Abstract

The study examined the challenges on revenue generation among state universities in Zimbabwe. The situation at state universities is unbearable because of rising inflation, worsening economic and political challenges facing Zimbabwe for close to three decades without any sign of improvement. A case study approach was used to purposively select twelve (12) participants drawn from the two urban state universities. Two university financial directors and 10 senior members of staff from the selected universities were interviewed. An inductive approach to analysing the responses allowed themes and categories to emerge. The study established that the current legislation, macro-economic and political environment, reduction in government support and diminishing grant funding were noted as major barriers to revenue generation among state universities in Zimbabwe. On the way forward, there is need for the universities to be given the autonomy to determine their own fees and activities. University administrators need to be resolute, innovative, determined and creative.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study examined the challenges to revenue generation among state universities in Zimbabwe. The economic and political environment in Zimbabwe from 2000 to date has been so unstable and unpredictable that it has reduced government’s fiscal space to fully support activities at state universities. Hyperinflation has led to raised poverty levels, financial crisis and inadequate provision of learning resources at state universities. A case study approach was used to twelve (12) (two university financial directors and ten senior members of staff) purposively sampled participants. After interviewing the participants, an inductive approach to analyse the responses was done to allow themes and categories to emerge. The study established that the current legislation, macro-economic and political environment, reduction in government support and diminishing grant funding were noted as major barriers to revenue generation among state universities in Zimbabwe. This study recommended innovative, transnational funding partnerships and other sources of support for continuing growth, including private capital funding for the attainment of quality education in Zimbabwe.

1. Background to the study

Public universities around the globe have faced financial challenges amidst escalating social demands for higher education. The severities of these challenges vary across the globe, with countries in Sub-Saharan Africa being the most affected. In Pakistan, government revenues have declined, and most universities have suffered in terms of reductions in resources (World Bank, Citation2015). Similarly, in New Zealand, funding was also cut for scholarships and university special projects (Chinyoka, Citation2018). These general cuts to the university budgets have especially discouraged the development of infrastructure projects meant to increase access to tertiary education (Mutambara & Chinyoka, Citation2016).

Studies by (Zhao & Zou, Citation2015; EUA, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012 &, Citation2015) established that the current economic situation is very hard for many universities in China. A 2017 report in China noted that the government has already given bailout resources to fund indebted universities. In Colombia, low-income students were particularly affected during the crisis of the early 2000 s (Manayiti, Nyoni & Dube, Citation2015). As this group is unable to save for the investment in tertiary education, prospective students from poor and middle-income families were much less likely to attend a university while students from high-income background continued to do so leading to greater educational inequality (World Bank, Citation2013).

The rapid population growth in Africa has raised social demand for higher education, resulting in the challenge of sustainable financing (World Bank, Citation2015). For instance, the mean ratio between the average increase in the number of students and the increase in resources from 1991 and 2006 is 1.45 (World Bank, Citation2010). In line with the above argument, World Bank (Citation2010) established that the total number of students pursuing higher education in Sub-Saharan African universities has tripled since 1991, rising from 2.7 million to 9.3 million in 2006. In sub-Saharan African countries higher education student enrolment has increased from 660 thousand in 1985 to over 3.4 million (over four-fold) in 2005. The increase in some countries, such as Cameroon (from 21 to 99 thousand), Kenya (from 21 to 108 thousand), Ghana (from 8 thousand to 110 thousand), Nigeria (from 266 thousand to 1.3 million), Ethiopia (from 27 thousand to 191 thousand) and Uganda (from 10 thousand to 88 thousand) has exacerbated the challenge of sustainable financing among universities in Africa (Global Education Digest, Citation2003; 2004; 2006; 2007; UNESCO/World Bank, Citation2010). In spite of rapid enrolment growth in the higher education sector, Africa’s higher education gross enrolment ratio (GER) participation of the 18–23 years age-cohort—remains the lowest in the world around 5%, trailing South Asia (10%), East Asia (19%), and North Africa and Middle East (23%) (World Bank, Citation2010). If the current trend continues, the total number of university students in the African continent could reach between 18 million and 20 million by 2015 (World Bank, Citation2010). It should be noted that the rapid increase in university students does not align to resources. African governments are investing in higher education; hence, this worsens the plight of African universities. The expansion of the university system in Zimbabwe was mainly in response to ripple effects created by massive expansion of primary and secondary education soon after the attainment of political independence in 1980 (Zhou et al., Citation2016). While in 1980 only 2 240 students attended university today over 75 000 are enrolled for university education (Kariwo, Citation2007). Thus, the challenge for higher education in Zimbabwe is the ability to cope with the ever-increasing numbers of those potential students absorbed in higher education institutions.

Zimbabwe’s higher education system has not been immune to the tense political situation and harsh socio-economic conditions that prevailed for over a decade. The once revered education system is now a shadow of its former self (Mutambara & Chinyoka, Citation2016). Many institutions of higher learning have not been operating at full capacity for years, depriving millions of students their right to quality education. With 10 state universities and already aiming for a university in every province, the country’s higher education sector is in a crisis as it aims for quantity and not quality of education (Shizha & Kariwo, Citation2016). Having scored significant gains between 1980 and 2005, the higher education sector in Zimbabwe is currently battling with a number of challenges which require urgent attention.

Zimbabwe experienced very extreme economic hardships leading to rising poverty levels, high levels of unemployment, the decline of the provision of basic public services and financial crisis which culminated into inadequate provision of learning infrastructural facilities, delayed/non-payment of salaries and bonuses, strike actions and lack of commitment to work among staff members at universities (Mufudza et al., Citation2013; Mutambara & Chinyoka, Citation2016).

Higher education in Zimbabwe faces challenges which include dropouts, high tuition and accommodation fees, under funding, staff shortages and economic decline and large public debt (Shizha & Kariwo, Citation2016). The government’s budgetary allocation to the higher education has been in drastic decline (Chetsanga, 2010). The challenges highlighted above have impacted on the functions and operations of universities in Zimbabwe. A slight improvement was noted after the introduction of the multicurrency system which was done in 2009 and lasted in June 2019. To date, the situation at state universities is unbearable because of rising inflation and serious economic challenges facing the country.

University education in Zimbabwe, traditionally was “heavily subsidized by the government (80%) for their capital and recurrent expenditures (Madzimure, Citation2016). The same author alluded that only 15% funding comes from the fees and 5% from other sources. In the past 3 years, Zimbabwe has been experiencing serious economic, social and political challenges and the government has failed to live up to its responsibility of supporting universities fully from the fiscus. The reduction in government support was unplanned and abrupt thus affecting the running of almost all state universities. Underfunding from the government has resulted in outdated and primitive technological equipment in higher institutions of learning (Garwe, Citation2014). Gandawa (Citation2016) as cited in Madzimure (Citation2016) reported that the laboratories in most institutions are poorly equipped and lack reagents to use. It is against this background that this study examines the challenges faced by universities today with the aim of proposing sound innovative solutions to the problems.

2. Theoretical framework

The study is grounded in Gibran and Sekwat (Citation2009) open system theory. The application of the open system theory perspective offers an opportunity to identify external and internal factors that influence revenue generation strategies in the context of Zimbabwean state universities. Open systems have boundaries which define what the system should include, and an environment, which can affect it but which it can only influence, but not control it (Gibran & Sekwat, Citation2009). Thus, the activities that take place in one part of the system can affect the other parts, and ultimately the system as a whole.

At university level, the various sub-parts or sections, departments, faculties, the executive, and the bursary (microsystem), members from the community including the business people (mesosystem) and the government and nongovernmental organisations (macrosystem) work in collaboration to come up with survival strategies universities can employ for sustainable financial development. The political and socio-economic environment consists of the wider system, or context, within which the university functions. The intergovernmental system, other universities, external auditors and interest groups (exosystem) are also part of the environment hence many heads are present to receive information, make decisions and direct action for economic revival of universities.

3. Objective of the study

To examine the challenges of revenue generation at two state universities in Zimbabwe.

4. Methodology

For this particular study, phenomenological methods, which are qualitative in nature, were used as they are usually effective in making participants bring out their own life experiences. This, in turn, makes the research report quite descriptive.

5. Research design

A case study approach was used to highlight the barriers to revenue generation among universities in Zimbabwe through how they are perceived by the two finance directors and ten senior members of staff interviewed. A case study design was developed in order to gain insights into the challenges faced by universities in Zimbabwe (White, Citation2012; Yin, Citation2012). Further, when the researcher desires to understand a complex social phenomenon, the case study permits the integration of as many methods as possible to explore a contemporary situation (Yin, Citation2012). One of the advantages of the case study approach is that it allows the researcher to gain an understanding of social phenomena from participants’ perspectives in their natural settings (Saunders et al., Citation2010).

6. Sampling

In this study, the sample of twelve (12) was drawn from two university financial directors and 10 senior members of staff from the two urban universities studied. The two universities were chosen because of their accessibility to the researchers. The universities have been operating for more than 20 years. Creswell (Citation2014) asserts that determining an adequate sample size in qualitative research is ultimately a matter of using one’s own judgment and experience in evaluating the quality of the information collected against the use to which it is to be put, the particular research method. The purposive sampling strategy was employed to choose the participants. Purposive sampling was considered by Creswell (Citation2014) and Pellissier (Citation2007) as the most important kind of non-probability sampling to identify the primary participants. In this study, the sample was selected on our judgment from various heads of departments and management, looking for those who have had at least five years experience relating to the university revenue-generating process in Zimbabwe.

7. Data gathering methods

The researcher made use of semi-structured in-depth interviews. The two vice-chancellors, two bursars and eight heads of departments from the teaching and non-teaching staff were interviewed by the researchers. According to Kvale (Citation2009) an interview allows people to convey to others a situation from their own perspective and their own words. Furthermore, Johnson and Christensen (Citation2014) highlight that interviews provide in-depth information including information about the participant’s internal meanings and ways of thinking.

8. Data analysis

An inductive approach to analysing the responses to interviews was undertaken to allow patterns, themes, and categories to emerge rather than being imposed prior to data collection and analysis (Leedy & Ormrod, Citation2005 & Patton, Citation2012). Participants’ responses were recorded verbatim and read thoroughly and repeatedly. The data were organised under themes based on the narrative explanations and opinions of respondents. The most illustrative quotations were used to buttress important points that emerged from the data gathered from the respondents. The interview guide was validated and the credibility and trustworthiness of data were ascertained.

9. Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct the study was secured from the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, as well as from the selected participants. Confidentiality was upheld. Deception was discouraged and the researcher tried to build trust and transparency. A brief description of the results of the study was given to the participants.

10. Findings and discussion

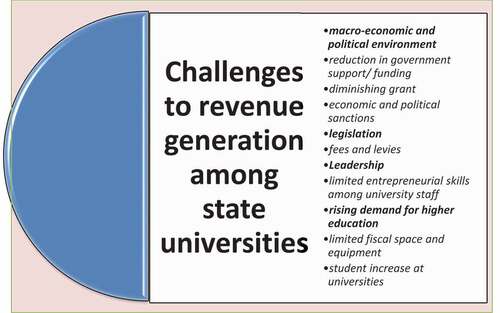

The discussion of the findings was done in line with the major research objective. The major and sub-themes that were yielded by the empirical study are summarised in fig 1 below:

The themes and sub-themes that were yielded by the empirical study as shown in Figure are macro-economic environment, current legislation on tuition fees, limited fiscal space and equipment, reduction in government support, rising demand for higher education, severe financial stringency, limited entrepreneurial skills among university staff and to some extent economic and political environment of Zimbabwe.

10.1. Theme 1: macro-economic and political environment

The study established that the government funding has been decreasing because of the macro-economic and politicalenvironmentwhichis affecting university operations. Other respondents who were interviewed reported that parents were failing to pay tuition for students while others argued that the economic sanctions levelled against Zimbabwe by the Western countries exacerbated the financial situation at state universities. One respondent, B1, posited that:

… the Zimbabwean economic and political environment isunpredictable, volatile, uncertain and complex. As a result, Zimbabwe has been experiencing serious economic, social and political challenges and the government has failed to live up to its responsibility of supporting universities fully from the fiscus (B1).

This was worsened by economic and political sanctions pencilled against Zimbabwe by Western countries, the land issue, political unrest and socio-economic instability (K. Chinyoka, Citation2013; Shizha & Kariwo, Citation2016). In line with the above, Zimbabwe’s economy remains in a fragile state, with an unsustainably high external debt and massive deindustrialisation and informalisation (Monyau & Bandara, Citation2014) affecting the effective running of state universities which depends largely on government grand and support. The government’s budgetary allocation to the higher education has been in drastic decline (Chetsanga, 2000). It should be noted that university education in Zimbabwe is greatly funded by the government. Public higher education systems in Zimbabwe are historically heavily dependent on the fiscus (80%) for their capital and recurrent expenditures (Madzimure, Citation2016). The same author alluded that only 15% funding comes from the fees and 5% from other sources.

Some participants blamed the issue of limited entrepreneurial skills among university staff and to some extent shortage of startup capital as barriers to revenue generation at state universities in Zimbabwe. Some participants, SUI, SU3, SU5, SU6, SU7 and SU10 suggested that severe financial stringency can also inhibit creative entrepreneurialism because many innovations require some initial investment and usually some financial risks that state universities that are severely short of money cannot afford to take. Any organisation with an assured income at a level that is adequate in relation to its needs and aspirations has little motivation to undertake risky innovations. The verbal quotes below illustrated the above sentiments:

Initial funding for high capital requirements may be a barrier to embark on some income generating projects such as mechanisation/modernisation of the university’s farming projects (SU3).

Universities are by nature knowledge producers not fundraisers. Staff earn enough, thus they are not interested in fundraising. Financial resources to start businesses are not enough. The eagerness is also not there (SU5).

Given the above sentiments raised by the participants, majority of the universities will continue to experience challenges in raising funds. The other barriers noted by participants include excessive expectation regarding remuneration of academic staff from block and part-time programmes and the silo mentality (negative attitude towards helping others, individualism, when people do not want to share information). B2 posited that:

Staff would rather moonlight and engage in part-time work at other institutions to get 100% of incremental income/revenue than do activities in-house and share the income with the University. There is also a culture of ‘ownership’ that results in pioneers of research and innovations holding on to their ideas rather than leveraging some of them in collaborative arrangements with partners possessing resources to unlock the ideas. In general, the ideas remain but the ‘ideas’ brilliant though they may be, are not converted into tangible outcomes (B2).

In line with the above argument, it can be argued that money is important, but while the need for resources often stimulate entrepreneurial knowledge transfer, extreme financial stringency is often seen as an inhibiting factor in that it makes it difficult to take risks and staff have to devote so much of their time to mainstream teaching that they have little energy for new initiatives (Mutambara & Chinyoka, Citation2016).

10.2. Theme 2: legislation/regulatory frameworks

Majority of the respondents of this study stated that the regulatory frameworks or laws in which state universities operate influence their revenue generation efforts. The participants agreed that the government can steer the behaviour of state universities towards certain goals through policies or laws and funding. One bursar, B2, purported that:

… Mandates are restrictive and the Ministry of higher and tertiary education exert pressure on institutions to focus on core business (teaching, researching and community service), thus commercial activities do not fit in this category (B2).

On the other hand, some respondents said that the current legislative environment allows innovation. This shows that there were mixed feelings on the challenges to revenue generation in a volatile economic environment in universities in Zimbabwe.

The other barrier noted by the participants, almost all of them are to do with the current tuition levels among Zimbabwean state universities which are very low ranging from 300 USD to 700 USD per semester with variations by faculty depending on whether they have practical’s and/or undertake industrial visits. Through interviews with all the 12 participants, it was established that the state universities cannot change tuition for conventional programmes.

Tuition levels are regulated by government with recommendations from the University’s Fees Revision Committee. 350-00 USD tuition fees at our university was dictated by the Government but levies per semester depend on the university (B2).

This was noted to be a serious barrier to financial sustainable development of state universities in Zimbabwe. Respondents agreed that only fees for block release programmes targeting employed people can be adjusted. It should be noted from the above argument that the fees charged by state universities to some extent are less than those of most boarding schools and even preschools. Because of the reductions in government financial support in Africa and the world over, universities are being pressured to raise tuition and student fees but this option is often resisted by governments for political reasons (Hanninen, Citation2013; Ozdil & Hoque, Citation2016; Reilly et al., Citation2016; World Bank, Citation2010; Zhou et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the economic challenges are affecting families’ ability to pay tuition at higher levels. In Uganda, the public universities have proposed fee increases as they have found it increasingly difficult to operate within existing budgets. The government of Uganda has had a similar response by stopping such increases at the public institutions (World Bank, Citation2010). Still, without other sources of income other than student fees, there is increasing pressure to raise tuition prices in countries like Zimbabwe.

Given the above, universities are not able to pursue additional revenue generation if the regulatory frameworks in which they operate do not allow them to do so (OECD, Citation2008; EUA, Citation2011). The regulatory frameworks often define the rules of the game by which various stakeholders interact and exchange resources (OECD, Citation2008). According to the World Bank (Citation2015) independently generated resources from universities contribute about 28% of the revenue of higher education. The share of own resources is lowest (5% or less) in Madagascar and Zimbabwe, and highest in Guinea-Bissau (75%). Generally, the pressure to achieve financial sustainability was strong across all universities in sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, Citation2010) and Zimbabwe is not an exception.

10.3. Theme 3: constraints of space and equipment/increased population

The study also noted some constraints of space and equipment, and the inhibitive cost structure of STEM programmes. The major limitation is that of matching students’ numbers to available resources. The study established that the current students’ population have increased over the past few years. At one university studied, students increased from 5500 in 2013 to 17,500 in 2017. Another respondent, SU3, also pointed out that the current students’ population is upwards of 16 000 up from 4 500 since only 6 years ago. Generally in the two universities studied, the numbers of the students are increasing. A possible reason mentioned by the participants was the contribution of the teacher Capacity programme which boosted Faculty of Science and Education enrolments. One respondent, SU8, said:

… Our university has capacity to enrol more in non-conventional classes and this significantly improves finances. The higher enrolments should also be supported by technologies and are delivered via virtual distant learning that is when significant income or revenue can be recorded (SU8).

Generally, majority of the participants purported that university facilities were also noted to be insufficient for engaging in revenue-generating activities. Tertiary education systems are continuously under pressure owing to the expansion of student population and the rising costs of teaching and research (World Bank, Citation2010). In agreement with the above, Madzimure (Citation2016) reported that the laboratories in most institutions are too few, poorly equipped and lack reagents to use. The computer/student ratio in most universities is pathetic and internet is unbearably slow.

Thus, the challenge for higher education in Zimbabwe is the ability to cope with the ever-increasing numbers of those potential students not absorbed in higher education institutions due to lack of funding. It should be noted from this study that underfunding from the government has resulted in archaic and primordial technological equipment in higher institutions of learning (Mutenda, 2012 & Garwe, Citation2014). Lack of hands-on skills has resulted in production of graduates who are ill-prepared for work in the industry (Chimbganda, Citation2014). Given the above, the higher enrolments should also be supported by technologies and adequate funding. As a result of the above, these researchers noted that staff is no longer motivated to be innovative and committed hence the need of this study to explore the challenges to revenue generation in order to come up with sound and sustainable strategies to generate funds for state universities.

10.4. Theme 4: leadership

The participants of this study also stressed that the university leadership becomes more important in revenue generation because they are mainly responsible for the development and implementation of strategies that help to reduce dependency relationships with the environment. The top management have certain powers/authority and autonomy by which they seek to produce and influence decisions on the university issues. Leadership cannot be restricted to a single post or even to a team or subset of colleagues in the centre, but it is rather dispersed around a university. At both the universities studied, participants emphasised the issue of corruption and in some instances the employment of unqualified personnel as serious drawbacks to revenue generation at state universities in Zimbabwe.

Financial unsustainability is thus a societal problem that must be addressed by the ecological approach consisting the microsystems of university departments including teaching and non-teaching staff, the neighbourhood, the mesosystems (linkages) and the ecosystems, as well as the macrosystem (government, political, ideology).

11. Conclusion

This study established that the macro-economic environment, current legislation on tuition fees, limited fiscal space and equipment, reduction in government support, rising demand for higher education, severe financial stringency, limited entrepreneurial skills among university staff. To some extent, economic and political environment were noted to be the greatest push for revenue diversifications and finally government’s failure to fund for capex and operations as barriers to revenue generation among state universities in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwean universities have been greatly affected by the economic challenges facing the country. Thus, government is failing to meet its obligation in supporting Higher Education.

12. Recommendations

Basing on the findings of this study, the following recommendations were suggested:

There is dire need for the universities to be allowed to determine their own tuition fees. Government should also reduce bureaucracy and red tape, incentivising those who attract/raise revenue at state universities. Also, there should be the possibility of providing small loans (micro-credit) to the lagging universities, which may help them to establish their own businesses to become self-sustained.

Last but not least, universities must be given increased autonomy to be able to react quickly to economic and political situations. This will enable higher education institutions to grab opportunities as soon as they arise and arrest threats before they cause damages.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrias Chinyoka

Andrias Chinyoka completed his PHD studies at the University of KwaZulu Natal in 2020, holds a Masters Degree in Business Management, and a Bachelor’s degree in Accounting from the University of Zimbabwe. He is currently employed as a Finance Director at Great Zimbabwe University. My research interests are in the areas of public sector management, public sector financing and Accounting.

Emmanuel Mutambara

Emmanuel Mutambara is a Senior Lecturer at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. He holds a Doctoral Degree in Business Administration attained from North-West University, South Africa in 2014, a Masters Degree from the Zimbabwe Open University in 2006. Currently Dr Mutambara is serving as the Academic Leader Research and Higher Degrees at the university’s Graduate School of Business and Leadership. He has successfully supervised several Masters Dissertations and in excess of 12 Doctoral Thesis. His research interests are in the areas of leadership within the public sector, organisational behaviour, and business management.

References

- Chimbganda, T. (2014). An investigation into strategies that can be adopted to improve the productivity of small scale gold miners in Mutare River (2010-2013). http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/zimsit_my-zimbabwean-pain-prof-ambrose

- Chinaka, C. (2009). Zimbabwe orders school fee cuts as economy struggles. Swissinfo.ch. Retrieved May 27, 2009, from http://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/news/international/Zimbabwe_orders_scho

- Chinyoka, A. (2018). Sustainable survival strategies in a volatile economic environment: A case of Zimbabwean universities. In African universities house trinity. 152–10. ISBN: 978-9988-2-7268-5. Accra, Ghana: Association of African Universities.

- Chinyoka, K. (2013). Psychosocial effects of poverty on the academic performance of the girl child in Zimbabwe. Doctoral thesis published online http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/13066/thesis_chinyokai_k.pdf%3Fsequence%3D1

- Chombo, I. (2010, November). Higher education and technology in Zimbabwe: Meaningful development in the New Millennium. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 12(3), 2000. -1013-3445 http://masseducation.com

- Clark, B. R. (2004). Sustaining change in Universities: Continuities in case studies and concepts. SRHE/OUP.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- EUA. (2010). Financially sustainable universities. Towards full costing in European Universities. annual report. European University Associations.

- EUA. (2012). Financially sustainable universities II: European universities diversifying income streams. FiveTraditions. Sage.

- EUA. (2015). Financially sustainable universities. Towards full costing in European universities.

- EUA. (2011). Financially sustainable universities towards full costing in european universities. Thomas Estermann and Enora Bennetot Pruvot. Brussels.

- Gandawa, J. (2016). Zimbabwe education system: A survival of the fittest. http://nehandaradio.com/2016/10/04/zimbabwean-university-education-system-

- Garwe, C. (2014). Quality assurance challenges and opportunities faced by private Universities in Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education.

- Gebreyes. (2015). Revenue Generation strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa. CHEPS/UT, P.O. Box 217, NL-7500 AE Enschede, the Netherlands.

- Gibran, J. M., & Sekwat, A. (2009). Continuing the search for a theory of public budgeting. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 21(4), 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-21-04-2009-B005

- Global Education Digest. (2003). Comparing education statistics across the world. UNESCO Institute for Statistics Montreal: UIS.

- Gono, G. (2015). Zimbabwe’s casino economy, extraordinary measures for extraordinary challenges. ZPH Publishers.

- Hanninen, V., (2013). Budgeting at a crossroads – the viability of traditional budgeting – a case study. Master’s thesis, Aalto University School of Business.

- Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. B. (2014). Educational research: quantitative, qualitative and mixed approaches (5th ed.). Alabama: SAGE Publications.

- Kapungu, R. S. (2007). The pursuit of higher education in Zimbabwe: A futile effort. In A Paper Prepared for the Centre for International Essay Competition on Educational Reform and Employment Opportunities (pp. 2007). CIPE.

- Kariwo, M. T. (2007). Widening access in higher education in Zimbabwe. Higher Education Policy, 20(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300142

- Kvale, S. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. SAGE Publications.

- Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2005). Practical research: Planning and design (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Madzimure, J. (2016). Zimbabwe education system: A survival of the fittest. http://nehandaradio.com/2016/10/04/zimbabwean-university-education-system-

- Majoni, C. (2014). Challenges facing university education in Zimbabwe. Greener Journal of Education and Training Studies, 2(1), 020–024. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJETS.2014.1.021714111

- Makoni, S. (2012). Government of National Unity not for people, Zimbabwe Mail, 6 February, 2012

- Manayiti, O., Nyoni, M., & Dube, B. (2015). Massive zim job losses in wake of court ruling. Mail and Guardian. Retrieved from http://mg.co.za/article/2015-08-06-massive-zim-job-losses-in-wake-ofcourt-ruling/

- Monyau, M. M., & Bandara, A. (2014). Zimbabwe 2014: Africa economic outlook; AfDB, OECD, & UNDP. www.africaneconomicoutlook.org.

- Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R., Sampat, B. N., & Ziedonis, A. A. (2004). Ivory tower and industrial innovation. University-industry technology transfer before and after the Bayh-Dole act in the United States. Stanford University.

- Mufudza, T., Jengata, M., & Hove, P. (2013). The usefulness of strategic planning in a turbulent economic environment: A case of Zimbabwe during the period 2007-2009. Business Strategy Series, 14(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/17515631311295686

- Mutambara, E., & Chinyoka, A. (2016). The budgetary process for effective performance of universities in a resource stricken economy: A conceptual framework. Journal of Accounting and Finance, 6(2), 96–112.

- Nherera, C. (2000). The role of emerging universities. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 12(12), 1013–3445.

- Nyamwanza, T. (2014). Strategy Implementation for survival and growth among small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Zimbabwe. Doctoral thesis, Midlands state university.

- OECD. (2008). Tertiary education for the knowledge society. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Ozdil, E., & Hoque, Z. (2016). Budgetary change at a university: A narrative inquiry. The British Accounting Review, 48–65.

- Patton, M. Q. (2012). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (7th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Pellissier, R. (2007). Business research made easy. Juta.

- Reilly, G., Souder, D., & Ranucci, R. (2016). Time horizon of investments in the resource allocation process review and framework for next steps. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316630381

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2010). Research methods for business students (5th ed.). Pearson.

- Shizha, E., & Kariwo, T.(2016). Education and development in Zimbabwe: A social, political and economic analysis. Retrieved 12 May 2016 from http://www.sensepublishers. com/ … /297-education-and-developmentin-Zimbabwe.

- White, C. J. (2012). Research methods and techniques. Harper Collins College.

- World Bank. (2010). Higher education in developing countries: Peril and promise. The task force on higher education and society.

- World Bank. (2013). Constructing knowledge societies: New challenges for tertiary education.

- World Bank. (2015). Financing higher education in Africa.

- Yin, R. K. (2012). Case study research: Design and methods (7th ed.). SAGE Publication.

- Zhao, W., & Zou, Y. (2015). Green university initiatives in china: a case of tsinghua universitynull. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 16(4), 491–506.

- Zhou, G., Mukonza, R. M., & Zvoushe, H. (2016). Public budgeting in Zimbabwe: Trends, processes, and practices. Public Budgeting in African Nations: Fiscal Analysis in Development Management, 134–156.