Abstract

Geographical Indications in Indonesia are also one of the communal property rights regulated in the TRIPs Agreement in addition to communal rights regulated in the Indonesian legal system such as genetic resources, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions. This is by the provisions that can be categorized as geographical indication applicants, namely institutions that represent communities in certain geographical areas that cultivate goods and/or products from natural resources, handicrafts, and industrial products. Provincial or district/city governments can also be applicants for Geographical Indications. Herbal products are one of the commodities that have the potential to be protected through the Geographical Indication system in Indonesia, not only because of the geographical conditions and tropical climate that enrich the natural resources of herbal products but also because traditional knowledge about herbal products has been used for generations since their ancestors. The Indonesian people already have knowledge of ethnomedicine which is used by various ethnic groups that are spread across tribes in various regions in Indonesia. This extraordinary potential is essentially an asset of the nation or state that must be protected and preserved for its existence and development so that it can be of positive benefit to the community. Especially with the COVID-19 pandemic, which cannot be determined with certainty, the diagnosis and treatment of it, and some recent findings on children suffering from acute kidney failure due to prolonged consumption of chemical drug products.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The concept of legal renewal of Geographical Indications is urgently needed and must be preceded by best practices for the protection of Geographical Indications. It is very appropriate to support the protection of herbal products in Indonesia through the Geographical Indication system. As well as support in various other countries such as Europe, Asia, and around the world, precisely as a proposition that gives exclusive rights to geographical names related to products originating from certain regions will translate into providing incentives and promoting local and rural development in the region.

1. Introduction

One of the scopes of intellectual property rights regulated in the TRIPs Agreement is Geographical Indication (GI). As stated in Article 22 Paragraph 1 of the TRIPs Agreement, Geographical Indications are indications that identify goods originating from a member’s territory, region, or locality in that region, where the quality, reputation, or other characteristics of the goods are associated with their geographical origin. Geographical indications in the TRIPs agreement do not only regulate wine or spirit products. This can be seen through the registration of Geographical Indications in Indonesia which consists of various types of products. Miranda explained that in the classification of Geographical Indications, there are agricultural and non-agricultural products Miranda Palar et al. (Citation2021)

Based on the Sustainable Development Goals in Indonesia, there are four pillars as global indicators that must be developed, namely: Social Pillar, Economic Pillar, Environmental Pillar, Legal Pillar, and Governance. The United Nations 2030 Agenda through 17 Sustainable Development Goals is an intensive step toward solving the problems of countries in the world.

Poor forest management and massive exploitation of forests in Indonesia have resulted in forest destruction and the destruction of various forest ecosystems and the biota populations in them. In fact, if it can be managed properly, the use of plants as native Indonesian medicines can increase economic value while simultaneously preserving the environment. This is of course in accordance with the goals of sustainable development in Indonesia which can be developed through the four pillars of the UN agenda in 2030.

Forests in Indonesia have about 1300 species of plants that are efficacious as medicine. More than 370 ethnic or indigenous tribes living in the forest area have local and traditional knowledge of the use of medicinal plants Indonesian Dictionary of Diseases and Medicinal Plants (Citation2000). Sustainable use of biological natural resources and their ecosystem is essentially an effort to control or limit the use of biological natural resources and their ecosystem so that the utilization can be carried out continuously in the future Febrian et al. (Citation2021). This traditional knowledge about the treatment of certain ethnicities is called ethnomedicine. Ethnomedicine is ethnic knowledge that uses medicinal plants to prevent and cure various diseases. Starting from the type of plant, the part of the plant used, the method of treatment to what disease can be cured.

Indonesia is a country that has extensive natural resources, and human resources in the form of traditional knowledge make Indonesia enormous potential in improving the economy and welfare of its people. In particular, the various natural resources that function as medicinal or herbal products. However, currently, Indonesian herbs are faced with several challenges to be able to compete with herbal products from foreign countries, especially after the implementation of various world trade agreements, which have an impact on the increasing flood of various herbal products from China, India, Korea, etc. to the Indonesian market Putri and Kumala et al. (Citation2014)

Geographical Indications are the Intellectual Property Rights system protecting a sign attached to a good or service indicating its geographical origin. A Geographical Indication is the only conventional intellectual property subject matter where the right holder is an entire community rather than an individual.

In Indonesia, legal arrangements relating to Geographical Indications can be found in Law Number 20 of 2016 concerning Marks and Geographical Indications. Article 1 Paragraph 6 explains that Geographical Indication is a sign indicating the area of origin of a good and/or product due to geographical environmental factors including natural factors, and human factors.

Geographical Indications in Indonesia are also one of the communal property rights regulated in the TRIPs Agreement in addition to communal rights regulated in the Indonesian legal system such as genetic resources, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions M. R. A. Palar et al. (Citation2018). This is by the provisions that can be categorized as geographical indication applicants, namely institutions that represent communities in certain geographical areas that cultivate goods and/or products from natural resources, handicrafts, and industrial products. Provincial or district/city governments can also be applicants for Geographical Indications.

Indonesia is a country that has great potential in terms of traditional knowledge which includes art, culture, and other forms of local wisdom. This extraordinary potential is essentially a nation or state asset that must be protected and preserved for its existence and development so that it can be of positive benefit Suparman (Citation2018) to the community, such as food ingredients, various types of food, traditional medicines, arts, and literary works that have not received legal protection.

The herbal product comes from an area which due to geographical environmental factors including natural factors, human factors, or the combination of these two factors gives a certain reputation, quality, and characteristics to the goods and/ or products produced, it can be registered through the Geographical Indication system. Thus, the origin of a certain item which is attached to the reputation, characteristics, and quality of an item associated with a certain area is legally protected Saidin (Citation2007)

Brinckmann (Citation2015) in his journal Brinckmann (Citation2015) on the protection of “geographically indicated” (GI) plants in the context of intellectual property rights. GI plants are named based on geographical area, indicating production in a particular area, the quality and characteristics depend on natural, historical, and cultural factors. Brinckmann explained the globalization of traditional medicine systems such as Ayurvedic medicine and traditional Chinese medicine, Asian species are being introduced for cultivation outside their geographical origins, especially in the EU and US. In contrast to the Chinese concept of “daodi” and the European concept of “origin” or “terroir” is the trend of competition for “grown locally” herbs, i.e. cultivated closer to where they will be used. Reasons include concerns about quality control, contamination from polluted air, soil, and water in some source countries, climate change, supply chain safety and traceability, production costs, and price pressures.

Kedthongma and Phakdeekul (Citation2022), explore the effectiveness of herbals in Thai Geographical Indication (GI). Herbs are one of the most popular alternatives due to their long-term use and knowledge transfer from generation to generation. Moreover, in Thailand, the use of herbs and traditional Thai medicine has long been promoted continuously in government policies.

Geographical Indications are closely related to ecological and environmental factors so the area of origin plays an important role in determining the reputation, quality, and characteristics of an item and/or product registered through Geographical Indications. The problem is, even though Indonesia is considered one of the mega biodiversity countries globally, it seems that the protection of communal intellectual property, especially Geographical Indications, is still relatively low compared to other countries. However, the country’s big challenge is in developing and implementing regulations for herbal products related to the regulatory status, safety and efficacy assessments, and quality control.

2. Material and methods

This study uses a normative juridical method, which uses secondary data in the form of Geographical Indication Description Documents, Legislation, Books, and related journals from legal papers or journals, pharmaceutical journals, and medical journals to obtain research data Suteki and Galang (Citation2018). The data collection technique used is by conducting document studies through application documents for geographical indications originating from the Directorate General of Intellectual Property and literature studies. The statutory approach is used to examine the legal rules used in the geographic indication system in Indonesia. The conceptual approach departs from the views and doctrines that were developed about appropriate protection for herbal products registered as Geographical Indications. This research locations were conducted in several places, namely: Padjadjaran University Library which is located at Jl. Banda No. 42, Citarum, Kec. Bandung Wetan, Bandung City, West Java 40,115. Then virtually at the Center for the Study of Regulation and Application of Intellectual Property (RAKI) Department of Law, Communication Information Technology and Intellectual Property, Faculty of Law, University of Padjadjaran and ISIP (Indonesian-Swiss Intellectual Property Project) Phase II. Research is also conducted through the IP & Innovation Researchers of Asia (IPIRA) Network in the Annual IP & Innovation Researchers Asia (IPIRA) Conference. The data were analyzed descriptively to produce a comprehensive analysis and discussion.

3. Indonesia GIs: Sui generis system

Sui generis in legal terms means that the science of law is a science of its kind. In a different system, all fields or branches of science can also claim to have sui generis properties, namely in terms of the distinctive way of working and the scientific system which is also the object of attention. So actually it is not the only law that is sui generis.

Sui generis Geographical Indication (GI) systems protect the names of products characterized by a specific connection with a given geographical area Zappalaglio (Citation2018). The legal analysis of the link between a product and a specific place, which we will call the “origin link”, is a complex and under-researched matter on which more light must be shed, however.

Protection of Geographical Indications with the sui generis system (Citation2012) is intended as an effort by the Indonesian government to avoid misuse of registered Indonesian Original Geographical Indications from misappropriation and biopiracy to protect herbal products (Citationn.d) to achieve economic benefits. Although Indonesia has applied the Prior Informed Consent (PIC) principle of the Nagoya protocol to the Laws and Regulations in the Intellectual Property sector and ratified it through Law No. 11 Tahun 2003 concerning Ratification of the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from Their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Elements that characterize Geographical Indications so that they can be protected through the sui generis system are First, the element of indication for identification. This element can be seen from the initial formulation in the definition of Geographical Indication, which is an indication that identifies the origin of a good Sasongko (Citation2012). This formulation can be interpreted that Geographical Indications are not limited to the use of geographic names or the name of the place where a good originates. Thus, in addition to the geographical name as a place name, it is possible for other names that are not geographical names to be used to identify the origin of a good.

Second, the territorial element in the state. The determination of the geographical indication protection area refers to an area or area such as a place or place of production or production of a good. The criteria used are flexible and are adjusted to the goods produced. For example, coffee is produced by certain people who live in an area that is integrated between the plantation and the processing factory. The area and name of the territory do not have to be identical to the name and area of an administrative area based on political considerations Calboli (Citation2015). Determination of this area boundary is not important to determine the place, because Geographical Indications are related to geographic areas so Geographical Indications are not allowed to be given to parties outside the geographical area.

Third, is the element of ownership. In the TRIPs Agreement, it is not stated who the owner or right holder is. The TRIPs Agreement only mentions interested parties as parties who must be given legal protection (see Article 22 Paragraph (1) and Paragraph (3), Article 23 Paragraph (1) and Paragraph (2) of the TRIPs Agreement). Geographical indications differ from the general intellectual property rights regime which refers to the subject of rights as owners, such as the creator in copyright and the inventor in patent law Irawan (Citation2017). Indeed, geographical indications do not recognize individual, individual, or private property rights. Therefore, geographical indications only give usufructuary rights to producers or groups of people who produce these goods. In this case, Geographical Indications are the rights of the community.

Fourth, the element of quality, reputation, or other characteristics. In the formulation of the definition of Geographical Indications, certain elements of quality, reputation, or other characteristics are related to or caused by their geographical origin. The formulation of the definition is alternative because it uses the word “or.” Therefore, the TRIPS Agreement does not require that all elements be met, but only one element must be protected. Qualitative factors in the formulation of the wording of the definition of Geographical Indications do not explicitly specify certain conditions. That is, the quality factor can be determined subjectively by the producer concerned by providing data and information about the materials used and their processing. Likewise with the reputation factor.

In Indonesia, the rules relating to Geographical Indications were inserted into Law Number 14 of 1997 concerning Marks in CHAPTER IX A concerning Geographical Indications and Indications of Origin between CHAPTER IX and CHAPTER X. Geographical Indications listed in Article 79 A as a sign indicating the area of origin of a good which due to geographical environmental factors including natural factors, human factors, or a combination of these two factors gives certain characteristics and qualities to the goods produced.

The sign used as an indicator can be in the form of etiquette or a label attached to the goods produced in the form of the name of a place, area, or region, words, pictures, letters, or a combination of these elements. The name of the place in question comes from the name listed on the geographical map or the name that is used continuously as the name of the place of origin of the goods concerned.

After the Mark Law, Number 14 of 1997 was revised to become Law Number 15 of 2001, the rules related to Geographical Indications are not only limited to insertion articles but are specifically regulated in Chapter VII concerning Geographical Indications and Indications of Origin. Protection of Geographical Indications as stated in Law Number 15 of 2001 concerning Marks includes goods produced including natural products, agricultural products, handicrafts; or certain other industrial products.

The institution referred to as the applicant for the protection of Geographical Indications is an institution that represents the community in the area that produces goods, is an institution that is granted a permit to register Geographical Indications, is a Government institution or other official institutions such as cooperatives, associations, and other forms.

Then in 2007, a regulation was issued regarding the procedure for registration of Geographical Indications through Government Regulation Number 51 of 2007 to regulate as a whole then related to the provisions of Law Number 15 of 2001 concerning Marks.

Protection of goods marked with Geographical Indications in this Government Regulation Number 51 of 2007 is broader. A sign is used to indicate the origin of a good, whether in the form of produce, food ingredients, handicrafts, or other goods, including raw materials and/or processed products, either from agricultural products or mining products.

A sign is used to indicate the origin of an item used on goods that meet the provisions in the Requirements Book Bramley et al. (Citation2009). The Requirements Book in question is a document containing information about the quality and distinctive characteristics of goods that can be used to distinguish one product from another of the same category (Citation2019). The characteristics and quality of goods that are maintained and can be maintained for a certain period will give birth to a reputation (fame) for these goods, which in turn allows these goods to have high economic value. In addition, the Requirements Book as stated in Government Regulation Number 51 of 2007 concerning Geographical Indications also includes information on regional maps, history, traditions, processing processes, methods of testing the quality of goods, and labels used.

Therefore, the use of commercial Geographical Indications, either directly or indirectly, on goods that do not meet the requirements are considered Geographical Indications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Regulation of herbal products in Indonesia

As herbal products become more popular, it is important to balance the need to protect the intellectual property rights of indigenous peoples and local communities and their healthcare heritage while ensuring access to herbal products and fostering research, development, and innovation. Every action must follow a global strategy and action plan for public health, innovation, and intellectual property.

No international standardized system for the naming of herbal products is in use Sendker and Sheridan (Citation2017). Some clarity is provided by modern pharmacopeia or comparable official monographs that describe herbal materials along with their desired properties and give Latin names in addition to their vernacular names. Frequently, but not necessarily, these terms refer to the Latin scientific name of the medicinal plant species and the plant part used, e.g., Uvae-Ursi folium (bearberry leaves, Ph. Eur.) or Radix Astragali.

Herbs mean different things to different people. To the botanists, they are plants with soft stems (i.e., non-woody) which die down after flowering. To laymen as well as herbalists, they are plants that can be used to cure ailments; thus, they are synonymous with medicinal plants Chomchalow (Citation2002). The therapeutic potential of herbs has been well recognized by various indigenous systems of medicine. Besides their therapeutic use, herbs are disease prevention and are also used as cosmetics, dietary supplements, and for reducing obesity.

Herbal products which are part of the traditional medicine system, and the novel formulations developed are required to be standardized for safety, efficacy, and potency Balekundri and Mannur (Citation2020). It is required that various techniques are used for the quality control examination of the herbs, which can be regulated to gain the required quality products by setting proper norms. And this in turn will provide the safer use and effective treatment and required potency of the products which will benefit mankind and society by providing means of well-being.

For many millions of people, herbal medicines, traditional medicine, and traditional practitioners are the main source of health care, and sometimes the only source of care. It is a treatment that is close to home, easily accessible, and affordable. It is also culturally acceptable and trusted by many. The affordability of most traditional medicines makes them all the more attractive at a time of soaring healthcare costs and near-universal savings. Traditional medicine is also prominent as a way of dealing with chronic diseases that continue to increase in non-communicable diseases (Citation2013)

WHO has published guidelines for good agricultural and collection practices for medicinal plants aimed at national governments, to ensure herbal products are of good quality, safe, sustainable, and do not pose a threat to people or the environment Unknown author (Citation2004)

Traditional Medicine includes the total of knowledge, skills, and practices based on theories, beliefs, and experiences derived from different cultures, whether explained or not, used in the maintenance of health and the prevention, diagnosis, improvement, or treatment of physical or mental illness Chen (Citation2022)

In Indonesia, traditional medicines are ingredients or ingredients in the form of plant ingredients, animal ingredients, mineral substances, galenic preparations, or mixtures of these ingredients that have been used for treatment from generation to generation, and can be applied in accordance with the prevailing norms in society. Notice the difference based on the table below:

Table 1. Traditional medicine

Based on the level of evidence of efficacy, the requirements for the raw materials used, and their utilization, Indonesian natural medicines are grouped into three groups, namely: herbal medicine, standardized herbal medicine, and phytofamaka (Citation2019). Based on the data obtained, the agricultural and pharmaceutical industries are the ones that use the most biodiversity derived from forest and plant products based on the world’s agricultural GNP in 2005 Chiarolla (Citation2006)

Health development as mandated by Law Number 36 of 2009 concerning Health and Presidential Regulation Number 72 of 2012 concerning the National Health System is carried out through various efforts in the form of national health services.

Regulation of the Minister of Health Number 006 of 2012 concerning Traditional Medicine Industry and Business, in Article 1 Paragraph 1, that traditional medicine is an ingredient or ingredient in the form of plant material, animal material, mineral material, preparation of extract (galenic), or a mixture of these materials. which has been used for generations for treatment, and can be applied by the prevailing norms in society.

WHO also refers to herbal medicines as herbs or herbal products used by the majority of the population for basic health needs. Herbal medicines include herbs, herbal ingredients or plant parts, herbal health products, medicines, dietary supplements, supplements, and cosmetics. Health Spices are an integral part of indigenous peoples and folk medicine Sen and Chakraborty (Citation2017). Herbal medicines are the natural answer to many ailments and are often available locally. For this reason, its use remains widespread and popular in many countries. Due to better monitoring, reports of patients experiencing adverse reactions to the use of herbal products are increasing. The main cause of side effects can be directly attributed to poor quality, especially from medicinal plant raw materials, or incorrect identification of plant species.

By definition, traditional medicine and herbal medicine have differences, herbal medicine comes from herbal products that only come from plants. Meanwhile, in the Regulation of the Minister of Health Number 66 of 2015 concerning Registered Djamoe Outlets and Djamoe Storefronts, it is stated in Article 1 Paragraph 3 that herbal medicine is an Indonesian traditional medicine.

The most appropriate regulation of herbal products based on researchers is contained in the Regulation of the Minister of Health Number 6 of 2016 concerning the Formulary of Original Indonesian Herbal Medicines. The Original Indonesian Herbal Medicine Formulary, hereinafter abbreviated as FOHAI, is a document that contains a collection of native Indonesian medicinal plants along with important additional information about Indonesian medicinal plants.

The information presented includes Latin names, regional names, parts used, plant descriptions/Simplicia, chemical content, safety data, benefits data, indications, contraindications, warnings, side effects, interactions, posology, and bibliography. These herbal plants are then arranged alphabetically and grouped by type of disease in a therapeutic index list which is also arranged alphabetically.

Classification of Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) is clinical trial data that has a level of evidence determined (Level of Evidence Grade)Bhandari and Giannoudis (Citation2006) by Natural Standard/ Harvard Medical School which is a source of evidence-based information regarding safety, danger, interaction, and dosage, in this formulary several herbs are divided into 5 levels of proof.

4.2. Geographical indication applicant: communal property rights

The name of the applicant for Geographical Indications is adjusted to the community group in the area where certain goods are produced who are competent to maintain, maintain, and use Geographical Indications in connection with their business/business needs. Meanwhile, a producer who can produce goods by the provisions stated in the Requirements Book and is willing to comply to always apply the provisions as stipulated in the said Requirements Book may use the related geographical Indications after previously registering himself as a User of Geographical Indications at the Directorate General.

Applicants for Registration of Geographical Indications from Domestic Geographical Indications cannot be owned privately/privately so the parties who can apply as applicants for Geographical Indications are First, the Regional Government. For geographical indication areas contained in one regency/city, the applicant is the Regent/Mayor. If the geographical indication area is in two or more regencies/cities, then the applicant is the Governor. Second, Community Institutions. The basis for the establishment of community institutions applying for Geographical Indications is the Decree of the Regional Head. Institutions that apply for Geographical Indications generally use the name Geographical Indication Protection Society (MPIG), but the use of other names such as Institution, Association, Agency, etc. is also permitted. This institution must be registered with a notary to become a legal entity so that it can move freely in terms of institutional management, finance, and development business activities.

Community Institutions consist of:

Advisor/ Responsible Person, namely the Regional Head (Governor/Regent/Mayor)

Supervisor, namely Head of Service or head of relevant government work units from business actors in the production and marketing of goods and/or geographically indicated products.

Business actors, namely infrastructure actors, producers (producers of goods and/or primary products including seed/seedling producers), processors, and marketing actors (collectors, retailers, exporters, etc.).

Observers of geographical indication products, namely experts and/or actors who can participate in developing the production and marketing of geographically indicated goods/products.

Geographical Indication rights holders may consist of Regional Governments or administrators and institutional members. The management structure of the applicant institution must be legally based on a Decree issued by the regional head. This institution is a representation of the people who have the right to geographical indications. If later there is an institutional arrangement, the said Institution must be in writing to the Directorate General of Intellectual Property of the Republic of Indonesia (DJKI) through the application mechanism for changes to the Requirements Book/Document Description.

This list consists of groups of business actors in the production chain to marketing, including farmer groups/ fishermen/ craftsmen/ breeders, seed providers/ seeds, collectors, traders, exporters, and exporters. This list is important and must exist because it is related to the right to use geographical indications. When at a later date the list of members changes, the institution in question must be in writing to DJKI through a request for changes to the Requirements Book/Description Document.

With it, a geographical indication will provide legal protection/certainty to the quality and quality of the geographical indication product produced by the community. This is by the first Robert M. Sherwood Newman and Sherwood (Citation1996), namely Reward Theory, which is the theory that an author must provide a reward/appreciation in the form of legal protection for his creation as a legal framework that regulates commercial activities so that the implementation of the registration of Geographical Indications can support economic development. The award is given to the government in the form of a certificate of geographical indication as a form of appreciation and legal protection for people who have created or produced products that show Geographical Indications.

The theory of restoration that is given is that an author deserves to be compensated for the hard work, time, and expended during producing his creation. Communities and local governments who own potential geographical indications will get recovery for their hard work, time, and money if the geographical indication products have been recorded and the product indications have been marketed with the increase in the economic value of the product.

The period of protection is the reputation, quality, and characteristics that are the basis for the protection of objects of geographical indications to be maintained. Geographical Indications can also be removed by the Minister of Law and Human Rights if there is no longer any reputation, quality, or characteristics that protect the goods/products of the Geographical Indications and actions that are contrary to national principles, morality, religion, dignity, generality, and morals.

Indigenous groups or communities and local communities may be more concerned with the cultural, social, and psychological dangers caused by the illegal use of traditional knowledge by outsiders from local communities or foreigners which have economic implications Visser (Citation2004). So it can be said that although, for example, the ultimate goal of protection is preservation, a commercialization process can occur in this conservation effort.

Communal ownership character means being the common property of the people who are included in the recorded Geographical Indications area. After registering a product that has the potential for Geographical Indications and obtaining legal protection through Geographical Indications, the community has the exclusive right to distribute and trade the product so that the people of other regions are prohibited from using it on their products. Based on the objective analysis described above, these are the elements that will give rise to the reputation, quality, and characteristics of the product which are marked with Geographical Indications

GIs, therefore, not only reflect the interests of producers but also target domestic (and overseas) consumers who have high purchasing power. In developing countries, implementing a GI mechanism may be seen as a tool to boost development in numerous regions, even though most potential consumers are overseas. In both cases, GIs should be sustainable and pose the question of visibility and recognition.

4.3. Implementation of herbal product protection through geographical indication system

The effectiveness of Herbal Products as drugs can be assessed through the science of pharmacodynamics, which is defined as the study of the actions and effects of drugs at the organ, tissue, cellular, and subcellular levels. Therefore, pharmacodynamics provides information about how a drug exerts its beneficial effects and how it causes side effects Awortwe et al. (Citation2019). By understanding and applying the knowledge gained in studying pharmacodynamics, physicians and other members of the healthcare delivery team can provide safe therapeutic care for their patients.

In the 20th century, some pharmaceutical companies invested massively in plant exploration to find new natural sources of products that might have the potential for the development of new drugs, and a large number of species were filtered for this purpose. The situation changed drastically after the Biodiversity Convention (CBD) came into force in 1993.

Before CBD, the diversity of plants, animals, and world microorganisms was considered an “inheritance with humanity” and exploited broadly. Throughout the negotiations that lead to the CBD, it has been explained by force that such views are completely unacceptable, and vice versa the position that the state has sovereignty over the diversity and genetic resources within their limits is protected through CBD.

Some agree that the discovery of the source of herbal products is protected through intellectual property protection such as patents, but not everyone agrees with it. There is a variety of views about business benefits derived from herbal products when protected through intellectual property, useful in the economy globally, or mechanisms that can encourage biopiracy.

Article 22 TRIPS The Agreement defines GI as “an identifying indication good originating in the Member’s territory, or an area or a locality within that region, where a given quality, reputation, or other characteristics of the goods are caused by its geographical origin.

More than two thousand pieces of traditional knowledge have been inventoried covering medicinal and medicinal plants, traditional carving and sculpture, traditional weaving arts, traditional architectural arts, traditional food and cooking, plant breeding groups, natural dyes, types of wood, and vegetable pesticides Kusumadara (Citation2011). The protection of traditional culture in Indonesia is indeed very weak, both in terms of documentation and regulation in law.

Increased attention is being paid to Geographical Indication laws as a means to protect Traditional Knowledge as both aims to protect communal rights Palar (Citation2017). The reason for this is that Geographical Indications and Traditional Knowledge both aim to protect local traditions which have benefits accruing to local communities Bustani (Citation2018). The difference is that Geographical Indication protects the designation associated with a geographically specific product, while Traditional Knowledge has a broader application to a geographically defined and unique system of knowledge or way of doing things.

Some agree that the discovery of the source of herbal products is protected through intellectual property protection such as patents, but not everyone agrees with it. There is a variety of views about business benefits derived from herbal products when protected through intellectual property, useful in the economy globally, or mechanisms that can encourage biopiracy. Geographical Indication protects the designation associated with a geographically specific product, while Traditional Knowledge has a broader application to a geographically defined and unique system of knowledge or way of doing things. Indonesian law regarding patents number 13 of 2016 patent protection is only valid for 20 years and cannot be extended, whereas herbal products can be protected through Geographical Indication are protected as long as the reputation, quality, and characteristics that form the basis of the protection of a Geographical Indication is granted goods according to Law Number 20 of 2016 concerning Marks and Geographical Indications.

How to produce goods or products of Geographical Indications must be explained from the beginning to the end of the process. For example, agricultural products can be described based on: land cultivation, nurseries, planting/planting methods, care, harvesting, processing, sorting, packaging to storage.

The 2010 Basic Health Research stated that 59.12% (fifty-nine point twelve percent) of the population of all age groups, male and female, both in rural and urban areas use herbal medicine, which is a traditional Indonesian medicinal product. Based on this research, 95.60% (ninety-five point sixty percent) felt the benefits of herbal medicine Wahyuni (Citation2021)

One of the methods in complementary traditional health services is the use of herbs. This policy is regulated in the Regulation of the Minister of Health Number 6 of 2016 concerning the Formulary of Original Indonesian Herbal Medicines. The Original Indonesian Herbal Medicine Formulary, hereinafter abbreviated as FOHAI, is a document that contains a collection of native Indonesian medicinal plants along with important additional information about Indonesian medicinal plants.

Some descriptions of indications for the use of native Indonesian herbal medicines listed through FOHAI at table for various health problems and as supportive in certain cases are as follows:

Table 2. Geographical indications of herbal products registered as FOHAI

This Original Indonesian Herbal Formulary is a guideline for health workers (doctors, dentists, and other health workers) who will practice herbal medicine in healthcare facilities, especially for primary health services at the Puskesmas. This herbal formulary will become a therapeutic reference as a complement to conventional medicine, or it can also be used as an alternative medicine, in certain cases or in patients who cannot tolerate chemical drugs or at the request of the patient himself after getting an explanation from the doctor. Aside from being an alternative and complementary medicine, this herbal formulary also provides promotive and preventive measures to maintain and improve health to stay healthy and fit by consuming herbal medicines.

People’s pessimism in the perception of herbal products and their unpopularity to be built as a protection for Geographical Indications is one aspect of not creating a commodity and market for mass consumption by the public. His understanding of how Geographical Indications related to herbal products can continue to grow and develop in Indonesia, one of which is by creating markets and marketing these herbal products as commodities/goods.

The data of medicinal plants collected includes 15 (fifteen) types of plants, that are ginger, galanga, east Indian galangal, turmeric, zingiber aromatic, java turmeric, black turmeric, Chinese keys, sweet root/calamus, java cardamom, Indian mulberry, phalera macrocarpa, Verbenaceae, king of bitter, aloe vera.

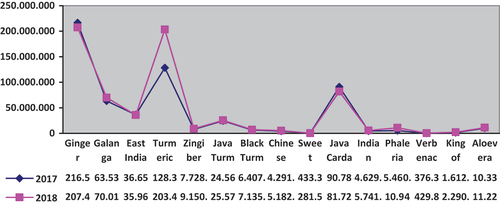

In 2018, almost all rhizome medicinal plants had an increase in harvested area. Plants that experienced the largest increase in the harvested area were turmeric, which increased by 984.66 hectares. The largest increase in production occurred in turmeric plants (increased by 75,118.58 tons). The phaleria macrocarpa, verbenaceae, and aloe vera plants experienced an increase in harvested area. The largest increase in the harvested area occurred for the phaleria macrocarpa plant (6.20 hectares). Three types of rhizome medicinal plants that have the largest production in 2018 are ginger with the production of 207,411.86 tons, followed by turmeric with the production of 203,457.53 tons, and galanga with a production of 70.014,97 tons. (See, Figure ).

Figure 1. Harvested area of group of medical plants in 2017–2018 in Indonesia Statistics of Medicinal Plants Indonesia (Citation2018).

Based on these data, the 15 types of medicinal plants listed in Figure are herbal products that can be found in various regions in Indonesia. Local governments only need to be more focused and dig deeper into the potential of herbal medicine products in their area and have legal awareness to be registered through the protection of Geographical Indications which can increase the selling value of these herbal products. Thus, the community and regional economy will prosper by themselves.

Geographical indications have unique characteristics caused by natural factors so that they influence goods or products produced by a certain area/region. For this reason, ownership of geographical indications cannot be owned by individuals but by community groups residing in certain areas or regions. Even the state as the highest authority is obliged to protect all potential goods/products in its territory Djulaeka (Citation2014)

The special character referred to here is a display or set of displays that distinguish an agricultural product or food ingredient from other products of the same category, which have the same category. A name registered as a certificate of special character must be specific, and refer to the specific character of the food or product, as well as traditional or has been developed through habits. As a guarantee of the right to use the name, registering as a certificate of special character also allows manufacturers to use the Traditional Specialty Guaranteed (TSG logos) Hajdukiewicz (Citation2014)

The positive protection system Puspitasari (Citation2014) has the aspiration to create a rights system through mechanisms such as sui generis laws, contractual agreements, and/or the use of existing intellectual property protection systems as well as enabling indigenous peoples and local communities to protect and promote superior herbal products that have potential.

While defensive protection according to WIPO has an approach in response to the needs of indigenous peoples and local communities who may want the preservation of cultural heritage as the ultimate goal and identify and protect traditional knowledge as an element to promote the conservation of biodiversity and the sustainable use of biological resources and their protection in the context of human rights.

5. Conclusion

Indonesia is one of the ASEAN member countries that protect Geographical Indication products sui generis, although in practice the rules regarding Geographical Indications are still incorporated together with legal rules regarding trademarks. Herbal products are one of the commodities that have the potential to be protected through the Geographical Indication system in Indonesia, not only because of the geographical conditions and tropical climate that enrich the natural resources of herbal products but also because traditional knowledge about herbal products has been used for generations since their ancestors. Herbal products that have been registered through Geographical Indications can be an alternative treatment with guaranteed quality and treatment standards that have been laboratory tested and have legal certainty and benefit value. In addition to having economic value, the protection of Geographical Indications for regional products will have an impact on regional names and prevent unfair competition by using regional names. The protection of Geographical Indications has an impact on higher product value so that Geographical Indications can drive the economy of a region where the Geographical Indication products are located.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fenny Wulandari

Fenny Wulandari was born in Tangerang, Banten, Indonesia. She is a Doctoral candidate from the Faculty of Law Universitas Padjadjaran with a special interest in Intellectual Property Rights, particularly Geographical Indications. Fenny holds a Master of Law majoring in Business Law from the Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia, and a Bachelor of Law from the Faculty of Law, Universitas Diponegoro. Since 2015, Fenny has been working as a lecturer at the Faculty of Law, Universitas Pamulang.

References

- Awortwe, C., Bruckmueller, H., & Cascorbi, I. (2019). Interaction of herbal products with prescribed medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacological Research, 141, 397–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.028

- Balekundri, A., & Mannur, V. (2020). Quality control of the traditional herbs and herbal products: A review. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-020-00091-5

- Bhandari, M., & Giannoudis, P. V. 2006. Evidence-based medicine: What it is and what it is not. Injury, 37(4), 302–306. Evidence-based drug-related concepts (EBM) of evidence hierarchy, meta-analysis, confidence intervals, study design, etc. It is now so widespread, that doctors who are willing to use the current medical literature with understanding have no choice but to become familiar with it. EBM principles and methodologies See. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2006.01.034

- Blakeney, M. (2019). The protection of geographical indications: Law and practice. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788975414

- Bramley, C., Biénable, E., & Kirsten, J. (2009). The Economics of Intellectual Property: Towards A Conceptual Framework For Geographical Indication Research in Developing Countries (pp. 109–149). World Intellectual Property Organization.

- Brinckmann, J. A. (2015). Geographical indications for medicinal plants: Globalization, climate change, quality and market implications for geo-authentic botanicals. World Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 (1), 16–23. cited 2023 Jan 23, Available from https://www.wjtcm.net/text.asp?2015/1/1/16/294843

- Bustani, S. (2018). Perlindungan Hak Komunal Masyarakat Adat Dalam Perspektif Kekayaan Intelektual Tradisional Di Era Globalisasi: Kenyataan Dan Harapan. Jurnal Hukum PRIORIS, 6(3), 304–325. https://doi.org/10.25105/prio.v6i3.3184

- Calboli, I. (2015). Time to Say Local cheese and smile at geographical indications of origin-international trade and local development in the United States. Hous. L. Rev, 53, 373. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/hulr53&div=14&id=&page=

- Chen, Y. (2022). Health technology assessment and economic evaluation: Is it applicable for the traditional medicine? Integrative Medicine Research, 11(1), 100756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2021.100756

- Chiarolla, C. (2006). Commodifying agricultural biodiversity and development‐related issues. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 9(1), 25–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1422-2213.2006.00268.x

- Djulaeka. (2014). Konsep Pelindungan Hak Kekayaan Intelektual. Setara Press: Malang. at 3.

- Febrian, F., Apriyani, L., & Novianti, V. (2021). Rethinking Indonesian legislation on wildlife protection: A comparison between Indonesia and the United States. Sriwijaya Law Review, 5.1(1), 143–160. http://dx.doi.org/10.28946/slrev.Vol5.Iss1.881.pp143-162

- Gangjee, D. (2012). Relocating the Law of Geographical Indications. In Relocating the Law of Geographical Indications (Cambridge Intellectual Property and Information Law (pp. I–0). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hajdukiewicz, A. (2014). European Union agri-food quality schemes for the protection and promotion of geographical indications and traditional specialities: An economic perspective. Folia Horticulturae, 26(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.2478/fhort-2014-0001

- Indonesian Dictionary of Diseases and Medicinal Plants. (2000). (Ethnophytomedica I). Indonesian Torch Library Foundation.

- Irawan, C. (2017). Protection of traditional knowledge: A perspective on Intellectual Property Law in Indonesia. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 20(1–2), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwip.12073

- Kedthongma, W., & Phakdeekul, W. (2022). The Education on The Effectiveness of Herbal in Thai Geographical Indication. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(7), 3812–3823. https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/12001

- Kusumadara, A. (2011). Pemeliharaan dan pelestarian pengetahuan tradisional dan ekspresi budaya tradisional Indonesia: Perlindungan hak kekayaan intelektual dan non-hak kekayaan intelektual. Jurnal Hukum Ius Quia Iustum, 18(1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.20885/iustum.vol18.iss1.art2

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Biopiracy. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/biopiracy

- Miranda Palar, R. A., Ramli, A. M., Sukarsa, D. E., Dewi, I. C., & Septiono, S. (2021). Geographical indication protection for non-agricultural products in Indonesia. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 16(4–5), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpaa214

- Narong Chomchalow. (2002). Spice Production in Asia: An overview. AU Journal of Technology, 5(2), 95–108. http://www.assumptionjournal.au.edu/index.php/aujournaltechnology/article/view/1176

- Newman, P., & Sherwood, R. M. (1996). Legal Framework of the Industrial Economy. In G. Bugliarello, N. K. Pak, Z. I. Alferov, & J. H. Moore (Eds.), East-West Technology Transfer. NATO ASI Series (Vol. 3). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-0151-3_2

- Palar, Miranda Risang Ayu. (2017). The Protection of Intangible Cultural Resources in The Indonesian Legal System. In C. Antons, & W. Logan (Eds.), Intellectual Property, Cultural Property and Intangible Cultural Heritage, 1st Edition (pp. 221–240). Routledge.

- Palar, Miranda Risang Ayu, Sukarsa, Dadang Epi, & Ramli, Ahmad M. (2018). Indonesian System of Geographical Indications to Protect Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions. Journal of Intellectual Property Rights, 23, 174–193.

- Peltzer, K., & Pengpid, S. (2019). Traditional Health Practitioners in Indonesia: Their Profile, Practice and Treatment Characteristics. Complement Med Res, 26(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494457

- Puspitasari, W. (2014). Perlindungan hukum terhadap pengetahuan tradisional dengan sistem perizinan: perspektif negara kesejahteraan. PADJADJARAN Jurnal Ilmu Hukum (Journal of Law), 1(1). https://doi.org/10.22304/pjih.v1n1.a3

- Putri, E. I. K., Rifin, A., Novindra, Daryanto, H. K., Hastuti, & Istiqomah, A. (2014). Tangible Value Biodiversitas Herbal dan Meningkatkan Daya Saing Produk Herbal Indonesia dalam Menghadapi Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN 2015. Jurnal Ilmu Pertanian Indonesia, 19(2), 118–124. https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/JIPI/article/view/8807

- Saidin, O. K. (2007). Aspek Hukum Hak Kekayaan Intelektual (Intellectual Property Rights) (pp. 386). Raja Grafindo Persada.

- Sasongko, W. (2012). Indikasi Geografis: Rezim Hki Yang Bersifat Sui Generis. Jurnal Media Hukum, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.18196/jmh.v19i1.1980

- Sen, S., & Chakraborty, R. (2017). Revival, modernization and integration of Indian traditional herbal medicine in clinical practice: Importance, challenges and future. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 7(2), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.05.006

- Sendker, J., & Sheridan, H. (2017). Composition and quality control of herbal medicines. Toxicology of Herbal Products, 29-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43806-1_3

- Statistics of Medicinal Plants Indonesia. 2018 via https://www.bps.go.id/

- Suparman, Eman. (2018). Perlindungan Hukum Kekayaan Intelektual Masyarakat Tradisional. Jurnal Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat, 2(7), 556–559. http://journal.unpad.ac.id/pkm/article/view/20287/9765

- Suteki, & Galang, T., Legal research methodology (Philosophy, Theory, and Practice). (Depok: Rajawali Press 2018), p. 133

- Unknown author. (2004). Herbal medicines. WHO drug information 2004, 18(1), 27–30. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/72564

- Visser, Coenraad J., & The World Bank. (2004). Making Intellectual Property Laws Work for Traditional Knowledge. In Finger, J. Michael, P., Schuler (Eds.), Poor People’s Knowledge: Promoting Intellectual Property in Developing Countries (pp. 211). Oxford University Press.

- Wahyuni, N. P. S. (2021). Penyelenggaraan Pengobatan Tradisional di Indonesia. Jurnal Yoga Dan Kesehatan, 4(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.25078/jyk.v4i2.2234

- Wex Definition Team, Legal Information Institute. (2022). Misappropriation. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/misappropriation

- WHO Library Cataloging in Publication Data. (2013). Foreword. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014-2023. WHO Press, World Health Organization.

- Zappalaglio, Andrea, ‘The Why of Geographical Indications (University of Oxford) 2018) https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.749006