Abstract

There is an inextricable link between biological and cultural diversity, captured in the concept of biocultural diversity, whereby the former (genes, species, and habitats) co-adapt with the latter (knowledge, values, beliefs, practices and institutions). Sacred natural sites are increasingly considered showcases for the conservation of biocultural diversity, because their strong cultural importance derives from, and requires maintenance of, biodiversity. The research described in this paper is concerned with the conservation of the threatened “yellowwood” tree (Afrocarpus falcatus) in sacred natural sites of Sidama, southwest Ethiopia. Mixed methods were used to document types of sacred forests sites and the extent and distribution and dominance of A. falcatus in these, to identify drivers of endangerment of A. falcatus and other native woody species in Sidama, Ethiopia and to understand local explanations for the importance and maintenance of these sites. The results suggest that species such as A. falcatus owe their continued existence to resilience of ancestral tree-based rituals within informal protection areas and at homesteads and communal areas. Thus, the maintenance of an ancestral value system serves as an important motivation for the conservation of A. falcatus and other threatened native woody species.

Public Interest Statement

Biological diversity and cultural diversity are very much linked and one influence and shapes the other. Scientists call this interdependence biocultural diversity. Sacred natural sites, places that are holy and set apart for special, often spiritual uses and relevance, contain natural objects such as forests are increasingly considered contexts wherein biocultural diversity is conserved. Trees such African yellowwood are one of the important tree species commonly preserved in sacred sites for their cultural importance. On the other hand, sacred sites face endangered due to various human influences. The research described in this paper is concerned with the conservation of the threatened “yellowwood” tree in sacred natural sites of Sidama, southwest Ethiopia. Mixed methods were used to document these places and conservation of yellowwood trees in Sidama, Ethiopia. The results suggest that species such as A. falcatus owe their existence to ancestral tree-based rituals within informal protection areas.

1. Introduction and background

Since the 1960s, interest in the spiritual and social dimension of sacred natural sites (SNS) and the roles they play in conservation of both biological and cultural diversity has been gaining recognition (Sponsel, Citation2008). A body of theoretical literature setting out the conceptual framework for the interface between biodiversity and cultural diversity has been growing from both the social science and conservation biology perspectives. An important framework emerging from this is biocultural diversity, a concept which sees an inextricable link between biological and cultural diversity, whereby the former (genes, species, and habitats) co-adapt and are interdependent with the latter (knowledge, values, beliefs, practices and institutions) (Maffi, Citation2010; Loh & Harmon, Citation2014; Sponsel, 2013). Related conceptual frameworks of historical ecology and cultural landscapes that explain the historical and cultural embeddedness of physical places (Balee, Citation2006; Citation1998; Chouin, Citation2002) are incorporated in the concept of biocultural diversity. Biocultural diversity conservation as a concept and approach to conservation emerges from this context, and it emphasizes that conserving biodiversity without giving attention to people and cultural diversity is a disservice to the millennia of faithful, inextricable co-evolution (Loh & Harmon, Citation2014; Sponsel, Citation2013a).

Figure 2. Map of Sidama, Ethiopia (Source: Bureau of Finance and Economic Development, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State-SNNPRS of Ethiopia).

Sacred natural sites, deriving their sacredness from social construction (Schaefer, Citation2003), are places that center on natural and man-made entities. They are epicenters of local ecology, community life, livelihood and belief (Sponsel, Citation2008). They occupy a key place in the biocultural diversity conservation debate and are increasingly recognized as showcases for the conservation of biocultural diversity, because their strong cultural importance derives from, and requires maintenance of biodiversity (Maffi & Woodley Citation2010; Sponsel Citation2013a). Eighty percent of the world’s high biodiversity areas are reported to overlap with sacred ancestral lands, claimed or managed by indigenous peoples and local communities (Sobrevila, Citation2008; Toledo, Citation2013).

However, SNS, custodian communities and their environments and livelihoods are increasingly endangered (Igoe, Citation2004; Johnston, Citation2006; Verschuuren, Wild, Mcneely, & Oviedo, Citation2010). In Ethiopia biocultural diversity erosion exists; sacred sites, trees and useful ancestral traditions supporting these are endangered due to multiple factors. The country’s status as a center of biodiversity with an estimated 6500–7000 plant species of which 12% are endemic and a number of endemic animal species (EIB, Citation2014; Negash, Citation2010; Tadesse, Citation2012) is under threat. So is its status as one of the most culturally diverse nations of the world with about 80 ethnic groups speaking close to 154 dialects (Kibrework, Citation2011; Vaughan, Citation2003). (This sentence is too long, consider splitting)

Ethiopia’s native tree species and the rich diversity of traditional knowledge, beliefs, and practices based on these trees, are increasingly in a precarious state. The African yellowwood tree (Afrocarpus falcatus) is native to east, south-east and southern Africa, including Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, Swaziland, South Africa, and Mozambique. It can be considered a major native tree species, and while an IUCN-commissioned study (Vivero, Ensermu, & Sebsebe, Citation2006) does not include A. falcatus in its 117 Threatened and Near Threatened trees and shrubs of Ethiopia, it is on the list of national priority trees facing endangerment in Ethiopia (BIE Citation2014). The species also has protected status in South Africa (Lorraine, Citation2013), but its widespread distribution means that it is categorized as Least Concern globally by the IUCN (IUCN, Citation2011).

Due to their high timber and other economic values, the keystone tree species of Ethiopia have suffered a heavy loss over the past decades. Much of the forest cover of Ethiopia which was estimated at 40% at the turn of the twentieth century declined to less than 4% in the 1990s (Negash, Citation2010; Vaughn Citation2010) although since then, as most recent assessments show, attempts have been made to increase the cover to 10% (BIE Citation2014). The 100-year period from 1880s to 1990s was regarded as the century of deforestation and the heaviest blow happened especially during the 1940s and 1950s when commercial sawmills were introduced and expanded, heavily utilizing A. falcatus (Negash, Citation2010). (be consistent in stating % whether spaced or non-spaced)

The purpose of this paper is to describe how this nationally threatened tree, along with other selected native woody species, is conserved in the context of SNS. The research took place in southwest Ethiopia in an Abbo Wonsho community of Sidama, one of the country’s 85 ethnic groups. The study intends to demonstrate that the continued existence of locally threatened African yellowwood trees is linked to the conservation role SNS play in the study localities, thereby showcasing the relevance of the SNS in the conservation of plant species in Ethiopia and beyond.

The main objective of the study was to investigate the role SNS play in conserving locally endangered plant species in general and A. falcatus in particular by:

documenting types of sacred forests sites and the extent and distribution and dominance of A. falcatus in these;

identifying drivers of endangerment of A. falcatus and other native woody species in Sidama, Ethiopia and assess the extent to which these are linked to culture;

documenting the mechanisms and biocultural interface by which sacred sites and associated institutions contribute towards conserving endangered tree species such as A. falcatus; and

suggesting ways of capitalizing on the positive roles SNS institutions play in biodiversity conservation in Ethiopia and beyond.

2. Materials and methods

A qualitative approach was used and the methodological goal was to gain an in-depth understanding of the perspectives of local people. The design for data generation and analysis broadly followed a mixed-methods model, whereby an assortment of qualitative and semi-quantitative data collection and analytical tools were employed. The data were collected over a year of fieldwork (July 2012-June 2013) utilizing multi-scale, multi-stage, purposive sampling of sites, localities, households, and people.

Selection of study sites, localities, households, and informants was generally purposive though there was a limited element of randomness in recruiting households for the questionnaire survey. Thus, seven localities, called qebeles (sub-districts) were selected purposively due to, among other things, their association with many sacred sites compared to other areas and also their relative accessibly. Local informants representing various socio-demographic categories as well as interviewees representing organizational bodies across the spatial scales were recruited on the basis of their relevance to the study problem. Referral or snowball sampling was employed to identify and interview informants (particularly at local scale) who commanded important influence and were reported as holders of valuable information but were hard to identify. The household survey was administered by deploying, under the supervisorial role of my research assistant and myself, 10 trained data collectors. Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, United Kingdom. Informed consent and research approval were obtained through an official order letter from Sidama Zone Administration Office, Ethiopia.

The quality of fieldwork process and products was ensured through a range of measures; data management and analysis tasks were handled through the use of Express Scribe and NVivo 10 and SPSS 20/21, respectively, for qualitative and household survey data.

3. Study area

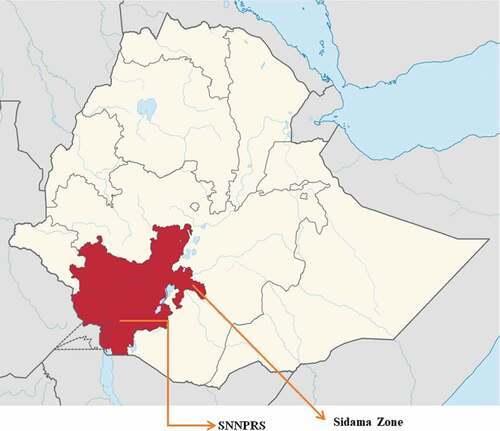

The Sidama are a Cushitic people of southwest Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa (Braukämper, Citation1978; Hamer, Citation2007), with an estimated population size between 3 and 4.5 million (CSA, Citation2013). The land is located some 275 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the national capital (Figure ).

Figure 1. Map of Ethiopia, showing Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State SNNPRS & Sidama Zone (Credits: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File).

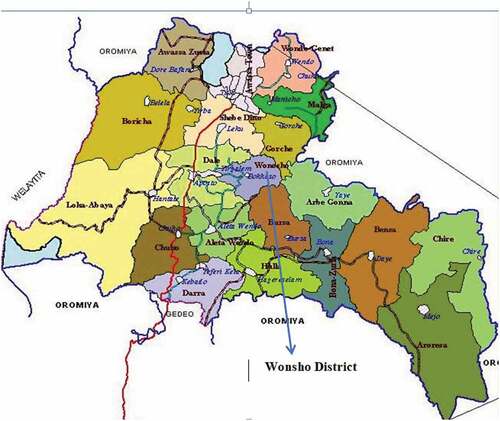

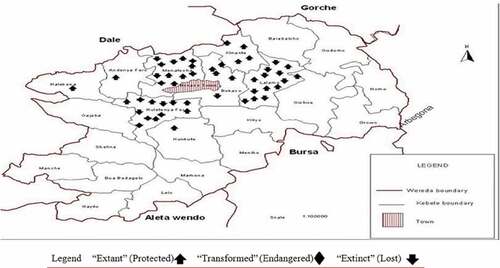

Sidama has a total land area of ca. 7200 km2, characterized by varieties of topographic, climatic and agro-ecological features. The Great East African Rift Valley divides the land into two, the western lowlands and eastern highlands (Figure ).

The Wonsho District where the fieldwork was conducted is one of 23 sub-divisions located in the south-eastern part of Sidama (the district should stand out on the map and coordinates included on the mainframe). It is located at 06°45′11′′N and 38°30′16′′E and is approximately 45 km from Hawassa, the zonal and regional capital (Figure ). Wonsho topography and agroecology are characterized as cooler and to some extent milder compared to other districts in Sidama, as the district lies in the highland area, east of the Ethiopian Rift Valley. Its altitude ranges from 1978 masl (west, lower end) to 2149 masl (east or upper end) above sea level (Moges, Dagnachew, & Yimer, Citation2013) (Include Digital Elevation Model data on the map to enhance clarity of your descriptions). The local botanical environment, ecology and agricultural landscape is rich in a diverse and dense floristic community, from massive, high-growing native trees such as dagucho (A. falcatus) to the ubiquitous bardaffe (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), as well as other recently introduced exotic trees. These trees serve multiple and complex needs including firewood, aesthetics and ornamentals, herbal medicine, shade for crops, animals and humans, soil fertility management, income sources and as a food security supplement.

4. Results

4.1. Distribution and types of SNS in Wonsho Sidama, Ethiopia

A typology of SNS in the study communities may be a useful tool to conceptualize and analyze the nature, current status and geographical distributions of sacred sites. The sacred sites of Sidama documented in this paper are cultural landscapes rather than virgin wildernesses. They are the results of conscious human (i.e. the custodian communities) actions of validating, defining, managing and protecting the forests. Some of the larger sacred forests, however, such as the flagship Abo Wonsho Sacred Forest, a 90.2 hectare forest well known throughout the Sidama land and in the Region as a whole, were initially not planted or cultivated in any conscious planning. Locals believe that such sacred forests just emerged by an action of divine working and will on places where founding ancestors died and were buried. Such local beliefs are anthropologically relevant, though not empirically, as they form the basis for traditional governance and “spirit-policing” of sacred forests.

A typology of SNS may be based on a number of models or criteria. One model used in this study is spatial scale combined with kinship structures and ownership regimes. Accordingly, SNS at lower scale of clan structure may be termed as mine’e ha’ara, “household sacred groves”. These are places where one socio-culturally and ecologically key native woody tree, usually, A. falcatus, planted by past or present household heads, is protected as a sacred reminder and symbol connecting father-son generation. Both the site and the trees are sacred due to their ritual and ancestor-symbolism significance. Further, they serve as social status indicators; and provide aesthetic, recreational, meditative, shade, shelter and wind break functions. Danawwa or songoharra are SNS that are collectively owned and managed, which may also include any collectively owned land irrespective of its sacredness. These sites often saliently include burial places of distant ancestors. The highest scale may be designated as gossa ha’ara, the SNS centering on the body of the apical founding ancestor; Abo Wonsho Sacred Forest is such a place. Of the 26 extant sacred sites, the majority (about 20) were small-scale (mine’e ha’ara); four were danawwa or songoharra and only one, the flagship sacred forest, was truly large-scale site, serving as the epicentre for all people that trace their allegiance to the founding ancestor of the clan.

The Functional Model is the second one used in this study. According to the underlying and practical functions for which a SNS is maintained, the study categorizes SNS into household shade trees, ancestral burial sites or graveyards, gudumales (ritual-meeting arenas) and luwaa (initiation grounds). Of the 26 extant sacred sites, two were luwaa sites, one was a gudumale and the rest (23) were ancestral burial places, both historical and contemporary. Keeping native trees for shade in the frontyards of households is a valued practice in Sidama. A native tree, mostlyA. falcatus, is planted and maintained with the manifest function of shade, shelter, resting and recreational space for households. Its latent function is to reinforce kinship identities and connections. In some instances, such trees are inherited from fathers to sons and they are maintained until they fall down due to old age. They also function as palaver trees, whereby a range of neighbourhood and kinfolk issues are discussed and settled.

The other dominant function is using these spaces as burial sites, grave markers, demarcations and protection instruments. Individual households can maintain these in their backyards; a group of households, members of sub-clans and clans in general also collectively own and manage them as places where their common ancestors are buried. Ancestors are placated at these sites, where A. falcatus are dominantly protected as ancestor- symbolizing objects; physical identifiers for the burial site; household worship venues and live-fence enclosure providing demarcation and protection. The trees generate their sacredness from the epicentre: the ancestral burial mound.

Luwaa sites are mini-forest places serving as initiation grounds where a valued age-grading rite of passage takes place. Gudumales are multipurpose spaces for communal events, New Year celebrations, collective rituals and other social activities. They could be owned and managed by individual households or collectively. There were two extant (albeit degraded such SNS at the time of the fieldwork in the study area.

Protection status is a third model, and based on this approach, Sidama SNS may be classified into “extant”, those that exist currently, despite pressures on them; “extinct”, sites that have disappeared because of a variety of factors; and “transformed”, sites which have been exposed to varying degrees of transformations, both physically and ideologically, existing in a wholly or partially degraded state. In a few cases, these transformed sacred sites may still physically exist, but they will have lost their underlying ideological purpose. They no longer serve as places of ancestor worship. Devoid of their spiritual aura, they may continue as mere “social” trees. The study categorized a total of 26 SNS in the “extant”; eight in “transformed” and 14 in “extinct” categories, making a total of 48 SNS.

The identified SNS, thus typified according to these three models, ranged from as recent as 29 years old to as old as about 375 years, based on local understandings and renderings of genealogical counts. While most surveyed SNS (N = 48) were few centuries old, existence of a 29-year-old sacred grove is a demonstration of the dynamism of SNS which are characterized by a definite locally rich historical ecological context.

4.2. Dominance and conservation of A. falcatus in the SNS of Wonsho-Sidama Ethiopia

Across all the different SNS categories, A. falcatus constituted the dominant protected tree species, ranging from a lone, sacred, totemic tree at a household front yard, to the uncountable dense forest of such trees at the major SNS of AWSF. Accordingly, in all inventoried cases, the tree was observed as the main protected species at household front-yards, their numbers ranging from an individual tree to a group of usually three to five in varying stage of maturity, in most cases being fully grown and often old. Similarly, ancestral graveyards of a household or group of households are invariably marked by these trees. Their number in our observed and inventoried cases, ranged from one to 12.

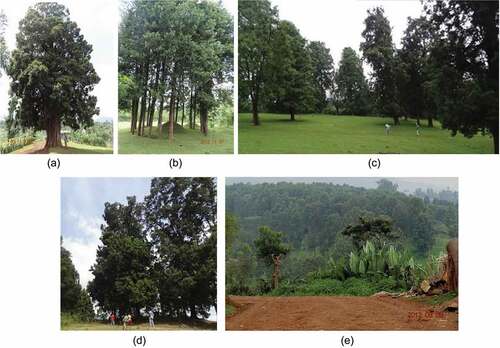

Furthermore, gudumales (public ceremonial and festivity conducting venues), were observed to be notably marked by A. falcatus, sometimes intermixed with other culturally and socio-economically salient native trees such as Olea africana capensis, Cordia africana, Ficus vasta and, Olea europae. These are, however, more likely to be overshadowed by the preponderance of A. falcatus. At one of our case study SNS of gudumales (Figure )), an inventory yielded about 27 individual A. falcatus dominating the other 17 species of native woody trees that were present. While the podo trees can visibly be dominant (as shown in the picture, the other species were mostly limited to one or two stands, except the ubiquitously pervasive exotic Eucalyptus which constituted over several hundreds.

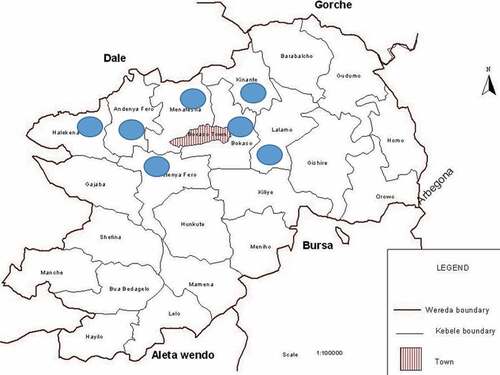

Figure 4. Distribution and conservational state of SNS in studied localities, July 2012-Jan 2013, Wonsho, Sidama, Ethiopia (Base map source: Sidama Zone- Agriculture and Natural Resource Department, March 2012, Hawassa, Ethiopia) Integrate this in the main map.

A similar inventory at one of the two existing mancholuwa (forest grounds for age-grade initiation rituals) yielded about nine woody tree species, dominated by A. falcatus. Based on the inventory, there were 75 A. falcatus, a single specimen each of O. europae, Olea capensis spp, F. vasta, and Junniperus procera; about five specimens of Borassus aethiopum, a few Croton macrostachyus and numerous smaller shrubs such as sţeberako (Bersama abyssinica), tontoncho (Plectranthus igniarius), haţabicho (Brucea antidysentrica), and various herbs.

The most salient of Wonsho Sidama SNS in terms of the protection of A. falcatus was, as noted above, AWSF. This site occupied the highest spatial, organizational and socio-cultural scale, with its 90.6 ha area. It serves as the epicenter for entire conglomerates of clansmen descending from the founding ancestor, Abbo, traced to about 350–400 years ago based on genealogical calculations. AWSF is a haven for many now locally endangered native trees which are of multi-purpose importance in local livelihood, culture, and ecology. A partial inventory of the site recorded about 133 tree species, including 22 locally reported endangered native trees, of which 10 were reportedly found nowhere else. Afrocarpus falcatus was the dominant species found at this SNS, forming a significant standing island of dense forest in otherwise deforested surroundings that characterise much of the land in Sidama and elsewhere in the country.

5. Drivers of endangerment of A. falcatus and other woody species in Sidama

The main reason for the resilience of the extant sacred forests is saliently linked to the persistence of some custodians in holding to the core ancestral religion. Thus, most of the extant sacred forests were linked with the practice of traditional religion. A participant of a local technocrats’ focus group noted: “Those who adhere to Sidama ancestral religion believe that ancestral spirits reside on trees; those who do not are not afraid of any spirits and they easily cut trees and use them for their immediate needs. Therefore, in most cases, it is those who adhere to Sidama ancestral religion who these days have managed to own sacred groves in their backyards and on the graveyards (Officers, SCRBO, Citation2012)”. Extinction of sacred forests was due mainly to former custodians converting to a new religion and cutting their sacred trees and transforming them to an agricultural land; in many cases, the processes of urbanization, and “development” related activities (schools, market places, roads, etc.) account for the extinction.

Findings from the household survey illustrate that maintenance of household sacred sites was varied across religious lines (Table ). In the household survey, 141 respondents (70.5%) of sample households (n = 200) were Protestant while 24% (48) adhered to ancestral religion. Maintenance of sacred groves was directly associated with the practice of ancestral religions. Respondents were asked whether they maintained a grove for non-economic purposes and adherents of ancestral religion were found more likely to engage in non-social driven maintenance of trees.

Table 1. Religious affiliation & maintenance of trees for noncash purposes among surveyed households, HHS September 2012, Wonsho

The Sidama Ancestral Religion (SAR) was identified as the core of the origin, social organization, governance and geography of SNS, attested by the fact that 22 of the 48 surveyed SNS were protected by SAR practitioners. The rest (those SNS not protected by practitioners of SAR) were either lost or transformed.

Amidst the resilience of sacred forests and ancestral traditions, there exist threats. These threats affect both biodiversity and cultural diversity. They emanate from both internal and external processes and are both natural and anthropogenic. Discussion with local people and reviews of local archives show eroding factors, especially external ones, have been intensifying since the 1890s, but momentum has increased over the past 50–60 years, with salient drivers being the introduction of cash economy, modern religions, modern education, misguided state policies, rapid population growth, and resultant socio-economic pressures.

Local people particularly highlighted population increase and conversion to Protestant Christianity as two key factors. Population increase and the attendant socio-economic pressures (increasing land shortages, increasing cost of living, for example) were reported as key drivers that often lead households to encroach upon the lands heretofore reserved for scared forest sites. In our observation across the surveyed sacred sites, there was evidence of locals engaging in encroachment activities.

Cultivation near sacred sites was common. There was a general understanding among the community that, for example, the original size of the Abo Wonsho Sacred Forest Site was very large compared to the current size. Population growth was a key driver leading to shrinking of the land size of the sacred places. Agricultural activities and other socio-economic and developmental needs have completely transformed many of the previous sacred forest areas in the studied communities.

5.1. Biocultural interface

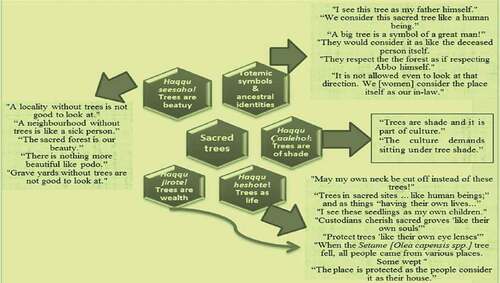

Local models of the inextricable link between culture and biodiversity are best realized in a range of aphorisms identified during the fieldwork regarding how sacred forests and individual sacred trees were conceptualized (Figure ).

Figure 5. (a). A sacred A. falcatus at the household front yard, Wonsho, Ethiopia, November 2012. (b). A SNS of 12 A. falcatus, making the shape of a ring surrounding a household ancestral grave sacred, November 2012, Wonsho-Sidama, Ethiopia; (c). Sacred A. falcatus at a household-based gudumales, Wonsho-Sidama, Ethiopia, January 2013; d. Mancho Luwaa, an SNS for age-grade intuition rituals, January 2013Wonsho-Sidama, Ethiopia; e. A view of Afrocarpus falcatus forest at Abbo Wonsho SNS, August 2012, Bokaso, Sidama, Ethiopia

Sacred forests and cultural keystone trees were viewed as “life”, “beauty”, “wealth”, “shade”, and “ancestor symbolisers”, among others. In such local aphorisms lie the biocultural interface that creates a favorable framework for the conservation of biodiversity (including A. falcatus) and associated values (Figure ).

As noted by key informants and FGD participants, intricate rituals and institutions such as New Year, harvest and other social celebration events; worship of ancestors; dealing with a range of other clan and communal matters have evolved in a dynamic relationship with trees. Maintenance of these rituals is core to conservation. The rituals are maintained fundamentally as local identity expression and reinforcement markers. Further, they are necessary to placate and commemorate deceased ancestors. They are emblems that provide a sense of origin, ethnohistorical narrative, territorial attachment and social-cultural identity for the present generation.

Maintenance of rituals requires spatial contexts where native trees and forests take central stage. The latter are regarded as embodiments of deceased ancestors in many communities in Ethiopia (Negash, Citation2010). A. falcatus, along with other native trees, is sacred in Ethiopia. In Wonsho, interviews with locals showed it is a venerated totemic tree, personifying deceased ancestors, conferring social status and clan allegiance to existing household owners and medium of connection between deceased ancestors and living progeny. It is the object of continuity of their ancestral traditions representing their ancestral origins, clan identity and socio-cultural viability. It is ingrained into the community’s ethnogenetic perception and ethnohistorical narratives and occupies crucial place in spatial and religious landscape.

The conduct of rituals and other communal affairs are crucial instruments in the conservation of these species, which benefit from inadvertent consequences of maintenance of rituals. The ritual instrumentality of the trees has required their planting and maintenance. Personifying tree species encourages strict barring of any mundane tinkering with them and their habitat as this is an affront to ancestral spirits, the violation of which invokes their highly feared wraths. The fear and respect of ancestral spirits, institutionalized and codified into community governance mechanisms, proved to be powerful instrument engendering A. falcatus-friendly attitudes, behaviours and practices. Community members are aware of the codes that stipulate the manner in which people would behave towards sacred sites and totemic trees. The traditional governance mechanism works by appealing to the conscious of community members. There had been no need for policing or physical enclosures. The consideration of these trees as sacred has proven to be very crucial for the conservation of the tree and its valuable role in social welfare, cultural diversity and continuity.

Results from the household survey confirm these views. Household heads were asked about their agreement with statements on whether sacred sites such as Abbo Wonsho Sacred Forest harbored some small plants, large trees and wildlife that are not found elsewhere (Table ). An overwhelming majority (94%) agreed that sacred sites serve as havens for fauna and flora that are disappearing or lost in other places due to over-utilization and habitat loss. Some native woody species, they noted, were in fact found only in such places.

Table 2. Households’ views of SNS as havens for endangered flora and fauna in Abo Wonsho Sacred Forest (AWSF), Wonsho-Sidama, Ethiopia (n = 200)

Table 3. Locally reported most endangered native woody tree species protected at Wonsho Sacred Sites, based on interviews, Focus Group Discussions, SNS surveys and observations, 2012, Bokaso, Ethiopia

While SNS are primarily important areas of locally endangered trees conservation, “less-sacred” or, other mundane spatial contexts are also important in this regard. “Less sacred” botanical landscapes of Wonsho household agro-forests constitute important extractive (sustainable use) forms for biodiversity conservation. In Sidama, an extractive form of conservation has been a key factor in the protection of forests and native trees, through agro-forestry and home-gardening activities.

6. Discussion

Biocultural diversity is a concept signaling connection between biological and cultural diversity (Harmon & Loh, Citation2005; Redford & Brosius, Citation2006). Sacred Natural Sites are increasingly considered showcases for biocultural diversity. This is because their strong cultural importance derives from, and requires maintenance of, biodiversity (Dudley, Higgins-Zogib, & Mansourian, Citation2009; McIvor, Oviedo, & Annelie, Citation2008; Sponsel, Citation2008, 2013; Verschuuren et al., Citation2010). Research interest in SNS and their role in the conservation of biological and cultural diversity have been increasing since the 1960s (Sponsel, Citation2008) and their conservation significance is increasingly recognized globally (IUCN & UNESCO Citation2008; Mallarach & Papayannis, Citation2009; Sobrevila, Citation2008), following the introduction of the concept of biocultural diversity into the conservation debate in the early 1990s.

There is a growing literature on the role of SNS in conserving biodiversity, with studies in Kenya (Metcalfe, Ffrench-Constant, & Gordon, Citation2009; Sheridan & Nyamweru, Citation2008), Sierra Leone (Lebbie & Guries, Citation2008), Tibet (Anderson, Salick, Moseley, & Xiaokun, Citation2005; Salick et al., Citation2007; Shen, Lu, Li, & Chen, Citation2012), Borneo (Salick & Ross, Citation2009), India (Bhagwat, Citation2009; Godole, Punde, & Samaik, Citation2014; Rao, Citation2002) and Indonesia (Wadley & Colfer, Citation2004). While findings from these various regions and countries portray specific peculiarities in terms of the types of species dominating the sites, they generally exhibit similar patterns to that of Ethiopia; i.e. that in all cases, where ancestral based and community conservation beliefs and practices exist, they result in the conservation of native species that otherwise and elsewhere were endangered (Table ).

In Ethiopia, SNS have been important instruments of conservation for millennia, long before any conventional form of conservation began (EIB, Citation2014). South-western Ethiopia is one of the hotspots of biocultural diversity and the use and conservation of biodiversity through home gardens, agroforestry practices, and sacred forests. Studies by Woldu (Citation2009) in Hammer, Konso and neighboring communities; Desissa (Citation2009) in Gammo highlands; Asfaw (Citation2003) in Sidama, and Kanshie (Citation2002) in Gedeo have shown that such beliefs and practices are part of the local livelihood needs and practices, that at the same time contribute towards conservation of natural resources and cultural diversity.

The SNS of Wonsho, Sidama exist as evidence of mutual, co-adaptive and dynamic interdependence between native trees and traditional institutions among traditional communities across time and space (Maffi, Citation2010; von Heland & Folke, Citation2014)). The way Wonsho community’s worldview, ethnohistory, culture, social structures, and economy are organized largely required botanical agencies for their expression and vitality, while at the same time supporting trees and other biodiversity (Sponsel, Citation2008; Verschuuren et al., Citation2010).

As the data presented in this paper illustrate, cultural keystone trees are embodiments of deceased ancestors in Wonsho Sidama. Sacred forests are likened to ancestors, embodying and enlivening the local custodian community’s sense of identity and concretizing their spatial-temporal existence (J. H. Hamer, Citation1976). They connect deceased ancestors and living progeny. Such a system is still resilient and relevant among traditional societies in Ethiopia and across the world and through the history of humanity. Elsewhere in Ethiopia, for example, among the Basketo in the southwest, the concept of Šossa is used for both the sacred forest and the Supreme Being, signifying the intertwining of culture and biodiversity. The Ţambaaro of southwest Ethiopia take the sacred dagaale (Ficus vasta) as the very embodiment of their Gambala Magano, the Supreme Being. The Me’enit of southwest Ethiopia commemorate their deceased by planting a Ficus vasta species on the burial mound. This biocultural connection between tradition religion and trees has led to protection being accorded to some native trees and forests in general. The livelihood and ecological needs of the local people also creates interdependence between people and trees. Similar to Wonsho, the consideration of ancestors’ spirit entities representable through trees as mediums has contributed to tree conservation among many traditional communities across the world, where some species of trees literally survived mainly due to their socio-cultural salience (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2005; Metcalfe et al., Citation2009; Rao, Citation2002; Shiva, Citation1998). In short, trees have functioned to humanize nature and naturalize humans for millennia (Sponsel, Citation2012); cultures and religions across time and space have conserved trees by recognizing them as sacred symbols of life, abundance, permanence, and beauty (Rival, Citation1998).

Honoring trees such as A. falcatus as a sacred object is useful and good not only for the conservation of the trees themselves but also for the continuity of robust ecological services of the trees. Local communities recognize these: planting trees and caring for them for the values of getting shade and shelter for humans and animals; creating, maintaining and improving soil fertility; breaking the power of winds, and so on (Negash, Citation2010).

In summary, this study has shown that the consideration of these trees as sacred and the maintenance of SNS are crucial for the continued existence and conservation of A. falcatus, along with other threatened native woody trees, with all the associated ecological services and the valuable role in social welfare, cultural diversity and continuity. This Wonsho Sidama case, therefore, gives strong support for recognizing the importance of linking cultural and biological diversity, and the argument that the role of local peoples, traditional systems and SNS is critical in supporting biodiversity conservation (Higgins-Zogib, Dudley, Mallarach, & Mansourian, Citation2010; Loh & Harmon, Citation2014; Mallarach & Papayannis, Citation2009; Stolton & Dudley, Citation2010; Verschuuren et al., Citation2010).

7. Conclusion

The findings of this study show that the SNS provide a link between the past and the present, the ancestors and the progeny, trees, and culture and thus they make biocultural diversity conservation possible. Maintenance of SNS and ancestral traditions is an instrument leading to an important, positive biodiversity conservation consequence for A. falcatus along with other threatened floral and faunal species. The otherwise threatened A. falcatus of Sidama Ethiopia exists today in the context of SNS which themselves are maintained for both their spiritual-ecological naturally materialistic and practically instrumentalist purposes. Such conservation has been made possible mainly due to the continued enactment of ancestral rituals and values.

In general, resilience of tree-supporting ancestral traditions imbued with animistic, nature dependent religious worldviews, maintained within the context of SNS has helped conservation of A. falcatus and other threatened native woody trees. These SNSs are “islands of biocultural diversity” in Wonsho Sidama and Ethiopia in general. This Wonsho, Sidama case, therefore, gives strong support for recognizing the importance of linking cultural and biological diversity, and the argument that the role of local peoples, traditional systems and SNS is critical in supporting biodiversity conservation.

8. Limitations, implications and recommendations

8.1. Limitations

The data and discussion above are a testimony to the sacred natural sites as showcases for the conservation of locally endangered native flora, such as A. falcatus, and cultural diversity associated with the species. However, while this paper’s strength and contribution lie in its documentation of the biocultural interface whereby A. falcatus and other endangered native trees are conserved, there are limitations. While some good lessons may be drawn from the Wonsho Sidama, Ethiopia case, it may not be feasible to generalize the findings to other contexts. Secondly, the paper relies on data that are in the main qualitative and they reflect an anthropological perspective.

8.2. Implications and recommendations

Sacred forest sites with their supporting traditions foster biodiversity in general and endangered native tree species find refuge therein amidst biodiversity eroding factors. This calls for widespread recognition by all concerned actors and concrete efforts in promoting and protecting sacred forests and ancestral traditions. Interventions are needed to increase awareness among all concerned stakeholders. This will help promote the biodiversity conservation relevance of sacred forest sites and especially the vital connections that exist between biodiversity and ancestral values.

There is a need for a multi-disciplinary, large-scale investigation to make a comprehensive inventory of the biodiversity of sacred sites and other informal protection areas in Sidama and the country in general to make a quantitative determination of the conservation status of A. falcatus and other native woody species.

The Sidama study shows there is a strong link between ancestral values and conservation of A. falcatus. There is a need for further investigation of the bio-cultural interface and the actual mechanisms of processes that result in conservation.

The biodiversity supporting values and governance principles inherent in the maintenance of sacred forest sites may further be tested for emulation and application in wider contexts by concerned conservationists and policymakers in the region more widely. The model of sacred forests and ancestral principles of their management may usefully inform current and future biodiversity conservation activities and approaches.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zerihun Doda

Zerihun Doda, a former professor at Hawasa University, Ethiopia, is currently a Senior Researcher and Assistant Professor at Ethiopian Civil Service University, Department of Environment and Climate Change. He obtained his PhD from the University of Kent, the United Kingdom in Anthropology and Conservation (May 2015). He further has an MA in Anthropology and a BA in Sociology from Addis Ababa University. Overall, he has 22 years’ experience of teaching and conducting sociological, social anthropological and inter-disciplinary research as a faculty member and as a consultant carrying out research and training for academia and NGOs. His research experience and interest areas include ethnographic, survey and ethnohistorical research; studies of identity, livelihoods, nature-culture nexus; social policy, development, social impacts of development projects; disadvantaged social groups and local communities; environment, society and climate change, among others. He maintains an interest in CAQDAS such as MAXQDA, NVivo, ATLAS.ti and Quirkos and provides training

References

- Anderson, D. M., Salick, J., Moseley, R. K., & Xiaokun, O. (2005). Conserving the sacred medicine mountains: A vegetation analysis of Tibetan sacred sites in Northwest Yunnan. Biodiversity and Conservation, 14(13), 3065–3091. doi:10.1007/s10531-004-0316-9

- Asfaw, Z. (2003). Tree species diversity, topsoil conditions and arbuscular mycorrhizal association in the Sidama traditional agroforestry land use, southern Ethiopia (Doctoral thesis). Retrieved from http://pub.epsilon.slu.se/214/

- Balee, W. (2006). The research program of historical ecology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, 75–98. Retrieved from http://landscape.forest.wisc.edu/courses/readings/Balee_AnnRevAnthro2006.pdf

- Balee, W. L. (Ed.). (1998). Advances in historical ecology. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Bhagwat, S. A. (2009). Ecosystem services and sacred natural sites: Reconciling material and nonmaterial values in nature conservation (Vol. 18, pp. 417–427).

- BIE (Biodiversity Institute of Ethiopia). (2014). Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants project (csmpp). Retrieved October 3 from http://www.ibc.gov.et/biodiversity/conservation/projects/conservation-and-sustainable-use-of-medicinal-plants-project-csmpp

- Braukämper, U. (1978). The ethnogenesis of Sidama. Paris Abbay, (9), 123–130.

- Chouin, G. (2002). Sacred groves in history: Pathways to the social shaping of forest landscapes in Coastal Ghana. IDS Bulletin, 33(1). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/502137/Sacred_Groves_in_History_Pathways_to_the_Social_Shaping_of_Forest_Landscapes_in_Coastal_Ghana

- CSA. (2013, August). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Wereda level from 2014 – 2017. Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. Retrieved from http://www.csa.gov.et/images/general/news/pop_pro_wer_2014-2017_final

- Desissa, D. (2009). Indigenous sacred sites and biocultural diversity: A case study from Southwestern Ethiopia. Retrieved from http://www.terralingua.org/bcdconservation/?p=62

- Dudley, N., Higgins-Zogib, L., & Mansourian, S. (2009). The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conservation Biology, 23, 568–577. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01201.x

- EIB. (2014, October 3). Ethiopian institute of biodiversity » Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants Project (CSMPP). Retrieved from http://www.ibc.gov.et/biodiversity/conservation/projects/conservation-and-sustainableuse-of-medicinal-plants-project-csmpp

- Godole, A., Punde, S., & Samaik, J. (2014). Culture-based conservation of sacred groves: Experiences from the North Western Ghats, India. In B. Verschuuren (Ed.), Sacred natural sites: Conserving nature and culture. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/5990541/Sacred_Natural_Sites_Conserving_Nature_and_Culture

- Hamer, J. (2007). Decentralization as a solution to the problem of cultured diversity: An example from Ethiopia. Africa, 77(02), 207–225. doi:10.3366/afr.2007.77.2.207

- Hamer, J. H. (1976). Myth, ritual and the authority of elders in an Ethiopian society. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 46(4), 327–339. doi:10.2307/1159297

- Harmon, D., & Loh, J. (2005). A global index of biocultural diversity. Ecological Indicators, 5(3), 231–241. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2005.02.005

- Higgins-Zogib, L., Dudley, N., Mallarach, J.-M., & Mansourian, S. (2010). Beyond belief: Linking faiths and protected areas to support biodiversity conservation. Earthscan. Retrieved from http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:238018

- Igoe, J. (2004). Conservation and globalization: A study of the national parks and indigenous communities from East Africa to South Dakota. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- IUCN. (2011). Afrocarpus falcatus: The IUCN red list of threatened species 2013. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42438A2980290.en

- IUCN, & UNESCO. (2008). Sacred natural sites. Guidelines for protected area managers. Retrieved from www.iucn.org/themes/wcpa/pubs/guidelines.htm

- Johnston, A. M. (2006). Is the sacred for sale? Tourism and Indigenous peoples. London: Earthscan.

- Kanshie, T. K. (2002). Five thousand years of sustainability? A case study on Gedeo land use (Southern Ethiopia) (PhD Dissertation). Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Retrieved from http://edepot.wur.nl/198428

- Kibrework, L. (2011). Discourses of ethnolinguistic diversity; the case of Ethiopia. International Conference on Management, Economics and Social Sciences. Retrieved from psrcentre.org/images/extraimages/1211708.pdf

- Lebbie, A., & Guries, R. P. (2008). The role of sacred groves in biodiversity conservation in SIerra Leone. In M. J. Sheridan & C. Nyamweru (Eds.), African sacred groves: Ecological dynamics and social change (pp. 42-61). Athens, GA London: Ohio University Press: James Currey.

- Loh, J., & Harmon, D. (2014). Biocultural diversity threatened species, endangered languages. Zeist, The Netherlands: WWF Netherlands. Retrieved from http://biocultural.webeden.co.uk

- Lorraine. (2013, February 9). Podocarpus falcatus [Text]. Retrieved from http://kumbulanursery.co.za/plants/podocarpus-falcatus

- Maffi, L. (2010). Biocultural diversity conservation: A global sourcebook (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

- Maffi, L., & Woodley, E. (2010). Biocultural diversity conservation: A global sourcebook. London; Washington, D.C: Earthscan.

- Mallarach, J.-M., & Papayannis, T. (2009). The sacred dimension of protected areas: Proceedings of the second workshop of the Delos initiative, Ouranoupolis 2007. Gland: World Conservation Union.

- McIvor, A., Oviedo, G., & Annelie, F. (2008). Bio-cultural diversity and Indigenous peoples journey. Barcelona, Spain. Retrieved from http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/bcd_ip_report_low_res.pdf

- Metcalfe, K., Ffrench-Constant, R., & Gordon, I. (2009). Sacred sites as hotspots for biodiversity: The three sisters cave complex in coastal Kenya. Fauna and Flora International, Oryx, the International Journal of Conservation. doi:10.1017/S0030605309990731

- Moges, A., Dagnachew, M., & Yimer, F. (2013). Land use effects on soil quality indicators: A case study of Abo-Wonsho Southern Ethiopia. Applied and Environmental Soil Science, 2013, e784989. doi:10.1155/2013/784989

- Negash, L. (2010). A selection of Ethiopia’s Indigenous trees: Biology, uses and propagation techniques., Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press.

- Officers, SCRBO. (2012, December). Focus group discussion with experts at Sidama Community Radio Broadcasting Organization, Yirgalem, Ethiopia [Face-to-face].

- Rao, R. (2002). Tribal wisdom and conservation of biological diversity: The Indian scenario. In J. R. Stepp, F. S. Wyndham, & R. K. Zarger (Eds.), Ethnobiology and biocultural diversity: Proceedings of the seventh international congress of ethnobiology (pp. 1-10). Athens, GA: International Society of Ethnobiology: Distributed by the University of Georgia Press.

- Redford, K. H., & Brosius, J. P. (2006). Diversity and homogenization in the endgame. Global Environmental Change, 16(4), 317–319. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.07.001

- Rival, L. (1998). The social life of trees: Anthropological perspectives on tree symbolism. Oxford, UK: Berg 3PL.

- Salick, J., Amend, A., Anderson, D., Hoffmeister, K., Gunn, B., & Zhendong, F. (2007). Tibetan sacred sites conserve old growth trees and cover in the Eastern Himalayas. Biodiversity and Conservation, 16(3), 693–706. doi:10.1007/s10531-005-4381-5

- Salick, J., & Ross, N. (2009). Traditional peoples and climate change. Global Environmental Change, 19(2), 137–139. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.01.004

- Schaefer, R. T. (2003). Sociology (8th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Shen, X., Lu, Z., Li, S., & Chen, N. (2012). Tibetan sacred sites: Understanding the traditional management system and its role in modern conservation. Ecology and Society, 17(2). doi:10.5751/ES-04785-170213

- Sheridan, M. J., & Nyamweru, C. (Eds.). (2008). Introduction. In (Eds.), African sacred groves: Ecological dynamics and social change. Athens; London: Ohio University Press; James Currey.

- Shiva, V. (1998). Biopiracy: The plunder of nature and knowledge. London: The Gaya Foundation.

- Sobrevila, C. (2008). The role of Indigenous peoples in biodiversity conservation the natural but often forgotten partners. The World Bank. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTBIODIVERSITY/Resources/RoleofIndigenousPeoplesinBiodiversityConservation.pdf

- Sponsel, L. E. (2008). Spiritual ecology, sacred places, and biodiversity conservation. In Encyclopedia of earth. Retrieved from http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/51cbeecf7896bb431f69a6f4

- Sponsel, L. E. (2012). Spiritual ecology: A quiet revolution. Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers Inc.

- Sponsel, L. E. (2013a). Human impact on biodiversity, overview. In S. A. Levin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of biodiversity (2nd ed., pp. 137–152). Waltham: Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123847195002501

- Sponsel, L. E. (2013b). Human Impact on biodiversity, overview. In S. A. Levin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of biodiversity (2nd ed., pp. 137–152). Waltham: Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123847195002501

- Stolton, S., & Dudley, N. (2010). Arguments for protected areas: Multiple benefits for conservation and use (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

- Tadesse, K. (2012). Trees of Ethiopia (a photographic guide and description). Addis Ababa: Washera Publishers.

- Toledo, V. M. (2013). Indigenous peoples and biodiversity. In S. A. Levin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of biodiversity (2nd ed., pp. 269–278). Waltham: Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123847195002999

- Vaughan, S. (2003). Ethnicity and power in Ethiopia (PhD Dissertation). The University of Edinburgh.

- Vaughn, C. (2010). Sheka project assessment. In Addis ababa. MELKA Mahiber, Ethiopia.

- Verschuuren, B., Wild, R., Mcneely, J., & Oviedo, G. (2010). Sacred natural sites: Conserving nature and culture. London: Routledge.

- Vivero, J. L., Ensermu, K., & Sebsebe, D. (2006). Progress on the red list of plants of Ethiopia and Eritrea: Conservation and biogeography of endemic flowering taxa. In G. S.A. & B. H.J. (Ed.), Taxonomy and ecology of African plants, their conservation and sustainable use (pp. 761–778). Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens.

- von Heland, J., & Folke, C. (2014). A social contract with the ancestors – Culture and ecosystem services in southern Madagascar. Global Environmental Change, 24, 251–264. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.003

- Wadley, R. L., & Colfer, C. J. P. (2004). Sacred forest, hunting, and conservation in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Human Ecology, 32(3), 313–338. doi:10.1023/B:HUEC.0000028084.30742.d0

- Woldu, Z. (2009). Biodiversity conservation through traditional practices in Southwestern Ethiopia, a hotspot of biocultural diversity. Retrieved from http://www.terralingua.org/bcdconservation/?p=79