Abstract

The study explores centralized contract farming sustainability among tobacco smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Despite studies on centralized contract farming to date, little has been theorized with regard to its sustainability. Using mixed-method research, questionnaires, key informant interviews, document review and focus group discussions were employed in gathering data from farmers, Extension Officers and field officers of the contracting firms. Using Pearson Correlation Coefficient and thematic analysis findings revealed that centralized contract tobacco farming is unsustainable. Institutional contract arrangements are manipulative and are unwelcome to farmers. Economically, contracting firms find it viable as they obtain more profit at the expense of smallholder farmers. Although farmers are assured of inputs, extension service and market for the product, the contract terms are characterized by transaction cost, uncertainty and information asymmetry. Moreso, although financial and physical assets ownership have been increased, human, natural and social capital are a challenge. Shocks, stresses and seasonality still characterize the vulnerability context of the farmers as society has been exposed to women and child abuses, food insecurity, and social decay. The study therefore recommends an increased participatory action and learning in crafting and implementing contract terms by farmers, state and non-state actors for sustainability to be realized.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Internationally, centralized contract farming is one of the five broad models of contract framing greatly prioritized in commercial practice. With the growth of smallholder tobacco production post 2000 Zimbabwe’s Fast Track Land Reform Programme, a commercial decision to facilitate stringent processing standard was brought to light. Yet the sustainability of the new relations between tobacco smallholders and agribusiness capital have rarely been discussed. The results of the study are useful scientific evidence to reveal the risks, uncertainties and information asymmetry characterizing centralized contract agriculture among Zimbabwean smallholder tobacco farmers. The results will assist farmers to know the participatory action and learning approach needed in crafting a sustainable centralized contract agriculture for policy and planning.

1. Introduction

“Contract farming has been employed in agricultural production for many years but its popularity seems to be cumulative in the recent years as 45% of small- and large-scale cash crop and livestock farmers in the world are growing on contract” (Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), 2001). Ramaswami, Bharat, Birthal and Joshi (Citation2006) allude that contract arrangements are organized in a variety of ways depending on the crop, the objectives and resources of the sponsor and the experience of the farmers. Thus, any crop or livestock product can be contracted out using either centralized, nucleus estate, the multipartite, the informal or the intermediary model. With the deterioration of input and extension services in many developing countries, FAO (2001) noted an upsurge in centralized contract usage among smallholder farmers. Macdonald and Korb (Citation2011) state that in 2008, centralized contracts accounted for 39% of the United States of America’s agricultural production. Centralized contract farming in poultry, pig, tobacco and sugar beans raised the country’s export revenue to 45% from 28% in 2007. In Vietnam, NedCoffee, Vietnam engaged in the origination, procurement and trading of coffee, cocoa and nuts. In 2010, the company contracted large and smallholder farmers under the centralized model. Outputs increased and the company emerged Vietnam’s third largest exporter with annual exports of 90 000 tons per year (Ramaswami et al., Citation2006). Bombay Sweets and Company, a major potato chip manufacturer in Bangladesh introduced centralized contract farming in potatoes to secure their raw material supply base. Farmers with large farms were given seeds of preferred varieties, Agrochemicals and technical advice. Ghosh, Sachita, Sundar and Asmeen (2009) revealed that this worked sufficiently well for the company to expand and helped farmers in increasing their income. Senthill Papain and Food Products (SPFP) established centralized contract scheme in papaya by targeting innovative and progressive farmers. In 2009/10 season, the company obtained 32 000 tons of papaya from large and smallholder farmers. In Mexico, centralised vegetable contract farming has operated for many years and improved smallholder farmer’s living standards and acted as a form of additional employment (Ruben et al., Citation2001). Cyhadai and Waibel (2012) also proclaimed that centralized palm contract farming in Indonesia in the late 90s has shown that while the contract arrangement has a significant positive effect on smallholder income overall, it discriminates against the poorer smallholders. More so, tobacco centralized contract farming arrangements in Chile and Guatemala have led to an improved population welfare through increased forex earning by 32% and 27%, respectively, among large-scale commercial farmers, (Swinnen & Maertens, Citation2006). In Zimbabwe, centralized contract farming is not a novel phenomenon. Crops like tobacco, cotton, maize, pepper, peas are always grown under contract and improved smallholder farmer’s income and food security. However, despite the studies aforementioned, little has been theorized on sustainability of centralized contract farming among tobacco smallholder farmers.

The reduction in the role of the state in providing marketing, input and technical advice have increased the initiative of donors, developmental Non-Governmental Organizations and private firms to strengthen agricultural production through contract framing. Rehber (Citation2007) states that the agricultural system (agri-food) has been subject to major structural changes driven by changes in consumer preferences, attitudes, technological improvements and food security. This has led to increase in contract farming, with the centralized contract model widely used. Despite the studies by Jackson and Cheater (1994), Simmons (2003), Miyata, Minot and Dinghuan (2007) on centralized contract farming, little have been theorized with regard to its sustainability. Therefore, it is against this background that the study seeks to assess sustainability of centralized contract farming among tobacco smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe.

2. The capabilities approach (CA)

The Capability Approach claims that the aim of development is to improve human lives. This can be realized by increasing the resource base of individuals. Thus, increasing the resource base reduce deprivation which can be attained by increasing literacy, income and employment opportunities (Zimbabwe Human Development Report, Citation2003). Basu and Calva (2011) capture the Capability Approach as a novel theoretical framework on wellbeing, development and justice. It purports that freedom to achieve wellbeing is a matter of what people are able to do and to be and thus the kind of life they are effectively able to lead. The CA provides an assessment of how well someone’s life if going or has gone in an account of wellbeing or human development. “The original Entitlement Approach was based on famine and food security analysis which examined people’s potential to acquire livelihoods legally, based on all possibilities and entitlements at their disposal” (Chitongo, Citation2017). The argument was that households are vulnerable because they fail to utilize their ability and resources at their disposal to avoid deprivation. Furthermore, it focuses on those means of commanding food that are legalized by the legal system operating in a society. However, the approach fails to appreciate that livelihood is not just about capabilities of people.

“Entitlement in CA refers to the various capabilities or privileges that can be acquired through interactions with actors and institutions. And the actors and institutions are the contracting firms and their field officers and the extension officer at the door steps of smallholder farmers. These are influenced by assets available to individuals,” (Sen, Citation1999, p. 23). The appreciation and understanding of entitlements is done in a holistic and systematic manner. Sen (Citation1981) based his model on smallholder farmer’s food security during famines. The same arguments are also valid for smallholder tobacco contracted farmers in the area under study. The entitlement approach helps to evaluate the worth of centralized contract smallholder tobacco farmers in relation to rural transformation and sustainability. The major components of the approach are endowment sets, entitlement mapping and sets that people have (Murugan, Citation2003).

In the context of centralized tobacco smallholder farming, resources include arable land, fuel wood, inputs (seeds, fertilizers), knowledge assimilated from extension workers and social safety networks. The adoption of these resources, taking into consideration indigenous knowledge systems, laws and regulating institutions, leads to environmental sustainability. Thus, it can be inferred that where there are limited resources, production will also be at minimal levels (Mutami, Citation2015). Thus, this study adopted the concept of endowment set to analyse the sustainability of the support by contracting firms on smallholder tobacco farming. Entitlement mapping narrates the rate and ways in which the endowment set (resources) is converted into goods and services and improve people’s livelihoods, (Alkire, Citation2007). Entitlement mapping is linked to three components, namely production, transfer and exchange.

The entitlement set attempts to combine the endowment set and entitlement mapping. It examines all the combinations of goods available to households, looking at how these goods can be used to increase resource acquisition and utilization. It should be emphasized that the concept of entitlement in this reading emphasizes the capabilities of rural people and how these capabilities can be converted to deliverables (Whiteside, Citation1998). It entails how assets with smallholder farmers are accessed or influence livelihood sustainability. It explores the relationships between transforming structures and processes and assets utilization for sustainable positive livelihood outcome.

2.1. Attributes of centralized contract farming

Centralized contract farming has agreements. Setboonsarng (Citation2008) orates that at the core of centralized contract farming (CCF) lies an agreement between farmers (producers) and buyers: both agree in advance on the terms and conditions for the production and marketing of farm products. These conditions usually specify the price to be paid to the farmer, the quantity and quality of the product demanded by the buyer, and the date for delivery to buyers. Agreements also include more detailed information on how the production would be carried out or if inputs such as seeds, fertilizers and technical advice would be provided by the buyer. For example, the centralized contract poultry farming in Andhra Pradesh state in India, the Hatcheries like Suguna, Pioneer and Diamond enters into an agreement with farmers to supply day old chicks, feeds and medicines on credit while farmers supply land and labour (Ramaswami et al., Citation2006). At the end of the cycle the sponsor buys the product at set quantities, quality and price.

According to Chitongo (Citation2017) contract farming follows a model. The model shows the hierarchy within the centralized contract farming arrangements. The sponsors are the contracting firms that offer inputs, technical extension service and a market to farmers. As in this case, the sponsors are the contracting firms, namely, Zimbabwe Leaf Tobacco Company (ZLT), Mashonaland Tobacco Company (MTC) and Premium Tobacco Farming (PTC). The owners of these firms do not directly interact with the farmers but through their administration and management, employ technical staff or field officers (M. Moyo, Citation2014). These field officers directly interact with farmers towards an agreed project. They relay information, distribute inputs, make transport arrangements and offer technical advice to farmers on and off the field.

The production and profitability of contract arrangements are dependent on a number of factors that include climatic factors, farmer’s response and initiatives, quality of management, quality of technology, financial incentives and government support. The field officers are thus responsible for quality management from land preparation to marketing.

2.2. Centralized contract farming and sustainable development

Agriculture is the single largest employer in the world, providing livelihoods for 40% of today’s global population (Chitongo, L | Sandra Ricart Casadevall (Reviewing editor), Citation2019). It is the largest source of income and jobs for poor rural households Giving people in every part of the world the support they need to lift themselves out of poverty in all its manifestations is the very essence of sustainable development. Eaton and Shepherd (Citation2001) state that centralized contract farming (CCF) has existed for a long time, particularly for perishable agricultural products delivered to the manufacturing industry such as milk for dairy industry or fruits and vegetables for making preserves. At the end of the 20th century, centralized contract farming has become more important in agricultural food industries in both developed and developing nations. It is seen as a tool for creating new market opportunities hence increasing incomes for smallholder farmers. Critics, however, argue that, it is likely to pass risks to small-scale farmers, thus favouring large-scale farmers at the expense of smallholder farmers. The centralized scheme is generally associated with tobacco, cotton, sugar cane and bananas and with tree crops such as coffee, tea, cocoa and rubber, but can also be used for poultry, pork and dairy production.

Globally, the contracting out of crops to farmers under centralized structures is common, (Minot & Ronchi, Citation2011). Centralized contract rice production for export was practiced in Cambodia in 2007. It has had a significant impact on improving farm efficiency, productivity and farmers income. Participant’s incomes increased by 25–75%. However, it was abandoned in 2010 as it posed serious threats to the natural environment. Minot and Ronchi (2015) state that forest land was reduced as large tracts of land were cleared for rice production. In Indonesia, Cyhadai and Waibel (2013) evaluated palm centralized contract farming and observed that while the farming arrangements have a significant positive effects on smallholder income overall, it discriminates against poorer smallholders. Estimates show that participation increased net household income by 60%.

More so, Simmons (2005) investigated CCF in poultry, maize and rice in the state of Andhra Pradesh in India and found out that production under contract is more efficient and profitable than non-contract production. The state is the leading poultry producing in India, at over 1.4million tons of meat in 2004. Contracting companies like Suguna, Pioneer and diamond delivered day old chicks, feeds and medicines to farmers (Ramaswami et al., Citation2006:32). Participants achieve incomes comparable to that of independent growers.

In a similar study of centralized contract green onion farming in the Shandong region of China, farmers who participated obtained benefits; it gave them more reliable income, generated additional employment, provided new technologies and improved market access. Contracting farmers earn significantly more than independent farmers after controlling for household labour availability, education and other expenses incurred. However, the farming posed threats to the Punjab River. It was heavily polluted and silted due to increased erosion from stream bank cultivation (Singh, Citation2002).

In the Rajasthan region of India in 2000, the World Bank’s District Poverty Initiatives Project (DPIP) launched a centralized contract dairy farming in the poorest districts in an attempt to generate a cash income on a regular basis for smallholder farmers. Since income from crop production was seasonal, milk production was launched to provide income continually on monthly basis and bonuses for extra deliveries. Farmers were given dairy cows, feeds and medicines. Livestock provided employment and livelihood security. Smallholder participants enjoyed more returns. In contrast, non-contracted dairy farmers suffered significant wastage and lower returns. In 2004, overgrazing was a threat to the physical environment. The Rajasthan Cooperative Dairy Federation funded and farmers adopted a pen fattening scheme that would reduce overgrazing and ultimately soil erosion (Ghosh et al., Citation2009). Roads were constructed and this attracted industries like banks, supermarkets and a lot of services. Segura (2006) posits that centralized contract farming in pepper and chayote in Costa Rica have more of these functions, a security device to enable farmers to take up new production activities and to gain access to specialized markets, provision of incentives to make investments needed for specialty production and provision of specialty markets. The provision of markets improved income and living standards among farmers.

According to the World Bank (Citation2019), the increased demand in agricultural products propelled centralized contract farming usage and one of the developments is the rise of in supermarkets in the food retailing. Over the last decades, the number of supermarkets has grown rapidly in the urban areas of developing countries, particularly in Asia and Latin America. A third development refers to the ambition of donors, developmental Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and governments in developing countries to strengthen smallholder access to markets. CCF is considered as one of the main instruments to link smallholder farmers to domestic and even foreign markets and thereby reduce poverty.

CCF is not a new phenomenon in Africa. Jackson (1994) posits that in Africa, contracting out of crops for farmers under centralized structures is common; they are often called grower schemes. Meeta (2008) states that centralized contract farming in Africa is often characterized with the growing of staple foods. In Zimbabwe, CCF is not a new phenomenon. Crops like cotton, maize, pepper, peas are always grown under contract. FAO (2012) concludes that the deterioration of input and extension support services in Zimbabwe have led to an increase in centralized contract farming among smallholder farmers. Agrifeeds in 2009 expanded its production base from commercial farming by contracting smallholder farmers under the centralized model.

Chamahwinya (Citation2016) found out that provision of high-quality inputs was a major incentive for production under centralized contract cowpeas and maize as reported by the majority of farmers. With centralized contract farming, there are reliable local and foreign markets, stable prices and reduced risks assurance and introduction of appropriate technology transfer. According to Shepherd (2013), centralized contract farming often introduces new technology and new skills to the farmer. Centralized contract farming arrangements permits farmers access to some form of credit to finance production inputs. In most cases, it is the sponsors who advance credit through their managers. So, there is transfer of skills and guaranteed and fixed pricing structures. However, there are risks, unsuitable technology and crop incompatibility, manipulation of quotas and quality specifications, corruption, domination by monopolies, indebtedness and overreliance on advances that is associated with centralized contract farming. So despite all the opportunities and constraint associated with centralized contract farming, its sustainability has not been explored.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. The study area

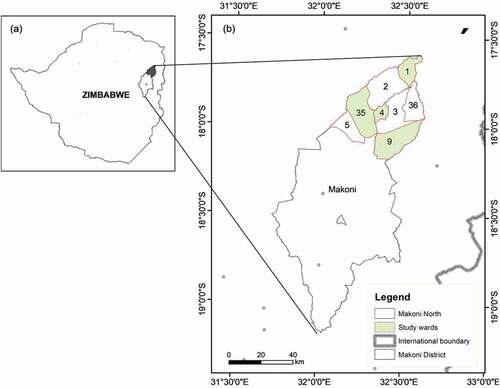

This study was conducted in Makoni district, Manicaland region where tobacco is the main cash crop with more than 75% of all farmers being regular tobacco growers. A total of 6 726 households are engaged in tobacco production and the total area under tobacco production is 3.200 ha (Dube & Mugwagwa, Citation2017, p. 80). The district is primarily a farming area, comprising of five constituencies namely, Headlands, Makoni South, Makoni West, Makoni Central and Makoni North. Makoni North was purposively selected for this study, due to its gently undulating terrain and rich soils. The study area covers four wards (Wards 1, 4, 9 and 35).

4. Source: Author creation 2021

4.1. Research design

A case study was used in this study as it has an in-depth understanding of the context of the research and processes taking place. Case study revealed, an in-depth understanding of the sustainability of centralized contract farming among tobacco smallholder farmers within their natural settings. It involves undertaking fieldwork interaction with participants in their natural settings which could be homes, work places, social places depending on the phenomenon. Muchengeta and Badza (Citation2010) view that a case study developed explanations and evaluation of the phenomenon.

4.2. Population

In this research, the target population included 1 018 tobacco growing farmers who were based in wards 1, 4, 9 and 35 of Marondera North constituency (TIMB, Citation2019). The target population included contracting firms’ field officers, centralized contract tobacco smallholder farmers and Agricultural Extension Officers.

5. 3.4.Sampling

The researcher selected a sample of 35 participants, comprising of 30 smallholder tobacco farmers, three contracting firms field officers and two Agricultural Extension Officer. The study adopted a two-staged selection or sampling approach, as recommended by Masvongo et al. (Citation2013). Purposive sampling was used to select contracting firms field officers and Agricultural Extension Officers who are specialized in tobacco farming. Purposive sampling targets richer sources of data with resembling characteristics of variables under investigation (Creswell, Citation2013). Secondly, the 30 farmers were randomly selected from beneficiary lists provided by the agriculture and extension officer. In a sample proportional to population see (Chitongo, Citation2017). Thus, five small holder tobacco farmers were selected in ward 5; 11 in ward 4; 7 in ward 9 and 7 in ward 35.

5.1. Research Instruments

A total of 30 questionnaires were researcher administered on farmers in the collection of data on centralized contract farming sustainability using social, economic, institutional and environmental dimensions. Key informants, contracting firms’ field officers and Agricultural Extension Officers. gave in-depth insights on centralized contract attributes and their sustainability in smallholder farming. In-depth interviews allowed probing for following up on key areas. This enabled the researcher to gather diverse information of farmers’ experiences in centralized contract farming. Audios were stored for cross-reference. To validate the survey a focus group discussion (FGD) comprising eight participants allowed farmers to open up, challenge one another and explain their responses without the researchers influence. This enabled the researcher to obtain richer data as farmers interacted freely in their natural setting. Document reviews were also used to obtain complementary information on sustainability dimensions.

6. Data analysis

A thematic approach was used to present qualitative data. Quantitatively the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine sustainability using expenditure and income relationship.

7. Ethical considerations

The research assured participants confidentiality by not using real names on interview records, thus codes were used. The research respected interviewee privacy by conducting interviews in conducive environments where no third parties accessed the information shared.

8. Results and discussions

Results of the study captured institutional, social, environmental and economic as dimensions of sustainability in centralized contract farming. FAO (2001) posits that a programme is considered sustainable when it promotes and maintains social solidarity environmental responsibility and economic efficiency and institutional user-friendly.

8.1. Institutional sustainability of CCTSF

Documents analysis revealed that centralized contract tobacco farming terms are exploitative and unfriendly to farmers. However, due to vulnerability context of smallholder farmers, they had no alternative option to carry out farming outside these contracts. They adopted this kind of contract to gain access to inputs, extension services and an assured market which cannot be realized by non-adopters of the contract farming model. More so, the interest rates set by contracting firms on inputs and extension services they offer are beyond famers’ capacity to manage as their products are given poor market prices. Centralized contract farming arrangements are manipulative. Arrangements are characterized by uncertainty and information asymmetry. Smallholder farmers cannot afford input prices charged by private entities hence they find themselves trapped in contracts. In an interview, one farmer has this to say:

Given other options, I would not like to grow crops on contract. The 30% interest in the 2018/19 growing season by MTC was not friendly to us as smallholder farmers. Arrangements are characterised by uncertainty and information asymmetry

This shows that farmers simply engage in the arrangemments due to limited options and lack of inputs to venture into other livelihood activities. In FGDs, smallholder farmers also reiterated that given other options, they will opt out of centralized contract farming. This is emblematic evidence that attributes of centralized contract are unattractive and detrimental to tobacco farming as a livelihood. Gie, San, Wyshe, Wetuschat, and D’Haese, (2017) found out that cassava smallholder farmers experienced unfair contract farming agreements in 2008 but because of poverty, they were unable to practice agriculture out of contract. Interest rates were high and poor service delivery by extension officers exposed farmers to poor quality products. The buying prices was therefore low to an extent that they do not enable them to meet basic needs like food, clothes, education and health services. However, due to government and smallholder farmers’ participation in contract terms formulations unlike in most developing nations, findings contradict with Segura (2006)’s centralized contract tobacco farming in Costa Rica where no exploitative tendencies are portrayed as household incomes increased and were able to meet basic needs. Agricultural Extension Officers have appraised centralized contract tobacco farming for giving farmers inputs, technical knowhow and assuring them a market without power for tobacco processing. The Officers argued that centralized contract tobacco farming arrangements lack sufficiency in providing key inputs like energy in tobacco processing thus risking natural forests depletion. Their operations are environmentally unfriendly as they have heightened forest clearance, loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, pollution and siltation. Extension officers also criticized contract arrangements for failing to provide farmers with food crop inputs. The officers castigated centralized contract tobacco farming for posing a threat to food security as farmers no longer engage in production of adequate food crops. An Agricultural Extension Officer has this to say:

We always visit these farmers to assess and assist in maize production. However, a lot of their time is spend in tobacco fields. More so, whenever they get maize inputs from the presidential input scheme, they redirect them to tobacco production.

This is attributed to lack of alternative production possibilities posed by centralized contract farming. Document review revealed that farmers lack the freedom to diversify into other income generating crops and schemes thus become vulnerable to food insecurity. The officers commented that centralized contract farming has a tendency of tying farmers to their main crop, discouraging the growing of other crops. Strohm and Hoeffer (Citation2006) states that, if contracting firms for some reasons chooses to end the contract, farmers may lose their source of income and their livelihood would be threatened as they do not have backup livelihoods activities to cushion them in times of uncertainties. Comparable results were reported by Strohm and Hoeffer (Citation2006) in centralized contract cassava farming in Nigeria. Farmers have less ability to maintain alternative production possibilities hence were in a more vulnerable position. The termination of some contracts exposed farmers to acute poverty due to loss of income and livelihoods. Hence, institutionally, contract arrangements have no resilience attributes.

Documents revealed that, though centralized contract farming terms impact negatively on the farmers, contracting firms are comfortable with the arrangements and operations. The firms affirmed that they are getting the rightful amounts of tobacco from farmers and they are operating at a profit. Though there are some cases of side marketing and failure to repay the loans, firms still make a profit. This is attributed to exploitative tendencies associated with contract arrangements. They buy with low prices from farmers and export at a higher price. One field officer stated that:

We are operating well above break-even. We have been operating at a profit ranging from 40% −60% since 2009. We usually buy tobacco at an average price of 3 USD/kg from farmers and export at an average of 7 USD/kg thus allowing us to make a profit and to expand. We are now operating in more than five provinces.

Ghosh et al. (Citation2009) found out that in Indonesia the farming arrangements by contracting firms worked sufficiently well in helping farmers in solving their food insecurity problems. The companies enjoyed a lot of profits that enabled them to expand and venture into new areas north of the country. This reveals misnomers characterizing contract arrangements in Zimbabwe.

The number of farmers who have spontaneously adopted the CCF is considerably lower, as many farmers seem to adopt CCF due to incentives offered by contracting firms. “For instance, 20 percent of CC farmers in the 2018/19 season were reported to be spontaneous adopters, with the remaining 80 percent under CCF as a condition for receiving subsidised input packages” (Kaczan et al., Citation2013). So in spite of bringing new technology and skills and income, farmers seem to adopt CCF due to the attractive packages given. Without incentives their level of resilience is very low there by compromising CCF sustainability. Some critics view technology—for example, as embodied in CCF—is insufficient to reduce food insecurity and sustainable wellbeing.

8.2. Social sustainability

Findings form key informants revealed that centralized contract tobacco farming is somehow benefiting the society. It is assisting the marginalized, vulnerable groups to have more control over their lives, socially and economically. It is helping the target group to contribute towards the community through knowledge sharing. Centralized contract farming has improved social cohesion through smallholder farmers working in groups and an improved integration with extension officials offering services. Informants further alude that centralized contract farming has promoted unity and a sense of belonging in the area through afforestation programmes introduced by contracting firms in which they are distributing afforestation kits in form of gum and Kenyan tree seeds to communities. Farmers are teams working in managing and maintaining the trees. Each village has its own woodlot. Woodend (Citation2003) states that social capital is obtained when community members organize themselves in groups towards achieving a certain goal. One Agricultural Extension Officer revealed that:

Community responsibility has been stimulated. The members are active participants in these programs. Such programs will go a long way in conserving natural forests for future generations. This will make tobacco farming sustainable.

Like the Kenyan experience, Strohm and Stoeffer (2006) viewed that farmer groups in Silibwet, Kenya, benefited from being a group member through networks that were built, they exchanged experiences, give advice to each other. Centralized contract farming has also enhanced social equality as it assisted the disadvantaged population in having a control over their social and economic lives. It has managed to incorporate the poor, women and orphans. In this study, 33% of the farmers were women and among them 50% were widows. One widow has this to say;

I am now able to take care of my children, clothing them, feeding them and educating them though I cannot manage university tuitions. Moreover, sufficient money for proper medication is still a problem though in sharing challenges are half solved. I am now also capable of contributing towards community development.

Women, especially widows are a vulnerable group. So, their involvement in such arrangements has enabled them to redress their challenges and reduce risks of abuse. In support of these findings is the involvement of women in centralized contract potato farming in Kenya. In Frigoken’s schemes in Kenya, 16,000–20,000 farmers participated, from which 80% were women. They have made farming their livelihood activity and are now able to meet some of their basic needs like food, clothes, housing and education (Strohm and Hoeffer, Citation2006).

Nevertheless, the recognition of centralized contract farming as a poverty reduction strategy is being dampened by problems associated with tobacco farming. The exploitation of child labour have emerged a societal problem in in-depth interviews. Children’s rights are violated. Children are sometimes deprived of their right to education in order to provide labour in the fields. Observations revealed that 100% of the farmers use family labour thus risking children to labour exploitation. Maertens and Swinnen (Citation2009) confirmed that centralized contract farming arrangements have been found to put greater unpaid labour demands with no proportionate allocation of benefits on women and children within a household. In interviews and FGDs farmers reiterated that:

If you hire much labour without estimating the expected income, you are likely to operate at a loss. So, am left with no option other than using my children. Moreover, that is where their school fees, their food and clothes are coming from, thus they have to work and at times during school days.

As alluded by the farmers, it is not certain whether the market prices will be favourable, so farmers rather use more of household labour including school children than hired. As a result, there are low school attendances during the tobacco reaping days as pupils are helping parents in the fields. Unlike what is happening in Cambodia, Minot and Ronchi (2015) farmers are given labour costs by the contracting companies and reduced the use of child labour in respect of child rights in developed countries, many studies in developing nations point to the social disruption caused by the use of children as labourers on tobacco farms. A recent report by Human Rights Watch (2018) on tobacco farming in Zimbabwe confirmed that, there is a high rate of absenteeism from school during the production season in smallholder producing areas. Child labour harms child health, physical development, and educational attainment (Hu & Lee, Citation2015). Children’s well-being is thus compromised. Poverty has also exposed children to sexual abuse hence making social sustainability veiled in obscurity.

8.3. Environmental sustainability and CCTSF

The researcher also gathered that centralized contract smallholder farming have posed serious threats to environmental quality. Deforestation, soil erosion and siltation emerged to be the main problem affecting the society. Interviews revealed that the majority of farmers use wood fuel in curing tobacco. This is attributed to financial constraints among smallholder farmers to who had no other sources of fuel like coal and electricity in most developing countries. Moreso, just like in most developing counties, predominantly parts of sub Saharan Africa, wood is understood as a free good with open access to everybody. The forests seem belonging to everyone and nobody is motivated to take the responsibility thus exposing them to overexploitation and depletion. Nhundu (2013) in Chazovachii (Citation2016) reiterates that public goods are no man’s resource, to the extent that there is no responsibility, accountability, and ownership spirit among beneficiaries. The overreliance on forest for tobacco curing have led to deforestation as farmers are using them to maximize short-term gains simultaneously depleting the use by the future generations. The rate of natural forests growth, reforestation and afforestation cannot keep pace with consumption rates. There is a fear of extinction of some tree and animal species. FGDs findings were confirmed by an Agricultural extension officer who uttered that:

There is enough evidence of overexploitation of the commonly used miombo woodlands in this area. Animals like leopards, vultures are slowly becoming rare species. If forest clearance is left unchecked, these species will disappear.

Chitongo (Citation2017) states that in Zimbabwe, the rising number of smallholder farmers venturing into tobacco production after the land reform programme has worsened environmental degradation in the country. Several forms of environmental pollution were reported by smallholder farmers, like air pollution and soil pollution. Through burning of the tobacco residues and curing of tobacco, smoke is released into the atmosphere, thereby polluting the air. Soil pollution results from the use of agrochemicals, which include insecticides, herbicides, fungicides and fumigants and the growth regulators that are applied to the tobacco plants at different stages of growth. In the end, the agrochemicals infiltrate and in the process contaminating soil and groundwater. FAO (2001) claimed that the loss of soil fertility to erosion is fifteen times higher in tobacco grown regions than non-growing. This is ascribed to soil exposure to bare surfaces from deforestation. The Mwarazi and Dora rivers in the area are the main sources of water for livestock and off-farm deeds such as fishing and irrigation. The rivers are heavily silted and polluted. This has impacted on water availability in the area and at the same time disturbing the marine ecosystem. One of the Agricultural Extension Officer has this to say:

Deforestation have led to siltation of dams and local rivers. Agrochemicals like fertilizers are being washed into rivers thus leading to rapid algae growth in Mwarazi Dam. According to 2018 ZINWA statistics, the dam capacity have fallen by 10% due to siltation

In line with this is the siltation of Punjab River in the Shandong Province of China, where Singh (Citation2002) states that the siltation of the river was a result of soil erosion and stream bank cultivation. The environmental sustainability of centralized contract tobacco farming in the area is irritating. Pollution of water, air and soil is a threat to sustainability. Biodiversity loss is at risk as some plants and animal species are becoming rare. Though afforestation programmes are being put into practice, the rate cannot keep pace with the rate of consumption. Thus, afforestation and reforestation are just a drop in the ocean in redressing deforestation.

Documents review from a local health centre revealed that, respiratory diseases prevalence are on the rise in the area. Secondary data obtained from Erra Mine clinic show an increase in respiratory infections among tobacco farmers. The respiratory infections are attributed to the use of agrochemicals without proper protective clothing. In an interview, one farmer said that:

Our contractors offer us agrochemicals but without the protective clothing. Our health is deteriorating as we inhale toxins during spraying, fertilizing, curing, steaming and grading.

In line with this is the increase in respiratory infections in the Kandara District of Kenya where the issue of protective clothing is not taken seriously by contracting companies and the farmers themselves (Wright et al., Citation2019). This is greatly affecting human capability and capacity in society.

8.4. Economic sustainability

Agriculture is the backbone of economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa, since on average it accounts for 70% of overall employment, 40% of total exports, and a third of the region’s GDP (Muir-Leresche, Citation2006). About 75% of the poor in Southern Africa are rural mostly smallholder farmers who rely mostly on agriculture for their livelihoods (Salami et al., Citation2010). Hence, efficiency and effectiveness in this sector is a prerequisite for national development. Centralized tobacco contract farming has enabled smallholder farmers increase their household incomes. Farmers during FGDs acknowledged that centralized tobacco farming have improved their incomes. The income comes in bulky thus allowing them to acquire higher order goods and services. Farmers are investing in farm implements like draught power, ploughs, harrows, scotch carts though the income is still insufficient to fully meet some demands. Farmers lack financial independence and their budget is insufficient to meet demands of the next season. No wonder why they lack the ability to grow out of contract. The farming is not self-sustaining thus economically unsustainable.

From the Pearson correlation on , there is a weak positive relationship between expenditure and income. A correlation coefficient of 0.2 denotes that an increase in expenditure has little influence on increasing income. Under normal circumstances, high expenditure should translate to higher income; this is not the case with the smallholder farmers. This is attributed to corruption among the tobacco buyers and other external factors like climatic conditions, edaphic factors, and quality management and farmers effort as economic men.

Table 1. Correlation of income and expenditure

However, contracting firms allude that, the contract arrangements are economically viable. They are getting a profit of 40%-60% per year. They buy tobacco at an average price of 3 USD per kg and export at an average price of 7 USD per kg thus allowing them to expand and venture into new areas. However, extension officers revealed that the exploitative nature of contract arrangements enable them to operate at a profit at the expense of smallholder farmers. Such intermediary role by contracting firms concurs with Chazovachii (Citation2016) that intermediaries manipulated smallholder farmers as they lack of access to urban and lucrative markets the intermediaries had.

With the thrust of transforming the livelihoods of smallholder tobacco farmers through the Capability Theory by Sen (1989), centralized contract tobacco farming has increased the resource base of smallholder farmers. The level of deprivation has been reduced through increased social interaction with contracting firms and other middlemen and increased their income levels. The vulnerability levels of household prior centralized contract farming have been reduced. The risks, seasonality, shocks, which characterized smallholder farmers, have been reduced by the financial, social, human, physical and natural assets accrued in centralized contract farming. Inspite of the empowerment with endowments and entitlements through aforementioned assets, smallholder tobacco farmers are still experiencing challenges on their health, as a result of agro-chemicals and smoke. This has compromised the human capital of the economically active farmers. Natural assets are overexploited, and women and child labour abuses have compromised social capital.

What is lacking on centralized contract farming for the capability theory to succeed are policies, institutions and processes that are African at the level of government and private sector structures. The contract farming policies in place is a continuity of the inherited colonial legislations that does not capture a new farmer in tobacco after the year 2000 fast-track land reform programme. The conditions characterizing centralized contract farming provisions have an elite capture which compromises or ignored the incomes, well-being, vulnerability and sustainable use of natural resource base. So for centralized contract farming to capacitate the smallholder farmer with ant-African values, efforts are thrown to the dustbin of development.

9. Conclusions and recommendations

The study revealed that conditions characterizing centralized contract tobacco farming are unsustainable. Institutionally, contract arrangements are manipulative and are unwelcome to farmers. Economically, contracting firms find it viable as they obtain more profit at the expense of smallholder farmers. Although farmers are assured of inputs, extension service and a market for the product, the contract terms are characterized by transaction cost, uncertainty and information asymmetry. More so, although financial and physical assets ownership have been increased, human, natural and social capital is a challenge due to institutional barriers. Shocks, stresses and seasonality still characterizes the vulnerability context of the smallholder farmers as society has been exposed to child and women abuses, food insecurity, and social decay through prostitution, robbery and conflicts. With this, the study therefore recommends an increased participatory action and learning in crafting and implementing contract terms by farmers, state and non-state actors. Policies, institutions and processes needs to take into consideration the coming in of the new African farmer who has no endowments and entitlement base for sustainability to be realized.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bernard Chazovachii

Bernard Chazovachii is a researcher, an Associate Professor and executive Dean of the Julius Nyerere School of Social Sciences at Great Zimbabwe University. His research areas are rural and urban livelihoods, smallholder farming sustainability and poverty reduction.

Cashave Mawere is a Graduate Student in Populations Studies with research interests in smallholder tobacco contract farming at Great Zimbabwe University.

Leonard Chitongo is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Rural and Urban Development, Great Zimbabwe University. He has a passion on issues which affect human development. His research interests are in local governance and rural and urban development.

References

- Alkire, S. (2007). Choosing dimensions: The Capability Approach and Multidimensional Poverty. QEH: Oxford University.

- Chamahwinya, J. (2016). An assessment of the suitability of contract farming models being implemented in Zimbabwe and their impact on agricultural growth. MCA Dissertation. Midlands State University.

- Chazovachii, B. (2016). Conditions Characterizing the Sustainability of Smallholder Irrigation Schemes: The Case of Bikita District. SA: University of Free State.

- Chitongo, L. (2017). The Efficacy of Smallholder tobacco farmers on Rural Development in Zimbabwe. PhD thesis, University of the Free State.

- Chitongo, L | Sandra Ricart Casadevall (Reviewing editor). (2019). Rural livelihood resilience strategies in the face of harsh climatic conditions. The Case of Ward 11 Gwanda, South, Zimbabwe, Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1617090

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Dube, L., & Mugwagwa, K. L. (2017). The Impact of Contract Farming on Smallholder Tobacco Farmers’ Household Incomes: A Case Study of Makoni District, Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe. Scholars Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, 4(2), 79–14. doi:10.21276/sjavs.2017.4.2.6

- Eaton, C., & Shepherd, A. W. (2001). Contract farming: Partnerships for growth. In FAO Agricultural Services. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO Agricultural bulletin 145.

- Ghosh, P., Sanchita, H., Samik, S., Khan, N., & Asmeen, D. (2009). Rajasthan - Milking profits from dairy farming. In Livelihoods learning series; series 2, note no. 1. World Bank Group.

- Hu, T. W., & Lee, A. H. (2015). Tobacco Control and Tobacco Farming in African Countries. Journal of Public Health Policy, 36(1), 41. doi:10.57/jphp.2014.47

- Human rights watch. (2018). Tobacco work harming children. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/04/05/zimbabwe-tobacco-work-harming-children

- Kaczan, D., Arslan, A., & Lipper, L. (2013). Agricultural Development Climate-Smart Agriculture? A Review Of Current Practice Of Agroforestry And Conservation Agriculture In Malawi And Zambia, Agricultural Development Economics Division Food And Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations ESA Working Paper No. 13–07.

- Macdonald, P., & Korb, R. (2011). Global Retail Chains and Poor Farmers: Evidence from Madagascar, World Development, 37(11), 1728–1741.

- Maertens, M., & Swinnen, J. F. M. (2009). Trade, standards and poverty: Evidence from Senegal. World Development, 37(1), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.04.006

- Masvongo, J., Mutambara, J., & Zvinavashe, A. (2013). Viability of tobacco production under smallholder farming sector in Mount Darwin District, Zimbabwe. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 5(8), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE12.128

- Minot, N., & Ronchi, A. (2011). Contract farming in sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunities and challenges. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Moyo, M. (2014). Effectiveness of a contract farming arrangement: A case study of tobacco farmers in Mazowe district in Zimbabwe. Research assignment presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Development Finance at Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Muchengeta, C., & Badza. (2010). Research Methods and Statistics. Open University.

- Muir-Leresche, K. (2006). Agriculture in Zimbabwe. In M. Rukuni, P. Tawonezvi, & C. Eicher (Eds.), Zimbabwe’s agricultural revolution revisited (pp. 99–114). University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- Murugan, G. (2003). Entitlements, Capabilities and Institutions: Problems in Their Empirical Application’. Paper prepared for presentation in the conference on Economics for the Futureunder the auspices of Cambridge Journal of Economics, University of Cambridge, 17–19, September 2003.

- Mutami, C. (2015, Iss. 2 ( 2015). Smallholder Agriculture Production in Zimbabwe: A Survey, Consilience. The Journal of Sustainable Development, 14(2), 140–157.

- Ramaswami, P., Bharat, S., Birthal, V., Singh, M., & Joshi, P. K. (2006). Efficiency and Distribution in Contract Farming: The Case of Indian Poultry Growers. IFPRI.

- Rehber, E. (2007). Contract Farming: Theory and Practice. ICFAI University Press.

- Ruben, R., Wesselink, M., & Saenz, F. (2001), “Contract Farming and Sustainable Land Use: The case of small scale pepper farmers in Northern Costa Rica”. Paper presented at the 78th EAAE Seminar: Economics of Contracts in Agriculture and the Food Supply Chain, Copenhagen, June 15-16.

- Salami, A., Kamara, A. B., & Brixiova, A. (2010). Smallholder Agriculture in East Africa: Trends, Constraints and Opportunities. Tunis, Tunisia: Working Papers Series N 105 African Development Bank.

- Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Claredon Press.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Setboonsarng, S. (2008). Global Partnership in Poverty Reduction: Contract Farming and Regional Cooperation. Asian Development Bank.

- Singh, S. (2002). Contracting out solutions: Political economy of contract farming in the Indian Punjab. World Development,301, 1621–1638. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00059-1

- Strohm and Hoeffer. (2006) . Contract Farming in Kenya: Theory, Evidence from selected Value Chains, and Implications for Development Cooperation. PROMOTION OF PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT IN AGRICULTURE Ministry of Agriculture and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH.

- Swinnen, J. F. M., & Maertens, M., (2006). Globalization, privatization, and vertical coordination in food value chains in developing and transition countries. Leuven Interdisciplinary Research Group on International Agreements and Development. Working paper No. 12.

- TIMB(2019)Tobaccosalesreport https://www.timb.co.zw/storage/app/media/2019%20Weekly%20Report/weekly-bulletin-30-week-ending-26-july.pdf assessed 18 November 2019

- Whiteside. (1998). In W. Alan (eds.), Whiteside: Chapter 1.2 Health, Economic Growth, and Competitiveness in Africa. World Economic Forum within the framework of the Global Competitiveness Programme.

- Woodend, J. J. (2003). Potential of contract farming as a mechanism for the commercialization of smallholder agriculture the Zimbabwe case study. Food and agriculture Organization.

- World Bank. 2019. World Development Indicators (https://data.worldbank.org/).

- Wright, T., Adhikari, A., Yin, J., Vogel, R., Smallwood, S., & Shah, G. (2019). Issue of Compliance with Use of Personal Protective Equipment among Wastewater Workers across the Southeast Region of the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2, 1–18.

- Zimbabwe Human Development Report. (2003). https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/hiv-aids/2003-zimbabwe-national-human-development-report.html