Abstract

This article contains the discussion of the history and the preservation of The Old City of Semarang. The Old City was founded at the end of 17th century after an agreement was approved by the Mataram Kingdom and the Vereeniging van Oost-Indische Compagnië (VOC) in 1678. Later on, the colony of VOC developed into a little city surrounded by a fortress in which VOC leaders, its officers, VOC soldiers, European traders resided. Here, some town facilities were built such as municipality house (stadshuis), shops, roads, soldier barracks, warehouses, schools, hospital, church, court, prison, and municipality park. Around the third decade of the 19th century, the fortress of VOC colony was demolished since this city was massively developed. Today, this little city built by VOC is called “Semarang Old City” or “De Oude Stad” (in Dutch), and the municipal government of Semarang is eager to protect and develop this cultural heritage site as a tourism cultural asset due to its unique values and typical cultural attractions. The purpose of this study is to support the Semarang City Government’s plan to propose The Old City of Semarang to UNESCO in order to get recognition as a World Heritage.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The Old City Of Semarang has become an Semarang icon of cultural tourism, which invites many tourists, both foreign and domestic. This site is indeed very attractive as a tourist destination, because there are many buildings heritages and city landscape that are still functioning today. However, the public lacks scientific knowledge about the history and cultural heritages of this Old City. Therefore, this article is expected to provide information to the public that there are many unique and interesting elements in this cultural heritage area. Everyone can have fun taking pictures and watching the beautiful old buildings and also enjoy culinary delights in this old city. Thus, we really hope that this article can be published by Cogent Social Science Journal, which we believe this journal can disseminate this work worldwide, so that the results of this research can be read and understood by people who like cultural tourism.

1. Introduction

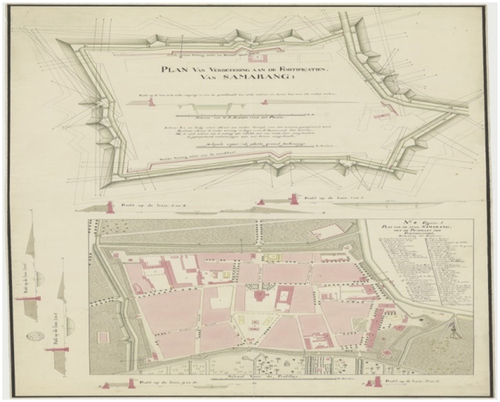

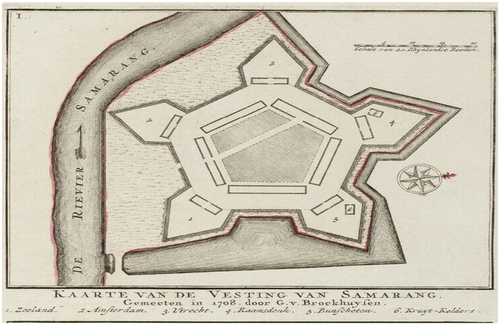

Since hundreds of years before the Dutch’s arrival in Indonesia, Semarang, a coastal area in Central Java Province, has developed as a city. In 17th century, Semarang was one of the districts under the rule of the Sultanate of Mataram, the Islamic Javanese Kingdom. The establishment of Semarang as a city was pioneered by Ki Ageng Pandanarang, a son of the second Sultan of Demak (Prince Sabrang Lor/Pati Unus). In early 1708, Semarang officially became the seat of the VOC government (Yuliati, Citation2005). The map presented below is the fortress city of the VOC and its environment in 1719, including the residence of the regent of Semarang district, which was located to the southwest of the VOC fortress. The picture in figure is the map of ”De Vijfhoek” Fortress and its environment in 1719.

Figure 1. The Map of “De Vijfhoek” fort and its environment in 1719.

Map legend:

A: The Fort of De Vijfhoek (fortress with five corners), located in the eastern side of Semarang River (groote rivier).

B: de bazaar (market)

C: een tuin (a park)

D: Kaligawe (river of Kaligawe)

E: De Dalem (the house of the regent of Semarang)

F: Chineesche Kampoeng (Chinese Village)

G: Europeesche Buurt (European Settlement)

H: Malaische Kampoeng (Malay Village)

I: Javaansche Negarijen (Javanese Villages)

K: De Kustlijnen van1695 (northern coastline in 1695)

L: Het Kalkhuis (chalk warehouse)

M: De Weg naar Mataram (the way to Mataram Kingdom)

N: De Kalk oveners (furnace for burning the limestone)

O: De Javaansche Tempel (Mosque)

P: De Chineesche Tempel (Chinese temple)

Q: Galm (space for announcement)

R: Paseban (meeting room between the regent and the guests)

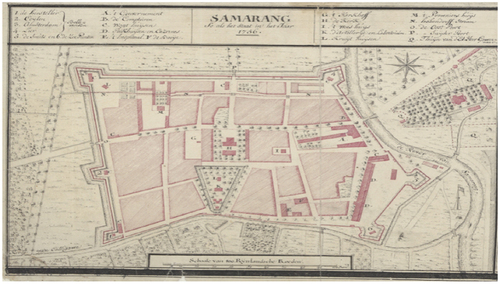

In line with the development of the number of European settlements around De Vijf Hoek fort and providing a better protection to European residents, this fort was dismantled and expanded eastward. This new fort was built in 1741 and was completed in 1756. In the subsequent developments, in 1824 all the walls of this new fort were dismantled, because it had been passed by a high way built during the governor general Daendels (1808–1811) which stretches from Anyer in West Java to Panarukan in East Java. In addition, the number of European residents is increasing and they lived outside this fort (Yuliati, Susilowati, Suliyati., Citation2020). The image below is a map of The Old City in 1756–1824. Below Figure is the map of the Old City 1787 , which was already equipped with the city facilities.

Figure 2. This figure is the The map of The Old City in 1787.

In this 1787 map legend, it can be seen that this fortress city has been organized in a modern way, which has been equipped with city facilities such as: church, town hall, guard posts, soldier dormitories, hotel, hospital, nursing house, orphanage, department store, marine school, and so on. This 1756 map is also accompanied by a description of the names of the buildings and streets in this fortress city (The Old City).

Finding out when Semarang became a residential area can be traced by studying the chronicles, especially Serat Kandhaning Ringgit Purwa of KBG Nr.7 Script, which becomes one of the main sources for a well-known writer of the history of Semarang, Amen Budiman (Budiman, Citation1978). The record of foreign travellers, especially the Dutch, are also an important source for the disclosure of the history of The Old City of Semarang. After the Dutch came to administrative power in this region, they left many reports that could facilitate research on the history of The Old City.

The Old City has been designated as the Cultural Conservation Area. Based on the Law of the Republic of Indonesia No. 11 of Citation2010, the Cultural Conservation Area means “a geographical space unit having two cultural conservation sites or more located adjacent to and/or showing the typical spatial characteristic” (Republic of Indonesia Law No. 11 of Citation2010, Chapter I, Article 1). A geographical space unit may be designated a Cultural Conservation Area if a) containing 2 (two) Cultural Conservation Sites or more adjacent to each other; b) in terms of cultural landscape as the result of formation of human being at age of 50 years; c) having a pattern indicating the space function in the previous era at age of at least 50 years; d) indicating the human being influence in the previous era in the utilization process of large-scale space; and e) indicating the evidence of formation of cultural landscape (Republic of Indonesia Law No. 11 of Citation2010, Chapter III, Article 10).

The Cultural Conservation Area of The Old City contains important values in terms of history, civilization development, as well as economic and political developments with its international networks. The Old City still has cultural sites, including building heritages with various architectural styles from the Middle Ages, Baroque, Dutch architecture, and the modern era. The spatial arrangement of this Old City is very unique since it has government municipal office, trade and business centers, Christian religious building as a symbol of the city center, forts and buildings defence and security, public space, entertainment rooms, orphanages, nursing home, hospitals, and Semarang River, which became the transportation infrastructure connecting the Java Sea and Semarang City and the surrounding regions. This river is the “artery” for foreign immigrants or traders to settle in Semarang (Yuliati, Citation2005). Due to these uniquenesses and outstanding universal values, this Old City has been designated as one of the cultural conservation areas listed in the world heritage tentative list by UNESCO World Heritage Center (kabawisata.com, retrieved on 16 January 2018). One of the important values is that The Old City was once the center of international trade, especially in the sugar and coffee export sector. For more than two centuries, Semarang could keep its ground as the centre of the Dutch rule in middle Java. This VOC’s fortress city was also equipped with a military base and arsenal weapons (Nas, Citation1986). The picture depicted below is the military dormitory and arsenal, which is until now still used as the dormitory of a military police. The picture Figure depicts the location of the VOC military dormitory (left) and the image of the front view of this military dormitory, which is still used as the dormitory of present military police.

Figure 3. The image on the left is the location of the military dormitory based on the 1787 map. The image on the right is the front view of the present military police dormitory, which once was used as a dormitory for VOC soldiers. The location of this dormitory is at Garuda Street No. 16 (formerly: Achterkerkstraat No. 16). Source: Yuliati, Citation2020.

The historical foundation needs to be investigated to discover such important values and authenticity, which are set by UNESCO as the key requirements for listing a cultural conservation area as the world heritage. An area that is now known as The Old City is an area located in Bandaharjo Village, North Semarang District, Semarang City. The Old City has been designated as a City Level Cultural Conservation Area by the Mayor of Semarang through the Mayor’s Decree no. 640/395 of 2018 concerning the Determination of the Status of Cultural Conservation in The Old City. Furthermore, The Old City has also been designated as a Provincial Level Cultural Conservation Site through the Decree of the Governor of Central Java Province No. 432/143 of 2019, and as a National Level Cultural Conservation Site through the Decree of the Minister of Education and Culture No. 682/P/2020 dated 22 July 2020 concerning the Determination of the Old Semarang City Cultural Heritage Site. All these decrees are intended as a legal basis for their preservation and their proposal to the United Nations, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to obtain World Heritage status.

The results of the research conducted by Dewi Yuliati et al. show that The Old City of Semarang already has the conditions that have been determined by UNESCO, especially its historical experience that has been the center of international economic activity, especially between Java Island and the world market (Yuliati et al., Citation2020). The historical value of this Old City and its buildings and city landscape that show the splendor and value of a very attractive architectural beauty have invited many parties to empower this Old City of Semarang as an asset for cultural tourism or educational tourism.

The Cultural Heritage Site of The Old City contains important values in the realm of history, civilization development, economic and political developments, which has international network values, so that The Old City deserves to be called Cosmopolitan, which is a city that has been worldwide. In The Old City area there are still sites and many building heritages, with various architectural styles originating from the Middle Ages, Baroque, Indis architecture, and modern architectural styles (Muhammad, Citation1995).

During the 5 years since it was registered in the tentative list, The Old City should prepare its management, including the arrangement model and the policies to support its preservation and status as a World Heritage. If the requirements cannot be met, its status in the World Heritage Tentative List will be revoked. Based on its outstanding cultural, political, and economic values, it is necessary to conduct an in-depth and comprehensive research to support the preparation of this Old City arrangement model with the concept of world heritage by focusing on the authenticity, conservation management, and utilization for the welfare of the people.

Based on the background described above, this study formulated the following research questions: How is the history of the formation of The Old City? and how is the landscape of the spatial functions during the VOC and the Dutch Colonial Administration period? How do the Semarang City Government and the Community of this Old City support the development of this site as a cultural tourism asset?

2. Method

In this study, the methods of observation, interviews, and literature study were used. The method of observation was carried out by direct observation in The Old City and interviews with stakeholders in this site. From these observations obtained knowledge about physical conditions, access to this site, environmental conditions, many building heritages that are still being functioned, some pictures, and the use of sites in The Old City Area.

The interviews were conducted in in-depth interview method with some stakeholders, namely parties who are members of the Community Association in Developing The Old City (Asosiasi Masyarakat Membangun Oude Stad/AMBO). Some people who have been interviewed are as follows: Jenny (the chairman of the Oen Semarang Foundation), Jessy (AMBO Secretary), Agus S. Winarto (the owner of “Monod Diephuis & Co” building), and Tjahjono Rahardjo (the member of The Agency of Semarang Old City Area Development/Badan Pengembang Kawasan Kota Lama [BPK2L]). The interview was carried out by using an interview guide, which included the following main questions: 1) Is there a community supporting the development of The Old City?; 2) If so, what is the form of their support for the development of The Old City?; 3) What are their obstacles in supporting the development of The Old City?; 4) Why do they intend to develop The Old City? From these four main questions, an in-depth discussion developed about the contribution of the stakeholders in supporting the development of The Old City as a world heritage and tourism asset.

The literature study is focused on books, government law, and regulations that are relevant to the rules of cultural heritage preservation and their use as tourism assets. In addition, information sources from the internet are also used. Based on article 4 of the Republic of Indonesia Law Number 11 of Citation2010, the Cultural Conservation Preservation includes the Protection, Development, and Utilization of Cultural Conservation. Protection is an effort to prevent and overcome damage, destruction, or destruction by means of saving, securing, zoning, maintaining, and restoring Cultural Conservation (Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 11 of Citation2010, Article 1 paras.22, 23). Furthermore, Cultural Conservation Preservation also includes Development, namely increasing the potential value, information, and promotion of Cultural Conservation, whose utilization is through research, revitalization, and adaptation in a sustainable manner and does not conflict with the rules of preservation (Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 11 of Citation2010, Article 1 para. 29). The Old City must be utilized in accordance with the rules for the use of cultural heritage as regulated in Law No. RI. 11 of 2010 Article 1 paragraph 33, namely: Utilization of cultural heritage is the utilization of cultural heritage for the greatest benefit of the people’s welfare while maintaining its sustainability. Based on this regulation regarding the preservation of cultural heritage, the Semarang City government is seriously trying to develop The Old City Area as a cultural tourism asset, namely a tourism activity with the aim of learning and understanding the culture in an area that is different from other areas, and also to get pleasure (Sutomo, Citation2001).

This research is placed within a historical framework and the use of The Old City as a cultural tourism asset and should be based on sustainable tourism development. In developing The Old City, it seems that there are efforts related to sustainable development Goals (SDGs), namely a suitable balance between economic, environmental, and social aspects of tourism development. In general, sustainable tourism is defined as tourism that pays attention to present and future economic aspects, social and environmental impacts, the needs of tourists, industries, and host communities (Ngo & Creutz, Citation2022). Several regulations, institutions, and infrastructures have been established for the sustainable development of The Old City, which will be explained in the discussion of this article.

This study belongs to a historical research. Thus, this study employed the historical method, i.e. searching, discovering, and testing sources to obtain authentic and credible historical facts. The collected fragmentary facts were composed into a systematic, intact, and communicative synthesis. Consequently, this study did not only depart from the main questions about “what, who, where, and when,” but also “how” and “why and what would happen.” The responses to the main questions are both historical facts and elements that contribute to a historical event at a certain place and time. The response to the question “how” is the reconstruction that relates all the elements into a description called history. The response to the question “why and what would happen” indicates the causality relationship (Abdullah & Surjomihardjo, Citation1985, p. 24). The sources were obtained from various libraries, namely the National Library and National Archives in Jakarta, Central Java Regional Library, Semarang City BAPPEDA Library, Faculty of Humanities Library, the internet, and others. The written sources studied were in the form of chronicles, travelers’ notes, government documents, photographs, internet, and newspapers. The results of all activities mentioned above were written down in the form of a historical writing.

The use of The Old City as a tourism asset is researched with an approach based on the Republic of Indonesia’s law on Cultural Heritage No. 11 of Citation2010, as well as provisions on utilization in accordance with UNESCO guidance. In the context of developing The Old City as a tourism asset, this seems to be in line with the concept of commodification, namely the process by which cultural heritage objects and spaces are utilized as commodities for sale. Commodification is very dependent on the needs of tourism market. Furthermore, commodification also depends on the authenticity of the cultural heritage and space (Quang et al., Citation2022). In the research of Dewi Yuliati and her team, it has been proven that many buildings and spaces in The Old City contain authentic values as evidenced through primary historical sources (Yuliati et al., Citation2020). The flowchart is the research stages and the aspects studied to build a narrative about the preservation of The Old City and its utilization as a cultural tourist asset.

3. Discussion

3.1. The establishment of Semarang City in the cultural and political perspective

Based on the chronicles obtained in this study, the establishment of Semarang as an administrative territory began at the end of the 15th century. According to Amen Budiman, based on the Serat Kandhaning Ringgit Purwa of KBG No. 7 Script, the establishment of Semarang was administratively pioneered by Ki Pandan Arang, the son of Prince Sabrang Lor, the second Sultan of Demak. According to this manuscript, in the year 1398 çaka or 1476, Ki Pandan Arang came to a peninsula known as Pulo Tirang (Budiman, Citation1978, pp. 36–37). Pulo Tirang currently belongs to the territory of Mugas and Bergota district in Semarang. At the time of Hindu Mataram Kingdom (Syailendra Dynasty), Bergota was a port in the northern coastal region of Java (Budiman, Citation1978, p. 6). In that area, Pandan Arang performed the order from Sunan Bonang, one of the Wali Sanga (The Nine Saints), to spread Islam among the ajar (Hindu-Buddhist priests/religious teachers) in Pulo Tirang. The manuscript also narrates that Pulo Tirang had 10 ajar (Hindu en Budist priests) areas, i.e. Derana, Wotgalih, Brintik, Gajahmungkur, Pragota, Lebuapia, Tinjomoyo, Sejanila, Guwasela, and Jurangsuru. After Ki Pandan Arang settled in Pulo Tirang, he was able to islamize some of the inhabitants of that area (Budiman, Citation1978, pp. 65–67).

The story of Ki Pandan Arang’s arrival to Pulo Tirang, as described in the Serat Kandhaning Ringgit Purwa of KBG no. 7 Script has similarities to a story written in the Babad Nagri Semarang (the Chronicle of Semarang) as follows.

In addition to the resources mentioned above, there is folklore about Wali Sanga, which narrates that Ki Pandan Arang was originally named Prince Made Pandan. The prince left Demak Sultanate along with his son named Prince Kasepuhan. From Demak, they went to southwest and arrived in a fertile land called Pulo Tirang. In this land, Pangeran Made Pandan founded a pesantren (Islamic boarding school). More and more people came to study in this pesantren, so Pulo Tirang was then inhabited by a lot of people. It is said that in this fertile land grows tamarind trees (in Javanese: tamarind trees is asem), which were still rare (in Javanese: rare is arang) at that time. According to this folklore, from the word asem-arang, the name Semarang was formed (Noertjahjo, Citation1963, pp. 47–48).

According to Serat Kandhaning Ringgit Purwa of KBG Nr. 7 Script, after successfully converting the Hindu-Buddhist priests in Pulau Tirang into Islam, Pandan Arang built a new residential area in Pegisikan, which was later known as Bubakan. The word bubakan comes from the basic word “bubak,” which means opening a piece of land and making it a place to live (Budiman, Citation1978, pp. 76–77). In the era of Ki Pandan Arang, Bubakan was still pegisikan or a coastal area. According to R.W. van Bemmelen, the coast of Semarang, which, at the time of Hindu Mataram Kingdom (in the eighth century), was located in the hilly area of Bergota, expanded northward as a result of the deposition of mud carried by Garang River, which emptied into the Java sea. As a result of the deposition process, the coastline has currently expanded 4–5 km long to the north (Brommer et al., Citation1995, p. 7). In the area of Bubakan, Ki Pandan Arang served as a juru nata (royal officer) of the Demak Sultanate. Therefore, the area of Bubakan was also known as Jurnatan or the residential area of the juru nata.

The information obtained from the historical sources above implies that the formation of Semarang City took place in line with the Islamization process and political expansion of the Demak Sultanate. Before the arrival of Ki Pandan Arang, the fertile lands of Pulo Tirang and Bubakan had been inhabited by Hindu-Buddhism communities. Given the economic potential of these areas, it is understandable that Demak Sultanate has an interest in conquering them politically.

Although Ki Pandan Arang successfully developed the region of Semarang, the new administrative power was run by his son, Prince Kasepuhan, who used the title of Ki Pandan Arang II. This administrative power was granted by the Sultan of Demak to Prince Kasepuhan after Ki Pandan Arang died, in recognition of his services in developing Pulo Tirang. The coronation of Ki Pandan Arang II as the first Semarang Regent took place on 12 Rabiulawal of 954 Hijrah (Prophet Muhammad’s Hijrah year) or 2 May 1547 AD.

The Municipal Government of Semarang determined the above event as the city’s anniversary day. The decision was made at the Plenary Session of the Regional House of Representatives of Semarang Municipality on 29 April 1978. The establishment of this anniversary was based on the Babad Nagri Semarang (the Chronicle of Semarang), which narrates that the appointment of Pandan Arang II as the Semarang Regent happened after the death of Sultan Trenggono, the third Sultan of Demak, in 1546. The coronation was performed on 12 rabiulawal 954 Hijrah along with the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s Mawlid (in Javanese: Sekaten), an event usually held in Demak for the coronation of the Heads of Government such as Sultans and Regents (Municipal Government of Semarang, Citation1979, p. 30). The determination of the anniversary of Semarang City on 2 May 1547 could be understood as a political decision, which is not necessarily based on the facts, since the book entitled Chinese Muslims in Java in the 15th and 16th Centuries: The Malay Annals of Semarang and Cerbon (Graaf, Citation1997) narrates that in 1477, Jin Bun (Raden Patah), the first Sultan of Demak, conquered Semarang by deploying 1000 Islamic soldiers. Similarly, Tomé Pires’ note also shows that he once stopped in Semarang in 1512 and the city was a territory under the control of Demak Sultanate.

3.2. The history of The Old City and its development as a cultural tourism destination

3.2.1. The history of the formation of The Old City (in Dutch: De Oude Stad)

Discussing the Verrenigde Oost Indische Compagnie’s (VOC’s) control over Semarang and the north coast of Java cannot be separated from the relationship between this trading company and the Mataram Kingdom. The position of Semarang as a port city with the trading economic base had attracted the VOC to take control of this city. Semarang has good roads connecting to Kartasura, the capital of the Mataram Kingdom. The travel by road to Mataram Kingdom took less than 3 days, while the travel through Jepara port, the location of VOC trading office before moving to Semarang in 1708, could take more than a week. In addition, the VOC also aimed to control ports along the north coast of Java. The VOC’s interference with Mataram’s affairs in crushing the Trunajaya’s resistance from Madura led this trading company to control the port of Semarang and its surrounding areas. Based on an agreement with Amangkurat II in 19–20 October 1677 and 15 January 1678, the VOC received permission to establish colonies located close to the Regent’s House and on the banks of the Semarang River (Heeres and Stapel (Ed). Corpus Diplomaticum: 121–125). The VOC was also given the right to control revenues from the ports, practice a monopoly over the purchase of rice and sugar, textile and opium imports, get tax exemptions, and control the region of Semarang. Furthermore, a clause was inserted to the effect that the non-natives of Java within the Mataram Kingdom would be subject to the administrative authority and jurisdiction of the VOC (Luc Nagtegaal, Citation1996). Because the location of Semarang was more profitable and strategic for the VOC to connect with Mataram Kingdom in Kartasura, beginning in 1708, the VOC moved its office from Jepara to Semarang (Keyzer, Citation1862).

3.3. Three significant theses of Semarang for VOC

A reason the Company proposed an article on submission of Semarang and surrounding areas in the agreement dated on 15 January 1678, later known as “Agreement of Jepara” (referring to the signing site of the Company’s lodge in Jepara), is based on strategic place of such area. Hence, in the following chapter, it proposes three theses on the significant potency of Semarang and its surrounding areas for sustainability of VOC’s colonialism in Java.

First, Semarang is the coastal area of Northern Java, which is the main access to the Mataram Kingdom. Lekkerker said that this area, according to the VOC, had the crucial meaning since the westward road heading to the center of Mataram Kingdom had to pass Semarang (Budiman, Citation1975, p. 41). Similarly, H.J. De Graaf argued that Semarang had the crucial position as a starting point of departing to the capital city of Palace (Graaf, Citation1987, p. 7). For information, the word of Semarang was used to call Europeeschebuurt (the European settlement), later on known as De Oude Stad (The Old City).

Second, according to Amen Budiman, in his article by citing a letter having been written by Rijcklof van Goens in 1650, argument of Lekkerker was, in fact, incomplete, since Semarang had significant issue in economy for VOC, considering Semarang and its surrounding places as wealthy and fertile area. These potential assets of Semarang and its surrounding places, including Kaligawe, can be acknowledged from a letter written by Rijcklof van Goens in 1650, describing some areas having been visited, started from Semarang to the center of Mataram Kingdom (Budiman, Citation1975, p. 41).

Accordingly, van Goens wrote in his letter: “God has given His blessings to this country by endowing natural resources necessarily required by humankind in their immortal life. The fertile soil has provided an abundance of rice. Various fruits existing in several areas of Indonesia can be found in this area, similar to European and other seeds growing enormously. Beside gold and silver, natural wealth of this country is marvelous, having diverse plants demanded by humankind in this God’s land. It has a great number of quantity that no other countries have. Particularly, this abundance reflects in various types of crops, such as rice, beans, peanuts, and grasses for livestock. In addition, there are many domestic animals, such as buffalo, cow, sheep, goat, deer, female chamois, boar, geese, duck, chicken, dove, turtledove, and all tamed animals exist as well in that someone can buy a cow for only five guldens and someone having three guldens can buy 40, 50, to 70 chickens. Further, there are also wild animals living in forests, such as chamois, female deer, bull, goat, pig, and numerous birds, such as spotted dove, turtledove, crow, white egret, and other animals” (Budiman, Citation1975, p. 41). Information reported by Rijcklof van Goens can actually shed light of researcher’s horizon on Semarang and surrounding villages of Urut-Dalan (villages located along southward of Semarang to Kartasura). During that time, its nature was evergreen and natural. It is proven by the abundance of various beneficial plants and animals for sustainability of people’s live and economy, as turning these areas into wealthy and welfare areas.

In addition, Amen Budiman disclosed a report of Cornelis Speelman dated on 23 March 1678, stating another report of Outers dated on 25 November 1677, explaining that “government of Semarang,” during four-five consecutive years, has gained income of 7000 ringgits, and such income is gained from Harbormaster is 2000 ringgits, tax and fine collected from foreigners is 3000 ringgits, head tax of people lived in Semarang is 1000 ringgits, while head tax from Ambarawa is about 800 ringgits. Still, Speelman reported that Semarang has turned into a center of attraction for traders, with a total of 1000 people (Budiman, Citation1975, p. 41). Therefore, the second argument expressed by Amen Budiman concerning Semarang as fertile, wealthy, and welfare area has completed the first argument as the gate of Mataram Kingdom argued by Lekkerkerker (Citation1938) and Graaf (Citation1987).

Third, an argument on VOC’s reason to conquer Semarang is also expressed by Dewi Yuliati. She argued, that Semarang had become a city since the mid of the 16th century. It is marked with a center of administration located in Kampung Bubakan (later in Kanjengan), ethnic kampongs (Kauman, Melayu, Pecinan, Kampung Jawa), and kampongs of handicrafts, harbormaster, and trading (Yuliati et al., Citation2020). Politically, VOC had accessible relations with the administrator of Semarang and the Mataram Kingdom in Kartasura. Prior to the VOC established their colony in Semarang, there were residents originally coming from diverse ethnicities, such as Java, Chinese, Arabian, Bugis, and Malay. This ethnic diversity, indeed, became the important choice factor, since this diversity was a sign of openness in accepting the existence of the other people. Additionally, the existence of handycraft kampongs could be known from toponymy, the name of kampongs surrounding Bubakan (the center of administrative region of the Old Semarang) adjusted with its resident’s profession, namely: Sayangan (a place for craftsmen of copper goods), Kulitan (a place for leather craftsmen), Batik Village (a place for batik craftsmen), Pedamaran (a place to trade damar or batik dye), Petolongan (a place for guttering craftsmen), and so forth. Then, it showed that these handicraft kampongs depicted that Semarang’s people had demonstrated entrepreneurship to fulfill their daily needs (Yuliati, Citation2005). This condition further became an advantage for the VOC in satisfying its needs and performing its trading activity. The Semarang River was also an important aspect for the VOC in the export-import trade, because in the time of the VOC in Semarang (1695–1800) until the Dutch Colonial Era (1800–1942), Semarang River was still being used as the good link between the hinterland of Semarang and the Java sea or to the Semarang port. The picture below depicts the activity of trading boats in Semarang River carrying imported products to the hinterland of Semarang and vice versa. Figure depicts Semarang River on the western side of the Old City. The picture Figure below is a photo of Semarang River with its Berok Bridge, and the building of the residential office, which was built in 1864.

Figure 4. Kali Semarang (Semarang River) flowing down on the western side of “Kota Lama Semarang” (The Old City) with its Berok Bridge. Until the 1960s, this river still functioned as a commercial waterway from the Java Sea to the hinterland of Semarang and vice versa.

Figure 5. Semarang River and Berok Bridge in 1920, and Het Groote Huis (Residential Office), building on the West Side of Semarang River was built in 1864. This building was the residence office in the colonial era and is now used as the Finance Office Building. The photo also depicts delman, cart, and street sweeper car and people cleaning the sidewalk.

The description of the ancient geographical environment of the city of Semarang can be seen in the note written by Fransçois Valentijn, which reveals that at the beginning of the 18th century, Semarang was one of the largest coastal cities in Java. The Javanese ruler (first Regent of Semarang under the VOC administration, Soera Adi Menggala I) lived in a mansion made of stone. To get to his mansion, one had to go through a large and tall bridge crossing a river. Near the mansion, there was a large market where people could buy and sell various things. From Semarang, there was a road stretching from north to south into the hinterland, which was usually used by the messengers of the rulers of the North-East Java coasts to the Susuhunan in Mataram. In this city, VOC’s ruler for the north-east coasts of Java resided. Approximately 1 mile east of Semarang, there was a town called Terboyo, which was led by a Javanese ruler. The town was not as big as Semarang and the population was only 6000 families. Terboyo’s residents mostly worked as farmers and traders of agricultural products. Besides Terboyo, Valentijn also mentions several villages, i.e. Genuk, Sayung, and Gumulak, located in the east of Semarang (Keyzer, Citation1862).

According to Valentijn, VOC had a number of soldiers and servants who were in charge of carrying out trading affairs. VOC’s residential area was very large and pentagon-shaped, which was fenced with palisades and wall boards with five corners: Raamsdonk, Bunschoten, Zeeland, Amsterdam, and Utrecht. The fortress was known as De Vijfhoek van Samarangh which operated from 1708 to 1741. This period, by archaeologists, is called Phase I. The picture Figure depicts the Five Corners of the VOC Fortress in Semarang 1708.

Figure 6. A Map of The Old City of Semarang equipped with walls of De Vijfhoek van Semarangh (The Five Corners of Semarang Fortress, namely 1. Zeeland, 2. Amsterdam, 3. Utrecht, 4. Raamsdonk, 5. Bunschoten), 1708.

In the Fortress’ neighborhood, the VOC’s ruler lived in a luxurious stone house. On the west side of the fort, Semarang River flew down and people could navigate to certain locations near the settlement of the Europeans.

In the Dutch colonial period (1800–1942), the spatial concept of The Old City was adapted to the cities in Europe, both in the structure and the architecture. The spatial planning of The Old City positioned the Blenduk Church and the government buildings as its center. The spatial arrangement of The Old City looks also similar to the urban concept of Javanese culture, i.e. the unity between government building, public space, and place of worship.

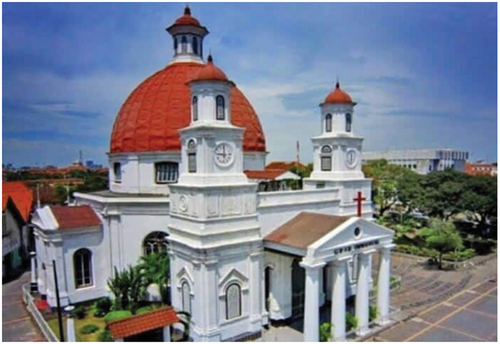

Due to the rapid development of Semarang, finally the De Vijfhoek Fortress was demolished and a new fortress was built to surround the entire Old City area. The construction of this new fortress took place around 1741–1756, which the archaeologists called Phase II (Kriswandono in http://hurahura.wordpress.com/2011/04/22/strategy of historic management: The Case of Kota Lama Semarang, accessed on 15 January 2018). Fort De Vijfhoek was dismantled to make way for a new fort with solid walls, which was expanded to the east. The construction of this new fortress city was carried out after the war broke out with the Chinese and Javanese troops in Semarang, which happened from 14 June to 13 November 1741. However, the Chinese were finally defeated by the VOC who were assisted by hired Buginess troops (Nagtegaal, Citation1996). This new development led The Old City (the new fortress city) to earn the nickname “Little Netherland” because it was similar to cities in the Netherlands. The Old City was also called De Oude stad, because in 1914 there was built a new settlement in the upper town of Semarang, which the Dutch called it “Novo Semawis” (The New Semarang). The Old City was also called by the Dutch “Europeeschebuurt” (European Settlement) since it was the first place for the settlement of the Dutch and other Europeans in Semarang, who mainly engaged as traders and businessmen. This large fortress with a canal surrounding it made The Old City be like the Netherlands’ miniature in Semarang. To facilitate the access in and out for the Europeans, roads were subsequently built within the fortress town with the Main Street called de Herenstaart (now called Jalan Letjend Suprapto). The street which lied precisely in front of Blenduk Church was also part of a 1000 km long way that stretched from Anyer in west Java to Panarukan in East Java. The map presented below is a a map of the Old City in the period 1756-1824. Figure depicts the map of the VOC Fortress 1756, after the development of ”De Vijfhoek” fortress. The picture Figure is ”Blenduk Church” in the Old City, located at Letjen Suprapto Street.

Figure 7. A Map of Fortress City, 1756, after the development of De Vijfhoek with Six Corners: 1) De Hersteller, 2) Ceylon, 3) Amsterdam, 4) Lier, 5) De Smith, 6) De Zee.

Figure 8. Blenduk Church in The Old City, Semarang, located at Jalan Letjen Suprapto (Letjen Suprapto Street; in Dutch colonial era: De Heeren straat), built in 1753, retrieved from NativeIndonesia.com on 5 October 2020.

Blenduk Church which has the original name is Nederlandsch Indische Kerk and is still used as a place of worship until now has become the landmark of Semarang City. This church is called Blenduk because it has a reddish dome-shaped roof made of bronze and two twin towers in front of it. The Javanese people, who have difficulty pronouncing names in Dutch, name it Blenduk. Such a changed pronunciation also occurs on the Berok Bridge (in the Dutch language, the word burg means bridge). This bridge was used to be the gateway to The Old City.

In the first quarter of the 19th century (1824), the walls surrounding The Old City were demolished, but these VOC colonial boundaries are still traceable as there is no significant change in the spatial structure. The boundaries of The Old City are described by Widya Wijayanti as follows: The western wall is located on the edge of the Semarang River, which is turning towards the northeast. The road along the western wall is called Wester-walstraat which extends to Pakhuisstraat (now: Empu Tantular Street). The road along the northern wall, parallel to Jalan Stasiun Tawang, is named Norder-walstraat (now: Jalan Merak/ Merak Street). The eastern wall is aligned with Ooster-walstraat (now: Jalan Cendrawasih/Cendrawasih Street), and the southern wall is parallel to Zuider-walstraat (now: Jalan Sendowo/Sendowo Street). According to Widya, the Europeeschebuurt (the European residential neighborhood) in Semarang was developed like a “salad bowl” due to the contact between various cultures, e.g., Dutch, Portuguese, French, Indonesian, and Chinese. This cultural contact is highly visible from the architectural design of the region (Muhammad, Citation1995, pp. 28–35)

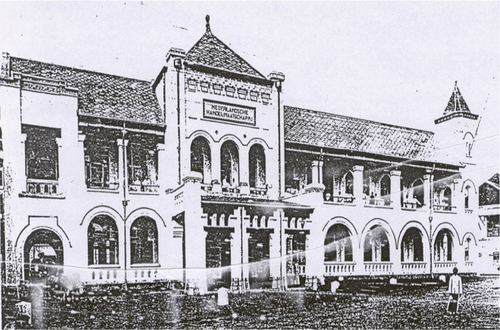

During the VOC and the Dutch colonial period, the area of The Old City was the center of administration, social facilities (hospital, nursing home, orphanage, schools, parks), entertainment building, industries (including communication, transportation, utility, and press), and trade. In this area, many city facilities were built, among others, schouwburg “Marabunta” (“Marabunta” Schouwburg is a theater building) built in 1835. At De Heerenstraat (now: Lt. Gen. Suprapto Street), the main street in The Old City neighborhood, many houses and office buildings were standing, such as landraad office (District Court), N.V. Goud en Zilversmederij voorheen F.M. Ohlenroth & Co. (a very prestigious jewelry store and still existed until the mid-20th century), Cultuur Maatschappij der Vorstenlanden and Mirandole Voûte & Co. (both were large companies managing a number of sugarcane, tobacco, and coffee plantations in Central and East Java, established in 1888), Nederlandsche Handels-Maatschappij (NHM/The Dutch Trading Company), Jansen Hotel (the first European hotel in Semarang), and Seelig & Son (music instrument store). In this area, there was also a large printing and publishing office, G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co., located at Oudstadhuis straat (now: Branjangan Street). The building of G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. is presented in Figure . One of the grandest buildings located in The Old City was the office of Nederlandsch-Indische Levensverzekering en Lijfrente Maatschappij (NILL.Mij. = Dutch Indies Life Insurance Company), which was built in 1916 by an architectural firm, Karsten, Lutjens en Steenstra Toussaint. The building is located at the main street De Heerenstraat (Now: Jalan Letjen Suprapto/Letjen Suprapto Street), in front of Blenduk Church. Below is the picture of Nederlandsch-Indische Levensverzekering en Lijfrente Maatshappij (NILL Mij). Figure is a picture of the building of the ”Nederlandsch-Indische Levensverzekering en Lijfrente Maatschappij (Dutch Indies Life Insurance Company). In Figure is presented the photo of Nederlandsche Handels-Maatschappij (Dutch Trading Company in 1915. The picture in figure is the photos of N.V. Drukkerij G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co in 1858 (left) and 1930 (right).

Figure 9. Dutch Indies Life Insurance Company, which was built in 1916 by an architectural firm: Karsten, Lutjens en Steenstra Toussaint. This building is located at the main street De Heerenstraat (Now: Letjen Suprapto Street, still being used as Indonesia Life Insurance Company).

Figure 10. The office of Nederlandsche Handels-Maatschappij (Dutch Trading Company) in 1915, located in Westerwalstraat (Now: Empu Tantular Street; still being used by Bank “Mandiri”). This building has undergone several changes in function. On the 1787 map, this building was used for the VOC governor’s office for the north coast of Java. In 1826, it was used for the Nederlandsche Handels-Maatschappij office which was in charge of managing the export-import trade; and now for Bank Mandiri.

Figure 11. N.V. Drukkerij G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. in 1858 (left) and 1930 (right). The building is located in The Old City, precisely at the Oudstadhuis straat (now Branjangan Street). G.C.T. Van Dorp was a company of printing and publishing books, newspapers, and other printed media.

Moreover, Nederlandsche Handels-Maatschappij (Dutch Trading Company) (now used as Bank Mandiri Office) was one of the magnificent buildings in The Old City.

3.3.1. Efforts to develop The Old City as a cultural tourism asset

The historical values of The Old City along with its impressive and beautiful buildings have invited many parties to develop it as a cultural tourism asset. At the end of the 20th century, Sutrisno Suharto (Mayor of Semarang from 1990 to 2000) formulated ways to protect and manage the historical ancient sites and buildings in The Old City as follows: (a) The utilization of historical ancient sites/buildings for the welfare of the wider community by arranging this area as well as possible and displaying cultural activities that typically characterize the city of Semarang so as to revive the atmosphere of The Old City that can be offered as a tourism asset; (b) The existing historical ancient sites/buildings need to be protected by rewarding those who contribute to the preservation efforts and applying strict sanctions to those who deliberately neglect or destroy them; (c) It is necessary to immediately issue a Regional Regulation with reference to the higher Regulations and the conditions/needs of the local region in order to have binding power for all parties; (d) The contents of the regional regulation shall cover legal, economic, socio-cultural, science, and technological aspects, community participation in the management, and protection of historical buildings; and (e) In order to make the area management more efficient, it is necessary to determine the institution responsible for managing the historic ancient sites/buildings (Muhammad, Citation1995, pp. 61–62).

These five points concerning the management of The Old City Area have been legally instituted by the Decree of the Mayor of Semarang No. 2.646/50/1992 on Conservation of Ancient/Historical Buildings in Semarang Municipality. This decree regulates the economic, socio-cultural, science, and technological aspects, public participation, protection, and the General Plan of Urban Spatial Planning as set forth in Regional Regulation No. 2 of 1992.

The Regional Regulation is reinforced by Semarang Municipal Government Regulation No. 8 of 2003 on Building and Environmental Management Plan (Rencana Tata Bangunan dan Lingkungan/RTBL) of The Old City Area. According to Article 1d of this Regional Regulation, The Old City is also called Kota Benteng (Fortress Town), i.e. part of Semarang City, which was formerly a Dutch Town once bordered by Fortress, and its boundaries include Jalan Merak (Merak Street) in the north, Sleko Area in the west, Jalan Sendowo (Sendowo Street) in the south, and Jalan Cendrawasih (Cendrawasih Street) in the east. As stipulated in Article 4 of the Semarang Municipal Government Regulation No. 8 of 2003, this regulation is aimed to (a) Protect the historical and cultural assets in the Area of The Old City; (b) Develop the Area of The Old City as a living historical area along with its economic, cultural, and tourism activities under the architectural and environmental hues as part of the history of Semarang City; (c) Achieve the spatial utilization with a mixed usage pattern that is appropriate for the purpose of the conservation and revitalization of historical-cultural areas; (d) Develop awareness and role of the government, private sectors, and the public. This regulation no. 8 of 2003 was revoked and replaced with Regional Regulation No. 2 of 2020 concerning The Old City Area Building Layout and Environmental Plan, which is mainly intended for regulations regarding preservation, which includes research, rescue, protection, development, utilization of this cultural heritage area, and for the legal basis and implementing the building management program and the environment in The Old City area (Semarang Municipal Government Regulation No. 2 of 2020 on Building and Environmental Management Plan of the Area of The Old City. http://jdih.semarangkota.go.id).

In the framework of the implementation of the Regional Regulation, various art performances are frequently held in certain events in the area of The Old City, such as “Wayang on The Street” and “Fashion on The Street.” The physical structure management of The Old City has also been executed, such as paving the roads, building the polder system to handle the tidal flood in this area, and building a 400-m city walk at Jalan Merak (Merak Street) (Merak Street) along the south side of the polder system in 2007.

In the second decade of the 21th century The Municipal Government of Semarang intensified its effort to preserve and develop The Old City by establishing “Badan Pengembang Kawasan Kola Lama Semarang (BPK2L)” (The Agency of Semarang Old City Sites Development), which has function to manage, preserve, and develop The Old City. Further development is that The Old City has just accepted the recognition from the Ministry of Education and Culture of The Republic of Indonesia as a National Heritage with Decree No. 682/P/2020. Based on this decree, Semarang Municipal Government eagers to propose Semarang Old City Site as a World Heritage to United Nations of Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

According to the data obtained from “Badan Perencanaan dan Pembangunan Daerah” [Agency of Urban Planning and Development] of Semarang Municipality, The Old City Site has 274 buildings where 104 buildings are now conservated, including the Oudetrap [storey house] which is already purchased by the Semarang Municipal Government for 8.7 billion rupiahs [about 555.307.339 US$]. The main obstacles in the development and management of The Old City are namely: 1) buildings’ ownership and 2) the need for a very large development fund, about 52 billion rupiahs [about 3.319.078 US$]. In the midst of these obstacles, the Semarang Municipal Government along with “Badan Pengembang Kawasan Kota Lama” [The Agency of Semarang Old City Area Development] keeps struggling. Finally, there are several investors who opened restaurants, cafes, Three D Museum, Semarang Art Gallery, and souvenir stalls along the main street in The Old City, namely Letjen Suprapto Street. One of the buildings that have been renovated for being a café is the H. Spiegel building (located at Srigunting Park—in the Dutch colonial era this park was called stadhuis plein (municipality park)). From the beginning of the 19th century until the end of the Dutch colonial era, this building was a shop selling various goods such as stationery, typewriters, sports equipment, textiles, furniture, and household appliances. In the area of The Old City, there are also cafés: “Tekodeko,” “Filosofi Kopi,” “Pringsewu Restaurant,” “Ikan Bakar Cianjur” Restaurant (this restaurant occupies a former landraad (the district court) during the VOC era), and angkringan (stall-selling a variety of foods and beverages) at night. All of these businesses are handled by private investors. Figure is the photos of district court during the Dutch Colonial Era (left), and now this building is used for restaurant ”Ayam Bakar Cianjur” (right).

Figure 12. The picture on the left is a district court during the Dutch colonial era. The picture on the right: this building is now used for restaurant “Ayam Bakar Cianjur.” Source: researcher’s picture collection.

Semarang Municipal Government has also done some developments in this Old City. The pictures below are examples of the result of Semarang Government action in developing Semarang Old City as one of Semarang City's tourism assets. The Municipal Government seems to pay attention to the aspects of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially in providing regulations, repairing roads, drainage, street lighting, granting business licenses to investors, establishing Badan Pengembang Kawasan Kota Lama (The Agency of The Old City Development), and Museum Kota Lama (The Old City Museum). The following presents a view of the buildings on Letjen Suprapto Street , which have been renovated by the government of Semarang City. Figure is the photo of the view of the Old City in Letjen. Suprapto Street. In figure is presented the photo of the Old City Museum, located in the east side of the Old City.

Figure 13. Some views of building heritages in Letjen. Suprapto Street (In the past: De Heren Straat). Source: Picture collection of the researcher.

Figure 14. Museum Kota Lama (The Old City Museum), located in the east side of The Old City of Semarang, built in 2020 by Semarang Municipal Government, funded by Directorate General of “Cipta Karya”, Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing. This museum is one of the important efforts of the Semarang city government to support sustainable tourism development. Now, this museum is open to the public. Source: Picture made by the researcher.

3.4. Supporting community of Semarang Old City

One of the conditions for a historic area to be designated as a site with world heritage status by UNESCO is the involvement of the community or local residents in the development of an area towards that status. The requirement to obtain world heritage status is in line with the idea of improving people’s welfare based on community-based tourism management, which is an important strategy for poverty alleviation, especially through the provision of business and employment opportunities (Ngo & Creutz, Citation2022). In connection with the creation of job opportunities, The Old City has absorbed a large number of workers to work in cafes, restaurants, retail shops, art and antique market, security units, and created the new managers in business sector.

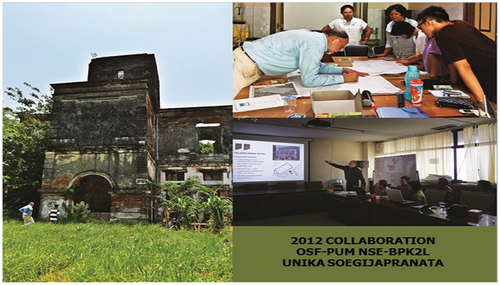

An institution that independently houses the residents of The Old City is called AMBO (Asosiasi Masyarakat Membangun Oudestad/Association of Communities in Developing The Old City). AMBO was formed in 2012, to coincide with a series of activities initiated by several organizations and individuals who have concerns about The Old City in order to obtain world cultural heritage status from UNESCO, which was held on 15–26 October 2012. Some of the organizations that initiated it were OEN Semarang Foundation, Universitas Katholik Soegijapranata in collaboration with The Agency of Semarang Old City Sites Development and the Semarang City Government (interview with Jessi, Secretary of AMBO, 10 August 2019).

AMBO’s organizational structure consists of coordinator 1 (Helen/Blenduk Church Pastor), coordinator 2 (Isti- the administrator of John Dijkstra), Jessi- the manager of Tekodeko Koffiehuis as a secretary, Budi as a treasurer, Puji and Sugiarto as public relations. The members of AMBO are all residents (owners, managers, and tenants of buildings) in The Old City. AMBO did not formally carry out activities between 2015 and 2016, during that period AMBO only engaged in routine meetings once a month or two with members to share information or unrest experienced in this Old City. It was only in 2017 after the management had been permanently determined, AMBO began discussing the statutes and bylaws, as well as taking part in formal events, namely fully participating in the “2017 Semarang Old City Festival (interview with Isti, 2 AMBO Coordinator on 2 August 2019).

All residents of The Old City are openly accepted as the members of AMBO, but until now the percentage of representation of The Old City residents is still small. The number of buildings in The Old City is about 274, while the owners, managers, or tenants who are newly joined are 24, namely: Ikan Bakar Cianjur, Blenduk Church, Asuransi Jiwasraya, Sate Kambing 29, Samudera Indonesia, Atlas, Graha Air Power, Spiegel Bar & Bistro, Semarang Art Contemporary Gallery, John Dijkstra Institute, Black Meet White Cafe, Monoddiephuis Building, Bengkel Sedjati, Achterhuis Guest House, Tekodeko Koffiehuis, Bakso Malang 57, Kedai 46, Sanggar Seni Lentera, Muhammad Bayu Indo House, Rental Fiets, Gelato Matteo, Coffee Philosophy, and Retro Café. Figure is the photo of the series of the first international seminar entitled ”Urban Management Workshop: Semarang Old City Development as a Heritage Business District”.

Figure 15. The series of the first international seminar entitled “Urban Management Workshop: Semarang Old City Development as a Heritage Business District” at Blenduk Church. Source: (Krisprantono Documentation, 2018).

AMBO has organized several international seminars and The Old City festivals to fight for this Old City to be submitted to UNESCO for its status as the world heritage. These series of events have been held five times, from 2012 to 2016. In the following years the seminars and festivals are separated in time but within the same year. Meanwhile, since 2017 no international seminar has been held again, while the festival will continue until 2019, in connection with the Covid-19 pandemic. Figure , which depicts the other photo of that first international seminar. Figure which depicts the Old City Festival supported by AMBO in 2017. Figure is a photo of the Srigunting Park (in the past: ”Stadhuisplein”/the Municipality Park).

Figure 16. The series of the first international seminar entitled “Urban Management Workshop: Semarang Old City Development as a Heritage Business District” at Blenduk Church. Source: (Krisprantono Documentation, 2018).

Figure 17. The Old City Festival which was supporting by AMBO, 2017.

Figure 18. Srigunting Park (in the past: Stadhuisplein/Municipality Park). Resource: Photo collection of the researcher.

Another form of the communities' support is holding the “Kota Lama Festival,” which is held every year, to hold the exhibitions of ancient Semarang culinary, music, clothing, and ancient relics that once existed in Semarang.

4. Conclusions

The Old City is a living, cultural, conservation site with unique historical buildings, which cannot be separated from the formation and development of Semarang City. This area possesses the following historical significant values: 1) its function as a political center, both in the traditional Javanese administrative system and the Dutch colonial system; 2) its function as an economic center, which covers industrial and trading activities and a cultural center as a place of contact between various cultures (the Dutch, European, and local/Javanese culture); 3) demonstrating the typical urban spatial planning in which central administrative offices are adjacent to the place of worship, public space, security post, and dormitory, and entertainment area; 4) having cultural conservation buildings and sites; 5) still indicating clear administrative boundaries. Therefore, this cultural conservation area is an important asset for the development of cultural tourism in Semarang since tourists always want to visit unique and interesting places, which are different from their home places.

The Semarang Municipal Government in cooperation with the private sector has tried to manage The Old City as a cultural tourism asset. Now, the Semarang City government plan has been partially achieved. In the afternoon, after the offices are closed, The Old City is visited by many domestic tourists, there are also often foreign tourists, with the aim of mainly taking photos and relaxing in cafes until the evening. On the weekend, visitors flock to the center of The Old City. Especially in Letjen Suprapto Street, where there are often art offerings and many cafes.

The Old City has developed as a tourism asset because it is strongly supported by stakeholders, namely investors, AMBO (Asosiasi Masyarakat Mmembangun Oudestad/Association of Communities in Developing The Old City), and Semarang City government. Tourism management is still being developed, especially the provision of “Museum Kota Lama” (The Old City Museum) as a medium to display authentic and credible documents, as well as documentary films about its development to date. Managing this Old City Museum is a very important sustainable development method in the preserving of The Old City of Semarang and in its use as a Semarang City tourism asset.

4.1. Recommendation

Based on the result of this research, the researchers give the following recommendations.

The Semarang Municipality Government should immediately prepare a solid and reliable tourism management, because in fact now The Old City has become a tourist destination that is crowded with tourists.

If tourism management is not immediately implemented strictly and continuously, it is feared that many elements of this cultural heritage will be damaged or even lost due to tourism.

All stakeholders of The Old City of Semarang must uphold the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to make this Old City a World Heritage-scale cultural heritage.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University, and conducted by lecturers at the Department of History, the Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University. We have to express many thanks to our respected ones:

(1) Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University

(2) Head of History Department

(3) “Asosiasi Masyarakat Membangun Oude Stad” (Association of the Communities to Develop The Old City of Semarang).

Finally, the researchers hope that this research can be useful to support the Municipal Government of Semarang in managing and developing this Old City as a World Heritage-scale cultural heritage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dewi Yuliati

Dewi Yuliati is a professor of Political History, Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Diponegoro. Her research interest is also aspects related to political issues, such as: worker movement, industrialization and social segregation, government policies on cultural heritage preservation. From 2019 to 2021 she carried out research on The Old City of Semarang and their utilization for the welfare of the community, which includes its development as a cultural tourism asset.

Endang Susilowati

Endang Susilowati is a professor in Indonesian Maritime History, Faculty of Humanities,Universitas Diponegoro. She joined in this research, because The Old City is a part of Indonesian maritime history.

Titiek Suliyati

Titiek Suliyati is a lecturer at the Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Diponegoro University who has many works related to the development of cities in Indonesia. Her works include: the handicraft industry in cities, the Chinese community, etc. Research on The Old City is expected to be a model for research on other old cities.

References

- Abdullah, T., & Surjomihardjo, A. (1985). Ilmu sejarah dan historiografi [History and historiography]. PT Gramedia.

- Brommer, B., Sidharta, A., Eko Budihardjo, A., Siswanto, A. B., Mountens, S. S., & Setiadi, T. S. (1995). Semarang Beeld Van Een Stad [Semarang a picture of a city]. Asia Maior.

- Budiman, A. (1975, August 8). “Semarang Pada Masa Penjajahan Inggris” [Semarang in the English Colonialism Era]. Suara Merdeka. Friday.

- Budiman, A. (1976a, Januari 30). “Masyarakat Eropah Waktu Itu” [The European Community at That Time]. Suara Merdeka, Jum’at.

- Budiman, A. (1976c, January 16). “Masyarakat pribumi semarang tempo doeloe” [the former semarang indigenous society]. Suara Merdeka. Friday.

- Budiman, A. (1978). Semarang Riwayatmu Dulu [The history of Semarang]. Penerbit Tanjung Sari.

- Gedenboek der gemeente semarang 1906-1931 [the memory book of semarang municipality 1906-1931]. N.V. Dagblad De Locomotief.

- Graaf, H. J. D. (1987). Disintegrasi Mataram di Bawah Mangkurat I. 1676–23. Grafipers. July 27, 2018. http://sejarah-nusantaraanri.go.id/corpusdiplomaticum January 16, 2018. kabawisata.com

- Graaf, H. J. D. (1997). Cina Muslim di Jawa Abad XV dan XVI antara Historisitas dan Mitos [Muslim Chinese in Java in XV and XVI centuries between history and Myth]. PT tiara Wacana Yogya.

- Keyzer, S. (ed.). (1862). François valentijn’s oud en nieuw oost-indiën [françois valentijn’s old and new East-Indie]. Wed. J.C. Van Kesteren & Zoon).

- Kriswandono. (2018, January 15). Kasus Kota Lama Semarang. http://hurahura.wordpress.com/2011/04/22/strategi-pengelolaankawasan

- Lekkerkerker, C. (1938). Land en het volk van java [the land and the people of Java]. N.V. Uitgevers Maatshappij Groningen.

- Muhammad, D. (ed.). (1995). Semarang Sepanjang Jalan Kenangan [Semarang in the long way of memory]. PEMDA DATI II Semarang-Dewan Kesenian Jawa Tengah-Aktor Studio [Semarang Municipal Government-Central Java Arts Board-Studio Actor].

- Municipal Government of Semarang. (1979). Sejarah Kota Semarang [The History of Semarang].

- Nagtegaal, L. (1996). Riding the dutch tiger – the dutch east indies company and the northeast coast of java 1680-1743. KITLV Press.

- Nas, P. J. M. (ed.). (1986). The Indonesian City. Studies in urban development and planning. Foris Publications.

- Ngo, T. H., & Creutz, S. (2022). Assessing the sustainability of community-based tourism: A case study in rural areas of Hoi An, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 2(1), 2116812. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2116812

- Noertjahjo, A. M. (1963). Cerita rakyat sekitar wali songo [folklore of nine leaders who spread Islam in Java]. Pradnya Paramita.

- Quang, T. D., Noseworthy, W. B., & Paulson, D. (2022). “Rising tensions: Heritage-tourism Development and the commodification of “Authentic” culture among the cham community of Vietnam”. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2116161. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2116161

- Republic of Indonesia Law No. 11 of 2010. Chapter III, Article 10.

- Semarang Municipal Government Regulation No. 2 of 2020 on building and environmental management plan of the site of The Old City. http://jdih.semarangkota.go.id

- Semarang Municipal Government Regulation No. 8 of 2003 on building and environmental management plan of the site of The Old City. http://jdih.semarangkota.go.id

- Soetomo. (2001). Potensi Wisata Budaya Jawa Tengah [Central java cultural tourism potential]. IKIP Semarang Press.

- Stapel, W. F., & Heeres, J. E. Corpus diplomaticum 1595-1799. 11907-1955. Leiden: Instituut voor Taal, Lanad-en Volkenkunde (KITLV).

- Yuliati, D. (2005). “Dinamika Pergerakan Buruh di Semarang, 1908-1926” [The dynamics of labour movement in Semarang, 1908-1926] Unpublished Dissertation. Gadjah Mada University.

- Yuliati, D., Susilowati. E, & Suliyati, T. (2020). Riwayat Kota Lama Semarang dan Keunggulannya Sebagai Warisan Dunia [The history of The Old City of Semarang and its excellences as a world heritage]. Sinar Hidup.