Abstract

This paper challenges both public and private African institutions to tap opportunities residing in the diversity of all forms for the development of the continent using the grounded theory approach. African countries are often confronted by challenging socio-economic and demographic situations and set apart by the diversity of their social mechanisms. The paper argues that, for Africa’s development, there is little doubt that diversity management is indispensable presenting a positive scope for innovative “made in Africa” policies. The limitations of this research relate largely to its dependence on success examples that have been noted outside Africa with cultures and origins of non-black descent.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Human diversity particularly ethnic and cultural has not been easy to tolerate in all facets of life affecting livelihoods and in the worst scenario degenerating into xenophobic attacks. This has been due to rigidity and conservative tendencies that characterise humankind yet recent studies have shown that there is in fact strength in diversity. There is need for a paradigm shift from the traditional perspective of ethnic and cultural exclusion to that of tolerance and inclusion. Research indicates that in some developed countries strength in diversity has been witnessed and Africa should not be an exception. This study reveals that some organisations still have to grapple with the oddities of regarding diversity as retrogressive and recommends a change in mindset for Africa to tap its diversity for development. Diversity management should be part of the strategic plans comprising both management and employees.

1. Introduction

In the words of April and Shockley (Citation2007, p. 1) among other continents, Africa is “straining to transform itself in the competitive world against socio-national institutional demands.” In this reshaping of economies, it becomes imperative that the issue of regional identities be revisited to spur development. Generally, African countries are highly diverse in view of some of the exclusive primordial markers, particularly ethnicity. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA, Citation2011, p. 4), if language is taken as a proxy for ethnic identity, Nigeria is said to be home to some 470 languages with the Democratic Republic of Congo hosting some 242 languages, Sudan (both North and South) having 134 languages, Ethiopia having 89 languages, and Gambia such a small country having 10 languages. There is also a remarkable diversity in terms of religion, though Christianity and Islam enjoy the largest following in much of the continent.

Yet, even these two major religions have many denominations, which arguably have contributed to conflicts in countries such as Algeria and Somalia. April and Shockley (Citation2007) view the role of Africa as one that acknowledges the true potential of people, the strength of diversity in their multiculturalism. Institutions need to focus on diversity and devise ways to become totally inclusive entities since diversity has the potential of yielding greater productivity and competitive advantages. Valuing and managing diversity is a key constituent of effective people management, which can improve workplace production. Diversity that is not managed in the workplace may become an impediment for achieving organisational goals. Diversity can be perceived as a double-edged sword (Mazur, Citation2010).

A diverse workforce is a manifestation of a changing market world. Diverse work teams bring high value to organisations in view of laboratory research and respecting personal differences may benefit the workplace by creating a competitive edge and increasing work productivity. Moreover, diversity management is beneficial to associates by ensuring a just and safe location where each person has access to the same opportunities and challenges. Management in a diverse workforce must be used to inform everyone about diversity and its issues, as well as laws and regulations. Since most of the African workplaces are made up of diverse cultures, institutions need to learn how to adapt to be successful. This study reviews the complexity and meaning of cultural diversity in an attempt to ascertain how it can bring positive effects on the African continent. It was carried out in 2017 from seven randomly selected countries’ big industries across Africa, namely, Kenya, Mozambique, Botswana, Ghana, Libya, Burkina Faso and Chad.

2. Compelling issues-motivation of the study

Studying cultural diversity gap is important because it is often only understood in the negative in light of xenophobic attacks and ethnic wars. Yet, the positive side is replete with developmental gains that are less understood, particularly in the African context. The nexus between diversity and development is one that must never be underestimated in the continent in view of how it has influenced positively some developed economies like the United States of America (USA), Australia, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates, among others. It appears there is no similar study that has been undertaken yet. The question begging an answer is: “What could be the challenges militating against Africa’s diversity management hampering development?” Booysen (Citation2007) supported by Beaty and Booysen (Citation1998) state that, if diversity is efficiently managed, it can drive an organisation into a successful and competitive future. But if not, the development and competitive advantage of the organisation can be severely hampered. There is a need to gauge Africa-wide’s organisations as opposed to country-specific diversity management and levels of maturity so that effective mechanisms can be explored. It appears most studies on organisations in Africa are guided by international practices that may have very little input from local practices (Booysen, Citation2007; Mbigi, Citation2000; Prime; Citation1999).

2.1. Research objectives

To explore workplace contemporary issues of diversity in Africa for development.

To ascertain challenges currently militating against diversity and development.

To locate international best practices that enhance management of diversity for development in Africa.

To identify suitable development solutions for diversity management in African organisations.

3. Diversity—a global view

April and Shockley (Citation2007) contend that the theoretical underpinning of diversity and workplace narrative have experienced significant shifts ever since the late 20th century. The thrust shifted from a legalistic slant of diversity from a country to an individual level. They further contend that the succeeding philosophical evolution will move towards inclusion. The 21st century has been characterised by cultural diversity as a growing phenomenon with increased attention and significance. Facts and trends testament to this include the globalisation of economies with the improved performance of the Asian continent, wherein the next 30 years, 50% of the worlds’ GDP is expected to be represented and the involvement of international teams as a key driving force of innovations (Holmgren & Jonsson, Citation2013). According to Insights (Citation2012), in 2010, the USA had 30% of its employees in the following categories; Asian (5%), African American (11%) and Hispanic/Latino (14%). A study by Herring (Citation2006) based on a survey that engaged 251 USA for-profit businesses revealed that those with greater racial diversity posted better financial performance results and remarkable developments. The United States Department of Commerce conducted a benchmarking study and detailed the following developmental critical success factors to evaluate best practice in diversity management (US, Citation2001, p. 3):

Leadership and the management’s commitment

The involvement of employees

Strategic planning

An investment that is sustainable

Indicators for diversity

Measurement, evaluation and accountability

The synchronisation of diversity management to organizational goals and objectives.

There are also some critical issues of this century that concern development, globalisation, international trade, accelerated international migration and diversity across borders (Stewart, Citation2007). As Thomas and Inkson (Citation2009) put it, one of the critical impacts of globalisation and migration is the dramatic increase in the opportunity and need to interact with people who are diverse in culture. Workforce shifts in Europe together with political and economic changes in the European Union have all paved way to highly mobile and diverse society that live and work within the European economic area (Allwood et al., Citation2007). Intercultural interactions are fast becoming a fact of life taking place regardless of individuals’ interests in acquaintances of other persons from a culturally different background promoting development. According to Parvis (Citation2003, p. 37), the thinking has therefore changed on cultural diversity from being a “melting pot” to “multiculturalism”, accepting it as an essential part of a society. These inferences testify to the fact that institutions will increasingly call for an internationally accomplished workforce and that the ability to manage the cultural diversity plays a major role in their success and development (Parvis, Citation2003; Stewart, Citation2007).

A case in point is Sweden, a country with a diverse population that has multi-lingual and ethnic groups as its inhabitants (Holmgren & Jonsson, Citation2013). Its cultural diversity is perceived as a societal fact, the country as noted by Roth and Hertzberg (Citation2010, p. 6) “consists of citizens/inhabitants with different cultural backgrounds.” Such an observation acknowledges the fact that the country has inhabitants from a multicultural background. However, this is not at all a surprising fact for a country that separated its church (Lutheran Church) from its state only in 2000 (Roth & Hertzberg, Citation2010, p. 6). The current population in Sweden is made up of 9.5 million out of which 1.4 million are foreign nationals. This translates to 15% of the total population according to the Statistics Central Bureau (SCB, Citation2013). The figure 1.9 million of the population in Sweden (20% of the total population) has a foreign background (people who are foreign-born or native-born with two foreign-born parents) (SCB, Citation2013).

Statistics reveal that the percentage of employees among people with non-Swedish backgrounds has decreased since 2001 (Näringsliv, Citation2013). Fifty-seven per cent (57%) men and fifty-three per cent (53%) women were employed by 2010. This is lower than the percentage from 2008, which revealed an employment rate of sixty per cent (60%) of the men and fifty-five (55%) of the women. However, the figures for 2010 were a little higher than 2009 where fifty-five per cent (55%) of the men and fifty-one per cent (51%) of the women were employed (Näringsliv, Citation2013).

On the other hand, the number of people with non-Swedish backgrounds among workers has increased from 2009 to 2010 with 0, 5% for women and 0, 6% for men (Näringsliv, Citation2013). Frisk (Citation2013) argues that these people are very important for the working environment in Sweden because some industries would have to close without them. The establishments of institutions, for instance, the Cultural Diversity Consultants in 2003 and Multicultural Centrum in the 1980s emphasise the cultural integration and management of the differences in Sweden as they strategically create programmes and networks to integrate people beyond their cultural differences.

This implies that development, expansion and globalisation are not all about countries but also institutions’ capability to be more accommodative to a heterogeneous working environment. Needless to say, whether it is international or domestic, cultural diversity influences how institutions perform (Adler, Citation1997, p. 97). It is against this background that Stevens and Ogunji (Citation2011) contend that an institution that effectively manages its cultural diversity succeeds with the well- deserved competitive edge while others lack.

Accordingly, “to manage effectively in a global or a domestic multicultural environment, we need to recognise the differences and learn to use them to our advantage rather than either attempting to ignore them or simply allowing them to cause problems” (Adler, Citation1997, p. 63).

Therefore, a multicultural environment should be managed to bring developmental advantages that may be latent at first sight.

4. Research gap in Africa

Kamoche, Siebers, Mamman, and Newenhan-Kahindi (Citation2015) observe that contemporary studies on cultural matters in Africa appear to be located in the realm of national culture. One such example is the “Ubuntu,” a phenomenon applied as a means to analyse cultural characteristics in Southern Africa like South Africa and Zimbabwe (Ramose, Citation2003). Well-known works of Hofstede (Citation1980, Citation1983) as well as Schwartz and Bardi (Citation2001) have neglected Africa’s diversity to a large extent. They treated African countries more as aggregated regions. Also, some global studies have tended to take a small number of African countries assumed to be illustrative of the continent. Samples obtained by Schwartz and Bardi (Citation2001) from 62 countries worldwide to make an analysis of value hierarchies across cultures have only included four African countries. Therefore, an impact analysis which is more integrated coalescing various individual countries in Africa on the cross-cultural business and management studies is not being fully realised (Kamoche et al., Citation2015). This study focuses on seven countries almost double the sample covered by Schwartz and Bardi (Citation2001).

But in South Africa, for instance, statistics revealed that White males were still over-represented in management while Black females were under-represented. Whites on the whole still constitute 57% in management. White males represent 41% of management with White females representing only 16%. Conversely, Blacks represent 27% of management with males constituting 20% and females only 7% (cited in Booysen, Citation2007).

Surprisingly, not much is to be found with respect to how institutions view and manage a culturally diverse workforce today for purposes of development. This is particularly evident in Africa’s working environment. Therefore, the lack of this type of research in the African context creates a possible area for study. It may, therefore, be interesting to conduct a research with the intention of investigating how it is represented in reality. Owing to this research gap, this study explores the need for more information in the management of cultural diversity in Africa for development.

5. Background and context of Africa

Nzelibe (Citation1986) argues that the advent of Europeans and later their departure made Africans become actors on a stage they had not set presenting challenges for African managers who continually had to grapple with the integration of African management thought based on Western management thought. On that note, Kamoche et al. (Citation2015, p. 331) corroborate and argue that “much remains to be done to develop indigenous forms of knowledge which are relevant to Africa and which address the needs of the African labour force.” They further contend that researchers seized with organisational issues in Africa have to avoid such approaches cited by Nzelibe in order to enhance a deeper understanding of the management of organisations in Africa’s developing economies.

In South Africa, the apartheid policy created a heritage of the uppermost levels of social inequality on the globe. The new government adopted employment equity and equality (Booysen, Citation2007). This added discriminatory tendencies racially and culturally in the workplace (Zulu & Parumasur, Citation2009). In Nigeria, the UNECA (Citation2011) observes that the 2008 APRM Report remarked that managing diversity has been both a scourge and a challenge for the development of many African countries. It has been a scourge because of the material, human and social costs of diversity-related conflicts. For instance, the 1983–2005 (second North-South) civil war of Sudan is said to have produced some 2 million deaths, 420, 000 refugees and over 4 million displaced (UNECA, Citation2011) and according to various human rights organisations, the Darfur conflict’s casualty figures were also estimated to be around 300,000 deaths and 1.5 million displaced (Qugnivet, Citation2006). The wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo caused over 5 million deaths between 1998 and 2003 while the genocide in Rwanda claimed over 800,000 lives (UNECA, Citation2011, p. 1).

In this study, diversity refers to the plurality of identity groups that inhabit individual countries (Deng, Citation2008). Identity refers to imagined or real markers (often socially constructed), which social groups attribute to others or to themselves so as to set themselves apart from others (we/they) and to distinguish one another from others. The markers for the distinguishing of identity groups are not static targets which are difficult to pin down. These can be classified into primordial (ascribed) and social categories (UNECA, Citation2011). Social identity (attained) markers can be formed across primordial markers while primordial markers constitute the network into which every child at birth finds itself to be a member. Both markers have either negative or positive bearing to institutional development depending on how they are managed.

Race, ethnic and religious identities are not confined to the jurisdiction of a given state. For instance, the Fulani people are spread over some 19 countries, the Hausa people are found in five countries, the Luo live in Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia and Tanzania whereas the Somalis are fragmented into four of the Greater Horn countries (UNECA, Citation2011).

6. Review of related literature

Landman (Citation2012) observes that in response to the unceasing challenges owing to societal and cultural segregation in present-day companies, there have been increased calls for greater cultural integration for development in recent years. These calls have been evident in countries like Australia and New Zealand (Johnston, Citation2002), Germany (Hanhorster, Citation2001), the USA (Brophy & Smith, Citation1997), UK (Berube, Citation2005), Netherlands (Geurs & Wee, Citation2006). The argument has been that mixed environs can support cultural diversity in companies while contributing to more sustainability and development (Jenks & Dempsy, Citation2005; Rogers, Citation1997; Talen, Citation2008). Cultural diversity is located within the jurisdiction of daily lives and described by Talen (Citation2008, pp. 4–5) as “places with socially diverse people sharing the same neighbourhoods, where diversity is the result of a mix of income levels, races, ethnicities, ages, and family types.”

This section provides some definitions of the subject in question. Later it delves on to how culture affects the development of institutions, including how it can create conflicts in organisations. Some issues behind the management of cultural diversity are reviewed in terms of the diverse popular views existing in the academic discourse. Although the views are diverse in nature, the focus is based on a specific approach that provides the basic tenets of managing cultural diversity for development.

6.1. Diversity

Landman (Citation2012, p. 54) argues that there are many interpretations of diversity. These range from a thrust on mixed social and ethnic groups (Hanhoster, Citation2001), diversity of economic opportunities and development and to a thrust on the corporeal elements that in essence promote cultural diversity (Talen, Citation2008). According to Nkomo and Cox (Citation1999, p. 88), diversity is a contested term with many different definitions of the concept, including some that are very broad. While many people merely refer diversity to race and ethnicity the concept includes more than that (Stevens & Ogunji, Citation2011). For Nkomo and Cox (Citation1999), some researchers even view diversity as broad as all differences that people have as individuals. Parvis (Citation2003) emphasises that diversity exists in every society and every workplace. He views diversity as including culture and ethnicity with differences located in physical abilities/qualities, languages, class, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, and gender identity (Parvis, Citation2003, p. 37). In his view, diversity brings great benefits, including development that enriches lives in many ways.

6.2. Cultural diversity

According to Varner and Beamer (Citation2011, p. 4), “Culture explains how people make sense of their world.” This appears to be too general but Seymen (Citation2006) is more explicit and describes culture as the way of life of a group of people being shared by all members. This is shared by Hofstede’s view on culture who views culture as the “software of the mind” that separates members of different groups from each other (Hofstede, Citation1991, p. 180). According to him, this software or mental programming is based on social environments where people grew up and developed their life experiences (Hofstede, Citation1991, p. 4, 180). Cox (Citation1993, p. 6) defines cultural diversity as “the representation in one social system of people with distinctly different group affiliations of cultural significance,” while national culture is part of cultural diversity and is defined as “the collective programming of the mind acquired by growing up in a particular country” (Hofstede, Citation1991, p. 262). This definition will be used in this study.

6.3. Cultures in organisations

Barney (Citation1986, p. 657) describes organisational culture as an abstract concept with many different definitions but defines it as “a complex set of values, beliefs, assumptions and symbols that define the way in which a firm conducts its business.” Organisational culture may have an impact on how an institution works with cultural diversity for development. Scott (Citation2011) wonders if for instance, organisations with inclusive cultures that in all procedures embrace diversity more likely than others to benefit in terms of development from cultural diversity. Research has revealed that culturally heterogeneous groups and culturally homogeneous groups present development advantages over the other in different contexts (Ely & Thomas, Citation2001, p. 234).

However, homogenous groups in Thomas’ study (1991) have shown that groups had higher performance in five different tested situations than heterogeneous groups. He showed that homogeneous groups tend to be more effective and developmental in situations with a complex context where heterogeneous groups fall short owing to perception and attribution differences as well as communication issues (Thomas, 1991, p. 257). Since members of heterogeneous groups have different experiences or backgrounds, they tend to have the potential to generate more diverse solutions to problems thereby developing and achieving higher quality results emanating from greater creativity (McLeod, Lobel, & Cox, Citation1996, p. 257; Thomas, 1991, pp. 257–258).

Although conflicts arise easier in heterogeneous groups, they can be more productive, developmental and creative in the long run with more generated ideas (McLeod et al., Citation1996, p. 257). It appears from this argument that none of these groups is superior to the other. It could be assumed that a company could benefit more from using both types of groups in different situations (McLeod et al., Citation1996, p. 257; Thomas, 1991, pp. 257–258). The notion of hatred towards the heterogeneous groups is detrimental to development as is the case in Africa. Adler (Citation1997) argues that oftentimes people view cultural diversity as something that will not benefit their organisation yet it can bring many developmental and progressive outcomes.

Africa has proved to be a well-resourced continent with another mother tongue of speaking mainly English. Therefore, African institutions/companies could be well equipped for cultural diversity and therefore, improved development. It is fundamental to learn about different cultures to recognise cross-cultural fertilisation of ideas (Parvis, Citation2003, p. 38). Many international business failures are owing to the fact that someone does not understand the reasons why people think or value the way they do (Varner & Beamer, Citation2011). This could also be an issue in African institutions because diversity is a broad concept that needs more research than what currently is there at the expense of development.

6.4. Managing cultural diversity for development- some perspectives

Cultural diversity’s presence in organisations is viewed as an increase of the level of creativity, development, in-depth analysis of issues, improved decision-making, and flexibility, innovation along with diversity in point of view, approaches and business practices (Adler & Gundersen, Citation2008; Cox & Blake, Citation1991; Stevens & Ogunji, Citation2011). While diverse cultural origination assures advantageous outcome in an organisation, cultural diversity may create conflicts, miscommunication, misunderstanding, increased tension and lack of cohesion with commitment having a negative effect on the organisation performance (Adler & Gundersen, Citation2008). Seymen (Citation2006, pp. 296–315) identifies five cultural diversity and management dimensions in an organisation in which cultural diversity is a tool for competitive advantage (dimension 1).

In dimension 2, the advantages of cultural diversity should be enhanced while the disadvantages are minimised. Dimension 3 suggests that diversity should be amalgamated into a homogeneous organisational culture while dimension 4 suggests universalism instead of multiculturalism and dimension 5 views cultural diversity as a human resource function. These will be tersely discussed below.

6.4.1. Cultural diversity as a developmental competitive advantage

Dadfar and Gustavsson (Citation1992) contend that the advantages of cultural diversity are affiliated to high performing organisations and provide proof that the performance of the organisation excels more in a heterogeneous environment than in a homogeneous environment. The major aim of increasing cultural diversity is to dominate pluralism for single-culture and ethno-relativity for ethno centralism (Daft, Citation2003). Ludlum (Citation2012, pp. 78–79) argues that “Ethno-relativity is accepting the fact that members of subcultures and dominant culture are equal while pluralism is embracing various subcultures of an organisation.” These two perspectives will together get the members of the organisation to identify with the organisation instead of being ignored. This increases their participation, development and job satisfaction while making them motivated. Herbig and Genestre (Citation1997, pp. 6–8) argue that the advantages of having a culturally diverse workforce would bring long-term corporate competitive advantage.

6.4.2. Cultural diversity as both positive and negative

In this dimension, both developmental and negative aspects of the cultural diversity in an organisation are viewed separately in which the advantages are highlighted and disadvantages are minimised (Adler & Gundersen, Citation2008). The observation by Montagliani and Giacalone (Citation1998) appear to be apt, that a mismanaged diversity may create psychological stress and ultimately a failure and an ineffective labour force. Higgs (Citation1996) notes that the practice of viewing cultural diversity as a difficulty and not as a source of competitive advantage and development needs to be changed.

6.4.3. Cultural diversity dominated by an organisational culture

The creation of a common culture is important where differences in culture residing in an organisation are not felt, rather with emphasis on developing a common cultural identity to achieve organisational goals. Person (Citation1999, p. 35) observes that cultures could be manipulated to create a desired dominant culture that is “both coherent in itself and dominant over other subcultures,” in which the dominant culture is the powerful organisational culture for development.

6.4.4. Universal culture instead of cultural diversity

This view (Seymen, Citation2006, p. 30) places emphasis on developing universally cultural values in a firm rather than a “single or common or dominant culture”. It is related to Trompenaars’ theory of “universalism” within a culture, which is operationalised when people believe that some rules and laws can be identified and applied to everyone for development (Trompenaars, Citation1993).

6.4.5. Cultural diversity as a human resource programme and its strategy for development

This dimension passes the responsibility of managing diversity to the human resource departments and its modern management techniques (Seymen, Citation2006, p. 307). This study was informed by this dimension. It places emphasis on the need for providing the multicultural workforce, in-service training programme and motivational pre-departure preparation programme as argued by Peppas (Citation2001). Managers of diverse cultural workforce ought to implement variable management, organisational behaviour techniques in order to “harmonise” the differences to achieve a common objective to enhance development (Wright & Noe, Citation1996, p. 75).

7. Research methodology

Raadschelders (Citation2011) argues that research is grounded on some underlying philosophical assumptions on what constitutes an authentic research. These philosophical assumptions also affect the choice of method that would gain the necessary knowledge in a bid to address the specific research topic. Therefore, the philosophy of a research is linked to the sources and development of knowledge in understanding the phenomena of the world. It guides the research informing the research strategy, data collection and analysis (Holden & Lynch, Citation2004). In order to critically grasp the interrelationship of the core components of the topic, a position of an interpretive approach with constructionist concerns was taken in this study.

The nature of the topic requires embracing the subjective meaning and interpretations behind cultural diversity in an institutional context. As part of epistemology, the core of interpretivism requires the researcher to interpret the subjective meaning of a social action (Bryman & Bell, Citation2011, p. 16) unlike the objective view as in positivism, which puts emphasis on natural scientific research methods that focus on measurable facts to study social reality. The choice of interpretivism and constructionism is justified by the following observation:

“Instead of culture being seen as an external reality that acts on and constraints people, it can be taken to be an emergent reality in a continuous state of constructions and reconstruction” (Bryman & Bell, Citation2011, p. 21).

The ever-evolving process of culture affects the emerging reality of cultural diversity, complicating its relationship with other concepts of the topic (Holmgren & Jonsson, Citation2013). Therefore, the appropriate research approach to the desired outcome was the qualitative one. It was of an exploratory nature and used the grounded theory approach. The grounded theory approach enabled the researcher to make informed decisions on the link between cultural diversity and development in Africa.

7.1. Sampling selection

A random sampling of seven countries from a population of 55 African Union countries was made. A purposive sampling of seven diverse senior managers from various huge companies was picked from these seven African countries. The choice of sampling was informed by demographic variations in terms of ethnic diversity. The main determinant of a sample size in qualitative research relates to the amount of data gathered. It is not essentially about the number of participants that one would like to have in the study. It is up until the data collection’s evident repetition of themes is reached, a phenomenon known as data saturation (Richie & Lewis, Citation2003). Therefore, the researcher did not decide the number of participants before-hand for including in the study, but only stopped the data collection process at a point when the analysis indicated that saturation had been reached. Primary data were collected through questionnaires administered online.

While considering the sampling method, there was a need to recognise the perceived or lived experiences of diversity management identified with the organizations in this regard. It comprised experienced both female and male participants aged between 30 and 65 years.

7.2. Sources of data

The secondary source of data was obtained through surfing the internet, books and other academic reports to acquire relevant information and included the integrated World Values Survey (WVS) dataset covering 1981 to 2014 and primary data from questionnaires administered online. A self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) was designed precisely to be completed by participants without the researcher’s intervention on collecting the data. The SAQ is a stand-alone questionnaire often used in conjunction with other data collection modalities determined by the researcher such as phone calls. The SAQs are being used extensively for Web surveys. The web-based questionnaire was developed using Blaise IS 4.8 software and completed only using a computer but not using a smartphone or tablet. The data collected from the web-based this questionnaire was saved in a database automatically.

7.3. Period of the study

The duration of the study was six months beginning from July to December 2017. In any research design, time is of essence. This, however, varies depending on whether the research is cross-sectional or longitudinal in nature (Creswell, Citation2009). In cross-section research, either the entire population or a subset thereof is selected, and from these individuals, data are collected to help answer research questions of interest. It is cross-sectional because the information about Y and X collected represents what is going on at only one point in time. This particular study was a cross-sectional research taking place at a single point in time. This implies that the researcher was taking a cross-section or “slice” of how diversity management was being done to enhance development for Africa. On the other hand, a longitudinal study would take place over time.

8. Tools used for research

Questionnaires were used in this study. They are usually paper-based or delivered online and consisting of a set of questions which participants are expected to complete. Questionnaires can be an invaluable tool when usability data is needed from large numbers of dissimilar users. They can be both cost-effective and easier to analyse than other methods. However, it must be understood that they suit some research questions better than others. Questionnaires are reasonably effective at obtaining data about what issues are of increased importance. They rely only on the respondents’ subjective memories as compared to the objective measures obtained in experiments. They require more effort and time in design and piloting.

9. Data analysis

Data were analysed by the use of ATLAS.ti. ATLAS.ti is a qualitative data analysis tool within computer-assisted data analysis software. In measuring heterogeneity, Powell’s group reactions model was used together with the alienation framework of Esteban and Debraj (Citation1994), which assumes that individuals feel antagonism towards people different from them (social antagonism). The Powell’s model postulates that institutions attempt to be pre-emptive on equity matters by noting the importance of a diverse workforce while acting autonomously from exterior legislative influences. Tables and below shows demographic data of participants.

Table 1. Demographic data for participants (N = 7)

Table 2. Demographic data for participants (N = 7)

These participants were drawn from big corporations but cannot be named here for purposes of anonymity in line with research ethical considerations.

These participants were drawn from big corporations but cannot be named here for purposes of anonymity and confidentiality in line with research ethical considerations.

10. Discussion of results

Findings suggest that while diversity management within organisations pivots around managing employment equity, true diversity pivots around the tenet of nurturing a culture of inclusiveness, acceptance and respect. Hays-Thomas in Stockdale and Crosby (Citation2004) support the same idea. Participants were solicited for their personal views on diversity management issues rather than in view of their respective companies, but most of their views were translated into institutional practices owing to their influence as diversity leaders. Even though diversity is often regarded as a source of competitive advantage (Knouse & Smith, Citation2008), this was not necessarily the experience from participants. For the management of cultural diversity to have positive outcomes, people involved have to participate extensively in making the situation work. It was the individual factor apparently missing from the theories on cultural diversity. For instance, if everyone who is involved in an institution is resolute on the belief that “my way is the best way”, it may present challenges to managing the situation positively. It would not be management alone that would make the effects of cultural diversity better. The individuals too should be involved, implying that cultural diversity outcomes are greatly dependent on individuals. People tend to have different approaches to situations and different behaviours in as much as they may share the same culture.

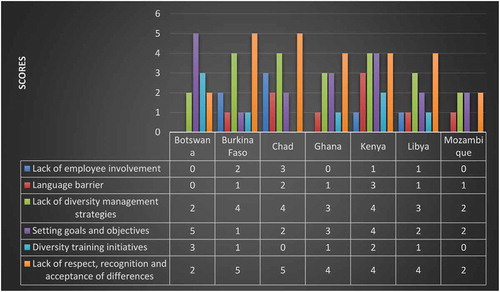

Shen, Chanda, D’Netto, and Monga (Citation2009) argue that for diversity management to be effective, structures have to be designed in a way to encourage employment of people from chosen social standing. In support of this, participants engaged recruitment practices that leverage streamlined processes and workforce transformation. Participants argued that where nobody held targets for equity against companies, results will not be easy to achieve. These sentiments are corroborated by Shen et al. (Citation2009) who advocated for monitoring diversity-related targets in companies. However, findings in this study contradict observations by Hayles and Russell (Citation1997) that a diverse workforce increases the ability for market competition. Responses instead indicate that workforce diversity only supports more diverse markets and not problem-solving efficiency as such. Theories on cultural diversity concur that creativity is high within heterogeneous groups and that communication works better in homogeneous groups (Booysen, Citation2007; Hofstede, Citation1991; Kamoche et al., Citation2015). But these assertions can be challenged. While theories show that the only way that decides how culturally diverse groups perform is how these groups are managed, it can be argued that individuals’ participation contributes a bigger role in such situations more than what the theories imply. However, creativity does not necessarily come automatically in a culturally diverse group and that communication can largely depend on the individual’s knowledge of languages and levels of proficiency. The findings agree to some extent with studies carried out in Ford Motors and Coca-Cola in Finland and Ghana respectively (Dike, Citation2013). Figure below shows a comparison by country on diversity management.

It is clear from the Figure that lack of employee management and language barriers were not diversity management issues in Botswana while for Ghana and Mozambique it was only lack of employee management. In Burkina Faso, Chad, Ghana, Kenya and Libya lack of respect, recognition and acceptance of differences was significantly high. This portrays a negative pointer towards the perception of strength in diversity for Africa’s development.

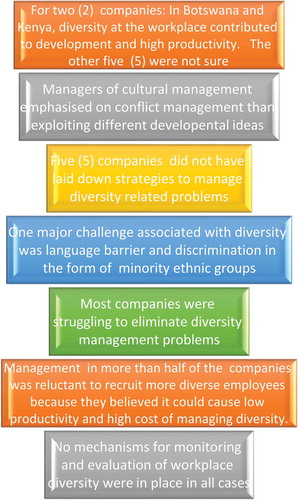

12. Major findings

Figure below shows a summary of major findings. Overall, results indicate that most African companies do not yet place value in the cultural diversity for their development. Such diversity is still viewed by many as counterproductive but some few institutions are beginning to appreciate it. There is no similar study that has been undertaken. The study reveals new knowledge to Africa’s development through its unique cultural diversity. It revealed that only a few companies (2/7) viewed cultural diversity in a positive manner and managed to attain synergies that enhance development. This is contrary to Trompenaars’ theory of “universalism” within a culture discussed above. These two companies are located in Botswana and Kenya. These two companies had a global attitude towards cultural diversity believing that they needed to accommodate cultural diversity to gain a competitive advantage while creating an open and flexible atmosphere. This finding concurs with the dimension that gives the responsibility of managing diversity to the human resource departments and its modern management techniques (Seymen, Citation2006, p. 307). All companies in the study believed that diversity brings an influx of different point of views but failed to underscore how this provides the prospect for development. Some managers whose responsibility was cultural diversity management did not recognise the differences in the employees’ views on the development of their entities. They focused more on conflict management emanating from diverging views. Results indicate that best practices appear in Botswana, Ghana and Kenya, although much better practices could have been shown. Mozambique presents a clearly unique status recording fairly low in almost all categories as revealed by these findings. Diversity training initiatives were more elaborate only in Botswana. Successful institutions accentuate on the importance of communication and appreciate the diverse individual views. This motivates individuals to manage diversity. Most of the institutions still lack the holistic view because they fail to articulate diversity at the strategic level and in all dimensions of the organisation. Also, most companies do not have integrated cultural diversity tacked into the organisational policy and procedures to represent diversity. Culturally diverse employees tend to have stronger feelings to “do your part” for the institution and promote innovation. Therefore, findings are summarised below in relation to research objectives set out above for development.

The findings are thus summarized above in relation to research objectives set out above for development.

11. Implications for African institutions

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, companies must monitor and evaluate performance management in Africa. There are some challenges that cultural diversity may bring to African institutions although the benefits are much higher than the problems if managed well, providing socio-economic value. It is important to include people with culturally diverse backgrounds in the discourse of how work is conducted in order to promote innovation and “made in Africa” policies. This may benefit all from their different experiences and ways of seeing things. As opined,

“It is therefore imperative that Africans everywhere, on the continent and in the diaspora, together with others who care for the people of this continent and humanity in general, come together to rid themselves (Africans and others) of the mind, identity and consciousness shackles that bind all of them” (April & Shockley, Citation2007, p. 1).

A holistic approach to cultural diversity integrated at all levels and dimensions of institutions could be created making organisations more heterogeneous. Cultural diversity is consequently about the development of additional opportunities for people in the closer vicinity. For that reason, Jacobs (Citation1961) argues that diversity is a component of successful institutions; without it, the institutional systems would not be that adequate to thrive. Talen (Citation2008) considers that institutional diversity is basically interconnected to institutional strength and social equity. Institutional strength is linked to economic health and sustainability. The implication also relates to social equity where access to the geography of opportunity and a mix of population groups are ideally measured as the foundation of a more inventive, stable and tolerant (Talen, Citation2008).

12. Conclusion

The study sought to investigate contemporary issues militating against diversity in Africa in order to contribute knowledge to diversity management in organisations. Findings indicate that diversity is critical and should not be left to management only but to include employees as it directly affects the performance of companies and impacts all people within. If diversity is managed well, benefits accrue not only to the organisations but for development to the rest of Africa. Contribution to theory is that both management and employees’ view towards cultural diversity is an important factor in how cultural diversity is treated. Cultural diversity must be infused in organisational strategic plans and not to be relegated to some individuals alone. Those managers that believe in diversity tend to highlight more on the advantages while the ones that do not, tend to stress on the challenges. Cultural blindness is an existing state for some managers in organisations. The findings agree to some extent with studies carried out in Ford Motors and Coca-Cola in Finland and Ghana respectively (Dike, Citation2013). For policy, teaching and society, African institutions need to integrate diversity at their managerial levels and in their strategic plans in as much as they are trying to do with gender equality at the moment. This must include the monitoring and evaluation of diversity management. Africa must make cultural diversity an intrinsic part of institutional value system and identify it as an asset to utilise it towards the progress of the continent.

12.1. Recommendation for further research

While it may not be easy to generalise the findings of this study to the entire continent, further research would be useful to investigate the relationship between managers’ view on cultural diversity and its influence on the management of cultural diversity in other African countries not represented in this study. Many HR directors from the same countries in different companies may be a starting point. If the relationship is identified to be quite strong between these two factors (cultural diversity and development), this could prompt further research, which may provide more insights into the influence that the relationship portrays.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Chigudu

Daniel Chigudu as a special interest in development and governance research.

References

- Adler, N. (1997). International dimensions of organizational behavior. Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western College Pub.

- Adler, N., & Gundersen, A. (2008). International dimensions of organizational behaviour. New York, NY: Thomson Learning Inc.

- Allwood, J., Lindström, N. B., Börjesson, M., Edebäck, C., Myhre, R., & Voionmaa, K. (2007). European intercultural workplace: Sverige, projektpartnerskapet European intercultural. Sweden: Leonardo Da Vinci, Kollegium SSKKIIGöteborg University.

- April, K., & Shockley, M. (2007). Diversity in Africa: The coming of age of a continent. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665.

- Beaty, D., & Booysen, L. (1998). Managing transformation and change. In B. Swanepoel (Ed.), South African human resource management: Theory and practice (pp. 725). Cape Town: Juta.

- Berube, A. (2005). Mixed communities in England: A US perspective on policy and prospects. New York, NY: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Booysen, L. (2007). Managing cultural diversity: A South African perspective. In K. April & M. Shockley (Eds.), African Perspectiveica. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved March 07, 2018, from doi:10.1057/9780230627536_5

- Brophy, C., & Smith, R. (1997). Mixed income housing: Factors for success. Cityscape. Journal of Policy Development and Research, 3(2), 3–31.

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2011). Business research methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cox, T. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

- Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. (1991, August). Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. The Executive, 5(3), 45–56.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dadfar, H., & Gustavsson, P. (1992). Competition by effective management of cultural diversity: The case of international construction projects. International Studies of Management and Organisation, 22(4), 81–92.

- Daft, R. L. (2003). Management. London: Thomson Learning.

- Deng, F. M. (2008). Identity, diversity, and constitutionalism in Africa. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Dike, P. (2013). The impact of workplace diversity on organisations. Retrieved March 03, 2018, from https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/63581/Thesisxx.pdf

- Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity at work: The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(6), 229–273.

- Esteban, J., & Debraj, R. (1994). On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica, 62(4), 819–851.

- Frisk, E. (2013). Många nya jobb går till utlandsfödda. Svenskt näringsliv. Retrieved from http://www.svensktnaringsliv.se/fragor/integration/manga-nya-jobb-gar-tillutlandsfodda_181707.html

- Geurs, K. T., & Wee, V. (2006). Ex-post evaluation of evaluation of thirty years of compact urban development in the Netherlands. Urban Studies, 43, 139–160.

- Hanhoster, H. (2001). Whose neighbourhood is it? Ethnic diversity in urban spaces in Germany. GeoJournal, 51, 329–338.

- Hayles, V., & Russell, A. (1997). The diversity directive: Why some initiatives fail and what to do about it. Chicago, IL: Irwin/ASTD.

- Herbig, P., & Genestre, A. (1997). International motivational differences. Management Decision, 35(7), 562–567.

- Herring, C. (2006). Does diversity pay? Racial composition of firms and the business case for diversity. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, August 11, Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Montreal Convention Center.

- Higgs, M. (1996). Overcoming the problems of cultural differences to establish success for international management teams. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 2(1), 36–43.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2), 75–89.

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Holden, M. T., & Lynch, P. (2004). Choosing the appropriate methodology: Understanding research philosophy. Marketing Review, 4(4), 397–409.

- Holmgren, D., & Jonsson, A. (2013, May). Cultural diversity in organizations: A study on the view and management on cultural diversity. Umea University.

- Insights. (2012). Diversity & inclusion: Unlocking global potential-global diversity rankings by country, sector and occupation. New York, NY: Forbes.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York, NY: Vinatge Books.

- Jenks, M., & Dempsy, N. (2005). Future forms and design for sustainable cities. Oxford: Architectural Press.

- Johnston, C. (2002). Housing policy and social mix: An exploratory paper. Prepared for Shelter NSW, Sydney, Australia. Retrieved July 6, 2018, from http://www.shelternsw.infoxchange.net.au/docs/

- Kamoche, K., Siebers, L., Mamman, A., & Newenhan-Kahindi, A. (2015). The dynamics of managing people in the diverse cultural and institutional context of Africa. Personnel Review, 44(3), 330–345. doi:10.1108/PR-01-2015-0002

- Knouse, S., & Smith, A. (2008). Issues in diversity management. Internal report for the defense equal opportunity management institute. Louisiana: Department of Management University of Louisiana.

- Landman, K. (2012). Urban space diversity in South Africa: Medium density developments. Open House International, 37(2), 53–62.

- Ludlum, M. (2012). Management and marketing in a New Millennium. Mustang Journal of Management and Marketing, 1, 1–153.

- Mazur, B. (2010). Cultural diversity in organisational theory and practice. Journal of Intercultural Management, 2(2), 5–15.

- Mbigi, L. (2000). In search of the African business renaissance. Randburg: Knowledge Resources.

- McLeod, P., Lobel, S., & Cox, T. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity. Small Groups Research, 27(2), 248–264.

- Montagliani, A., & Giacalone, R. (1998). Impression management and cross-cultural adaption. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(5), 598–607.

- Näringsliv, S. (2013). Antalet förvärvsarbetande ökade med 205 000 mellan 2001 och 2010. Svenskt näringsliv. Retrieved September 28, 2017, from, http://www.svensktnaringsliv.se/multimedia/archive/00035/utrikesf_dda_arbete_35345a.pdf

- Nkomo, S. M., & Cox, J. T. (1999). Diverse identities in organizations. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. Nord (Eds.), Managing organizations, current issues (pp. 88–106). London: Sage Publications.

- Nzelibe, C. (1986). The evolution of African management thought. International Studies of Management and Organisation, 16(2), 6–16.

- Parvis, L. (2003). Diversity and effective leadership in multicultural workplaces. Journal of Environmental Health, 65(7), 37.

- Peppas, S. (2001). Subcultural similarities and differences: An examination of US core values. Cross Cultural Management, 8(1), 59–70.

- Person, G. (1999). Strategy in Action. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

- Prime, N. (1999). Cross-cultural management in South Africa: Problems, obstacles and agenda for companies. Retrieved March 5, 2018, from http://marketing.byu.edu/htmlpages/ccrs/proceedings99/prime.htm

- Qugnivet, N. (2006). The report of the international commission of inquiry on Darfur: The question of genocide. Human Rights Review, 7(4), 38–68.

- Raadschelders, J. N. (2011). The future of the study of public administration: Embedding research object and methodology in epistemology and ontology. Public Administration Review, 71(6), 916–924.

- Ramose, M. (2003). The philosophy of Ubuntu and Ubuntu as a philosophy. In P. Coetzee & A. Roux (Eds.), The African philosophy reader (pp. 230–238). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Richie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE Publications.

- Rogers, R. (1997). Cities for a small planet. London: Butler and Tanner Ltd.

- Roth, H., & Hertzberg, F. (2010). Tolerance and cultural diversity in Sweden. Accept pluralism. Florence: European University Institute.

- SCB. (2013). Födda i Sverige – ändå olika? Betydelsen. SCB Website. Retrieved September 28, 2017, from http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/BE0701_2010A01_BR_BE51BR1002.pdf

- Schwartz, S., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a seminaries perspectives. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 268–290.

- Scott, C. (2011). Measuring the immeasurable: capturing intangible values. In Marketing and public relations International Committee of ICOM. Brno, Czech Republic: ICOM.

- Seymen, O. A. (2006). Cross cultural management. An International Journal, 13(4), 296–315.

- Shen, J., Chanda, A., D’Netto, B., & Monga, M. (2009). Managing diversity through human resource management: An international perspective and conceptual framework. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(2), 235–251.

- Stevens, R., & Ogunji, E. (2011). Preparing business students for the multi-cultural work environment of the future: A teaching Agenda. International Journal Of Management, 28(2), 528–544.

- Stewart, V. (2007). Becoming Citizens of the World. Educational Leadership, 64(7), 8–14.

- Stockdale, M., & Crosby, F. (2004). The psychology and management of workplace diversity. Boston, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Talen, E. (2008). Design for diversity: Exploring socially mixed neighbourhoods. Oxford: Architectural Press.

- Thomas, D. C., & Inkson, K. (2009). Cultural intelligence: Living and working globally. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Trompenaars, F. (1993). Riding the waves of culture. London: Economist Books Publishing.

- UNECA. (2011). Diversity management: Findings from the African peer review mechanism and a framework for analysis and policy-making. Addis Ababa, Ethopia: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa: Governance and Public Administration Division.

- US. (2001). Vice President Al Gore’s national partnership for reinventing government benchmarking study, 2001. Best practices in achieving workforce. New York, NY: United States Department of Commerce.

- Varner, I., & Beamer, L. (2011). Intercultural communication in the global workplace. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies.

- Wright, P., & Noe, R. (1996). Management of organizations. New York, NY: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

- Zulu, P., & Parumasur, S. (2009). Employee perceptions of the management of cultural diversity and workforce transformation. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 35(1), 9.