Abstract

This paper examines the complexity of balancing public interest and individual rights in the use of investigative journalism to combat corruption.

The paper looks at a number of public interest journalism exposés and the various methods that the investigative journalists used to uncover corruption in public and private institutions in the country. The principal assumption of this paper is that undercover journalism, pushes journalism ethics to the limit by employing methods that are regarded as both morally and legally wrong. These involve covert surveillance or sting operations during which the journalist hides his identity, invasion of the privacy, and recording or filming people without their consent.

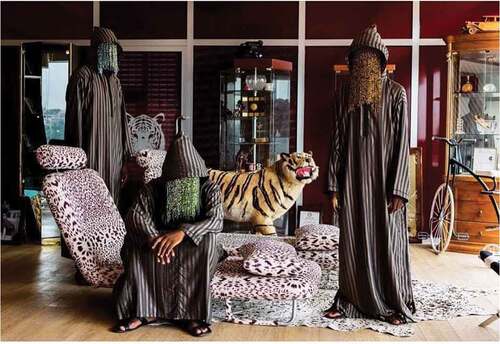

This paper examines these investigative techniques under the lense of codes of ethics for journalists as well as constitutional provisions, legislation and judicial pronouncements. It particularly examined how the courts, including precedents from other commonwealth countries, have handled the invasion of privacy under the legal principle of public interest as well as any other exceptions anticipated by law.The paper used largely the work of the country’s foremost undercover journalist, Anas Aremeyaw Anas, to examine the legal basis of investigative reporting which in turn provide insight into investigate journalism practices, ethics, public interest, the right of the public to know, and individual right to privacy.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Since Ghana moved from military dictatorship to democratic rule in 1992, it has witnessed a vibrant media landscape that is highly supportive of the new political dispensation. While providing the relevant space for citizen participation in governance, the media also hold the leaders of the country accountable for their stewardship and expose corruption in the system.

Judges and magistrates were exposed when they were caught on camera receiving bribes to thwart the course of justice. Equally scandalous were activities at the Ghana Football Association (GFA) in match fixing for bribes. Those involved were prosecuted and punished.

The Whistleblowers Act encourages investigative journalists but the country’s cultural values and norms, make fighting corruption an uphill task. Investigative reporters need to balance their methods of news gathering, with the right of the public to be informed, and the right of the individual to privacy. The paper makes important suggestions but these are not necessarily absolute in their claims.

1. Introduction

Investigative journalism plays a critical role in serving society by detecting and exposing corruption, enhancing transparency, and reinforcing public opinion. It is meant to uncover hidden facts; this means “going after what someone wants to hide” (H. de Burgh, Citation2008, p. 15). For this reason, investigative journalists “often shoulder the responsibility for uncovering corruption and wrongdoing” (H. de Burgh, Citation2008; Kaplan, 2008; O’Neil, 2010 as cited in Almania, Citation2017, p. 3). They do not rely on speeches by public officials and government spokespersons as is often the case in routine news reporting. Another defining characteristic of investigative journalism and its variant, undercover reporting is that it seeks to expose unethical, immoral and illegal behaviour by government officials, politicians as well as private citizens Kovach and Rosentiel (Citation2014). It has the potential to make a worthwhile contribution to society by “drawing attention to failures within society’s systems of regulation and to the ways in which those systems can be circumvented by the rich, the powerful and the corrupt” (H. de Burgh, Citation2008).

Investigative journalism is not widely practised in Ghana and therefore not popular in its methods and approach to uncovering hidden facts about corruption fostered often by systemic failures and the forces of institutional inertia. It is a costly venture in time and finances and only a few editors and media owners would want to embark on investigative reporting. Though there had been some investigative reporting in the country’s media in the 1970’s through the very early 1990’s, the few available media at the time with a proportionately limited audience did not make such work stand out.

Over the past one and a half decades or two, the investigative work of one journalist, Anas Aremeyaw Anas, has gained prominence beyond the shores of Ghana, and many people now appear to appreciate a sense of what this genre of journalism is all about. Not surprisingly, a section of the public has questioned the journalist’s techniques and approach to obtaining information. So also have the works of another Ghanaian journalist, Manasseh Azure Awuni, unsettled many who have been exposed in underhand dealings. Quite often the “methods of obtaining information employed by journalists define the line and reflect the tension between the public’s right to know the truth and an individual’s claim to anonymity and privacy” (Mustapha-Koiki & Ayedun-Aluma, Citation2013, p. 543).

The purpose of this paper is to critically examine the complexity of balancing public interest and individual rights in the use of investigative journalism to combat corruption. The study was guided by the following research question: To what extent is the use of evasive techniques in investigative reporting justifiable?

In June 2018, Anas and his Tiger Eye P.I crew released a documentary on corruption in Football in Africa with Ghana at the centre that showed country’s football president, Kwesi Nyantakyi, and hundreds of local and international referees and officials taking cash bribes and gifts. The Confederation of African Football (CAF) banned and suspended most of the referees and subsequently led to the dissolution of the Ghana Football Association and the suspension of the local football league for a year.

This was not the first time allegations of corruption had been raised about football in the country, but it was the first time that hardcore evidence had been produced to back the notorious allegations. But some of the culprits in the documentary challenged the method used to obtain the evidence in court. They argued the method was an entrapment, which infringed on their individual right to privacy. However, the High Court siting in Accra ruled in favour of Anas and Tiger Eye P.I. The court held that the recording, although without the applicants’ consent, was of utmost interest to Ghanaians, whose love for football was unmatched.

It is a fact that investigative reporting “not only demands the highest standards of accuracy but also delivers more ethical dilemmas on a daily basis than almost any other form of journalism” (Houston, Citation2009, p. 108). A core assumption of this study is that in satisfying the public’s right to know, investigative reporting techniques such as sting operations, impersonation, secret video recording as employed in the exposés infringe on the individual’s right to privacy. The study relied on documentations as secondary sources for some of its data.

1.1. Statement of the problem

People in leadership positions, especially senior public officials, often try to conceal vital information about wrongdoing or under-performance in their organisations from the public. Some of them are either under oath to not divulge such information, or they do so deliberately to protect themselves and their work. Investigative journalists digging to get to the bottom of a public interest matter do so in their watchdog role and as a duty they owe society. In the event of probable difficulties in getting access to information that is being concealed, they employ various techniques to access it. On the basis of this problematic, this paper examines the evasive techniques, used in selected exposés for this study, particularly the work of Anas Aremeyaw Anas, and determines whether they infringe on the privacy of individuals involved in these scandals while trying to achieve the right of the public to know. The study is limited in scope to the works of Anas and Awuni because of the controversy some of the videos have stirred regarding their approach.

1.2. Conceptual framework

1.2.1. Investigative journalism

There is not one precise standard definition of investigative journalism. However, various definitions by different scholars are in harmony with its goals and expectations. In investigative journalism reporters dig deeply into a single story that may uncover corruption, call for a review of government policies or those of corporate houses, or draw attention to social, economic, political or cultural trends (Nazakat & Media Programme, Citation2010). The practice aims at exposing public matters that are otherwise concealed, either deliberately or accidentally. Investigative reporting relies on materials gathered through the reporter’s own initiative, rather than those provided by government officials or NGOs as is often the case in routine traditional news gathering and reporting.

Horrie (Citation2008, p. 114) defines investigative journalism as “a generic form in which the journalist or newspaper initiates the story based on a suspicion of wrongdoing, rather than simply reporting in a more passive and disinterested way the routine news of the day, or unscheduled disasters and accidents”. For Kovach and Rosentiel (Citation2014) investigative reporting involves not simply shedding light on a subject but also “making a more prosecutorial case that something is wrong”. They claim the investigation could result in official public investigations about the subject or activity exposed in such a way that may also produce “the first rough draft of legislation” that eventually outlaws certain forms of wrongdoing such as corruption (H. de Burgh, Citation2000, p. 18).

The Watergate scandal of 1972, exposed by two American investigative reporters, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward of the Washington Post is a classic example of investigative reporting that resulted in an official public probe. The exposé led to the forced resignation of President Richard Nixon from office in 1974 (H. de Burgh, Citation2000, pp. 78–79). According McFadyen, (2008 as cited in Mustapha-Koiki & Ayedun-Aluma, Citation2013, p. 544), the reporting was only possible through the protection of a source whose identity was kept secret for 30 years. This has been brought up here to emphasize the essence of source protection by journalists.

A more recent example is a 2019-undercover investigation into the sale of government contracts in Ghana by freelancer Manasseh Azure Awuni. The investigative piece revealed that a company co-owned by the chief executive of Ghana’s Public Procurement Authority (PPA), Adjenim Boateng Adjei had been selling government contracts it won through single sourcing and restrictive tendering to the highest bidder. It led to his suspension and prosecution by the special prosecutor’s office, as well as that of the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) probing into matters of conflict of interest. It was the secret recording of the head of the company at the company premises that revealed how the company secured and sold contracts that compromised Boateng Adjei.

In 2016, reporters of the Daily Telegraph posed as football agents seeking to outwit the English FA rules on player transfer. England manager, Sam Allardyce, was found to have abused his office through the cutting of such deals. Allardyce challenged the use of subterfuge by the newspaper as unjustified. The Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) after a thorough investigation based on the complaint by Allardyce concluded that the method used by the Daily Telegraph was justified in the public interest “(BBC,” Citation2018).

Yet another example of investigative journalism that resulted in official public investigation and prosecution is the 2009 scandal of British MPs inflating their allowances, which were investigated by The Telegraph. “Three MPs were jailed for fiddling their expense claims (Bingham, Citation2011). It turned out that The Telegraph had bought the information in contravention of media ethics. However Brooke (Citation2010, pp. 248–253) holds that getting the information through legal means was impossible. This raises the issue of undercover reporting and the use of evasive techniques. While journalists risk their lives to dig deeply into a topic of public interest bordering on corruption, they also have to sometimes hide their identity to be able to gain access to powerful persons, premises, or locations of hidden information to fulfil their watchdog role. It is of essence to look briefly at ethics, public interest, sting, entrapment, and privacy; how these occurred in the practice of investigative/undercover journalism elsewhere.

1.3. Ethics of investigative journalism

Undercover journalism has ethical implications for which reason there are codes of conduct to guide journalists to avoid attracting legal suits against their news organisations. It is also to ensure that they maintain professional standards and credibility. In the US, the Society of Professional Journalism’s code of ethics states that journalists should:

“Avoid undercover or other surreptitious methods of gathering information except when traditional open methods will not yield information vital to the public. The use of such methods should be explained as part of the story” (Chernow, Citation2014).

Media regulatory bodies for British journalists (including IPSO for print and online journalists and OFCOM for broadcast journalists) allow various ethical guidelines to be breached if there is a clear public interest in the story.

Section 10 of IPSO editor code:

Clause 10 (Clandestine devices and subterfuge)

i. The press must not seek to obtain or publish material acquired by using hidden cameras or clandestine listening devices; or by intercepting private or mobile telephone calls, messages or emails; or by the unauthorised removal of documents or photographs; or by accessing digitally-held information without consent.

Ethics assumes different definitions by different scholars. Ward (Citation2006, p. 100) defines it “as a set of principles and norms that, at least to some degree, guide journalistic practice”. For his part, Frost (Citation2011, p. 10) sees ethics as “a way of studying morality which allows decisions to be made when individuals face specific cases of moral dilemma”. Sanders (Citation2003, p. 15) looks at it as “the study of the grounds and principles for right and wrong human behaviour”. Investigative journalism code of professional conduct guides journalists to resolve moral dilemmas in the course of investigating a matter of public interest. Below is the code of ethics of investigative journalism of the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ), Berlin. Similar codes elsewhere may not differ much. The ICFJ recommends that undercover journalists should:

Make sure you have exhausted all other options to get the information you want through other means.

Know the law. Make sure what you are doing is not illegal.

Ask yourself: Are the possible findings of this investigation of such a high value and will serve an important enough cause, that invasion of privacy and deception are defensible?

Make sure you are not engaging in entrapment, i.e. inducing the subjects of your investigation to do something wrong, rather than observing them do it on their own.

Keep in mind that readers and/or viewers could sometimes find the use of undercover reporting deceptive and distasteful and may sympathize with your subjects if you do it. You want your audience focused on your subject, not on you.

Once you have established that an undercover investigation is justified, draw a detailed plan of how you intend to carry it out and what you hope to get out of it.

Make sure someone knows what you are doing and what your plan is, so you can call on them for help if something goes wrong.

Make sure your superiors support the project and will bail you out if you end up in legal trouble. Your project may also be putting them at risk, so don’t surprise them.

Once your undercover investigation is completed, reveal your identity and give the subjects of your investigation a chance to comment on the findings.

In Ghana, there is not any code of ethics for undercover journalism. What is available is a generic code for routine traditional journalism practice. The Ghana Journalists Association’ (GJA) code of ethics is one such source. The 2017 GJA revised code of ethics provides that journalists must “obtain information, videos, data, photographs and illustrations only by honest, straightforward, fair and open means unless otherwise tampered by public interest considerations”. For the lack of such a code, investigative journalists in the country rely on national laws and international codes for guidance.

Getting the scoop on a story goes beyond simple research and interviews. The only way to dig up the truth is often to go incognito, fabricating identities, and in some cases using hidden cameras. For instance, in 1887 Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, under the pen name Nelly Bly, in an undercover assignment for the New York World, acted insanely and got committed into a female lunatic asylum and reported on conditions inside (Career News Insider, Citation2012). Similarly, two years earlier in 1885, William Thomas Stead of the London-based Pall Mall Gazette, operating undercover using sting, “bought a 12-year-old girl to prove his investigative story of child prostitution” (H. de Burgh, Citation2008, pp. 44–45). Stead’s justification for going undercover was “to expose how easy it was to procure young girls for prostitution in the United Kingdom at the end of the 19th century” (H. de Burgh, Citation2008, p. 45). This was one of the instances where a journalist had to choose between what is morally wrong or right and the need to expose it so as to generate public debate or bring about changes in laws to control vice in society. In the opinion of Waisbord (Citation2001, p. 15), such choices can be justified ethically as long as journalists can determine “who will benefit as a result of the reporting”. In determining such choices the right of the public to know and public interest may be given priority over other considerations.

1.4. Public interest

There is no one generally shared definition of what constitutes public interest. Simple and loose definitions such as public interest being about the common good, the general welfare and the security and well-being of everyone in the community do not lend themselves to absolute clarity for everybody. According to Franklin et al., (2005 as cited in Ceferin & Poler, Citation2018, p. 25):

The term is used in both legal and media contexts of ethics, communication policies, and social responsibility. It denotes specific criteria by which the usual legal rights of an individual or organisation, e.g., to defend their reputation, or protect confidential matters, privacy or copyright, are justifiably overridden by the need for information to be published to benefit society, e.g., to help it understand events or scrutinize people in the public eye.

Hill and Lashmar (Citation2014, p. 129) defines public interest as “important information that should be available to the public to help them make informed decisions in a democratic society”. Similarly, Wilson (Citation1996 as cited in Ceferin & Poler, Citation2018, p. 28) states that the public interest “refers to serious matters in which the public have or ought to have a legitimate interest”. It is about what matters to everyone in society and differs from those things that the public is interested in. Public interest provides justification for how journalists’ work sometimes infringes on the individual’s right to privacy. This notion of public interest “underscores the moral authority of journalists to ask hard questions of people in power, to invade the privacy of others, and to sometimes test the limits of ethical practice in order to discover the truth” (Ethical Journalism Network. https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/the-public-interest).

In Ghana, to understand the term, the starting point is perhaps the 1992 constitution. It has provisions on what constitutes public interest. The constitution provides that every person is entitled to fundamental human rights as guaranteed under Chapter 5, including the right to privacy. Article 12(2) provides that the enjoyment of such rights are subject to “ … respect and freedoms of others and for the public interest”. Public interest is further explained in article 295 to include … “any right or advantage which ensures or is intended to ensure the benefit generally of the whole of the people of Ghana”.

1.5. Right to privacy and invasion of privacy

Archard (1998 as cited in Mustapha-Koiki & Ayedun-Aluma, Citation2013, p. 543) defines privacy as keeping information non-public or undisclosed. The right to privacy is the right to be left alone to live one’s own life with the minimum degree of interference. By the right to privacy USlegal.com (2012) refers to “the concept that one’s personal information is protected from public scrutiny. Invasion of privacy is the intrusion into the personal life of another, without just cause, which can give the person whose privacy has been invaded a right to bring a lawsuit for damages against the person or entity that intruded. It encompasses workplace monitoring, Internet privacy, data collection, and other means of disseminating private information”.

The1992 constitution guarantees the privacy of every person. Article 18(2) provides that “ … no person shall be subjected to interference with the privacy of his home, property, correspondence or communication except in accordance with law and as may be necessary in a free and democratic society … ”

Alesu-Dordzi (Citation2018) observes:

On the one hand, it guarantees the right of individuals to privacy in their homes, property, correspondence and communication. But there is a caveat. The constitution goes on to say that a person’s right to privacy may be interfered with legitimately if, amongst other things, it is necessary for public safety, or the economic well-being of the country, or for the protection of health or morals and for the prevention of crime.

The Supreme Court of Ghana in interpreting article 18(2) of the constitution attempted to capture what privacy entails. Pwanmang JSC in the case of Madam Abena Pokua vs. Agricultural Development Bank, unreported judgment of Supreme Court dated 20 December 2017 in Suit No. CA/J4/31/2015, noted that the concept of privacy is so broad a constitutional right that it defies a concise and simple definition. The learned justice further stated that “privacy comprises a large bundle of rights some of which have been listed in article 18(2) above. However, under the right to privacy is covered an individual’s right to be left alone to live his life free from unwanted intrusion, scrutiny and publicity. It is the right of a person to be secluded, secretive and anonymous in society and to have control of intrusions into the sphere of his private life”.

The following may constitute the law on privacy in this country:

Interference with his private, family and home life;

Interference with his physical and mental integrity or his moral and intellectual freedom;

Being placed in a false light;

The disclosure of embarrassing facts relating to his private life;

The use of his name, identity or likeness;

Spying, prying, watching and besetting;

Interference with his correspondence;

Misuse of his private communications, written or oral;(Committee on Privacy, Citation1972, p. 327).

Invasion of privacy is the intrusion into the personal life of another without just cause, which can give the person whose privacy has been invaded a right to bring a lawsuit for damages against the intruding person or entity. It encompasses workplace monitoring, Internet privacy, data collection, and other means of disseminating private information.

Celebrities by the nature of their work are always in the eye of the public, and so they are not very much protected by privacy laws. Politicians, corporate leaders, or people who rely on their public image for their livelihood are sometimes people whose private affairs may have an important impact on their public duties. Media invasion of their privacy is ethically justified by reasons of the public interest. Coleman and Dann (Citation2016, p. 67) argue that invasion of privacy should serve the public interest, which is not “the interest of an individual, or a particular group, but an interest that all citizens share, such as their interest in justice, safety, health or good governance.

1.6. Impersonation

It is the crime of pretending to be another individual in order to deceive others and gain some advantage. Undercover journalists often employ this technique to get their stories. German undercover journalist, Gunter Wallraff is well known for his successful impersonation. He would enter a subject area by deception and record his experiences. His identity would be constructed to allow him access, which would ordinarily be refused (Mustapha-Koiki & Ayedun-Aluma, Citation2013, p. 543). Impersonation, as the example of Wallraff goes, is a way to deceive someone into believing that the journalist is who he is not in reality. Journalists who employ this method argue it is the public’s right to be informed.

2. Literature review and theoretical framework

2.1.1 Theoretical Framework

Eighteenth Century German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s duty-based moral theory also known as deontological ethics “is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules, rather than based on the consequences of the action”. (Seven Pillars Institute, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/morality101/Kantian-duty-based-deontological-ethics). The theory enjoins people to do the right thing for the right reason because it is the right thing to do. By this theory, an undercover reporter will not be looking at whether exposing corruption in a public institution will land bosses in serious trouble. Rather he would be looking at whether exposing corruption is right or wrong. He is obligated to go ahead with what is morally right to do because it fulfils his duty. The theory has been criticised for its absolutist inclination which does not help very much in resolving certain moral dilemmas such as lying to save a situation.

The theory of utilitarianism is more concerned about the consequences of an act than the rightness or wrongness of that act. The proponent of the theory, 18th Century English philosopher and jurist, Jeremy Bentham, and associate John Stuart Mill believe that people should act in the best interest of everyone concerned. Sanders (Citation2003, p. 19) explains this view by asserting that the key idea of utilitarianism is that the “consequences of actions are the key to assessing whether they are ethical”. This explanation is further reinforced by Frost’s example of “ruining the life of a children’s home superintendent by exposing him as a child abuser on the basis that it has saved children” (2011, pp 14–15). Thus utilitarianism is more concerned about the consequences of an ethical judgement which should inure to the good of the majority rather than the interest of a single individual.

Though at variance with each other, duty-based moral theory and the theory of utilitarianism have been used for the study in order to explain how public interest makes it compelling to do what is right, what one is obligated to do out of duty and at the same time doing things by looking at the resultant effects. The two theories provide justification for journalists’ use of various methods to obtain information and expose wrongdoing in society.

Jürgen Habermas’ theory of the public sphere used for this study derives from his The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962/1989). The public sphere refers to a notional “space” which “provides a more or less autonomous and open arena or forum for public debate” (McQuail, Citation2005, p. 181). The relevance of the theory lies in public access to every kind of information that may be available for it to access. Everybody, irrespective of social class and profession, is free to participate and debate public interest issues in the open forum. The modern mass media provide that forum (public sphere) which is not limited to a privileged bourgeois class as used to be the case in 17th and 18th century Europe. In the context of Anas’ and Awuni’s exposés, they are open to public viewing to generate relevant debates.

2.1. Review of relevant literature

There is a flurry of literature to show how investigative journalism is practised in Ghana and elsewhere in Africa, North America and Western Europe; how the law applies to ethical infractions, including infringement of privacy by the media. For brevity’s sake, few studies have been reviewed to provide insights into the use of various methods of gathering information in undercover reporting and to what extent they violate the professional code of ethics or their use is justified.

2.2.1. The Kenyan case study

In his study of tabloid and broadsheet newspapers in Kenya, Ongowo (Citation2011) did a comparative content analysis of two weekly newspapers, the Weekly Citizen (tabloid) and the Sunday Nation (broadsheet). The researcher also interviewed Kenyan journalists to gauge the ethics and standards of investigative journalism in the two papers. The study established that the two newspapers breached certain ethics of investigative journalism in some situations by using questionable methods to gather information for their stories. They invaded people’s privacy, secretly recorded or filmed news subjects, and hacked telephones and computers of targets or their proxies. But they justify the breaches by citing the public’s right to know, and the endeavour to fight corruption and wrongdoing in society.

2.2.2. The Nigerian cases

Mustapha-Koiki (Citation2013 as cited in Mustapha-Koiki & Ayedun-Aluma, Citation2013, p. 544) examined the methods employed by two Nigerian journalists in their investigative stories. In one case study, Dele Agekameh, former senior associate editor of Tell magazine, joined a Nigerian Police patrol team on a reconnaissance mission against car robbers, drugs and arms dealers. Agekameh though not a police officer, acted in that capacity and succeeded in doing a good story titled “Axis of Evil” which made the cover for that week. The patrol team is reported to have arrested and killed some of the robbers and recovered vehicles along their routes on the border between Nigeria and Benin.

In another case study, “Inside Nigeria’s Industrial Concentration Camps” the investigative reporter, Emmanuel Maya of the Sun Newspaper, posed as a casual labourer and worked in different factories in Lagos for a period of three weeks. His aim was to uncover the inhuman conditions that thousands of Nigerians were exposed to in factories run by Asians.

Maya succeeded in taking pictures in a section of one of the factories, where they moulded plastics. The fact that he had to hide his small camera in his pants proves the challenges of the task and his determination to use every means possible to accomplish it.

In a 2009 article in the Sun Newspaper titled, “Europe by desert: tears of African migrants”, Maya reports travelling a total of 4,318 kilometres for 37 days across seven countries and the Sahara Desert in the company of illegal African migrants on their way to Europe. “He travelled incognito from Nigeria to Benin Republic, Togo, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and finally Libya, to tell the story of human traffickers, sex slavery in transit camps, starvation, desert bandits, arduous toil in a salt mine, cruel thirst and deaths in the hot desert” (Hunter, Citation2012, p. 50). In all of these stories, the undercover journalists used impersonation or false identities to uncover what they could not have achieved through conventional methods of investigation. Their stories were in the public interest even if somebody’s right and interest were violated.

Ghana: Privacy and Case law

The right to privacy is a basic human right inherent in a democracy and rule of law such as Ghana. The laws frown on breach of privacy by any person or authority unless under the exceptions discussed earlier in this paper. What this may mean for journalists, and investigative journalists in particular, is that any information obtained through a breach of a person’s privacy is strictly speaking illegal, unlawful. Often investigative journalists have said such a breach may be justified in the interest of the public.

One way the courts in Ghana have addressed such a clash of rights, i.e. freedom of expression versus right to privacy, is the use of the doctrine of harmonious interpretation. The Supreme Court of Ghana applied such a doctrine in the case of Justice Paul Uuter Dery vs. Tiger Eye P.I. & Others (Citation2016). The Supreme Court said:

It would be appropriate to apply what the Irish Supreme Court called the doctrine of harmonious interpretation. This doctrine requires that where two constitutional rights come into conflict, for example, the right to privacy and the freedom of the press, the conflict should be resolved in the manner which least restricts both rights. That was in the case of Attorney-General vs. X and others. As to the grounds upon which evidence obtained in violation of human rights guaranteed in the 1992 constitution may be excluded, our opinion is that where on the facts of a case a court comes to the conclusion that the admission of such evidence could bring the administration of justice into disrepute or affect the fairness of the proceedings, then it ought to exclude it.

Recent decisions by the Supreme Court gives the impression that the courts have moved away from the old position that it matters not how evidence is obtained, even if it means stealing it or as it were a breach of a person’s privacy by an undercover journalist. The courts now will consider how such evidence was gathered.

The cases of Cubagee vs. Asare & Ors and Madam Abena Pokua vs. Agricultural Development Bank show that there are some circumstances under which the courts may conclude that the mode of gathering evidence breached a person’s privacy and disregard any evidence flowing from such a breach.

In the Cubagee case, the facts are that in the course of testifying in a land case before the Magistrate, the plaintiff sought to tender in evidence an audio recording of a telephone conversation he had had with one John Felix Yeboah, a superintendent minister, who was representing his church, the 3rd defendant, in the case. The plaintiff claimed the recorded conversation covered matters that were in contention in the case before the court and he wanted to use it to prove that the superintendent minister in that conversation had admitted the plaintiff’s side of the case. The lawyer for the defendant objected to the tendering of the recording on, among other grounds, that it was made surreptitiously by the plaintiff without the consent of the said John Felix Yeboah and therefore in violation of his rights to privacy guaranteed by Article 18(2) of the Constitution. The court held that the secret recording of the minister amounted to a violation of his privacy right.

Pwamang JSC delivering the lead judgment noted that:

… In determining whether impugned evidence could bring the administration of justice into disrepute or make proceedings unfair, the court must consider all the circumstances of the case; paying attention to the nature of the right that has been violated and the manner and degree of the violation, either deliberate or innocuous; the gravity of the crime being tried and the manner the accused committed the offence as well as the severity of the sentence the offence attracts. The impact that exclusion of the evidence may have on the outcome of the case, particularly in civil cases where the establishment of the actual facts is of high premium.

These factors to be considered in determining whether to exclude or admit evidence obtained in breach of human rights are not exhaustive but are only to serve as guides to courts. For instance, where the offence the evidence is offered to prove is a grievous crime committed in a gruesome manner, and the infraction of the accused person’s right by the police was unavoidable, in the absence of countervailing factors, public interest would require that a court leans towards allowing the evidence since it would bring the administration of justice into disrepute in the thinking of the public to exclude such evidence.

The Canadian Supreme Court in as recently as 2017 held that evidence gathered through a breach of a person’s right to privacy is not admissible under some circumstances. In R. vs. Marakah (Citation2017), the court had to determine whether an accused person has a reasonable expectation of privacy in a text message conversation recovered on an accomplice’s device through search and seizure.

The position of the Canadian Supreme court is that in determining whether such a breach is permissible or not, the court will have to assess the totality of the circumstances. In essence, the court has to embark on a journey, do a balancing act. This means that there may be some circumstances where the courts may permit a breach of privacy in obtaining vital information. It is therefore on a case by case basis and not a complete yes or no affair.

Facing the law: Impact and Legal Basis of Evasive Techniques

3. Elsewhere

What happens when journalists breach the law in order to fulfill their watchdog role? The law courts, from a few known examples, are not harsh in their sentences. It all depends on how the judge sees the matter in the light of public interest or the greater good of the majority, and the legal provisions of the particular country.

In Citation2003, BBC News carried a report that its reporter Mark Daly, had been arrested and released on bail for going undercover in a bid to investigate claims of institutional racism in the Greater Manchester Police (GMP). The journalist had been gathering material for a BBC documentary while working as a probationary constable for the GMP. He was arrested on suspicion of obtaining monetary advantage by deception. The Police deplored his tactic, saying public funds had been wasted to train and equip him, and his recruitment had deprived a genuine recruit of the opportunity to join the service.

The BBC defended the reporter saying that the allegations of institutional racism in the Greater Manchester Police Service was a matter of significant public interest. The broadcaster also said monies paid to “our reporter have always been kept in a separate account with the intention of being returned to the Greater Manchester Police after the investigation” (BBC News). Superintendent Martin Harding of the GMP Black and Asian Police Association told BBC Online the results of Daly’s investigations justified his methods (BBC NEWS https://news.bbc.co.uk).

Case No, 2

In England, another journalist was released after being arrested for lying in order to get a job at Heathrow to investigate airport security. The prosecution dropped the case. The decision was backed by the judge (Judge Barrington Black),who said the Crown Prosecution Service’s decision was extremely realistic, He acknowledged that subterfuge was acceptable in matters of public interest. The judge’s comments endorse the idea that it is acceptable to use undercover techniques when it is in the best interest of the public and there are no alternative ways to unearth the information. So while there are potential legal ramifications for undercover reporting, it seems there are some instances where the ends do justify the means. If the information obtained is in the public interest, then undercover journalism can be justified.

In November 1995, Food Lion grocery in North and South Carolina sued ABC in a federal court for more than 5 USD.5million when two of its producers lied on their employment applications during a story on the supermarket selling unwholesome meat. ABC appealed the federal court judgement. The appeal was taken to Circuit Court 4, which awarded only 2 USD damages against ABC and their producers. The insignificant amount of damages could almost imply a tacit acceptance of the techniques employed by ABC.

Ghana specific cases

The work of investigative journalists have had profound influence on people’s perception of corruption. Those who are exposed mount legal challenges to such stories. Many tend to be defamation action. However, recently those who engage in corrupt practices have become bolder with its attendant public support and have been suing for breach of privacy. Often they challenge the investigative technique used as entrapment and abuse of their fundamental right to privacy.

In 2015, Anas and his Tiger Eye crew exposed corruption in Ghana’s judiciary in a two-year sting operation. It is the biggest scandal in the history of Ghana’s judiciary. Public perception about sale of justice was rife but there had been no evidence to back it. A total of 34 judges and magistrates were caught on camera recorded secretly asking for bribes. Ghana set up a judicial committee of enquiry. In the end, over 30 judges and over a hundred judicial staff were found to have breached their code of ethics, engaged in bribery and corruption. They were sacked but no criminal trial was initiated against them.

Three superior judges challenged their dismissal in the Supreme Court of Ghana on grounds of breach of privacy. They lost and appealed to the he Community Court of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), in Nigeria (His Lordship Justice Paul Uuter Dery & 2 Ors vs. Republic of Ghana, suit No. ECW/CCJ/APP/42/16) on grounds that the undercover work breached their privacy rights.

In April 2019, the ECOWAS Court led by a three-member panel also dismissed their action. The court, presided over by Justice Dupe Atoki, upheld the argument by the state of Ghana, to the effect that the secret filming of the Justices was supported by Article 1(1) (b) of the Whistle Blower Act of Ghana and Section 61 of the Data Protection Act of Ghana. It found that the applicants’ right to privacy was interfered with by the secret filming of their activities by Anas, but went further to hold that the interference, being premised on national legislation, is in compliance with the law. The court held that the interference with the applicants’ right to privacy, aimed at exposing the commission of a crime, was justified and necessary in a democratic society. It said the applicants, by their position as judges, are public officers, who receive public funds and in that capacity are accountable to the public and could be subjected to investigation, where there is reasonable suspicion of their involvement in the commission of a crime.

Then also in 2018, a video by Anas titled, No. 12, exposed corruption in African Football particularly Ghana. The exposé captured football officials and referees accepting “cash gifts” and compromising their duties in return. The revelation of corruption in the Ghana Football Association (GFA) led to the lifetime ban of its president, Kwesi Nyantakyi, as well as criminal summons before a Ghanaian court. A lifetime ban of eight referees and a 10-year suspension of 64 other referees were also imposed by the CAF and the Ghana Referees Association. FIFA then set up a normalisation committee that re-organised Ghana Football after a one-year break, leading to fresh elections and a new constitution.

Two of the executives of the GFA (its former boss, Kwesi Nyantakyi and the former FA spokesperson and general secretary, Ibrahim Saanie Daara), who were secretly recorded filed an action at the High Court for a declaration that Anas and his Tiger Eye crew breached their right to privacy, in addition to a defamation action.

In February, 2020, the High Court in Accra delivered its ruling in the matter of Saanie Daara vs. Anas & Another. Saanie Daara who was secretly filmed accepting bribe to influence the selection of a football player argued that the secret recording and subsequent broadcast of same without his consent by the respondent amounted to a breach of his right to privacy under article 18(2) of the Ghanaian constitution. But the respondents argued that the secret recording and publication were justified in the public interest. That by not rejecting the cash offered and further directing the Tiger Eye crew to hand over the money to the intermediary, the applicant assumed ownership of the bribe money and thereby facilitated the corrupt scheme.

The court held that “the recording and subsequent broadcast which are the discussions the respondents held with the applicant, neither constituted a violation of his rights nor a violation of his communication. The recording and broadcast qualified as an exemption in public interest and on public policy grounds”. It further said the meeting between the applicant and respondents in which applicant was recorded was not a private communication. The court also said although Saanie Daara’s organisation was private in nature, it performed public functions and that the applicant breached his own organisation’s code of ethics and that of FIFA by putting himself in a compromising situation.

In 2017, Manasseh Azure Awuni’s investigative series titled, “Robbing the Assemblies” led to the cancellation of a 74 USD-million government contract for the supply of waste bins to district assemblies in the country. The investigation revealed that the Ministry of Local Government did not need the bins it was procuring, and that the contract sum had been inflated by at least 31 USDmillion.

These exposés evidently exposed high corruption in places where many people knew corruption existed but needed the evidence to back it. The evidence collected not out of ill-will but with the public interest in mind, became the basis for the law court to say there was no wrongdoing on the part of the journalists for using the only means available to dig up the scandals and put them in the public domain, In this case, the public interest superseded the rights to privacy of the individuals involved in these criminal acts.

Social-Cultural underpinnings

Cultural values and norms influence corruption in society in diverse ways. Multi-dimensional efforts are often initiated to fight it, including the exposés of investigative/undercover journalists and the media. Even though there are standard definitions of corruption, which is not within the scope of this paper, these “should not lead us to presume that they mean the same thing or functions in the same way everywhere. Not only are meanings and practices of corruption shaped by cultural context, they are also revealing windows onto other aspects of social life” (Smith, Citation2018, p. 7). Different societies thus have different attitudes to corruption.

There are also different customs; in some instances, a “thank you” in the form of a gift for a service for which the person has already been paid with a salary, is an expression of courtesy and appreciation. Elsewhere it is considered corruption, Štefan Šumah (Citation2018) notes.

According to Osei-Hwedie and Osei-Hwedie (Citation2000), in Nigeria, corruption is regarded as a “way of life”; whiles in Sierra Leone, there is talk about a “culture of corruption”. Smith (Citation2018, p. 4) estimates that, the pressures that wealthy and powerful people in Nigeria experience to behave corruptibly—“pressures that come from kin and community, friends and peers, and even from society at large”—push them to accumulate enough, by fair or foul means, to share generously with their clients. Re-echoing this sentiment, Olivier de Sardan (Citation1999) and Pierce (Citation2016) emphasise the extent to which corruptible behaviours are commonly undertaken to fulfill obligations to kin, community, and networks of patron-clientelism. These scholars agree there is a “complex intersection of state bureaucracy and face-to-face sociality and its role in creating opportunities for corruption” in Nigeria as in Ghana owing to the cultural values of the people who see nothing wrong with the phenomenon.

In Kenya, acknowledging how cultural values influence corruption and society’s perception of it, Melgar, Rossi and Smith, (Citation2010 as cited in Douglas Kimemia, Citation2013, p. 55), observe that “corruption encourages a cultural tradition of gift giving, which in turn generates a culture of distrust towards public institutions”. Deducing from the reciprocity of gift giving, corruption definitely will have a meaning different from its political, economic, corporate and intellectual definitions that will also make fighting it a difficult task.

The nature and cultural causality of corruption in Ghana is not any different from what obtains in Kenya and Nigeria. A study by Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (Citation2016) on how cultural underpinnings of Ghana contribute to public sector corruption found that the country, and to a large extent Africa, has a highly collectivist society and blames its high public sector corruption on its collectivist culture. The research established that Ghanaian culture is rife with principles that provide fodder for corruption. It refers to various proverbs and aphorisms which culturally promote togetherness and forge alliances with one another but when transported into private and public transactions, they have the tendency to promote corruption. This is because these cultural values allow for rules and due processes to be side stepped and even compromised. The study pointed to proverbs largely used by the Akan ethnic group, the most dominant ethnic group in in the country, as being highly predisposed to using proverbs in much of their daily oral communication. The following are example of proverbs as collected by Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (Citation2016) in their study

Proverb: Dua bata bo), ne twa ye twa na.

Literal translation: It is difficult to cut a tree which is too close to a rock.

Connotation: When trying to cut the tree you will hit the rock with your cutlass and dull the blade. When a close friend hurts you, you will not or should not forsake them; don’t leave them to their own destiny or deal with them harshly. You will not be able to jettison them because of your feelings for them.

Proverb: Benkum dware nifa, nifa dware benkum

Literal meaning: The left hand baths the right hand, whilst the right also baths the left hand. You scratch my back, I scratch yours

Connotation: This proverb suggests that each one should be their brother’s keeper even in times of trouble. It is usually cited when people want undue favour from public officials or when an official wants to do something where it needs the assistance or collaboration of others.

Proverb: Akok) baatan tia ba na)nkum ba

Literally: The hen steps on the chick but does not kill it

Connotation: Even if someone engages in unethical or corrupt act, it is better to caution him rather than expose him to be fired.

From the above discussion of proverbs, it is evident that the collectivist culture Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (Citation2016) assert is one sure reason why many in Ghana and perhaps Africa disapprove of whistleblowing as it disrupts unity.

The Ghana Police Administration appears to agree withthe findings of Yeboah-Assiamah et al. (Citation2016). A Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCOP) in an interview with Ghana’s leading private radio station, Joy FM, on why the police is always topping the corruption perception index in the Afrobarometer survey said:

A bribe is something that people look at in terms of money. What about nepotism, old boyism etc? I won’t fault the Afrobarometer report on corruption in the police service but I don’t agree with it. We are all sometimes embarrassed by the behaviour of some of our men on the road. Lots of our proverbs encourage corruption. Afrobarometer should look again. Our culture of reciprocity also encourages corruption (Joy FM, 11 December 2014).

The legal and social definitions of corruption appear to be at variance with cultural values and norms in developing countries, where the institutions are not functioning properly, thereby causing systemic failures and corruption.

Added to this is the political rhetoric of asking evidence when political leaders or powerful people in society are alleged to be engaged in corrupt practices. Until a documentation is provided as proof, such people go unpunished and it remains a mere allegation. This will mean investigative journalists in Africa and Ghana in particular will have to go that extra mile to prove the existence of such acts. This may not necessarily address the concerns of those who hold the belief that it is culturally acceptable to accept gifts from people to whom certain favours have been done.

4. Research methodology

The study relied on secondary data mainly from the works of Anas Aremeyaw Anas of Tiger Eye P.I. The data were selected from a list of 37 exposés spanning a 14-year period—from 2005 to 2018. The systematic random sampling technique was used to sample the eight exposés from eight years that were also randomly sampled.

The exposés included:

Eurofood Scandal (June 2006)

Soja Bar Prostitution (September 2007

Inside Ghana Madhouse (January 2010)

Ghana Gold (2011)

Spell of the Albino (Carried out in Tanzania in 2011)

Ghana’s Sex Mafia (2014

Ghana in the Eyes of God (August 2015)

Bad Cops (2017).

There had been a groundswell of criticism against the exposés of undercover journalists in the country about their methodology in exposing corruption among public and civil service officials as well as business executives and their organisations. Infringement on the right to privacy of the individual has always been the basis of the criticisms.

4.1. Data analysis and findings

All the eight exposés of Anas’ in this study had an average screening time of 48 minutes. Each of them contained one or more infractions including impersonation, invasion of privacy—filming and recording without the consent of the persons being investigated. In the case of the Eurofood exposé, the undercover journalist had to seek employment with the confectionary manufacturer in order to participate in activities as an employee and insider, and then take pictures of maggot-infested flour that was being used to produce biscuits.

The glaring unethical conduct was to have lied as a job seeker, and to have secretly taken pictures of the flour. But that was the only means he could use to get access to the factory premises and then get to the bottom of the matter—that Eurofood was doing something terribly unacceptable in the food industry. Reporting to the authorities and producing the pictures as evidence was a duty the journalist owed the society in his watchdog role.

The same method was used in exposing all the unprofessional things and poor treatment of patients at the Accra Psychiatric Hospital when Anas faked lunacy and was admitted to the facility for treatment. Again if recording and filming happenings at the hospital without the authorities’ permission was unethical, the method did help him expose wrongdoing there. Corruption in the judiciary and the police service was exposed using subterfuge. Nobody’s private life was interfered with even though some people suffered reputational damage when they were found to have abused their positions as public office holders and exposed for it.

Similarly, cases cited involving other journalists contained the use of methods considered unethical and illegal such as impersonation and secret recording.

5. Discussion, suggestions and conclusion

The findings from the data uphold the claims that investigative journalists in Ghana use subterfuge to obtain information to expose corruption, and Anas Aremeyaw Anas and Manasseh Azure Awuni are no exceptions. All eight of Anas’ exposés that were studied were found to have been the result of surreptitious methods. Going by the recommendations of the code of ethics of investigative journalism of the International Centre for Journalists, Berlin, and that of IPSO and OFCOM in the UK, subterfuge and covert means were the only means by which the journalists could get access to information they badly needed for their exposés.

The literature is replete with cases of impersonation, lying, sting operations, ethical infractions and invasion of individual privacy by undercover journalists in Nigeria, Britain, US, Latvia, India, Pakistan and many other countries across the globe in order to expose wrongdoing in society. Public interest and the right of the people to know the truth about a situation have always been used as the defence for the use of evasive methods for investigative reporting. Inasmuch as individual rights count very much, the rights of the larger citizenry count more, especially where issues of significant public interest mean the rights of the majority should supersede those of the individual.

The Ghanaian society’s norm of togetherness, brotherliness, collective interest and unity surely undermine investigative journalism as the journalists are seen as breaking the unity, exposing a bread winner, depriving a family, a community of leaders when they are prosecuted. It is the reason many do not see anything wrong with bribe taking, be it a gift to fast track or side step due process. It is considered as a normal “thank you” as opposed to say the West, where principles of gifting are highly spelt out with limits. It is also the reason why many in Ghana and Africa decry the methods used although the evidence obtained through such means vindicate the action as being in the public interest.

The society may appreciate the work of investigative journalists if they understand what consti-tutes public interest and the limits of their rights to privacy. Many will even appreciate it better, when they come to the realisation that corruption denies them of their basic right such as right to food, shelter etc.

Investigative journalists will need to do a serious balancing act when using various evasive techniques as the only means to get to the heart of an issue. Blackmail and entrapment are legitimate worries and or concerns. Although, sometimes people confuse sting operation with the issue of entrapment [participating in and perhaps instigating wrongdoing usually employed by security agencies like the police].

This paper would like to suggest that journalism training institutions in country should give the teaching of investigative journalism a greater boost.

Whilst some have justified the methods used by undercover journalists in the name of public interest, further studies or debates need to be conducted as to how far one can go using the public interest justification. Does the public interest provide unlimited or unqualified licence for undercover operations at all times, when the circumstances are such that the undercover journalists cannot obtain the information in any other way than breaching the privacy of the individual?

Another crucial issue that will require further studies is the role of technology in the elasticity of public spaces. Advancements in information and communications technologies are shrinking privacies and shining light on previously hidden spaces. It has become easier to access secrets, intimate details of people, including DNA sequence, precise location and reading habits, asserts Fakhoury (Citation2012). Such tools will be viable to both investigative journalists and any other person. For instance, whistleblowers can use anonymous web services to send information to investigative journalists. Fakhoury notes what will be fundamental is “to demand that privacy be a value built into our technology.”

Thus, research and/or debate are needed on the issue of shrinking private spaces and consequential exposures of previous secrets. When those who naïvely and jubilantly perform so-called private acts in front of hidden cameras that inherently expand public spaces, one wonders what becomes of the privacy allegedly breached. This and many other issues call into debate the public interest versus right to privacy when undercover journalists dare make enemies by exposing corruption and wrongdoing in society.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samuel Appiah Darko

Samuel Appiah Darko is a lecturer with the University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA) teaching and researching into media law, security and public interest journalism. He has written extensively in these areas.

He has over a decade of experience in journalism working for both foreign and local media organisations, and across many media platforms including TV, radio and online for the BBC World Service.

Sammy is an associate at the private law firm, Cromwell Gray LLP in Accra. His areas of practice include litigation-civil &criminal, corporate & commercial law, and Intellectual Property law.

References

- Alesu-Dordzi, S. (2018). “Investigative Journalism: The tension between privacy and public interest”. Available at: https://www.myjoyonline.com publicized on 12- 06-2018. Accessed on 28 September 2018

- Almania, A. (2017). Challenges confronting investigative journalism in Saudi Arabia. A paper presented at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC17). Johannesburg, South Africa. https://gijc2017.org

- BBC News (2003, April 15). “BBC reporter released”. BBC [Online] https://news.bbc.co.uk

- BBC. (2018). BBC.COM. https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/45348750).

- Bingham, J. (2011). ‘Elliot Morley jailed for cheating his expenses’. The Telegraph. [Online]. May 20, 2011. The Telegraph. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/mpsexpenses/

- Brooke, H. (2010). The silent state: secrets, surveillance and the myth of british democracy. William Heinemann.

- Ceferin, R., & Poler, M. (2018). Journalism in the public interest: Definitions and interpretations in journalism ethics and law. Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ljubljana.

- Chernow, S. (2014). ‘The ethics of undercover journalism: Where the police and journalists divide’. Ethical Journalism Network. Ethical Journalism Network. https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/the-public-interest. Accessed on June 21, 2018.

- Coleman, B. E., & Dann, E. C. (2016). ‘Privacy and the public interest’, Empedocles: European Journal for the Philosophy of Communication, 7 (1), 57–19. https://doi.org/10.1386/ejpc.7.1.57_1

- Committee on Privacy (1972). Rights to privacy in ghana. Parliament of the Republic of Ghana.

- de Burgh, H. (2000). Investigative journalism: Context and practice. Routledge.

- de Burgh, H. (2008). Investigative journalism. Routledge.

- Fakhoury, H. M. (2012). Privacy and technology can, and should, co-exist. The New York Times.

- Frost, C. (2011). Journalism ethics and regulation. 3rd Edition (pp.10). Harlow: Longman.

- Hill, S., & Lashmar, P. (2014). Online journalism: The essential guide. Sage

- Horrie, C. (2008). ‘Investigative Journalism and English Law’. In H. de Burgh (ed.) Investigative journalism. (pp.114). London, UK: Routledge.

- Houston, B. (2009). The investigative reporter’s handbook: A guide to documents, databases and techniques. 5th Edition. Bedford Books.

- Hunter, L. M. (2012). ‘The Global Investigative Casebook’. In Lee Mark Hunter (Ed.,), UNESCO series on journalism education. (pp.50). UNESCO.

- Insider, C. N. (2012). 10 most courageous undercover journalists. www.careernewsider.com. http://www.careernewsinsider.com/10-most-courageous-undercover-journalists/

- Institute, S. P. (2016), Definition of Kant’s duty-based moral theory. Seven Pillars Institute. Available at: https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/morality101/Kantian-duty-based-deontological-ethics. Accessed on May 21, 2018.

- Joy, F. M. (2014, December 11). Interview with DCOP kofi boakye on afrobarometer’s corruption perception index. Joy Fm. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/joy997fm/photos/. Accessed on May 9, 2020.

- Kimemia, D. (2013). ‘Perception of public corruption in Kenya’. African Journal of Governance and Development 2(2)

- Kovach, B., & Rosentiel, T. (2014). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. Third Edition. London Routledge

- McQuail, D. (2005). McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory. Fifth Edition. Sage Publications

- Melgar, N., Rossi, M., & Smith, T.W. (2010). The perception of corruption in a cross-country perspective: why are some individuals more perceptive than others? Economia Applicada, 14(2). [Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-80502010000200004]

- Mustapha-Koiki, A. R., & Ayedun-Aluma, V. (2013). ‘Techniques of investigative reporting: Public’s right to know and the individual’s right to know’. Humanities and Social Sciences Review, University of Lagos.

- Mustapha-Koiki, A.R, & Ayedun-Aluma, V. (2013). Techniques of investigative reporting: public’s right to know and the individual’s right to know. In Humanities and social sciences review, 2 (2),543-552. Lagos: University of Lagos.

- Nazakat, S., & Media Programme, K. A. S. (2010). Investigative Journalism Manual. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. www.investigative-manaual.org

- Olivier de Sardan, J.P. (1999). A Moral Economy of Corruption in Africa? The Journal of Modern African Studies, 37(1), 25-52. [Available Online at: https://www.researchgate.net/journal/0022-278X]. [Accessed on April 9, 2020].

- Ongowo, J. O. (2011). Ethics of investigative journalism: A study of a tabloid and a quality newspaper in Kenya. A Master of Arts thesis submitted to the Institute of Communication studies. University of Leeds.

- Osei-Hwedie, B. Z., & Osei-Hwedie, K. (2000). ‘The Political, Economic, and Cultural Bases of Corruption in Africa’. In K. R. Hope & B. C. Chikulo (Eds.). Corruption and Development in Africa. (pp. 40–56). Palgrave Macmillan

- Pierce, S. (2016). Moral economies of corruption: State formation and political culture in Nigeria. Duke University Press.

- Sanders, K. (2003). Ethics and Journalism. SAGE.

- Smith, D.-J. (2018). “Corruption” and “Culture” in Anthropology and in Nigeria” [Online] 2018. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6450070. Accessed on May 9, 2020.

- USlegal.Com (2017, August, 15). Legal Definitions and Legal Dictionary. https://USlegal.com

- Waisbord, S. (2001). ‘Why democracy needtigative journalism’. Electronic Journal of the US Department of States 6 (1), 14-17. Global Issues. http://www.ait.org.tw/infousa/enus/media/journalism/docs/ijge0401.pdf. [Accessed, 27 September, 2018]

- Ward, J. S. (2006). The Invention of Journalism Ethics: The Path to Objectivity and Beyond. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Wilson, J. (1996). Understanding journalism: a guide to issues. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Asamoah, K., Bawole, J. N., & Musah-Surugu, I. J. (2016). ‘A Socio-Cultural approach to public sector corruption in Africa: Key pointers for reflection’. Journal of Public Affairs, 16(3),279–293 https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1587

- Šumah, S. (2018). “Corruption, Causes and Consequences”. In: Vito Bobek (ed.), Trade and Global Market, IntechOpen. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.72953.

Case law References

- Ackah vs. Agricultural Development Bank (Ruling) (J4/31/2015) [2016] GHASC 49 (28 July 2016).

- Cubagee vs. Asare and Others (NO. J6/04/2017) [2018] GHASC 184 (28 February 2018) & Unreported Judgment of Supreme Court dated 20th December, 2017 in Suit No CA/J4/31/2015. Supreme Court of Ghana (SCG).

- Justice Paul Uuter Dery vs. Tiger Eye P.I & ORS 2016 SC (J1/29/2015) [2016].

- R. v. Marakah, 2017 SCC 59, [2017] 2 S.C.R.

Web References

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35037318. Judges scandal. Expose involving bribe taking judges and magistrates in Ghana. BBC.COM. Accessed 7 May, 2020

- http://prod.courtecowas.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/JUD_ECW_CCJ_JUD_17_19.pdf ECOWAS Court Ruling on appeal by three Ghanaian Justices. Community Court of Justice-CCJ.

- https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/46037427 Corruption scandal in Ghana Football Association and Africa Football. BBC.COM. Accessed May 7, 2020

- https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Suspended-PPA-boss-charged-granted-self-recognisance-bail-776698. Manasseh Awuni’s work on the PPA boss. GHANAWEB.COM. Retrieved on May 9, 2020.

- http://www.gaccgh.org/details.cfm?corpnews_scatid=37&corpnews_catid=7&corpnews_scatlinkid=287#.XpyqIC10dp9). Manasseh Awuni’s documentary on waste bins. Ghana Anti-Corruption Coalition (GACC). Accessed on May 9, 2020.

- https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/national/court-dismisses-saanie-daaraaes-privacy-case-against-anas/ Ibrahim Sannie Daara vs Anas Aremeyaw Anas & 2 ORS Suit no: HR/00902018.