Abstract

In Africa, research and studies have adversely relegated the effects of inadequate service provision on the poor to the background. Yet, quagmires resulting from severe strike actions, agitations and revolutions are grasped throughout the continent. This paper tends to ponder on the effect of inadequate service delivery on the quality of life of the poor with a focus on education and health in Nigeria. A mixed method was used for data collective; (quasi) quantitative and qualitative medium were exploited to gather data for this paper. A descriptive method based on empirical data and narrative literature analysis was used to demarcate the paper into themes. It found among others that over 70% of inmates in Nigerian prisons are on awaiting trial. It also demonstrated that the tripartite alliance of institutional failure, corruption and poor leadership (self-serving leaders) inhibits the provision of basic services in the country. In conclusion, cronyism, cabalism, nepotism and sycophancy, including inadequate interaction of systems, institutions and structures are decried as the bane of Nigeria’s underdevelopment, which have had adverse negative effects on the educational and judicial sectors thereby undermining the well-being of the poor.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

For Africa and Nigeria in particular to grow, the way in which services are provided must be reconsidered. Recent squabbles involving either loss or destruction of government properties in Africa are mainly due to inadequate service provision. It is evident that a single research paper cannot cover all sectors of government anomalies. Therefore, in this paper education and health are given greater attention, while citing examples from the criminal justice system in Nigeria. The paper shows that for the country to achieve any form of development, the educational sector must be revamped. In that, the quality of education determines to a large extent the expertise and professionalism of health practitioners and legal luminary in the country.

1. Introduction/background

The exposition of this study is to assess the effect of inadequate service delivery on the poor in Africa; it x-rays two sectors in the Nigerian economy: justice and education. Premised on the notion that there exist little or no empirical study conducted primarily or secondarily, assessing the effect of inadequate service provision on both sectors.

The effect and power of service provision in Africa is an untold story, which have ridiculed or brought to disrepute government interventions in poverty eradication intervention and social inequalities, which inadvertently hamper the implementation of the sustainable development goals of the United Nations. Hence, this study rethinks service provision in the context of poverty studies, development policy and public administration and management. It takes into cognizance two paradigms towards achieving a developmental state as contained in the SDGs of the UN namely: justice and education. Mixed method approach (quantitative and qualitative) was utilized in addressing the concerns of this paper.

This paper can be understood from three spheres, the first dealing with introduction, background and rationale for identifying the important components, which sets the scene for analysing the constructs of the subject matter. Albeit, it tends to discuss the educational sector further from the standpoint of tertiary education which is seen as the minimum qualification presently to secure a stable job that could uplift one and their family from poverty.

From time immemorial, the need for the provision of services in societies is laid predominantly on the government, caliphate, kingdom or likewise. Governments over the world have taken full responsibility for the challenges and prospects for these: health, education, sustainable cities and communities, electricity and peace and justice in Africa and elsewhere. As the world continue to emerge or evolve, its challenges have become much complex than the first.Footnote1 This is the case for governments in Africa, and most importantly for service providers in various nations in the continent.

Ineffectual service provisions are central to fragility and weakness in the governance framework or system (Agborsangaya‐Fiteu, Citation2009; Vallings & Moreno-Torres, Citation2006). For instance, in terms of justice, the poor are left at the mercies of God (Ottuh, Citation2013). Where the right of a poor individual is violated, they (the poor) rather commune with their God to intercede than approach the court or the police for justice, largely due to ignorance and mainly cost (Jibueze, Citation2016).Footnote2 In that, in Nigeria, there is high probability that when a poor individual reports a violation of his/her right to the police he/she might be locked behind bars. This tends to portray the level of inequality in the country, which has also affected judicial system in the country (Akinwotu & Olukoya, Citation2017; McIntyre, Citation2017; Oxfam, Citation2017). The nature of ineffectiveness and gross ineptitude in the country provides a quick reminder of the novel Animal Farm by Chinua Achebe, or much like a vampire state (where the poor is likened to the prey and the rich/government the predator) (Abubakar, Citation2017; Egbujo, Citation2017; Kirwin & Cho, Citation2009; Otaru, Citation2012). For instance, in an incident where a commoner stole a phone of a Governor worth #50,000 (less than $200USD), the individual was sentenced speedily to 45 years imprisonment (Odesola, Citation2013; Osasona, Citation2015, p. 76). But the laws protect politicians, government official and the elite in the society through perpetual adjournment, more worrisome is that these politicians are celebrated and given honourarium (Aguda, Citation1988; Ojukwu, Citation1997; Okogbule, Citation2004, Ogunode, Citation2015).Footnote3 In essence, Nigeria is a country that celebrates unmerited and sudden wealth (money by any means necessary) at the expense of values, norms and integrity.

2. Material and method

In research, there is hardly a best method for gathering data for social research (Ndaguba & Hanyane, Citationforthcoming). Been said, in social science research, there are two broad methods to which researchers choose from in conducting research—quantitative and at the other extreme is qualitative. However, between both methods lies the mixed method, which is a combination of numbers and words, respectively. According to Ndaguba (Citation2018), “there is no one best way/method in social research for conducting research.” However, the entire research is dependent on the ability of the researcher to gather, synthesize and analyse reasonable data for problem-solving in a research, which is in support of the research topic and questions (Ndaguba, Citation2016, p. 12; Ndaguba, Ndaguba, Tshiyoyo, & Shai, Citation2018). Writing a research methodology is at the epicentre of any scientific research endeavour. A research methodology gives credence and determines to a large extent the feasibility of achieving both the aims and means of a study. In any case, where the research methodologies are questionable, the entire research outcome is questionable.

The modality for gathering data for this paper was principally desktop with search engines as, Catalogue of theses and dissertation of South African Universities (NEXUS); The World Justice Project; EBSCO EconBiz; Google Scholar Index; and World Bank Database. In essence, it has been argued that the bedrock of the desktop research is predominantly the ability to search for reasonable data, synthesize the quality of the data and ensure that the right amount of data is collected and analysed for problem-solving, in tandem with the object or question of the paper.

The desktop research approach used in this study is consistent with both the (quasi) quantitative and qualitative paradigm data collecting. And the theme analysis was used utilized in analysing the paper.

3. Basis for analysis

It is impossible for a single research paper to pretend to capture and analyse all problems of societal inadequacies in a nation, a region or a continent. So in this paper, both justice and education will be harnessed with regard to their impact on the poor. It is trite to note that Nigeria is the most populous black nation on earth and the leading economy in the continent. However, either the growth in the GDP or the population has transcended towards benefitting the poor in the country (Udoh & Ayara, Citation2017, p. 1). One may rather argue that both had no impact in the economic well-being of the nation.

Hence, an increase in the GDP has had no effect on those in poverty, which is the reason the incidence of poverty in the country has continually increased (Ocheni, Citation2015; Ndaguba, Citation2016; Ndaguba and Okonkwo, Citation2017). Although, some economist have demonstrated that a proportional increase in GDP inadvertently leads to the reduction in the number of poor (Agrawal, Citation2008; Ravallion, Citation2007; Venables, Citation2008). However, in developing nation, especially in Nigeria, this is not so, as an increase in GDP results in an increase of other market commodities, which makes the effect of the GDP insignificant to human well-being (Ocheni, Citation2015; Ndaguba, Citation2016; Ndaguba and Okonkwo, Citation2017). This anomaly depicts the inherent nature of the effect of capitalism and self-serving leadership exhibited by the leadership in Nigerian, which tend to undermine the poor in the country. This constitute gross injustice and abuse to the fundamental human rights as enshrined in Section 35 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria

3.1. The effects of inadequate service provision on justice and its influence on the quality of life of the poor

The place of the judiciary and the judicial system is very paramount in a democratic society. To Ogunode (Citation2015), the judicial system is a branch of the law that deals with crime, the nature of the crime and sets suitable punishment for offenders/offences. In the words of Michael Corbett, a Chief Justice of South Africa, “the executive might transgress, the legislature might become unruly, but it has always been the judiciary that has stood the test of time by standing firm on the side of truth and justice” (Cocodia, Citation2010, p. 4). The significance of the judicial system cannot be overemphasized and the necessity for the judicial system to uphold the truth regardless of personalities is of utmost importance.

Modern justice system as imagined depicts a system that keeps society safe from deleterious and hazardous effects of crime prone individuals, criminals and law-breakers. A society with a high crime rate is a guarantee for low productivity, discord; lawlessness, strife and indiscipline (see Northeast Nigeria). Which are clear indicators of a nation twinning towards a failed state status (Ogunode, Citation2015, pp. 28–29). According to Osasona (Citation2015, p. 74), “a country that gets its criminal justice system right has effectively addressed a great part of its governance concerns because of the centrality of the criminal justice system to maintain order and stability.” On the contrary, a country that does not get its justice system right will become a burden to both the governance structures and its people; primarily resulting in her inability to maintain law, order, stability and to protect both lives and properties of her citizens.

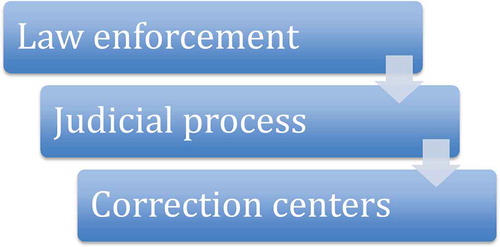

It must be established that the judiciary in Nigeria and elsewhere is the third branch of government saddled with the responsibility of defending and upholding the constitution, while providing sanctity to the rule of law (Ladner, Citation2006, p. 1; Cocodia, Citation2010, p. 4). There are three components of the judicial system, law enforcement (sheriffs, police and marshals), corrections (probation, prison and parole officer) and the judicial process (prosecutors, judges and defence attorney) that should work harmoniously in maintaining law and order.

On the contrary, the perception about the justice system in Nigeria is overtly flawed and negatively biased towards the poor. According to the 2008 Amnesty International report, Nigeria judicial system was indicted and referred to as a “conveyor belt of injustice, from beginning to end”. Similarly, Bolaji Ayorinde (SAN) concurred with the report of Amnesty International and opined that the judicial system in Nigeria is a “dysfunctional, outdated and absolutely not fit for purpose”.Footnote4 In the same vein, a Former Speaker of the House of Representative in Nigeria stated, “our criminal procedure has remained largely old and unresponsive to the quick dispensation of justice.”Footnote5 According to the Solicitor General of the Federation and Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Justice, Abdullahi Yola, the justice system in Nigeria lacks the necessary legislations and policy framework that facilitates fair trials of suspects (Bamgboye, Citation2013).

From the foregoing, it is safe to say that the judicial system in Nigeria is in a state of comatose. An excerpt from a National Daily demonstrates the decay of the judicial system in the country as follows:

(According to) Mr Spurgeon Ataene…services of good lawyers were costly and for that reason, the rich would always have an edge over the poor in getting justice.

A lawyer who will stand to make a sentence or two can charge you N500,000 or N1 million, depending on the kind of lawyer. Ataene further argued that lawyers in the Office of the Public Defender (OPD) in Lagos still requires certain fees to file a case. Ataene (further showed his frustration that) some lawyers of OPD… (who were meant to appear pro-bono) still charge fees and their fees are even more expensive. So how can the poor man be favoured (?), they can never be favoured (?).

(To) Nkem Eke the system is the issue. In that, the common law being operated in the country sacrifices the poor at the altar of the rich in seeking justice. Basically, (Eke argued), we need to look at the system we operate in Nigeria. We operate the common law system and what it means is that each person has to present his own case. It is what you present to the judge that will determine the judgment you received. (He equally emphasized) that the poor also lack the necessary information, and that this could affect any case presented to the judge. The poor sometimes do not give their lawyers the necessary information, which becomes a problem to both the lawyers and the defendant.

(Another lawyer) Uche Nwanueke (lamenting about the decay in the judicial sector) painted a much broader picture as relating to the decadence of structures and system in the Nigeria. He argues that the decay is not merely in the justice sector but all other professional services in the state. (Nwanueke argues), that high cost of professional service was not only applicable to the judiciary, but cut across all spheres of all service providers. For instance, in the medical line, it is the same thing; if you go to the hospital and you are not able to deposit money for treatment, there is a problem. If you do not pay, they will not attend to you; that is why most patients die. If you do not have the money to pay for a good lawyer, then you will also sufferFootnote6

The state of res judicata is in complete collapse to say the least, retrogressive and in shambles, where justice and equity are given to the highest bidder and the honour of Nigeria’s judiciary slaughtered to the birds (Fapohunda, Citation2016). According to Nwanueke, Nkem and Ataene, it is evident that justice system in Nigeria is infrastructural deficient, undermanned, inadequate, corrupt, inefficient, under-financed and prone to abuse and a threat to the rule of law. The judicial system is a mere microscopic embryo of the larger microbial system, which feast on the poor it intends to protect.

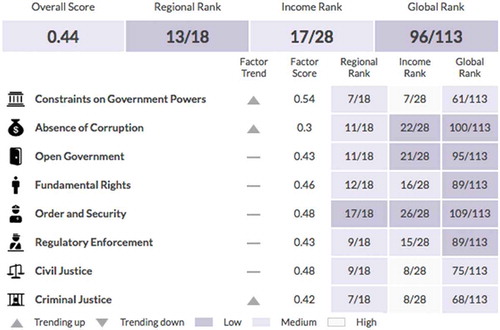

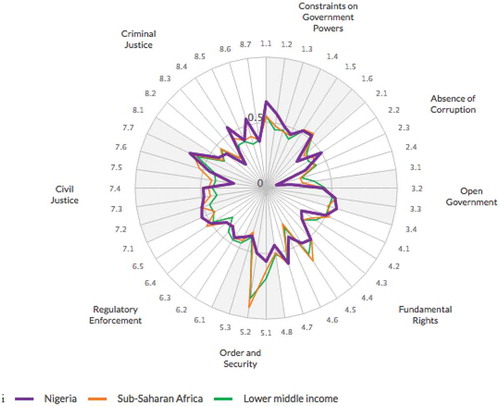

Politically, as an entity, Nigeria is bedevilled by myriads of political and socio-economic problems that are multifarious in nature (Ubeku, Citation1991, p. 39, Ogunode, Citation2015). Some of the quagmires that have inhibited productive judicial process include political instability, corruption, uncertainty, moral decadence, poverty and various forms of economic and political crimes and maladies (Musa, Citation1991; Ndaguba et al., Citation2018). These problems are indicative of the underdeveloped and under-developing state of Nigeria (Eze, Citation1998; Omotola & Alumona, Citation2016). Regrettably, the judicial system, both the bench and bar have been caught-up in these miasma plaguing the polity (Obutte, Citation2016). Hence, several judges have been compromised in the discharge of their official duties, leading to frustrations in the judicial process (Ogunode, Citation2015, p. 29). Tables and show the weak nature of the justice system in dispensing justice adequately in Nigeria. Consequently, resulting in the deprivation of over 70% of its prisoners’ access to fair hearing in a constituted court of law, which is a gross infringement of the fundamental human rights of these citizens. This junk and inhumane status of the judiciary has earned them poor ratings in both global and regional criminal justice system rankings in the world (see Tables and ).

Table 1. Criminal Justice System Ranking

Table 2. Awaiting Trial Inmates at Kirikiri Prisons

Figure and Table establish a causal relationship between overcrowding in prison and inept judicial system (see Table ). The population of those awaiting trial in prisons in Nigeria demonstrates the nature of the failed judicial system that is both incapable and irresponsible in administering justice on the one hand, and an institution that has reprimanded thousands/millions of individual without a probable cause or charged, of whom 95% are the poor. This notion is in tandem with the assertion of The World Justice Project (Citation2018) report on Nigeria and concurs with the dwindling rate of the implementation of rule of law. This is probably because where the rule of law is amendable to suit individuals or when the rule of law is fallible then the entire social justice system needs an overhaul (John, Citation2011; Okpata & Nwali, Citation2013). While on the other divide, the rich in the society enjoy plea bargains and injunctions to do them no harm or persecution (Imosemi, Citation2017; Obutte, Citation2016; Ogunode, Citation2015; Osasona, Citation2015).

Table 3. Prisons congestion in South Eastern States in Nigeria

Although, the law of natural justice connotes that one is innocent until proven guilty. But in Nigeria, one is guilty until proven innocentFootnote7 which is in contravention of Article 7(1)(b) of the African Charter on Human and People’s Right of 1981 and Section 36(5) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Sarkin (Citation2008) argues that overcrowding in prison results in damaging health consequences. The philosophy adduced by Sarkin (Citation2008, p. 23) was equally corroborated by Boone, Lewis, & Zvekic, Citation2003, pp. 141–145), “generally speaking, those incarcerated in African prisons face years of confinement in often cramped and dirty quarters, with insufficient food allocations, inadequate hygiene, and little or no clothing or other amenities…. Moreover, there are also several barriers—including state secrecy, weak civil society, and lack of public interest—that inhibit the collection of reliable data on African prisons.”

3.2. The effects of inadequate service provision on education and its influence on the quality of life of the poor

The provision of education in Nigeria is in the concurrent list, which gives all tiers of government the statutory right/obligation to provide such education except tertiary. State and federal government not local government provide tertiary education. Due to the deficiencies of state tertiary education in Nigeria, the private sector was incorporated to operate tertiary education. Hence, today the private, the state and the federal government provide tertiary education. While all three tiers of government including the private and missionaries are permitted to provide secondary or high school and primary education as well.

In Nigeria, government provides free primary and high school education under the Universal Basic Education. However, while government schools offer free education, quality education is far-fetched. Taking into cognizance the nature of classroom, environmental conditions of learners, non-provision of instructional material, ill-equipped libraries were existent; instruments for arts, science, technology and innovation, vests for sports and other recreational facilities are none existent. Nonetheless, in Nigeria to be gainfully employed at least one requires a tertiary education.

4. Tertiary education and the effect on the poor

According to Famade, Omiyale, and Adebola, (Citation2015, p. 83), tertiary education in Nigeria defines the quality of life that an individual enjoys. Since, it is the foundation on which societal values and economic growth of an individual is dependent. To Ahmed (Citation2015, p. 92), the demand for education is tremendously high, as it is seen as the only investment in escaping poverty. It has also been argued elsewhere as a pre-requisite for economic advancement and development. According to Watkins (Citation2013) “the ultimate aim of any educational system is to equip children with the numeracy, literacy and wider skills that they need to realize their potential—and that their countries need to generate jobs, innovation and economic growth.” In Nigeria and the wider community, tertiary education is seen as means through which a family, individual and household can escape poverty and stagnation in the country.

Hence, a disjuncture exists between the educational sector and the employment sector in the Nigerian economy. More misaligned is the nature of specialized skill-set required and the nature of graduate specialization in the country. This tends to establish the decay in the educational systems in the twenty-first century, which has made several millions of graduates unemployed in recent times.

The rate of unemployment is progressive in nature, due to, policy decisions that have continued to impede foreign investment and threatens local market indices. These have resulted in severe damage to recruitment in private investment, resulting in several withdrawn interest in the Nigerian economy owing to mistrust of government’s capacities to pilot the economy and for decision-makers to allay the fears of both local and foreign investors.

5. Conundrum to the Nigerian state in providing services

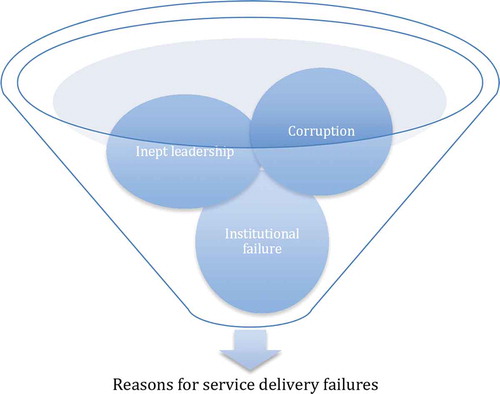

There are three major limitations that have continued to ridicule the development of the Nigerian State and have also halted the ability of the state to provide services to the poor in a sustainable manner. These would include but not limited to the following: corruption that have fueled unemployment (see Figure ), inept leadership and the inability of institutional structures and systems to interact harmoniously (see Figure and ).

These tripartite alliances of corruption, inept leadership and institutional failure are identified in this paper as the critical obstruction to Nigeria’s development and emergence in the Global North.

The dignity and efficacy of the legal system to fulfil its mandate of law enforcement (DSS, Police and Marshals); the judicial process (prosecutors, judges and defence attorney); and corrections (probation, prison and parole officer) (see figure ) are paramount. Taking into cognizance the travesty credited to poor leadership, corruption and institutional failure. In the view of providing services that is unbiased and fair at all times, regardless of persons.

Figure 5. Multidimensional factors in analysing the justice system in Nigeria

In the case of the Nigerian justice system, these three steps (as seen in Figure ) are very paramount, since they determine how the rights and duties of citizens are dispensed, enforced and protected regardless of the person involved (see the multidimensional system for analysing the justice system in Nigeria in Figure ). A significant attribute borrowed from the colonial administration in Nigeria is that the Nigerian Law is not a respecter of person (rich or poor). Fairness, equity and justice are the watchword in the enforcement of law and order in the Nigerian state. As sited elsewhere among the three steps in the Nigerian judicial system, the most effective over the years has remained law enforcement (lawful arrest). Lawful arrests are legal and binding; a person is lawfully arrested, if an officer conducting such an arrest is in possession of a warrant of arrest. Whereas in a case or situation whereby the officer in charge does not produce a probable cause or a warrant of arrest the officer in charge can be charged for gross violation of an infringement to person’s right of liberty as enshrined in Section 35(1) of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Infringement of false imprisonment or bridge of the constitutional right of personal liberty is a constitutional mandate guaranteed by Section 35(1), thus:

Every person shall be entitled to his personal liberty and no person shall be deprived of such liberty save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedure permitted by law (1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria).Footnote8

Over the years, there have been pockets of arrest that have been unlawful mainly due to false information or raid. False information and raid account for most of the persons on the awaiting list trail.Footnote9,Footnote10 According to statistics, the numbers of unwarranted politically motivated arrest have exceeded 2,000 from 2016 to March 2017. Prominent among them are Nnamdi Kalu and hundreds of IPOB members, Shite leader Ibrahim El-Zakzaky and his wife Malami Zeenat, including hundreds of his followers, Sambo Dasuki, Babatunde Gbadamosi, Fani Kayode, Dapo Olurnyomi and others.Footnote11,Footnote12,Footnote13,Footnote14,Footnote15

6. Characteristics and elements of unlawful detention in Nigeria

The following constitutes essential characteristics of unlawful detention in Nigeria:

Being locked up in a car, room, cinema, airplane, goal post, toilet, or any enclosure that limits one’s restriction without one’s consent;

Being threatened or held up at gunpoint to prevent ones’ movement;

Being unlawfully in custody of the Nigerian Police Force, Nigeria Armed Forces (including Nigeria Civil Defence Corps), Economic and Financial Crime Commission, Independent Corrupt Practices Commission, Nigerian Immigration Service, or any Nigeria military or para-military agency vested with the responsibility and power to arrest and detain.

Also there are three critical elements of unlawful detention, which have been upheld over the years by the Nigerian Courts, namely:

A total restraint of a person’s movement;

Restraining a person without consent, probable cause, or justification;

Where there is no way out of the restrained area or restraint.

It must be noted with caution that the over 2,000 are politically motivated. Exempting those confined without money to bail themselves or persons to surety their bail, arguably results in the overcrowding of the prisons in Nigeria.

According to Human Right Watch (Citation2010), widespread corruption in the Nigerian Police Force has resulted in flagrant abuse and extortion from the poor, which undermines the aim of the establishment and negates the doctrine of the rule of law.Footnote16

Borrowing from Somalia’s Legacy Centre on Peace and Transparency (UNDP, Citation2004), the impact of corruption in government is multifaceted and multidimensional, thus:

Corruption is undeniably the greatest challenge to rebuilding Somalia’s political, educational, economic, security, health and infrastructural networks. Corruption discourages taxing and stifles entrepreneurship, “lowering the quality of public infrastructure, decreasing tax revenues, diverting public talent into rent-seeking, and distorting the composition of public expenditure.” Furthermore, the consequences of corruption negatively affect democracy and rule of law, as well as erode public trust in government, which undermines institutions, as well as processes at all levels of society.

Taking a definition from Somalia might seem unsuitable and malicious in comparison with Nigeria. However, both nations have diverse relationships, both are at the verge of collapse, they are both torn by conflict, institutional decay, epileptic leadership and ineffective governance structure and systems, which hamper productive capability of the poor in Nigeria to fulfil their optimal desires and civic responsibilities. These are primarily the aftermath of inept and visionless leaders to steer the ship of the country from colonial bondage and self-accumulation of wealth. Most leaders (frontrunners) in the country are self-serving, which has an overall effect that undermines institutions that protects the poor. According to Ubi, Effiom, and Mba (Citation2011), institutional failure refers to weak capacity or the lack of efficient service provision by institutions (Ubi, Effiom, & Baghebo, Citation2012, p. 931). The essence of institutions in Nigeria is to ensure that all tiers of government are responsible and responsive in delivering services to its citizen in a sustainable manner on the one hand, and maintaining law and order on the other.

According to Ubi et al. (Citation2012, p. 931), institutional failures are reinforcing social and economic inequalities, widespread deepening poverty and undermining service provision where the government intends to provide such services. Accordingly, institutional failures are attributed to corrupt practices, self-serving leaders, state capture, cabalism, weak infrastructure, weak systems, weak framework, weak corporate governance, nepotism and ethnicism among others (933). These shortcomings are resultant effects of both compromised judicial and educational system that hampers effective institutionalization of governance framework in the country (see Figure for the poor state of the justice system in regional and global scale).

7. Limitation of study

The field of service delivery is vague. With an observation that no single research within the bandwidth of a textbook or paper article can claim to discuss or provide a panacea to the myriad of challenges in a country. This study has limited its analysis to two main catalysts towards a developmental state, namely, education and justice. The idea is to ensure that this study informs government policies on poverty strategies, policy intervention and development, showing the effect of deficient institutions on the poor. Other limitations we have identified include, none comparative nature of the study, time, it confines itself within this two factors education and justice. Also is the secretive state of information in the country, to this end, The World Justice Project (Citation2018), argued that among 113 countries analysed for open government in their report, Nigeria occupied the 88th position. Hence, one of the reasons why data used in this study was mainly 2014 and 2015.

8. Findings, summary, recommendations and conclusion

This section is divided into three, the first dealing with the summary of the study and the summary of findings in this paper. The other provides means through which amends could be made to ensure an effective service delivery in Nigeria. The third section deals with conclusion of the study.

The central finding of this paper is that institutions in Nigeria have failed to provide services, which they are required by law to provide.

Institutional insensitivity is a reason for increased dilapidation in education and justice sectors in the country.

From this paper, it is established that the justice system in Nigeria is in disarray (where the rich buys justice to intimidate the poor).

Over 70% of inmates in Nigerian prisons are on the awaiting trial list.Footnote17–Footnote18

We recommend:

The urgent need for reforms that are geared towards rehabilitating prisons, including an overhaul of the justice system in Nigeria.

The urgent need for reforms on curriculum structure, provision of reading materials and libraries, construction of science labs for innovation and technology, provision of recreational facilities in schools to mention a few.

Government, industries and NGOs must partner to develop skills that are required in universities. Courses must not be offered for the sake of it. If it does not have any relevance to the government, industries and NGOs, such course must be seen as specialized courses with fewer enrolments.

An effective monitoring and evaluation system or perhaps a ministry must be established and a section dedicated to monitoring, evaluation, communication and reporting of government activities.

To ensure a total restructuring of the approach that have remained ineffective and inadequate in delivering services to communities in a sustainable manner.

That employment should be based on merit rather than quota, god-fatherism and “Ima-Madu” connection otherwise cronyism.

To ensure that government instils the principle of accountability as seen in the context of good and effective governance framework.

To promote research and development in the academia and justice sector by providing adequate funding streams.

To promote the rights of citizens and instil the concept of citizen’s responsibility in the state through dialogues and citizens’ awareness campaign.

In sum, it can be deduced that inept leadership, corruption and institutional failures (ICI) have crippled government’s structures and system to adequately provide for the poor in the society. Hence, the systems that were built to safeguard and protect the poor from the mighty have ultimately been the destruction of the poor in Nigeria. The tripartite alliance of ICI is responsible for the lackadaisical approach of service provisions to the poor. This resonates an Igbo adage that says, “cow that does not have tail, its God drives away the flies from its body.”Footnote19 This adage embraces all forms, nature and life of the poor in Nigeria, where the poor has no rights, no privileges, no justice, no effective educational structures and system, no voice and no dignity due to an oppressive colonial inherited system, which enriches the rich and suffocates the poor.

In conclusion, a narrative from an anonymous writer contends that cheating in examination is capable of ruining an entire system, nation and continent.

Collapsing any Nation does not require use of Atomic bombs or the use Long Range Missiles. But it requires lowering the quality of Education and allowing cheating in the examination by the student.

The patient dies in the hands of the doctor who passed his examination through cheating.

And the buildings collapse in the hands of an engineer who passed his examination through cheating.

And the money is lost in the hands of an accountant who passed his examinations through cheating.

And humanity dies in the hands of a religious scholar who passed his examinations through cheating.

And ignorance is rampant in the minds of children who are under the care of a teacher who passed examinations through cheating.Footnote20

To this end, it is imperative to understand that the both quality and efficacy of the educational system is of utmost importance. Education must be able to inspire creativity, innovation, research and development, which is capable of building a developmentally oriented society. One may not argue that where the educational system is haphazard in the dispossession of its activities, it may affect the judicial system. In that the educational system has a linear relationship with the quality of the bench, intelligence unit among others. In the same way, a judicial system that is unable to dispense justice fairly is retrogressive and deems the rights of persons. Therefore, for a country like Nigeria to evolve in the globe, basic services of fairness, equity, human rights, human dignity and innovative educational system is to be restored.

8.1. Future studies

In equifinality, the nature and scope of a research must give room for further studies, in that, a single research endeavour does not have the ability to solve all the problems associated with a particular study. Hence, it will be adequate to provide some areas of interest or concentration, which further studies within this subject matter, must be geared towards. They include among others:

The effect of poor funding on the quality of education in Nigeria,

The dynamic and role of adequate service delivery on social and human capacity development in Nigeria,

The consequences of unplanned and unmanageable change on public institutions for service provision,

The role of institutional failures, corruption and dysfunctional organizational system and structure on service provision in Nigeria,

The place of educational entrepreneurship and the principle of collective responsibility in Nigeria,

How can overhauling the public service reduce bribe, corruption and criminality and

Calibrating the public service for optimum efficiency and effectiveness.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emeka Ndaguba

Emeka Ndaguba is a Research Assistance at the Institute of Development Assistant Management (IDAM), School of Government & Public Administration, University of Fort Hare.

EOC Ijeoma

Professor EOC Ijeoma is the Head of School, Government & Public Administration, University of Fort Hare. The Editor in Chief—Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, Local Government Research & Innovation, ASSADPAM Book Series, and Executive Director—Institute of Development Assistance Management.

GI Nebo

GI Nebo is a Doctoral Student and researcher at the University of Fort Hare.

AC Chungag

AC Chungag is a Lecturer at the Department of Development Studies at the University of Fort Hare. He specializes in human demography, population and urban dynamics, and smart and innovative cities.

JD Ndaguba

JD Ndaguba (Esq.) is a Legal luminary, specializing in constitutional law, human right laws, and corporate law from the University of Ibadan.

Notes

1. For example, as a vaccine is discovered for a cure of a disease another disease is let loose. Similarly, when a solution is proffered and implemented (no school fees for basic education) another problem is harvested, needing a different approach to the first.

3. Such a person would readily be the beneficiary of chieftaincy titles in his community and even receive national honours. The present spate of chieftaincy titles being given to the various state governors underscores this point. For example, the Rivers state Governor, Dr Peter Odili was recently given the title of Obafuniyi of Yorubaland by the Ooni of Ife, Oba Okunade Sijuwade Olubuse (Okogbule, Citation2004, p. 2).

6. A cross-section of views of the reason why the poor can not get justice in Nigeria from a Newspaper article: http://www.vanguardngr.com/2012/03/lawyers-speak-on-why-poor-nigerians-cant-get-justice/.

11. https://www.sunrisenigeria.com/news/local-news/ipob-police-clash-ph-aba-200-members-missing-ipob/.

19. Efi na enweghi odu, o chi ya na-churu ya ijiji.

References

- Abubakar, G. B. (2017). Condition of women in Nigeria: Issues and challenges. Arts Social Sciences Journal, 8:(293). doi:10.4172/2151-6200.1000293

- Agborsangaya-Fiteu, O. (2009). Governance, fragility and conflict - Reviewing international governance reform experiences in fragile and conflict-affected countries. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Agrawal, P. (2008). Economic growth and poverty reduction: Evidence from Kazakhstan. Asian Development Review, 24(2), 90−115.

- Aguda, T. A. (1988, September). The challenge for Nigerian law and the Nigerian Lawyer in the twenty-first century,”. Nigerian National Merit Award Winner’s Lecture Delivered on Wednesday, 14(1988), 20.

- Ahmed, S. (2015). Public and private higher education financing in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 11(7), 92-109.

- Aileru, O. 2016a. Legal aid act 2011, untapped goldmine in decongesting Nigerian prisons. Guardian Newspaper. Retrevied March 20, 2017, fromhttps://guardian.ng/features/law/legal-aid-act-2011-untapped-goldmine-in-decongesting-nigerian-prisons/

- Akinwotu, E., & Olukoya, S. 2017. ‘Shameful’ Nigeria: A country that doesn’t care about inequality. The Guardian, Retrevied August 20, 2017, fromhttps://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/jul/18/shameful-nigeria-doesnt-care-about-inequality-corruption

- Awopetu, R. G. (2014). An assessment of prison overcrowding in Nigeria: Implications for rehabilitation, reformation and reintegration of inmates. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), (19), 21–26.

- Bamgboye, A. 2013. Nigeria’s criminal justice lacks policy direction —Solicitor General. Daily Trust. Retreived from www.dailytrust.com.ng/news/general/nigeria-s-criminal-justice-lacks-policy-direction-solicitor-general/27477.html

- Boone, R., Lewis, G., & Zvekic, U. (2003). Measuring and taking action against crime in Southern Africa. Forum on Crime and Society, UN Centre for International Crime Prevention, 3(1-2), 141–160.

- Cocodia, J. (2010). Identifying causes for congestion in Nigeria’s courts via non- participant observation: A case study of brass high court, Bayelsa State. Nigeria. International Journal of Politics and Good Governance, 1(I), 1–16.

- Egbujo, U. 2017. The Vampire and the torn nests of Nigeria’s prisons. Vanguard, Retrevied August 23, 2017, fromhttps://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/02/vampire-torn-nests-nigerias-prisons/

- Eze, O. (1998). African democracy, governance and development. In the Challenge of African Development (CASS, 1998), 71–74.

- Famade, O. A., Omiyale, G. T., & Adebola, Y. A. (2015). Towards improved funding of tertiary institutions in nigeria. Asian Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(2), 83-90.

- Fapohunda, O. 2016. The state of administration of justice in Nigeria after 365 days of the Buhari’s administration. Thisday Newspaper, Retrevied July 06, 2017, fromhttp://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2016/06/07/the-state-of-administration-of-justice-in-nigeria-after-365-days-of-the-buharis-administration/.

- Imosemi, A. (2017). Plea Bargaining in Nigeria: An aftermath of the Administration of criminal justice act 2015. International Journal of Business & Law Research, 5(4), 93–105.

- Jibueze, J. 2016. Justice for the rich (1). The Nation, Retrevied August 23, 2017, fromthenationonlineng.net/justice-rich-1/

- John, E. O. (2011). The rule of Law in Nigeria: Myth or Reality? Journal of Politics and Law, 4(1), 211–214.

- Kirwin, F., & Cho, W. 2009. Weak states and political violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Afrobarometer Working Paper No 111.

- Ladner, K. L. (2006, June). Take 35: Reconciling constitutional orders. Paperpresented at the 78th annual conference of the Canadian Political Science Association York.

- McIntyre, N. 2017. Which countries are the most (and least) committed to reducing inequality? The Guardian, Retreived23 August 2018,fromhttps://www.theguardian.com/inequality/datablog/2017/jul/17/which-countries-most-and-least-committed-to-reducing-inequality-oxfam-dfi

- Musa, S. (1991). Anatomy of corruption and other economic crimes in Nigerian public life. In A. Kalu & Y. Osinbajo (Eds.), Perspectives on corruption and other economic crimes in Nigeria(pp.94-96). Lagos: Federal Ministry of Justice.

- Ndaguba, E. A. 2016. Financing Regional Peace and Security in Africa: A Critical Analysis of the Southern African Development Community Standby Force. ( Master dissertation) UFH LIB.

- Ndaguba, E. A. (2018). Task on tank model for funding peace operation in Africa – A Southern African perspective. Cogent Social Sciences, 4, 1–20. doi:10.1080/23311886.2018.1484414

- Ndaguba, E. A., & Hanyane, B. (forthcoming). Exploring the philosophical engagements for community economic development analytical framework for poverty alleviation in South African rural areas. Cogent Economics and Finance.

- Ndaguba, E. A., Ndaguba, O. J., Tshiyoyo, M. M., & Shai, K. B. (2018). Rethinking corruption in contemporary African philosophy: Old wine cannot fit. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 14(1), a465. doi:10.4102/td.v14i1.465

- Ndaguba, E. A., & Okonkwo, C. O. (2017). Feasibility of funding peace operation in africa: Understanding the challenges of Southern African development community standby force (SADCSF). Africa Review, 9(2), 140-153. doi:10.1080/09744053.2017.1329807

- Obutte, P. C. (2016). Judicial corruption and administration of justice in Nigeria. In J. S. Omotola & I. M. Alumona (Eds.), The state in contemporary Nigeria- issues, perspectives and challenges (pp. 186–210). Ibadan: John Archers (Publishers) Ltd.

- Ocheni, S. I. (2015). Impact of fuel price increase on the Nigerian economy. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 560–569.

- Odesola, T. 2013. Man Jailed 45 years for stealing Nigerian Governor Aregbesola’s phone-PUNCH newspaper. Saharareporters, Retrieved August 23, 2018, from saharareporters.com/2013/04/30/man-jailed-45-years-stealing-nigerian-governor-aregbesola’s-phone-punch-newspaper

- Ogunode, S. A. (2015). Criminal justice system in Nigeria: For the rich or the poor? Humanities and Social Science Review, 4(1), 27–39.

- Ojukwu, E. (1997). Legal practitioner’s charges in Nigeria: Law and practice. Aba: Helen-Roberts.

- Okpata, F. O., & Nwali, T. B. (2013). Security and the rule of law in Nigeria. Review of Public Administration and Management, 2(3), 158–171.

- Okogbule, S. (2004/5). Access to Justice and Human Rights Protection in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects. Benin Journal of Public Law, 3, 34–52.

- Omotola, J. S., & Alumona, I. M. (2016). Introduction; The state in perspective. In J. S. Omotola & I. M. Alumona (Eds.), The state in contemporary Nigeria- issues, perspectives and challenges (pp. 1–16). Ibadan: John Archers (Publishers) Ltd.

- Onyekachi, J. (2016). Problems and prospects of administration of Nigerian prison: Need for proper rehabilitation of the inmates in Nigeria prisons. Tourism Hospit 2016, 5(4), 2–14.

- Osasona, T. (2015). Time to reform Nigeria’s criminal justice system. Journal of Law and Criminal Justice, 3(2), 73–79. doi:10.15640/jlcj

- Otaru, A. A. 2012. Nigeria: Country as vampire state. allAfrica, Retreived, August 23 2018, from https://allafrica.com/stories/201205080143.html

- Ottuh, J. A. (2013). Poverty and the oppression of the poor in Niger Delta (Isaiah 10: 1-4):A theological approach. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(11), 256–265.

- Oxfam. 2017. Wealth of five richest men in Nigeria could end extreme poverty in country yet 5 million face hunger. Author, Retreived, August 23 2018, fromhttps://www.oxfamamerica.org/press/wealth-of-five-richest-men-in-nigeria-could-end-extreme-poverty-in-country-yet-5-million-face-hunger/

- Ravallion, M. (2007). Inequality is bad for the poor, Chapter 2 in inequality and poverty re-examined, ed Jenkins and Micklewright. Oxford. World Bank.

- Sarkin, J. (2008). Prisons in Africa: An evaluation from a human rights perspective. Sur - International Journal on Human Rights, 5, 22–49.

- The World Justice Project. (2018). The WJP rule of law index 2017–2018. Washington, D.C.: Author.

- Ubeku, A. K. (1991). The social and economic foundations of corruption and other economic crimes in Nigeria. In A. Kalu & Y. Osinbajo (Eds.), Perspectives on corruption and other economic crimes in Nigeria (pp. 39, 41, 43). Lagos: Federal Ministry of Justice.

- Ubi, P. S., Effiom, L., & Baghebo, M. (2012). The dynamics of institutional failure and its implications on employment capacity of the Nigerian economy. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences (JETEMS), (3), 931–939.

- Ubi, P. S., Effiom, L., & Mba, L. (2011). Corruption, institutional failure and Economic development in Nigeria. Annals of Humanities and Development Studies, (2), 73–85.

- Udoh, E., & Ayara, N. (2017). An investigation of (Non-) inclusive growth in Nigeria’s Sub-nationals: Evidence from elasticity approach. Economies, 5(43), 1–17. doi:10.3390/economies5040043

- UNDP. 2004. Somalia: Governance & poverty reduction, economic and social recovery. Somaliland Cyberspace. Author

- Vallings, C., & Moreno-Torres, M. (2006). Drivers of fragility: What makes states fragile?. Department for International Development, Working Paper for Discussion Only Not UK Government Policy. Bristol, UK.

- Venables, A. J. (2008, September). Rethinking Economic Growth in a Globalizing World. World Bank Publications, The World Bank, No. 28041. Washington, DC.

- Watch, Human Right. (2010). Everyone’s in on the game: corruption and human rights abuses by the nigeria police force. Human Right Watch. Retrieved 28 September 2018, from https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/08/17/everyones-game/corruption-and-human-rights-abuses-nigeria-police-force

- Watkins, K. (2013). too little access, not enough learning: Africa’s twin deficit in education. Brookings: New York.