?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examined the associations between satisfaction, commitment and repurchase intention of branded products from the perspective of customers in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. The study employed the Social exchange theory as its theoretical underpinning. Data was collected through purposive and convenient sampling techniques of 268 users of branded products from the Province. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) statistical technique with Smart PLS version 3.0 was used to analyse the data. The results identified normative commitment as an important driver of satisfaction. It was also observed that, calculative commitment had a greater influence on customer repurchase intention. The results have implications for relationship managers, brand managers and scholars who use service evaluation and interactive commitment as a multidimensional construct in predicting customer repurchase intention.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper looked into the associations between satisfaction, commitment and repurchase intention of branded products in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. Branding has become a very important issue for business success. Consumers buy brands. It is therefore important for both academic and business to understand some of the variables that make consumers loyal to a brand. Data was collected through purposive and convenient sampling techniques of 268 users of branded products. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with Smart PLS version 3.0 was used to analyse the data. The results identified normative commitment as an important driver of satisfaction. It was also observed that, calculative commitment had a greater influence on customer repurchase intention. The results have implications for academic, practice and policy.

1. Introduction

Customers have been searching for different, distinctive and outstanding relationships with brands over the past years (Reydet & Carsana, Citation2017). Satisfaction is one of the prevalent constructs, that has extensively been explored by academicians and researchers for its impact on repurchase intention from the perspective of consumer behavior (Chiu, Fang, Cheng, & Yen, Citation2013; Kim, Citation2012). According to Saufiyudin, Fadzil, and Ahmadc (Citation2016), customer satisfaction is seen as influencing repurchase intentions on behavior—which leads to improvement in organisations’ proceeds and earnings. Outstanding positive experience leads to affirmative behaviours in companies’ and firms’ activities—making customers loyal to organisations’ products and services (Straker, Wrigley, & Rosemann, Citation2015). The escalating competition in the retail industry demands that, managers of businesses ascertain factors reinforcing customers’ commitment towards brands (Shukla, Banerjee & Singh, Citation2016). Customer’s valuation of service excellence is a vital information needed for service providers to improve in their business performance while positioning themselves tactically in the market place (Cronin & Taylor, Citation1992; Jain & Gupta, Citation2004). Organisations always expect their customers to be devoted to their brands with strong feelings. Espejel et al observed that, the higher the level of satisfaction, the more committed customers become.

According to Kotler and Armstrong (Citation2004), branding is a significant means which helps in forming a positive image on consumers from other competing products. The propagation of different brands, characterised with its resultant opportunities for customers to adjust their preference rather than to be committed; has become an enigma to marketers about the subject of commitment on brands (Shukla et al., Citation2016). A greater number of researchers perceived satisfaction from a general perspective, although it ought to be measured distinctly from transaction based and experience-based satisfaction (Huang & Dubinsky, Citation2014). Industrial intelligences are recognising the developing portent of changing commitment levels among customers (Euromonitor, Citation2014). According to Shukla et al. (Citation2016), there is limited academic research on customer commitment in the luxury sector. Researchers, such as Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994), Bansal, Irving, and Taylor (Citation2004) all opined that the foremost stream of research works on consumers identify commitment as a crucial component in developing and maintaining continuing relationships is limited (Bansal et al., Citation2004; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994).

Nevertheless, many studies positioned commitment as a unidimensional variable or construct in relationship marketing studies, which, according to Amofa and Ansah (Citation2017), has a greater effect on the degree of deviation on its findings other than measuring it from the multidimensional perspective—as employed in the current study; with succeeding research works using “commitment” as a multidimensional construct (Bansal et al., Citation2004; Eisingerich & Rubera, Citation2010). The three component structure of commitment propounded by Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) in the purview of organisational science provided an appropriate platform for investigating the emotional (affective), functional (calculative) and social (normative) phases—reflecting a valid level of measuring commitment on brands. Also, it has been observed that, research on the factors that influence consumer repurchase is limited (Milner & Rosenstreich, Citation2013).

Despite several studies on satisfaction, only a small number had examined the associations between satisfaction, commitment as a multidimensional construct, as well as repurchase intention in same study. This study attempts to bridge the gap by developing and testing a model of relationship behavior—aiming at clarifying the relationships among customer satisfaction, affective commitment, normative commitment and calculative commitment all on repurchase intentions. Therefore, the main purpose of the study is to examine the effects of customer satisfaction on commitment and repurchase intention of branded products.

This paper presents the proposed models based on a number of hypothesised relationships derived from an extensive literature review. The models are then tested in an empirical study. As a final point, the paper concludes with a discussion of the findings, implications, limitations, and potential future research directions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social exchange theory

Social exchange is explained as an intentional actions of individuals that are driven by the returns they are anticipated from other parties (Blau, Citation1964). The central basis of the theory is that people involved in interactions willingly offer benefits, beseeching responsibility from the other party to reciprocate and provide some benefit in return (Yoon & Lawler, Citation2005). The countered benefits can take a form of monetary rewards or social benefits. The underlying principle of social exchange theory validates a reciprocated backings, which is created by collective bonds among exchange actors (Konovsky & Pugh, Citation1994). According to Thye, Yoon, and Lawler (Citation2002), social exchanges creates feelings of personal obligation, appreciation, and trust among partners.

In relating the social exchange theory to the current study, this study succumbs to an exertion that, the more consumers or customers experience a greater return from their respective branded products—regarding satisfaction, the more they are likely to be committed to the products. In addition, as a result of this apparent fair treatment enshrined as part of the features of social exchange theory, committed consumers or customers are more likely to embark on a repurchase intention. For that reason, the higher the satisfaction level of customers, the more they are probable to be committed that will eventually lead to repurchase intension.

2.2. Customer satisfaction

Satisfaction is what a product or service provides through a delightful level of consumption-related realisation (Zeithaml & Bitner, Citation2003). According to Kim (Citation2012), satisfaction is perceived as an assertiveness, that results from a psychological comparison of the service and quality that a customer or a consumer assumes to receive from a transaction after purchase. Customer satisfaction labels an anticipated result of service that involves an assessment of whether the service has met the customer’s wishes and anticipations (Orel & Kara, Citation2014). According to Thaichon and Quach (Citation2015), customer satisfaction is defined as customers’ feelings of pleasure, fulfillment and desire towards a service rendered. Satisfaction is also viewed as a result of the customer’s post-purchase valuations of both tangible and intangible brand attributes (Krystallis & Chrysochou, Citation2014). The current study employed the definition by Thaichon and Quach (Citation2015), who defined customer satisfaction as customers’ feelings of pleasure, fulfillment and desire towards a service provider or a service rendered.

2.3. Affective commitment

Affective commitment is defined as the passionate connection with the brand that represents strong logic of personal identifications. According to Pring, affective brand commitment relies on identification and mutual value with the brand. Consumers with greater brand commitment would have stronger affective attachment towards the brand (Keh et al., Citation2007). Mcalexander, Schouten, and Koenig (Citation2002) opined that affective commitment describes the deep attachment to a dedicated brands. Allen and Meyer (Citation1990: 253) observed that affective commitment was an emotional attachment to an organization. Bansal et al. (Citation2004: 236) revealed that affective commitment becomes more apparent when a customer or a consumer is glued emotionally to a company or a product—just because they are genuinely committed to it.

2.4. Normative commitment

Normative commitment is intellectualised as a responsibility towards the organization (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990). Normative commitment is well-defined as a form of association that relies on idiosyncratic norms recognised over time, where customers or consumers envisage that, they ought to stay with the company (Bansal et al., Citation2004). According to Shukla (Citation2011, Citation2012)), normative norm is moulded by the perception of the customer—which is influenced by the social environment. Customers are influenced by their social environment and act in such a way to gratify their peers or group, so as to associate themselves significantly with the brand.

2.5. Calculative commitment

Calculative commitment is seen as the functional link customers tend to have with products and organisations. Calculative commitment is applied comprehensively in business and consumer research to examine a variety of issues, such as the backgrounds of brand loyalty (Li & Petrick, Citation2008). It relates to the sentiment of having to stay with a company or an organisation, either due to less attractive alternatives or no alternatives (Bansal et al., Citation2004). Gilliland and Bello (Citation2002: 28) observed that calculative commitment was a state of attachment to a partner or cognitively experienced as a realization of the benefits that would be sacrificed and the losses that would be incurred if the relationship were to end. Allen and Meyer (Citation1990) defined the concept as a restriction based relationship that is formed due to the switching cost an employee has to face, if they were to leave the firm.

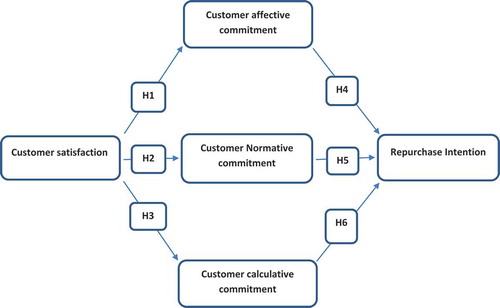

In concluding this section, Figure below depicts the conceptual model to be tested in this study.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1. Customer satisfaction and commitment

The effects of customer satisfaction on brands’ commitment have been examined by numerous authors ( Darsono & Junaedi, Citation2006). The moment customers become satisfy with their total experience, they are more liable to be committed and ensured a continued relationship (Beatson, Cotte, & Rudd, Citation2006). Once customers become satisfied, they show commitment to constantly buy same brand of product (Ballantyne & Warren, Citation2006). Preceding studies have reported positive influence of satisfaction on relationship length (Seiders, Voss, Grewal, & Godfrey, Citation2005; Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, Citation1996). Customers tend to associate themselves to a product; once they have feelings of obligation towards the company or the product (Einwiller, Fedorikhin, Johnson, & Kamins, Citation2006). According to Garbarino and Johnson (Citation1999), as well as Camarero and Garrido (Citation2011), who opined that consumers’ overall assessment of satisfaction with their consumption experiences offer a positive effect on commitment. According to Chien-Lung, Chia-Chang, and Yuan-Duen (Citation2010); Belanche, Casaló, and Guinalíu (Citation2013), customer satisfaction is highly correlated with commitment. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1:

There is a significant positive relationship between customer satisfaction and customer affective commitment on branded products

H2:

There is a significant positive relationship between customer satisfaction and customer normative commitment on branded products

H3:

There is a significant positive relationship between customer satisfaction and customer calculative commitment on branded products

3.2. Customer commitment and repurchase intention

Commitment as a concept has been defined as “an implicit or explicit pledge of relational continuity between exchange partners” (Dwyer, Schurr, & Oh, Citation1987, p. 19) or as “psychological attachment” to an organization (Gruen, Summers, & Acito, Citation2000, p. 37). Garbarino and Johnson (Citation1999); Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner, and Gremler (Citation2002) defined customer commitment as an exchange people tend to sustain towards a continued relationship with another. Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) observed that commitment encourages buyers and suppliers to continue their association with brands. Commitment contributes to successful relationships because, it leads to cooperative behaviors (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). The strength of commitment are positive (Bansal et al., Citation2004; Fullerton, Citation2003; Gruen et al., Citation2000; Harrison-Walker, Citation2001). A study by Verhoef (Citation2003) in the banking services observed a direct result of commitment on repurchase intention. Harrison-Walker also observed a positive relationship between commitment and branded products. It then showed that commitment has an effect on repurchase intentions.

Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4:

There is a significant positive relationship between customer affective commitment and customer repurchase intention on branded products

H5:

There is a significant positive relationship between customer normative commitment and customer repurchase intention on branded products

H6:

There is a significant positive relationship between customer calculative commitment and customer repurchase intention on branded products.

4. Method

This sections outlined the details of the research methodology that comprised measurement of the instrument, sampling, data collection, as well as the testing of hypotheses.

4.1. Population and sample

The respondents for the study included customers and consumers of branded products from the Gauteng province of South Africa. The respondents consisted of government employees, private sectors employees, self-employed, the unemployed and students in the Gauteng province. A total of 268 useable questionnaires were used, out of the 300 questionnaires that were distributed—representing 89%. The sample was deemed fit for the analysis using Roscoe (Citation1975) calculator on sample sizes, which suggested that, sample sizes ought to be more than 300 and less than 500 applicable for an utmost research.

4.2. Pre testing of the instrument

The original version of the research instrument was pre-tested with 15 participants, who were sampled from Braamfontein, Rosebank and Campus Square—all in the Gauteng Province. Each participant was presented with a copy of the questionnaire through four trained research assistants—who were trained towards the distribution and the collection of the questionnaires. Participants were asked to provide their opinion and comments on the clarity of the instructions; the wording of the questions; the layout of the questionnaire, as well as the time taken in completing them. Corrections were then made—regarding the feedbacks, which were factored into the final questionnaires towards the actual analysis.

4.3. Data collection procedure

Convenience sampling and purposive sampling techniques were used to collect the data from the respondents—who were basically interested in the usage of branded products. The collection lasted for a month and two weeks—before the required sample size was received. The participants were made to fulfil certain requirements before answering the questions. First, participants were supposed to be users of branded products. Second, they were to be residents at the Gauteng Province. After that clarification, questionnaires were then distributed to the respondents by the research assistants in offices, locations and institutions—which were all in the province. The basis of the research work was first explained by the research assistants without any compulsion on participants’ part to either accept to take part in the study or to ignore answering the questionnaires—after which questionnaires were handed to them to complete. Those who were willing to take part in the exercise but were not comfortable in filling the questionnaires on their own were assisted by the research assistant until the required sample was obtained for the actual analysis.

4.4. Measurement and questionnaire design

The research constructs were developed solely on already validated measures. All scale items were rearticulated to relate exactly to the context of the current study’s requirement. A five point Likert scale was employed to measure the constructs ranging from “1-strongly disagree” to “5-strongly agree”. Satisfaction used a four—item scale which was adapted from Oliver (Citation1997); Repurchase intention used a four—item scale which was also adapted from Yi and La (Citation2004); affective commitment, normative commitment, as well as calculative commitment all employed six—item scale each—which were adapted from Lee, Allen, Meyer and Rhee (Citation2001). In line with the commendation by Nunnally (Citation1978), a minimum of three items were used per construct so as to guarantee suitable reliability.

The questionnaire was divided into three parts; Part A contained the introductory summary of the entire questionnaire to the participants; Part B contained demographic profile with gender, age, marital status, level of education, as well as the occupation of the respondents, while Part C contained questions about the variables that were used in the study—namely: satisfaction, commitment and repurchase intention using a five point Likert scale that was anchored from “1-strongly disagree” to “5-strongly agree”.

4.5. Data analysis

The research structure of analysis used in the study was developed by Partial least square (PLS) model using Smart PLS 3.0 software. The software was used in assessing the measurement and structural model (Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, Citation2009). First, it determined the relationship of the constructs Second, it identified the effects of each measuring constructs on the other in the research framework. It also estimated the statistical significance of factor loadings and the path coefficients (Chin, Citation2001; Davison, Hinkley, Young, Citation2003) using non-parametric bootstrap technique.

4.6. Reliability assessment

The reliability of the study was measured using Cronbach alpha and composite reliability (CR). The Cronbach’s alpha (α) of all constructs were greater than 0.70, and the CR values were greater than 0.80, indicating adequate internal consistency of the constructs (Hair et al. Citation2010). In the current study, the values for Cronbach alpha ranged from 0.735 to 0.876 while that of the CR values ranged from 0.829 to 0.939, indicating a high internal consistency as shown in Table .

Table 1. Accuracy statistics

4.7. Convergent validity

Convergent validity simply explicates the extent at which multiple items measuring the same concept are in agreement. Babin and Zikmund (Citation2016:283) observed that convergent validity depends on internal consistency—where multiple measures converge on dependable basis. Hair et al. (Citation2010) observed that, for convergent validity to be evident in a study, the loadings for all items ought to be greater than 0.50. In the current study, the CR and the AVE values all exceeded the recommended value. Therefore, the overall measurement model of the study established satisfactory convergent validity as shown in Table .

4.8. Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity signifies how unique or distinct a measure is, a scale should not correlate too highly with a measure of a different construct (Babin & Zikmund, Citation2016:283). The study employed Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) assessment in determining the discriminant validity.

Table presents the discriminant validity such that, the value of square root of AVE exceeded the construct correlations with all other constructs.

Table 2. Discriminant validity

As recommended by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), discriminant validity is assessed by examining the AVE and squared correlations between the constructs. As illustrated in Table , all constructs met the discriminant validity as the AVE for each construct was higher than the squared correlation with the other constructs.

4.9. Goodness of fit

The study’s goodness of fit statistics (GOF) was calculated using a formula by Tenenhaus, Vinzi, Chatelin, and Laura (Citation2005), where the averages of the average variance extracted (AVE) was first multiplied by the averages of the R2 values, after which the multiplied value or the result was squared to determine the model fit.

GoF = √ AVE * R2

= √ 0.638 * 0.435

= √ 0.278

= 0.527

The calculated GoF was 0.527, which exceeded the threshold of GoF > 0.36 recommended by Wetzels, Odekerken-Schroder, and Van Oppen (Citation2009). Thus, the study therefore concluded that, the research model had a better overall fit.

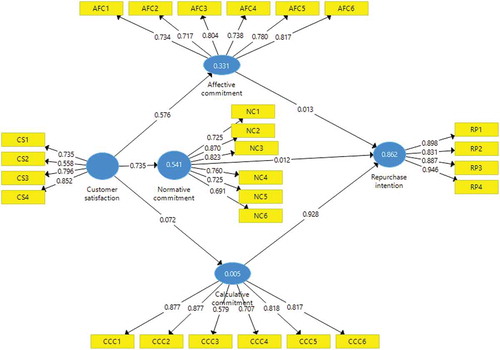

5. Presentation of hypothesised results

The hypothesised relationships between the constructs were analysed using Smart PLS 3.0 software. Path analysis and levels of significance were used in assessing the hypothesised associations of the study. Bootstrapping strategy was used to validate the results of the hypotheses, with 300 bootstrap samples selected for a one-tailed test—which relied on critical t statistical values of 1.65 (significance level 5%) and 2.33 (significance level 1%) (Hair et al., Citation2010). R2 value of 0.862 for repurchase intention designated that, 86.2% of the variance was explained by the affective, normative and calculative commitment. The R2 value of 0.541 for normative commitment revealed that 54.1% of the variance was described by the satisfaction level of the respondents. “Affective commitment” as a variable exhibited an R2 value of 0.331 which was explained by satisfaction while calculative commitment as a variable recorded the least value of R2 with 0.005, which was explained by satisfaction level.

The hypothesised relationships of the study presented in Figure and Table showed that, hypothesis statement—H6; calculative commitment on repurchase intention was positive and highly significant with path coefficient value, t-statistics value and probability value respectively as (β = 0.928, µ = 12.210, α = 0.000 < 0.01); which was followed by H2 on satisfaction and normative commitment with (β = 0.735, µ = 11.377, α = 0.000 < 0.01); H1, satisfaction and affective commitment (β = 0.576, µ = 7.053, α = 0.00 < 0.01).

Table 3. Results of the Structural Equation Model analysis

However, H3, H4 and H5 did not support their respective hypotheses. H3 which was satisfaction on calculative commitment recorded a positive relationship but was not significant thereby rejecting the stated hypothesis with values (β = 0.072, µ = 0.561, α = 0.575 > 0.05, 0.01). It was then followed with H4, connecting—affective commitment and repurchase intention, which also was positive and insignificant with values: (β = 0.013, µ = 0.272, α = 0.786 > 0.05, 0.01) while H5 with normative commitment and repurchase intention recorded the least with (β = 0.012, µ = 0.197, α = 0.844 > 0.05, 0.01).

6. Discussion of results

The study examined the influence of satisfaction on commitment and repurchase intention of branded products in Gauteng province of South Africa. Six hypotheses were outlined for the test analysis. First, it was evident from the study that, satisfaction had a greater influence on the normative commitment of customers towards branded products than affective and calculative commitment levels. The findings of the study were in consistent with Ballantyne and Warren (Citation2006); Camarero and Garrido (Citation2011) who opined that consumers’ complete valuation of satisfaction with their consumption practices provide a positive consequence on commitment. It demonstrated that once customers are satisfied with the attributes of a particular branded product, they are more likely to be committed to the said products. In addition, the study findings also made it apparent that, commitment has greater effects on repurchase intention. The result of the study are in consonance with Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994), who revealed that commitment has strong effect on buyers and suppliers in continuing their association with brands. In the current study, calculative commitment, recorded a greater value on repurchase intention than affect and normative commitment. That is to say that, customers are highly glued towards their intention in repurchasing; once there is a cost associated with a switch from a particular brand to another brand. The study findings are in consistent with Bansal et al. (Citation2004), who opined that the sentiment of having to stay with the company or an organisation, either due to less attractive alternatives or no alternatives has more likely to restrict a consumer or a customer from alternating or changing a brand. The findings are also in line with Gilliland and Bello (Citation2002: 28), who observed that calculative commitment was a state of attachment to a partner or cognitively experienced as an awareness of the benefits that would be sacrificed and the losses that would be incurred if the relationship were to end. Finally, the findings were also in consistent with the theory of Social exchange. According to Blau (Citation1964), social exchange theory is expounded as a deliberate actions of individuals that are driven by the returns they are anticipated between two parties. In the current study, there seemed to be a strong relationship between satisfaction and commitment—such that the more customers are satisfied with a particular branded products, the more they become committed to the said brands. Again, it was evident that, there was a positive relationship between commitment and repurchase intention of branded products. The more customers become committed towards a brand; the more their intents towards the purchase of the products become very high.

7. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of satisfaction on commitment levels and repurchase intention of customers and consumer—who are attached to branded products in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. The study revealed that, there was a relationship between satisfaction and commitment. The more customers of branded products are satisfied, the more they tend to be loyal to the brands in question. Within the same context, it was also observed that, satisfaction is moulded by the perception of the customer—which relied on the social environment for one to be committed other than the exorbitant price and feelings customers employ towards branded products. It is the society that tend to influence customers towards the usage of a particular brand. The study also concludes that calculative commitment has a greater influence on customer intention to purchase. The cost associated with a switch from one brand to the other compels customers towards their intent on future purchase of the same branded product. The findings of the current study do not only provide significant insights to practitioners, but also contribute to the literature on relationship marketing from the viewpoint of emerging economies.

7.1. Theoretical implication

This study offers valuable insights regarding the measurement of cognitive and affective dimensions of consumer—brand relationships on commitment. The results of the study have a number of important implications for both theory and practice as recommended by Shukla et al. (Citation2016) and Amofa and Ansah (Citation2017) on the application of a multidimensional construct in bringing out an extent of differences from a construct or a variable other than a unidimensional measurement.

7.2. Managerial implications

The findings have imperative implications for practitioners; principally those in the wholesale and retail business, such as distributors of branded products. First and foremost, by empirically testing the vital drivers of customer satisfaction on commitment and repurchase intention, this research seeks to offer managers of branded organisations with strategic activities that is likely to motivate both behavioral and attitudinal commitment. The need to intensity communication activities on brands through comparative advertising towards the influence of the climate of opinions in societies on branded products—other than over reliance on the image of the brand. Consequently, the findings of the study seek to enlighten managers’ regarding what factors to prioritize in generating higher levels of commitment and purchase, hereafter helping them to advantageously situate their customer retaining investments.

7.3. Limitation and future research directions of the study

This study contributes immensely to theory and practice. However, it has some limitations. First, the application of non—probability sampling techniques in the study limit the generalisability of its findings. In addition, the current study was limited to Gauteng province in South Africa without including other provinces. For results comparison, subsequent researchers ought to consider replicating this study in other South African provinces and other developing countries. Finally, the study did not consider how customer commitment may vary with regards to established versus new branded products. While this research explicitly focused on customers who use and intent to use branded products, an imperative area for future studies is to investigate how commitment towards branded products compares with non-branded products. Future studies should also investigate other probable antecedents to commitment, such as scarcity, positive and negative emotions associated with a brand, beside with prior brand familiarity.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their prolific insights and recommendations.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Phineas Mbango

Dr Phineas Mbango is a senior lecture at the University of South Africa. He has been in the academic field for more than 15 years. He specializes in relationship marketing and has written many academic papers on this subject. Before joining the academia, he worked in the corporate in various positions in Sales and Marketing, as well as in Human Resources Management.

References

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

- Amofa, D. O., & Ansah, M. O. (2017). Analysis of organisational culture on component conceptualisation of organisational commitment in Ghana’s banking industry. Business and Social Science Journal, 2, 1–26.

- Babin, B., & Zikmund, W. (2016). Essentials of marketing research 6th edition. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Ballantyne, R., & Warren, A. (2006). The evolution of brand choice. Journal of Brand Management, 13, 339–352. doi:10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540276

- Bansal, H., Irving, G., & Taylor, S. (2004). A three-component model of customer commitment to service providers. Journal Academic Mark Sc, 32(3), 234–250.

- Beatson, A., Cotte, L. V., & Rudd, J. M. (2006). Determining consumer satisfaction and commitment through self-service technology and personal service usage. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(7), 853–882.

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Guinalíu, M. (2013). The Role of Consumer Happiness in Relationship Marketing. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 12, 79–94.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

- Camarero, C., & Garrido, M. J. (2011). Incentives, organizational identification, and relationship quality among members of fine art museums. Journal of Service Management, 22(2), 266–287. doi:10.1108/09564231111124253

- Chien-Lung, H., Chia-Chang, L., & Yuan-Duen, L. (2010). Effect of commitment and trust towards micro-blogs on consumer behavioral intention: A relationship marketing perspective. International Journal Electronic Bus Managed, 8, 292–303.

- Chin, W. W. (2001). PLS-graph user’s guide. CT Bauer College of Business. USA: University of Houston.

- Chiu, C. M., Fang, Y. H., Cheng, H. L., & Yen, C. (2013). On online repurchase intentions: Antecedents and the moderating role of switching cost. Human Systems Manage, 32(4), 283–296.

- Cronin, J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A re-examination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56, 55–67. doi:10.2307/1252296

- Darsono, L. I., & Junaedi, C. M. (2006). An examination of perceived quality, satisfaction and loyalty relationship. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 8(3), 323–342.

- Davison, A. C., Hinkley, D. V., & Young, G. A. (2003). Recent developments in bootstrap methodology. Statistical Science, 18(2), 141–157.

- Dwyer, F. P., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer–Seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27.

- Einwiller, S. A., Fedorikhin, A., Johnson, A. R., & Kamins, M. A. (2006). Enough is enough! When identification no longer prevents negative corporate associations. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 185–194.

- Eisingerich, A. B., & Rubera, G. (2010). Drivers of brand commitment: A cross-national investigation. Journal of International Marketing, 18(2), 64–79. doi:10.1509/jimk.18.2.64

- Euromonitor. (2014). Luxury goods in the Netherlands. London: Author.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal Mark Researcher, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312

- Fullerton, G. (2003). When does commitment leads to loyalty? Journal Services Researcher, 5(4), 333–344. doi:10.1177/1094670503005004005

- Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87. doi:10.2307/1251946

- Gilliland, D. I., & Bello, D. C. (2002). Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 24–43. doi:10.1177/03079450094306

- Gruen, T. W., Summers, J. O., & Acito, F. A. (2000). Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 34–49.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis 7th edition. Upper saddle River, NJ: MacGraw-Hill.

- Harrison-Walker, J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60–75. doi:10.1177/109467050141006

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. ., & Gremler, D. D. (2002). Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230–247. doi:10.1177/1094670502004003006

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advancement International Mark, 20(1), 277–319.

- Huang, W. Y., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2014). Measuring customer pre-purchase satisfaction in a retail setting? Services Industrial Journal, 34(3), 212–229.

- Jain, S. K., & Gupta, G. (2004). Measuring service quality: SERVQUAL vs. SERVPERF scales. Vikalpa, 29(2), 25–37. doi:10.1177/0256090920040203

- Keh, H., Nguyen, T. T. M, & Ng, H. P. (2007). The effects of entrepreneurial orientation and marketing information on the performance of SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing, 22, 592-611.

- Kim, D. J. (2012). An investigation of the effect of online consumer trust on expectation, satisfaction, and post-expectation. Information Systems e-Bus Manage, 10(2), 219–240. doi:10.1007/s10257-010-0136-2

- Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behaviour and social exchange. Academy Management Journal, 37, 656–669.

- Kotler, P., & Armstrong, G. (2004). Principles of marketing (10 th ed ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Krystallis, A., & Chrysochou, P. (2014). The effects of service brand dimensions on brand loyalty. Journal RetailConsumServ, 21(2), 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.07.009

- Lee, K., Allen, N., Meyer, J. P., & Rhee, K.Y. (2001). The three component model of organisational commitment: an application to south korea. Journal of Applied Psychology, 50(4), 45-68.

- Li, X. R., & Petrick, J. F. (2008). Examining the antecedents of brand loyalty from an investment model perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 47(1), 25–34.

- Mcalexander, J., Schouten, J., & Koenig, H. (2002). Building a brand community. Journal of Marketing, 66, 38–54.

- Milner, T., & Rosenstreich, D. (2013). Insights into mature consumers of financial services. Journal Consum Mark, 30(3), 248–257. doi:10.1108/07363761311328919

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment–Trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw- Hill.

- Orel, F. D., & Kara, A. (2014). Supermarket self- check out service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty: Empirical evidence from an emerging market. Journal Retail Consum Services, 21(2), 118–129. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.07.002

- Reydet, S., & Carsana, L. (2017). The effect of digital design in retail banking on customers’ commitment and loyalty: The mediating role of positive affect. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37(2017), 132–138. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.04.003

- Roscoe, J. T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston.

- Saufiyudin, M. O., Fadzil, H. A., & Ahmadc, R. (2016). Service quality, customers’ satisfaction and the moderating effects of gender: A study of arabic restaurants. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 224, 384–392. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.393

- Seiders, K., Voss, G. B., Grewal, D., & Godfrey, A. L. (2005). Do satisfied customers buy more? Examining moderating influences in a retailing context. Journal Mark, 69(4), 26–43.

- Shukla, P. (2011). Impact of interpersonal influences, brand origin and brand image on luxury purchase intentions: Measuring inter functional interactions and a cross national comparison. Journal of World Business, 46(2), 242–252. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2010.11.002

- Shukla, P. (2012). The influence of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions in developed and emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 29(6), 574–596. doi:10.1108/02651331211277955

- Shukla, P., Banerjee, M., & Singh, J. (2016). Customer commitment to luxury brands: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 69, 323–331. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.004

- Straker, K., Wrigley, C., & Rosemann, M. (2015). The role of design in the future of digital channels: Conceptual insights and future research directions. Journal Retail Consum Services, 26, 133–140. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.06.004

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V., Chatelin, Y. M., & Laura, C. (2005). PLS path modelling. Computation Statistical Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205.

- Thaichon, P., & Quach, T. N. (2015). The relationship between service quality, satisfaction, trust, value, commitment and loyalty of internet service providers’ customers. Journal Glob School Mark Sciences, 25(4), 295–313.

- Thye, S., Yoon, J., & Lawler, E. J. (2002). Relational cohesion theory: Review of a research program. Advances in Group Processes, 19, 89–102.

- Verhoef, P. (2003). Understanding the effect of relationship management efforts on customer retention and customer share development. Journal of Marketing, 67, 30–45. doi:10.1509/jmkg.67.4.30.18685

- Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schroder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33(1), 177–195. doi:10.2307/20650284

- Yi, L., & La, S. (2004). What influences the relationship between customer satisfaction and repurchase intention? Investigating the effects of adjusted expectations and customer loyalty. Psychologist Marketing, 21(5), 351–373.

- Yoon, J., & Lawler, E. J. (2005). The relational cohesion model of organizational commitment. In O. Kyriakidou & M. Ozbilgin (Ed.), Relational perspectives in organizational studies: A research companion (pp. 146–162). UK: Edward and Eldar Publishing Limited Chetenham.

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. doi:10.2307/1251929

- Zeithaml, V. A., & Bitner, M. J. (2003). Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm (3rd ed.) ed.). Boston, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Appendix

QUESTIONNAIRE

RESEARCH QUESTIONNAIRE

Please answer the following questions by marking the appropriate answer(s) with an X. This questionnaire is strictly for research purpose only.

SECTION A: GENERAL INFORMATION

The section is asking your background information. Please indicate your answer by ticking (X) on the appropriate box.

A1 Please indicate your gender

A2 Please indicate your marital status

A3 Please indicate your age category

A4 Please indicate your highest academic level

A5 Please indicate your occupation

THE QUESTIONS BELOW ARE ALL BASED ON THE VARIABLES IN THE STUDY

Below are statements about Satisfaction, Commitment, Repurchase intentions, as well as Loyalty. You can indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the statement by ticking the corresponding number in the 5 point scale below:

SECTION B: SATISFACTION

SECTION C: NORMATIVE COMMITMENT

SECTION D: AFFECTIVE COMMITMENT

SECTION E: CALCULATIVE COMMITMENT

SECTION F: REPURCHASE INTENTION

SECTION G: CUSTOMER LOYALTY

Please feel free to provide any comment that could enrich the nature of the study.

Thank you