Abstract

There is growing recognition of the benefits of creative experiences and activities in social and health care. This article focuses on social services clients’ experiences of creativity and arts in their lives. Ten social services clients were interviewed about their experiences in relation to creativity or creative activities. These interviews were analysed by employing the existential-phenomenological approach. As a key finding of this research, we present a conceptualisation of how creativity enhances the reconstruction of the life narrative. The findings reveal four key aspects of how creativity is perceived and experienced as part of life, what kinds of meanings these experiences carry and what their significance is in people’s lives. These are: (1) constructing coherence, (2) fostering feelings of significance and purpose, (3) constructing meaningfulness and (4) creativity in everyday life and as a spiritual dimension. We argue that creativity is essential for (re)constructing life narratives. This process subsequently enhances agency and well-being. These results deepen our understanding of the intertwined nature of meaningful life experiences and creativity. Furthermore, the results indicate that creative activities could be utilised more in social work, aiming to support people in a vulnerable position.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Self-expression and creativity can scaffold for making sense of one’s life. We studied the experiences of social service clients and found out how fundamental element creativity can be in one’s life. As findings of the research project ‘The tune of my life’ this article depicts the dimensions and important roles that creative experiences play in the lives of these 10 social service clients. This enables us to understand how creativity can enhance well-being and living a fulfilled life. It also facilitates developing social services and social work practice. The results of this research indicate how creative activities and experiences could be utilised more in social work aiming to support people in a vulnerable position.

1. Introduction

If I couldn’t express myself, I’d be as good as dead (I1).

This research explores social work clients’ experiences of creativity in their lives. First, this article explores the key concepts of creativity, experience, meaning and life narrative that underpin this study. Second, it describes the methodological choices, process and results of the study. Third, it suggests a conceptualisation of how creativity enhances the reconstruction of the life narrative and (re)directs agency. The research results and their implications deepen the understanding of the intertwined nature of meaningfulness and creativity. We argue that creativity is essential for (re)constructing life narratives. This process subsequently directs agency and enhances well-being. Furthermore, the results indicate that creative activities could be utilised more in social work aiming to support people in a vulnerable position.

2. Underpinning meaning construction and creativity

This article is contextualised in creativity and creative experiences. The methodological framework comes from existential phenomenology. Theoretically, the article has two threads, one discussing the role of creativity and creative experiences in constructing meaning in life, and the other shedding light on the (re)construction of narratives.

Craft (Citation2001, pp. 54–55) suggests that creativity is a way of coping with everyday challenges and a skill with which to see opportunities, and to identify problems and solve them with imagination. This involves questioning “What if …?” The core areas of possibility thinking are imagination, self-determination, doing something original, action and development, taking risks, posing questions and toying with possibilities (Craft, Citation2001, pp. 56–59).

Playfulness and imagination are fundamental dimensions of living a fulfilled life, so fundamental that creativity can be seen as a capability (see Nussbaum, Citation2011). It may create a buffer against difficulties, symbolically speaking, providing a temporary haven from hardships. Creativity can also create a world of possibilities where the impossible becomes possible and the invisible takes form.

This study has its basis in existential phenomenology. At the core of this approach is a holistic understanding of human beings as a combination of three existential modes: consciousness, materiality and situatedness (Perttula, Citation1998; Rauhala, Citation2005; see also Koskiniemi, Vakkala, & Pietiläinen, Citation2018). Experiences are conceived as meaning relations between one’s realisation, functions and objectives, comprising emotions, impressions, associations, beliefs, opinions, values and perceptions (Latomaa, Citation2009, pp. 27–28; Perttula, Citation2009, p. 119, pp. 123–124).

Meaning, then, is a shared mental representation of possible relationships between things (Baumeister, Citation1991, p. 15). It is directly or indirectly constructed between people in the social sphere through a variety of signs, such as words, glances, beliefs and actions. We negotiate and evaluate our experiences in a dynamic, constant process in dialogue with our social and cultural environment and significant others (see, e.g. Côté & Levine, Citation2002, pp. 47–49).

In order for meaning to emerge, one requires the capacity for reflective thinking and forming mental representations of the world, as well as developing connections between these representations. We hold the view that, in addition to linguistic thinking, reflective thinking can also happen through emotion, handling things, playing and gardening (Groth, Citation2017; Wilson & Golonka, Citation2013). Recent neural research verifies that meaning-making processes may occur as embodied cognitions. Eye contact, gestures, touches and silences during communication generate reactions in the autonomic nervous system, and these reactions help people get in tune with one another (Karvonen, Kykyri, Kaartinen, Penttonen, & Seikkula, Citation2015; Myllyneva, Citation2016).

In reporting our findings, we utilise the classification of the three facets of meaningfulness: coherence, purpose and significance. Coherence covers making sense of the world in a value-neutral manner. It is about feeling confident and understanding that one’s life and environments are structured and predictable. Coherence is constructed from the here and now—the present (Martela & Steger, Citation2016, pp. 533–534, p. 536). Significance, in turn, refers to value-laden concepts. Significance is concerned with evaluating value in life. It focuses on the worth and importance of one’s activities. One continuously evaluates whether functions are significant in the eyes of others. The tenses of significance are past, present and future. It follows that experiencing significance is determined by past activities as well as activities in the present and the future (pp. 534–536). Like significance, purpose is a value-laden concept. It tells of the direction in life, it is future-oriented, and it generates the motivation to find valuable goals. In addition to this, finding purpose in life may lead to a process where it is possible to see one’s life in a new light.

We assume that creativity-related activities enable the life narrative to be processed in relation to meaningfulness. Hänninen (Citation2004) suggests a model for conceiving of this narrative through its three modes: inner, told and lived narrative modes. The inner narrative is experiential in nature and represents the individual’s interpretation of his or her life (pp. 74–77). This mode refers to the organisation of experiences and actions towards coherence. The externalisation and validation process of the inner narrative is called the told narrative (pp. 77–81). This is not always necessarily verbal, but it is shared and expressed in some form to others. The third dimension of the model is the lived narrative, which refers to the narrative quality of life itself: the adequacy of the inner narrative is tested in real-life drama (pp. 80–82). According to the model of narrative circulation, these narrative dimensions are all related to one another (Hänninen, Citation2004).

3. The existential-phenomenological approach adopted in this research

3.1. Method

This research employs the existential-phenomenological approach (Perttula, Citation1998; see also Koskiniemi & Perttula, Citation2013; Perttula, Citation1995; Koskiniemi et al., Citation2018), which is an interpretation of Giorgi´s phenomenological method (Giorgi, Citation1985, Citation1997, Citation2012). This approach combines the viewpoint of individual experiences with the general aspects of experiences (see Koskiniemi et al., Citation2018; Rauhala, Citation2005) and therefore lays a solid methodological foundation for this research that aims for a wider understanding of the roles that creativity can play in the lives of social work clients. Van Manen (Citation2007) describes phenomenological research as follows: “the phenomenologist directs the gaze toward the regions where meaning originates” (p. 11).

Our research questions read as follows:

What kinds of experiences do social work clients have in relation to creativity or creative activities?

What kinds of meanings do these experiences carry in the lives of the clients?

3.2. Data

The research data were gathered through unstructured, open interviews with 10 clients who participated in social group work aiming at social inclusion. The voluntary interviewees received information about this research (its aims, process, data gathering) both in written and oral forms, before giving their approval and consent to use the interview material as the data of this research. It was made clear that participation in this study was voluntary and that the participants could withdraw from the research at any stage of the process without any consequences regarding the general social service benefits available to them. The research data have been handled confidentially and reported in an anonymised form (Interviewee 1 [I1], I2, I3, etc.) to ensure that no interviewees can be identified.

The interviews started with the open question “What does creativity mean to you or what comes to your mind when you think about it?” The four interviewers (supervised by the researchers) supported the participants in sharing their thoughts by using gestures, tone of voice and helping questions that all aimed to create a relaxed atmosphere and to allow people to describe their experiences in a way that suited them (see Aaltonen & Leimumäki, Citation2010, p. 120; see also Lehtomaa, Citation2009; Perttula, Citation1995). The interviews were later transcribed and the quotations for the present article also carefully translated into English, maintaining the essence of the narrative.

3.3. Analysis

This existential-phenomenological analysis was conducted by two researchers who worked in collaboration and used NVivo software to code and organise the data. The analysis process progressed through the following steps:

1. Both researchers read through all the transcribed interviews in order to form an overview of the data. After this, they discussed their overall views of the entire research material. At this point, two categories—the main themes—emerged when classifying the contents related to the key issues of the research material (Perttula, Citation1998, p. 78). On one hand, the interviewed clients aiming to share their thoughts about creativity in their lives seemed to describe their life events. These were described in light of an environment for creative experiences (situatedness). On the other hand, the clients focused on experiences directly connected to creativity.

2. The interviews were divided into text units that comprised one experiential “meaning of something” (for meaning relations see Perttula, Citation1998, p. 79; see also Koskiniemi et al., Citation2018). These sections were transformed into general language with the aim of preserving the essence of the experiences (Perttula, Citation1998, p. 79; see also Koskiniemi et al., Citation2018). This was performed by utilising phenomenological reduction, which enables the essence of these meaning relations to be unravelled (Perttula, Citation1998, p. 79). In a way, the words in the interviews simultaneously reveal and hide the essence of the meanings (see Kvale, Citation1996, p. 53; Van Manen, Citation1990, p. 26). This process aimed to describe the essence of the experiential meanings related to creativity as part of the life experiences of the client.

3. After these steps, the experiences of creativity in each interviewee’s life were described as one narrative (for individual meaning networks see Perttula, Citation1995, Citation1998, Citation2000, Citation2009). These were constructed from the transformed, general language text parts and were organised with the two main themes (life events and creativity-related experiences) that emerged in the first stage of this analysis. Both researchers studied the general texts—descriptions of the essence of meaning—produced by the other, and these were opened up to critical discussion, which supported the use of phenomenological reduction in the process (see Perttula, Citation1998). This intersubjective corroboration (see Gallagher & Zahavi, Citation2008) enhanced the credibility of the analysis.

4. In the next phase, NVivo software was used to code each interview. Both the original text in the meaning relation and its transformed general text version (Step 2) were coded with classifying themes that describe that section. The essence of the meaning relations was coded with descriptive “labels” that aimed to identify the core of the described experience. The created labels were open for discussion among the researchers in order to find shared expressions and classifying themes, as well as to organise the data. With the help of NVivo, each new classifying theme added to the complete list of themes. As a result of this part of the process, classifying themes that organise the entire research data were gradually formed (see Table , first column).

Table 1. Themes, key findings and related concepts

This phase was again realised as a joint effort by the two researchers, which enabled critical discussion in the analysis process.

5. The following step in the analysis process was to organise all the material under the classifying themes that organised the entire research material. This was done with the help of NVivo software.

6. Once the whole material was organised, a cluster analysis produced by NVivo software was used as a tool for forming an overview of the organised material. This provided a fruitful starting point for the dialogue between researchers and facilitated organising the collaboration further. This vehicle revealed overlaps, a hierarchy and similarities in the classifying themes. At this point, the relevance of differences caught the attention of the researchers: discussing the finding that, in this material, the most far apart from each other seemed to be the themes “the joy of creativity in everyday life” and a “spiritual element”. This became an important phase in the process. These two dimensions form a continuum along which all the experiences described in the research material could be placed. This notion of the analysis helped to organise the themes hierarchically, and some of the themes were merged at this point.

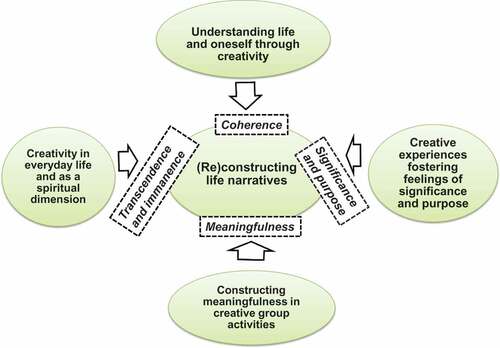

7. As a result of the previous steps in the analysis, the general meaning network was constructed. This illustrates four key aspects (see Table , middle column, and Figures and ) that describe how creativity and its meaning as part of life are perceived by the interviewed social work clients. This meaning network is explained in detail in the following section of this article.

The credibility of our research process is strengthened by triangulation in all phases of the analysis. This enabled the researchers to utilise the support of critical dialogue in order to reflect upon and make distinctions between their own experiences and those of the interviewees, which is the cornerstone for credibility in the existential-phenomenological method (Koskiniemi & Perttula, Citation2013). In this process, both of the researchers expressed critical thoughts during the course of the analysis concerning their choices, subjectivity or horizon of understanding (see Perttula, Citation1998, pp. 167–168) and these were reflected in dialogue in order to facilitate phenomenological reduction. The researchers did not know each other before this process, and as a result, at the beginning, the criticism may not have been as deep or challenging as much of the critical reflection took place towards the end of the process. The above-mentioned triangulation is related to the credibility of this method, providing the needed reflective criticism for the study. Furthermore, it enables a wide horizon for understanding that is formed by the two researchers with different viewpoints (see Perttula, Citation1998, p. 50, Citation2009, pp. 136–145; see also Koskiniemi et al., Citation2018), which facilitates the validation of the analysis through cross-verification from two perspectives. This facilitates making discoveries about the experiential world of the interviewed clients and understanding the meanings of their experiences (see Giorgi, Citation2012). Phenomenological research calls for transparency and accuracy in reporting the analysis in all of its phases (Perttula, Citation1998, p. 168; see also Koskiniemi et al., Citation2018).

4. Findings: creativity and its meanings as part of life

The findings of this research reveal four key aspects of how creativity is perceived and experienced as part of life, what kinds of meanings these experiences carry and what their significance is in people’s lives. These are (1) understanding life and creating coherence, (2) fostering feelings of significance and purpose, (3) constructing meaningfulness and (4) creativity in everyday life and as a spiritual dimension.

4.1. Coherence: understanding life and oneself through creativity

Creative group activities help people understand themselves and their environment. The activities evoke memories and sensations, which allows them to be recognised and related feelings put into words. The interviewees often spoke in a way which we interpreted to mean that the creative activities helped them to analyse the world and their feelings.

In our data, creativity manifested as a means to perceive and move boundaries. The same contents came up frequently. One of the interviewees approached the matter metaphorically through the concepts of formulas and unconventionality:

—when it comes to [mathematics], you cannot alter anything, say, when dealing with the sum of some calculation, whereas in arts you can do things like paint a painting in different ways, which allows you to change whatever you want. (I10)

In order to regulate one’s emotions, a person must first recognise his or her sensations and connect them to their lived experiences, which results in a feeling that can be named. In turn, an emotion is the social projection of a feeling (Shouse, Citation2005). Perceiving one’s sensations increase the predictability and manageability of one’s life. This might also open up new perspectives on the person’s self. In the following quote, the interviewee explains how activities in nature, which she had initially considered frightening, were transformed into an experience of success:

—yeah and I was thinking that this is also a very surprising feeling, that how will I be able to cope with this, and then it all went quite nicely there, so—something about it, I don’t quite know, and the greenness and the soundscape and flowers and—I don’t quite know how to say it, it was just, like, a continuation of what had been going on here [with the group]. Something really astonishing. (I5)

It appears that people succeed particularly well in analysing their feelings when they have first distanced themselves from them. Taking some distance from vague sensations may result in forming an understandable idea of them. Creative activities and experiences of art provide a way out of unrelenting despair or an unexplained sense of fatigue, for instance. This is particularly the case with music, which evokes mental images and memories, thus bringing feelings to one’s consciousness for processing. This was expressed by many of the interviewees, such as in the following example:

“one piece of music always reminds me of—being proposed to by this one person once—We were dancing to that song” (I4).

Music not only helps people discover and retain a rhythm in their daily lives but also to regulate it and their everyday lives:

And music! It plays a huge part in my life, I always keep the radio on—I mean, I keep it on very quiet so I don’t even always hear or listen to it but I constantly register if there’s a good song playing. So you’ve always got to have some music. Of course, it also affects your mood. (I1)

A piece of music can reach something so deep within a person that it can be difficult to play or listen to it. When this happens, we have entered deeply into the domain of affects. In the following excerpt, the interviewee explains how recognising a pattern related to his feelings has also allowed him to regulate them when music is about to stir up his emotions:

“—when some song you are playing touches you like crazy, you have to look away or say that we won’t be playing this” (I9).

Many of the interviewees perceive creativity as actively doing things. Intense affects, which are perhaps not even identifiable sensations, are organised in activities and can even be expressed in words in them “The way it is that you have to start moving and have to start doing things. I love interior design” (I1). People learn by doing, which increases their understanding and skills. This is despite the fact that a person whose daily life involves struggles or has no structure may not always perceive their opportunities for activities. This can also go the other way around: when a person’s daily life forms an understandable and functional entity, his or her life becomes more manageable and opportunities are increased.

Some of the interviewees had succeeded in expanding their lifeworlds through creative activities. The following interviewee is able to capture something of what are often non-verbal processes in describing the essence of creative activities through theatre:

“When you have a limited amount of space, you have to use your imagination to express those [things] in some way” (I5).

Creative activities help create coherence, or the understandability and predictability of life, in the present moment. In addition, once a person’s life is coherent and order is found in the midst of chaos, he or she will find it easier to explain his or her life in an internal dialogue, and this will become more structured. In addition to words, life can also be expressed through active doing. Internal speech involves introspection, understanding sensations that change based on situations, and finding meaning in life.

Once a person is able to manage his or her daily life, creativity can allow him or her to break free of patterns in a manageable way.

4.2. Significance and purpose: creative experiences fostering feelings of worth

Creativity broadens the frames of one’s life (see Craft, Citation2001). Goals stemming from needs and relevant activities are placed within these frames. Our data indicate that creative activities open up room for this sort of possibility thinking and this allows people to deliberate about different future goals. In this context, shaping one’s life narrative means processing meanings and goals in order to combine and reorganise them.

In our research data, creativity is described as a way of doing things in an individual manner. It is also addressed as a way of seeing and doing things differently. Nearly all of the interviewees made reference to creativity as a positive force central to their lives.

I mean, creativity is about—doing and coming up with and thinking about various things differently—creativity has an effect—on having a versatile life, doing different things, always thinking differently, and by doing so usually ending up with different outcomes. (I10)

Creativity is perceived as a source of well-being within almost everyone’s reach. In many interviews, it was also described as an essential part of one’s persona that helps people express themselves. Sometimes creative activities help people recognise their own needs from which they have become disconnected. For example, people may have been drawn to playing music or expressing themselves visually during childhood but may have lost some interest in the matter in adulthood.

Back at school I was extremely keen on learning to play the piano—But no one ever taught me that—But it’s probably not too late. (I4)

Creativity is intertwined into a person’s life narrative. Art or music, for instance, is explained as something that moves a person to the core in a particularly powerful way, as illustrated below in a quote from one of the interviewees regarding the way music makes her feel: ”It is as if you are grabbed by the soul” (I2). This interviewee explained that violin music played a particularly important part in her life. As a child, she wished she could play the violin, but the wish never came true. This became a painful issue to her. Therefore, the fact that her mother later apologised for not giving her lessons felt important for her. The apology seemed to carry the meaning that her need had been recognised and taken seriously.

For one of the interviewees (I2), colours and paintings played a particular role. She explained that she was always careful in selecting visual elements. Another interviewee (I10) referred to his hobby, martial arts, as a form of creative activity where the movements are always carried out with one’s personal touch. In the data, creativity also referred to surprises and doing good to others, such as organising parties and giving handmade gifts to people who matter to them (I1). Creativity was connected to interacting with others: gifts connected the interviewee to an interaction with her environment, providing her with an experience that what she did mattered. In addition to the creative actions themselves, a sense of being able to leave a mark on one’s environment or having one’s presence or actions recognised in a positive way emerged from the contents. Opportunities for this emerged in diverse environments, recreational activities and aesthetic choices. Simultaneously, an opportunity for experiencing value, i.e. significance, opens up. This, in turn, helps people see their personal narratives in a new light. Sometimes, all it takes is a minor impulse, such as arranging flowers in a vase.

–flowers, that’s what I was planning, putting them in a large container, that’s probably the most recent thing.—I’ve been looking at them and taking photos of them and then considering whether it was a nice arrangement. (I5)

One of the interviewees stated that she was not particularly fond of drawing. Nonetheless, she related a story of a watercolour painting she had made on a course that a family member had framed. This particular painting was placed so that it was the first thing she saw when she came home. She also mentioned how the people who had seen the painting had made positive comments about it (I4). In this example, creative output also frames the interviewee’s life in quite a concrete way, as the positive feedback on the artwork reminds her that there is something good and worth noticing in her.

While the interviewees included those actively engaging in art or creative activities (e.g. playing in a band), there were also others for whom creative activities were a more distant subject. One of the interviewees described her first impressions of creative group activities that included playing with sounds as follows:

“I don’t know how to create art—and I’m definitely not gonna make any sounds—” (I5).

Despite these thoughts, experimenting and coming up with different sounds seemed to open up new perspectives for this interviewee.

The research data revealed that the notions regarding expanding one’s life were important as they often also provided the interviewees with an experience that they themselves valued. The experience of being appreciated for one’s actions in the present moment also enabled the interviewees to regard their future more positively and even reporting about past events in a new light.

Composing one’s own music and making songs provided concrete tools that allowed people to explain and shape their life narratives and share them with others. One of the interviewees (I9) addressed the meanings related to music in his life by describing how playing music and composing songs formed the structure of his life. In his life, he had experienced a particularly creative period during which composing songs had played a major role and he had been working on them day and night while utilising big emotions. The interviewee described creating music and especially composing songs as an opportunity for development as well as having a direction and goals to work towards in his life. As a result, creativity can create fundamental value in a person’s life, which was also put into words by another interviewee as follows:

‘‘If I couldn’t express myself, I’d be as good as dead” (I1).

On one hand, these narratives depicted how creative activities enabled people to express themselves to others and gather an experience of significance, while on the other they indicated how creativity was even linked to a person’s experience of the meaning of life. For instance, playing music together strengthened positive characteristics in a person’s life narrative and even carried them through a vulnerable situation.

The purpose found in life through creativity motivated people and encouraged them forward. One of the interviewees described his idea of purposeful reablement as something that should ignite a spark of activity or enthusiasm in a person:

—whether it’s music or anything else—it provokes this thought in a person that makes them get involved in something. (I8)

Creative activities and thinking appeared to introduce new material to the persons’ own told narratives. They may provide people with a means to express sensations that are left unanalysed or experiences left unstructured in words for the first time or again, for instance, in a situation where an issue previously experienced in private is presented in a joint space through means such as a cultural product, picture, object or joint activity. We conclude that creative activities may provide people with an incentive to experiment and reflect on different issues in relation to both personal experiences as well as those of others. Creative activities and creative thinking are a form of internal speech where one proves his or her own value. This internal voice is also present in this dialogue as someone who takes note of and gives value to the person’s actions and challenges them to look at alternatives. People can also use cultural ingredients, such as pictures, songs and stories to inject material into their own narratives. This transforms one’s life narrative with new meanings.

4.3. Constructing meaningfulness in creative group activities

Creative group activities help individuals join in an interaction with others and influence it as well as be influenced by it. In this context, people negotiate the contents of their life narratives and construct a shared narrative.

Bodily activities provide impulses to interactions with other people who share the same space. As a result, creative activities, including their embodied and social cognitions, help individuals both mark and regulate their intra- and intersubjective reactions.

The experiences emerging through creative activities join people together and lead them to interact. Indeed, one of the interviewees considered what his hobby, photography, was lacking was a group and thus also being able to attune to shared experiences with others (I6). In fact, for another interviewee, the most essential part of playing in a band was crystallised in the way playing music joined people together:

–having this sort of social interaction—that is probably the biggest point of it all in the end.—[not] getting stuck in your own flat and rotting there. (I8)

It was expressed in the interviews that creative activities bring on not only interaction but also reciprocity. It is also highlighted in this context how important it is for people and their activities to not only be seen and noted but also take note of other people’s activities and learn from them.

It is important if you personally learn something or it affects you and if you teach something to others and have an influence on them. (I7)

Many interviewees also described playing in a band as important from the viewpoints of communal activity and the development of personal abilities. In this process, cooperation, or playing music with others, is where learning takes place. One of the interviewees related that he found it important to do things that not only he personally values but that are also valued by others. For example, when performing in front of others, he may feel that he is useful and is producing something good for other people. It is also important that people feel that they are members of a meaningful community to which they must commit, where everyone is needed, and every member’s input and development are important for the whole. When a person is part of such a group, he or she must take responsibility for the smooth flow of things. Therefore, collaborative activities may introduce a daily rhythm that improves self-regulation and the manageability of life.

—you have to be committed to what you’re doing on some level, aiming to be present as much as possible, on the agreed date. That at least is an important part of it, if it is, if you’re doing and creating something together and someone’s missing, you have to think like, how are we gonna do this, then. (I6)

The same interviewee felt that belonging to a community and taking part in meaningful activities reduce problems and exclusion. According to the interviewee, a person’s need for medication may even be reduced if he or she has something to do and has opportunities for involvement.

—it, like, brings you both friends and meaning, being attached to some activity, and is something you also personally value and others can also value. It, like, helps you every day, moving on one day at a time.—It brings joy, joy of success, inspiration, to always keep on practising more. Being, like, in a community, and reducing all these other negative things. So you could easily get stuck and, like, just stay at home. Or, like, you’d start having troubles—You can’t solve all your problems with medication,—But it is about activity and participation.—When you have things to do, you also won’t mess up your rhythm—So, yeah, a message to all decision-makers, learn something from this. (I6)

A band provided the interviewee with something meaningful to do, strengthened his sense of community and brought structure to his life. As the facilitator of all of this, the professional has an important task, as he or she creates the frames for the creative group activities and takes care of the process (I6).

The analysis also raised an idea that the creative group process can form a space where people can join as well as analyse and adapt their own ideas and impulses as part of a shared narrative. Interpreting the joint narrative through music (e.g. creating and composing a soundscape) created a challenging yet positive experience of interaction.

You did have to use your creativity and inspire others—It was a little difficult, having to come up with a new thing there.—You didn’t really have to come up with everything there, so every one of us did a little bit of something, and that created a good whole.—we did work together. But it wasn’t like, not everyone participated all the time. So there were times when someone did more and someone less, but in the end, we played and improvised together.—You got a little nervous, having to improvise when nothing was ready. (I10)

Interaction provides people with an opportunity to do something they value personally and that is also valued by others. It allows people to create a shared experience, and transform individual sensations into social feelings; for instance, one of the interviewees related an experience that laughter is contagious (I5). A sense of togetherness creates joy and enhances feelings of purpose. Connecting with other people facilitates the development of an experience of meaningfulness. In turn, an experience of meaningfulness and value promotes coping. Necessity, dignity and living life on one’s own terms are concepts not far removed from equality, longing for a moment when people’s skills or characteristics are not rated hierarchically:

“So it felt like everyone was able to succeed in their own ways and there was no need for comparison” (I5).

One of the interviewees came up with a tentative idea of a service involving music activities for a residential unit for people with disabilities. The service would also provide a solution for people’s needs to be valued for who they are. He expressed this as follows:

“Everyone would be needed there in their own way” (I6).

Attuning to and connecting with others in creative activities at a certain level of consciousness and feelings may also come to facilitate social situations elsewhere in life. In a shared group process, creative activities provide joint operations in social relationships through which the participants can process their own experiences. The group also enables people to join their own experiences into a shared reserve of meanings. This allows connecting cultural narratives with individual experiences, and perhaps changing these into a shared experience, thus creating meaningfulness to people. In an interaction related to creative activities, people’s life narratives are shaped by the features of their personal internal world and narrative as well as material from a cultural reserve of meanings, including song lyrics, art, stories, pictures, colours and shapes.

Playing music together with others can reflect all of the dimensions of meaningfulness at the same time: the music progresses as anticipated, and each person’s musical instrument is involved in constructing a soundscape with others in a meaningful and unique way and creating an experience so that their life and personality have a purpose.

I mean, it does matter as it is about the persona you have in a way—So without it, it would all be pretty empty. (I9)

4.4. Creativity in everyday life and as a spiritual dimension

An important observation concerns the fact that, based on the experiences of the interviewees, creativity is placed in a continuum spanning a person’s entire life from daily living to spiritual aspects. This is shown in Table .

Table 2. Themes emerging from the data about experiences in relation to creativity

In order to experience meaningfulness in life, people need an opportunity to detach themselves from the present moment. Meaningfulness is constructed in motion between the material and immaterial world. Creativity cuts through one’s life as a continuum, at one end of which is everyday creativity and at the other life beyond daily life.

The contents of the data can be observed as movement from coherence in the present moment to an experience of the meaning of life through an experience of significance. However, daily life and the contents beyond it were not categorical opposites; instead, they are often amalgamated.

Reflective thinking is required in order to experience meaningfulness. This, in turn, requires people to be able to recognise their sensations and join them to their lived experiences. Reflection and analysis are best accomplished with distance from one’s immediate daily life. Financial scarcity, together with other difficulties one is facing in life, decrease flexibility in a person’s emotional life and delay the processing and regulation of emotions. Creative group activities may increase this flexibility as it distances people from their narrow and difficult daily lives. It is concerned with “clearing your mind and relaxing” (I2).

At times, reflection involves looking back at past events. Sometimes the experience of significance makes people see their past from a different perspective:

Music and all of these things are, like, everyone listens to music and so if only I had realised (sighs) to, like, make use of art when I was going through difficult times and was numbing myself with alcohol. (I2)

Music, movement, activities in nature or making things with one’s hands help people move their thoughts away from their everyday reality. For one of the interviewees, horses signified freedom, acceptance and trust and time for oneself:

“I always need to, like, go outdoors, it is this thing, like, that they call time for yourself” (I1).

The interview data reveals how playing music can help people let go of their stress and anxiety. Below, interviewee I3 describes this as a state detached from the present moment which both relaxes and revitalises the person.

And then, when we were playing music there, I was a bit like, I wonder if this is gonna work, and then the second time around it started to be pretty fun and when I found an instrument that suited me better and closed my eyes, I actually got this [feeling] that I was focusing, only heard the music and forgot about all the rest—Well, the way I feel is that it was a very good thing and that you could do it sometimes as I am kind of prone to stress and being nervous about things and can’t always focus on the moment in a way that I’d be doing things and could just float in this sort of spaceless space and moment and would only have the sound there or whatever it might be.—And it would relax you or similarly perk you up—so probably at times like evenings you could do that with some suitable piece of music or somehow do it in this other way to relax you. (I3)

Listening to music, experiencing colours and spending time with animals provide a sense of trust and being accepted. They provide moments of freedom that push the daily life that causes pressure further away and allows one to feel a moment of calm. Interestingly enough, calmness and rest appeared to lie at the core of creativity. Our data indicate that creativity brings content to life and that something would be missing from life without it.

“It would be pretty empty, an empty life—“(I9).

One of the interviewees (I7) explained how playing in a band allowed him to reach a carefree flow state. In this situation, he does not need to pay particular attention to playing music as it comes naturally. Playing music combines different instruments, rhythms and melodies into an entity where all components complement one another. It makes people forget themselves and even the fact that they are playing music. Playing music occurs as if by itself, and this interviewee feels carefree and enjoys the situation. In a shared musical process, the different ingredients of life are intertwined at least metaphorically. Polyphony can result in a cohesive song. Similarly, an entity and meaning can be perceived from the chaos of daily life.

–So many different kinds of sounds are created and then you get more of this polyphony, where different rhythms are played with different instruments which can even play different melodies. And they get mixed up, or not mixed, but complement this. (I7)

These findings indicate how being within a safe distance from the daily reality, an opportunity to negotiate meanings and experience meaningfulness is opened. Negotiation is a phase of the creative process that fosters the experience of the uniqueness of one’s life as a stage for personal meanings. Creative play and an opportunity to shape the meanings in the narrative of one’s life and painting the story in a particular light also affect how the person sees their future and the opportunities provided by it.

5. Conclusion

This research explored social work clients’ experiences of creativity in their lives. According to this research, creativity and creative activities facilitate and enable the reconstructing of life narratives. This process redirects agency and enhances well-being.

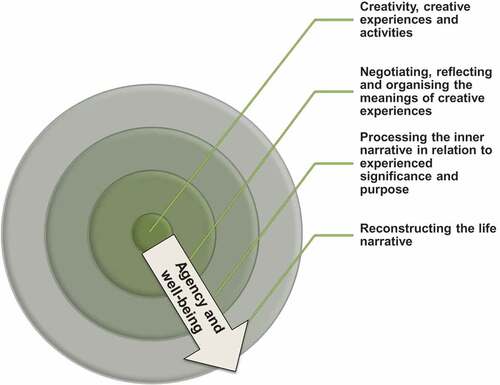

The findings of this study reveal four key aspects of how creativity is perceived and experienced as part of life, what kinds of meanings these experiences carry and what their significance is for narratives in people’s lives. Based on these results, the process of creativity enhancing the reconstruction of one’s life narrative can be conceptualised. These results are illustrated in Figures and .

These are: 1) understanding life and oneself through creativity, 2) creative experiences fostering feelings of significance and purpose, 3) constructing meaningfulness in creative group activities and 4) creativity in everyday life and as a spiritual dimension. Creativity is vital for (re)constructing life narratives.

As a research result of this study, we present a conceptualisation of how creativity enhances the reconstruction of the life narrative. This process subsequently redirects agency and enhances well-being. This is shown in Figure .

The meanings of the creative experiences for the interviewees seem consistent in this research. These meanings are related to: (1) organising and making sense of experiences; in other words, increasing a sense of coherence; (2) experiencing significance and purpose in connection with others; and 3) negotiating meanings, constructing meaningfulness and reconstructing the life narrative.

This research benefited from the separation of the three facets of meaningfulness proposed by Martela and Steger (Citation2016). Just as they point out, coherence seems to play a cognitive role in creativity-related meaning-making processes, while both significance and purpose take an evaluative role in creative processes, strengthening meaningfulness and supporting the reconstruction of narratives.

By combining Martela and Steger’s (Citation2016) insights into meaningfulness with the narrative approach proposed by Hänninen (Citation2004), we gained information on how coherence, significance and purpose are actualised in creative activities, and how this process can provide support in reconstructing life narratives.

Both meanings and meaningfulness are usually constructed in interaction between human beings. However, in the case of prolonged scarcity, opportunities to take part in interpersonal interaction or social life may decrease. In addition to this, the ability to take distance from intra- and interpersonal reactions may weaken in the long run. According to recent neurophysiological research (Moser et al., Citation2017), taking mental distance from difficult experiences is key when reducing brain stress. Creativity can enable taking distance from fear, anxiety and stress. We see that distancing oneself from everyday hardships in life may provide opportunities for new insights, and in this way, it simultaneously makes it possible to change one’s attitude to be more self-compassionate, for instance.

Figure illustrates the above-mentioned process. The innermost circle presents the input of creativity. It acts as a catalyst for the second circle, where the organisation of creativity-related meanings happens, and cognition-driven coherence is constructed when, for instance, one becomes aware of affects and the reactions caused by them, and one learns to regulate them. In the third circle, the inner narrative is processed in relation to experienced significance and purpose.

By “narrative circulation” Hänninen (Citation2004) clarifies the process whereby experiences are negotiated within our mental schemas. Changes in the inner narrative may subsequently influence how one represents one’s presence (the told narrative) by utilising cultural meanings, such as narrative patterns, songs, visual representations, art or other cultural products. In other words, there is a strong likelihood that creative group activities in a confidential and encouraging environment may broaden representations and in this way bring new opportunities and perspectives to life.

Our study complements this knowledge by integrating three facets of meaningfulness into the process of constructing our life narratives. In light of the results of The Tune of My Life research, creativity can be captured both as a driving force for the narrative construction process and as an environment that enables this. The results indicate that creativity-related activities enable us to process our life narrative and thus support (re)constructing these life narratives.

Sociologists have verbalised agency through the terms “creativity” (Heiskala, Citation1997), “reflection” (Lister, Citation2004) and “awareness” (Hoggett, Citation2001). An agent exercises power, while a non-agent is prone to be governed by others and daily routines. Creative activities enable people to negotiate, reflect upon, become aware of and organise meaning in life. This forms an environment for reconstructing life narratives, which subsequently redirects agency and enhances well-being. In future research, it would be interesting to focus on analysing the experiences of creative activities in social work through the lens of agency. This would complement the understanding of the benefits of creative approaches in social work.

In this research, the creativity-related experiences of the interviewees were mainly very positive; even slightly challenging situations were discussed positively in the end. This could be explained by the voluntary selection of the informants. People who regard creativity as a positive activity were probably keener to participate in the data gathering than those with negative attitudes. This is to say, experiences concerning creativity may present anxious notions, although they were not visible in our data. For instance, sad music may raise negative emotions (Peltola & Eerola, Citation2016), and these must be taken into consideration when utilising creativity in social work or working with people in general. This calls for profound education on methods and a professional approach.

The results of this research encourage further research focusing on studying the experiences of social work clients. This would widen the understanding that creative activities could play a greater role in developing client-centered services for people in a vulnerable position.

Acknowledgements

The study The Tune of My Life was conducted by Metropolia University of Applied Sciences in Helsinki and was part of the national development project on social inclusion (SOSKU) in Finland.

The authors would like to express their deepest thanks to those social work clients who participated in the research as interviewees. The authors would also like to acknowledge Minna Lamppu, Päivi Rahmel, Elina Ala-Nikkola, Venla Katila and Maria Mäntylä for their contribution to data gathering. This work was undertaken as part of SOSKU in Finland.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura Huhtinen-Hildén

Laura Huhtinen-Hildén (Ph.D. MMus, music therapist) works at Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences as a senior lecturer, researcher and head of Early Childhood Music Education and Community Music. Her research focuses on using creativity, creative activities and arts to enhance well-being and inclusion as well as generating knowledge about professional skills and approaches required. She is the leading author of a recent book ‘Taking a Learner-centred Approach to Music Education- Pedagogical Pathways’.

Anna-Maria Isola (Ph.D in social policy) works at National Institute for Health and Welfare as Research manager. She leads a research project that includes topics concerning capabilities, meaningfulness, recognition, participation and inclusion in subjective poverty in Finland. She is interested in creativity and empowerment in social and community work and pedagogy of hope, among other things. Isola is qualified in follow-up qualitative studies and discourse analysis.

References

- Aaltonen, T., & Leimumäki, A. (2010). Kokemus ja kerronnallisuus − kaksi luentaa. In J. Ruusuvuori, P. Nikander, & M. Hyvärinen (Eds.), Haastattelun analyysi (pp. 119–17). Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Baumeister, R. F. (1991). The meanings of life. London: The Guilford Press.

- Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. G. (2002). Identity formation, agency, and culture: A social psychological synthesis. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Craft, A. (2001). Little C creativity. In A. Craft, B. Jeffrey, & M. Leibling (Eds.), Creativity in education (pp. 45–61). London: Continuum.

- Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2008). The phenomenological mind. An introduction to philosophy of mind and cognitive science. London: Routledge.

- Giorgi, A. (1985). Sketch of a psychological phenomeological method. In A. Giorgi (Ed.), Phenomenology and psychological research (pp. 8–22). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

- Giorgi, A. (1997). The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 28(2), 235–260. doi:10.1163/156916297X00103

- Giorgi, A. (2012). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 43, 3–12. doi:10.1163/156916212X632934

- Groth, C. (2017). Making sense through hands: design and craft practice analyzed as embodied cognition. Doctoral Dissertations, 1/2017. Aalto University publication series.

- Hänninen, V. (2004). A model of narrative circulation. Narrative Inquiry, 14(1), 69–85. doi:10.1075/ni.14.1

- Heiskala, R. (1997). Society as semiosis: Neostructuralist theory of culture and society. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Hoggett, P. (2001). Agency, rationality and social policy. Journal of Social Policy, 30(1), 37–56.

- Karvonen, A., Kykyri, V.-L., Kaartinen, J., Penttonen, M., & Seikkula, J. (2015). Sympathetic nervous system synchrony in couple therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42, 369–563. doi:10.1111/jmft.12152

- Koskiniemi, A., & Perttula, J. (2013). Team leaders’ experiences with receiving positive feedback. Tiltai, 62(1), 59–74.

- Koskiniemi, A., Vakkala, H., & Pietiläinen, V. (2018). Leader identity development in healthcare: An existential-phenomenological study. Leadership in Health Services. doi:10.1108/LHS-06-2017-0039

- Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews. An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE.

- Latomaa, T. (2009). Ymmärtävä psykologia: Psykologia rekonstruktiivisena tieteenä. In J. Perttula & T. Latomaa (Eds.), Kokemuksen tutkimus. Merkitys − tulkinta − ymmärtäminen (pp. 17–89). Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopistokustannus.

- Lehtomaa, M. (2009). Fenomenologinen kokemuksen tutkimus: Haastattelu, analyysi ja ymmärtäminen. In J. Perttula & T. Latomaa (Eds.), Kokemuksen tutkimus. Merkitys − tulkinta − ymmärtäminen (pp. 163–194). Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopistokustannus.

- Lister, R. (2004). A politics of recognition and respect: Involving people with experience of poverty in decision-making that affects their lives. In J. Andersen & B. Siim (Eds.), The politics of inclusion and empowerment. Gender, class and citizenship (pp. 116–138). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, significance and purpose. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

- Moser, J., Dougherty, A., Mattson, W. I., Katz, B., Moran, T. P., Guevarra, D., … Kross, M. G. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific Reports 7/Article 4519.

- Myllyneva, A. (2016). Psychophysiological responses to eye contact. Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1695. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. Retrieved from https://tampub.uta.fi/handle/10024/99599

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Peltola, H.-R., & Eerola, T. (2016). Fifty shades of blue: Classification of music-evoked sadness. Musicae Scientiae, 20(1), 84–102. doi:10.1177/1029864915611206

- Perttula, J. (1995). Kokemus psykologisena tutkimuskohteena. Johdatus fenomenologiseen psykologiaan. Tampere: SUFI.

- Perttula, J. (1998). The experienced life-fabrics of young men. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Perttula, J. (2000). Kokemuksesta tiedoksi: Fenomenologisen metodin uudelleen muotoilua. Kasvatus, 31(5), 428–442.

- Perttula, J. (2009). Kokemus ja kokemuksen tutkimus: Fenomenologisen erityistieteen teoria. In J. Perttula & T. Latomaa (Eds.), Kokemuksen tutkimus. Merkitys – Tulkinta – Ymmärtäminen (pp. 115–163). Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopistokustannus.

- Rauhala, L. (2005). Conception of a Man in a Humane Work [Ihmiskäsitys Ihmistyössä]. Helsinki: Helsinki University.

- Shouse, E. (2005). Feeling, emotion, affect. M/C Journal, 8(6). Retrieved from http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0512/03-shouse.php

- Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Van Manen, M. (2007). Phenomenology of practice. Phenomenology & Practice, 1(1), 11–30.

- Wilson, A., & Golonka, S. (2013). Embodied cognition is not what you think it is. Hypothesis and theory article. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 58. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00058