Abstract

The roles indigenous women play in forest conservation represent the spaces allocated by society on the basis of their gender. The study employs a comparative analysis of two indigenous communities in Nueva Ecija in the Philippines to describe the role of indigenous women in forest conservation and how the intersectionality of gender, ethnicity, and traditional knowledge creates an impact on forest conservation. The theory of Eco-feminism, mixed methods of qualitative, quantitative, and documentary analysis, is employed. The study shows that gender-restrictive indigenous communities create a greater degree of environmental degradation. There is a link between women and nature reflecting the different degrees of women’s subordination in patriarchy and the levels of women’s participation in forest conservation. Women of indigenous communities identified inadequate access to resources, education, and sources of income as the major challenges they face in forest conservation. It is, therefore, a challenge to indigenous women to dismantle structures encapsulating them in a situation of subordination to free the forest from the grinding effect of poverty resulting in the exploitative extraction of natural resources.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Eco-feminism draws on the concept of gender to analyze the connection between humans and nature; exploitation and degradation of the natural ecosystem; and the subordination and oppression of women. Throughout the years, indigenous peoples, whose settlements are often found on the uplands and riverbanks, and who consider hunting, planting, and foraging as the main source of livelihood, are also regarded as protectors of the environment. History would tell that the role of women in forest conservation is embedded into their culture. Nonetheless, while women contribute to forest protection as part of their traditional role, the degree of their involvement is still theoretically and conceptually linked to factors such as patriarchy and degree of freedom given to them by the community.

1. Introduction

The world has around 370 million Indigenous Peoples (IPs) belonging to 5,000 different groups scattered in 90 countries worldwide (Camaya & Tamayo, Citation2018; United Nations, Citation2009). Asia is home to 70% of Indigenous Peoples in the world (International Labour Organization, Citation2015). They have unique traditions and characteristics different from mainstream societies across the world. Republic Act 8371 defined Indigenous Peoples (IPs) as “groups of people or homogenous societies identified by self-ascription and as seen by others, who have continuously lived as organized communities on communally bounded and defined territories”. At present, there are 14 to 17 million members of indigenous communities whose presence is felt in 65 of the country’s 78 provinces in the Philippines. Of the said number, 29,976 individuals or 6,338 indigenous families are in the province of Nueva Ecija (National Commission on Indigenous Peoples Profile, Citation2013).

Indigenous Peoples are guaranteed of their rights. The 1987 Philippine Constitution recognizes the existence of Indigenous Peoples. The fundamental law affirms that the State shall (a) recognize and promote the rights of indigenous cultural communities in the framework of national unity and development (Section 22, Article II) and (b) protect the rights of indigenous cultural communities to their ancestral land subject to the provisions of the Constitution and national development policies and programs to ensure their economic, social, and cultural well-being (Section 5, Article XII; Bernas, Citation1996).

Indigenous Peoples are known to be as ecosystem people (Colchester, Citation1994). They live and adapt to the environment. They are known to have a high level of understanding of environmental protection, preservation, and mitigation of the effects of Climate Change or climatic variability in spite of them living in high-risk environments (Nursey-Bray, Palmer, Smith, & Rist, Citation2019). They also possess traditional practices proven to be environment-friendly (Gabriel, Claudio, & Bolisay, Citation2017).

Women are preservers of the environment. Long before the colonization of westerners and before the patriarchal social setting was transplanted in the Philippine soil, women from indigenous communities are already known for being preservers of the environment. History showed that indigenous women occupied higher positions than men in a pre-colonized society. They acted as medical doctors in the community referred to as “babaylans” (Agoncillo, Citation1990). They serve as political advisers to the “Datu” or Chieftain and practiced rituals and incantations expletive of their concern for the natural and human ecosystem. Similarly, indigenous women are contributors to traditional practices such as their unique ways of sustaining clean and potable water in Kalinga, Philippines (Naganag, Citation2014). They know about the conservation and protection of the ecosystem (Gabriel, Citation2017). They are originators of the present legal system based on their customary laws and practices in conflict resolution (Agabin, Citation2011). Their observance and understanding of laws intended to protect them are comparable to mainstream women (Gabriel, Citation2017).

1.1. Statement of the problem

Most of the studies on indigenous peoples and the environment dealt with the roles of IPs in general. Seldom that data were segregated and used to highlight women’s contributions in forest protection. This bias is inspired by dualist perception in a patriarchal society where credits are given to the entire population which would otherwise be attributed only to women. According to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Indigenous Peoples play an important role in the protection and management of natural resources, but the “specific practices of indigenous women, who are often the front liners in such tasks, are often overlooked”.

The present study fills the gap in knowledge from the lack of studies showing the direct contributions of indigenous women to sustainable environmental protection and development. The practices they consider adaptive to climate change are chronicled and preserved for the use of the generations to come. Based on existing literature and participants' experiences, it describes the traditional roles of women in pre-colonial Philippine society. Also, the possible interconnection between gender and forest conservation is inquired into.

Specifically, the study will answer the following:

How is the perception of indigenous women in the two study areas on Climate Change being compared?

How may the specific roles of women in the protection of forest resources be described in terms of their traditional practices and local knowledge on environmental protection?

How may the challenges and difficulties encountered by indigenous women in the protection of the environment be described?

1.2. The study locale

The study areas are the selected upland communities of Ikalahan-Kalanguya of Caraballo Mountain in Carranglan and Dumagat women of Mount Mingan in the town of Gabaldon, in Nueva Ecija. They are both in the Philippines. The selection was primarily based on the existence of both IP communities as homegrown in the Province. They are the groups with the highest number of membership living in or near the forest. They are also identified as having retained indigenous practices in the preservation of the forest. Observations would inform analysis that there is a difference in the family structure and gender orientation between the two indigenous communities. The Dumagat is observed as patriarchal in family set-up (Tan, Tayag, & Nadate, Citation2008), while the Kalanguya recognizes the role of women in family life (Camaya & Tamayo, Citation2018). The Dumagats are culturally reserved. They are stricter in their treatment of women and hold the traditional dualistic orientation of society. Important decisions in the family are made by the father while the women perform the tasks of a mother. The decision-making role in Dumagat community is performed by males while in Kalanguya community mothers and females are given space to participate in decision-making process both in the family and community. Both are rural communities with diverse socio-economic activities and capacity.

Carranglan is commonly known as “Little Baguio” of Nueva Ecija in the Philippines due to its cool mountain breeze (Valencia, Citation2004). It is considered as a first-class municipality in Nueva Ecija because of income class, number of population and total land area (Philippine Statistics Authority, Citation2015). These are the factors usually considered by local government units in measuring and categorizing municipality into classes. It has a total land area of 705.31 km2, divided into 17 “barangays” (smallest political unit in the Philippines). Two of the barangays are generally composed of IP communities. Based on the 2015 census of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the municipality has a total population of 41,131. Its distance to Metro Manila, the center of the Philippine Islands, is about 223.8 km. Its elevation is about 263 m above sea level. The municipality of Carranglan is the home for the Ikalahan-Kalanguya tribe, the migrated indigenous group from Ifugao and Mountain Province. Figure shows the location of the IP community of Kalanguya, to wit.

The agricultural products of the Kalanguyans are rice, corn, onions, and other root crops and vegetables. The climatic conditions in the area are dry season, which begins from November and ends in April while the wet season starts from May and ends by October. The people in Carranglan, especially near the watershed area, are locally known as having a long-standing experience in mitigating and adapting to climate variability and the ability to employ mechanisms and strategy to minimize its impacts (Gabriel, Citation2017). The number of their tribesmen is represented by their leader in the Municipal Council of Gabaldon. The location of Dumagat community is found in Figure .

The town of Gabaldon, where the Dumagats live, is geographically situated southeast of the Province of Nueva Ecija. The greatest concentration of IPs is in the municipalities of Gabaldon, Laur, General Tinio, and the province of Aurora. The Dumagat community generally consists of more than 100 indigenous families. They have a greater population in the province compared to the Kalanguyas. It is bounded on the southeastern section of Dingalan, Aurora; on the northwestern section by the Municipality of Laur; on the northeastern part by the Municipality of Bongabon; and the southwestern side by the Municipality of General Tinio. The total land area of the municipality is 36,623 ha (366.23 square kilometers). The area is mostly flat with hills and mountains. The climate of the municipality consists of two (2) distinct seasons. The Dry season starts from November and ends in April while the wet season starts from May and ends by October. The temperature during this period ranges from 20.5°C to 34.4°C. The total population of Gabaldon is 32,246 as per the 2010 Census of Population. Out of the total land area, 20,590 ha or 56% is devoted to agricultural purposes. There are seven (7) tourist spots that could be found in the municipality. The municipality is covered by vast upland and forest areas.

2. Methods

The qualitative, historical, and descriptive research methods are used in the study. To analyze the data, the theory of eco-feminism is applied. The tools to gather data are the survey questionnaire, informal interview, personal observation, and immersion which greatly reinforced documentary analysis and library research.

The traditional roles of indigenous women pertain to pre-Spanish period. The roles they practiced and observed in relation to the protection of the forest. These were described by the use of library research and visits to the actual communities where the elders hold the indigenous historical wisdom and practices. Several dates were scheduled to wit; November 7−12, 2017, in Gabaldon and January 23–28, 2018, in Carranglan both in Nueva Ecija. Unstructured interview was prepared and undertaken the transcription of which underwent weeding out to determine the majority of traditional roles based on their actual practices.

2.1. Selection of participants

The study was preapproved by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples-Nueva Ecija Provincial Office and the Council of Elders and participants from the two study areas. This is in compliance with Administrative Order Number 1 series of 2013 and to ensure that the procedures are in consonance with the established protocols and will not compromise the rights of the Indigenous Peoples as knowledge bearers. The indigenous women’s local observations and knowledge of preserving the environment was determined using a pre-arranged survey form. This was administered during the scheduled visits. There were 10 women of the Kalanguya and 10 Dumagat women as participants to the study. They were selected on the following set of criteria: 1) Must be a woman; 2) between 20 and 50 years old; 3) living in the community for at least 5 years; and 4) willing to participate in the study. The participants’ in the Focus Group Discussion (FGD) were with the respective Councils of Elders. The responses were tallied through the help of student tabulators. Each set of interview took 20 min. A thematic grid was prepared while transcribed themes were presented in the matrix. The researchers encountered difficulty in getting Free and Informed Consent (FIC) of the Dumagat women as they were prevented by the traditional orientation to participate in the study without the consent of their husbands. Thus, the participants from the Dumagat community were accompanied by their husbands during FGD.

The specific roles of women in forest conservation were described using personal interviews and actual observations in the study areas. The data gathered were triangulated by referring to the prepared ADSDPP (Ancestral Domains Sustainable Development and Protection Plan) in the case of Kalanguya while personal actual visual inspection in the case of Dumagat in Gabaldon, Nueva Ecija.

3. Discussion

3.1. Data analysis

The data gathered were analyzed using the historical approach to describe pre-Hispanic indigenous women’s roles. Other parts of the study are analyzed using the theoretical framework of eco-feminism. The concept of eco-feminism sees environmental degradation as a product of subordination and oppression of women (Li, Citation2010). This theory argues that environmental destruction is only an extension of the male domination of women. The patriarchy transplanted by the West in the Philippine soil not only made women less superior to men but also submissive to men’s disposition. The philosophy of eco-feminism sees the environment as part and parcel of the continuum or “logic of domination” in society resulting in environmental destruction. The “Mother Earth” concept as the one caring and nurturing all living creatures personifies women’s personality. The “twin oppressions of women and nature” is perpetuated by patriarchy along with the supporting pillars of sexism, racism, class exploitation, and ecological destruction. In other words, eco-feminism treats the exploitation of nature as an extension of the exploitation of women (Mies & Shiva, Citation1993).

3.2. The traditional roles of women in pre-colonial Philippine society

The pre-Hispanic Filipinas were respected in the community. They were naturally assigned to do the role of a caring mother of children. They took charge of the rearing of children and attended to the children’s needs while their husbands were out and earning a living. In some advanced communities, mothers also served as their children’s first teacher. Women and mothers controlled the family transactions in lieu of their husbands. Respect for women was one of the greatest virtues in a traditional society (Alcantara, Citation1994).

Attached to the functions of traditional roles of women as mothers were livelihood managers; she managed farmlands and pottery businesses. The daughter of a “Datu” or chieftain enjoys a prominent political position and a choice in the event of political succession. She also assumes the position of the “Datu” and a leader of a group of warriors. They were also treated as the “babaylan” (faith healer) or medical doctor in indigenous communities. They were believed to cure diseases using incantations and herbal medicines. The babaylan was the source of wisdom and the bearer of culture, traditional practices, and heritage. They provided aid to sustain the community’s livelihood by identifying the dates of planting, harvesting, and sowing. Traditional women’s expertise in the science of astronomy made them famous in the community as interpreter of extraordinary environmental changes.

The traditional IP families depended on forest resources for a living. As seen in history, women played the role of forest resource gatherers as they are necessary for family subsistence. Women processed and segregated fruits and foods gathered from the forests to sell to the local markets or for family consumption. Their economic needs and forest dependency made them sensitive to changes in weather patterns. Table shows the IP women’s local observations on Climate Change as they are perceived in the Indigenous communities.

Table 1. Local observations on changing weather conditions in the ancestral domains

3.3. Indigenous women’s local observations on the effects of climate change in the study areas

The local observations on climate patterns are presented in Table . The table depicts the sensitivity of Indigenous Peoples on the effect of Climate Change.

One hundred percent of the participants observed that there is a changing pattern of weather conditions. The participants agreed that there is an unpredictable pattern of weather conditions. Table also shows the perception of IP women on the decline in the presence of animal species. There is an increase in unknown variety of plants in both upland communities. The results of the survey show that changes in weather patterns, which brought climate change, are felt in the study areas. It is also perceived that violent storms have become more frequent in the vicinity.

Between the two groups, the Dumagat community experienced greater damage caused by typhoon and Climate Change. In fact, in 2013, typhoon Santi affected the Dumagat tribe more than the Kalanguya. There was also massive soil erosion in the area which displaced many tribesmen of Dumagat from their ancestral domains. The cleanest and the most beautiful watershed in the area (Gabriel, Citation2017) is now 70% destroyed because of landslide and soil erosion. The Kalanguya, on the other hand, experienced landslide because of the same typhoon, but the magnitude of the effect was only marginal. All in all, there is no difference regarding perception among two tribes on Climate Change and its impacts on the communities. The findings confirm the results of studies showing the sensitivity of indigenous communities, especially women whose gender roles are directly affected by the changes in climatic conditions and the varied uses and protection of forest resources around them (Gabriel & Mangahas, Citation2017).

The Indigenous women play a very significant role in sustainable forest protection and management. The study shows the link between patriarchy and environmental degradation. The more restrictive the society to women, the lesser they perform their role as preservers of the environment. The lesser their involvement in forest protection, the faster forest denudation may occur. The study provides contextual importance to eco-feminism as a philosophy in indigenous women's existence. The theoretical framework of eco-feminism argues that environmental degradation is a continuum of the superiority of men or oppression to some extent, by a male in patriarchy. The chauvinist perspective of interpreting events in the community restricts women’s capacity to contribute to forest protection. The paper asserts that the lesser the room for indigenous women’s self-expression and participation, the more likely the perpetuation of forest destruction. The more dominated and hierarchical the conceptualization of things within the context of the indigenous community, the more degradation of the environment is experienced.

3.4. Indigenous women’s roles in the protection of forest resources

The Thematic Grid below shows the concepts that emerged from Focus Group Discussion about the Kalanguya’s traditional practices and local knowledge on environmental protection. The Thematic Grid for Kalanguya women also shows the traditional practices where women take part side by side with men and their specific roles in the pursuit of forest protection and conservation. The Focus Group Discussion was held to validate the Kalanguya women’s responses to survey questionnaires and interview. Upon observation, the presence of variant cases is proven to be very minimal. The thematic areas are identified, and women’s roles are culled out from their statements. In Table , specific roles performed by women are enumerated, to wit.

Table 2. Themes and insights for Focus Group Discussion 1 (Kalanguya)

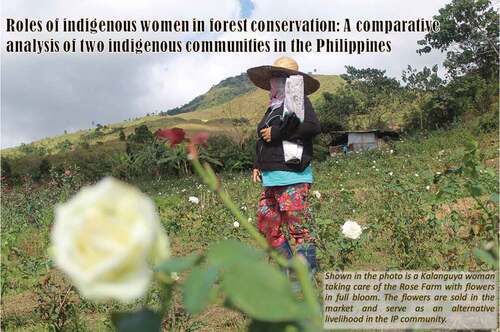

There are 13 thematic areas culled out from the interview and focus group discussion. All the thematic areas are related to the protection and preservation of the environment. As shown in Table , the women of Kalanguya actively participate in forest protection. As of November 2016, Capintalan, where the Kalanguya tribe is located has the following number of species: 234 varied tree species; 15 vine species; 23 grass species and five orchid species. The counting of flora and fauna took place in the ancestral domains of the barangay measuring 7,137.95 ha of ancestral domains showing a diverse biological life in the area (DENR Report Citation2016). The tree planting program is also gaining grounds in the area. There is already a 75% reforested area. The National Greening Program (NGP) serves as an alternative livelihood for the women of Capintalan.

3.5. The roles of indigenous women of Dumagat in the protection of forest resources

The women of Dumagat observe practices intended to preserve the environment. As shown in Table , the emerging themes of Focus Group Discussion 2 revolve around the protection of the environment.

Table 3. Themes and insights for Focus Group Discussion 2 (Dumagat) scheduled for 7 November 2017

The practice of intercropping is observed to prevent soil erosion within the Kaingin (slash and burn) area. This technique in upland farming affects the forest especially during dry season when grass fire is rampant due to hot weather temperature. Intercropping not only rejuvenates the soil but also improves the fertility of the cultivated area. In this theme, the women of Dumagat take care of the farm while men hunt for wild animals. Discriminate hunting is also a concept that emerged from the FGD. According to the members of the Council of Elders, “discriminate hunting is observed in the ancestral domains.” As practiced, men are the ones moving out to hunt for food while women take care of their children at home. Noticeable is the absence of a hunting season, for all seasons are hunting and gathering periods.

With regards to the protection of flora and fauna, the Dumagats practice discriminate gathering and cutting. The absence of endangered species allows indigenous farmers and hunters to gather fruits, hunt wild animals, and cut trees at all cost. Dumagat women do not participate in such activities. Table contains the Themes and Insights for forest conservation as observed by the Dumagat women.

As far as soil erosion is concerned, the practice of planting trees is observed. Both men and women are involved in this activity. Repeatedly, planting of trees in the watershed area is ensured by the Dumagats. The Council of Elders mentioned that they select trees to plant depending on the season. Bamboo and Kibeg are two varieties of trees that are commonly planted in the watershed area. Only men are doing this practice. Notice that other thematic concepts that emerged in the Capintalan or Kalanguya Tribe did not emerge in the Dumagat tribe during focus group discussion.

Meanwhile, the comparative environmental conditions in the communities of Dumagat and Kalanguya are presented below, showing a clear indication of variances in the status of the environment protection and preservation. For instance, the actual environmental conditions in the ancestral domains of Dumagat women do not fully support their statements. Most of the natural resources in the area are in critical condition. This variant observation is based on the 2010 Geohazards and Erosion Maps (latest available documents regarding forest condition) on file with the Bureau of Mines and Geo-Sciences, the soil condition is very alarming. Of the 36,623 total hectares, 27,281 ha or 74.49% are declared as highly susceptible to landslide. While 29,593.52 ha or 80.91% are either severely, moderately or slightly at the risk of soil erosion. This finding cannot be attributed to the Dumagat women but of the exploitation and misuse of non-Dumagat businessmen engaged in exploitative and careless extraction activities within the area.

Regarding forest condition, based on the 2010 Land Cover Map of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), the forest condition in the Dumagat area is also critical. Table shows the comparative analysis of forest land cover of the indigenous women’s communities, to wit.

Table 4. Comparative analysis of forest land cover of the indigenous communities

The forest land in the Dumagat area in 2003 was measured at 4925 ha, and after 7 years, in 2010 the measurement decreased to around 1523 ha or 30.92%, while in Kalanguya the decrease was only 4.25%. The closed forest is the part of the forest that have a dense canopy in the upper level of 70%–100% cover that allows little sunlight to penetrate to lower levels of the 36,633 ha of forest area, 15,357 is now converted to open forest due to poor forest management in the Dumagat area. It is equivalent to 41.93% of the total forest area. The study area together with barangays Tagumpay, Batting and Calabasas, where the greatest concentration of indigenous peoples is observed, is now identified as open forest. In the case of Kalanguya, a comparison of 2003 and 2010 conditions shows that there was an increase of 34.94%. Lower than the increase in Kalanguya which is 169.39%. Open forest is a part of the forest where foliage cover among mature trees may be about 30%. Light penetrates the canopy to allow a dense understory of tall shrubs or small trees.

The wooded land in the Dumagat area covered 3,604 ha in 2010. Compared to the 7,887 ha recorded in the 2003 Forest Cover Map, there has been a reduction of 4,283 ha or 54.30%. The Kalanguya, on the other hand, experienced a 1.14% increase in number. This depicts the critical condition of Mount Mingan.

The natural grassland in the Dumagat area experienced a decrease of 1,736 ha or 27.13% less compared to that of 2003. The Kalanguya tribe, however, experienced a 1, 6910.79-ha increase equivalent to 228.48%a increase.

Other land areas or built-up zones in the Dumagat area increased by 481 ha or 334.03% from 2003 to 2010. The Kalanguya tribe, on the other hand, experienced an increase of 209.66% from 2003 to 2010. Looking at the Land Cover Map of 2010, and comparing it to the Land Cover Map in 2003, one may discover the rapid rate of destruction of Dumagat ancestral domains.

4. Results

4.1. The comparative summary of emerging themes for forest protection and preservation of forest resources based on focus group discussion and interview

The comparative summary for emerging themes from Group Discussion 1 and 2 is presented below. Table shows the comparative analysis of forest land cover report in the Dumagat and Kalanguya ancestral domains which were culled from the focus group discussions scheduled on January 23–28, 2018. The data came from the Office of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources in Science City of Muñoz and Cabanatuan City in Nueva Ecija.

Table 5. Comparative summary of emerging themes for forest protection

The construction of the structure to protect the slash and burn area to prevent soil erosion is done by Kalanguya men, but the protection and maintenance are done by women. In the Dumagat tribe, both women and men in the indigenous communities perform a fair share in the maintenance and protection of the slash and burn area or the Kaingin system of farming.

Regarding the protection of wildlife, both men and women of Kalanguya can freely enter the forested area. The Kalanguya women are allowed to go out and hunt wild animals. In the Dumagat Focus Group Discussion, no such theme emerged. Even tribesmen refuse to provide specific information on their role and contribution to wildlife preservation in the ancestral domain.

Fishing in inland waters is seasonal in the Kalanguya Tribe. They observe the tradition of Dangha and Kulpi. They are rituals and festivities. It is observed in 2 days when they go out fishing. After which fishing is declared as prohibited. Women of the Kalanguya are taking care of ritual (Kulpi) and in the preparation of foods for the festivity or “Dangha”.

To prevent soil erosion, Kalanguya men construct forest slope protection using big rocks arranged in the foot of the mountain slope. The overseeing is done by Kalanguya women. In the case of Dumagat, there is no showing that the construction of protective walls made of big rocks is observed which increases the risk of soil erosion near the slash and burn area.

Burying in the forest is commonly observed by the Kalanguya since it is part of their culture. They call it “peeyaw.” The observance makes them treat the forest and trees as sacred and as a place where the spirits of their dead relatives roam. This belief made them respect trees and the forest. Women lead the performance of rituals in observance of this traditional knowledge. In the Dumagat tribe, none is mentioned during the interview and focus group discussion.

To regain soil nutrients and prevent soil erosion in foothills, women of Kalanguya decide the kind of crops and vegetables to use instead of palay, a local brand of plant-producing rice which served as a staple food for most Filipinos. This is done in the slash and burn area to strengthen the soil which usually gets loose after two seasons of planting palay rice. The women of Kalanguya take charge of the slash and burn and determination of intercrop. None of the same is observed by the women of Dumagat.

The Podong is the act of putting on warning signs in areas that are declared as sacred and vital to the survival of the community. The watershed area, source of drinking water of the Kalanguya, and the fish sanctuary are considered sacred. In these areas, nobody is allowed to enter and undertake human activities which may contaminate their source of water. The women of Kanguya protect and oversee the observance of Podong while men enforce the customary penalty for violating the Podong. In the Dumagat tribe, no specific role is performed by women to protect the environment. Environmental activities are always done or performed with the help of men except in minor activities of gathering firewood, fruits, root crops, and “bukawe” a bamboo tree used to construct their houses. In addition, the Dumagat women can decide on matters that pertain to household consumption and economy.

4.2. Indigenous women’s challenges and difficulties encountered in the protection of the environment

The following are the challenges encountered by Indigenous Women in forest protection which emerged from the survey and focus group discussions:

Little access to forest resources. As much as indigenous women would like to participate in forest protection, little access to government resources prevents them from doing so. Poverty forces them to rely on forest resources to beef-up the household economy. Most especially in the Dumagat community where sources of livelihood are limited and in one way or the other involved the use of natural resources.

In the case of Dumagat women, the absence of political representation in local policy-making body coupled with lack of organized group leaves out the indigenous women from planning, formulating and implementing policies on forest resources. They rely heavily on the male decisions.

The lack of access to education made the indigenous women and even men live in a vicious cycle of poverty and unemployment, hence there is a greater tendency to rely on forest resources for a living.

The absence of community social institutions in Dumagat tribe diminishes the impact of the forest protection initiatives.

The imbalanced social and economic development even among indigenous communities made it difficult for them to unite and make one common stand in forest conservation and protection.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

5.1. Conclusion

The study fills the gap in knowledge from the lack of studies showing the direct contributions of indigenous women to sustainable environmental protection and development by presenting data gathered from both library research, responses made by the indigenous women, and themes that emerged from the FGDs.

In terms of the perception of indigenous women in the two study areas with regard to Climate Change, the Dumagat community experienced greater damage caused by typhoon and Climate Change. The Kalanguya, on the other hand, experienced landslide secondary to the same phenomenon, but the magnitude of the effect was only marginal. All in all, there is no difference regarding perception among two tribes on Climate Change and its impacts on the communities. The findings confirm the results of studies including that of Gabriel and Mangahas (Citation2017) showing the sensitivity of indigenous communities, especially women whose gender roles are directly affected by the changes in climatic conditions and the varied uses and protection of forest resources around them.

Meanwhile, notable differences were observed between the roles of women from the two study areas in terms of Forest Protection and Preservation of Forest Resources. The women of Kanguya protect and oversee the observance of Podong while men enforce the customary penalty for violating the Podong. Tribesmen coordinate with government agencies in putting warning signs within the Dumagat area to protect the area and preserve its sanctity.

In the Dumagat tribe, no specific role is performed by women to protect the environment. Environmental activities are always done or performed with the help of men. Except in minor activities of gathering firewood, fruits, root crops, and “bukawe” a bamboo tree used to construct their houses. The Dumagat women can decide on matters that pertain to household consumption and economy.

The roles that these women play for forest protection in their respective communities portray the spaces that their society allocates for gender. The study showed that there are more to Kalanguya women when it comes to forest resources conservation and protection compared to the Dumagat women. The contextualization of the concept of hierarchy and patriarchy in the Dumagat Tribe finds expression in the relatively lesser role of women in forest conservation and protection. Their low level of participation in forest protection is deeply rooted in the overall low level of involvement in community affairs and the restrictive space that males allocate them. In the Kalanguya community, women are given the liberty not only to occupy a leadership position (Camaya & Tamayo, Citation2018) but also the freedom to participate in FGD and other activities concerning the community. And as seen in this study, eco-feminism as the theoretical foundation of the paper explains the connection between gender space and forest protection. Similarly, the present condition of the respective immediate environments may be viewed in two different levels. In the case of Kalanguya, where women seem to enjoy equal rights as that of tribesmen, also enjoy the scenic beauty and the economic value of living in a forest where old growth trees cover 75% of the land area where the watershed area is protected and sustain the water needs of the Indigenous Peoples while forest resources are processed and converted to commercial products and sold in the local market through the cooperative thereby serving as an alternative source of income for Kalanguya women.

The Dumagat tribe as it is seen and observed by the researcher is now living in an environment where the natural environment is devastated and washed out by the recent typhoons. Further contextualizing the hierarchy and the higher position occupied by males in the Dumagat community naturally restricts women from participating in any initiatives towards forest protection. The lack of women organizations in the Dumagat community made it difficult to have access to community resources including the opportunity to participate in forest protection. The Kalanguya women who are active in community organizing enjoyed access to community resources through an organized group like the WADAKA, Community Cooperative and Women’s Livelihood Cooperative in-charge of selling processed products from the forest such as herbal medicine and food supplements extracted from natural crops to be sold in the local market.

Therefore, finding the reason from the theoretical framework of eco-feminism, it can be noted that the Dumagat tribe is a highly patriarchal community while the women in the Kalanguya tribe enjoy a more independent role from men. The roles of indigenous women in forest protection and resource conservation represent the diverse degree of participation and the degree of freedom allocated for women within the indigenous communities. Nonetheless, both communities contribute to forest protection, albeit, differently and the link between patriarchy and environmental degradation remains theoretically and practically important.

5.2. Policy recommendations to further IP women’s roles in forest protection

The following recommendations were arrived at in order to address the challenges and difficulties encountered by the indigenous women of Carranglan and Gabaldon based on their responses to the survey forms, informal interviews, and Focus Group Discussions:

Linkages with funding institutions and entities must be established to support the Indigenous women’s initiatives towards forest protection. The National Greening Program (NGP) project of the Philippine government must continue to provide income for the IP women to participate and earn income. Most especially in the Dumagat community where sources of livelihood are in one way or the other, come from natural resources.

Provide opportunity for the Dumagat women to participate in forest protection planning, implementation, and policy-making. Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), Peoples Organizations (POs), and Government Agencies (GAs), and other stakeholders with similar advocacies may push for this agenda.

Provide technical and vocational training programs for the women of Dumagat and provide them employment opportunities. The same observation is not present in the Kalanguya tribe as they are more advanced and many are employed and working in the cooperative and nearby government offices.

Create more community organizations that will serve as the channel to advocate forest protection.

Provide a province-wide training program for women on social, political, and economic awareness. Adopt the sharing of information and resources towards forest management and protection.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arneil G Gabriel

Arneil G. Gabriel is the Officer in Charge of the NEUST – Center for Indigenous Peoples Education. He has done several researches on Indigenous Peoples’ rights and welfare. He is a member of the National Research Council of the Philippines. A research arm of the Philippine government.

Marianne De Vera

Marianne De Vera is a focal person of the Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology, Center for Gender and Development. She has done several projects and activities for Gender Awareness and Development.

Marc Anthony B. Antonio

Marc Anthony B. Antonio graduated from the University of Sto. Tomas, Faculty of Civil Law in 1997. He was the Class Salutatorian, a University Scholar and the recipient of the Chief Justice Roberto Concepcion for Academic Excellence. He was admitted to the Philippine Bar in 1998, and he is currently the Managing Partner and head of the Litigation and Immigration Department of the Manalo Perez Paco and Antonio Law Offices. He has also assisted indigenous people in protecting their ancestral lands, particularly in Mindanao.

References

- Agabin, P. (2011). The influence of indigenous law in the development of new concept of social justice. Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) Journal, 36, 1–18.

- Agoncillo, T. (1990). The history of the Filipino people. Quezon City, Philippines: Garotech Publishing.

- Alcantara, A. N. (1994). Gender roles, fertility, and the status of married Filipino men and women. Philippine Sociological Review, 42(1/4), 94–109.

- Bernas, J. G. (1996). The 1987 constitution of the Republic of the Philippines: A commentary. Sampaloc: Rex Bookstore, Inc.

- Camaya, Y. I., & Tamayo, G. L. (2018). Indigenous peoples and gender roles: The changing traditional roles of women of the Kalanguya Tribe in Capintalan, Carranglan in the Philippines. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 6(02), 80. doi:10.4236/jss.2018.62008

- Colchester, M. (1994). Sustaining the forests: The community‐based approach in the south and southeast Asia. Development and Change, 25(1), 69–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1994.tb00510.x

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources Report. (2016). Munoz Nueva Ecija Philippines.

- Gabriel, A. G. (2017). Indigenous women and the law: The consciousness of marginalized women in the Philippines. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 23(2), 250–263. doi:10.1080/12259276.2017.1317705

- Gabriel, A. G., Claudio, E. G., & Bolisay, F. A. (2017). Saving dupinga watershed in Gabaldon, Nueva Ecija Philippines: Insights from community based forest management model. Open Journal of Ecology, 7(02), 140. doi:10.4236/oje.2017.72011

- Gabriel, A. G., & Mangahas, T. L. S. (2017). Indigenous people’s contribution to the mitigation of climate variation, their perception, and organizing strategy for sustainable community based forest resources management in Caraballo Mountain, Philippines. Open Journal of Ecology, 7(02), 85. doi:10.4236/oje.2017.72007

- International Labour Organization. (2015). Indigenous peoples in the world of work in Asia and the pacific: A status report. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—gender/documents/publication/wcms_438853.pdf

- Li, S. (2010). Indigenous women and forest management in Yulong county, China the case of Shitou Township. Yulong Culture and Gender Research Center. Retrieved www.tebtebba.org/index.php/all-resources/category/96-panel-1

- Mies, M., & Shiva, V. (1993). Ecofeminism. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Halifax Fernwood Publishing.

- Naganag, E. M. (2014). The role of indigenous women in forest conservation in upland Kalinga province, Northern Philippines. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 3(6), 75–89.

- National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, Nueva Ecija Provincial Capitol. NCIP Profile 2013. National Commission on Indigenous People. (2013). Ancestral domain development and protection plan (ADSPP) of the Kalanguya Tribe in Carranglan. Cabanatuan: NCIP Office.

- Nursey-Bray, M., Palmer, R., Smith, T. F., & Rist, P. (2019, May 4). Old ways for new days: Australian indigenous peoples and climate change. Local Environment, 24(5), 473–486. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1590325

- Philippine Statistics Office. (2015). Retrieved from www.psa.gov.ph

- Tan, J. Z., Tayag, J. G., & Nadate, A. C. (2008). Sexual beliefs and reproductive health of indigenous Filipinos: The Higaonon of Bukidnon and the Ata Manobo of Davao. Retrieved from https://aboutphilippines.ph/files/IP_RH_Paper.pdf

- United Nations. (2009). State of the world’s indigenous peoples. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/SOWIP/en/SOWIP_web.pdf

- Valencia, L. (2004). Nueva Ecija land of golden opportunities. Intramuros: Manila Bulletin.