Abstract

Transactional sexual relationships (TSRs) are of concern because of the negative health outcomes associated with the practice. Lack of condom use and multiple concurrent partnerships increase the risk of HIV infection and unintended pregnancies. For these reasons, a multitude of studies have been done to better understand the determinants of these relationships, particularly among youth who engage in sex with wealthier and often older partners. While the economic motivations among youth are known, broader determinants, such as having at least one child are rarely investigated. The role of having children is important to consider, as this suggests an economic motive for these relationships related to childcare needs. The objective of this study is to determine the association between having a child and TSRs among young women in South Africa. Cross-sectional data of 331 young females who engage in this practice are analysed. Descriptive statistics and multivariate logistic regressions are fit to the data to determine the association. Results show that youth not living with parents (84.96%) and those who see more than one sexual partner as acceptable (66.01%) engage in TSRs. Further, having at least one child increases the odds (OR = 1.98 p-value 0.004) of engaging in TSRs. In conclusion, having at least one child, as an economic motivation underlying TSRs should be taken into policy and intervention considerations. Young mothers should be specifically targeted in socioeconomic policies to enable them to care for their offspring without needing to engage in TSRs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

When young women, under the age of 25 years old, have children they are placed under considerable financial strain. Often women of these ages are completing education and entering the labour force for the first time making their economic situation is unstable. In this study we found that young mothers are likely to engage in transactional sexual relationships. The presence of children suggests that these relationships are supporting children in their care. Issues of women, poverty and transactional sex are fundamental in many countries as these women compromise safe-sex practices in order to obtain goods and money from sexual partners. This enables the spread of STIs including HIV and AIDS, as well as unintended pregnancies. The results of this study show the need for policies to protect young mothers from transactional relationships through offering safer alternatives to support their needs, including childcare.

1. Introduction

Transactional sex is a practice whereby money and/or goods are exchanged for sexual intercourse (Dunkle et al., Citation2004, Citation2007; Dunkle, Wingood, Camp, & DiClemente, Citation2010). The practice of transactional sexual relationships (TSRs) is widespread and has adverse health consequences. A study of four countries in Sub-Saharan Africa show that between 36% and 80% of adolescent girls (12–19 years old) engage in TSRs (Moore, Biddlecom, & Zulu, Citation2007). In South Africa, a study of adolescent girls of the same age found that 14% reported TSRs (Ranganathan et al., Citation2016). Associated with lack of condom use, transactional sex is known to increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STI), including HIV/AIDS and unintended pregnancies (Dunkle et al., Citation2004; Leclerc-Madlala, Citation2003; Luke & Kurz, Citation2002). The reason for this is that youth who are receiving money or goods in exchange for sexual intercourse are unable to negotiate condom use for fear of not receiving the negotiated goods (Mwaba, Simbayi, & Kalichman, Citation2015; Pettifor et al., Citation2017). In addition, research has found that these relationships are often not monogamous enabling the fast spread of HIV through these sexual networks (Shisana et al., Citation2016).

These relationships are knowingly economically motivated, with financial and material gains being the primary driving force. As such, poverty has been cited as a major determinant for TSRs, with females reportedly engaging in this practice to meet their basic needs (Cluver, Boyes, Orkin, & Sherr, Citation2013; Fielding-Miller, Dunkle, Cooper, Windle, & Hadley, Citation2016; Stoebenau, Heise, Wamoyi, & Bobrova, Citation2016; Zembe, Townsend, Thorson, & Ekström, Citation2013). In other literature, however, consumerism and social status have been noted as a determinant of these relationships with young females engaging in these relationships for the purpose of obtaining alcohol, the latest fashion trends, cellular phones and other consumerist goods (Deane & Wamoyi, Citation2015; Kamndaya, Vearey, Thomas, Kabiru, & Kazembe, Citation2016; Stoebenau et al., Citation2016; Swartz & Van der Heijden, Citation2015). Among youth, therefore, poverty along with the pressures brought on by widespread consumerist lifestyles has led to an increasing popularity of TSRs in many countries, including South Africa. Evidence of the popularity of the practice in South Africa is seen by the coining of a new term, “Blesser”, used on social media. Similar to what is known as a “sugar daddy”, these are usually but not always older, sexual partners who offer money and gifts in exchange for sexual relationships with younger partners (Sidloyi, Citation2016). The recipient of gifts and money has come to be known as a “Blessee” and social media has been a predominant promoter of these relationships with the hashtag (#)blessed being used by “Blessees” to publicly display their “gifts” (Dube, Citation2016). And where wealthier partners are willing to provide gifts and money, less wealthy youth are willing to engage in these sexual transactions.

An extensive amount of literature has related TSRs to the spread of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa, including South Africa. A systematic review of the relationship between TSRs and HIV infection among youth in Sub-Saharan Africa found a significant, positive, unadjusted (the variable on its own) and adjusted (the variable plus other predictor variables) association between transactional sex and HIV in 10 out of 14 studies of females in the region (Wamoyi, Stobeanau, Bobrova, Abramsky, & Watts, Citation2016). One of these studies used a longitudinal design and found a causal link between transactional sex and HIV infection (Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, & Shai, Citation2012; Wamoyi et al., Citation2016). A study from South Africa specifically, on females attending four clinics in Soweto, Johannesburg, found that TSRs was associated with HIV seropositivity after controlling for lifetime number of male sex partners and length of time females have been sexually active (Dunkle et al., Citation2004). Research has also confirmed that youth in the country are aware that TSRs heighten the risk of HIV infection (Milford et al., Citation2014).

However, despite the potential risks being known, the practice persists as the expected gains perceivably outweigh the risks and for some, this is their only choice. This raises questions then regarding the underlying and overlooked determinants of these relationships. A possible determinant, which has not been largely explored, is the role of having at least one child in TSRs. Outside of unintended pregnancies being a result of these relationships, research has not addressed the relationship between already having children and engaging in transactional sex. However, there is need to do so, particularly because childbearing among youth in South Africa is fairly common and poverty is high. Recent estimates show that 86.1 pregnancies per 1,000 female population aged 10–24 years old occurred in 2015 (Statistics SA, Citation2016). Among other socioeconomic determinants of early childbearing, which have been identified, an important association has been found between wealth of the household and early childbearing. Research on wealth status shows that adolescents from poorer households have higher fertility rates than those from wealthier households (Galster, Marcotte, & Mandell, Citation2013). Therefore, young mothers are often financially constrained, juggling employment, education, and childcare responsibilities simultaneously and often alone (Marock, Citation2015). For these youth, a “Blesser” or transactional sexual partner may provide some much-needed financial relief in caring for their children.

The purpose of this research, therefore, is to examine the association between having at least one child and TSRs among young females (15–24 years old) in South Africa.

1.1. Theoretical framework

According to the Social Exchange Theory, the decision to engage in any behaviour is made through, not only the social acceptability of the practice, but also through an analysis of the costs and benefits involved (Emerson, Citation1976). This theory has been applied to a multitude of behavioural outcomes, including TSRs (Cox et al., Citation2014; Luke, Goldberg, Mberu, & Zulu, Citation2011; Watt et al., Citation2012). This theory is chosen to underpin the current study because of its reference to cultural norms as influencing the cost-benefit (or punishment-reward) analysis of interactions, in this case TSRs. Further, the reward or benefit of gaining material goods is assumed to outweigh the costs. And an overlooked benefit is financial assistance to care for children. These costs would include unintended pregnancy and, the risk of STIs associated with the lack of condom use. This theoretical understanding however, has not been applied to consider the role that having to care for children plays in the likelihood of TSRs.

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data source

The data are from the HIV prevalence, knowledge, attitude, behaviour and practice (KABP) study in the tertiary education sector of South Africa (HEAIDS, Citation2010). The purpose of this survey was to enable the higher education sector to understand the extent of HIV/AIDS prevalence among students and staff. This was done through determining, at the institutional and sector level, the prevalence and distribution of HIV and associated risk factors among the staff and students at public higher education institutions (HEIs) in South Africa and the data were collected through self-administered questionnaires (HEAIDS, Citation2010).

2.2. Study design and population

The cross-sectional survey population consisted of students and employees at 21 HEIs in South Africa where contact teaching occurs (HEAIDS, Citation2010). Ethical approval was obtained from each institution’s internal Ethics Committees (HEAIDS, Citation2010). Each HEI population was stratified by campus and faculty/class and then clusters of students and staff were selected for the study using standard randomisation techniques (HEAIDS, Citation2010). An overall sample of 26,574 respondents were targeted and self-administered questionnaires were used to obtain demographic, socioeconomic, behavioural and HEI-related data (HEAIDS, Citation2010). The field work for the study was conducted between August 2008 and February 2009 (HEAIDS, Citation2010).

The sample for this study includes all sexually active females between the ages of 15 and 24 years old. A total of 7,136 (N) sexually active female youth with completed information were identified. Of these 331 (N) females reportedly engaged in TSRs and of these 99% have at least one child.

2.3. Study variables

The outcome of interest in this study is engagement in TSRs. To derive this variable, participants who responded positively to the statement “I expect money/gifts for sex” were identified as having engaged in TSRs. Similar questions have been used in TSR research because statements like this are believed to be indicative of behaviour and not perception or attitudes (Biddlecom, Citation2007; Cluver, Orkin, Boyes, Gardner, & Meinck, Citation2011; Dunkle et al., Citation2004).

The main predictor variable for the study is having at least one child. To identify respondents who had at least one child, the question pertaining to “age of first born” was used. Respondents who reported age of child (any value >1) are considered to have “has children” (1) and the ‘0’ and “not applicable” responses are used to indicate “no children” (0).

The control variables for the study are grouped into background, cultural norm, costs and benefits. The background variables include sex, age group, race or population group, living with parents (yes or no) of the respondent. For cultural norms, questions from the survey pertaining to the acceptability of multiple sexual partners are used. In turn, youth are asked (1) if it is acceptable for a man to have more than one girlfriend and then, (2) if it is acceptable for a woman to have more than one boyfriend. Positive responses (strongly agree and agree) to either of these questions is coded as “agree” or negative responses (strongly disagree and disagree); to either of these is coded as “disagree” or an “unsure” category is used to denote respondents who could not decide. The variable is named “it is acceptable to have more than one partner”. Under costs, “condom use at last sex” (yes/no) is used and under benefits an asset index is created using Principle Component Analysis (PCA) is a method that transforms many correlated variables into fewer categories of responses. The asset index was derived ownership of the following by the respondents: bicycle, motorcycle, motor car, cellular phone and computer.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Bivariate associations between the outcome and predictor variables were assessed using frequency distributions and the chi-square test. The individual and combined effects of the respondents’ characteristics, including fertility and transactional sex were analysed using unadjusted and adjusted binary logistic regression models, producing odds ratios and p-values with the level of statistical significance set at less than 0.05.

3. Results

Almost 66% of the sample is between the ages of 15 and 19 years old and 80% do not live with their parents (Table ). A further 96.23% do not believe it is acceptable to have more than one sexual partner, while just over half (52.02%) did not use a condom at last sexual intercourse. Finally, 98.41% of the female respondents have at least one child. Of those who engage in TSRs, 92.40% are 15–19 years old, 75.49% do not live with parents, and 66% agree that it is acceptable to have more than one sexual partner. Further, among those who engage in TSRs, 68.01% have low ownership of assets and almost all (99.87%) have at least one child.

Table 1. Respondent’s background, social acceptability, costs and benefits percentage distribution by engagement in transactional sexual relationships

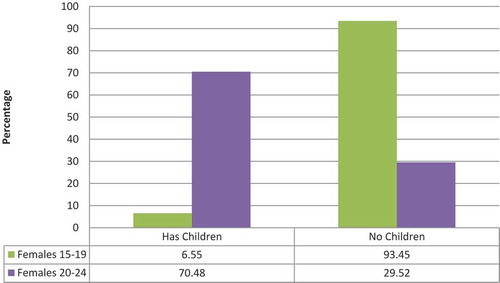

Figure shows the percentage distribution of having at least one child by the age of the respondents. The figure shows that only 6.55% of 15–19 years in the study sample have at least one child and about two-thirds (70.48%) of 20–24 year olds also reported having children.

Table shows the unadjusted odds ratios and two models of adjusted regression analysis. Adjusted Model I predicts the odds of TSRs without having at least one child as a variable in the study and Adjusted Model II includes having at least one child. The unadjusted and adjusted also show consistently lower likelihood of TSRs among older (20–24 years old) youth compared to adolescents (15–19 years old) who are the reference category (RC). Similarly youth who live with their parents also have consistently lower odds of TSRs compared to those who do not. In these models, for the question on acceptability, the “unsure” category was grouped with the “disagree” category due to the low number of responses and results show that youth who find multiple sexual partnerships not acceptable and therefore disagree with the cultural norm, have lower. 0.012 (unadjusted) and 0.001 (adjusted),odds of engaging in TSRs than those who accept this cultural norm. Further, youth with medium or high assets, all have lower odds of TSRs at 0.482 odds in the unadjusted model, 0,649 and 0.647 in the adjusted models than those with few (or low) assets (RC) who have even odds of TSRs. Finally, having children increases the odds of TSRs as shown by the 1.77 odds in the unadjusted model and the 1.98 odds in the adjusted Model II. This means that when children are added to the model, the odds of TSR, which is already likely, increases.

Table 2. Unadjusted and adjusted regression models of all respondent characteristics and transactional sexual relationship outcomes, showing odds ratios

4. Discussion

TSRs are related to unsafe sexual practices and are known to perpetuate the spread of STIs, including HIV/AIDS. Yet these relationships persist despite risk factors, such as poverty, being known and efforts to inform the public of the negative consequences, including the work by the various non-governmental organisations, being made. The main reason this study was done is to examine the role of having to care for children as a predictor of TSRs and this will further contribute to policies and programmes in South Africa that are working to curtail TSRs.

The presence of at least one child is shown to be a determinant of TSRs among young females in South Africa. While it is known that unintended fertility is a consequence of TSRs (Jones, Orozco, & Rascon-Ramirez, Citation2016), the presence of existing fertility as a determinant is a novel contribution to the South African context and corroborates with evidence from elsewhere. A study in Mombasa, Kenya found that about 2.4% of HIV positive females who engaged in TSRs, had at least one pregnancy prior to the sexual transactions (Wilson et al., Citation2015). Another study of Haitian refugees found that about 67% of those who engaged in TSRs had living children (Kolbe, Citation2015). Outside of these two studies, none that show the presence of fertility as a determinant could be found.

This study controlled for other contributing factors in addition to having at least one child. Consistent with existing literature from Uganda, Swaziland and South Africa, this study also found lack of condom use is associated with TSRs (Fielding-Miller et al., Citation2016; Ybarra, Korchmaros, Kiwanuka, Bangsberg, & Bull, Citation2013; Zembe et al., Citation2013). These studies, and others, all confirm that condom use is not easily negotiated within these relationships because of the exchange inherent in these transactions.

A particularly important finding is that youth who are more accepting of multiple sexual partnerships are also more likely to engage in TSRs. This implies the acceptance of non-monogamous relationships, and the existence of broader sexual networks, which literature has found enables the spread of HIV and other STIs (Gupta, Anderson, & May, Citation1989; Thornton, Citation2008; van de Vijver, Prosperi, & Ramasco, Citation2013).

Finally, the study found that youth who do not live with their parents are more likely to engage in TSRs. Youth who live in their parental household are able to save money, purchase goods and have more food security (Davis, Kim, & Fingerman, Citation2016). Whereas, youth who do not have the financial support of shared resources in a parental household, are more financially isolated and prone to economic vulnerability, especially if they are single-mothers (Bleemer, Brown, Lee, & van Der Klaauw, Citation2014; Damaske, Bratter, & Frech, Citation2017; Xiao, Chatterjee, & Kim, Citation2014). Furthermore, youth who do not reside with parents have more social freedom and there is less parental control over behaviours that creates opportunity to engage in TSRs undetected by parents who may not approve.

The study is subject to a few limitations, though these do not affect the validity of the findings. The study is cross-sectional and as such causality could not be determined. That is, the study could not determine if having at least one child to care for is the reason why females engage in TSRs. Second, from the data it could not be determined if the sexual partners of the study population are the co-parents of their offspring or not, nor if the relationships themselves are monogamous, thus leaving these aspects of the relationships between sexual partners unknown. In addition, the measure of TSR does not offer insight into the patterns and duration of these relationships. The measure does not differentiate between once-off, past relationships or repeated relationships with different partners. Knowing these patterns would offer more explanation for the motivations of TSRs. Finally, the variable used to measure TSR is based on the assumption of behavior, however, a more direct measure of engagement in TSR is needed in surveys.

However, there are particular strengths of the study too. First, the study design is strong. Most of the questionnaires were self-administered to protect the anonymity of the respondents and participants attended briefing sessions before responding (HEAIDS, Citation2010). Second, the measure of transactional sex is straightforward, with respondents being asked directly if they agree or disagree with the statement “I expect money/gifts for sex”. This statement is unambiguous and elicits an undeviating response which fits definitively within the conceptualisation of TSRs. The same is true of the measurement of the control variables used in the study. Third, the study controls for the education status of youth, which literature has found to be a major determinant of sexual behaviour (Jones, Eathington, Baldwin, & Sipsma, Citation2014; Vivancos, Abubakar, Phillips-Howard, & Hunter, Citation2013). By limiting the analysis to a population within the same age and education range, this study is able to reduce variability and produce more conclusive results. Finally, the study addresses an aspect of TSRs, which has yet to be explored. That is, the effect having children has on the transactional sexual behaviours of young females.

5. Conclusion

Fertility as a determinant of TSRs is an important finding that further underscores the economic motivations driving these practices. Young mothers are vulnerable to poverty through attempting to care for their children while also attaining education and employment. Transactional relationships are therefore a means of escaping poverty for both mother and child, despite the risks associated with this behaviour. An implication of the results of this study is that financial support for young mothers in the country is lacking.

The study contributes to knowledge on TSRs by identifying a determinant that has largely only been treated as an outcome of these relationships. Programmes and policies that address the plight of young mothers in the country benefit from this study by being presented with an alternative reason for engaging in risky behaviours. With this evidence, short-term consequences of unintended pregnancies can be avoided and long-term consequences, including the contraction of HIV/AIDS, can be addressed to prevent illness and the orphanhood of children due to the disease.

Finally, there are few research recommendations which can be made from this study. A qualitative study that explores the reasons why young females with children engage in TSRs is needed. In this regard, programmes can benefit from case- study evidence detailing the actual reasons why these females put themselves at risk. In addition a longitudinal study which places the birth of children before the engagement in TSRs would give causal insight into the timing of these relationships, which will enable earlier intervention. Policies and programmes in South Africa which aim to reduce HIV/AIDS infections among youth, such as AVERT and SANAC and those aimed at increasing the number of graduates at HEIs, such as Higher Education South Africa (HESA) should incorporate the results of this study as it specifies another group of youth who should be targeted for interventions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicole De Wet

Nicole De Wet, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer and Head of Department, Demography and Population Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her research interests are in adolescent health and mortality outcomes in Southern Africa.

Sasha Frade

Sasha Frade, MA, is an Associate Lecturer, Demography and Population Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her research interests are in gender-based violence and fertility in sub-Saharan Africa.

Joshua Akinyemi

Joshua Akinyemi, PhD, is a Lecturer I, Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. His research interests include infant and child health outcomes in sub- Saharan Africa.

References

- Biddlecom, A. E.(2007). Prevalence and meanings of exchange of money or gifts for sex in unmarried adolescent sexual relationships in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11(3), 44–61.

- Bleemer, Z., Brown, M., Lee, D., & van Der Klaauw, W. (2014). Debt, jobs, or housing: What’s keeping millennials at home? FRB of New York Staff Report No. 700. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2530691

- Cluver, L., Boyes, M., Orkin, M., & Sherr, L. (2013). Poverty, AIDS and child health: Identifying highest-risk children in South Africa. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal, 103(12), 910–915. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.7045

- Cluver, L., Orkin, M., Boyes, M., Gardner, F., & Meinck, F. (2011). Transactional sex amongst AIDS-orphaned and AIDS-affected adolescents predicted by abuse and extreme poverty. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 58(3), 336–343. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822f0d82

- Cox, C. M., Babalola, S., Kennedy, C. E., Mbwambo, J., Likindikoki, S., & Kerrigan, D. (2014). Determinants of concurrent sexual partnerships within stable relationships: A qualitative study in Tanzania. BMJ Open, 4(2), e003680. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003680

- Damaske, S., Bratter, J. L., & Frech, A. (2017). Single mother families and employment, race, and poverty in changing economic times. Social Science Research, 62, 120–133. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.08.008

- Davis, E. M., Kim, K., & Fingerman, K. L. (2016). Is an empty nest best?: Coresidence with adult children and parental marital quality before and after the great recession. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, gbw022. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw022

- Deane, K., & Wamoyi, J. (2015). Revisiting the economics of transactional sex: Evidence from Tanzania. Review of African Political Economy, 42(145), 437–454. doi:10.1080/03056244.2015.1064816

- Dube, Y. (2016). Social media fuels transactional sex. Chronicle Online. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.co.zw/social-media-fuels-transactional-sex/

- Dunkle, K. L., Jewkes, R., Nduna, M., Jama, N., Levin, J., Sikweyiya, Y., & Koss, M. P. (2007). Transactional sex with casual and main partners among young South African men in the rural Eastern Cape: Prevalence, predictors, and associations with gender-based violence. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1235–1248. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.029

- Dunkle, K. L., Jewkes, R. K., Brown, H. C., Gray, G. E., McIntryre, J. A., & Harlow, S. D. (2004). Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: Prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Social Science & Medicine, 59(8), 1581–1592. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003

- Dunkle, K. L., Wingood, G. M., Camp, C. M., & DiClemente, R. J. (2010). Economically motivated relationships and transactional sex among unmarried African American and white women: Results from a US national telephone survey. Public Health Reports, 125(4_suppl), 90–100. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S413

- Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

- Fielding-Miller, R., Dunkle, K. L., Cooper, H. L., Windle, M., & Hadley, C. (2016). Cultural consensus modeling to measure transactional sex in Swaziland: Scale building and validation. Social Science & Medicine, 148, 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.024

- Fielding-Miller, R., Dunkle, K. L., Jama-Shai, N., Windle, M., Hadley, C., & Cooper, H. L. (2016). The feminine ideal and transactional sex: Navigating respectability and risk in Swaziland. Social Science & Medicine, 158, 24–33. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.005

- Galster, G., Marcotte, D. E., & Mandell, M. (2013). The influence of neighbofhood poverty during childhood on fertility, education, and earings outcomes. Quantifying Neighbourhood Effects: Frontiers and Perspectives, 95, 95–123

- Gupta, S., Anderson, R. M., & May, R. M. (1989). Networks of sexual contacts: Implications for the pattern of spread of HIV. Aids, 3(12), 807–818.

- HEAIDS. (2010). Higher education HIV/AIDS programme (2008–2009) survey of HIV/AIDS in higher education in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Higher Education HIV and AIDS Programme (HEAIDS).

- Jewkes, R., Dunkle, K., Nduna, M., & Shai, N. J. (2012). Transactional sex and HIV incidence in a cohort of young women in the Stepping Stones Trial. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 2012, 158.

- Jones, K., Eathington, P., Baldwin, K., & Sipsma, H. (2014). The impact of health education transmitted via social media or text messaging on adolescent and young adult risky sexual behavior: A systematic review of the literature. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 41(7), 413–419. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000146

- Jones, M., Orozco, V., & Rascon-Ramirez, E. G. (2016). Hard skills or soft talk: Unintended consequences of a vocational training and an inspirational talk on childbearing and sexual behavior in vulnerable youth. Working paper, Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), University of Berkeley, USA, available at http://cega.berkeley.edu/assets/cega_events/114/Rascon_Voc_Training_paper.pdf

- Kamndaya, M., Vearey, J., Thomas, L., Kabiru, C. W., & Kazembe, L. N. (2016). The role of material deprivation and consumerism in the decisions to engage in transactional sex among young people in the urban slums of Blantyre, Malawi. Global Public Health, 11(3), 295–308. doi:10.1080/17441692.2015.1014393

- Kolbe, A. (2015). ‘It’s not a gift when it comes with price’: A qualitative study of transactional sex between UN peacekeepers and haitian citizens. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development, 4(1). doi:10.5334/sta.gf

- Leclerc-Madlala, S. (2003). Transactional sex and the pursuit of modernity. Social Dynamics, 29(2), 213–233. doi:10.1080/02533950308628681

- Luke, N., Goldberg, R. E., Mberu, B. U., & Zulu, E. M. (2011). Social exchange and sexual behavior in young women’s premarital relationships in Kenya. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(5), 1048–1064. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00863.x

- Luke, N., & Kurz, K. (2002)Cross-generational and transactional sexual relations in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW).

- Marock, C. (2015). Grappling with youth employability in South Africa. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC)

- Milford, C., Moore, L., Beksinska, M., Kubeka, M., Sithole, K., Sibiya, S., … Smit, J. (2014). “I would say it does concern me and on the other hand it doesn’t.” Perceptions of south african learners’ experiences with sex, pregnancy, and HIV. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(S1), A62–A62. doi:10.1089/aid.2014.5111.abstract

- Moore, A. M., Biddlecom, A. E., & Zulu, E. M. (2007). Prevalence and meanings of exchange of money or gifts for sex in unmarried adolescent sexual relationships in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11(3), 44. doi:10.2307/25549731

- Mwaba, K., Simbayi, L. C., & Kalichman, S. C. (2006). Perceptions of the combinations of HIV/AIDS and alcohol as a risk factor among STI clinic attenders in South Africa: Implications for HIV prevention. Social Behaviour and Personality, 34(5), 535–544.

- Pettifor, A., MacPhail, C., Watts, C., Kahn, K., Heise, L., Ranganathan, M., … Twine, R. (2017). Young women’s perceptions of transactional sex and sexual agency: A qualitative study in the context of rural South Africa. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 666. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4636-6

- Ranganathan, M., Heise, L., Pettifor, A., Silverwood, R. J., Selin, A., MacPhail, C., … Hughes, J. P. (2016). Transactional sex among young women in rural South Africa: Prevalence, mediators and association with HIV infection. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 19(1). doi:10.7448/IAS.19.1.20749

- Shisana, O., Risher, K., Celentano, D. D., Zungu, N., Rehle, T., Ngcaweni, B., & Evans, M. G. (2016). Does marital status matter in an HIV hyperendemic country? Findings from the 2012 South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey. AIDS Care, 28(2), 234–241. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1080790

- Sidloyi, S. (2016). Elderly, poor and resilient: Survival strategies of elderly women in female-headed households: An intersectionality perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 47(3), 379–396.

- Statistics SA. (2016). General household survey 2015 statistical release P0318. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Stoebenau, K., Heise, L., Wamoyi, J., & Bobrova, N. (2016). Revisiting the understanding of “transactional sex” in sub-Saharan Africa: A review and synthesis of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 168, 186–197. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.023

- Swartz, S., & Van der Heijden, I. (2015). ‘Something for something’: The importance of talking about transactional sex with youth in South Africa using a resilience-based approach. African Journal of AIDS Research, 13(1), 53–63.

- Thornton, R. (2008). Unimagined community: Sex, networks, and AIDS in Uganda and South Africa (Vol. 20). Univ of California Press.

- van de Vijver, D. A., Prosperi, M. C., & Ramasco, J. J. (2013). Transmission of HIV in sexual networks in sub-Saharan Africa and Europe. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 222(6), 1403–1411. doi:10.1140/epjst/e2013-01934-8

- Vivancos, R., Abubakar, I., Phillips-Howard, P., & Hunter, P. (2013). School-based sex education is associated with reduced risky sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in young adults. Public Health, 127(1), 53–57. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2012.09.016

- Wamoyi, J., Stobeanau, K., Bobrova, N., Abramsky, T., & Watts, C. (2016). Transactional sex and risk for HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 19(1), 20992

- Watt, M. H., Aunon, F. M., Skinner, D., Sikkema, K. J., Kalichman, S. C., & Pieterse, D. (2012). “Because he has bought for her, he wants to sleep with her”: Alcohol as a currency for sexual exchange in South African drinking venues. Social Science & Medicine, 74(7), 1005–1012. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.022

- Wilson, K. S., Deya, R., Masese, L., Simoni, J. M., Vander Stoep, A., Shafi, J., … McClelland, R. S. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence in HIV-positive women engaged in transactional sex in Mombasa, Kenya. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 27(13), 1194–1203.

- Xiao, J. J., Chatterjee, S., & Kim, J. (2014). Factors associated with financial independence of young adults. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(4), 394–403. doi:10.1111/ijcs.2014.38.issue-4

- Ybarra, M. L., Korchmaros, J., Kiwanuka, J., Bangsberg, D. R., & Bull, S. (2013). Examining the applicability of the IMB model in predicting condom use among sexually active secondary school students in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 17(3), 1116–1128. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0137-x

- Zembe, Y. Z., Townsend, L., Thorson, A., & Ekström, A. M. (2013). “Money talks, bullshit walks” interrogating notions of consumption and survival sex among young women engaging in transactional sex in post-apartheid South Africa: A qualitative enquiry. Globalization and Health, 9(1), 1. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-9-28