Abstract

Dealing with Islamic extremism without considering the meaning and context of the term itself leads to a narrow understanding of the phenomenon and its implications. This has led to describing Islamic extremism in terms such as “terrorism” and “Islamic radicalisation” which require reactive interventions (such as counter-terrorism and military measures) by governments to combat this form of extremism. Analysing its context provides additional insight on possible solutions to combat extremism in general and Islamic extremism in particular. This may prompt measures taken by governments to secure a more sustainable approach in combating extremism.

Public Interest Statement

The key to understanding and addressing Islamic extremism lies in the meaning of the term. Too often, terms such as terrorism and radicalisation are added into the meaning which leads states to address the problems associated with Islamic extremism in a reactive manner. This leads to large parts of the population isolated and frustrated, especially the youth. This article provides insight into the term and concludes that Islamic extremism is a political and governance problem and should be addressed as such.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

1. Introduction

The aim of the article is to discuss the etymology of so-called “Islamic extremism”. The hypothesis is that by understanding the term Islamic extremism for what it truly is, more comprehensive solutions for it would be found. So, what does “Islamic extremism” mean? For instance, does it imply due to the religious implication of the word “Islamic” that such extremism is exclusively religious in nature? Does it not perhaps include political or economic extremism too? In order to begin answering such and other questions, a baseline analysis will firstly be conducted by examining the political spectrum and how it relates to extremism.

2. The political spectrum and extremism

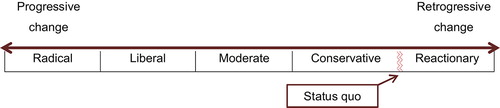

Normally, the position of Status Quo in the political spectrum would look like this (Baradat, Citation1999, p. 17) (Figure ):

At the extreme opposite ends of the spectrum, radical and reactionary actors are found. The following points are relevant to the discussion:

| • | A radical actor can be defined as a person who is extremely dissatisfied with society as it is and is therefore impatient with less extreme proposals for changing it. Hence, radicals favour an immediate and fundamental change in the society (Baradat, Citation1999, p. 19). | ||||

| • | Only the reactionary actor proposes retrogressive change – therefore s/he would like to see society return to a previous status, condition or value system. Note that reactionaries reject claims to human equality and instead favour distributing wealth and power unequally on the basis of race, social class, intelligence, or religion. They further reject notions of social progress as defined by people to their left and look back to other previous held norms and values (Baradat, Citation1999, pp. 29–30). | ||||

Considering the different actors on the political spectrum, the following observations could be made:

| • | All of the actors are looking for political change regardless whether or not they may have a religious, political or economic character. | ||||

| • | The direction of change sought by all of the actors except for the reactionaries, is considered to be progressive (or to move from the status quo to something new and different) (Baradat, Citation1999, p. 16). | ||||

Therefore, it could be argued that merely desiring political change does not equate to extremism. In fact, extremist actors only become apparent when the following aspects are considered:

| • | The depth of the proposed change (whether or not it is a minor or major adjustment to society that is expected). For instance, when in June 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham’s (ISIS) leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, declared the areas of northern Iraq and eastern Syria to be a single Islamic state (or “caliphate”), with himself as caliph, the depth of the proposed change in society changed dramatically. Once declaring the caliphate, ISIS changed its name simply to the Islamic State (IS), claiming that all other Muslim communities should pay homage to IS as the one true Islamic state (Auerbach, Citation2014). The interests of IS went beyond Syria or Iraq and its members believed that the world’s Muslims should live under one Islamic state ruled by sharia law (Economist, Citation2014). | ||||

| • | The expected speed of the proposed change (meaning more upset actors with the status quo would want speedier change). IS moved with considerable speed to expand its ideologies and territory. For example, IS became a growing presence in Libya in 2015 and a more potent factor in the local conflict. It controlled the eastern city of Derna in Libya, which it proclaimed as an emirate, and launched a series of attacks and car bombings across Libya. IS gained further support from fighters who deserted from longer-established Islamist groups in Libya, including from al-Qaeda and Ansar al-Sharia. At the same time, numerous foreign fighters moved to Libya to reinforce both IS and Ansar al-Sharia (Nicoll & Delaney, Citation2015, pp. 1, 3). On 20 March 2015, IS claimed responsibility for bombings at two mosques in Sanaa, Yemen. This would mark the group’s first large-scale attack in Yemen. These blasts killed at least 137 people and wounded 357 others (Botelho & Almasmari, Citation2015). In Somalia there were reports of tensions within al-Shabab between those who wanted to break away from al-Qaeda and align themselves with IS, and those who wanted to remain loyal to al-Qaeda’s leader Ayman al-Zawahiri (Hellyer, Citation2015). | ||||

| • | The method of change (whether change is sought through official, legal, or violent means) (Baradat, Citation1999, pp. 16–19). The methods IS used to expand and influence its followers was not done through any legal means but through violence. IS for all its sophistication was also an organisation that carried out beheadings, mass executions, the abduction of women and children, and even crucifixions (Marshall, Citation2014). The United Nations condemned the killings of civilian hostages by IS as war crimes, and stated that they constituted grave abuses of human rights and international humanitarian law (Protect, Citation2015). | ||||

So based on the above, extremism could be found at both ends of the political spectrum, and could be easier described in terms of the political spectrum. But on which side of the spectrum is Islamic extremism? Nonetheless, extremism (even so-called religious extremism), could be easier described in terms of the political spectrum: “extremists” are those actors who seek immediate and major political change within the Status Quo through illegal, often violent means. Considering such a conclusion, how are extremists more often described?

3. Understanding Islamic extremism

In existing definitions of extremism seems to incorporate the conclusion above. Essentially, the emphasis is placed specifically on the extreme radical character and the harshness of the actors’ measures. However, the difference is that the boundaries of this extreme character of the extremist actor and the content of their actions depend on the specific cultural and historical conditions, which are in turn determined by social law. Accordingly, “extremism” means the disruption of the state’s monopoly on violence: in every specific case it is the state that determines what extremism is (Omel’chenko, Citation2015 p. 53). As a consequence, extremism, especially Islamic extremism, is often equated with the terms “terrorism”, the “war on terror”, and “Islamic radicalization” (Kruglanski et al., Citation2014, p. 70). These three terms are, however, subjective to the views of the particular state and add to an inability to find a holistic solution to extremism. Such subjectivity takes away from the meaning of Islamic extremism.

3.1. Terrorism

Ironically, “terrorism” has never been defined by the United Nations even though numerous international treaties and resolutions have addressed the need for counterterrorism measures (Setty, Citation2011, p. 11). The concept of terror is also too easily used without really considering the psychological meaning of the notion; the word’s usage is skewed in relation to the word’s etymology. Consider the psychological state that terrorists typically strive to produce: they want the citizenry and the government to respond in a rational way, giving them what they desire after sober reflection on the increasing costs that the terrorists will impose if they do not (Rapin, Citation2010, p. 163). This is not necessarily true about IS as they do not make demands to the citizenry and/or any government to respond in a rational way, instead they rather behave in an irrational way driven by religious fundamentalism (Gunning & Jackson, Citation2011, p. 371).

3.2. The war on terror

The international “war on terror” was enabled through UN Security Council resolution 1,373 which mandated member states to combat terrorism in numerous ways, work cooperatively with other member states to share information related to security issues, and report to their Counter-Terrorism Committee on these matters. However, by still lacking a definition of terrorism, the parameters for the implementation of counterterrorism efforts could not be executed (Setty, Citation2011, p. 12).

3.3 Islamic radicalization

The third term is “Islamic radicalization”. This is an insightful term as it indicates the type of political change sought by the extremists: radicals promise progressive change according to the political spectrum. Is this, however, accurate for instance in the case of so called “religious terrorists”? For instance, it is suggested that “religious terrorists” are not interested in gradually building a better world or in reform, but in destroying the world as a means of hastening the prophesied return of “God”, “the Messiah” or “the Mahdi” in the final instalment of human history (Gunning & Jackson, Citation2011, p. 371). Case and point being IS who as “Salafist jihadists” are committed to what they see as the original meaning of the sacred texts of Islam (Eichenwald, Citation2014). Consequently, IS is essentially seeking to change the existing political order in the Middle East through so-called terrorist violence, to establish a state based on a misinterpretation of Islamic religion, and to expel foreign influence - political, economic and ideological (UN, Citation2014, p. 6). IS trying very hard to portray selling progressive change but their ideas are in fact very much retrogressive in nature. As a consequence, by analysing the political spectrum, the wording should rather be “Islamic reactionism” and not radicalization. According to the aforementioned arguments, “Islamic Extremists” could thus be described as those reactionary actors who seek immediate and major political change within the Status Quo through illegal and violent means. Although this may be very much a simple generalization it does highlight that Islamic Extremism is thus not a question of religious actors seeking religious change, but a clear attempt to return society to a previous political-religious condition and value system.

Using subjective terms such as “terrorism”, the “war on terror”, and “Islamic radicalization” thus lead to a poor understanding by states to address reactionism. Continuing with these terms, it is notable to see what are generally considered to be the drivers of terrorism. According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) based in the US, in relatively more developed and politically stable OECD countries, drivers of terrorism correlate with socio-economic factors such as a lack of opportunity and low social cohesion; while in less developed and less politically stable non-OECD countries, these drivers correlate with internal conflicts, political terror and corruption (Humanity, Citation2015). Although these views might be accurate they remain subjective and predicate reactive actions from OECD-countries. Two points should therefore be kept in mind when actions are taken by states against so-called drivers of terrorism:

| (1) | The first point that should be considered, is that by describing Islamic extremism in terms such as terrorism or Islamic radicalisation, the focus in preventing attacks or stopping groups such as IS becomes reactive in nature, such as the introduction for counterterrorism measures expressed for by the United Nations. These reactive focuses further include measures to counter certain ideologies from spreading, instituting a better state security apparatus, expanding strategic partnerships between states on intelligence and security, as well as targeted police and military responses (Solomon, Citation2013, pp. 68–77). It is thus understandable that OECD countries, having identified the drivers of terrorism from a Western perspective, may believe that military interventions in non-OECD countries against groups such as IS as well as to simultaneously strengthen their own domestic security apparatus would be effective and targeted measures to stop the drivers of terrorism. Reactive measures are therefore a direct result of a limited interpretation of “Islamic Extremism”. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (2) | The second point is that the keys to identifying the drivers of Islamic extremism may be found in a more appropriate interpretation of the term. As such, Islamic extremism points to ideas to change society to a previous political-religious system. These ideas are supported by people throughout the world for reasons which are not always obvious. But by dissecting these ideas takes the focus away from the people who come up with these ideas. The point is that states understand these extremist ideas all too well but cannot identify or predict exactly who are these people having extremist ideas. For example, the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) tried to solve exactly this issue. They undertook a qualitative study of individuals who chose to leave their home countries to fight for al-Qa’ida primarily against the United States and its allies. The results of the study found that individuals who chose to travel to fight for al-Qa’ida (IEP, Citation2015, p. 73):

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unfortunately, the results of this study did not solve the issue but highlight the pseudo conclusion that anyone is potentially a “terrorist”. Perhaps the question needs to be rephrased – maybe it should not be about who these people are, but rather why are people joining extremist groupings? For instance, it is known that, people, especially young people, were joining IS from every continent on earth (Jaafari, Citation2014). Does a focus on young people provide any additional insight on the reasons why some people are prone to extremist ideas?

4. The causal link between young people and extremism

Young people are accepted to be people 30 years or younger—which is considered to be the global median age (U. N. UN, Citation2015a, p. 9) and numbered in 2016 to be approximately 3.7 billion people out of a total 7.3 billion people on the planet (U. N. UN, Citation2015c, p. 1). As of 2010, Islam had the second largest religious following in the world with 1.6 billion adherents (Mungai, Citation2015) or close to 800,000,000 people younger than 30 years of age. Why would young people be involved in an attempt to return society to a previous political-religious condition and value system? Extremist identification among the youth is linked to young people’s ignoring of society’s established norms and values, and to the quest for other norms and values that differ substantially from those that are socially accepted (Omel’chenko, Citation2015, p. 56). Specific grounds for youth extremism include (Omel’chenko, Citation2015, pp. 53–58):

| • | Certain essential traits of that age: young people’s urge for romanticism, their striving to be actively involved and to overcome obstacles – this may make them “reckless” in their decision-taking; | ||||

| • | Problems related to the search for identity especially in circumstances of large-scale social transformations in which a majority of the categories by means of which an individual defines himself and his place in society seemed to have lost their value; | ||||

| • | The formation of an authoritarian personality complex: a propensity toward unwavering respect for authorities within a group, excessive concern with matters of status and power, stereotypical judgments and assessments, and intolerance toward uncertainty; | ||||

| • | A fourth cause of extremist behaviour is rooted in the society’s dominant culture. Even though a key feature of a modern “civilized” society is the formal rejection of violence, the culture of violence in society still persists, is given justification, and serves as a powerful factor that fosters extremism; | ||||

| • | The condition of deriving a propensity toward extremist behaviour from unfavourable social and economic conditions and people’s dissatisfaction with their position in society. | ||||

“Whoever has the youth has the future,” was one of Hitler’s often repeated phrases. For the attainment of this future, Hitler took complete charge of the youth’s physical, emotional, and intellectual development in Germany (Kunzer, Citation1938, p. 342). He managed to do this on the specific grounds for youth extremism which was just discussed. It dates back to 1900 when the youth, tired of the strict discipline and regimentation of school authorities and the mechanization of life which was making machines out of men, banded together to seek relief from these pressures. The young German worker, tired of the routine of factory life, and the German student, equally tired of the repressive measures of the school which he believed was crushing out his individuality, sought freedom in a return to nature and the simple life in the out-of-doors (Kunzer, Citation1938, p. 343). But surely the youth is in a better position today and has a much brighter outlook?

4.1. Young people’s future outlook

The young generation of people are confronted with scientific evidence and concern that humanity faces a defining moment in history, a time when the peoples of the world must address growing adversities, or suffer grave consequences. It is a time of climate change and its many, potentially catastrophic impacts; depletion and degradation of natural resources and ecosystems; continuing world population growth; disease pandemics; global economic collapse; nuclear and biological war and terrorism; and runaway technological change (Randle & Eckersley, Citation2015, p. 4). Clearly, for the younger generation, it is a world of “either-or”: either something is done now or there will be consequences. In reality, the global youth are further challenged by unemployment and inequality.

4.1.1. Unemployment

Global youth unemployment constitutes 14% of the total labour force ages 15–24. Youth unemployment refers to the share of the labour force ages 15–24 without work but available for and seeking employment (Bank, Citation2016). This segment of the population equates to 166,000,000 people globally without work (U. N. UN, Citation2015b). By 2050, it is projected that Muslims will have 2.8 billion followers, or constitute 30% of the global population (Mungai, Citation2015). Extrapolated from the above statistics and all things being equal, it means that by 2050, close to 56 million Muslims globally between the ages of 15–24 would be without work. 1

4.1.2. Inequality

Alongside poverty and vulnerability, levels of inequality are rising both across and within countries. The world is said to be more unequal today than at any point since World War II (UNWOMEN, Citation2015, p. 5). By 2015, the bottom half of the global population owned less than 1% of total wealth. In sharp contrast, the top percentile alone accounted for 50% of global assets. Opportunities to bridge this inequality are also the benchmark by which young people are judging the prevailing political or economic systems to see whether they could provide opportunities to catch-up themselves. However, to be among the wealthiest half of the world in mid-2015, an adult needed USD3,210 in assets, once debts were subtracted. Moreover, a person needed at least USD68,800 to belong to the top 10% of global wealth holders and USD760,000 to be a member of the top 1% (Suisse, Citation2015, p. 99).

It could be concluded that young people may feel they would not be able to catch-up if the economic or political status quo continues to prevail. It is thus likely that young people could become en masse increasingly dissatisfied with the political status quo. In Britain, research pointed to an increased sense of alienation and radicalisation of young people in an increasingly segregated Britain. On Monday, 7 March 2016, Britain’s senior counterterrorism officer stated that British police are preparing for “enormous and spectacular” potential attacks on the UK as IS moves into its “next natural phase” (Foster & Hume, Citation2016). Clearly, we understand the threats posed by and the ideas of Islamic Extremism but we struggle to understand the enemy living within our society. Will local young people be involved in these attacks? Most probably. Indeed, young people are represented as both a social problem and a social threat, leaving young people themselves to feel “demonised” by government policy and media reporting (Grattan, Citation2008, p. 256). This reflected the public opinion that young people who dare to show any sympathy with a political discourse fundamentally at odds with mainstream views are not worthy of society’s respect and efforts, let alone its trust: they are, in one word, suspect individuals that ought to be removed from society (Sieckelinck, Kaulingfreks, & De Winter, Citation2015, p. 331).

The appropriation of a religious identity can serve as a powerful strategy to gain self-esteem in a discouraging environment. A small group of Islamic youth indeed develops a more oppositional or extreme strategy to gain self-esteem. For these young people, the authorities can lose their legitimacy. Since they do not expect authorities to support future changes of their situation, these young people turn their back and look for other options to develop a positive perspective. In this light, the sympathy for jihad can be seen as an attempt to connect with another worldview, another place in this world, where one escapes the difficulties at home and where one can make a valuable difference as a Muslim (Sieckelinck et al., Citation2015, p. 336). Notably, the proclamation of the Islamic State as a caliphate is perhaps their most profound manner in which it claimed legitimacy and asserted itself as the vanguard of Islam. In general a caliphate is more than just a political entity within the Islamic faith; it is a vehicle for salvation (Mokose & Solomon, Citation2015, pp. 18–19). By selling an alternative political, religious and even economic system to young Muslim people, IS has become an attractive destination for the masses of dissatisfied young Muslim people. If with IS’ decline by 2017, the problems which young people are facing, will still be there.

5. Conclusion

While extremism in all its different manifestations has existed throughout the ages (consider the Christian Crusades, Nazism and Apartheid), the latest manifestation, Islamic extremism, is somehow perceived to be different. It is not different because of its Islamic character or even for its brutality; it is different because of its timing in history, what it shows about the character of the world, and its inevitable consequences. Islamic extremism, as with any other type of extremism, has an origin—a type of justification for it to exist in the first place. More importantly, it has a growing base to recruit from: the discontented youth of the world. This may not be the only base but certainly the most prolific one in terms of numbers. Islamic extremism is therefore just one manifestation of some of the pressures to change the world order. By analysing the term Islamic extremism, it becomes clear that more than only reactive measures are required to defeat it. Islamic extremism is the result of a political and systemic failure of governments to ensure that true equality prevails in all sectors of society. Yes, extremist ideas need to be countered and the terrorist activities stopped, but foremost, the reasons for these ideas which allow them to proliferate among the young generation should be addressed. Islamic extremism is a political problem and should be discussed as such.

Funding

This work would not have been possible without the financial support from the Focus Area: Social Transformation at the Potchefstroom Campus, North-West Campus.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Barend Louwrens Prinsloo

Dr Barend Louwrens Prinsloo is employed as a Senior Researcher in Security Studies and Management at the North-West University in South Africa. His research interests include Security Studies focusing on topics such as security risk management, efforts to maintain international peace and security, and the transformation of the geopolitical and geo-economic order affecting Africa. Dr Prinsloo also worked for almost 10 years at the United Nations, serving both in Peacekeeping and the Department of Safety and Security.

Notes

1. By 2050, according to these estimates 100% of the global population would equate to 9.3 billion people. (Other estimates put the global population at 9.7 billion people). The 14–25 year old segment equates to 14.3% of the total population in 2016. 14.3% of 9.3 billion people equates to 1.3 billion people.14% unemployment rate in this segment would equate to 186,186,000 people of which 30% are Muslims or close to 56 million people.

References

- Auerbach, M. P. (2014). Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) . Hackensack: Salem Press.

- Bank, W. (2016). Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15–24) (modeled ILO estimate) . Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS/countries/1 W?display=graph

- Baradat, L. P. (1999). Political ideologies: Their origins and impact . Upper Saddle River¸ NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Botelho, G. , & Almasmari, H. (2015, 23 March). State Department: U.S. pulls remaining forces out of Yemen . Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2015/03/21/politics/yemen-unrest/index.html

- Economist, T. (2014, 20 January). What ISIS, an al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, really wants. Explaining the world, daily . Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/01/economist-explains-12

- Eichenwald, K. (2014). ISIS will fall. Newsweek Global , 163 (11), 12.

- Foster, M. , & Hume, T. (2016). UK police preparing for ‘enormous’ potential ISIS attacks, British terror chief says . Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2016/03/07/europe/uk-isis-preparing-attacks/index.html

- Grattan, A. (2008). The alienation and radicalisation of youth: A ‘New Moral Panic’? International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities & Nations , 8 (3), 255–264.10.18848/1447-9532/CGP

- Gunning, J. , & Jackson, R. (2011). What’s so ‘religious’ about ‘religious terrorism’? Critical Studies on Terrorism , 4 (3), 369–388. doi:10.1080/17539153.2011.623405

- Hellyer, C. (2015, 23 March). ISIL courts al-Shabab as al-Qaeda ties fade away. War & Conflict . Retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2015/03/isil-eyes-east-africa-foments-division-150322130940108.html

- Humanity, V. O. (2015). Global terrorism index . Retrieved from http://www.visionofhumanity.org/#/page/our-gti-findings

- IEP, I. f. E. a. P. (2015). Global terrorism index 2015–Measuring and understanding the impact of terrorism . Retrieved from http://www.visionofhumanity.org/sites/default/files/2015%20Global%20Terrorism%20Index%20Report_0.pdf

- Jaafari, I. A. (2014). Iraq, Syria and regional security: Ibrahim Al Jaafari . Paper presented at the IISS Manama Dialogue 2014: 10th Regional Security Summit. https://www.iiss.org/en/Topics/islamic-state/jaafari-ce95

- Kruglanski, A. W. , Gelfand, M. J. , Bélanger, J. J. , Sheveland, A. , Hetiarachchi, M. , & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology , 35 (2), 69–93. doi:10.1111/pops.12163

- Kunzer, E. J. (1938). The youth of Nazi Germany. Journal of Educational Sociology , 11 (6), 342–350.10.2307/2262246

- Marshall, R. (2014). ISIS: A New Adversary in an Endless War. Washington Report on Middle East Affairs , 33 (8), 8.

- Mokose, M. , & Solomon, H. (2015). Ending Islamic State’s reign of terror. Research Institute for European and American Studies , 169 , 1–45.

- Mungai, C. (2015). The future of world religion is African, so what would an ‘African’ Christianity or Islam look like? Retrieved from http://mgafrica.com/article/2015-11-30-the-future-of-religion-in-africa

- Nicoll, A. , & Delaney, J. (2015). Libya’s civil war: The essential briefing. Strategic Comments , 20 (50), 5.

- Omel’chenko, E. L. (2015). The solidarities and cultural practices of Russia’s Young People at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century. Russian Social Science Review , 56 (5), 2–17. doi:10.1080/10611428.2015.1115285

- Protect, T. O. o. G. P. a. t. R. t . (2015, 6 February). Statement by Adama Dieng, Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide and Jennifer Welsh, Special Adviser on the Responsibility to Protect, on the escalation of incitement rhetoric in response to the murder of Jordanian pilot Moaz al-Kasasbeh. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/adviser/pdf/2015-02-06.Statement%20on%20the%20escalation%20of%20incitement%20rhetoric%20in%20response%20to%20the%20murder%20of%20Jordanian%20pilot.pdf

- Randle, M. , & Eckersley, R. (2015). Public perceptions of future threats to humanity and different societal responses: A cross-national study. Futures , 72 , 4–16. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2015.06.004

- Rapin, A. J. (2010). What is terrorism? Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression , 3 (3), 161–175. doi:10.1080/19434472.2010.512155

- Setty, S. (2011). What’s in a name–How Nations define terrorism ten years after 9/11 [ article] (pp. 1–64).

- Sieckelinck, S. , Kaulingfreks, F. , & De Winter, M. (2015). Neither villains nor victims: Towards an educational perspective on radicalisation. British Journal of Educational Studies , 63 (3), 329–343.10.1080/00071005.2015.1076566

- Solomon, H. (2013). Jihad–A South African perspective . Bloemfontein: Sun Media.

- Suisse, C. (2015). Credit suisse global wealth databook 2015. Retrieved from http://publications.credit-suisse.com/tasks/render/file/index.cfm?fileid=C26E3824-E868-56E0-CCA04D4BB9B9ADD5

- UN . (2014). Letter dated 13 November 2014 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999) and 1989 (2011) concerning Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council. (S/2014/815) . New York: United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2014/815

- UN, U. N. (2015a). World population prospects–2015 revision . Retrieved from http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/Key_Findings_WPP_2015.pdf

- UN, U. N. (2015b). World population prospects, the 2015 edition . Retrieved from http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/DataQuery/

- UN, U. N. (2015c). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, custom data acquired via website . Retrieved from http://esa.un.org/

- UNWOMEN . (2015). Substantitive equality for women: The challenge for public policy . Retrieved from http://progress.unwomen.org/en/2015/pdf/ch1.pdf