Abstract

Community gardens are receiving increasing attention as a source of locally available and sustainable food, and aim to increase food security. Engagement and commitment from the volunteer workforce in community gardens is an important contributor to their success and sustainability. University-based community gardens are a distinct type of community garden. Little is known about barriers and enablers to volunteer engagement in this setting. This qualitative study aimed to explore the experiences of volunteers of the Moving Feast, a newly established university community garden in Queensland (Australia), particularly the perceived benefits and the barriers and enablers influencing their engagement. Focus groups were conducted with 14 of the volunteers. Key enablers included interactive communication, personal motivations and garden-related activities embedded in university course curriculum. Common barriers to volunteering included competing priorities, the timing of sessions and activities, and a perceived lack of communication and information. Social and educational benefits emerged as the main benefits received, with an emphasis on future career benefits among student volunteers. The findings bring to light implications for volunteer recruitment, engagement and retention, particularly in university student cohorts, that may assist management and ensuring sustainability of university-based community gardens.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Engagement with community gardens is an area of public health recognised as a means to promote and improve health, create positive social outcomes and promote sustainability. In Australia, community gardens occur in a variety of settings and more recently within university settings. The Moving Feast is a university-based community garden at the University of the Sunshine Coast. The garden was established to improve food security and embed a sustainable food supply on campus. The Moving Feast aims to engage staff and students in the construction, maintenance and enjoyment of the garden. This article describes the barriers and enablers to student volunteer engagement and the perceived benefits received from involvement in the newly established garden, based on data gathered via focus groups. Our findings and their implications may help to improve future management of volunteers in the Moving Feast and provide insight for universities establishing community gardens on their campuses.

1. Introduction

Community gardens are receiving increasing attention as an avenue to provide a locally available and sustainable food source to localised communities. Community gardens can promote and improve health (Armstrong, Citation2000; Kingsley, Townsend, & Henderson-Wilson, Citation2009; Wakefield, Yeudall, Taron, Reynolds, & Skinner, Citation2007), increase food security (Twiss et al., Citation2003; Wakefield et al., Citation2007), create positive social and community outcomes (Firth, Maye, & Pearson, Citation2011; Kingsley & Townsend, Citation2006; Teig et al., Citation2009; Wakefield et al., Citation2007) and promote ecological, socio-cultural and economic sustainability (Holland, Citation2004; Turner, Citation2011). Broadly speaking, a community garden is described as a plot of land on which individuals can create gardens and grow produce within a communal setting (Kingsley et al., Citation2009; Pearson & Firth, Citation2012). In the Australian context, the Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network (ACFCGN, Citation2017) has defined community gardens as, “places where people come together to grow fresh food, to learn, relax and make new friends.” In Australia, it is estimated there are well over 500 community gardens (ACFCGN, Citation2017). These have been established in a variety of settings including urban and public spaces (Kingsley et al., Citation2009), primary schools (Henryks, Citation2011; Townsend et al., Citation2014), prisons (Pudup, Citation2008), and in more recent times, universities (ACFCGN, Citation2017).

There is great diversity in the structure and organisation of community gardens. There is no one “right” model of garden, rather the design, model and management can vary depending on the community it is intended to serve (ACT Government, Citation2012). Within Australia, operating models range from a communally run garden where gardeners share and are responsible for the entire garden, to plot or allotment gardens where gardeners pay a fee for their own garden plot (Shallue, Citation2013). Other models used in Australia also include: council-volunteer or council-managed gardens; agency community gardens where the garden is established by an agency for their clients’ needs; education and research hubs that provide multiple-use facilities on a large scale such as the Centre for Education and Research in Environmental Strategies (CERES) in Melbourne (Hatton, Citation2015); and school kitchen gardens in primary schools where they are used as learning laboratories or outdoor classrooms (Graham, Lane Beall, Lussier, McLaughlin, & Sherizidenber-Cherr, Citation2005). University-based community gardens are another subset of the community garden movement that is a more recent initiative across Australia. At the time of writing, in Australia there were over 12 established university-based community gardens with several more planned for the future (Thompson & Anderson, Citation2012).

University-based gardens are a distinct type of community garden and may access a diverse range of stakeholders, skills and knowledge by incorporating an interdisciplinary approach (Scoggins, Citation2010). Typically, horticulture and landscaping disciplines are the key drivers (Scoggins, Citation2010) although other areas may include environment, sustainability or public health. A distinguishing feature is that universities provide an established community with a locatable group of potential volunteers (Esmond, Citation2000), namely staff and students. In the university setting, recruiting, managing and sustaining the volunteer workforce is a key challenge that volunteer-driven projects such as community gardens must overcome (Gaskin, Citation1998; Manthorpe, Citation2001). University student volunteers in particular are a unique demographic (Gupta, McEniery, & Creyton, Citation2013) and it is well recognised that student volunteers can be hard to engage and retain in volunteer activities (Esmond, Citation2000). Therefore, having a firm understanding of the factors that influence volunteer engagement is important for those leading and managing university-based gardens.

There is a plethora of research on general volunteerism exploring the factors that influence recruitment, engagement and retention of volunteers including motivations, benefits, barriers, and satisfaction. The perceived and actual benefits of volunteering have shown to influence volunteer engagement and retention through initially acting as an incentive and later as a reward for participation (Batson, Citation1991; Wanderman & Alderman, Citation1993). It is also well understood that contextual (or environmental) factors and personal barriers that hinder one’s ability to participate negatively impact on the volunteer experience and satisfaction (Dwiggins-Beeler, Spitzberg, & Roesch, Citation2011) and subsequently their intention to remain with the organisation (Henryks, Citation2011; Miller, Powell, & Seltzer, Citation1990). In the community garden context, much of the published research on volunteerism within the community gardens has focussed on urban and public gardens or primary school kitchen gardens and have explored motivations and reasons for joining (Haynes & Trexler, Citation2003; Henryks, Citation2011; Northrop, Wingo, & Ard, Citation2013; Teig et al., Citation2009) alongside the benefits to both the individual and to the community (Hale et al., Citation2011; Henryks, Citation2011; Kingsley et al., Citation2009; Teig et al., Citation2009). Few studies have identified the enablers and barriers to volunteer activity and participation in community gardens (Haynes & Trexler, Citation2003; Kingsley et al., Citation2009).

Within the university-based garden context, some barriers and challenges around maintaining a trained and dedicated volunteer and workforce especially with high turnover from graduation of student population (Duram & Williams, Citation2013) and academic calendar resulting in not having volunteers during semester breaks (Brown-Fraser, Forrester, Rowel, Richardson, & Spence, Citation2015) have been identified in the United States. Little has been published about the aspects (namely barriers, enablers and benefits) that affect the volunteer engagement in Australian university-based community gardens. Given the unique context of a university-based garden, the aim of this qualitative exploratory study was to describe the benefits, barriers, and enablers to engagement experienced by volunteers in a newly established Australian university-based community garden. The findings and their implications for volunteer engagement, management and the sustainability of university-based community gardens are discussed.

2. The moving feast: case study

The Moving Feast is a university-based community garden at the University of the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia. During 2012, the concept of the Moving Feast developed from a series of Community and Public Health Nutrition placement projects by nutrition and dietetics students investigating food insecurity and fruit and vegetable consumption on campus. The overarching goal of the Moving Feast was to increase student and staff access to and availability of fruit and vegetables on campus and support a sustainable food supply on campus.

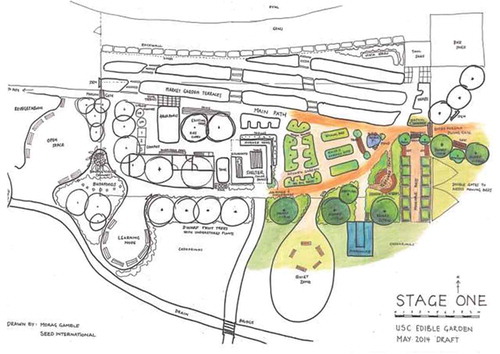

The development of the Moving Feast was led by the Nutrition and Dietetics department in collaboration with various disciplines including Engineering and Occupational Therapy. Following extensive consultation and planning in 2013, approximately 600 m2 of campus land for the garden was secured. Recruitment of staff and student volunteers and initial garden development commenced from January 2014 (Figure ). The first garden bed was established in June 2014 and in the remaining months of 2014 leading up to the time of this research project a series of working bees (communal gardening sessions) for planting and maintaining the beds were held.

The type of community garden model used by the Moving Feast is a shared garden where volunteers share in the responsibility for the establishment, development and maintenance of the garden. The Moving Feast is open to any and all students or staff members who are interested in volunteering. While membership is somewhat formalised through a registration process, there is are no membership fees or financial costs to volunteer. The funding, decision-making and project management components are managed by the Moving Feast Steering Committee, which is made up of staff from the university. To assist with the garden’s day-to-day operation, three volunteer-based teams were developed (referred to as Pods) and six of the registered volunteers (four students and two staff volunteers) were appointed in team leader roles for each Pod.

Students and staff continue to be recruited as volunteers on an on-going basis and those registered are kept informed of volunteer opportunities and events such as gardening workshops and general garden activities. Academics have linked the garden into curriculum through student placement projects and research projects. Understanding the factors that surround volunteer engagement was of interest to the Steering Committee and project leaders, as the model of the Moving Feast was reliant on a supply of volunteers to help with the establishment and on-going maintenance into the future.

3. Methods

A qualitative descriptive study (Creswell, Citation2003) was undertaken using focus groups with volunteers of the Moving Feast. Aspects of volunteer engagement were explored which included the enablers and barriers to volunteer engagement and the perceived benefits of volunteering.

The data for this study were collected between November 2014 and February 2015. At the time of data collection, 106 volunteers had registered with the Moving Feast since January 2014. Eighty-six of the 106 registered volunteers (81%) were students at the university, representing less than 1% of the total university student population (in 2014, 9652 students were enrolled at the Univerisity of the Sunshine Coast (USC)). The other 20 registered volunteers were either full time or part time university staff. As the garden was in the initial development phase, volunteer participation at the time of this study was primarily through gardening working bees, group meetings and engaging through online communication such as emails and social media.

3.1. Sample & recruitment

Participants (≥ 18 years) were recruited (convenience sampling) from the pool of the Moving Feast registered volunteers (n = 106). All registered volunteers who were 18 years or older were invited to participate via email and social media. Those who expressed interest were scheduled to attend one of five focus group sessions. Written consent was obtained from participants prior to commencement of the focus group. Ethics approval was granted from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of the Sunshine Coast (Ethics approval number: S/14/654).

3.2. Sources of data and methodology

The design and implementation of focus groups followed the methods suggested by Krueger and Casey (Citation2009). Prior to data collection, moderator training was undertaken. Two researchers were present at the focus groups. One researcher acted as moderator and facilitator, while the other took notes on a whiteboard. The whiteboard notes were used as a prompt for the participants when summarising the content discussed at the close of the session.

Focus group questions were designed to (1) determine and understand the enablers and barriers to volunteering and (2) understand the perceived benefits received from volunteering. The primary questions asked are found in Table . Additional questions were asked as the focus groups were conducted to follow up on answers or to further explore their perspectives and experiences. Questions were piloted with members of the steering committee. Questions that were unclear in meaning were modified to address any issues identified in the piloting process.

Table 1. Focus group questions asked of volunteers to determine the barriers and enablers to volunteer engagement in the Moving Feast and the perceived benefits received from volunteering

The focus group sessions were conducted during November 2014 and February 2015. A digital audio recording of each focus group was transcribed word for word. The transcripts were the primary data sources. At the end of the session, ending questions were used (Krueger & Casey, Citation2009) in which participants were asked to provide written answers to questions on the key enablers and barriers to volunteering (Table ). These were used as secondary data to complement the focus group transcripts.

3.3. Data analysis

QSR NVivo10 software (QSR International Pty Ltd) was used as a data management tool for handling the transcripts. Descriptive thematic analysis (as described by Miles & Hubermann, Citation1994) was used to initially code and categorise the key themes relating benefits received from volunteering and the enablers and barriers to engaging in the Moving Feast.

To ensure credibility and confirmability of the findings and reduce the risk of subjective bias, researcher triangulation and peer debriefing was used during the analysis. Following the initial coding by the primary researcher, the other two researchers coded subsets of the data as a basis for triangulation (Morse, Citation2015). Analysis was compared and minor differences were resolved through discussion. In addition peer debriefing was undertaken to enhance the robustness of the analysis (Creswell & Miller, Citation2000).

Results are described and related to the three main areas investigated: benefits received, and barriers and enablers to volunteer engagement within a university-based community garden setting. Direct quotes are provided to better illustrate the themes by presenting insight into the participant perspective. To protect identity of participants, all quotations are de-identified with quotes being identified by participant number (Participant number indicated in Table ).

Table 2. The student volunteers of the Moving Feast who participated in the focus groups (n = 14)

All three researchers involved in this study have had experience volunteering in the Moving Feast in some capacity. One researcher (CA) has been involved as a student volunteer and undertaken a student leadership role. The other two researchers (JM & HW) have been involved as staff volunteers and as members of the steering committee. This close involvement and first-hand experience allowed the researchers to also use participant observation (Creswell, Citation2003) which have been drawn on in the discussion to provide an extra layer of depth and understanding to the findings presented.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

Seventeen volunteers from the 106 registered volunteers responded to the invitation to participate in the study and were scheduled in a focus group session. Of these, two withdrew prior to the sessions. Of the 15 participants who participated in the focus groups, 14 participants were students at the university and one was a staff member volunteer. Given that a single staff member participant would not necessarily reflect the opinion of other staff volunteers, the data from this staff participant was excluded from the analysis.

Of the remaining 14 participants included in this study, the majority of participants were female (n = 12/14, 86%) (Table ). This was reflective of the Moving Feast volunteer population which consisted mostly of female volunteers (n = 81/106, 76%). The participants were from a range of study areas at the university (Table ). More than half of the participants were students of the Health, Nursing & Sports Sciences study area, with 57% enrolled in the Nutrition and Dietetics discipline (57%). The high proportion of Nutrition and Dietetics students was likely due to the involvement of the Nutrition and Dietetics Department in the initial design, implementation and project management of the Moving Feast. Therefore, students enrolled in the programs from this Department were likely more aware of the Moving Feast. During the course of the focus groups, participants reported varying levels of engagement with the project. Some were more active than others either engaging regularly in volunteer activities or taking on Pod Leader roles for the volunteer teams, while others had not actively participated beyond registering. A total of five focus groups were held, with between two and five participants in each group. The focus group sessions lasted approximately 40–50 min.

4.2. Enablers to engagement

Participants experienced a range of factors that had supported their engagement in the Moving Feast (summarised in Table ). Regular and interactive communication was a key theme that emerged as an enabler to engagement, along with personal motivations, having the project embedded in their university curriculum and interpersonal relationships that supported engagement.

Table 3. Enablers to volunteer engagement in the Moving Feast, with indicative quotes to provide further insight

4.2.1. Regular communication

Regular and interactive communication was a key enabler discussed by most of the participants. Being regularly kept up to date and informed about the garden’s progress through email correspondence and social media was perceived as a way to keep connected to Moving Feast project even if they were not actively participating at the time. Interactive mediums such as photos and Facebook posts helped to maintain the volunteers’ interest and provided incentive and inspiration to become involved.

4.2.2. Personal motivations

Participants own motivations for being involved underpinned reasons for volunteering. The most common motivating factor was the desire to learn and increase knowledge, in particular around topics related to gardening, sustainability and healthy food. Altruistic motivations (acting on values) were identified by some participants as the most important enabler for their engagement. “… it fits into who I see myself as, my identity, I see myself participating in community activities like this… I felt the project aligned with my values.” (Participant 8, Female). Many participants described their values around supporting sustainable food systems or improving the nutrition and health of others. For one of the participants, the well-being of others particularly disadvantaged students was discussed looking into the future: “I’m looking forward to when it’s actually up and running and it’s established… (to) see some public health aspects. So the more disadvantaged students being able to access fresh fruit and vegetables…” (Participant 10, Female). Thirdly, some participants were also motivated to volunteer by their desire to obtain benefits that would boost their employability prospects and future careers, and several spoke about how being able to add their experience in the Moving Feast to their resume as a motivating factor.

4.2.3. Embedded in university curriculum

A few participants identified how being involved in the garden as part of their university curriculum was an enabling factor for their engagement through hearing more about the Moving Feast or through mandatory involvement via student placements or projects. One student discussed how the Moving Feast project was embedded within their course as a placement project, enabling their initial involvement as it was a requirement of their course. This student further reflected how this engagement through their course provided a sense of ownership over the project, and subsequently influenced their decision to continue to participate as a volunteer post placement: “The timing of my placement I got to be a part of it in the early stages so I was really in with the behind the scenes….I have a sense of ownership of the project…” (Participant 9, Female)

4.2.4. Relationships

Relationships and friendships with other Moving Feast members played a role in helping some engage as they were more inclined to participate because their friends were. In addition, participants commented how their friends involved with the Moving Feast provided “word of mouth” promotion of the garden which positively influenced their own engagement. For some participants, working relationships with key people in the project enhanced their engagement. For example, student–staff relationships with the Moving Feast project manager that developed during placement projects continued after placement finished and supported engagement. Establishing and maintaining working relationships was also perceived to have a positive impact on communication processes in particular around being kept informed. One participant explained “…because I have contacts that I established with people leading it, I think I feel like I’ve been more updated than a lot of other people because they’ve been more aware of me and keep me in the mailing list.” (Participant 9, Female).

4.3. Barriers to engagement

A number of barriers to engaging with the Moving Feast included: competing priorities and obligations; issues around modes of communication and lack of information; inconvenient/poor timing of the organised activities; and perceived lack of opportunities to be involved given the early stage of the gardens development (summarised in Table ).

Table 4. Barriers to volunteer engagement in the Moving Feast, with indicative quotes to provide further insight

4.3.1. Competing priorities and timing

For the participants, competing priorities and obligations was the most common barrier experienced. Participants found that their university study and classes, placement or work-related commitments were key factors in preventing or reducing their involvement in the garden. Participants also spoke of having limited available time during semester because of these obligations: “When it’s during semester and exams, all of that time is taken up with uni (university) work and I just can’t put anything anywhere else.” (Participant 10, Female). In addition, the timing of garden activities (such as working bees) also impacted on participants ability to engage as they often didn’t align with volunteers’ availabilities. Garden activities were only held on weekdays and tended to conflict with class timetables, were held in study week or conflicted with other commitments such as work, family or other volunteer events. “I had home and family commitments, but also studying… A lot of the days when you would have events I couldn’t come [because] I’m picking kids up from school or doing classes or something like that. So I found some of the times were really difficult to be a part of.” (Participant 14, Female)

4.3.2. Modes of communication and lack of information

While effective and regular communication was very helpful to volunteering, issues around modes of communication used and the various preference of volunteers were raised as a barrier. Some participants noted barriers around email communication and acknowledged that email communication often relies on the volunteer actively checking their inbox or that emails were sometimes not received. Others discussed a preference for an “in your face” reminder system such as text messaging or calendar reminders through outlook to assist them in remembering gardening sessions were on.

A lack of awareness and information about the project was raised and several participants felt that communication to volunteers was sometimes inadequate, all of which contributed to feelings of disengagement. One student participant summarised “…if there is no communication it doesn’t give you the impetus to want to stay in touch with the project.” (Participant 12, Female). For some participants, not knowing who the key contacts for the garden were or even knowing where the garden was located were barriers to engagement. Several participants discussed that there was a general lack of awareness and promotion of the garden in the wider university community. This lack of information and awareness of the garden was illustrated by the following participant’s experience:

“I [had] an experience with coming here the other day, like although I’ve been involved as a volunteer, I had no idea where the garden was. And I spent about an hour asking everyone on campus, no one had even heard of it.” (Participant 4, Female)

4.3.3. Early development stage of garden

Participants perceived there were limited opportunities to be involved as the garden was small and in the early stages of development, which acted as barriers to engagement. Some participants expressed that during the early stages of the garden there was planning and “behind the scenes” work being done which meant that “hands on” garden activities weren’t always available (Figure ). In contrast, when there were gardening opportunities available other participants perceived they lacked the skills required to participate, or alternatively that there was a lack of opportunities to use their particular skills.

Figure 2. Earthworks and garden construction underway in the early development stages of the Moving Feast, which was perceived by some volunteers as a difficult stage to be involved in

“I signed up for the marketing team and we haven’t really had any marketing things to do yet. So apart from the gardening and the planting it’s not really where my skills lie. There hasn’t been any need I think.” (Participant 10, Female)

4.4. Benefits

Participants described a number of perceived benefits as a result of their engagement in the Moving Feast. The main themes that emerged were relational benefits including connecting with others and experiencing a sense of belonging; learning and educational type benefits; and personal benefits such as pleasure and satisfaction (Table ).

Table 5. Perceived benefits received from volunteering in the Moving Feast, with indicative quotes to provide further insight

4.4.1. Connecting with others and a sense of belonging

Social benefits relating to connecting with others and building relationships as well as a sense of belonging emerged strongly across all five focus groups. Participants described meeting new people and building friendships and relationships as a primary benefit received. Existing and new friendships were strengthened through social interactions experience when working together on a shared activity (Figure ). Volunteering in the Moving Feast also contributed to a sense of belonging to the garden community as well as the wider university community for participants. A sense of belonging was achieved through feeling as though they were “giving back”, their participation providing a sense of ownership of the project and also connecting with others with common values. These benefits were received from participation in events such as working bees (Figures and ) and meetings, and also through communication channels such as email.

4.4.2. Gaining skills and educational-type benefits

Participants also commonly discussed receiving learning and educational-type benefits. These educational benefits primarily encompassed learning new hands on skills such as construction and gardening, and knowledge about gardening and various plants. These skills and knowledge were gained from involvement in the working bees and workshops (Figure ). Additional educational benefits included gaining insight and knowledge into how community gardens are run. Participants also developed interpersonal, communication and facilitation skills. For some participants, they saw value in their volunteering as a way to build skills, competencies and develop and demonstrate qualities that could benefit their future career and be added to their résumé.

4.4.3. Pleasure and satisfaction

Participants also discussed personal satisfaction, pleasure and relaxation as benefits received. Pleasure derived from participating included relieving stress and the act of being in the garden and doing physical activity. Participants also expressed how their pleasure and satisfaction was derived through “seeing something actually come out if it” (Participant 13, Female) for example tangible outcomes such as the construction of the garden beds and being able to harvest vegetables and herbs (Figure ).

5. Discussion

In this study, we explored the barriers and enablers to volunteer engagement and the perceived benefits student volunteers received from involvement in the Moving Feast. These findings provide insight into volunteer engagement in a newly established university-based garden context. The learning and education obtained through engagement with the garden was both an enabler and a perceived benefit of volunteering. Other key enablers included interactive communication, having the garden as part of their university course work and other personal motivations. Common barriers to volunteering included competing priorities and conflicting timing of sessions and activities. Social and learning/educational benefits emerged as the primary benefits received. These findings and their implications for volunteer engagement and sustainability of the garden are considered in the following discussion.

The study found that key barriers to volunteering included competing priorities with timetabled study and classes and reported limited available time during semester to participate. This is not necessarily unexpected given that lack of time related to study commitments has been previously identified as the main obstacle for engaging students in volunteer work (Blanchard, Rostant, & Finn, Citation1995). Similar barriers have been noted in other garden settings in Australia and the United States (Haynes & Trexler, Citation2003; Henryks, Citation2011; Kingsley et al., Citation2009). In our case, scheduling garden events and activities during “normal” working hours may have been based on a presumption that students would have spare time between classes during the day. From our results, it appears that in reality university students’ time during the day is not only consumed with classes, study and working on assignments but also with employment and family commitments, leaving little time to participate in extracurricular garden activities. Therefore, the timing of gardening sessions and activities may require careful consideration by leaders and organisers of university-based gardens including flexibility in dates and times, scheduling some activities outside of hours and developing strategies that allow volunteers to participate in their own time and autonomously.

Unique to this study was that the Moving Feast was in the early developmental stage at the time of data collection. Our study suggests that unique challenges exist in these early stages including the tension between needing volunteers to get the garden growing and having a garden to attract volunteers to. For example, there was a range of planning and “behind the scenes” work being done, therefore “hands on” gardening related activities and opportunities were not always readily available. Some participants also perceived they lacked the skills to perform the tasks that were available. While these issues can be perceived as a barrier, being aware of the potential challenges to engagement during the establishment phase presents an opportunity for garden organisations and leaders to invest in resources, training and support in order to make effective use of volunteer resources and maximise volunteer engagement (Flick, Bittman, & Doyle, Citation2002; Noble & Rogers, Citation1998). Regular communication is also needed to initially engage and keep stakeholders consistently involved (McKinne & Halfacre, Citation2008), and this was demonstrated to be especially pertinent during the initial development phases of the Moving Feast where less opportunities for hands on work were available. Complicating this enabler is the diverse range of communication mediums as well as differences in individual preferences and communication needs as highlighted by participants in this study.

Embedding the garden into the university curriculum is a potential solution to enable university students to actively engage in and benefit from the garden while concurrently addressing barriers relating to competing priorities and being time poor. While this solution has potential, it has been previously argued that this approach must be optional rather than compulsory in order to sustain a better long-term impact (Haski-Leventhal, Meijs, & Hustinx, Citation2009; Stukas, Snyder, & Clary, Citation1999). Embedding mandatory service within the university context can affect perceptions of external control and therefore it is less likely that a positive relationship between prior volunteer experience and future intentions to volunteer will occur (Haski-Leventhal et al., Citation2010). However, this was not the case of the present study, as we found that students who had engaged with the garden as part of their course work subsequently continued to engage as a volunteer beyond their course requirements. In addition, working relationships developed with key people in the garden appear to also have a positive influence on on-going engagement with the garden. This has certainly been the experience of one of the researchers (CA), whose involvement in the Moving Feast enhanced their engagement with the garden through the research being part of their curriculum and the relationships they formed with the steering committee and lead staff.

The notion of embedding university gardens within the university curriculum is an area of growing interest. Many educators are re-discovering the value of gardens as spaces for learning in educational institutions, including universities (Bell & Dyment, Citation2008; Gaylie, Citation2009; Walter, Citation2013; Williams & Brown, Citation2012). Educators and researchers alike are increasingly advocating for embedment of garden-based-pedagogy into the curriculum (Danks, Citation2010; Dyment, Citation2005; Stone, Citation2009). In the university setting, using garden-based pedagogy has been shown to develop students’ environmental knowledge and attitudes, develop their knowledge of food production and systems, and foster their connection to the natural world (Gaylie, Citation2009; Williams & Brown, Citation2012). Embedding the community garden within the university curriculum presents opportunities for applied education and research, service learning, unique projects and project management as well as the integration of separate disciplines (Ahonen et al., Citation2012; Albrecht, Citation2010; Scoggins, Citation2010; Waliczek & Powers, Citation2012) such as environment and sustainability, engineering, occupational therapy and nutrition disciplines.

Similar to previous qualitative studies on community garden volunteers (Brown-Fraser et al., Citation2015; Hale et al., Citation2011; Kingsley et al., Citation2009) the learning and educational benefits, such as developing gardening skills, emerged as an important element of volunteer engagement. Perhaps a point of difference between these studies and our findings is the emphasis on educational benefits that participants perceived would benefit their future career. Existing research on university student volunteers in general has shown that students are increasingly motivated to volunteer to learn and gain marketable skills (Adams & Picone, Citation2009) and to gain credit points towards their course work and work experience or references for their future career (Esmond, Citation2000). Haski-Leventhal et al. (Citation2010) suggest that students may be more willing to engage in volunteering if it is an opportunity to gain experience for career-path development. Thus, university-based gardens not only increase environmental knowledge and gardening skills, but also provide a unique learning space that can be harnessed for professional competency through service based learning (Edwards, Mooney, & Heald, Citation2001; Gupta et al., Citation2013; Haski-Leventhal et al., Citation2010; Nettle, Citation2009). Taking this approach may also have positive implications for the on-going sustainability of the garden. For example, utilising interns or placements may ensure commitment stability within key positions and there are opportunities for university gardens to embed aspects of garden management into academic curriculum (Gupta et al., Citation2013; Scoggins, Citation2010). Given the challenges in maintaining student engagement in these gardens and the high failure rate of community gardens in general (Drake & Lawson, Citation2015), this is an area that warrants further attention.

The benefits of university community gardens extend beyond learning-based activities, and include social benefits – an important element of the volunteer experience for those in our study. Our results indicate that social benefits such as meeting people and experiencing a sense of belonging are important for creating a positive experience and enhancing volunteer engagement, which are similar to findings described across numerous community garden settings including urban-based, community-based and school gardens (Kingsley et al., Citation2009; Teig et al., Citation2009; Wakefield et al., Citation2007). It has been well recognised that community gardens are more often about building community than gardening (Glover, Citation2003) and our study illustrates that a university garden is no different. Engagement with the garden provides students and staff with the opportunity to connect and enjoy activities outside of academic life (Scoggins, Citation2010).

Our findings also bring to light implications for recruitment, on-going engagement and retention. It is well recognised that benefits received by volunteering promote volunteer satisfaction and reinforce involvement, thereby contributing to on-going motivations and volunteer retention (Dwiggins-Beeler et al., Citation2011; Omoto & Snyder, Citation1995; Wilson & Musick, Citation1999). This has also been illustrated through the experiences of volunteers in a school kitchen garden in Australia (Henryks, Citation2011). Henryks (Citation2011) found that the benefits received from volunteering kept volunteers engaged and provided them with continued motivation to volunteer. Our findings, in the context of the existing literature, have implications for volunteer engagement and retention. It highlights the role of management to plan for and provide opportunities in which the social and educational benefits can be experienced, which may in turn increase satisfaction, engagement and ultimately retain volunteers. Such opportunities or strategies may include social gatherings and formalised workshops.

Individual personal motivations for volunteering are also associated with volunteer recruitment and retention (Flick et al., Citation2002). Volunteers will only give their time if they are motivated to do so (McCurley & Lynch, Citation1998), and our participants discussed their personal motivations as being a primary enabler to engaging. Motivation is a key determinant of behaviour and directly affects the activity levels of volunteers (Flick et al., Citation2002). Our participants were primarily motivated by the desire to learn more about gardening and healthy food along with altruistic motivations such as acting on values around sustainable food systems. Developing strategies to further elicit and fulfil these motivations should be a key priority (Lucas & Williams, Citation2000), as motive fulfilment is well recognised as a crucial component of volunteer retention (Clary & Snyder, Citation1999; Flick et al., Citation2002).

There are limitations of this study to be noted. The sample for this study was made up of student volunteers, hence providing insight into the student volunteer experience only. Future studies may investigate staff experience more specifically particularly given the differing roles, responsibilities and context. Further, it was not within in the scope of this study to explore gender differences and the impact on volunteer engagement. It is unclear whether the size of the focus groups impacted on the data collected. The literature is mixed with respect to opinions on ideal focus group size, although according to Krueger and Casey (Citation2009) the ideal size for most non-commercial topics is 5–10 people, with the use of “mini focus groups” containing as few as 3 people also being endorsed (Krueger & Casey, Citation2009; Morgan, Citation1997). Even though the focus groups in the current study contained smaller numbers of participants, we believe that a diversity of views was obtained and data-rich information was collected. Finally, while the experiences described in this study are from a single university, the findings and implications are likely to be relevant to other university community gardens and newly established community gardens.

6. Conclusion

In this article, we have explored the barriers, benefits and enablers to volunteer engagement experienced by student volunteers in a university-based community garden. University-based community gardens are a specific context characterised by a transient volunteer workforce due to high turnover of the student population from graduation and semester breaks. Barriers to volunteering, the most common being competing obligations and priorities particularly around fluctuating study and work commitments, present challenges for managing and retaining student volunteers in these gardens. Further, this study explored volunteer engagement in the early phase of garden development, and additional barriers to volunteering were related to misconceptions that there were limited opportunities to be involved. There is little literature on this at present; however, our findings suggest there is a need to find ways to support involvement and manage volunteer expectations during these planning and establishment periods. Embedding garden activities into university curriculum may create a unique opportunity for both authentic learning opportunities for students as well as providing a needed garden workforce. Ensuring effective interactive communication along with providing opportunities for social and educational benefits and personal motivations to be realised may also prove to be an effective strategy for supporting engagement of student volunteers in university-based community gardens. Building on these enablers and benefits may increase student exposure and therefore volunteer engagement with the community garden, and in turn support the sustainability and longevity of the garden. While this article is based on the volunteer experience of a community garden within a single university, the findings and their implications may be transferable to other universities and could be used to inform others intending to commence a community garden project within university campuses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Judith Maher

Courtney Anderson is a technical officer with Parks, Sports & Natural Areas at the Bundaberg Regional Council and is passionate about sustainability, creating supportive built environments and empowering people to improve their health and well-being. This research was undertaken as part of her Bachelor of Nutrition & Dietetics degree (Honours) at the University of the Sunshine Coast, and the findings have implications for organisations and universities commencing community garden projects on their campuses. Judith Maher and Hattie Wright are faculty members in Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of the Sunshine Coast. This study links to the Discipline’s research focus on the characteristics of the food environment and determinants of food quality, eating behaviours and dietary intake in individuals and populations.

References

- Adams, N., & Picone, A. (2009). Generation Y volunteer: An exploration into engaging young people in HACC funded volunteer involving organisations [online]. Tasmania: Volunteering Tasmania Inc. Retrieved September 29, 2015, from http://www.volunteeringtas.org.au/sites/default/files/documents/Generation%20Y%20Volunteering%20Report.pdf

- Ahonen, K., Lee, C., & Daker, E. (2012). Reaping the harvest nursing student service involvement with a campus gardening project. Nurses Educator, 37, 86–88. doi:10.1097/NNE.0b013e3182461b74

- Albrecht, M. L. (2010). The scholarship of a university garden director. Hort Technology, 20, 519–521.

- Armstrong, D. (2000). A survey of community gardens in upstate New York: Implications for health promotion and community development. Health and Place, 6(4), 319–327.

- Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Government: Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate. (2012). A study of the demand for community gardens and their benefits for the ACT community [online]. Canberra: ACT Government. Retrieved February 6, 2017 from, http://www.actpla.act.gov.au/tools_resources/research_based_planning_for_a_better_city/demand_for_community_gardens_and_their_benefits

- Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network (ACFCGN). (2017). Directory, Data & Mapping. Retrieved June 23, from http://directory.communitygarden.org.au/search/site

- Batson, C. (1991). The altruism question: Towards a social-psychological answer. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

- Bell, A. C., & Dyment, J. E. (2008). Grounds for health: The intersection of green school grounds and health-promoting schools. Environmental Education Research, 14(1), 77–90. doi:10.1080/13504620701843426

- Blanchard, A., Rostant, J., & Finn, L. (1995). Involving Curtin in a volunteer community service program: A report on a quality initiatives project. Perth: School of Social Work Curtin, University of Technology.

- Brown-Fraser, S., Forrester, I., Rowel, R., Richardson, A., & Spence, A. (2015). Development of a community organic vegetable garden in Baltimore, Maryland: A student service-learning approach to community engagement. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 10(3), 202–229. doi:10.1080/19320248.2014.962778

- Clary, E., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(5), 156–159. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00037

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantiative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitiative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 1–130. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- Danks, S. (2010). Asphalt to ecosystems: Design ideas for schoolyard transformation. Oakland, CA: New Village Press.

- Drake, L., & Lawson, L. (2015). Results of a US and Canada community garden survey: Shared challenges in garden management amid diverse geographical and organizational contexts. Agriculture and Human Values, 32, 241–254. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9558-7

- Duram, L., & Williams, L. (2013). Growing a student organic garden within the context of university sustainability initiatives. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 16(1), 3–15. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-03-2013-0026

- Dwiggins-Beeler, R., Spitzberg, B., & Roesch, S. (2011). Vectors of volunteerism: Correlates of volunteer retention, recruitment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 2(3), 22–43. doi:10.1002/jpoc.v2.3

- Dyment, J. (2005). Gaining ground: The power and potential of school ground greening in the Toronto district school board. Toronto: Evergreen.

- Edwards, B., Mooney, L., & Heald, C. (2001). Who is being served? The impact of student volunteering on local community organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 30, 444–461. doi:10.1177/0899764001303003

- Esmond, J. (2000). The untapped potential of Australian university students. Australian Journal on Volunteering, 5(2), 3–9.

- Firth, C., Maye, D., & Pearson, D. (2011). Developing “community” in community gardens. Local Environment, 16(6), 555–568. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.586025

- Flick, M., Bittman, M., & Doyle, J. (2002). The Community’s Most Valuable [Hidden] Asset - Volunteering in Australia [Online]. Social Policy Research Centre, University of NSW. Retrieved September 29, 2015, from https://www.sprc.unsw.edu.au/media/SPRCFile/Report2_02_Volunteering_in_Australia.pdf

- Gaskin, K. (1998). Vanishing volunteers: Are young people losing interest in volunteering? Voluntary Action, 1(1), 33–43.

- Gaylie, V. (2009). The learning garden: Ecology, teaching, and transformation. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Glover, T. D. (2003). The story of the Queen Anne Memorial Garden: Resisting a dominant cultural narrative. Journal of Leisure Research, 35(2), 190–212. doi:10.1080/00222216.2003.11949990

- Graham, H., Lane Beall, D., Lussier, M., McLaughlin, P., & Sherizidenber-Cherr, P. (2005). Use of school gardens in academic instruction. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 37, 147–151.

- Gupta, P., McEniery, D., & Creyton, M. (2013). Innovative student Engagement [online]. Queensland: Volunteering Queensland. Retrieved June 23, 2017, from https://volunteeringqld.org.au/docs/Publication_Innovative_Student_Engagement.pdf

- Hale, J., Knapp, C., Bardwell, L., Buchenau, M., Marshall, J., Sancar, F., & Litt, J. S. (2011). Connecting food environments and health through the relational nature of aesthetics: Gaining insight through the community gardening experience. Social Science & Medicine, 72(11), 1853–1863. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.044

- Haski-Leventhal, D., Meijs, L.C.P.M, & Hustinx, L. (2009). The third-party model: Enhancing volunteering through governments, corporations and educational institutes. Journal of Social Policy, 39(1), 139–158. doi:10.1017/S0047279409990377

- Hatton, M. (2015). Community gardens: Creating opportunities and education [online]. International Specialised Skills Institute Inc. Retrieved December 12, 2016, from http://www.issinstitute.org.au/wp-content/media/2015/06/Report-Hatton-Final-LowRes.pdf

- Haynes, C., & Trexler, C. J. (2003). The perceptions and needs of volunteers at a university-affiliated public garden. Horticulture Technology, 13(3), 552–556.

- Henryks, J. (2011). Changing the menu: Rediscovering ingredients for a successful volunteer experience in school kitchen gardens. Local Environment, 16(6), 569–583. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.577058

- Holland, L. (2004). Diversity and connections in community gardens: A contribution to local sustainability. Local Environment, 9(3), 285–305. doi:10.1080/1354983042000219388

- Kingsley, J., & Townsend, M. (2006). ‘Dig In’ to social capital: Community gardens as mechanisms for growing urban social connectedness. Urban Policy and Research, 24, 525–537. doi:10.1080/08111140601035200

- Kingsley, J. Y., Townsend, M., & Henderson-Wilson, C. (2009). Cultivating health and wellbeing: Members’ perceptions of the health benefits of a Port Melbourne community garden. Leisure Studies, 28(2), 207–219. doi:10.1080/02614360902769894

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lucas, T., & Williams, N. (2000). Motivation as a function of volunteer retention. Australian Journal on Volunteering, 5(1), 13–21.

- Manthorpe, J. (2001). ‘It was the best of times and the worst of times’: On being the organizer of student volunteers. Voluntary Action, 4(1), 83–96.

- McCurley, S., & Lynch, R. (1998). Essential volunteer management. London: Directory of Social Change.

- McKinne, K. L., & Halfacre, A. C. (2008). Growing” a campus native species garden: Sustaining volunteer-driven sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(2), 147–156. doi:10.1108/14676370810856297

- Miles, M., & Hubermann, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Miller, L. E., Powell, G. N., & Seltzer, J. (1990). Determinants of turnover among volunteers. Human Relations, 43(9), 901–917.

- Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analyis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. doi:10.1177/1049732315588501

- Nettle, C. (2009). Growing community: Starting and nurturing community gardens. Adelaide: Health SA, Government of South Australia and Community and Neighbourhoods Houses and Centres Association Inc.

- Noble, J., & Rogers, L. (1998). Volunteer management: An essential guide. Adelaide: Volunteering S.A. Inc.

- Northrop, M. D., Wingo, B. C., & Ard, J. D. (2013). The perceptions of community gardeners at Jones Valley Urban farm and the implications for dietary interventions. Qualitative Report, 18, 1–11.

- Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671–686.

- Pearson, D. H., & Firth, C. (2012). Diversity in community gardens: Evidence from one region in the United Kingdom. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture, 28, 147–155. doi:10.1080/01448765.2012.706400

- Pudup, M. B. (2008). It takes a garden: Cultivating citizen-subjects in organized garden projects. Geoforum, 39, 1228–1240. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.06.012

- Scoggins, H. (2010). University garden stakeholders: Student, industry, and community connections. Hort Technology, 20, 528–529.

- Shallue, E. (2013). Community gardens manual [online]. Australia: Helen Macpherson Smith Trust. Retrieved June 23, 2017, from http://www.sgaonline.org.au/pdfs/factsheets/HMST%20manual%20dda.pdf

- Stone, M. (2009). Smart by nature: Schooling for sustainability. Healdsburg, CA: Watershed Media.

- Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M., & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of “mandatory volunteerism” on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59–64. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00107

- Teig, E., Amulya, J., Bardwell, L., Buchenau, M., Marshall, J. A., & Litt, J. S. (2009). Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: Strengthening neighborhoods and health through community gardens. Health and Place, 15(4), 1115–1122. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.003

- Thompson, A., & Anderson, S. (2012). The University of the Sunshine Coast community garden feasibility study and stakeholder analysis ( Unpublished report). Sippy Downs, University of the Sunshine Coast.

- Townsend, M., Gibbs, L., Macfarlane, S., Block, K., Staiger, P., Gold, L., … Long, C. (2014). Volunteering in a school kitchen garden program: Cooking up confidence, capabilities, and connections! Voluntas, 25(1), 225–247. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9334-5

- Turner, B. (2011). Embodied connections: Sustainability, food systems and community gardens. Local Environment, 16(6), 509–522. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.569537

- Twiss, J., Dickinson, J., Duma, S., Kleinman, T., Paulsen, H., & Rilveria, L. (2003). Community gardens: Lessons learned from California healthy cities and communities. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1435–1438.

- Wakefield, S., Yeudall, F., Taron, C., Reynolds, J., & Skinner, A. (2007). Growing urban health: Community gardening in South-East Toronto. Health Promotion International, 22(2), 92–101. doi:10.1093/heapro/dam001

- Waliczek, T. M., & Powers, M. (2012). The benefits of integrating service teaching and learning techniques into an undergraduate curriculum. Hort Technology, 20, 934–942.

- Walter, P. (2013). Theorising community gardens as pedagogical sites in the food movement. Environmental Education Research, 19(4), 521–539. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.709824

- Wanderman, A., & Alderman, J. (1993). Incentives costs and barriers for volunteers: a staff perspective on volunteers in one state. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 8(1), 67-76.

- Williams, D. R., & Brown., J. D. (2012). Learning gardens and sustainability education: Bringing life to schools and schools to life. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wilson, J., & Musick, M. A. (1999). Attachment to volunteering. Sociological Forum, 14(2), 243–272. doi:10.1023/A:1021466712273