, Sticher, & Heinrich, Citation2003). Later, the crop spread to other parts of the world through Portuguese seafarers (Henning, Citation2003). During that period, jatropha was used for domestic purposes until in the twentieth century where its potential as a biofuel crop was discovered (Nogueira, Citation2004). This gradually increased the interest of jatropha, which was then heightened in the twenty-first century due to the world’s increase in demand for energy and climate change concerns (Ariza-Montobbio & Lele, Citation2010). Climate change was a critical concern because the rising use of fossil fuel has increased the emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs), altering climatic conditions negatively (Birega, Citation2008; Sulle & Nelson, Citation2009). Ultimately, green-fuels were seen to as the solution to reduce the use fossil fuels whilst meeting the world’s energy needs with positive implications on climate. Consequently, jatropha stood tall among other biofuel crops such as sugar cane, oil palm, corn, and soy. This was because, several studies claimed jatropha could be successful on marginal lands (Graham, Gasparatos, & Fabricius,, Citation2014; Openshaw, Citation2000), and hence, food security and livelihood concerns will not be affected through competitions for productive lands. There were others including Ariza-Montobbio and Lele (Citation2010) who contended that jatropha was capable for reclaiming waste lands for agricultural purposes and when planted just once, it could yield oil for over 30 years. Jatropha was seen to have the potent for economic growth and rural livelihood transformation, apart from its perceived contributions to reducing energy poverty and enhancing environmental management and sustainability. As a result, Jatropha qualified for several enticing names including “wonder crop”, “marvellous crop” and “miracle crop” (Hill, Nelson, Tilman, Polasky, & Tiffany, Citation2006), which served as a source of motivation to drive its investment around the globe especially in Asia and Africa, where lands were perceived to be available (Deininger & Byerlee, Citation2011).

2.2. Outcomes and transformation of large scale jatropha investments

The outcomes of large scale jatropha investments were generally negative which subsequently led to a halt in several jatropha investments across the globe. It was highly expected that jatropha investment will have positive implications on food security and livelihood. But the reality was that jatropha investment rather exacerbated food security and livelihood (Tsikata & Yaro, Citation2011). Jatropha production led to the introduction of new pests and diseases which later affected food crops in many countries (Axlesson & Franzen, Citation2010; Rodriguez, Vazquez, & Gamboa, Citation2014). Again, food crop farmers stopped the cultivation of their crops, and joined some investors to produce jatropha (see Hinojosa & Skutsch, Citation2011; Rucoba, Munguía, & Sarmiento, Citation2012). This later dwindled total crop production affecting food availability. Though jobs were created by Jatropha investors, the local members recruited were exploited for their service with very limited compensation for work done (Timko, Amsalu, Acheampong, & Teferi, Citation2014). Though the use of marginal lands was tagged as suitable for jatropha; investors, especially in Africa, used fertile lands alienating local farmers of their lands, with very little or no compensations at all. In Ghana, Cotula, Vermeulen, Leonard, and Keeley (Citation2009) and Acheampong and Campion (Citation2013) identified that large scale jatropha investment has displaced farmers and other rural actors from their source of livelihood. There were also negative environmental outcomes and unfair distributions of compensations and benefits for displacement (Campion & Antwi-Bediako, Citation2013). In relation to investors, jatropha was highly unprofitable, as the cost of refinery was huge, making it not economically feasible for corporate investors (Axlesson & Franzen, Citation2010; Valero, Cortina, & Vela, Citation2011). The failure of jatropha as a global biofuel crop has currently led to investment transformations. Also, policy attention has shifted from jatropha (Brew Hammond, Citation2009), and large acres of acquired lands have either been taken over by new investors interested in other crops or jatropha investors have transformed their investments to other crops (ActionAid, Citation2012). In other areas, jatropha lands either lie idle or community members have taken over the land for agricultural purposes (Ahmed, Campion, & Gasparatos, Citation2017).

3. The history of chieftaincy and its incorporation in the modern nation-state

In Ghana, traditional leaders are accorded the needed respect and legal recognition because chieftaincy institutions embody the history of the people, their culture, laws and values, religion, and even remnants of pre-colonial sovereignty (Ray-Donald, Citation2003). The constitution of the Republic of Ghana recognises the power, responsibilities and legitimacy of the chiefs (Owusu-Mensah, Citation2014). Chiefs therefore play significant roles in the governance of the country, particularly in land administration and management. Before the colonial era, the chiefs were responsible for playing the legislative (law making), executive (law interpretation) and judiciary roles (law enforcement) in the country. The roles of the chiefs have however, been influenced by colonialism, civil and military regimes (Owusu-Mensah, Citation2014).

3.1. Pre-colonial era and chiefs’ authorities

In the pre-colonial time, chiefs were the main actors of the government machinery. They performed functions such as law making, law interpretation and execution as well as law enforcement. Though, the social and political systems of the pre-colonial period did not represent a “golden age”, these systems of social and political administrations revealed deep democratic systems and protection of individuals’ rights through customary/traditional networks of culture, values and traditions (Frimpong, Citation2006). The traditional leaders who held administrative and political powers were not influenced by external agents above their respective powers. They were deemed to have independent power and control over the management and administration of the country. For instance, land access and use was the prerogatives of every individual in the traditional area and was regulated by the traditional heads (i.e. chiefs, elders and families).

3.2. Colonial era and chiefs’ authorities

During the colonial era, the chiefs’ independent political and administrative power was mainstreamed into the administrative system of the colonial masters (the British). The British instituted “order in Council” 1 in 1856 which gave definitions to local laws, traditions, norms, values, practices and usage. One key legalisation of the traditional system during the colonial era was the institution of the Chiefs’ Ordinance in the year 1904. This legalisation supported the election, installation and removal of chiefs based on local customs (Owusu-Mensah, Citation2014). McLaughlin and Owusu-Ansah (Citation1994) asserted that the new administrative and centralised political system introduced by the British, integrated the control and management of local services, despite the fact that administration of services was predominantly delegated to the chiefs.

The modern state machinery which led to the rise of public bodies including the Judicial Council, the Legislative Council, the Gold Coast Police Force and the West Africa Frontier Force were created through the centralised system. These new bodies performed functions to support the chiefs in the various traditional areas. Resultantly, the traditional system and its functions were slowly merged into the new centralised colonial administrative structure, and the chiefs who were independent and autonomous in the pre-colonial era, came to apprehend the need for integration and co-operations with other traditional authorities and state institutions for sustainable and mutual benefits, unity and overall development (Owusu-Mensah, Citation2014)

3.3. Post—colonial era and chiefs’ authorities in modern nation-state

In post-colonial societies of West Africa, land is also seen as a form of political space and territory to be controlled both for its economic value and a source of leverage over other people (Berry, Citation2009). According to Ray-Donald (Citation2003), within the context of the post-colonial era, chiefs’ legitimate rights were supported during the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial eras. Various constitutions enacted over the years supported the operations of chiefs. In Nkrumah’s regime, the Chieftaincy Act 1961, Act 81 was passed which defined chiefs as individuals elected, installed or nominated in accordance with the local customs and laws and/or are identified and recognised by the responsible ministry for local government administration in the country (Ladouceur, Citation1974; Owusu-Mensah, Citation2014). The recognition of the Regional and National House of Chiefs and the roles they played were within the framework of the 1969 constitution. The institution of the Chieftaincy Act, 370 in Citation1971 as well as the passage of the current Chieftaincy Act in 2008 further recognises the powers and the roles of chiefs in the country. Article 270 (1) of the current 1992 Constitution of Ghana affirms and supports the mandate of chiefs to serve as the heads of their communities and to mobilise their people for development (Constitution of Ghana, Citation1992).

All customary lands in Ghana which constitute about 80% of the total lands in the country are vested in chiefs. The management of such lands is required to be done in accordance with the customs and traditions and reflections of the interest of the people who are ruled by their chiefs (Kasanga & Kotey, Citation2001; Larbi, Odoi-Yemo, & Darko, Citation1998; Ubink, Citation2008). The key state establishment with key roles to play within the framework of the land sector is the Land Commissions. The operations of the Lands Commission are recognised by the Lands Commission Act of 1994 (Act 483) and the current constitution of the country (Kasanga, Cochrane, King, & Roth, Citation1996; Lands Commission Act, Citation1994).

4. The traditional power structure in Ghana

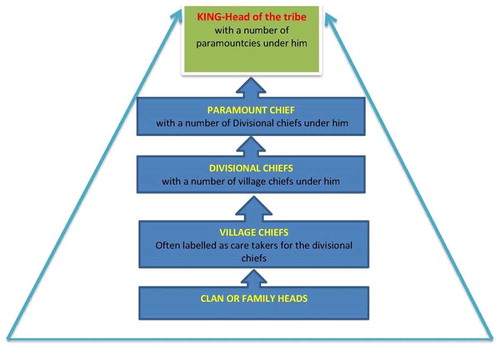

The 1992 Constitution of Ghana allows for temporary alienation via leasehold titling of customary lands. The management of lands in Ghana is characterised by regulations, market and customs, which define the complexities and controversies of how land sector institutions relate (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2012). Ghana has more than 32,000 traditional rulers identified under the National and the Regional Houses of Chiefs and these recognised rulers are under over 200 paramountcies which have considerable and respected power and influences in the country notably, the rural centres (Knierzinger, Citation2011). The structure of Ghana’s traditional leadership is hierarchical in nature. For example, among the Akan speaking people, the lowest form of authority is at the clan or family head (Abusua-panin) after which comes the “Odikro” (Sub-chief/care-taker chief). The “odikro” rules the community. This is followed by the divisional head (a chief in charge some number of communities or areas/villages) who also serves under the “Omanhene” known as the Paramount chief. At the topmost part is the overall head of the tribal group, for instance, the King of the Asante people. The king is in control of the paramountcies of that tribe. The roles of these leaders at the various levels of authorities include; serving as the custodians of their ancestral and community land; ensuring the continuity of culture, customs and traditions; initiating and championing development of their areas of operations; and maintaining law and order in their defined territories (Asumadu, Citation2006). The structure of the Traditional leadership is shown in Figure .

5. Chiefs’ legitimacy, authority and property ownership in Ghana

Chiefs derive their legitimate power from the citizens they govern and the state they dwell in. Legitimate sources like the constitution and traditional laws give chiefs the authority to govern and manage resources like land. According to Tyler (Citation2006), legitimacy is defined as a psychosomatic asset of power, agency or social arrangement that makes people to accept what is right, good and fair. Legitimacy is important but can also provide a platform for oppression and damage to others (Kelman & Hamilton, Citation1989). To the focus of this paper, resource (land) allocation and blames to the chief on the use of legitimate authority is in contention here. Hegtvedt and Johnson (Citation2000) suggest that “subordinates are more likely to tolerate certain levels of procedural injustice by strongly endorsed or authorised allocators”. Tyler (Citation2006) has also commented on legitimacy and resource allocation. From his perspective, the decisions/rules made by chieftaincy and any other institutions should be assessed and judged based on the criteria of legitimacy. People also put their own judgement of legitimacy through social arrangements and/or economic well-beings of such people. Anytime there arise diversities in social/economic well-being of people, questions about legitimacy are raised by the society. People therefore admit to the meritocratic explanations for economic inequality (Jost, Blount, Pfeffer, & Hunyady, Citation2003; Tyler, Citation2006). They also put blame for failure on individuals, not the system (Kluegel & Smith, Citation1986) and perceived societal status predicts judgements of competence (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, Citation2002). Studies by Lund (Citation2002), Sikor and Lund (Citation2009), Moore (Citation1988) and Lentz (Citation1998) have highlighted on legitimacy of authority in connection to resources and properties as well as the involvement of individuals and the state within the debate on legitimacy and authority. In the context of the debate on legitimacy of the chieftaincy institution, society will continue to blame chiefs using legitimate national policies/laws and their own legitimate judgement amidst the dwindling confidence in chiefs.

6. Methodology

6.1. Study settings

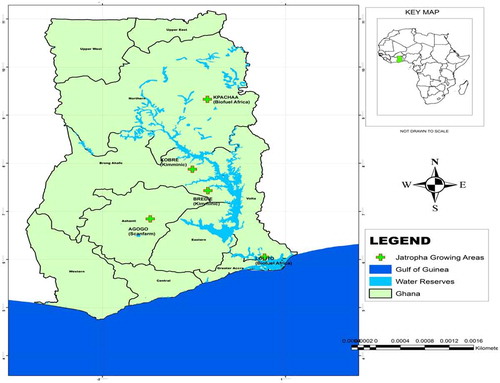

The study was carried out in five jatropha growing communities in Ghana. The communities were selected from each of three zones in the country; Southern or Coastal Savannah, Middle or Transition, and the Northern savannah zones. The selection of these communities/cases was influenced by three factors: (i) land deals are sanctioned by chiefs; (ii) jatropha investment projects involved large scale plantation models; and (iii) project areas have large number of migrant tenants and minority indigenes. The communities are Lolito, Agogo, Kobre, Bredi and Kpachaa. Lolito is located in the Coastal Savannah zone; Agogo, Kobre and Bredi are in the Transitional zone; and Kpachaa is in the Northern Savannah zone (see Figure ). Lolito is a community in the South Tongu District located 20 km away from Sagakope, the district capital. The major economic activities in the community are farming and fishing. Lands in the community are owned by the clans including the Agave, Fievie, Sokpoe, Tefle and Vume. Kobre is located in Pru District of the Brong Ahafo region. The community is about 20 km away from Yeji, the District capital. Bredi is located on the Ejura-Nkoranza road in the Nkoranza South Municipality, also, in the Brong Ahafo region. The community is about 50 km away from Nkoranza, the municipal capital. Agriculture remains the mainstay of the local economy of Kobre and Bredi. Agogo is located in the Asante Akim North District of the Ashanti region. Majority of the people are into agriculture. Lands in Kobre, Bredi and Agogo are owned by paramount chiefs in the trust of their people. Kpachaa is located in the Mion District in the Northern region of Ghana. Kpachaa is a patriarchal community, governed by the Dagbon Traditional System. The Divisional Chief oversees the land in the community for the Dagbon Kingdom. The locals are mainly engaged in farming activities.

6.2. Study design and sampling

The research design is a multi-case study based on five (5) jatropha communities in Ghana. The use of multi-case study helped the researchers in analysing complex number of issues. Since the study’s target population is widely diverse (made up of different group of respondents with diverse interests), the study design adopted made it useful to achieve the purpose of the study. The descriptive approach was used to present the findings of the study. In order to gain a more holistic understanding of the cases, a field survey was conducted in the selected sites to collect primary data. Secondary data were first gathered through institutional consultation and a literature review guided by a checklist of thematic issues of relevance to the research. The respondents interviewed in all study locations were: the chiefs, who are the central actors of this study; the elders, company workers, Assembly members, Unit Committee Chairman/members including farmers and public institutions. Non-probability sampling (snowballing and purposive techniques) was used to collect data from the respondents. The farmers and the workers were selected through snowballing whilst the traditional leaders, other local members (key informants) and public officials were purposively selected. The scrappy nature of the study population made it difficult to determine the sample size using any approved mathematical formular. Thus, the number of respondents the researchers were able to contact during the data collection became the estimated population for the study. In all, 350 respondents were enrolled made up of the chiefs, who are the central actors of this study; the elders, company workers, Assembly members, Unit Committee Chairmen/members, farmers and public institutions. Public officials were selected from the Districts’ Land Sector Agencies (LSAs). Out of the 350 respondents, 72 were from Agogo; Lolito, 108; Kpachaa, 55; Bredie, 70; and Kobre, 45. The companies in the five project sites were ScanFarm Company, formerly ScanFuel Company (Agogo), Biofuel Africa Company which was later transformed to Solar Harvest Company (Kpachaa), Kimminic Company Limited (Bredi and Kobre) and Biofuel Africa Company which has been replaced by the Brazilian Agro-Business Group (Lolito). Wide range of data were solicited from the respondents, from which several research papers were prepared, including this particular article.

6.3. Data instrumentation and analysis

Data for analysis were obtained from both secondary and primary data. The secondary data were obtained from public documents, journal articles and other research materials. The primary data were obtained through field exercise. During the exercise, the questionnaires were administered with the assistance of five trained field assistants recruited from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Ghana. The field assistants were responsible for completing the questionnaires based on their interactions with the respondents. The respondents were asked questions pertaining to the research objectives. Data obtained for the study were analysed qualitatively. The results and discussions are mainly secondary data, with some primary data to back and supplement the findings. Before the analysis, all data, both secondary and primary, were cross-checked/examined to ensure that data collected were true reflection of the issue examined in the study.

7. Results and discussions

7.1. Blame games: Chief’s legitimacy, authority and challenges in land deals

“Blame game” is a social process and was widely used in the 2000s when several individuals try to pin the roles of one another for some negative event, acting as blamers instead of “blamees”. The game involves two or more actors, involving, the blame makers and the blame takers. The blame makers are the group of people undertaking the blame action whilst the blame takers are the group who are being blamed by the blame makers (Hood, Citation2011; Knobloch-Westerwick & Taylor, Citation2008). Based on the legitimate power given to chiefs and government officials in Ghana, the author holds the position that those individuals in high positions in both traditional and government institutions are most likely to be traditionally and politically powerful to influence state policies to shape government and traditional activities. Based on the data collected, it was realised that three main issues affected the behaviour and administration of the traditional leaders (chiefs). These were: the state refusal to interfere in chieftaincy issues; the insecure nature of owning land; and the fear of land brokers taking over land transactions.

The discussions indicate that “blame game” is the focal issue in land deals, with the chiefs being blamed for doubtful land deals. But for an actor like the “chief” to be perceived as a cause of an event, the actor should have the dominant control over and bad intentions to cause such event (Weiner, Citation1985). It is thus necessary to indicate that an individual’s behaviour could lead to unfortunate outcomes but this might not emanate from the intention of such individual. If there are available laws to check chiefs’ sales and controls over lands, one could hold this against a chief and claim that he should have taken precautions, implying that he had control over the problem. For example, the case in Ghana indicated that the chiefs in all the jatropha investment sites had no bad intention but have been regarded to have “caused” the dispossession and loss of livelihood (See Campion & Acheampong, Citation2014). Specifically, in Agogo, the Land Management Chief confirmed to the good intention of the Traditional Council for the lease of the land to start the jatropha project.

We had the intention that the jatropha project will transform our communities and improve livelihoods. The Omanhene called for a meeting to inform and seek the approval of our people. Everyone agreed that the project was good before the investors were allowed to operate. It was however, unfortunate that the media, some community members and Civil Society Groups tagged us as the cause of the land problems which emanated from the jatropha project.

We went into agreement with the chief and the community to lease the land to us for fifty years subjected to 25 years of renewal. Management did not have any difficulties during the negotiation process since the Chief realised that the project was good for his people.

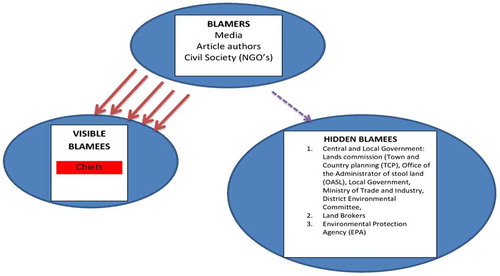

Also, in some investment centres, it was identified that some naive chiefs were influenced by middlemen (brokers) to release large tracts of land to them who later transferred the land to investors with the quest to make an avalanche of profit. In such situation, the dispossession of land leading to the loss of livelihood was not the intention of the ignorant chiefs but they are still blamed and held responsible for such problem. This was exactly found in Lolito investment site. The land owning clan (Tsiala clan) had no idea about the intention of an indigene (middleman), who indicated his interest in the land. The recognition that the middleman was an indigene was enough for the clan to give out the land on the basis that an indigene (tribe mate) will utilise the land in the interest of other members of the surrounding communities. However, the elite middleman had in-depth knowledge and information about the proposed jatropha investment (information asymmetry), and acted on it as an advantage to gain more profit from the investment instead of the interest of his fellow indigenes. Resultantly, the middleman (broker) entered into an agreement with the jatropha company, and leased the land at a higher cost. Prior to the lease, some portions of the land acquired by the investor was used for farming. There were also community members who used the land as cattle grazing field, ground for both firewood for fuel and raffia for mat-weaving. All these local livelihood sources were affected after the land was utilised for large scale Jatropha. Due to the failure of Jatropha, the Jatropha Company by name Biofuel Africa left the land. The middleman subsequently leased the same land to another investor, Brazilian Agro Business Group who has currently transformed the Jatropha investment to large scale rice plantations. Despite acting intentionally on information asymmetry to his advantage leading to the negative returns associated with the investment, he still remains as an invisible “blamee” (see Figure ). The middleman is however, one important actor who needs to be blamed for the problems emanating from the investment. A focus group discussion session with the land owner clan affirmed to the influence of a middle man, who led the entire jatopha transaction for the investors.

We leased 2,300 hectares of land to Biofuel Africa Company through a middleman. We the elders did not know the kind of arrangement he [middleman] made directly with the jatropha company but we have gathered that he gave the land to the company at a higher cost. We trusted him to act in the interest of the community members since he is an elite, but he has disappointed us.

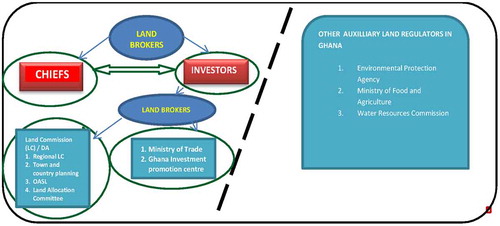

Data collected from the investors at the project sites revealed that during large-scale land acquisition processes, the necessary stakeholder consultation with the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MoTI) and the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC) was undertaken. GIPC further directed the investors to the chiefs for their consent and involvement in the acquisition processes. The investors then visited the chiefs and discussed with them their interest to invest in their communities. The visits were characterised by “drink money” indicating their acknowledgement of the chiefs’ ownership to the proposed land and their due allegiance to the power of the traditional leaders on their people. The acceptance of the “drink money” in the local context is regarded as necessary to “open the gate” for further negotiations on the land to begin. The negotiation involved the investors and the chiefs and issues discussed were the cost to be recovered on the land, the area/size of the land to be acquired and the period of investment or use of the land. In the three study sites (Agogo, Bredi and Kobre) in the middle/transition zone, the investors indicated that the traditional custom of pouring libation was done to invoke the blessings of the gods into the land deal. Once all terms were agreed upon, an indenture was prepared to signify the conclusion of the land deal. The investors obtained land title from the Lands Commission and as well registered their businesses with GIPC. The EPA, and in some cases, the Water Resources Commission (WRC) were contacted by investors for Environmental Impact Study and the issuance of permits (environmental and water permits). The investors thus, passed through all the processes required for investment in Ghana’s economy. It could be inferred that the necessary stakeholder consultation was undertaken to acquire the lands for the jatropha investment, which according to Bryson (Citation2004), is very necessary in order to gather support from all concerned stakeholders. The consultations also make the project attractive to the all stakeholders and help to assess their capability to ensure effective implementation (Poveda & Young, Citation2015). Since the jatropha projects passed through the right channel and all stakeholders were consulted, the study holds the stand that the concerned institutions should be held accountable for problems associated with the jatropha project since they had the expertise to have critically examined the viability and the implications of the investment before giving the investors the go ahead. The fact that jatropha investment failed and had negative implications, for instance, on the environment, implies that the institutions (for example; EPA) failed to do what were expected of them. The chiefs in their local communities do not have the “technical knowledge” to foresee that such investments will generally impact negatively on their community members. It is thus, very unfair for the chiefs to be blamed solely for the negative outcomes of jatropha projects especially concerning the leasing of lands for such investments. Figure gives a clear picture of the jatropha investment’s blame games which have been created as a result of the poor development outcomes of the investment.

7.2. The challenges affecting chiefs’ behaviour in land deals

7.2.1. The policy of non-interference

The policy of non-interference of state bodies in chiefly matters has contributed to the jatropha land use problems in all the five investment destinations. The Chieftaincy Act of Citation1971 (Act 370) for instance, indicates that the state should not interfere in chieftaincy matters concerning land deals. In connection with the provision of the Act, data collected from the Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD) of the South Tongu District (Volta region) highlighted that [quote]:

Within the context of our system of operations here, accountability is perceived to exist and that we the officials of this unit at the district level have no mandate to “destool” the chief. Again, we cannot force the chiefs to be accountable because land issues are chiefs’ things and not we the district officials.

During an interview with the Chief and Elders of Kobre investment site (Brong Ahafo region), this was their general contribution:

The government has not assisted us in land negotiations and dealings …. this has contributed to the problems associated with the large scale investment by the jatropha companies.

Government has failed to assist us in land negotiations. Officials just direct the investors to us to engage with them. The investors also come with enticing packages for our development. Hence, we just engage them on our own in order to promote local development.

Discussions with the paramount chief of Nkoranza Traditional Council (Bredi Project site) and the Unit Committee Chairman of Bredi electoral area indicated that the lack of effective involvement of government land actors in land deals was due to political reasons. As various politicians demand support from some of the influential traditional leaders, successive governments have been soft to deal with land issues. This according to Knierzinger (Citation2011) is quite worrisome since some chiefs are highly educated and government can work hand in hand with them to initiate various land reforms to transform the antediluvian land customs which retard economic growth and development in Ghana. In line with Knierzinger (Citation2011) stance, the study identified that the paramount chief of Agogo for instance who approved lease agreements for ScanFarm Limited, is a lawyer and a former minister who has impeccable knowledge on property rights in Ghana, but never acted on those rights in the acquisition process.

Paramount Chief of Nkoranza Traditional Council (Bredi investment site in the Brong Ahafo region) also confirmed by saying:

Some of the chiefs have acquired education to the highest level, but they still enter into dubious transaction for their own gains within the framework of existing customs and norms”. We from Nkoranza Traditional Council gave out land for the betterment of our people. Those who were dispossessed and recognised by the council were given alternative lands.

An officer of the Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD) in South Tongu District (Lolito investment site in Volta region) also explained that:

In some instances, some chiefs come to obtain site plans with their clients. Some of these clients (majority) find that the cost involved in regularizing their lands sometimes becomes more expensive than the real cost of the lands. Other projects, especially commercial agricultural projects do not fall within any existing plans. Thus, on the client’s demand, the Assemblies may be engaged to provide cadastral maps for such projects. However, the chiefs are mostly not motivated to do so due to the tedious process of getting lands regularised.

Due to the lack of consultation between the Assemblies and the chiefs who give off lands, it becomes difficult to track some of these investment projects for effective revenue collection. We have no power to interfere but to hope that the chiefs undertake deals for the benefit of the local communities.

7.2.2. Fear of Insecurity to land ownership system

The study also revealed a challenge of “fear of insecurity to land ownership system” in the five jatropha sites researched. Customary Land Secretariats, created to ensure effective local land management by supporting the chiefs, give clear understanding of where the chief derives their authority from (Toulmin, Brown, & Crook, Citation2004). As indicated by Ubink (Citation2008), the constitution of Ghana recognises the power and authority of chiefs in the country. However, in some cases, fear arose that chiefs could lose their authority through the loss of land rights. Chiefs expressed two major concerns; the fear of losing boundary to other paramountcies and fear of land “take-overs” by migrants.

7.2.2.1. Fear of losing boundary to other paramountcy

The formalised presumption of formal boundaries of stool lands to avert potential future land litigations as claimed by chiefs is what they have been informed through oral history. The issue is compounded by the problem of the rarity of formal records on location and size of stool land. Though, this problem exists, the chiefs confidently assert to know their boundaries (Berry, Citation2009). Chiefs and their subjects (indigenes) by virtue of their allodial land rights, came to the localities/villages and made claims to most available land using physical features such as rivers, river valleys and huge trees as the boundaries of the lands (interviews at all the study sites). The allocations of lands in the country affected the areas of some paramountcies due to the difficulties of tracing boundaries. Reference to identity then became the strategy by residents and chiefs to either legitimise or undermine claims based on custom. For example, the Nkoranza Traditional Council which is endowed with vast land areas claimed to have lost track of the actual size of stool land areas, as non-permanent features such as rivers and valleys were used to mark land boundaries (Field Interview with Chief of Nkoranza). The Ejura Traditional Council was accused to have occupied some portions of land belonging to the Nkoranza Traditional Council. This has the tendency of resulting in clashes between the two traditional authorities. The Authorities (chiefs and elders of the Nkoranza Traditional Council) indicated that:

……………Ejura Traditional Council has given authority to migrants to use our lands. This additionally influenced us to give all these lands to proper investors.

The chief and elders of Kobre, where Kimminic Company Limited operated had similar boundary conflict:

The company, Kimminic Company Limited, moved to a neighbouring/boundary community made up of the people of Konkomba instead of coming to us. They negotiated on the land, put pillars and performed traditional prayers which opened the gate for the company to start its operations. The acquired land, however, is property of the people of Kojobofour traditional area instead of the Konkomba traditional area. The chief of the Konkomba traditional area who was involved in the negotiation process has passed away. Our chief (Kojobofour traditional area) as at that time is also dead. The company never officially informed us about their operations. The land acquired was about 36,000 acres but not all were used. The company continued to expand its area under cultivation and when the company brought its machinery to start operation, we stopped them. This is because; I, the Odikro, did not know about them. It was later we learnt that they got the permission from the chief of Konkomba. We learnt the land was not sold but leased with an agreement that the community gets 25% of the oil. This was from hearsay.

7.2.2.2. Fear of annexation by migrants

Small scale farming is bedrock for Ghana’s development and this has attracted a lot of people, especially, migrants who move in areas to acquire land for small scale farming activities. The involvement of migrants in small scale farming serves as their safety nets and economic support to withstand the difficult economic conditions in the country (MASDAR Cocoa Board, Citation1998). Again, the economic requirements for the cultivation of long term/ cash crops are huge and such cultivation requires permanent land tenure which is unintended on family lands in the country (Awanyo, Citation1998). Small scale farming requires land and whereas the indigenes obtained their lands through inheritances, non-indigenes had to undergo negotiation process to obtain land for use. One interesting revelation during the field work in the project sites was that in the land acquisition process by migrants, they (migrants) held the perspective that making payment on land was a sign of land ownerships. But in the context of Akan’s (indigenes) customs and norms, there is separation between land and the use of the land (what is grown on such lands). This diversity can cause conflicts between the indigenes and the migrants concerning land ownership and dealings at some instances (Amanor, Citation2007; Knudsen & Fold, Citation2011).

All the chiefs in the study sites legitimised their land claims based on reference to citizenship identity and as first-settlers. They claimed that migrants lack local-citizenship identity and that, their lands are only protected through the goodwill of the chiefs. The chiefs in the study sites generally argued that unclear land boundary demarcations and the gradual influx of migrant farmers into the areas pose potential threats to chiefs’ authority over stool lands. For instance, in Kobre and Bredi, one of the paramountcies responded that the migrants’ alliance with some Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) to contest for lands illustrates the uncertainty linked with migrants’ ability to take over their lands. According to the chiefs and elders of the paramountcy, previous experiences of land leases to migrants led to the permanent stay of migrants on their lands who have installed their own chiefs and claim allegiances to adjoining paramountcy, especially during the jatropha boom and acquisition of land (Field Interview with Paramount Chief of Nkoranza Traditional Area).

For fear of losing land to migrants, some chiefs resorted to strategically give out receipts of payment for land allocation without agreement to spell out conditions on farm for the migrant farmers:

All migrant farmers were asked to show receipts of payments of ground rent as approval to their observance of custom guiding the use of stool land ........................... Small leases with “drink money” usually lead to occupation by migrants. You cannot ask them to leave even if intended projects are not successful. But the reversal of the land to the chiefs is possible with the joint venture agreement with large-scale jatropha investors. (Field Interview)

7.2.3. Land annexation by brokers

The insecurity of people on customary lands does not stem from the lack of registration, rather from a deterioration of customary rights, as customary norms are changing “to support an elite capture of majority interests” (Wily & Hammond, Citation2001). The flexibility and weaknesses in the chieftaincy institutions enable land brokers or “middlemen” like “outsiders” or “social climbers” to take over mediation and subsequently, annexe land deals. This occurs through third party lease contracts involving chiefs acting with investors through brokers. As indicated by Cotula (Citation2011), land contracts are signed between two parties, but tend to consider a wider range of land players. In the light of large scale projects, the contract outlines the terms of the project, as well as the manner in which risks, costs and benefits are distributed. In all the five previously Jatropha investment sites visited, chiefs acted on brokers (indigenes) as a third party to facilitate successful outcomes of land negotiations with investors. The lease contracts facilitated by third parties were enticing as investors made vague promises in terms of job creation, infrastructural provisions and co-benefits of investment for local development. With good intention for development, chiefs accepted investors’ offer for land use decisions. In Kpachaa and Agogo particularly, the contracts review further involved consultation and agreement with the people to seek their consent. However, contracts only work when they are properly implemented (Cotula, Citation2011). The presence of a third-party (broker); highly motivated by profit to bring in an investor due to chiefs’ incapability to carry out development projects, meant that local livelihood and sustainability were rated below the interest of the broker. This was obvious in Lolito area of the South Tongu District. The broker was able to influence the land owning clan to lease the land to him for 50 years, who in turn sublet the land to Biofuel Africa, a Norwegian Company for an undisclosed number of years. He successfully holds the land in a fiduciary capacity for 50 years now and not accountable to the members of the land owning clan for the next 50 years. After the burst of Jatropha, the broker has subsequently lease the land to another investor for large scale rice plantations. As indicated by Bierschenk, Chauveau, and De Sardan (Citation2002), the person concerned as broker is very important as to whether he/she can really be trusted as a suitable third party who will act in accordance with the interest of the community and the investors concerned.

In all the selected communities for the study, farmers have lost their lands for various reasons: tenure insecurity on their lands; land broker’s interferences; the lack of power to confront the chiefs during the acquisition processes of the land for jatropha investment; and their weakness and limited negotiation power for commensurate compensations. In Kobre, for instance, one of the operational areas of Kimminic Company Limited, the elders indicated that:

The company brought their working machinery and equipment when we were not even aware of the operations as well as the land negotiation processes followed by the company. This made us to drive the company away from operating in the community. The company indicated that they contacted someone from Accra, the nation’s capital, but we had no knowledge about such person. The chief of the community who resides in Accra later came to the community and revealed his lack of knowledge concerning the operations and negotiation processes of the company. (Field Interview with Chief and elders of Kobre, Transition zone)

Table 1. Land acquisition process and involvement of chiefs/middlemen (brokers)

8. Conclusions and recommendations

The results of the study are based on a variety of cases on chiefs and on situational observations. The paper revealed three main confronting issues affecting land deals in the study sites. They are: the policy of state non-interference in chiefly matters; insecure nature of owning land; and fear of annexation by land brokers. These challenges impeded the successful operations of traditional leaders (the chiefs) and made them the main focal “blamees”. It was revealed that the influences and approaches from successive governments and chiefs resulted in the three aforementioned challenges. These challenges and corresponding attributions showed that understanding the way events are described can alter the way scholars perceive their next line of action to either stigmatise or favour a stakeholder in the centre of the discourse. When a chief’s action relative to an event is described using an active voice, that chief is more seen as the cause of the event than when passive voice is used to describe the same event. These attributions, in turn, have important implications for policy preferences. The researchers conclude that the sources of information influence largely the outcome of what people perceive as readers (including, NGO’s, Policy makers, International community) and form their own impression on whose actions result in, for example, land dispossession. It was further observed that there is also a bigger system influencing these challenges expressed by chiefs. The current laws that spell out the roles of both the chieftaincy and government institutions have not been effectively enforced in the country. Therefore, the criticisms about failure on land deals have often been put on chiefs in lieu of the defective national system of chieftaincy. Though chiefs can be blamed for such negative outcomes, the system should also be blamed for also creating the opportunity for chiefs to have the negative impact they have on land issues. There should be no opportunities for the chiefs to mismanage land that have been entrusted to their care. The study calls for strict enforcement of laws governing land administration and governance. Also, the roles of various stakeholders should be clearly spelt out and they should be fully equipped to deliver on their mandates to deal with the challenges of the sector. It is also recommended that all relevant stakeholders such as the Ministry of Trade, Town and Country Planning Department, chiefs, farmers, NGOs and other development partners collaborate to ensure sufficient outcomes of large scale investment on local livelihoods. The paper also presents lessons on the need for the state and other land stakeholders to develop comprehensive guidelines that guide chiefs’ decisions and actions in the lease of lands for large scale investments. This guideline should include details of third party contracts on the lease of lands for investments. The conclusion of the study also creates an ultimate opportunity for future research. Future studies should pay attention to the contributions of media exposures to the causal attributions of the chiefs and how such exposures have influenced the perceptions of blamers. Given the complexity of individuals’ impressions, the authors’ standpoint is: the rational processes discussed in the paper require unique search and examination (scrutiny) on future studies directed to chiefs and land deals.

8.1. Notes for effective understanding of the study

| (1) | Migrants: These are people or households who have the rights to use land which has been negotiated through private arrangement with landlords and/or chiefs. | ||||

| (2) | Land dispossession is simply losing part or whole of one’s farmland. | ||||

| (3) | “Blamees”: They are persons blamed and are to be seen as the wrong doer in land deals. In the context of this articles “blamees” (mainly the chiefs) are persons who are blamed for something that is not wholly their fault, especially because someone else wants to avoid being blamed. | ||||

| (4) | National House of Chiefs: This is made up of five traditional rulers who are elected among ten leaders who represent each region in the country. The National House of Chiefs has president and vice president who are elected among themselves. The Chiefs are constitutionally backed. | ||||

| (5) | In general discussion, a nation-state is variously called a “country,” a “nation,” or a “state.” Modern Nation state refers to an emerging colonial control state to an independent “self-governing” state. | ||||

| (6) | Drink Money-This entails drinks which are presented to chiefs during land acquisition from them. It shows a sign of respect and recognition to the chiefs’ concerned. The drink is poured out to ancestors in the form of libation to invoke the blessings of God for the transaction and the use of the land. | ||||

Funding

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research [grant number W07.68.305.00].

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richmond Antwi-Bediako

Richmond Antwi-Bediako is currently a PhD student at Utrecht University of the Netherlands. He has interest in environment, energy, climate change, land, conflict and local development. He has worked as an Environment and Development consultant for over 20 years and has presented papers in international conferences and seminars. He has been involved in researches in West and East Africa.

Notes

1. Order in Council is a type of legislation instituted in countries, notably the Commonwealth member states. In UK, the legislation is made formally in the name of the Queen by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (Queen-in-Council).

References

- Acheampong, E. , & Campion, B. B. (2013). Socio-economic impact of biofuel feedstock production on local livelihoods in Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography , 5 , 1–16.

- ActionAid Ghana . (2012). Land grabbing, biofuel investment and traditional authorities in Ghana: Policy brief . Ghana.

- Ahmed, A. , Campion, B. B. , & Gasparatos, A. (2017). Biofuel development in Ghana: Policies of expansion and drivers of failure in the jatropha sector. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews , 70 , 133–149.10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.216

- Amanor, K. S. (2007). Conflicts and the reinterpretation of customary tenure in Ghana. In B. Dorman , R. Odgaard , & E. Sjaastad (Eds.), Conflicts over land and water in Africa (pp. 33–59). Oxford: James Currey.

- Anseew, W. , Alden-Wily, L. , Cotula, L. , & Taylor, M. (2012). Land rights and the rush for land: Findings of the global commercial pressures on land research project . Rome: International Land Coalition.

- Ariza-Montobbio, P. , & Lele, S. (2010). Jatropha plantations for biodiesel in Tamil Nadu, India: Viability, livelihood trade-offs, and latent conflict. Ecological Economics , 70 , 189–195.10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.05.011

- Asumadu, K. (2006). The role of traditional rulers in Ghana’s socio-economic development . Retrieved from http://www.modernghana.com/news/118850/1/the-role-of-traditional-rulers-in-ghanas-socio-eco.html

- Awanyo, L. (1998). Culture, markets, and agricultural production: A comparative study of the investment patterns of migrant and citizen cocoa farmers in the Western Region of Ghana. The Professional Geographer , 50 (4), 516–530.10.1111/0033-0124.00136

- Axlesson, L. , & Franzen, M. (2010). Performance of Jatropha biodiesel production and its environmental and socio-economic impacts-A case of Southern India, a Master’s of science thesis submitted for the degree programme in Industrial Ecology . Sweden: Department of Energy and Environment, Chalmers University of Technology.

- Bassey, N. (2009). Agrofuels: The corporate plunder of Africa. Third World Resur , 223 , 21–26.

- Berry, S. (2009). Property, authority and citizenship: Land claims, politics and the dynamics of social division in West Africa. Development and Change , 40 (1), 23–45.10.1111/dech.2009.40.issue-1

- Bierschenk, T. , Chauveau, J. P. , & De Sardan, J. (2002). Local development brokers in Africa: The rise of a new social category . Inst. für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien.

- Birega, G. (2008). Agrofuels beyond the hype: Lessons and experiences from other countries. In T. Heckett & N. Aklilu (Eds.), In agrofuel development in Ethipia: Rhetoric, reality and recommendations (pp. 67–83). Addis Ababa: Forum for Environment.

- Borras, S. M. , & Franco, J. C. (2012). Global land grabbing and trajectories of Agrarian change: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Agrarian Change , 12 (1), 34–59.10.1111/joac.2012.12.issue-1

- Brew Hammond, A. (2009). Bioenergy for accelerated agro-industrial development in Ghana. Keynote address delivered on behalf of Ghana energy minister for energy at the Bioenergy markets, West Africa Conference, Accra.

- Bryson, J. M. (2004). What to do when stakeholders matter: Stakeholder identification and analysis techniques. Public Management Review , 6 (1), 21–53.10.1080/14719030410001675722

- Campion, B. , & Acheampong, E. (2014). The chieftaincy institution in Ghana: Causers and arbitrators of conflicts in industrial jatropha investments. Sustainability , 6 (9), 6332–6350. Retrieved from http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/6/9/6332 doi:10.3390/su6096332.

- Campion, B. B. , & Antwi-Bediako, R. (2013). The seed fuel wars of Africa: Biofuel conflicts in Ghana and Ethiopia. The Broker Online , 1–4. Retrieved from http://www.thebrokeronline.eu/Articles/The-seed-fuel-wars-of-Africa

- Cotula, L. (2011). Land deals in Africa: What is in the contracts? London: IIED.

- Cotula, L. , Vermeulen, S. , Leonard, R. , & Keeley, J. (2009). Land grab or development opportunity? Agricultural Investment and International land deals in Africa . London: IIED/FAO/IFAD. ISBN: 978-1-84369-741-1

- Cushion, E. , Whiteman, A. , & Dieterle, G. (2010). Bioenergy development: Issues and impacts for poverty and natural resource management . Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

- Deininger, K. , & Byerlee, D. (2010, October). The rise of large-scale farms in land-abundant developing countries: Does it have a future. In Conference Agriculture for Development-Revisited, University of California at Berkeley (pp. 1–2).

- Fiske, S. T. , Cuddy, A. J. C. , Glick, P. , & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 82 , 878–902.10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

- Food and Agricultural Organisation . (2012). The state of food and agriculture: Investing in agriculture for a better future . Rome: Author.

- Frimpong, A. K. D. (2006). Chieftaincy, democracy and human rights in pre-colonial Africa: The case of the Akan system in Ghana. In I. K. Odotei & A. K. Awedoba (Eds.), Chieftaincy in Ghana: Culture, governance and development (pp. 11–26). Accra: Sub-Sahara Publishers.

- Graham, V. M. , Gasparatos, A. , & Fabricius, C. (2014). The rise, fall and potential resilence benefits of Jatropha in Southern Africa. Sustainability , 6 (6), 3615–3643. doi:10.3390/su6063615

- Hegtvedt, K. A. , & Johnson, C. (2000). Justice beyond the individual: A future with legitimation. Social Psychology Quarterly , 63 , 298–311.10.2307/2695841

- Henning, R. K. (2003). The jatropha booklet: A guide to jatropha promotion in Africa (pp. 5–33). Weissensberg: Bagani GbR.

- Hill, J. , Nelson, E. , Tilman, D. , Polasky, S. , & Tiffany, D. (2006). Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences , 103 (30), 11206–11210.

- Hinojosa, F. I. D. , & Skutsch, M. (2011). Impacto de establecer Jatropha curcaspara producir biodiesel, en tres comunidades de Michoacán, México, abordado a partir de diferentes escalas. Revista Geográfica de América Central , 2 , 1–15. (In Spanish)

- Hood, C. (2011). The blame game: Spin, bureaucracy, and self-preservation in government . Princeton, NJ: Publisher University Press. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=664551

- Jost, J. T. , Blount, S. , Pfeffer, J. , & Hunyady, G. (2003). Fair market ideology: Its cognitive-motivational underpinnings. Research in Organizational Behavior , 25 , 53–91.10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25002-4

- Kasanga, R. K. , Cochrane, J. , King, R. , & Roth, M. (1996). Land markets and legal contradictions in the peri-urban area of Accra, Ghana: Informant interviews and secondary data investigations (p. 83). LTC Research, Paper 127. Madison: Land Tenure Centre.

- Kasanga, K. , & Kotey, N. A. (2001). Land management in Ghana: Building on tradition and modernity (p. 34). London.: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Kelman, H. C. , & Hamilton, V. L. (1989). Crimes of obedience . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Kluegel, J. R. , & Smith, E. R. (1986). Beliefs about inequality . Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Knierzinger, J. (2011). Chieftaincy and development in Ghana: From political intermediaries to neo traditional development brokers . Arbeitspapiere des Instituts für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien der Johannes Gutenberg- Universität Mainz (Working Papers of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz), 124. Retrieved from http://www.ifeas.uni-mainz.de/workingpapers/AP124.pdf

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S. , & Taylor, L. (2008). The blame game: Elements of causal attribution and its impact on siding with agents in the news . Sage. Retrieved from http://crx.sagepub.com/content/early/2008/10/07/0093650208324266 doi:10.1177/0093650208324266

- Knudsen, M. H. , & Fold, N. (2011). Land distribution and acquisition practices in Ghana’s cocoa frontier: The impact of a state-regulated marketing system. Land Use Policy , 28 , 378–387.10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.07.004

- Ladouceur, P. A. (1974). Chiefs and politicians: The politics of regionalism in northern Ghana (p. 35). London: Longman.

- Larbi, W. O. , Odoi-Yemo, E. , & Darko, L. (1998). Developing a geographic information system for land management in Ghana . GTZ.

- Lentz, C. (1998). The chief, the mine captain and the politician: Legitimating power in Northern Ghana. Africa , 68 (1), 46–65.10.2307/1161147

- Leonti, M. , Sticher, O. , & Heinrich, M. (2003). Antiquity of medicinal plant usage in two Macro-Mayan ethnic groups (Mexico). Journal of Ethnopharmacology , 88 , 119–124.10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00188-0

- Lund, C. (2002). Negotiating property institutions: On the symbiosis of property and authority in Africa. In K. Juul & C. Lund (Eds.), Negotiating property in Africa (pp. 11–43). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of colonialism . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- MASDAR . Cocoa Board Ghana. (1998). Socio-economic study . Final report. Berks: Author.

- McLaughlin, J. L. , & Owusu-Ansah, D. (1994). “Colonial administration”. Compile into a hand book. La Verle, Berry. “Ghana: A country study.” In Federal Research Division . Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

- Moore, S. F. (1988). Legitimation as a process: The expansion of government and party in Tanzania. In R. Cohen & J. D. Toland (Eds.), State formation and political legitimacy (pp. 155–172). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

- Nogueira, L. A. H. (2004). Perspectivas de un Programa de Biocombustibles en América Central . México: CEPAL/GTZ.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2012). Neoliberalism and the urban economy in Ghana: Urban employment, inequality, and poverty. Growth and Change , 43 , 85–109. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.2011.00578.x

- Openshaw, K. (2000). A review of Jatropha curcas: An oil plant of unfulfilled promise. Biomass and bioenergy , 19 (1), 1–15.

- Owusu-Mensah, I. (2014). Politics, chieftaincy and customary law in Ghana’s fourth Republic. Journal of Pan African Studies , 6 (7), 261.

- Poveda, C. S. , & Young, R. (2015). Potential benefits of developing and implementing environmental and sustainability rating systems: Making the case for the need of diversification. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment , 4 (1), 1–11.10.1016/j.ijsbe.2014.12.003

- Ray-Donald, I. (2003). Ghana: Traditional leadership and rural local governance. Grassroots Governance? Chiefs in Africa and the Afro-Caribbean , 1 , 83–122.

- Rodriguez, O. A. V. , Vazquez, A. P. , & Gamboa, C. M. (2014). Drivers and consequences of the first Jatropha Curcas plantations in Mexico. Sustainability , 6 , 3732–3746. doi:10.3390/su6063732.

- Rucoba, G. A. , Munguía, G. A. , & Sarmiento, F. F. (2012). Entre la Jatropha ylapobreza: Reflexiones sobre la producción de agrocombustibles en tierras de temporal en Yucatán. Estudios Sociales , 21 , 115–142. (In Spanish)

- Sikor, T. , & Lund, C. (2009). Access and property: A question of power and authority. Development and Change , 40 (1), 1–22.10.1111/dech.2009.40.issue-1

- Sulle, E. , & Nelson, F. (2009). Biofuels, land access and rural livelihoods in Tanzania . London: IEED.

- The Constitution of Republic of Ghana . (1992). Accra: Assembly Press.

- The Republic of Ghana: Lands Commission Act . (1971). Act 362.

- The Republic of Ghana: Lands Commission Act . (1994). Act 483.

- Timko, J. A. , Amsalu, A. , Acheampong, E. , & Teferi, M. K. (2014). Local perceptions about the effects of Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) and Castor (Ricinus communis) plantations on households in Ghana and Ethiopia. Sustainability , 6 , 7224–7241. doi:10.3390/su6107224

- Toulmin, C. , Brown, D. , & Crook, R. (2004). Project memorandum: Ghana land administration project, institutional reform & development: Strengthening customary land administration . Accra: DFID-Ghana.

- Tsikata, D. , & Yaro, J. (2011). Land Market Liberalization and Trans-National Commercial Land Deals in Ghana since the 1990s. Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, 6-8 April. Retrieved from http://www.iss.nl/fileadmin/ASSETS/iss/Documents/Conferencepapers/LDPI/33_Dzodzi_Tsikata_and_Joseph_Yaro.pdf.

- Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology , 57 , 375–400.10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

- Ubink, J. (2008). In the land of the chiefs: Customary law, land conflicts, and the role of the state in Peri-Urban Ghana . Thesis to afford the degree of Doctor at the University of Leiden, on the authority of the Rector Prof. Mr. P. F. van der Heijden, according to the decision of the Doctorate defend on Wednesday, March 5, bell 16.15.

- Valero, P. J. , Cortina, V. S. , & Vela, V. S. (2011). El proyecto de biocombustibles en chiapas: Experiencias de los productores de piñón (Jatropha curcas) en el Marco de la crisis rural. Estudios Sociales , 19 , 120–144. (In Spanish).

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review , 92 (4), 548–573.10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

- Wily, L. A. , & Hammond, D. (2001). Land security and the poor in Ghana: Is there a way forward? A land sector scoping study . Summary commissioned by UK DFID Ghana’s Rural Livelihood Programme.

- Yaro, J. , & Tsikatai, D. (2014). Neo-traditionalism, chieftaincy and land grabs in Ghana . This Policy Brief was written by Joseph A. Yaroi and Dzodzi Tsikatai for the Future Agricultures Consortium. Editors- Paul Cox and Beatrice Ouma. Retrieved from www.future-agricultures.org