?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines fashion clothing involvement among gay men, who are an emerging segment in the fashion industry. Data was gathered via an online self-administered survey, resulting in 150 responses. SEM using the Smart PLS software, version 3, was used to test the hypotheses. The findings uncovered that fashion consciousness and consumer conformity significantly influence fashion clothing involvement, while social comparison, purchase involvement and social consciousness insignificantly influence fashion clothing involvement. In addition, the results revealed that fashion clothing involvement influences both consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership. Fashion clothing involvement proved to be a positive and a significant mediator between fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement, social consciousness, consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership. This study stands to add new knowledge to the present body of fashion clothing involvement and consumer behaviour literature in Africa—a context that is often ignored by academics in developing countries.

Jel classification:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The need to understand consumers’ behaviour and decision-making when buying clothes is increasingly becoming important. This research, therefore, looks at how gay consumers’ make purchasing decisions when it comes to fashion. Marketers have begun to take interest in this consumer cohort and exploring this cohort from a South African viewpoint provides an interesting under-researched perspective. Not much is known about this cohort’s buying behaviour from a South African perspective and this research is an attempt to understand their fashion clothing involvement.

1. Introduction

The global clothing market is valued at 3 USD trillion dollars, accounting for 2% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (Kumar, Citation2018). With the growing disposable consumer income, there has been a growing demand for fashion clothing among consumers worldwide (Molla-Descals et al., Citation2012). The term “fashion” is difficult to define; however, it generally refers to trending clothing. Fashion is a form of art dedicated to the design of clothing and other trending lifestyle accessories and is divided into two broad categories: haute couture and ready-to-wear (Fibre2Fashion.Com, Citation2018). Haute couture is defined as a collection devoted to particular customers and customised to the exact specifications of the customer (Gilvin, Citation2014). On the other hand, ready-to-wear collections are not customised to individual specifications and they tend to be standardised and appropriate for mass production (Fibre2Fashion.Com, Citation2018).

Some distinctive behavioural tendencies appear to differentiate gay consumers from heterosexual male consumers (Aung & Sha, Citation2016). One of these tendencies relates to how gay men place more importance on their physical appearance and their investment into appearance (Amoha, Citation2017), and generally spend a significant amount of their time on fashion clothing compared to heterosexual consumers (Sha et al., Citation2007). Gay men tend to have an outstanding knowledge of fashion and the fashion industry, compared to their heterosexual counterparts. As such, Chen et al. (Citation2004) indicate that gay men spend a significant portion of their income on fashion clothing. In addition, gay men are considered trendsetters in the fashion industry (Rudd, Citation1996).

The annual spending power of the global gay community is 3.7 USD trillion (Pride World Media, Citation2018). Furthermore, the gay fashion market is worth 150 USD billion worldwide (Kumar, Citation2018). Compared to heterosexual consumers, gay consumers have established a reputation of being classy and fashionable. They not only utilise fashion clothing for self-identity, but they also express their appreciation of appearance and fashion (Amoha, Citation2017). Within the gay community, consumption reflects identity, belonging and subcultural assimilation (Strubel & Petrie, Citation2018). Moreover, the study conducted by Kates (Citation2002) revealed that fashion clothing provides a safe space for gay men living within the mainstream community and it is used to signify their affiliation. The ideal gay identity is associated with high-quality fashion, a unique appearance, and high status. In most advertisements and movies, the gay characters are often portrayed as educated, wealthy and successful, with the financial means to afford expensive fashion clothing and other commodities.

Gay men tend to possess an above-average education standard, and they are brand- and fashion-conscious and affluent, with a high disposable income (Schwartz, Citation1992). According to Schofield and Schmidt (Citation2005) gay men have enormous potential as a focal point for marketers. As the gay lifestyle has gained acceptance in South Africa, businesses are acknowledging the need to modify their marketing activities to align with this consumer segment (Strubel & Petrie, Citation2018).

Despite fashion clothing exemplifying an important dimension of modern gay male culture and representing a growing market (Hattingh et al., Citation2011), very little academic research exists that could help marketers and fashion retail in understanding factors influencing the involvement of gay men in the fashion clothing sector. Furthermore, Noh et al. (Citation2015) argue that the involvement of gay men in fashion clothing has been overlooked.

The available literature on fashion clothing involvement includes:

O’Cass (Citation2004), who studied the fashion clothing consumption of Australians;

Khare et al. (Citation2012), who studied the influence of collective self-esteem on fashion clothing involvement among Indian women;

McNeill and McKay (Citation2016), who studied fashion masculinity among young New Zealand men, and

Bhaduri and Stanforth (Citation2017), who studied the effects of fashion clothing involvement on customer value among female consumers in the United States.

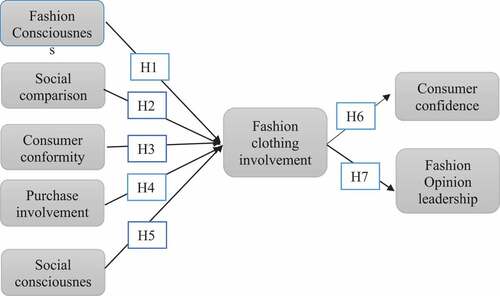

Deriving from the aforementioned studies, gay consumers are still an underrepresented consumer segment and are underrepresented in research, particularly in the area of consumer studies. Studying this niche market is very crucial for marketers. It would be naïve to assume a priori that findings from developed countries in Europe or from the USA, or even from the newly developed countries in Asia, apply in Africa. Perhaps, research which examines fashion clothing involvement among gay men, in the African context might yield different results from other parts of the world. Thus, in order to confirm or disconfirm the findings of previous studies, this kind of research related to fashion clothing involvement among gay men in Africa is evidently long overdue. Hence, what this current investigation examines, by means of a proposed conceptual model, is the effect that fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement, and social consciousness have on fashion clothing involvement. Furthermore, the conceptual model also seeks to determine if fashion clothing involvement would influence consumer confidence and opinion leadership. Moreover, to the best knowledge of the researchers, it can be noted that the conceptual model is one of a kind, as no previous study has tested the variables in the proposed model in relation to the South African context.

This paper is organized as follows: firstly, empirical literature and the formation of the hypothesis is presented. The research design and methodology are then presented, followed by a presentation of the results, and the discussions. The final sections of the article discuss the implications, limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

After a search on academic online databases and search engines, this section reviews the literature around the variables of this research. Moreover, the hypothesized connections between the study variables are discussed in the subsequent sections based on past studies and logically deriving from prior results.

2.1. Fashion clothing involvement

O’Cass (Citation2000) describes involvement as the extent to which consumers observe something as an essential part of their life. This led Kim et al. (Citation2018) to conclude that involvement shows the tendency of a person to pay more attention to specific products or to participate actively in specific product acquisition activities. Involvement influences the buying behavior of the consumer (Khare, Citation2015). Therefore, there is a difference between consumers who are highly involved and those who are less involved (Hourigan & Bougoure, Citation2012). Rahman et al. (Citation2018) assert that highly involved consumers are most likely to purchase fashion clothes than less involved consumers. Furthermore, consumers who are highly involved with clothing products often purchase products before others and encourage others to buy them as well (McFatter, Citation2005). Likewise, they do not mind paying a premium price for products and spend a larger quantity of their time shopping.

Highly fashion-involved consumers are regarded as the drivers of the fashion adoption process and are an important segment for fashion retailers and marketers (Madinga, Citation2016). Highly fashion-involved consumers gather fashion information before others and share with their social groups, making them opinion leaders (Hourigan & Bougoure, Citation2012). Therefore, consumers who are highly involved prefer doing extensive research before making decisions concerning fashion clothing, as they feel that fashion is personally relevant (Jordaan & Simpson, Citation2006). On the other hand, less involved consumers usually do not conduct any research before making purchase decisions (Josiassen, Citation2010). Moreover, less fashion-involved consumers tend to buy fashion clothes on sale (Miquel et al., Citation2002).

Fashion clothing involvement is a rapid growing research focus as it is associated with how important and meaningful clothes are to the lives of individuals (Hourigan & Bougoure, Citation2012). O’Cass (Citation2004, p. 870) define fashion-clothing involvement as the extent to which individuals view the related fashion clothing as an important part of their lives.

2.2. Antecedents of fashion clothing involvement

2.2.1. Fashion consciousness

The fashion industry is very dynamic and fast-paced (Kim et al., Citation2018). Therefore, people often re-evaluate themselves and the significance attached to different styles that are adopted to stay current (Lertwannawit & Mandhachitara, Citation2012). Motale et al. (Citation2014, p. 121) define fashion consciousness as “a person’s degree of interest in the styles or fashion of clothing”. Fashion-conscious consumers tend to pay more attention to the latest fashion styles so they can stay updated and adopt new fashion trends or catch up with their peers’ changing identities (Lertwannawit & Mandhachitara, Citation2012) and maintain their social network (Soh et al., Citation2017). A study conducted by Vieira et al. (Citation2008), studied fashion clothing involvement. The results indicated that fashion-conscious consumers tend to be highly fashion involved. In addition, Chui et al. (Citation2017) studied fashion involvement and its implications among Malaysian Generation Y consumers. The authors concluded that fashion consciousness is a driver of fashion clothing involvement. A study on fashion consciousness showed that gay men respondents were more fashion-conscious than their counterparts (Sha et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, studies claim that gay men spend a significant amount of their time and money on fashion clothing. The study conducted by Braun et al. (Citation2015) revealed that gay men believe they have higher fashion interest than their heterosexual counterparts. Additionally, researchers argue that gay men tend to prefer trendy styles (Braun et al., Citation2015; Schofield & Schmidt, Citation2005). The aforementioned information led to the following hypothesis:

H1: Fashion consciousness has a positive influence on fashion clothing involvement among gay men.

2.2.2. Social comparison

It is natural for people to compare themselves to others. Social comparison is an important feature of social life (Liu et al., Citation2019). This social comparison occurs in several contexts, such as health, work, and marriage (Vogel et al., Citation2014). Originally proposed by Festinger (Citation1954), social comparison theory suggests that people make comparisons to others to evaluate their own opinions, capabilities, and performance, especially in uncertain situations. For example, Foddy and Crundall (Citation1993) found that when students had received their graded assignments, about half were interested in social comparison information (i.e. how they fared compared to other students) even when they already had objective information (i.e. a grade of 90%). In addition, social comparison helps individuals understand their capabilities better (Festinger, Citation1954). Buunk and Gibbons (Citation2007) argue that individuals tend to select people who have similar or related attributes to compare themselves to. “Social comparison affects individual behavior and guides what an individual can do and feels obligated to do, so it can simply explain the interpersonal influence of a social group” (Islam et al., Citation2018, p. 20). According to Liu et al. (Citation2019), there are two types of social comparison: upward social comparison and downward social comparison. “Upward social comparison occurs when comparing with someone who is considered socially superior in some way, whereas downward comparison occurs when individuals compare themselves with someone who is deemed socially worse off than they are” (Liu et al., Citation2019, p. 134). Social comparison satisfies the individuals’ self-enhancement motive (Suls et al., Citation2002), and enhances their self-esteem (Vogel et al., Citation2014).

Research consistently demonstrates that social comparison leads to fashion clothing involvement (Powell et al., Citation2018; Tiggemann & Brown, Citation2018). In addition, it has been established as a predictor of fashion clothing involvement. This is particularly true for gay men. Gay men use clothing and adornment to create a sense of group identity (separate from the dominant culture) to resist and challenge normative (gendered) expectations, and to signal their sexual identity to the wider world or just to those they know‟ (Rothblum, Citation1994; Taub, Citation2003). In addition, Hobza et al. (Citation2007), assert that gay men feel pressured to conform to the standards set by their counterparts. For instance, in a qualitative study conducted by Clarke and Turner (Citation2007), one participant indicated that gay men place a particular premium on dress, appearance, style and fashion (and making judgements about people on the basis of their clothes and appearance). Along with what the previous literature suggests, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H2: Social comparison has a positive influence on fashion clothing involvement among gay men.

2.2.3. Consumer conformity

According to Madinga (Citation2016, p. 18), consumer conformity is defined as the “behavior of individuals purchasing products/or services due to interpersonal influence, so that a specific social group can accept them, particularly people around them”. In social psychology theory, people are regarded as social creatures who are more likely to conform to social norms and whose behavior is strongly influenced by their group association (Kotler, Citation1965, p. 42). Consequently, it is normal for individuals to own certain products because of group association (Grubb & Stern, Citation1971). Generally, once individuals perceive themselves as part of a group, they tend to derive self-esteem from that group attachment and embrace behaviors that are consistent with the stereotypes related to their group identity (Madinga, Citation2016). According to Forehand and Deshpande (Citation2001), group conformity determines what types of products and brands individuals purchase. The study conducted by Aaker et al. (Citation2001) revealed that consumer choices for items such as cars, food and fashion clothing are heavily influenced by consumer conformity. Christopher et al. (Citation2014) emphasise that consumers often gather information about fashion clothing brands to avoid social disapproval. Recently, the study conducted by Sun and Guo (Citation2017) on predictors of fashion involvement by media use, social influence and lifestyle found a strong relationship between fashion involvement and social influence. The above argument led to the following hypothesis:

H3: Consumer conformity has a positive influence on fashion clothing involvement among gay men.

2.2.4. Purchase involvement

Involvement is an imperative feature of clothing associated purchases, owing to fashion’s central role in society and the significance placed on clothing by consumers (Michaelidou & Dibb, Citation2006). Within the existing literature, involvement has been found to lead to greater involvement in the purchase decision itself (Hourigan & Bougoure, Citation2012). Purchase involvement is motivated by consumers’ belief that a product is an extension of their personal identity and used to maintain or enhance their self-concept (Kim, Citation2005; Solomon & Rabolt, Citation2004). Therefore, products that enhance individuals’ physiques and appearance—such as apparel and grooming-related products—are considered to be high-involvement products because they directly affect consumers’ self-image, making them feel positive about themselves, and helping them project an image to others that reflects what they aspire to be (Kim, Citation2005).

The study conducted by Hourigan and Bougoure (Citation2012) found that purchase involvement influences fashion clothing involvement. The authors argued that an individual who is highly involved in fashion clothing tends to spend a significant portion of their time with the product category and be more involved in the processes associated with making purchase decisions about fashion clothing. In addition, Khan (Citation2013) established a relationship between purchase involvement and fashion clothing involvement. Involvement among consumers is also likely to vary with the desire of consumers to use clothing as a means to enhance their self-images and to engage in self-expression and pleasure through selection (Michaelidou & Dibb, Citation2006).

As stated earlier, gay men place more importance on their physique, invest in their appearance (Amoha, Citation2017), and generally spend a significant amount of their time on fashion clothing shopping compared to heterosexual consumers (Sha et al., Citation2007). The above background led to the following hypothesis:

H4: Purchase involvement has a positive influence on fashion clothing involvement among gay men.

2.2.5. Social consciousness

Social consciousness can be defined as the consciousness common within a society regarding social situations (Cooley, Citation1992). According to Fu and Liang (Citation2018), social consciousness is also known as social awareness. Nielsen’s survey started by confirming what other studies have suggested—that the majority of consumers today express a general preference for companies making a positive difference in the world. Furthermore, 66% of consumers around the world say they prefer to buy products and services from companies that have implemented programmes to give back to society (Nielsen Report, Citation2012). Consumers’ awareness of social issues has a direct impact on their purchase decision. According to Gilliland (Citation2017), gay consumers have a strong preference for fashion brands that support causes important to them. In addition, Radin (Citation2019) argues that gay consumers tend to purchase fashion clothing from fashion brands that support Pride Month. Accordingly, this reflects socially responsible behaviour. Fashion clothing brands have started producing eco-friendly designs to target social consciousness (Gilliland, Citation2017). As a result, fashion brands are now incorporating the term “eco-friendly” in their marketing messages, with the aim of offering “design-forward, cutting-edge fashion” that also has a positive social impact. Therefore, this suggests the following hypothesis:

H5: Social consciousness has a significant positive impact on fashion clothing involvement among gay men.

2.3. Consequences of fashion clothing involvement

2.3.1. Consumer confidence/self-esteem

Clothes play an important role in the enhancement of self. Keogan (Citation2013) argues that clothes also create a feeling of self-acceptance. Keogan (Citation2013, p. 10) found that “positive feelings about one’s clothing enhances self-perception of emotions; sociability and occupational competency”. Ferguson (Citation2016) asserts that the clothes individuals select reflect and have an impact on their mood, heath and confidence. In 2014, car manufacturer, Kia, conducted a survey focusing on what makes individuals confident for the introduction of their Kia Soul model. They found that fashion clothing was one of the top items that makes people gain confidence (O’Callaghan, Citation2014). Clothing may serve as an adaptive function for individuals with lower self-esteem and as an expressive function for those with higher self-esteem. An experimental study conducted by Joung and Miller (Citation2006) on how dresses affect the self-esteem of elderly women in nursing homes, found that elderly women consistently reported feeling more confident when they felt they were dressed nicer than normal. In addition, Khare et al. (Citation2012), found that prestigious fashion clothing increases Indian women’s self-esteem and social status. A survey of over 600 gay men aimed at exploring depression and mental health issues in the gay community found that 24% of gay men admitted to trying to kill themselves, while 54% admitted to having suicidal thoughts. A further 70% said low self-esteem was the main reason for their depression and suicidal thoughts (Williams, Citation2015). According to Angelo (Citation2019), gay men can build self-esteem by wearing fashion clothing. He further argues that “although clothes don’t make the man, they certainly affect the way he feels about himself”. O’Callaghan (Citation2014) emphasises that fashion has a significant effect on self-esteem. The above background led to the following hypothesis:

H6: Fashion clothing has a significant positive effect on consumers’ self-esteem.

2.3.2. Fashion opinion leadership

Schiffman et al. (Citation2010, p. 282) define opinion leadership as “the process by which one person (the opinion leader) informally influences the actions or attitudes of others, who may be opinion seekers or opinion recipients.” Opinion leaders tend to be product experts, who tend to provide information to other consumers who are not familiar with a particular product (Jin & Ryu, Citation2019). Therefore, these consumers are important to marketing practitioners’ and brands (Jordaan & Simpson, Citation2006). According to Bertrandias and Goldsmith (Citation2006), fashion opinion leaders are a crucial example of opinion leaders. “Fashion leaders have traits such as an interest in fashion. They are high in fashion involvement, and participate in activities (e.g., read fashion magazines, go shopping for clothing) that provide abundant information” (Lee & Workman, Citation2014, p. 455). Furthermore, Workman and Cho (Citation2012) states that fashion leaders often engage in recreational shopping, purchase the latest fashion items and tend to be impulsive buyers of fashion clothing. All these activities offer a wealth of fashion information that fashion leaders could share with others (Lee & Workman, Citation2014). Gay men tend to be fashion opinion leaders. Furthermore, the “New Times” (Citation2010) states that the top fashion names in the industry such as Valentino, David Tlale, Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce are gay men. The study conducted by Vanska (Citation2014) revealed that fashion opinion leaders tend to be sensitive to their friends and family’s’ appearance due to their involvement in fashion. Gay fashion leaders often convey information about fashion to their friends and help others evaluate whether the clothes style is appropriate or not (Amoha, Citation2017). Gay men fashion leaders play an important role in persuading other consumers (Sha et al., Citation2007). This suggests the following hypotheses:

H7: Fashion clothing involvement has a significant positive effect on fashion opinion leadership among gay consumers.

2.3.3. Conceptual model

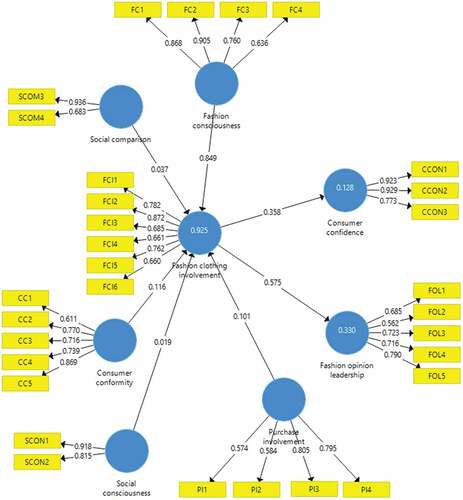

Drawing on the above, the study’s research model was developed (Figure ). The theoretical model illustrates the suggested interconnection of eight constructs, namely, fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement, social consciousness, fashion clothing involvement, consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership. The relationships between the proposed constructs in the theoretical model are as follows: fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement and social consciousness provide the starting point of the model and directly affect fashion clothing involvement which in turn induces consumer confidence and opinion leadership.

2.4. Mediation hypothesis statements

Apart from the posited relationships depicted in conceptual model 1 (Figure ), direct and indirect relationships between the variables under investigation are plausible. Alternative hypothesis statements that incorporate fashion clothing involvement as a mediating variable were also incorporated in this study. It is imperative to provide empirical evidence that shows fashion clothing involvement as a mediating variable between fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement, social consciousness, consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership. However, it is important to note that there are deficiencies in empirical studies that are centred on fashion clothing involvement as a mediating variable. Nevertheless, there are closely related studies such as the one conducted by Venter et al. (Citation2016) who investigated factors influencing fashion adoption among the youth in Johannesburg, South Africa and O’Cass and Choy (Citation2008) who examined Chinese generation Y consumers’ involvement in fashion clothing and perceived brand status. In addition, Vieira (Citation2009) measured the extent to fashion clothing involvement mediated the relationship between predictor variables (materialism, age and gender) and outcome variables (confidence, knowledge and patronage). Based on this premise, the mediating impact of fashion clothing involvement still needs further clarification as there is still limited empirical research in the literature. It is expected that fashion clothing involvement can be a mechanism through which fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement and social consciousness can positively impact consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership. This is one of the important empirical contributions of this study because it offers a more nuanced explanation of the essence of fashion clothing involvement as a mediator variable. Due to limited availability of clear empirically demonstrated findings, it is considered appropriate to propose the following hypotheses:

H8: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between fashion consciousness and consumer confidence

H9: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social comparison and consumer confidence

H10: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between consumer conformity and consumer confidence

H11: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between purchase involvement and consumer confidence

H12: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social consciousness and consumer confidence

H13: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between fashion consciousness and fashion opinion leadership

H14: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social comparison and fashion opinion leadership

H15: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between consumer conformity and fashion opinion leadership

H16: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between purchase involvement and fashion opinion leadership

H17: Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social consciousness and fashion opinion leadership

3. Methodological aspects

From the ontological perspective of objectivism of the research, this investigation pursues a positivistic framework as it seeks to discover a link between the variables presented for this analysis and uses measurement instruments for gathering data. Hence, a quantitative approach has been applied as it improves the accuracy of findings by means of statistical analysis. The design was suitable to solicit the required information relating to fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement, social consciousness, fashion clothing involvement, consumer confidence and opinion leadership. The motivation for following a quantitative approach was in the thoroughness and bias-free nature with which the methodology is applied (Malhotra, Citation2010).

3.1. Data collection and sampling

In South Africa, the LGBTQAI+ community is still experiencing institutionalised prejudice, social exclusion, hatred and violence (Nduna et al., Citation2017). Although approximately 10% of the South African population is openly gay. Therefore, homosexuality is a sensitive issue in South Africa. Due to the sensitivity of the current study, the researchers designed a web-based self-completion questionnaire using Survey Monkey. The researchers posted the link of the questionnaire on several online social networks, like Facebook and Twitter. The respondents are more likely to open up to a computer-based survey than they would in a face-to-face environment. In addition, Yun and Trumbo (Citation2000) argue that web-based surveys collect data quickly and are advisable when resources are limited. Survey Monkey automatically records and analyses data (Giovannini et al., Citation2015). Data collection took place over a period of three months—from March to May 2017. A total of 183 respondents contributed to the research and completed the survey. The survey contained close-ended questions about the various items in the constructs. In total, 150 responses were deemed complete and suitable to be included in the final analysis. The following section discusses how the measurement instrument was developed.

3.2. Measuring instrument

The measurement instrument of this study was developed using modified items from previous literature on fashion studies:

constructs for fashion clothing involvement were adopted from O’Cass (Citation2004)

fashion consciousness from O’Cass et al. (Citation2013) and Walsh et al. (Citation2001),

social comparison from Bai et al. (Citation2013)

consumer conformity from Shin and Dickerson (Citation1999)

purchase involvement from O’Cass (Citation2000)

social consciousness from Ladhari et al. (Citation2019)

consumer confidence from O’Cass (Citation2000)

opinion leadership from Goldsmith et al. (Citation1993)

The scale indicators were affixed to a strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) Likert-scale continuum.

3.3. Ethical considerations

This research study acted in accordance with the ethical standards of academic research, which among other things is protecting the identities and interest of respondents and assuring confidentiality of information provided by the participants. Respondents gave their informed consent to this research and were informed beforehand about the reason and the nature of the investigation to ensure that participants were not misled. Despite all the above-mentioned precautions, it was made clear to the participants that the research was only for academic research purpose and their participation in it was voluntary. No one was forced to participate.

3.4. Demographic profile of the respondents

Table represents a description of the participants. The respondents were asked to report on their demographic information, including age, highest level of education, ethnic group, marital status and monthly income.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the respondents

4. Results and discussion

A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used to capture data and to examine the data received. The Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) and the Smart PLS software for Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) strategy were used to code information and to run the results. According to Chin (Citation2010), SEM is also well known for being a statistical technique that combines numerous research procedures. It is also known for making use of different approaches, such as latent variable analysis, covariance-based analysis and variance-based SEM (PLS path analysis). PLS-SEM have been used in behavioral studies (Henseler & Chin, Citation2010; Sarstedt, Citation2008). PLS-SEM allows for a better understanding of the relationship (Hair et al., Citation2012; Henseler et al., Citation2009; Rigdon et al., Citation2010). Smart PLS is an effective way to deal with straightforward models. As indicated by Hsia and Tseng (Citation2015), PLS is more suitable to investigate areas where hypotheses are not created, as required by LISREL. Also, Smart PLS bolsters both exploratory and corroborative research, is strong on deviations for multivariate ordinary dispersions, and is useful for small samples (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2013). Since the present investigation test estimate is moderately small (150), Smart PLS was more suitable and befitting the reason for the present examination.

4.1. Testing for mediation

Ramayah et al. (Citation2011) are of the view that a mediation test is conducted to discover if a mediator construct can significantly carry the ability of an independent variable to a dependent variable. According to Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004), researchers often conduct mediation analysis to indirectly assess the effect of a proposed cause on some outcome through a proposed mediator. The utility of mediation analysis stems from its ability to go beyond the merely descriptive to a more functional understanding of the relationships among variables (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2004). The conceptual model of this study comprises five independent variables, fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, purchase involvement, social consciousness and consumer confidence; one mediating variable, fashion clothing involvement, and two dependent variables, consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership. Bao et al. (Citation2011) adopted Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) suggested procedure, which consists of four main steps. The first step is to determine the significance of the relationship between the independent and the dependent variables, without the mediator. Figure reveals step 1 in Baron and Kenny’s approach for testing mediation.

The second step comprises determining the relationship between the independent variable and the mediator. Figure shows step 2 in Baron and Kenny’s approach for testing mediation.

The third step is centred on testing if the mediator has a significant unique effect on the dependent variable. Figure displays step 3 in Baron and Kenny’s approach for testing mediation.

The final step is to calculate the full model and identify if the previous significant relationship between the independent and dependent variable is zero (i.e. full mediation) or reduced (i.e. partial mediation) (Bao et al., Citation2011). Figure presents step 4 in Baron and Kenny’s approach for testing mediation.

Although Baron and Kenny’s approach shows the traditional testing steps for mediation, Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004, p. 2008) have criticised the ”causal procedure” of Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) by introducing a new method called “bootstrapping the indirect effect”. This current testing procedure for mediation is said to be perfectly suited for PLS-SEM which is a common technique to test structural models using the component-based approach (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, this study utilised Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM) technique, to test the mediating effect of the mediator of this study, namely competitive advantage. PLS path analysis allows evaluating mediation models and tests mediation hypotheses, using the bootstrapping method (Hayes et al., Citation2011; Hernández-Perlines et al., Citation2016). Bootstrapping, a nonparametric resampling procedure has been recognised as one of the more rigorous and powerful methods for testing the mediating effect (Hayes, Citation2009; Shrout & Bolger, Citation2002; Zhao et al., Citation2010). The application of bootstrapping for mediation analysis has recently been advocated by J. F. Hair et al. (Citation2017) who noted that when testing mediating effects, researchers should rather follow Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004) and bootstrap the sampling distribution of the indirect effect, which works for simple and multiple mediator models”. It is important to note that the bootstrapping procedure was used when conducting an estimation of indirect effect ab, standard error and both indirect effects interval at 95% confidence interval.

4.2. Reliability and validity analysis

The statistical measures of accuracy tests that appear in Table indicate the distinct measures that were utilised to survey the reliability and validity of the constructs for the investigation. Accurately, the table delineates means and standard deviations, Item to Total connections, Cronbach alpha values, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR) and Factor Loadings.

Table 2. Accuracy Analysis Statistics

4.3. Measurement model assessment

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed and the SEM was estimated by using PLS data. Table and Figure depict the CFA findings, whereas Table and Figure summarise the SEM finding. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the measurement model, representing the outer model in PLS. Mashapa et al. (Citation2019, p. 588) mentioned that the “purpose of the measurement model is to evaluate the reliability and validity of variables”. Table shows that the item-total correlation value lies between 0.531 and 0.794, which is above the cut-off point of 0.5—as recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988). The higher inter-item correlations reveal convergence among the measured items. Nunnally and Bernstein (Citation1994, p. 1) explained that “alpha values should exceed 0.6”. All variables in this study represented good reliability, with the Cronbach’s alpha between 0.601 and 0.856. The study also used CR values in testing the reliability of the seven research constructs. The CR values varied between 0.788 and 0.909. The obtained values from CR were above the acceptable reliability score of 0.7, thus validating the internal consistency of the seven research construct measures (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). The result shows that the AVE of this study was between 0.487 and 0.771. These AVE values were above the recommended 0.40, indicating a satisfactory measure (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). As shown in Table , loadings of all items are more than the suggested value of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2009). Factor loadings in this study ranged between 0.562 and 0.936. Item SCOM1 and SCOM2 were deleted because of the low factor loadings which were below 0.5. The remaining items fulfilled the requirement of reliability and convergent validity. Table presents the discriminant validity analysis results for the study. According to Hair et al. (Citation2017, p. 13), discriminant validity refers “to items measuring different concepts”. Table presents the results of the discriminant validity analysis.

Table 3. Discriminant validity (HTMT)

Table 4. Results of structural model

In terms of discriminant validity, all the correlation coefficients of this study fell below 0.70, thereby confirming the theoretical uniqueness of each variable in this research (Field, Citation2013). In addition, discriminant validity was evaluated using the Hetero-Trait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) criterion (Table ), despite re-recommendations from previous studies (Henseler et al., Citation2016; Verkijika & De Wet, Citation2018) indicating that HTMT is more suitable to evaluate discriminant validity than Fornell-Larcker’s commonly used criteria. When taking a more conservative position, discriminant validity is reached when the HTMT value is below 0.9 or 0.85 (Neneh, Citation2019; Verkijika & De Wet, Citation2018). Table reveals that the highest obtained HTMT value is 0.847, which is below the conservative value of 0.85. As such, all the constructs meet the criteria for discriminant validity.

4.4. Structural model assessment

Inner model (structural model) was assessed to test the relationship between the endogenous and exogenous variables. The path coefficients were obtained by applying a non-parametric, bootstrapping routine, with 150 cases and 5000 samples for the non-return model (two-tailed; 0.05 significance level; no sign changes). The fitness of the model was assessed using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) based on the criteria that a good model should have an SRMR value <0.08 (Henseler et al., Citation2016). The structural model in Figure had an SRMR of 0.057, thus suggesting an adequate level of model fitness. In the model, the three endogenous variables (Fashion clothing involvement, consumer confidence, and fashion opinion leadership) had R2 values of 0.925, 0.128, and 0.330, respectively, suggesting sufficient predictive accuracy of the structural model (Figure ).

4.5. Assessment of the goodness of fit (GoF)

Overall, R2 for fashion involvement, consumer confidence and fashion opinion leadership in Figure , indicate that the research model explains 92.5%, 12.8% and 33.0%, respectively, of the variance in the endogenous variables. Following formulae given by Tenenhaus et al. (Citation2005), the global goodness-of-fit (GoF) statistic for the research model was calculated using the equation:

where AVE represents the average of all AVE values for the research variables while R2 represents the average of all R2 values in the full path model. The calculated global goodness of fit (GoF) is 0.38, which exceeds the threshold of GoF >0.36 suggested by Wetzels et al. (Citation2009). Therefore, this study concludes that the research model has a good overall fit.

4.6. Path Model Results and Factor Loadings

The PLS estimation results for the structural model as well as the item loadings for the research constructs are shown in Figure .

According to Hair, Hult, et al. (Citation2017), the structural model is used to explain the association between the variables. Zhang and Savalei (Citation2016) mentioned that “the aim of the structural model is to test the hypothesis using bootstrapping procedure”. Particularly, the value between constructs is indicated by a path coefficient value. The findings of the structural model are displayed in Table .

As shown in Figure and Table , the relationship between fashion consciousness and fashion clothing involvement was significant with coefficient = 0.849, t = 18.258 and p < 0.000; thus, the findings support H1. However, the relationship between social comparison and fashion clothing involvement was insignificant with coefficient = 0.037, t = 1.263 and p < 0.207; therefore, the finding rejects H2. The relationship between consumer conformity and fashion clothing involvement was significant with coefficient = 0.116, t = 1.982 and p < 0.038; thus, the finding supports H3. The relationship between purchase involvement and fashion clothing involvement (, t = 1.914 and p < 0.065) and social consciousness and fashion clothing involvement (

, t = 0.508 and p < 0.612) was insignificant; therefore, the findings reject H4 and H5 respectively. Lastly, the relationship between fashion clothing involvement and consumer confidence (

, t = 3.919 and p < 0.000) and fashion clothing involvement and fashion opinion leadership (

, t = 6.165 and p < 0.000) was significant, which, in turn, supports H6 and H7 respectively.

The purpose of this study was to examine the antecedents of fashion clothing involvement, namely fashion consciousness, social comparison, consumer conformity, and purchase involvement. The study also examined the consequences of fashion clothing involvement, namely fashion opinion leadership and consumer confidence. The findings reveal that fashion consciousness influences fashion clothing involvement among gay men. According to Hassan and Harun (Citation2016), fashion-conscious individuals tend to have the latest wardrobe style and their interest in fashion is reflected in their fashion consumption. The findings indicate that there is no relationship between social comparison and fashion clothing involvement among gay men. This finding is inconsistent with prior studies that have found a strong relationship between social comparison and fashion clothing involvement (Powell et al., Citation2018; Tiggemann & Brown, Citation2018). This could be due to gay men constructing their self-image through consumption of fashion brands. Although their consumption is influenced by their society, they still have a need to be unique (Altaf, Troccoli, Paschoalino & Luqueze Citation2012). According to Motale (Citation2015), the need for uniqueness is an imperative personality trait to gay men. The relationship between consumer conformity and fashion clothing involvement has been found to be significant. Gay men use clothing and adornment to create a sense of group identity (separate from the dominant culture), to resist and challenge normative (gendered) expectations, and to signal their sexual identity to the wider world or just to those they know (Rothblum, Citation1994; Taub, Citation2003). In addition, Hobza et al. (Citation2007), assert that gay men feel pressured to conform to the standards set by their counterparts. In addition, gay men often gather information about fashion clothing from their peers to avoid social disapproval (Christopher et al., Citation2014). The study reveals that purchase involvement does not influence fashion clothing involvement. Furthermore, the study also revealed that social consciousness does not influence fashion clothing involvement among gay men. This finding is inconsistent with the literature, which states that gay consumers tend to buy fashion clothing from fashion brands that support causes which are important to the LGBT segment (Gilliland, Citation2017; Radin, Citation2019).

Fashion clothing is used by gay men to enhance their confidence or self-esteem. Here, again, the theory converged with the results of the research—Angelo (Citation2019) argued that “although fashion clothes don’t make the man, they certainly affect the way he feels about himself”. Lastly, the results illustrate that fashion clothing involvement is positively associated with fashion opinion leadership. Kang and Park-Poaps (Citation2010) revealed that fashion-involved consumers tend to learn about new trending fashion clothing earlier in the fashion cycle and purchase new fashion clothes sooner. Therefore, they tend to be fashion leaders, rather than followers (Hassan & Harun, Citation2016). Lang and Armstrong (Citation2018) also found a strong positive relationship between fashion clothing involvement and fashion leadership.

4.7. Testing for Mediation Effect among Variables Using Smart PLS 3

The research conceptual framework utilised as part of this study made use of one mediating variable that mediated the relationship between five predictor variables and two outcome variables. This mediator variable is referred to as “fashion clothing involvement”. The following section presents the results for the mediation effect to determine whether the mediating variable positively and significantly mediated the relationship between the independent variables and dependent variables. Thus, the mediation effect was generated through the ‘consistent PLS algorithm’ using Smart PLS3.

4.8. Discussion of hypotheses results

Table indicates the results for hypotheses 8 to 17. Hypothesis 8 (H8) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between fashion consciousness and consumer confidence) indicates a path coefficient of 0.132 and a T-statistic of 1.987. This relationship was both supported and significant. In addition, this finding suggested that the more gay consumers are involved in their fashion choices, the more they become more aware and confident about their choices. The 9th hypothesis (H9) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social comparison and consumer confidence) shows a path coefficient of 0.585 and a T-statistic of 7.456. This relationship is also supported however, it is not significant, and it suggests that fashion involvement of gay consumers actually positively influences social comparison which leads to higher consumer confidence. However, the effect of social involvement on social comparison is weak as well as that of social comparison on consumer confidence is also weak.

Table 5. Hypothesised Relationships and Resulting Outcomes of the mediation effect

As for hypothesis 10 (H10) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between consumer conformity and consumer confidence). With a path coefficient of 0.295 and a T-statistic of 4.283, this relation is found to be both supported and significant at p < 0, 05. The finding suggests that consumer confidence is a result of fashion clothing involvement from consumers. Hypothesis 11 (H11) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between purchase involvement and consumer confidence) has a path coefficient of 0.182 and a T-statistic of 2.904, which is significant of p < 0, 05. This finding suggests that fashion involvement plays a role in actually facilitating the link between purchase involvement and consumer confidence. In other words, this means that for consumers to feel confident about their purchase decisions, a certain amount of fashion involvement is required.

Hypothesis 12 (H12) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social consciousness and consumer confidence). This relationship has a path coefficient of 0.208 and a T-statistic of 3.130 which indicated that the relationship is both supported and significant at p < 0.05. This means that the association between fashion clothing involvement and social consciousness is needed for consumers to gain confidence in their fashion purchasing decisions. As for the next hypothesis, (13), (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between fashion consciousness and fashion opinion leadership). This relationship is both supported and significant at p < 0.05 with a path coefficient of 0.455 and a T-statistic of 3.360. This finding means that gay fashion consumers can become successful in fashion opinion leadership if they are more involved and are conscious about fashion.

The 14th hypothesis (H14) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social comparison and fashion opinion leadership) has a path coefficient of 0.319 and a T-test value of 3.762. This finding is both supported and significant at p < 0.05. This indicates that when gay consumers are actively involved in fashion-related decisions they can effectively participate in social comparison and act as fashion opinion leaders. Hypothesis 15 (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between consumer conformity and fashion opinion leadership) indicates a path coefficient of 0.283 and T-test of 2.384. This relationship is both supported and significant at p < 0.05. This result suggests that it is imperative for gay consumers to be involved in fashion-related decisions as this is this facilitates successful consumer conformity and acknowledgement on their part as fashion opinion leaders.

Hypothesis 16 (H16) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between purchase involvement and fashion opinion leadership) has a path coefficient of 0.332 and a T-test value of 4.584. This relationship is also supported and significant at p < 0.05. This outcome means that active involvement in fashion allows gay consumers to be more informed purchasers and ultimately become fashion opinion leaders. The last hypothesis, Hypothesis 17 (H17) (Fashion clothing involvement positively mediates the relationship between social consciousness and fashion opinion leadership) has a path coefficient of 0.375 and a T-test value of 4.927. This relationship is both supported and significant at p < 0.05. The result suggests that social conscious and fashion opinion leadership are the outcome of active fashion involvement by gay consumers.

5. Implications

The findings of this study provide helpful insights into international and national fashion clothing producers and brands in planning branding and marketing strategies to promote fashion clothing among gay men. In addition, an effort in understanding this emerging market provide fashion retailers and marketers an advantage in obtaining the first-mover benefit in expanding their businesses. For international fashion clothing brands, it is essential to have a comprehensive understanding of how underlying motivations affect fashion clothing involvement, specifically to understand the ways in which fashion consciousness and consumer conformity influence fashion involvement. The findings showed that gay men are high in social anxiety. Thus, they are aware of fashion norms and they conform. Hence, advertisements may depict fashion conformity within public situations imposing no constraints and that focus on values which are consistent with the gay men values. Advertisements may portray membership, harmony, and associations with close friends with whom gay men identify with. It is important for marketers to make predictions on the relative importance of social influences of consumers’ purchase intentions by measuring consumers’ tendencies to act on the social cues that they use in social comparisons. “Social comparison cues or information can be utilized in advertising techniques in order to allow for positive reinforcement in the adoption of particular fashion clothing or warning against negative social consequences for failing to wear particular attire in particular situations” (Piamphongsant & Mandhachitara, Citation2008, p. 450).

In order to successfully market fashion products and brands to gay men, marketers need to stop assuming that this market is similar to the mainstream and understand this segment as a niche market. Therefore, there is a demand for more personalized segmentation tactics within the fashion market, making use of fashion innovativeness as a unique segmentation technique for this consumer segment. According to McNamara and Descubes (Citation2017), sub-segments (i.e. niche segments within a larger market) are well known for exhibiting great loyalty towards organizations and brands that they identify with or which they believe speak to them personally. Brands should also identify fashion opinion leaders and target their marketing communication strategies to them. They should target gay men fashion bloggers who will serve as mediators of their messages, and consequently as influencers of fashion followers. It might be fruitful for brands to target fashion leaders via social networks, as gay men fashion leaders may make use of social media to spread fashion information to others. Fashion retailers and marketers should consider advertising their products on digital platforms as gay consumers are more engaged online compared to heterosexual consumers. In comparison to the general population, they are 1.8 times more interested in receiving advertising via their mobile phones, 2 times more connected by hours in a day, and 1.5 times more likely to post and consider online reviews (Kennedy, Citation2019). Fashion brands targeting gay men should advertise their clothes in LGBT media. Fashion retailers should try to stock new fashion designs every week to stay at the forefront of fashion and the stocked collection should be small quantity to create the impression of exclusivity. Lastly, they should acknowledge diversity and expression of identities through atmosphere, music and style. Therefore, the creation of appealing services environment is important.

6. Limitations and future research

The findings of the current study contribute significantly to the field of consumer behavior and the fashion market. Like any other study, this one is subject to some limitations—the first being the sample size (only 150 participants were recruited to represent South Africa gay men and this sample may not be a true representation of gay men). A larger sample size could improve the representativeness of the population. Secondly, the researchers made use of web-based surveys in a developing country where a significant portion of the population still does not have access to the internet. Furthermore, the survey only reached people who have a Facebook or Twitter account. Thirdly, caution should be taken in generalising the findings, as regional differences may exist in some countries, especially in African countries that have a different view on homosexuality. Lastly, the influence of other antecedents of fashion clothing involvement (such as materialism, self-monitoring, susceptibility to interpersonal influence, and need for uniqueness) was not considered in this study. However, these limitations do not render the findings less significant, but rather open the way for further research in this area.

Acknowledgements

This publication is based on research that has been supported in part by the University of Cape Town’s Research Committee (URC), and this work is based on the research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Numbers: 120619).

The authors would like to acknowledge the Editor and anonymous reviewers who provided constructive comments to improve this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nkosivile Welcome Madinga

Nkosivile Welcome Madinga is a lecturer within the Marketing Section at University of Cape Town. His research focus is in LGBTQIA+ Consumer Behaviour, Status Consumption and Pink Tourism.

Eugine Tafadzwa Maziriri

Eugine Tafadzwa Maziriri is currently a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Business Management at University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, South Africa. He has a keen interest in consumer behaviour.

Bongazana Hilda Dondolo

Bongazana Hilda Dondolo is the Assistant Dean for Teaching & Learning in the Faculty of Humanities at the Tshwane University of Technology.

Tinashe Chuchu

Tinashe Chuchu is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Marketing Management at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. He’s research area of focus is Customer Decision-Making, Consumer Behaviour and Marketing Management.

References

- Aaker, J. L., Benet-Martinez, V., & Garolera, J. (2001). Consumption symbols as carriers of culture; a study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(3), 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.492

- Altaf, J. C., Troccoli, I. R., Paschoalino, C. B., & Luqueze, M. A. (2012). Luxury consumption: A mirror of gay consumers sexual option? RECADM, 11(1), 162–27. https://doi.org/10.5329/RECADM.20121101010

- Amoha, D. (2012). The influence of internalized homophobia and anti-effeminacy attitudes on gay men’s fashion involvement and subsequent preference for masculine or feminine appearance. ProQuest, 24(1), 1–17. https://shareok.org/handle/11244/45156

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychology Bulletin, 1(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Angelo, P. (2019). Self-confidence for gay men so that you are not afraid to walk up to someone you like. Retrieved September16, 2019, from. http://www.paulangelo.com/self-confidence-for-gay-men-so-that-you-are-not-afraid-to-walk-up-to-someone-you-like/

- Aung, M., & Sha, O. (2016). Clothing consumption culture of a neo-tribe: Gay professionals within the subculture of gay consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(1), 34–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2014-0053

- Bai, X. J., Liu, X., & Liu, H. J. (2013). The mediating effects of social comparison on the relationship between achievement goal and academic self-efficacy: Evidence from the junior high school students. Journal of Psychological Science, 36(1), 1413–1420. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-XLKX201306023.htm

- Bao, Y., Bao, Y., & Sheng, S. (2011). Motivating purchase of private brands: Effects of store image, product signatureness, and quality variation. Journal of Business Research, 64(2), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.02.007

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bertrandias, L., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2006). Some psychological motivations for fashion opinion leadership and fashion opinion seeking. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 10(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020610651105

- Bhaduri, G., & Stanforth, N. (2017). To (or not to) label products as artisanal: Effect of fashion involvement on customer perceived value. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 26(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2016-1153

- Braun, K., Cleff, T., & Walter, N. (2015). Rich, Lavish and trendy: Is lesbian consumers’ fashion shopping behaviour similar to gay’s? A comparative study of lesbian fashion consumption behaviour in Germany. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(4), 445–465. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-10-2014-0073

- Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2007). Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007

- Chen, J., Aung, M., Liang, J., & Sha, O. (2004). The dream market: An exploratory study of gay professional consumers’ homosexual identities and their fashion involvement and buying behaviour. In L. Scott & C. Thompson (Eds.), GCB - gender and consumer behaviour (Vol. 7, pp. 1-7). Association for Consumer Research.

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. V. Esposito, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer.

- Christopher, A., John, S. F., & Sudhahar, C. (2014). Influence of peers in purchase decision making of smartphone: A study conducted in Coimbatore. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(8), 1–7. http://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0814/ijsrp-p3261.pdf

- Chui, C. T. B., Nik, N. S., & Azman, N. F. (2017). Making sense of fashion involvement among Malaysian Gen Y and its implications. Journal of Emerging Economics & Islamic Research, 5(4), 10–17. http://jeeir.com/v2/images/2017V5N4/JEEIR2017_542_Carol.pdf

- Clarke, V., & Turner, K. (2007). Clothes maketh the queer? Dress, appearance and the construction of lesbian, gay and bisexual identities. Feminism and Psychology, 17(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353507076561

- Cooley, C. H. (1992). Human nature and the social order. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

- Ferguson, J. L. (2016). How clothing choices affect and reflect self-image. Retrieved September 16, 2019, from. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/how-clothing-choices-affect-and-reflect-your-self-image_b_9163992

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(1), 117–140. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Fibre2Fashion.Com. (2018). What is fashion design? Retrieved May 22, 2018, from. http://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/2860/what-is-fashion-design?page=1

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS (4th ed.). Sage.

- Foddy, M., & Crundall, I. (1993). A field study of social comparison processes in ability evaluation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 32(4), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1993.tb01002.x

- Forehand, M. R., & Deshpande, R. (2001). What we see makes us who we are: Priming ethnic self-awareness and advertising response. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(3), 336–348. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.3.336.18871

- Fu, W., & Liang, B. C. (2018). How Millennials personality traits influence their eco-fashion purchase behaviour. Athens Journal of Business and Economics, 1(2), 1–14. https://www.athensjournals.gr/business/2018-1-X-Y-Fu.pdf

- Gilliland, N. (2017). How ethical fashion brands are marketing to conscious consumers. Retrieved October 22, 2019, from. https://econsultancy.com/how-ethical-fashion-brands-are-marketing-to-conscious-consumers/

- Gilvin, A. (2014). Hot and haute: Alphadi’s fashion for peace. Summer, 47(2), 40–55. https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/AFAR_a_00137?journalCode=afar&mobileUi=0&

- Giovannini, S., Xu, Y., & Thomas, J. (2015). Luxury fashion consumption and Generation Y consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing Management: An International Journal, 20(3), 276–299.

- Goldsmith, R. E., Freiden, J. B., & Kilsheimer, J. C. (1993). Social values and female fashion leadership: A cross-cultural study. Psychology & Marketing, 1(5), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220100504

- Grubb, E. L., & Stern, B. L. (1971). Self-concept and significant others. Journal of Marketing Research, 8(3), 382–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377100800319

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados. Bookman Editora.

- Hair, J. F., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(1), 442–458. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/An-updated-and-expanded-assessment-of-PLS-SEM-in-Hair-Hollingsworth/f0627534178060ccf6d2cd006b1346efd3e7f5f5

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(5), 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Editorial-partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46((1–2), 1–12), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European business review.

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Hassan, S. H., & Harun, H. (2016). Factors influencing fashion consciousness in hijab fashion consumption among hijabistas. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 7(4), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-10-2014-0064

- Hattingh, C., Spencer, J. P., & Venske, E. (2011). Economic impact of special interest tourism on Cape Town: A case study of the 2009 Mother City queer project. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 17(3), 380–398. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpherd.v17i3.71090

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

- Hayes, A. F., Preacher, K. J., & Myers, T. A. (2011). Mediation and the estimation of indirect effects in political communication research. Sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures, and analytical techniques. 23(1), 434–465.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing”. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Advances in international marketing (Vol. 20, pp. 277–320). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Henseler, J., & Chin, W. W. (2010). A comparison of approaches for the analysis of interaction effects between latent variables using partial least squares path modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 17(1), 82–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903439003

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Hernández-Perlines, F., Moreno-García, J., & Yañez-Araque, B. (2016). The mediating role of competitive strategy in international entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5383–5389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.142

- Hobza, C. L., Walker, K. E., Yakushko, O., & Peugh, J. L. (2007). What about men? Social comparison and the images on body and self-esteem. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 8(3), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.8.3.161

- Hourigan, S. R., & Bougoure, U. (2012). Towards a better understanding of fashion clothing involvement. Australian Marketing Journal, 20(1), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.10.004

- Hsia, J., & Tseng, A. (2015). Exploring the relationships among locus of control, work enthusiasm, leader-member exchange, organizational commitment, job involvement, and organizational citizenship behavior of high-tech employees in Taiwan. Universal Journal of Management, 3(11), 463–469. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujm.2015.031105

- Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., Hameed, Z., Khan, I. K., & Azam, R. I. (2018). Social comparison, materialism, and compulsive buying based on stimulus-response-model: A comparative study among adolescents and young adults. Young Consumers, 19(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-07-2017-00713

- Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2019). Celebrity fashion brand endorsement in Facebook viral marketing and social commerce: Interactive effects of social identification, materialism, fashion involvement, and opinion leadership. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 23(1), 104–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-01-2018-0001

- Jordaan, Y., & Simpson, M. N. (2006). Consumer innovativeness among females in specific fashion stores in the Menlyn shopping centre. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, 34(1), 32–40.

- Josiassen, A. (2010). Young Australian consumers and the country-of-original effect: Investigation of the moderating roles of product involvement and perceived product-origin congruency. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(1), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2009.10.004

- Joung, H., & Miller, N. (2006). Factors of dress affecting self‐esteem in older females. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 10(4), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020610701983

- Kang, J., & Park-Poaps, H. (2010). Hedonic and utilitarian shopping motivations of fashion leadership. Journal of Fashion Marketing Management, 14(2), 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021011046138

- Kates, M. S. (2002). The protean quality of subcultural consumption: An ethnographic account of gay consumer. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1086/344427

- Kennedy, D. S. (2019). Insightful tips for thoughtfully Marketing to LGBTQ customers. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from. https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/333596

- Keogan, K. (2013). The relationship between clothing preference, self-concept and self-esteem [Bachelor Thesis]. DBS School of Arts.

- Khan, S. (2013). Predictors of fashion clothing involvement amongst Indian youth. International Journal of Social Sciences, 11(3), 70–79.

- Khare, A. (2015). Antecedents to green buying behaviour: A study on consumers in an emerging economy. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(3), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-05-2014-0083

- Khare, A., Mishra, A., & Parveen, C. (2012). Influence of collective self esteem on fashion clothing involvement among Indian Women. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021211203023

- Kim, H. S. (2005). Consumer profiles of apparel product involvement and values. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 9(2), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020510599358

- Kim, J., Park, J., & Glovinsky, P. L. (2018). Customer involvement, fashion consciousness, and loyalty for fast-fashion retailers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(3), 01–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-03-2017-0027

- Kotler, P. (1965). Behavior models for analyzing buyers. Journal of Marketing, 29(4), :37–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296502900408

- Kumar, S. (2018). Challenges of fashion retaining in 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from. https://customerthink.com/challenges-of-fashion-retailing-in-2018/

- Ladhari, R., Gonthier, J., & Lajante, M. (2019). Generation Y and online fashion shopping: Orientations and profiles. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 48(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.02.003

- Lang, C., & Armstrong, C. M. J. (2018). Collaborative consumption: The influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 13(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2017.11.005

- Lee, S., & Workman, J. E. (2014). Gossip, self-monitoring and fashion leadership: Comparison of US and South Korean consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(6/7), 452–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-04-2014-0942

- Lertwannawit, A., & Mandhachitara, R. (2012). Interpersonal effects on fashion consciousness and status consumption moderated by materialism in metropolitan men. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1408–1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.006

- Liu, P., He, J., & Li, A. (2019). Upward social comparison on social network sites and impulse buying: A moderated mediation model of negative affect and rumination. Computers in Human Behaviour, 96(1), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.003

- Madinga, N. W. (2016). Selected antecedents to approach status consumption in fashion brands among Township youth consumers in the Sedibeng District [Unpublished Masters Dissertation]. Vaal University of Technology.

- Malhotra, N. K. (2010). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Prentice Hall.

- Mashapa, M. M., Maziriri, E. T., & Madinga, N. W. (2019). Modelling key selected multisensory dimensions on place satisfaction and place attachment among tourists in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 7(2), 580–594. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.25224-382

- McFatter, R. D. (2005). Fashion involvement of affluent female consumers [Unpublished of PhD thesis]. Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College. McNeese State University.

- McNamara, T., & Descubes, I. (2017). Why marketing targeted at gay and lesbian consumers often misses its mark. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from. https://www.marketingmag.com.au/hubs-c/gay-lesbian-marketing-lgbtiqa/

- McNeill, L., & McKay, J. (2016). Fashioning masculinity among young New Zealand men: Young men, shopping for clothes and social identity. Young Consumers, 17(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-09-2015-00558

- Michaelidou, N., & Dibb, S. (2006). Product involvement: An application in clothing. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 5(5), 442–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.192

- Miquel, S., Caplliure, E. M., & Aldas-Manzano, J. (2002). The effect of personal involvement on the decision to buy store brands. Journal of Product Brand Management, 11(1), :6–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420210419513

- Molla-Descals, A., Lorenzo-Romero, C., Mondejar-Jimenez, & Fayos-Gardio, T. (2012). An overview about fashion retailing sector: UK versus Spain. International Business and Economics Research Journal, 11(13), 1439–1446.

- Motale, M. D. B. (2015). Black generation Y male students’ fashion consciousness and need for uniqueness [PhD thesis]. Northwest University.

- Motale, M. D. B., Bevan-Dye, A. L., & de Klerk, N. (2014). African Generation Y male students’ fashion consciousness behavior. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(21), 121–128. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286313671_African_Generation_Y_male_students'_fashion_consciousness_behaviour

- Nduna, M., Mthombeni, A., Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A., & Mogotsi, I. (2017). Studying sexuality: LGBT experiences in institutions of higher education in South Africa. South African Journal of High Education, 13(1), 1–13. https://www.journals.ac.za/index.php/sajhe/article/view/1330/1596