Abstract

Understanding gendered spaces in natural resource utilisation is critical in correcting gender inequalities in rural landscapes of developing states and thus ensuring sustainable development. This paper, therefore explores gendered spaces in mopane worm and woodland utilisation in Bulilima district of Zimbabwe by analysing niches of: exploitation, temporal dimension and niches that are resource-specific. This paper utilised a cross–sectional exploratory multi-method research design. However, the qualitative approach dominated within this design. This design found practical expression through the use of both qualitative and quantitative techniques within a participatory framework. Taking this approach ensured methodological triangulation which was key in enhancing the validity of study findings. The quantitative dimensions of the study were elicited through a survey questionnaire whereas the qualitative dimensions involved the use of Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs). Results reveal that spaces where men and women interact, use and exert control over mopane resources are influenced by institutions that make them complex and fluid. The paper concludes that policies should target efforts that reinforce those institutions and spaces in which women assume leadership in natural resource governance in order to make 2030 Agenda a reality.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

One of the aims of agenda 2030 is to achieve gender equality. Reducing gender inequality in natural resource management is critical for achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Understanding gendered spaces in natural resource utilisation is key intackling gender inequalities. The aim of the paper is to understand gendered spaces in mopane resource utilisation by analysing niches of: exploitation, temporal dimension and ecologies that are resource-specific. Using cross–sectional exploratory multi-method research design, findings reveal that niches of exploitation in the form of gendered spaces are affected by power issues which influence the utilisation of mopane resources within different spaces. These spaces are areas around homesteads, communal grazing areas, CAMPFIRE project areas and crop fields. Conclusions were drawn that the three tenure regimes are very complex and yet negotiable. The paper recommends that national and local governments should work towards strengthening inclusive institutions by transforming power relations and understanding social norms and behavioural changes. Participation of women in decision making should also be strengthened.

1. Introduction

Promoting gender equality has been recognized as a priority for development for a long time and it is a key prerequisite for the success of the 2030 Agenda (Branisa et al., Citation2013; Ward et al., Citation2010). The 2030 Agenda is a commitment to eradicate poverty and achieve sustainable development world-wide by 2030, ensuring that no one is left behind. It is a culmination of a democratic and participatory negotiated process by the 193 Member States of the United Nations, together with a large number of civil societies, academic and private-sector stakeholders (United Nations, Citation2018). It is not surprising therefore that many years after the landmark Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (UN Women, 2015) and at a time when the global community has adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Nations, Citation2016), the international consensus on the need to achieve gender equality seems stronger than ever before. While there is notable integration in all the 17 goals of the SDGs, goal 10 is the most relevant in illuminating the need to reduce gender inequality in natural resource access and use in rural communities of developing states. Goal 10 calls for the reduction in inequality within and among countries and the associated two targets relevant for this paper are 10.2 and 10.3. Target 10.2 notes that by 2030, member states should have empowered and promoted the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status. Target 10.3 implores member states to have ensured equal opportunity and reduced inequalities of outcome, including eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard (African Union, Citation2014). The 2030 Agenda shares similar tenets with Africa`s own Agenda 2063. Agenda 2063—a shared strategic framework for inclusive growth and sustainable development—was developed through a people-driven process and was adopted, in January of 2015, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia by the 24th African Union (AU) Assembly of Heads of State and Government, following 18 months of extensive consultations with all formations of African society (ibid).

As such this paper also draws from Agenda 2063 by integrating aspiration 6. This aspiration proposes an Africa where development is people driven, unleashing the potential of its women and youth. Item 48 of Aspiration 6 clearly states that the African woman will be fully empowered in all spheres, with equal social, political and economic rights, including the rights to own and inherit property, sign a contract, register and manage a business (ibid). The African Union further notes that rural women will have access to productive assets, including land, credit, inputs and financial service.

While reducing inequality and empowering women and girls is among the goals aspired by all, women continue to suffer discrimination, marginalization and exclusion. Nowhere is the discrimination, marginalization and exclusion clearly marked than in natural resource governance where despite women’s greater involvement in the collection and use of natural resources, they still suffer from insecure access and property rights which threatens the achievement of the SDGs. Women’s insecure access to natural resources and property rights have been fuelled by un-inclusive institutions in most developing States. It is for this reason that the 2030 Agenda outlines governance principles such as effectiveness, inclusiveness and accountability that institutions should strive to achieve, as well as principles that speak to SDG 16 which seek to end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children. Other 2030 Agenda governance principles relevant in this paper include “responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels” (target 16.7) and “policy coherence” (target 17.14) (Nations, Citation2016). Inclusive institutions therefore, bestow equal rights, entitlements and enable equal opportunities, voice and access to resources and services (ibid). By using the frameworks of the SDGs, Agenda 2030 and Agenda 2063 noted above, this paper demonstrates the critical need for analyzing the gendered spaces in natural resources as they (spaces) play a critical role in determining natural resource access at a community level.

The complexity associated with gender and resource tenure regimes has been succinctly captured by Rocheleau and Edmunds in their 1997 paper entitled Women, Men and Trees: Gender, Power and Property in Forest and Agrarian Landscapes. The paper argues that there are complex institutions, institutional structures and processes governing the gendered division and negotiation of resources. It has also been noted that relationships between genders affect hierarchies of access, use and control of resources, resulting in different needs, perceptions and priorities (Nussbaum, Citation2001). WWF Nepal (Citation2017) concurs that managing and using natural resources in a society is gendered implying men and women participate in and use natural resources differently. Women by their nature are “closer” to the environment because the success of carrying out their triple roles (reproductive, productive and community roles) is tied to the environment (Fonjong, Citation2008). A study on gendered participation in Nigeria conducted by Eneji et al., (Citation2015) found that exploitation of forest resources is done along gender disaggregated lines with both male and female exploiting forest resources. They (women) however, rarely have the same rights as men over natural resources (Gurung et al., Citation2000). With differences in rights, the two genders also bear different roles or responsibilities in resource management as stipulated by traditional gender division of labour and cultural norms which tend to define along gender lines those who benefit from natural resources (Fonjong, Citation2008).

In a study on gender roles and practices in natural resource management in the North West province of Cameroon, it was noted that traditional and cultural practices prohibit women’s activities around reserved areas, even in managing them (ibid). For example, Elias (Citation2016) found out that in certain rainforest societies, collection of tree products in primary forests is done by men, whilst gathering in secondary forests and around the homestead is conducted by women. Women’s access to trees and their products is commonly more limited than men’s and mediated by their relationship with their male counterparts. As such women’s rights are often negotiated and may subsequently not be best served by formal titling of land, which often vests ownership in a single head of household, who is often a man (Ikdahl et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, women’s relationship with the environment is regulated by culture, ethnicity, and taboos that sometimes deny them their rights and their critical role in resource management (Rocheleau & Edmunds, Citation1997). Most frequently it has been noted that women have only fluid use rights which are mediated by men. This lack of natural resource control poses a serious threat to their livelihoods, food security and might derail the achievement of many SDG goals, notable goals 5 and 10.

While some research has been done on the rights that women enjoy as they access, use and control natural resources in many developing countries (Fonjong, Citation2008; Gurung et al., Citation2000; Nussbaum, Citation2001), literature on gender differences in land and tree tenure exposes the multidimensional nature of tenure (Fortmann & Bruce, Citation1988; Rocheleau, Citation1988; Rocheleau & Edmunds, Citation1997) which requires further case studies for comprehensive understanding. Moreover, literature has not explored the link between gender differences in natural resource governance and the ultimate impact on sustainable development through the achievement of the SDGs. This study analyses women`s activities and authority in spaces as they access, use and control mopane worms and woodlands as a way of improving their resilience to poverty. Women`s spaces are said to be difficult to find because they are “in between spaces” that are not so useful to men but still useful to women (Fortmann & Bruce, Citation1988; Leach, Citation1992; Rocheleau, Citation1988; Rocheleau & Fortmann, Citation1988). The gendered spaces are diverse based on the characteristics of the `tenure niche`. For instance, in this study tenure niches identified included; niches of exploitation, niches with a temporal dimension and niches that are resource-specific. The assumption is that identification of gendered spaces and places through the ‘tenure niche’ concept can help illuminate the rights that women enjoy and thus ascertain whether such rights afford them decision-making powers to influence their own agency hence the trajectory of development in rural communities.

The following section of the paper explores the case background of the study before exploring frameworks that are critical in understanding gendered nature of natural resources. This is followed by the discussion of the methodology used and then discussion of results. The paper then extends the concept of gendered spaces explored from a household level followed through the different tenure niches and tenure categories for mopane worms and woodlands. The paper concludes with the argument that tenure categories are very complex yet negotiable. Women`s rights to access natural resources rely mostly on negotiated customary practices and social relationships. The final part of the paper dwells with recommendations that can be implemented to reduce inequalities on natural resource utilisation in rural communities.

2. Case background

Mopane worms and woodlands are found in three main systems of land tenure in Bulilima district. These are; Freehold land that is privately owned, State land and communal as well as Freehold land which is mainly privately owned in the form of large-scale commercial farms that were spared during the land reform process. The commercial farms are located in wards 9 and 10 which are the furthest wards from Plumtree town where the district begins. State land in the district is mainly the Natural Resources Management Project area, popularly known as the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) (Madzudzo & Hawkes, Citation1996). The CAMPFIRE area is home to a diverse population of wildlife which is a potentially viable non-consumptive tourism attraction and currently supports a viable safari hunting business. It was developed largely around the concept of managing wildlife and wildlife habitat in the communal lands of Zimbabwe for the benefit of the people living in these areas (Mutanga et al., Citation2015). As originally conceived, CAMPFIRE focused on four major natural resources: wildlife, woodlands, water and grazing. In practice however, the use of wildlife became paramount since its realizable value is currently so much greater than the others. The programme therefore aimed specifically to stimulate the long-term development, management and sustainable use of natural resources in the communal farming areas of Zimbabwe by promoting land uses appropriate to the natural constraints and opportunities of agriculturally marginal areas. This was to be achieved by giving resident communities custody over and responsibility for managing the resources and allowing them to benefit directly from their use (Murphree, Citation1997). The principal actors in CAMPFIRE are the producer communities, whose land-use decisions ultimately determine the fate of wildlife; the Rural District Councils (RDCs), representing the communities and authorized by government to receive and manage revenues from the use of wildlife under the CAMPFIRE scheme; and the safari or eco-tourism operators, who enter into various contractual arrangements with the communities through the RDC and then market the opportunities for hunting or eco-tourism to mostly foreign clients (Murphree, Citation1997). In Bulilima local people also graze their cattle in this area normally between August and October when grass around homesteads would have been finished (ibid)

The largest tenure is the communal system which is governed by the Communal Land Act of 1983. Rights of usufruct are allocated to an individual, usually by a chief for as long as the chief may need it or is cultivating on it. The rights of usufruct in an area the individual lives on includes the right to graze livestock, fetching firewood for fuel, thatching grass as well as harvesting fruits (including mopane worms as they are in abundance in the study area). There are no strict controls to rights of access to these as they are considered “free goods” (Mutema, Citation2003a). The rights of usufruct can be passed on as inheritance on the death of the original owner. The inheritor of the land is based on primogeniture but the wife or wives of the deceased can continue to cultivate the land. Inheritance for land is complicated where there is polygamy. Communal areas represent 41% of land in Zimbabwe. Communal grazing lands are therefore open for communal farmers to graze their livestock (ibid). This is where locals have their homesteads and fields where they do their crop faming.

It is important to note that theoretically, it is relatively easy and feasible to distinguish between the tenure regimes discussed above especially if they are well defined by the de jure rights. In practice however, it is often difficult to identify the boundaries of each property regime, in part because formal and customary tenure systems often differ and exist in parallel and in part because de jure customary or formal rights may differ from de facto access, whether this de facto access is recognised by a particular community or not. For instance, the CAMPFIRE area which is governed through de jure rights is accessed by community members of Bulilima through de facto rights, often resulting in conflicts between locals and the RDC which runs the CAMPFIRE project.

The tenure systems aforementioned constitute spaces where men and women interact, use and exert control over mopane resources. They are further explored in the paper to analyse gendered niches of: exploitation, temporal dimension and niches that are resource-specific.

2.1. Mopane resources

The Mopane worm, the edible larvae of the Saturnid moth Imbrasis beilina has become one of the most economically important forestry resource products of the Mopane woodland in southern Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and the northern Transvaal (Bradley & Dewees, Citation1993; Gardiner & Taylor, Citation2003). Recent research indicates that the Mopane worm contributes substantially to incomes and food security in households across the region (Sekonya et al., Citation2020). In Bulilima the worm is known in local languages as icimbi in Ndebele and mashonja in Kalanga. It grazes primarily on the leaves of Mopane woodland (Chavunduka, Citation1975). It has been estimated that the processed Mopane worms (dried and ready for consumption) contains three times more protein content of beef by unit weight and have the advantage that they can be stored for many months (Illgner & Nel, Citation2000; Headings & Rahnema, Citation2002 as cited in Akpalu, Citation2009). It is even listed as one of the most important African insects by entomologists (Toms et al., Citation2003). The worm is now the basis of a multi-million dollar trade in edible insects providing livelihoods for many harvesters, traders and their families in Southern Africa (Illgner & Nel, Citation2000; Toms et al., Citation2003). Additional, the Mopane worms have been identified as important resource to rural livelihoods as well as in addressing food security (Baiyegunhi et al., Citation2016). It is important to note that this trade in Mopane worms is not a recent phenomenon. It dates back to pre-colonial times (Marais, Citation1996). It should however, be remembered that Mopane worms and the woodlands though significant for the livelihoods of rural communities exist in the context of the wider rural household economy which usually comprises agricultural production, livestock production, remittances and government support etc.

On the other hand, mopane woodlands play a significant role in the livelihoods of the rural poor. They provide among other things fuel wood, poles used for construction of traditional structures, edibles such as mopane worms and medicine (Madzibane & Potgieter, Citation1999). Mopane products are used for a variety of uses such as firewood, while the mopane worms is used to supplement their diet (Makhado et al., Citation2014). However existing literature (Hobane, Citation1995; Moruakgomo, Citation1996; Letsie, Citation1996; Illgner & Nel, Citation2000; Akpalu & Parks, Citation2007) indicates that the increased commercialization of the Mopane worm trade and pressure on Mopane woodland in Southern Africa has led to over-harvesting and deforestation. Research conducted by Toms (2001) on the Mopane worm harvesting techniques in the Limpopo Province of South Africa indicated that there was no sustainable harvesting. Instead, traditional myths play a strong role in determining harvesting strategies used. Baiyegunhi et al. (Citation2016) concurs that there is continued over-exploitation and commercialisation of the mopane woodlands particularly in South Africa.

The value chain system of mopane worms shows that components such as production and trade reflect a defined division of labour based on indigenous production and labour practices (Neumann & Hirsch, Citation2000). Women and girls are mainly responsible for collecting mopane worms as other studies also confirmed (Kozanayi & Frost, Citation2002; Mufandaedza et al., Citation2015). They are also normally the main actors in the processing of the worms because of the advanced knowledge they possess compared to their male counterparts (Mufandaedza et al., Citation2015). Men tended to occupy the marketing space (trading of the worms in areas that are further away from home).

Bulilima district is naturally endowed with Mopane woodlands and Mopane worms which play a pivotal livelihood role as a source of income and food especially during drought seasons (Gondo et al., Citation2010; Mahati et al., Citation2008). Mopane worms play a critical role as a source of livelihood as it generates income and food for many households. Bulilima Rural District Council (BRDC) facilitated the construction of amacimbi processing factory though to date, the construction is still not yet complete due to financial challenges (Mahati et al., Citation2008). Over the years the management of Mopane woodland and Mopane worms had been left to the communities. However, this has resulted in over-exploitation. Maviya and Gumbo (Citation2005) note that commercialization of Mopane worms in Bulilima has, through sales and marketing outside the area of origin, led to increased rates of extraction, improper harvesting methods and use of inferior materials. Some sectors of Bulilima community have however, attempted to prevent total destruction of the resource through privatisation (ibid). Some members of the community have also formed a community trust known as Amacimbi Trust to manage the Mopane tree that is fast being degraded and also to facilitate the marketing of the Mopane worm (Mahati et al., Citation2008). BRDC has also tried to promote the management of Mopane worms through the Community Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM) approach though there have not been any notable successes (Maviya & Gumbo, Citation2005).

A tenure niche can be thought of as “a discrete area of land within a landscape defined by the specialized set of tenure rules that are applied to it” (Bruce et al., Citation1993). The niche concept can also refer to niches of exploitation, and thus to non-spatial dimensions as well. Several scholars (Fortmann & Bruce, Citation1988; Leach, Citation1992 among others) have argued that women’s spaces are difficult to find because they are “in between spaces” that are not so useful to men but yet useful to women because they use them for their survival. Identification of such spaces and places can help illuminate the type of rights that women enjoy and whether such rights afford them decision-making powers with regards to mopane worms use.

3. Frameworks for analysing gendered spaces in natural resource utilisation

The paper integrates the Feminist Political Ecology (FPE) conceptual framework with the complexity and dynamism of gendered resource tenure regimes (Rocheleau & Edmunds, Citation1997; Rocheleau et al., Citation1996). The FPE examines the critical role of gender in shaping resource access and control and how this phenomenon interacts with social structures both formal and informal institutions to shape the negotiation process over access and control of natural resources. Quite often formal and informal institutions structure the distribution of opportunities, assets and resources in society (Nations, Citation2016). In their 1996 edited volume, Feminist Political Ecology, Rocheleau et al. (Citation1996) situates gender as a crucial variable in shaping environmental relations. This theoretical situation of gender sees gender norms as a result of social interpretations of biology and socially constructed gender roles, which are geographically varied and may change over time at individual and collective scales (Sundberg, Citation2015). Central to the FPE perspective is an emphasis on uneven access to, distribution and control of resources by gender, as well as class and ethnicity. FPE illuminates the nuanced and complex (re)negotiation of gender roles, responsibilities, spaces and human—environment interactions happening at the local level (Hovorka, Citation2006), with institutions playing a critical role in determining distribution and control of resources by gender. Institutions often trigger behaviors and trends that can have positive or negative impacts for developmental outcomes, and in particular for inclusiveness (Nations, Citation2016). On the other hand, power holders can shape institutions for the benefit of some rather than all groups of society (ibid) as is demonstrated in this paper. Institutions that are not inclusive potentially infringe upon rights and entitlements, can undermine equal opportunities, voice and access to resources and services and perpetuate economic disadvantage (World Bank, Citation2013). It is clear therefore that for 2030 Agenda and Agenda 2063 to be realised there should be concerted efforts in transforming institutions that are not gender sensitive in natural resource governance.

FPE advances three primary areas of research; (1) gendered environmental knowledge and practices; (2) gendered rights to natural resources and unequal vulnerability to environmental change; and (3) gendered environmental activism and organizations (Rocheleau et al., Citation1996). The three research areas are critical in identifying how inequality is (re)produced when women’s environmental engagements, knowledge, and activism are neglected (Sundberg, Citation2015). As such, by putting women at the centre of environmental research, FPE has revolutionized research in political ecology.

Women in many rural areas manage spaces along with specific natural resources that are nested in or between spaces controlled by men (Rocheleau & Edmunds, Citation1997). The FPE sheds light on the complexity of customary laws that grant men and women differing rights and responsibilities to multi-dimensional fields with distinct and overlapping species (Sundberg, Citation2015). It (FPE) highlights differences between men and women regarding: (i) rights to own land with formal title; (ii) spaces and places for using trees and forest resources and in exercising some control over management; and (iii) access to trees, forests and their products through several nested dimensions (gendered spaces). Based on institutions of adjudication (customary and statutory) and the prevailing social ecological norms, women and men have differing access to an array of landscape spaces and resources (Rocheleau & Edmunds, Citation1997; Rocheleau et al., Citation1995; Wooten, Citation2003).

The rights of entry into landscape spaces and use of resources within these spaces can be explained using the concept of “tenure niches” (Bruce et al., Citation1993). Quite often tenure niches overlap for instance when one set of users owns the right to harvest fruits from trees, another set of users owns the right to the timber in these trees, and the trees may be located on land owned by still other’s (Bruce et al., Citation1993). In this study, tenure niches help us understand the dynamics of mopane worm harvesting, largely by women, from spaces, which are traditionally coveted by men. Ostrom and Schlager (Citation1992) note that operational rules may allow authorized users to transfer access and withdrawal rights either temporarily through a rental agreement, or permanently when these rights are assigned or sold to others.

4. Study area and methodology

The study area, Bulilima district is located in Matabeleland South province of Zimbabwe. The district lies within Natural Regions IV and V which are characterised by short, variable rainfall seasons averaging generally below 400 mm per year and long dry winter periods (Magadza, Citation2006; Mahati et al., Citation2008; Matsa & Simphiwe, Citation2010; Vincent et al., Citation1960). It is characterised by multiple livelihood strategies that include agriculture, wildlife utilization, commerce, social services, light industries, public services and informal sector. The importance of these sectors can be seen in terms of wealth creation and income generation. Field crop cultivation is often not a sustainable form of land-use and an increase in population in the last decade has put more pressure on the land. Communities rarely have surplus agriculture produce for sale. Cattle rearing appear to be the main agricultural activity in the district although there is a critical shortage of grazing land (Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency, Citation2012). The district has a wide range of natural resources ranging from soil, vegetation and wildlife species (including kudus, elephants, lions, impalas, buffaloes, wildebeests and zebras), birds species and mopane worms. However, these resources are under threats of extinction due to over-exploitation for both trade and consumption (Mahati et al., Citation2008; Matsa & Simphiwe, Citation2010). This condition is induced by the inadequacy of income generating resource base of the community.

Bulilima was selected for this study because of the abundance of mopane worms and woodlands. Moreover, it is considered to be one of the poorest and most marginalized regions in Zimbabwe and faces challenges of starvation, poverty, HIV and AIDS and unemployment (Magadza, Citation2006; Mahati et al., Citation2008; Zimbabwe Election Support Network (ZESN), Citation2008). Crops do not normally do well hence natural resources such as mopane worms become very significant. It is also interesting to note that the district lies in Matabeleland South Province with a special historical and political context. In the last three decades Matabeleland South region, where Bulilima is located has experienced intense contestations of political power between the locals, various political parties, and even Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs). As such the region is a restless frontier where identities (ethnic, regional and national) and politics are in a constant shift (Alexander, Citation1991; Mabhena, Citation2010; Msindo, Citation2012; Phimister, Citation2008). It is therefore, critical to understand how these various dynamics aforementioned interact to influence the operational rights of entry and use of resources in Bulilima district.

This paper adopted a mixed method research design where the qualitative approach was the most dominant. Taking this approach ensured methodological triangulation, which was key in enhancing the validity of study findings. Multi stage sampling was used to select the study sites. First the district of Bulilima and the respective wards were purposively sampled while the three wards (Dombolefu, Bambadzi and Makhulela) were sampled based on their known abundance of mopane worms and woodlands compared to the other wards.Footnote1 Stratified random sampling was used to select one village per ward. Selection of households for the survey was systemic in the sense that questionnaires were administered alternately, meaning that the researcher skipped every second household. A quota sampling method in which 30 questionnaires were administered per village was used. The survey only solicited demographic data on household heads and data on the most popular tenure areas for mopane worms and woodlands. Qualitative dimensions used included interviews, FGDs and participant observations. Groups that participated in discussions were drawn from traditional leadership, members of village development committees and members of special interest groups such as grazing and natural resource management committees, as well as ordinary men and women. Each village had 3 FGDs separately for men, women, and a group of traditional leaders. Altogether, 114 voluntary participants were involved in the discussions, 38 from each village.

Key informant interviews were also conducted with informants who included 6 ordinary men and women, 2 from each village, traditional leaders (village heads), government and quasi-government leaders (District Administrator, Forestry Commission officer, ward councilors, representatives from the natural resources committee in the RDC and Bulilima District Chief Executive Officer). These key informants were selected because of their perceived diverse expertise in natural resource management in the area. As such, they provided valuable information on the spaces and places exploited by men and women as they strive to access, use and control mopane worms and woodlands in Bulilima.

Thematic analysis was largely used to analyse rich data gathered through interviews and FGDs. Themes were developed following certain patterns of meanings and guided by the objectives of the study. Themes developed centered around different types of niches as further explored in the findings section. Thematic analysis is a flexible method that allows the researcher to focus on the data in numerous different ways. This approach was preferred because of its flexibility as it allowed the researcher to focus on analysing meaning across the entire dataset and in depth. It also allowed for interrogation of the latent meanings in the data, the assumptions and ideas that lie behind what is explicitly stated as also noted by (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Quantitative data was analysed to generate baseline frequencies on numbers of males or females utilizing resources in each tenure niche.

5. Results and discussion

The results and discussions that follow reveal the complex and fluid nature of the gendered resource tenure niches in Bulilima. Gendered resource tenure niches are influenced by various institutions and power dynamics.

5.1. Tenure niches of exploitation

The most significant tenure niches identified that related to mopane worms and woodlands management in Bulilima were spatial niches of exploitation such as niches related to gendered resource tenure regimes and niches that were resource-specific such as mopane worms being seen as a feminine resource and mopane woodlands as a masculine resource.

(i) Niches that are resource specific

The study revealed that social norms and beliefs around “manhood” restricted local menFootnote2 from actively participating in the harvesting of mopane worms and firewood. Some of the men were heard arguing:

‘it is embarrassing for a man to be seen amongst women collecting mopane worms. In our society that is unmanly’ (FGD with local men at Mbimba village, Bambadzi ward 22 April 2014).

Their attitude towards mopane worm harvesting thus created some space that was exploited by local women as they harvested the worms and fetched firewood with minimal regulations.

However, local men`s lack of interest in the harvesting of the worms had an undesirable effect of creating spaces for outsidersFootnote3 to exploit the worms (see discussion on Communal grazing under the section on spatial niches of exploitation below). The outsiders competed with local women for mopane worms. This competition was usually unfair to local women who, besides harvesting mopane worms had other important tasks to do at home. Outsiders, who came into the villages specifically to harvest mopane worms, were able to camp in the forest day and night until the worms were finished. Local men`s lack of interest in mopane worms nevertheless, needs to be put into perspective. It seems to be influenced more by social stigma which disappears in times of crisis such as drought. Drought often brought different dispensations, with local men participating in the picking and trading of mopane worms. The need for survival necessitated pragmatism and a temporary abandonment of patriarchal considerations. The claim that mopane worm harvesting is a woman’s chore does not hold anymore. With men also partaking in the activity, it could be argued that this role is culturally constructed rather than embedded in any economic rationality.

(ii) Spatial niches of exploitation

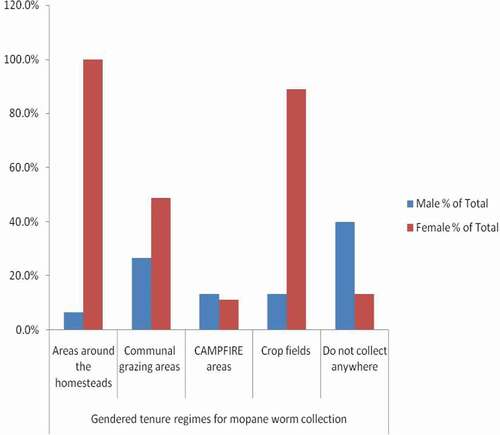

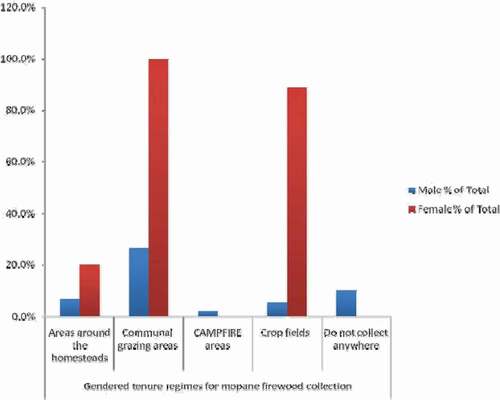

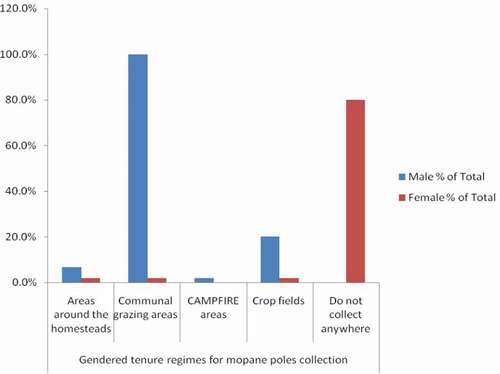

The spatial niches of exploitation were identified as gendered resource tenure regimes for mopane worms and woodlands (mainly firewood and poles) collection. These were identified as areas around homesteads, communal grazing areas, CAMPFIRE project areas and crop fields.

5.2. Areas around homesteads

Women dominated the space around homesteads where they collected mopane worms and firewood (see ). Local men rarely occupied this space for resource utilisation. In one of the group discussions conducted some local men had this to say;

Figure 1. Gendered tenure regimes where mopane worms are collected (Source: author) % of respondents; Total N = 90.

Figure 2. Gendered tenure regimes where mopane firewood is collected (Source: author) %of respondents; Total N = 90.

“In our society areas around homesteads are reserved for women and children” (FGD with local men at Mbimba village, Bambadzi ward. 22 April 2014). They were further quoted saying: It is embarrassing for a man to be seen loitering around homesteads, worse if he is seen amongst women collecting mopane worms close to homesteads. In our society that is unmanly. Areas around homesteads are reserved for women and children (FGD with local men at Mbimba village, Bambadzi ward. 22 April 2014).

It is clear from that areas closer to homesteads were domains for women where they collected mopane resources, both woodlands and worms. CAMPFIRE project area was not popular for women as less than 10% collected mopane worms from there while even less (less 5%) collected firewood from there.

While men would not want to be seen loitering around homesteads, they still retained decision making powers on resources in this space. For instance, the study established that the practice of privatising land around homesteads as a management technique was a decision made by men. This was confirmed by another similar study conducted in another communal area of Zimbabwe (Katerere et al., Citation1999). A voice from Bambadzi ward confirmed this view stating that: “every homestead needs a man to protect its trees otherwise people will cut them” (FGD for men Mbimba village, Bambadzi, 20 December 2013). Yet another view expressed by women from Makhulela supported the above point: “people tend to respect a home with a man/husband that is why they would not dare cut trees around such homes or even pick firewood” (FGD with women, Makhulela 1 village, 2 January 2015). The voices from FGDs demonstrate entrenched culturally-constructed belief systems in society.

Privatisation of land around homesteads nevertheless, ensured that resources around homesteads were protected and only exploited by household members. As such women, who exploited resources in this area, remained protected from competing with outsiders as some of them noted: “trees around our homesteads are safe because we monitor them. At least we are assured of mopane worms almost every year because of these trees” (FGD with women from Makhulela 1 village, Makhulela ward, 27 July 2014). Privatisation of land thus demonstrates that in the absence of clearly defined rights over forest use and control and competition from non-local resource users ensures locals become active agents in monitoring their resources (Katerere et al., Citation1999).

5.3. Communal grazing areas

Communal grazing areas were found to be the major mopane resources collection tenure regimes utilised by both men and women though focusing on different resources (see ). Mopane worms and firewood collection were considered feminine activities while mopane pole collection was largely deemed masculine. As such mopane worms and firewood were women`s space in a men`s place.

Figure 3. Gendered tenure regimes where mopane poles are collected (Source: author) % of respondents; Total N = 90.

Customarily, local men held primary rights on natural resources found in the communal grazing area. These resources included grasses, trees, crop fields and forests. Bulilima is generally a cattle district with most of the cattle owned by men. Cattle are a symbol of wealth and power hence the importance of grazing areas to men. As such men were found to have absolute decision-making powers on the use of communal grazing areas. They had the power to exclude or include other users from accessing resources in the grazing areas. For instance, the study established that men were prepared to let women access mopane worms and firewood as long as they did not interfere with grazing.

While men were found to be largely successful in excluding non-locals from grazing their cattle in local communal grazing areas, they were reluctant in excluding the same group from exploiting resources such as fire wood and mopane worms. This was because effective monitoring of natural resources in grazing areas depended on the value that local men attached to those resources. In fact, community institutions (both traditional and modern) were found to be weak in monitoring access to mopane worms and firewood in the grazing area. Mopane worms for example, were harvested by people coming from all corners of the country. The researcher had an opportunity of observing these harvesters who deliberately set up camps in the forest. Monitoring of natural resources seemed to depend on the will of men in the communities. Grazing areas therefore, assumed multiple tenure arrangement systems that included open access and common property as noted by some local men: “anyone can harvest mopane worms Esidakeni, it’s a free area. There are no rules preventing anyone from doing that” (FGD ordinary men from Bambadzi ward, 23 May 2014). However, the same men were ready to prevent cattle from non-locals from grazing Esidakeni. It was therefore evident that local natural resource arrangements, if not re-examined had a tendency of perpetuating gender inequalities within local communities. Institutions such as the customary law, was operationalised to exclude outsiders from grazing their cattle in the community grazing areas but was relaxed when it came to the access of other resources such as mopane worms and firewood. Local women were left to compete for resources in an open access arrangement.

5.4. The crop fields

The crop fields were a major resource site for the collection of mopane worms and firewood mainly by women (see ). The area was not a major resource collection site for men because of its proximity to homesteads. Like all other tenure regimes identified, men still retained the primary rights over ownership and control of the area through a lineage system. Crop fields are usually passed down to descendants through the male line as the system is hugely patrilineal (Ensminger, Citation1997).

5.5. The CAMPFIRE project area

The CAMPFIRE programme area was also found to be a natural resources gendered place. Various actors contested for spaces to access and control resources in this tenure area. The CAMPFIRE programme was itself found to be run on a contested space, being controlled by the RDC through its conservation committee which had sub-CAMPFIRE committees in all wards. The study however, established that not only were inequalities in benefits from CAMPFIRE outputs but there were also diverse claims to the area by various actors which included BRDC, some cattle owners and the San people. The San are an indigenous minority group found in Tsholotsho and Bulilima districts of Zimbabwe (Hitchcock et al., Citation2016).

The multiple claims to the CAMPFIRE programme area tended to affect women`s access and use of resources in that area. For instance, women collected resources such as mopane worms and thatch grass from the area. While there were no restrictions to the quantities, they could be conflicts that usually ensued between the cattle owners and the RDC which sometimes compromised women’s access to these resources. These conflicts usually resulted in some cattle owners grazing their cattle all year round, thereby finishing all the grass. Thatch grass was said to be a valuable resource for Bulilima women. Women use it for domestic and commercial purposes. Grazing in the Lagisa area used to follow a known pattern. The pattern was that between November and April, cattle would normally graze locally and around homesteads especially when the rains are good. Between May and July, the cattle would then be turned into the fields after the harvest to eat crop residue. Cattle would only be taken to the Lagisa grazing area between August and October. By then, grass would have dried and nearly grazed off around homesteads. However, cattle owners now deliberately let their animals graze all year round as the feud between them and the RDC continues. As such, cattle graze all the grass including the thatch grass. With the lack of interest in mopane worms by the RDC and cattle owners, local women exploited this space though with competition from outsiders.

5.6. Gendered nature of resources and power

The study revealed that niches of exploitation in the form of gendered spaces were affected by power issues which influenced the use of mopane resources within those spaces. In the spatial niches of exploitation men`s control of decisions outside the domestic sphere were problematic in that there were other powerful forces which made real decisions. For instance, while men were said to be in charge of the grazing areas the study established that other actors such as the RDC made crucial decisions on resource use and access.

Moreover, the study established that communal grazing areas, customarily controlled by men, could easily be accessed by powerful outsiders, especially those with links to the ruling party Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF). The war veterans for example, frequently demonstrated that they were above the control by local community institutions as they grazed their cattle in any communal grazing area they preferred. In contrast women seemed to have real decision-making powers within and around their households. In fact, privatisation of areas around homesteads was done at the instigation of women. This demonstrated women`s hidden power and their ability to convince men to privatise land for their (women) own benefit.

It should be noted however, that men still retained authority and prestige as heads of families within their households though it was debatable whether prestige and authority still equated to actual power for decision making. Evidence from the study revealed that decisions on the use of resources in places closer to home lay largely with women while further from home men had to contest access and use of resources with other influential actors such as the RDC, Village Development Committees (VIDCOs) and WARD Development Committees (WADCOs).

6. Conclusion

Reducing gender inequality in natural resource management is indispensable for achieving sustainable development. To this end, there is a need for an analysis and understanding of the gendered nature of natural resource tenure regimes in rural communities where livelihoods of the poor are interwoven with their local natural resources. In this study, this was done through highlighting tenure niches where men and women used and exerted control over mopane worms and woodlands in Bulilima.

In all natural resource management landscapes, relationships among tenures generally depended on the fluidity of social and ecological conditions, forcing men and women to renegotiate their terms of access to specific resources. The tenure categories where mopane worms and woodlands were clustered represented spaces in which men and women used mopane worms and woodlands and in which they exercised control over these resources. What emerged from the analysis is that the three tenure regimes are very complex and yet negotiable. In all the tenure regimes, institutions were seen to be fundamental in determining whether women were excluded or included from mopane worm and woodland utilisation. Women largely accessed natural resources through usufruct rights derived from social relationships such as marriage. For instance, virtually all land was de-facto owned by men in the communities while women had to negotiate access to mopane worms and woodlands by taking advantage of their relationships with men. Nevertheless, women showed a preference to spaces closer to their homesteads partly because of multiple activities they are usually engaged in at home as noted by (Dianzinga & Yambo, Citation1992; Dkamela, Citation2001; Tiani, Citation2001; Timko et al., Citation2010; Van Dijk, Citation1999); Tobith & Cuny, Citation2006) .

What is coming out of the study is that the prevailing institutions and practices in the rural communities of Bulilima are not inclusive enough hence they tend to be fluid and thus favor men more than they do women. While men were found to be able to access mopane worms at will, it was not the case with women. It was therefore evident that local natural resource arrangements, if not re-examined, had a tendency of perpetuating gender inequalities within local communities. Institutions such as the customary law, patriarchy and power were operationalised to exclude outsiders from grazing their cattle in the communal grazing areas but relaxed when it came to the access of other resources such as mopane. With regards to power, Nnoko-Mewanu et al. (Citation2015) posits that there is a coherent and unified belief about the nature of power and who wields it within rural communities. These belief systems result in the general exclusion of women from decision-making processes while women may not believe that questioning their own exclusion is a viable option. As such there is generally an internalised disempowerment embedded in norms and beliefs which play on women’s sense of self-confidence making them pessimistic about their right to influence decision-making (ibid).

The UN (2016 p. 62) report however, is very clear on inclusive institutions and notes that these should bestow equal rights and entitlements and enable equal opportunities, voice and access to resources and services. Item 48 of Agenda 63 also argues for women empowerment in all spheres, including the rights to own and inherit property (UN, 2014). Moreover, section 10.3 of SDG 10 calls for the elimination of discriminatory laws, policies and practices. To this end, it is clear that efforts aimed at tackling gender imbalances related to natural resource utilisation in rural communities of developing states should focus and amplify those spaces where women can take leadership in natural resource governance and those institutions or practices that can empower them to make their own decisions. Such efforts should also incorporate women’s active participation in the use and management of local natural resources that they can use to create wealth and development within their localities.

Finally, the paper suggests two recommendations that can be implemented to alleviate issues of social injustice such as lack of access to natural resources. These recommendations can go a long way in reducing poverty and inequalities in rural communities of developing states.

National and local governments should work towards strengthening inclusive institutions. With regards to natural resource governance, this involves among other things transforming power relations and understanding social norms and behavioural changes. Quite often good institutions fail because responsible authorities do not give much attention to social norms within communities. While women in Zimbabwe have the right to own land and its associated resources, it is often the social norms that are much more powerful in most communities than formal laws and regulations. For instance, the study established that men are generally the de-facto owners of land and its resources meaning that they make most of the important decisions.

Local authorities should ensure that women participate actively in decision-making processes as this will increase their access to resources such land. It has been reported that one way of achieving higher women’s participation is through gender-based quotas. In the case of rural communities in developing states, women should be given quotas in local governance structures so that they can influence decisions on natural resource access and control.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mkhokheli Sithole

Mkhokheli Sithole is a versatile University Lecturer with several years’ experience whose interests blend development and livelihood issues. He is a holder of a PhD in Development Studies from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. He also holds an MPhil in Geography and Development Studies from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Norway. He is currently a lecturer at the Institute of Development Studies at NUST. Dr Sithole research revolves around natural resource use and access in sub Saharan Africa. His research places history at the centre of our understanding of contemporary power dynamics in natural resource management.

Notes

1. Information obtained from Bulilima Rural District Offices during initial visits in 2012.

2. Local men are men who reside in Bulilima and are thus also referred to as community members.

3. Outsiders are referred to as people who did not reside in the area under study. They only moved in to harvest mopane worms.

References

- African Union. (2014). Agenda 2063. The Africa we want. A shared strategic framework for inclusive growth and sustainable.

- Akpalu, W., Muchapondwa, E., & Zikhali, P. (2009). Can the restrictive harvest period policy conserve mopane worms in southern Africa? A bioeconomic modelling approach. In Environment and development economics (pp. 587–17). Cambridge University Press.

- Akpalu, W., & Parks, P. J. (2007). Natural resource use: Gold mining in tropical rainforest in ghana. Environment and Development Economics, 12(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X0600338X

- Alexander, J. (1991). The unsettled land: The politics of land redistribution in Matabeleland, 1980–1990. Journal of Southern African Studies, 17(4), 581–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079108708294

- Baiyegunhi, L. J. S., Oppong, B. B., & Senyolo, G. M. (2016). Mopane worm (Imbrasia belina) and rural household food security in Limpopo province, South Africa. Food Security, 8(1), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0536-8

- Bank, W. (2013). Inclusion matters: The foundation for shared prosperity. The World Bank.

- Bradley, P., & Dewees, P. (1993). Indigenous woodlands, agricultural production and household economy in the communal areas. In P. Bradley & K. McNamara (Eds.), Living with trees: Policies for forestry management in Zimbabwe (pp. 63–138). DC: World Bank.

- Branisa, B., Klasen, S., & Ziegler, M. (2013). Gender inequality in social institutions and gendered development outcomes. World Development, 45, 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.12.003

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bruce, J., Fortmann, L., & Nhira, C. (1993). Tenures in transition, tenures in conflict: Examples from the Zimbabwe social forest 1. Rural Sociology, 58(4), 626–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1993.tb00516.x

- Chavunduka, D. M. (1975). Insects as a source of protein to the African. Rhodesia Science News, 9, 217–220.

- Dianzinga, S., & Yambo, P. (1992). Les Femmes Et La Forêt Utilization Et Conservation Des Ressources Forestières Autres Que Le Bois. Cleaver Et Al, 233–238.

- Dkamela, G. P. (2001). Les Institutions Communautaires De Gestion Des Produits Forestiers Non-Ligneux Dans Les Villages Peripheriques De La Reserve De Biosphere Du Dja. In Tropenbos-Cameroon document (pp. 7).

- Elias, M. (Eds.). (2016). Gender and Forests: climate change, tenure, value chains and emerging issues. Routledge.

- Eneji, C. V. O., Ajake, O., Mubi, M., & Husain, M. (2015). Gender participation in forest resources exploitation and rural development of forest communities in Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Natura Sciences Research, 5(18), 61–71.

- Ensminger, J. (1997). Changing property rights: Reconciling formal and informal rights to land in Africa. In The frontiers of the new institutional economics (pp. 165–196). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Fonjong, L. (2008). Gender roles and practices in natural resource management in the North West Province Of Cameroon. Local environment. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 13(5), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701809809

- Fortmann, L., & Bruce, J. W. (1988). Whose trees? Proprietary dimensions of forestry. West view Press.

- Gardiner, A., & Taylor, F. (2003). Mopane woodlands and the mopane worm: Enhancing rural livelihoods and resource sustainability.

- Gondo, T., Frost, P., Kozanayi, W., Stack, J., & Mushongahande, M. (2010). Linking knowledge and practice: Assessing options for sustainable use of mopane worms (Imbrasia Belina) In Southern Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12(4), 281–305. ISSN:1520-5509

- Gurung, B., Thapa, M., & Gurung, C. (2000). Briefs/guidelines on gender and natural resource management. Unpublished report for ICIMOD, Nepal. Organisation Development Centre (ODC) Together Develop, Transform and Grow.

- Headings, M. E., & Rahnema, S. (2002). The nutritional value of mopane worms, Gonimbrasia belina(Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) for human consumption. Presentationat the Ten-Minute Papers: Section B. Physiology, Biochemistry, Toxicology and Molecular Biology Series. Ohio State University. 20 November 2002.

- Hitchcock, R. K., Begbie-Clench, B., & Murwira, A. (2016). The San in Zimbabwe: Livelihoods, land and human rights. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Hobane, P. A. (1995). Amacimbi: The gathering, processing, consumption and trade of edible caterpillars in Bulilimamangwe district. Centre for Applied Social Studies Occasional Paper 67, University of Zimbabwe.

- Hovorka, A. J. (2006). The No. 1 Ladies’ poultry farm: A feminist political ecology of urban agriculture in Botswana. Gender, Place and Culture, 13(3), 207–225. Human Ecology, 62, p. 166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690600700956

- Ikdahl, I., Hellum, A., Kaarhus, R., & Benjaminsen, T. A. (2005). Human rights, formalisation and women’s land rights in southern and eastern Africa. Institute of Women’s Law, Departmentof Public and International Law, University of Oslo.

- Illgner, P., & Nel, E. (2000). The Geography of Edible Insects in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A study of the Mopane Caterpillar. The Geographical Journal, 166(4), 336–351. issues and local experiences. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2000.tb00035.x

- Katerere, Y., Guveya, E., & Muir, K. (1999). Community forest management: Lessons from Zimbabwe. International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Kozanayi, W., & Frost, P. (2002). Marketing of Mopane Worm in Southern Zimbabwe. In Institute of Environmental Studies, University of Zimbabwe.

- Leach, M. (1992). 5 Women’s crops in women’s spaces. Bush Base: Forest Farm: Culture,Environment, And Development, 76.

- Letsie, L. (1996). A gendered Socio-Economic study of phane. In B. Gashe & S. Mpuchane (Eds.), Phane. Proceedings of the first multidisciplinary symposium on Phane (Vol. 18, pp. 104–121). Gaberone: The Department:KCS 1996.

- Mabhena, C. (2010). ‘Visible Hectares, Vanishing Livelihoods’: A Case of the Fast Track Land Reform and Resettlement Programme in Southern Matabeleland-Zimbabwe (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University Of Fort Hare).

- Madzibane, J., & Potgieter, M. J. (1999). Uses of Colophospermum Mopane (leguminosae Caesalpinioideae) by Vavhenda. South African Journal of Botany, 1(5-6), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0254-6299(15)31039-5

- Madzudzo, E., & Hawkes, R. (1996). Grazing and cattle as challenges in community based natural resources management in Bulilimamangwe District of Zimbabwe. Zambezia, 23(1), 1–18. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals

- Magadza, S. N. (2006). Empowerment, Mobilisation and initiation of a community driven project: Women and the Marula. Agricultural Economics Review, 7(1), 1–15. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.44107

- Mahati, S. T., Munyati, S., & Gwini, S. (2008). Situational analysis of orphaned and vulnerable children in eight Zimbabwean districts. HSRC Press.

- Makhado, R., Potgieter, M., Timberlake, J., & Gumbo., D. (2014). A review of the significance of mopane products to rural people’s livelihoods in southern Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa, 69(2), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0035919X.2014.922512

- Marais, E., (1996). Omaungu in Namibia: Imbrasia belina (Saturniidae: Lepidoptera) as a commercial resource. IN: Gashe. B. A. and Mpuchane, S. F., (Eds.). Phane. Proceedings of the first multidisciplinary Symposium on Phane 18 June 1996. Gaborone: Department of Biological Sciences: 23–31. Mennell, 1997.

- Matsa, M., & Simphiwe, M. (2010). Grappling climate change in Southern Zimbabwe: The experience of Bakalanga minority farmers. Sacha Journal of Environmental Studies, 4 (2014), 34–52. Number 1

- Maviya, J., & Gumbo, D. (2005). Incorporating traditional natural resource management techniques in conventional natural resources management strategies: A case of Mopane worms (Amacimbi) management and harvesting in the Buliliamamangwe district, Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 7(2), 7.

- Moruakgomo, M. B. W. (1996). Commercial Utilization of Botswana’s Veld Products the Economics of Phane. In The dimensions of phane trade. proc. first multidisciplinary symposium on phane, Botswana. Department Of Biological Sciences, University Of Botswana, and the Kalahari Conservation Society: Gaborone.

- Msindo, E. (2012). Ethnicity in Zimbabwe: Transformations in Kalanga and Ndebele societies (Vol. 55, pp. 1860–1990). University Rochester Press.

- Mufandaedza, E., Moyo, D. Z., & Makoni, P. (2015). Management of Non-Timber forest products harvesting: Rules and regulations governing (Imbrasia Belina) access in South-Eastern lowveld of Zimbabwe. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(12), 1521–1530. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2013.7720

- Murphree, M. W. (1997). Congruent objectives, competing interests and strategic compromise: Concepts and process in the evolution of Zimbabwe’s campfire programme. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University Of Manchester.

- Mutanga, C., Vengesayi, S., Gandiwa, E., & Never, M. (2015). Community perceptions of wildlife conservation and tourism: A case study of communities adjacent to four protected areas in Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science, 8(2), 564–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291500800218

- Mutema, M. (2003a). Land rights and their impacts on agricultural efficiency, investments and land markets in Zimbabwe. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 6, 1030–2016–82657.

- Nations, U., (2014). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development

- Nations, U., (2016). Global Sustainable Development Report 2016, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, July.

- Nations, U., (2018). The 2030 Agenda and the sustainable development goals: An opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3), Santiago.

- Neumann, R. P., & Hirsch, E. (2000). Commercialisation of Non-Timber forest products: Review and analysis of research. Center for International Forestry and Research.

- Nnoko-Mewanu, J., Mazur, R., Bird, S. R., & Mienzen-Dick, R. (2015). Gendered resource relations and Changing land values: Implications for women’s access, control, and decision making over natural resources. Paper Prepared for Presentation at the 2015 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, The World Bank-Washington Dc, March 23–27, 2015.

- Nussbaum, M. (2001). Women’s capabilities and social justice. In Molyneux. M., & Razavi. S. (EDs.), Gender justice, development, and rights. Oxford University Press.

- Ostrom, E., & Schlager, E. (1992). Property-Rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis. Land Economics, 68(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146375

- Phimister, I. (2008). The making and meanings of the Massacres in Matabeleland. Development Dialogue, 50, 197–214.

- Rocheleau, D., & Edmunds, D. (1997). Women, men and trees: Gender, power and property in forest and agrarian landscapes. World Development, 25(8), 1351–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00036-3

- Rocheleau, D., & Fortmann, L. (1988). Women’s spaces and women’s places in rural food production systems: The spatial distribution of women’s rights, responsibilities and activities. In 7th World Congress of Rural Sociology (Vol. 25).

- Rocheleau, D., Thomas-Slayter, B., & Edmunds, D. (1995). Gendered resource mapping. Cultural Survival Quarterly, 18(4), 62–68. http://hdl.handle.ne/10919/68994

- Rocheleau, D., Thomas-Slayter, B., & Wangari, E. (Eds.). (1996). Feminist political ecology: Global perspectives and local experiences. Routledge.

- Rocheleau, M. (1988). Gender. Resource Management and the Rural Landscape: Implications for Agro-forestry and Farming Systems Research.

- Sekonya, J. G., McClure, N. J., & Wynberg, R. P. (2020). New pressures, old foodways: Governance and access to Edible Mopane Caterpillars, Imbrasia (=Gonimbrasia) Belina, in the context of commercialization and environmental change in South Africa. International Journal of the Commons, 14(1), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.978

- Sundberg, J. (2015). Feminist Political Ecology. In D. Richardson (Ed.), The International encyclopaedia of geography. Wiley-Blackwell & Association of American Geographers.

- Tiani, A. M. (2001). The place of rural women in the management of forest resources. In Colfer.C.J.P & Byro, Y. (Eds.), People managing forests: The links between human well being and sustainability. DC: Resources for the future.

- Timko, J. A., Waeber, P. O., & Kozak, R. A. (2010). The Socio-Economic contribution of Non-Timber forest products to rural livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa: Knowledge gaps and new directions. International Forestry Review, 12(3), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.12.3.284

- Tobith, C., & Cuny, P. (2006). Genre Et Foresterie Communautaire Au Cameroun. Quelles Perspectives Pour Les Femmes? Bois Et Forêts Des Tropiques, (289), 3. https://doi.org/10.1982/bft2006.289.a20304

- Toms, R., Thagwana, M., & Lithole, K. (2003). Insects and Indigenous knowledge in exhibitions and education with special reference to Mashonzha, the So-Called Mopane Worm: Session IV: Indigenous knowledge and exhibitions. In South African Museums Association Bulletin: Proceedings of the 67th SAMA annual national conference (Vol.29, Pp. 8–10). Sabinet Online.

- Van Dijk, J. F. W. (1999). Non-Timber forest products in the Bipindi-Akom 2 region, cameroon: A Socio-Economic and ecological assessment. ISBN: 9051130384.

- Vincent, V., Thomas, R. G., & Staples, R. R. (1960). An agricultural survey of Southern Rhodesia. Part 1. Agro-Ecological survey. An Agricultural Survey of Southern Rhodesia. Part 1. Agro-Ecological Survey.

- Ward, J., Lee, B., Baptist, S., & Jackson, H. (2010). Evidence for action: Gender equality and economic growth, London: Vivid Economics/Chatham House. http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Energy,%20Environment%20and%20Development/0910gender.pdf.UN Women, 2015. Progress of the world’s women 2015–2016 summary. transforming economies, realizing rights. United nations entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women. www.unwomen.org women and the Marula. Agricultural Economics Review, 7(1), 1–15.

- Wooten, S. (2003). Women, men, and market gardens: Gender relations and income in rural Mali.

- WWF Nepal. (2017). Biodiversity, People and Climate Change: Final Technical Report of the Hariyo Ban Program, First Phase. WWF Nepal Hariyo Ban Program. Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Zimbabwe Election Support Network (ZESN) (2008). Report on the Zimbabwe 29 March Harmonized election and 27 June 2008 Presidential Run-Off.

- Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency. (2012) . Preliminary 2012 census report. Government of Zimbabwe.