Abstract

In the vocational rehabilitation of persons with disabilities (BIF), the need to consider the variables related to employer demand is increasingly becoming an important research topic. This empirical research explores the perceptions and attitudes of employers in hiring and retaining people with borderline intellectual functioning (BIF). For this purpose, the Metaplan procedure was used and a focus group was conducted in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) of the Spanish Vinalopó Footwear Cluster. Results showed a significant lack of knowledge and visibility of people with BIF. Lack of financial support to encourage hiring was pointed out by participants in the group as the most relevant barrier; on the contrary, the main advantages identified are those related to corporate social responsibility, as well as image and reputation of the company. Labour difficulties for workers with BIF were also analysed. Lack of skills to organize their own tasks and insufficient job training received the highest score.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Usually, persons with disabilities have difficulties to be part of the labour market. However, if they have an official recognition of their disability, it is an easier way, due to employers have some fiscal advantage. People with borderline intellectual functioning (BIF), do not have any certification about their disability. Only if employers know the characteristics of these persons can considerate contract them. Do they know enough about BIF?

We made a meeting with executive of small and medium enterprise of the Spanish Vinalopó Footwear Cluster.

Results showed a significant lack of knowledge and visibility of people with BIF. Even so, executives consider that to include persons with BIF could improve image and reputation of the company.

It is necessary to train executives about persons with BIF. Moreover, Public Administration should provide financial support to hire persons with these characteristics.

1. Introduction

In the 1960s, the American Association on Intellectual and Development Disabilities (AAIDD) defined those with an IQ test score of 70 to 85 as eligible for classification as mentally retarded (Heber, Citation1959, Citation1961). Persons with borderline intellectual functioning (BIF) have an IQ test score that is one to two standard deviations below the mean, in the range of 70 to 85 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000). For measuring this IQ different tests are used (e.g.WISC-III; WPPSI-III or WAIS-III). Considering the normal IQ distribution, this population group should represent 13.6% of the total (Salvador-Carulla et al., Citation2013). In fact, some studies consider that a percentage between 12% and 18% of the population fits into that category (Hassiotis et al., Citation2001; Seltzer et al., Citation2005). Studies from the Netherlands show that there has been a substantial increase in the number of persons with borderline intellectual functioning (Nouwens, Lucas, Embregts, & van Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2017). However, as the use of the IQ scale is decreasing, borderline intellectual functioning has no score range in DSM-5 (Greenspan, Citation2017).

Despite the numbers, borderline intellectual functioning is an extremely complex clinical entity, which has barely been studied (Peltopuro, Ahonen, Kaartinen, Seppälä, & Närhi, Citation2014; Salvador-Carulla et al., Citation2013). There seem to be two traditions examining BIF: medical and pedagogical. A research tradition focusing on BIF for its own sake is missing. The lack of terminological consensus for the BIF phenomenon is also remarkable. The names used in the English literature include, for example, “Borderline Mental Retardation”, “Subaverage Intellectual Functioning”, “Borderline Intellectual Capacity”, “Borderline Learning Disability”, “Slow Learner”, “Mild Cognitive Impairment” and “General Learning Disability” (Peltopuro et al., Citation2014; Salvador-Carulla et al., Citation2013). A specific definition of BIF independent from other related concepts is necessary to avoid misunderstandings and to establish appropriate treatments and interventions (Contena & Taddei, Citation2017).

In a review of literature concerning BIF, in order to increase knowledge about the problems related to BIF in areas such as: academic and cognitive skills (Alloway, Citation2010; Szumski, Firkowska‐Mankiewicz, Lebuda, & Karwowski, Citation2018), motor skills (Jeoung, Citation2018; Westendorp, Houwen, Hartman, & Visscher, Citation2011), social behavior (Embregts & van Nieuwenhuijzen, Citation2009; Louw, Kirkpatrick, & Leader, Citation2019), mental health (King et al., Citation2019; Seelen-de Lang et al., Citation2019), employment (Peltopuro et al., Citation2014; Robertson, Beyer, Emerson, Baines, & Hatton, Citation2019) and marriage (Atkinson, Citation2007; Hassiotis et al., Citation2007). Peltopuro et al. (Citation2014) concluded that there is a need for longitudinal and population-based studies focusing on persons with BIF. More research is particularly needed about critical periods of life such as the transition from high school to labour market.

Article 27 of the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), approved by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 2006 and ratified by Spain in 2007, recognizes “the rights of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others”, adding that “this includes the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities”. However, the employment rate of persons with disabilities still remains remarkably low compared to the general population. In Spain, for example, according to the latest Report of the Observatory on Disability and Labor Market of ONCE Foundation, with data referring to 2017, the employment rate of persons with disabilities is only 25.9%, much lower than the average of the general population, which stands at 64.4%. The employment rate of persons with intellectual disabilities (ID) is particularly low, at a level of 19.5% (Fundación Once, Citation2018). The last specific study available on employment of persons with BIF placed their employment rate at 17% (Huete & Pallero, Citation2016).

The need to consider the variables related to employer demand is increasingly becoming an important research topic in the vocational rehabilitation of persons with disabilities (Burke, Bezyak, Fraser, Pete, & Ditchman, Citation2013; Chan et al., Citation2010). The traditional supply-side approach is no longer appropriate for achieving meaningful employment outcomes for these individuals (Chan et al., Citation2010). However, studies focused on the factors linked to labour supply, for instance, the barriers or difficulties that persons with disabilities face (Brault, Citation2012; Hassiotis et al., Citation2001; MacEachen et al., Citation2012; Pope & Bambra, Citation2005; Rosenheck et al., Citation2006; Schur, Citation2002; Seltzer et al., Citation2005; Shier, Graham, & Jones, Citation2009; Zetlin & Mutaugh, Citation1994), are more frequent than those that concentrate on labour demand, or on the multiple elements affecting companies when, for instance, hiring and retaining this group (Burke et al., Citation2013; Chan et al., Citation2010; R. Fraser, Ajzen, Johnson, Hebert, & Chan, Citation2011; Gustafsson, Peralta, & Danermark, Citation2013; Hernandez et al., Citation2012).

Furthermore, studies analysed the association between non-standard employment (temporary employment, part-time or on call work, multi-party employment relationships): adults with intellectual impairments were more likely than their peers to be exposed to non-standard employment conditions and experience job insecurity. (Emerson, Hattona, Robertsona, & Bainesa, Citation2018).

A focus group conducted in 13 major metropolitan areas of the USA with employers representing a variety of industries, company sizes and profit and non-profit organizations (Grizzard, Citation2005) stated that employers needed more accurate and practical information to dispel preconceptions and concerns about hiring and retaining persons with disabilities (Burke et al., Citation2013). Another study (Domzal, Houtenville, & Sharma, Citation2008) evidenced that 72.6% of the companies mentioned hiring people with disabilities as a major challenge since they cannot effectively perform the type of work required. Additionally, healthcare costs, workers´ compensation costs and fear of litigation were mentioned by medium-sized companies as difficulties to hire persons with disabilities. On the other hand, many positive attributes and good reasons were given by participants in the focus group study conducted by Amir, Strauser, and Chan (Citation2009); however, negative attitudes of co-workers and supervisors and the lack of supply of qualified workers with disabilities were also mentioned as major obstacles. These surveys concluded that, before demand-side employment can become truly effective, research on employer perceptions and attitudes toward hiring and retaining persons with disabilities is needed. Chan, Lee, Yuen, and Chan (Citation2002) described these attitudes as consisting of cognitive, affective and behavioural components.

As Chan et al. (Citation2010) highlighted, the limited empirical research carried out hitherto tends to concentrate on three areas of employer concern when dealing with employees with disabilities: the need to meet safety and productivity standards; adequate knowledge and experience related to hiring and retention; and the need for supportive assistance in identifying appropriate workforce support, accommodation, and vocational bridging services related to return to work and work retention (Stensrud, Citation2007).

Moreover, Burke et al. (Citation2013) examined attitudes of employers toward hiring individuals with disabilities by reviewing the employment and rehabilitation literature. Articles were classified in three areas of research of attitudes towards persons with disabilities: hiring and accommodation, the most studied area (Domzal; Houtenville & Sharma, Citation2008; Fraser et al., Citation2010; Hernandez et al., Citation2012; Morgan & Alexander, Citation2005); work performance (Greenan, Wu, & Black, Citation2002; Smith, Webber, Graffam, & Wilson, Citation2004; Unger, Citation2002); and behavioral intentions, the field to which less attention has been paid (Freeze, Kueneman, Frankel, Mahon, & Nielsen, Citation2002; Graffam, Shinkfield, Smith, & Polzin, Citation2002). Burke et al. (Citation2013) concluded that in order to successfully increase employment rates for people with disabilities, which often results in improved quality of life for these individuals, continued research on employer perceptions and development of related interventions is necessary.

The purpose of this article is to focus on the demand-side approach by exploring the perceptions and attitudes of employers to hire and retain persons with ID, and more specifically persons with BIF. The literature review conducted by Peltopuro et al. (Citation2014) increased knowledge about the problems and risk factors related to BIF and brought up the topic for societal and scientific discussion, showing the particular vulnerability of this group. As these authors concluded, people with BIF are left without official services in society because they often do not meet the criteria for special services. People with BIF are not eligible to receive a diagnosis of ID and they cannot gain access to ID-related support and services because their IQ is “too high”. Research findings point out that persons with BIF, when compared with the general population, held lower skilled jobs, earned lower wages and had longer careers in the same job. To enable a full inclusion of these individuals in society, it is essential to consider the difficulties that persons with lower-than-average intellectual abilities experience in education and job training, for example, and to develop services which can accommodate these needs. In conclusion, more research, societal discussion, and flexible support systems are needed.

At least 60.194 people in Spain are diagnosed with borderline intellectual functioning or, in any case, they face moderate difficulties in performing day-to-day tasks due to borderline intellectual functioning (Huete & Pallero, Citation2016). Fifteen percent of people with a BIF diagnosis (9,212) live in the Valencian Community (Huete & Pallero, Citation2016). One of the purposes of this paper was to identify the main research questions, in order to design a larger-scale survey on perceptions and attitudes of employers to hire and retain people with BIF, to be conducted in the future. Although company size is considered an important factor, as some studies have pointed out (Harris Interactive, Citation2010), at this stage this issue has not been considered.

2. Objectives

The general goal of this research is to have a first overview about the opinions and experiences of employers of companies of the industrial sector about employees with Borderline Intellectual Functioning.

It is specifically intended to:

Determine whether they know the meaning of the term BIF.

Identify the main barriers to hire persons with BIF.

Identify the advantage of employing persons with BIF.

Recognize the measures that it would be necessary to implement to employ persons with BIF.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The sample was selected for convenience. Similar companies’ size was considered (Fraser et al., Citation2010). In order to have less bias, the companies were from the same kind of industry. To this end, we contacted 15 of the most important companies belonging to the Spanish Vinalopó Footwear Cluster, located in the Province of Alicante. The collaboration of HR managers was requested. Nine of the 15 companies were finally selected to take part in the study.

Procedure and instruments

The study was developed through qualitative and quantitative techniques. Specifically, because of the wealth of the information that can be obtained (Mira, Pérez‐Jover, Lorenzo, Aranaz, & Vitaller, Citation2004), the Metaplan procedure was used in this case, which is a combination of nominal group, focus group and multivoting methodology, and in which perspectives and points of view of participants on Borderline Intellectual Functioning were analyzed. Usually, this first approach is used to collect information about the key research questions that should be considered in future studies (Chan et al., Citation2010; Fraser et al., Citation2010; Hernandez et al., Citation2012; Burke et al., Citation2013).

Before the group session, six basic questions that would guide the meeting were selected. For each of them, the type of methodology that could obtain more information was decided (Table ).

Table 1. Questions to drive the session

To answer the first and sixth questions, all participants spoke directly. In the other four cases, the answers were first given individually, and afterwards put together by presenting them in a panel and prioritizing them. For this prioritization, a computerized remote response system was used that allows each proposal to be scored from 1 to 5.

The entire session was recorded in audio, with prior permission from the participants.

After the metaplan, in order to contrast the problems of labour inclusion of people with BIF indicated in the literature with the opinions of experts, two questionnaires were carried out in which attendees had to assess, on the one hand, the problems that they could find as employers of persons with BIF, and, on the other hand, the degree of difficulty that they thought these persons would experience when performing a job. In both cases, the issues were evaluated on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 was a minor problem/difficulty, and 5 was a major problem/difficulty. These questionnaires were elaborated ad-hoc with the information retrieved from the literature.

The duration of the meeting was 150 min.

4. Results

4.1. Metaplan

In this section, we present the most significant answers to each question, as well as, where appropriate, the assessment made using the multivoting technique.

Regarding first and second question—“Do you know what is Borderline Intellectual Functioning?” and “Do you know any experience of companies that have employees with BIF?-, all participants, with the exception of one of them, acknowledged that they did not know the concept of Borderline Intellectual Functioning, and they even defined it as the most severe intellectual disability:

“[…] an impairment in intellectual functioning, which is reduced to the minimum expression, hindering social relationships, knowledge and development; I understand that it entails these aspects.”

The person who did know BIF pointed out that there is an employee in his company with this kind of disability. In addition, he had worked in other service enterprises, where they had hired persons with severe intellectual disability and borderline intellectual functioning. Only one participant, thus, had previous experience with persons with BIF.

Regarding the third question, Which is in your opinion the main barriers to employ persons with BIF?, the participants proposed a total of 37 ideas, of which 22 were different.

We will present these answers according to the priority given by the members of the panel. The barrier which obtained the highest score was that persons with borderline intellectual functioning must compete with persons without disabilities who want to access the same job.

“[…] persons with a recognized disability have access to the labour market, above all because the Law requires you to hire a certain number of persons with disabilities, a quota; but these people are not included there. And they are going to face competition from persons who have been trained […] it is a group in no man’s land”.

Secondly, they expressed the idea that, as people with BIF do not reach the degree of disability legally required, companies cannot obtain financial support for their hiring. In this context, participants pointed out that, due to the difficulty in diagnosing BIF, these persons cannot access the training circuit adjusted to persons with disabilities. Therefore, they are at a disadvantage both in relation to persons without disabilities and those with a recognized disability. The cause of these problems, according to members of the panel, is lack of visibility of persons with BIF. In their opinion, if this group raises awareness, they could gain access to similar aids as people with recognized disabilities.

The next barrier detected is the lack of information on borderline intellectual functioning, as well as on the possibilities of applying to this group current legal regulations on labour inclusion of persons with disabilities. They pointed out the difficulties to identify persons with this kind of intellectual impairment. In a normal selection process, they would be rejected because of the lack of adapted tests. Moreover, participants ignored if there are laws specifically aimed at persons with BIF.

On the other hand, in relation to corporate culture, participants said that actions to encourage the inclusion of persons with disabilities should start from General Management, promoting thus coherence within the company.

“That culture has to be built with values, the integration of those people. […] If not, either it will be difficult, or it will be quite a negative experience for the person.”

Another factor that, according to participants, hinders the visibility of this group is their lack of empowerment. In their opinion, it would be necessary for persons with borderline intellectual functioning to take action in order to make themselves known and fight for their rights as a group, as it has happened in the past with other disadvantaged groups.

“[…] Most of us did not know what borderline intellectual functioning was, so I think we have to work to empower those people just as we did with victims of domestic violence years ago.”

The participants shared the opinion that Human Resources departments of companies are focused on identifying and recruiting the most talented individuals, what hinders the inclusion of persons with intellectual impairments.

Moreover, there seems to be a consensus among the experts interviewed about the fact that this group is specially vulnerable to end up working in tasks that do not provide value to the company (they are monotonous, simple, repetitive, etc.) and are usually outsourced. This, in turn, implies worse working conditions.

It was also pointed out that companies have little experience in the management of diverse teams. In this context, participants mentioned that jobs are increasingly technical, and complex technology makes it difficult to incorporate people with limited capabilities.

Attitudes were also suggested as possible barriers. Both the attitude of the company’s staff and of the person with borderline intellectual functioning herself were viewed as important to ensure proper integration into the company’s human team. Participants emphasized that without a clear leadership with determination to address diversity it is very difficult to hire persons with intellectual impairments.

Another aspect highlighted was the lack of empathy of co-workers, which would hinder an adequate socialization in the company, leading in turn to low self-esteem of the person with borderline intellectual functioning.

“When your self-esteem is good, you have good relations; success in incorporation is very important, and it depends on your co-workers, the atmosphere, how you socialize […]”

On the other hand, they also considered that there are no suitable job profiles for these persons (in companies represented in this panel).

“You have to invent the post so to speak […] think about what job you could offer a person with these features.”

Finally, one of the participants defended that there should be no barrier, although he agreed that there are currently many of the barriers mentioned.

“I think that with much more information it would be much easier for us to know that these persons can adapt to a job”

Table presents an overview of the different ideas, with the average score given to each of them (scale from 1 to 5), its coefficient of variation, as well as the number of times that the idea arose spontaneously. The barrier that was mentioned more frequently was lack of financial support.

Table 2. Ideas on the barriers to hire persons with borderline intellectual functioning

Next question analysed was: Which are the advantages of employing persons with BIF? To this question the experts proposed a total of 27 answers, of which 13 were different.

The most prominent advantage was related to social responsibility, social commitment and social work of the company.

It was pointed out that hiring persons with BIF would improve the company’s social positioning. At the same time, it would contribute to a better working atmosphere, as it would foster in workers the pride of belonging to a company with social values. The issue of corporate reputation was also highlighted.

On the other hand, having a diversity of employee profiles could lead to enrichment, multiculturalism, diversity, creativity and social innovation.

“I think we have to start seeing the […] incorporation of diversity, not as a social action […] [but as an opportunity for] a generation of alternative responses. […] There are many more success stories when, from disability, from limitation or from something that is not standard, we start looking for a solution. And if we see it that way, I think we will be in a better position to convince leaders that we must strive for diversity.”

Likewise, according to experts of the group, an additional advantage is that persons with disabilities who have managed to find a job in the face of competitors without impairments show a greater capacity for effort.

Moreover, a company that hires vulnerable groups would attract new and young talented individuals, since young people appreciate organizations that take into account not only economic but also social concerns.

“it has surprised me that many people, especially young people, ask you what the company is doing from the point of view of social commitment, they have great regard for it”.

For the other workers of the company, to work with colleagues with different personal characteristics, like disability, will bring about an opportunity for personal enrichment and growth, as well as foster a greater tolerance.

“If there are very different profiles in the company, that means mutual enrichment. A much more multicultural and multidisciplinary company is always more enriching”

Finally, there was an intense debate on the idea that hiring of persons with BIF would increase the visibility of this group. On the one hand, some experts argued that it would indeed contribute to their visibility, so that they can compete on equal terms with other persons, and in this way make their integration in the labour market normal. On the other hand, it was suggested that visibility could be undesired or even unfavourable for the individual, because it would cause a social stigma.

“It is about giving voice to this kind of people […] They have the same capabilities, and they are fully employable; in other words, we should not only provide visibility, but also show that hiring them is normal.”

“I believe that this [visibility] should come from the group itself. It should know to what extent it wants to have impact, and be visible to the outside. It is not up to the companies to decide the visibility or impact this group should have […] On the contrary; maybe they do not want to be very visible or do not want that people talk about them. And we have to be very careful”

In Table , the average scores, variability and spontaneity of the answers to this question are presented. The advantage that was mentioned more frequently was enrichment among very diverse profiles within the company, followed by corporate social responsibility.

Table 3. Ratings given to ideas about the advantages of hiring persons with borderline intellectual functioning

Table 4. Ratings given to the ideas about the necessary measures to employ persons with borderline intellectual functioning

Next question asked was: What measures would be necessary to employ persons with BIF? Thirty-one ideas arose, of which 12 were different (Table ).

Experts considered especially important to give Human Resources Department a prominent position within the company, so that it is capable to make strategic decisions without depending on senior management. A high score was given also to provision of financial support to encourage hiring of persons with BIF.

Secondly, the need of a clear identification of the group was underlined, which can occur mainly through the creation of associations, thus facilitating access to subsidies for persons with disabilities. In this context, participants pointed out the need of a diagnosis, linked to the legal recognition required to qualify for financial aid.

Analysing this question the debate arose once more on whether persons with BIF wish to be identified or not. The answer of the experts was that the decision should be of the individual. Those who prefer not to be identified as members of the group would always have the option not to associate.

Participants considered also very important to have more training and information on characteristics of persons with BIF and their skills and limitations, because their job placement will be more appropriate if the competences of the person are taken into account. Related to this, it was suggested to carry out a functional analysis of workstations to adapt them to people with BIF.

“If you want to hire persons belonging to a specific group, you will have to do the organizational design that allows you to incorporate them”

The need of facilitating access to training was also pointed out, as well as the need of devoting time to these persons:

“[…] I think you have to devote time to these persons, not just the normal mentoring you do when a person joins your company […] Dedication to that person cannot be the same as to a person who does not have borderline intellectual functioning.”

Raising awareness of the needs of disadvantaged groups, both within management and among all workers of the organization, was considered an important requirement. Participants suggested, in particular, to include specific subjects on disability and employability in both undergraduate and postgraduate training. In this way, the development of a social conscience would be promoted from the early stages of vocational training of professionals working in the area of Human Resources. This would facilitate the socialization process of persons with disabilities within companies.

During the discussion, special attention was also paid to the proper size of Human Resources department. In big companies where this Department counts on a large staff, the tasks required for an appropriate integration of persons with disabilities, like tutoring and mentoring, will be better managed. On the contrary, in small companies with a limited personnel department, those tasks will be shifted into the background by other priorities.

Finally, it was proposed to approve a Law that requires companies to hire persons with BIF. However, some participants did not agree with this solution. They argued that there will always be cases of disadvantaged persons that are not covered by Law.

As can be seen, the need that was mentioned most frequently was training and information on the characteristics of persons with BIF, followed by identification of the group.

Last question asked was: What tasks and functions could be performed by persons with BIF? The answers to this question, as happened in the first one, did not obtain a quantitative assessment. Experts agreed that persons with BIF could perform basic and mechanical tasks.

“Gardening, maintenance, storage, online order preparation, basic administrative tasks, technical tasks by computer, such as photo layout … ”

Several experts also underlined that partnership with associations, already mentioned in the answer to previous questions, would help to design the tasks which are more suitable for each person.

“[…] to evaluate which kind of tasks can be performed by each person belongs to the role of the association. You should receive a report from the association telling you that this person is able to do this and that […]”.

“[…] when you go hand in hand with an association that has a well-developed employment axis, it has specialized professionals that can advise you very well”.

Questionnaires

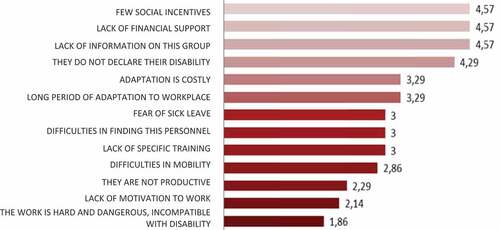

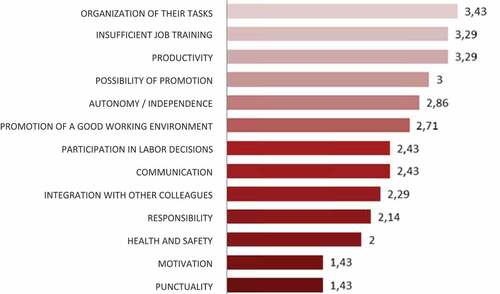

Finally, participants answered two questionnaires in order to contrast their opinions with the barriers to integration in the labour market of persons with BIF pointed out by scientific literature. In the first one they had to rate from 1 to 5 the problems they could face as employers, and in the second one the difficulties these persons would find when performing a job, being 1 a minor problem/difficulty and 5 a major problem difficulty.

As can be seen in Figure , there is a great degree of coincidence between barriers mentioned in literature and those suggested by participants in the panel.

The problems that obtained the highest rating, with a score close to the maximum, were that there are not enough social or economic incentives and that, in addition, it is an unknown sector of the population.

Next, the difficulties that BIF people would have to face in the labour market were evaluated (Figure ).

5. Discussion

The main goal of this research was to know the opinions and experiences of employers of the industrial sector with regard to persons with BIF. In this context, the first specific objective was to determine whether they knew the meaning of the term “borderline intellectual functioning”. The results show that there is a significant lack of knowledge of the features of this kind of disability. In line with the study by Grizzard (Citation2005), it becomes clear that employers need more information and training on this subject, because the integration of a group into the labour market can hardly be promoted if employers do not know its existence and characteristics. Therefore, the first conclusion is that associations should promote the visibility of persons with BIF, providing training and tools that can facilitate their hiring.

The next goal was to determine the barriers to employ persons with BIF. In addition to the lack of information already mentioned, the barrier which was pointed out as most significant was that persons with borderline intellectual functioning must compete with persons without disabilities who want the access the same job. To this fact it should be added that there is no financial support to hire persons with BIF, which does happen with persons who have a certificate of disability. Another barrier considered substantially important is the lack of visibility of this group.

Domzal et al. (Citation2008) pointed out that in 72.6% of the cases the fear that persons with BIF would not perform their work appropriately was identified as the first barrier. On the contrary, in our panel the difficulties related to this aspect—such as “increasingly technical positions”, “no suitable job profiles”, “insufficient job training”- received a score lower than 3.50/5. So, it seems that, for the participants in this panel, the barriers would be more external than internal; in other words, they would have to do with lack of opportunities rather than with lack of training and/or skills. Moreover, Domzal et al. (Citation2008) indicate that in medium-sized companies’ health costs, compensation costs and fear of litigation were highlighted as major barriers; these aspects were not mentioned at all by our group of experts. Amir et al. (Citation2009) emphasized the barriers regarding the attitude of supervisors and peers, as well as the lack of specific training. This has a great connection with several barriers suggested by participants in the panel and rated with a high score, as “lack of inclusion values” and “corporate culture”. Thus, in line with Amir et al. (Citation2009), Chan et al. (Citation2002) and Peltopuro et al. (Citation2014), a further conclusion would be that it is necessary for employers to work on the perception and attitudes towards persons with BIF. In this line, employers too have a responsibility to increase the employment rate of people with learning disabilities (Woittiez, Eggink, Putman, & Ras, Citation2018)

The third specific goal was to identify the advantages of employing persons with BIF. As has been seen, the answers that obtained the highest scores were those related to corporate social responsibility and reputation of the company. This aspect should not only be considered from the perspective of companies, but also from the perspective of persons with BIF. They minimize the potential negative effects of BIF once they are hired, while reducing at the same time the social cost of their non-insertion (Cruitt, Boudreaux, Jackson, & Oltmanns, Citation2018). This leads to consider hiring people from this group as a method of supporting social and labour integration.

The last objective was to recognize the measures that it would be necessary to implement in order to increase the employment of persons with BIF. A great importance was given to the role and position of Human Resources Department within the company, as well as to the provision of financial support to encourage hiring. It was also considered desirable that associations of the disability sector play an active role, both to promote the recruitment of persons with BIF and to facilitate their adaptation within companies. In this context, it is interesting to remark that the results of the questionnaire on the difficulties of persons with BIF to perform a job showed that those with a higher score can be learned and trained. Therefore, another important conclusion, in line with the recommendations by Stensrud (Citation2007) and Chan et al. (Citation2010), is that counseling and support through associations of the disability sector are essential to achieve a successful and lasting adaptation to workplace.

6. Limitations

The study is transversal. In addition, only a relatively small sample of human resources managers of footwear companies in the Cluster of the Vinalopó took part. It would be convenient to perform a quantitative study with a larger sample. In this way, the results found here could be confirmed or refined.

Acknowledgements

This study has received funding from the Research Project “Instruments and strategies for labor inclusion of persons with intelectual disabilities”, with reference AICO 2019/167, financed by the Department of Education of the Valencian Government.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Juan Carlos Marzo Campos

This work is part of the research developed in the unit on Disability and Employment of Miguel Hernández University. This unit provides a successful example of partnership among the university, a big enteprise (TEMPE), and service provider for people with disabilities (APSA). The Unit is entirely financed by Tempe, while APSA provides its technical support and its valuable experience in the field of disability.

The team is composed by specialist people in law, economy and psychology, and other academic fields. The objective is to develop applied research in order to facilitate employability of the people with disability.

In the training section are offered different courses for persons with disabilities, professionals, executives, and for anyone who are interested in the inclusion of people with disabilities.

References

- Alloway, T. P. (2010). Working memory and executive function profiles of individuals with borderline intellectual functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(5), 448–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01281.x

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Amir, Z., Strauser, D. R., & Chan, F. (2009). Employers’ and survivors’ perspectives. In M. Feuerstein (Ed.), Work and cancer survivors (pp. 73–89). New York: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-72041-8_3

- Atkinson, E. (2007). Thirty years on: A study of former pupils of a special school. British Journal of Special Education, 11(4), 17–24. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8578.1984.tb00251.x

- Brault, M. W. (2012). Americans With Disabilities: 2010 Current Population Reports. Retrieved from http://www.includevt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2010_Census_Disability_Data.pdf doi:PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Burke, J., Bezyak, J., Fraser, R., Pete, J., & Ditchman, N. (2013). Employers’ attitudes towards hiring and retaining people with disabilities: A review of the literature. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counseling, 19, 21–38. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/australian-journal-of-rehabilitation-counselling/article/employers-attitudes-towards-hiring-and-retaining-people-with-disabilities-a-review-of-the-literature/C7D3A0286B94AE2883CF49336328DFE4

- Chan, C. C. H., Lee, T. M. C., Yuen, H.-K., & Chan, F. (2002). Attitudes towards people with disabilities between Chinese rehabilitation and business students: An implication for practice. Rehabilitation Psychology, 47(3), 324–338. doi:10.1037/0090-5550.47.3.324

- Chan, F., Strauser, D., Maher, P., Lee, E.-J., Jones, R., & Johnson, E. T. (2010). Demand-side factors related to employment of people with disabilities: A survey of employers in the midwest region of the United States. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(4), 412–419. doi:10.1007/s10926-010-9252-6

- Contena, B., & Taddei, S. (2017). Psychological and cognitive aspects of borderline intellectual functioning. A systematic review. European Psychologist, 22(3), 159–166. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000293

- Cruitt, P., Boudreaux, M. J., Jackson, J. J., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2018). Borderline personality pathology and physical health: The role of employment. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment, 9(1), 73–80. doi:10.1037/per0000211

- Domzal, C., Houtenville, A., & Sharma, R. (2008). Survey of employer perspectives on the employment of people with disabilities: Technical report (Prepared under contract to the Office of Disability and Employment Policy, U.S. Department of Labor), McLean, VA: CESSI.

- Embregts, P., & van Nieuwenhuijzen, M. (2009). Social information processing in boys with autistic spectrum disorder and mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(11), 922–931. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01204.x

- Emerson, E., Hattona, C., Robertsona, J., & Bainesa, S. (2018). The association between non-standard employment, job insecurity and health among British adults with and without intellectual impairments: Cohort study. SSM Population Health, 4, 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.02.003

- Fraser, R., Ajzen, I., Johnson, K., Hebert, J., & Chan, F. (2011). Understanding employers’ hiring intention in relation to qualified workers with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 35(1), 1–11. doi:10.3233/JVR-2011-0548

- Fraser, R. T., Johnson, K., Hebert, J., Ajzen, I., Copeland, J., Brown, P., & Chan, F. (2010). Understanding employers’ hiring intentions in relation to qualified workers with disabilities: Preliminary findings. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(4), 420–426. doi:10.1007/s10926-009-9220-1

- Freeze, R., Kueneman, R., Frankel, S., Mahon, M., & Nielsen, T. (2002). Passages to employment. International Journal of Approaches to Disability, 23(3), 3–13. Retrieved from http://www.ijdcr.ca/VOL01_01_CAN/articles/freeze.pdf

- Fundación Once. (2018). Informe sobre Discapacidad y Mercado de Trabajo. Madrid. Retrieved from https://www.odismet.es/sites/default/files/2019-04/Informe%204%20Odismetv2_0.pdf

- Graffam, J., Shinkfield, A., Smith, K., & Polzin, U. (2002). Journal of vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 17(3), 175–181. Retrieved from https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-vocational-rehabilitation/jvr00157

- Greenan, J. P., Wu, M., & Black, E. (2002). Perspectives on employing individuals with special needs - ProQuest. Journal of Technologies Studies, 28(1/2), 29. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/217779014?pq-origsite=gscholar

- Greenspan, S. (2017). Borderline intellectual functioning: An update. Current Opinion Psychiatry, 20(2), 113–122. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000317

- Grizzard, W. (2005). Meeting demand-side expectations and needs. Paper presented at the ADA 15th Anniversary Seminar, Washington, DC: Anniversary Seminar, Washington, DC.

- Gustafsson, J., Peralta, J. P., & Danermark, B. (2013). The employer’s perspective on Supported employment for people with disabilities: Successful approaches of Supported employment organizations. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 38(2), 99–111. doi:10.3233/JVR-130624

- Harris Interactive. (2010). Kessler foundation/national organization on dissability survey of employment of people with disabilities. Paper presented at the Cornell University Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Employment Policy for Persons with Dissabilities webinar. October, 18, 2010.

- Hassiotis, A., Strydom, A., Hall, I., Ali, A., Lawrence-Smith, G., Meltzer, H., … Bebbington, P. (2007). Psychiatric morbidity and social functioning among adults with borderline intelligence living in private households. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(2), 95–106. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.01001.x

- Hassiotis, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Byford, S., Tyrer, P., Harvey, K., Piachaud, J., … Fraser, J. (2001). Intellectual functioning and outcome of patients with severe psychotic illness randomised to intensive case management. Report from the UK700 trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry: the Journal of Mental Science, 178(2), 166–171. doi:10.1192/BJP.178.2.166

- Heber, R. (1959). A manual on terminology and classification in mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 56. (Monograph Supplement, Rev.)

- Heber, R. (1961). Modifications in the manual on terminology and classification in mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 65, 499–500.

- Hernandez, B., Chen, B., Araten-Bergman, T., Levy, J., Kramer, M., & Rimmerman, A. (2012). Workers with disabilities: Exploring the hiring intentions of nonprofit and for-profit employers. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 24(4), 237–249. doi:10.1007/s10672-011-9187-x

- Huete, A., & Pallero, M. (2016). La situación de las personas con borderline intellectual functioning en España. Revista española de Discapacidad, 4(I), 7–26. doi:10.5569/2340-5104.04.01.01

- Jeoung, B. (2018). Motor proficiency differences among students with intellectual disabilities, autism, and developmental disability. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 14(2), 275. doi:10.12965/jer.1836046.023

- King, T. L., Milner, A., Aitken, Z., Karahalios, A., Emerson, E., & Kavanagh, A. M. (2019). Mental health of adolescents: Variations by borderline intellectual functioning and disability. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 1231–1240. doi:10.1007/s00787-019-01278-9

- Louw, J. S., Kirkpatrick, B., & Leader, G. (2019). Enhancing social inclusion of young adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of original empirical studies. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. doi:10.1111/jar.12678

- MacEachen, E., Kosny, A., Ferrier, S., Lippel, K., Neilson, C., Franche, R. L., & Pugliese, D. (2012). The “Ability” paradigm in vocational rehabilitation: Challenges in an Ontario injured worker retraining program. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 22(1), 105–117. doi:10.1007/s10926-011-9329-x

- Mira, J. J., Pérez‐Jover, V., Lorenzo, S., Aranaz, J., & Vitaller, J. (2004). La investigación cualitativa: Una alternativa también válida. Atención Primaria, 34, 161‐169. doi:10.1016/S0212-6567(04)78902-7

- Morgan, R. L., & Alexander, M. (2005). Journal of vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 23(1), 39–49. Retrieved from https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-vocational-rehabilitation/jvr00295

- Nouwens, P. J. G., Lucas, R., Embregts, P. J. C. M., & van Nieuwenhuizen, Ch. (2017). In plain sight but still invisible: A structured case analysis of people with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 42(1), 36–44. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2016.1178220

- Peltopuro, M., Ahonen, T., Kaartinen, J., Seppälä, H., & Närhi, V. (2014). Borderline intellectual functioning: A systematic literature review. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 52(6), 419–443. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-52.6.419

- Pope, D., & Bambra, C. (2005). Has the disability discrimination act closed the employment gap? Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(20), 1261–1266. doi:10.1080/09638280500075626

- Robertson, J., Beyer, S., Emerson, E., Baines, S., & Hatton, C. (2019). The association between employment and the health of people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. doi:10.1111/jar.12632

- Rosenheck, R., Leslie, D., Keefe, R., McEvoy, J., Swartz, M., & Perkins, D. (2006). Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(3), 411–417. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411

- Salvador-Carulla, L., García-Gutiérrez, J. C., Ruiz Gutiérrez-Colosía, M., & Artigas-Pallarés, J.. (2013). Funcionamiento intelectual límite: Guía de consenso y buenas prácticas. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.), 6, 109–120. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2173505013000083 doi:10.1016/j.rpsm.2012.12.001.

- Schur, L. (2002). The difference a job makes: The effects of employment among people with disabilities. Journal of Economic Issues, 36(2), 339–347. doi:10.1080/00213624.2002.11506476

- Seelen-de Lang, B. L., Smits, H. J. H., Penterman, B. J. M., Noorthoorn, E. O., Nieuwenhuis, J. G., & Nijman, H. L. I. (2019). Screening for intellectual disabilities and borderline intelligence in Dutch outpatients with severe mental illness. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(5), 1096–1102. doi:10.1111/jar.12599

- Seltzer, M., Floyd, F., Greenberg, J., Lounds, J., Lindstrom, M., & Hong, J. (2005). Life course impacts of mild intellectual deficits. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 110(6), 451–468. Retrieved from http://www.aaiddjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[451:LCIOMI]2.0.CO;2

- Shier, M., Graham, J. R., & Jones, M. E. (2009). Barriers to employment as experienced by disabled people: A qualitative analysis in Calgary and Regina, Canada. Disability & Society, 24(1), 63–75. doi:10.1080/09687590802535485

- Smith, K., Webber, L., Graffam, J., & Wilson, C. (2004). Employer satisfaction, job-match and future hiring intentions for employees with a disability. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 21(3), 165–173. Retrieved from https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-vocational-rehabilitation/jvr00265

- Stensrud, R. (2007). Developing relationships with employers means considering the competitive business environment and the risks it produces. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 50(4), 226–237. doi:10.1177/00343552070500040401

- Szumski, G., Firkowska‐Mankiewicz, A., Lebuda, I., & Karwowski, M. (2018). Predictors of success and quality of life in people with borderline intelligence: The special school label, personal and social resources. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(6), 1021–1031. doi:10.1111/jar.12458

- Unger, D. D. (2002). Employers’ attitudes toward persons with disabilities in the workforce. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(1), 2–10. doi:10.1177/108835760201700101

- Westendorp, M., Houwen, S., Hartman, E., & Visscher, C. (2011). Are gross motor skills and sports participation related in children with intellectual disabilities? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(3), 1147–1153. doi:10.1016/J.RIDD.2011.01.009

- Woittiez, I., Eggink, E., Putman, L., & Ras, M. (2018) An international comparison of care for people with intellectual disabilities. The Netherlands Institute for Social Research. Available on the website: https://www.scp.nl/Publicaties/Alle_publicaties/Publicaties_2018/An_international_comparison_of_care_for_people_with_intellectual_disabilities

- Zetlin, A., & Mutaugh, M. (1994). Whatever happened to those with borderline IQs? American Journal of Mental Retardation, 5, 463–469. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1990-17492-001