Abstract

This paper addresses the question whether complementary currencies can help us think and practice politics in new and different ways which contribute to democratic change and civic empowerment in our times. The space created by the Sardex complementary currency circuit in Sardinia (2009-to date) seems to leave enough room for the emergence of a collective micropolitical consciousness. At the same time, the design of a technological and financial infrastructure is also an alternative political, or “alter-political” choice. Both are alternative to hegemonic politics and to typical modes of mobilization and contestation. Thus, the Sardex circuit can best be understood as an alter-political combination of the bottom-up micropolitics of personal interactions within the circuit and of the politics of technology implicit in the top-down design of the technological and financial infrastructure underpinning the circuit. The Sardex experience suggests that a market that mediates the (local) real economy only and shuts out the financial economy can provide economic sustainability by supporting SMEs, supply a shield against the adverse effects of financial crises, and counteract the fetishization of money by disclosing daily its roots in social construction within a controlled environment of mutual responsibility, solidarity, and trust. We broached the Sardex currency and circuit in such terms in order to illustrate a significant and effective instance of alter-politics in our times and also to indicate, more specifically, community financial innovations which could be taken up and re-deployed to democratize or “commonify” local economies.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Contemporary societies are faced with daunting political challenges. Political systems and ruling elites are largely unresponsive to social needs and have so far proven unable to face up to these challenges for the common good. Collective mobilizations have not effectively tackled the broader crises, hence the need to experiment also with new and different forms of political intervention. The paper looks at the Sardex complementary currency as an example of alternative politics, which partly transcends from mainstream politics. Sardex is alter-political because by reconfiguring the practices of money creation and distribution it affects a wide range of social relations. The Sardex circuit can be understood as an alter-political combination of the bottom-up micro-politics of personal interactions and the politics of technology of the top-down design of the technological and financial infrastructure underpinning the circuit. Sardex illustrates a significant and effective instance of alter-politics in our times and, more specifically, community financial innovations which could be taken up and re-deployed to democratize or “commonify” local economies.

1. Introduction

This paper addresses the question whether complementary currencies can help us think and practice politics in new and different ways which contribute to democratic change and civic empowerment in our times. More specifically, can they help us foster transformation towards a society in which common goods are collectively administered in egalitarian and participatory ways which go beyond the logics of both capitalist markets with their private goods and the top-down state management of public goods? To start broaching these questions, the present paper will explore the “success story” of the Sardex complementary currency in Sardinia (2009-to date). We chose Sardex to address these questions because it is a success story, so far, and has the potential to both sustain itself over time and expand.

Complementary currencies, by design, do not aim to supplant legal tender but, rather, cater to some of the parts of the economy that legal tender for one reason or another is not able to support. Complementary currencies have emerged in the boundary space at the edges of nation states and macroeconomic policy. In fact, they tend to emerge during financial crises, when the failure of the dominant economic system to serve the weakest parts of the economy stimulates the latter into action, often through a creative mixture of social, entrepreneurial, and monetary innovation. Because their very existence challenges the ontological primacy of legal tender and its legitimacy as a cultural monopoly, complementary currencies are necessarily political—or, according to the definition we favour in this paper, “alter-political”.

There are many types of community, local, parallel, alternative, or complementary currencies, which we refer to collectively as “CCs” (Blanc, Citation2011; Kennedy, Lietaer, & Rogers, Citation2012; Longhurst & Seyfang, Citation2011; Seyfang & Longhurst, Citation2013). As proposed by Blanc (Citation2011), their typology can be classified as “territorial”, “community”, or “economic” depending on the focus of their purpose and what they seek to define, protect, and strengthen. In this classification, Sardex is mainly “economic”, but also significantly “territorial” and with varying perceptions of the “community” aspect across its membership.

Drawing on the research discussed in this paper, the preliminary answer to the questions above is that democratic change and civic empowerment call for an economically sustainable model just as everything else. In other words, the findings of the paper indicate that community economies can be an effective way to link the properties of a fair and environmentally sustainable society to the rest of the economy, but they cannot operate in isolation. Rather, the Sardex experience suggests that, broadly speaking, a market that mediates the (local) real economy only, and shuts out the financial economy, appears to provide economic sustainability by supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), while also supplying a shield against the adverse effects of financial crises, credit rationing, speculation, etc. This act of establishing the circuit, in fact, was performed with a conscious political vision to close off the speculative behaviour of the financial economy (mainly through the imposition of 0% interest and non-convertibilityFootnote1) that had caused the crisis in the first place and, therefore, to promote economic relations rooted in the local real economy.

The design of a technological and financial infrastructure that is able to guarantee such a structural condition is also an alternative political, or “alter-political” choice, of a type that can be understood through Andrew Feenberg’s Critical Theory of Technology (Feenberg, Citation1999). The Sardex experience indicates that the properties of the complementary currency are paramount for achieving these effects. More precisely, it implies that a currency, far from being a neutral veil, can be regarded as a technology that can be designed to achieve particular effects. For example, these structural constraints appear to make it easier for a local real-economy market to couple constructively to some Third-Sector actors and to a limited conception of community economies. Finally, since the Sardex circuit is a very small part of the economy within which it is embedded, any such conclusion should be qualified as a trend with a promising potential for change that is however contingent on its ability to scale.

Sardex is an electronic, mainly business-to-business (B2B) mutual credit circuit that started operating in Sardinia in 2009 and was formed by an s.r.l. (Ltd.) for-profit company of the same name, in direct response to the last crisis (Littera, Sartori, Dini, & Antoniadis, Citation2017). It is a complementary currency that is used alongside the Euro and quantifies the zero-interest credit that the participating small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) extend to one another, mutually. It was inspired by a mutual credit circuit founded in Switzerland in 1934 during the Great Depression, the WIR, short for “wirtschaftsring”, or “economic circle”, but also the pronoun “we” in German. Sardex is based on the early (1934–1952) WIR model, when WIR was also entirely zero-interest (Studer, Citation1998). Sardex is the name given to the Sardex credits as a unit of account, where 1 Sardex = 1 Euro; to the company that provides the credit-clearing service, now Sardex S.p.A. (“joint-stock”) after the latest round of venture capital funding; to the economic circle or “circuit” (Sartori & Dini, Citation2016; Zelizer, Citation2005); and to the online environment.Footnote2 At the end of 2018, the Sardex circuit in Sardinia had reached 3200 company members and a transaction volume of 43m Euros for 2018.Footnote3

The paper argues that although Sardex can be regarded as an alter-political project, it initially made no assumptions about its members espousing a specific and fully-fledged political vision in the short or long term or, indeed, about them even being aware of it. In fact, the Sardex founders consciously prioritized the economic dimension, even while highlighting the importance of trust and the social dimension. Similarly, although Third Sector concerns are close to the heart of the Sardex founders, they are not at the centre of Sardex S.p.A.’s business model. Therefore, we don’t claim that Sardex itself is a community social economy or a “commons”. What we can say for sure, as a starting point, is that Sardex is a market economy strongly rooted in the local real economy and isolated, by design, from the dominant financial sector.

And yet, the founders’ long-term vision remains not only one of economic empowerment of SMEs but also of participatory governance of the socio-economic space. The circuit is an informal association today, but the founders hope that it will eventually become a legal entity co-owned by its members. Equally important, one of the objectives of the Sardex initiative is to maximize the synergy with the non-profit sector, i.e. with social-benefit, cultural, and artistic associations (Dini, Sartori, & Motta, Citation2014-16). In our limited set of interviews we have found that such synergy is already present, on a very practical level, for a few particularly well-placed actors such as theatres and museums (Kioupkiolis & Dini, Citation2018). Thus, the extension to more challenging scenarios such as poor neighbourhoods with high unemployment, an informal economy, drug use, and a high proportion of migrants seems almost within range and is an active current area of research and development (Kioupkiolis & Dini, Citation2018).

In this paper, therefore, we probe the peculiar alter-political choice of the Sardex founders to steer the circuit on a course that has so far remained consistently on the boundary between the rentier-capitalist economy and local community economies. We argue that this approach appears to be working, in the sense that the space created by the circuit seems to leave enough room for the emergence of a collective political consciousness, a phenomenon that is elucidated by micropolitical accounts (see, among others, North, Citation2007). We see this process as rooted in the circuit members’ awareness that Sardex affords them a greater freedom in their socio-economic life and an ampler control over it. We further argue that through the socio-economic interactions within the circuit the members cannot help seeing this greater freedom and control in each other. Finally, the choice on the part of the Sardex founders to amplify those aspects that resonate with traditional Sardinian values of solidarity and reciprocity may account for the success of the initiative, and may also offer hints for how similar initiatives might be adapted to different socio-economic and cultural contexts.

One of the overarching points of this paper is that embodying political choices in the design of the financial platform (e.g. zero interest, no convertibility) is enabling Sardex to achieve its founders’ alter-political vision even while remaining focused on pragmatic, business-based considerations. It is for this reason that their initiative and the Sardex circuit can best be understood as an alter-political combination of bottom-up micropolitics, which operates at the level of personal interactions within the circuit, and Feenberg’s politics of technology, which in this context operates at the level of the top-down design of the technological and financial infrastructure underpinning the circuit and that forms or influences social relations thereafter. In short, Sardex is able to illuminate local—and global—power circulation merely by showing how a fairer form of the monetary and financial system can work and how communities can build the power to construct and govern such systems for themselves.

The next section describes the methodological aspects of the research conducted, with some reflexivity considerations. Section 3 introduces the concept of “alternative politics” conceptually and in the literature. It then discusses the roots of the initiative, in an attempt to contextualize where the Sardex alter-political vision originated from. It discusses how Sardex as a circuit and economic practice embodies an alter-political intervention because it acts on local economic and social relationships to shift them towards a certain direction that we broadly associate with community economies and the commons—of greater reciprocity, collaboration, local empowerment, and trust. It relates these properties to a conception of money rooted in sociological monetary theory. Finally, the paper describes Sardex’s interaction with the neoliberal economy. Section 4 discusses some of the more difficult aspects of running the circuit, such as free-riding, hoarding, gaming the system, and rule compliance, and provides some economic data that can help understand the importance of the circuit within the Sardinian economic context. Section 5 provides a critical discussion of Sardex from the point of view of micropolitics of social change, and Section 6 draws some conclusions.

2. Methodology

The paper relies on a combination of theoretical analysis and qualitative empirical data in the form of semi-structured interviews performed in multiple tranches between 2014 and 2018 (Dini et al., Citation2014-2016; Kioupkiolis & Dini, Citation2018). To clarify the reflexive dimension of the research, we should point out in addition that, as a consultant for Sardex S.p.A., Paolo Dini has spent half of his time on the Sardex premises since August 2016, on and off at intervals of approximately 3 weeks each. During the whole period, i.e. also when he was not on site, he worked on all technical and non-technical aspects of the circuit and with most of the Sardex employees and founders, at all levels of the organization. During this time, he has also come into contact with many circuit members at a number of public events and through private encounters and transactions. Paolo Dini is himself a member of the Business-to-Employee (B2E) programme and holds a Sardex credits account which he uses regularly for a wide range of retail and service transactions.Footnote4 Although these activities were not set up specifically as an effort of immersive ethnography, to some extent that is what they have resulted in, providing a view from the inside of the circuit and the company that runs it that has influenced to some extent some of the observations and claims made in this paper. Even keeping all this in mind, this paper remains more a critical-theoretical research effort than an empirically-based paper.

3. Theory and construction of the alter-politics of Sardex

3.1. General introduction to alternative politics

To grasp Sardex as another way of engaging in political action that enhances civic empowerment and social values, including collaboration and sustainability, we need to introduce a conception of the political which is richer and broader than its conventional understanding. In the standard view, politics is identified with the art of government and, primarily in modernity, with the government of a nation-state. In “the everyday use of the term … people are said to be ‘in politics’ when they hold public office, or to be ‘entering politics’ when they seek to do so. It is also a definition that academic political science has helped to perpetuate” (Heywood, Citation2013, p. 3). Sardex would not qualify as a political intervention and activity, based on this interpretation, since its creation and operation are not about holding public office or taking action through the state.

However, all over the 20th century up until the present day, political thought and action of various stripes has undertaken a “decentering” of the political away from its concentration on the state, national government and the formal political system. Schmitt (Citation1932–2007) has inaugurated, perhaps, the shift away from the state in 20th century political thought in the West by noting that the equation politics = state “becomes erroneous and deceptive at exactly the moment when state and society penetrate each other” (Schmitt, Citation1932–2007, p. 2). For Schmitt, rather, “The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy … which denotes the utmost degree of intensity of a union or separation, of an association or dissociation” (Schmitt, Citation1932–2007, p. 26). Thus understood, the political may crop up in any social field beyond the state. Any social relations can become political if a conflict occurs which is intense enough to split the members of the relation into friend and enemy (Schmitt, Citation1932–2007, pp. 37–38).

From a different slant, Lefort (Citation1986, pp. 276–278, 310–311, 322–323) has located the political in the “generative principles” of different figures of society, its particular mode of instituting and constructing society. The political “mise en forme” of human coexistence is at the same time a signification (“mise en sens”) and representation or staging (“mise en scène”) of social relations (Lefort, Citation1986, pp. 280–282).

The notion that politics is not reducible to the state and public activity in the political system has been famously championed by the feminist movement in the ‘60s through the emblematic feminist motto “the personal is political”. This implied that there are “political dimensions to private life, that power relations shaped life in marriage, in the kitchen, the bedroom, the nursery, and at work” (Rosen in Lee, Citation2007, p. 163). The political is deployed thus “in the broad sense of the word as having to do with power relationships, not the narrow sense of electoral politics” (Hanisch, Citation2006, p. 1). The “personal is political” entails, also, that cultural norms, social and economic structures are realized and reproduced through individual action (Butler, Citation1988, p. 522). The feminist movement configured modes of political thought and action in line with this politicization of the everyday, involving “average” women in their everyday lives through practices such as “consciousness-raising”. By exchanging personal experiences and through collective discussion around common concerns, this method of critical thinking in concert enhanced reflection on the political aspects of personal life and everyday oppression, promoting change in patriarchal norms and subjectivities, in the present tense and from below (Butler, Citation1988, pp. 523–524; Hanisch, Citation2006; Lee, Citation2007, pp. 165–166).

From the 1960s onwards, endeavours to imagine and practice politics beyond or outside the state have proliferated in multiple fields of inquiry, from anthropology (e.g. Scott, Citation1990), sociology (e.g. Beck, Citation1992) and political ecology (e.g. Bookchin, Citation1982) to social movement studies (e.g. Della Porta & Rucht, Citation2015), neo-anarchism (e.g. Newman, Citation2011) and “post-structuralist” French philosophy (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Foucault, Citation1980).

Despite this diversity of ideas and their divergences from state-centred notions, a common thread runs across different senses of the political, from the most standard politics of the nation-state and Schmitt’s friend/enemy antagonism to the “personal politics” of second-wave feminism. In all these cases, “the political” pertains to social activity which deliberately intervenes in existing social relations, structures and subjectivities in order to intentionally shape them by challenging them, transforming them, displacing them, managing them or upholding them against challenges. From this broader perspective, political activity can take place both in the formal political systems and underneath, outside, against and beyond them, on any micro-, meso- or macro-scale of social life, in more or less institutionalized and visible social spaces and relations in any social field. In the manner of deliberate collective action on social structures and subjectivities, the political encompasses both the “management of collective affairs” by governments, as well as ordinary, face-to-face social interactions and attempts at “coping” with everyday problems.

In this perspective, then, “low” politics and “micro”-political activities in social exchanges, performances and relations of everyday life are also recognized as political. But their impact on broader social systems is not predetermined. Likewise, it remains open to debate whether alternative politics which partly transcends, transforms, challenges, escapes or deviates from the ruling and mainstream modes of political action affects only certain interactions and structures, or it can combine with other political energies to initiate systemic transformations or large-scale social struggles.

The conception of “alter-politics” that we deploy here resonates deeply with Gibson-Graham’s (Citation2006) take on the “politics of economic possibility” and the understanding of social formations that informs it. This is a conception inspired and bolstered by second-wave feminism, whose local, decentralized and un-coordinated grassroots action brought about wide-ranging social transformation by beginning in the here and now, without a prior large-scale systemic revolution (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, p. xxiv). In their words,

a politics of possibility rests on an enlarged space of decision and a vision that the world is not governed by some abstract, commanding force or global form of sovereignty. This does not preclude recognizing sedimentations of practice that have an aura of durability and the look of ‘structures’ … .It is, rather, to question the claims of truth and universality that accompany any ontological rigidity and to render these claims projects for empirical investigation and theoretical re-visioning. (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, p. xxxiii)

Gibson-Graham offer a reading of social formations, and the economy more specifically, which underpins this idea of an alternative politics of possibility. The dominant structural forces themselves are contingent outcomes of action, which are pushed and pulled in different directions by other determinations (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, pp. xxiii-xxxi). This view questions “the” economy as a singular and uniform capitalist system, representing it instead as “diverse economies”, a zone of cohabitation and contention among different economic forms of transaction, labour, production and enterprise, from “mainstream capitalist” private corporations to “alternative market” public companies, communal co-operatives and non-profits (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, pp. xxi-xxii, 60, 65, 73).

From this angle, “noncapitalist” or non-mainstream capitalist practices (such as Sardex), which usually “languish on the margins of economic representation”, can be brought to light and seen as co-existing in different ways within ruling capitalist economies in internally diverse economic contexts (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, p. xxxii). The alternative politics of possibility “suggest the ever-present opportunity for local transformation that does not require (though it does not preclude and indeed promotes) transformation at larger scales” (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, p. xxiv). Possibilities multiply along with uncertainties. Alternative practices are affirmed as a foothold to build upon so as to advance broader economic and social change, questioning the assumption that there is a global system of power which must be addressed and broken apart before local transformative action occurs and gains traction (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, pp. xxx-xxxi). Immersed in diverse economies and internally heterogeneous social formations, alter-politics is entangled with other forms and logics, including mainstream ones. Hence, it is hybrid, impure and pragmatic, collaborating, for instance, with governments and international agencies which may not share its goals and values. Yet, alter-politics refuses to see co-optation as a necessary consequence, engaging often in exercises of self-examination, reflection and self-cultivation which counter co-optation (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006, p. xxvi).

3.2. The alter-politics of Sardex

To connect Sardex to the alter-politics perspective, we should start by noting that the Sardex system reconfigures the practices of money creation and distribution insofar as it generates its own currency based on zero-interest mutual credit. It is this key innovation that affects and transfigures a wide range of social relations, from the power relations between SMEs and banks to the patterns of competition and collaboration between local businesses. However, to grasp the different alter-political layers of Sardex, it is necessary to introduce two further analytic distinctions at the outset.

First, we can separate the subjects into the people running the Sardex S.p.A. company and the members of the circuit. Although the founders and the company employees in general engage in a level of innovation that always has an impact on the economic and social behaviour of the members, their main alter-political contribution was at the beginning, when they set up a system of rules formalized through business contracts with the members and through the algorithms of the electronic platform. The founders were also conscious of the importance of building trust and of nurturing social relations between the members. In broad terms, therefore, the alter-political intervention in the form of financial model, technology platform, and company structure on the part of the founders could be said to reflect a value-laden, critical, and creative development of technology grasped by Feenberg’s critical theory (Feenberg, Citation1999). As such, it was greatest at the start of the circuit and is gradually decreasing over time.

Among the innovations being considered for the future is the gradual shift towards a model of participatory governance by the members, with eventual partial collective ownership of parts of the company as it continues to grow and to evolve into a larger and more diversified company and set of circuits. Mirroring the gradual discovery of the social dimension by members who join the circuit for economic reasons, the eventual introduction of a governance framework in the original Sardex circuit and in future circuits suggests that the alter-political contribution of the circuit members, on the other hand, is gradually increasing, over time, and exhibiting a more deliberative and participatory character.

Second, since Sardex is an electronic currency, it is crucial to realize that the more evident alter-political aspects of the initiative were always intertwined with a less visible but no less important technological dimension. Aside from the obvious role of Internet and web technology in making the electronic currency and the transactions possible, the point is more about the architecture and the properties of the technology itself. For example, Sardex is currently undergoing a transition from a centralized system to a blockchain-based transactional platform (Dini, Littera, Carboni, & Hirsch, Citation2019). The possibility of distributing the transaction validation function to peers hosted by other organizations makes the blockchain architecture implicitly more amenable to decentralization and, therefore, compatible with the long-term Sardex vision of distributed circuit(s) governance.

The libertarian overtones of most public blockchains are an overt example of the politics of technology in Feenberg’s (Citation1999) theory. The point we are making here is more subtle, however, because it goes beyond the architecture of web environment to a more general conception of infrastructure. Namely, by “technology” we are also referring to the financial layer or model that sits on top of the electronic transactional platform and sets the rules by which it operates. At a deeper ontological level, the ultimate financial infrastructure is the medium of exchange itself.

3.3. Sardex’s alter-political vision: the roots of the initiative and the nature of money

The founders’ vision of the Sardex “project” revolves around mutual trust, reciprocity, solidarity and local empowerment. It grew out of a mixture of personal, economic, cultural, and political motivations. Some of the founders were working abroad and wanted to move back home (Littera et al., Citation2017). Since there were no jobs in Sardinia, they were determined to “invent” one for themselves in order to be able to reverse-migrate to Sardinia. They liked the principle of mutualism that the WIR founders—all SME entrepreneurs—expressed in 1934 by refusing to give up in the face of the drying up of credit in the banking sector. Their decision to start giving credit to each other on a strong basis of mutual trust and solidarity resonated strongly with the Sardex founders, who decided it was worth trying to establish a similar system in Sardinia.

The reasons for this resonance were in part cultural-historical. The founders were keenly aware of the Sardinian historical tradition of reciprocity and solidarity, which was gradually weakened after 1820. That year the Savoys of Turin (who had ruled Sardinia since 1720) passed a law that allowed anyone who could to appropriate the common land into enclosures (“chiudende”, in Sardinian), enacting a similar privatization process that had taken place in the UK two to three centuries before (Onnis, Citation2015). In other words, in the minds of the Sardex founders, the advent of Modernity and the later unification with Italy destroyed the social and cultural fabric that had kept Sardinia’s society together in a constructive balance between reciprocity, a commons-based economy, and a market for thousands of years (Onnis, Citation2015, pp. 20, 21, 61, 66–68, 88, 103–104, 154, 181). Perhaps even more painful is the fact that since approximately 1400 Sardinia has been a subaltern culture, first of the Spanish empire and, since 1720, of the Savoys and of the Italian state after unification in 1871.

Today Sardinia is the poorest Italian region, whose GDP/capita is 2/3 of the Italian average. The advent of the crisis, which hit Sardinia particularly hard, was therefore seen as yet another hardship imposed on the island through no fault of its inhabitants. Quite apart from independentist feelings which, although present, do not play a central role in the lives of most Sardex members, the above context and personal motivations coalesced into a strong desire to put an end to the profound unfairness Sardinia has endured for centuries merely on account of being a weak economy on the margins of the Italian and, more recently, the European economy.

These feelings found expression in what is arguably the most radical alter-political decision of the Sardex initiative: to espouse mutual credit as the monetary and financial model. As explained by Ingham (Citation2004), monetary theory is broadly divided between the Aristotelean commodity theory of money and the claim or credit theory. In the former, money emerges as a precious commodity such a gold that functions as a medium of exchange to facilitate barter exchange. By contrast, the credit theory explains how markets and economic exchanges worked before money was invented. As explained in Graeber’s anthropological account, before money was invented people in small-scale societies used credit and kept track of who owed what to whom, rather than engaging in direct barter (Graeber, Citation2011). Similar to the credit theory but with a more sociological emphasis, the institutional theory sees money as a social relation of credit and debt (Amato & Fantacci, Citation2012) “which exists independently of the production and exchange of commodities” (Ingham, Citation2004, p. 12) and which is formalised through the double-entry book-keeping method. As explained by Ingham, the nature of money as a social relation is anchored in its nature as debt since debt carries a moral imperative to be repaid, it requires trust to be extended, and it also entails a power differential between creditor and debtor.

More generally, according to some strands in sociological monetary theory, all money is debt, even though not all debt is money (Ingham, Citation2004).Footnote5 Thus, debt is the more general concept. In fact, a loan can consist of money that already exists (usual definition), or of money that is created at the time the loan is made, which is how banks create money “endogenously” (Douthwaite, Citation1999; Ingham, Citation2004; Werner, Citation2014; Wray, Citation1990). For any debt, the collateral guarantees to the lender that if the debt is not repaid the value of what was lent is not lost. The concept of collateral applies both when the money already exists as well as when it is created as an integral part of extending the loan. In the second case the collateral is called “backing”.

Thus, money can be generated in several different ways, which can be told apart by the kind of backing used in each. For example, before the advent of independent central banks, when the state paid its suppliers the future tax receipts provided the backing, and the negative entry in the ledger showed up as an increment in public debt (Knapp, Citation1924–1973). When banks issue mortgages, the backing is the market value of the house the mortgage buys and the negative entry is the amount of the debt that needs to be repaid, plus interest.Footnote6 Finally, in mutual credit systems like Sardex, money is created when a company “goes into the red” with respect to the circuit by a certain number of credits. The backing is the products and services which that company will sell over the next 12 months—in other words, the labour required to create the products and provide the services. Thus, in this last case the creation of money as social relation of credit and debt is related to the production of commodities, since they serve as its backing, but as we will see the social relation remains explicit throughout the life-cycle of a Sardex credit. Money created as a form of debt is then destroyed when the debt is repaid. This is true when the principal of a mortgage is repaid as well as when a Sardex member with a negative balance sells something and is paid by someone with a positive balance: in both cases the monetary mass decreases.

Even within just the sociology of money, this position raises multiple questions and qualms. For example, scholars like Mary Mellor (Citation2016; see also Bollier and Conaty Citation2015) point to deep flaws in how the money supply has been appropriated by the banking sector: on the one hand, through the issuance of private debt which favours the banks at the expense of working citizens; on the other hand, the “Janus-faced central bank” switches opportunistically between its private and public sector character depending on whether it is more expedient to support private-sector banks or create “debt-free money” through Quantitative Easing (QE). A double standard arises from the fact that QE has proven to benefit exclusively the financial sector while, at the same time, crushing austerity policies have been imposed to restrict public spending on essential services that support the weakest members of society. Mellor’s solution is to eliminate endogenous money creation by banks, i.e. private debt, and for the state to claim back the ability to create debt-free money from the central bank, and to allocate it democratically for the public good and as a public good. This is similar to the position of initiatives like Modern Monetary Theory and Positive Money.Footnote7

Sardex sheds a different light on money as debt because mutual credit amplifies and renders explicit relations of mutual indebtedness, disclosing possibilities of money creation and functioning which challenge Mellor’s single-minded rejection of the concept of debt as universally negative. Mellor’s perspective is indeed legitimized by the operation of the private banking and financial sectors. For example, mortgages are routinely sold on by the banks that issue them, thereby breaking the social relation that created them. At the other end of this relation, the fact that money is assignable debt (Ingham, Citation2004) means that, as it is spent multiple times, its nature as debt is soon forgotten and the Aristotelean perception of money as a precious commodity takes over as a form of reification. Finally, since the money is created by the banks at the time of the loan, they incur no opportunity cost in lending it. The consequent lack of legitimacy in charging interest on the loan exposes the gross inequality in this binary power relation and is another example of the lack of democratic accountability in the financial system that Mellor rightly laments.

However, without invalidating her critique of the neoliberal economy, the Sardex mutual credit system deconstructs these mechanisms: first, because the debt is not securitizable; second, because the credits are not convertible and remain local; third, because there is 0% interest on all (positive and negative) balances; finally, because its nature of a trust-based social relation is highlighted by rendering explicit the responsibility of an individual actor’s debt towards a circuit of equals. Sardex debt is not bilateral, it is a responsibility the debtor has towards the whole circuit. In short, Sardex helps to counter reification by disclosing on a daily basis the foundations of money in social construction. In this respect, it is very different from the dominant form of money generated by alien institutions (central banks etc.) in ways which lead the majority of the people to misrecognize its constructed character and to fetishize it. Thus, at moderate and carefully controlled levels and within a framework of mutual solidarity and responsibility based on trust, debt is not necessarily destructive. The Sardex experience shows that, on the contrary, it can be a very strong factor for economic resilience, it can strengthen social bonds and trust, and it can even make a significant contribution to the sustainability of local economies.

Whereas the institutional theory explains the creation and destruction of money, the Aristotelean commodity theory applies as it is repeatedly spent in economic transactions. Thus, the sociological theory of money is not “needed” in the middle, and longest, phase of money’s life-cycle. Therefore, in this phase the separation of the sociological from the economic perspective does not seem like a big loss of explanatory power. This “divorce”, however, leaves the creation of money unexplained for economists, and carries more negative consequences. For example, since its creation is best understood through a sociological lens, the power aggregation that goes with it also goes unremarked by the neoclassical perspective. In fact, Ingham’s sociological perspective highlights the “dual nature” of money as regards power: in addition to the power that the possession of money confers on its holder, “the process of the production of money in its different forms is inherently a source of power” (Ingham, Citation2004: 4, original emphasis). Thus, the struggle for dominance between the state’s creditors (banking sector and bond holders) on the one hand, and the state’s debtors (entrepreneurs, consumers and tax-payers) on the other (Ibid: 31, 81, 150, 202), can endanger the democratic institutions of neoliberal nation-states, as Mellor (Citation2016) argues.Footnote8 Thus, whereas in the neoclassical theory the Unit of Account, Medium of Exchange, and Store of Value “textbook functions” of money are equally strong, and whereas the sociological theory explains creation and destruction and argues for the logical primacy of the Unit of Account function but is not prescriptive about the other two (Ingham, Citation2004), Sardex is compatible with the sociological theory but makes the Store of Value function weaker by design, by enforcing zero interest on all balances.

Finally, the exploding world of crypto-currencies provides a range of monetary characteristics. Bitcoin is a poor Medium of Exchange or Store of Value because of its high volatility, and it is not created as a form of social debt: it is essentially a speculative instrument. Ethereum is much more interesting because, even if it also has its own token, Ether, it can be used as a basis for other tokensFootnote9 or even mutual credit,Footnote10 and has developed a “smart contracts” language (Solidity) to support the execution of algorithms associated with each transaction that can be certified in a number of ways. Although Ethereum has some drawbacks such as currently relying on the energy-hungry PoW consensus protocol, it is migrating to other protocols. In addition to public and “censorship-resistant” blockchains like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Holochain, there are many more private chains mostly developed by banks and central governments, as well as “stable coins” that are backed by baskets of fiat currencies. From the point of view of this paper the interesting aspect is that in the public blockchains the control is decentralized, whereas in the private ones it is centralized. Sardex currently relies on a standard, centralized relational database application running in the cloud (Amazon Web Services, AWS), but as mentioned it is actively developing a new transactional platform and architecture for mutual credit relying on a range of possible blockchain/cloud combinations, as discussed in depth in the deliverables of the INTERLACE EU project, which Sardex coordinated.Footnote11

3.4. Sardex as a different social construction of money

According to Fine and Lapavitsas (Citation2000), money at heart represents relations of trust and power in capitalist markets that facilitate profit-making, and it is thus a foundation of social power and domination. As a consequence, the heart of the capitalist market is focused on the exchange of limited commodities produced by alienated labour and controlled by capitalist elites. A slightly different but largely equivalent account sees capitalism as a power struggle between those who produce money (financial sector), those who produce commodities (productive sector and labour), and the state (regulators). However, in spite of the fact that in capitalism money is treated like a commodity (Amato & Fantacci, Citation2012), whose price is the rate of interest, money and commodities are separate concepts—even when the latter act as backing for the former, as in the case of Sardex. Further, even if we do not prioritize the nature of money as a social relation of credit and debt, viewing it as subject to a power struggle opens up space for social action about the creation of forms of money which are closed off by conceptions of money as a representation of limited commodities controlled by elites. The enactment of such an agenda is best understood through a social constructionist lens.

Fine and Lapavitsas talk about money in a negative way because they, like most people, do not consider the possibility that money can be designed to have different properties that then can have different (better) effects on the society that uses it. The reason seems to be that they make the same assumptions as the neoclassical economists, i.e. they regard money as a neutral veil (Ingham, Citation2004, quoting Schumpeter). From a social constructionist perspective, the money they talk about is an uncritical cultural construction that accumulated over the past 3000 years. Like a sponge, it has absorbed all the worst aspects of human conduct. Graeber (Citation2011) talks about violence, slavery, and war as the roots of money as we know it, for example.

Sardex was designed by emphasizing certain properties of money and de-emphasizing others, in order to improve the trust aspects and damp the asymmetrical power aspects. Sardex was designed and deliberately constructed, it was not received. Thus, Sardex confronts the question of the power held by the financial sector and the elites by distributing the power to create money to the individual SMEs. This different conception of what money is and how it is created then percolates through the circuit and the wider social imaginary. This leads to the question how Sardex incarnates a specific idea of money as social construction.

In particular, money as a social construction is both constructed and structuring, since the financial properties of money have a huge influence on the society it mediates. In line with North, thus, we can argue that Sardex, like most community currencies which originated locally and on a small scale, can be regarded as a micropolitical technology (North, Citation2007, p. 33). We can go a step further. Because no political institutions or election-based representative processes were employed in its creation, and because it unleashes socio-political and economic effects in ways other than conventional political mobilization or activism, Sardex also qualifies as an alter-political intervention in the sense we have defined. The alter-political perspective encompasses the full spectrum of political action, from North’s (mainly) bottom-up (micro)political mobilization and activism to Feenberg’s (mainly) top-down politics of technology.

Changing forms of money such as Sardex lead to modifications in economic relations. Sardex is a different form of money in the sense that it has different structural features. It is not different simply because it is only electronic. It is different because it is not convertible, all balances are at zero interest, and it can only be spent locally with a closed group of other parties. The notable and critical changes in economic relations are that it cuts out the banks, it stimulates spending in the local economy, it does not penalize debt positions with debilitating interest payments, it cannot be used to speculate with, and Sardex invoices are usually paid immediately. Tax on Sardex transactions is tracked and paid in Euros. It is a poor financial investment vehicle but an excellent medium of exchange in support of trade in the real economy.

Sardex does not eradicate the profit motive and mechanisms. However, when the business model does not involve financial market dynamics, the profit motive is easier to keep in check. Sardex is able to do this by isolating the circuit from financial speculation, as discussed, and by strengthening the social dimension. Sardex members are aware of their status as members of a community. They are aware and conscious of the great level of trust underpinning Sardex transactions (Littera et al., Citation2017; Motta, Dini, & Sartori, Citation2017; Sartori & Dini, Citation2016). So, although profit-seeking remains, it is not amplified by the pressure of the financial economy and operates within a set of social norms that are partly a consequence of the local scale of the economy and partly are actively promoted by Sardex S.p.A.

3.5. Breaking with the neoliberal economy? sardex as “impure” alter-politics

The founders’ alter-political project to distribute money-creation power to circuit members itself amounts to a radical democratization step. These radical aspects of the system, however, were balanced from the very beginning by the realization that Sardex needed to enable business growth and maintain a constructive dialogue with the Euro economy, if it truly wanted to help the Sardinian stakeholders. Thus, for example, since Sardinia is even more polarized politically between Left and Right than the Italian mainland, they felt it was better to set up a for-profit company rather than a coop, since the latter was likely to be perceived as a party-political project aligned with the Left. A few years later, they also had to raise a first round of 150k Euro of venture capital (VC) funding in order to buy new servers and pay their staff. More recently, in 2016 they closed another round, this time of 3m Euro and with six more investors, and changed the legal personality from s.r.l. (Ltd.) to S.p.A. (joint-stock). Although the relationship with the investors has not always been easy, in a less ideologically rigid and more exploratory approach to community economies such investments may have a place. This is echoed also by Amato and Fantacci (Citation2012) who point out that, in contrast to securitization, the social relationship between VC investors and entrepreneurs endures until the VC’s exit.

Thus, Sardex could be considered as an “alternative currency”, where this term refers specifically to the alter-political interpretation of the term as defined above. In other words, the Sardex credits are a currency that is both politically alternative and economically complementary to the Euro. But if it is also complementary to the neoliberal economy of our times, how alternative is it, in effect? And how could any social innovation that has an economic impact in contemporary (neoliberal) economies contest the neoliberal hegemony?

The logic of neoliberal capitalism applies free-market ideology equally to real economy markets and to financial markets. Ultimately, it does so because of power relations and elite interests which exploit also the prevailing uncritical acceptance of the culturally inherited reification of money in terms of a precious commodity. Since, as a consequence, (neoliberal) capitalism perceives any regulatory distinction between rentier accumulation and investment in entrepreneurship as undue meddling of the state into market dynamics, it protects the freedom to operate in the financial markets to the extent such markets will bear, leading to unsurprising corrections in the form of financial crises. This freedom, in fact, opens the door to various forms of securitization and, as a side-effect, to the financialization of the real economy. The scale and power of this financialization process is much greater than the profit motive in the real economy because it is driven by hegemonic social motives (greed, competition, quest for power, fear of death, etc; see Amato & Fantacci, Citation2012) and it is not effectively constrained by material, physical, socio-political and labour limits.

Regarding social financial innovation in this context, the case of Grameen finance highlights that good intentions appear to be insufficient, which makes the success of the Sardex case all the more remarkable. Therefore, the Sardex experience and the theoretical work around it, including this paper, suggest that the blind spot of neoliberal capitalism is precisely the supposed neutrality of the medium of exchange. In other words, to break the logic of neoliberal capitalism it appears to be necessary to: (1) recognize that money is not neutral; and (2) redesign the medium of exchange along the lines discussed in this paper. This is what Sardex has done at the level of the circuit. Since it involves the creation of money (Sardex credits) in the issuance of (mutual) loans, the management of debt, and payments, the Sardex system qualifies as a form of finance but, we would argue, a very different form of finance to the one engendered by neoliberal capitalism. More precisely, Sardex enables the creation of trust-based working capital and, as such, this term should replace “financial capital”. To break the logic of neoliberal capitalism it is necessary to isolate the financial economy from the rest of the economy. To achieve, however, a constructive interaction with community-based, social and alternative economies that go beyond the neoliberal capitalist mould, more work is needed.

As Bollier and Conaty (Citation2015, p. 2) have argued, below the radar of mainstream economics and common sense

there is a huge diversity of successful experiments, historical models that have worked at scale, and policy innovations that point the way toward a post-capitalist vision of finance and democratic funding. These include co-operative and community share issues, mutual credit systems, venture capital for community development … social banks, mutual guarantee societies, interest-free banking and co-operative money systems. There are also some remarkable innovations in digital currencies … and models of ‘open co-operativism’ that blend open digital platforms with co-operative governance. The seeds of a new financial system may also be found among new organizational forms such as multi-stakeholder co-ops, ‘open value networks’ such as Sensorica and Enspiral, and networks of ethical entrepreneurs who are conscientiously combining social purpose with market activity.

All of these developments suggest that it is indeed possible to co-create new forms of economic and financial democracy—instances of a more robust “everyday democracy”—and that, therefore, Sardex is not alone in supporting community-based economies. However, a good synergy could be developed between Sardex and the initiatives mentioned above, in the sense that without (something like) Sardex most of the examples of community or commons-based economic innovation, such as those described by Gibson-Graham (Citation2006), are condemned to a difficult struggle for survival. Needless to say, Sardex by itself does not offer and cannot afford to offer the full breadth of possible non-profit and social entrepreneurship initiatives. Rather, the Sardex economy provides an environment where the value of the offer is measured only by its price, as in a normal market, when the buyer has a positive credit balance. However, when the buyer does not have enough credits for what he or she wants to buy, the transaction involves the creation of credits used for that purchase and therefore implies also a valuation of what the buyer can produce for the circuit. In addition, the fact that the buyer is going into debt in order to make the purchase is an additional implicit endorsement for whatever is being sold. The Sardex interactions, therefore, transcend mere market transactions and, on average, can be regarded as sustained by a mixture of standard market demand and personally underwritten endorsements that carry significant responsibility for the endorser. In other words, Sardex transactions are not atomistic, they come with social strings attached. This mutualization of individual agent risk—with consequent strengthening of the trust bonds—is possible because the systemic risk-assessment decision is taken upstream, when that buyer’s credit limit is set by Sardex S.p.A.

We can see, hence, how Sardex’s financial architecture, which is rooted in social ties à la Granovetter (Citation1985), can enable valuation and legitimization of “market” offers that depend on the discretion of the individual members rather than of banks. This, we argue, leaves more room for value systems other than the neoclassical or neoliberal to find productive expression. It is in this sense that, from a theoretical perspective, it may be possible to justify the seemingly greater buoyancy of community economies within the Sardex circuit (as will be shown in greater detail in a future publication). Generally speaking, it is easier to spend Sardex credits than Euros because it is easier to create them and to repay them. It follows that a wider range of products and services will necessarily be supported by the Sardex economic circuit. This same effect, in fact, was observed since the earliest experiments with LETS systems, which are well-known for lowering the barrier to employment (Croall, Citation1997). Time banks exhibit a similar effect. Not surprisingly, many of these “new” jobs involve more personal social ties than the “impersonal” neoclassical market. As already argued, Sardex (and WIR) have made the business infrastructure of this enlarged conception of economy more robust than in the smaller systems like LETS, with consequent greater sustainability also for the non-profit sector and social economies. The question of how alternative modes of financing, and Sardex more specifically, can contribute to meeting basic social needs in socially fair and ecologically responsible ways under the conditions of the current unsustainable capitalist economic model, then, becomes one of business model innovation and social creativity within the more community-friendly Sardex economy.

4. Some hard governance questions and relevant economic data

The Sardex circuit so far has been described in rather positive terms. Does it have any weak points? Is it experiencing any challenges? What about rule enforcement, fraud, free-riding, and attempts to game the system? In this section we briefly address these points and provide some quantitative data of historical circuit performance

Since one of the long-term objectives of the Sardex initiative is eventually to hand over (part of) the ownership and governance of the circuit to the circuit members, the slow and challenging task of “educating” the members on some of the technical, economic, and financial aspects of circuit operation needs to start as soon as possible; in this aspect, the Sardex S.p.A. is a bit behind schedule already. The most difficult part of this process is to build consensus around the importance of individual responsibility as part of the shared responsibility for the well-being of the circuit as a common-pool resource (more on the commons in a future paper). Whereas the individual responsibility of following the rules of the circuit and of the Italian legal system within which it is embedded are both clear in most users’ minds, the default starting point in the Italian culture is to use responsibility as a coercive lever rather than as motivating empowerment for good behaviour. Changing the perception of responsibility from top-down coercion to bottom-up empowerment will take a few more years at least.

Be that as it may, since the circuit so far is only an informal association without its own legal personality, the cornerstone of circuit governance remains Italian contract law: each member has a contract with Sardex S.p.A., renewable yearly, that is based on the provision of a service, the circuit itself and its various functions in support of trade. Each member pays a graded annual membership fee, in Euros, that varies from about 300 Euros for non-profits to 3000 Euros and above for large companies, based on their size and transaction volume. The development of a governance framework for Sardex, therefore, needs to start from this contract and build an ever-increasing awareness of the circuit as an institution built bottom-up by its members and increasingly “owned” by them, both in the figurative and literal meanings of the term. Although mutual credit economics is not a science, yet, a general rule of positive behaviour is to manage one’s account balance by selling and buying in such a way that the balance oscillates between its maximum and minimum possible values as many times as possible each year, thereby maximizing the individual and circuit-wide volume of trade and the circulation of the currency. Approximately half of the users follow this rule, whether knowingly or not, whereas the other half works at sub-optimal levels.

There are two typical problems in mutual credit circuits: free-riding, where some members accumulate a large negative balance and disappear or exit the circuit, and hoarding, where members accumulate a large positive balance and sit on it. Neither case, however, is so simple: many of the chronically negative balances are not malicious free-riders but are simply companies that have gone bankrupt, whose owner has died, etc. Some of the large positive balances are importers of high-demand goods like paper: they would like to spend their credits, but they have to buy the paper in Euros from outside Sardinia; if they sell paper for credits, they quickly accumulate a large positive balance and have a genuine difficulty spending it. So a light-touch “regulatory” approach is preferable.

Currently it is difficult and expensive to enforce circuit-rules compliance, but in a subset of the approximately 10% of the cases where a negative balance cannot be recovered a credit recovery company is being employed as a last resort. The proportion of users whose balance is chronically positive is approximately 30%. Some of this cannot be helped in the short term (although in the new model it will be possible to help them in various ways we do not have space to discuss here), but for the non-importers better education, better incentives, and eventually perhaps some demurrageFootnote12 could help matters. It is difficult to perform these functions manually, but in the new architecture many of these “tuning knobs” will be handled automatically by appropriate blockchain protocols and smart contracts.Footnote13 Regarding tax compliance, this is not a responsibility of the circuit manager: each member is individually responsible to the Italian State. Since the circuit manager needs to provide records of transactions if and when it is requested to by the tax authority, this knowledge acts like a Panopticon such that tax compliance tends to be very high among the members. All tax is paid in Euros.

Finally, there are occasionally some attempts at gaming the system, such as trying to sell products for a higher Sardex credits price than their Euro price, but this is relatively rare and it is usually reported to the circuit manager. In other words, social norms also play an important part. Other forms of gaming, such as currency exchange speculation, are not possible due to non-convertibility.

At a systemic level, perhaps the most important source of stability of the circuit arises from the fact that, on average, the credit line given to a user is about 2% of its turnover, whereas the volume of credits that user is contractually committed to accepting, in one year, is approximately 10% of their turnover. Given that this “spare capacity” of goods they would not have sold were it not for the circuitFootnote14 constitutes the backing of any credits they may create by going negative, in Sardex the ratio of backing to debt is very conservative at about 5/1, which is the opposite of “leverage” in a speculation bubble and enables the circuit to withstand relatively high levels of free-riding and bankruptcies.

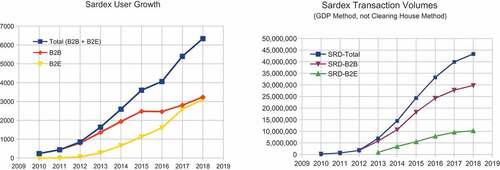

Figure shows the (net) cumulative growth of the users (left) and of the transaction volume (right) of the Sardex circuit from the beginning to the end of 2018, for the B2B and B2E users. There are approximately 100,000 VAT numbers in Sardinia, so the circuit membership amounts to approximately 3–4% of Sardinian companies, by number. The average monetary mass during 2018 was about 9m. In a mutual credit circuit the monetary mass is defined as the sum of all the positive balances, which by definition equals the sum of all the negative balances in absolute value. As can be seen from Figure , the total transaction volume for 2018 was 43m. Thus, the velocity of circulation is 43/9 = 4.8, approximately, and represents the average number of times a Sardex credit changed hands in one year. For comparison, the velocity of circulation of the Euro is close to 1, whereas for the US Dollar it is about 1.5.Footnote15

To get a sense of how the Sardex transaction volume relates to GDP, Sardinian GDP is about 30b Euros. Half of that is by non-Sardinian firms (oil refinery, etc), and 7b is the public sector contribution, which leaves 8b. Therefore, in 2018 the Sardex transaction volume was about 43m/8b = 0.5% of private-sector Sardinian GDP.

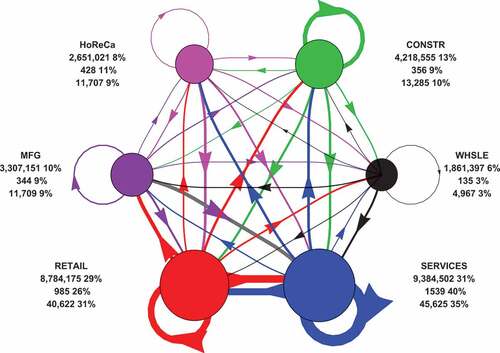

Finally, Figure shows the flow of credits between different business sectors during 2017: Construction, Wholesale, Services, Retail, Manufacturing, and Hospitality-Restaurant-Catering. For each category, the figure shows also the volume transacted and the percent of the total volume, the number of SMEs in that sector with percent of total, and the number of transactions and percent of total. It is clear that in the Sardex circuit the strongest sectors are Retail and Services. Hospitality is not as strong in spite of the importance of the Tourism sector because most of the tourists are from outside Sardinia. The Wholesale sector is composed mainly by importers, so their trade volume is severely constrained as explained above.

5. Sardex and the micropolitics of complementary currencies

To take a deeper dive into the transformative alter-political potential of the Sardex economy, in this final section we elaborate on the ways in which the Sardex economy could bolster broader transformations towards democratic social economies.

Sardex’s political-economic strategy can open up new forms of liberatory potential for common people (North, Citation2007, p. 40) to the extent that users become aware of the greater power the system affords them. This is initially in the form of money-creation power, but could be linked to participatory governance and greater democratic consciousness through a growing recognition within the circuit that it represents their economy. Such a process is slower and more difficult in countries with a weaker democratic participatory tradition or regions whose people have been disenfranchized for centuries like Sardinia.Footnote16

The broader question is whether, and how, Sardex could trigger democratic transformative dynamics in local economies and societies in general, as an approach that could be adopted outside of Sardinia. This may require the users’ consciousness to be “cultivated” along the way, which in turn calls for a sophisticated strategy since at no point should the communication be paternalistic. This gradual discovery underpins an interesting and potentially powerful bottom-up, emergent process, which is pragmatic, dynamic, and emergent. It does not impose big political plans/objectives from the top or from “vanguards”. Sardex is still struggling with this process partly because the Italian communication paradigm and “common sense” have been greatly influenced by the neoliberal market and marketing perspective, and partly because the presence of VC investors has recently reinforced the business identity of the company at the expense of the community identity of the circuit.

Moreover, to induce macro-change, Sardex should scale up. Such scaling up is most likely for alternative currencies as economic actors. Sardex shows that an effective and powerful strategy is to act on the medium of exchange and let social constructionist processes run their course, as argued above. But to craft a space in which such processes can take place requires an institutional structure. Such a structure does not have to be a for-profit, capitalist company; it could be a non-profit coop, or a public-private initiative, etc. However, in the context of the current neoliberal economy and nation-states, a company structure that straddles the capitalist economy and the non-profit sector appears to have a better chance of success for macro-economic change, as illustrated by Sardex itself. A market/non-profit combined approach such as Sardex’s provides the weakest members of the real economy, the SMEs, with greater market power, but consciously sustains also local community activity and non-profits. It disintermediates the banks and in general strengthens the local real economy at the expense of the financial economy and creates a friendly environment for the non-profit and cultural sector, nurturing a limited (alter-)political awareness. Based on the Sardex experience, these appear to be the conditions in which social movements have the potential to undertake more effective interventions.

The bigger question of whether and how Sardex as a system, methodology or protocol could help to intervene in conventional financial systems globally, curb the power of the dominant rentier system, and incentivize the growth of community-based, social and solidarity economies may be answerable through a composite company structure combined with an open architecture for a business-neutral (even if alter-politically non-neutral), open, public, and permissioned blockchain infrastructure (Dini et al., Citation2019; Littera, Dini, & Dini, Citation2019). This approach could help to reduce the power of financial capital in creating money and transfer parts of this power to the social economy, resulting in communities and broader societies which regain greater democratic control over the creation, the distribution and the regulation of money, reclaiming thus the financial system for social and real-economy purposes.

The collective governance features of a future, scalable Sardex system could help to develop effective and wide-ranging systems of money, funding and finance as commons. In fact, since the long-term view of the Sardex proprietary structure envisages part-ownership of each circuit by its members, whether or not each circuit will serve a public function governed by the community of its users for the common benefit and a commons-based mode of production will become a matter of how a given circuit chooses to govern itself and experiment, or not, in this direction. In the present context of the Sardex S.p.A. company, the vision of it supporting the growth of local communities in a decentralized way so that they adopt and part-own the Sardex mutual credit infrastructure (Dini et al., Citation2019) relies on a critical balance between social principles and market funding, without which the global (open, public, “permissioned”) platform of Sardex (Littera et al., Citation2019) could not be completed. The aim is to “buy out” capital investors in the future and reclaim full community ownership of the Sardex circuit, while in other local contexts public funding for infrastructure development may be available and apposite.

Hence, rather than providing a specific model for creating local systems of money creation, distribution and exchange, which are collectively self-managed and work in favour of co-operative economies for the common benefit, Sardex merely provides a real-economy, market-focused but protected environment that can enable the construction of such communities and economies in a manner that is more financially compatible with them. Keeping the infrastructure as neutral as possible will leave more room for a gradual decentralization and self-determination of the individual communities at more abstract levels of enterprise model and governance framework definition.

As a result of this open, “pluggable” approach, it should become easier for Sardex as a model to enable the emergence of evolving ecosystems of the commons such as free software and open design communities or local farming co-operatives, rather than financing them directly (Sardex is not a bank, or an investment fund). Whether or not these circuits are able to reduce the risk of credit and lending for those who want to finance community projects will be down to the socio-economic competence and creativity of the subjects involved. On the other hand, the management of free-riding and circuit rules compliance will be most probably done at the level of the protocols of the infrastructure, which can easily track the maturity of a given debt position and impose sanctions if the debt is not recovered within the contractual 12 months. The type and severity of sanctions would most probably be a matter for the global governance of the infrastructure to decide, rather than for a specific circuit. However, the objective remains to make it a shared decision since the legal entities managing the circuits will be part-owners of the global (non-profit) infrastructure.

The general approach will remain to mutualize the risks and the benefits, like the Sardex circuit currently does and, also, to mutualize the responsibility for debt creation between debtors and creditors.Footnote17 Finally, the ecological dimension is very compatible with mutual credit because (renewable) energy is always in high demand and can, therefore, be used both as backing by individual users and as a way for users who have legitimate difficulties spending their high positive balances (e.g. importers) to spend their excess credits. In brief, rather than cultivating the values and practices of the commons directly, in order to generate communities sharing resources, co-managing and co-governing them, with openness, pluralism, creativity, justice and solidarity, Sardex can generate an enabling infrastructure and application layer and will then lead by example.

6. Conclusion

What is the added value of talking about “alter-politics”, in general, and the “alter-politics of Sardex”, more specifically? Contemporary societies are faced with daunting political challenges arising from dramatic inequalities, economic crises, climate change, massive disaffection with established liberal democracies, growing migration flows, and rising xenophobia. Political systems and ruling elites are largely unresponsive to social needs and have proven unable so far to face up to these challenges for the common good. Collective mobilizations have achieved partial but occasionally important victories; yet, they have not effectively tackled the broader crises, either. Hence the need to experiment also with new and different forms of political intervention, which may not provide the solution but may well form part of one.

An expanded conception of politics as deliberate and diverse action on social relations and an attention to non-mainstream modes of political action thus understood help to grasp other ways of doing politics, to bring them to the fore and to consider their promise and potential. Alter-political activity is alternative to both hegemonic politics and to typical modes of mobilization and contestation. It can unfold in everyday life and local communities through diverse civic initiatives. It can be pragmatic, effective and able to fuel wider transformative dynamics. By highlighting, more specifically, alter-political processes which foster collective self-governance, civic empowerment, fairness, sharing, collaboration, solidarity, equality, sustainability (the politics of “the commons”, in a word), we can show that they are possible and able to proliferate and expand, ushering in potentially deeper historical shifts.

We broached the Sardex currency and circuit in such terms in order to illustrate a significant and effective instance of alter-politics in our times and also to indicate, more specifically, community financial innovations which could be taken up and re-deployed to democratize or “commonify” local economies. Sardex did not seek to explicitly promote a particular political ideology or project, focusing instead on pragmatic economic concerns in a certain location. However, without too much fanfare and political talk, it built on this level a fairer monetary and financial system which altered the practices of money creation and distribution by creating its own currency based on zero-interest mutual credit. Sardex has nurtured thereby social relations, reciprocity, mutualism, responsibility, and trust among its members in non-intrusive ways, which were designed into the very infrastructure of the circuit but were activated and animated by social interaction in the community itself. The key alter-political decision of Sardex to establish mutual credit as the monetary and financial model challenges the vastly unequal financial power of banks and states, which lies at the core of the neoliberal regime, and democratizes the power to create money by distributing it to the circuit members (SMEs), while by-passing the banks and impeding financial speculation. Moreover, Sardex counteracts the fetishization of money by disclosing daily its roots in social construction within a controlled environment of mutual responsibility and solidarity. It shows thus how a local community can change its fate and directly control one of the most elusive, decisive and unequal social powers of our epoch—finance—while strengthening social bonds and local economic life. Furthermore, Sardex stages an open, “pluggable”, non-profit infrastructure model that can be taken up by others to sustain financially new, open co-operatives and social economies for the common benefit, and that allows for decentralization, participatory governance and the self-determination of financial systems by particular communities.

The alter-politics of Sardex is pragmatic, “in-between”, impure, and enabling further socio-economic transformations in directions which may go beyond the actual course of Sardex itself. Its distinct alter-political character lies in the fact that Sardex brings about crucial socio-economic effects—enhancing trust and solidarity, empowering local economies and communities—in low-key and inclusionary ways which differ from those of representative politics, conventional political mobilization and ideological catechism. This is, then, a mode of transformative politics that is worth considering and, perhaps, emulating, enhancing and expanding in the interest of the common goods.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 724692). The authors are grateful to Giuseppe Littera for the many discussions and insightful observations he shared with us on mutual credit in general and Sardex in particular.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paolo Dini

Paolo Dini Associate Professorial Research Fellow, Department of Media and Communications, LSE; Senior Research Fellow, School of Computer Science, University of Hertfordshire; and R&D Consultant for Sardex S.p.A. Dr Dini has a PhD in Aerospace Engineering from Penn State University. He joined LSE in 2003 and currently divides his time between LSE, UH, and Sardex, for which he consults on all aspects of the circuit.

Alexandros Kioupkiolis