Abstract

Spatial development plans can be vital tools to guide spatial development in rapidly urbanising towns and cities in the South. Yet, their efficacy in guiding spatial development in Zimbabwe’s volatile environment is increasingly questioned and remains little understood, at least empirically. This paper assesses whether master and local plans positively affect spatial development in cities, towns, and growth centres in Masvingo province. We found that spatial developments undertaken without the guidance of master and local plans are chaotic and result in disorderly settlements. However, the same is evident in urban centres with operative master and local plans. Unplanned settlements have emerged as pressure is mounting on local authorities to provide building land and housing for the ever-increasing urban populations. The blueprint nature and the cost of preparing spatial development plans have discouraged local authorities with intentions to prepare such plans and triggered the need to question their efficacy. Even for local authorities with operative master and local plans: the disregard of these plans by political and economic elites and the urban poor shows that the plans have, in most cases, become inhibitors of development in a rapidly urbanising world. Master and local plans remain essential tools for guiding spatial development in Zimbabwe as long as they become flexible and swiftly respond to the needs of the ever-growing urban population.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper focuses on approaches and tools for spatial development in Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe. Spatial development entails planning how, where and what space or land is used for and by whom. Zimbabwe, local authorities use various spatial development tools such as master and local plans to determine land-use zoning. Although such tools are vital in guiding spatial development, their effectiveness in Zimbabwe’s volatile environment is increasingly questioned and remains little understood. As a former British colony, Zimbabwe inherited these tools with little focus on the local context. Most local authorities are failing to finance these tools’ preparation, thus operating without them. However, spatial development undertaken without the guidance of master and local plans is chaotic and results in disorderly settlements. Master and local plans remain essential for guiding spatial development in developing countries, but their nature should be responsive, flexible and swift in evolving with time.

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanisation in African cities has caused myriad urban planning challenges (ZHANG, Citation2016; GÜNERALP et al., Citation2017; UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR AFRICA, Citation2017; HEINRIGS, Citation2020; MAWENDA et al., Citation2020) that affect the efficacy of spatial development tools. These challenges include urban sprawl, development of unplanned settlements, transportation problems, lack of social and physical infrastructure, crime and safety issues, social and spatial inequalities, and environmental deterioration (DODMAN et al., Citation2017; JIANG et al., Citation2021; MABASO et al., Citation2015). Consequently, it has become difficult for most local authorities in countries in the Global South, including Zimbabwe, to undertake meaningful control of development. A general disregard for planning rules and regulations has become the order of the day as most local authorities fail to align their planning systems with the emerging challenges of this era (HUANG et al., Citation2018; KIO-LAWSON et al., Citation2016).

The spatial development challenges are not only unique to Zimbabwe but are evident in other African countries like Nigeria and Tanzania (HUANG et al., Citation2018; KIO-LAWSON et al., Citation2016). HUANG et al. (Citation2018, p. 4) affirms that “cities in Tanzania are largely growing informally, owing much to the lack of strategic and integrated spatial guidance … . This is further exacerbated by insufficient enforcement of development control … .” The inverse translation is that strategic and integrated spatial guidance through spatial development plans and enforcement of development control is central to guiding and managing the growth of the cities in a planned manner. In the Zimbabwean context, most towns and cities operate without development plans. Thus, urban planning has become more reactionary than a proactive intervention (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE, Citation2020).

This study assesses whether spatial development plans (specifically master and local plans) positively affect spatial development practice in cities, towns, and growth centres in Masvingo province. The essence is to propose policy strategies that can make spatial planning processes responsive to the needs of the ever-growing urban populations. Specific research questions addressed in this paper are: What is the current nature of spatial development in local authorities in Masvingo province? To what extent is the nature of spatial development in the local authorities with operative plans different from those without? What can be done to make spatial development plans positively affect spatial development in the local authorities in Masvingo province? The paper proceeds by covering a brief review of the literature followed by materials and methods utilised in the study.

2. Spatial development planning—a review of literature

Spatial development is usually controlled by development plans that include regional, master, local, and layout plans. However, the focus of this study is on master and local plans. A master plan is “an instrument of coordinating various development activities towards a spatial vision for an area” (MADANIPOUR et al., Citation2018, p. 466). On the other hand, a local plan is regarded as a vision meant to align the goals, policies, and decisions in a municipal area, with an envisaged spatial development outcome (RUDOLF et al., Citation2017). While master plans are long-term and broad in focus, local plans are usually short-term and specific. However, in the subsequent sections, the term “master planning” is loosely used to refer to the adoption of master and local plans as blueprints that guide spatial development.

2.1. Urban governance—a conceptual framework

The terms “governance” and “urban governance” have multiple meanings, and their use in literature is diverse and varied. Generally, governance is a process of making decisions and their implementation (OBENG-ODOOM, Citation2012). Applied to urban services, governance entails service delivery on one hand and civil society’s representation of individuals and groups on the other (HARPHAM & BOATENG, Citation1997). Urban governance applies to the field of spatial planning or the general work of local government. It is defined as the “partnership in urban development between urban local governments and other stakeholders, such as business leaders and landowners” (OBENG-ODOOM, Citation2012, p. 206). Urban governance is essential in spatial planning and development because it encourages coherent and harmonious spatial developments, a well-developed land acquisition, subdivision, consolidation, and distribution system, and taming urban sprawl (BADACH & DYMNICKA, Citation2017; HARPHAM & BOATENG, Citation1997).

Urban governance can improve the quality of life in cities and towns as rapid urbanisation has threatened sustainable urban growth and development (BADACH & DYMNICKA, Citation2017; HARPHAM & BOATENG, Citation1997). However, urban governance can be qualified as either good or bad. Public participation is at the heart of good urban governance, and some of its key indicators are transparency, accountability, and sustainability (BADACH & DYMNICKA, Citation2017; HARPHAM & BOATENG, Citation1997). Participation entails the public having the opportunity to take part in both the provision and production of urban services (HARPHAM & BOATENG, Citation1997).

This study perceives spatial development as an urban governance process since it involves the mediation of diverse interests, rules, and regulations laid down to guide the acquisition and use of urban land. Regional, master, and local plans are the primary tools used by urban governors so that the government can adhere to the envisaged path of spatial development in an urban centre. However, various forces come into play in the interaction of the governors and the governed. These forces include the rigidity of the blueprints, the inability of the governors to timely respond to the needs of the governed (e.g., building land), lack of affordability that causes the governed to fail to adhere to the laid down guidelines and procedures in the development process (DEPARTMENT FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, Citation2006; GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE, Citation2020; HUANG et al., Citation2018). In some cases, political and economic elites neglect the planning guidelines and regulations to achieve their interests (KIO-LAWSON et al., Citation2016). These forces determine the spatial development aftermaths in cities and towns, which can be orderly or disorderly. Therefore, this paper assumes that urban governance (especially urban land governance) is essential for cities’ controlled, harmonious, and orderly development patterns (TUROK, Citation2016).

2.2. The evolution of master planning

Despite their use in town planning for a long time, master plans have remained technical, aligned to economic growth and building intensity, and characterised by the inability to address rapid urban change (MADANIPOUR et al., Citation2018). Often, they failed to accurately project the actual future: population, land requirements, and infrastructure demands, among other urban changes (UN-HABITAT, Citation2009). Yet, master plans remained essential tools for guiding development, especially in countries in the North (MADANIPOUR et al., Citation2018). Master plans continue to contribute to planned development conceptually and operationally, and their impact in regulating and guiding the development of cities and towns is discernable. For example, in Scotland and the United Kingdom, strategic master plans are still valued as positive drivers of spatial growth (COLOMB & TOMANEY, Citation2016; DEPARTMENT FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, Citation2006). At the turn of the 21st century, their nature and focus changed considerably (TODES et al., Citation2010; UN-HABITAT, Citation2009). In countries like Brazil, “new” master planning is being done innovatively to address social inequalities in its cities (Barros et al., Citation2010; Van Wyk, Citation2015). Unlike the traditional master plans, the new master plans in Brazil take a bottom-up approach, are more participatory, aim to counter the effects of land speculation, and are more oriented towards social and spatial justice (UN-HABITAT, Citation2009). Seeking to increase justice has become a fundamental development goal of most 21st-century cities (STILWELL, Citation2017; UN-HABITAT, Citation2009).

Spatial development planning in most African countries is, to a greater extent, an inherited system from former colonial masters and predominantly a bureaucratic function of the state (CHIRISA & DUMBA, Citation2012; KAMETE, Citation2009; MEATON & ALNSOUR, Citation2012; WEKWETE, Citation1989). The historical background of the spatial planning legislation has resulted in urban planning systems that are “eurocentric” that often do not fit into the specific context of African cities (BOLAY, Citation2015; KAMETE, Citation2009; MASHIRI et al., Citation2017). For example, the current town planning system in Zimbabwe owes its origins to the British town planning system despite the difference in the features and functions. NALLATHIGA (Citation2009) notes that the British town planning system uses legal and economic principles and is more decentralised, democratic, and participatory. In contrast, the planning system in Zimbabwe is often accused of being rigid, archaic and prescriptive, making it less responsive to the inevitable challenges confronting its cities (CHIRISA, Citation2014).

2.3. The efficacy of master planning amid rapid urbanisation in Africa

Rapid urbanisation in countries in the South propels the emergent need to manage and improve cities’ economic efficiencies and liveability carefully. United Nations (UN (UNITED NATIONS), Citation2017) recognises that existing planning systems in some cities fail to conform to international sustainable development principles as outlined by The New Urban Agenda [NUA]. The UN (UNITED NATIONS, Citation2017) advances for local authorities to develop and implement urban spatial frameworks and plans to guide the development of integrated and sustainable human settlements. Spatial planning should address historical and contemporary urbanisation challenges facing societies today (CHIRISA & DUMBA, Citation2012; HUANG et al., Citation2018; MASHIRI et al., Citation2017; UN-HABITAT, Citation2009). For example, South Africa adopted integrated development plans and spatial development frameworks as opposed to master plans in the quest to redress historical spatial imbalances; efficient use of space to deliver equitable development; spatial access, inclusivity, and sustainability (MASHIRI et al., Citation2017; WÜST, Citation2022). In Zimbabwe, spatial development tools are rigidly centred on master plans which impede the attainment of spatial efficiency, social inclusion (gender, disability, age, wealth/poverty, etc.), economic density and productivity, environmental stewardship/sustainability, and resilience (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE, Citation2020, p. 22).

Adequate funding, availability of equipment and machinery, public enlightenment, skilled workforce, efficient utilisation of land, and politics determine the success of spatial development (COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH, Citation2005; DEPARTMENT FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, Citation2006; KIO-LAWSON et al., Citation2016; HAMEED & NADEEM, Citation2006). Moreover, spatial planning should be driven by coherent policies, legislation, strategies, and institutions which are more coordinated and participatory, and oriented towards promoting spatial and social justice (COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH, Citation2005; DEPARTMENT FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, Citation2006; HARRISON et al., Citation2008; UN-HABITAT, Citation2009; Van Wyk, Citation2015). However, such significant imperatives are mainly lacking in the context of the countries in the South. Spatial development challenges in the South are seemingly immense in those cities and towns without operative master or local plans as they simply lack a solid framework that anchors their spatial development (HAMEED & NADEEM, Citation2006). However, even in cities and towns with operative plans, spatial development also appears chaotic (KIO-LAWSON et al., Citation2016).

Most cities in the South are spatially fragmented due to rapid urbanisation, highly informalising economies, the perception of the cities as homogeneous entities, and the state’s role in the planning exercise (BALBAO, Citation1993). Accordingly, master planning becomes futile since it is either rigid or too slow to respond to spatial changes that characterise such cities (BALBAO, Citation1993; BOLAY, Citation2015; CHIRISA & DUMBA, Citation2012; HARRISON & CROESE, Citation2022; WÜST, Citation2022). While master plans mainly focus on medium to long-term planning, in most cases, essential decisions in cities in the South need immediate enforcement and simple control (BALBAO, Citation1993). Master planning is associated with high costs and is mainly suitable for formal cities in the North rather than informal cities in the South (BALBAO, Citation1993). Most African cities are characterised by increasing informality (BOLAY, Citation2015; GAMBE, Citation2019; GEYER, Citation2006; MUTAMI & GAMBE, Citation2015). Their urban planning practices favour areas inhabited and invested in by the privileged—those with financial power and connected to actors in the higher echelons of political power (BOLAY, Citation2015).

2.4. Contextualising spatial planning in Zimbabwe

Spatial planning in Zimbabwe dates back to the colonial era. Spatial planning tools like the Town and Country Planning Acts of 1933 and 1945 and the Regional, Town and Country Planning Act of 1976 were enacted to guide and control urban development (CHIGARA et al., Citation2013). The context of the Zimbabwean spatial planning systems, particularly the concept of developing master plans, was derived and modelled from the structure plan concept of the British Town and Country Planning Act of 1968 (WEKWETE, Citation1989). After attaining independence in 1980, Zimbabwe revised the planning act and produced the Regional, Town and Country Planning Act [Chapter 29:12] of 1996. Since then, this has been the primary legislation controlling urban development. Other essential and allied legislation includes the Urban Councils Act [Chapter 29:15], applicable to urban areas and the Rural District Councils Act (Chapter 29:13) to growth points and rural areas.

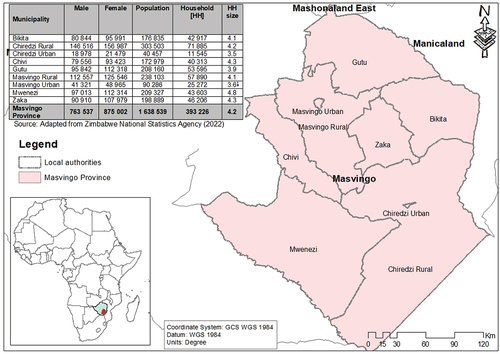

Masvingo province is one of the 10 provinces in Zimbabwe located in the country’s southeast region covering 56,566 square kilometres (ZIMBABWE NATIONAL STATISTICS AGENCY [ZimStat], Citation2012). The province has nine local authorities, namely Bikita Rural District Council, Chiredzi Town Council, Chiredzi Rural District Council, Chivi Rural District Council, Gutu Rural District Council, Masvingo City Council, Masvingo Rural District Council, Mwenezi Rural District Council, and Zaka Rural District Council (Figure ).

The socio-economic profile of Masvingo province and its local authorities is presented in Table . Population distribution across the local authorities is largely rural with a small urban component, except for Masvingo City Council and Chiredzi Town Council. The educational information reveals that a significant proportion of the population lacks tertiary qualifications. Since most local authorities are rural and primarily rely on agricultural activities, most people in the study area work as paid employees while earning less income, just like self-employed (own account) workers. This scenario, coupled with high unemployment rates in Zimbabwe, gives rise to informality. Two groups have emerged in most urban centres: informal residents (mainly the urban poor, resident in unplanned settlements because they do not afford land prices and development costs) and informal traders (undertaking vending activities and small-scale welding, carpentry, motor mechanics, etc. in undesignated places).

Table 1. Socio-economic characteristics of local authorities in Masvingo province

Because the informal residents and traders do not appear on city/town databases, they do not contribute to the local authorities regarding rates and taxes. Masvingo province’s profile indicates a low revenue base, making it difficult for the local authorities to raise revenue for financing the development of master and local plans as prescribed by the legislative policy frameworks.

Household characteristics are also important as they reveal a potential base where municipalities can raise their revenue through rates and taxes. However, most dwelling units across the province are categorised as traditional. Traditional dwelling units are for the poor and are mostly old-style buildings made of cheap materials, including poles, dagga/bricks, and thatching (ZIMBABWE NATIONAL STATISTICS AGENCY [ZimStat], Citation2012). Concerning tenure, most local authorities are rural, characterised by large tracts of private or commercial-owned farmland, communal land, and resettlement areas inhabited by beneficiaries of the fast-track land reform program (MVUMI et al., Citation1998; SCOONES et al., Citation2012). These farmlands are often not charged for any property taxes, a potential revenue base that is not tapped into, as MOFFAT et al. (Citation2017) highlighted. Furthermore, the farmlands have poor access to electricity, piped water, and sanitation services. With these socio-economic issues, it is evident that most local authorities cannot generate revenue to fund spatial development plans. Thus, this study seeks to evaluate the efficacy of master and local plans in the case of Masvingo province in Zimbabwe, given the controversies shrouding master and local plans.

3. Materials and methods

The interpretivist paradigm (see, KIVUNJA & KUYINI, Citation2017; MACK, Citation2010; SCOTLAND, Citation2012) guides this study as the researchers seek to construct meaning from participants’ lived experiences and view phenomena from their perceptions. The study, therefore, assumes an exploratory case study approach and is dominantly qualitative, utilising both primary and secondary data. A qualitative methodology is suitable for this study because it promotes a clear understanding of the meaning individuals and groups attribute to problems (CRESWELL, Citation2014). This study sought the opinions of urban planning experts, building inspectors, land developers, and politicians on the efficacy of spatial development plans to create a narrative of whether the plans are still relevant tools to control development in cities and towns experiencing rapid urbanisation.

Sample selection was designed to include urban planning experts in government, quasi-government and private sectors. The motivation behind this was to capture diverse perceptions emanating from different sectors. In total, 36 participants, shown in Table , were selected. As shown in Table , urban planning experts, building inspectors, land developers, and politicians working in Masvingo province were purposively selected to participate in this study. Only those considered to have adequate knowledge of the urban planning experiences in their areas of jurisdiction were selected. The Department of Spatial Planning (DSP) was selected as the key informant involving officers at the provincial level because it oversees local authorities in terms of their adherence to the provisions of the Regional Town and Country Planning (RTCP) Act [Chapter 29:12] (CHIGARA et al., Citation2013; CHIRISA, Citation2014; WEKWETE, Citation1989).

Table 2. Study participants

The urban planning experts selected from local authorities are those responsible for spatial planning and development control. As such, these had the required knowledge and experience in implementing and enforcing development plans in their areas of jurisdiction. The urban and regional planning lecturers selected from a tertiary institution in Masvingo had over five years of experience teaching and researching urban planning and development issues. Therefore, they were considered to have the necessary knowledge required for the study. Land developers, building inspectors, and politicians were selected as these are active actors in the spatial development process. Their views and experiences were also considered to be valuable.

All participants recruited in this study gave informed consent after the study objectives were fully explained. Consent was obtained verbally, and participation was voluntary. Participants had the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the research process, and the data collected was strictly used for this study. The participants’ names were not included in this paper to protect them from any harm emanating from their participation in this study. The researchers conducted interviews and focused group discussions during the participants’ free time to avoid interfering with their work schedules.

Primary data was collected through in-depth interviews, focused group discussions, and observations, as indicated in Table . The interviews collected data on the town planning experiences and perceptions of the planning experts on the challenges experienced in the process of spatial development and the efficacy of development plans. Two focused group discussions were conducted with urban and regional planning lecturers. The first focused group discussion concentrated on tapping from the participants’ research on topics related to rapid urbanisation and its effects on urban planning and development in Zimbabwe. The follow-up focused group discussion captured the participants’ views on the utility of planning statutes and regulations in spatial development. This focused group discussion took a form of a review of planning statutes, especially the RTCP Act. Apart from that, observations conducted in this study focused on spatial development outcomes. The study observed the nature and form of newly established settlements in towns and cities in Masvingo province, checking whether the settlement patterns conform to town planning statutes and a general inspection of the state and nature of buildings in the settlements. The study also observed the (un)availability of utilities in recent settlements and the existence of water, sewer, and electricity connections.

Secondary data was gathered by reviewing published and unpublished reports and articles. Reports generated in the province concerning spatial development experiences and planning statutes were reviewed, focusing on their strengths and weaknesses in guiding spatial development in Masvingo province and Zimbabwe. The data collected was arranged in similar themes and analysed through thematic and content analyses.

4. Presentation of results

This section presents the study’s major findings. The results were presented in two broad themes to evaluate the efficacy of master and local plans in Masvingo province. These themes are the current nature of spatial development practice in Masvingo’s local authorities and the challenges of spatial development planning the same local authorities face.

4.1. The nature of spatial development practice in local authorities

The study found different classifications of the local authorities depending on whether they have master or local plans. In Category 1 are the local authorities that have never prepared a master or local plan and have been operating without development plans. Category 2 covers local authorities that used to have either a master or local plan, but the plan has since expired; thus are currently operating using expired development plans. Local authorities classified under Category 3 are those with an operational master or local plan.

The study showed that 50% (4 out of 8) of the local authorities are classified in Category 1. The nature of spatial development in these local municipalities is often situational and reactive because of the absence of a broader development framework. The local authorities in Category 1 make use of layout planning. Layout plans show the planned provision of services, facilities, amenities and infrastructure development of a specific site or precinct over time. The planners and councillors in Category 1 local authorities concur that layout planning is cheaper and less complex than master and local plans. They are responsive to pressing community needs and do not require extensive time frames to prepare.

A town planner from one of the local authorities in Category 1 said, “planning is futuristic, and without master and local plans, it is difficult to be proactive in luring investors, curb informality and focus on pursuing a longer-term strategic vision for a local authority”. Thus, the absence of broad planning frameworks hinders investors who may be interested in understanding the overall plan of development of an area before investing in land or property development. Discussions with land developers and private planning consultants also reflect that the low uptake of land development projects in the study areas results from the absence of broad strategic frameworks that guide future development. One of the lecturers engaged in focused group discussions commented that “layout plans have a profound effect on sustainability; their piecemeal approach affects spatial efficiency because its focus is very localised”. This argument demonstrates that layout plans do not fully optimise resources that may be available elsewhere in the region because of their focus on the local context.

Only 25% of the local authorities are in Category 2. Of the local authorities in Category 2, a city council is still utilising a master plan that expired in 2002. A rural development council is dependent on a local development plan that expired in 2006. Although the planners in these urban centres indicated that “statutory plans do not expire like food on a supermarket shelf”, the development plans relied on have certainly outlived their lifespan considering the rapid changes witnessed in the cities and towns in the past decade. However, the study found that the city council utilising a master plan that expired more than a decade ago is in the process of reviewing it.

It emerged from the study that two (25%) rural district councils in Category 1 are working on preparing a joint local development plan. The need to reduce the financial burden associated with the plan preparation process necessitated the collaborative effort. The two local authorities could not afford separate local plans, thus the need to prepare a common one and share the costs. While 25% of the local authorities with operative local development plans fit in Category 3, the study did not find overwhelming evidence that these plans positively influence spatial development in the two centres. The local authorities are experiencing spatial development challenges almost similar to those experienced by those operating without development plans. The study showed that all the local authorities in Masvingo province are failing to cope with the challenges of rapid urbanisation and illegal developments. However, the challenges were worse in local authorities without development plans.

4.2. Challenges of spatial development planning in Masvingo province

All the participants comprehended the importance of development plans as tools that provide a framework for development, coordinate developments, and guide investment. However, different perceptions emerged in explaining the reasons for undertaking spatial development without operative development plans. The town planning experts, lecturers, building inspectors and councillors argued that the Regional Town and Country Planning (RTCP) Act (Chapter 29:12) does not make it mandatory for local authorities to prepare spatial development plans except when the Minister of Local Government, Public Works and National Housing gives a directive. This leaves local authorities with the prerogative to apply strategies that address their local needs. According to the lecturers, in a way, this brings about innovativeness and flexibility, although it has the flipside that complex urban challenges fail to be tackled systematically.

Since the decision to prepare development plans is at the discretion of local authorities, the study noted a general lack of political will by councillors to prioritise the preparation of master and local plans in their budgets. The argument posed by the councillors is that the plans do not yield short-term direct benefits in line with their term of office, and the plans also require a considerable capital outlay. The study also established that some executive managers in some local authorities do not “value” spatial development instruments and therefore lack the motivation to prepare them. According to the town planning experts, this emanates from the fact that the concerned local authorities’ urban and regional planners are not included in the executive management team, so crucial decisions on spatial development are made in their absence. One of the planners said, “the majority of chief executive officers in RDCs believe that engineers can undertake spatial planning and development with the assistance of urban planning technicians. Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem right.” In rural district councils, the urban planning profession is, in most cases, overshadowed by engineering, and planners, therefore, offer little or no input in the spatial development process. Most local authorities in Masvingo marginalise the role of town planning.

Local authorities that intend to prepare master or local plans are frustrated by the complexity of the process, which can take up to a year and a half to complete. Preparing master plans also involves enormous costs in engaging a private consultant to participate in data collection and drawings. The municipalities are financially constrained to initiate the process of master plan preparation, and this is why they operate without development plans. Consequently, illegal and uncoordinated land developments, incompatible land uses, and urban space contestations characterise the local authorities in the province. Two categories of residents, namely the political/economic elites and the urban poor, have emerged as the main contributors to the urban sprawl in urban local authorities in Masvingo province. Discussions with land developers reveal that the urban peripheries have become “war zones” characterised by immense space contestations amidst non-existent social amenities. These areas have also become a haven for illegal land developments, with the politically-backed land barons being the primary culprits. The land barons sell land and line their pockets, then disappear without servicing the created settlements. The participants corroborate that flexible master and local plans can address some of the challenges experienced in Masvingo. However, the participants noted that poor technical expertise, political interference, and uncoordinated efforts are examples of factors inhibiting the development of flexible master plans.

5. Discussion

This section discusses the themes from the findings, namely the spatial growth development in local authorities in Masvingo and the main challenges of spatial development planning in Masvingo.

5.1. Spatial growth and development of local authorities in Masvingo province

This study established that ad hoc layout planning is the order of the day, with local authorities addressing planning problems as they arise. This practice is akin to fire fighting and has become a characteristic of most local authorities in the province operating without a master or local plan. Although this piecemeal layout planning or demand-driven interventions is a common feature in urban centres, this approach has failed to adequately guide the concerned local authorities’ future development. Consequently, this has reduced investment prospects in the local urban centres and negatively affected sustainable growth through spatial inefficiency. As noted by HUANG et al. (Citation2018), the nature of spatial development plans can be changed so that they become a tool to attract and coordinate economic investment. However, the current nature of master and local plans reveals little is being done to ensure that these instruments are used to enhance revenue generation for the local authorities. Spatial efficiency, on the other hand, should provide maximum optimisation of resources and accompanying infrastructure by focusing on the region or the macro rather than the micro-context (MASHIRI et al., Citation2017). However, this is not experienced in the local authorities as the focus on spatial development is not a specific strategic vision but more reactionary.

Some planners have adopted a simplistic view that master plans and other town planning blueprints can address the problems of increasing informality in Zimbabwean cities. Yet, this is easier said than done. Increasing informality is an inevitable outcome of rapid urban population growth, rising unemployment and urban poverty, and a critical shortage of urban infrastructure. These circumstances have pushed the majority of urbanites to assume the role of creating urban spaces for themselves against all odds. Consistent with the findings of BOLAY (Citation2015), when the urban poor take over the mandate to plan, it results in chaotic spatial developments and the violation of urban planning regulations. In such circumstances, conventional spatial development plans cannot efficiently address informality.

5.2. Spatial development planning challenges

The lack of appropriate provisions in the RTCP Act for the sanctioning and implementation of master and local plans denotes poor efficacy and a weak planning system, which does not conform to international sustainable development principles as outlined by the New Urban Agenda [NUA] (UNITED NATIONS, Citation2017). The challenge of lack of development of master plans in most councils has been a persistent pattern over the years dating back to the 1980s, as evidenced by WEKWETE’s (Citation1989) planning practice review studies in Zimbabwe. Although spatial development challenges are common in urban centres in Masvingo regardless of whether they have development plans, the challenges are calamitous in those without, as evidenced by observations of spatial planning outcomes in the various local authorities. The local authorities with development plans have a sense of direction in their spatial development endeavours. However, the adverse effects of rapid urbanisation have compromised the efficacy of the development plans.

Preparing master or local plans is comprehensive, long, and winding hence scaring off many local authorities who want to attempt doing it. Where the plans are developed, the RTCP Act mandates local authorities to constantly examine their environments and identify factors invalidating assumptions that formed the basis of the operative master plan. This process triggers the repeat of the same cumbersome and expensive process to identify alternative proposals towards the alteration, replacement or repeal of such existing development plans. This is partly why most local authorities abandon the idea of preparing development plans and resort to a piecemeal type of planning. Agreeing with this, MADANIPOUR et al. (Citation2018) noted that such long processes hinder planning from swiftly responding to the rapid urban change characterising many cities.

Cognisant of the existence (or non) of development plans, political and economic elites usually disregard the plans in pursuit of their interests, including political expediency and minimising the development period and associated costs. The urban poor usually bargain on strength in numbers to illegally occupy urban open spaces. Due to the lack of resources required to acquire building land, apply for planning permits, and adhere to laid down building codes, the urban poor are forced to circumvent planning regulations and procedures. Cases of the urban poor invading, subdividing municipal land, and allocating each other stands without the municipality’s knowledge are common in Masvingo province and in Zimbabwean cities and towns (CHIRISA & DUMBA, Citation2012). This practice is also common in other African countries like Nigeria and Tanzania (HUANG et al., Citation2018; KIO-LAWSON et al., Citation2016).

Due to illegal land developments, planning agencies are mainly involved in restoring sanity, especially when disaster looms in illegal settlements. The restoration consists of regularising the settlements and includes installation of municipal services, orderly arrangement of dwellings, and planning to provide community facilities such as schools and clinics. However, urban centres with expired development plans had fewer challenges than those that never prepared one. As previously highlighted, those with expired development plans still have a point of reference regarding their spatial planning and development framework, unlike urban centres that never prepared development plans. In most cases, they lack a solid spatial planning and development framework to guide their development practice. Although piecemeal planning is responsive to rapid urban changes, it lacks a futuristic aspect critical for proactive planning.

6. Conclusions and recommendations

Most local authorities in Masvingo province operate without master or local plans. Reasons behind this abound. The plan preparation process is long and complex. Local authorities are reluctant to prioritise the preparation of master and local plans in their budgets because the plans do not yield short-term direct benefits. In addition, the costs associated with the plan preparation process are beyond the financial capacity of most local authorities. The economic malaise currently obtaining in Zimbabwe aggravates the situation, making it difficult for most local authorities to raise the financial resources needed to prepare development plans. Notwithstanding this, rapid urbanisation has rendered these tools less effective, especially in cities and towns in African countries like Zimbabwe. In Masvingo province, the efficacy of local plans remains debatable: local authorities with operative development plans and those without are facing similar challenges that include the mushrooming of unplanned/illegal settlements, uncontrollable urban sprawl, and increasing informal economic activities. Therefore, the spatial development differences between the former and the latter are difficult to discern.

This paper argues that for spatial development plans to remain relevant in guiding spatial development, they should align with the informal and fragmented nature of the rapidly urbanising African cities, like those in Masvingo province. The paper, therefore, proposes recommendations at various scales of planning. The planning standards, specifically spatial development tools required (master and local plans), are too high to be sustained by cities and towns in a struggling low-income country like Zimbabwe. As such, the paper recommends fast-paced action in the process that has already begun of revising planning regulations and standards, starting with the RTCP Act—the main instrument that guides planning in Zimbabwe. The Act and town planning standards should be flexible in terms of zoning that is cognisant of the high informality that has dominated cities and towns in the country. A typical example is the forward planning approach through spatial development frameworks practised in neighbouring South Africa (City of Ekurhuleni). In its spatial development framework, Ekurhuleni proposes flexible zoning that responds to and accommodates primary economic activities emanating from current growth pressures instead of prescribing rigid and unresponsive land use plans (City of EKURHULENI, Citation2015). Mixed developments are permissible in residential areas, and residents can apply for a permit to operate backyard industries. This is something not permissible in residential areas in the study area. Apart from that, there are chances that if the nature or form of master and local plans is refocused through the revision of the RTCP Act, then the preparation process can become less cumbersome, and the preparation cost drops. Consequently, some small local authorities may afford the plan preparation process.

There is a need for spatial development plans to acknowledge both formal and informal micro small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that characterise cities and towns in Zimbabwe and devise ways of making city economies benefit from these firms. Some way of achieving this is for local authorities and MSMEs owners to co-produce and co-manage trading spaces and the regulatory frameworks so that both stakeholders experience gains and benefit the local economy. Regularising informal enterprises in cities and towns helps improve local authorities’ revenue base through rates and taxes. Besides, allocating or setting aside working space for MSMEs addresses one of their major growth inhibitors, which is convenient and conducive working space. Given the required working space and other forms of support, MSMEs can positively contribute to urban economies through backward and forward linkages with large enterprises and contribute towards reducing high unemployment levels.

The paper also recommends the need for local authorities to be proactive in the preparation of “marketable” and flexible spatial development plans. Master and local plans that promote investment should have provisions that expedite the processing of development permits because unnecessary long-time frames scare away potential investors. This is the norm in the current planning practice and has negatively affected economic development in many localities. Development plans should envisage numerous business opportunities and associated regulations that can be exploited in an area. This enables local authorities to respond to the needs of investors promptly. For example, Masvingo province boasts of the Great Zimbabwe Ruins, a world heritage site. There is a need to integrate cultural heritage and spatial development to make Masvingo province a unique cultural-heritage brand that is marketable internationally.

Local authorities in Masvingo should adopt spatial plans whose approach is bottom-up, more participatory, oriented towards social justice, and aims to counter the effects of land speculation. A more “responsive and proactive approach” involves all stakeholders, including the urban poor, who are usually excluded in urban governance. Currently, represented participation (councillors representing their constituencies in local authorities’ development meetings) is common. Yet, in most cases, this type of public participation is inadequate. New strategies to encourage residents to participate directly in the planning process are required, for example, allowing residents to vote for or against some planning decisions through an online easy-to-use platform created for that purpose. However, this may not be possible when urgent decisions have to be made. In such cases, councillors and a small committee (representing a particular community) can participate representing residents. A “responsive and proactive” approach also includes the optimum use of local and regional resources to ensure spatial efficiency and embrace a society’s cultural norms and values.

Rather than abandoning master and local plans altogether, the local authorities in Masvingo can contextualise these planning frameworks so that they directly serve the purpose for which they are created and are responsive to the unique demands and needs of the community. Consequently, there is a need to move away from “one size fits all” master or local plans and introduce context-specific development plans that significantly vary in regulations from one city to the other. For example, Masvingo province is endowed with two largest inland dams in the country, namely Lake Mutirikwi and Tugwi- Mukosi. The spatial development plans for the local authorities in Masvingo province should reflect how local communities can benefit from such enormous resources, for example, in agriculture, fisheries and tourism. Local authorities with expired plans are encouraged to review them. Reviewing an existing plan is cheaper than funding the preparation of the plans for the first time. Small local authorities are encouraged to consider the concerted effort in preparing plans that cut across their areas of jurisdiction. This collaborative effort can lessen the financial burden encountered if the exercise is undertaken separately.

Often, the blueprint nature and the cost of preparing spatial development plans have discouraged local authorities with intentions to prepare such plans and triggered the need to question their efficacy. Even for local authorities with operative master and local plans: the disregard of these plans by political and economic elites and the urban poor shows that the plans have, in most cases, become inhibitors of development in a rapidly urbanising world. However, if local authorities in Masvingo province treat master and local plans as important investment plans unique to each place, in that case, they can be relevant tools to guide positive spatial development.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the insights and contributions by Pheobe Nyika, Francis Ndhlovu, and Chipo Mutonhodza in an earlier draft presented at the Zimbabwe Institute of Regional and Urban Planners (ZIRUP) Annual School that was held at Troutbeck Resort, Nyanga, Zimbabwe from 28 to 31 August 2018. Special thanks to Mr Ndhlovu, who attended the conference and presented the paper on behalf of the team.

Disclosure statement

We have no interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tazviona Richman Gambe

Tazviona Richman Gambe has a background in urban and regional planning and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of the Free State. His research interests include urbanisation trends and patterns, regional economic resilience, and urban water supply.

Wendy Wadzanayi Tsoriyo

Wendy Wadzanayi Tsoriyo is a specialist in urban and regional planning. Her research interests are spatial justice, participatory planning, and urban design and management.

Frank Moffat

Moffat Frank has research interests in spatial planning, spatial transformation, human settlements, town-gown partnerships, housing, policy analysis, revenue enhancement, and GIS application in planning.

The authors regularly undertake collaborative research focusing on urban planning and development practice, inclusive cities, and spatial justice. The current paper, which assesses the efficacy of master and local plans, is one of the collaborations focusing on urban planning and development practices in Zimbabwe. This paper is related to the authors’ other collaborative projects on informality, inclusivity, and spatial justice in African cities.

Notes

1. Other dwelling unit types (mixed, detached, semi-detached, flat/townhouse, shack, other and missing)

2. Other household tenure types (tenant, lodger, tied accommodation, missing)

3. Other main sources of water (communal tap, well/borehole protected, well-unprotected, river/stream/dam, missing)

4. Other types of sanitation facilities (Blair, pit, communal, none/missing)

References

- BADACH, J., & DYMNICKA, M. (2017). Concept of good urban governance. IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering, 245(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/245/8/082017

- BALBAO, M. (1993). Urban planning and the fragmented city of developing countries. Third World Planning Review, 15(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.3828/twpr.15.1.r4211671042614mr

- BARROS, F. B., Maria, A., Barbosa, B. R., Carvalho, C. S., Montandon, D. T., Maricato, E., Rodrigues, E., Bassul, J. R., Mario, R., Fernandes, E., & ALLI, S. (2010). The City Statute of Brazil: A commentary (English). World Bank Group.

- BOLAY, J. C. (2015). Urban planning in Africa: Which alternative for poor cities? The case of Koudougou in Burkina Faso. Current Urban Studies, 3(4), 413–431. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/cus.2015.34033

- CHIGARA, B., MAGWARO-NDIWENI, L., Mudzengerere, F. H., & Ncube, A. B. (2013). An analysis of the effects of piecemeal planning on development of small urban centres in Zimbabwe: Case study of Plumtree. International Journal of Management and Social Sciences Research, 2(4), 139–148. https://jsd-africa.com/Jsda/Vol15No2-Spring2013B/PDF/An%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Effects%20of%20Piecemeal%20Planning.Benviolent%20Chigara.pdf

- CHIRISA, I. (2014). Building and urban planning in Zimbabwe with special reference to Harare: Putting needs, costs and sustainability in focus. Consilience: The Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(1), 1–26. https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/consilience/article/view/4652/2089

- CHIRISA, I., & DUMBA, S. (2012). Spatial planning, legislation and the historical and contemporary challenges in Zimbabwe: A conjectural approach. Journal of African Studies and Development, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5897/JASD11.027

- COLOMB, C., & TOMANEY, J. (2016). Territorial politics, devolution and spatial planning in the UK: Results, prospects, lessons. Planning Practice & Research, 31(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2015.1081337

- COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH. (2005). Guidelines for Human Settlements Planning and Design.

- CRESWELL, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th) ed.). Sage.

- DEPARTMENT FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT. (2006). The Role and Scope of Spatial Planning Literature Review Spatial Plans in Practice: Supporting the Reform of Spatial Planning. Communities and Local Government Publications.

- DODMAN, D., Leck, H., Rusca, M., & Colenbrander, S. (2017). African urbanisation and urbanism: Implications for risk accumulation and reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 26(July), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.06.029

- EKURHULENI, C. I. T. Y. O. F. (2015). Region C: Regional Spatial Development Framework. City of Ekurhuleni. Resolution number: A-CPED (04-2015).

- GAMBE, T. R. (2019). Rethinking city economic resilience: Exploring deglomeration of firms in inner-city Harare. Resilience, 7(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2018.1534333

- GEYER, H. S. (2006). Introduction: The changing global economic landscape. In H. S. Geyer (Ed.), Global regionalization: Core periphery trends (pp. 3–38). Edward Elgar.

- GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE. (2020). Zimbabwe National Human Settlement Policy. Government Publishers.

- GÜNERALP, B. , Lwasar, S., Masundire, H., Parnell, S., & Seto, K. C. (2017). Urbanization in Africa : Challenges and opportunities for conservation. Environmental Research Letters, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa94fe

- HAMEED, R., & NADEEM, O. (2006). Challenges of implementing urban master Plans: The Lahore experience. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 24(2006), 101–108. https://web.archive.org/web/20201230035224/https://zenodo.org/record/1076910/files/11234.pdf

- HARPHAM, T., & BOATENG, K. A. (1997). Urban governance in relation to the operation of urban services in developing countries. Habitat International, 21(1), 65–77. http://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-3975(96)00046-x

- HARRISON, P., & CROESE, S. (2022). The persistence and rise of master planning in urban Africa: Transnational circuits and local ambitions. Planning Perspectives, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2022.2053880

- HARRISON, P., TODES, A., & Watson, V. (2008). Planning and Transformation. Lessons from the South African Experience. Routledge.

- HEINRIGS, P. (2020). Africapolis: Understanding the dynamics of urbanization in Africa. [Field Actions Science Report, 2020(22), 18–23. http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/6233

- HUANG, C., Ally Namangaya, A., Lugakingira, M. W., & Cantada, I. D. (2018). Translating Plans to Development: Impact and Effectiveness of Urban Planning in Tanzania Secondary Cities. World Bank.

- JIANG, S., ZHANG, Z., REN, H., Wei, G., XU, M., & B, L. I. U. (2021). Spatiotemporal characteristics of urban land expansion and population growth in Africa from 2001 to 2019: Evidence from population density data. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(9), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10090584

- KAMETE, A. Y. (2009). Hanging out with “trouble-causers”: Planning and governance in urban Zimbabwe. Planning Theory & Practice, 10(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350802661675

- KIO-LAWSON, D., Marcus, D., Baris Dekor, J., & Eebee, A. L. (2016). The challenge of development control in Nigerian capital cities: A case of some selected cities in the Niger Delta. Developing Country Studies, 6(2), 149–156. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234682733.pdf

- KIVUNJA, C., & KUYINI, A. B. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(5), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26

- MABASO, A., Shekede, M. D., CHIRISA, I., Zanamwe, L., Gwitira, I., & Bandauko, E. (2015). Urban physical development and master planning in Zimbabwe: An assessment of conformance in the City of Mutare. Journal for Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(1), 72–88. https://repository.unam.edu.na/handle/11070/1556?show=full

- MACK, L. (2010). The philosophical underpinnings of educational research. Polyglossia, 19, 5–11. https://en.apu.ac.jp/rcaps/uploads/fckeditor/publications/polyglossia/Polyglossia_V19_Lindsay.pdf

- MADANIPOUR, A., Miciukiewicz, K., & Vigar, G. (2018). Master plans and urban change: The case of Sheffield city centre. Journal of Urban Design, 23(4), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1435996

- MASHIRI, M., NJENGA, P., NJENGA, C., Chakwizira, J., & Friedrich, M. (2017). Towards a Framework for Measuring Spatial Planning Outcomes in South Africa. Sociology and Anthropology, 5(2), 146–168. https://doi.org/10.13189/sa.2017.050205

- MAWENDA, J., Watanabe, T., & Avtar, R. (2020). An analysis of urban land use/land cover changes in Blantyre City, Southern Malawi (1994-2018). Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062377

- MEATON, J., & ALNSOUR, J. (2012). Spatial and environmental planning challenges in Amman, Jordan. Planning Practice and Research, 27(3), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.673321

- MOFFAT, F., Bikam, P., & Anyumba, G. (2017). Exploring revenue enhancement strategies in rural municipalities: A case of Mutale Municipality. CIGFARO Journal (Chartered Institute of Government Finance Audit and Risk Officers), 17(4), 20–25. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Frank-Moffat/publication/353348607_Exploring_Revenue_Enhancement_Strategies_in_Rural_Municipalities_A_Case_of_Mutale_Municipality/links/60f6ea3c0859317dbdf8c938/Exploring-Revenue-Enhancement-Strategies-in-Rural-Municipalities-A-Case-of-Mutale-Municipality.pdf

- MUTAMI, C., & GAMBE, T. R. (2015). Street multi-functionality and city order: The case of street vendors in Harare. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 6(14), 124–129. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEDS/article/view/24433

- MVUMI, B., Donaldson, T., & Mhunduru, J. (1998). Crop post-harvest research programme Zimbabwe: A report on baseline data available for Chivi District, Masvingo Province. Project, A0549, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d9ced915d3cfd001b16/R6674g.pdf

- NALLATHIGA, R. (2009). From master plan to vision plan: The changing role of plans and plan making in city development (with reference to Mumbai). Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 4(13), 141–157. https://um.ase.ro/No13/9.pdf

- OBENG-ODOOM, F. (2012). On the origin, meaning, and evaluation of urban governance. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 66(4), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2012.707989

- RUDOLF, S. C., Grădinaru, S. R., & Hersperger, A. M. (2017). Impact of planning mandates on local plans: A multi-method assessment. European Planning Studies, 25(12), 2192–2211. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1353592

- SCOONES, I., Marongwe, N., Mavedzenge, B., Murimbarimba, F., Mahenehene, Mahenene, C., & MAHENEHENE, J. (2012). Livelihoods after land reform in Zimbabwe: Understanding process of rural differentiation. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2012.00358.x

- SCOTLAND, J. (2012). Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: Relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the Scientific, Interpretive, and Critical Research Paradigms. English Language Teaching, 5 (9), 9–16. Accessed: 21 February 2019 https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1080001.pdf

- STILWELL, F. (2017). Social justice and the city. Regional Studies, 51(10), 1595–1598. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1355517

- TODES, A., Karam, A., Klug, N., & Malaza, N. (2010). Beyond master planning? New approaches to spatial planning in Ekurhuleni, South Africa. Habitat International, 34, 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.11.012

- TUROK, I. (2016). Getting urbanization to work in Africa: The role of the urban land-infrastructure-finance nexus. Area Development and Policy, 1(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2016.1166444

- UN-HABITAT. 2009. Planning Sustainable Cities. Global Report on Human Settlements 2009. Earthscan.

- UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR AFRICA. 2017. Economic Report on Africa 2017: Urbanization and Industrialization for Africa’s Transformation. United Nations.

- UN (UNITED NATIONS). (2017). New urban Agenda. A/RES/71/256. In United Nations: Habitat III Secretariat (pp. 1-29). United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_71_256.pdf

- Van Wyk, J. (2015). Can legislative intervention achieves spatial justice? The Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa, 48(3), 381–400. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26203991.

- WEKWETE, K. (1989). Planning laws for urban and regional planning in Zimbabwe – A review. In RUP Occasional Paper No (Vol. 20, pp. 1-22). University of Zimbabwe.

- WÜST, F. (2022). The South African IDP and SDF contextualised in relation to global conceptions of forward planning – A review. Town and Regional Planning, 80(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.18820/2415-0495/trp80i1.6

- ZHANG, X. Q. (2016). The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat International, 54(13), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.018

- ZIMBABWE NATIONAL STATISTIC AGENCY [ZimStat]. 2012. Census 2012: Provincial report Masvingo. ZimStat

- ZIMBABWE NATIONAL STATISTICS AGENCY [ZimStat]. 2022. 2022 Population and housing census: Preliminary report on population figures. ZimStat