Abstract

To avoid “renoviction”, a public housing company in a stigmatized neighbourhood in Sweden (Hammarkullen) decided to renovate its rental apartments suffering from neglected maintenance using a “zero option” with regard to rent increase. The present article is based on content and thematic analysis of tenant interviews, documents and mass media articles. It describes the tenants’ views on this initiative and its consequences for them. The results show that they welcomed the “zero option”, but were dissatisfied with how it was designed. It did not live up to the maintenance responsibility for the entire apartment that, according to established practice, housing companies always have. It also did not solve the basic problems experienced by the tenants. They had their own ideas about how a “zero option” could have been designed to live up to their expectations. With an “action net” or “connective actions” approach, the housing company, in close collaboration with the tenants, could have succeeded in codesigning a “zero option” for renovation, with the potential to deal with environmental as well as social, economic, technical and other aspects.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The present article discusses a renovation of neglected rental apartments in Sweden, using a “zero option” with regard to rent increase. It describes the tenants’ views on this initiative and its consequences for them. They welcomed the “zero option” but were dissatisfied with how it was designed. Had a different dialogical approach been implemented, the housing company, in close collaboration with the tenants, could have succeeded in codesigning a “zero option” for renovation, with the potential to deal with environmental as well as social, economic, technical and other aspects.

1. Introduction

“Zero energy initiatives” in housing renovation have existed for quite a while, but “zero rent options” are rare. This implies that renovation will lead to a certain number of tenants being forced to move when rent increases are too high for middle- and low-income earners. The present article aims to describe an experiment involving a “zero rent option” in Sweden, focusing on tenants’ opinions about the initiative (the information they got; the dialogue; how finances were presented; their influence on the renovation design; and their own thoughts about the renovation). The work was carried out as part of a research project called Learning Lab Hammarkullen: Codesigning Renovation.

1.1. Background and the state of the artFootnote1

Renovating residential buildings with rental apartments by considering the tenants living in them may not often be property owners’ first priority, however, tenants have held a fairly strong position in Sweden in this regard. There has been established practice concerning what maintenance tenants are entitled to, and this system is transparent to them. There has also existed legal support to deal with tenants’ complaints. But Sweden, like many other parts of the world (see Gertten’s documentary film Push),Footnote2 is undergoing a liberalization wave, and rental housing is increasingly becoming a commodity on the housing market. The criticism of this development offered by academics in Sweden is strong, some researchers going so far as to claim that “the current form of displacement (through renovation) has become a regularized profit strategy, for both public and private housing companies” (Baeten et al., Citation2017, p. 1).

It should be added that Sweden had a different starting point than most of Europe, in that it had public instead of social housing. Public housing companies in Sweden, strongly linked to the Social Democratic Party, established a practice of protecting all of their tenants, something many private property owners also lived up to. But the 1990s brought with it major changes. From being one of the most equal countries in the world with regard to income, Sweden had, at the end of the 1990s, an income differentiation equivalent to what it had at the beginning of the 1970s (Lindberg, Citation1999, p. 313). Just as in the rest of Europe, where “since the early 1990s, the housing sector has been radically reformed in accordance with neoliberal ideology, with far-reaching consequences for the increasingly polarized poor and rich” (Clark & Hedin, Citation2009, p. 173), Sweden also changed: “The Million Programme, then one of the main vehicles to install universal welfare in Sweden, has now become one of the main vehicles to actively work against welfare” (Baeten et al., Citation2017, p. 468). Parts of these housing areas are now being bought and sold by international investment companies that own them for a few years, their main interest being to make money.

It has long been known that housing in Sweden is suffering from neglected renovation needs, and much of this problem concerns the Million Programme areas. The case study area of Hammarkullen is one such neigbourhood, located in the northern part of Gothenburg on Sweden’s west coast. The majority of immigrants in Sweden live in these areas. In 2008, it was stated that 800,000 of the rental apartments would need to be renovated within ten years (Industrial Facts, Citation2008), but only a portion of them have been dealt with. Thus far, neither the government nor the municipalities have agreed to subsidize the renovations, despite critics’ argument that rental revenues should have been saved for renovation. Research shows that the pace of renovation certainly needs to increase, but also stresses that, if renovation is carried out as done hitherto, there is a great risk of increasing societal inequity by increasing rent (Mangold et al., Citation2016).

Although the pace of renovation is insufficient compared to the needs, a wave of renovation of rental apartments has occurred during recent years. This has resulted in a major protest movement among tenants against the high rents caused by renovation. Rent increases of 30–60% are common, and there are even examples of 100% increases in rent after renovation. Studies conducted by authorities (Boverket, Citation2014) and academic studies have consistently pointed to these problems. For example, Bergenstråhle and Palmstierna (Citation2017) investigated how many tenants would end up with a household income below a reasonable standard if renovation were to continue as it has begun. They found that, with a rent increase of 50%, one third of tenants would be forced to move. And there are very few cheaper alternatives left, meaning either that renovations force people out onto the street or that municipalities subsidize their living costs—which they do more and more infrequently in Sweden these days (Westin, Citation2011).

In parallel to these circumstances, a huge housing shortage has developed in Sweden due to the low level of construction, reaching the point of being an obstacle to economic growth. According to the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, the country needs to build 600,000 residences before 2025. Moving to a new building is, thus, not a feasible alternative for those who are forced to move because of renovation. One result of this withdrawal of responsibility for housing issues is that citizens’ trust in the Swedish welfare system is being broken (Polanska & Richard, Citation2019). Just as in many million program areas, this is a major problem in Hammarkullen (Hansson, Citation2018).

Inspired by the British Staying Put movement (Lees, Citation2014), citizens in the biggest cities in Sweden have formed joint protests against renovation plans and support each other in confronting property owners (Thörn et al., Citation2016). In some cases, they have succeeded in changing the plans, but in most cases the tenants have lost the fight. The problems resulted in the government appointing a Tenant Investigation (Citation2017), the aim of which was to increase tenants’ power over renovations. Among other things, the government wanted to change the present circumstance, which is that tenants lose 98% of the cases in court. The investigation suggested several modified practices and changes in law, which are awaiting political decisions, but thus far the investigation has not led to any actual improvements.

The circumstances for tenants are the same all over the country, even in the medium-sized cities, all of which have stigmatizedFootnote3 housing areas from the 1960s and 1970s—with buildings in need of renovation. Research on the middle-sized city of Landskrona describes the actual development as a watershed in Swedish housing politics and claims that it has changed:

(1) the nature of gentrification processes in Scandinavia – from gentle to brutal; (2) the shift in viewing affordable housing as a problem, rather than a solution; and (3) the possible introduction of “renoviction” in Sweden (Baeten & Listerborn, Citation2015, p. 249).Footnote4

The opposite end of the political spectrum in Sweden agrees about the seriousness of the housing situation, but sees solutions in market adaptation rather than in increased government influence:

It is shown that when there is a housing shortage, this system [rent regulation] creates economic incentives for increasing the standard of apartments, even if this reduces total welfare. The result can be that quality is increased more than in a market system, and that it can increase gentrification compared to such a system (Lind, Citation2015, p. 389).

The policy proposals concern building enough to meet the housing demand, which would press down the rents on newly built units and increase quality owing to competition; they also concern building cheap housing for those with low incomes—thus introducing some kind of social housing in Sweden:

Many of the problems discussed above would be reduced if the housing supply increased, especially housing designed for groups with somewhat lower incomes (Lind, Citation2015, p. 403).

It is part of this policy proposal to introduce completely free-market rents instead of statutory rental negotiations between the parties, which Sweden has today. It is claimed that increased housing production in combination with market rents will press down rents in stigmatized neighbourhoods, as the apartments there would otherwise risk being left empty. This would thus increase the housing quality there as well, as there will be pressure to better maintain and renovate these neighbourhoods.

Regarding renovation, this opposite end of the political spectrum maintain that it is viable if tenants are offered different renovation options. It has become “acceptable practice” in the property owner business to offer three such alternatives, often called Mini, Midi and Maxi. In one study of this practice, it was stated that “most tenants chose the Mini alternative which meant that they could afford to stay” (Lind et al., Citation2016, p. 1). Yet even the Mini alternative actually implied a rent increase of around 10%, which is quite high for many tenants, so how could everyone stay?

The net rent increases correspond to a necessary income increase from 3 to 12% of the household’s disposable income. This necessary increase can be even higher for some households. Still, the households were able to cope somehow with these rent increases, probably rearranging and cutting other costs. Home is an important place (Ibid, 8).

Thus, some tenants remain at a cost to their disposable income. This plays a major role for low-wage earners, the people who primarily populate the neighbourhoods now facing renovations. This has also societal consequences:

From a long-term perspective, it is important to see how the rent increases affect who will be able to rent an apartment. The company demands that new tenants have an income before tax of at least three times the rent. With the current rent (€640/month) the required income is €23,000 before tax per year. After the renovation, the rent will be €722–834/month and the income demanded would then be €26,000–30,000 per year. This means that when an apartment becomes vacant, the current tenant will be replaced with tenants that on average have higher income than the tenants moving out. The number of apartments available for households with lower incomes is thereby reduced by the renovation, especially as the company can raise a Mini renovated apartment to a Midi renovation when the apartment is vacant (Ibid, 8).

There is also research that broadens the perspective, going beyond the economy and viewing a rental housing unit as the home that it is, and the residential area as people’s emotional and relational place of residence. This research claims that renovation processes carried out without respect not only increase the costs for the remaining inhabitants, but also mean that their “links to past experiences are destroyed, and memories are no longer as easily conjured” (Pull & Åsa, Citation2019, p. 13).

From a societal perspective, there is therefore reason to carefully consider how both new production and renovation of housing are carried out. Some research has been done that makes such considerations. Kunttu et al. (Citation2017) investigated how the economic and social impact of affordable housing can be assessed in a practical manner and developed a framework that:

supports holistic assessment and increases the capability to handle multifaceted situations. It also assists in making decisions on whether desirable intangible impacts of investments can be achieved by reduced rent. Moreover, the structured assessment process will enhance the transparency of decision-making (Kunttu et al., Citation2017, p. 91).

The framework thus improves the quality of choice, guiding it towards the most attractive investment option from both the owner’s and tenant’s perspective. However, they point to one problem with this type of evaluation, which is that the necessary data are not normally collected. Thus, identifying the mutual interests of property owners and tenant organizations is needed for such evaluations to be made.

Apparently, in relation to this state of the art, there is a significant amount of research about the risk of tenant displacement in connection with housing renovation. There is, however, no research on “zero rent options” and what such renovation may imply for tenants. The reason is probably that few such experiments have been conducted.

1.1.1. A public housing company renovates with a “zero option”

All of this is important background to the empirical studies in the present article. In October 2015, a public housing company decided to buy a property with 890 rental apartments for €47 million from a private owner in the so-called exposed and stigmatized neighbourhood of Hammarkullen (Figure ). The property had changed private owners several times previously, and maintenance had been largely neglected. It was municipal politicians who made this decision, and hundreds of tenants fought by demonstrating and attending meetings to make it happen. There was a heated battle in which liberal politicians wanted other private owners to take over, but the side expressing more socialist preferences eventually won.

Figure 1. Hammarkullen was built during in the period 1968–1970 and is among the one million homes constructed during the 1960s and 1970s in Sweden (The Million Programme). The photo shows the buildings containing the 890 apartments discussed in the present article and owned by the public housing company Bostadsbolaget. In total there are 8,200 inhabitants in Hammarkullen, living in 2,200 rental apartments all owned by the same public company, as well as in 600 private row houses and villas. Photo: Albin Holmgren

A little later, in April 2016, at a public seminar organized by the Swedish Union of Tenants, the CEO of the public housing company surprisingly declared that these houses would be renovated with a “zero option”, thus the tenants would be able to choose a renovation alternative without a rent increase. This came as a surprise even to the chairperson of the board of the public housing company, who sat in the audience, but was welcomed by him as well. The reason for this decision was that the politicians in the municipality decided that no tenant should be forced to move because of renovation (Pennypodden, Citation2018). The housing company would thus break new ground and do a major renovation of the rundown properties without increasing the rent for those who choose that option. What would that entail for the tenants? The present article will shed light on what it looks like now, four years later, answering questions about how tenants were informed about the process; their feelings about the dialogue; how financial issues were presented; whether they could influence the renovation design; and whether they had their own ideas about how the renovation could be done and what these ideas looked like.

1.2. Materials and method

Learning Lab Hammarkullen was a transdisciplinary research project (Carew & Wickson, Citation2010; Posch & Scholz, Citation2006) carried out 2014–2019 and led by the Department of Architecture & Civil Engineering at Chalmers University of Technology. The Union of Tenants was the driving actor in the research project and a cofunding “practitioner”, together with the public housing company Bostadsbolaget and other actors, who participated in the frequent “learning meetings” but were less active in shaping the project.Footnote5 The participatory research project aimed to generate knowledge about how tenants can become involved early in renovation processes, and how they can become involved in actual decision-making. The project was thus concerned about a shift in power to the tenants’ advantage and how that could be implemented.

The present article is based on studies carried out in October-November 2019 when interviews (Kvale, Citation1996; Morgan, Citation1996) were conducted with five tenants living in the buildings that are being considered for renovation with a zero option, or who were board members for the tenants’ association of these buildings. They were selected by the present author based on their involment in the process over time and the responsibility they assumed for bringing in knowledge and opinions from all affected tenants. The reason for adding the five interviews to the previous empirical material was to gain knowledge from the tenants about the zero alternative, as it had not been discussed a great deal earlier. The empirical material also consists of a total of 243 photos from 30 tenants collected by the Union of Tenants to use in rent negotiations (Union of Tenants, Bredfjällsgatan & Gropens Gård, Citation2019). Interviews in the mass media have also provided information for the research.

The article is also based on a large amount of empirical material collected during the six years the research project was going on. This material has been described in a previous article discussing dilemmas that seem difficult to overcome when tenants are given more power in renovation processes (Stenberg, Citation2018). It consists of 22 recorded semi-structured qualitative interviews concerning the consultation model for renovation that was used. Two types of actors were chosen for interviews: employees and elected representatives of the Union of Tenants (14 persons) and employees in public and private housing companies (8 persons). Moreover, a course in consultation was designed based on lessons from the interviews, for explicit use in a suburb like Hammarkullen. The course was formed to appeal to tenants and empower them, and for this reason role-play was introduced. It was tested with eights tenants and six trainers/role players and filmed for the purpose of analysis and learning. Methods used in the empirical analysis include content and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Schreier, Citation2012; Vaismoradi & Bondas, Citation2013).

1.3. Theoretical framework

The empirical material has been analysed using theories of actor collaboration, power and innovation. Anheier et al. (Citation2019) theories concering “connective” actions has been helpful, focusing on bringing formerly detached or isolated actors together and establishing a link to target groups. In that context, it has been valuable to conduct the analysis using Latour’s (Citation2005) actor-network theory, which describes how power develops in relation to building relationships and suggests that an important agent in this institutional change may be the opening of “black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981). The great interest in relations between actors has also led to Czarniawska’s action net theories (Czarniawska, Citation2004).

1.4. Results

Two years after the property purchase of the apartments and 1.5 years after the announcement was made about renovating the property with a “zero option”, the housing company had finished their inventory of the building and decided how they intended to renovate. This process was internal to the company and was not made transparent to the Union of Tenants. The housing company decided to start with one building with 125 apartments and to learn from that experience. In November 2017, they invited these tenants to an initial information meeting. Around 17 tenants came, most of them engaged in the local Union of Tenants. According to the interviewed tenants, the reason so few came depended on a variety of factors. Many do not speak Swedish, and because the information from the housing company was provided in Swedish, it did not make sense to come. There are also many who rent illegally, on a second-hand contract. In addition, there are people who are vulnerable in different ways and do not have enough energy to come or cannot speak for themselves. Last but not least, many people generally distrust housing companies after many years of lack of maintenance and do not think it will get better this time (Hansson, Citation2018). This is why organized tenant influence is so important in stigmatized housing areas.

At the meeting, the tenants were informed about the renovation plans. Pipe replacement must be done, according to the owner, and therefore the bathrooms had to be completely renovated. Because such replacement is not considered a “standard raise” according to established practice in Sweden, the housing company cannot raise the rent in connection with such renovations. It is therefore regarded as maintenance, for which funds must be taken from the rent or acquired through loans. Thus, as presented at the meeting, those who choose the “zero option” would get a bathroom with new sealing layers and with the same type of surface layer they had before—plastic floor and wallpaper—and re-use of interior elements such as toilets and sinks.

In most renovations in Sweden, housing companies do not offer such a choice to tenants. Instead, they force them or push through a standard increase when replacing pipes. This is done for a variety of reasons. One reason is to make money. Property owners can make money because the cost of standard raising materials (tiles and new bathroom porcelain) is lower than the rent increase they can get in the rent negotiation with the Union, or through court if the issue is decided there. In addition, when a property has been bought and sold by private investors with a profit interest, there is usually no money saved for pipe replacement. This implies that, in the event of a changed piping system, the housing company will try to get the tenants to pay for new bathroom floor and wall materials, even though this is not tenants’ responsibility, according to established practice in Sweden.

It was just such a situation, with no maintenance fund, that the public housing company was in when it bought a property from a private owner who had owned it mainly to make a profit. Thus, they needed to renovate but did not have sufficient funds available. On the other hand, it is common in Sweden not to have any maintenance funds, as national politicians have introduced taxation of such funds. Housing companies thus generally manage their portfolios by borrowing for renovation or redistributing within the stock. Hence, lack of funding for maintenance does not actually relieve them of their responsibility, which is to maintain properties without increasing rent. The current public housing company has 24,000 apartments and the public business group of which it is a part has 70,600 apartments. They have a significant profit after tax and low leverage ratio.Footnote6

There is another reason why property owners push tenants to raise the standard: They want to attract the middle class to their properties. For them, this is partly because that group is more likely to pay a standard increase than the working class or people in need of social support. Profit reasons are simultaneously paired with political causes, as there is a majority who believe that stigmatized residential areas will lose their stigma if the composition of residents change. It has therefore become legitimate for property owners, both private and public, to strive to replace tenants with low income or on social welfare with others who are better off. However, there is no plan for where those with less income should move. With this as our background, we will listen to what the tenants in Hammarkullen had to say about the “zero option”, as presented to them.

1.4.1. What the tenants said

The overall picture the tenants gave of the process was that it had been extremely slow and lacking enthusiasm. This is surprising, considering that the public housing company was trying an innovative renovation method that many others were interested in learning from. It has not at all been highlighted as a flagship. Four years have passed since the property was bought, and there is still no completed consultation between the housing company and the tenants concerning how the renovation should be done. The interviewed tenants described a process of occasional meetings—extremely sparse—where the housing company provided information on details, such as tile colour choices, but could not answer basic questions about what it would cost and when renovations would begin.

Initially, there was a very positive view of the approach of having a “zero option”, and all interviewees still consider it important. This because the board of the local Union is well aware that there is a group who cannot afford a rent increase: These people have no expenses they can cut down on.

The housing company formed its plan based on past experience that it is feasible to offer different renovation options: the above-mentioned mini-midi-maxi model. In this case, the “zero option” was the mini one, and two different standard raising alternatives were presented as midi and maxi. One was to get new porcelain and tiles as surface material in the bathroom, the other a fully renovated kitchen with all materials replaced.

However, the standard raising alternatives had no price tag. This hindered the local Union’s dialogue with tenants, as they could not answer tenants’ questions, and tenants could therefore not express what they wanted or even comment on the housing company’s plan for renovation. Thus, despite the fact that the local Union held courses on democracy in connection with the renovation process and reached a large proportion of the 125 tenants through staircase dialogues and door knocking with translators, these efforts did not provide the knowledge and opinion to influence the process and drive it forward.

It was not until 1.5 years after the first information meeting was held that the housing company in April 2019 presented for the local Union the price tags for the two standard raising alternatives: €72 for the bathroom and €62 for the kitchen, thus around a 13% raise in rent for each or 25% raise for both. Tenants could also choose an extra standard raise, such as a bathtub and towel dryer.

At this point in time, the housing company suddenly argued that new electrical wiring should be drawn in the apartments and that the power plant should be switched to one with a ground fault circuit breaker. However, because this was considered a standard increase, it would lead to a rent increase of €5 per month. The Union opposed this increase, maintaining that electrical safety should be included as a basic standard, though this had not yet been heard.

The financial concerns surrounding the “zero option” have hardly been discussed at all, neither before nor after the price for these levels was announced. According to the interviewees, there has been very little transparency regarding the matter on the part of the housing company. In the interviews, the members of the local Union reported they had also not received much information from the negotiators in their own organization, who they assumed were similarly ill informed. Most light on the issue was actually shed by a pod produced by civil society, in which the chairperson of the housing company described how to think about the financial concerns surrounding the “zero option”. He described it as a “Robin Hood approach” where those with more resources pay for those who do not have as much:

And this isn’t so strange, in other situations you do this all the time. If we go for lunch and you take ‘today’s special’ and I order à la carte then I sponsor your lunch and the restaurant owner hopes that enough people will choose à la carte that he can afford to give you a low price. Or when I buy chips at the store, I sponsor the family of children who need to buy cheap milk. The trick, then, is to be able to guess in advance how many bags of chips you sell compared to how many litres of milk. So that you don’t stand there having sold all the milk too cheap and then no one comes and buys any chips (Pennypodden, Citation2018).

Several of the tenants in the local Union had heard about the “Robin Hood approach”, but it was not discussed, neither in meetings with the housing company nor by the public. The local Union focused their work on informing tenants of what they themselves had been told and gathering as many tenants’ views on the renovation plans as possible—even those who did not speak Swedish.

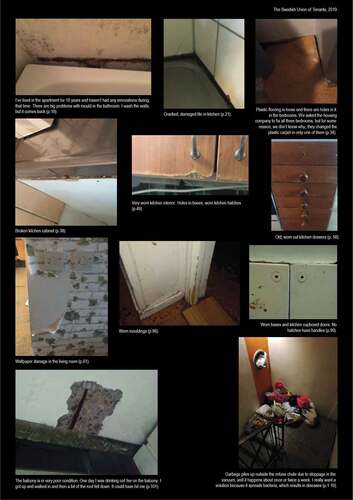

As it has emerged, it is obvious that the tenants, despite the fact that they welcomed a “zero option”, were dissatisfied with how it was designed. And it was not the “Robin Hood approach” they were critical of, but that the “zero option” only focused on the bathrooms, ignoring maintenance of the rest of the apartments and the building. In their own investigation conducted to assess the need for maintenance, 243 photos show that the situation in many apartments is precarious. In this selection of photos, we can see some of the situations tenants live in (Figure ).

Figure 2. The Union of Tenants assessed the need for maintenance and the 243 photos in their report show that the situation in many apartments is precarious. In this selection of photos, we can see some of the situations tenants live in (Union of Tenants, Bredfjällsgatan & Gropens Gård, Citation2019)

Interviewed members of the local Union were united in considering it unreasonable to raise the rent on a property they have lived for many years, with neglected maintenance:

I’m a bit sceptical about this ‘zero option’. Because it only applies to the bathroom. The thing is that there are many kitchens too, which need to be renovated. Why should people have to pay for a new kitchen when they are …. some kitchens here can’t even be used! I’ve been to a woman’s place, she told me: ‘I hate cooking in my kitchen. I don’t like being in the kitchen’. She showed me, it was chaos. Why should she have to pay to get a new kitchen, or a kitchen that works? (Interview with tenant).

This picture is actually shared by the chairman of the housing company himself, as he expressed in the public interview:

Since you don’t get a cut in rent every year as it wears out, you also shouldn’t have a rent increase when it comes up to the same level [meaning, the level it should have had, an acceptable level one could live in] (Pennypodden, Citation2018).

The political management of the public property is thus in agreement with the tenants; when a property reaches a “normal” standard, this should not lead to a rent increase. Why, then, aren’t all of the apartments renovated up to normal standard within the framework of the “zero option”? That is the interviewed tenants’ reaction:

The zero option is a first step in the right direction. But I think they should be able to make a ‘zero option’ for the whole apartment. It should’ve been done as maintenance actually, but since private companies haven’t done it, they’ve sucked out money, done as little as possible, and then they took off. Now we stand here today and there are a lot of rundown apartments, somebody has to pay for it. We’re the ones living in this poverty, and for a long time, we suffer, we’ve already received our punishment, we shouldn’t be punished again with higher rent. But the housing company says that otherwise other tenants must pay, that isn’t fair, they claim. And they say, they’re already in the red here. But that’s society’s problem! Society has to solve it! (Interview with tenant).

Complex social problems such as these are thus left to be solved by individual tenants in apartment buildings, in stigmatized areas where many residents are already struggling with major problems in the form of higher rates of unemployment, illness and youth crime. It is devastating:

People want to move. You can’t cope. It’s only the housing shortage that makes you stay. I can’t cope with broken laundry rooms. That I have to report the broken lift every week. Dirt in the stairwell. Stopped up garbage chute. Almost every month. It can go on for a week. Garbage in piles. It smells bad. ‘Mom I don’t want to go home’. I pay rent. What’s the difference between me and someone who lives in Majorna. Why don’t things like that happen there. They have the same housing company. And here in the square there were no such problems either! I want to move from here. I can’t take it! There’s enough stress in life already (Interview with tenant).

Despite the injustice, there is a willingness among the interviewees to contribute to seeking solutions at their own level. This is because this neighbourhood is actually not just “exposed”. There is also a very strong civil society, used to acting and reacting to social change. It is therefore not surprising that they have their own ideas about how a “zero option” can be accomplished, even if the national or local government does not take responsibility for funding maintenance and renovation:

I want more self-management. We can teach people who live here and let them go through the apartments and fix them. Think a little outside the box. This is a new problem. A municipal company takes over really worn-down apartments. The company says it’s necessary to replace the pipes because the leaks will be expensive. But you have to think differently. The housing company doesn’t. It’s not enough to think about things like before (Interview with tenant).

The tenants actually have come up with and suggested solutions for the consultation process, concrete proposals for how they think the “zero option” can be implemented:

In the consultation process, we have been asking for simpler, cheaper kitchen renovations where cabinet doors, bases and countertops are sanded and painted or replaced where restoration is not possible. This would be more cost-effective, as it’s cheaper to refurbish selected parts of existing furnishings than to tear everything out, and more environmentally friendly because masses of furnishings aren’t thrown away and existing furnishings are often of higher quality and last longer than the new materials that replace them. It would also be more socially sustainable, since we would preserve stocks with lower rent levels, which so many in our area and in our city depend on (Union of Tenants, Bredfjällsgatan & Gropens Gård, Citation2019, p. 4).

But their proposal has not been heard. The reason, they think, is linked to the social climate, with political forces that believe individual properties should cover their own costs. From this perspective, individual renovation projects must generate profits even in exposed areas, despite the fact that properties have been bought and sold in the interest of profit and the money no longer exists locally. Thus, when the national government claims that they invest in vulnerable areas, tenants do not see this happening in practice. The local Union is still struggling to find a solution, but they don’t really believe they will be heard:

Make us believe you can help us. Because it feels like we’ve lost hope somehow. It feels like we don’t believe in them. We don’t believe it can get any better. Because we’ve had it so bad for so long. So you get … you try to do something, but it doesn’t feel like we make it happen, we just talk and talk and talk, but nobody’s listening to us (Interview with tenant).

The fact that the rent also increases every year, most recently after stranded negotiations and decisions by the Housing Market Committee, raises justified questions from the tenants. What are we paying for? If not our apartments, then whose? Next year, property owners want even higher rent increases, which raises even more questions. Do they know the people who live here? Do they know what financial conditions many of us live under? The companies’ calculations may not go together, but neither do ours (Union of Tenants, Bredfjällsgatan & Gropens Gård, Citation2019, p. 3).

Hence, apart from the consultation process being extremely prolonged and not being democratic enough, the interviewed tenants believed the design of the “zero option” was poor; it did not meet the basic needs of the tenants, which they consider even more problematic in light of the fact that annual rent increases tend to raise rents more than inflation does.Footnote7 In other words, they stress that residents who live in rental housing pay more and more in rent to live, and they question why the development looks like this. The fact that a standard increase is being pushed or forced into renovation at an increased cost is more than many of them can handle. The tenants are therefore prepared to seek innovative solutions to the problem.

1.5. Theoretical considerations about the results

The interesting question is whether innovation will solve these problems. Isn’t it the case that these problems exist even when venture capital companies have not been involved in buying and selling real estate? Both private and public housing companies in Sweden, which have owned real estate for decades, operate renovation processes that lead to significant increases in rent and drive people from their homes. Isn’t it generally true in Sweden, as the research indicates, that displacement through renovation is an established profit strategy for housing companies (Baeten et al., Citation2017, p. 1)? Is there not reason to agree with research showing that powerful actors, instead of developing democracy through consultation, are transforming citizen dialogues into power instruments that enable them to recreate a “world order” that benefits themselves (Swyngedouw, Citation2005)? Do housing companies really have the will to design renovation plans together with tenants, plans that take into account all concerned tenants’ needs and wallets? Thus far, there is no affirmative answer to the latter question.

According to experiences from Learning Lab Hammarkullen, carrying out affordable renovation initiatives seems rather like a mission impossible. Renovation and neglected maintenance must be paid for in some way, and neither the housing companies nor the government believe it is their responsibility. As the burden has now been placed on the tenants, in the form of unjustified rent increases, they may just as well assume responsibility for developing new innovative knowledge that can, in the long run, provide a solution to this mission impossible. This is how the interviewed tenants’ responses can be interpreted.

So, can they play a role? Actually, research on innovation has shown that social innovation can enhance society’s capacity to act (Howaldt et al., Citation2018). It has been suggested that “the third sector, specifically through stimulating civic involvement, is best placed to produce social innovation, outperforming business firms and state agencies in this regard” (Anheier et al., Citation2019, p. 2). From this perspective, supporting civil society means that “society becomes a ‘living laboratory’ where citizens actively participate in the development of innovative solutions to Europe’s social challenges” (Lindberg, Citation2018, p. 4). The reason why this is considered to have positive effects and has the potential to lead to fairer societies is because it connects social innovation to empowerment dynamics (Moulaert et al., Citation2013). Innovation researchers Anheier and co-authors explain:

One of the main insights emerging from the research was the central role of (cross-sector) networks and collaborations in the governance of social innovation, from its emergence to its diffusion. Third sector organisations seem to take two distinct roles within these networks. First, they are particularly active in paving the way for social innovation, being the ones who not only care about social needs but actively try to tackle them in new ways./ … /Second, even more so than ‘collective’ action, third sector organisations performed ‘connective’ actions, bringing formerly detached or isolated actors together and establishing a link to target groups (Anheier et al., Citation2019, p. 281).

Subsequently, they recommend using actor-network theory in analyses, that is “studying specific, potentially formalised, actor coalitions pushing social innovation in future research,/ … /especially when the focus on micro level interactions and the question of ‘what is assembled’ in such social system” (Ibid, 282).

Actor-network theory (Latour, Citation2005) focuses on relations rather than separate actors, thus on how networks are built or assembled. In this theory, there are no inherent differences between actors in relation to size and power, instead, power develops in relation to building relationships. Relationships are built through “translations”, which can briefly be described as occurring when one actor is “allowed” to speak for another. Latour and colleagues thus claimed that there is a constant process of change in which where micro- and macro-actors interact.

One important agent in this institutional change may be the opening of “black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981). A black box refers to modes of thoughts, habits, forces and objects that are present in the relationships between institutions, organizations, social classes and states (macro-actors) and the individuals and groups (micro-actors) that interact with them. The difference between macro-actors and micro-actors lies in the capacity each one has to build power relations. A macro-actor operating under the premises contained in a black box does not need to renegotiate its content with the micro-actors, rather it takes for granted the assumptions hidden in it. In this connection, Callon and Latour conclude that “macro-actors are micro-actors seated on top of many (leaky) black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981, p. 286).

Research in Learning Lab Hammarkullen has shown examples of such black boxes. A previous article about dilemmas (Stenberg, Citation2018) described certain black boxes that actors wished to keep closed/undiscussed. One example was the Catch 22 situation combining: (1) “the utility value principle”; (2) “standard enhancement measures” and (3) the procedure of rent negotiation in renovation. The tenants in Hammarkullen tried to challenge this black box, but they were not able to even lift the lid. This was partly because they had not received enough information on financial and technical issues from the housing company, and the little information they had been given was shared through a poorly functioning process, from a democratic point of view, and in small scattered portions. But it was also because their own organization did not support them enough, and because they had no continuity and intensity. The Union of Tenants central office placed far too much of the responsibility for the process on the local organization, with tenants who worked on a voluntary basis. They would have needed more support to challenge the macro-actors and manage to open and debate certain black boxes. The interviews with tenants showed that they were very aware of the problem, but their questioning bore very little fruit. They experienced it as a failure, but at the same time could not take the blame for it—they simply did not feel they could influence the process very much. They felt that the consultation was mainly rhetorical on the part of the housing company, a box to tick off the list, so-called “tokenism” using Arnsteins’ language (Arnstein, Citation1969), not leading to a real shift in power that could benefit tenants.

Returning to academic theories, the great interest in relations between actors has resulted in actor-network theory being developed into theories of action net (Czarniawska, Citation2004). “Studying action nets means answering a dual question: what is being done, and how does this connect to other things that are being done in the same context?” (Ibid, 788). In this connection, the concept of translation recurs:

This notion of translation not only applies to linguistic translations—from the language of planners into the language of the users and the language of financiers; it applies also to objects, images and actions. This means that words can be translated into objects or into actions. But translation can also work the other way round; actions and objects can be translated into words./ … /In other words, translation can be regarded as the mechanism whereby connecting is achieved (Lindberg & Czarniawska, Citation2006, p. 295).

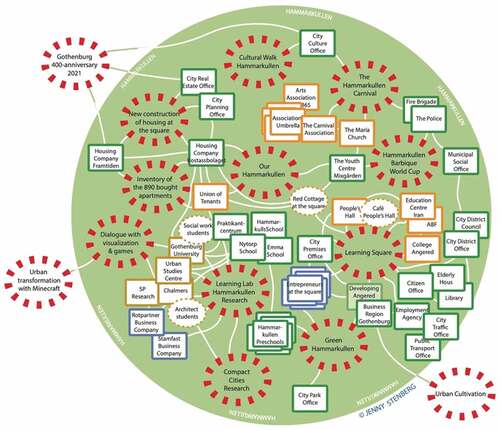

One of the most important experiences in Learning Lab Hammarkullen has been that in renovation projects intended to increase tenants’ power, it is important to look at the whole of a district and a city, thus expanding the framework of commitment far beyond what is directly related to the renovation project itself. Looking at Hammarkullen at a point in time just before renovation of the 890 apartments was supposed to take off, a Czarniawskan action net map—or map of “connective” actions using Anheier et al.’ terms—shows that there were a large number of actors driving urban transformation activities (Figure ).

Figure 3. Actors and actions in Hammarkullen. The large dotted circles are activities, the squares are different types of actors and the lines in between are connections that existed

One housing company that wanted to enter into a dialogue with tenants about renovation, thus, had a large number of actors and actions to relate to when the consultation took off. Unfortunately, in this case they did so to a very small extent. The company chose to make their own decisions about renovation, without conducting a dialogue with local actors. The company mainly approached civil society to inform about their plans, and they therefore did not understand this multifaceted overall picture. Not even local employees in their own organization had any power in the renovation process. If the company aimed to renovate in a way that tenants wanted and could afford, this was probably the biggest mistake they made in the process. Research has namely shown that civil society cannot manage to drive innovation alone. “The innovative potential of volunteering/ … /largely depends on establishing a system of productive collaboration between volunteers and staff” (Anheier et al., Citation2019, p. 282). Thus, there must be willingness on the part of a macro-actor like the housing company to implement a renovation approach based on “connective” actions, and to give a mandate to their own local employees to work with tenants in this spirit. Otherwise micro-actors will face severe difficulties when trying to challenge systems.

What would have happened if they had done so? To our knowledge, there is no research on middle-class and low-income rental property owners who have completed renovation processes in this spirit—including a “zero option” in rent increase—however, there are some interesting cases in Sweden to learn from.

1.6. Role models in Swedish practice

The private housing company Trianon in Malmö, through a combination of strategies with actions in collaboration with various actors, reported having been able to renovate a building in Lindängen, an area built as part of the Million Programme, without forcing any tenant to leave. Moreover, tenant relocation fell from 15 to 7% in a few years (Svensson, Citation2015). We do not know how the renovation consultation with the tenants went. The renovation did entail rent increases, however, the lowest being €60-100, which is about 10–15% on an average rent of €600-650 per month, meaning that the housing company implemented standard increases also in the lowest option when renovating. We do not know how the tenants managed this increase, however, the company claims that they maintain the apartments without rent increases, which obviously differs from the case of Hammarkullen.

What is most interesting about this case, however, is the overall perspective of the housing company (Interview with Trianon 2019–11-05). The neglected maintenance of the building, e.g. the need for new roofs and new laundry rooms, was financed by various means, one of which was reducing energy costs by 50% through a number of measures. Another was to combine the renovation with construction of a new building on a plot next door (in new production, rent setting is freer than in renovation), the first new construction in that exposed area in 37 years. The company received a substantial discount (90% the first years and then decreasing) on the land lease agreement from the City of Malmö for employing ten unemployed inhabitants from the area for two years. The renovation was thus procured with so-called social requirements, which were temporary employments with contractual salaries, not internships as is typical otherwise. At that time, they were building more houses and employed more inhabitants; in total they have created 35 real jobs for their tenants. Such efforts are likely to have important effects locally, with inhabitants increasing their trust in the housing company and society as a whole. According to a hired consultant’s calculations, renovation and construction have delivered a yearly social benefit of €710 million and the property value has doubled. That said, because this case has not been researched (the information comes from the company), we do not have the whole picture, but the broad concept of relating to actors outside the neighbourhood, creating innovative actions together, and linking environmental and social aspects is interesting.

Another interesting case to learn from is the apartment building Stacken in Bergsjön, Gothenburg, also built during the Million Programme era (Ohlson, Citation2018). This is not an ordinary apartment building, but a collective house inhabited by the middle and working class, with several common rooms, such as a large kitchen and a playground. It is also a cooperative tenancy association, which means that the tenants themselves own the house and make the decisions. The idea of the renovation was not to raise the standard, but still renovate in a way that would make it climate neutral to the extent possible. The exterior was therefore changed to save energy and the facades and roof were fully clad with 1800 square meters of solar panels. They cover 70% of the property’s electricity needs, including the tenants’ individual electricity, and they believe that with more adjustments they will reach 80–90%. The house today is classified as passive.

The fact that the tenants themselves are responsible for management of the house is believed to have been crucial both to the renovation being carried out in this manner and to it not resulting in any rent increase whatsoever. What the bank loan costs them is saved on reduced costs for electricity and heating (Ibid.).

The process of change in Stacken has been researched, but so far there are only academic articles on environmental and technical issues (Norwood & Andersson, Citation2018) or socio-democratic concerns (Hagbert et al., Citation2020), no overarching results linking all aspects. Thus, even with regard to this project, we do not have the complete picture yet, but given the environmental adjustments and the fact that there have been no rent increases, it is a very interesting example. Note, however, that because the tenants themselves had the decision-making power over how they would renovate, they did not, as it seems, need to develop “connective” actions to any significant degree in order to succeed.

2. Discussion and conclusions

Apparently, it is not impossible to renovate an apartment property so that it is sustainable environmentally, socially and even financially from the perspective of the tenants. The question is why more properties in Sweden are not being renovated in this way, when there are political decisions encouraging it (Boverket, Citation2014). Research in the Learning Lab Hammarkullen has shown that there is a great need for renovation to be done in a way that is affordable from all different perspectives, and tenants in the public housing company are interested in assuming responsibility for such innovation. However, because these tenants do not own the building themselves and do not have power in the decision-making process, they cannot do this alone. It must happen in collaboration:

As regards context conditions we have learnt that while third sector prevalence and civic engagement are important, these factors alone are far from sufficient for producing social innovation. Instead, and in line with previous social innovation research (Nicholls & Murdock, Citation2012), actor collaboration across sector borders was a significant enabler of social innovation (Anheier et al., Citation2019, p. 283).

Research has shown that protests from residents and activism can play a role in the development of democracy (Fung & Wright, Citation2003). Fung and Wright seem to agree with Howaldt et al. when they argue that it is possible to form institutions for collective decision-making that make use of the creativity people have to solve their own problems and create paths for social change:

Social innovation, in our sense, focuses on changing social practices to overcome societal challenges, meeting (local) social demands, and exploiting inherent opportunities (Howaldt et al., Citation2018, p. 224).

The present research, therefore, confirms Anheier et al.’s conviction that the innovative potential of volunteering largely depends on establishing a system of productive collaboration between volunteers and staff, and that theories of actor net (Latour, Citation2005), action net (Czarniawska, Citation2004) and “connective” actions (Anheier et al., Citation2019) seem to be appropriate tools for use in academic analysis of such activities.

What is possibly missing from these theories, however, is a developed analysis of what residents’ lack of trust in society means in the context. In her research on Hammarkullen, Hansson stresses “the importance of understanding the local conditions of trust and how they interact with planning processes in shaping outcomes and future possibilities of cooperation” and the “need to take the local conditions of trust into account early in the planning phase” (Hansson, Citation2018, p. 83). Thus, people’s previous experiences of society in Hammarkullen and similar areas make it extra challenging to build networks. Nonetheless, trust is absolutely necessary for that to happen:

Trust is of importance for people to engage in participatory activities in the first place (4), but even more importantly trust is what enables the necessary openness that will make participation successful (Hansson, Citation2018, p. 89).

The example initiative above, which gave 35 people work is something that probably increased stigmatized residents’ confidence in society. The residents involved in Learning Lab Hammarkullen raised exactly this question: How could the renovation process help them get paid work? Their answers to this question were: by listening to tenants’ ideas about how the renovation could be made more economically and environmentally friendly, by involving them in the practical work and by describing how such social aspects could be addressed through procurement. These expectation has unfortunately not been met.

If a democratic dialogue could be established, giving tenants more power, the interviewed tenants expressed their belief that the outcome would be more sustainable from many perspectives. What the tenants pointed out was that they, in contrast to the property owner, tended to prefer renovation, for example, fixing kitchen counters rather than throwing them away and buying new ones. The tenants felt their approach was more sustainable from an environmental as well as tenant-economic perspective. Additionally, tenants were more inclined to make demands on the social aspects of procurement.

For this to take place on a regular basis, a change is needed at the system level, partly in legislation and practice, but also a comprehensive change in the concerned actors’ views on how renovation could be carried out and who should have power over what. Developing such a change is a process, which itself needs “connective” actions to achieve success.

Acknowledgements

The present research has been carried out thanks to Formas – The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, which has funded the programme National Transdisciplinary Centre of Excellence for Integrated Sustainable Renovation (2013-3634-26822-63), of which Learning Lab Hammarkullen has been a part.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jenny Stenberg

Jenny Stenberg, Professor in Citizen Participation in Urban Transformation, in her research and teaching focuses on social aspects of sustainable development and specifically on citizen’s involvment in design, planning and renovation. She conducts most of her research in stigmatized and multicultural areas in Sweden, as well as in other parts of Europe and Latin American and African contexts.

Notes

1. Some of this background has previously been presented in Stenberg (Citation2018).

2. The film Push https://www.imdb.com/title/tt8976772/

3. Stigmatization involves disapproving of people from certain neighbourhoods, thereby distinguishing them from other people in society. It also involves a kind of more or less conscious “we vs. them” mentality on the part of the media as well as officials, politicians—and academics.

4. Renoviction—eviction by renovation—was coined by Heather Pawsey in 2008.

5. www.learninglabhammarkullen.se

6. framtiden.se/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Framtiden_Ars_Hallbarhetsredovisning-2018.pdf

7. www.hemhyra.se/nyheter/hyreshojningarna-hogre-an-inflationen | www.svt.se/nyheter/hogsta-hyreshojningen-pa-sex-ar | https://hurvibor.se/om-webbplatsen/(see boendekostnader/kostnadsutveckling and the picture showing the increase in the cost of rental apartments i Sweden, compared with the consumer price index)

References

- Anheier, H., Krlev, G., & Mildenberger, G. (2019). Social innovation – Comparative perspectives. Routledge.

- Arnstein, S. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(8), 216–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Baeten, G., & Listerborn, C. (2015). Renewing urban renewal in Landskrona, Sweden: Pursuing displacement through housing policies. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 97(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/geob.12079

- Baeten, G., Westin, S., Pull, E., & Molina, I. (2017). Pressure and violence: Housing renovation and displacement in Sweden. Environment & Planning A, 49(3), 631–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16676271

- Bergenstråhle, S., & Palmstierna, P. (2017). Every third may be forced to move: A report on the effects of rent increases in connection with ‘standard enhancement measures’ in Gothenburg (in Swedish). HGF, Bo-Analys-Vostra.

- Boverket. (2014). Movement patterns due to extensive renovations (in Swedish), Rapport 2014:34, Regeringsuppdrag.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Callon, M., & Latour, B. (1981). Unscrewing the Big Leviathan: How actors macro-structure reality and how sociologists help them to do so. In K. Knorr-Cetina & A. V. Cicourel (Eds.), Advances in social theory and methodology: Toward an integration of micro- and macro-sociologies (pp. 277–303). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Carew, A. L., & Wickson, F. (2010). The TD WHEEL: A heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures, 42(10), 1146–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.04.025

- Clark, E., & Hedin, K. (2009). Circumventing circumscribed neoliberalism: The 'system switch' in Swedish housing. In: Glynn, S. (ed.) Where the Other Half Lives: Lower Income Housing in a Neoliberal World. Pluto Press.

- Czarniawska, B. (2004). On time, space and action nets. Organization, 11(6), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508404047251

- Fung, A., & Wright, E. O. (2003). Deepening democracy, institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. Verso.

- Hagbert, P., Larsen, H. G., Thörn, H., & Wasshede, C. (2020). Contemporary co-housing in Europe: Towards sustainable cities? Routledge.

- Hansson, S. (2018). The role of trust in shaping urban planning in local communities: The case of Hammarkullen, Sweden. Bulletin of Geography. Socio–economic Series, 40(40), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.2478/bog-2018-0016

- Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Schröder, A., & Zirngiebl, M. (2018). Atlas of social innovation – New practices for a better future. TU Dortmund University.

- Industrial Facts. (2008). Renovation of multi-family house built 1961-1975: An interview-based study of needs and priorities in the 2008-2013 perspective (in Swedish). Industrifakta.

- Kunttu, S., Räikkönen, M., Uusitalo, T., Forss, T., Takala, J., & Tilabi, S. (2017). Combined economic and social impact assessment of affordable housing investments. RISUS – Journal on Innovation and Sustainability, 8(3), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.24212/2179-3565.2017v8i3p85-93

- Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. University Press.

- Lees, L. (2014). Staying put: An anti-gentrification handbook for council estates in London. London Tenants Federation, Just Space & SNAG.

- Lind, H. (2015). The effect of rent regulations and contract structure on renovation: A theoretical analysis of the Swedish system. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(4), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2015.1053981

- Lind, H., Annadotter, K., Björk, F., Högberg, L., & Klintberg, T. A. (2016). Sustainable renovation strategy in the Swedish Million Homes Programme: A case study. Sustainability, 8(4), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8040388

- Lindberg, I. (1999). The ideas of the welfare: The globalization, elitism and future of the welfare state (in Swedish). Atlas.

- Lindberg, K., & Czarniawska, B. (2006). Knotting the action net, or organizing between organizations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 22(4), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2006.09.001

- Lindberg, M. (2018). Inclusive research and innovation (in Swedish). Formas.

- Mangold, M., Österbring, M., Wallbaum, H., Thuvander, L., & Femenias, P. (2016). Socio-economic impact of renovation and energy retrofitting of the Gothenburg building stock. Energy and Buildings, 123, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.04.033

- Morgan, D. (1996). Focus Groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22(22), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129

- Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., & Hamdouch, A. (2013). The international handbook on social innovation. Edward Elgar.

- Nicholls, A., & Murdock, A. (2012). The nature of Social Innovation. In A. Nich- olls & A. Murdock (Eds.), Social innovation: Blurring boundaries to reconfigure markets (pp. 1–32). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York, NY: Pal- grave Macmillan

- Norwood, Z., & Andersson, A. (2018). PV Quality issues applying building integrated photovoltaics (Bipv) on the facade and roof when deep renovating a 50 year old apartment building (Conference proceeding, EU PVSEC 2018). https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/event/conference/35th-eu-pvsec-2018

- Ohlson, J. (2018). Here the tenants fix their own electricity (in Swedish). Hem och hyra. https://www.hemhyra.se/nyheter/har-fixar-hyresgasterna-egen-el/

- Pennypodden. (2018). Interview E125 – Johan Zandin (Cairperson Bostadsbolaget). Pennypodden. https://pennypodden.com/2018/05/28/e125-johan-zandin-ordforande-i-bostadsbolaget/

- Polanska, D. V., & Richard, Å. (2019). Narratives of a fractured trust in the Swedish model: Tenants’ emotions of renovation. Culture Unbound, 11(1), 141–164. https://cultureunbound.ep.liu.se/article/view/861.

- Posch, A., & Scholz, R. W. (2006). Applying transdisciplinary case studies as a means of organizing sustainability learning. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/ijshe.2006.24907caa.001

- Pull, E., & Åsa, R. (2019). Domicide: Displace ment and dispossessions in Uppsala, Sweden. Social & Cultural Geography, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1601245

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

- Stenberg, J. (2018). Dilemmas associated with tenant participation in renovation of housing in marginalized areas may lead to system change. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1528710

- Svensson, M. (2015, May). Residents are hired for the renovation (in Swedish). Sydsvenska Dagbladet, 25 May, 2015. https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2015-05-25/boende-anstalls-for-renovering

- Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-beyond-the-State. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279869

- Tenant Investigation. (2017). Strengthened position for tenants (in Swedis). SOU.

- Thörn, C., Krusell, M., & Widehammar, M. (2016). Right to stay: A handbook for organizing against rent increases and gentrification (in Swedish). Koloni. http://www.rattattbokvar.se

- Union of Tenants, Bredfjällsgatan & Gropens Gård. (2019). Maintenance is requested: Documentation of housing environment on Bredfjällsgatan and Gropensgård (in Swedish). HGF.

- Vaismoradi, M., & Bondas, H. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

- Westin, S. (2011). Rebuilding from the tenants’ perspective (in Swedish). HGF&IBF.