?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The indicators of the internal resources factors in the small-scale agro-processing in South Africa have a complicated cluster of networks, inventory, and trademarks compared to the commercial agro-processing sector. However, it has been identified that the internal resources endowment of small-scale agro-processors is extremely weak. The study was carried out in the five provinces of South Africa, and the sample size was made up of 503 respondents. Face-to-face interviews were employed to collect the data in a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design, where quantitative data collection was through closed-ended questionnaires, and qualitative was through focus group sessions. The results revealed that the network (β = 0.440, p = 0.000) forms an integral part of the factors that influence the small-scale agro-processors internal resource status in these enterprises. While trademark (β = 0.142, p = 0.000) and inventory (β = 0.138, p = 0.000) were found to have second and third impact respectively. As a result of the reported weakness in the business networks in the small-scale agro-processing enterprises, it is recommended that these enterprises form lobby organizations that will enable the internal resources base of these enterprises.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The marginalization and exclusion of smallholder farmers have plagued the South African economy. Despite the policy reforms post-1994, small-scale agro-processors still face high levels of disempowerment attributed to ruminants of past colonial policies. As a results, their contribution to the economy is impaired by their internal resources endowment. The purpose of this study is to analyze the impact of networks on the internal resource status of small-scale agro-processors in South Africa. The study revealed that network is central in influencing the internal resource status of small-scale agro processors, followed by trademark and inventory, respectively. These internal resources factors will allow for informed and targeted policy response and customised business development support initiatives for small-scale agro-processors.

1. Introduction

Current studies have shown that internal resources play a vital role in ensuring that enterprises tap into external opportunities (Abebe et al., Citation2021; Chinakidzwa & Phiri, Citation2020; Hitt et al., Citation2017; Intarakumnerd, Citation2021). Given the resource-based view (RBV) theory of the firm growth, which tends to present internal resources as the source of comparative advantage that defines its approach to providing services and products (Barney, Citation2001; Essel et al., Citation2019). According to Hegazy (Citation2021) and Kumar (Citation2021), inventory is critical to identify expertise and overcoming fragmentation, and these are overlooked mainly by the small-scale agro-processing enterprises in South Africa. Access to markets in any sector, including the agro-food chain, is mainly driven by the network of the entrepreneur and market actors, agents, and brokers in the agro value chain (Campbell, Citation2021; Kumar, Citation2021; Mburu, Citation2021). Thus, business networking is a socio-economic commercial activity in which groups of like-minded entrepreneurs identify, develop, or take advantage of business possibilities (Muranga, Citation2020). Furthermore, Thindisa and Urban (Citation2018) contend that small-scale agro-processors who collaborated and maintained networks had a competitive edge over competitors who did not. As a result, good trademark usage may play a role in improving branding and longer-term investments in innovation (Lybbert et al., Citation2017).

While, agro-processors are generally considered to be the engine room or the drivers of economic growth and development of the agricultural sector, especially in developing economies (Leser, Citation2013; Thindisa, Citation2014; V. Mmbengwa et al., Citation2018,; Akpan et al., Citation2020), small-scale agro-processors have been under resourced to take advantage of the external opportunities. It is arguably associated with significant contributions to alleviating socio-economic challenges, income, employment, food availability, nutrition, and enhancing small-scale farmers’ sustainability and rural livelihoods (Mhazo et al., Citation2012; Mmbengwa et al., Citation2020).

In brief, the agro-processing industry plays a considerable role in South African society’s socio-economic development. Hence, it is identified by its key development policies such as the Industrial Policy Action Plan (IPAP), the New Growth Path, and the National Development Plan (N.D.P.) (Khoza et al., Citation2019). These policies place small-scale agro-processing as an integral part of South Africa’s development agenda. Their involvement in agro-processing can contribute significantly to the households’ sustainable livelihoods in peri-urban and rural areas of South Africa (Satyasai & Singh, Citation2021; Thindisa, Citation2014; Wilkinson & Rocha, Citation2008, April). Hence, Sharma (Citation2016) highlighted the importance of their participation in the global value chains and emphasized their pivotal role in developing countries’ agricultural development.

It has been reported that small-scale agro-processing industries in sub-Saharan Africa are potential sources of livelihood for a majority poor people living in this region (Daninga, Citation2020). These small and medium agro-processing industries have a functional role in employing workforce at low capital cost, generating higher production volumes, introducing innovation and entrepreneurship skills, increasing exports, and distributing income across the country due to increased profit accrued from increased investment (Chichaybelu et al., Citation2021; Mohamed & Mnguu, Citation2014). However, the contrary can be assumed in South Africa, where agro-processing and agriculture are premised within a dualistic system.

In South Africa, commercial agriculture is the leading player in the agro-processing industry, supplying major retailers and export agencies, whereas small-scale agro-processing plays a limited role in the supply of agro-processed products on the commercial scale. Despite receiving perpetual financial and non-financial support from the government (Mmbengwa et al., Citation2011). Although small-scale agro-processors receive the government’s support, their growth and expansion are not resonating with the corresponding support, leading to policymakers questioning the rationale for supporting these entrepreneurs. The argument that small-scale agro-processors are resource-poor is often used to motivate for their perpetual support. Given the above, the South African government has found it challenging to transform the agro-industries to include small-scale agro-processing entrepreneurs without looking at their complex resource endowments (Mmbengwa et al., Citation2020). The internal resources endowment of small-scale agro-processors is extremely weak, and such have been exposed by the current studies (Yiridomoh et al., Citation2020). Henceforth, this study aims to unpack the network’s impact on the internal resources of the small-scale agro-processors in South Africa to strengthen or guide the networks’ establishment within this sub-sector.

2. Theoretical framework

This paper was premised on the resource-based theory, which defined resources as tangible and intangible assets used by firms to conceive and implement their business strategies (Kozlenkova et al., Citation2014; Saiz-Alvarez, Citation2020). Kostopoulos et al. (Citation2002) and Jurevicius (Citation2013) concur that the resources should either be tangible (financial or physical) or intangible (employee’s knowledge, experiences, skills, firm’s reputation, brand name, and organizational procedures). Given the above observations, the dualistic nature of resources appears to be immaterial when considering that researchers have consensus on the resource question’s conceptualization (Schriber & Löwstedt, Citation2015).

While it is important to conceptualize the nature of the small-scale agro-processors resources, it may be useful to understand that the intangible resources are equally important in making the business grow and be sustainable (Enz, Citation2009). The challenges that small-scale agro-processors may be facing in South Africa have not to be categorized within the conceptualized resource-based theory, making it difficult to diagnose to what extent does the tangible and intangible resources affect their sustainability—considering Van Auken et al. (Citation2008)’s emphasis that firms can gain a competitive advantage through intangible resources that competitors do not possess. It does appear that intangible resources may have a superior influence relative to the tangible resources endowments. However, the combination of the tangible and intangible resources in agri-business and agro-processing has been rarely reported, such that it is difficult to understand the interaction of such resources in the small-scale agro-processing industries. The business network has been reported as one of the critical intangible resources that could induce robust competitiveness (Kura et al., Citation2020; Ujwary-Gil & Potoczek, Citation2020). Does a business network induce competitiveness in the exclusion of other important intangible resource factors?

The South African Presidential Advisory Council (SAPEAC) appears to appraise intangible resources such as networks and mentorship to improve the competitiveness of the small-scale and subsistence black-owned farms in South Africa. However, the actual practice in the agri-business sector of South Africa seems to favor the tangible resource capacitation as observed in the procurement of these entrepreneurs’ capacity building. The concept of resource-poor farmers or agro-processors is misleading as it is based on tangible resources alone. Furthermore, the intangible business capacitation has been difficult to measure especially looking at the aftercare support that the government is providing. This is evident because these businesses have limited commercial networks to source services, market access, and inputs, making their businesses unsustainable and less profitable (Mmbengwa, Citation2009; Rambe & Agbotame, Citation2018).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study area

The study was carried out in the five provinces of South Africa, namely Gauteng, Limpopo, North West, Free State, and Mpumalanga provinces (see ). These provinces are located towards the northern, Eastern and western parts of South Africa. These provinces borders South Africa with Zimbabwe in the north, Mozambique in the east, Botswana in the West and Lesotho in the south. These provinces combined accounts to 55% of South Africa’s population and 64% of the agri-business economy of South Africa (Mthobeni et al., Citation2021; Stats SA., Citation2018). Furthermore, the study area cover 4 of 8 metropolitan areas in South Africa. Lastly, the study area accounts to 60.5% of South Africa’s economy. Finally, the research field accounts for 60.5% of the South African economy. South Africa’s biggest problem is the country’s high levels of inequality, poverty, and unemployment. The present financing available to small-scale agro-processors in South Africa varies by region (DTIC, Citation2021). demonstrated that the Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition did not finance female small-scale agro-processors in various provinces, including Limpopo and Free State. This demonstrates that males continue to outnumber females in terms of financing. This finding contradicts the country’s transformative aims, which prioritize economic empowerment for women.

Figure 1. Map of South Africa showing Provinces. Source: (Google maps, Citation2019)

Table 1. The overview of the black-owned small-scale agro-processors in South Africa

3.2. Data collection and analysis

3.2.1. Sampling and design

An estimated number of small-scale agro-processors in the study area were 1196. The sample selection criterion within the provinces was mainly guided by the high prevalence of small-scale agro-processing activities and the number of entrepreneurs in that sector (Stats SA., Citation2019). The study employed a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design to collect both qualitative and quantitative primary data. The study used a stratified random sampling technique was used to select 500 respondents across all five provinces.

3.2.2. Data collection

The data collection was done in a series where the collection of the quantitative data preceded the qualitative data collection. This was done to ensure that quantitative information forms the core of the study, while qualitative was used to provide the living explanation of the phenomena under investigation. The quantitative data collection was done in 2019 and involved the face-to-face interviews of 503 small-scale agro-processors using the pre-tested closed-ended questionnaire. This was followed by five provincial focus group sessions, which constitute the qualitative data collection, aided by a focus group discussion agenda. While in the focus group session, only the agenda items were used to collect the data from the discussion, the quantitative questionnaire was designed to collect biographic, demographic, and empirical information. The biographic and demographic information includes information such as gender, age of the respondents, enterprise location, enterprise size, educational achievement, employment status, years of experience, agro-processing products. On the other hand, the questionnaire’s empirical information was captured in the last section of the questionnaire. These questions were measured in terms of a seven-point Likert scale, where the scale of one represents “Strongly Disagree,” and the scale of seven represents Strongly Agree.”

3.2.3. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted to get descriptive and empirical information. The analyses were obtained using descriptive analytics, Pearson correlation analysis, and hierarchical multiple linear regression model (HMLR). In the descriptive analysis, the frequencies and percentages were used to analyze the variables under consideration. On the other hand, the Pearson correlation analysis was used to determine the relationship between the study variables, while the empirical effect of the factors that influence the small-scale agro-processors internal resource status was tested using the H.M.L.R. The test commences by examining the network’s significance on the internal resource factors in model 1, then testing both network and inventory in model 2, and end up with the inclusion of trademark variables in Model 3.

3.3. Model specification

H.M.L.R. is a complex form of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression is used to analyze variance in the outcome variables when the predictor variables are at varying hierarchical levels (Ekum & Ogunsanya, Citation2020; Woltman et al., Citation2012). This technique divides the unit of analysis into subsystems that form a hierarchical structure (Perotti et al., Citation2020). We choose this model because it is compatible with solving complex societal phenomena with hierarchical combinations of the factors. The internal resources factors in the small-scale agro-processing, unlike the commercial firms, have a blur cluster of networks, inventory, and trademarks. Model 1 was computed using the following analytical framework.

Where Y1 represents an internal resource, C represents constant, β represents coefficients, X1, represents a network. E1 represented an error term.

The second model’s computation was simply estimated by adding one more independent variable in the original equation. This was illustrated as follows:

Where X2 represents inventory.

Similarly, the last model (Model 3) was calculated by adding the variable trademarks to independent variables from model 2, resulting in the following equation:

Where X3 represents trademarks.

The last model represents the ideal model that could be used to determine the factors that influence the small-scale agro-processors internal resource status. This complete model includes all variables that were selectively computed in various preceding models.

3.4. Validity and reliability of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Models

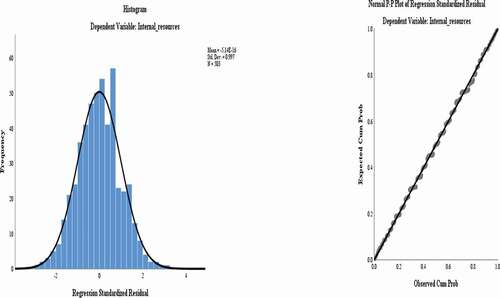

The validity and reliability of the models mentioned above were tested using their condition for use. Before interpreting the model results, several assumptions were tested and checked if appropriate to conduct these models. The normality test was the first test conducted, and the results of the test were presented in and . According to the results in , it was found that all the variables were normally distributed.

Figure 2. Illustration of the normality of the status of the internal resource

shows the test of homoscedasticity of the internal resource for small-scale agro-processing, and it revealed that the variable is free from homoscedasticity. Then, the multicollinearity test was conducted using Pearson correlation analysis (see ), which turns out that there is no threat of multicollinearity (i.e., there are no variables that correlate equivalently to r = 0.85).

These results were also confirmed by tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values (see ). The tolerance values in the models were greater than 0.1, and VIF values were all lesser than 10 to signify no multicollinearity concerns. The correlation between internal resources and inventory was found to be small [r (501) = 0.170, p = 0.000], while the correlations between internal resources and trademarks [r (501) = 0.302, p = 0.000], internal resources and networks: [r (501) = 0.500, p = 0.000] and trademarks and networks [r (501), 0.338, p = 0.000], were all found to be moderate.

Table 2. The respondents’ socio-economic status

Table 3. Effect of the factors that influence the internal resource status of the small-scale agro-processors

outlines the results of the test of the multivariate outliers using residual statistics. The measure of the multivariate outliers is Mahalanobis distance. If the Mahalanobis distance exceeds the critical Chi-squared value, then there are multivariate outliers. In this case, the Chi-squared value for the degree of freedom (alpha = 0.001 is 16.266), and the maximum value of the Mahalanobis distance is 13.010. These results suggest that there are no multivariate outliers’ concerns.

Given all the tests for the conditions for the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Models in this study, it is evident that the models used are valid and reliable for this study.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. The socio-economic status of the small-scale agro-processors

presents the socio-economic status of the small-scale agro-processors. The majority (77.8% and 82.6% are female and male, respectively) of the small-scale agro-processors. According to the results the males are dominant in the small-scale agro-processing industry of South Africa, which is contrary to other studies (Owoo & Lambon-Quayefio, Citation2017; Mangubhai & Lawless, Citation2021; Paganini & Stöber, Citation2021; Mthobeni et al., Citation2021; Ampadu-). The dominance of the male might be a result of the unique situation of South Africa where black women were not allowed to participate in the economy during the apartheid period. This was also ventilated during the focus group discussion session. In these sessions, some of the participants strongly felt that government intervention has been very biased to male-owned enterprises. A study conducted in Nigeria confirms the findings of the current study in that 92.73% small-scale agro processors in the study were found to be male (Akpan et al., Citation2020). Another Study conducted on South Africa’s small-scale agro-processing businesses confirms that findings of the current study in the 60% of respondents were male and 70% on Zimbabwe (Gumbochuma, Citation2017). Furthermore, the results divulged that 8.8% of female agro-processor were pensioners relative to 2.2% of the males. In the study conducted by Mthobeni et al. (Citation2021) and Gumbochuma (Citation2017), it was found that 80.8% of the small-scale agro-processors were between ages of 31 and 60 years old, which is below the pensionable age of 65 as per South African benchmark. Another study conducted by Akpan et al. (Citation2020) it was found that over 80% of small-scale agro-processors in Nigeria were below 50 years. The employed males were slightly higher in the numbers (8.7%) than in the female counterparts (7.4%).

presents the socio-economic status of the small-scale agro-processors. Most respondents were females (72.6%), small-scale agro-processors, and males (27.4%). According to the results, females dominate the small-scale agro-processing industry of South Africa, which agrees with other studies (Ampadu-Ameyaw & Omari, Citation2015; Mangubhai & Lawless, Citation2021; Mthobeni et al., Citation2021; Owoo & Lambon-Quayefio, Citation2017; Paganini & Stöber, Citation2021). The dominance of the females might result from the unique situation of South Africa, where black women were not allowed to participate in the formal economy during the apartheid period. This was also ventilated during the focus group discussion sessions. In these sessions, some participants strongly felt that government intervention has been very biased toward male-owned enterprises. A study conducted in Nigeria contradicts the current study’s findings that 92.73% of small-scale agro-processors in the study were male (Akpan et al., Citation2020). Another study conducted on South Africa’s small-scale agro-processing businesses contradicts that finding of the current study in that 60% of respondents was male and 70% in Zimbabwe (Gumbochuma, Citation2017). Furthermore, the results divulged that 8.8% of female agro-processor were pensioners relative to 2.2% of the males. In the study conducted by Mthobeni et al. (Citation2021) and Gumbochuma (Citation2017), it was found that 80.8% of the small-scale agro-processors were between the ages of 31 and 60 years old, which is below the pensionable age of 65 as per South African benchmark. In another study conducted by Akpan et al. (Citation2020), over 80% of small-scale agro-processors in Nigeria were below 50 years. The employed males were slightly higher in the numbers (8.7%) than their female counterparts (7.4%).

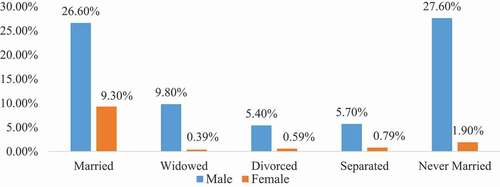

The participation of these entrepreneurs in this sector is further explained in . In this results, it can be seen that married (26.6%) and unmarried (27.6%) men are participating in the sector far more than females. An analysis of the participation of female entrepreneurs’ shows that that majority are married (9.3%) followed by unmarried (1.9%), and lowest (0.39%) were widowed women. It appears that the married women are participating in this sector due to their husbands’ networks or resources to establish and operate their businesses. These observations show that married women and those who were never married form a significant part of the small-scale agro-processors. The higher participation by unmarried males might imply that more young males are participating in the sector owing to the successful implementation of the country’s youth development programmes. Akpan et al. (Citation2020) appears to confirm that the majority of the participants in the sector are from married entrepreneurs. Although this study seems to have some difference when it comes to those that are unmarried. On the overall, it may be reasonable to assume that resources availability through marriage has a positive influence in the participation of both male and female entrepreneurs in this sector.

4.2. The effect of the factors that influence the internal resource status of the small-scale agro-processors

presents the effects of the factors that influence the internal resource status of the small-scale agro-processors. When testing or analyzing the effects of the networks on the internal resource status of small-scale agro-processors, it found that network (β = 0.440, p = 0.000) has positive and significant influence on the internal resources of the enterprises. Subsequently, the test included both network and inventory, it was found that network (β = 0.491, p = 0.000) continues to have positive and significant influence as compared to inventory (β = 136, p = 0.000), which was also found to positive and significant on the internal resource status of the small-scale agro-processors. The results reveals that the inclusion of the inventory in test has slightly reduced the influence of network on the internal resource status of small-scale agro-processors. But network continue to play a significant and positive role. When considering the network, inventory and trademarks, the influence for all the variables on the internal resource status of small-scale agro-processors was found to be positive and significant (Network (β = 0,440, p = 0.000), inventory (β = 0,138, p = 0.000) and trademark (β = 0,142, p = 0.000)). However, the influence of the network on the internal resources of small-scale agro-processors was found higher than the influence of other two variables (trademark and inventory), individually or combined. The trademark was found to have the second highest influence on the internal resources while the inventory was found to have the least influence. Most importantly, the influence of network on the internal resources continued to decline are more variables are included in the analysis.

Studies by Mukherjee (Citation2018), Premaratne (Citation2002), Thindisa and Urban (Citation2018), and Skryl and Gregorić (Citation2021) are consistent with the findings in that they observed that the creation of networks of domestic suppliers, as well as access to the availability of funding, as well as greater interconnections between S.M.E.s and major enterprises, are crucial. Okten and Osili (Citation2004) found that network formation helps entrepreneurs tap resources in the external environment successfully.

However a study by Fernandes and Da Silva (Citation2016) contradicts the findings in that it reported a lower proportion (17%) impact of the network on the small-scale agro-processors but they agree that these factors are essential for this industry’s sustainability. Other researchers (Grando et al., Citation2020; Neves, Citation2020; Santacoloma et al., Citation2009) contended that networks form the cornerstone of the internal resources of these enterprises. The findings are further consistent with that the resource-based theoretical framework, whose central tenet is internal resources (Nagano, Citation2020). The study’s findings on networks concur with studies by Setsoafia et al. (Citation2015), Ökten et al. (Citation2004), and P. Shane and Hoverd (Citation2002). Networking is essential to small-scale agro-processors and can positively impact their performance and finance access (Setsoafia et al., Citation2015). Researchers have identified networking as one of the fastest ways for the owner-manager to understand his environment, which is crucial for business growth and competitiveness. Okten and Osili (Citation2004) found that network formation helps entrepreneurs tap resources in the external environment successfully. According to S. Shane and Cable (Citation2002), networking can reduce information asymmetry in creditor or debtor relationships.

Gaikwad et al. (Citation2019) and Kareem et al. (Citation2020)’s findings on the influence of inventory on the internal resources of small-scale agro-processors is consistent with the findings of the current study, which found that inventory plays an important role in small-scale agro-processors. The studies confirm that inventory findings significantly impact the internal resource status of small-scale agro-processors in South Africa.

On the trademark, the study is consistent with the findings Range (Citation2020), which indicates that trademark protection systems will help the micro enteprises to enjoy their right to the fruits of their efforts and that the state has to respect and protect that natural right. Various studies such as Hao (Citation2021), Udova (Citation2020), Omillo, & Okubo. (Citation2018) found that trademark is significant to enhance the status of the internal resource of small-scale agro-processors. Contrary to other findings and findings of the current study, Range (Citation2020) found that over 63% of the S.M.M.E. in the agro-processing sector in Tanzania did not utilize trademarks. In overall, it found that a network a significant influence on the internal resources of small-scale agro-processors.

There are no studies which used hierarchical multiple regression model to analyze the impact of network, inventory and trademark. All other studies analysed the influence of these variables on the internal resources of small-scale agro-processors separately. Therefore, it appears that the current study presents a unique South African experience.

During the focus group sessions there contrary views on the ranking of network, inventory and trademark’s influence on the internal resources status of the small-scale agro-processors. Even though there were disagreements, however it was uncontested that network has significant influence on the internal resource status of small-scale agro-processors as compared to trademark and inventory. Most of the respondents who were supporting trademark and inventory as the significant influencers of internal resources were mainly man because they might have been already involved in some form of networking due to the historical situation of South Africa where females were marginalized. But in the main it was unconstented that network is main variable that could influence the internal resources status of small-scale agro-processors.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The study aimed to assess the networks’ implications on small-scale agricultural processors’ internal resources in South Africa. The investigation demonstrated that the network, inventories, and trademarks determined the small-scale agro-processors internal resource status. However, compared to both factors together, the network had the most significant influence. In conclusion, married female agro-processors have been highly resourced because of their networks with their husbands. In addition, because of their access to the government’s youth development programs or policies, young males were well resourced. Thus, the policies of young people should be re-examined because they are also required to benefit the women who are single, widowed, and separated. If the problem is not addressed, the transformation benefits might be reversed, which seems to be gaining momentum. There can, however, be an invalidation if widows, unmarried and separated women are not deemed to benefit from these programs as they face significant levels of poverty and are affected by their dependent condition.

The practical implications of the findings are that if the government is not addressing a significant gap in empowering young girls, the country’s transformative program will be reversed. The report advises that empowerment or transformation attention should be given to girls’ empowerment by understanding the relevance of agro-processing on food security. The survey demonstrates decreased interest in male agro-processors, and there is a need to involve them in awareness campaigns. It is recommended that the small-scale agro-processors should establish lobby organizations at local, regional, provincial, and national levels to enhance their networking capacity.

Declaration on interest statement

This study is part of the PhD studies, and the manuscript has extracted the thesis that is undergoing examination.

Disclaimer

This article is an extract from a PhD thesis submitted at the North West University Business School, South Africa.

Ethics

Ethical clearance was issued by North-West University’s Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Committee (EMS RSC) before the data collection process’s commenced (NWU-00611-20-A4)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the North-West University and City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality for supporting this project and the National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC) for assistance in providing the supervision.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

B Manasoe

Mr. Benjamin Manasoe graduated with a Master of Commerce in Economics and a Master of Philosophy in Information and Knowledge Management from the University of Johannesburg and Stellenbosch University. He is a PhD candidate at the North West University’s Business School. His primary research interests include agro-processing, tourism, small-scale or enterprise development, marketing, and agricultural education.

Prof. Victor M. Mmbengwa holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from the University of the Free State (UFS), South Africa. He is currently holding a position as a manager at the National Agricultural Marketing Council and an associate extraordinaire professor at North-West University (NWU).

Dr. Joseph N. Lekunze is a Research Manager at the North-West University’s Business School. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics at the Northwest University.

References

- Abebe, G. K., & Gebremariam, T. A. (2021). Challenges for entrepreneurship development in rural economies: The case of micro and small-scale enterprises in Ethiopia. Small Enterprise Research, 28(1), 36–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2021.1878385

- Akpan, S. B., Offor, O. S., & Archibong, O. E. (2020). Access and demand for credit among small-scale agro-based processors in Uyo agricultural zone, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Nigeria Agricultural Journal, 51(1), 132–141. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/naj

- Ampadu-Ameyaw, R., & Omari, R. (2015). Small-Scale rural agro-processing enterprises in Ghana: Status, challenges and livelihood opportunities of women. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 6(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.9734/JSRR/2015/15523

- Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4011938

- Campbell, A. D. (2021). Designing development: an exploration of technology innovation by small-scale urban farmers in Johannesburg ( Doctoral dissertation, Politecnico di Milano).

- Chichaybelu, M., Girma, N., Fikre, A., Gemechu, B., Mekuriaw, T., Geleta, T., & Ojiewo, C. O. (2021). Enhancing chickpea production and productivity through ‘stakeholders’ innovation platform approach in Ethiopia. In: E, Akpo; C.O. Ojiewo; I., Kopran; L.O., Omoigui; A. Diama, & R.K., Varshney, (eds) Enhancing smallholder farmers’ access to seed of improved legume varieties through multi-stakeholder platforms: Learning from the TLII project experiences in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Singapore: Springer

- Chinakidzwa, M., & Phiri, M. (2020). Exploring digital marketing resources, capabilities and market performance of small to medium agro-processors. A conceptual model. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 14(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.24052/JBRMR/V14IS02/ART-01

- Daninga, P. D. (2020). Capitalizing on agro-processing in Tanzania through Sino Africa co-operation. Journal of Co-operative and Business Studies (J.C.B.S.), 5(1), 60–72.

- Ekum, M., & Ogunsanya, A. (2020). Application of hierarchical polynomial regression models to predict transmission of COVID-19 at the global level. International Journal of Clinical Biostatistics and Biometrics, 6(1), 027. https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5831/1510027

- Enz, C. A. (2009). Human resource management: A troubling issue for the global hotel industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 50(4), 578–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965509349030

- Essel, B. K. C., Adams, F., & Amankwah, K. (2019). Effect of entrepreneur, firm, and institutional characteristics on small-scale firm performance in Ghana. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0178-y

- Fernandes, A. R., & Da Silva, C. A. B. (2016). Ten Years Later: a Comparison between the Results of Early Simulation Scenarios and the Sustainability of a Small‐Scale Agro‐Industry Development Program. Int. J. Food Systems Dynamics, 8 (2), pp. 106–129. http://doi.org/10.18461/ijfsd.v8i2.823

- Gaikward, G.P., Sawate, A.R., Kshirsagar, R.B., Veer, S.J. and Mane, R.B. (2019). Studies on the development and organoleptic evaluation of sweetener-based carrot preserve. The Pharma Innovation Journal, 8(3), pp. 340-343. https://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2019/vol8issue3/PartF/8-2-148-485.pdf

- Google maps. (2019). Map of the Republic of South Africa. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https://www.google.com/search?q=Map+of+south+africa&rlz=1C1GCEU_enZA822ZA822&oq=Map+of+south+africa&aqs=chrome.69i57.13553j0j15&sourceid=chrome¡UTF-8

- Grando, S., Bartolini, F., Bonjean, I., Brunori, G., Mathijs, E., Prosperi, P., & Vergamini, D. (2020). Small farms’ behaviour: Conditions, strategies, and performances. In: G., Brunori & S., Grando. (eds) Innovation for sustainability. United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing Limited

- Gumbochuma, J. (2017). The status and impact of technology transfer and innovation on the productivity and competitiveness of small-scale agro-processing businesses in Mashonaland Central (Zimbabwe) and Free State (South Africa). Free State: Central University of Technology. Phd

- Hao, W., Rasul, F., Bhatti, Z., Hassan, M.S., Ahmed, I. & Asghar., N. 2021. A technological innovation and economic progress enhancement: An assessment of sustainable economic and environmental management. Environment Science and Pollution Research, 28(22). 28585–28597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-12559–9

- Hegazy, R. (2021). Interdisciplinary tools to advance agro-food processing research and projects implementation in Egypt. ScienceOpen Preprints. https://doi.org/10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-.PPSNJVP.v1

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, D. R., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2017). Strategic Management. Competitiveness and Globalisation. Concepts and Cases. 12 edition ed. Cengage Learning.

- Intarakumnerd, P. (2021). Technological learning and innovations of manufacturing firms in selected ASEAN countries: An implication for future collaboration with Taiwan. In G, San & P, Intarakumnerd (eds). Industrial development of Taiwan: Past achievements and future challenges beyond 2020. New York: Routledge

- Jurevicius, O. (2013). Resource-based view. Strategic Management Insight. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from http://strategicmanagementinsight.com/topics/resource-based-view. HTML.

- Kareem, A.O., Jijobe, T.F., Adejumo, O.O, & Akininyosoye, M.O. 2020. Socio-cultural factors and performance of the small-scale enterprise in agro-allied manufacturing firms in Nigeria. In: E.S., Osabuohien. (ed.) The Palgrave handbook of agricultural and rural development in Africa. London: Palgrave McMillan

- Khoza, T. M., Senyolo, G. M., Mmbengwa, V. M., Soundy, P., Sinnett, D., & Sinnett, D.. (2019). Socio-economic factors influencing smallholder farmers’ decision to participate in the agro-processing industry in Gauteng province, South Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1664193. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1664193

- Kostopoulos, K. C., Spanos, Y. E., & Prastacos, G. P. (2002, May). The resource-based view of the firm and innovation: Identification of critical linkages. In The 2nd European Academy of Management Conference (pp. 1–19). Stockholm, Sweden: EURAM.

- Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-013-0336-7

- Kumar, S. (2021). Investment pattern and sources of finance in micro, small and medium agro-processing enterprises in India. In: S., Bathla & E., Kannan. (eds) Agro and food processing industry in India. Singapore: Springer

- Kura, K. M., Abubakar, R. A., & Salleh, N. M. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation, total quality management, competitive intensity, and performance of S.M.E.s: A resource-based approach. Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques, 8(1), 61–72. http://www.jett.dormaj.com/docs/volume/issue@201/entrepreneurial%20Orientation,%20Total%20Quality20%Managment%20Competitive%20Intensity,%20and%20Peroformance%20%SMMEs%20-%20A%20Resources-based%20approach.pdf

- Leser, S. (2013). The 2013 F.A.O. report on dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition: Recommendations and implications. Nutrition Bulletin, 38(4), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/nbu.12063

- Lybbert, T., Saxena, K., Ecura, J. Kawooya, D. & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (2017). Enhancing innovation in the Uganda Agri-Food Sector: Progress, constraints, and possibilities. In: S., Dutta; B., Lanvin & S., Wunsch-Vincent. (eds). The global innovation index 2017. United States of America: Cornell University

- Mangubhai, S., & Lawless, S. (2021). Exploring gender inclusion in small-scale fisheries management and development in Melanesia. Marine Policy, 123, 104287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104287

- Mburu, P. (2021). Resolving the disconnect between market actors, agents and brokers and small-holder fresh produce farmers in Agribusiness. E3 Journal of Business Management and Economics, 11(1), 001–009. http://dx.doi.org/10.18685/EJBME(11)1_EJBME-21-011

- Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition. (2021). Agro-processing incentive scheme report. South Africa: Pretoria. http://www.dtic.gov.za/financial-and-non-financial/incentives/agro-processing-support-scheme

- Mhazo, N., Mvumi, B. M., Nyakudya, E., & Nazare, R. M. (2012). The status of the agro-processing industry in Zimbabwe with particular reference to small-and medium-scale enterprises. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(11), 1607–1622. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR10.079

- Mmbengwa, V., Khoza, T. M., Rambau, K., & Rakuambo, J. (2018). Assessment of the participation of smallholder farmers in agro-processing industries of Gauteng Province. O.I.D.A. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(2), 11–18. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3149148

- Mmbengwa, V. M. (2009). Capacity-building strategies for sustainable farming S.M.M.E.s in South Africa. Ph.D. (Agricultural Economics) Dissertation, University of the free state.

- Mmbengwa, V. M., Rambau, K., & Qin, X. (2020). Key factors for the improvement of smallholder farmers’ participation in agro-processing industries of Gauteng province of the Republic of South Africa: Lessons for the extension advisory services. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 48(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2020/v48n2a545

- Mmbengwa, V. M., Ramukumba, T., Groenewald, J. A., Van Schalkwyk, H. D., Gundidza, M. B., & Maiwashe, A. N. (2011). Evaluation of essential capacities required for the performance of farming small, micro, and medium enterprises (S.M.M.E.s) in South Africa. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 6(6), 1500–1507. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR10.843

- Mohamed, Y., & Mnguu, Y. O. (2014). Fiscal and monetary policies: Challenges for small and medium enterprises (S.M.E.s) development in Tanzania. International Journal of Social Sciences and Entrepreneurship, 1(10), 305–320.

- Mthobeni, D. L., Antwi, M. A., & Rubhara, T. (2021). Level of participation of small-scale crop farmers in agro-processing in Gauteng Province of South Africa. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.96.19455

- Mukherjee, S. (2018). Challenges to Indian micro small scale and medium enterprises in the era of globalization. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0115-5

- Muranga, B.K. (2020). Determinants of competitiveness of small and medium agro-processing firms in Kenya. Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. Thesis: PhD

- Nagano, H. (2020). The growth of the knowledge through the resource-based view. Management Decision, 58(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2016-0798

- Neves, J. C. (2020). Upper bound on the GUP parameter using the black hole shadow. The European Physical Journal C, 80(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-7913-y

- Okten, C., & Osili, U. O. (2004). Social networks and credit access in Indonesia. World Development, 32(7), 1225–1246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.01.012

- Ökten, Z., Churchman, L. S., Rock, R. S., & Spudich, J. A. (2004). Myosin VI walks hand-over-hand along actin. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 11(9), 884–887. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb815

- Omillio, S.F.O. & Okobu, L.M.Y. 2018. Does intellectual property protection bring advantages to innovators and consumers? Perception of Kenyan small agro-food processors. ILIRIA International Review,8(1). 39–56. www.dx.doi.org/10.2113/iir.v8i1.384

- Owoo, N. S., & Lambon-Quayefio, M. P. (2017). The agro-processing industry and its potential for structural transformation of the Ghanaian economy. In: S.N., Richard; J., Page; F., Tarp. (eds) Industries with smokestacks: industrialization in Africa recognized. Finland: United Nations University World Institute.(No. 2017/9). WIDER Working Paper.

- Paganini, N., & Stöber, S. (2021). From the researched to co-researchers: Including excluded participants in community-led research on urban agriculture in Cape Town. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 4(26), p.p. 1–20. https://doi.og/10/1080/1389224x.202.1873157

- Perotti, J. I., Almeira, N., & Saracco, F. (2020). Towards a generalization of information theory for hierarchical partitions. Physical Review, 101(6), 1–11. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.101.062148

- Premaratne, S. P. (2002). Entrepreneurial networks and small business development. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

- Rambe, P., & Agbotame, L. A. (2018). Influence of foreign alliances on small-scale agricultural businesses’ performance in South Africa: A new institutional economics perspective. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.2011

- Range, M.R. (2020). Utilization of trademarks in promoting formal micro-enterprises and food industries in Tanzania. Africa University. (Thesis - MA).

- Saiz-Alvarez, J. M. (2020). Circular economy: An emerging paradigm–concept, principles, and characteristics. In: N, Baporikar. (ed) Handbook of research on entrepreneurship development and opportunities in the circular economy. United States: I.G.I. Global

- Santacoloma, P., Röttger, A., & Tartanac, F. (2009). Business management for small-scale agro-industries. F.A.O. Agriculture Management, Marketing and Finance Service Rural Infrastructure, Agro-Industries Division, Food, and agriculture organization of the United Nations.

- Satyasai, K. J. S., & Singh, A. (2021). The food processing industry in India: regional spread, linkages, and space for farmer producer organizations. In: S Bathlai & E, Kannan. (Eds) Agro and food processing industry in India (pp. 81–106). Singapore: Springer

- Schriber, S., & Löwstedt, J. (2015). Tangible resources and the development of organizational capabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2014.05.003

- Setsoafia, D. D. Y., Hing, P., Jung, S. C., Azad, A. K., & Lim, C. M. (2015). Sol-gel synthesis and characterization of Zn2+ and Mg2+ doped La10Si6O27 electrolytes for solid oxide fuel cells. Solid-State Sciences, 48(3), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2015.08.001

- Shane, P., & Hoverd, J. (2002). Distal record of multi-sourced tephra in Onepoto Basin, Auckland, New Zealand: Implications for volcanic chronology, frequency, and hazards. Bulletin of Volcanology, 64(7), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-002-0217-2

- Shane, S., & Cable, D. (2002). Network ties, reputation, and the financing of new ventures. Management Science, 48(3), 364–381. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.3.364.7731

- Sharma, M. (2016). Theoretical foundations of health education and health promotion. Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

- Skryl, T., & Gregorić, M. (2021). The impact of the fourth industrial revolution on network business models. In Konica, N (ed). Digital strategies in a global market: Navigating the fourth industrial revolution. London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Stats SA. (2018). Stats online. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https://www.Stats-SA.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022019.pdf

- Stats SA. (2019). Mid-year population estimates: 2019. (Statistical release P0302). Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https://www.Stats-SA.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022019.pdf

- Thindisa, L., & Urban, B. (2018). Human-social capital and market access factors influencing agro-processing participation by small-scale agripreneurs: The moderating effects of transaction costs. Acta Commercii, 18(1), 1–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v18i1.500

- Thindisa, L. M. V. (2014). Participation by smallholder farming entrepreneurs in agro-processing activities in South Africa. Masters dissertation. Wits University.

- Udova, L. 2020. Agro-franchising as a prospect for small agro-businesses development in Ukraine. The Scientific Journal of Cahul State University “Bogdan Petriceicu Hasden” Economic and Engineering Studies, 7(1). 105–109

- Ujwary-Gil, A., & Potoczek, N. R. (2020). A dynamic, network, and resource-based approach to the sustainable business model. Electronic Markets, 30(4), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-020-00431-6

- Van Auken, H., Madrid-Guijarro, A., & Garcia-Perez-de-Lema, D. (2008). Innovation and performance in Spanish manufacturing S.M.E.s. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 8(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2008.018611

- Wilkinson, J., & Rocha, R. (2008, April 8-11). The agro-processing sector: Empirical overview, recent trends and development impacts. Plenary paper presented at the Global Industries Forum, New Dehli, India

- Woltman, H., Feldstain, A., MacKay, J. C., & Rocchi, M. (2012). An introduction to hierarchical linear modeling. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p052

- Yiridomoh, G. Y., Appiah, D. O., Owusu, V., & Bonye, S. Z. (2020). Women smallholder farmers off-farm adaptation strategies to climate variability in rural Savannah, Ghana. GeoJournal, 1-19. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-1019/7

Appendix

Table A1. The test for normality using Skewness and Kurtosis

Table A2. The Pearson correlation of the internal resources factors

Table A3. Test for multivariate outliers using residual statistics (N = 503)