Abstract

This article examines how a project intended to help local pastoralists facilitates the accumulation of wealth among elites at the expense of the local people. The data was collected qualitatively from five villages classified spatially based on the variability of water availability and access along the catchment. It was gathered through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and observation, which were then analyzed using a thematic data analysis strategy. The findings indicate that the Project associated with privatising communal land has transformed land-related social and production relationships. It has been characterisedby the development ofexploitative sharecropping arrangements involving multiple actors and marketing relationships. Landowners pastoralists have marginally benefited while capitalists maximize wealth without dispossessing the locals from their land, i.e., accumulation without dispossession. The study concludes that the Project served as a tool to reinforce local exploitation by dispossessing profit gains from their land while allowing external investors to grow and prosper. Finally, the article suggests a policy implication aimed at strengthening households’ capacity so that local pastoralists can farm independently on their land and reap the full benefits.

1. Introduction

While we called them (external sharecrop investors) dependents, we became dependent on them (A Karrayu elder, November 2020).

Over the last few decades, Ethiopian pastoral communities have become increasingly associated with recurring drought and famine, as well as targeted relief, reinforcing the government’s view that nomadic pastoralism is no longer viable (Devereux, Citation2010). In response, strengthening sedentary crop farming linked to irrigation has been sought to transform pastoral life (Carr, Citation2017; Fekadu, Citation2014; Markakis, Citation2011; Turton, Citation2021). Given this, the Oromia regional state in the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia launched a large-scale irrigation project in the heart of the Karrayu land in late 2006. Karrayu is a transhuman pastoral group that primarily relies on livestock production practises, with sedentary farming and wage employment becoming increasingly important in recent years (Girum, Citation2013).

This Project, called the Fentalle Irrigation-Based Integrated Development Project (FIBIDP; henceforth “the Project”), draws water from the Awash River, the largest basin on which other modern irrigation schemes have been based since the 1950s (Reta, Citation2018). It was intended to cultivate 18,000 hectares of land in 13 villages (11 of which are in Karrayu; Oromia Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise, Citation2009, Citation2011). The plan was to benefit 43,926 rural Karrayu inhabitants living in 6752 households (ibid), accounting for 71% of the total rural population in the Fentalle Woreda in 2007 (CSA, Citation2008).

The Project was also celebrated with many “firsts,” changing the narrative to the first “community-managed,” first “integrated approach,” and first “regionally implemented venture” (Oromia Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise (OWWDSE), Citation2009, Citation2011). It was hoped to ensure food security and alleviate deep-rooted poverty by supporting livestock production and encouraging staple and cash crop production (Fekadu, Citation2014; Tsion, Citation2011). Unlike the previous projects,Footnote1 this one is said to be “unique” and intended for the local community, from which they will benefit fully. The fact is that the Project does not displace the local communities. Instead, it proceeded with allocating land to the local pastoralists for individual irrigated farming, making the Project an intriguing, unique, and important case study. However, as the informant quoted earlier correctly pointed out, local pastoralists became highly reliant on external investors for their land to be cultivated through sharecropping so that they earned very little while relinquishing good benefits to the investors and their associated actors.

Scholars have well documented the complex and contrasting nature of development projects. Some of this has been broadly linked to two major assumptions: that development is a state instrument intended to realize national interests, including economic, social, and political goals, and that development promotes economic differentiation (Stevenson & Buffavand, Citation2018). It implies that a development project, on the one hand, has served the state’s interest as a “legitimizer of regimes as part of the vision of a good society, and as a shorthand expression for the needs of the poor” (Nandy & Visvanathan, Citation1990, p. 145). On the other hand, it has facilitated inequality, favouring some by creating wealth at the expense of others (Li, Citation2007). However, the process is context-specific, making it imperative to have an exemplar account of a state-driven project to provide an excellent vantage point to understand how the tensions have operated on the ground (Li, Citation1999, Citation2007).

In this regard, a growing body of literature in Ethiopia indicates that the large-scale irrigation projects linked to sedentarization in lowland areas have resulted in land use change and undermined the pastoral livelihood and way of life (see, e.g., Buffavand, Citation2016, Citation2021; Gebresenbet, Citation2021). They also noted that these projects intensified the bureaucratic structures in the lowland areas to control the people and the natural spaces. Others have also documented that these projects have facilitated service provision and promoted economic development geared toward poverty alleviation (see, e.g., Abdi, Citation2015; Fekadu, Citation2014; Girum, Citation2013; Mekonnen et al., Citation2020; Tsion, Citation2011). For instance, referring to the FIBIDP, Tsion (Citation2011) argued that the Project has improved food production, consumption, and access to health and education services. Fekadu (Citation2014) and Abdi (Citation2015) also noted that the same Project strengthened the income of some local households and expanded their livelihood options.

Unfortunately, while these works emphasize the role of development projects such as irrigation in impacting and serving state objectives, little attention has been paid to understanding how these projects play out to create wealth for some while impoverishing others. In light of this, this study demonstrates how a development project intended to benefit the local community facilitated the accumulation of wealth for others at the expense of the locals. It uses the emerging production practises associated with FIBIDP as a lens to understand how this contributes to capitalist production relations and facilitates the exploitation of the local pastoralist community.

The study concludes that the Project bolstered capitalist production and served external actors, primarily sharecrop investors, who accumulated more wealth without displacing locals from their land. The Project also facilitated the exploitation where the local pastoralists benefited only marginally from production relations. In establishing this, this study zoomed in on production practises in the lowland area, representing dynamism in tenancy arrangements, and went further to show how this arrangement depicts capitalist production relations and contributes to the study of capital accumulation without dispossession. Despite its significant contribution, this study is limited in that it lacks quantifiable evidence indicating the proportion of pastoralist landowners engaging in sharecropping contracts, making it difficult to gauge the magnitude of production relationships involving land deals and transactions related to the Project.

2. Context

During the first five years of construction, the Project gradually addressed six villages, though the water was cut off in the last village and scarce in the two downstream villages. Following the water reach, previously communally owned dry grazing land was allotted to households and young peopleFootnote2 for private use to ensure and enable them to farm it and diversify their income through crop production.Footnote3 The transformation in landownership has resulted in the emergence of a “new group of agrarian actors (both internal and external) with different access possibilities to land, production inputs, outputs, capital, and with various levels of knowledge and experience” (Mukhamedova & Pomfret, Citation2019, p. 582).

Unlike the well-documented traditional forms of contractual farming between two actors, a landowner and a farmer, the emerging production relation in the project area is complex and involves multiple actors. These actors include: first, the investors (sharecrop capitalists), who are capitalists able to finance all costs incurred during the production process, including agricultural inputs such as seed, fertilizer, pesticides, labour, and others. Their ownership of wealth puts them at the top of the power structure, giving them an advantage in production relations (Bekele & Padmanabhan, Citation2012). They are generally outsiders from various geographical origins, nearby or distant, and rural or urban areas. These actors are frequently invisible because they finance all production-related costs from afar and may never visit the farm during production.

Second, the main farmers, often migrants from the highlands with good farming experience and skills (Ayalew et al., Citation2016), are primarily responsible for producing horticultural crops, as an agreement is made to produce vegetables for cash. They are contracted by the investors and purchase and provide farm inputs on behalf of the investors, recording expenses, managing the farm activities, and ensuring all production-related tasks are done correctly and timely. Depending on the size of the land contracted, the main farmers also hire one or more field farmers to handle the activities.

Third, field farmers are usually an outsider with the necessary skills and labour. They are the one who performs the day-to-day routine activities of the farm (including watering, seedling production, land preparation, and hoeing) with little assistance from the main farmers. These actors have no active or front-line participation in the sharecropping process. However, they have a direct relationship with the main farmers, with whom they share the marginal portion of the profit at the end of the day. They have no direct communication with the investors and frequently do not even know who the investors are.

Fourth, landowners are local pastoralists with irrigated land. Many of them got the land through government land distribution and owned property rights, though some got it through local arrangements and illicit enclosures with individual motivations. Fifth, sharecrop brokers are typically, but not always, young community members. They could be any local with good communication skills and a network of finance owners wishing to engage in cash crop production. Their role is not limited to mediation alone but goes beyond that as they fence and protect the farm from animal trespassing and damage. They also supervise and ensure that the field farmers receive irrigation water following the scheduled rota for crop watering. Because of this responsibility, they are known as “water providers” in the community (Ayalew et al., Citation2016).

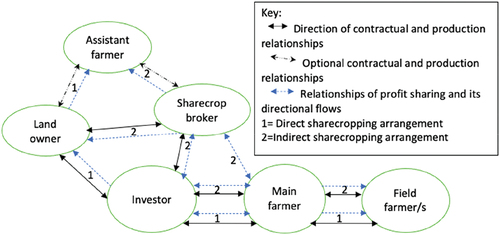

Sixth, an assistant farmers are optional but are hired by either landowners or brokers who lack labour or skill to help with ploughing the land and other farm activities that the landowners or the brokers are supposed to accomplish as part of their contractual agreement in the sharecropping process. The agreement is in exchange for a percentage of profits or a lump sum payment. The following figure (Figure ) summarises the sharecropping actors, contract and profit-sharing relationships.

Following this introductory section, the article discusses the research methodology and the data collection process. The third section focuses on the findings of the study. It briefly discusses how capitalist production relationships in the study area have manifested through sharecropping contracts, profit sharing, and product marketing practices. It also presents the analysis of the finding to situate it within the context of capitalist wealth accumulation. Finally, it concludes by indicating the policy implications of the study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the study area

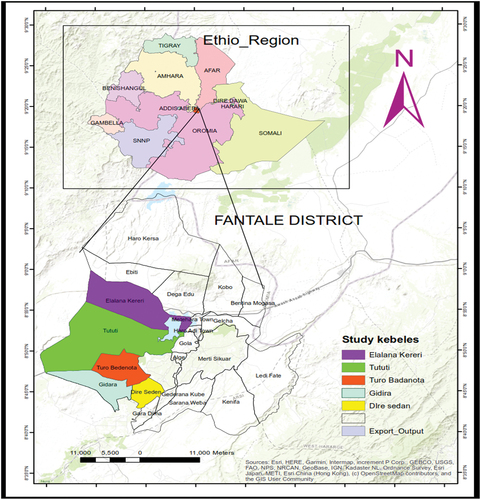

The Karrayu pastoralists live in the upper Awash Valley of the Awash River Basin. The Karrayu land is administratively known as the Fentalle District in Ethiopia’s Oromia National Regional State (see, Figure ). The capital district town, Metehara, is located about 200 km southeast of Addis Ababa, on the Addis-Dire Dawa-Dijibout road, which connects Ethiopia to the rest of the world. The District is distinguished by erratic rainfall, arid and semi-arid climates, and drought-prone areas (Ayalew, Citation2001; Girum, Citation2013). It was also one of the most chronic foods insecure areas in the Oromia Region; nearly half of the rural populations there were food insecure and relied on government assistance through Productive Safety Net Programs (PSNP; Oromia Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise, Citation2009). In light of this, the Project was thought would bring about the betterment of the local people. It represents one of the water-based pastoralist improvement projects that government officials and planners in Ethiopia have dreamed of and emphasized as a poverty eradication and pastoral transformation strategy (Pertaub & Stevenson, Citation2019).

3.2. Research approach

This study adopted an ethnographic research approach. It was based on five months of ethnographic fieldwork in five (agro-)pastoral villages of the Karrayu community, conducted in two rounds between October 2020 and February 2021. These villages were the project reach areas and specifically chosen based on irrigation water access and utilization. They were first systemically classified as upper (Gidara), middle (Dire-Seden and Turo-Bedonota), and downstream (Tututi and Illala-Karari) villages along the irrigation catchment. This classification was done to appreciate the spatial variability of water availability and the resulting variation in production relationships. The Karrayu pastoralists from the Fentalle district served as the population of this study.

3.3. Source of data

Both primary and secondary data sources were used for this study. The primary data were obtained through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions (FGD), and observation. The secondary information mainly came from written records and archival materials. These sources included academic journals, books, published and unpublished materials, project proposals, and relevant official reports.

3.4. Data collection instruments and procedures

The first round of data was collected primarily from Gidara and Illala villages using various data collection techniques such as in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and observation. Meanwhile, based on the preliminary findings from the first round, it was decided to have more information to deepen the understanding of the production relationships involving land deals and transactions that were reinforced due to the Project’s implementation. Thus, more qualitative data was collected from the two earlier villages and officials in the second round. However, intermittent visits were also made to the remaining Villages to conduct interviews with a few older people and government-employed development agents (DAs).

3.4.1. In-depth interview

In-depth interviews were conducted with informants from local communities of various ages, genders, and responsibilities (men, women, and young people; community elders and village representatives); and external actors working in the villages (farmers, capital owners, and agriculture produce market brokers). It was intended to have an individual’s point of view and a variety of attitudes to comprehensively understand the issue under study. An attempt was made to interview key community members, who were assumed to have more knowledge and be able to articulate the everyday practices associated with the irrigation project. The in-depth interview provided a more detailed and broad range of data, including production and land transaction practices and marketing relationships. Furthermore, issues concerning resource access and ownership (such as land and water) and negotiation and competition among actors over the resources were addressed. In addition, local and high-level officials involved in project-related activities were interviewed to learn more about the Project’s implementation and practises and the emerging economic relationship that resulted. The interview guide was used, but questions were not always ordered and worded the same way, allowing for different follow-up and probing questions. Accordingly, 62 purposively selected research informants participated in the interview.

3.4.2. Focus Group Discussion (FGD.)

The FGD was used to have group meaning and consensus related to people’s experiences, ideas, and opinions about the development of the Fentalle irrigation project. It was also used to understand everyday production and marketing practices (including struggle and negotiation over resource access, land transactions, crop production, and marketing) linked to the Project. Four focus group discussions, each with seven participants, were held with a group of elders, women, young cooperative members, and girls involved in agricultural product sales; a total of 28 participants participated. The same guiding questions guided the FGD as the in-depth interviews. The discussion was audio-recorded and held in the local language (afan Oromo). One of the authors served as a notetaker, while a local university graduate served as a facilitator. The FGDs generally last between 75 and 105 minutes.

3.4.3. Observation

Observation allows for understanding any discrepancies between the information gathered and the actual phenomena on the ground (Coleman in Yihunbelay, Citation2020). The observation was critical in this study for gathering practical phenomena to supplement the data gathered through interviews and focus group discussions. Accordingly, observations were made at the farming site to understand the daily routine related to irrigation farming practices, such as crop production and management, crop harvesting and marketing, land use patterns, and water distribution and management along the canal.

3.5. Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data for this study. The audio-recorded information gathered through focus group discussions and interviews was first transcribed, translated, and written on a computer to make it ready for analysis. Information from field observations was described, noted, and organized daily and processed and ready likewise. Then qualitative information from the different sources was coded and categorized to generate a small number of themes using Atlas.ti 9, which were then summarised and interpreted.

3.6. Ethical statement

Utmost care was taken in this study to maintain the ethical obligation essential in social science endeavours. A formal letter representing an ethical clearance from Addis Ababa University was obtained and submitted to the Oromia Pastoralist Development Bureau; from there, it was directed hierarchically to the local administrative unit as an entry point to reach the local community. During the fieldwork, oral informed consent was obtained from each study participant to record their voice and take photographs after explaining the purpose of the study. Participation in the research was entirely voluntary, and no study participants were forced to involve in interviews or focus groups. Furthermore, all provided information was kept confidential, and pseudonyms or unique identification were used to maintain anonymity.

4. Result and discussion

Crop cultivation in the study area has involved many actors connected through sharecropping relations, forming a continuum along the production line to market the produce. The landowner is on one end of the continuum, while the capitalist is on the other, with associated actors in the production relations connecting the two. These various actors have collectively reproduced and facilitated the capitalist relation of accumulation and exploitation.

According to informants, due to factors impeding their ability to access their lands, such as a lack of technology, capital, knowledge, labour, markets, and an entrepreneurial attitude toward farming, many sharecropped their land to others to generate a marginal profit. These constraining factors, combined with land tenure transformation in the area, accelerate the land market and contributes to the growing prevalence of sharecropping (Deininger et al., Citation2011; Khai et al., Citation2013). Individualizing land rights has promoted capitalist relations of production and facilitated exploitation (Li, Citation2014). For example, Bekele and Padmanabhan (Citation2012) observed that privatizing communal land in the Afar Region (adjacent to the study area) allowed for more flexible land use and sharecropping arrangements which were unfavourable for many pastoralists.

The capitalist mode of production in the context of FIBIDP is based on exploitation in “ … the commodity market (marketing the produce) and the place where surplus value is produced (the farm field on which the sharecropping arrangement is made)” (Luxemburg, Citation2003, p. 432), as discussed further below.

4.1. Sharecropping contract and complex profit-sharing arrangement

In the project areas, various sharecropping modalities are practised. These differ depending on the number of actors involved, the type of contracting actors (local-local or local-external), how the deal is made (direct or indirect), and the types and purposes of the crops grown (staple or cash crop). This article focuses on the sharecropping process between local and external actors for cash crop production. In such cases, the two most common methods of dealing with sharecropping contracts are direct and indirect. However, these two arrangements are not equally important across the study villages. Certain types of arrangements are more common in some villages than others.

5. Sharecropping contract (this has to be numbered 4.1.1.)

The first form of contract is that the Karrayu landowner sharecrops the land directly with someone wishing to produce cash crops. In this case, households with irrigable land lacking the necessary agricultural skills, labour, draught power, or capital to manage the farming by themselves enter into a sharecropping arrangement with someone who has the potential to do so. This agreement is often made between the local landowners and the external capitalists, though a few local entrepreneurial agro-pastoralists also contract the land for a cash crop. In this arrangement, a minimum of three actors have involved: the landowner, the investor, and the main farmer.

The sharecrop investor mobilizes the production process through financing and contracting the main farmer who leads and manages the actual farm activities. On the other hand, the landowner fences and protects crop damage from animals, provide irrigation water and ensures the security of farm workers. He also ploughs land if the agreement requires it (in the case of an equal-half share). These obligations necessitate the active participation and presence of landowners. As a result, households with limited migration or migratory households with young members in charge of farming frequently enter into direct contracts with outside investors.

The second type of contract occurs when the landowner indirectly contracts out his land to an external investor via a sharecrop broker. In this case, the landowner has no connection with the investor and must rely on the broker to cultivate their plot. It is widely practised in all villages, though it is relatively more dominant in downstream villages (Tututi and Illala), and some parts of middle-stream villages (Dire-Sadene and Turo-Badenot). It is more difficult, if not impossible, for landowners in downstream villages to find investors to sharecrop directly. However, the situation is somewhat better in upper and middle villages, though it is still challenging.

According to informants,Footnote4 this is because, first, there is limited or no local pastoralist fellow with capital and sharecrop-in irrigated land to grow cash crops independently, although such an entrepreneur is growing gradually in Gidara, an upstream village. Second, external investors always try to avoid directly sharecropping land with households with whom they had not contracted before or had no previous relationship to reduce the risks associated with trust issues. Instead, they prefer to access it through intermediaries with whom they have already created long-term partnerships and confidence. Third, sharecrop brokers spread false rumours to investors that some landowners cannot be trusted, causing investors to be hesitant to enter into contractual agreements without involving brokers. “Some brokers even intimidate main farmers working for investors who made sharecropping deals without the involvement of brokers”.Footnote5 Fourth, in downstream and some parts of middle stream villages, only a limited number of investors are coming to the villages because of irregular irrigation water access. However, in contrast, in Gidara a higher number of investors are coming in from the nearby area due to regular irrigation water and the closeness of the village to rural towns dominated by people of farming background (Ayalew et al., Citation2016).

In general, households heavily dependent on the pastoral mode of production and those migrating away with their livestock preferred this arrangement. However, this is not limited to such households because many in the village give their land to brokers. In this arrangement, the landowner agrees with a local agro-pastoralist (literally: broker) who can work on the land while acting as a mediator with the responsibility of sharecropping out to a third-party investor. The sharecrop broker either farms the land for staple crops or sharecrops it out, depending on the circumstances.

6. Complex-profit sharing arrangement (this has to be numbered 4.1.2.)

Given the number of actors involved in land transactions and production relations, the apportioning of gains from the land becomes very complex. The share of benefits depends on the role of individual actors in the sharecropping arrangement and the initial agreement each party reaches with their counterparts. It also depends on whether the contract is “direct” or “indirect”. The two dominant sharing arrangements that coincide with these contracts are “equal-half” and “one-third” for cash crop production. These are exploitative to the landowners due to the unfair share that landowners retained in the production relationships.

An equal half refers to a profit-sharing arrangement that is concluded with an equal share of the benefit between two front actors in a land transaction deal. If the agreement is direct, the investor shares profits with the landowner. In contrast, if the agreement is indirect, the sharecrop broker becomes the front actor in sharing profits with the investor. This is the most common form of sharing arrangement in Gidara, Dire-saden, and to some extent, in Turo-Badanot. On the other hand, one-third is the share agreement in which the profit is divided equally among three front-runner parties: the investor, the main farmer, and the land owner or investor, depending on the contract. The community members saw this arrangement as more unfair than the equal half, and households in all villages wished to avoid it but frequently accepted it due to a lack of alternatives and investor insistence.Footnote6

The crops have been sold on the market, and then the financer (investor) is reimbursed for the cost he incurred during production. The remaining funds will be divided equally between the two and three front actors in “equal-half” and “one-third” arrangements. Though the terms “half-equal” or “one-third” share are used, the actual benefit retained by the landowner is much lower. Because this is further divided among other actors involved in the production relationships.

In the case of indirect and equal-half, cash from the sold products will be divided equally between the sharecrop broker and the investor. The sharecrop broker then further apportioned his share to the landowner and his side assistant farmer. The investor also further divides rarely half of what he earns, but he usually shares less profit with the main farmer on his side. Likewise, based on their agreement, the main farmer often shares half to a quarter of his profit with the field farmer/s. In this case, if the main farmer hired more than one field farmer, the field farmers would further equally divide what they received from the main farmer.

In an indirect and one-third sharing arrangement, the process of allocating profit among the involved actors is similar to that of an equal-half sharing arrangement, with the exception that the main farmer will be positioned to receive an equal share of the profit with the sharecrop broker and investor. The sharecrop broker, investor, and the main farmer divide the profit equally and then share it with their respective side parties (see, Figure line 2 above). The one-third share arrangement gives an investor more advantages than the previous form while narrowing the landowner’s share margin even further. In this case, the investor makes a more significant profit because he keeps his original share and does not have to divide it further with any other actor. As a result, to maximize profit, investors always insist on concluding such types of contractual arrangements. Furthermore, the direct and one-third sharing is similar to indirect sharing, except that the sharecrop broker does not participate.

Furthermore, the investors have contracted more irrigated land to expand their production, contributing to more wealth accumulation. For example, as the former district land administration head noted, he knows an investor living in the capital city, Addis Ababa, who has sharecropped more than 60 kert (equivalent to the ownership of more than 20 households) from afar. This case indicates an extended capitalist reproduction involving large-scale production while depriving more than 20 households of the benefit of their land, which they should earn exclusively. This process exemplifies the production relationship, which Li (Citation2014) also observed in her study in Indonesia, where a few highland farmers increased their capital formation through increased productivity by controlling more land at the expense of many other households who could not compete in the process.

In the presence of brokers, landowners not only share a tiny portion of the benefit in the production relationship but are also rendered invisible, passive, powerless, and voiceless on issues about their land. A broker is the first point of contact and participates in a profit-sharing arrangement with the investor, then divides half of the cash profit with the landowner from what he received. The landowner is silenced and marginalized on his own irrigated land. Any direct claim or complaint the landowner makes to an investor and/or his side parties (main farmer and field farmers) during the production is not appreciated or welcomed. It is because the landowner is considered illegitimate and can only do so indirectly through a broker. The investor may not even know or wish to know who the actual landowner is.Footnote7 Nonetheless, they ensure that they receive the lion’s share of profit in production relations.Thus, the sharecropping relations in the project area are exploitative to landowners but beneficial to investors, contributing to wealth accumulation.

6.1. The commodity marketing (this has to be numbered 4.2.)

Producers (landowners/sharecrop brokers, investors, and main farmers), a chain of marketing brokers, traders, and transporters are involved in the local sales of cash crop products. The overall marketing chain also operates in a way that further exploits the landowners and undermines and weakens their negotiating and decision-making power. It primarily favours investors, who are networked with traders and brokers and are informally organized alongside vegetable commodity marketing. It is also strengthened by the fraudulent acts of brokers and their associates, who desire to maximize profit at the expense of both sharecrop landowners and a few entrepreneur landowners who are independently engaged in cash crop production. This exploitation process is evident in overall marketing strategies, market price determination, and the harvesting and loading of produce, as explained below.

7. Marketing strategies (this to be numberd 4.2.1.)

The chain of mediators identifies the onions ready to harvest, facilitating and connecting producers to the local traders and sometimes to wholesalers in the central market. These mediators are interconnected in hierarchies and subdivided based on their specific functions in the chain. They facilitate the marketing process and receive a commission, which reduces the share of pastoral landowners because this is considered a cost of production and is refunded to investors at the end. According to the information from FGD with cooperative members, these mediators commonly include locators, medium brokers, and big brokers. The locator is a local individual, often a young person, who actively roams to identify the onion fields ready for harvest and immediately informs the village’s medium broker. The medium broker is also a local individual with good connections to the big brokers in urban areas. He may has many locators under him who scout for onions ready to harvest and provide him with information. He may also speak to the landowner or sharecrop broker (if required) and report to the big broker, who often deals on the selling price with parties involved in the production.

The big broker is based in nearby urban centres and maintains frequent contact with traders and occasionally wholesalers in vegetable marketing centres such as Adama and Addis Ababa. He organizes and hires daily labourers, who usually come from nearby urban areas for their harvesting expertise, and he deals with trucks to deliver the onions to the markets. He is a point of contact to cover the costs of arranging, packing and loading the harvest on behalf of the traders or wholesalers. He also makes the other necessary upfront payments, such as the commission for the locator and the medium broker.

8. Market price determination (this has to be numbered 4.2.2.)

The price is not, as such, negotiable between the traders and the parties involved in the production relationship. Instead, it is predetermined and fixed by market brokers who closely consult with traders and wholesalers and, implicitly, with sharecropping investors, as informantsFootnote8 explained. The landowner or sharecrop broker is asked to accept the price offer made to him as an order. Because of their networks and market information at the buying node, market brokers are influential and wield significant power in determining the selling price (Ndukai, Citation2015). They often benefit “from the knowledge gaps” (Bräuchler et al., Citation2021, p. 5).

According to the District Irrigation Officer, landowners do not have direct access to information about market conditions, and they do not know where to sell, whom to sell to, and when and at what price to sell their products. In support of this, a young agro-pastoralist in Illala village stated, “Even though the price is unfair, I do not know whom I should call to cross-check the price.” As a result, the local landowners are powerless to negotiate and agree to accept the price offer made to them. It was claimed that if the offered price was refused, the market brokers conspired to ensure that the product was not sold on time and was delayed on the field. Thus, they could buy it at a lower price in the following days than was initially proposed due to the perishability of the produce. According to Bewuketu et al. (Citation2016) and Tesfaye (Citation2021), the perishable nature of the produce, combined with a lack of storage facilities, forced producers to sell their produce at a lower farm gate price.

Furthermore, it was claimed that big brokers and traders have been using implicit and explicit strategies to discourage and prevent local agro-pastoralists from selling their produce directly in the central market. This strategy includes negotiating with chairs of labour cooperatives and transporters to either not provide their respective services to agro-pastoralists wishing to sell their produce to the market directly or to charge them a higher price than usual. There was also a time when traders from Metehara town (the district capital) opposed entrepreneurial agro-pastoralists selling their produce directly to the central vegetable market. According to local informants and the District Irrigation Officer, the traders accused the organized agro-pastoralists of attempting to transport their onions to sell in the central market, pointing out that the farmers do not have a trade licence and thus are not authorized to sell the produce. They also stressed that the act jeopardizes the livelihoods of tax-paying traders who already have a licence and are in the business.

The price offered at the farm gate usually varies from village to village and even within a village. It is generally low and fluctuating but always to the benefit of mediators and their connections (Tesfaye, Citation2021). A statement from the vice regional State Agriculture and Irrigation Bureau confirmed this, saying, “We are aware, but working on it, that the market system has a problem in which traders and brokers purchase onions at a lower price and make a higher profit, sometimes more than 200 per cent.”

The sharecrop investors, the informants claimed,Footnote9 are either traders by themselves or have long hands in establishing relationships with individuals or groups. They have created a good network with actors such as vegetable marketers at central and large markets, labourers, transporters, government officials, and others, whom they believe are essential in maintaining and protecting their benefits. They benefit from being implicitly involved in price-setting in at least two ways. First, because of long-term business relationships with brokers and traders that are in their favour, sharecrop investors deal with higher prices while offering lower prices to local landowners or sharecrop brokers. This allows the market brokers to keep the difference and share it later with the investor. Second, as mentioned, sharecropper investors are often traders, but they indirectly send brokers to bargain for a lower price. The tragedy is that even though local landowners/sharecrop brokers suspect that a sharecropper investor may cheat on the selling price of onions, many are afraid to talk to and confront him explicitly. They have even lost confidence in calculating and requesting detailed explanations about production costs. It is partly due to apprehension that the sharecropper will decline his agreement during the following cropping period or because they may not keep farm expense records to compare because they may lack the knowledge to do so (Bekele & Padmanabhan, Citation2012).

9. Harvesting and loading of the produce (this has to be numbered 4.2.3.)

The harvesting phase involves uprooting, collecting, and cutting the top part of the onion leaf, while loading includes filling the onion into containers (packing) and weighing and putting it on the trucks for transport. Many individuals, both outsiders and locals, are proletarianized and engaged in these activities for a wage, reinforcing the capitalist production relation. The daily labourers for harvesting are usually brought in from nearby urban areas for their expertise. They are directly organized by the big brokers who deal with the representative of a given labour cooperative providing such a service. In contrast, local pastoral fellows provide labour for loading activities. As a result, many active (agro-)pastoral landowners and their families rely on this wage after contracting out their land.

Some five years back, in all the study villages, there were cooperatives organized by local individuals and engaged in daily labouring activities for packing and weighting, loading, and other activities such as picking up spilt onions and refilling them into containers. These organizations were formed by landless people and by people who own land but also earn money through daily labour. At that time, the cooperative organized labour and determined and fixed the fee that they charged for the services provided by their respective groups. Later, the cooperative was disorganized, but an increasing number of local pastoralists and their family members continued to be proletarianized, engaging in labour activities for less pay on an individual basis.

Furthermore, during the harvesting and loading process, landowner pastoralists in the study area have been deprived of their benefits due to weight cheating by brokers and their affiliated sharecrop investors (Tesfaye, Citation2021). Local pastoralists and District officials claimed that traders sent fake calibrated scales to their brokers to defraud an extra kilo of onion. It was also observed when the already loaded product at the village during the day was unloaded, reweighted, and repacked at night in town before being delivered to the central market. For example, some private individuals and organized groups in Illala village attempted to provide weighting services with well-calibrated scales. However, the brokers were frequently unwilling and rejected the scales brought by locals. Instead, they insisted on using their scales. In this regard, the village leader in Illala shared an experience that one of the villagers had:

… three days ago, brokers came to buy his produce using a forged calibrated scale, but he refused, instead requesting that they use the appropriate scale that he provided. They refused and changed the scale for the second time in case he did not like the first one. Then he resisted for a while longer, but in the meantime, he accepted because he had no other choice (interview with the village leader, March 2021).

9.1. Analyzing the production relationships (this has to be numbred 4.3.)

The overall sharecropping process and related production and marketing relationships in the Project area are based on unequal power and bargaining relationships between landowners and their counterpart sharecropper investor/s. It reflects the form of a capitalist mode of production in which investors have maximized at the expense of landowners.

The capitalists who own and control the means of production put labour power into production processes, resulting in surplus value, which ultimately forms capital accumulation (Bin, Citation2018). In this process, the sharecrop investor is granted temporary land access rights during his contractual period to invest in and enjoy the benefit of the land. He gains and maximizes his benefit from the process, both explicitly by taking the upper hand in sharing and implicitly by engaging in fraudulent acts (Buli, Citation2006). The other actors have also contributed to the sustenance of capitalist production relations and capital accumulation while squeezing a benefit from the land, narrowing the landowners’ benefit margin. Local sharecrop brokers, for example, have provided security protection for outsiders involved in production, which is critical for external capitalists to have confidence in entering into production relationships. The provision of security protection is one of the key responsibilities of the brokers that the non-local investors would like to emphasize to enter into a deal.

Moreover, labourers from all walks of life sell their labour power and are subordinated to capitalists in exchange for a wage from farming activities. The pastoralist landowners and their family members, notably children and women, turned to “proletarianization” by providing farming labour services, though the “degree of proletarianization” (Bin, Citation2018, p. 83) is limited but on a growing trend (Ayalew et al., Citation2016). This is one of the futures of the capitalist production relation (Sanyal, Citation2014).

In this case study, however, capital formation does not involve either pastoral land confiscation or the transfer of ownership rights involving unreversed dispossession, as argued in Marx’s theory of primitive accumulation and the works of contemporary Marxists such as Harvey. For example, Harvey argued that dispossession is necessary for accumulation and the continuation of capitalist-dominated social formations in which wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a few (Harvey, Citation2003, Citation2010). This dispossession could be coercive and violent (Batou, Citation2015; Gogoi & Saikia, Citation2020; Harvey, Citation2003). However, the production relationship and capital formation in the Project area occurred without dispossessing the pastoral land or expelling the pastoralists from their land. Shrimali (Citation2016) noted that contract farming between farmers and big industries in Punjab, India has resulted in capital accumulation without requiring the big companies to dispossess farmers directly from their land to profit. Instead, the accumulation occurred without dispossession but resulted from increased productivity associated with effective production endeavours (Shrimali, Citation2016). Paudel (Citation2016) also observed that the community forest in Nepal had reproduced a condition of accumulation without dispossession, in which ownership over communal forestland is secured and capital accumulation through commercialization occurs concurrently.

In an echo of these, the production relations in the study area depicted the very process of accumulation without dispossession, where land ownership rights remained in the hands of (agro-) pastoralist landowners, who are primarily granted tenure rights. However, the lion’s share of profit from the land goes to capitalist investors. As already stated, the locals are constrained due to systemic structural and relational issues that weaken their ability to access their land and independently derive exclusive benefits from it. This creates a condition and obligates them to enter into an unbalanced contractual agreement with capital owners, whose wealth offers them the power to access (Peluso & Ribot, Citation2020; Ribot & Peluso, Citation2003; Teshome et al., Citation2021). In such a situation, capitalists organize labour and resources to convert the land into productive space, from which they quickly reap huge profits at the cost of the landowner, who benefits only marginally from the relationship. Thus, capital formation is not the result of the confiscation of physical land but of benefit and labour exploitation by capitalists and their associated networked actors from pastoral landowners who enter into unfair production processes and marketing due to compelling systemic constraints.

10. Conclusion (this has to be numbered 5)

The Project has expanded crop cultivation and resulted in a new form of economic relationships and interactions over land. Land distribution linked to the Project and the conversion of communally owned grazing land to private tenure for individual use has given the owners more decision rights and involvement in land transactions such as sharecropping. It accelerates the commodification of pastoral lands and the evolution of various actors seeking to engage in crop production (Ashami & Lydall, Citation2021; Bassett, Citation2009). In this Project, the state has envisioned pastoral development through settled agriculture. However, the pastoral context, including the households’ ability to produce crops and other variables determining the nature of the outcomes, has been taken for granted (Bekele & Padmanabhan, Citation2012; Kassahun, Citation2006). As a result, the benefit gained by many pastoralists from the “new project” endeavour remains marginal.

Given the disadvantaged positionality of pastoralists and agro-pastoralists (Markakis, Citation2011; Regassa, Citation2021), many landowners have earned less and are also being exploited due to the increasing and intensified sharecropping contracts in the project area. Except for entrepreneurs, many landowners do not often produce primarily cash crops independently, and as a result, they do not reap the full potential benefit from their irrigated land. They enter into a sharecropping agreement in which multiple actors participate, each receiving shares at the expense of the landowner, who earns a small dividend.

Further, the landowners and their household members are being deprived of their labour power with increasing involvement in wage employment created in the production process. This overall production relationship reinforces wealth and capital accumulation for investors. Therefore, many landowners are still disadvantaged as they can no longer use their land for cattle grazing as in the old days, as it has been converted to cropping fields. Nor are they able to reap the full financial benefits of irrigation as in the “modern” days, as it has been taken away by a network of actors for whom it opens up new doors of exploitation to make a profit at the expense of the locals. This suggests a policy implication aimed at strengthening households’ capacity to ensure that local pastoralists can independently farm on their land and reap the full benefits of their land. In line with Abdi’s (Citation2015) and Fekadu’s (Citation2014) recommendations, this includes, among other things, interventions on market infrastructure, credit access, agricultural input provision, and skill training and experience sharing.

Finally, this study uncovers production practises in lowland areas related to the irrigation project, representing dynamism in tenancy arrangements, and shows how this arrangement depicts capitalist production relations and contributes to the study of capital accumulation without dispossession. Despite its significant contribution, it is limited in that it lacks quantifiable evidence indicating the proportion of pastoralist landowners engaging in sharecropping contracts, making it difficult to estimate the magnitude of production relationships involving land deals and transactions related to the Project.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Zurich University Political Geography Group (PGG) for their valuable feedback on an earlier draft. We are also grateful to Shona Loong (PhD) for her insights and comments on the revised version of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tefera Goshu

Tefera Goshu is a lecturer in the department of Sociology at Ambo University, Ethiopia. He is also a PhD candidate in the Department of Social Anthropology at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia. His project focuses on the interplay of the political economy of irrigation and pastoral development. His other research interests include rural development, food security, gender, social inequality, adolescents and youth, and socio-cultural change.

Ayalew Gebre

Ayalew Gebre (PhD) is an Associate Professor of Development Studies in the Department of Social Anthropology at Addis Ababa University. He conducted extensive research on the issues of pastoralism and pastoral development, resource-based conflict and conflict management in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Ethiopia and the Horn. His other research interests include social assessment of rural and urban development programs; violence; sexual abuse and exploitation of women and children; child and child welfare; and migration and forced displacement.

Notes

1. Previous large-scale projects in the area, such as Metehara Sugar Estate and Awash National Park, for example, confiscated over 70,000 hectares of dry grazing land, depriving locals of economic resources and forcing them to flee their homes (Buli, Citation2006).

2. 0.75 hectare (3 kert) for a household and 0.25 hectare (1 kert) for young people (boys and girls). The local land measuring unit is called a “kert,” and one kert equals 0.25 hectares.

3. Interview with the head of the woreda land administration.

4. Interviews with a local pastoralist in a downstream village who has been struggling to find sharecropping investors; an elder pastoralist in an upstream village; and a village chair in the downstream village.

5. Interview with a young man from the downstream village

6. FGDs with elders in upper and downstream villages.

7. Interview with an elder pastoralist from the downstream village.

8. FGD with girls involved in agriculture product sales.

9. FGDs with old men at Illala and Gidara villages.

References

- Abdi, E. (2015). Determinants of agro-pastoralists’ participation in irrigation scheme: The case of fentalle agro pastoral district, Oromia regional State, Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Research, Innovation and Technology, 5(2), 44–16. https://doi.org/10.3329/ijarit.v5i2.26269

- Ashami, M., & Lydall, J. (2021). Persistent expropriation of pastoral lands: The afar case. In E. C. Gabbert, J. G. Fana Gebresenbet, & G. Schlee (Eds.), Lands of the future (pp. 144–164). Berghahn Books.

- Ayalew, G. (2001). Pastoralism under pressure: Land alienation and pastoral transformations among the Karrayu of Eastern Ethiopia, 1994 to the present. Shaker Publishing.

- Ayalew, G., Mamo, H., Tegegne, G.-E., & Kiya, G. (2016). The dynamics of land transactions in selected agricultural and agro-pastoral woredas of afar, Oromia and SNNP National Regional State of Ethiopia. Institute of Development and Policy Research, Addis Ababa University.

- Bassett, T. J. (2009). Mobile pastoralism on the brink of land privatization in Northern Côte d’Ivoire. Geoforum, 40(5), 756–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.04.005

- Batou, J. (2015). Accumlation by dispossession and anti-capitalist struggles: A long historical perspecive. Science & Society, 79(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2015.79.1.11

- Bekele, H., & Padmanabhan, M. (2012). The transformation of the afar commons in Ethiopia: State coercion, diversification, and property right change among pastoralists. In M. Esther, M. Helen, & M.-D. Ruth (Eds.), Collective action and property rights for poverty reduction (pp. 270–303). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bewuketu, H., Tsegaye, B., & Awalom, H. (2016). Constraints in production of onion (Allium cepa L .) in Masha District, Southwest Ethiopia. Global Journal of Agriculture and Agricultural Sciences, 4(2), 314–321.

- Bin, D. (2018). So-called Accumulation by Dispossession. Critical Sociology, 44(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516651687

- Bräuchler, B., Knodel, K., & Röschenthaler, U. (2021). Brokerage from within: A conceptual framework. Cultural Dynamics, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/09213740211011202

- Buffavand, L. (2016). ‘The land does not like them’: Contesting dispossession in cosmological terms in Mela, south-west Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10(3), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2016.1266194

- Buffavand, L. (2021). State-building in the Ethiopian South-Western Lowlands. In E. C. Gabbert, F. Gebresenbet, J. G. Galaty, & G. Schlee (Eds.), Land of the Future: Anthropological perspectives on pastoralism, land deals and tropes of modernity in Eastern Africa (pp. 249–267). Berghahn Books.

- Buli, E. (2006). The socio-economic dimension of development induced impoverishment: The Case of the Karrayu Oromo of the Upper Awash Valley [Social Anthropology Dissertation Series No. 12.]. Addis Ababa University.

- Carr, C. J. (2017). River basin development and human rights in Eastern Africa — A Policy Crossroads. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50469-8

- CSA. (2008). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census.

- Deininger, K., Ali, D. A., & Alemu, T. (2011). Impacts of land certification on tenure security, investment, and land market participation: Evidence from Ethiopia. Land Economics, 87(2), 312–334. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.87.2.312

- Devereux, S. (2010). Better marginalised than incorporated? Pastoralist livelihoods in somali region, Ethiopia. European Journal of Development Research, 22(5), 678–695. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.29

- Fekadu, B. (2014). The challenges to pastoral transformation to sedentary farming: The case of Karrayyu pastoralists. In G. Mulugeta (Ed.), A delicate balance (pp. 66–91). Institute of Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- Gebresenbet, F. (2021). Villagization in Ethiopia’s Lowlands: Development vs. Facilitating control and dispossession. In E. C. Gabbert, F. Gebresenbet, J. G. Galaty, & G. Schlee (Eds.), Land of the Future: Anthropological perspectives on pastoralism, land deals and tropes of modernity in Eastern Africa (pp. 210–230). Berghahn Books.

- Girum, G. (2013). Localized adaptation to climate change: Pastoral agency under changing environments in dry land parts of upper awash valley, Ethiopia [PhD dissertation]. Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies.

- Gogoi, N., & Saikia, N. K. (2020). Critical review on David Harvey’s “The new imperialism: accumulation by dispossession”. Annals of R.S.C.B, 24(2), 1161–1164. https://annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/9779

- Harvey, D. (2003). Accumulation by dispossession. In The New Imperialism (pp. 137–182). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199264315.003.0007

- Harvey, D. (2010). A companion to marx’s capital. Verso.

- Kassahun, B. (2006). Review of policies pertaining to pastoralism in Ethiopia. In B. Kassahun & F. Demessie (Eds.), Ethiopian Rural development Policies (pp. 71–87). Addis Ababa University.

- Khai, L. D., Markussen, T., McCoy, S., & Tarp, F. (2013). Access to land: Market and non-market land transactions in rural Vietnam. In S. T. Holden, K. Otsuka, & K. Deininger (Eds.), Land tenure reform in Asia and Africa (pp. 162–186). Palgrave.

- Li, T. M. (1999). Compromising power: Development, culture, and rule in Indonesia. Cultural Anthropology, 14(3), 295–322. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1999.14.3.295

- Li, T. M. (2007). The will to improve: Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics. Duke University Press.

- Li, T. M. (2014). Land’s End: Capitalist relations on an indigenous frontier. Duke University Press.

- Luxemburg, R. (2003). The accumulation of capital. Routledge.

- Markakis, J. (2011). Ethiopia: The last two frontiers. James Currey.

- Mekonnen, A., Mohammed, A., Poshendra, S., & Budds, J. (2020). Villagization and access to water resources in the middle awash valley of Ethiopia: Implications for climate change adaptation. Climate and Development, 12(10), 899–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1701973

- Mukhamedova, N., & Pomfret, R. (2019). Why does sharecropping survive? Agrarian institutions and contract choice in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Comparative Economic Studies, 61(4), 576–597. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-019-00105-z

- Nandy, A., & Visvanathan, S. (1990). Modern medicine and its non-modern critics: A study in discourse. In F. A. Marglin & S. A. Marglin (Eds.), Dominating knowledge: Development, culture, and resistance (pp. 145–184). Oxford University Press.

- Ndukai, M. (2015). Onion price change and brokers role: Challenges and opportunities: Case study ruvu remit division in simanjiro district, Tanzania [MA thesis]. Open University of Tanzania.

- Oromia Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise. (2009). Fentale irrigation based integrated development project: SocioeconomicStudy final report. OWWDSE, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Oromia Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise. (2011). Fentale irrigation based integrated development project: Study and design project final report. OWWDSE, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Paudel, D. (2016). Re-inventing the commons: Community forestry as accumulation without dispossession in Nepal. Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(5), 989–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1130700

- Peluso, N. L., & Ribot, J. (2020). Postscript: A Theory of Access Revisited. Society and Natural Resources, 33(2), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1709929

- Pertaub, D. P., & Stevenson, E. G. J. (2019). Pipe dreams: Water, development and the work of the imagination in Ethiopia’s lower Omo Valley. In Nomadic Peoples, 23(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.3197/np.2019.230202

- Regassa, A. (2021). From Cattle Herding to Charcoal Burning: Land Expropriation, State Consolidation and Livelihood Changes in Abaya Valley, souther Ethiopia. In E. C. Gabbert, F. Gebresenbet, J. G. Galaty, & G. Schlee (Eds.), Land of the Future (pp. 189–209). Berghahn Books.

- Reta, H. (2018). Water Security in the Wash Basin of Ethiopia: An institutional analysis [PhD Dissertation]. Addis Ababa University.

- Ribot, J. C., & Peluso, N. L. (2003). A Theory of Access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x

- Sanyal, K. (2014). Rethinking capitalist development: Primitive accumulation, governmentality and post-colonial capitalism. Rethinking Capitalist Development: Primitive Accumulation, Governmentality and Post-Colonial Capitalism. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315767321

- Shrimali, R. (2016). Accumulation by dispossession or accumulation without dispossession: The case of contract farming in India. Human Geography(United Kingdom), 9(3), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861600900306

- Stevenson, E. G. J., & Buffavand, L. (2018). Do our bodies know their ways? Villagization, food insecurity, and ill-being in Ethiopia’s lower omo valley. African Studies Review, 61(1), 109–133. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2017.100

- Tesfaye, T. (2021). Determinants of onion commercialization among smallholder farming households’: The case of fentale district, east shoa zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia [MA thesis]. Ambo Unversity.

- Teshome, B. L., Arega, B. B., & Mehrete, B. F. (2021). Effects of the current land tenure on augmenting household farmland access in south east Ethiopia. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00709-w

- Tsion, B. (2011). Sedentarization: A means to promote the right to food, health and education: The case of Karrayu pastoralists of eastern Ethiopia [MA thesis]. Addis Ababa University.

- Turton, D. (2021). ‘ Breaking every rule in the book ’ th e story of river basin development. In E. C. Gabbert, F. Gebresenbet, J. G. Galaty, & G. Schlee (Eds.), Land of the Future: Anthropological perspectives on pastoralism, land deals and tropes of modernity in Eastern Africa (pp. 231–248). Berghahn Books.

- Yihunbelay, T. (2020). Living on the ‘Margin’: Livelihood strategies in the changing social-ecological systems of the upper course of wabe shebelle river among the Dube (Bantu), Ethiopia [PhD Dissertation]. Addis Ababa University.