Abstract

Pisa’s Piazza del Duomo is well known as a public space of medieval origin. This article explores its nineteenth-century transformation, presenting the project as one of the most symbolic and evocative examples of Romanticism in Italian urban space. Before this transformation, Pisa, a secondary city of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (Florence was the capital), was still dominated by a conservative society. But Alessandro Gherardesca, the renowned Pisan architect who was in charge of the nineteenth-century works, abandoned the late Baroque tradition, employing instead a neoclassicism in his work. He bridged the cultural gap that existed between the Europe of the Revolutions and the periphery of the Austrian Empire. Then, as he matured, he increasingly embraced the neo-Gothic architecture, and his references, without denying his initial preference for the French masters, were consistent with the exploratory approach of the Enlightenment. The article shows that in his transformation of the Piazza del Duomo, Gherardesca created an idealised image of the original square, one that was in line with British trends.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

What you see is not necessarily what it is!

The square of the Miracles of Pisa, one of the most iconic representation of architecture, thanks to the leaning tower, represents the best of the aforementioned affirmation.

Visited every year by millions of tourists is recognised as a medieval space. However, its nature is more complex: it is in fact a romantic space, conceived in the nineteenth century, around the four medieval monuments, an idealised vision whose roots are entirely political and have to do with the libertarian spirit that spread during the Italian Risorgimento.

The idea of the transformation of the square is due to a single architect, Alessandro Gherardesca, who, despite the reputation of the square, is almost unknown outside the circuits of the historians of the architecture of the University of Florence. This article attempts to bring the figure of Gherardesca to the centre of the architectural debate, and to reveal the socio—political reasons that led to his silent revolution.

1. Introduction: a new architecture for a new state

The Tuscan city of Pisa is less celebrated than its regional capital, Florence, but is well known nonetheless, in large part because of its medieval landmark Bell Tower. The iconic image of the so-called “Leaning Tower”, however, as well as the urban design of the whole complex of the Piazza del Duomo in which it stands,Footnote1 is actually the result of nineteenth-century transformations.Footnote2 These transformations are the subject of this article. To understand their significance, the article considers them in their cultural context, which was underscored by the difficult relationship that existed between Florence and Pisa over centuries. This contributed to the rise of an antagonist spirit in Pisa, which in the eighteenth century fuelled the spread of libertarian and independent thought, and, in architecture, early interest among some architects in revolutionary neoclassicism and then neo-Gothic. The transformation of the Piazza del Duomo demonstrates this early interest in neo-Gothic. The main question becomes: how was a project that was inspired by the principles of Romanticism realised within a cultural environment that, at the end of the eighteenth century, still indulged in late Baroque aesthetics? The article argues that the very particular political conditions of Pisa enabled the more receptive intellectuals—then resident in the city—to embrace the most advanced European culture and to condense, in a relatively short period, the development of both the Enlightenment (represented in architecture by neoclassicism) and Romantic thought (represented by historicist revivalism and the picturesque).

The roots of the fraught relationship between Florence and Pisa are well represented by Dante’s thirteenth-century invectives against Pisa, which at that time was a republic. His attacks culminated in a vision of the city’s apocalypse. It was Florentine propaganda, although war between Florence and Pisa did last for centuries, fought with weapons, literature, arts and architecture. Pisa’s medieval square, the Piazza del Duomo, built purposely close to the city’s borders to be more visible to enemies, represented the richness and power of Florence’s most hated enemy. Florence first conquered Pisa in 1406. That this was concurrent with the advent of the Florentine RenaissanceFootnote3 helps to explain the relevance of architecture, as a symbol, within the conflict. Architects and engineers, including Filippo Brunelleschi, the putative father of the new architecture (Battisti, Citation1981, pp. 232, 233, 336; Cavazza & Melis, Citation2003), were among the first contingents that the Medici rulers sent to Pisa for the construction of fortifications and other Florentine facilities.

In the sixteenth century, after Pisa had lost any claims to independence, Cosimo I de’ Medici commissioned Giorgio Vasari to renovate the Piazza dei Cavalieri (Square of the Knights), the city’s second most symbolic square and the heart of its former republican civil institutions.Footnote4 Vasari’s (and Cosimo’s) goal was to remove any sign of medieval architecture, and in the years that followed, Florentine architects such as Bernardo Buontalenti (Grassi, Citation1838, p. 21), and various foreigners, transformed the medieval forms and spaces using the language of the Renaissance, to represent the Medici family and their ruling class. The removal of medieval buildings from the Piazza del Duomo in the nineteenth century would have a very different impetus from the changes made to the Piazza dei Cavalieri 300 years earlier, although both were intrinsically linked to the political strategies of their day.

When the last of the Medici (Gian Gastone) died in 1737, the Habsburg-Lorraines, one of Europe’s most important and longest-reigning royal houses, assumed responsibility for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (Benjamin, Citation2004, pp. 263–264). The Lorraine Grand Dukes pursued a range of political and economic reforms. They had a particular fondness for Pisa, finally liberating it from Florence’s oppression and elevating it to a sort of second capital. Notable in this regard was Pietro Leopoldo (Peter Leopold, later known as Leopold II, Emperor of Austria), the most enlightened of the Grand Dukes who, between 1765 and 1790, transformed Tuscany into one of the most modern states in the world.

That the Lorraines used functionalist classicism, or rational neoclassicism (considered in eighteenth-century archival documents to be “modern architecture”), as a political tool to demonstrate administrative rigour, in open contrast with the previous Medici administration, has been demonstrated by the key scholars of Tuscan architecture: Carlo Cresti, Gabrielle Morolli, Franco Borsi and Luigi Zangheri.Footnote5 Cultural tensions increased during the Risorgimento, powered by the Lorraines’ policies of decentralisation, which benefitted Pisa and Livorno. Thus, various projects, including the Piazza del Duomo in Pisa, actively re-medievalised the city as a symbolic liberation from Florence and, therefore, from its hated representation in Renaissance architecture. The Piazza del Duomo is not an isolated example. The demolition by Rodolfo Castinelli of the Renaissance portico of the Church of St Sepulchre, along the Arno River, is typical of the modus operandi in nineteenth-century Pisa.

To better understand Alessandro Gherardesca’s important project for the Piazza del Duomo, this article outlines his career and explores his development as an architect, his abandonment of the late Baroque traditions that still lingered in Europe at that time, and his embrace, first of neoclassicism and then, in his mature work in general and in the transformation of the Piazza del Duomo in particular, references from neo-Gothic. These references, without denying his initial preference for the French masters, can be seen as a cultural bridge that was consistent with the exploratory approach of the Enlightenment. The article shows that Gherardesca created an idealised image of the original Piazza del Duomo, following English trends. It presents the transformation project as a symbolic and evocative example of the Romantic interpretation of Italian urban space.

The article also shows that the idea of continuity of architectural styles, as described in the recent literature published in English on Italian architecture, is not entirely applicable to the cities and towns of Tuscany—at least not as concerns the passage from the Baroque to neoclassicism.Footnote6 The Italian peninsula comprised fragmented city states, with distant and often conflicting policies, resulting in cultural differences, nuances and distinct historical trajectories. English language texts have examined the flourishing of a Romantic architecture in the centre of Tuscany (Florence-Siena),Footnote7 and also, albeit it using secondary sources only, the work of Pasquale Poccianti in Livorno.Footnote8 Both are consistent with the discourse of a nation state catalysed by major urban centres (Venice, Turin, Milan, Florence, Rome, Naples etc.). Pisa’s historical development was atypical, however, because the Lorraines moved it towards an autonomous political path, and one that resonated with its pre-Medici past as a republic. The importance of the architects involved in the Grand Duchy’s decentralisation of Tuscany, such as Ridolfo Castinelli (Melis & Melis, Citation1996), Antonio Niccolini,Footnote9 Lorenzo Nottolini (Morolli, Citation1981) and especially Alessandro Gherardesca, in Pisa, Livorno and the Duchy of Lucca, are yet to become known to scholars beyond those who can read Italian.

This article is the first in English to examine the work of Alessandro Gherardesca within its cultural context, including the complex architectural debates that occurred during the Risorgimento. Excluding the aforementioned authors, there are few secondary sources that discuss his work at any length, and none of them are in English. For this reason, the article relies largely on primary sources, including archival documents, manuscripts and nineteenth-century guidebooks.

2. Enlightenment society: breaking with the local tradition

Alessandro Gherardesca (1777–1852), born in the age of Pietro Leopoldo, matured in a cultural environment close to the Enlightenment polygraph Francesco Algarotti and the patriot Filippo Mazzei. He trained as a “polytechnique” engineer and, in reaction against the elitist late Baroque, initially adhered to the French neoclassicism, before developing, in the nineteenth century, a Romantic language that upheld the libertarian impetus of the Italian Risorgimento. Increasing support for the conservation of the Piazza del Duomo during the eighteenth century, and eventually its realisation in the nineteenth century, represented the change of direction from the Medici to the Lorraine Grand Dukes and, later, to the ideals of the Risorgimento, for, despite Gherardesca’s best efforts, the major works were only completed after the unification of Italy, when, amid an atmosphere of post-unitary fervour, the Italian government approved the ambitious programme.

Alessandro Gherardesca was an original architect and ahead of his time, taking every advantage of international experiences and influences during his early development and tutelage. He was lucky to have grown up in Pisa at a time when, under the Lorraine Grand Dukes, the city’s fortunes had once again turned. The Enlightenment also had a significant impact on his early career; it facilitated his break with the past. Importantly for Gherardesca, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, some of the Italian architectural theorists who contributed the most, in terms tracked by Carlo Lodoli, the “Socrates of architecture”,Footnote10 to the replacement of the Rococo with a new classicism, spent time in Pisa. Among them was Francesco Algarotti,Footnote11 who published his Essay on Architecture in the city in 1756 and died there in 1764.Footnote12 This was 13 years before the reconfiguration of the Borrominian St Apollonia Church (designed by Mattia Tarocchi), which is recognised today as the “swan song” of late Pisan Baroque. Then at the turn of the nineteenth century, Vincenzo Marulli was in Pisa, publishing his Treaty on the Architecture and the Neatness of the City, in which he joined with Francesco Milizia in promoting urban planning initiatives such as municipal waste management.Footnote13 Marulli’s presence focused attention on Pisa’s English precedents, with the city’s thermal complex having been inspired by Bath’s Royal Crescent.Footnote14

The Enlightenment philosophers, travellers and artists who spent time in Pisa had an impact on the most receptive of the Pisan thinkers.Footnote15 It can be assumed that Algarotti and Marulli played a role, although unquantifiable, in the cultural development of the young Alessandro Gherardesca. It is also the case that Filippo Maria Gherardeschi, Alessandro’s father and a well-known musician, met Algarotti and established a friendship with him. And in 1785, Filippo became the music teacher of Peter Leopold’s children during the Lorraine Court’s long stays in Pisa.

Historians have only recently discovered the relevance of Pisa as a meeting point for intellectuals involved in the Enlightenment doctrines. Gherardesca, born only a year after Tuscany became the first state in the world to abolish the death penalty, lived a short distance from the house of Filippo Mazzei,Footnote16 who had actively participated in the American War of Independence, and was a close friend of the first American presidents, George Washington, John Adams, James Madison, James Monroe and, above all, Thomas Jefferson, who gave him a part of his Monticello property.Footnote17 A propensity for Jacobinism, leading both father and son to a period in prison, indicates a family continuity in adhering to the cultural legacy of the French Revolution.

Gherardesca was in his early twenties when, in 1801, Napoleon’s troops arrived in Tuscany. Thus, he started his career as a state engineer. His technical training and the works he did in the short period under Napoleon ensured distance between him and the local artistic provincialism. Even though Napoleon was the monarch, he was still seen as the General of the Revolution by the Pisan liberals, because he did not look back to the feudal nobility of the France’s Ancien Régime, and he relied on the support of the bourgeoisie and on Enlightenment principles.

Traces of his French polytechnique background can be found in Gherardesca’s published drawings and writings,Footnote18 including references to Marc Antoine Laugier, Pierre Patte and Jean Nicolas Louis Durand among others, who helped him to break from tradition and to move on towards newer trends.Footnote19 He grasped and assimilated French ideas even in the extreme forms that many considered to be “subversive”. Some of his projects, as evident from the pages of his book The House of Delight, demonstrate an ideal leitmotif of architecture consistent with the “experimental” eighteenth-century matrix. The Triangular House (Gherardesca, Citation1826, tav. X–XI) and Water Storage (Gherardesca, Citation1837, p. 10)Footnote20 are two examples (Figure )).

Figure 1. The Triangular House (1826) and the Water Storage system (1837), designed by Alessandro Gherardesca, are inspired by French and English precedents. Sources: Gherardesca, La Casa di Delizia, X-XI; and Gherardesca, Album, X

Despite his militancy in the French government, even after the restoration of the Lorraines’ legitimate sovereign (Great Duke Ferdinand) and after the Congress of Vienna, Gherardesca was able to progress his career as an architect. He was able to capitalise on his previous experiences to become one of the first to produce neo-Gothic architecture in Italy, while retaining an aptitude, also commenced early in the peninsula, for French modern classicism.

3. The ideology of historicism

After breaking with tradition by employing revolutionary architecture, Gherardesca started thinking, during the 1820s, of architectural models belonging to the Pisan Republic as statements of independence against invaders. In the early Romantic projects, therefore, the reinterpretation of the local architectures is celebrative, while also anticipating the work he would do on the Piazza del Duomo.

The parks Gherardesca designed for the Villa Roncioni in Pugnano, a small village between Pisa and Lucca, and for the Villa Puccini in PistoiaFootnote21 and the Villa Venerosi Pesciolini, are a masterful and unique compendium of Romantic architecture in Italy from the first half of the nineteenth century. Dating from the mid-1820s to the late 1840s,Footnote22 the park of the Roncioni Villa is perhaps his highest architectural achievement in the Romantic language. The prominence of the sixteenth-century villa influenced the distribution of the various component parts of the garden. The large southern part is an intricate patchwork of trees and paths behind the curves of the hills. Built in 1826, with its majestic silhouette, the Bigattiera—a warehouse for silkworm farming—in the northern garden, is Gherardesca’s neo-Gothic masterpiece and, surely, the first Italian neo-Gothic design ever applied to industrial architecture (Cresti, Citation1987, p. 197) (Figure ). Rising from an extensive grassed area, the Bigattiera clearly expresses some of the ideas that Gherardesca would later apply to the design of the Piazza del Duomo, such as the enhancement of the architecture by clearing the surrounding landscape, to isolate an individual building and thus heighten its visibility and impact.Footnote23 Moreover, the Bigattiera was the pivotal architecture around which the existing garden of the villa was reconfigured into a Romantic vision, intended to celebrate a new era: the reformist Lorraine government had lifted protectionism on the Tuscan silk trade in 1819 and during the first decades of the nineteenth century, the number of warehouses for the “scientific” production of silk increased.Footnote24

Figure 2. The Bigattiera (1826), Gherardesca’s Romantic masterpiece and one of the earliest examples of neo-Gothic architecture in Italy. Photograph by the author

In addition to the Bigattiera’s program, the design details also express social and cultural aspirations, interpreted through the Romantic language. To do this, Gherardesca used elements from Pisan Gothic monuments of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, for the city was known for the flowering of a specific type of Gothic architecture at that time, culminating in the church of Santa Maria della Spina and two of the monuments in the Piazza del Duomo—the Monumental Cemetery and the crowning of the BaptisteryFootnote25 (Figure ). At the Bigattiera, the pediment, cusps, mullioned windows and textural stripes that mark the central part of the façade are all similar to a Rathaus, or town hall, and derive from the most significant Pisan Gothic churches and the thirteenth-century civil buildings near the Cathedral, which Gherardesca knew well. The revivalism also became, for Gherardesca, an opportunity to develop an original language, inspired by fashionable English precedents while at the same time borrowing from the local architectural repertoire.

Figure 3. St. Maria della Spina Church, built in the thirteenth century and enlarged in the fourteenth. Gherardesca used elements from Pisan Gothic monuments. Photograph by the author

In addition to style, Gherardesca’s interest in Pisan architecture of the fourteenth century extended to planning, notably the centralised plan attributed to the architect Diotisalvi. Both the Aedicula of the Venerosi Pesciolini garden and the Colognole Tabernacle show a polygonal plan (the first, octagonal, and the second, hexagonal) partly disguised by the small inlet volume with an ogive or pointed opening and a gable on top, which constitutes an additive approach. The vertical lines are accentuated by the pyramidal roof. Also, the different materials and finishing derive from diverse local architectures: like the Santo Sepolcro Church in Pisa, the Tabernacle is more compact and simple in decor, with a brick roof supported by an internal dome; and similar to the chorus cusp of the church of Santa Maria della Spina, the Aedicula is instead characterised by the lightness of the pillar structure and trefoil gables bearing the roof pyramid and by horizontal stripes of different colour stones layered in the Pisan Romanesque style. The Aedicula’s refined decorations partly derive from the ancient tomb of the Della Gherardesca family (no relation to Alessandro Gherardesca). Here it is even more obvious that Gherardesca was interested in an idealised version of the history and not in its accurate reconstruction, to the point of “plundering” an original monument to remount his pieces in a new celebratory setting. Although questionable today, the use of elements taken from ancient monuments was still, in the early nineteenth century, common practice. And, paradoxically, it was also a necessary step in reaching the level of awareness that eventually led to the conservation theory that is known and practised today.

From the point of view of restoration, Gerardesca’s attitude appears ambivalent if not ambiguous. Especially if seen from the outside. In reality it is probably the position of an Italian architect influenced by French culture still permeated by the influence of Viollet Le duc and by the English culture before the birth of William Morris’ and John Ruskin’s positions (Melis & Melis, Citation1996). In the Piazza del Duomo Gherardesca’s position is reflected in three different trends. The first is that of a philological restoration quite advanced for the time. It mainly concerned the reconstruction of some parts of the baptistery. The second is the structural consolidation that involved the work on the tower. The third is the reconfiguration of the square in the logic of stylistic conservation. The latter is closer to the vision of Viollet Le Duc than to the modern interpretation of the materials and forms distinctness operated by Stern and Valadier at the Colosseum and the Arch of Titus (Boito, Citation1893; Brandi, Citation1977; Carbonara, Citation1976; Giovannoni, Citation1946). This project was not even recognised by Gherardesca in terms of conservation, and was clearly indicated as a transformation. In these works, the attention to the transmissibility of the monument is more evident than Gherardesca’s idealised vision of the past. As said at the beginning, this difference is not only the result of a less advanced cultural environment, compared to the Roman one, but, more probably, it is also of a Risorgimento political impulse particularly felt in Pisa.

4. The project for the Piazza del Duomo

Gherardesca was at the peak of his career when, in his capacity as the architect of Pisa’s Opera della Primaziale,Footnote26 he became responsible for the Piazza del Duomo and therefore had the opportunity to transform it. This major project fully committed him for about 15 years from the mid-1830s. In addition, demonstrating his importance beyond Pisa, in 1839 he succeeded Alessandro Manetti as director at the Deputazione dei Lavori PubbliciFootnote27 and the Commissione d’Ornato di Livorno.Footnote28 In this role, he became the highest representative in charge of the implementation of all public constructions in Livorno (Morolli, Citation2002).

As the architect in charge of all works, Gherardesca was able to pursue an overriding idea for the transformation of the Piazza del Duomo. His vision was to create an image of the city immediately prior to its conquest by Florence, when its freedom was lost. This strong ideological push guided the transformation of what was a religious complex into an urban space evoking the golden age of the old republic. Gherardesca used the experience gained in his first Romantic works to create an image of ancient virtues. His goal was to achieve a stylistic purity or unity that never existed in medieval times; it was to be a fictional scenario, focused exclusively on the square’s four principal monuments—the Cathedral of Santa Maria, the Bell Tower, the Baptistery and the Cemetery, all built between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries.

Each of the four had to be freed of ancillary buildings and accretions that had been built later, or even simultaneously, and which impacted upon the vision of unity. In fact, the actual scale of the complex had hitherto been disguised by the small buildings that occupied the spaces between the monuments and the city walls. As well as small buildings, the demolitions included an entire wing of an ancient monastery and a neoclassical church (San Ranierino). Gherardesca replaced them and the other buildings with lawn (Figure ). While the isolation of monuments was common practice in Italy, it was only at the Piazza del Duomo that a new grass lawn filled the newly cleared areas.Footnote29 With the isolation of the monuments and the introduction of an extensive area of lawn between them, each monument, with its white marble walls, became a much bolder landmark. Surrounding orchards and gardens were also acquired and cleared, meaning that the square itself was considerably enlarged, enhancing its impact and effect. Once the new outer limits were decided, Gherardesca reconfigured, in coherent neo-Gothic style, the perimeter buildings which were smaller than the magnificent works at the core, further focusing attention on the centre. His aim was to create a hypothetical medieval complex, where the Gothic Revival of the background scenario contained majestic views of the four major monuments.

Figure 4. View to the south from the tower. Before 1838 we would have seen a wing of a monastery in place of the green hedge and the Church of San Ranierino on the street corner, demolished during the project to isolate the tower. Photograph by the author

The first documents showing the square’s new grass surface date from after 1830, and thus well after the astonishing increase in the amount of empty space around the four monuments. Around 1827, the western edge of the square of the Cathedral was brought from the Baptistery line up to the city walls, with the demolition of a house and an orchard fence that blocked the view of an old Customs building, at Porta Nuova, which was also no longer in existence (Figure ). The comprehensive redesign of the Piazza, including both the isolation of the medieval buildings and the reconfiguration of the perimeter buildings, began in 1838 with the complete reconfiguration of the eastern side, where the Bell Tower is located.

Figure 5. View of the complex from the west side. Before 1827, the point from which the photograph was taken was outside the square and the view would have been obstructed by a wall adjacent to the Baptistery. Photograph by the author

Gherardesca had already designed a new Chapter House, built in 1836–1837 to replace an earlier one. It was sited between the Palace of the Opera del Duomo (the secular institution in charge of maintenance and work at the Piazza del Duomo) and the Bell Tower, and was Gothic Revival to conform to the adjoining buildings (Gherardesca, Citation1837, tav. XXXV).Footnote30 Bartolomeo PolloniFootnote31 described Gherardesca’s key role (Polloni, Citation1837, p. 77, author’s translation):

The small modern building located in proximity to our famous leaning tower was carried out and is about to be completed to the design and direction of the famous Pisan architect Prof. Alessandro Gherardesca, who, in a majestic comparison with the other edifices that surround it, was able to merge it with them with sufficient simplicity, though it does not contain majestic ornaments.

This intervention can be thought of as a transformation rather than a new construction as it retained aspects of the plan of the earlier building. This is evident in the city plan of Pisa before 1836, when the earlier building is visible in “Veduta presa sopra il Camposanto”, published in L’Italie À vol d’oiseau (Bird’s-eye view of Italy) (Guesdon, Citation1850), compared with its revised plan which was published in the Album degli Abbellimenti proposti per La piazza del Duomo (Album of the Cathedral square embellishments) (Citation1864).

In 1838 Gherardesca was in charge of the renovation of the Bell Tower and the design to isolate the key buildings. He proposed to improve the view of the tower (Gherardesca, Sul Campanile, Citation1838, p. 10) by reducing the framework of its handrail (Archivio di Stato di Pisa—ASP, Camera Comunitativa, 788). This project was important because it involved the conservation of the Piazza’s most symbolic monument, and, being the first intervention, was also something of a pilot project. Here Gherardesca combined his two particular strengths: the technical expertise gained during his French Enlightenment education, and his Romantic design aspirations, aimed at emphasising the evocative meaning of the monument through its isolation (Figure ).

Figure 6. New basement of the Bell Tower, built by Gherardesca in 1838, after the demolition of a fence and the excavation works. Photograph by the author

The work was technically difficult because of precarious construction conditions, including a lack of foundations, leading Gherardesca to explore a practice that is more closely aligned with the structural consolidation of twentieth- and twenty-first-century conservation than was usually the case in the first half of the nineteenth century . In this sense, it can be described as modern conservation, helping to ensure the building’s retention for future generations, despite the replacement of many pieces of marble.

Gherardesca’s scientific vocation, consistent with the Enlightenment’s emphasis on rational thought processes, is apparent in the dispute over the lean or incline of the Bell Tower. Despite his ability to design imaginative visions of the Middle Ages, Gherardesca sided with those who believed the lean resulted from a design error, rather than with the many, who, in wanting to enhance the symbolic value of the tower, believed it was intentionally designed to stand at an angle.

In September 1837, the outer layer of a large arc which was at the maximum incline was demolished and renovated, because the whole space between the columns and the arc was disconnected and the material was superficially corroded and oxidised by sea winds (Gherardesca, Citation1838a, p. 18). Visual, structural and design inspection revealed a lack of connections between the outer and the inner walls (Gherardesca, Citation1838a, p. 15; Da Morrona, Citation1821, pp. 41–42). In addition, the decoration of the architectural elements was identical to those of the opposite side. These observations corroborated the thesis of those, including Gherardesca, who had written On the Inclination of the Bell Tower of the Cathedral of Pisa, and the Appendix to the Considerations on the Inclination of the Tower of Pisa Cathedral, and believed that the tower was leaning because of the kinesis or movement of the land (Gherardesca, Citation1838a, p. 10; Grassi, Citation1838; Ceccotti, Citation1838; Menici, Citation1839). According to Gherardesca, if the tower was actually designed to have such a “ruinous” characteristic, it would have been given a strong joint or connection (p. 18), for example, using brickwork instead of molten work (“opera persa”) in the interstitial space between the two claddings (Gherardesca, Citation1838a, pp. 18–19, 25–28; Bellini Pietri, Citation1913, p. 161 and following).

The excavation work carried out under the direction of Gherardesca unearthed not only the steps, but also bases and part of the shaft of the great columns at ground floor level, on the side under the incline (Gherardesca, Citation1838a, pp. 3, 25, Citation1836, Citation1834; Menici, Citation1839; Gherardesca, Citation1839). Unfortunately, when completed, the water suction through a drainage pump encouraged the subsidence, leading to the increased inclination of the tower that, mistakenly, was considered to have stabilised by that time (Pierotti, Citation2007).

In 1839, Gherardesca compiled a new report on the restoration of the monuments of the Piazza, but in July that year, the works were interrupted because of debts incurred and progress was slowed (ASP, Comune F, 20, document dated 19 July 1839). By 1840, he had designed a fence between the Cemetery and the Lion’s Gate (Porta del Leone), including an access door in the Gothic style, which replaced the undertaker’s residence (Casa del Becchino) (ASP, Comune F, 288, documents dated 26 and 29 September 1840).

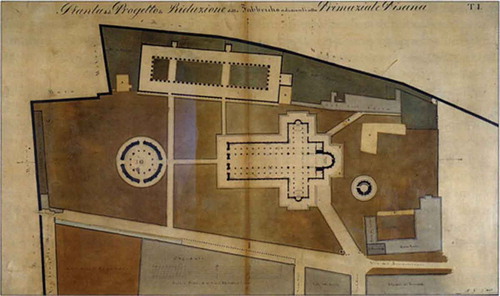

From June 1841, however, much of Gherardesca’s time was absorbed by the ambitious project to transform the entire complex (Progetto di riduzione delle fabbriche adiacenti alla Primaziale Pisana—Design for the transformation of the building adjacent at the Pisan Primatial). On 28 June, 3 years after he received his first assignment, he was finally in a position to present his overall project for the Piazza del Duomo. In the letter accompanying his seven drawings, he wrote (AOP—Archivio Opera del Duomo, 187, file 29, “Letter accompanying the drawings of the design for the transformation of the buildings besides the Pisan ‘Primaziale’”, Author’s translation):

In fulfilment of the Honourable Resolution of the Illustrious Civic Magistrate of Pisa, dated 25 May 1838, with a text I have been provided with by the master builder, the late Sir Bruno Scorzi …, I am handing in the general transformation project of the buildings that surround the lawn where the four Distinguished Monuments stand. The same is developed in seven drawings…. And, seeming to me to have fulfilled the superior commands as my technicality would permit, I have the honour to confirm it with deep deference and respect.

Thus, Gherardesca finally presented the idea to reorganise the whole square through coordinated and systematic action. The drawings showing the Piazza as existing and as proposed represent a precise picture of it after the works on the Bell Tower. In addition to the demolished annexes, the new distribution paths in the Piazza were clearly shown. With this plan, Gherardesca wanted to determine definitely the limits of the Piazza with the construction of a perimeter wall and by planting lines of trees. Changes on the northern side included the restoration of the Opera façade. In two projects on the Levante side, Gherardesca showed the construction of a new Chapter House, to replace the one just completed, in line with the apse of the Cathedral, at the end of a short path leading to the recently acquired area behind the tower. In a letter written in 1851, and following Scorzi in the role of the Head of the Opera, Vincenzo Carmignani confirmed his wish to follow Gherardesca’s idea of planting rows of poplar trees at the edges of the grassy area in order to create a picturesque English landscape (Morolli, Citation2002) (Figure ).

Figure 7. Gherardesca’s transformation project dated from 1841. This drawing shows it in 1941. The square was extended towards the west and east as a result of the works at the Baptistery (1827) and the Bell Tower (1838) and it was already covered by grass (around 1830). Source: Progetto di riduzione delle fabbriche adiacenti alla Primaziale Pisana (AOP, 187, file 29)

In 1853, Pietro Bellini, one of Gherardesca’s most eminent alumni, was commissioned to coordinate the works of the reconfiguration of the Piazza’s buildings. This was 1 year after Gherardesca’s death and 3 years after the reconstruction of the southern door of the Baptistery (ASP, Comune F, 113; Paliaga & Renzoni, Citation1999, pp. 83, 87), which had been extensively modified over the centuries, and was already the subject of radical restorations in 1837 and 1841. As an engineer, both for the City Council and for the Opera Primaziale (ASP, Comune F, 142, 20), Bellini immediately started working on the project based on the influence and the ideas he had absorbed from Gherardesca. Having authored The Design of the New Steps and the Lawn Surrounding the Cathedral in 1857 (AOP, 222), Bellini delivered his project, The Beautification Project of the Piazza del Duomo of Pisa, in 1862, in which he continued to work on Gherardesca’s 1841 concept. That same year, 1862, he also produced the detailed design for the opening of Via Torelli and its extension in the Piazza towards the Tower (ASP, Comune F, 1004). In 1864, when the works were almost completed, Bellini designed the reorganisation of Via San Tommaso, to create a connected path to the new Via Torelli (ASP, Comune F, 141, 204, Report dated 21 May 1864).

5. Learning from Gherardesca’s writing

Throughout this period, Gherardesca was a prolific writer. His various texts help in the understanding of his architectural practice, including the Piazza del Duomo. His theoretical activity starts when he began teaching. In 1826, he became a member of the Academy of Arts of Florence, and the year after, a Professor of Architecture in the Pisan Academy of Arts, where he also became a director. His academic activities resulted in the publication of several books,Footnote32 including drawings, architecture manuals and scientific papers.Footnote33

As an architect’s design works are impacted by competing interests, it is likely that Gherardesca’s writings represent his true ideals in architecture better than his built work.Footnote34 His books reflect Enlightenment ideas and the significant revolution then occurring in modern thought (Wittkower, Citation1974). His two main treatises, The House of Delight of 1826 and the Album of the Architect, the Engineer, etc. of 1837, often referred to simply as the Album, in particular shed light on his apparently opposing theoretical frameworks, the classicist and the Romanticist. In reality, both represent his time and place in the Enlightenment, the former for its most rational expression and the latter as the manifestation of Risorgimento ideals (which in turn depended on rational thinking and reason).

At the same time, despite his engineering background, in his most instructive texts he openly declared his interest in other places, cultures and civilisations. In a chapter of The House of Delight, for instance, describing the evolution trajectory of villas and their annexed gardens, he analysed the relationship between man and nature in Greece, before the Peloponnesian War, in the Roman Republic and in China, according to the well-known scheme used by Robert Castell in the Villas of the Ancients.Footnote35 He even cited, as a reference, British designers including Lancelot “Capability” Brown, William Chambers, Thomas Whateley and Humphrey Repton, who together were largely responsible for the then current ideas on landscaping and were starting to have an impact in Europe. In light of such references, in both style and graphic layout, Gherardesca’s Bigattiera, including the allegorical name of Abbey (Abbazia di San Luca) (Melis, Citation2002b), can be placed in the tradition of John Wyatt’s project for Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire (1796–1807) and Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, Richmond (from 1749 on).

Through The House of Delight, it is possible to read and understand how he saw historicism and the concept of the naturalistic garden, already established across the English Channel but not yet in Italy. Through its theoretical and didactic apparatus and frequent quotations, especially from the work of Francesco Milizia, the main polygraph of the first half of the eighteenth century, it is clear that Gherardesca developed ideas about the “modern villa” that were quite different from current thought in Italian architectural culture. He believed that local country estates had been “for a long time organized tastelessness, and without advantages, using the inopportune style of townhouses” (Gherardesca, Citation1826, p. 3). Demonstrating his Romanticism, he was convinced that, given the nature of the villa, the slavish and ongoing use of the five orders should be rejected. It was necessary to deal instead with “the vague simplicity and grace of forms proper of the countryside, which can arise merely from the imitation of nature”. This was in opposition to French gardening techniques, which showed most overtly the rationalising hand of man. Gherardesca’s criticisms of conventional geometrical gardens become even stronger when he states that “in their gardens then reigned a disgusting graphomania subjecting nature, and vegetation to insipid geometric forms, renouncing to follow in its picturesque varieties which delight us as much as the art which all that wrought, appeared in no place” (Gherardesca, Citation1826, p. 6).Footnote36 While such writing derives from Italian literature, the reference is clearly to England, where such words had become popular in the field of landscaping as highlighted by Humphrey Repton, notably in Edmund Spenser’s book, Fairy Queen (Repton, Citation1816, p. 422; Spenser, Citation1596, p. 345).

Here Gherardesca also confirms that in this historic period, in Italy, Enlightenment and Romantic concepts overlap, even if not explicitly. His adherence to “mimetic theory” recalls Laugier’s primitive hut, even if through the filter of Milizia’s writings.Footnote37 In fact, Milizia pushes his mimetic theory much further than Laugier, promoting two architectural principles related to nature: the Greek intended as an imitation of the original hut, and the Gothic as an imitation of the forest. Staying true to the orthodox Greek-Gothic combination, Gherardesca followed Milizia, for theory, and Repton, for practice (Repton, Citation1816, p. 423). With Repton, the acceptance of classicism, in the design and reconfiguration of villas, is consistent with the predilection for naturalistic gardens framing the buildings. In this respect, Gherardesca’s choice of classical elements is not an alternative to the use of the neo-Gothic stylistic form, but perfectly complementary to it: the Gothic style in some small buildings and a “natural garden”, adapting to the regulative principles of nature. Moreover, classicism in Italy is not a style like the others, but an immense universe to draw from. The use of Palladian elements, in Tuscany, therefore confirms Gherardesca’s interest in English neo-Palladianism, rather than in the original model or its Baroque reinterpretation. Especially after the 1830s, semi-circular and tripartite thermal windows, gables topped by terracotta statues and pinnacles are a constant presence even in his urban projects.

Another aspect to keep in mind about Gherardesca’s architectural pluralism is the different sense that can be attributed to words in their precise cultural context. For example, he again followed Milizia in refusing decoration that did not spring from necessity; for Gherardesca (and Milizia), functionalism did not lead to the elimination of decoration, but only of that which “is done for mere ornament” (Melis, Citation2002b). In all likelihood, his criticism was directed at the still dominant culture that considered the manifestation of style as the only architectural prerogative. Therefore Gherardesca did not refuse neoclassicism as a style—that would be a paradox, if we consider the majority of his work. Rather, he refused its dogmatic use, for example in the excess of geometry, especially in those contexts where the naturalistic element was prevalent.

So once again the architectural reading appears permeated by libertarian ideology and directed against absolutism in favour of the natural principles of positivism. Indeed, although the new political course had finally, with the Lorraines, affirmed the “majesty of the people”, to quote Milizia, cultural residues of the pre-Leopoldina era, especially in the suburbs, continued to influence both clients and architects. And these were the object of Gherardesca’s attacks.

The anti-dogmatic and functionalistic approach to building, extrapolated from the stylistic treatment of its outer surfaces, explains his practice to typically design two versions for each proposed project: a classical one and neo-Gothic one, or an understated rustic version and a richer and more decorated one. Examples include the Chapter House of the Pisa Cathedral, the Academy of Fine Arts in Pisa and the Church of the Carmine. In some Gothic projects, Gherardesca even included classical elements such as friezes and Palladian windows.Footnote38 This was the case for an alternative proposal for Mutual Teaching School (Scuola di Mutuo Insegnamento) where the Gothic rear façade includes a large central Palladian window. Even in the Chapter House façade, there is a similar fusion of architectural elements (Gherardesca, Citation1826, p. 15)Footnote39 (Figure ). Gherardesca’s inconsistent and sporadic use of classical elements in Gothic designs is justified by the ideological dimension of his architecture: the diverse styles from various sources always belonged to the classical or medieval architectural vocabulary; they were not used to conform to any dogma and are quite different from the reactionary tendencies of the social groups who were still opposed to and threatened by Jansenism, Physiocracy and encyclopaedic knowledge.

Figure 8. Design of the new Chapter House, designed by Gherardesca in 1841. The two projects on the Levante side included two versions of the building, both characterised by the presence of Palladian windows. Source: Progetto di riduzione delle fabbriche adiacenti alla Primaziale Pisana (AOP, 187, file 29)

It is clear that in Italy, pre-Risorgimento ideologies were represented through the classical language, while the germ of the Risorgimento resided in Romanticism and historicism, and was given expression in the neo-Gothic, which symbolised the tradition of medieval municipalities and their association with independence and freedom. Hence, Gherardesca applied the style to his buildings according to their level of significance and the desired meaning. In the Mutual Teaching School, for instance, the classicism of the façade is a reflection of philanthropy, disseminated by Enlightenment pedagogic movements across Germany in the eighteenth century, then absorbed by the patriots of the Risorgimento (Morolli, Citation2002). For them, the foundations of a future national state resided in the civic values of society rather than in heroism, and the style was used here to represent such civic values.

6. Limitation of the study

A lack of evidence of direct knowledge between Gherardesca and those he considered his English masters constitutes a limitation of this study. Our current objective is to deepen our research in that direction with the aim of corroborating the hypothesis of a cultural ambient, the Pisan one, particularly lively and active before the unification of Italy, which is the theme of a publication currently underway.

For some years, we have been working in the archive to find documentation that may possibly testify to the existence of a possible Gherardesca’s trip to England. However ambitious, such a journey was more common than one might think, above all because England was considered an elective destination for the Italian patriots of the Risorgimento movement and among them Filippo Mazzei who, as we have stated at the beginning of this writing, has greatly contributed to the consolidation of a circle of intellectual illuminists in the Tuscan city.

No documents have been found to attest to a personal relationship between Mazzei and Gherardesca, although it seems unlikely that they did not know each other as the two belonged to the same political part of the city at a time when it had fewer than 40,000 inhabitants.

However, beyond the field of architecture, we know the protagonists of American independence were considered a model for the Italian patriots of the Risorgimento. Independence from a foreign invader, therefore, the exaltation of Italy’s values represented by the writers of the past, coexisted with the phenomena of the American and French revolutions. The contacts between Italians and Americans took place mostly in London (Mazzei, Citation1846). Direct contacts between Mazzei and Horace Walpole have been recorded by Mazzei (Citation1846) in Vienna, and in Florence, where Walpole visited their common “friend”, “Sir Horace Mann; his Britannic Majesty’s resident at the court of Florence, from 1760 to 1785” (Walpole, Citation1843).

As said, Gherardesca belonged to this cultural context: in 1820 he designed the park and the pavilions of the “pistoiese” Niccolo’ Puccini, who commissioned “the painter Ferdinando Marini to decorate his reading room and, significantly, he reserved the lunettes for the figures of Benjamin Franklin, the Marquis de Lafayette, George Washington, and America portrayed as Minerva” (Tosi, Citation2007, p. 74).

Another point of encounter linking Gherardesca to Mazzei is their common support to Tuscany’s short-term Napoleonic governments (1801–1814) (Morolli, Citation2002, p. 22). The “mecenate” Andrea Vacca’ Berlinghieri, a further representative of the Pisan Enlightenment involved in the Napoleonic outbreak, is again known for his relationships with Mazzei and Franklin (Melis & Melis, Citation1996, pp. 41, 134), and for his frequent relationships with British intellectuals. Educated at the University of Pisa, he became an internationally renowned surgeon, and the first in Italy to follow the school of the Scotsman, John Hunter. He is considered to be the source of inspiration for the character of Victor Frankenstein (Papini, Citation2005), from the experimental surgery he performed, to his interest in galvanism, which he shared with Franklin, and even his personal friendship with John William Polidori and Mary and Percy Shelley, who used to meet, together with Lord Byron, in a sort of cultural and vaguely esoteric circle at his (Vacca’ Berlinghieri’s) residence of Montefoscoli’s park redesigned in a romantic form by another Pisan architect Ridolfo Castinelli.

Thus, even if no evidence can be found of the presence of Gheradesca in England, the presence of English intellectuals in Pisa is instead proven by numerous sources. The Grand-Tour was certainly a milestone for English gentlemen who aspired to the noble knowledge of classical culture, and Rome and Florence were mandatory destination.

More recently, however, it has been highlighted and documented (Melis & Melis, Citation1996) how the British, at the end of the eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century, began to follow alternative routes to those of classicism including cities like Pisan among the favourite destinations. In addition to the names already mentioned, the visits involved William Beckford up to John Ruskin, who considered the Pisan monumental cemetery and the frescoes it contains in, as one of the most inspiring representations of the Middle Ages.

For the foregoing topics, two conclusions can be drawn. The first is that actually Gherardesca’s knowledge of the British treaties that commonly circulated in Italy was more than a hypothesis. The second, however, is that his adherence to the architectural themes originating from England is not always aware of the different political connotation of which these themes are carriers. Gherardesca uses them to reinforce his programmatic beliefs concerning an architecture that recalls the values of the Risorgimento through the language of Romanticism. In England, especially from what seems to be his main reference, which is Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, the aim is to recreate an elitist atmosphere, detached and distant from the themes dear to Gheradesca’s post Jacobinism (Williamson, Citation1995). On the one hand there is the sophisticated dilettantism of a representative of the English ruling class (Mowl, Citation2000), on the other an engineer, trained in the Enlightenment circles of the French Ecole Polythecnique, who becomes a patriot.

Another limitation of the study, which, however, may also have a positive side, is that the lack of secondary sources that address the issue of architectural contamination between Italy and England during the Romanticism which has not allowed a broader discussion on this topic. Thus, the present text can also be considered a first attempt in this direction.

A third aspect to consider on which it would be worthwhile to linger longer in a forthcoming publication concerns the stylistic similarities between the works of Gherardesca and those of his masters to further support the hypothesis of a solid link. It has already been stressed that these could be considered the result of a clear study by Gherardesca made on reference model types as in the case of Durand’s temple (Gherardesca, Citation1837, p. 10). For instance, the trilateral plan (Gherardesca, Citation1826, tav. X–XI) was a topos of the English and French architectural treatises and designs in the second half of the eighteenth century. In his Essai sur l’architecture (Essay on architecture) of 1753, Laugier shows a triangular plan church. Subsequently, within a few years, experiments with triangle plans such as Jean Francois de Neufforge’s Temple de la guerre (Temple of war) (1760) became frequent in France. According to Kruft (Citation1988), towards the end of the eighteenth century, buildings with triangular plans were designed by English architects including John Carter, William Halfpenny, Thomas Archer and John Soane, whose configuration seem very similar to Gherardesca’s attempt.

However, it is not difficult to recognise in the Bigattiera of Villa Roncioni, the profiles of the Gothic buildings painted by J.C. Barrow as Newstsead Abbey (1793; Harney, Citation2013, p. 119).

Also the several small architectures of Walpole’s Strawberry hill like the bridge crossing the deep river and the Gothic aedicules (Harney: 157) are remarkably similar to those designed by Gherardesca for the Venerosi Pesciolini Park. Even the location of the pavilion within the nature and the “design” of the landscape offer a perspective of how close Gheradesca’s design is to that of the older generation of British landscape architects. In the Roncioni, Venerosi Pesciolini and Puccini parks, similarly to Capability Brown’s Sheffield the nature “attacks” the architecture from the sides, with tall trees, while on the front a green lawn wedge provides a certain airiness to the façade. And it is equally difficult not to notice that the themes treated by Gherardesca in his two principal treatises are superimposable, even in the use of architectural precedents to the treaties of two generations of English authors from Robert Castell to Humphry Repton. Particularly in the Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1816), there are clear references to the mimetic toes expressed a decade later by Gheradesca, which prove that he knew such texts or that evidently the ideas of the English were widespread in Italy more than we have thought.

This part of the research will need future insights that we hope to complete in the near future.

7. Conclusions

This article has examined the nineteenth-century transformation of Pisa’s Piazza del Duomo by the renowned architect Alessandro Gherardesca. He was undoubtedly the one who, with countless ideas and interventions, gave the medieval Piazza the remarkable Romantic quality for which it is known today. He cleared the complex of ancillary buildings and structures, introducing open space, the extensive grassed landscape and thus the uninterrupted vistas of the key historic monuments. What exists as a result of his work is a “modern” interpretation of a medieval space. It is distinct and memorable, but its history is not well known and till today a dedicated publication on the nineteenth-century works is yet to be written.

The article has located the interventions within the broader contexts of Enlightenment thinking and development, including education and travel. Gherardesca had various formative experiences that shaped his thinking. This included his early training, but also he was very well read and had contact with key thinkers of the Enlightenment who resided in Pisa for periods of time. In the early part of his career, he worked as an engineer and developed technical expertise. He then absorbed the influences of French neoclassicism and produced early work that exploited similar geometries and reduced ornamentation. But it was as an early proponent of Romanticism in Italy that he earned recognition. Many of his works combine attributes of the classical and the Romantic, culminating in his 15 year project to transform the Piazza del Duomo into a revitalised and symbolic landmark for Pisa and an idealised medieval landscape.

Many of the illustrious Romantic visitors to Pisa, such as Leo Von Klenze, knew the Piazza del Duomo in the middle of its transformation (Von Klenze’s well-known painting of the Pisan Cemetery, kept in the Neue Pinakothek of Munich, was painted in 1858).

Others, like John Ruskin (who visited in 1872) and Camillo Sitte (about 1889), went to Pisa only after the works were completed. Yet, they all saw, in that developed urban mosaic, an idealised representation, paralleling the medieval version of the Athenian Acropolis. The description given by Camillo Sitte in The Art of Building Cities, published in Vienna in 1889, confirmed: “A true masterpiece, comparable only to the Acropoli of Athens… The citizens collected here all the monumental works of sacred art, remarkable for breadth and richness: the impressive cathedral, the bell tower, the baptistery, the incomparable Campo Santo. In return, they excluded all that might seem trivial or profane. The square so rich in works of art exerts an inexpressible charm…. Here, peace and silence reign, and the harmony of impressions allows us to fully enjoy the works of art and understand them”.

In this sense, Gherardesca achieved his objectives. Furthermore, John Wyatt, Horace Walpole, Byron, Shelley and Keats were all fascinated and inspired by the medieval mysticism of the frescoes on the internal walls of the Pisan Monumental Cemetery, producing something of a game of mirrors, given Gherardesca’s interest in the work of the English designers and writers.

Is Gherardesca therefore a neoclassical Romantic architect? This apparent contradiction can be explained by the persistence of the late Baroque in Tuscany, symbolising, as mentioned in the introduction, the regime of the Medici’s Granduchy, to those who, like Gherardesca, grew up with the ideas of the Revolution. His cultural orientations as well as the influence of his masters, make Gherardesca a complex and multifaceted architect, whose artistic talent and strength of technical and technological knowledge are not a dichotomy. Thus, the classicism of the Revolution and the revivalism are complementary elements of a continuous process of intellectual exploration. It is, however, the revivalist architecture that provided Gherardesca with an emerging profile within the history of architecture of that period in Italy. Nevertheless, it was only in 1987 that architectural historians recognised his pioneering role in the importation of the English trends into Italy (Cresti, Citation1987).

Gherardesca’s immersion in the cultural context of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Pisa corroborates the theory that in the Modern Age, the most significant steps were taken by artists who were able to look beyond their own horizons. Gherardesca belongs to the group of architects who were not bounded by popular and conventional constraints or by the limitations of their contemporary practice, but instinctively and consciously chose to cross national borders and theoretical boundaries, through the creation of innovative masterpieces. Gherardesca was not interested in following the contemporary professional practice of local or regional architects, but was highly influenced by theorists and innovators. He was capable of making real revolutions in the discipline of architecture, and crossing the borders of nations and established practice by exploiting his academic inclination, design mastery and international orientation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alessandro Melis

Dr Alessandro Melis has taught architecture at the University of Portsmouth since 2016 and, at the University of Auckland since 2013. Previously, he was a guest professor in Austria (die Angewandte Vienna) and Germany (Anhalt University Dessau). He has been honorary fellow at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and a keynote speaker at the China Academy of Art, at the MoMA New York and at the Venice Biennale.

Julia Gatley

Dr Julia Gatley is a graduate of Victoria University of Wellington and the University of Melbourne. She is an architectural historian, and worked as a New Zealand Historic Places Trust conservation advisor and then as a lecturer at the University of Tasmania before taking up her position at the University of Auckland in 2006.

Notes

1. The Piazza del Duomo is better known by the popular name of Piazza dei Miracoli (Field of Miracles), a description given by Gabriele D’Annunzio (D’Annunzio, Citation1903).

2. The literature on the Piazza’s medieval works is extensive and well known, whereas that on the nineteenth-century works is not. Even recent publications, such as Eamonn Canniffe’s The Politics of the Piazza: The History and Meaning of the Italian Square (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2012), which presents the history of Italian urban spaces traced through their relationship with political and cultural change, focuses on the alleged medieval features of the Piazza del Duomo without considering the radical and politically charged nineteen-century interventions. That said, through the analysis of original documents from the thirteenth century, archaeologist Fabio Redi discusses the presence of buildings in the square’s interstitial spaces (Redi, Citation1991).

3. 1401 and 1418 are the two key dates, those of the competitions for the door of the San Giovanni Baptistery and for the Santa Maria del Fiore dome.

4. From the middle of the sixteenth century, the transformation of the Piazza dei Cavalieri and its new political role contributed to the reduced importance of the Piazza del Duomo.

5. Terry Kirk and subsequent scholars all rely on these authors (and not just with regards to Tuscany). Among them, Cresti (Citation1987) is the first to have brought the anticipatory and innovative character of Tuscan architecture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to international attention. Another frequent reference is: Mauro Cozzi, Franco Nuti and Luigi Zangheri, Edilizia in Toscana dal Granducato allo Stato unitario (Construction in Tuscany from the Grand Duchy to the unitary state) (1992).

6. Terry Kirk, with his two-volume The Architecture of Modern Italy (2005), helped to overcome the conventional idea of the styles as turning points, or even as revolutionary changes, bringing them into a path of continuity. Kirk’s contribution is essential for understanding the Italian mainstream architecture that coagulates around its main cities. His interpretation has been followed by other researchers. Earlier texts, for example on the artificial use of terms such as “Mannerism”, include Hopkins’ Italian Architecture: From Michelangelo to Borromini (2002), Frommel’s, The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance (2007), and Italian Architecture of the 16th Century (Rowe & Satkowski, Citation2002).

7. Architects considered in this context are usually Agostino Fantastici, Luigi De Cambray Digny, Nicolo’ Matas and Gaetano Baccani. Among these, Fantastici was certainly the most talented. Carlo Cresti (Citation1992) refers to him as the Italian Schinkel, and Kirk (p. 156), as “a fervent Romantic genius”. To date, international scholars have all relied on Cresti’s text. Cresti, Gabriele Morolli and others conclude that Fantastici’s ideas were closer to those of Gherardesca than anyone else. The two were colleagues at the Ombrone Department and shared interests such as the work of Domenico Lucchi (Cresti, Citation1987, p. 12; Gherardesca, Citation1837).

8. Emil Kaufmann compared Poccianti’s Cisternone to the best works of Boullée and Ledoux (Kaufmann, Citation1966, p. 142). Kaufmann’s work on Poccianti had been very influential (Middleton & Watkin, Citation2001; Kirk, Citation2005, p. 158; Borsi, Morolli, & Zangheri, Citation1975; Gurrieri & Zangheri Citation1974; Matteoni, Citation1992, Citation2000).

9. The case of Niccolini is emblematic. Despite his international reputation, his work in Pisa is unknown in the literature. His work is only known from 1807, when he moved to Naples.

10. This is the way Algarotti usually referred to the Franciscan friar, Carlo Lodoli (Sica, Citation1985, I, p. 213). Lodoli, who died in 1761, is considered the most revolutionary eighteenth-century Italian theorist and the first advocate of functionalism in Italy. Since he did not leave any writings, his theories are known only through the publications of Francesco Algarotti and Andrea Memmo.

11. Algarotti’s writings were printed while Lodoli, his teacher, was still alive. Those writings, such as the Essay on Architecture and the Letter on Architecture, are relevant because they provide us with both Lodoli’s thoughts and, simultaneously, the contrary thinking of his contemporaries. Algarotti, who was a brilliant thinker but was also conservative and a traditionalist, interpreted the Venetian monk’s assertions as an attack on the soundness of Vitruvian theory.

12. Algarotti, who was probably already sick, definitely spent the winters of 1762, 1763 and 1764 in Pisa. On 17 December 1762, in a letter to Voltaire, he extolled the salubrious air quality of Pisa, consistent with emerging ideas on health. Among other things, Algarotti compares the Tuscan city to Athens (Segrè, Citation1922, pp. 48–49). Camillo Sitte also did the same, one century later.

13. Like the other protagonists of rational neoclassicism, Francesco Algarotti and Andrea Memmo, Milizia was, for a period, among the supporters of Lodolian doctrine. He published the first Italian architectural history, Vite de’ piu’ celebri architetti d’ogni nazione e d’ogni tempo (Lives of the “most” famous architects of all nations and of all times) (1768), followed by fundamental treatises including Del teatro (About the theatre) (1772), Principi di architettura civile (Principle of civil architecture) (1781), Dell’arte di vedere nelle belle arti del disegno (About the art of seeing through the fine arts of drawing) (1787) and Dizionario delle arti del disegno (Dictionary of the arts of drawing) (1787). Gherardesca did not show particular interest in urban planning during his career, but his writings do include consideration of urban matters, probably deriving from both Milizia and Patte, who had exerted great influence in this field. Another interest clearly deriving from Milizia is the modern conception of the theatre, although this is beyond the scope of this article.

14. In 1742–1746, Giuseppe Ruggieri (assisted by Gaspero Maria Paoletti) designed the Pisan thermal complex of S. Giuliano, clearly inspired by Bath’s Royal Crescent, designed by John Wood and John Wood Jr. a few decades earlier.

15. Among others, Alfieri and Goldoni spent long periods in Pisa. The influence of their writings is readily apparent in the themes of nineteenth-century building decoration and by the suburban villas inspired by Arcadia.

16. Mazzei died in Pisa in 1816 and until that time remained in correspondence with Jefferson. Mazzei was an inspiring personality. Thomas Jefferson translated some of his writings into English. He was so influenced by them, that he translated entire sentences in the American Declaration of Independence (https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/mazzei-philip). John Fitzgerald Kennedy, in his A Nation of Immigrants (1958), is probably the first who emphasised Mazzei’s role as an ideologue in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence and not simply a spokesman of Jefferson’s revolutionary ideas. Only in 1994, however, did a US Congressional resolution acknowledge Mazzei’s primary role (Critcher Lyons, Citation2013).

17. While his political role in the American Independence has been widely recognised, and despite the recent studies on Italian artists in Washington such as The Italian Legacy in Washington, DC: Architecture, Design, Art and Culture (Molinari & Canepari, Citation2009), Mazzei’s contribution in creating Washington’s community of Tuscan sculptors (Mazzei, Citation1846, II, p. 185) is not well known in English language texts.

18. His interest in the treatises, and especially in the École Polytechnique model, is shown in writings such as Sulle Cause e ripari alla mobilità dei terreni (On the causes and repairs to the mobility of land) and Considerazioni Militari e Politiche sulle Fortificazioni del Generale Michaud (Darçon) and (Considerations on Political and Military Fortifications of General Michaud (Darcon)). Published in 1849, the latter is mostly based on his translation of Michaud d’Arçon, Considérations militaires et politiques sur les fortifications (Paris: Imprimérie de la Republique, 1794).

19. Paolo Bertoncini Sabatini also assumes a path of knowledge, even direct, with Schinkel, whose influence is visible in Gherardesca’s teaching methodology at the Academy of Fine Arts in Pisa and in the editorial choices for his Album, both in format and content, referring to the Architektonischer Sammlung Entwürfe (Collection of architecture drawings) by the German architect (Bertoncini Sabatini, Citation2012, pp. 105–118).

20. In the Water Storage design, published in the Album, Gherardesca proposes a more “revolutionary” project. Its geometric solution is unequivocally inspired by Durand’s Temple Decadaire where the collaboration with Boullée was evident. In his text, Gherardesca explicitly refers to Durand’s Leçons d’Architecture (Lessons of Architecture).

21. Kirk, refers to Gherardesca “as a jack of all styles” (p. 157) and as a garden designer. It derives from Monumenti del Giardino Puccini (Monuments of the Puccini Garden) (Contrucci, Fioretti, & Puccini, Citation1845). Gherardesca was in fact involved, during those years, in the design of the Roncioni and Venerosi Pesciolini Gardens, and it really was his habit to propose a classical version and a Gothic version for particular projects, such as the Scuola di Mutuo Insegnamento in Pistoia. A more recent chapter by Alessandro Tosi provides a wider overview of Puccini’s project within the context of Romantic gardening in Tuscany, especially highlighting the position of the other Pisan architect, Ridolfo Castinelli (Tosi, Citation2007, pp. 71–73).

22. Some scholars claim that the work was completed in 1831. In The House of Delight, Gherardesca states that the Bigattiera was already built, which means construction before 1826, if the project was included in the book since its first edition.

23. “This new warehouse”, Gherardesca wrote, “standing at the left of the large field on which lies the ancient Villa, announcing itself with an Abbey’s aesthetics, frames a great picture with various crops covering the pictorial slopes of the mountain, with the contiguous Bosco, and with the well-organized garden” (Gherardesca, Citation1826, p. 13, author’s translation).

24. The indicated dates are especially significant if we consider, for example, the emphasis Kirk and others gives to Giuseppe Jappelli, for his role in the spread of “the Romantic ideal” and his 1831 masterpiece, the Caffe’ Pedrocchi in Padua (Kirk, pp. 127–135).

25. Regarding Gherardesca’s works on the Baptistery and the conservation project of the Church of Santa Maria della Spina, see (Melis & Melis, Citation1996). Gherardesca had also carried out the conservation of the church of San Michele in Borgo (near where he lived) and of Piazza Santa Caterina where his house was located.

26. Founded in 1063, the Opera della Primaziale is the organisation overseeing the construction and upkeep of the various monuments in the Piazza del Duomo. It still operates today.

27. The Deputazione dei Lavori Pubblici di Livorno is the technical unit of the Livorno Council in charge of the design and construction of public works.

28. The Commissione d’Ornato di Livorno is the board of experts that evaluates the architectural quality of the projects presented to the Livorno Council. Livorno was in those years the fastest growing city in Tuscany, thanks to the Lorraine decentralisation policy, and also one of the more important ports in the Mediterranean.

29. Moreover, the inclusion of this action in a broader reconfiguration (in the medieval sense) of the whole perimeter of the area, is a clear link to the political vision of the Risorgimento, rather than to the conservation practice of isolating ancient monuments such as the Roman ruins.

30. “Figure is the main façade of the building which is currently under construction at the illustrious Pisan Primatial, intended for the use of Chapter residence”. See also Descrizione storica e artistica di Pisa (Grassi, Citation1838, p. 3).

31. Bartolommeo Polloni was a Pisan engraver of the nineteenth century. His city views, accompanied by accurate descriptions, are important evidence, for the historian, of the city as it was in the first half of the nineteenth century.

32. Among the writings that came down to us, La Casa di Delizia (The House of Delight) and Album dell’architetto e dell’ingegnere (referred to as the Album) are the most significant in terms of theory. Other writings include technical publications probably aimed at teaching such as La geometria applicata all’agrimensura, livellazioni e divisione di terreni (The geometry applied to land surveying, leveling and subdivision of land) (1831), Memoria sulla tromba aspirante sottratta all’azione della gravita’ atmosferica del sig. Champion e descrizione di un’altra specie di tromba (Memory on aspiring drilling without the atmospheric gravity action by Mr. Champion and description of another kind of drilling) (1834), Architettura Legale (Legal Architecture) (Florence: Batelli, 1838) and, as already mentioned, Dialogo sulle cause, ripari alla mobilità dei terreni (1836). Although technical, the previously mentioned five publications on the leaning tower represent the argumentative nature of a part of the nineteenth-century literature. The Monumento a Pietro Leopoldo Granduca di Toscana eretto a Pisa (Monument dedicated to Peter Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany, erected in Pisa) (1833) is a celebrative publication of his design for the base of the monument dedicated to Pietro Leopoldo, erected in Piazza Santa Caterina, in Pisa.

33. Background information on Gherardesca comes directly from his memoirs, “Ricordi del Gherardesca” (“Memories of Gherardesca”), ca 1840 (ASP, Comune F, 90).

34. Gherardesca was often called in to change the appearance of existing buildings in both urban and suburban areas, and rarely worked on dimensionally significant new constructions.

35. In The House of Delight, Gherardesca also typically refers to Pliny’s garden.

36. The Italic is used by Gherardesca, in his text, to indicate a quote from Torquato Tasso, Garden of Armida (“l’arte che tutto fa nulla si scuopre”).

37. “Art should be so hidden that you believe to see simple nature, and sometimes its bizarre claims. The error of people who believe they are expert in taste is the desire of art in all the things, and to never be happy if art does not stand out. The real taste is to hide it, especially in the works of nature”. Milizia, Part Two, Art. Gardening. Quoted by Gherardesca (Citation1826, p. 6, author’s translation).

38. The coexistence of styles could constitute a further element of interest to Gherardesca, as an anticipator of eclecticism. However, he never went beyond the use of the Gothic and classical styles, confirming his wholehearted, while unorthodox, commitment to the doctrine of Milizia.

39. In the Chapter House the attitude of Gherardesca as “Jack of all styles” returns (Kirk, Citation2005, p. 157). The motivations of this “double face” approach have been analysed by Morolli (Citation2002).

References

- Album degli Abbellimenti proposti per la piazza del Duomo. (1864). Album of the proposed embellishments of the Cathedral square. Opera del Duomo di Pisa, Pisa: Nistri.

- Battisti, E. (1981). Filippo Brunelleschi. Milan: Rizzoli.

- Bellini Pietri, A. (1913). Guida di Pisa (Guide of Pisa). Pisa: Vallerini.

- Benjamin, A. (2004). Princes and Territories in Medieval Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bertoncini Sabatini, P. (2012). “Le dimore pisane nell’opera di Alessandro Gherardesca: Sulle orme di Schinkel alla ricerca delle elettive patrie dell’anima” (“Pisan dwellings in the work of Alessandro Gherardesca: On Schinkel’s footsteps in search of soul elective homelands”). In G. Morolli (Ed.), Le dimore di Pisa. L’arte di abitare i palazzi di una antica Repubblica Marinara dal Medioevo all’Unità d’Italia (The dwellings of Pisa. The art of living in the palaces of the ancient maritime republic since the Middle Ages to the Unification of Italy). Florence: Alinea.

- Boito, C. (1893). Questioni pratiche di belle arti. Restauri, concorsi, legislazione, professione, insegnamento. Milano: Hoepli.

- Borsi, F., Morolli, G., & Zangheri, L. (1975). Firenze e Livorno e l’opera di Pasquale Poccianti nell’eta’ granducale (Florence and Livorno and the work of Pasquale Poccianti in the Grand Ducal age). Rome: Officina.

- Brandi, C. (1977). Teoria del restauro. Torino: Einaudi Editore.

- Carbonara, G. (1976). La reintegrazione dell’immagine. Roma: Bulzoni.

- Cavazza, E., & Melis, A. (2003). Le Fortezze (The Fortresses). Pisa: ETS.

- Ceccotti, G. (1838). Replica all’autore dei riflessi sopra l’inclinazione della Gran Torre di Pisa (Reply to the author of reflections on the inclination of the Grand Tower of Pisa). Pisa: Pieraccini.

- Cresti, C. (1987). La Toscana dei Lorena (The Tuscany of the Lorraines). Cinisello Balsamo – Milan: Pizzi.

- Cresti, C. (1992). Agostino Fantastici, Architeto senese (Agostino Fantastici, Sienese architect). Turin: Allemandi.

- Critcher Lyons, R. (2013). Foreign-born American Patriots: Sixteen volunteer leaders in the revolutionary war. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- D’Annunzio, G. (1903). Forse che si forse che no (Maybe yes, maybe not). Milan: Treves.

- Da Morrona, A. (1821). Pisa antica e moderna del nobile Alessandro da Morrona patrizio pisano Pisa (Ancient and Modern Pisa of the noble Alessandro da Morrona patrician of Pisa). Pisa: Ranieri Prosperi.