Abstract

This article investigates the challenges faced by women on Madura Island, East Java, Indonesia in obtaining property rights, particularly in regards to land ownership. In Madurese society, land ownership rights have been largely awarded to male offspring. The study used a constructivist perspective and data from field observations, interviews, document analysis, and literature review to examine how power is perpetuated in Madurese society through cultural norms. The results show that these challenges are rooted in cultural construction that leads to unjust treatment of women within the family. The dominance of patriarchy in Madurese culture has created additional difficulties for women, who are already responsible for managing domestic affairs. Despite their crucial role in the family, the ongoing discrimination against women in obtaining property rights has a significant impact on their future, as they are forced to rely on men. The cultural construction that shapes the treatment of women in Madurese society continues to restrict their independence.

1. Introduction

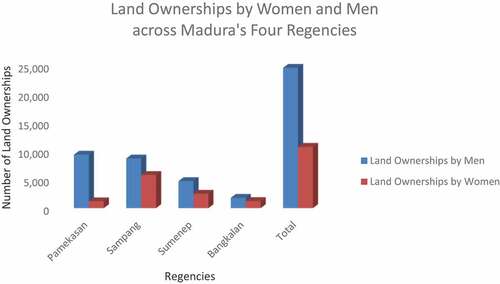

Women in Madura, Indonesia often struggle to obtain land due to uneven access. In terms of inheritance, women are more likely to inherit land if they are the only daughter or part of a group of sisters, but a male heir is typically responsible for distributing the inheritance if there are both daughters and sons in the family. This can make it difficult for women to obtain land through inheritance. One of the families investigated by this study has one daughter and six sons; the daughter is the eldest child, but her gender disqualified her from inheriting a part of the family’s land. Such cases are prevalent in Madurese society and have existed for a long time. According to data from 2021, in Madura’s four regencies, there were 18,704,470 land ownerships by men compared to only 33,283 land ownerships by women. Due to the dominance of the patriarchal system in Madurese society, cultural construction tend to take precedence over aspects of justice, enabling the continuance of this practice (Pattiruhu, Citation2020). Up to this point, there are three main themes in the research on the challenges faced by women. The first theme involves studies that demonstrate the ongoing disadvantages that women experience within their families, such as limited ownership rights to just a home in which to live and being responsible for domestic tasks (Isti’anah, Citation2020; Marwinda et al., Citation2020; Sumaryati, Citation2018). The second theme involves research on the disadvantages women face in inheritance matters (Alfarisi, Citation2020; Arba et al., Citation2020; Taqiyuddin, Citation2020). The third theme involves studies that show a shift in perceptions of women’s roles in public spaces (Indarti, Citation2019; Suarmini et al., Citation2018; Zuhdi, Citation2019). Despite these three trends, research on the impact of injustice on Madurese women’s rights to own land as an economic resource has not been extensively examined. This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing the injustices that Madurese women face in terms of access to land ownership.

This report aims to address the lack of attention given to the impact of injustice on Madurese women’s rights to own land as an economic resource in previous studies. It addresses three main points: the cultural construction of women in Madurese society; the factors that contribute to discrimination against women in terms of land ownership on Madura; and the effects of this injustice on the lives of Madurese women.

This study suggests that the inequality faced by Madurese women in terms of land rights is a result of societal views on women’s place in relation to ownership of possessions. Madurese women are only allowed to own a home to live in, while men have the right to inherit other movable and immovable property. Even being the oldest daughter does not change a woman’s cultural status as someone who is not entitled to ownership of land. As cultural influences that support this discriminatory treatment have increased, Madurese women have become more reliant on men.

2. Literature review

2.1. Cultural construction

Construction, in this context, refers to a social concept that is closely connected to the human mind (Franks, Citation2014). This aligns with Haslanger’s (Citation2017) assertion that ideas that originate from mental processes are societal constructions with strong ties to social and intellectual history. Through the mind, knowledge is created and becomes the result of a series of symbolic interactions that shape cultural reality (Karman, Citation2015). Haryono (Citation2016) agrees with Tilaar that culture is created by humans and vice versa; the culture that people create influences their lives. There is a reciprocal relationship between humans and culture, which impacts the individuals who experience it (Haryono, Citation2016). Furthermore, cultural construction occurs continuously throughout the process and is not restricted to early formation alone (Mesquita et al., Citation2016). Therefore, it is closely related to the changes that are inherent to culture itself (Trubshaw, Citation2011). However, these changes have limits; long-standing cultural constructions in any society cannot be easily altered (Pratiwi et al., Citation2020).

One of the most challenging cultural constructs to change is gender bias. Many gender notions are based on fictional stories that are socioculturally manufactured to legitimize gender reality, which is influenced by the power of the dominant group in a cultural community (Haslanger, Citation2017). This shows how certain interests can appropriate and exploit cultural construction (Muktiyo, Citation2015). In the context of gender, patriarchy refers to a culture that favors men by creating gender imbalance (Sakina & A, Citation2017). The cultural constructions created by male domination in communities portray women as submissive, weak, and dependent (Sakina & A, Citation2017). Gender inequality not only occurs in the home but also persists in public settings, such as when it comes to property ownership, where women’s access and influence are limited (Akinola, Citation2018). A concrete example is India’s land leasing registration process, which led to a higher male child survival rate (Bhalotra et al., Citation2019). In this context, Indian culture establishes ideals that elevate the status of boys because they are land heirs (Bhalotra et al., Citation2019). It is important to address this form of gender inequality.

2.2. Gender inequality

In anthropology, gender is not just a classification based on biological sex, but also includes other factors such as social class and age (Boe, Citation2015). Despite being a non-essential category that can change depending on cultural construction (Septiadi & Wigna, Citation2015), Lindqvist et al. (Citation2021) argues that gender has several important aspects, namely physiology, identity, legal distinction, and social distinction that determines how to behave according to gender norms and expression. These aspects cannot be separated from inherited cultural constructions that have propagated gender myths and stereotypes, such as generalizations and prejudices about the binary classification of male and female qualities (Heilman, Citation2012; Roof, Citation2015). This differentiation is then used to form opinions about what is appropriate for men and women (Ellemers, Citation2018). Past research has shown that such cultural constructions of gender are often unequal, as demonstrated by studies by Greenberg and Greenberg (Citation2020), Van Der Pas and Aaldering (Citation2020), İncikabı and Ulusoy (Citation2019), and Atir and Ferguson (Citation2018). Gender disparity is therefore something constructed by culture, particularly by people with influence in their cultural community.

The problem of gender inequality has significant effects on many parts of human existence, especially for women. Women’s independence, access to education, and employment opportunities, for instance, are constrained (Branisa et al., Citation2013). Similar to this, women are frequently seen as the party carrying the higher burden in other spheres of life, such as politics and the economics, particularly in instances where access to resources are involved (Sitorus, Citation2016). A research by Daytana and Salmun (Citation2021) on the availability of potable water in Central Sumba lends credence to this claim. Despite being given limited access to it, the women there must provide clean water. In the context of land ownership, land snatching is a practice that frequently perpetuates gender inequality, showing a disregard for women’s rights (Levien, Citation2017). Women’s vulnerability is rendered worse when their access to crucial resources is restricted, whether due to cultural norms or discriminatory government management mechanisms (Tantoh et al., Citation2021). The fact that food security and livelihoods become stable when women’s access to land ownership and their participation in decision- making are taken into account, however, demonstrates that gender inequality does not simply impact women (Tantoh et al., Citation2021).

2.3. Access to land

Land is a source of life that is vital for the growth and well-being of individuals and societies (Mahfiana, Citation2016). It is therefore important to consider access to land. According to research by Muraoka et al. (Citation2018), access to land directly impacts rural households’ ability to earn a living and produce food, illustrating the connection between welfare and access to land. The theory of Ribot and Peluso (Hafidh & Krisdyatmiko, Citation2020) explains that access refers to the ability to benefit from something that can be controlled, whether it be property, a human resource, or an institution. Access is therefore related to power rather than ownership, as those in positions of authority can profit from something even if they do not own the resources (Hafidh & Krisdyatmiko, Citation2020). When it comes to land, access is not just about who owns the land, but also about who has power over it and how they have that power.

There is a persistent disparity in land access between men and women from a gender standpoint (Akinola, Citation2018; Joshi, Citation2020; Levien, Citation2017). Women are consistently disadvantaged by systems of land production and reproduction established by dominant powers (Tsikata, Citation2016), which are manifested in administrative procedures and legal property ownership and to which women have significantly less access than men (Mahfiana, Citation2016). Additionally, women’s access to land is hindered by the conversion of land to commercial usage (Ndi, Citation2019). This impacts women’s well-being, particularly in terms of their limited livelihood options (Tsikata, Citation2016). Unfortunately, as this study will show, gender disparity in land access is also a cultural construction. Akinola (Citation2018) argues that patriarchal views that deny women land ownership have perpetuated gender inequality in Africa, making it challenging to grant women land rights when cultural factors are taken into account.

3. Methodology

This study was conducted in four regencies on the Indonesian island of Madura in East Java. The location was chosen due to the ongoing unfair land ownership practices in Madurese society. Qualitative data was collected through observation, interviews, and a review of documents and literature and served as the foundation of the study. Observations of current land rights transfer practices were made in both rural communities with lower levels of education and in more urban areas. The focus was on multi-child households, specifically those with both female and male children, in order to better understand the social practice of transferring property rights to offspring (heirs) through inheritance.

In addition to observations, data was collected through interviews with 13 informants who represented different age ranges, genders, occupations, positions, and educational backgrounds and had a range of knowledge about land transfer processes in Madura. The selection was also based on their Madurese ancestry and expected general understanding of Madurese culture. The questions asked of the informants related directly to inheritance transfer patterns, the transfer procedure, and the likelihood of daughters inheriting land from their parents. The information obtained included statements about discriminatory practices against women in Madurese society. Some informants with more expertise were asked more detailed questions, although certain questions were repeated.

Furthermore, a review of relevant documents and literature was conducted to supplement the analysis. The data from the documents is presented as the proportion of land owned by men and women, supported by letters of land ownership bearing their names. According to data from the regional government office, Madurese men own significantly more land than Madurese women. The literature review was conducted in a systematic manner by mapping literature that was relevant to the main issue being examined in this research. It not only supported the arguments in this paper but also established that the focus of this study differed from previous studies.

The data collected through these approaches was initially mapped according to their respective trends. It was then categorized into three groups based on the repeated questions. The first category illustrates the cultural construction of women’s position in Madurese society. The second category highlights the disparity in land ownership between Madurese women and men. The third category presents an overview of the effects of Madurese women’s unequal access to land ownership. The data was then interpreted by providing context before being organized into this article. This set of steps was a crucial part of the overall data collection and article writing process.

4. Findings

4.1. Women’s positions in Madurese culture

Madurese women occupy a peculiar cultural position in Madurese society. A woman’s crucial roles as a mother and wife who administers the household are respected. Madurese society regards women as family members who must be protected and maintained; men strive for the well-being of the women in their families in order to cultivate their own self-esteem in front of society. Women are placed in a sacred space separate from the sphere of males. This reality is viewed as a social phenomenon in which religion serves as a doctrine that directs people’s behavior within the framework of culture. As a result, many Madurese customs are also based on religious beliefs. Religion becomes the basic foundation of Madurese social, cultural, and economic activities—the social bonds between people, and this affects the position of women in various ways. Kyai Haji Maskur, a 50-year-old Madurese religious leader, stated:

Madurese women are highly respected and serve as a symbol of prosperity in the home; if women are cared for and respected, the family will prosper. Indeed, Madurese women are relegated to the kitchen, the well (laundry), and the bed. However, for kitchen and laundry matters, the women do not have to do everything themselves; they can act as managers or directors, directing people or santri (Islamic boarding school students) to complete the tasks.

Women have played significant roles throughout Indonesian history. Teuku Malahayati, for example, was the commander of the Aceh naval force in the seventh century. In addition, five of Acehnese crowned rulers were female. The Melayu Kingdom had a female monarch ruler as well. It can be seen that historically women have had power and a very strategic position as well as women in Madurese society. According to Hajjah Noer, a 70-year-old traditional Madurese woman figure:

Madurese women are strong and respected. They are highly regarded in the home by both the husband and the children, and they play a role in dividing household chores and making household decisions. As wife and mother, they are also in charge of the household’s finances.

I was untiring in taking care of my nine children. Alhamdulillah (all praise is due to Allah), my children were all able to finish their education and get jobs without me spending a lot of money. My children have grown up to be obedient and modest.

In our family, each daughter received a house to live in as well as the right to the land (where the house stands). However, we do not get any land in the form of rice fields or yards — no plot other than those on which the houses are built. Here, it is (also) part of our tradition that women return to their parents’ homes (after marriage).

No verbal or written work division is required. As a housewife, my duty is to take care of the house by doing washing, cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the kids, while my husband is in charge of making a living.

In Madurese society, a man who performs domestic tasks may be referred to as sial, which translates to “unlucky.” Despite societal changes, this cultural norm persists. Madurese community leader Haji Sofa, 50, said:

The wife is in charge of cooking and taking care of the house and kids. Husbands aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen and dry their wives’ clothes. If this happens, the husband has lost to his wife and is sial. A husband has to work to support his wife.

4.2. Inequality in land ownership rights between men and women in Madura

Article 9 paragraph (2) of the Basic Agrarian Principles (UUPA) establishes the legal equality of men and women in terms of land ownership, stating that male and female Indonesian citizens have equal rights to own and utilize land for themselves and their families. However, information gathered from randomly selected villages across the four districts of Madura revealed the following:

4.2.1. Madurese women’s rights pertaining to house ownership

The unequal distribution of land rights among Madurese women can be attributed to several underlying factors. One of the primary drivers is culture. In many cases, Madurese parents prepare homes for their married daughters as part of the cultural tradition, which then become the property of the women. This practice serves as a means of securing a home for their daughters after marriage and is often seen as a substitute for the lack of direct inheritance of land and other financial assets. However, this cultural norm also perpetuates the unequal distribution of land rights, as it often results in women being limited to receiving only a house as part of their inheritance. Informant Khozainah said:

In our family, each daughter received a house to live in as well as the right to the land (where the house stands), while even though the sons got no house, they were given land plots to grow crops as a source of income. Here, it is (also) part of our tradition that women return to their parents’ homes to live with them (after marriage).

As one of two daughters, I inherited an equal share of the house fields, and yards alongside my sibling. The division of these assets was made while our mother was still alive, and our father had passed away. Consequently, when our mother passed away, there was no conflict regarding the inheritance, as we simply carried out the verbal instructions she had given us.

The third factor is education. Even if a woman possesses a higher level of education or knowledge, it does not necessarily translate to a change in their position with regard to these rights, regardless of the resources invested in obtaining such education. This point is supported by Jamilia, age 35:

I have two sister. My older sister chose not to pursue higher education at a university, instead opting to assist our parents in managing the crop fields. I continued my education to the master’s level, requiring a significant investment from my parents due to study outside of the city. Upon getting married, I only received a house and did not receive any land in the form of rice fields or yards from my parents.

In restrospect, there are three key factors that contribute to the Madurese cultural norm of women only receiving a house from their parents upon marriage. One is culture, as Madurese society traditionally follows strict gender roles, with men expected to manage the family’s financial affairs and women expected to manage the household. This division of labor often leads to men being the primary inheritors of land and other financial assets. Second is lineage; in Madurese families where there are only daughters, land ownership rights are typically divided among the daughters through the granting of power of attorney to the eldest daughter. The third is education; despite a woman’s level of education or knowledge, it does not necessarily translate to a change in their position with regard to land ownership rights. Together, these three factors highlight how Madurese women are often limited to receiving only a house as part of their inheritance.

4.2.2. Madurese women’s rights pertaining to land ownership

It is common for Madurese women to hold ownership rights over the plot of land on which their house, where they live with their husband and children, is built. There are instances where women may also hold rights to agricultural lands, yards, or business venues. However, if a family includes one or more sons, it is typically the responsibility of the eldest son to divide the assets among the siblings. In families with only daughters, the eldest daughter is typically granted this authority. The following statement is from an interview with Hajjah Soffa, a 55- year-old Madurese woman:

I have one sibling, and we are both women. Our parents provided each of us with a place to live and a place of business, but they did not specify how the remaining assets should be distributed upon their death. As a result, upon the passing of our parents, we frequently disagreed over the division of the inheritance, even though our parents had granted the eldest sibling the authority to divide the assets through power of attorney (as recorded in the village records).

Another informant, Sattar, explained as below:

Our father had seven siblings - six men and one woman. As we prepared to divide the inheritance, we discovered a white certificate issued by the Agrarian Office in 1967 and registered in our father’s name: Sarmo CS. Because the other six siblings were not (legally) identified, we just handled the distribution on behalf of Sarmo’s children or descendants, while the other six siblings did not inherit anything.

4.3. Effects of inequality on Madurese woman

4.3.1. High dependence on men

The lack of land ownership rights for Madurese women often results in their dependence on their husbands or male relatives for livelihood. Rural women in Madura often work in (rice) fields to meet their daily needs, but if they do not have ownership rights to these resources, they may be forced to work for their brothers on a profit-sharing system or as laborers. Informant Saimah, age 50, said:

Our family’s livelihood is dependent on crop plots or rice fields. Since each of the daughters have already given a house, we women did not receive any plot of rice field from our parents. I’ve been working for my older brother on a production sharing system instead.

My husband passed away five years ago when our two children were still little. Before his death, he worked as a gardener at an elementary school and managed the fields handed by his parents. However, after he died, my children and I were left relying on my husband’s pension of only IDR750,000 per month, which isn’t sufficient to support my two children’s education in high school and university, so I asked my brother if I could assist in managing land inherited from our parents, which had previously been solely under my brother’s control.

4.3.2. Less bargaining position

Madurese women are highly protected and respected in their culture. If a woman experiences abuse, her husband or father may take extreme measures, including violence, as a form of revenge known as “carok.” Women are not allowed independence in decision-making, including in the management of agricultural land and yards, which weakens their bargaining position, as demonstrated by a statement by 47-year-old Uswatun Hasanah.

I have always consulted with my brother regarding the cost, type, and number of invitees for celebrations such as my child’s wedding or the birth of their child because I do not have the financial resources to pay for them. The money received from the invitees would ultimately go to my brother. Similarly, when my child was about to give birth, we relied on my brother’s suggestions and decisions on whether to use a midwife or a public health center because he is the one who bears all the costs.

The informant’s statement demonstrates that Madurese women, even those with university- level education, do not have a strong negotiating position in decision-making for themselves and their families. This is exemplified by Kiki Nurhaliza, a 35-year-old Madurese woman, through the following statement:

My parents sent me to complete my bachelor’s degree from IAIN Madura (the State Islamic Institute of Madura). However, upon getting married, they only gave me a house and not a rice field. This is because my brother did not attend college and was therefore given the rice field and crop plot as capital for his family’s income. My parents also cited the high costs of my school fees, engagement, and marriage as a reason (for not providing me with a rice field).

4.3.3. Becoming targets of violence (due to position as objects)

The limited decision-making power of Madurese women, both for themselves and their offspring, can have negative consequences, including violence. Madurese women are often made vulnerable by cultural practices and circumstances, as highlighted by the following statement from Nur Azizah, age 53:

We are economically powerless since we don’t have ownership rights to lands that could be managed and serve as a source of economic stability for our families, making us highly dependent on our husbands and brothers. We often experience harassment and a lack of respect, as we are seen as a burden on the family due to our lack of contribution to the family’s economy. Consequently, we can only accept the decisions made by our husbands or brothers.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This article’s findings indicate that Madurese women face ongoing marginalization in terms of ownership rights, particularly when it comes to land. Strong cultural pressure disadvantages daughters, who are only granted ownership rights to a house and are not given opportunities to own other inherited property, such as agricultural land and yards. Sons are given the primary right to productive land, even if there is an eldest daughter. The patriarchal culture in Madurese society perpetuates the disadvantaged position of daughters and hinders their fair treatment in obtaining land ownership rights within families. This study clearly demonstrates the difficulties that women face in acquiring land in Madurese culture.

The dominance of patriarchal culture supports the unfair treatment of women. This culture only benefits one party and harms other parties even though in principle they have equal rights and access. The position of women and men in the household structure is a structural and non-functional relationship because it is only dominated by inequality and injustice. The practice of subordinating certain parties, in this case, women, occurs not only by the structure of society which consists of social stratification that has been built up firmly. However, this happened because of the strong penetration of culture which tended to be maintained even though it was unfair. The notion that women only have the right to handle household matters continues to be reproduced to prevent them from progressing and being equal to men so their rights remain neglected.

The unequal acquisition of property by women can be understood as a form of structured discrimination that persists to this day. Despite women’s inherent dignity, they continue to face unfair treatment within the family. Daughters, who are traditionally protected, guarded, and supported by men in Madurese families, are increasingly marginalized. Their privileges are not sufficient to empower them with the freedom to act and own property. The strong cultural influence of society can weaken womens’ circumstances, despite their inherent strength. Men often exhibit a disproportionate concern with limiting women’s rights in all areas, including property ownership, which should be their right as well.

As comparison, women in both Madurese society in East Java and Sasak communities in Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, often face injustice when it comes to obtaining land rights. Madurese women may not have the same access to land as men, and Sasak women are generally only able to inherit movable property that is meant to be brought to their husband’s home. Similar to Madurese women, Sasak women are not typically entitled to inherit immovable property, such as land. This means that they may not have the same opportunities to own and control land as men do in their communities. This lack of access to land can have significant negative impacts on the economic and social well-being of women in these communities.

Inequality and unfair treatment of Madurese women can lead to violence against them. To address this issue, it is important to promote the understanding and implementation of religious and agrarian laws, as well as provide education to families in Madurese communities. By increasing awareness of these laws and providing education about gender equality, men and women can work towards achieving equal rights and respect for each other. This can help reduce instances of violence and promote a more just and equitable society for Madurese women.

According to this research, Madurese cultural norms have a significant impact on the rights of women, particularly when it comes to property ownership. This includes land, which is a particularly important resource for economic stability. When women are denied access to property, it can create economic inequality and contribute to violent situations. Additionally, the research points out that patriarchy plays a significant role in Madurese culture, exacerbating the challenges that women face in their roles as primary caregivers for the family. It is hoped that future research will explore cultural construction from other perspectives in other indigenous communities and work towards promoting gender equality in all areas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Umi Supraptiningsih

Umi Supraptiningsih completed her doctoral degree in Law at the University of 17 Agustus 1945, Surabaya, in Indonesia, She currently work as a permanent lecturer. Her research interests are Law Studies, Agrarian Law, Women’s Studies, Gender, and Children.

Hasse Jubba

Hasse Jubba is an Assoc. Prof at Department of Islamic Politics at The University of Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, in Indonesia, He focuses on relationship of religions and countries studies and contemporary Islamic issues.

Erie Hariyanto

Erie Hariyanto Completed his doctoral degree in Law at the University of 17 Agustus 1945, Surabaya, in Indonesia. He currently work as permanent lecturer. His research interests are Law Studies, Islamic Economic Law, Religious Courts in Indonesia, Sharia Mediation, and Arbitration.

Theadora Rahmawati

Theadora Rahmawati completed her master’s degree in Islamic Law with Islamic Family Law as focuses at Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University, Yogyakarta, in Indonesia. She work as a permanent Lecturer. Her research interests are Islamic Family Law Studies, Women and Gender, and Islamic Philanthropy.

References

- Akinola, A. O. (2018). Women, culture and Africa’s land reform agenda. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(2234), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02234

- Alfarisi, S. (2020). Hak Waris Anak dalam Kandungan Menurut Fikih Syafi’i dan Kompilasi Hukum Islam. Juripol (Jurnal Institusi Politeknik Ganesha Medan), 3(1), 134–140. https://doi.org/10.33395/juripol.v3i1.10566

- Arba, M., Suryani, A., Sahnan, S., Wahyuningsih, W., & Andriyani, S. (2020). Kedudukan Hukum Perempuan dalam Perolehan Hak Milik Atas Tanah. Jurnal Kompilasi Hukum, 5(2), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.29303/jkh.v5i2.25

- Atir, S., & Ferguson, M. J. (2018). How gender determines the way we speak about professionals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(28), 7278–7283. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805284115

- Bhalotra, S., Chakravarty, A., Mookherjee, D., & Pino, F. J. (2019). Property rights and gender bias: Evidence from land reform in West Bengal. American Economic Journal Applied Economics, 11(2), 205–237. https://doi.org/10.1257/APP.20160262

- Boe, O. (2015). A Possible Explanation of the Achievement of Gender and Gender Identity. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 190, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.910

- Branisa, B., Klasen, S., & Ziegler, M. (2013). Gender Inequality in Social Institutions and Gendered Development Outcomes. World Development, 45(C), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.12.003

- Daytana, O. H. U. P., & Salmun, J. A. R. (2021). Pengaruh Ketimpangan Gender pada Perempuan terhadap Kondisi Ketersediaan Air Bersih Rumah Tangga di Desa Maradesa Timur Kabupaten Sumba Tengah. Media Kesehatan Masyarakat, 3(3), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.35508/mkm.v3i2.3162

- Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

- Franks, B. (2014). Social construction, evolution and cultural universals. Culture & Psychology, 20(3), 416–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X14542524

- Greenberg, C. C., & Greenberg, J. A. (2020). Gender Bias and Stereotypes in Surgical Training. JAMA Surgery, 155(7), 560–561. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1561

- Hafidh, A., & Krisdyatmiko, K. (2020). Akses Masyarakat Adat terhadap Tanah Ulayat: Studi Kasus pada Masyarakat Adat Minangkabau. Journal of Social Development Studies, 1(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.22146/jsds.210

- Haryono, T. J. S. (2016). Konstruksi Identitas Budaya Bawean. Jurnal BioKultur, 5(2), 166–184. http://journal.unair.ac.id/BK@konstruksi-identitas-budaya-bawean-article-10990-media-133-category-8.html

- Haslanger, S. (2017). The Sex/Gender Distinction and the Social Construction of Reality. The Routledge Companion to Feminist Philosophy, 157–167. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315758152-13

- Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.003

- İncikabı, L., & Ulusoy, F. (2019). Gender bias and stereotypes in Australian, Singaporean and Turkish mathematics textbooks. Turkish Journal of Education, 8(4), 298–317. https://doi.org/10.19128/turje.581802

- Indarti, S. H. (2019). Peran Perempuan dalam Pembangunan Masyarakat. The Indonesian Journal of Public Administration (IJPA), 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.52447/ijpa.v5i1.1650

- Isti’anah, I. (2020). Perempuan dalam Sistem Budaya Sunda (Peran dan Kedudukan Perempuan di Kampung Geger Hanjuang Desa Linggamulya Kecamatan Leuwisari Kabupaten Tasikmalaya). Al-Tsaqafa : Jurnal Ilmiah Peradaban Islam, 17(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.15575/al-tsaqafa.v17i2.9328

- Joshi, S. (2020). Working wives: Gender, labour and land commercialization in Ratanakiri, Cambodia. Globalizations, 17(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2019.1586117

- Karman. (2015). Konstruksi Realitas Sosial Sebagai Gerakan Pemikiran. Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Komunikasi dan Informatika, 5(3), 11–22. https://jurnal.kominfo.go.id/index.php/jppki/article/view/600

- Levien, M. (2017). Gender and land dispossession: A comparative analysis. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(6), 1111–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1367291

- Lindqvist, A., Sendén, M. G., & Renström, E. A. (2021). What is gender, anyway: A review of the options for operationalising gender. Psychology and Sexuality, 12(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1729844

- Mahfiana, L. (2016). Konsepsi Kepemilikan dan Pemanfaatan Hak atas Tanah Harta Bersama antara Suami Istri. Buana Gender: Jurnal Studi Gender Dan Anak, 1(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.22515/bg.v1i1.65

- Marwinda, K., Margono, S., & B, Y. (2020). Dominasi Laki-Laki terhadap Perempuan di Ranah Domestik dalam Novel Safe Haven Karya Nicholas Sparks. Salingka: Majalah Ilmiah Bahasa dan Sastra, 17(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.26499/SALINGKA.V17I2.316

- Mesquita, B., Boiger, M., & De Leersnyder, J. (2016). The cultural construction of emotions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.015

- Muktiyo, W. (2015). Komodifikasi Budaya dalam Konstruksi Realitas Media Massa. MIMBAR, Jurnal Sosial Dan Pembangunan, 31(1), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.29313/mimbar.v31i1.1262

- Muraoka, R., Jin, S., & Jayne, T. S. (2018). Land access, land rental and food security: Evidence from Kenya. Land Use Policy, 70, 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.045

- Ndi, F. A. (2019). Land grabbing, gender and access to land: Implications for local food production and rural livelihoods in Nguti sub-division, South West Cameroon. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 53(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2018.1484296

- Pattiruhu, F. J. (2020). Critical Legal Feminism pada Kedudukan Perempuan dalam Hak Waris pada Sistem Patriarki. Culture & Society: Journal of Anthropological Research, 2(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.24036/csjar.v2i1.57

- Pratiwi, W. A., Yulfana, B. A., & Zamani, M. F. (2020). Konstruksi Budaya pada Tubuh Perempuan Bali dalam Novel Kenanga Karya Oka Rusmini. Jurnal Wanita dan Keluarga, 1(2), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.22146/jwk.1028

- Roof, J. (2015). What gender is, what gender does. E-Proceeding of Managmenet, 8(4), 4106–4117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2017.1338432

- Sakina, A. I., & A, D. H. S. (2017). Menyoroti Budaya Patriarki di Indonesia. Share: Social Work Journal, 7(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.24198/share.v7i1.13820

- Septiadi, M., & Wigna, W. (2015). The Effect of Gender Inequality on Household Survival Strategies of Poor Agricultural Labourer in Cikarawang. Sodality: Jurnal Sosiologi Pedesaan, 01(02), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.22500/sodality.v1i2.9394

- Sitorus, A. V. Y. (2016). The Impact of Gender Inequality on Economic Growth in Indonesia. Sosio Informa, 2(1), 89–101. https://repository.ipb.ac.id/handle/123456789/65721

- Suarmini, N. W., Zahrok, S., & Yoga Agustin, D. S. (2018). Peluang dan Tantangan Peran Perempuan di Era Revolusi Industri 4.0. IPTEK Journal of Proceedings Series, 48–53. https://doi.org/10.12962/j23546026.y2018i5.4420

- Sumaryati, S. (2018). Keadilan Gender dalam Pendidikan Islam di Pondok Pesantren. Tarbawiyah Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan, 2(02), 211. https://doi.org/10.32332/tarbawiyah.v2i02.1315

- Tantoh, H. B., McKay, T. T. J. M., Donkor, F. E., & Simatele, M. D. (2021). Gender Roles, Implications for Water, Land, and Food Security in a Changing Climate: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.707835

- Taqiyuddin, H. (2020). Hukum Waris Islam Sebagai Instrumen Kepemilikan Harta. Asy- Syari’ah, 22(1), 1–158. https://doi.org/10.15575/as.v22i1.7603

- Trubshaw, B. (2011). The Native Mind and the Cultural Construction of Nature. Time and Mind, 4(1), 103–106. https://doi.org/10.2752/175169711x12900033260484

- Tsikata, D. (2016). Gender, Land Tenure and Agrarian Production Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agrarian South, 5(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277976016658738

- Van Der Pas, D. J., & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz046

- Zuhdi, S. (2019). Membincang Peran Ganda Perempuan dalam Masyarakat Industri. Jurnal Hukum Jurisprudence, 8(2), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.23917/jurisprudence.v8i2.7327