Abstract

Infrastructure has historically been absent in informal settlements in Oceania. Oceanic governments have deliberately withheld infrastructure to these settlements denying them essential resources, human rights, and ways of life. Current reforms in urban policy seek to rectify this record by promising more inclusive infrastructures. In this article, I investigate the effect a promised electricity infrastructure had in an informal settlement in Suva, Fiji. Prior to development, residents created their own infrastructures that equitably shared electricity in spaces of electricity sharing. The initiation of infrastructural works destroyed this local infrastructure embedded in local social relations. While residents waited for this promised infrastructure to be constructed, they erected informal power grids that mimicked the exclusive and commoditised provision of electricity of the planned infrastructure. I argue that the promise of infrastructural development in informal settlements in Oceania is reshaping previously inclusive forms infrastructural citizenship in favour of more exclusive infrastructural relationships.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Susan Leigh Star, labelled infrastructure as a series of uninspiring and background objects. This greyness of infrastructure however conceals an abundance of vibrant social activity and meaning that lies just below the surface. For what purposes we construct infrastructure, who is permitted to use it, and what other daily activities operate alongside its use reveal the most fundamental ways society organises itself. Infrastructural systems can be moulded in specific ways to cater to the needs of specific groups of people and their ways of being while at the same time ignoring the desires of others. Those whose basic needs are privileged in infrastructural construction are legitimised as recognized citizens in society, while those who are ignored are delegitimised. The globe is in a moment in infrastructural development; understanding how ideas of citizenship change alongside infrastructural change is the basis of this paper in the Oceanic context.

1. Introduction

Social scientists are dedicating an increasing amount of attention to infrastructure and the implications that infrastructural developments have on social life. This focus has encompassed a broad array of infrastructural projects including roads (Harvey & Knox, Citation2012), electricity (Mains, Citation2012), water (Anand, Citation2012; Von Schnitzler, Citation2008), waste collection (Zapata Campos & Zapata, Citation2013), sanitation systems (Lawhon, Nilsson, Silver, Ernstson, & Lwasa, Citation2018), and multinational company compounds and plants (Appel, Citation2012). Literature in this “infrastructural turn” highlights that infrastructural developments often promise expanded entrepreneurial opportunities and lifestyle improvements, but in reality distribute use and benefits to certain populations while excluding others (Anand, Citation2012). From this point of identification, analysis often centres on how marginalised groups of people reclaim access to infrastructure (Anand, Citation2012). Anthropologists are drawn to these localised practices of infrastructural reclamation as they provide examples where societal relations between excluded residents, governments, and material structures are actively contested and reshaped. The outcomes of these relations surrounding infrastructure define the distribution of resources, rights, and forms of ontology that are inherent in citizenship (Jensen & Morita, Citation2015; Koster & Nuijten, Citation2016; Ranganathan, Citation2014; Rodgers & O’neill, Citation2012). In this article I analyse how ideas of Oceanic citizenship changed during a prolonged residential development project in an informal settlement in Suva Fiji. I argue that the development project promised a modern infrastructure that reformed the rules and norms of infrastructural access. This promised infrastructure started to redefine everyday notions of urban Fijian citizenship before it was even constructed.

2. Infrastructural citizenship in informal settlements

Informal settlements are consistently a popular domain for investigating conceptions of citizenship due to the various exclusions residents of these communities experience. First and foremost, informal settlements are classified as “informal” by state institutions, placing their residents legally outside of the bounds of formal urban citizenship (Roy, Citation2003). Informal settlements, however, are consistently found to add to urban economies through the livelihood activities they sustain as well as provide essential social and cultural functions to other city residents (Jones, Citation2016; Koster & Nuijten, Citation2016). Despite this inherent economic and social value of informal settlements, there are concerted state and societal efforts to deny resources and rights to their residents, as well as media and political campaigns to disparage their ways of life (Connell, Citation2003). The most common way states marginalise residents of informal settlements is to not provide basic infrastructural services (Davy & Pellissery, Citation2013). This infrastructural denial often challenges residents’ ability to provide their valuable functions to urban life. Infrastructural denial is a visible and tangible extension of their legal exclusion delegitimises their valuable ways of life as ones not befitting of a citizen (Davy & Pellissery, Citation2013).

To challenge this lack of formal infrastructural provision, residents of informal settlements are forced to construct their own infrastructures either from scratch or extended from nearby formal infrastructures. Resident organised construction of infrastructure exemplifies a reclamation of citizenship by informal settlement residents (Anand, Citation2012). This resident struggle for citizenship through the domain of infrastructure is equally highly visible as its denial. This struggle is made visible by the great efforts required to obtain illegal access to infrastructural services in the absence of formal provision. When the management of technical, infrastructural systems becomes a daily concern that involves demands on time, physical labour, and ingenuity, it is no longer an invisible or background structure (Amin, Citation2014; Graham, Citation2010; Larkin, Citation2013; Simone & Abouhani, Citation2005). Infrastructures are at the centre of activity continuously managed by residents to keep up with technical innovations or socio-political contexts that seek to bar them from access. They are continuously cobbled together with everyday materials in combinations that may change from week to week to adapt to ever-changing contexts (Amin, Citation2014). The struggle for citizenship through the domain of infrastructure becomes even more visible when its local construction and management is directly and forcefully contested by state actors. When resident constructed infrastructures are destroyed, infrastructure becomes a highly politicised. Residents and state actors sometimes engage in violent and materially destructive action that can be dramatized in the public domain (Rodgers & O’neill, Citation2012; Von Schnitzler, Citation2008).

The struggle for infrastructural citizenship in informal settlements does not solely exist in a context of infrastructural denial and reclamation. Processes of urbanisation and urban sprawl are continually reclassifying peripheral or marginal informal settlements across the globe as places of potential urban reclamation (Bryant‐Tokalau, Citation2014). Informal settlements that were previously ignored are increasingly incorporated into cities. The primary method of incorporating these settlements into cities is by upgrading their infrastructures and introducing state-mandated ways of managing them. The expansion of infrastructure into settlements promises residents connection to utilities such as electricity, water, and garbage collection. By extension, this expansion of infrastructure promises an inclusive form of citizenship and access to modernity (Jones, Citation2017; Koster & Nuijten, Citation2012; Zapata Campos & Zapata, Citation2013). In many cities, there is a competitive and political frontier for infrastructural upgrade or formalisation (Anand, Citation2012; Ranganathan, Citation2014).

Contrary to the expectations of obtaining inclusive infrastructural citizenship through settlement upgrade or formalisation, this goal is rarely achieved or even genuinely attempted by state institutions and developers. New methods of infrastructural exclusion are usually attached to these upgrades. Residents are often forced to pay unaffordable prices for infrastructural service that they previously obtained for free. Residents cannot bypass these new infrastructures as they did previously because new technical payment meters and other forms of regulation are typically installed (Von Schnitzler, Citation2008; Zapata Campos & Zapata, Citation2013). In addition to these new methods of infrastructural exclusion, the everyday lively activities that residents take in accessing and maintaining their tenuous access to infrastructure are taken away from them as infrastructural organisation and construction moves to a solely state-regulated domain. The shift of agency to organise and construct their own infrastructure deflates residents’ ability to reclaim infrastructural citizenship (Amin, Citation2014; Lawhon et al., Citation2018). The promise of inclusive infrastructure accompanying urbanisation and settlement upgrade projects intentionally and insidiously challenges localised manifestations of citizenship.

The potential for infrastructural upgrades to further restrict access to citizenship sometimes causes residents to actively resist infrastructural upgrades. In some cases, residents recognise they are not necessarily the beneficiaries of the project. Residents often see that infrastructural upgrades are a requirement of the state to fulfil urban reclamation projects destined for other urban residents that will move into the area (Roy, Citation2005). More often, most resistance against infrastructural projects is tamped into compromise by state institutions and developers. Residents accept the new realities that a new formal infrastructure entails; especially when other benefits are attached such as secure land tenure are offered (Koster & Nuijten, Citation2012). The prospect of modernity attached to infrastructural upgrades further allures residents into submission (Koster & Nuijten, Citation2012). After state actors achieve this submission, developers begin constructing and implementing infrastructural upgrades. These new infrastructures are inclusive in the sense that residents are given the opportunity to use them. However, their social and cultural inappropriateness often presents real challenges for residents to effectively use or access them. Despite residents’ initial compliance or excitement, residents either a) move out of informal settlements to others that have not been upgraded, or b) try and subvert such infrastructures rendering them useless (Koster & Nuijten, Citation2012). Such resident action to avoid infrastructures that are not designed for appropriate local use further demonstrates infrastructural citizenry exclusion.

In this paper, I investigate a third response. I investigate how residents become co-producers of infrastructure in a manner that interacts with the types of inclusion that such upgrades propagate. Commonly overlooked, there is often a dialogue that residents have with formal institutions and developers that allow a co-production of social arrangements around materiality (Koster & Nuijten, Citation2016; McFarlane, Citation2011; Vigh, Citation2009). Rather than experiencing exclusions imposed by a formal infrastructure, residents are compelled to adapt to its new realities. Residents redefine their social relations to work within a new materiality and rationality imposed upon them. This redefining of social relations is no less creative especially when the new infrastructure can only be imagined as infrastructural development progresses slowly over a prolonged period (Gupta, Citation2018). Residents mimic or predict the rationality behind the future infrastructure that is promised to them. This leads to unique infrastructural arrangements as this infrastructural prediction can be misinterpreted or partial. Residents, in a field influenced by state agents and commercial developers, become active yet restricted co-agents in redefining everyday ontologies according to formal rationalities. In this process, localised conceptions of citizenship change based on these co-relations between residents and state actors while material infrastructures are torn down and reconstructed. This co-construction of citizenship in the infrastructural domain is occurring in the informal settlements of Oceania and in particular, Suva Fiji where I conducted ethnographic fieldwork.

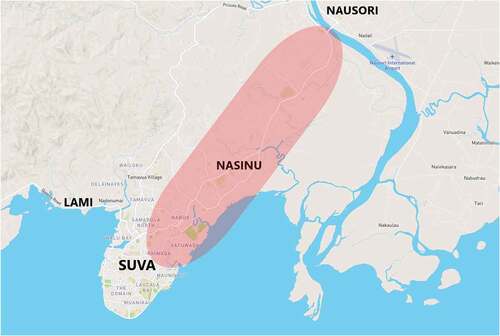

3. Infrastructural citizenship of urban oceania

Informal settlements in Oceania are increasingly becoming the targets of infrastructural upgrade programs due to processes of rapid urbanisation affecting the region. The Solomon Islands has an urban population growth rate of 4.4%, twice the rate of national population growth (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015). Vanuatu and Kiribati face similar rapid urban growth that outpaces national population growth. Papua New Guinea is also experiencing rapid urban population growth, with their urban population set to double by 2030 to 2 million (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015). Fiji sits squarely in the rapid urban growth trend. According to the latest Fijian census held in 2007, Fiji has a total population of 837,271 people. 51% of this population (427,008) live in urban areas. Suva is the largest of these cities and is the nation’s capital, with 57% of this urban population (244,000). This population is spread across a sprawling area known as the Greater Suva Urban Area (GSUA) (Fiji: Greater Suva Urban Profile, Citation2012). Suva is urbanising rapidly, with much of the new population originating from rural islands and settling in squatter or informal settlements due to poor urban management policy (Fiji: Greater Suva Urban Profile, 2012). There are approximately 90,000–100,000 people living in squatter or informal settlements with 60% of this population are living in the Suva-Nausori corridor indicated in red in Figure (Thornton, Citation2009). The municipality of Nasinu lies in the middle of this corridor.

The rapid rate of urban population growth is forcing Oceanic governments to rethink their urban policies regarding informal settlements. Oceanic governments have historically considered the growing number of squatter and informal settlements a scourge on the urban landscape in the post-colonial era (Connell, Citation2003). There has been a persistent attempt to alienate residents of settlements from the urban landscape based on the supposed challenge they pose to the notion of urban order. Such an attitude reflects the persistent accepted ideas of what urban citizenship should look like in the legacy of the colonial city. There has been a perpetual campaign of moral regulation, social exclusion, and moral panic dividing those living in settlements from supposed “good citizens” that reflect antiquated colonial definitions of urban citizenship (Barr, Citation2007; Connell, Citation2003).

This exclusionary regulation of the urban environment and the subsequent rejection of the progressive conception of the Oceanic city emancipated from colonial rule is more insidiously manifest in the lack of infrastructure provision. Dornan (Citation2014) states that Fiji has “medium levels of access” in the region at an 89% electricity access rate. Other Oceanic nations such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands respectively have “low levels of access” at 10% and 14% electricity access rates. Despite this comparatively high level of electricity access in the region, the Fijian government in line with other Oceanic governments has historically not provided infrastructural services such as power, water, and garbage collection to informal settlements in Fiji (Connell, Citation2003; Walsh, Citation1978). Rather, informal settlers have been required to purchase infrastructural materials such as PVC pipe, electricity wire, and pine electricity poles, that they then need to install and connect to the formal water and electricity infrastructures (Asian Devlopment Bank, Citation2013). The burden of cost, time, and expertise this places on informal settlement residents has caused many residents to forego private access to these services in favour of relying on the very select few residents in these settlement who have created such connections (Asian Devlopment Bank, Citation2013). Dornan (Citation2014) attributes the differences in electricity access seen across the region on differences in economic prosperity measure in GDP per capita, and not because of meaningful differences in urban policy. Rather Fiji, like other Oceanic governments have delegitimised informal settlement occupation by not facilitating infrastructural connection to formal infrastructure. Infrastructural exclusion has been persistently used across the region as a medium to control and restrict formal urban membership to residents of squatter and informal settlements, and Fiji is no exception (Connell, Citation2003; Walsh, Citation1978).

Urban policy is starting to change in Fiji. In the last decade, there has been an “attitudinal shift” in urban policy by the Fijian government to accommodate urban settlers. This attitudinal shift has been motivated primarily by external pressure from the United Nations (UN), which through the UN Declaration of Human Rights recognises the basic human right of access to housing (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015). Through the production of urban profiles and a push for a “New Urban Agenda”, the United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat) has influenced a receptive Fijian government looking to enhance its human rights record and reputation (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015). This pressure has resulted in constitutional amendments that protect settlers from arbitrary evictions and house demolitions without a court order. Even more notably, there have been efforts to search for solutions to secure tenure for these informal settlers in ways that accommodate their traditional land tenure agreements (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015; Kiddle, McEvoy, Mitchell, Jones, & Mecartney, Citation2017). With a greater recognition of informal settlement residents’ rights to occupation, electricity, water, and road access has started to be formally connected to these settlements in accordance to Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme (PSUP) guidelines overseen by UN-Habitat and the Peoples Community Network (PCN) (Kiddle & Hay, Citation2017). In accordance with the PSUP, settlements are upgraded in-situ which emphasises minimal disruption to settlements during infrastructural upgrade.

Most of these infrastructural upgrades are occurring in informal settlements on native or state land where governmental authorities such as the Fiji Department of Housing, or native authorities such as the Native Land Trust Board (NLTB), have authority. However, 19% of informal settlements are located on land held by freehold landowners where these authorities hold less authority (Kiddle & Hay, Citation2017). These settlements are being targeted for urban development projects to house the increasingly burgeoning population (Bryant‐Tokalau, Citation2014). In consultation with the Fiji Department of Housing, land developers are repossessing a majority of settlement land for residential or commercial development. Meanwhile, developers are transferring smaller portions of settlement land to state ownership where existing residents are then able to acquire formal tenure on smaller plots within their settlement. Solutions such as these provide pathways through which informal settlers can access secure tenure in a context of rapid urbanisation which many residents willingly accept. Infrastructure is also formally provided by state authorities to these relocated residents according to the PSUP guidelines as they acquire formal land tenure in such compromises.

Settlement upgrades guided by the PSUP seem to balance the pressures of urbanisation and the human rights of informal settlement residents. However, in practice unavoidable resident relocations greatly disrupt informal settlement communities (Kiddle & Hay, Citation2017). Formal infrastructures displace socially embedded infrastructures that both provide access to crucial utilities as well as promote collective identities. In the case of developer-state collaborations, not only are social infrastructures displaced, but formal infrastructure construction in resident relocation areas is slow to be implemented due to the magnitude and poor facilitation of resident relocation. This social and infrastructural disruption is highly evident in Veitiri informal settlement in Suva Fiji where I conducted my ethnographic fieldwork.

4. The development of veitiri informal settlement

Veitiri (pseudonym) was founded within the Suva-Nausori corridor in the late 1960s by a collection of groups. The first of these was a family that migrated from a nearby native village that wished to be closer to the coast for fishing activities. The land of Veitiri on which they settled was traditionally owned by their native village. Many other families from this nearby native village followed them to Veitiri. The native village gave permission for a group of Solomon Islanders who were brought over as part of the blackbird trade to also reside on the land. Their kin were originally brought from the Solomon Islands to Fiji to clear the urban area of Suva of bush for urban development. Since the late 1960s, the settlement has progressively accepted more groups of people into the settlement via vakavanua agreement. A vakavanua agreement allows prospective residents to reside on another village’s traditional lands. Wealth items such as whale teeth and kerosene are typically given to traditional land owners in return (Kiddle, Citation2011). Vakavanua agreements have allowed migrants from an array of rural islands such as the Laun Islands, Kadavu, and Lomaviti to reside in Veitiri. However, these migrants from other rural islands in Fiji also have a social connection to the nearby native village through intermarriage. Ties of intermarriage provide the basis from which vakavanua agreements can be broached, justified, and accepted (Jones, Citation2016).

The traditional and socially cohesive relationships between residents are reflected in the layout of the informal settlement. Households in Veitiri are loosely clustered together based on kinship affiliation. A church and sports ground also occupy the centre of the settlement. The settlement is located on large marginal swampy grounds which has not previously been highly valued enough to be touched by urban development. Residents have therefore been able to spread diffusely, causing the settlement to be of relatively low density. There is ample space between houses for large trees to grow that blanket the settlement. There are also additional grounds to grow traditional root crops and raise animals such as pigs. Informal settlements like Veitiri have been classified as “agri-hoods” due to both their agricultural and urban nature (Thornton, Citation2009). They have also been classified as “urban villages” due to their rural village like social and spatial arrangement (Jones, Citation2016).

Despite the presence of traditional land tenure agreements and traditional social and spatial arrangements, the land of Veitiri is not formally owned by the nearby native village. A majority of urban lands were alienated and not returned to native owners in the period of British colonisation (France, Citation1969). In line with this reality, the land of Veitiri has been owned by an Indian residential co-operative since the formation of the informal settlement. For most residents in Veitiri it was unknown that the land was owned by the Indian residential co-operative and not owned by the nearby native village. A few groups in the settlement did know and accept the Indian residential co-operative’s formal ownership and claimed that in the 1990s they paid large sums to the co-operative to secure a spot in any future developments. These promises are refuted by the residential co-operative. It has only been since the beginning of my fieldwork in October 2016 that the Indian residential co-operative has engaged in developing the land. The development occurred during and beyond the conclusion of my fieldwork in December 2017.

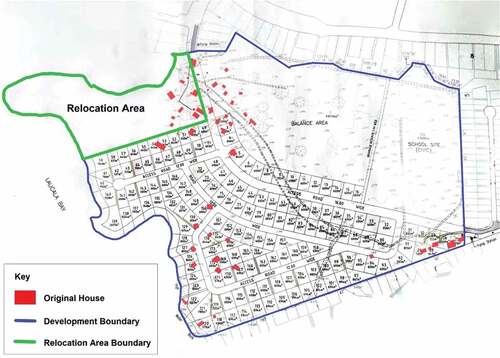

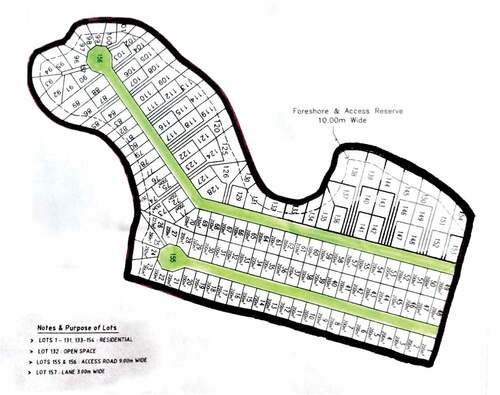

Prior to my arrival in Veitiri, the Indian residential co-operative initially encountered resistance to their plans of development that required current residents to be evicted. Residents of Veitiri did not respond to eviction notices. To reduce resistance and delays to development, a collaborative project was formed with the Fijian government that allowed the residents of Veitiri to remain but relocated them to smaller landholdings within the settlement. This plan allowed the Indian residential co-operative to use most of the settlement’s land for residential development and sale. Most plots for sale in the residential development area measured 600m2 while access roads are between 12–16 meters wide. The relocation area allocated for residents is designated as a specialist zone that reduces planning criteria such as plot sizes and road street widths (Kiddle & Hay, Citation2017). Each plot in the relocation area measured 200 m2 while access roads are 9 meters wide. These plots were arranged in a tight grid-like pattern unlike their original settlement spatial arrangement. Some of the plots were also to be allocated to residents from other settlements whose settlements were being developed by the same company elsewhere in the Suva-Nausori corridor. Plans of the residential development, and the Veitiri resident relocation area are shown in Figure . Overlayed onto Figure is the original spatial layout of the major original household structures of Veitiri, shown in red. Smaller, more recent, or temporary structures are not indicated in this overlay and therefore only represent a portion of the settlement’s structures. A detailed plan of the proposed layout of the settlement relocation area is provided in Figure .

As indicated in Figure , a minority of original settlement households were already in the general area designated to them. Some of these household units were not required to dismantle and reconstruct their houses as they fit perfectly into the allocated plots indicated in Figure . Other household units were in the allocated area, but their houses were in the middle of these invisible boundaries, and they were forced to dismantle their houses and reconstruct them mere meters away. Most household units were not in the allocated area and were forced to dismantle their houses and relocate to an area of the settlement that they previously had little connection with. For most residents of the informal settlement, this social and spatial reorganisation of the settlement was a less than ideal compromise for secure land tenure, especially because they had produced connections to the land and other residents surrounding them.

The relocation of houses, the building of roads, and the erection of boundaries disrupted the infrastructural systems that the residents had long established. The electricity material infrastructure consisting of posts and wires was torn down leaving residents with few options to charge their mobile phones. Most damaging however was how the development destroyed social infrastructures in the settlement which informal residents rally behind to access electricity (Simone & Abouhani, Citation2005). Social infrastructures consist of “phatic relationships” which can be relied upon to “get by” in the urban environment. These communicative channels can be considered as a “public good” held in the collective property of the urban poor (Elyachar, Citation2010). These social infrastructures allow residents to access essential services that they have been marginalised from by the state and therefore form their tenuous link to citizenship (Berenschot & van Klinken, Citation2018). The material and spatial rearrangement of the settlement disrupted these social infrastructures in ways that not only made accessing electricity more difficult, but also in ways that undermined how these relationships were utilised to claim citizenship through the infrastructural domain. Through a redefining of relationships through infrastructure, new and more exclusionary conceptions of citizenship were created.

5. Methodology

I conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Veitiri informal settlement during October 2016—July 2017, and a return trip for two weeks in December 2017. During my fieldwork, I found that informal settlements such as Veitiri are places where formal policy and informal practice interact within an ill-defined field of infrastructural authority (Koster & Nuijten, Citation2016; McFarlane & Rutherford, Citation2008; Waldorff, Citation2016). In Veitiri, the developer and state actors progressively asserted more authority over the settlement as my fieldwork continued, but in ways that were vague, incomplete, and contradictory. Residents had a restrained agency to interpret and act within this loose form of authority; in particular how infrastructure would be built and managed as the development slowly progressed. In this context of loose authority, I considered Veitiri informal settlement to be a field of residential affairs where “local authorities, residents, firms and other social agents compete and co-operate over residential matters” (Postill, Citation2011). I analysed how the presence of developers and state actors influenced how certain rules, norms and moralities embedded in surrounding infrastructure were co-constructed. In particular, I analysed how residential infrastructural arrangements changed through the interplay of actors during the development. Through this interplay, certain moralities expressed through infrastructure were progressively changed through the developer’s and state’s insertion into the field of residential affairs. I argue that their insertion fundamentally reshaped the localised definition of Fijian urban citizenship.

Accessing and recording this interplay between residents, land developers, and Fijian authorities in this field of residential affairs was not without challenges. The development of the settlement fit within a broader political discourse of the position of native itaukei Fijians within the country. Those resisting the development were staunch believers that the alienated urban lands on which they reside belong to them as native itaukei Fijians. This in part, along with other subjects concerning itaukei Fijian prominence within the country, has been the basis of four political coups in 1987(twice), 2000, and 2006 (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). Currently the Fijian government is advocating for a multicultural vision of Fiji, that itaukei Fijians in informal settlements believe undermine their rightful claim over urban lands and position in Fijian society (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). This presented problems in recording the interplay between these entities in this field of residential affairs due to the political sensitivity of information. Most prominently, residents resisting the development feared political surveillance through voice recording devises, including my own. Residents who accepted the development were also cautious of voice recording as they did not want to risk the sharing of personally identifiable information across the settlement despite my assurances of the security of their data. This fear of political surveillance has emerged throughout Fiji in response to laws that restrict freedom of speech in various forms of written and online media (Singh, Citation2017; Tarai, Kant, & Finau et al., Citation2015). In this context of political sensitivity, the Indian residential co-operative was also unwilling to submit to voice recording. While I was unable to gather voice recordings of research participants, this did not prevent me from analysing how Fijian conceptions of citizenship were reshaped through the interplay of these entities in the field of residential affairs, particularly in the infrastructural domain.

To investigate the interactions and outcomes between these entities, I primarily used ethnographic observation and surveys concerning the development and use of infrastructure. I was primarily informed by the work of Star (Citation1999, Citation2002)) who emphasises that observing the mundane materiality of infrastructure, and everyday interactions with this materiality can reveal various social relationships and orderings. Observing how material infrastructure is constructed, how it is accessed, who is permitted (and not permitted) to access it, when it is accessed, what practices operate alongside infrastructures, and how it is systematically organized all indicate how societal relationships are arranged. In the settlement of Veitiri, how residents interacted with the materiality of infrastructure was ever changing based on the development of the settlement by the land developers and the Fijian government. To assess the effect of the developers and the Fijian government on infrastructural development and use I drew upon development plans and PSUP guideline documents, with their outlined objectives, and observed how these plans progressively translated to infrastructural development in the settlement. I then observed and mapped how residents were further moulding infrastructure in response to how these formal frameworks were implemented in the settlement. The way these entities thus co-produced a material infrastructure revealed new forms of relationships and orderings within the settlement. These new relationships and orderings exhibited in material infrastructure fundamentally betrayed earlier inclusive and collective relationships that defined Fijian urban citizenship, in favour of more exclusive infrastructural relationships.

To assess the initial infrastructural system within Veitiri settlement I needed to assess which houses had electricity and how it was distributed. I determined that residents of the 101-household settlement accessed electricity from 7 houses in the settlement that had access to electricity, either via a private household generator or informal connection to the formal power grid. During many household visits, I observed how electricity was accessed at these households while sitting next to their power points. I observed who was charging, what was charged and when they charged. I also gave logbooks to 4 of the 7 households who had access to electricity for a one-week period to quantify this data. I found that these houses and surrounding areas were spaces in which the entire settlement could come to access electricity. Furthermore, the activity of charging in these spaces were bound up in the reciprocal exchange of other goods and favours. Observation and logbook entries at these spaces provided detail on the social infrastructures that operated alongside the material infrastructure, detailing a settlement-wide inclusive and culturally sensitive solution to accessing electricity.

As the development and construction in the settlement progressed, the material and social infrastructures were destroyed by the development. Wire arrangements were dismantled, and spaces of electricity access were destroyed. To replace the prior material and social infrastructure, residents constructed informal power grids made of common extension cables linking certain houses. To analyse how the material infrastructure had changed I started mapping which wires connected who, and who they bypassed. I also recorded the exchange relationships between these connected households as electricity flowed along the cables in one direction, and money in the other. This occurred in ways that fundamentally differed from the relationships represented in the previous spaces of electricity. Lastly, I observed how residents interacted with settlement development plans and the changing material realities that surrounded them that required them to adjust their infrastructural arrangements.

This focus on how the material infrastructure was co-produced according to the development context provides rich data on how residents’ conceptions of citizenship changed. Analysing the progression of the development reveals how residents’ forms of citizenship became co-constructed as they accepted the promise of future infrastructure. Resident centric infrastructural construction was diluted from inclusive citizenship engrained in everyday reciprocal relationships. The realities of the development’s interference caused residents to construct a more exclusionary infrastructure based on the promised prospective infrastructure. In the next sections, I will detail how relationships through infrastructure, and definitions of citizenship, are changed in this co-construction. This analysis follows this temporal co-construction capturing how citizenship was progressively altered throughout the infrastructural domain.

6. Pre-development: spaces of electricity sharing

When I first arrived in Veitiri settlement I considered myself lucky to be based in Tomasi and Josivini’s household as it had a direct connection to electricity. My feeling of luck quickly turned to frustration as this did not guarantee access to electricity whenever I wanted. There were two connection points in the household. One connection point was next to the television, and the other was in the kitchen. Each connection point had a multi-plug extension attached to it. Each multi-plug had three or four outlets to plug in electrical devices. For the multi-plug next to the television, one of its outlets was always taken by the television that was perpetually playing movies on a DVD player. Other outlets were often taken up by mobile phones of family members or neighbours or kin. The other multi-plug extension located in the kitchen was often taken up by appliances such as an electric jug and a top loading washing machine. Charging devices at night was also forbidden due to the concern of an electrical fault starting a fire which occasionally had occurred in neighbouring settlements. I was forced to pick certain moments to secure an unoccupied charging outlet at permissible times. Securing one of these outlets still did not guarantee the charging of my electronic devices, as the multi-plugs were very old and temperamental. The slightest of knocks could disconnect the charger. Even when the charger was connected, charging was extremely slow.

I found that the frustrating daily task of accessing electricity was one shared by most members of the settlement, with each having their own specific and routine systems of accessing a limited supply of electricity. I first noticed this common daily task when a woman named Maika from a nearby household came to drop off her mobile at the household on a regular basis. She dropped it off early in the morning before sunrise so that it would charge while she was doing her morning activities before she needed to leave to catch the bus to central Suva. She would also occasionally stop by the household after she returned from work as it was getting dark and collect it before she slept. These pickup and drop-offs were unceremonious with hushed and little dialogue, particularly in the morning when she would wake a member of the household with a gentle knock at the door. There was also the mandatory payment of $1 per charge to cover the cost of electricity and inconvenience. According to a one-week electricity logbook, there were 13 instances of charging at Tomasi and Josivini’s house during this period. Maika charged her mobile her phone at the household twice, 4 other close neighbours charged their mobiles at least once, and the remaining instances of charging were carried out by 2 household members. This practice of allowing neighbours to recharge their mobile phones for a fee was seemingly a practical and mundane practice.

I soon found that this practice was not only common across the settlement, but one that fostered reciprocal relationships between settlers. For the household I was living in, this small-scale exchange of coins for electricity fostered communal relationships between close neighbours. The occasional provision and access of electricity to foster relationships between close neighbours is not insignificant in the sense that it provided frequent inter-household interaction. However, for other electrified households, electricity transactions were more frequent, extended beyond close neighbours and kin, and intertwined with other reciprocal exchange relationships in and around spaces of electricity sharing, in ways that were the basis of solidifying wider settlement bonds. One of these spaces of electricity sharing was outside Kelera’s household. According to her one-week electricity logbook, there was a total of 61 instances of mobile recharging between 24 residents. 26 instances of charging were carried out by 10 household members or close kin; the remaining 35 instances of charging were carried out by 14 other residents from across the settlement.

Much like the household I was staying in, residents of the settlement charged their mobile phones at her house for a small $1 fee. Kelera’s house was in a uniquely important place in the settlement. It was the first house at the entrance of the settlement that everyone passed before diverging into a series of branching paths that lead all over the settlement. The area outside this house had an area of compacted dirt with no vegetation on it due to its location as the main foot thoroughfare, and a location where people gathered in groups upon exit or arrival in the settlement. Those that gathered were primarily settlement youth who liked to sit and listen to music coming from the large music box in Kelera’s house. They usually sat on logs with phones in hand as they shared pictures and video from Facebook, or played music that they were trying to hear over the music box. As I arrived or left the settlement I would often be stopped with handshakes as they asked me where I was going, when I would be back, and perhaps if I could lend them some small change for the day. Such greetings were had with most people in the settlement with requests to pick things up from Suva for them or to recount the events of the day gone past. In the late afternoons, youth were often called from down in the settlement up to the main road to help carry groceries/produce from a taxi to a house in the settlement. When items such as building materials, mattresses, and appliances were delivered to the entrance of the settlement youth also helped in delivery. You could sit outside Kelera’s house for the entire day and see every movement of both people and objects to and from the settlement. It was a location of establishing and maintaining settlement-wide connections through passing dialogue and general labour. Mobile recharging was integrated with these practices of exchange unique to the entrance of the settlement.

Kelera’s household was also integrated within the youth cultures surrounding the house. In this environment coins never stayed in the hands of youth for long. Youth gathered coins from selling coconuts on the main road and by carrying out deliveries. These coins changed hands very quickly through gambling on a card game called “up/down”. This game involved betting on a card landing in either an “up” or “down” pile as the dealer alternated putting cards in each. For youth, this card game distributed income to those with the most luck on their side, or as they saw it, the most prestige. These youth often would give coins to those that had demonstrated the most prestige to earn money on their behalf, or asked for money from those that had accumulated the most as a plea that their luck will change. In such an environment of frequent movement of people and currency, money is always a necessity, however, it was never far away, and it would be distributed to you in due time. Kelera and her household were spatially at the centre of this environment as well as culturally integral to its youth culture through the provision of mobile recharging that enabled the sharing of media. As a result, she was equally integrated into this high circulation, fate based micro-economy. Just as the accumulation of money was determined by prestige on any given day, Kelera had a quiet confidence that even though money was never guaranteed, it inevitably would again soon flow back to her. This form of reciprocal exchange and equitable wealth distribution through gambling is common in Melanesia (Binde, Citation2005; Mitchell, Citation1988; Zimmer, Citation1986; Zimmer‐Tamakoshi, Citation2014). In this case, this form of wealth distribution was integrated with mobile recharge payments, linking Kelera to the fate of the settlement and gambling youth culture.

Much like Kelera’s household, Sairusi and Amali’s household had a micro transaction economy that electricity provision was integrated with. However, unlike Kelera’s household, this integration was more restricted to kinship-based exchange relationships. According to their one-week electricity logbook there was 35 instances of charging. 27 instances of charging were carried out by 8 household members or close kin; 8 instances of charging were carried out by 3 neighbours.

Sairusi and Amali’s house was blanketed with an abundance of cassava plants. Sairusi spent much of his time cultivating and harvesting cassava on his property as well as other crops that he had planted on a patch of raised fertile land hidden among the mangroves. He also occasionally went fishing before sunrise with the other fishermen of the settlement. As a result, their household was perpetually stocked with produce and fish. In addition to engaging in agricultural activities, Sairusi would also often go into Suva in the evenings and purchase mobile phones at extremely low prices from people that desperately wanted to convert them to more liquid currencies. Frequently when I arrived at their house, they would show me a new device that Sairusi had acquired including laptops and ipads proudly indicating the bargain they had gotten. Much of the benefits of both these agricultural and urban products were transferred between a broader kinship network.

When I asked about the various devices that they had attached to their power points during a visit, they pointed to a battery powered light owned by Sairusi’s mother, the mobile phone of a cousin, and Sairuisi’s brother’s laptop which he used as a music player. Many of these devices were acquired by Sairusi himself during his evening trips to Suva. On one particular visit, there seemed to be an ever-revolving cast of family members walking up the path to drop off and pick up their items while their generator was running. Adults would often stay and drink tea, and eat food grown or caught by Sairusi. Children sent to pick up items would play and joke with Sairusi and Amali’s children who were playing educational games on the family ipad. Their household seemed to have appropriated electronic devises and electricity gained through Sairusi and Amali’s engagement with the urban and youth environment. These devices were appropriated into traditional norms of sharing and caring within their kinship structure as they have elsewhere across the globe (Madianou & Miller, Citation2011; Singh, Citation2013). Access to these infrastructural services was not commoditised, but rather was framed within the domain of reciprocity.

I also conducted a logbook survey at Susani’s household which indiscriminately provided mobile recharging services to other settlement residents. Susani and her family did not have any other kin living in the settlement and was renting the house from an Indian man who no longer lived there. The house had no communal area outside and was an unpleasant place for any leisure activity due to its muddy and often flooded surroundings. I was not expecting to record many instances of recharge from this household due to its spatial and social isolation but was proven wrong as she recorded in her logbook a not insignificant number of 29 instances of recharging. Most of these were made by residents from the settlement’s furthest reaches who she did not necessarily know well. This service she felt linked her to the settlement according to the ethos of “living together” which was highly aligned to collective survival in the urban environment through the espousal of traditional communal values.

These logbooks and observations surrounding electricity access points, detailed in table , reveal how distinctly different settlement relationships were fostered through reciprocal relationships surrounding infrastructure. Combined they reveal an underlying conception of infrastructural citizenship prior to the settlement’s development. Firstly, in spaces of electricity, a crucial urban utility was seized and shared among informal settlement residents. All residents were able to access electricity through settlement relationships whether at Tomasi and Josivini’s, Kelera’s, Sairusi and Amali’s, Susani’s, or the other houses in the settlement that had direct access to electricity. Residents usually charged their mobiles at houses they had a pre-established relationship with, however it was evident that a strong pre-established relationship did not necessarily need to be present as I also often observed residents who did not frequent each of these households charging their mobiles from time to time. Secondly, the way in which electricity was obtained reveals certain settlement moralities attached to infrastructure. Specifically, accessing electricity involved the maintenance of settlement relationships through reciprocal exchange that often overlapped with other socially embedded exchange. For residents with weaker personal ties to these electrified households, the standard established norms of exchange reciprocity applied with a $1 payment. The token payments in these reciprocal exchanges strengthened these previously weak settlement relationships. Thirdly, these spaces of electricity infrastructures appropriated urban objects, primarily electronics and currencies, into traditional forms of use such as the sharing of media and currency outside of Kelera’s house, or into the relationships of care within Sairusi and Amali’s kinship network (Madianou & Miller, Citation2011; Singh, Citation2013). In this sense, the electricity infrastructure that the settlement’s residents produced promoted an inclusive form of citizenship with an embedded sense of traditional morality.

Table 1. Electricity logbook overview

7. Mid-development: informal power grids

Towards the end of my first period of fieldwork in July 2017, these spaces of electricity sharing were progressively deteriorating. The social infrastructures of the spaces of electricity sharing were slowly eroding away. This erosion of the social infrastructure was set in motion by the developers who promised residents secure tenure within the settlement if they moved to the smaller land holdings indicated in Figures and . This plan greatly divided residents. Some residents refused to move their houses to allocated plots, others accepted the developer’s plans. For the former being forced to relocate, the developer’s plan that socially and spatially rearranged the settlement was seen as a betrayal of the form of traditional citizenship that they had built in the settlement. For the latter, the developer’s plan was a formal offer of inclusion into urban citizenship, not only because it offered secure land tenure, but because it promised formal access to infrastructural services. This included electricity, water, road access, and garbage collection.

The complete provision of these infrastructural services was evidently a long way from being fulfilled by the developers. Formal electricity was planned to be provided only after roads and pipes were laid, and all plots were fully allocated and occupied. Resistance by some residents to the development and contractor delays also meant that the timeline for completion was tentative and unreliable. Yet in the meantime, residents of the settlement still required electricity. The continued functioning of spaces of electricity sharing was starting to be untenable as the social infrastructure that they operated upon had disintegrated. The social and spatial rearrangement of the settlement scrambled the prior arrangements residents made to access electricity. This was most materially manifest in the clearing of space for roads which not only spatially divided the residents by large stretches of gravel shown in Figure . Clearing also in some cases destroyed the locations where electricity was previously accessed. In addition to this, the residents who fiercely resisted the development also felt morally betrayed by the residents who freely accepted the development, therefore, weakening the settlement-wide social solidarity required in offering and accepting electricity from one another. A new informal infrastructure needed to be constructed by the residents, in absence of a formal infrastructure being immediately provided. When I first left Veitiri I was unable to predict how these residents would access electricity in this transitionary period before formal electricity was eventually provided.

Six months later I was able to return to settlement in December 2017 for two weeks. When I returned, I was able to see this new infrastructural system come into fruition. It was immediately apparent that infrastructural arrangements had drastically changed. I walked down the new wide dirt pathways where roads would eventually be placed, and I noticed lines of cables erected on wooden posts overhead as well as cables on the ground covered in mud and water. The sight of a myriad of cables was new in the settlement. My new focus was to map these wires, and which houses they connected. The houses they connected seemed to be randomly and inefficiently determined. They snaked from one house to another either skirting around houses, or simply running across their roofs to reach more distant households. The cables were operating independently of each other, some even crossing each other’s path. I began to understand that in lieu of spaces of electricity sharing, the traipsing of wires from house to house was the new way of sharing electricity. Informal power grids had replaced spaces of electricity sharing.

Informal power grids allowed residents to share electricity with other people in the settlement, but this form of sharing was much less inclusive than spaces of electricity sharing. Informal power grids allowed settlers to more discernibly select people with whom they did and did not want to share electricity with. With the introduction of a moral divide in the settlement based on the resistance and acceptance of development, as well as the introduction of new residents from outside settlements including some of Indian decent, there was an increasing amount of people with whom residents did not want to share electricity with. There had previously been the understanding in the settlement that they were “living together” as if they were living in an urban village and therefore assisted one another often regardless of social relation. Informal power grids conversely allowed residents to build walls around groups of residents from which electricity could be accessed. At the end of each informal power grid, there was a dead end from which electricity extended no further. Accessing electricity through an informal power grid also often seemed to be the only way to access electricity, especially for residents who did not have a close social contact with electrified households as approaching households to charge devises was no longer common due to apparent social divides. The effect of informal power grids was a restriction of social infrastructure that settlers could draw from to rework the material and social environment to produce a collective notion of citizenship.

In addition to the social fragmentation of the settlement that informal power grids seemed to mirror, they also caused electricity to become more commodified. Electricity sharing had often involved small monetary exchanges, but this had always been within the context of broader reciprocal exchange systems whether it be in the micro-transaction youth cultures, kinship exchange systems, or mutual coping relationships. In this new infrastructural system, there seemed to be a decoupling of resource and monetary exchanges from an embedded social context. The daily standardised fee for using electricity in the informal power grid became $5. The key here is the removal of electricity sharing from contextual social relations. A switch can be flipped at a distance and payment for its use can be paid to the provider through indirect channels. The extension of informal power grids to socially distant peoples in the settlement arguably exhibit a generosity of electricity sharing within a cohesive settlement-wide social infrastructure. However, the removal of exchange transactions from broader traditionalised contexts pushes it closer to the realms of commodification.

The commodification of resident-centric infrastructure can be understood by analysing one informal grid originating at a house owned by Leba shown in Figure . Leba extended cables to Sairusi and Amali to provide electricity to them after their diesel generator broke down. In return, she was permitted to access their water source. The extension of Leba’s informal power grid initially conformed to traditionalised norms of spaces of electricity sharing. This extension represented mutual coping between people of limited social connection akin to the practices seen in spaces of electricity sharing. However, Leba did not control the extension of the informal power grid beyond Amali’s household; rather the line seemed to have an agency of its own. Amali extended the power grid to Ben’s household who was a member of Amali’s kinship network. This extension was in line with the norms of other kinship reciprocal relations. However, Ben was not part of the initial arrangement between Leba and Amali. Regardless Ben was still required to pay $5 per day for electricity but did not pay Leba directly. Every day, Ben paid Amali who subsequently paid Leba. Two other households between Amali’s and Ben’s household with no kin relation to Leba also asked to be connected into the informal power grid. These households made the same $5 daily payments to Sairusi and Amali. Another household outside of this chain and owned by Sam also asked to be connected to the grid and connected directly to Leba’s household with a separate wire. The result was an amorphous grid that connected many people of limited social contact

The nature of the expansion of Leba’s power grid connecting people with no sustained personal contact does not resemble the ethos of the spaces of electricity. There are personal relationships of exchange between Leba and Amali, and between Amali and Ben that conform to traditional ideas of communality, however, the indirect relationship between Leba and Ben introduce the idea of resource exchange without social relations. Ben seemingly could access electricity separated from a direct relationship. The presence of a depersonalised electricity connection point inside the settlement erodes the settlement encompassing traditional morality expressed in infrastructure. This power grid despite connecting people of differing levels of social connection depersonalises exchange relationships. Unlike before, no visits are made to Leba’s household, other than a visit made by Amali to deliver a cash payment of all other houses down the line. There are no acts of communality whether it be gambling or the sharing of food to accompany the transaction previously present in spaces of electricity access. Rather, there are depersonalised monetary exchanges within the settlement, which are increasingly depersonalised between households further down the chain.

The primary drivers for the establishment of informal grids in this transitionary period before the implementation of formal electricity provision in the settlement was the combined prospect of settlement development and new infrastructure. The Indian residential co-operative and the Fijian Housing Department promised residents secure land tenure and modern infrastructure if they co-operated with the development. This promise broke down the social infrastructures that sustained spaces of electricity sharing. The initiation of the development not only physically destroyed these spaces of electricity sharing but it created a moral divide between residents who resisted the developer’s plans and residents who actively accepted the developer’s plans. This moral divide created an untenable atmosphere for settlement-wide electricity sharing embedded in local exchange relationships. In absence of electricity sharing, residents acquired electricity in ways that did not require socially embedded relationships or contact in the form of connecting to an informal power grid. For many of these residents this was also a pre-emptive act of conformity and adjustment to what the formal infrastructure would eventually be. Just like the commoditisation and depersonalisation of electricity provision expected in the settlement’s formal infrastructure, residents mimicked this form of electricity provision in their own transitionary infrastructure. This pre-emptive conformity to how the settlement would be materially and socially arranged was a conscious strategy by these residents to signal to other resisting residents, the Fijian Housing Department, and often themselves, their desire to achieve the vision of the proposed settlement. In adapting to this promised infrastructure however, these informal power grids excluded other residents unlike before. Resisting residents were cut off from an essential urban resource they previously acquired through traditional reciprocal relationships in ways that claimed their status as urban citizens. Meanwhile, their continued status as residents that actively oppose the development places them in jeopardy of not securing a secure land tenure in the settlement along with neither informal nor formal access to electricity.

8. Conclusion

Social scientists are consistently dedicating more attention to infrastructures in informal settlements, specifically to investigate how ideas of citizenship in these settlements are contested through the infrastructural domain. Often this analysis focuses on how opposing resident and state-based ideas of citizenship are contested in the infrastructural domain. Many sources depict moral victories for informal settlement residents, or successful suppressions by the state (Berenschot & van Klinken, Citation2018; Rodgers & O’neill, Citation2012; Von Schnitzler, Citation2008). Few sources analyse the co-production of citizenship in the infrastructural domain that include both state institutions and informal settlement residents (Jensen & Morita, Citation2015; Koster & Nuijten, Citation2016). For many informal settlement residents, co-operation with state institutions and land developers is not only necessary but in some cases desirable. This is particularly evident in Oceanic settlements where benefits such as secure land tenure are starting to be offered (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015; Kiddle et al., Citation2017). Co-operation brings informal settlement residents into the defining of social relations around material infrastructures, and thus included in the formal defining the distribution of resources, rights, and forms of ontology that are inherent in citizenship (Jensen & Morita, Citation2015).

Despite co-operation, residents of informal settlements are not able to necessarily achieve an inclusive or locally specific form of citizenship. In Veitiri, residents were able to obtain secure land tenure through co-operation which legally incorporates settlement residents into the urban landscape. This legal incorporation is undoubtedly a positive step in expanding citizenship (Davy & Pellissery, Citation2013). However, in return for secure land tenure, social infrastructures were destroyed, and a new form of living was tacitly imposed and accepted by residents. The destruction of social infrastructures destroys more locally and culturally inclusive means of distributing infrastructural services to all residents (Amin, Citation2014; Lawhon et al., Citation2018). Residents lured by secure land tenure that could only be obtained through compliance, pre-emptively interpreted the rationale behind proposed infrastructures and constructed an infrastructure that fit state and developers plans. Residents became complicit agents in expanding an exclusionary infrastructure in the form of an informal power grid. This infrastructure not only unequally distributed infrastructural services but eradicated the reciprocal exchange relationships that were integrated with infrastructural arrangements prior to development. An urban conception of citizenship, embedded with a sense of traditional Fijian morality, was weakened within this settlement. Other settlements undergoing similar upgrades will face similar challenges. A return visit is required to analyse to what extent this local form of citizenship has further weakened post-development.

In the context of rapid urbanisation in Oceania, settlement upgrades are increasingly a part of a new emerging urban policy agenda in the region (Keen & Barbara, Citation2015; Kiddle et al., Citation2017). These upgrades represent an overdue move that promises to bring informal settlement residents into formal citizenship. However, greater attention is needed to ensure that locally and culturally specific conceptions of citizenship are maintained, otherwise, settlement infrastructural upgrades in Oceania will become yet another tool of citizenship exclusion.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lucas Watt

Lucas Watt has graduated with a PhD from the School of Media and Communications at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, funded through the Australian Research Council (ARC). The fieldwork component of his PhD research involved ethnographic immersion in an urban informal settlement in Suva, Fiji. For ten months he lived with an indigenous Fijian family in the settlement to understand the everyday challenges they experienced as rural-urban migrants striving to take advantage of opportunities in the city while maintaining the fabric of their traditional ways of living. Lucas Watt is committed to exploring emerging ideas concerning urban social change across Oceania.

References

- Amin, A. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society, 31, 137–20. doi:10.1177/0263276414548490

- Anand, N. (2012). Municipal disconnect: On abject water and its urban infrastructures. Ethnography, 13, 487–509. doi:10.1177/1466138111435743

- Appel, H. C. (2012). Walls and white elephants: Oil extraction, responsibility, and infrastructural violence in Equatorial Guinea. Ethnography, 13, 439–465. doi:10.1177/1466138111435741

- Asian Devlopment Bank. (2013) Pilot Fragility Assessment of an Informal Urban Settlement in Fiji.

- Barr, K. J. (2007). Squatters in Fiji: The need for an attitudinal change. Housing and Social Exclusion Policy Dialogue Paper no. 1. Suva: Constitutional Forum.

- Berenschot, W., & van Klinken, G. (2018). Informality and citizenship: The everyday state in Indonesia. Citizenship Studies, 22, 95–111. doi:10.1080/13621025.2018.1445494

- Binde, P. (2005). Gambling, exchange systems, and moralities. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21, 445–479. doi:10.1007/s10899-005-5558-2

- Bryant‐Tokalau, J. J. (2014). Urban squatters and the poor in Fiji: Issues of land and investment in coastal areas. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 55, 54–66. doi:10.1111/apv.12043

- Connell, J. (2003). Regulation of space in the contemporary postcolonial pacific city: Port Moresby and Suva. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 44, 243–257. doi:10.1111/apv.2003.44.issue-3

- Davy, B., & Pellissery, S. (2013). The citizenship promise (un) fulfilled: The right to housing in informal settings. International Journal of Social Welfare, 22, S68–S84. doi:10.1111/ijsw.2013.22.issue-s1

- Dornan, M. (2014). Access to electricity in small island developing states of the pacific: Issues and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 31, 726–735. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.12.037

- Elyachar, J. (2010). Phatic labor, infrastructure, and the question of empowerment in Cairo. American Ethnologist, 37, 452–464. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01265.x

- France P. (1969). The charter of the land: Custom and colonization in FIji. London: Oxford University Press.

- Graham, S. (2010). When infrastructures fail. In Graham, S. (Ed.), Disrupted cities (pp. 1–26). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gupta, A. (2018). The future in Ruins: Thoughts on the temporality of infrastructure. In N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. Appel (Eds.), The promise of infrastructure (pp. 62–80). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Harvey, P., & Knox, H. (2012). The enchantments of infrastructure. Mobilities, 7, 521–536. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.718935

- Jensen, C. B., & Morita, A. (2015). Infrastructures as ontological experiments. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 1, 81–87. doi:10.17351/ests2015.21

- Jones, P. (2016) The emergence of Pacific urban villages: urbanization trends in the Pacific islands.

- Jones, P. (2017). Formalizing the informal: Understanding the position of informal settlements and slums in sustainable urbanization policies and strategies in Bandung, Indonesia. Sustainability, 9, 1436. doi:10.3390/su9081436

- Keen, M., & Barbara, J. (2015). Pacific urbanisation: Changing times. Canberra, Australia: The Australian National University.

- Kiddle, G., McEvoy, D., Mitchell, D., Jones, P., & Mecartney, S. (2017). Unpacking the Pacific urban agenda: Resilience challenges and opportunities. Sustainability, 9, 1878. doi:10.3390/su9101878

- Kiddle, G. L. (2011) Informal Settlers, Perceived Security of Tenure and Housing Consolidation: Case Studies for Urban Fiji.

- Kiddle, L., & Hay, I. (2017). Informal settlement upgrading: Lessons from Suva and Honiara. Australia: The Australian National University Canberra.

- Koster, M., & Nuijten, M. (2012). From preamble to post‐project frustrations: The shaping of a slum upgrading project in Recife, Brazil. Antipode, 44, 175–196. doi:10.1111/anti.2012.44.issue-1

- Koster, M., & Nuijten, M. (2016). Coproducing urban space: Rethinking the formal/informal dichotomy. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 37, 282–294. doi:10.1111/sjtg.12160

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 327–343. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Lawhon, M., Nilsson, D., Silver, J., Ernstson, H., & Lwasa, S. (2018). Thinking through heterogeneous infrastructure configurations. Urban Studies, 55, 720–732. doi:10.1177/0042098017720149

- Madianou, M., & Miller, D. (2011). Mobile phone parenting: Reconfiguring relationships between Filipina migrant mothers and their left-behind children. New Media & Society, 13, 457–470. doi:10.1177/1461444810393903

- Mains, D. (2012). Blackouts and progress: Privatization, infrastructure, and a developmentalist state in Jimma, Ethiopia. Cultural Anthropology, 27, 3–27. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2012.01124.x

- McFarlane, C. (2011). The city as assemblage: Dwelling and urban space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29, 649–671. doi:10.1068/d4710

- McFarlane, C., & Rutherford, J. (2008). Political infrastructures: Governing and experiencing the fabric of the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, 363–374. doi:10.1111/ijur.2008.32.issue-2

- Mitchell, W. E. (1988). The defeat of hierarchy: Gambling as exchange in a Sepik society. American Ethnologist, 15, 638–657. doi:10.1525/ae.1988.15.4.02a00030

- Postill, J. (2011). Localizing the Internet:. An anthropological account, Berghahn Books, Oxford.

- Ranganathan, M. (2014). Paying for pipes, claiming citizenship: Political agency and water reforms at the urban periphery. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38, 590–608. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12028

- Ratuva, S., & Lawson, S. (Eds.). (2016). The people have spoken: The 2014 elections in Fiji. ANU Press.

- Rodgers, D., & O’neill, B. (2012). Infrastructural violence: Introduction to the special issue. Ethnography, 13, 401–412. doi:10.1177/1466138111435738

- Roy, A. (2003). Paradigms of propertied citizenship: Transnational techniques of analysis. Urban Affairs Review, 38, 463–491. doi:10.1177/1078087402250356

- Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71, 147–158. doi:10.1080/01944360508976689

- Simone, A., & Abouhani, A. (2005). Urban Africa: Changing contours of survival in the city. Dakar: Codesria Books.

- Singh, S. (2013). Globalization and money: A global South perspective. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Singh, S. (2017). State of the Media Review in FourMelanesian Countries-Fiji. Papua New Guinea: Solomon Islands and Vanuatu-in 2015.

- Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 377–391. doi:10.1177/00027649921955326

- Star, S. L. (2002). Infrastructure and ethnographic practice: Working on the fringes. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 14, 6.

- Tarai, J., Kant, R., Finau, G. (2015). Political social media campaigning in Fiji’s 2014 elections. Journal of Pacific Studies, 35, 89–114.

- Thornton, A. (2009). Garden of Eden? The impact of resettlement on squatters’‘agri-hoods’ in Fiji. Development in Practice, 19, 884–894. doi:10.1080/09614520903122311

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2012). Fiji: Greater Suva Urban Profile. United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- Vigh, H. (2009). Motion squared: A second look at the concept of social navigation. Anthropological Theory, 9, 419–438. doi:10.1177/1463499609356044

- Von Schnitzler, A. (2008). Citizenship prepaid: Water, calculability, and techno-politics in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 34, 899–917. doi:10.1080/03057070802456821

- Waldorff, P. (2016). ‘The law is not for the poor’: Land, law and eviction in Luanda. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 37, 363–377. doi:10.1111/sjtg.12155

- Walsh, A. C. (1978) The urban squatter question: squatting, housing and urbanization in Suva, Fiji: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography at Massey University. Massey University.

- Zapata Campos, M. J., & Zapata, P. (2013). Switching Managua on! Connecting informal settlements to the formal city through household waste collection. Environment and Urbanization, 25, 225–242. doi:10.1177/0956247812468404

- Zimmer, L. (1986). Card playing among the Gende: A system for keeping money and social relationships alive. Oceania, 56, 245–263. doi:10.1002/ocea.1986.56.issue-4

- Zimmer‐Tamakoshi, L. (2014). ‘Our Good Work’or ‘the Devil’s Work’? Inequality, exchange, and card playing among the gende. Oceania, 84, 222–238. doi:10.1002/ocea.5056