Abstract

Zimbabwe is currently suffering from a myriad of environmental conservation problems in addition to destabilising economic and political problems. As a result of the growing crisis of environmental degradation, the government has developed divergent policies, acts and resolutions to address the problems. While scholars have emphasised the significance of environmental legislation, the continual environmental degradation in the country questions the resource management strategies currently in use. This paper seeks to examine the symbiotic relationship between society, politics and the environment in Chivi District, Southern Zimbabwe. The paper uses political ecology lens to interrogate the policies and regulations whose implementation is often caught up in a web of political interactions as diverse stakeholders seek to maximise the use of natural resources with negative repercussions on the environment. The paper addresses these aspects by adopting a qualitative approach while using Chivi District as a case study. Data were gathered through desktop review and in-depth interviews with 15 purposively sampled key informants and 30 conveniently sampled community members. Data collected were analysed using the thematic analysis method. The findings demonstrate that some regulatory frameworks on environment did not only protect sustainable use of natural resources but they also engender degradation of the same resources. Results of the study show that the existing environmental regulations are fragmented and difficult to enforce and there are some provisions that sanction people to degrade the environment. Unless addressed through deliberate policy intervention, natural resources in Chivi district will severely deteriorate and thus affecting development of the community.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Given the role that natural resources play in the development of rural communities, there is an urgent need for a better understanding of the reasons why communities abuse the same resources that sustains their livelihoods. Using political ecology lens, this paper assesses how frequent political interventions through government laws, policies and institutions in natural resource access and use impact the Chivi district communities, which rely on natural resources for their livelihoods. The choice is based on the fact that Chivi District is an area already overstretched in terms of natural resources, especially land and forest resources that are continuously depleting as a result of indiscriminate exploitation by local communities. Results of the study show that the existing environmental regulations are fragmented and difficult to enforce and there are some provisions that sanction people to degrade the environment. The study, thus, concludes that resource use and power dynamics in everyday interactions go beyond the local community.

1. Introduction

As Zimbabwe continues to suffer from environmental conservation problems (Mawere, Citation2013), academics and policy makers turn to the juridical framework with which the country regulates access to and control over natural resources. The pieces of legislation under this framework, however, are devised to control and not to stop the use of environmental resources. In fact, it is impossible to exclude individuals from using the resources, either through physical barriers or legal instruments. A good environmental policy, therefore, should be concerned with how best to govern the relationship between humans and the natural environment for their mutual benefit (Benson & Jordan, Citation2015). While scholars have stressed the significance of environmental legislation in the country (Dzingirai, Citation2003; De Gobbi, Citation2020), they have largely ignored the implication of the said policies on sustainable management of resources. Yet, the continual environmental degradation in the country questions the resource management strategies currently in use. Using the political ecology approach, this article analyses the relationship between government environmental frameworks and degradation in Chivi district, Southern Zimbabwe. It draws on Batterbury’s idea that conceptualises ‘political ecology” as an approach that addresses political and economic agendas that have real effects on resources, environments, and people (Batterbury, Citation2018). This article therefore concerns itself with how frequent political interventions through government laws, policies and institutions in natural resource access and use impact the Chivi district communities, which rely on natural resources for their livelihoods. The environmental policy perspective in question emerged in the 1970s as a response to human-environment relations that have affected natural resource base. As Benson and Jordan (Citation2015) note, “as policy areas go, environmental policy is relatively youthful, dating back only as far as the early 1970s.” However, they acknowledge that there were environmental provisions that existed before the 1970s but these were relatively fragmented, aimed mainly at securing human health, and developed in a reactive and ad hoc manner. Most researchers and countries focused on how environmental problems are a result of human activities (Hove et al., Citation2020; Macheka et al., Citation2020; Maurya et al., Citation2020). The recognition that the increased pace, scale, and magnitude of contemporary human activity has pervasively affected the natural environment has been an important driver of environmental policy since the 1960s (Benson & Jordan, Citation2015). Gradually environmental policies were introduced.

From the 1970s, environmental regimes visibly gained popularity. It is during the same years that political ecology paradigm emerged as a response to the neglect of the political dimensions in the human–environment relationship. Early environmental regimes were often regionally based, such as UNEP’s 1976 Barcelona Convention for protecting the Mediterranean (Connelly et al., Citation2012). Governments all over the world established agencies and laws to deal with specific environmental issues as and when they arose. Scholars argue that during this period environmental problems were viewed as basically technical in nature thus policies were reactive rather than proactive, and sectorial rather than integrated (Benson & Jordan, Citation2015).

From the 1990s, scholars started framing environmental problems more explicitly as a manifestation of broader political and economic forces. Subsequently, a new phase of international policy making emerged from agreements made at international or regional level. These are the United Nations Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and a Framework Convention on Climate Change, which was subsequently supported by the Kyoto Protocol (1997) aimed at limiting global climate emissions.

In contrast with the history of environmental policy in the Western world, environmental policies in Southern African countries were not created in response to local public pressure but were largely initiated by governments in response to international pressure regarding global environmental issues (Tarr, Citation2003). Resultantly, environmental issues and policies were not taken seriously in Southern Africa largely because of the history of environmental policy during the colonial era. The status of environmental resource degradation in Southern Africa is, in part, a result of strong historical influence. It is because of this that most researches demonstrate that policy implementation has challenges in Southern Africa (Dovers et al., Citation2002; Rossouw & Wiseman, Citation2004).

For instance, South Africa has a cruel history of environmental policy under apartheid wherein the protection of fauna and flora received greater importance than the well-being of the majority of the country’s citizens (Rossouw & Wiseman, Citation2004). As a result, most Black South Africans paid little attention to environmental policy issues, as they were seen as tools for racially based oppression (Dovers et al., Citation2002). Research on South Africa by Rossouw and Wiseman (Citation2004) demonstrates that whilst environmental policy and legislation embody sound democratic principles, implementation, compliance and enforcement strategies are lagging.

The works here demonstrate that there are many drivers to environmental change in the world. In the case of Southern Africa, while policy frameworks are in place to conserve the environmental resource base, the region continues to suffer from severe environmental problems that range from deforestation, soil erosion, and desertification to wetland degradation (Mabogunje, Citation1995). A mere focus on the gaps in policy implementation and practice, this article argues, is a less useful intervention without questioning the existence of the policies and regulations whose implementation is often caught up in a web of political interactions as diverse stakeholders seek to maximise the use of natural resources with negative repercussions on the environment. The objectives of the study were to understand how government environmental frameworks impact on environmental management in Chivi district, Southern Zimbabwe and impact of political interventions on natural resource access and use in Chivi district communities. In the subsequent section, I discuss the theory to be used and how it is going to be applied in the context of this study. Furthermore, it makes an appraisal of how other scholars have applied political ecology to flesh out these environmental management complexities.

2. Theoretical framework

Debates on political ecology denote social and political situations surrounding the genesis, experiences and management of environmental problems. The decision to conserve natural resources is political because natural resource use as well as policy, and management of such resources are intrinsically political (Adams & Hutton, Citation2007). As a lens of analysis, political ecology framework is thus regarded as a useful tool for examining how regulations, policies and interventions impact the poor communities whose livelihoods mostly depend on the environment. Again, the approach is also useful in analysing external influences on local environments. As Bryant (Citation2015) argues political ecology has been important in explaining such phenomena, and particularly the social and political inequities both causing them and mediating their impacts. The environmental threats include the real and existential, particularly from anthropogenic climate change, and a widespread failure by key actors (such as states and large corporations) to recognize environmental and social justice as more important than short-term profits and votes (Batterbury, Citation2015). Political ecology is, therefore, an effort to firmly incorporate a political economic perspective into the study of environmental problems. This article focuses on the political drivers of resource exploitation, how they compete and sometimes collaborate for the use and benefit from the natural resources.

Political ecology becomes more relevant in such an undertaking, not least because as a scientific inter-discipline, it tries to adopt a critical approach to a socio-ecological issue, and social processes for explanations and levers of change: economic exploitation, institutional functioning, power relations, and ideological constraints (Kull & Rangan, Citation2016). Under this approach, environmental degradation is no longer regarded as an ecological problem requiring scientific solutions, but rather an economic and political problem that needs to be explored and addressed. The approach does not suggest that environmental problems do not exist, nor does it point to the weaknesses of ecological science as a lens of analysis. Instead, it emphasises that environmental policy will be more useful if it acknowledges how science and politics are connected (Forsyth, Citation2015). With such a framework, the local environments in Zimbabwe should be understood as entrenched within a wider political economy of environmental degradation. This means that there are rational underpinnings to environmental struggles that create winners and losers (Bixler et al., Citation2015; Hornborg, Citation2017).

More so, political ecology has widely been discussed globally and used even in most recent analyses of interactions between humans and the environment. Using a political ecology approach, scholars have managed to document and analyse specific case studies, globally and locally. Kraft (Citation2018) studied environmental policy and politics in United States of America. He points out that political obstacles and policy disappointments have affected sustainable management of natural resources. In particular, the George W. Bush of the 2000s administration was largely blamed by environmentalist for its reluctance to tackle global climate change, for its misuse or disregard of science, and for environmental protection and natural resource policies that strongly favored economic development over public health and resource conservation (Kraft, Citation2018). Policies mentioned include Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act, which were in use for almost five decades and were unchanged since their initial approval despite questions about their effectiveness, efficiency, and equity that date back to the late 1970s. This evidences that even at global level, environmental challenges are a result of power struggles.

Similar studies on political ecology were done in India. Josh (Citation2015) focused on the North–South binary as a valid frame of reference for inquiry within political ecology. Her argument was made in relation to contemporary international climate politics where constructed national identities—“developing” versus “emerging”—have important material consequences regarding whether a country must assume the financial burden of mitigation. Negotiations over burden-sharing, Josh (Citation2015) argues, are tantamount to a struggle over access to the atmospheric commons. She examines India’s participation in global climate negotiations and argues that political ecology must accommodate an appreciation of such participation, even as Northern political ecologists need to reflect on their own positionality and power in rejecting binary thinking.

Also, as a result of increasing degradation, scholars in Africa began questioning policy practise. Oyebode (Citation2018) for instance, analysed the impact of environmental governance in Nigeria where he identified problems such as increased pollution and environmental injustice as resulting from poor formulation and implementation of environmental law in the country. He argues that despite environmental laws and policies aimed at ameliorating these problems, the situation in Nigeria seemed degenerating because the laws were not effectively enforced. Despite its relevance, Oyebode’s study falls short of spelling out the politics surrounding natural resources management. At best, it took issue with environmental laws as though these work out of a political vacuum. Politics, I argue, is crucial to understanding the complex relations between policies of nature and how society uses natural resources.

Relating to Zimbabwe, scholars contend that national-level policies governing natural resources have problems (Keeley & Scoones, Citation2000; Mangena, Citation2014; Murphree & Mazambani, Citation2002). Despite the existence of these laws, these scholars noted regulation gaps. It is important to note that while the constitutional provisions of environmental management in Zimbabwe provided legal specifications, no effort was made by government to come up with an ethical framework. The ethical framework would augment these legal specifications with a view to expand the scope of this policy to include the interests and rights of other important species in the environment (Mangena, Citation2014). Earlier, Murphree and Mazambani (Citation2002) argue that policy in Zimbabwe has shown itself to be a weak driver of change; indeed it can be suggested that it has been more of a deterrent than a driver. The two scholars specifically focused on policy on wildlife and established that the powerful alliance between bureaucracy and science evident in Zimbabwe’s environmental policy history has undoubtedly led to advances in the understanding of the environmental dynamics that have been operative in the country. Broadly, as well, they argue that policies however at times compromised an essential component of good science because awareness of uncertainty disappears when science interacts with policy. Policy also has the danger of excluding insights from local experience and civil science through “processes of ‘black-boxing,’ whereby disputes are closed, fundamental uncertainties, or questionable premises, are closed from further investigation, or just simply ignored” (Keeley & Scoones, Citation2000).

Resultantly, environmental management in Zimbabwe faces complex challenges of reconciling the often conflicting demands of various stakeholders. This is demonstrated by conflicts concerning natural resources where conservationists and local resource users disagree on how resources should be used. A political ecology approach, therefore, helps us flash out this web of interactions and to show how it affects natural resources use. Political ecology deliberately avoids putting emphasis on such theories as the tragedy of the commons which has inadvertently legitimised state intervention in natural resources management. Because natural resources require the state in order to avoid destruction, states often impose control over the conservation of natural resources. As Barrow et al. (Citation2016) posit, much of sub-Saharan Africa has undergone various reforms in land and natural resources management; that is; there has been a move from indigenous, community and collective tenure to state policies for control of land and resources. However, some policies run the risk of neglecting the conservation values of affected communities.

The basic policy stance embodied in different legislations that I interrogated includes environmental management structure, fast track land reform, farm brick use, curio industry regulations and associated regulations gaps. However, contradiction marks the Zimbabwe legislative system and that renders the environmental management system “disorderly”. Policy decisions and ad hoc policy interventions have environmental implications because they are fragmented, difficult to enforce and some provisions allow degrading of the environment. This negatively shapes the environmental resource use and result in environmental degradation in Zimbabwe.

The subsequent section briefly summarises the methodology used. The rest of the discussion reflects on how conservation legislation in Chivi has given rise to opposite results with negative impact on both the environment and the local communities.

3. Study area

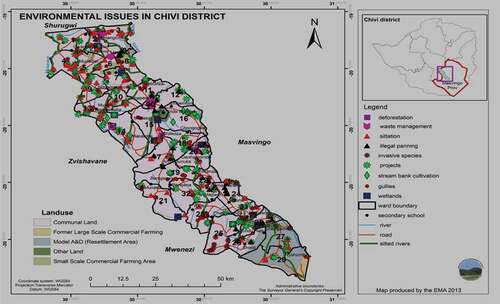

The data discussed in this paper is based on a study conducted in Chivi District, in the western part of Masvingo Province, Southern Zimbabwe. It has a total population of approximately 166277 inhabitants comprising 36382 households (Central Statistics Office, Citation2012). According to Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (Citation2017) poverty prevalence rate in Chivi District is as follows; Poverty 67.95, Extreme poverty 23.1%, Poverty gap 29.0% and Poverty severely index 15.1%. Chivi district is a semi-arid area falling under Agro-ecological natural region IV and V and in the drought-prone region of the country Vegetation in Natural Region (NR) IV depicts a drier climate than in III and the species dominating depends on the location and soils and NR V region has very dry climate and is characterized by near absence of miombo woodland species (ZINGSA, Citation2020). The District was selected because it is frequently subject to seasonal droughts and thus the high incidence of droughts means that the environmental resources in the area are at risk. Similar studies on the district confirms that in Chivi, communities are struggling to maintain their natural resources in a context where immediate survival needs outweigh any concerns for ecological sustainability (Macheka et al., Citation2020). In view of this, the key to survival is the capacity of households to earn enough cash to purchase food and to rely on their immediate environment. The state of environment in Chivi is shown in .

4. Data collection and analysis

This study adopted a qualitative research methodology that is exploratory in nature. As Yates (Citation2004) argues, qualitative research uses any methods that rely upon primary source materials, where very often the “data” are not numerical. This approach is subjective and holistic and therefore capable of adjustment in response to the data collected. The approach permitted the understanding of lived experiences for communities in Chivi District.

Data for the study were gathered through a combination of document review and interviews. With regard to the document review, the study reviewed existing environmental acts, policies and resolutions, journal articles on political ecology and environmental regulations were consulted, published and unpublished literature such as environmental reports and records were obtained from EMA and Chivi RDC. From the literature, the researcher found the supporting literature for which the basis for the discussion was based.

Data from the literature review were complemented with semi-structured interviews with a total of 45 participants. Semi-structured interviews gave me room for probing and interrogating the participants. The sample from each group was selected as presented in table below

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Community members who consists of farmers,Footnote1 traditional artifacts sellers,Footnote2 Marula Nut Co-operativeFootnote3 were conveniently selected because they mostly rely on natural resources for a livelihood and are normally viewed by state as “users and abusers” of the environment. I ensured that among the farmers and traditional artifact sellers, women were the main targets because the key informants who were previously interviewed were dominated by men. The community members were questioned about their experiences in accessing and using natural resources as well as their understanding and interpretation of environmental regulations in place. I purposively sampled state actors because they are legally empowered to protect the environment through regulating and controlling access to, and use of, natural resources; are custodians of the environment and they are also watchdogs of the environment through monitoring villagers who abuse land and forest resources. These state actors were chosen in order to understand and evaluate the environmental management regulations and how they are implemented in Chivi District.

To make sense of the desktop research and interviews, I subjected the data to a thematic analysis. As Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) argue, thematic analysis is a qualitative analytic method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data and it minimally organises and describes the data set in detail and interprets various aspects of the research title. Thus, the data were structured in accordance with the themes that had emerged. The detailed descriptions, narrative vignettes, and direct quotes from interviews that I present follow these themes. I used excerpts from the interviews to show what the informants said regarding the issues under study.

In keeping with ethical considerations, interview respondents were anonymised. I assured privacy to participants and private information was to remain relatively confidential. I deliberately avoided dissemination of sensitive information that matched personal information with the true identity of research participants, hence participant names remained anonymous.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. The complexity of environmental management in Zimbabwe

Specifically to Zimbabwe, it is worth noting that the old constitution (amended in 2000) did not have any specific clause to provide for the protection of the environment (Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2000). As a result the government of Zimbabwe promulgated the EMA in 2002 and a draft National Environmental Policy in 2003 to provide legal specifications on how the environment would be protected. Though EMA was a consolidated environmental legislative measure, some acts relating to environmental management had to be repealed and incorporated into the EMA in order to ensure consistency with the social, economic and political demands of the country (Mukwindidza, Citation2008). While these environmental legislations are administered by government’s departments such as RDC, Forestry Commission, EMA, and traditional leaders, the Government of Zimbabwe has maintained legal authority over natural resources. The state has implicit authority to act as the manager, administrator, facilitator and general overseer of community resources.

This is demonstrated in the legal framework that presents dual allocation of roles between state institutions and traditional leaders. The RDC is empowered as “appropriate authorities” to control the utilisation and management of natural resources in communal areas. There are specific laws that secured the authority of the RDC in natural resources management. The Communal Lands Act (Chapter 20:04) defines RDC as land authorities (with powers to allocate land under their jurisdiction, in conjunction with District administrators). The Parks and Wildlife Act (Chapter 20:14) designates RDC as appropriate authorities over wildlife resources in their areas, and the Communal Lands Forest Produce Act (Chapter 19:04) vests them with the power to grant licenses for timber concessions in communal area. However, sustainability of managing the resources referred to in the acts is problematic. It creates parallel functions between traditional leadership and state (RDC) in the conservation of natural resources. These have implications on the environment. This is so because the traditional leaders also have authority, jurisdiction and control over the communal land or other areas for which they have been appointed, and over persons within those communal lands or areas (Constitution of Zimbabwe, Citation2013).Footnote4 The New Constitution of Zimbabwe gives authority, jurisdiction and control over land to traditional leaders but legislation prior to the constitution reserves primary authority over allocation of land to the RDC. This opened up a debate on the complexity of environment management that makes the whole set-up disorderly. It seriously compromised sustainable natural resource management as it creates the possibility for competing jurisdictions in the rural areas.

The state did not only play a role in policy formulation but it also extended its political control over implementation as it allowed its state agents such as EMA, Forestry Commission and the RDC, to be administrators over the duties assigned to traditional leadership thereby undermining the powers of traditional leaders. While the constitutional provisions of environmental management in Zimbabwe is addressed on a regulatory spectrum, no effort was made by government to ensure that there is no conflict between the RDC and local leadership at implementation level. Clearly, both local governments and traditional leaders have responsibility over environmental protection, which often leads to conflicts between state institutions and traditional ones (Chigwata, Citation2016). Whilst EMA oversees the management of natural resources, there is duplication of roles and interests of traditional leaders and RDC and no clear division of responsibilities with regard to environmental matters. The multi-institutional system of natural resource governance therefore at times provides a conducive breeding space for conflict between the state actors and traditional leadership. A clearer delineation of competency between rural local authorities and traditional leaders with respect to environmental conservation is missing (Chigwata, Citation2016). Whilst promoting democracy through elected rural local governments, institutions of traditional leadership are no longer respected by the community.

This disconnection between policy and practice in the management of natural resources in Zimbabwe was corroborated by one headman, echoing his dissatisfaction with the environmental management set-up in place,

The monitoring of the environment by traditional leaders has its own challenges. In my area of jurisdiction, there is lack of respect for traditional leadership and village heads. Can you imagine someone questioning the authority of the District Development Coordinator and claim that they have rights to use natural resources the way they want? People in my community claim ownership of the resources and as a result do not manage natural resources sustainably. Village heads in Masaite, Mhike and Paringara villages are also settling people near rivers and on grazing areas.Footnote5

These events are attributed to the fact that the endorsement of environmental laws and acts is exclusively the preserve of the EMA and RDC. The account from the headman above reflects direct implications on the effectiveness of the regulations they intend to implement. The effective legal systems should be best founded on the beliefs, values and opinions of the society. Yet the current hierarchy in issues pertaining to the conservation of resources strips the local community of its sovereignty and control over resources. As a result, the area faces high level of environmental degradation ranging from deforestation to gully formation. The above observations mirror findings of studies in Zambia, Mozambique, Kenya and Tanzania (Chabal & Daloz, Citation1999; Hyden, Citation1980; Nelson et al., Citation2007; Van de Walle, Citation2001). The governance norms in sub-Saharan Africa reflect that the dominance of state institutions is the instrumentalism of disorder and ambiguity for political ends, the collusive private appropriation of public resources and weak rule of law (Nelson & Agrawal, Citation2008).

It is because of such a system that, Chivi District environment has degraded, yet the community depends directly on the environment for their livelihood. Resultantly, the area witnessed an increase in gullies because of lack of effective supervision of the environment. The resource situation also worsened after the year 2000. I argue that the introduction of “a half-baked policy” where people were allowed to settle anyhow in Chivi District had negative effects on resource use and management and deserves a lengthy analysis.

5.2. Fast track land reform and environmental degradation

During the fast track land reform era that commenced in 2000 in Zimbabwe, people were given freedom to settle anywhere and anyhow and that led to uncontrollable behaviour. The government of Zimbabwe embarked on the fast track land reform programme in a bid to improve the amount of land being given up for resettlement as well as to empower the black Zimbabweans. The programme, however, resulted in vandalism of existing structures such as restricted forests, contour ridges, abandoning of designated areas such as wetlands and stream banks that were then converted into farming units (Chigwenya, Citation2000). It saw desperate land seekers among them war veterans and supporters of ZANU PF invading white owned farms and forcing white commercial farmers to vacate the farms, and the whole process was violent and chaotic (Mangena, Citation2013).

Similarly, the effects of the fast track land reform programme on the environment in Chivi District are linked to the land use systems that were being created under the programme and the land use systems involving settlement, mining and farming among others. The ushering in of freedom to settle which was facilitated by the fast track land reform in Zimbabwe led to expansion of land for farming in Chivi areas especially in resettlement areas (See model A and D resettlement in ). The EMA officer explained that,

There is clearing of land which was once reserved for grazing in wards 27 and 28 under Nyahombe Resettlement Scheme. This leads to deforestation and the major impact of land reform programme have been soil erosion, deforestation, water contamination and movement of earth among others.Footnote6

While state actors do not attribute this to the fast track land reform, it is clear that it left trails of destruction to the environment and specifically deforestation. Scholars argue that the fast track land reform resulted in massive resettlement in areas that were neither uninhabited nor used for agricultural purposes (Mapira, Citation2017; Scoones et al., Citation2012). It led to the relaxation of environmental regulations because some people used the name of the ruling party to protect themselves from prosecution.Footnote7 Similar study on fast track land reform by Chivuraise et al. (Citation2016) also revealed that the programme resulted in deforestation as people cleared virgin land for building homes and for cultivation and other agricultural needs.In other words, there is a strong relationship between politics on the one hand and access to, and use of, natural resources in Chivi district. This is demonstrated by one conservationist, who explained that,

Since the fast track land reform, village heads are allocating land in an unregulated manner. As a result, pools in rivers no longer exist and siltation has threatened aquatic animals such as crocodiles. People who settle in undesignated areas cultivate water chains and there are cases of people settling near roads, causing siltation of rivers.Footnote8

In the context of the land reform in question, the natural resource base in Zimbabwe has been vulnerable because political affiliation and decisions confer individuals with the right to “destroy” the environment for personal gains.

Moreover, while the traditional conservation practices in the country put restrictions on the natural resources’ access and use, they were no longer respected during the post-2000 period. As Chief S explained,

Marambakutemwa [restricted forests] used to exist and were respected but they were destroyed during land resettlement in 2002 and no longer exist save for one area near the mountain. There used to be ‘zvidhunduru’ [beacons] which were removed by people during the land reform period and that led to siltation of riversFootnote9

The headman in Chivi South also lamented that,

Village heads are allocating land in an unregulated manner and people settle near vleis [shallow natural pools of water], rivers and in wetlands and, the political leaders do not allow destruction of such structures for political mileage.Footnote10

Rural populations in Zimbabwe safeguarded themselves against eviction from illegal settlements by associating with the ruling party. Because of the politics surrounding fast track land invasions in Zimbabwe, both the state actors such as EMA and RDC on the one hand, and traditional leaders on the other, became powerless to stop communities from opening up fields within the forest or from destroying fields. In this context, where the political situation of the day determines how the environmental resources in a given community can be accessed and exploited by the local people, environmental degradation in Chivi persists. The livelihoods of the rural communities that are dependent on the immediate environment are affected mainly because resource management is influenced by the politics of the area.

Other studies in Zimbabwe have noted that there was generally more forest cover in many areas before the Fast Track Land Programme of the year 2000. A case of Mafungautsi Forest Reserve in Gokwe District in Central Zimbabwe shows that prior to 2000 the trees in the forest were generally larger and of greater biomass. The woodlands were also denser than those of the surrounding communal areas. The study of Gokwe District reflects that after June 2000 there were fewer resources for fire fighting and a culture of acting with impunity was quickly developing amongst the villagers in Zimbabwe (Mapedza, Citation2007). A number of households have invaded the reserved forests in Gokwe, where they use fires to open up fields for cultivation. Similarly, research carried out in Gutu District, reflects that there was rampant cutting down of trees under the fast track land reform programme and the areas adjacent to Serima, Gutu and Denhere Communal Lands are almost devoid of trees (Zembe et al., Citation2014). The major causes being firewood collection and need to open up more land for arable purposes due to ever increasing population in the resettlement areas.

Interestingly, this story of land reform and environmental degradation has been told over and over again not only in Zimbabwe but in other parts of Africa. The environmental sustainability aspect has remained a neglected dimension in land reform programmes in Africa. For instance, Tanzania also engaged on a land reform programme although it has a different political context with other land reform programmes in Southern Africa. The land reform in Tanzania namely “villagisation” was aimed at resettling scattered rural households into villages with the intention of transforming agriculture and improving productivity (Wynberg & Sowman, Citation2007). Lessons drawn from this programme shows that the exercise led to widespread overgrazing, deforestation, erosion and overexploitation of wildlife without expected gains in agricultural productivity (Mlay, Citation1982). Similarly the land reform programme in South Africa in 1994 is argued to have also neglected the environmental management issues. Despite the inclusion of environmental guidelines within the policy framework, in practise there is not an overall environmental dimension in the implementation of the South African land reform programme (Manjengwa, Citation2006). In other words, since the responsibility for natural resource management in South Africa is spread over different national and provincial ministries, the institutional framework has generally failed to integrate approaches to land use and thus natural resource management remains sectorial and fragmented (DLA (Department of Land Affairs [South Africa]), Citation1997).

The above experiences reflect that African governments embarked on land reform programme without seriously considering its disastrous impact on the environment. There are limited checks and balances to prevent further degradation. Though efforts are being made by environmentalists to make governments aware of the effects of environmental degradation, the damage has already been done; the areas are already deforested.

5.3. Farm brick use regulation and deforestation

The government of Zimbabwe, through the Ministry of Local Government and Public Works and National Housing approved use of farm bricks in house construction at rural business centres in 1986. It was further stipulated in its Circular 70 of 2004 where the Ministry states its minimum standards for building materials for low-cost housing. Walls shall be constructed of burnt clay bricks/blocks, cement bricks/blocks and stabilised soil bricks/blocks.Footnote11 Farm brick use was approved to promote better housing facilities for rural business centres. This move has facilitated housing construction at business centres which in most cases is done by outsiders who are not from Chivi district. Ironically, the state actors are silent about environmental degradation caused by farm brick use between 1986 and 2013 which, as one RDC officer explained:

In 2013, Chivi RDC, EMA and the Forestry Commission inspected the place where farm brick moulding was supposed to take place and consultation was done with local leadership. Resultantly, the RDC gave brick moulders permits in groups in 2013.Footnote12

Though authorities had issued licenses to farm brick producers in 2013, they observed that communities were abusing natural resources and continued producing the bricks for commercial purposes. To prevent further degradation, the RDC withdrew licenses in the year 2014. Chivi RDC informed village heads to make sure that there should be no brick moulding for commercial purposes. However, illegal farm brick production continues to cause further destruction through rampant destruction of trees for farm brick baking and the formation of a number of gullies. Communities leave gullies to naturally recover, which in most cases, does not happen.

As argued before, the government of Zimbabwe is not providing sustainable solutions to environmental degradation. The withdrawal of licences, moreover, did not prevent the communities from using farm bricks because the practice remained legal. There is a disconnection between the two because as long as the housing policy is in use there will be rampant cutting down of trees. The reaction of RDC and EMA to problem of deforestation and degradation was not practical and did not do anything to improve environment governance. The dire situation did not end because the legislative piece of government approves use of farm brick.

As a result, farm brick use has led to the depletion of natural resources in Chivi. While policies exist, environmental managers are failing to address the problem without other supportive legal mechanisms. Instead, policy has only helped to further facilitate the destruction of natural resources. Unbeknown to state actors, such kind of policies affect the environmental resource base for many districts in Zimbabwe, Chivi inclusive, because they cannot stand the demand for firewood to be used in brick heating. The approval of farm bricks was viewed as a destructive policy by the government, as is demonstrated by the following interview excerpt:

The government of Zimbabwe is implementing and promoting retrogressive policies and strategies that affect the environment, they need to impress people by introducing the use of farm bricks yet they do not consider how it will affect the land and forests.Footnote13

In addition, protected tree species are also under threat of extinction as they are constantly cut down for making bricks. The way trees are harvested is unsustainable as there is no plan to replace the forests that have been destroyed. While the Ministry of Local Government and Public Works and National Housing had approved farm brick use to quicken development at growth points and help rural communities, such a move has had a negative impact on the environment. Burned bricks are an environmental hazard, contributing to severe deforestation and land degradation given that there is excessive use of soil and wood in brick kilns (Hashemi et al., Citation2015). The following interview excerpt gives further details.

This has resulted in infrastructural development which has seen many shops, houses and offices being constructed using farm bricks but farm brick moulders leave the land with gullies and are destroying trees using them to heat the bricks. The wards near business centres such as wards are 6, 8, 12, 15, 26 and 30 witnessed massive destruction of trees and the development of gullies.Footnote14

Farm brick policy, therefore, becomes an agent and catalyst to gully formation. The policy was introduced more than three decades ago and its impact is now being felt in the rural communities yet the government of Zimbabwe is not making any effort to do away with the policy. At Mhandamabwe business centre in Chivi, farm brick moulding has reached alarming levels because people produce bricks and sell them to developers at business centres. It was further explained by a monitor that “within a short period of time, ten tickets were issued to illegal farm brick moulders who were moulding bricks near Mhandamabwe”.Footnote15 The fear of violence prevents monitors from apprehending suspects. He said moulders had become a threat because environmental monitors can be attacked by brick moulders,

Brick moulders are dangerous to approach because they attack you. I normally go there in the company of police and Headman. There is competition in moulding bricks because the brick moulders seek buyers for the bricks and do not tolerate any disturbances.Footnote16

Though no studies have been carried out in Southern Africa on farm brick use, these experiences speak to environmental degradation spreading out from urban centres in Africa. Though it is argued that in many parts of Sub-Saharan Africa rapid urbanisation has reduced rural population thus reducing rate of deforestation (Rudel, Citation2013); however, in cities and towns in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda, land speculation by wealthy urban residents has also driven-abetted by lack of land-use planning and control-loss and fragmentation of rangelands close to these cities (Flintan, Citation2011). These experiences reflect the rapidly growing trend in African cities and which is putting pressure on the natural resource base due to various demands of the urban dwellers.

5.4. Lack of curio industry regulations

Lack of curio industry regulation in Zimbabwe is equally a cause for concern. If use limits are not devised and enforced, natural resources will be subject to problems of potential destruction. Since independence in 1980, there has been an influx of tourists from South Africa who frequently buy artefacts made from wood by local people from the Chivi area (Makonese, Citation2008). The rural population uses the roadside as the market places for traditional artefacts namely Gwitima Bus Stop, Sese Bus Stop, Ngundu Business Centre and Lundi Business Centre. The craftsmen at these centres use a number of tree varieties which include endangered and protected species such as mahogany and amarula trees. The craft industry market has been in existence since 1980 but there is no legal specification that guides its operations. The market stall holders were only paying a fee to Chivi RDC up to 2005 when it was, however, not spared when the government of Zimbabwe launched Operation Murambatsvina in May 2005 to destroy all “illegal” residential buildings and clean up all businesses operating “illegally” (Makonese, Citation2008). The factors driving the upsurge in the woodcraft industry are the increased demand by tourists and the need by rural households to make an income.

The relaunch of the craft industry few years after 2005, at four different centres in the District is a threat to the environment. The craft industry in Zimbabwe worsens deforestation in the areas near craft centres. Its relaunch was illegal because there are no permits to approve the operations. The state actors and traditional leadership professed ignorance about the permits and licenses for the operations of the craft industry. Since no one is controlling the industry, very big trees are cut for crafting and no replacement is done.

There was also destruction of Chivumbwi Forest between Chikofa and Zihwa areas where a number of people cut down trees for traditional artefacts to sell. These craftsmen do not have harvesting permits and harvest trees in an unsustainable manner. Very big trees are cut for crafting and no replacement is done.Footnote17

The curio industry has proliferated in the District mainly because there is no curio regulation in the country. While it is acknowledged that the EMA and RDC acts speak to deforestation issues, I argue that a specific legislative piece to address crafting issues is non-existent. The two acts are coercive and thus rise to uncontrolled utilisation of forestry resources. Globally, curio business trade is deemed as the only sector with very low entry barriers hence many Zimbabweans are into this kind of business (Nyahunzvi, Citation2015). Similarly, in Chivi district, there are no proper regulations that bind wood carvers on harvesting of natural resources; hence its growth causes great damage to the environment. Whereas the felling of trees for carving is prohibited, there are no stipulated regulations that guide its operations. This reflects the gap in environmental management structures in the country. There is therefore continual destruction of trees for crafting. The lack of enforcement on environmental legislation that governs how people use tree resources for crafting makes it very difficult to see how the resources can be managed on a sustainable basis. Local traditional rules governing resource use by the community are also not respected.Footnote18

This issue of lack of legislation to control the activity is common in Zimbabwe. The study on the craft industry in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, established that there is high harvesting of natural resources to produce craft products due to the unregulated business environment (Zhou, Citation2017). Given the frequent unsustainable extraction rates in Chivi district area, the resource base will not sustain the woodcraft industry much longer. Previous studies also reveal that the woodcraft industry along the Masvingo-Beitbridge road in Chivi has largely contributed to deforestation in the district (Braedt & Standa-Gunda, Citation2000). The issue of regulation gaps, coupled with economic hardships, is impacting negatively on the existence of forest resources and, eventually, leads to deforestation. The enforcement of curio trading is very lax and sporadic outside the gazetted forest areas. It is partly due to lack of capacity and partly due to the fact that it is considered to be an industry that is playing a pivotal role in alleviating poverty or providing safety nets to otherwise impoverished rural households (Matose, Citation2006).

This industry is not sustainable because the increase of craft production damages the environment even though motivated by monetary gains, most carvers are blind to environmental concerns as environmental monitor B explains,

Community members are not allowed to cut down more than three wheelbarrows of wood as a way of ensuring sustainable use of the forest resources but despite that, people in the northern part of the district continue recklessly cutting down the trees for crafting. They sell crafting products to the nearby town, Zvishavane.Footnote19

The resources being used for crafting are extracted from the commons, they are free, and have low transaction cost at production level and no regulation for the industry. Despite possible adverse consequences on the resource base, government organizations and policy makers have hesitated to take action in controlling the use of indigenous trees for the woodcraft industry (Braedt et al., Citation2000, October 11–12). The scholars have further explained that the lack of knowledge about ecological effects caused by the timber harvest for the carving sector and possible negative effects for the economy of the industry are main reasons for the reluctance to regulate the industry.

5.5. Regulation gaps in forest management

There are some sections in the environmental legislation that create regulation gaps that lead to further deforestation in Zimbabwe. The Forest Act Chapter 19:05 of Zimbabwe prohibits the communities from selling forest produce yet its supporting regulation Statutory Instrument 116 of 2012 Forest (Control of Firewood, Timber and Forest Produce) permits the selling of forest products. The statutory instrument was meant to ensure enforcement of the Forest Act. However, it creates confusion and distortions in the community. Specifically, section 3(1) (a) which stipulates that timber selling permit or trade in any firewood can be obtained in every district where he or she proposes to operate. The instruments and acts should have clarified areas where harvesting of timber is applicable. As one official notes, though the instrument is applicable in areas with many trees, it should not be applicable to drought-prone districts such as Chivi district.Footnote20 The regulations, I argue, have a one size fits all approach yet the districts and communities are resourced differently. This complex relationship among forest regulations has implications on the environment. These have led to commercialisation of firewood and timber throughout the country and the district. As a result of such instruments and economic problems, communities living in the major rural service centres and Chivi Growth Point cut trees and sell fresh firewood to residents in the nearby peri-urban centres where electricity has become a scarce resource.

The frequent power outages which have hit Zimbabwe as a result of poor economic policies have not spared Chivi district. The persistent electricity black-outs in Chivi has forced Chivi residents to adopt firewood as an alternative source of energy, hence firewood selling becomes a viable enterprise that can generate income, employment and rural livelihood diversity. There is therefore, increased demand for firewood for domestic use as well as for commercial use in Chivi. The following interview excerpt sheds more light,

The most affected woodlands in Chivi district are around wards 6, 7 and 8 which are close to Mhandamabwe Rural Service Centre, wards 11, 12, 15 and 30 which are close to Chivi Growth Point then wards 25 and 26 where people sell firewood at Ngundu Rural Service Centre.Footnote21

The regulation gaps and increased demand for firewood have forced the unemployed and school-going age groups (during weekends) to diversify their livelihood options through selling of firewood. However, although this livelihood activity proved to be viable and allowed them to generate an income, the sustainability of the affected forests is compromised. A study of firewood selling in Bulawayo similarly claimed that it was difficult to stop residents from selling firewood (Dube et al., Citation2014). The economic quagmire, in which Zimbabwe has found itself, with its concomitant high rates of unemployment and very low incomes, has and will continue to encourage the sale of firewood in Zimbabwe.

The main concern by environmentalists is that in Chivi district, the effect of deforestation is not being felt by forest resource users. The impact affects Chivi rural areas, where the trees are cut down and the users are the people who live in the peri-urban places of Chivi district. It is an economic activity that impacts negatively on the environment and may lead to tree species extinction especially in cases where the rural Chivi communities are involved in cutting whole trees or uprooting live ones.

These experiences showing the disconnection between policy and practice are not unique to Zimbabwe only. A study of four cities in Uganda namely Mbarara, Ntungamo, Katakwi, and Kasese reflects regulation gaps that lead to further deforestation. For instance, the 2001 Forestry Policy in the country sanctions civil society organizations to manage the country’s forest resources (Rwakakamba, Citation2009). Ironically, there are no networks of civil societies at grassroots levels that exist to fight for collaborative forest management issues. Rwakakamba’s study has revealed several cases in Mbarara, Ntungamo, and Kasese where farms and other developmental projects were established without carrying out environmental impact assessments. This reflects the relaxation by governments in Africa in taking responsibility for conservation and thus reluctant to enforce laws.

6. Conclusion

This paper sets out to understand how government environmental frameworks impact on environmental management in Chivi district, Southern Zimbabwe. The study concludes that lack of curio industry regulations and fast track land reform programme policy engenders degradation of the natural resources in Chivi District. In addition, farm brick use and Statutory Instrument 116 of 2012 Forest (Control of Firewood, Timber and Forest Produce)regulations are fragmented and difficult to enforce and there are some provisions that sanction people to degrade the environment. Findings point out that politicising the access to and control over natural resources damages the scarce environmental resources and lies at the core of ecological problems which affect sustainable management of natural resources.

The detailed analysis of the regulatory frameworks and politics over environmental resources in Chivi District draws attention to a contradictory stance between policy objectives and practice. The paper thus concludes that confusion and chaos within the legal framework will eventually impinge on efforts aimed at sustainable conservation of forest resources by state institutions and community. The political ecology approach used brought awareness to more broadly defined relations of power and difference in interactions among Chivi District community and their immediate environment. The approach explains that resource use and power dynamics in everyday interactions goes beyond the local community. Thus it explains that environment degradation in Zimbabwe is not due to simple problems linked to scientific and technical solutions but is hastened by human activities and other forces as environmental management practises and regulations that facilitate further degradation. The political ecology approach that was used has also developed an insight into a diverse range of complex issues in natural resource access and use in a drought prone area. This makes it possible for further research and there is a need to build on the theoretical framework used and to apply drought-prone-based approaches and test them in detail.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mavis Thokozile Macheka

Dr Mavis Thokozile Macheka is a lecturer for Development Studies at Great Zimbabwe University, Zimbabwe. She is also a research co-consultant, research team member and a development practitioner. Her research focus is on ecological sustainability and community development. As a development practitioner, she takes into consideration political ecology framework as a lens with which to approach societal environmental problems. In her previous research on environment and rural development, she has found such an approach useful. Dr Macheka is also working on a research project on the role of higher and tertiary education institutions on ecological sustainability during times of disasters. Thus, for Mavis, this present research is part of her envisaged study in understanding the relationship between society, politics and the environment in Zimbabwe.

Notes

1. Farmers were chosen because they are the users of the land.

2. Traditional artifact sellers also represent forest resource users, because this group uses trees and soapstone to craft traditional artifacts which they sell to tourists along the Harare-South Africa highway.

3. Marula Nut Co-operative is an indigenous co-operative operated by Chivi rural women who are engaged in producing products such as jam and cooking oil from their own forest fruit called amarula. The co-operative members are target participants because they use forest resources in their business.

4. Section 283, Constitution of Zimbabwe.

5. Interview with Headman Z, Chivi South, 27 June 2016. All interviews for this article were conducted by the author, in whose archives the transcripts are lodged.

6. Interview with EMA Officer, Chivi District EMA Office, 16 February 2016.

7. Interview with Environmental Monitor B, Chivi North, 22 June 2016.

8. Interview with Conservationist, Chivi North, 13 March 2016.

9. Interview with Chief S, Chivi South, 24 June 2016.

10. Interview with Environmental Monitor C, Ward 19, Chivi South, 27 June 2016.

11. See Section 3.15 Circular 70(2004), Ministry of Local Government, Public Works and National Housing, Zimbabwe.

12. Interview with RDC Environmental Management Committee Officer, Chivi RDC, 8 March 2016.

13. Interview with Mr Y, Chivi Growth Point, 8 March 2016.

14. Interview with EMA Officer, Chivi District EMA Office,16 February 2016.

15. Interview with Environmental Monitor D, Chivi North, 22 June 2016.

16. Interview with Environmental Monitor D, Chivi North, 22 June 2016.

17. Interview with Headman Z, Chivi South, 27 June 2016.

18. Interview with Mr Jay, Chivi South, 27 June 2016.

19. Interview with Environmental Monitor B, Chivi North 22 June 2016.

20. Interview with Forestry Officer Z, Chivi Forestry Commission, 8 March 2016.

21. Interview with EMA Officer, Chivi District EMA Office, 16 February 2016.

References

- Adams, W., & Hutton, J. (2007). People, parks and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conservation and Society, 5(2), 147–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26392879

- Barrow, E. K., AnguAngu, S., Bobtoya, R., Cruz, S., Kutegeka, B., Nakangu, M., & Savadogo, G. W. (2016). Bringing improved natural resource governance into practice: An action learning handbook II for Sub-Saharan Africa, Responsive Forest Governance Initiative (RFGI), CODESRIA, IUCN and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

- Batterbury, S. P. J. (2015). Doing political ecology inside and outside the academy. In R. Bryant (Ed.), The international handbook of political ecology (pp. 27–43). Edward Elgar.

- Batterbury, S. P. J. (2018). Political ecology. In N. Castree, M. Hulme, & J. Proctor (Eds.), The companion to environmental studies (pp. 439–442). Routledge.

- Benson, D. A., & Jordan, A. (2015). Environmental policy: Protection and regulation. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), international encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (Vol. 7, 2nd ed., pp. 778–783). Elsevier.

- Bixler, R. P., Dell’Angelo, J., Mfune, O., & Roba, H. (2015). The political ecology of participatory conservation: Institutions and discourse. Journal of Political Ecology, 22(1), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.2458/v22i1.21083

- Braedt, O., Schroeder, J.-M., Heuveldop, J., & Sauer, O. (2000, October 11–12). The miombo woodlands – A resource base for the woodcraft industry in southern Zimbabwe. In International Agricultural Research: A contribution to crisis prevention. Proceedings of the ‘Deutscher Tropentag. Germany: University of Hohenheim. Retrieved June 10, 2018, from http://ftp2.de.freebsd.org/pub/tropentag/proceedings/2000/Full%20Papers/Section%20II/WG%20c/Braedt%20O.pdf. December 2007

- Braedt, O., & Standa-Gunda, W. (2000). Woodcraft markets in Zimbabwe. International Tree Crops Journal, 10(4), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01435698.2000.9753021

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryant, R. (2015). The international handbook of political ecology. Edward Elgar.

- Central Statistics Office. (2012). Population Census: A Preliminary Assessment, (C.S.O. Harare).

- Chabal, P., & Daloz, J. P. (1999). Africa works: Disorder as political instrument. James Currey Ltd.

- Chigwata, T. (2016). The role of traditional leaders in Zimbabwe: Are they still relevant. Law, Democracy and Development, 20(1), 69–70. https://doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v20i1.4

- Chigwenya, A. (2000). An assessment of the environmental impact of resettlement programmes in Zimbabwe. University of Zimbabwe.

- Chivuraise, C., Chamboko, T., & Chagwiza, G. (2016). An assessment of factors influencing forest harvesting in smallholder tobacco production in Hurungwe District, Zimbabwe: An application of binary logistic regression model. Advances in Agriculture, 2016, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4186089

- Connelly, J., Smith, G., Benson, D., & Saunders, C. (2012). Politics and the Environment (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (section 283) Act, 2013 [Zimbabwe], 22 May 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ed090f4.html

- De Gobbi, M. (2020). Environmental integrity and doing business in Zimbabwe: Challenges and engagement of sustainable enterprises, ILO Working Paper 2 (Geneva, ILO).

- DLA (Department of Land Affairs [South Africa]). (1997). (White Paper on South African Land Policy.

- Dovers, S., Edgecombe, R., & Guest, B. (2002). South Africa’s environmental history: Cases and comparisons. David Philip Publishers.

- Dube, P., Musara, C., & Chitamba, J. (2014). Extinction threat to tree species from firewood use in the wake of electric power cuts: A case study of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Resources and Environment, 4(6), 260–267.

- Dzingirai, V. (2003). 'CAMPFIRE is not for Ndebele Migrants': The impact of excluding outsiders from CAMPFIRE in the Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe. Journal of Southern African Studies, 29(2), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070306208

- Flintan, F. (2011). Broken lands: Broken lives? Causes, processes and impacts of land fragmentation in the Rangelands of Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda (Research Report, Nairobi, Regional Learning and Advocacy Programme (REGLAP)) p.159.

- Forsyth, T. (2015). Integrating science and politics in political ecology. In R. Bryant (Ed.), The international handbook of political ecology (pp. 103–116). Edward Elgar.

- Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe. (2000). Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

- Hashemi, A., Cruickshank, H., & Cheshmehzangi, A. (2015). Environmental impacts and embodied energy of construction methods and materials in low income tropical housing. Sustainability, 7(6), 7866–7883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7067866

- Hornborg, A. (2017). Artifacts have consequences, not agency: Toward a critical theory of global environmental history. European Journal of Social Theory, 20(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431016640536

- Hove, G., Rathaha, T., & Mugiya, P. (2020). The impact of human activities on the environment, case of Mhondongori in Zvishavane, Zimbabwe. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 8(10), 330–349. https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2020.810021

- Hyden, G. (1980). Beyond Ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an uncaptured peasantry. Heinemann Educational.

- Josh, S. (2015). Postcoloniality and the North–South binary revisited: The case of India’s climate politics. In R. Bryant (Ed.), The international handbook of political ecology (pp. 117–130). Edward Elgar.

- Keeley, J., & Scoones, I. (2000). Knowledge, power and politics: The environment policy making in Ethiopia. Journal of Modern African Studies, 38(1), 98–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X99003262

- Kraft, M. E. (ed). (2018). Environmental Policy and politics (7th ed.). Routledge.

- Kull, C. A., & Rangan, H. (2016). Political ecology and resilience: Competing interdisciplinarities? In B. Hubert & N. Mathieu (Eds.), Interdisciplinary between natures and societies (pp. 71–87). PIE Peter Lang.

- Mabogunje, A. L. (1995). The environmental challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 37(4), 4–10. https://doi,org/10.1080/00139157.1995.9929233

- Macheka, M. T., Maharaj, P., & Nzima, D. (2020). Choosing between environmental conservation and survival: Exploring the link between livelihoods and the natural environment in rural Zimbabwe. South African Geographical Journal, 103(3), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2020.1823875

- Makonese, M. (2008). Zimbabwe’s Forest Laws, Policies and Practices and Implications for Access, Control and Ownership of Forest Resources by Rural Women [ A Masters Dissertation Submitted at the Southern and East African Regional Centre for Women’s Law]. Faculty of Law, University of Zimbabwe.

- Mangena, F. (2013). Moral leadership in a politically troubled nation: The case for Zimbabwe’s decade of violence. In E. Chitando (Ed.), Prayers and Players: Religion and Politics in Zimbabwe (pp. 231). SAPES Books.

- Mangena, F. (2014). Environment policy, management and ethics in Zimbabwe 2000–2008. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 6(10), 224–240.

- Manjengwa, J. (2006). Natural resource management and land reform in Southern Africa Commons Southern Africa Occasional Paper Series, 15 Centre for Applied Social Sciences and Programme for Land Reform and Agrarian Studies.

- Mapedza, E. (2007). Forestry policy in colonial and post-colonial Zimbabwe: Continuity and change. Journal of Historical Geography, 33(4), 833–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2006.10.022

- Mapira, J. (2017). Land degradation and sustainable development in Zimbabwe: An historical perspective. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 2(9), 119–185. http://dx.doi.org/10.46827/ejsss.v0i0.283

- Matose, F. (2006). Co-Management options for reserved forests in Zimbabwe and beyond: Policy implications of forest management strategies. Forest Policy and Economics, 8,4(4), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2005.08.013

- Maurya, P. K., Ali, S. A., Ahmad, A., Zhou, Q., Da Silva Castro, J., Khane, E., & Ali, H. (2020). An introduction to environmental degradation: Causes, consequence and mitigation. In V. Kumar, J. Singh, & P. Kumar (Eds.), Environmental degradation: Causes and remediation strategies (Vol. 1, pp. 1–20). Agro Environmental Media, Agriculture and Environmental Science Academy.

- Mawere, M. (2013). A critical review of environmental conservation in Zimbabwe Africa. Spectrum, 48(2), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203971304800205

- Mlay, W. F. I. (1982). Environmental implications of land-use patterns in the new villages in Tanzania. In J. W. Arntzen, L. D. Ngcongco, & S. D. Turner (Eds.), Land policy and agriculture in Eastern and Southern Africa. United Nations University Press.

- Mukwindidza, E. (2008). The Implementation of Environmental Legislation in Mutasa District of Zimbabwe [ Unpublished Master of Public Administration Degree]. University of South Africa, p.34.

- Murphree, M. W., & Mazambani, D. (2002). Policy Implications of Common Pool Resource Knowledge: A Background Paper for Zimbabwe [ Unpublished Paper for the Policy Implications of Common Pool Resource Knowledge in India]. Tanzania and Zimbabwe Project.

- Nelson, F., & Agrawal, A. (2008). Patronage or participation? Community-Based natural resource management reform in Sub-Saharan Africa. Development and Change, 39(4), 557–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00496.x

- Nelson, F., Nshala, R., & Rodgers, W. A. (2007). The evolution and reform of Tanzanian wildlife management. Conservation and Society, 5(3), 232–261. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26392882

- Nyahunzvi, D. K. (2015). Negotiating livelihoods among Chivi Curio traders in a depressed Zimbabwe tourism trading environment. An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 26(3), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2014.974065

- Oyebode, O. J. (2018). Impact of environmental laws and regulations on Nigerian environment. World Journal of Research and Review, 7(3), 9–14.

- Rossouw, N., & Wiseman, K. (2004). Learning from the implementation of environmental public policy instruments after the first ten years of democracy in South Africa. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 22(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154604781766012

- Rudel, T. K. (2013). The national determinants of deforestation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B, 368(1625), 20120405. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0405

- Rwakakamba, T. M. (2009). How Effective Are Uganda’s Environmental Policies? Mountain Research and Development, 29(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.1092

- Scoones, I., Marongwe, N., Mavedzenge, B., Murimbarimba, F., Mahenehene, J., & Sukume, C. (2012). Livelihoods after land reform in Zimbabwe: Understanding processes of rural differentiation. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2012.00358.x

- Tarr, P. (2003). Environmental impact assessment in Southern Africa. Paper Presented at the Southern African Institute for Environmental Assessment (SAIEA), Windhoek, Namibia.

- van de Walle, N. (2001). African economies and the politics of permanent crisis, 1979–1999. Cambridge University Press.

- Wynberg, R. P., & Sowman, M. (2007). Environmental sustainability and land reform in South Africa: A neglected dimension. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 50(6), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560701609810

- Yates, J. S. (ed). (2004). Doing social science research. Sage Publications in association with the Open University Press.

- Zembe, N., Mbokochena, E., Mudzengerere, F. H., & Chikwiri, E. (2014). An assessment of the impact of the fast track land reform programmee on the environment: The case of eastdale farm in Gutu District, Masvingo. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 7(8), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.5897/JGRP2013.0417

- Zhou, Z. (2017). Victoria falls Curio sector analysis: Insights through the lens of a dollarized economy. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(1), 1–19. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-85029159337&partnerID=MN8TOARS

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2017). PICES Enumerator’s manual,” mimeo ZIMSTAT.

- ZINGSA. (2020). Technical report on revision of Zimbabwe agro-ecological zones. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe under Zimbabwe National Geospatial and Space Agency (ZINGSA). Retrieved June 4, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349138874_Revision_of_Zimbabwe%27s_Agro-Ecological_Zones_Government_of_Zimbabwe_under_Zimbabwe_National_Geospatial_and_Space_Agency_ZINGSA_for_the_Ministry_of_Higher_and_Tertiary_Education_Innovation_Science_and_