Abstract

Background: Chile has a very high prevalence of childhood obesity; 25% among 4–5 y olds. Numerous school-based strategies have been implemented with no lasting improvement. Given that parents are key in obesity prevention and that their participation in programs is low, mobile technology is increasingly being used to test its effectiveness in changing children’s behavior. Objective: to report the process of developing text messages for Chilean mothers of low socioeconomic status with overweight or obese preschool children. Methodology: The process involved 3 stages: (a) initial elaboration of 60 messages on healthy eating and physical activity (b) 3 focus groups which included similar participants as the target population and (c) consensus on the final messages obtained from 56 experts, using the Delphi technique. Results: a list of 40 text messages encouraging healthy eating and promotion of physical activity which underwent a rigorous process are ready to be delivered via WhatsApp to low-income mothers of overweight preschool children. Conclusion: this process constitutes the first stage; effectiveness of these messages to produce behavior change on the children has yet to be determined. We suggest that effectiveness be assessed as a tool by itself or supporting strategies already in place system.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In Chile, the rise and present prevalence of childhood obesity are among the highest in the world. Numerous strategies (mainly in schools) have been implemented over the last decades, and although some have shown a positive impact, the effect has only lasted while personnel specially hired for that purpose implemented the activities. Because of the almost universal use of smartphones and WhatsApp, the effectiveness of this tool through the use of text messages addressing healthy diets and promoting physical activity to achieve lifestyle behavior changes is increasingly being tested. In this study, we developed 40 culturally appropriate messages to be delivered to low income mothers with overweight preschool children through a rigorous process. This is the first phase; it remains to be determined if this methodology by itself or as part of a wider intervention has a lasting effect in producing lifestyle behavior changes on the children.

1. Introduction

The obesity epidemic presents a rising prevalence in both developed and developing nations, which has created a global public health problem (Ng et al., Citation2014). Chile is not exempt from this problem, which presented a prevalence of obesity of 24.9% among kindergarten students (ages 4–5) and 24.6% among first graders (ages 6–7) in 2016 (Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas, Citation2017).

In order to address this situation, various interventions have been implemented for the student population in daycare facilities, schools and primary healthcare facilities. These interventions have consisted of providing healthy foods, opening healthy snack kiosks and encouraging physical activity, and they have generally been effective during the intervention itself (Kain B et al., Citation2005). However, they have not managed to stop the increase in childhood obesity, because it is necessary to change the environment, not only in terms of the food that is provided in schools, but also the snacks that children bring from home, meals that are prepared and consumed at home, and physical activity outside of the school. All of these activities require the active participation of the administration, teaching staff, parents and guardians (Bustos, et al., Citation2016, Kain et al., Citation2012). Given how difficult it is to coordinate actions that involve the entire target population in situ, efforts have been made to identify strategies for reaching a large number of people at the same time remotely. In this context, the use of mobile technology or m-Health to change behavior has become popular (Lin et al., Citation2014).

The term electronic health, or m-Health, is defined as a set of computer tools designed to improve public health and healthcare as well as the use of mobile and wireless devices to improve health results (Piette et al., Citation2012).

Interventions involving text messages sent through mobile phones seem to have positive behavioral results in the short term, though there is a need for more in-depth research in this area (Fjeldsoe, Marshall, & Miller, Citation2009).

In view of this, the use of WhatsApp, a mobile application used to send messages, images, videos and voice recordings using only an Internet connection, which has been available for free since 2013 (Giordano et al., Citation2017; Montag et al., Citation2015), is currently an option for the distribution of messages because it is regarded by today’s population as accessible and modern. As there is very little evidence regarding the process of development and drafting of messages aimed at encouraging good health (Diez-Canseco et al. 2015) because the majority of the publications on mobile health focus on program implementation rather than design (Newton et al., Citation2014; Nollen et al., Citation2014; Shapiro et al., Citation2008), we believe that it is important to disseminate this process. Thus, the objective of this article is to report only the process of developing text messages addressing healthy eating and physical activity to be sent via WhatsApp to mothers from medium-low and low socioeconomic levels with overweight and obese children, in order to support lifestyle behavior change of their children.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design

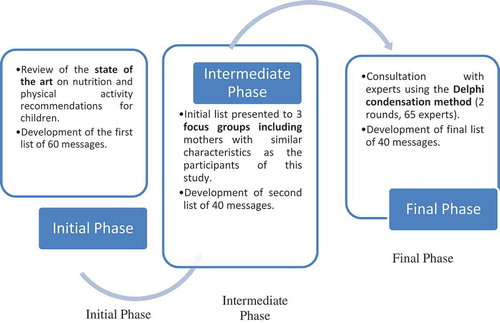

The study involved three phases as outlined in Figure . Each stage is explained below.

2.2. Participants

These 60 messages were presented in three focus groups which included a total of 18 participants. These were held between October 2016 and January 2017. Mothers of children who are overweight or obese who were willing to participate were recruited from schools in the Macul district.

For Delphi, a total of 82 experts in the area of nutrition (n = 60), physical activity (n = 12), education (n = 6) and social matters (n = 4) were contacted and sent an online survey.

2.3. Data collection

2.3.1. Initial phase: development of the first list of messages

The development process began with the drafting of messages oriented towards behavior change. These were based on the Healthy Eating Guides for the Chilean Population (Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnologías de los Alimentos, Citation2013) and the theoretical approach of Prochaska et al. on behavior change (Prochaska & Velicer, Citation1997). All of the messages were oriented towards the family, with a special emphasis on the eating and physical activity habits of boys and girls.

This initial list included 60 messages of varying lengths (35–250 characters), form and content regarding healthy eating (n = 42) and encouraging physical activity (n = 18) directed at the mothers. The healthy eating messages included three types of topics: healthy snacks for their children (n = 12), lunch and snack recipes (n = 12) and general nutritional recommendations (n = 18). All of the topics selected are related to and align with the nutritional recommendations for the national context (Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnologías de los Alimentos, Citation2013).

2.4. Intermediate phase: focus groups

The goal of the focus groups was to determine and describe the perspective of potential users on the content and preliminary structure of the messages, to obtain the consensus of the group about what they understood for “healthy food,” “food habits,” “physical activity” and their opinions on the proposed messages in terms of the content, the values associated and the possibility to put them into practice

In each group, we presented a list of 12–14 messages in order to encourage discussion and thus verify their relevance in relation to the target group, mothers of children who are overweight or obese from two districts of Santiago. The focus groups were directed by an anthropologist from the team and lasted 90 min each. They were conducted following semi-structured guidelines, in which participants were asked about important topics related to nutrition, physical activity, their perception and general aspects of the messages. To open the discussion, each message was rated with a color using “traffic light” logic: green for good, yellow when they’d change something and red when they did not like it at all. Then, each one had to explain their choice. Only the best-rated messages (majority of greens or 50/50 green and yellow) were selected for further modifications according to the suggestions of the participants.

These general topics included questions that allowed them to identify important elements for the distribution of the messages, such as the frequency with which they would like to receive messages about healthy lifestyles, the times of day that it would be best to receive them and the best platform for receiving them (e-mail, SMS, WhatsApp, or another channel).

The results were analyzed using qualitative content analysis and served as an input for improving the messages in function of what the participants suggested both in favor and against each of them, identifying the elements that were important to change in the construction of the second list. While the messages presented were perceived as important in regard to the topics of healthy living, there were adjustments or differences in regard to their length or the type of information provided. Participants preferred messages that were clear in their intent and purpose even if they were longer.

In this sense, the messages that were oriented towards practical elements of nutritional recommendations and physical activity were better received. In other words, in addition to providing information, they presented guidance as to how to carry it out or described exercise routines or easy, quick and healthy recipes. All of these elements were favored in the second list.

One of the main results was that the majority of the mothers identified a broad range of healthy foods based on nutrition guides. This knowledge was derived from their experiences with nutritional treatments, government campaigns and their own research. However, it was clear that this knowledge did not guarantee “healthy” eating because they had to combine this with various limiting factors related to not knowing how to cook or vary the menu or the preferences of those eating, particularly their children. Young people proved reticent about trying certain foods and refused to eat them, so the mothers had to deploy certain strategies to convince them to do so. As one of the participants stated,

For example, they would say, “I don’t like milk. I don’t want to drink milk.” So I would say, “It isn’t milk. It’s cow juice.” If I tell them it is cow juice, they will drink it. But if I say, “No, drink the milk,” they won’t. (FG1)

In regard to physical activity, substantial differences were identified between the activity in which the children engage and the activity in which the family engages. In general, the respondents perceived their children as active and energetic, always ready to move, especially through play. The main space identified for this was the school playground and plazas or parks near their homes, as one of the participants reported:

I feel like they get a lot of exercise. At least, my daughter runs all day long—not a word of a lie, she runs all day long and comes home sweaty (GF2). In general, physical activity for children, understood as sports or engaging in movement with the intention of generating a physical impact, was relegated to school hours and extracurricular activities. One limiting factor was generating a stable space for this that would also involve the entire family.

2.5. Final phase: Delphi technique

The second list (n = 40) was sent out to 82 experts in April 2017 using the Delphi technique; however, only 65 responded (Hasson, Keeney, & Hugh, Citation2000; Yañez Gallardo & Cuadrea Olmos, Citation2008). We selected this technique because it facilitated the participation of a large group of experts on nutrition and physical activity but did not require the coordination of in situ meetings.

Each expert was asked to evaluate a total of 10 messages for clarity and relevance in order to be delivered to mothers of overweight or obese preschool children. They then graded each message on a scale of 1–7 and provided comments in order to improve them. After the first round of evaluation, 30 comments were received from the experts; the lowest score obtained was a 4.5. These were incorporated and the 40 messages were thus modified.

The second evaluation round contained the same questions included in the first questionnaire but with the modified messages. Of the 65 professionals who answered the first time, 56 responded the second time. This number of experts is considered to be methodologically valid, because 10–18 experts are required for each Delphi evaluation, according to the literature (Yañez Gallardo & Cuadrea Olmos, Citation2008).

As approval criterion for both rounds, we established the grade of 5.0 as a passing grade based on the Chilean grading scale (1–7). It is worth mentioning that the lowest grade obtained in the second round was 5.3, which demonstrates an improvement in the perception of the messages and effective inclusion of the suggestions received.

After both rounds of Delphi there are 40 text messages which underwent the rigorous process described above.

2.6. Ethical aspects

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA) at Universidad de Chile. All of the participants signed an informed consent form that listed the conditions of their participations and explained how the data would be used.

3. Results

With respect to the focus groups, the messages drafted initially (n = 60), related to recipes (n = 12) and practical complements for the implementation of food guides (n = 10) received the best evaluations. Participants requested that the program include complementary information on the benefits of certain foods that are easy to access in order to motivate consumption in their families and a simple way to transmit it to their children.

In terms of logistics, the messaging frequency chosen was twice per week. The platform selected was WhatsApp and the time varied depending to a great extent on the daily routine of each participant.

The main results found using the Delphi technique were that most messages were seen as relevant to the issue of healthy living by the entire group, however, similar to the results from the focus groups, there were differences in regard to their length or the type of information provided in the sentence. Sixteen experts preferred messages that were clear in their intention and purpose, such as: “Moving is important for you and your children. Make exercise fun by inviting one of your child’s friends to play so that they can have fun together and strengthen their bodies” and “Did you know that one example of a healthy snack is a piece of fruit, such as an apple, orange, pear, banana or other seasonal fruit?”

In this sense, as we observed in the focus group results, messages oriented towards practical elements of nutrition recommendations (n = 15) and physical activity (n = 9) were evaluated better by this group of experts.

After the expert consensus phase, the messages were modified and a total of 40 were included: 9 on physical activity, 7 on healthy snacks, 16 on healthy eating and 8 recipes published on the “Meal of Your Life” website maintained by the Chilean Ministry of Health. Table offers two examples of the message modification process.

Table 1. Example of modification of 2 messages during the three stages described above

4. Discussion

In the Chilean context, with a very high childhood obesity rate and limited success from large- and small-scale interventions in preventing the rise in this condition (Corvalán et al., Citation2017: Perez-Escamilla et al., Citation2017), results of this study may be important in demonstrating that the use of a technology which is widely available, be considered to determine if it is effective as a single tool or supporting other strategies. Moreover, as participation of parents (mainly mothers) is very low, testing if text messages can help in changing behavior of their children is considered important.

This study shows the process of developing 40 text messages for mothers of overweight preschool children addressing healthy diets and promotion of physical activity.

Two qualitative techniques were used that allowed the most important stakeholders—the target population and experts—to be included in the process. The messages are focused on providing advice with practical examples including recipes. This content coincides with the content found by Woolford and colleagues (Woolford et al., Citation2011) that suggests that recipes should be included in a messaging program as well as ideas and support for families. This makes it easy to follow the nutritional recommendations by showing concrete ways to put them into practice.

The development process included the participation of a group similar to the target group. This practice is recommended, following Sharifi et al, in their 2013 study in Massachusetts, USA, in which parents of children between 6 and 12.9 years who were overweight or obese were invited to participate in a simulation of text messaging for three weeks. Five focus groups were held with a total of 31 parents (28 mothers and 3 fathers). The authors concluded that text messaging is a promising, low-cost medium for supporting behavior change related to childhood obesity (Sharifi et al., Citation2013).

Various studies have shown that messaging is a feasible and acceptable form of communication with children (Shapiro et al., Citation2008). In childhood obesity, there are experiences such as a pilot program based on messages and calls in order to maintain the weight of obese children between the ages of 11 and 18 in Belgium. The five-month experiment showed that regular phone contact played a potential role in maintaining the participants’ weight (Deforche et al., Citation2005).

The evidence has shown that using mobile technology has a tendency to modify certain behaviors, such as increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables and decreasing the intake of sugary beverages in children and adolescents (Nollen et al., Citation2014). A pilot study conducted in the United States with 51 girls between the ages of 9 and 14 sought to test the viability and potential efficacy of an intervention of autonomous mobile technology over the course of 12 weeks. The study focused on three topics: fruits and vegetables, sugary beverages and screen time. Four weeks were assigned to each topic during the intervention. Two groups were formed. One group was given a mobile device that includes the establishment of objectives and the planning that the girls require to set two daily goals and a support plan for improving behavior directed in each module. The control group received manuals with the same content as the mobile devices. The girls who used the mobile technology showed a tendency to increase their consumption of fruits and vegetables and decrease their intake of sugary beverages.

It also has been shown that text messaging can contribute to increasing parent attendance at health check-ups for their children. A study of 101 participants conducted in Durham, United States directed at parents and guardians of children between the ages of five and nine showed that adults who had received text messages attended more check-ups than those who had not (Armstrong et al., Citation2018).

In one of the few published studies, which involved 31 parents and children, the researchers observed greater adherence to self-monitoring of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, physical activity and screen time among participants who received text messages compared to those who received information in paper format. Although the study did not evaluate the real behavior or acceptability and preferences of the participants, it supports the potential of text messages as a tool for monitoring behavior of communication and health (Shapiro et al., Citation2008).

This study represents an innovative exploration of the preferences of parents with regard to text messages and other technologies that can be used to support changes in behavior related to their children’s obesity and presents topics that can guide future interventions. The implementation of interventions that use mobile technologies presents unique opportunities as well as challenges.

The limitations of this development process include low participation in focus groups1 even after confirming with potential participants by phone. We thus suggest using other techniques to increase the likelihood of greater participation, such as offering transportation, setting times that do not conflict with other activities (work, household chores, etc.) or setting up alliances with institutions and activities for which attendance is mandatory (holding the focus group when parents go to pick up their children, before or after meetings of parents and guardians, etc.).

One important strength of our study was that we developed a list of messages through various stages and with different participants. This allowed us to identify messages of interest for individuals in the target group and to work with experts on technical issues related to modifying the messages to meet the health requirements. It is important to pay attention to topical coordination from the perspectives of different stakeholders in the public policy environment due to the need to generate a joint effort to promote healthy lifestyles, providing coherent guidelines for the population.

5. Conclusions

The process described yielded 40 messages focused on encouraging healthy eating and physical activity that were drafted following a rigorous procedure that is supported by the literature. There is still a need to verify the effectiveness of this methodology for achieving changes in behavior among overweight preschool children. We suggest determining effectiveness based on these text messages as a single tool or as a support for strategies already in place.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas, Chilean Ministry of Education for funding this study and also to the participants.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Juliana Kain

We are part of the Public Health Nutrition section of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA) of the University of Chile. Because overweight and obesity affect 50% of Chilean children and 70% of adults, our main goal is to develop effective strategies to prevent this condition. We began in 2001 implementing and evaluating a school-based intervention in a small city called Casablanca. The program, which lasted 3 years, was very effective; however, it was not sustainable. We continued with other interventions in different districts of Santiago with a similar methodology and realized that parents, who are key in supporting their children to acquire healthy habits, do not participate. Considering the almost universal use of smartphones, we developed text messages to be delivered to low income mothers to modify their children´s lifestyle habits. We now need to verify its effectiveness either as a single intervention or supporting others.

References

- Armstrong, S., Mendelsohn, A., Bennett, G., Taveras, E. M., Kimberg, A., & Kemper, A. R. (2018). Texting motivational interviewing: A randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing text messages designed to augment childhood obesity treatment. Childhood Obesity, 14(1), 4–10. Retrieved February 7, 2018, from http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/chi.2017.0089

- Bustos, N., Olivares, S., Leyton, B., Cano, M., & Albala, C. (2016). Impact of a school-based intervention on nutritional education and physical activity in primary public schools in Chile (KIND) programme study protocol: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1217. Retrieved December 10, 2016, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27912741 (August 18, 2017). In Obese Youngsters’. International Journal of Obesity 29 (5):543http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802924 doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3878-z

- Corvalán, C., Garmendia, M. L., Jones-Smith, J., Lutter, C. K., Miranda, J. J., Pedraza, L. S., … Stein, A. D. (2017). Nutrition status of children in Latin America. Obesity Reviews. Suppl, 2, 7–18. doi:10.1111/obr.v18.S2

- Deforche, B, De Bourdeaudhuij, I, Tanghe, A, Debode, P, Hills, A. P, & Bouckaert, J. (2005). Post-treatment phone contact: a weight maintenance strategy in obese youngsters. International Journal Of Obesity, 29(5), 543. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802924.

- Fjeldsoe, B. S., Marshall, A. L., & Miller, Y. D. (2009). Behavior Change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(2), 165–173. Retrieved December 6, 2016, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19135907

- Giordano, V., Koch, H., Godoy-Santos, A., Dias Belangero, W., Esteves Santos Pires, R., & Labronici, P. (2017). WhatsApp messenger as an adjunctive tool for telemedicine: An overview. Interactive Journal of Medical Research, 6(2), e11. doi:10.2196/ijmr.6214

- Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & Hugh, M. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015. April 12, 2017. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x

- Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnologías de los Alimentos. 2013. Ministerio de Salud Aprueba Nuevas Guías Alimentarias | INTA - Instituto de Nutrición Y Tecnología de Los Alimentos. Retrieved December 16, 2017, from https://inta.cl/es/noticia/ministerio-de-salud-aprueba-nuevas-guias-alimentarias

- Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas. (2017). Mapa Nutricionitas JUNAEB 2016 (p. 28). Retrieved July 4, 2017, from http://contrapeso.junaeb.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/mapa_nutricional_2016.pdf

- Kain B, J., Vio D, F., Leyton D, B., Cerda R, R., Olivares C, S., Uauy D, R., & Albala B, C. (2005). Estrategia de Promoción de La Salud En Escolares de Educación Básica Municipalizada de La Comuna de Casablanca, Chile. Revista chilena de nutrición, 32(2), 126–132. doi:10.4067/S0717-75182005000200007

- Kain, J., Uauy, R., Concha, F., Leyton, B., Bustos, N., Salazar, G., … Vio, F. (2012). School-based obesity prevention interventions for Chilean children during the past decades: Lessons learned. Advances in Nutrition: an International Review Journal, 3(4), 616S–621S. August 18, 2017 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22798002

- Lin, P.-H., Wang, Y., Levine, E., Askew, S., Lin, S., Chang, C., … Bennett, G. G. (2014). A text messaging-assisted randomized lifestyle weight loss clinical trial among overweight adults in Beijing. Obesity, 22(5), E29–37. December 4, 2016 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24375969

- Montag, C., Błaszkiewicz, K., Sariyska, R., Lachmann, B., Andone, I., Trendafilov, B., … Markowetz, A. (2015). Smartphone usage in the 21st century: Who is active on Whatsapp? BMC Research Notes, 8(1), 331. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1280-z

- Newton, R. L., Jr, Marker, A. M., Allen, H. R., Machtmes, R., Han, H., Johnson, W. D., … Church, T. S. (2014). Parent-targeted mobile phone intervention to increase physical activity in sedentary children: Randomized pilot trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 2(4), e48. doi:10.2196/mhealth.3420

- Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., Margono, C., … Gakidou, E. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. The Lancet, 384(9945), 766–781. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8

- Nollen, N. L., Mayo, M. S., Carlson, S. E., Rapoff, M. A., Goggin, K. J., & Ellerbeck, E. F. (2014). Mobile technology for obesity prevention: A randomized pilot study in racial- and ethnic-minority girls. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(4), 404–408. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.011

- Perez-Escamilla, R., Lutter, C. K., Rabadan-Diehl, C., Rubinstein, A., Calvillo, A., Corvalán, C., … Rivera, J. A. (2017). Prevention of childhood obesity and food policies in Latin America: From research to practice. Obesity Reviews. Suppl, 2, 28–38. doi:10.1111/obr.v18.S2

- Piette, J. D., Lun, K. C., Moura, L., Fraser, H., Mechael, P., Powell, J., & Khoja, S. (2012). Impacts of E-health on the outcomes of care in low- and middle-income countries: Where do we go from here? World Health Organization. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(5), 365–372. doi:10.2471/BLT.00.000000

- Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. Retrieved September 21, 2016, from http://ajhpcontents.org/doi/abs/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

- Shapiro, J. R., Bauer, S., Hamer, R. M., Kordy, H., Ward, D., Bulik, C. M. (2008). Use of text messaging for monitoring sugar-sweetened beverages, physical activity, and screen time in children: A pilot study. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 40(6):385-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.09.014.

- Sharifi, M., Dryden, E. M., Horan, C. M., Price, S., Marshall, R., Hacker, K., … Taveras, E. M. (2013). Leveraging text messaging and mobile technology to support groups and interviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(12), e272. doi:10.2196/jmir.2780

- Woolford, S. J., Barr, K. L. C., Derry, H. A., Jepson, C. M., Clark, S. J., Strecher, V. J., & Resnicow, K. (2011). OMG do not say LOL: Obese adolescents’ perspectives on the content of text messages to enhance weight loss efforts. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 19(12), 2382–2387. doi:10.1038/oby.2011.266

- Yañez Gallardo, R., & Cuadrea Olmos, R. (2008). La Técnica Delphi Y La Investigación En Los Servicios de Salud. Ciencia y enfermería, 14(1), 9–15. Retrieved May 9, 2017, from http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-95532008000100002

Appendix A.

Final List of Messages