Abstract

Comparatively little attention has been given to a contemporary examination on the gender disparities in publishing within the Communication field. The major goal of the research was to examine female scholars’ publishing performance and determine whether gender disparity exists in the publication rate of each gender. This study utilized bibliometric methods to conduct a gendered analysis of the publication rates among female and male lead authors in the top five Chinese Journalism and Communication journals from 2011 to 2020. The results confirmed the presence of consistent gender differences in the percentage of articles published by female and male authors. Data analysis also revealed an ongoing tendency towards decline due to female’s increasing educational background, improved academic collaboration and intensified government interventions. The findings of this study contribute to a better understanding of the current status of female scholars and may be used to promote discussion and actions related to gender and equity.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Gender disparity has affected all facets of life and the under-representation of women in academia presents no exception. The present paper aims to examine female scholars’ publishing performance and determine whether gender disparity exists in the publication rate of each gender. This study utilized bibliometric methods to conduct a gendered analysis of the publication rates among female and male lead authors in the top five Chinese Journalism and Communication journals from 2011 to 2020. The results revealed that there is a consistent disparity in the authorship, which favored male. In particular, male occupied the absolute major percentage of the most prolific authors. Besides the generally better performance of men, data analysis also identified that such inequality has narrowed slowly and with fluctuations. The findings of this study contribute to a better understanding of the current status of female scholars and may be used to promote discussion and actions related to gender and equity.

1. Introduction

Gender disparity (Kooli & Muftah, Citation2020) has affected all facets of life and the academia presents no exception. The past decades have witnessed a common topic of gendered analysis of female academics. Prior studies in the 20th century revealed that female scholars were generally treated differently and they were classified as token (Kanter, Citation1977), outsider (Zuckerman et al., Citation1991), stranger (Sonnert & Holton, Citation1995, p. 187), and illegitimate members (Burt, Citation1998). More recent studies also documented that, even though women are increasingly entering the academia (Elsevier Editors, Citation2017), they are lagging behind their male colleagues in terms of the academic visibility (Stupnisky et al., Citation2019). Fewer women can break through the glass ceiling of the academic hierarchy and enter senior leadership positions (Aiston & Fo, Citation2020; Aiston & Jung, Citation2015). Female researchers in various disciplines are significantly under-represented, with only 27% of the whole publication rate (Huang et al., Citation2020). Female-led papers are more likely to be rejected, and less likely to be cited (Schiermeier, Citation2019). What’s more, female-majority teams invent a significantly smaller number of patents compared with male-majority teams (Koning et al., Citation2021). They also speak less at academic conferences or grand rounds (Boiko et al., Citation2017), receive fewer prestigious recognition awards (Wenzel et al., Citation2021) and produce less academic entrepreneurship (Meng, Citation2016).

Research productivity is highly prized (Aiston & Jung, Citation2015; Zidi et al., Citation2022) due to its essential role in the success of a scientific career (Fox & Stephan, Citation2001), one of whose barometer is the quantification of their scholastic activity as represented by “authorship” in scientific publications (Bendels et al., Citation2017; Jagsi et al., Citation2006). The productivity puzzle (Cole & Zuckerman, Citation1984) of female scientists have aroused discussions. Some empirical investigations have been undertaken to display the lower publishing rate in academic areas, such as ecology (Symonds et al., Citation2006), social psychology (Cikara et al., Citation2012), medical study (Filardo et al., Citation2016), pediatric surgery (Marrone et al., Citation2020) and educational technology (Scharber et al., Citation2019). More studies concentrated on discovering how and why the accusations of female scholars’ low productivity (Mousa, Citation2021) is both prevailing and complex. Scholars attribute it to the organizational culture and structures of the academy that perpetuate and privilege masculine practices and norms (Tinkler et al., Citation2015). They maintain that, due to structurally discriminatory issues against women in academia (Savigny, Citation2014), gender stereotype influences the roles that female academic perform in publication who usually assume a heavier load of administrative work and low-level pastoral care in male-dominated academia (Hayhoe, Citation1996). Moreover, female scholars’ research agendas are less innovative and risk-taking, which also leads to their lower visible productivity (Santos et al., Citation2020). Literature also have consistently documented barriers female academics face in work-life balance (WLB) challenges, for example, the tension between career and family care, the common dilemma of work load and motherhood obligations and etc. (Kooli, Citation2022; Ren & Caudle, Citation2020; Whittington, Citation2011).

The subject matter of female scholars’ lower academic productivity is relevant to all countries, given that around the world females have been described as handling with a variety of barriers different from their male counterparts (Marrone et al., Citation2020; Morley, Citation2014; Mousa, Citation2021; Ruan, Citation2020). Follow on to the groundbreaking 2015 report Mapping Gender in the German Research Arena, Elsevier released comprehensive reports through gender lens to cover the disparities of different regions of the world in 2017, 2020, and 2021 respectively, claiming that female academics, on average, publish fewer research papers than men (Elsevier Editors, Citation2017). Although mostly focused on European (Abramo et al., Citation2009; Baccini et al., Citation2014), American countries (Samble, Citation2008; Schiermeier, Citation2019; Tsui, Citation1999), African (Mousa, Citation2021) and East Asian countries (Appleby, Citation2014), the idea that female academics face similar under-representation in their career pursuits in China should of course not come as a major surprise (Peng, Citation2020; Rhoads & Gu, Citation2012). As a country deeply influenced by Confucianism and institutionalized patriarchy, China has experienced the social upsurge of feminism in the past decades. Such historical and cultural impacts make the institutionalized landscape of female academic lives more complicated (Tang & Horta, Citation2021). Meanwhile, the country also has advocated for greater equality between men and women, including in academia (Gaskell et al., Citation2004). The Chinese government has promulgated various policies to promote fair participation of female scholars in academic research and improve their academic output. Recently, on 19 July 2021, the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology and the All-China Women’s Federation, as well as other 11 Ministries and Commissions, launched a series of measures to support female researchers in playing a greater role in sci-tech innovation, which emphasizes that female scholars enjoy the privilege to grants and other professional resources under the same conditions. These events reminded us the importance of exploring China might be an interesting case. To explore Chinese local publication rate of female scholars might contribute to a wider and more diversified global dialogue about women’s lives in academia.

Derived in the above mentioned broader social context and our personal experiences as female researchers in the field of Journalism and Communication, we are interested in the academic performance of women as scholars in our field. Journalism and communication is a typical sample of society-orientated departments (Heijstra et al., Citation2013), where male academics are predominantly located in such research-oriented areas as natural sciences. Within the Communication field, there have been a list of analysis of publication trend. The research productivity was examined in different separate time span, an analysis of 1915–1995 (Hickson et al., Citation1999), 1996–2001 (Hickson et al., Citation2003) and a replication of 1915–2001 (Hickson et al., Citation2004) respectively. Atkin et al. (Citation2020) profiled scholarly productivity across the Journalism and Communication’s first century, focusing on scholarly output in referred journals from 1915 to date. Studies were also conducted to ascertain who the most prolific scholars in Communication studies were in a five-year span (Bolkan et al., Citation2012; Griffin et al., Citation2017). Based on the citation data, Griffin et al. (Citation2016) utilized network analysis to determine the central authors of Communication journals during the years 2007–2011. However, the above studies did not take gender factor into consideration. The present study is not without precedent. More than two decades ago, Hickson et al. (Citation1992) identified the top 25 active prolific female scholars in Communication field. Pledger and Standerfer (Citation1997) ever held an examination to determine whether women and men published at equal rates in the leading journals of the National Communication Association (NCA). These two studies focused on the academic productivity in the Communication field through gender lens. However, a contemporary examination on the gender disparities in publishing within this academic community has been mostly overlooked to date.

This study helps to fill in the gap. The aim of this descriptive study is to provide the most recent journal data and to examine the publication rates of female and male faculty at universities within top Chinese Journalism and Communication journals from 2011 to 2020. More specifically, we examine the publication rates of matched samples of female and male in order to determine the following research questions:

(1) Overall, whether there are gender disparities of the data across the selected journals in rates of publication as single-authors and first-authors and, if so, of what magnitude?

(2) How about the gender difference in publication rates of each of the five selected journals?

(3) Of the top prolific authors, what is the gender disparity between female and male?

(4) If such differences are observed, how do they grow or diminish from 2011 to 2020?

2. Methodology

To better understand the role of bias in the outcomes in scholarly publishing, we utilized a bibliometric approach to assess the extent to which gender disparities manifest in top Chinese Journalism and Communication journals. Bibliometrics has long been recognized as a statistical and mathematical approach for the quantitative investigation of the performances of journals, institutes and authors, as well as mapping the characteristics of academic community or research topics (Paisley, Citation1989; Quoc Bui et al., Citation2021). It has traditionally been used as a powerful research method in information science and recently social science fields are applying it as well, including gender studies and Communication (Kataria et al., Citation2021; Keating et al., Citation2022; Lee & Sohn, Citation2016; Ruggieri et al., Citation2021). In this research, we particularly conducted a statistical investigation to study the extent to which the magnitude of these disparities vary across different gender of scholarly publication rates in the past decade, which has been overlooked to date.

2.1. Data sources

There are no standardized journal selection methods for bibliometric studies. In previous studies, the Index to Journals in Communication Studies was used as the database (Bolkan et al., Citation2012; Hickson et al., Citation1992). Ha and Pratt (Citation2000) referred to the publications indexed by the Chinese Communication Association (CCA). Su et al. (Citation2012) maintained that Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) is the most important academic platform for the research fruits of Chinese humanities and social sciences scholars. Liao et al. (Citation2019) selected 9 Chinese Journalism and Communication journals from the CSSCI database and built the knowledge map. Although Chinese researchers opt to publish in international journals, after examining the reliable resource of scientific citation database, Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), of all the highest-ranking 23 English journals (belonging to Q1) in Journalism and Communication spanning the years 2011–2020, only 123 valid papers are located. Considering the small quantity, we did not include them into our data set.

Thus, in order to identify the gender disparities in academic performance of Chinese female and male scholars in the Communication field, we examined all the 17 Chinese journals in the field of Journalism and Communication (CSSCI 2021–2022), including reports on journal quality and impact factors as well as the columns that each journal contains. Five flagship research-oriented journals with the highest impact factors are included in the data set:

Journalism & Communication (JC) sponsored by the Media Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Compound Impact Factor: 4.179 in 2021;

Chinese Journal of Journalism & Communication (CJJC) sponsored by Renmin University of China, the Compound Impact Factor: 3.97 in 2021;

Shanghai Journalism Review (SJR) sponsored by Shanghai United Media Group and the Media Research Institute of Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, the Compound Impact Factor: 3.04 in 2021;

Journalism Research (JR) sponsored by Fudan University, the Compound Impact Factor: 2.623 in 2021; and

Modern Communication (MC) sponsored by Communication University of China, the Compound Impact Factor: 2.443 in 2021.

We selected articles published by the five journals over a 10-year time span extending from 2011 to 2020. We chose the year 2011 as the starting year because the Chinese government issued Program for the Development of Chinese Women (2011–2020) in 2011, explicitly proposing to improve conditions for women’s participation in scientific research (The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, 2011). In the following years, the statistical departments submitted annual reports to ensure the smooth implementation of this policy. It is a landmark document for the professional advancement of women scholars. This decade represents both a time of accelerated growth in the field of Journalism and Communication education and increased awareness of gender inequity in Chinese academia.

2.2. Data collection

All the articles published in every issue of each journal from 2011 to 2020 were accessed via university library’s online databases. In the first phase of data retrieval, all the published articles were downloaded containing a list of variables, including the title, author, institutional affiliation, source, keyword, summary, period, volume, year, and pagecount. In the second phase, all the entries were carefully read to determine which should be excluded from the data set. Only research articles written by Chinese academics at Chinese universities were counted. Consequently, book reviews, book recommendations, conference summaries, academic interviews, and editorials were all cleaned out. Any article authored by foreign nationality, foreign organ, or other secondary vocational schools was excluded from the data set. Another key indicator is the article length, which led to the exclusion of articles with less than three full pages, since they would be deemed as invaluable or count out toward academic promotion (Morley, Citation2014). This process reduced the initial sample of 11,808 entries to 7,519.

2.3. Gender assignment

Although gender can be described as a gradient (Zaza et al., Citation2021), for the purpose of our research, in the next phase, authors were only divided by binary gender definitions, that is, authorship for each article was coded into female/male single-author and female/male first-author, the same approach applied by Scharber et al. (Citation2019). A total of 2,871 authors were identified. Among them, 82.79% of their genders were identified through their online introduction listed on each university’s official website. 14.18% were confirmed with the author’s biography that accompanied the journal article or their other publications. To 2.61% of authors, because their personal information was not provided officially, we turned to other search strategies like examination of verified social media accounts (such as Sina Weibo) for references. To the rest 0.42%, we made phone calls to their school offices or contacted themselves directly, stated our research purpose and identified their genders. In order to maintain the validity and the integrity, five undefined authors and their authorships were not taken into consideration. After this step, our search tallied these determined authors’ papers, yielded a total of the final 7,514 authorships and stored in the Excel data structure. All their gender information were cross-checked by our research team.

2.4. Data processing

When all the necessary data has been prepared, the next step is to explore and visualize the data so that the information contained can be presented in a graphical format. For its strong compatibility, Python is an excellent steering language for a data analysis and visualization (Oliphant, Citation2007). Therefore, in addition to the bibliometric analysis, our data process also applied Python language in PYCHARM tool to complete the preliminary data visualization and improve the data legibility. In the step of data import, it is realized by pd.read_excel () to import the Excel data into the database PyEcharts. The specified data set was saved into a unique data structure with different row and column index, making it convenient for data display and processing. Then, based on our research purpose and the characteristics of the data, the indicators obtained from the data analysis was inserted into the graph, and the code from pyecharts import Effectpie was run to visualize the presentation. The Page function was operated to integrate all the 10 charts on the same page. In the end, the drag-and-drop function was applied to design its layout, then was completed.

3. Results

A composition of the total number of articles were analyzed by gender as well as single- and first-authorship. The statistical analysis revealed that in the total sum of 7,514 articles examined from all the five journals collectively during 2011–2020, female scholars lag far behind their male counterparts in terms of publication rates, that female single-authors contributed 19% (1,452 articles) of the total articles, female first-authors 17% (1,286 articles), male single-authors 35% (2,611 articles), and male first-authors 29% (2,165 articles) respectively. It shows the number of articles led by male scholars accounts for 64% of the total number of articles across the five journals within the 10-year span.

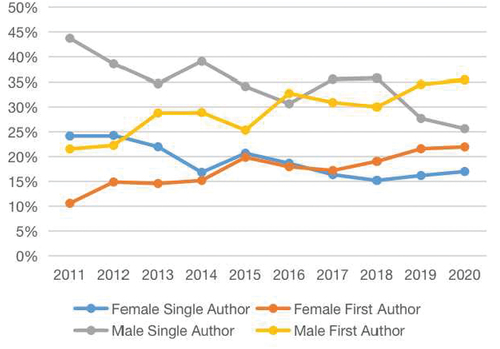

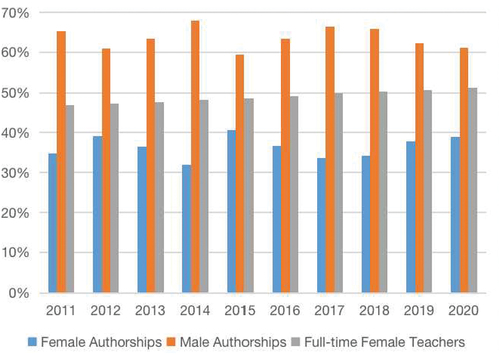

Further statistical analysis was conducted to ascertain the yearly publication rates of male and female authors. Of the 7,514 valid entries, a total of 1,521 universities were identified, covering the key samples throughout China. Therefore, we compared the publication rates with the yearly percentage of full-time female teachers released by Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China from 2011 to 2020. As illustrates, during the 10-year span the percentage of full-time female teachers in Chinese high education institutions was climbing steadily, occupying the proportion at around 50%. By comparing this number with the yearly percentage of female and the male-authored articles across the five journal within the 10-year span, it is found that, although the numbers fluctuate, the publishing rate of female authors occupies less than 50%, and is substantially lower than that of males.

Figure 1. Gender differences in the percentage of female- and male-authored articles published across five journals and the full-time female teachers (2011 to 2020).

The above results provide answers to research Question 1 whether there are gender disparities of the data across journals in rates of publication as single-authors and first-authors and, if so, of what magnitude. The findings consistently prove that female scholars have devoted lower publication rates than their male counterparts.

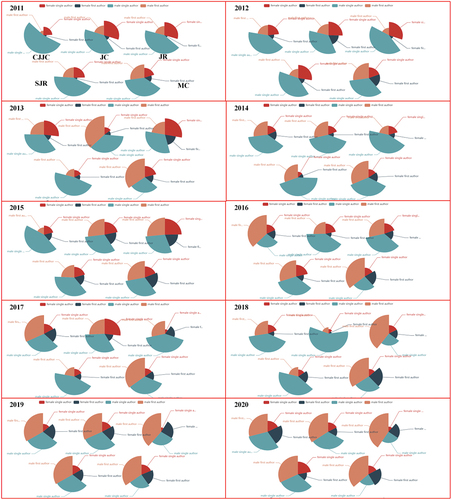

seeks to answer Question 2, how is the gender disparity in publication rate within each selected journal in each year. It examines the gender percentage of female/male single-authors and female/male first-authors. Each journal is discussed by year respectively:

Figure 2. Gender differences in publication rates of each journal (2011- 2020).

3.1. Chinese Journal of Journalism & Communication (CJJC)

Analysis of 1,344 eligible publications from CJJC during 2011–2020 showed that 21% (282 articles) of articles were written by female single-authors, 15% (205 articles) by female first-authors and 39% (523 articles) by male single-authors, 25% (334 articles) by male first-authors. Furthered yearly analysis revealed that, even though during the 10 years the total number of publication within CJJC was decreasing due to the journal’s policy adjustment, in general, female scholars published less than their male counterparts. The analysis of yearly trends showed that, except in 2015, there was a disparity between the percentage of female first-authors and males. The proportion of female single-authors is always considerably smaller than that of males throughout the ten-year time period.

3.2. Journalism & Communication (JC)

Eight hundred and seventy-eight eligible publications from JC during the 10-year span 2011–2020 were examined, of which 303 were written by female first- or single-authors. As it illustrated, 21% (178 articles) of the articles were written by female single-authors and 14% (125 articles) were by female first-authors. Male scholars occupied the larger proportion of the articles whether by single- or first-authored, as 38% (336 articles) and 27% (239 articles) respectively. The publication output of female and male scholars maintained rather stable, and the number of articles published by female authors was quite flat compared with that of male authors. Within the total articles culled from JC, further gender analysis by year indicated that during the 10 years there was notable gender disparity in publication rates, particularly in 2018, when there was the biggest and most obvious gap between female and male’s publishing performance.

3.3. Journalism Research (JR)

In the sum of 1,102 articles examined from JR during 2011 to 2020, 21% (230 articles) of articles were written by female single-authors, 17% (184 articles) by female first-authors and 35% (386 articles) by male single-authors, 27% (302 articles) by male first-authors. Of the 616 single-authored articles, female scholars contributed 37%; and of the 486 multi-authored articles, female first-authors occupied 38%. Within the total articles examined from JR, the analysis by year indicates that during these 10 years, there was also a gender disparity in publication rates between female and male scholars, particularly in 2017, when there was the biggest and most obvious gap between with female and male’s output of 31 article and 71 respectively.

3.4. Shanghai Journalism Review (SJR)

Within the total collection of 1,096 papers culled from SJR during 2011 to 2020, 20% (220 articles) of articles were written by female single-authors, 15% (161 articles) by female first-authors and 40% (437 articles) by male single-authors, 25% (278 articles) by male first-authors. The gendered analysis of each year also indicated the considerable disparity between the number of papers published by female and male authors, whether it were single-authored or multi-authored. Male single-authors predominated the higher percentage of single authorships. Of the number of first-authored articles, in nine out of the 10 years from 2011 to 2020, male’s academic output exceeded the female counterparts, with the year 2018 as an exception, in which both parties generated 19 articles.

3.5. Modern Communication (MC)

In the total of 3094 eligible articles examined form MC during the 10-year span from 2011 to 2020, the gendered analysis reveals that 17% (542 articles) of articles were written by female single-authors, 20% (611 articles) by female first-authors and 30% (929 articles) by male single-authors, 33% (1,012 articles) by male first-authors. Even though there was a small increase of female-led article during these 10 years, the gap between female and male scholars’ academic output per year was still obvious. The year 2011 witnessed the biggest disparity of single authorship, that the female single-authors wrote 60 articles less than male counterparts. Of the multi-authored articles, in the year 2017 female first-authors had generated 62 articles less, which marked the most substantial difference.

Research Question 3 sought to list the most prolific researchers in Chinese Journalism and Communication academia from 2011 to 2020. Results indicated that for the years spanning 2011–2020, there were 2,871 scholars who claimed at least one publication in the five journals examined. As shown in Table , it took 16 articles to make the list of the most prolific (top one percent) scholars. Considering the consistent number, a total of 32 individuals are included, only 2 of which are females. The percentage of male scholars enjoys dominant advantage with absolute quantity. This gives answer to the question that, of the top prolific authors, there is a shocking gender disparity in their publication rates between female and male scholars, with a huge gap between 4% and 96%.

Table 1. The most prolific scholars (top one percent)

The aforementioned analysis observed the gender disparity in publication rates. We further conducted a yearly analysis to answer Research Question 4, during the 10-year period how such gap was increasing or decreasing. Figure indicates that the publishing rates of both female and male single-authors have shown a downward trend but with a substantially big gap between genders. In 2014, the difference between male and female single authors was the biggest, and in 2020 was the smallest. On the contrary, during the years 2011–2020, the publishing rates of both female and male first-authors are on the rise and the publication output of male first-authors has also been considerably higher than that of female first-authors. In 2013, the gap was the biggest, and in 2015 was the smallest. Notably, whether sing-authored publication rates or the first-authored, the gap between female and male is narrowing in general, and such trend is especially notable in 2019 and 2020 compared with the prior eight years (see, ).

4. Discussion and conclusion

As indicated by the results of this study, there is a notable disparity in the authorship with female and male single-/first-authors, which favored male. In particular, male occupied the absolute major percentage of the most prolific authors. The data confirmed that Journalism and Communication field is no different from other specialties which have been previously studied. The imbalanced publication rate in academia create challenges for them that are similar to those faced by female scholars elsewhere (Pyke, Citation2013). Female scholars are at a disadvantage because of the conflict between their gender roles and the stereotyped social roles. The traditional family nature of women’s characteristics (Goldthorpe, Citation1983) and the entrenched Confucian cultural influence (Zhao, Citation2007) pushes female scholars to strike the balance between motherhood with academic competitiveness. Working females are still confined to be good mothers and supportive wives (Kooli, Citation2022). They shoulder the majority of responsibilities within family domain, such as tutoring children (Rhoads & Gu, Citation2012). Consequently, female academics devote more time and energy to family duties, which results in penalties for less time dedicated to academic productions. In particular, academic production is an enterprise requiring longer, more intensive periods that are free from interruption (Leberman et al., Citation2016). This role conflict is exacerbated by China’s “two-child” and “third-child” policies, because it deepens the dilemma that female scholars confronted with. Giving birth to more children, they have to make the decision whether to sacrifice the career, because the academic development corresponds with the child raising. Another key reason that leads to female scholars’ lower publication rate is their state of marginalization in the academic network. Although the academic world is claimed to be independent and free, equal and fair, the gender discrimination dose exist in an implicit way (Duch et al., Citation2012; Wang, Citation2011). The publication of articles is not only related to the authors’ personal effort, their academic background and the innovativeness of their research. The authors’ academic impact and interpersonal relationships within the academic community are also the influencing factors (Yang, Citation2013). However, female scholars rarely fit into the oldboy network (Mayer & Puller, Citation2008). Being subtly excluded from the informal networks, females have long been marginalized from core platform. Consequently, they have less access to resources, becoming a hindrance to the academic output. While, masculinity is dominant in the academic culture (Ryan et al., Citation2021; Sang & Calvard, Citation2019), males’ interests are given more priority and allocated with more importance (Zhao & Bao, Citation2020). The cumulative disadvantage over time generates the Matthew effect that ultimately constitutes a bottleneck, constraining female scholars’ publication rate.

Moreover, we identified that such inequality has narrowed slowly with fluctuations, and in recent two years the discrepancy has gradually declined between female and male authors. The narrowing gap can be attributed to the following two possible reasons. First, one interior drive of the growth of female’s publication rates is the progress of their academic qualities. The increasing number of female scholars with higher educational background, particularly the Ph.D. graduates, are flooding into the academic field. A comprehensive study on the educational background of the female scholars, conducted in the school of Journalism and Communication of eight sample universities in Shanghai, revealed that 90.98% female faculty are equipped with doctorates (Lan et al., Citation2021). After years of solid academic accumulation, the majority of the female scholars are capable of generating output with their personal educational support and training experience. What’s more, the tenure-track employment, which is popularly adopted by most universities, turns out to be a powerful push behind these new hands with higher educations, that is, they have to publish more in order to keep their current position, let alone getting promotion or applying for management positions. Another important reason for the declining gap between female and male scholars’ publication rates may relate to the policy intervention that some key policies issued by the Chinese government affecting female scholars in China. Except for the revised Women’s Rights Protection Law in 2005 and the Development of Chinese Women (2011–2020) issued in 2011, other programs have been carried out to ensure that female academics have equal access to grants and funds. The state-level policies reflect an improved recognition of the role conferred to female scholars in academia and a growing awareness of the barriers they are confronted with (Li et al., Citation2018). And the national legislation can improve academic climate and provide professional development that female scholars are perceived with high social status and they are granted with more equal opportunities to grants as well as other professional sources. And increasing number of provincial governments also issued measures to accelerate gender equality in academia. For example, in 2012, Fujian provincial government, for the first time, set up special funds to support female Ph.D. graduates’ research. Other local governments also promulgated measures to improve women scholars’ participation in the scientific work, such as Shandong, Tianjin, Shanghai and so on. These government interventions include better recognizing female scholars’ work and increasing chances for their grant funding, raises, leadership promotion, tenure decisions and so on. After years of implementation, to a certain extent, these promotional policies have begun to show the achievements that female scholars are actually benefited, one of which is the trend of narrowing gap between the female and male scholars’ publication gap. In 2021, the Ministry of Science and Technology in China, together with other national ministries and local provincial councils, issued a list of policies for the sake of providing female academics with relative privileges to guarantee their research. The new proposal also marks a re-affirm of the future decline of gender gap in terms of academic visibility.

Some further thought could be drawn from our results. As Figure reveals, there is a climbing trend of first-authored articles by female scholars, which also marks a thrilling result. However, our results indicated that the number of co-authored papers with female scholars as the first-author was increasing gradually in the 10-year span, which revealed that female academics have already alternated their channels to break through the glass ceiling through cooperation, and co-authorship is one of the effective collaborations. It also supports the previous studies that female academics have more collaborators than male (Bozeman & Gaughan, Citation2011). It may be explained in part that females are believed to possess better communicative skills (Basow & Rubenfeld, Citation2003) and more skilled at academic co-operation (Kuhn & Villeval, Citation2015). So, in order to break through the academic dilemma, female scholars take advantage of their academic communication network to engage more in the male-dominated academia. Collaboration can help female scholars make up the lack of professional resources and better integrate into the academia (Abramo et al., Citation2013). Coauthoring with others is one of the efficient ways to improve the academic productivity of female scholars.

In all, this paper contributes to the global dialogue on the status of female scholars face in terms of publication rate. Overall, based on the data analysis of the selected articles from the top five Journalism and Communication journals from 2011 to 2020 with variability between years, we found substantial underrepresentation of females’ publication rates when compared with their male counterparts’ in this field, which confirms the prior studies. Our research also revealed an overall modest trend in increasing female authors in the multi-authored articles. These findings suggest that some of the observed gender disparities in the academic community will not be solved by hiring of female. Rather, we may also focus on ensuring that women in academia have a level playing field that equally values by policy intervention.

5. Limitations and future research

While the current study offers insight into publication rates and the gender disparity of female and male scholars within and across the top five Chinese Journalism and Communication journals in the past 10-year span, it has several limitations offering opportunities for further study. First, journals included in our study were selected as representative of authoritative journals in the field in China, however, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all the journals or the whole field. Further, we did not account for gender differences in the authors’ leadership position within Communication and Journalism field in this study, due to the lack of access to accurate data source. Management positions enable access to important academic resources and power in decision-making (Zhang & Gan, Citation2016). The superiority of leadership may influence rates of publication in the structural, hierarchic and networked academia in China. The higher publication productivity is one of the essential elements to get promoted to a higher intellectual leadership. Also, the higher position in academia, in turn, implies a hierarchy of academic power that corresponds with higher disposal of internal and external resources, such as their academic output (Chen & Yang, Citation2022). Moreover, we did not include the age variable into our consideration, also due to the lack of possible access to the valid data. The imported tenure-track employment in most Chinese universities have been aroused heated debate on the overwhelming pressure on young scholars. They are under the shadow of authoring more articles in order to keep the job that younger scholars have already joined in the main labor force in the productive academia. Future investigations into contributing factors of the gender discrepancy in publication rates as well as possible correlations between publication rates, leadership positions, as well as age groups of female and males are necessary.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Ethics statement

The researchers obtained the necessary ethics approval from their institution. The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The raw data is stored https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367165372_the_raw_data

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yun Zhao

Yun Zhao is a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Journalism and Communication, Nanchang University, China. Her research areas include gender disparity, women and discourse analysis. She has published several papers on these topics in peer-reviewed journals.

Donghua Liu

Donghua Liu is a Master’s student at the School of Journalism and Communication, Nanchang University, China. Her research interests include feminism and communication.

Yunqian Zhou

Yunqian Zhou (Ph.D.) is currently working as Professor at the School of Journalism and Communication, Nanchang University, China. She has published several articles in refereed journals. She is focusing on the research areas of gender disparity, public opinion and social media.

References

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Caprasecca, A. (2009). Gender differences in research productivity: A bibliometric analysis of the Italian academic system. Scientometrics, 79(3), 517–15.

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Murgia, G. (2013). Gender differences in research collaboration. Journal of Informetrics, 7(4), 811–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.07.002

- Aiston, S. J., & Fo, C. K. (2020). The silence/ING of academic women. Gender and Education, 33(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1716955

- Aiston, S. J., & Jung, J. (2015). Women academics and research productivity: An international comparison. Gender and Education, 27(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1024617

- Appleby, R. (2014). White Western male teachers constructing academic identities in Japanese higher education. Gender and Education, 26(7), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.968530

- Atkin, D. J., Lagoe, C., Stephen, T. D., & Krishnan, A. (2020). The evolution of research in journalism and communication: An analysis of scholarly CIOS-indexed journals from 1915 to present. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 75(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695820935680

- Baccini, A., Barabesi, L., Cioni, M., & Pisani, C. (2014). Crossing the hurdle: The determinants of individual scientific performance. Scientometrics, 101(3), 2035–2062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1395-3

- Basow, S. A., & Rubenfeld, K. (2003). “Troubles Talk”: Effects of gender and Gender-Typing. Sex Roles, 48(3/4), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022411623948

- Bendels, M. H. K., Bauer, J., Schöffel, N., & Groneberg, D. A. (2017). The gender gap in schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Research, 193, 445–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.019

- Boiko, J. R., Anderson, A. J., & Gordon, R. A. (2017). Representation of women among academic grand rounds speakers. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(5), 722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9646

- Bolkan, S., Griffin, D. J., Holmgren, J. L., & Hickson, M. (2012). Prolific scholarship in communication studies: Five years in review. Communication Education, 61(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2012.699080

- Bozeman, B., & Gaughan, M. (2011). How do men and women differ in research collaborations? an analysis of the collaborative motives and strategies of academic researchers. Research Policy, 40(10), 1393–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.07.002

- Burt, R. S. (1998). The gender of social capital. Rationality and Society, 10(1), 5–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/104346398010001001

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2011). Program for the Development of Chinese Women (2011-2020). http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2011-08/08/content_1920457.htm

- Chen, W. B., & Yang, W. J. (2022). What kind of the professional title structure of university teachers helps to obtain academic resources and improve output. China Higher Education Research, 342(2), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.16298/j.cnki.1004-3667.2022.02.08

- Cikara, M., Rudman, L., & Fiske, S. (2012). Dearth by a thousand cuts?: Accounting for gender differences in top-ranked publication rates in social psychology. Journal of Social Issues, 68(2), 263–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01748.x

- Cole, J. R., & Zuckerman, H. (1984). The productivity puzzle: Persistence and change in patterns of publication of men and women scientists. In M. L. Maehr & M. W. Steincamp (eds.), Advances in Motivation and Achievement (pp. 217–258). JAI PRESS INC.

- Duch, J., Zeng, X. H., Sales-Pardo, M., Radicchi, F., Otis, S., Woodruff, T. K., & Nunes Amaral, L. A. (2012). The possible role of resource requirements and academic career- choice risk on gender differences in publication rate and impact. PLoS ONE, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051332

- Elsevier Editors. (2017). Gender in the global research landscape. https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/265661/ElsevierGenderReport_final_for-web.pdf

- Filardo, G., da Graca, B., Sass, D. M., Pollock, B. D., Smith, E. B., & Martinez, M. A. M. (2016). Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: Observational study (1994-2014). BMJ, i847. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i847

- Fox, M. F., & Stephan, P. E. (2001). Careers of young scientists: Preferences, prospects and realities by gender and field. Social Studies of Science, 31(1), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631201031001006

- Gaskell, J., Eichler, M., Pan, J., Xu, J., & Zhang, X. (2004). The participation of women faculty in Chinese universities: Paradoxes of globalization. Gender and Education, 16(4), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250042000300402

- Goldthorpe, J. H. (1983). Women and class analysis: In defence of the conventional view. Sociology, 17(4), 465–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038583017004001

- Griffin, D. J., Bolkan, S., & Dahlbach, B. J. (2017). Scholarly productivity in communication studies: Five-Year review 2012–2016. Communication Education, 67(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2017.1385820

- Griffin, D. J., Bolkan, S., Holmgren, J. L., & Tutzauer, F. (2016). Central journals and authors in communication using a publication network. Scientometrics, 106(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1774-4

- Ha, L., & Pratt, C. B. (2000). Chinese and non‐Chinese scholars’ contributions to communication research on Greater China, 1978–98. Asian Journal of Communication, 10(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980009364777

- Hayhoe, R. (1996). China’s universities, 1895-1995: A century of cultural conflict. NY. Routledge.

- Heijstra, T. M., O’Connor, P., & Rafnsdóttir, G. L. (2013). Explaining gender inequality in Iceland: What makes the difference? European Journal of Higher Education, 3(4), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2013.797658

- Hickson, M., Bodon, J., & Turner, J. (2004). Research productivity in communication: An analysis, 1915–2001. Communication Quarterly, 52(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370409370203

- Hickson, M., Stacks, D. W., & Amsbary, J. H. (1992). Active prolific female scholars in communication: An analysis of research productivity, II. Communication Quarterly, 40(4), 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379209369851

- Hickson, M., Stacks, D. W., & Bodon, J. (1999). The status of research productivity in communication: 1915–1995. Communication Monographs, 66(2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759909376471

- Hickson, M., Turner, J., & Bodon, J. (2003). Research productivity in communication: An analysis, 1996‐2001. Communication Research Reports, 20(4), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090309388830

- Huang, J., Gates, A. J., Sinatra, R., & Barabási, A. L. (2020). Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(9), 4609–4616. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914221117

- Institute for Chinese Social Sciences Research and Assessment. (2021). Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (2021-2022). https://cssrac.nju.edu.cn/cpzx/zwshkxywsy/20210425/i198393.html

- Jagsi, R., Guancial, E. A., Worobey, C. C., Henault, L. E., Chang, Y., Starr, R., Tarbell, N. J., & Hylek, E. M. (2006). The “gender gap” in authorship of ## — A 35-year perspective. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(3), 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa053910

- Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to Token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965–990. https://doi.org/10.1086/226425

- Kataria, A., Kumar, S., & Pandey, N. (2021). Twenty‐five years of gender, work and organization: A bibliometric analysis. Gender, Work, and Organization, 28(1), 85–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12530

- Keating, D. M., Richards, A. S., Palomares, N. A., Banas, J. A., Joyce, N., & Rains, S. A. (2022). Titling practices and their implications in communication research 1970-2010: Cutesy cues carry citation consequences. Communication Research, 49(5), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219887025

- Koning, R., Samila, S., & Ferguson, J. P. (2021). Who do we invent for? patents by women focus more on women’s health, but few women get to invent. Science, 372(6548), 1345–1348. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba6990

- Kooli, C. (2022). Challenges of working from home during the COVID‐19 pandemic for women in the UAE. Journal of Public Affairs, e2829. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2829

- Kooli, C., & Muftah, H. A. (2020). Impact of the legal context on protecting and guaranteeing women’s rights at work in the MENA region. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 21(6), 98–121. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss6/6

- Kuhn, P., & Villeval, M. C. (2015). Are women more attracted to co-operation than men? The Economic Journal, 125(582), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12122

- Lan, J. F., He, C. Z. Y., Xi, X., & Yu, Q. (2021). Why is she? Study on the female scholars of journalism and communication in eight key universities in Shanghai. Wechat log post. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/aOwBtNJJzi-kGfrM8DWlWw

- Leberman, S. I., Eames, B., & Barnett, S. (2016). Unless you are collaborating with a big name successful professor, you are unlikely to receive funding. Gender and Education, 28(5), 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1093102

- Lee, C., & Sohn, D. (2016). Mapping the social capital research in communication: A bibliometric analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(4), 728–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015610074

- Liao, S. Q., Zhu, T. Z., Yi, H. F., Zhou, Y., Yu, J. P., & Xie, Q. R. (2019). Knowledge structure of Chinese journalism and communication studies: Issues, methods and theories (1998-2017). Journalism Research, 163(11), 73–95+124. CNKI:SUN:XWDX.0.2019-11-008

- Li, R., Zhao, Y., & Ma, Y. (2018). Opportunities and challenges faced by female researchers in the new era. Scitech in China, 247(4), 81–82. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.1673-5129.2018.04.021

- Marrone, A. F., Berman, L., Brandt, M. L., & Rothstein, D. H. (2020). Does academic authorship reflect gender bias in pediatric surgery? an analysis of the journal of pediatric surgery, 2007–2017. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 55(10), 2071–2074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.05.020

- Mayer, A., & Puller, S. L. (2008). The old boy (and girl) network: Social network formation on university campuses. Journal of Public Economics, 92(1–2), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2007.09.001

- Meng, Y. (2016). Collaboration patterns and patenting: Exploring gender distinctions. Research Policy, 45(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.07.004

- Ministry of Education. (2021). Number of Female Educational Personnel and Full-time Teachers of Schools by Type and Level 2011–2020 ( Ministry of Education, the People’s Republic of China). http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/

- Morley, L. (2014). Lost leaders: Women in the global academy. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.864611

- Mousa, M. (2021). Academia is racist: Barriers women faculty face in academic public contexts. Higher Education Quarterly, 76(4), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12343

- Oliphant, T. E. (2007). Python for Scientific Computing. Computing in Science & Engineering, 9(3), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1109/mcse.2007.58

- Paisley, W. (1989). Bibliometrics, scholarly communication, and communication research. Communication Research, 16(5), 701–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365089016005010

- Peng, J. E. (2020). Ecological pushes and pulls on women academics’ pursuit of research in China. Frontiers of Education in China, 15(2), 222–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-020-0011-y

- Pledger, L. M., & Standerfer, C. (1997). Women in the 90ʹs are they publishing or perishing in the NCA journals? Distributed by ERIC Clearinghouse. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED417456.pdf

- Pyke, J. (2013). Women, choice and promotion or why women are still a minority in the professoriate. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(4), 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080x.2013.812179

- Quoc Bui, D., Tien Bui, S., Kim Thi Le, N., Mai Nguyen, L., The Dau, T., Tran, T., & Feng, G. C. (2021). Two decades of corruption research in ASEAN: A bibliometrics analysis in Scopus database (2000–2020). Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 2006520. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2006520

- Ren, X., & Caudle, D. J. (2020). Balancing academia and family life. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(2), 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/gm-06-2019-0093

- Rhoads, R. A., & Gu, D. Y. (2012). A gendered point of view on the challenges of women academics in the people’s republic of China. Higher Education, 63(6), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9474-3

- Ruan, N. (2020). Accumulating academic freedom for intellectual leadership: Women professors’ experiences in Hong Kong. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(11), 1097–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1773797

- Ruggieri, R., Pecoraro, F., & Luzi, D. (2021). An intersectional approach to analyse gender productivity and open access: A bibliometric analysis of the Italian national research council. Scientometrics, 126(2), 1647–1673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03802-0

- Ryan, I., Hurd, F., Mudgway, C., & Myers, B. (2021). Privileged yet vulnerable: Shared memories of a deeply gendered lockdown. Gender Work Organ, 28(S2)587–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12682

- Samble, J. N. (2008). Female faculty: Challenges and choices in the United States and beyond. New Directions for Higher Education, 2008(143), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.313

- Sang, K. J. C., & Calvard, T. (2019). I’m a migrant, but I’m the right sort of migrant’: Hegemonic masculinity, whiteness, and intersectional privilege and (dis)advantage in migratory academic careers. Gender, Work & Organization, 26(10), 1506–1525. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12382

- Santos, J. M., Horta, H., & Amâncio, L. (2020). Research agendas of female and male academics: A new perspective on gender disparities in academia. Gender and Education, 33(5), 625–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1792844

- Savigny, H. (2014). Women, know your limits: Cultural sexism in academia. Gender and Education, 26(7), 794–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.970977

- Scharber, C., Pazurek, A., & Ouyang, F. (2019). Illuminating the (in)visibility of female scholars: A gendered analysis of publishing rates within educational technology journals from 2004 to 2015. Gender and Education, 31(1), 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1290219

- Schiermeier, Q. (2019). Huge study documents gender gap in chemistry publishing. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03438-y

- Sonnert, G., & Holton, G. (1995). Gender differences in science careers. Rutgers University Press.

- Stupnisky, R. H., BrckaLorenz, A., & Laird, T. F. (2019). How does faculty research motivation type relate to success? A test of self-determination theory. International Journal of Educational Research, 98, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.08.007

- Su, X., Deng, S., & Shen, S. (2012). The design and application value of the Chinese social science citation index. Scientometrics, 98(3), 1567–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0921-4

- Symonds, M. R. E., Gemmell, N. J., Braisher, T. L., Gorringe, K. L., & Elgar, M. A. (2006). Gender differences in publication output: Towards an unbiased metric of research performance. PLoS ONE, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000127

- Tang, L., & Horta, H. (2021). Studies on women academics in Chinese academic journals: A review. Higher Education Quarterly, 76(4), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12351

- Tinkler, J. E., Bunker Whittington, K., Ku, M. C., & Davies, A. R. (2015). Gender and venture capital decision-making: The effects of technical background and social capital on Entrepreneurial Evaluations. Social Science Research, 51, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.12.008

- Tsui, L. (1999). Courses and instruction affecting critical thinking. Research in Higher Education, 40(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018734630124

- Wang, J. (2011). On gender segregation in academic community: narrative analysis about the female teachers of a research university. Collection of Women’s Studies, 104(2), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.1004-2563.2011.02.004

- Wenzel, J., Dudley, A., Agnor, R., Bassale, S., Chen, Y., Rowe, C., & Seideman, C. A. (2021). Women are underrepresented in prestigious recognition awards in the American urological association. Urology, 160, 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.03.058

- Whittington, K. B. (2011). Mothers of invention? Gender, motherhood, and new dimensions of productivity in the science profession. Work and Occupations, 38(3), 417–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888411414529

- Yang, C. (2013). A review of the situation of female Ph.D. Advisers in terms of gender justice. Academic Exploration, 160(3), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.1006-723X.2013.03.002

- Zaza, N., Ofshteyn, A., Martinez-Quinones, P., Sakran, J., & Stein, S. L. (2021). Gender equity at surgical conferences: quantity and quality. Journal of Surgical Research, 258, 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.08.036

- Zhang, J., & Gan, X. (2016). Career development of young female teachers in research universities: A case study of key universities in Guangdong Province. Journal of Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University, 37(6), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.13408/j.cnki.gjsxb.2016.06.003

- Zhao, Y. Z. (2007). An analysis on the status of female faculty in Chinese higher education. Frontiers of Education in China, 2(3), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-007-0034-7

- Zhao, J. J., & Bao, W. (2020). Reconstruction of the research paradigm of academic career development for women: A study on university female teachers from a multi- dimensional perspective. Education Research Monthly, 160(3), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.16410.77/j.cnki.1674-2311.2020.05.009

- Zidi, C., Kooli, C., & Jamrah, A. (2022). Road to academic research excellence in Gulf private universities. In Heggy, E., Bermudez, V. & Vermeersch, M. (eds.), Sustainable energy-water-environment nexus in deserts (pp. 835–839). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76081-6_106

- Zuckerman, H., Cole, J. R., & Bruer, J. T. (eds.). (1991). The outer circle: Women in the scientific community. W. W. Norton & Company.