Abstract

Card payments in South Africa continue to be a predominant part of the National Payments System in an evolving payments ecosystem. Due to the growing volume of electronic payments, the monetary strain of credit card fraud is turning into a substantial challenge for financial institutions and service providers, thus forcing them to continuously improve their fraud detection systems. This article attempts to explain the Modus Operandi (MO) of perpetrators of credit card fraud in the Vaal Region in South Africa. The article begins with an examination of the extent of the challenge and response by the relevant stakeholders, especially the Criminal Justice System (CJS). This study was carried out utilising a qualitative research approach with a convenience, purposive and snowball sampling techniques. Thirty-nine (39) interviews were conducted to solicit the views of the participants and police investigators from Vanderbijlpark, Sebokeng, Sharpeville and Vereeniging police stations, members of the community, and victims of credit card fraud were interviewed. These interviews were analysed according to the phenomenological approach, aided with the inductive Thematic Content Analysis (TCA) to identify the participants’ responses and themes. The findings indicated that the extent of credit card fraud in Vaal region is reaching alarming rates. Based on the findings, the authors provided recommendations such as: police investigators being taken for regular workshops and training on how to investigate sophisticated methods used by perpetrators such as technology, awareness in the society about credit card fraud should be prioritised and enhanced.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Clear understanding of the MO of perpetrators for credit card fraud in the Vaal region by the local South African Police Service (SAPS) officials, victims of this scourge and public members of Sebokeng, Vanderbijlpark, and Sharpeville remain of utmost importance. It is pivotal to notes that MO of credit card fraud differ timely, thus, ways of combating this practice also differs, and circumstances that are applicable to one incident are not applicable to the next similar problem. With this study, the local SAPS will improve their respective investigative capabilities and acquire more knowledge, improved skills, methods and techniques in terms of taking complainant’s statement in card fraud cases. It is hoped that this study will contribute to a higher competency level during the taking of statements relating to card fraud and statement taking in general. The gathered information can also be used by victims and public members to learn the associated realities of this crime and to provide more detailed information about this crime to the responsible local SAPS members to ease their investigation procedures.

1. Introduction

According to (Ishu & Mrigya, Citation2016, p. 1), credit card is a thin handy plastic card that contains identification information such as a signature or picture, and authorizes the person named on it to charge purchases or services to his account—charges for which he will be billed periodically. A credit card is a convenient method of payment, but it does carry risks . The enormous growth in the use of credit cards has resulted in high levels of credit card fraud. The use of credit cards has become a way of life in many parts of the world. There is a rapid growth in the number of credit card transactions which has led to a substantial rise in fraudulent activities (Ishu & Mrigya, Citation2016, p. 2). South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2017, p. 1) concurs that today, credit cards are used like cash. All credit cards have one thing in common, namely that the bearer can obtain something of value simply by presenting the card. However, credit card fraud results in high losses both for the banking industry and consumers and seems to be increasing. Technological advances have allowed the perpetrators to produce counterfeit cards that resemble the genuine card so closely that it is difficult for shopkeepers, tellers, SAPS and bank investigators to identify a fraudulent card.

The trends in bank card fraud on South Africa issued cards show credit and debit card fraud losses amounted to about R779 million in 2017 (Premium, Citation2018, p. 12). Card payments in South Africa continue to be a predominant part of the National Payments System in an evolving payments ecosystem (South African Banking Risk Information Centre, Citation2017). Whereas the South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2019) affirms that digital banking fraud incidents across all platform increased by 20% from 2018 with a gross loss increase of 8%. SABRIC reports that Vishing is the most prominent modus operandi in banking app fraud but that there were no reports of banking app software being compromised to commit fraud. Phishing remains the most effective way of obtaining banking login credentials. The debit card fraud losses decreased by 15,7% but there was an increase of 16,2% relating to credit card transactions in South Africa.

Due to the growing volume of electronic payments, the monetary strain of credit-card fraud is turning into a substantial challenge for financial institutions and service providers, thus forcing them to continuously improve their fraud detection systems. As businesses continue to evolve and migrate to the internet and money is transacted electronically in an ever-growing cashless banking economy, accurate fraud detection remains a key concern for modern banking systems. It is not only to limit the direct losses incurred by fraudulent transactions but also to ensure that legitimate customers are not adversely impacted by automated and manual reviews (Johannes et al., Citation2018, p. 2).

2. Credit card fraud detection processes

Despite increased media coverage regarding the prevalence of credit card fraud and the means and methods used by organised criminal groups, the evidence base remains underdeveloped. The glaring knowledge gaps confronting the policymakers as well as role players, amongst others, are the lack of empirical studies and research into the extent of the challenge facing the role-players dealing with credit card fraud. Ishu and Mrigya (Citation2016, p. 2) concur that there are lots of issues that make this procedure tough to implement and one of the biggest problems associated with fraud detection is the lack of both the literature providing experimental results and of real-world data for academic researchers to perform experiments on.

Card payments constituted 61% of all payment transactions processed in South Africa during 2016, with over 60 million Debit Cards and nearly 8 million Credit Cards in circulation. The drive to replace magstripe cards with more secure and improved Europay, Mastercard, and Visa (EMV) chip and Personal Information Number (PIN) capable cards continues and over 65% of Debit Cards and more than 90% of Credit Cards are currently chipped (Payment Association South Africa [Online], Citation2016, p. 5). According to South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2017, p. 1), debit card fraud still amounted to R342.2 million in loss. Credit card fraud totalled at R436.7 million, bringing the overall loss up to almost R800 million. According to the report, credit-card-related Card–Not–Present (CNP) fraud is still the leading contributor to gross fraud losses in South Africa. CNP fraud accounted for 72.9% of the losses on South African-issued credit cards.

Gross fraud losses on South African-issued credit cards increased by 1.0%, from R434.0 m in 2016 to R436.7 m in 2017. In 2016, 50.6% of all credit card gross fraud losses occurred at merchants outside the borders of South Africa. This percentage increased to 53.4% in 2017. The remaining 46.6% of transactions occurred at merchants in South Africa. The CNP fraud was the leading contributor to the gross fraud losses on South African-issued credit cards in 2017, with 72.9% of the overall credit card gross fraud loss (R436.7 million) attributed to CNP fraud. The CNP credit card gross fraud losses increased by 7.4% from R296.4 million in 2016 to R318.4 million in 2017. A total of R200.0 million (85.8%) of the overall gross fraud losses (R233.2 million) occurring outside South Africa can be attributed to CNP credit card fraud. Lost and/or stolen cards are mainly used in South Africa with only 23.9% of the losses related to transactions outside South Africa. Gauteng accounts for 57.2% of the credit card gross fraud losses and is the highest among all the provinces (South African Banking Risk Information Centre, Citation2017, p. 1).

In our postmodern society, enterprises and public institutions have to face a growing presence of fraud initiatives and need automatic systems to implement fraud detection (Delamaire et al., Citation2009, p. 32). Since the number of fraudulent transactions is much smaller than the legitimate ones, the data distribution is unbalanced, that is, skewed towards non-fraudulent observations. Another problematic issue in credit card detection is the scarcity of available data due to confidentiality issues that give little chance to the community to share real datasets and assess existing techniques.

shows that the Gauteng (GP), Western Cape (WC) and KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) accounted for 85.9% of all credit card gross fraud losses in South Africa. GP accounts for 57.2% of the credit card gross fraud losses, followed by the WC with 16.1% and KZN with 12.7%. All provinces showed increases during 2016 with the exception of WC where a decrease of 11.8% was observed. The biggest increases, when comparing 2015 and 2016, occurred in the Eastern Cape [EC] (148.0% from R3.5 m to R8.7 m), North West [NW] (127.9% from R1.3 m to R2.9 m), Northern Cape [NC] (95.7% from R132 770 to R259 875) and Free State [FS] (89.9% from R721 111 to R1.4 m) (Payment Association South Africa [Online], Citation2016, p. 17).

Figure 1. Provincial geographical distribution of credit card fraud losses

It is obvious from that seven years’ projection of credit card fraud in each of the nine Provinces of South Africa. In 2016, GP Province represented 57.2% of charge card misrepresentation, which is the higher rate appeared in all Provinces. It is consequently the researchers centered their examination inside three chosen areas of Vaal Region, which falls under GP Province. This table (1) indicates how clients and banks lose a great many rands over charge card misrepresentation in South Africa. Unmistakably role-players managing charge credit card fraud are truly doing combating to diminish this scourge, this impacts the battling economy of the nation. Culprits of this scourge utilize propelled strategies and procedures to make it hard for role-players to distinguish and research the issue, while their propelled strategies and methods make it simple for the clients to be progressed towards becoming exploited people.

Fast forwards 2019, the South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2020) report shows that total gross fraud losses for South African issued cards increased by 20.5% from 2018 (R890.3 million), to 2019 (R1.07 billion). Credit card fraud increased by 16.2% when comparing 2019 (R217.2 million) to 2018 (R186.8 million). Notably, debit card fraud decreased by 15.7% when comparing 2019 (R211.3 million) to 2018 (R250.9 million).

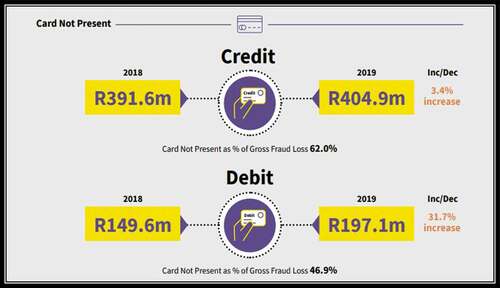

From , it can be deduced that in 2019, two-thirds (66.6%) of fraud on South African issued credit cards took place outside the country’s borders, while half (50.6%) of South African issued debit card fraud took place in the country. In 2019 Card Not Present (CNP) fraud [i.e. CNP fraud is a fraudulent transaction where neither the card nor the cardholder is present whilst conducting the transactions] amounted to 62% of gross fraud losses on South African issued credit cards, followed by False Applications (27.1%) and Counterfeit (5.7%) fraud (South African Banking Risk Information Centre, Citation2020).

Figure 2. Gross fraud (Credit and debit)

indicates that in 2019 CNP fraud with a debit card amounted to 46.9%, followed by Lost and/or Stolen (38.7%) and Counterfeit (12.0%), South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2020).

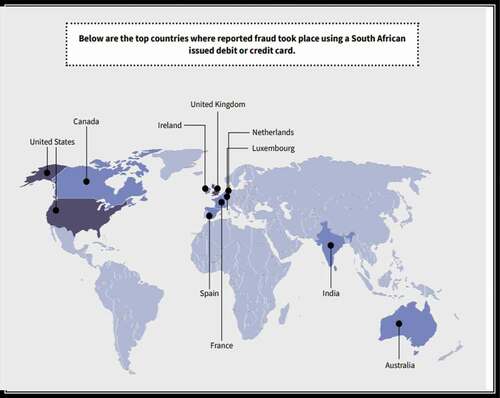

Figure 3. Top countries where reported fraud occurs using South African credit or debit card

When looking at indicating the places where this lost/stolen card fraud took place, South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2020) shares that the most common hotspots include Tollgates, ATMs, Drinking places, Liquor stores and Supermarkets. Moreover, the places where CNP took place, South African Banking Risk Information Centre (Citation2019) highlights that the most common hotspots included: Hotels, Business services, Taxi/cabs, Computer software stores, Dating and escort Service, Travel agencies, Utilities (i.e. Electricity) and Airlines.

Objectives of this study were to determine the modus operandi of perpetrators of credit card fraud, to identify the factors that hinder the SAPS to effectively combat credit card fraud, to determine the extent and nature of credit card fraud, to identify the preventative strategies used by the SAPS and SABRIC to combat credit card fraud, to determine the profile of perpetrators of credit card fraud.

3. Research methodology

This study was exploratory in nature; a purposive sampling method was used following a qualitative descriptive methodology. Thirty-nine interviews were conducted to solicit the views of the participants and police investigators from Vanderbilpark, Sebokeng, Sharpeville and Vreeniging police stations, members of the community, and victims of credit card fraud were interviewed. The interviews were analysed according to the phenomenological approach, coupled with inductive TCA to identify the participants’ responses and related themes. The reason for this choice was to identify key or knowledgeable participants about credit card fraud in the Vaal Region.

Overall; 39 participants formed part of this study. About 28 participants were purposively selected comprising of the SAPS Constables, Sergeants, Warrant officers, and Captains. Of these, eight were females and 20 males. Their experiences ranged between 10 years to 27 years. The remaining number of participants were two victims of credit card fraud, which were selected using snowball sampling and the convenience sampling was adopted to select seven members of the public from Sebokeng, Vanderbijlpark and Sharpeville. The perceptions, beliefs, and experiences of participants were collected using interview guides with open-ended questions by the first and second authors of this paper. The in-depth interviews were semi-structured, and a more relaxed, informal interviewing method was adopted for rapport and trust building. The interviews lasted for 60 to 90 minutes.

The Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted with 19 participants to gain new insights but also to triangulate information collected during the interviews in order to increase validity. Both interviews and the FGD were conducted privately at the safe place as agreed between the participants and the authors. A voice recorder was used to record information during the interviews and FGD. The in-depth interviews and FGD were conducted in the local languages spoken in Gauteng Province (IsiZulu, English and Sesotho) and later translated into English. The Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were also utilised during data collection and 12 participants formed part of the KII. Translator for other official languages was available but none of the participants felt the need, as they were comfortable in expressing themselves in English. The English translation process focused more on getting relevant meaning than exact translations of the verbal information received.

All interviews were transcribed and then studied several times in conjunction with the corresponding non-verbal clues given by the participants using the stated inductive TCA. Field notes provided further guidance during the data-analysis process, supporting the process of dividing the data into identifiable themes. During the process, the results were verified continuously by means of audio and visual recordings of the interviews, which proved very helpful as a means of ensuring data quality. This also provided the opportunity to follow a process by which the different themes could be compared and relations between the different themes could be studied, so as to become aware of patterns that could be categorised. A summary of the main data categories and the sub-categories is presented in the form of themes. Two processes were followed to ensure effective data control. Firstly, all questions asked were written down and then studied several times. Secondly, data results were compared with existing literature, to identify similarities or discrepancies that might call for further research in future. In addition, field notes that were also written down provided further guidance during the data-analysis process, supporting the process of dividing the data into identifiable themes.

4. Study findings and discussions

The referencing method for the interviews in this study comprised a numerical sequence, and an example of this notation is as follows: FGDs/KIIs (5:1:2). The first wordings refer to the “FGDs/KIIs” as initial indicated. The first digit (5) refers to the folder number in the voice recorder, the second digit (1) is the interview number in the-said folder, while the third digit (1) is the sequence in which the cited interview was conducted. Importantly; data analysis of this study yielded five themes identified as follows:

4.1. Modus Operandiof perpetrators of credit card fraud in the Vaal Region

It should be noted that findings such as those given below were similar among all the selected participants, regardless of the study location. Examples of some of the remarks regarding their experiences in terms of dealing with cases of credit card fraud were similar. The participants, when asked about the MO of perpetrators of credit card fraud in Sebokeng, Sharpeville and Vanderbijlpark, explained that perpetrators use advanced technological tools to commit this crime and to confuse the victims as well as the role-players involved in dealing with this crime. They emphasised that the perpetrators use fake cards, technological tools at the Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), work with bank officials to get information of the potential targets. These are some of the responses from the participants (related verbatim):

Copying a credit card and somehow getting hold of the secret pin of the user. Vendors charging more money from the user’s credit card compared to what they have agreed to and without the latter being aware of the charged money (FGDs-10:2:11)

The perpetrators in most instances try by all means to look for the pin of the user, it can be in the ATM, at the shopping malls when users pay, it can be in the garage when the user pay for the fuel of their car. (FGDs-10:2:11)

I know a guy who works at one of the garages here in Sebokeng who works with the perpetrators of credit card fraud, he watches the pin of the users as they pay for the fuel of their cars and also the perpetrators use him to clone credit cards”. This is a serious network, it involves people who works in the bank, they help the perpetrators by identifying those clients with lot of money and the perpetrators monitor their lifestyle, what they do where do they buy and the bank officials also provide the perpetrators with the residential address of the potential victims. (FGD-10:2:12)

The perpetrators after stealing or cloning the credit card, for them to use money in those credit cards they work with the owners of the designer clothes or clubs to buy alcohol (FGD-10:2:12)

The perpetrators use the stolen or cloned credit cards in the designer clothes shops or clubs, they work with shop owners or club. They buy alcohol and spend on it. For example, this is how they do it, they go to the night club swipe the stolen or cloned credit card, maybe they use R50 000 over a weekend there and the owner of club will give them R30 000 back, they swipe R50 000 without taking any alcohol. That means the owner of the club is going to get R20 000. The perpetrators carry lot of credit cards with them wherever they are and we know this people who terrorise the communities but we can’t talk because they work with the police, so we are scared that they victimise us or target us. (KII-22:1:3)

The perpetrators put the chips in the ATM’s which makes the credit card not to come out, then after the victim leave the ATM then perpetrators go to the ATM and get the credit card (KII-22:1:3)

I am the victim of credit card fraud, I was at the ATM and there was a car parked next to the ATM, it was very early in the morning. After I went to the ATM to get money, the credit card did not come out, I thought it was swollen by the ATM then I thought I will go to work then during lunch time I would go the bank and report it. To my surprise after I leave the ATM, one man went to the ATM then few minutes they drove away and immediately I started getting notifications in my phone that money was transferred from my credit card, it showed that it was transferred from different locations. When I went to the police to report, they told me that I need to open the case and its difficult for them to investigate such cases, they advised me to go and report the incident at the bank, they said along as the bank can get pay me my back then everything will be fine (KII-22:1:3)

4.2. Strategies to combat credit card fraud

The participants from the SAPS in all three areas clearly indicated that they do not have a strategy to investigate credit card fraud as the perpetrators of this crime use advanced technological techniques and tools. They highlighted that they do not have skills, technological tools and they lack resources to investigate cases of credit card fraud. The following were some of their responses quoted verbatim, and no corrections of their language were made:

The SAPS do not have the resources to deal or investigate the cases of credit card fraud. The suspects use technology to commit this crime and they have advanced skills which we don’t have, we don’t attend workshops or extra training with regards to deal or investigate this crime (KII-22:1:4)

I have fifteen years in the police, and I started investigating the cases of credit card fraud eight years ago, I don’t remember myself going to the training or workshop on how to investigate specifically credit card fraud. So there is no strategy that I can say SAPS have in place or we have a booklet that we use to or follow to investigate (KII-22:1:5)

Well, we do not have a proper strategy that we are using or following, as the investigating officers in SAPS we just help each other when it comes to this crime but most of the time, we don’t solve the majority of credit card fraud cases because we really do not have resources to trace the perpetrators, we also lack the skills to investigate this crime (KII-22:1:6)

In terms of understanding the “Management and implications for policy,” this study reveals that expertise about techniques to detect credit card fraud, investigate and to prosecute perpetrators is yet to be realised in South Africa. Reports of the arrest and conviction of credit card fraud perpetrators are frequent yet not from the CJS. The implications based on the findings on credit card in South Africa are compelling and require concerted effort from all relevant stakeholders within the CJS. Although SAPS, due to competing priorities, has not yet developed the strategies and methods to investigate, identify and solve the cases of credit card fraud, it is essential that the officers dealing with cases of credit card fraud be equipped and capacitated with necessary investigating skills and methods to successfully solve deal with this problem. It is crucial that the training of SAPS officials include technological tools, methods to detect and investigate cases of credit card fraud.

Comparing the number of prosecutions with the number of identified victims would highlight the extent of the problem. The release of official statistics, though argued as unreliable, would nevertheless, provide as an awareness regarding the MO utilised by perpetrators, reported nor detected cases in relation to conviction rate to the prospective victims and the public. This would assist all role-players, to develop minimum standards concerning the response of CJS to credit card fraud cases as well as improved services to the victims especially with regard to insurance claims. From the psychological and emotional trauma, to the economic and political implications of unabated crime, the impact on individuals and society is clearly destructive and unacceptable.

A lack of role clarity from the relevant role-players related to servicing victims, and uncertainty regarding what measures work and what do not have contributed to a lack of systematic and consistent implementation, and sustainable action. Each calls for different dynamics in policy and programme planning. An improved cohesion between relevant role players would go a long way to align the day-to-day tactics into a long-term technological strategies and national responses, sharing from their own experiences and identifying elements that constitute best practices. A multi-disciplinary approach between all role-players will enhance the successful detection, investigation and prosecution of credit card fraud cases.

The MO involved during the credit card fraud can be difficult for third parties to understand, while victims can find it difficult to comprehend what has happened to them, or to discuss it with or explain it to others. Victims may appear to those around them, even support persons, to be stupid or irresponsible. The stigma attached to the victims has a significant and ongoing impact on their lives, including in the financial stress and constraints. The long-term consequences of credit card fraud for victims are complex and depend on many factors, with no guarantee of recovery. Re-victimisation is often a further consequence of the experience. The following emerging themes were identified in this study: (1) MO of perpetrators of credit card fraud, (2) lack of knowledge and skills to investigate credit card fraud, (3) lack of awareness in the region around credit card fraud and (4) lack of resources to deal with credit card fraud.

5. Emerging themes and discussion

This study presents the following emerging themes as discussed herewith:

5.1. Theme 1:Modus operandi of perpetrators of credit card fraud

When asked about the modus operandi of credit card fraud, the majority of participants highlighted that perpetrators use different methods which are very complex and advanced. The methods that were used by perpetrators among others were to put the chip at the ATM record the information of the victim and with that information perpetrators are able to withdraw money from the bank account of the victim.

5.2. Theme 2: Lack of knowledge and skills to investigate

The participants highlighted that the SAPS do not have capacity and lack skills to investigate cases of this nature. Many victims of this crime highlighted that they have reported the cases to the SAPS but the cases remained unsolved due to lack of skills. The majority of participants from the SAPS did not shy away that this crime require technology to investigate it and that they do not have technology on their disposal to investigate such cases.

5.3. Theme 3: Lack of awareness in the region around credit card fraud

Majority of the participants from the community highlighted that they did not know that credit card fraud exists in Vaal until they become victims of it. They explained that majority of the members of the community do not know about this scourge and explained that believe that many people will still be victims of credit card fraud. The SAPS members explained that they do not conduct awareness campaigns as their budget is very limited.

5.4. Theme 4: Lack of resources to deal with credit card fraud

The participants highlighted that the SAPS do not have resources to investigate credit card fraud, even the population from the SAPS explained that they do not have resources. The SAPS open a case just for the purpose of insurance and they know exactly that they cannot solve the cases of credit card fraud.

6. Recommendations and conclusion

This study recommends that the Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras should be made available in the ATM, where incidents of credit card fraud are taking place. In addition, the police be visible in the areas which are most prevalent to credit card fraud. This study recommends that the SAPS members should be taken for regularly training in order for them to be able to properly investigate the cases of credit card fraud. They should be taken to advance training that will enable them to investigate sophisticated cases involving high technology on credit card fraud. The study also recommends that SAPS should conduct regular awareness campaigns to ensure that the communities around Vaal Region are aware of the scourge of credit card fraud. This study also recommend that the SAPS should be capacitated with adequate resources and skills to enable them to be able to investigate credit card fraud.

This study concluded that credit card fraud is very high in the selected areas of Vaal Region, the modus operandi of perpetrators of credit card is very different as the perpetrators try different tactics to deceive their victims and also to ensure that it is extremely difficult for the SAPS investigate. If the SAPS can join hands with the communities and other stakeholders, this scourge of credit card fraud can be reduced.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Witness Maluleke

Dr Motseki Morero is attached to the Department of Legal Sciences, Vaal University of Technology (VUT), South Africa, while Mr Rakgetse John, Mokwena works at University of South Africa (UNISA), under the Department of Police Practice, Prof Dr Witness Maluleke is based at University of Limpopo and University of South Africa, affiliated to the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice and Department of Police Practice, College of Law respectively and Dr Siyanda Dlamini is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for General Education at Durban University of Technology (DUT), South Africa. All authors formatted, proofread, as well as provided technical presentations of this manuscript in compliance with the author guidelines.

References

- Andrea, D. P., Olivier, C., Yann, B., Serge, W., & Gianluca, B. (2014). Learned lessons in credit card fraud detection from a practitioner perspective. Expert Systems with Applications, 41(1), 4915–11. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2014.02.026

- Delamaire, L., Abdou, H., & Pointon, J. (2009). Credit card fraud and detection techniques: A review. Banks and Bank Systems, 4(2), 57–68.

- Ishu, T. M., & Mrigya, M. (2016). Credit card fraud detection. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer and Communication Engineering, 5, 2278–1021.

- Johannes, J., Granitzer, M., Konstantin, Z., & Sylvie, C. (2018). Sequence classification for credit-card fraud detection. Expert Systems with Applications, 100(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2018.01.037

- Payment Association South Africa [Online]. (2016). Card fraud 2016: Protect your card and information at all times. Retrieved July 18, 2019, from https://www.sabric.co.za/media/1038/2016-card-fraud-booklet.pdf

- Premium, B. L. (2018) Bank card fraud climbing towards R800-million. 29 April, BusinessLive [Online]. Retrieved September 01, 2020, from https://www.businesslive.co.za/bt/money/2018-04-28-bank-card-fraud-climbing-towards-r800-million

- South African Banking Risk Information Centre. (2017). SABRIC digital banking crime statistics. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://www.icfp.co.za/article/sabric-digital-banking-crime-statistics.html

- South African Banking Risk Information Centre. (2019). SABRIC digital banking crime statistics. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://www.icfp.co.za/article/sabric-digital-banking-crime-statistics.html

- South African Banking Risk Information Centre. (2020). These are the most common banking scams in South Africa. 27 June, BusinessTech [Online]. Retrieved September 09, 2020, from https://businesstech.co.za/news/banking/409869/these-are-the-most-common-banking-scams-in-south-africa