Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this systematic review was to determine what impact governance principles and guidelines have had on sport organisations’ governance practices and performance.

Methods: Following the PRISMA, PIECES and Warwick protocols, we conducted a search of academic, grey literature and theses in sport and broader social sciences and humanities databases. We excluded studies that only proposed governance principles and did not actually measure their use by sport organisations, as well as those studies which did not consider the governance principles in relation to organisational performance.

Results: From the initial 2,155 studies reviewed, 19 met the inclusion criteria. A wide range of governance principles or guidelines have been considered by the relatively small number of studies included in the analysis. We did find a variety of researchers from mainly developed countries examining the issue, often using case studies as a means to explore the topic. Although the link between board structure and organisational performance has been empirically found, the link between other governance principles and organisational performance remains lacking.

Conclusions: Despite an increased interest in good governance principles and guidelines in sport, there is a clear need for both the international sport community and researchers to develop an agreed set of governance principles and language relevant for international, national, provincial/state and local level sport governance organisations. The multidimensionality of the concepts of governance and organisational performance, as well as their interrelationship and the potential positive and negative impacts of implementing governance principles render this need all the more critical.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Given current corruption scandals and calls for better governance of sport organisations, it is important to see whether the increased number of suggested governance principles have impacted on sport organisations’ practices and performance. A bibliographic search revealed a lack of a systematic review on sport governance, let alone the impact of either recommended or mandated governance principles on the performance of sport organisations. This systematic review’s findings show a range of potential governance principles can be used, that no agreed-upon set of principles exists amongst national sport agencies or researchers and the organisational performance impact of governance principles remains poorly understood. We cannot yet answer the question: does implementing a range of good governance principles positively affect organisational performance? Moreover, we found researchers presenting cautions about the potential negative repercussions of requiring the implementation of governance principles by volunteer members, thereby pushing non-profit organisations to act like for-profit organisations.

In recent years, a number of international and national sport governing bodies have been beset with corruption scandals and challenges to their legitimacy (Hoye, Citation2017). Numerous instances of individual directors failing to behave appropriately, the continued use of antiquated or inequitable governance structures, failures to instil adequate checks and balances over decisions by boards, and cases of outright failure to govern have led to calls for better governance of sport organisations from both governments and independent agencies (cf. Australian Sports Commission, Citation2015; Play the Game, Citation2015). One response of government, sport organisations, and independent agencies has been the development of an increasing number of suggested governance principles and guidelines designed to counter failures in governance, such as democratic structures/democracy, accountability, transparency, professionalization, control/supervisory mechanisms, fairness, solidarity/social responsibility, equality, elected presidents, board skills (instead of representation) and term limits, separation of board chair and CEO roles, codes of ethics and conflicts of interest, athlete involvement/representation, stakeholder participation/representation, anti-bribery/corruption codes, equity, respect, autonomy/independence, evaluation, effectiveness, efficiency, planning standards, structure standards, and access and timely disclosure of information (Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2013).

The increase in the number of governance principles and guidelines developed in recent years was highlighted by Chappelet (Citation2018, p. 724) who stated “since the beginning of the twenty-first century, governmental and intergovernmental bodies, national and international sport governing bodies and academics have put forward numerous lists—more than 30 in total—of governance principles for sport organisations”. These include efforts by independent agencies, such as Play the Game/Sport Observer for national and international sport federations (IFs); elements of the Olympic Movement, such as the European Union office of the European Olympic Committee and the International Olympic Committee itself; national peak bodies for sport, such as Sport & Recreation Alliance UK; government agencies, such as the Australian Sports Commission, UK Sport, and Sport New Zealand; as well as independent academic groups, such as Birkbeck University in the UK .

Despite the development of these guidelines over the last 15 years and, in some cases, the mandated adoption of them for sport governing bodies by national sport funding agencies or international (sport) organisations, there remains scant evidence of their impactFootnote1 on sport organisations’ governance practices and performance. It seems that there are a range of (implicit and untested) assumptions made by policymakers and funding agencies whereby adherence to governance principles is related to, or results, in improved governance performance of sport organisations, with performance referring to a potentially broad range of governance-related performance indicators (based on one or more of the governance principles noted earlier) and/or performance management measures centrally imposed by these actors (cf. Green & Houlihan, Citation2006; Grix, Citation2009). The subject of sport organisation performance in relation to governance practices has been explored by authors, such as Hoye (Citation2004), Hoye and Cuskelly (Citation2003, Citation2004) and Hoye and Doherty (Citation2011), who focused on a range of drivers of the performance of non-profit sport boards including structure, power, board composition, and leadership interactions, but not specifically the adoption of a set of governance principles on the overall sport organisation’s performance.

The authors are unaware of any other published systematic review on sport governance, let alone the impact of either recommended or mandated governance principles and guidelines on the governance performance of sport organisations. Having sport organisations adopt various governance principles without understanding the potential impacts can be ineffective and inefficient. The purpose of this systematic review was therefore to determine what impact governance principles and guidelines have had on sport organisations’ governance practices and performance. Understanding the relationship between governance principles and performance can then assist policymakers and funding agencies in their evidence-based decision making.

1. Methods

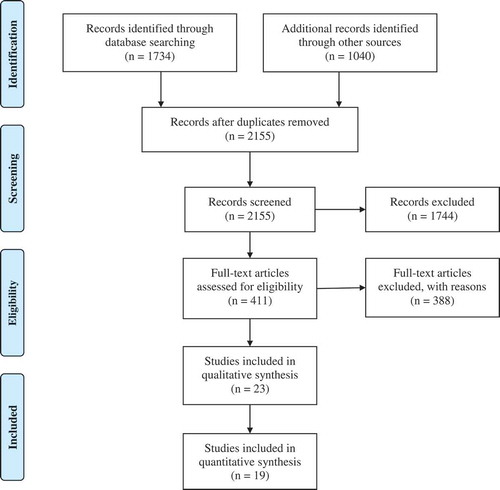

As no review protocol specific to sport management and/or governance existed at the time of the study, this systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, Citation2009), PIECES (Foster & Jewell, Citation2017) and University of Warwick (Citationn.d.) protocols. Figure provides the PRISMA flow chart details. After the Warwick protocol and search strategy were independently peer-reviewed using the PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies) guidelines by a university librarian expert in systematic reviews, the initial research question was broadened from national and international sport organisations only to all sport organisations (e.g., including sport event organisations). Next, the first author conducted the initial search to download all references from the search results, importing them into Endnote, which allowed for duplicates to be identified and removed. The resulting reference list of 2,155 records was uploaded into the Covidence online systematic review platform. Subsequent steps were conducted independently by both authors; after completing each step, they reconvened to discuss and resolve any conflicts before moving onto the next step. Methodological details are found below.

1.1. Search strategy

After an initial test of search term criteria in SPORTDiscus to ensure the right types of publications were found, the search strategy and protocol were independently peer-reviewed and discussed between the peer reviewer and the review’s two authors. To ensure the broadest capture of publications possible, the following search terms were decided upon, where TI = title, AB = abstract, KW = keyword, and SU = subject:

(TI Governance OR AB Governance OR KW Governance OR SU Governance)

AND

(TI (“sport* organi*” OR “governing bod*” OR federation* OR association* OR “sport* event*”) OR AB (“sport* organi*” OR “governing bod*” OR federation* OR association* OR “sport* event*”) OR KW (“sport* organi*” OR “governing bod*” OR federation* OR association* OR “sport* event*”) OR SU (“sport* organi*” OR “governing bod*” OR federation* OR association* OR “sport* event*”))

On 22 January 2018, the first author conducted a search of academic literature, grey literature, and theses in sport and broader social sciences and humanities databases, specifically: SPORTDiscus, Proquest (all included, such as ABI Inform Complete and Dissertations & Theses), SCOPUS, Google, Open Grey, SIRC (Sport Information Resource Centre), Theses Canada, and Open Access Theses and Dissertations. She also targeted projects and organisations with documents of potential interest the authors already knew about: Play the Game/Sport Observer for national and IFs, SIGGS, the International Olympic Committee, the European Union’s Expert Group on Good Governance in Sport, BIBGIS, The Principles of Good Governance for Sport and Recreation (Sport & Recreation Alliance UK), Mandatory Governance Principles from the Australian Sports Commission, Good Governance in Sport (from Birkbeck), and the Implementing Good Governance Principles white paper from TSE consulting. Finally, the second author searched publisher sites for sport governance-related books from Sage, Routledge, Elsevier, Human Kinetics, Sagamore Publishing, Palgrave Macmillan, Holcomb Hathaway, Oxford University Press, and Meyer and Meyer. All records (the references) were imported into Endnote, and duplicates removed.

This list of 2,155 records was uploaded into Covidence and each author independently screened the records, first with the title/abstract only and then with the full-text (see Figure for outcomes of the screening). Table provides the pre-selected inclusion and exclusion criteria used throughout the screening process that were designed to capture as many possible outlets as possible while excluding works that provided no empirical evidence, were not related to sport organisations, or did not explore the possible link between governance principles and organisational performance.

Table 1. Pre-selected inclusion and exclusion criteria for the systematic review

1.2 Quality assessment

In order to assess the quality of the records for final inclusion, analysis and synthesis, the authors used an adapted version of the American Psychology Association’s (Citationn.d.) guidelines for reviewing the 23 remaining manuscripts. This resulted in four records being excluded due to poor research/methods quality.

1.3. Data extraction and analysis

The following information from the final 19 records was extracted and put into an Excel table: publication type, publication source, country(ies) of study, research question, governance principles or guidelines considered, methods (research design and data collection sources), sample/unit of analysis, findings, and limitations. Together, the authors extracted the information from the first record to ensure agreement on process and information to extract. Next, each author extracted the information for half the records, and verified the information extracted by the other author for the other half of the records.

The analysis focussed on identifying similarities and differences between the 19 records in relation to the governance principles or guidelines considered, the theoretical framework adopted by the study, their research questions, and the findings (governance principles and their impact on performance). A secondary focus of the analysis identified patterns amongst the 19 records in terms of publication type and sources, countries where the studies had been conducted, the methods, unit of analysis, and study limitations.

2. Results

As shown in Table , the 19 records included 14 journal articles, 3 theses, and 2 reports published between 2004 and 2018, with 10 of those published in the last 5 years. The peer reviewed journal articles appeared in nine different journals, including four in the International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics and two each in the Journal of Sport Management and the European Sport Management Quarterly. Fifteen records focussed on single countries, one included two countries, and three were focussed on Europe or international regions, with the United Kingdom being the subject of six records, Australia two, New Zealand two, and Norway two, with single studies being conducted in Canada, France, Scotland, and South Africa.

Table 2. Summary of extracted data from studies included in quantitative synthesis

The predominant research design was a case study approach (one used an action research approach) using traditional organisational studies data collection strategies (interviews, document analyses, surveys, and observations). The focus of 13 studies was on national sport organisations (NSOs), two studies focussed on professional sport and the associated governance structures (clubs, leagues, NSO, player unions), two studies focussed on organizing committees of major sports events (and their stakeholders), one study focussed on IFs, and one focussed specifically on professional football (soccer) clubs.

The very wide range of governance principles or guidelines considered by this relatively small number of studies is also highlighted in Table . These include principles related to (1) membership, such as board diversity and composition, the degree of independence of the board, the range of stakeholder presence in the governance system of a sport organisation, board size, and ownership structures; (2) the nature and extent of inter-organisational linkages; (3) regulatory structures impacting the governance of sport organisations; (4) decision making issues, such as accountability, transparency, procedural fairness, democratic processes and decision making protocols; (5) shared leadership; and (6) the strategic focus of the board.

The research questions investigated by these studies focussed on five areas: (1) the impact of gender quotas for board composition on governance outcomes, (2) the impact of external forces, including government policy on governance practices, (3) seeking to explain governance performance, (4) the role and structure of boards, and (5) the extent of the adoption of specific governance principles by sport organisations. Somewhat surprisingly, none of the studies explicitly sought to explore the extent to which the adoption of specific governance principles had impacted actual governance outcomes or performance of sport organisations.

While two of the studies did not appear to utilise a theoretical framework, a wide range of theoretical frameworks were utilised by the other 17 studies with the predominant ones being corporate governance (used by five studies), new managerialism or modernisation (three studies), democratic governance (two studies), organisational management and gender dynamics (two studies), organisational theory (two studies), political science (two studies), and three other theories being used once: Agency theory, stewardship theory, and managerial hegemony.

The range of the findings of the studies summarised in Table reflects the diversity of research questions, theoretical frameworks and, importantly, the conceptualisation of governance principles and guidelines adopted by this collection of studies. The findings illustrate the relative lack of adherence (or resistance) to good governance principles in some cases and the potential these principles have to support good governance performance. They also illustrate that most studies have focussed on single or small numbers of principles and that no studies have examined the impact of the adoption of a comprehensive suite of governance principles or mandated guidelines on the governance outcomes or performance of a sport organisation. Overall, studies highlight that pressures outside sport may be the best way to improve sport organisations’ governance practices and performance (cf. Geeraert, Alm, & Groll, Citation2014) and that appropriate board structure positively impacts organisational performance. But, cautions are raised in terms of pushing volunteer members to be too professional, too much like for-profit organisations, in the quest for good governance, which impacts volunteers’ capacity to devote time and effort to non-profit sport organisations and puts greater emphasis on commercial values (cf. Ferkins, Shilbury, & McDonald, Citation2009; Tacon & Walters, Citation2016; Taylor & O’Sullivan, Citation2009; Walters & Tacon, Citation2018).

3. Discussion

This review highlights that governance principles and guidelines in sport are of increasing interest amongst governments, practitioners and researchers from many different (mainly developed) countries and in a range of sport contexts. The studies are also largely independent studies, not funded by federal sport agencies, and have explored a wide range of research questions.

The review highlights the multidimensionality of the concepts of performance (Bayle & Robinson, Citation2007) and governance (e.g., Burger, Citation2004; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Parent, Citation2016), as well as their interrelationship (Parent, Citation2016). Moreover, board composition (Bradbury & O’Boyle, Citation2015), independence (Bradbury & O’Boyle, Citation2015; Dimitropoulos, Citation2014), ownership dispersion (Dimitropoulos, Citation2014), and shared board-CEO leadership and collaboration (Ferkins et al., Citation2009) positively affect an organisation’s (financial) performance. The review results also suggest that the board structure-organisational performance link seems established, while the empirical link between other good governance principles and improved organisational performance more broadly remains elusive.

As well, caution is also raised by researchers (e.g., Ferkins et al., Citation2009; Grix, Citation2009; Walters & Tacon, Citation2018) of the increasing demands placed on sport managers, especially volunteer board members, moving them from volunteers to unpaid professionals needing to act like for-profit managers, and having good governance become a superficial, box-ticking exercise to obtain funding or to illustrate an organisation’s compliance to accepted norms.

Thus, what is striking is that while the findings of each of these studies independently have merit, collectively they illustrate the lack of robust, empirical, independent evidence that has been collected to date that helps to elucidate the core question of which governance principles should sport organisations adopt and implement to optimize their overall governance and performance or how governance principles may need to differ between legal jurisdictions or cultural contexts. This is not surprising given the lack of agreement amongst national sport agencies and independent sport governance watchdogs of what constitutes a set of core governance principles for sport and the range of somewhat disparate sport governance guidelines that have been developed by leading national sport agencies, such as the Australian Sports Commission and UK Sport.

Compounding the problem is the lack of a consistent theoretical approach or conceptualisation of governance principles being adopted by researchers over the last 15 years. This has manifested in a succession of somewhat unrelated studies being published over this time by a wide range of authors with no sense that there is any sort of research program or thematic approach to understanding the issue of good sport governance principles or guidelines amongst the international sport management research community. Subsequently, each independent researcher or research team has conceptualised good governance principles using different criteria and applied different theoretical approaches to understanding the phenomena. There has been some consistency amongst researchers who have largely used traditional organisational research methods and data collection approaches in their studies. Given the focus of these studies has been on identifying current governance practices and behaviours of organisations and individual directors, the use of interviews, document analyses, surveys, and observations in these studies is understandable.

The more recent studies published by Walters and Tacon (Citation2018) and Tacon and Walters (Citation2016) highlight that there is a growing focus on the influence of governance principles and guidelines in sport, especially the role of national sport agencies in influencing their adoption by NSOs, as well as the influence these have in the behaviours of individual directors. The other set of studies on the impact of gender quotas on boards (Adriaanse & Schofield, Citation2014; Sisjord, Fasting, & Sand, Citation2017), a very topical issue coinciding with the current groundswell of interest in the #metoo movement, the growth of women’s sport and the importance of ensuring women are serving in leadership roles in sport, also highlights the early signs that some forms of thematic approach to understanding governance principles and guidelines in sport are starting to emerge from the research community.

4. Conclusions

This systematic review has demonstrated that, despite an increase in interest in research associated with good governance principles and guidelines in sport, there is a clear need for both the international sport community and researchers to develop an agreed set of governance principles and language relevant for international, national, provincial/state and local level sport governance organisations. This may be unrealistic given the multitude of stakeholders involved, such as the International Olympic Committee, IFs and numerous national (sport) agencies, as well as the different legal and cultural contexts between national sport systems; but, this lack of coherence will limit the ability of both sport organisations to improve their governance and researchers to understand which principles and guidelines are central to improved governance performance in sport organisations.

The primary limitation of the published research to date has been the lack of robust, empirical, independent evidence that addressed the core question of which governance principles should sport organisations adopt and implement to optimize their governance performance. To that end, a number of research areas are suggested below that should be prioritised by the international sport management research community.

First, researchers need to understand the differences and similarities that exist between the various governance principles and guidelines developed by respective national (sport) agencies over the last 15 years. By understanding why these agencies emphasise different principles and which ones are common, researchers may gain a clearer understanding of the potential foci for future studies of the adoption of governance principles over time and between jurisdictions and countries. As this review focused on English-language studies, researchers should expand the analysis to other language to capture potential differences related to culture and context. Researchers also need to look outside the sport sector and explore the applicability of more generic corporate governance principles and how they may be adopted by sport organisations. A common set of principles would facilitate comparative studies between countries that would assist researchers and managers in understanding the contextual or environmental factors which might help or hinder the impact the adoption of these principles or guidelines have on actual governance performance.

Second, this review’s authors support the continued focus on the development of a number of themes related to governance principles building on the emergence of gender quotas and the influence of national sport agencies discussed earlier. A further theme that could be developed might focus on the capacity and readiness of sport organisations to adopt governance principles and what conditions need to be met for sport organisations to be capable of adopting and implementing these in order to reap some reward in the form of improved governance performance. Future research efforts might also focus on the impact of mandatory versus suggested principles or guidelines might have on the adherence or impact on future governance performance at the organisational and individual board member level. To wit, if volunteer board members are increasingly required to implement good governance principles, whatever they may be, the workload may be such that the call for them to be paid, especially if they are to be independent board members, becomes a necessary outcome. The impact of such a situation merits further critical reflection. In essence, is implementing governance principles all positive or are there potentially negative impacts as well? A critical analysis of this issue is therefore warranted.

Third and finally, there is a need to more clearly define the concept of governance performance and how improved governance may be objectively measured. The underlying premise or assumption of adopting a set of good governance principles or guidelines is that doing so will lead to improved performance. At the moment, beyond the board structure aspect, the studies in this review have largely focussed on identifying the adoption of governance practices, rather than the impact their adoption or implementation (or failure to implement them effectively) has had on governance outcomes or performance. Understanding this aspect is critical for policymakers and funding agencies to make evidence-based decisions.

To conclude, future research efforts in this area need to contribute to a clearer understanding of what are the principles that matter for good governance, and they need to do so in such a way that is supported by sound theoretical frameworks and appropriate research designs and methods. This review’s authors hope this systematic review has provided greater clarity for understanding the research to date in this field and assisted set the course for future research efforts in this area.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mish Boutet, MIS (University of Ottawa Library), for his peer review of the SPORTDiscus search strategy.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Milena M. Parent

The authors are collaborating as part of a larger team on a major study funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada and Sport Canada titled: The New Sport System Landscape: Understanding the Interrelationships between Governance, Brand and Social Media in Non-Profit Sport Organizations. They have previously co-edited the SAGE Handbook of Sport Management published in 2017. This publication relates to their SSHRC grant that builds on their expertise in sport governance and sport management and their interest in improving the governance of sport, including the policies and actions able to be taken by federal and state or provincial governments to improve sport governance practices.

Notes

1. In this review, the term impact refers to the influence on, relationship between, or effect of a given governance principle on sport organisation performance.

References

- Adriaanse, J., & Schofield, T. (2014). The impact of gender quotas on gender equality in sport governance. [Article]. Journal of Sport Management, 28(5), 485–497. doi:10.1123/jsm.2013-0108

- Adriaanse, J. A., Jr. (2013). Gender dynamics on boards of National Sport Organisations in Australia ( PhD). University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. Retrieved from http://oatd.org/oatd/record?record=handle/:2123/%2F8950&q=sport%20AND%20governance

- American Psychology Association. (n.d.). Guidelines for reviewing manuscripts for training and education in professional psychology. Retrieved March 7, 2018 from http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/tep/reviewer-guidelines.aspx

- Australian Sports Commission. (2015). Mandatory sports governance principles. Canberra, Australia: Author.

- Bayle, E. (2005). Institutional changes and transformations in an organisational field: The case of the public/private ‘model’ of French sport. International Journal of Public Policy, 1(1–2), 185–211. doi:10.1504/IJPP.2005.007798

- Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2007). A framework for understanding the performance of national governing bodies of sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(3), 249–268. doi:10.1080/16184740701511037

- Bradbury, T., & O’Boyle, I. (2015). Batting above average: governance at New Zealand cricket. [Article]. Corporate Ownership and Control, 12(4), 352–363. doi:10.22495/cocv12i4c3p3

- Burger, S. (2004). Compliance with best practice governance systems by National Sports Federations of South Africa. University of Pretoria. Retrieved from http://oatd.org/oatd/record?record=handle/:2263/%2F41806&q=sport%20AND%20governance

- Chappelet, J.-L. (2018). Beyond governance: The need to improve the regulation of international sport. Sport in Society, 21(5), 724–734. doi:10.1080/17430437.2018.1401355

- Chappelet, J.-L., & Mrkonjic, M. (2013). Existing governance principles in sport: A review of published literature. In J. Alm (Ed.), Action for good governance in international sports organisations Final Report. Copenhague: Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies.

- Dimitropoulos, P. (2014). Capital structure and corporate governance of soccer clubs: European evidence. [Article]. Management Research Review, 37(7), 658–678. doi:10.1108/MRR-09-2012-0207

- Ferkins, L., Shilbury, D., & McDonald, G. (2009). Board involvement in strategy: Advancing the governance of sport organizations. [Article]. Journal of Sport Management, 23(3), 245–277. doi:10.1123/jsm.23.3.245

- Foster, M. J., & Jewell, S. T. (2017). Assembling the PIECES of a systematic review: A guide for librarians. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Garcia, B. (2008). The European Union and the governance of football: A game of levels and agendas. Ph.D., Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK. Retrieved from https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/5609

- Geeraert, A. (2017). National sports governance observer - benchmarking governance in national sports organisations. Play the Game. Retrieved January 22, 2018, from http://www.playthegame.org/theme-pages/the-national-sports-governance-observer/

- Geeraert, A., Alm, J., & Groll, M. (2014). Good governance in international sport organizations: An analysis of the 35 olympic sport governing bodies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 281–306. doi:10.1080/19406940.2013.825874

- Green, M., & Houlihan, B. (2006). Governmentality, modernization and the ‘disciplining’ of nation sporting organizations: An analysis of athletics in Australia and the United Kingdom. Sociology of Sport Journal, 23, 47–71. doi:10.1123/ssj.23.1.47

- Grix, J. (2009). The impact of UK sport policy on the governance of athletics. International Journal of Sport Policy, 1(1), 31–49. doi:10.1080/19406940802681202

- Hoye, R. (2004). Leader-member exchanges and board performance of voluntary sport organisations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 15(1), 55–70. doi:10.1002/nml.53

- Hoye, R. (2017). Sport governance. In R. Hoye & M. M. Parent (Eds.), Handbook of sport management (pp. 9–23). London: Sage.

- Hoye, R., & Cuskelly, G. (2003). Board power and performance in voluntary sport organisations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 3(2), 103–119. doi:10.1080/16184740308721943

- Hoye, R., & Cuskelly, G. (2004). Board member selection, orientation and evaluation: Implications for board performance in member-benefit voluntary sport organisations. Third Sector Review, 10(1), 77–100.

- Hoye, R., & Doherty, A. (2011). Nonprofit sport board performance: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Sport Management, 25(3), 272–285. doi:10.1123/jsm.25.3.272

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G.; The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

- Parent, M. M. (2016). Stakeholder perceptions on the democratic governance of major sports events. [Article]. Sport Management Review, 19(4), 402–416. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2015.11.003

- Parent, M. M., Kristiansen, E., & Houlihan, B. (2017). Governance and knowledge management and transfer: The case of the Lillehammer 2016 winter youth olympic games. [Article]. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 17(4–6), 308–330. doi:10.1504/IJSMM.2017.10008118

- Play the Game. (2015). Sports governance observer 2015. The legitimacy crisis in international sports governance. Copenhagen: Author.

- Sisjord, M. K., Fasting, K., & Sand, T. S. (2017). The impact of gender quotas in leadership in Norwegian organised sport. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 9(3), 1–15.

- Tacon, R., & Walters, G. (2016). Modernisation and governance in UK national governing bodies of sport: How modernisation influences the way board members perceive and enact their roles. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(3), 363–381. doi:10.1080/19406940.2016.1194874

- Taylor, M., & O’Sullivan, N. (2009). How should national governing bodies of sport be governed in the UK? An exploratory study of board structure. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(6), 681–693. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00767.x

- University of Warwick (n.d.). Basic protocol template. Retrieved January 16, 2018, from http://uottawa.libguides.com/systematicreview/planning

- Walters, G., & Tacon, R. (2018). The ‘codification’of governance in the non-profit sport sector in the UK. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(1), 482–500.

- Walters, G., Trenberth, L., & Tacon, R. (2010). Good governance in sport: A survey of UK National governing bodies of sport. London, UK: University of London.