Abstract

The aim of this study has been to analyse the value chain of African leafy vegetables in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. This was done by identifying the prominent value chain actors, institutions governing the chain, the infrastructural endowments, key factors and challenges affecting the success or failure of the value chains for African leafy vegetables. Relationships among the value chain actors were weak, with transactions based mostly on spot markets. While smallholder farmers attain high gross margins, their intention to take part in the mainstream markets are prevented by lack of technical advice on production, lack of packaging and processing services, poor infrastructure, deficiency of contractual agreements between actors, and lack of access to finance. Although producers currently attain relatively higher gross margins, more benefits might be realized if government services (such as training, seed production and distribution) could either be decentralized or privatized. Future policy interventions should focus on promoting value addition along the African leafy vegetable chain, provision of cold storage facilities by municipalities closer to smallholder farmers in the rural areas and this will stabilize farm gate prices to encourage continuation of production.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Despite the growth in the demand for African leafy vegetables (ALVs), their consumption levels are still low in African diets. This study analyses the value chain of African leafy vegetables in the Limpopo Province. The study has generated policy relevant knowledge regarding the value chains for ALVs from farmers to consumers. The findings revealed that farmers sell their produce to consumers, some to supermarkets, and some to middlemen. Although farmers are able to make higher margins compared to other value chain actors, it is still difficult for them to penetrate the mainstream market. Value chain actors also face challenges such as lack of production advice, lack of packaging and processing services, poor infrastructure, absence of contractual agreements between the value chain actors. It will be imperative for policy interventions to focus on promoting value addition along the ALVs chain to achieve employment creation, nutrition security, and diversified food portfolios along the value chain.

1. Introduction

African leafy vegetables (ALVs) are known by many names such as indigenous leafy vegetables (Neugart, Baldermann, Ngwene, Wesonga, & Schreiner, Citation2017), wild vegetables (Nesamvuni, Steyn, & Potgieter, Citation2001), and traditional leafy vegetables (Odhav, Beekrum, Akula, & Baijnath, Citation2007; Vorster, Stevens, & Steyn, Citation2008). Due to different languages in South Africa, they are called imfino in Nguni languages (isiZulu and isiXhosa), morogo in Sotho languages (SeSotho, Setswana, and Sepedi) and miroho in tshiVhenda (Maunder & Meaker, Citation2007). Jansen Van Rensburg, VanAverbeke, Slabbert, Faber, van Jaarsveld, van Heerden, Wenhold & Oelofse (Citation2007) defined ALVs as “plant species which are either genuinely native to a particular region, or which were introduced to that region for long enough to have evolved through natural processes or farmer selection”. Asfaw (Citation2001) defines them as “edible plants that are biologically indigenous to an area, while introduced vegetables are those vegetables that have been introduced into a particular area and have not physiologically adjusted to the local conditions and subsequently require many agricultural inputs”. They have their natural habitat in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) while some of them were introduced over a century ago and, due to long use, have become part of the food culture in the sub-continent. The Plant Resources of Tropical Africa (PROTA) reported an estimated 6,376 useful indigenous African plants of which 397 are vegetables. In the same reference, it is indicated that information is available on cultivation practices for 280 indigenous ALVs (PROTA, Citation2004).

According to Chweya and Eyzaguirre (Citation1999), ALVs have long played an important role in the nutrition and diet of sub-Saharan African people. They are indispensable ingredients of soups or sauces that accompany carbohydrate staples. The utilization of ALVs in South Africa is as old as the history of modern man. According to Fox and Norwood-Young (Citation1982) and Parsons (Citation1993), the native people of Southern Africa, Khoisan people, who have been living for at least the past 120 000 years, relied on gathering plants for consumption from the wild to survive. Bundy (Citation1988) also added that the Bantu people, who started to settle in South Africa about 2 000 years ago, also collected ALVs from the wild. When crops had failed or livestock herds had been decimated, they depended on hunting and collecting edible plants (Peires, Citation1981). Collecting and cultivating ALVs continues to be widespread among African people in SSA (Husselman & Sizane, Citation2006; Jansen Van Rensburg et al., Citation2004; Modi, Modi, & Hendriks, Citation2006) even though western influences have considerably modified their food consumption patterns.

In the Limpopo Province, the agricultural sector is an important source of employment of rural people and it plays a significant role in the reduction of poverty and food insecurity (Baloyi, Citation2010). Due to its employment abilities and its reputation as a source of income for smallholder farmers, farm workers, and street vendors/hawkers, agriculture is an engine of economic growth. Machethe et al. (Citation2004) also revealed that agriculture is one of the greatest contributors to household income in the Limpopo Province, although smallholder farmers’ lack of participation in commercial agriculture is a major cause for concern. Majority of the smallholder farmers are mostly excluded from high-value markets due to a number of socioeconomic and institutional challenges. Commercial farmers in the Province mostly sell their products through formal markets (such as fresh produce markets and supermarkets) by formal contract agreements, however, most smallholder farmers sell their products through informal markets (such as street vendors/hawkers and door-to-door sellers). The number of ALV species in Africa is far greater than exotic ones and are environmentally adapted to the area better than the introduced exotic vegetables. They are also the providers of low-cost quality nutrition for many households in rural and urban areas (Chweya & Eyzaguirre, Citation1999). Despite their nutritional benefits, ALVs remain underutilized crops in Limpopo Province (Van Jaarsveld et al., Citation2014).

According to Njume, Goduka, & George (Citation2014), ALVs are most important and a source of nutrition in the diet of rural South Africans. However, most of the species are not well known or are used only locally. Little or no attention has also been given to these ALVs by local, national and international research institutions. There is little research and development investment in the production, processing, and marketing of ALVs and their products. There is hardly any research on the challenges and opportunities of integrating ALVs into mainstream agricultural value chains. Not much is known about the prominent value chain actors and institutions governing the ALV chains. Thus, it is timely to undertake value chain analysis to generate information for all actors to assist them to better organize the chain. Kaplinsky and Morris (Citation2001) reported a value chain to be a process by which products are conceived, through the different stages of production and transformation, made up of a number of actors from input suppliers, farmers and processors, to exporters and consumers/buyers engaged in the activities required to bring an agricultural product from its conception to its end use. Interesting features of a value chain analysis is that it is holistic and looks at all the processes, institutions, actors, connections, value adding and constraints occurred along the value chain.

Most agricultural produce including ALVs are sold unprocessed because of the absence of agro-processing industries in the Province. Smallholder farmers in the Province are mainly faced with obstacles such as lack of access to agricultural support services (i.e. access to credit and extension services). Even if many of them are highly motivated to become commercial farmers, unless they are intrgrated into the value chain and get access to credit, the dream of revitalizing, increasing and strengthening the sub-sector will continue to be a challenge (Nesamvuni, Oni, Odhiambo, & Nthakheni, Citation2003).

Along the ALV value chain, various problems (such as poor infrastructure, lack of financial assistance, etc.) hinder the possible benefits that the value chain actors should have been attained. Therefore, the investigation of ALV value chains is crucial in this study area. Few programmes promoting ALV production exist, such as Ilima/Letsema in Limpopo Province. The Ilima/Letsema programme was specifically targeted at increasing food production to fight poverty (Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries [DAFF], Citation2012). However, no study has examined the impact and challenges of the programme as yet.

Very few studies were conducted to investigate ALV value chains and related subjects in Southern Africa (e.g. Bidogeza, Afari-Sefa, Endamana, Tenkouano, & Kane, Citation2016; Chagomoka, Afari-Sefa, & Pitoro, Citation2014; Lenné & Ward, Citation2010; Shackleton, Pasquini, & Drescher, Citation2010; Weinberger, Pasquini, Kasambula, & Abukutsa-Onyango, Citation2011). The studies have mostly investigated issues on production systems characteristics of ALVs, nutritional attributes of ALVs, the nature of ALV marketing outlets, and women participation in the production and marketing of ALVs, but have hardly looked at the entire value chain, particularly from seed production and distribution through to produce marketing except for Chagomoka et al. (Citation2014). In South Africa, little research has been done to assess and investigate the relationships between the value chain actors along the ALV value chains. This study is using a value chain approach (VCA), which reflects on the various activities from production to the delivery of ALVs to final consumers. The VCA makes it possible to discover unexploited possibilities and prioritize interventions that might enhance operations at various levels of the whole chain (Chitundu, Droppelmann, & Haggblade, Citation2009). Thus, this study aims to analyse the value chain of ALVs in the Limpopo Province with a special emphasis on value chain actors, institutions governing the chain, and the infrastructural endowments. This was done by identifying the value chain actors and mapping out the value chain interventions that are needed to improve the production, processing, and marketing of ALVs in the Province and beyond.

2. ALVs marketing and value chain challenges

Osano (Citation2010) reported that although ALVs are a crucial source of food, feed, natural medicine, and other products of socioeconomic value, they are also a vital element in the livelihood of people worldwide. Due to the low competitiveness of the value chain actors along the chain, ALVs are untapped for different reasons, from input suppliers all the way to the retailers. And also, the private and public service providers are not acting on the development and promotion of appropriate technology packages for ALVs. Agriculture and rural development policies and programmes are mostly focusing on a few commodities. There is always mistrust amongst value chain actors, and also between private and public stakeholders. No one takes responsibility for the lack of services that smallholder farmers receive (such as agricultural extension and agricultural credit), which is due to institutional failures. Infrastructural endowments (or their lack thereof), value chain governance issues, and challenges of consistent supply of acceptable quality products are the key challenges determining the success (or otherwise) of producing, processing and marketing ALVs.

According to Boateng, Amfo, Abdul- Halim, and Yeboah (Citation2016), the lack of storage facilities is one of the constraints that militate against the marketing of ALVs. This enforces most traders to purchase ALVs in smaller quantities to be sold in a day or few days. As ALVs are highly perishable, which leads to spoiling, particularly at the retailer point. Lack of suitable street vendor/hawkers infrastructure (such as shade) to publicly show or display the produce on the marketplace for sale increases spoilage, which leads to lower prices and sales. Chagomoka et al. (Citation2014) also recorded that excessive perishability of ALVs is a serious challenge in the marketing and distribution of the produce. Will (Citation2008) also reported that the perishability of ALVs causes them to lose quality drastically after harvest and until consumption. This poses major challenges in distribution and marketing. In addition, Boateng et al. (Citation2016) record that lack of financial access is one of the constraints ALV farmers and traders face as it prevents them from producing on a larger scale and purchase the produce on a larger scale for sale, respectively.

Other challenges for ALVs marketing involve product bulkiness which makes it expensive to transport, store, handle and process in fresh form. These factors lead to large losses if they are left unsold. The processes of washing, cooling, and proper management are important from the time of harvest until the products are put on display. According to Nonnecke (Citation1989), leafy vegetables need to have a longer shelf life and remain attractive to the consumer after having been purchased. ALVs have a lower level of demand as compared to exotic vegetables leading to lower sales and thus attract lower prices leading to reduced returns (Boateng et al., Citation2016; Lenné & Ward, Citation2010; Lyatuu et al., Citation2009). Onyemauwa (Citation2010) also found the same results that limited supply; insufficient capital and spoilage are major challenges facing the management of ALV value chains from the smallholder perspective.

Osano (Citation2010) also reported that inadequate skills affect both production and marketing of indigenous vegetables. In addition, poor infrastructure such as bad roads, which are difficult to use during rain seasons, hinder timely transportation of ALVs to the market. Moreover, alternative product forms and markets can hinder the availability of vegetables since different breeds and qualities can be cultivated for the fresh and processed markets.

3. The value chain and success stories

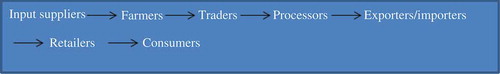

Kaplinsky and Morris (Citation2001) describe a value chain as a range of activities which are required to bring a product or service from conception, through the different phases of production, transformation and delivery to final consumers. Value chain analysis seeks to characterize how chain activities are organized, costs incurred, value created and benefits shared among chain participants. It also deals with the institutional arrangements governing the activities, actors, their relationships, the linkages and market prices in and out of each actor in the chain. The costs incurred, the values added and the benefits accrued by each actor in the value chain are the outcomes of these governing institutions. United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (Citation2009) describes a value chain as “a set of businesses, activities and relationships involved in creating a final product or service”. It builds on the idea that a product is rarely consumed in its original form but becomes transformed, combined with other products, transported, packaged, and marketed until it reaches the consumer. In this sense, a value chain describes how producers, processors, buyers, sellers, and consumers separated by time and space gradually add value to products as they pass from one link in the chain to the next. In a typical agricultural or food value chain, the chain actors who actually transact a particular product as it moves through the value chain include input (e.g. seed) suppliers, farmers, traders, processors, transporters, wholesalers, retailers and final consumers (Figure ).

However, in reality, value chains are more complex than the above example. In many cases, the input and output chains comprise more than one channel and these channels can also supply more than one final market. The channel also could branch at any stage as there are multiple options (of actors) at each stage of the chain. A comprehensive mapping, therefore, describes interacting and competing channels (including those that perhaps do not involve smallholder farmers at all) and the variety of final markets through which they interact (Figure ).

In South Africa, an indigenous underutilized crop, green rooibos tea was first marketed in 1904 in its fermented form, and recently is a new product on the market. Its use has moved beyond a herbal tea to intermediate value-added products such as extracts for the beverage, food, nutraceutical and cosmetic products (Joubert & De Beer, Citation2011). Rooibos tea is gaining popularity with consumers and it is known to originate from South Africa and to have high antioxidant potential. According to Jones, Hoffman, and Muller (Citation2015), a droëwors formulation using a combination of game meat and beef fat with the addition of rooibos tea extract is a successful addition to the processed meat market. In addition, rooibos is also used as the main ingredient for haircare products, products for anti-acne, baby products, after-sun products, and skin care products (Tiedtke & Marks, Citation2002) sold around the world.

In the case of sweet piquanté peppers, a cultivar of chilli pepper known as peppadews, they are mainly produced, processed, distributed and exported from the Limpopo Province (Uys, Citation2017). The Piquante Pepper fruit is processed for removal of the seeds and reduction of the heat of the pepper to more palatable levels and is then pickled and bottled. It is mainly sold by large supermarkets such as Pick n Pay, Woolworths and Checkers in South Africa. It is also exported to countries such as the Americas and Europe. This are different products processed from peppadew: goldew peppers range, jalapeño peppers range, pickled onions range, atchar range, pasta sauce range, relish range, cream cheese range, roasted peppers range, and splash-on sauce range (Peppadew, Citationn.d.).

Amaranth (family Amaranthaceae) is an under-exploited and under-utilized plant in South Africa with an exceptional nutritive value. Only its leaves are consumed in South Africa. However, in Kenya, through extensive research, grains from amaranth crop are used as food ingredients (Emire & Arega, Citation2012) and can diversify farming enterprises as they can be expected to prevent food depletion and to contribute to world food production (Saunders & Becker, Citation1984). Its grains are also utilized in several ways: cooked as a cereal, ground into flour, popped like pop corns, sprouted, toasted, cooked with other whole grains, and added into stir fry or soups and stews as a nutrient dense thickening agent. The flour can be used to prepare porridge, pizza, pasta, pancake, flat bread, and Ugali (pap/porridge in South Africa), among others. He and Corke (Citation2003) also revealed that amaranth grain produces oil which is considerably higher in squalene compared to other cereals. A study by Beswa et al. (Citation2016) suggested that the addition of amaranth leaf powder to provitamin A-biofortified maize snacks had a significant effect on their nutritional attributes. The nutrient content (including essential amino acids, provitamin A and Fe) of the snacks was significantly improved by the addition to Amaranth leaf powder. Value addition on amaranth in Kenya has improved the livelihoods of farming households.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data and sampling

The study was conducted in the three districts of the Limpopo province: Capricorn, Vhembe, and Mopani. Most of the area in the three districts is drought-prone; however, some of the areas have a better rainfall distribution. Maize (Zea mays) is the primary staple in Limpopo province; it is prepared as a paste called porridge or pap and served with dark green leaves (mainly ALVs), and/or beans as well as meat. Faber, Oelofse, Van Jaarsveld, Wenhold, and Jansen Van Rensburg (Citation2010) reiterate that ALVs have always been part of Limpopo peoples’ diets even in urban areas such as Polokwane, Tzaneen, Giyane and Thohoyandou. In addition, they also note that although leafy vegetables are produced everywhere in the Province, the study areas are the major leafy vegetable producing locations.

This study followed a purposive sampling method. Districts visited were purposively selected. Bearing in mind what the value chain analysis entails, data were collected in each district using formal interviews at producer level and informal interviews at input, processor and distributor levels. In addition, a snowball method by Goodman (Citation1961) was used for data collection from various ALV value chain actors. Initially, data were collected from ALV producers who identified input sources and other value chain actors, then data were also collected from the buyers/consumers. Interviews with identified actors such as input suppliers and market intermediaries led to them identifying other actors and institutions having an influence in the ALV value chain. Data from ALV producers were collected before the other value chain actors were contacted. Questions for the value chain actor survey were structured in such a way that the data and information generated were in harmony with the period when producers were interviewed. Each discussion lasted about 30–40 minutes, covering various roles that each participant plays in the ALV value chain, the challenges faced by the value chain actors, and on potential areas for improvement.

5. Empirical results and discussion

Table shows the list of value chain actors interviewed and their location. NTK, supermarkets (such as Shoprite), and other smallholder farmers were identified as actors who supply inputs. The Agricultural Research Council (ARC), Mayford seeds, and Starke Ayres (all based in Gauteng Province) including LDA were also identified as input suppliers. Smallholder farmers from the three selected districts were involved. Traders identified were supermarkets (such as Pick ’n Pay, Shoprite, OK, Spar, Boxer, Woolworths, Food Lovers Market and Goseame open market) as well as street vendors/hawkers. Consumers were also identified as actors in the value chain. Unfortunately, there was an absence of processing, wholesalers, and export actors along the ALV value chain.

Table 1. List of interviewed ALV value chain actors, 2015

5.1. Value chain analysis of ALVs

The value chain of ALVs in the Limpopo Province is simple and undeveloped with no much infrastructure. The main actors in the value chain were input suppliers, smallholder farmers, traders (such as retailers, street vendors/hawkers) and consumers. The first marketing channel was from the smallholder farmers to trader (i.e. street vendor/hawker) or consumer. The other marketing channel was from farmer to trader (i.e. retailer) and then to consumer. Other smallholder farmers sold directly to the middlemen (collectors/distributors) who take their ALVs to retailers. The final end market of ALVs is domestic consumption.

5.1.1. Input suppliers

Currently in the Province, there are very few input suppliers for ALV production. Given the lack of access to inputs, some local input companies (such as NTK, Mayford seeds and Starke Ayres) and retailers (such as Shoprite/Checkers, Pick ’n Pay, SPAR) take part in input provision to smallholders. This has compelled smallholder farmers to walk and also drive long distances to purchase inputs from the local dealers and towns within a radius of 10–20 km. Inputs for production purposes (such as seeds, agro-chemicals, and farm implements) were sold by NTK situated in towns (such as Tzaneen, Giyane, Thohoyandou, and Polokwane). Inputs such as seeds supplied by NTK are imported from Mayford seeds and Starke Ayres located in the Gauteng Province. Other inputs are imported from international suppliers. Supermarkets such as Pick ‘n Pay and Shoprite/Checkers sell ALV seeds supplied by Mayford seeds and Starke Ayres, though they do not sell ALVs at the moment. In addition, LDA district offices under the Ilima/Letsema programme provide inputs (such as seeds, fertilizers and pesticides) to smallholder farmers in the Province. The ARC also provides information through research and development on seed and production to the LDA, then information will be transferred to smallholder farmers in the Province. Among the ALVs produced, mustard greens and collard greens seeds were the most traded. Some smallholder farmers also acted as input dealers by buying inputs in large quantities from NTK and selling, and also by collecting seeds from healthy and disease-free plants.

5.1.2. Smallholder farmers

From the study area, ALVs were mainly produced by smallholder farmers, most of them on less than a hectare of land. ALVs produced include mustard greens (mochaina), collard greens (phophorokga), cowpea leaves (monawa), and pumpkin leaves (dithaka). Smallholder farmers they not use good agricultural practices (such as integrated pest management practices as well as drip irrigation) but used the traditional production practices for ALV production. Seeds for mustard greens and collard greens were the only seeds commercialized. ALVs such as cowpea leaves and pumpkin leaves among others, were produced using local landraces. Some smallholder farmers are involved in supplying inputs such as seeds which they harvest from the crops they grow.

The average age of interviewed producers was about 55 years, and the majority (69%) were women. The producers reported to have approximately 15 years of ALV farming experience and 31% of smallholder farmers do not have a formal education. They also have limited access to formal markets as only 42% reported to have access to these markets. Given the relatively high perishability of leafy vegetables, producers are at times compelled to sell their produce immediately after harvest, which leads to low farm gate prices. Most producers (76%) were not part of farmers’ organizations. However, most smallholder farmers involved in farmers’ organizations were able to access technical production services and seeds from the LDA. Due to the lack of improved ALV cultivars as well as new technologies, ALV yield levels were low.

However, there are no linkages between the smallholder farmers and processors, wholesalers and export markets. If these three missing linkages can be established through the formation of both public and private processing, and wholesale companies and identifying export market opportunities, smallholder farmers will most likely benefit.

5.1.3. Middlemen/traders

Traders are people who purchase products from producers and then resell them to consumers. The main functions of these actors in Limpopo included collection of ALVs, maintaining product quality until they are transferred to the next agent, hawker, and door-to-door marketing. Household consumption and income generation were the main aims for producing and marketing ALVs by value chain actors. Besides home consumption, ALVs were only sold fresh in traditional fruits and vegetable markets and streets without any value added on them.

Large retailer (supermarket) chain stores such as Pick ’n Pay, Shoprite/Checkers, and OK explained that they have contract agreements with their approved suppliers and distributors who meet their quality standards. Shoprite/Checkers through their distributors, Fresh Mark, buy their vegetables from the smallholder farmers. They do not have a direct relationship with farmers, so any potential supplier approaches Fresh Mark instead of Shoprite/Checkers directly. Fresh Mark indicated that they had never bought ALVs but would be willing to try them in the future; research indicated that there is a guaranteed and increasing demand for ALVs in the Limpopo Province. However, some supermarkets (such as SPAR, Boxer, and franchised Shoprite) had a direct relationship with smallholder farmers, and they sell ALVs. OK supermarkets situated in the nearest towns closer to the villages buy ALVs from the smallholder farmers to sell to the local consumers. All these supermarkets trade with smallholder farmers with no formal contract. If the quality of the product is acceptable, they buy on the spot. The Goseame open market is operating successfully in Polokwane, and it buys ALVs directly from farmers. Just like with supermarkets, there is no formal contract between this open market and the farmers. Food Lovers’ Market does not currently sell ALVs but is willing to consider selling these in the future.

The only municipality fresh produce market (FPM) that was located in Polokwane is no longer in operation. Now smallholder farmers have to send their produce to Tshwane FPM and Johannesburg FPM in the Gauteng Province. An opportunity exists to establish a municipality FPM in the capital city of Polokwane with the intention to consolidate and collect products being supplied to various markets. This will benefit both black smallholder farmers and emerging famers in the Province.

Processing of ALVs (such as canning and branded packaging) to meet the young and urban dwellers’ needs and preferences is not practised in the Limpopo Province. Smallholder farmers use the old way of sun-drying ALVs, and young and urban dwellers do not consume such ALVs. Pumpkin leaves and cowpea leaves were sundried after cooking and/or blanched, then preserved for home consumption during off-season. However, during the off-season, the processed ALVs might be sold to interested buyers in the rural areas. Regarding the exporting of ALVs by smallholder farmers, currently there are no export activities for ALVs in the Limpopo Province. ALVs are currently only sold locally. Linkages between the traders and processors as well as the export market will most likely benefit both the traders and smallholder farmers. The inclusion of wholesalers, hotels and restaurants will also strengthen the value chain of ALVs. Hotel and restaurants will come up with new sophisticated ways of preparing ALVs that will be included in their menus to attract urban dwellers and the rich consumers who view ALVs as food for the poor.

5.1.4. Consumers

In the three districts surveyed, the average household head was 44 years old, with an average family size of four members. Approximately 42% of the consumers were males and resided in the urban areas (47%). Ninety-six per cent of the sampled consumers were aware of ALVs, and it takes them an average of about 7 km to reach the ALVs market. Consumers scored ALVs in terms of Taste and Nutrition on average 3.59 and 4.36, respectively, on a scale of 1–5 (where 1 is low and 5 is high), reflecting the importance of these attributes among the sample consumers. In addition, an average low score of 1.86 for ALVs in terms of Availability was recorded, which implies that ALVs are not available throughout the year as they are seasonal. Older consumers in the urban areas far from the ALV market indicated that they are not willing to pay a premium for ALVs. ALVs were consumed mainly by older people based in rural areas, those who are aware of ALVs and having a belief that ALVs are tasty and nutritious.

5.2. Relationships amongst ALV value chain actors in Limpopo Province

There is a relationship amongst the value chain actors, and this was established based on spot markets (actors negotiate on price, quantities, and other requirements directly at the market). Figure shows a summary of the ALV value chain actor linkages in the study area.

Local suppliers usually produce inputs such as seeds and pesticides, while smallholder farmers purchase from them. Government R&D divisions, such as the ARC, develop more breeding and technology to be used by smallholder farmers. Smallholder farmers considered access to financial services, availability of quality ALV cultivars, or good infrastructure as crucial factors to improve efficiency. Middlemen located in towns (collectors/distributors) obtain ALVs from smallholder farmers and sell to traders. Traders such as supermarkets and street vendors/hawkers directly sell their produce sourced from smallholder farmers to consumers.

As processing activities of ALVs in the Limpopo Province are currently absent, there is a potential linkage between smallholder farmers and the agro-processing industry that is expected to benefit all actors in the value chain. Processors will sell their produce to traders and also to the export market to realize higher profits. This will also benefit smallholder farmers due to higher volume demand by hotels, supermarkets and other retailers. In addition, smallholder farmers can also link with the export market.

5.3. Distribution of gross margins along alternative ALV marketing channels

In general, ALVs are mainly marketed through three channels: (i) smallholder farmers sell directly to consumers; (ii) smallholder farmers sell to retailers; and (iii) smallholder farmers sell to middlemen (collectors). Table shows the estimated gross margins for market participants in different ALV marketing chains. The description of the activities done by the value chain actors from the farm to the consumers were used to estimate the variable costs and returns. Computations were performed on a per unit basis (bundle of fresh ALVs). A single production cycle takes about three to four months, and in this period, ALVs were regularly harvested, with the amount produced decreasing over time.

Table 2. Estimated gross margins for market participants in different ALV marketing chains, Limpopo Province, 2015

In marketing channel 1, after the production stage, labour is required for harvesting and packaging in bundles and selling ALVs to community members. Smallholder farmers (44%) sell their products at the farm gate and have no transportation cost as consumers buy ALVs from where they are produced at an average price of R7/bundle. Considering the cost of production inputs, the variable marketing cost at the farm gate was estimated at R0.50/bundle.

In marketing channel 2, the average producer price for the retail market is R8/bundle. Visual inspection for freshness and colour are performed by supermarkets to assess ALV quality at the receiving point. Producers who sell to the retail market travel between 10km to 40km with an average distance of 20.6km. These smallholder farmers rely on their own transport. The number of trips to the market is dictated by the quantity harvested and the demand. On average, producers make ten return trips per cycle, each covering about 70km using own transport. Marketing cost was estimated at R1.50/bundle. The average consumer price from supermarkets is R10/bundle of the equivalent product with variable marketing costs averaging R0.50/bundle. Variable marketing costs for retailers consist mainly of labour costs for receiving, screening, and pricing. In supermarkets, ALVs are displayed in open baskets and generally sold out within a day. Data on the price of electricity for storage costs were not needed for the analysis because the ALVs are not refrigerated but sold fresh after harvest.

In marketing channel 3, middlemen buy the already packed ALVs from producers at R7.20/bundle of the equivalent and transport them using their own vehicles to retailers where they are sold at an average price of R8.00/bundle. Estimations indicate that middlemen spend an average of R0.30/bundle on marketing costs. Smallholder farmers who sell through channel 3 do not have to depend on the number of buyers turning out like with the farm gate option, although there are no written contracts and they have less bargaining power in setting prices. Worth noting is that the percentage of benefits (gross margin) received by middlemen is far less as compared to other actors in the value chain. This may be a reason why retailers have no incentive to buy their supplies at prices much higher than those offered by the smallholder farmers.

Table indicates that producers enjoy higher gross margins. However, the proportion reduces with an increase in the number of participants in the marketing channel. The estimations indicate that smallholder farmers earn relative gross margins of about 64% from selling directly to the consumer, 56% from selling directly to the retailers, and 50% from selling through middlemen. Even though the gross margins are lower from selling through the middlemen, mainly because of transportation costs, a large quantity of the ALVs was traded through this channel as middlemen as well as street vendors/hawkers offer a better price and a relatively more dependable market by buying in bulk. Quaye and Kanda (Citation2004) also reported the same results.

Other than the absence of written contract agreements between the actors and having less bargaining power in setting prices, smallholder farmers who sell through the farm gate channel rely on the number of buyers. However, the middlemen provide an important linkage between some smallholder farmers and consumers, as a large quantity of ALVs was traded through channel 3. These findings concur with Mabuza, Ortmann, and Wale (Citation2014) and Bwalya (Citation2014). This is mostly because middlemen hardly add any value from what they buy from smallholder farmers.

5.4. ALVs value chain constraints

Constraints identified by value chain actors, including the smallholder farmers, in the course of the field survey are summarized in Table . Regarding input demand, the key constraint was low input demand by smallholders who produce most ALVs. On the supply side, there still remains lack of good quality seed. These constraints offer opportunity for numerous interventions which includes alternatives to improve input markets, provision of good quality seed, regulation of input price and control to guarantee fair prices for high quality seed. The results concur with Padulosi, Thompson, and Rudebjer (Citation2013) who reported that lack of propagation materials and seeds, poor seed supply systems, poorly trained human capacity, and lack of other agrochemicals are input challenges for ALVs.

Table 3. Key constraints faced by actors of the ALV value chain in Limpopo Province, 2015

On the production side, the common constraints mentioned are lack of technical advice on production, the absence of contractual agreement with buyers, and lack of access to finance. Chadha, Oluoch, Saka, Mtukuso, and Daudi (Citation2003) also reported the same production constraints. The constraints suggested the following interventions: promote and disseminate information on production techniques; training on business and contract negotiations management, and promote tailor-made finance sources to ALVs smallholder farmers. Pudasaini, Sthapit, Suwal, and Sthapit (Citation2013) argue that one of the aims of smallholder farmers is to make ALV production cost effective. However, quality inputs (such as fertilizers, seeds, and agro-chemicals) are hardly developed and promoted. Attention is on locally available seeds, compost, manure and locally produced technologies to ensure the availability of inputs, and safe and healthy food for households.

The absence of processing and packaging services of ALVs were identified as constraints in the value chain. Nenguwo (Citation2004) suggested that the training and skills in processing and packaging of ALVs by public and private sectors might be a desirable alternative. Even though there is an increase in growing of ALVs in Limpopo Province, there is a loss in the quantity and quality harvested. The results are consistent with Ngugi, Gitau, and Nyoro (Citation2007) and Chagomoka et al. (Citation2014) where it was reported that the supply of ALVs failed to meet the demand. Smallholder farmers are facing difficulties in accessing high value markets, such as supermarkets, and they are regularly exploited by the middlemen. They are not able to supply the agreed quantity and quality consistently. These present opportunities for agribusinesses and other middlemen to add value and upgrade existing value chains of ALVs.

In addition, retailers noted the inability of smallholder farmers to supply the required quantity of ALVs on time. The challenge is that many smallholder farmers own a small portion of land which means little marketable surplus, which in turn, results in low and inadequate supply to the market. If smallholder farmers form and manage collective action organizations to supply ALVs (such as cooperatives), the problem of insufficient and poor quality supply could be addressed.

The other value chain constraint is the procurement models of supermarkets in retail outlets such as Shoprite/Checkers, Pick ‘n Pay, and Woolworths. This has a negative impact on smallholder farmers. Large supermarkets prefer to do business with large scale farmers and believe that it is risky and costly to deal with smallholder farmers. In addition, there is no link between smallholder farmers, the wholesalers and FPM which are important access points for smallholder farmers. Large supermarkets also manage to take over the markets of those small retail outlets that purchase from smallholder farmers. High transaction cost of dealing with many smallholder farmers is usually too high for suppliers of such services, and hence most of them do not have any incentive to deal with these farmers. This transaction costs are worsened by factors such as low production, low levels of education, lack of physical infrastructure, poor communication systems, and low density of economic activity in the poor rural areas. Smallholder farmers are unable to supply their produce regularly and in time, in particular, when the quality is specified, and in responding quickly to the changing buyer’s preferences.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed to identify the value chain actors and factors hampering ALV value chains in Limpopo Province. The following actors were identified along the ALV value chain: inputs suppliers, smallholder farmers, traders, and consumers. The findings reveal that although smallholder farmers currently make high gross margins as compared to other participants in the value chain, more returns can be realized if government services (such as training, seed production and distribution) could either be decentralized or privatized. In addition, policy and investment interventions are required in the promotion of processing ALVs for value addition, provision of cold storage facilities nearer to the smallholder farmers in rural areas and nearer to the urban consumers, and to encourage continuation of production by stabilizing farm gate prices.

Agro-processing should also be encouraged along the value chain of ALVs to provide smallholder farmers with market opportunities and help reduce the postharvest losses . This could also involve processing ALVs from formally contracted smallholder farmers for higher value markets, distributors and wholesalers. In addition, there could be a possibility to produce solar dried vegetables for local as well as export markets. This will ensure availability for and accessibility by consumers in urban areas. In addition, the re-establishment of the Polokwane FPM may be necessary for market access and this will benefit smallholder farmers in the Province.

The findings also suggest that smallholder farmers’ plans to expand production capacities are hampered by the inability to access quality inputs such as seeds and financial support. These constraints are partly responsible for the extremely low-produced volumes, poor quality of ALVs and inconsistent market supply of ALVs, prompting major ALV traders (e.g. supermarket chain stores) and other traders not yet ready to sell them at all. The study recommends the formation of farmer groups, capacity development, and value addition through processing, infrastructural development and stronger linkages among value chain players.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Grany M. Senyolo

Ms Grany M. Senyolo is currently an Agricultural Economics doctoral student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and a lecturer at the Department of Crop Sciences at Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa. Her research focus areas are underutilized plant species, food security, agricultural and rural development, economics of post-harvest loss, and agro-processing.

Edilegnaw Wale

Edilegnaw Wale is currently an Associate Professor in Agricultural Economics at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. His research focus areas are the economics of water use in agriculture, natural resources economics/agrobiodiversity economics, agricultural development economics, cost benefit analysis of development projects/programs/policies, and impact assessment/technology adoption.

Gerald F. Ortmann

Gerald F. Ortmann is a Professor of Agricultural Economics at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. His main research interests include Farm and Financial Management, Production Economics, Agricultural Policy, and Institutional Economics, with a focus on promoting the competitiveness of small-scale and large-scale farmers in South Africa.

References

- Asfaw, N. (2001). Origin and evolution of rural home gardens in Ethiopia. Biologiske Skrifter Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 54, 273–286.

- Baloyi, J. K. (2010). An analysis of constraints facing smallholder farmers in the Agribusiness value chain: A case study of farmers in the Limpopo Province ( Master’s thesis). University of Pretoria, South Africa.

- Beswa, D., Dlamini, N. R., Siwela, M., Amonsou, E. O., & Kolanisi, U. (2016). Effect of Amaranth addition on the nutritional composition and consumer acceptability of extruded provitamin A-biofortified maize snacks. Food Science and Technology, Campinas, 36(1), 30–39. doi:10.1590/1678-457X.6813

- Bidogeza, J. C., Afari-Sefa, V., Endamana, D., Tenkouano, A., & Kane, G. Q. (2016). Value chain analysis of vegetables in the humid tropics of Cameroon. Invited paper presented at the 5th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists, September 23-26, 2016, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Boateng, V. F., Amfo, B., Abdul- Halim, A., & Yeboah, O. B. (2016). Do marketing margins determine local leafy vegetables marketing in the Tamale Metropolis? African Journal of Business Management, 10(5), 98–108. doi:10.5897/AJBM2015.7978

- Bundy, C. (1988). The rise and fall of the South African peasantry (2nd ed., pp. 276). Cape Town, South Africa: David Philip.

- Bwalya, R. (2014). An analysis of the value chain for indigenous chickens in Zambia’s Lusaka and Central Provinces. Journal of Agricultural Studies, 2(2), 32–51. doi:10.5296/jas.v2i2.5918

- Chadha, M. L., Oluoch, M. O., Saka, A. R., Mtukuso, A. P., & Daudi, A. T. (Eds). (2003). Vegetable research and development in Malawi. Review and Planning Workshop Proceedings, September 23–24, 2003. Lilongwe, Malawi: AVRDC-The World Vegetable Center, Shanhua, Taiwan. AVRDC Publication No. 08-705, 116.

- Chagomoka, T., Afari-Sefa, V., & Pitoro, R. (2014). Value chain analysis of indigenous vegetables from Malawi and Mozambique. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 17(4), 59–86.

- Chitundu, M., Droppelmann, K., & Haggblade, S. (2009). Intervening in value chains: Lessons for Zambia’s task force on acceleration of cassava utilisation. Journal of Development Studies, 45(4), 593–620. doi:10.1080/00220380802582320

- Chweya, J. A., & Eyzaguirre, P. B. (1999). The biodiversity of traditional leafy vegetables. Rome: International Plant Genetics Resources Institute.

- Department of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (DAFF). (2012). The new age business briefing. Pretoria, South Africa: DAFF.

- Emire, S. A., & Arega, M. (2012). Value added product development and quality characterization of amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus L.) grown in East Africa. African Journal of Food Science and Technology, 3(6), 129–141.

- Faber, M., Oelofse, A., Van Jaarsveld, P. J., Wenhold, F. A. M., & Jansen Van Rensburg, W. (2010). African leafy vegetables consumed by households in the Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal Provinces in South Africa. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 23(1), 30–38. doi:10.1080/16070658.2010.11734255

- Fox, F. W., & Norwood-Young, M. E. (1982). Food from the veld: Edible wild plants of Southern Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa: Delta Books.

- Goodman, L. (1961). Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32, 245–268. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177705148

- He, H. P., & Corke, H. (2003). Oil and squalene in amaranthus grain and leaf. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 51(27), 7913–7920. doi:10.1021/jf030489q

- Husselman, M., & Sizane, N. (2006). Imifino: A guide to the use of wild leafy vegetables in the eastern cape. ISER monograph two. Grahamstown, South Africa: Institute for Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University.

- Jansen Van Rensburg, W. S., Van Averbeke, W., Slabbert, R., Faber, M., Van Jaarsveld, P., Van Heerden, I., Wenhold, F., & Oelofse, A. (2007). African leafy vegetables in South Africa. Water SA, 33, 317–326.

- Jansen Van Rensburg, W. S., Venter, S. L., Netshiluvhi, T. R., Van Den Heever, E., Vorster, H. J., De Ronde, J. A., & Bornman, C. H. (2004). The role of indigenous leafy vegetables in combating hunger and malnutrition. South African Journal of Botany, 70(1), 52–59. doi:10.1016/S0254-6299(15)30268-4

- Jones, M., Hoffman, L. C., & Muller, M. (2015). Effect of rooibos extract (Aspalathus linearis) on lipid oxidation over time and the sensory analysis of blesbok (Damaliscus pygargus phillipsi) and springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) droëwors. Meat Science, 103, 54–60. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.12.012

- Joubert, E., & De Beer, D. (2011). Rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) beyond the farm gate: From herbal tea to potential phytopharmaceutical. South African Journal of Botany, 77, 869–886. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2011.07.004

- Kaplinsky, R., & Morris, M. (2001). A handbook of value chain analysis. Brighton, UK: Prepared for the IDRC, Institute for Development Studies.

- Lenné, J. M., & Ward, A. F. (2010). Improving the efficiency of domestic vegetable marketing systems in East Africa constraints and opportunities. Outlook on Agriculture, 39(1), 31–40. doi:10.5367/000000010791169952

- Lyatuu, E., Msuta, G., Sakala, S., Marope, M., Safi, K., & Lebotse, L. (2009). Marketing of indigenous leafy vegetables and how small scale farmers’ income can be improved in SADC region (Tanzania, Zambia and Botswana). Marketing Information. Project under SADC-ICART Project –2009.

- Mabuza, M. L., Ortmann, G. F., & Wale, E. (2014). Socio-economic and institutional factors constraining participation of Swaziland’s mushroom producers in mainstream markets: An application of the value chain approach. Agrekon, 52(4), 89–112. doi:10.1080/03031853.2013.847037

- Machethe, C. L., Mollel, N. M., Ayisi, K., Mashatola, M. B., Anim, F. D. K., & Vanasche, F. (2004). Smallholder irrigation and agricultural development in the Olifants River Basin of Limpopo Province: Management transfer, productivity, profitability and food security issues. Report to the Water Research Commission on the Project “Sustainable Local Management of Smaller Irrigation in the Olifants River Basin of Limpopo Province”. Pretoria: Water Research Commission.

- Maunder, E. M. W., & Meaker, J. L. (2007). The current and potential contribution of home-grown vegetables to diets in South Africa. Water SA, 33, 401–406.

- Modi, M., Modi, A., & Hendriks, S. (2006). Potential role for wild vegetables in household food security: A preliminary case study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 6(1), 1–13. doi:10.4314/ajfand.v6i1.19167

- Nenguwo, N. (2004, May). Review of vegetable production and marketing (supply chain analysis) increasing the value and quality assurance for the fresh vegetables and herbs supply chain to Sun International Hotels in Zambia. Technical Report Submitted to Regional Center for Southern Africa. Botswana: U.S. Agency for International Development Gaborone.

- Nesamvuni, A. E., Oni, S. A., Odhiambo, J. J. O., & Nthakheni, N. D. (2003). Agriculture as the cornerstone of the economy of the Limpopo Province. Thohoyandou: A study commissioned by the Economic cluster of the Limpopo Provincial Government under the Leadership of the Department of Agriculture. University of Venda for Science and Technology.

- Nesamvuni, C., Steyn, N. P., & Potgieter, M. J. (2001). Nutritional value of wild, leafy vegetables consumed by the Vhavhenda. South African Journal of Science, 97, 51–54.

- Neugart, S., Baldermann, S., Ngwene, B., Wesonga, J., & Schreiner, M. (2017). Indigenous leafy vegetables of Eastern Africa: A source of extraordinary secondary plant metabolites. Food Research International, 100, 411–422. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2017.02.014

- Ngugi, I. K., Gitau, R., & Nyoro, J. K. (2007). Access to high value markets by smallholder farmers of African indigenous vegetables in Kenya. London: IIED.

- Njume, C., Goduka, N. I., & George, G. (2014). Indigenous leafy vegetables (Imifino, morogo, muhuro) in South Africa: A rich and unexplored source of nutrients and antioxidants. African Journal of Biotechnology, 13(19), 1933–1942. doi:10.5897/AJB

- Nonnecke, I. I. (1989). Vegetables production. New York, USA: Van Nostrand Reinhold Library of Congress.

- Odhav, B., Beekrum, S., Akula, U., & Baijnath, H. (2007). Preliminary assessment of nutritional value of traditional leafy vegetables in KwaZulu-Natal. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 20, 430–435. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2006.04.015

- Onyemauwa, C. S. (2010). Marketing margin and efficiency of watermelon marketing in Niger Delta area of Nigeria. Agricultural Tropical Et Sub-Tropical, 43, 196–201.

- Osano, J. S. (2010). Market chain analysis of African indigenous vegetables (AIVs) in Tanzania: a case study of African eggplant (solanum aethiopicum) in Kahama district ( Masters’ thesis). Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania. Retrieved from http://www.suaire.suanet.ac.tz

- Padulosi, S., Thompson, J., & Rudebjer, P. (2013). Fighting poverty, hunger and malnutrition with neglected and underutilized species (NUS): Needs, challenges and the way forward. Rome: Bioversity International.

- Parsons, N. (1993). A new history of Southern Africa (2nd ed.). London: Mac-Millan.

- Peires, J. B. (1981). The house of Phalo: A history of the Xhosa people in the days of their independence. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- PEPPADEW. (n.d.) Discover the magic behind the peppadew® brand. Retrieved from https://www.peppadew.com/

- PROTA. (2004). Plant resources of tropical Africa 2: Vegetables. (G. D. H. Grubben & O. A. Denton, Eds.). Wageningen, Netherlands: Author.

- Pudasaini, R., Sthapit, S., Suwal, R., & Sthapit, B. (2013). Case study 2: The role of integrated home gardens and local, neglected and underutilized plant species in food security in Nepal and meeting the Millennium Development Goal 1 (MDG): In diversifying food and diets: Using agricultural biodiversity to improve nutrition and health. (J. Fanzo, D. Hunter, T. Borelli, & F. Mattei, Eds.). London: Earthscan.

- Quaye, W., & Kanda, I. J. (2004). Bambara marketing margins analysis. Accra, Ghana: Food Research Institute.

- Saunders, R. M., & Becker, R. (1984). Amaranthus: A potential food and feed resources. Advances in Cereal Science Technology, 5. st Paul, MN: American Association of Cereal Chemists.

- Shackleton, C., Pasquini, M., & Drescher, A. (Eds.). (2010). African indigenous vegetables in urban agriculture (pp. 298). London: Earthscan.

- Tiedtke, J., & Marks, O. (2002). Rooibos: The new “white tea” for hair and skin care. Euro Cosmetics, 6(16), 19.

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). (2009). Agro-value chain analysis and development: The UNIDO approach (A staff working paper). Vienna.

- Uys, G. (2017, August 15). Success with sweet piquanté peppers. Farmers’s Weekly, 7, 42. am, South Africa.

- Van Jaarsveld, P., Faber, M., Van Heerden, I., Wenhold, F., Jansen Van Rensburg, W. S., & Van Averbeke, W. (2014). Nutrient content of eight African leafy vegetables and their potential contribution to dietary reference intakes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 33(1), 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2013.11.003

- Vorster, I. H. J., Stevens, J. B., & Steyn, G. J. (2008). Production systems of traditional leafy vegetables: Challenges for research and extension. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 37, 85–96.

- Weinberger, K., Pasquini, M., Kasambula, P., & Abukutsa-Onyango, M. (2011). Supply chains for indigenous vegetables in urban and peri-urban areas of Uganda and Kenya: A gendered perspective. In D. Mithoefer & H. Waibel (Eds.), Vegetable production and marketing in Africa socio-economic research (pp. 288). Oxfordshire: CABI International.

- Will, M. (2008). Promoting value chains of neglected and underutilized species for pro-poor growth and biodiversity conservation. guidelines and good practices. Rome, Italy: Global Facilitation Unit for Underutilized Species.