Abstract

The healthy living character needs to be intervened and habituated in elementary school students because it positively impacts children’s healthy food intake (fruits and vegetables) and several psychosocial factors (attitudes, knowledge, and self-efficacy). Improving the character of a healthy life needs to be supported by determining an accurate strategy. The study aimed to identify healthy living character-building strategies of elementary school students. This study used systematic review with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Searches for articles related to the topic used Open Knowledge Maps, Google Scholar and Litmaps and found 60 primary articles and supported by secondary sources such as books and proceedings. The review results in the descriptive analysis include geographical distribution and research design. The review results show that current research is still dominated by social cognitive theory and social learning theory, and treatment lengths are categorized into 40 weeks, six months and six years. The findings show that eight dominant strategies are used in shaping healthy living characters through healthy foods for the immune formation of elementary school students. The most effective strategies to facilitate healthy food for primary school students are the strategy of a mix of enhanced curriculum, cross-curriculum and experiential learning and other strategies such as parental involvement. This research provides insight into healthy living character-building strategies in elementary school students and can guide policymakers, principals, and teachers in the development of mixed strategies to improve children’s healthy living character.

1. Introduction

Schools are an important arena for encouraging health promotion practices (Citation2018; World Health Organization WHO, Citation2015). Schools have become a popular place for implementing health promotion and preventive interventions, as schools offer ongoing and intensive contact with children, and lifelong health and well-being begin with promoting healthy behaviours early in life (Lee, Citation2009). School infrastructure, physical environment, policies, curriculum, teaching and learning, and academic staff can positively affect a child’s health. While schools remain a popular infrastructure for health promotion initiatives, teachers will remain the primary agents for promoting health and nutrition in schools (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Citation2013). In this context, schools are recognized as important places for action to change, not least because of their reach and potential to influence how the younger generation engages with food (Hawkes et al., Citation2015). The school provides a physical, social, and educational environment for children and could form physical activity (PA) and eating behaviour (Butland et al., Citation2007).

The formation of children’s eating behaviour involves biological, social, and environmental factors (Ventura & Worobey, Citation2013). Social factors include relationships with others, and in primary school years (ages 5 to 12), parents and teachers are very influential (Pérez-Rodrigo & Aranceta, Citation2001; Shloim et al., Citation2015). The notion that parents and teachers influence children’s eating habits is also consistent with behavioural health theories, such as Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (1979) and Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (1986), which recognizes that significant adults, such as parents and teachers, influence children’s behaviour through role models, normative practices, and social support.

Through the Ministry of Education and Culture (2009), the Indonesian government has formulated a character education policy to integrate it into various subjects and activities in schools. Eighteen types of characters want to be integrated into education in schools. The Directorate of Elementary School Development also involved researchers Directorate General of Primary Education of the Ministry of Education and Culture (2010–2011) to compile Guidelines for Character Education in Elementary Schools. However, that specifically pays attention to the character of healthy living in elementary school students. On the thing, the reality on the ground shows that elementary school learners are invaded by snacks that threaten their health. Meanwhile, their level of assertiveness to invading unhealthy snacks is very low.

Many elementary school students do not have breakfast at home before leaving for school. Some of them replace breakfast with snacks sold outside the school. Jawa Pos Radar Malang (Thursday, 7 March 2013) reported that many of their students consume snacks sold outside the canteen in elementary schools that already have canteens. Snacks consumed by students outside the school cafeteria, based on Investigative Reportage (Trans Television), were found to contain harmful substances such as formalin, borax, textile dyes, preservatives, and aspartame. Schools have often made a series of efforts, but because students do not have a healthy living character, they still risk buying snacks that endanger their health (Mariza & Kusumastuti, Citation2010).

The Food and Beverage Control Agency stated that 40% of snacks were not suitable for eating. “There are many food contents in the form of borax, and formalin still dominates the content of harmful substances in children’s snacks in schools”, said the Director of Food Safety Surveys and Extension, Indonesia (2022). Snacks at school are more varied and attractive than the provisions from home. However, these attractive snacks are poor in nutrition and far from healthy.

Mariza and Kusumastuti (Citation2010), through research in elementary schools in the sub-district of Semarang city, found: 40.62% of the subjects in the case group and 46.87% in the control group found unusual breakfast; 90.65% of the case group and 53.15% of the regular snack control group and there was a relationship between snack habits and obesity. There were 43.76% of subjects who were unusual in breakfast but ordinary snacks, and there were no subjects who were unusual breakfast but unusual snacks. There is a meaningful relationship between breakfast habits and the habit of not snacking. Citation2010) concluded, that the habit of breakfast is related to the habit of not snacking. An unusual breakfast can increase the risk of snacks by 1.5 times. Snack habits are related to poor nutritional status. Regular snacking increases the risk of poor nutritional status more than sevenfold.

Based on that reality, a strategy is needed to strengthen the assertiveness and resilience of students in resisting and resisting the temptation of snacks that invade schools and their environment. Healthy living characters need to be intervened and habituated in elementary school students (Ulfatin et al., Citation2010). Therefore, it is necessary to study strategies for building healthy living character in students, especially those at the elementary school level. The study aims to identify elementary school students’ healthy living character-building strategies. Based on these objectives, our SLRs seek answers to the following research questions: 1) What strategies are used to build a healthy living character? 2) What are the theories used in researching healthy character-building strategies? and 3). How long does treatment take in the application of healthy character-building strategies?

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Previous research

Research related to healthy living, activities and learning outcomes of school students has been carried out independently and in groups. In research evaluating the national examination for Indonesia in the Eastern region, Wiyono and Imron (Citation2010) found that the school, in collaboration with parents, must carry out student management focusing on the right services. The research, sponsored by the Directorate of Primary School Development of the Ministry of National Education, found that the provision of milk by parents in the appeal of schools when children prepare for national exams and during the implementation of national exams further strengthens children’s learning activities. Comparative analysis of the results of the previous year’s exam (when parents did not provide milk) and the test results when the evaluation was carried out (parents provided milk) showed an increase in national test scores in eastern Indonesia.

Research conducted by Ulfatin et al. (Citation2010) also found that in primary school children in rural areas, most (more than 70%) of the population surveyed never had breakfast, drank milk, and were nutritionally deficient. In the rural and mountainous geographical environment with a long distance, children come to school in a “lacklustre” state, sleepy and unable to concentrate on studying. Interestingly, these children always carry pocket money to buy food, which is detrimental to health from health analysis.

In previous research, Citation1996) found a significant association between the level of parental involvement in educating children and their motivation and learning achievement. Research that outlines the level of involvement in educating children based on De Roche’s theory (1985) includes his attention to their learning, the facilitation provided, and the provision of nutritionally adequate foods. The study recommends that parents and schools consider aspects of the child’s diet, nutrition and nutrition and pay attention to maintaining the child’s health.

Imron (Citation2001) examined rural local elites in Sukolilo village, Jabung District, Malang Regency, also found that the involvement of rural local elites such as village heads (formal elites), kyai (grassroots organization elites), village entrepreneurs (market sector elites), greatly determines the success of compulsory education in rural areas. The involvement of the local rural elite, even touching the socioeconomic aspects of the citizens, leads to the problem of direct and indirect learning costs and concerns the nutritional factors that children should consume. The diet of learners in the family environment, and when they are about to leave for school is recommended to be taken seriously.

In national strategic research, Imron et al. (Citation2009) found that there are (1) profiles of adolescent mental resilience levels in the face of negative influences in their environment, (2) strategic local wisdom values to improve adolescent mental resilience, and (3) soft skills aspects that are prioritized to improve adolescent mental resilience. The values of local wisdom and soft skills are recommended to be integrated into learning, because it is proven to increase the mental endurance of adolescents facing current shocks from their environment. The influence of healthy snacks from peer groups makes students tempted when their activity level is relatively low, and the character of healthy living is still not owned.

The results of research in elementary schools found that the contribution of snacks to students’ daily consumption ranged from 10–20% (Ulya, Citation2003). Energy from snack foods contributed by 17.36%, protein by 12.4%, carbohydrates by 15.1%, and fat by 21.1% to daily consumption [9]. Meanwhile, Syafitri et al. (Citation2009), while conducting a case study at the Lawanggintung 01 public elementary school in Bogor City, found that more than half of the students allocated their pocket money for snack food (68%). As many as 50.0% of students buy 2–3 types of main meals/week. 46.0% of students buy snacks of 6–7 types/week, and 46.0% buy drinks of 4–5 types/week. The frequency of students’ main food snacks (3–5 times/week) was (44.0%). 66.0% of students have a snack frequency>11 times/week, and 30.0% have a frequency of snacking drinks 6–8 times/week. 34.0% of students have energy adequacy in the weight category and normal-level deficits. The level of adequacy of proteins and fats is in an excess category by (46.0%) and (56.0%), respectively.

Other research results pointed out that school food programs have been identified as promising strategies to encourage the healthy development of children (Ortega et al., Citation2008). In Canada (García-Hermoso et al., Citation2019) and internationally (Tanaka et al., Citation2020), school food programs have shown a positive impact on children’s healthy food intake (fruits and vegetables) and several psychosocial factors (attitudes, knowledge, and self-efficacy) known to mediate healthy eating behaviours (Chen et al., Citation2018). School food programs also have the potential to improve the quality of children’s food literacy (Sandercock et al., Citation2010), reduce social disparities in fruit and vegetable consumption (Zaqout et al., Citation2016), strengthen local food systems and can provide an effective response to food insecurity (Emmett & Jones, Citation2015; Ismail et al., Citation2022). Research in Argentina showed that common cafeterias play a key role in incorporating unusual foods such as certain vegetables. Public school cafeterias have a higher potential to promote healthy food choices than private school cafeterias (Molina-Bonetto, Citation2022).

Based on the research results, the rush of unhealthy snacks has surrounded students from all situations. Their resilience in the face of the invasion of unhealthy foods and unhealthy living habits of the environment and its peer groups must be improved. Internal reinforcement of students to have a healthy living character should be intervened and eliminated. Kusmintardjo (Citation2007) pointed out that schools were established to provide learning experiences that can develop students’ knowledge, skills, habits, attitudes, personalities and characters as expected of good citizens. Therefore, the child’s personal development in the broadest sense requires well-maintained health.

2.2. Healthcare

Health services are a special type of service provided by schools to learners. As one of the institutions responsible for educating students in schools, schools must be responsible for the advancement of the health of their students. It depends on the principal and teachers’ knowledge of health and school health programs, appreciation of health values, the ability to work closely with other members of the health team, and especially on the attention to the child as well as skills in helping to develop knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors about health.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as follows: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. In some developed countries, such as the United States, as mentioned by the American Council of Education (2005), health-related education aims to improve and maintain one’s health and take responsibility for maintaining the health of others. In detail, the objectives of school health services, as identified by Kusmintardjo (Citation2007), are so that students have knowledge and understanding of (1) normal bodily functioning concerning good health practices,(2) the dangers of important diseases, their prevention and control; (3) the relationship between mental and physical processes in health; (4) reliable sources of health information; (5) scientific methods of evaluating health concepts; (6) the influence of socioeconomic circumstances on health; (7) public health issues, such as issues related to sanitation and industrial health.

According to Kusmintardjo (Citation2007), in terms of skills and abilities, health services in schools are expected to make students have: (1) the ability to manage time, including planning food, work, recreation, rest and holidays; (2) the ability to repair and maintain nutritious food; (3) the ability to achieve and maintain good emotional adjustment;(4) the ability to select and participate in recreational activities, and health exercises appropriate to individual needs; (5) the ability to avoid unnecessary diseases and infections; (6) the ability to use medical and dental services in an intelligent manner; and (7) the ability to participate in health prevention and improvement efforts.

2.3. Healthy living character

The term “character” comes from the Greek word “charassein”, which means to engrave or carve on a gemstone or hard iron surface. Character means the traits-psyche, morals/ethics that distinguish a person from others (Kamus Bahasa Indonesia, 2008). The character also means “Distinctive trait, distinctive quality, moral strength, the pattern of behaviour found in an individual or group” (Webster’s New World Dictionary). The character also means“… an individual’s pattern of behavior… his moral constitution …”(Bohlin et al., Citation2001). According to Alport, “character is personality evaluated”. Meanwhile, according to Freud, “character is a striving system which underly behavior”. Ghozali (Citation1995) considers character closer to akhlaq, that is, human spontaneity in attitude or deeds that have converged in man so that when they appear, there is no need to think about it again.

Terminologically, the character is typical-good values (knowing the value of kindness, wanting to do good, real living well, and having a good impact on the environment) that are embedded in oneself and manifested in behavior. Character coherently emanates from the results of thought sports, heart sports, sports, and the sports of taste and feeling of a person or group of people. Character is a person or group characteristic of values, abilities, moral capacities, and obstinacy in facing difficulties and challenges (Imron, Citation2011).

The character has to do with moral force, connoting “positive”, not neutral (Akbar, Citation2012). A person of character is a person who has positive moral qualities. Thus, character-building education implicitly implies establishing traits or patterns of behaviour based on or related to a positive or good moral dimension, not a negative or bad one (Carter, Citation1981). Pay attention to various definitions (etymology and terminology) (Purwadarminta, Citation2008). The Ministry of National Education defines character as distinctively good values (knowing the value of good, wanting to do good, having a good life and a good impact on the environment) that are imprinted in themselves and implicated in behaviour (Kemendiknas, Citation2010). The Ministry of National Education identified 18 values in National Cultural and Character Education derived from religion, Pancasila, culture, and national education goals. The eighteen values are religious, honest, tolerant, disciplined, hard work, creative, independent, democratic, curiosity, national spirit, love of homeland, respect for achievements, friendly or communicative, peace-loving, fond of reading, environmental care, social care, and responsibility (Puskur, Citation2009).

There are several general strategies for building the healthy living character of students through student management, both top-down and bottom-up and horizontal strategies. Top-down strategies are offered by the perspective of behavioristic psychology, while the perspective of humanistic psychology offers strategies of a bottom-up nature. This strategy provides a great opportunity for students to learn a lot independently and gives them the confidence to develop a variety of activities that lead to the formation of positive character. What is emphasized in this bottom-up strategy is that the mentor is more aware of the urgency of the behavior that leads to good character. The consciousness built here includes intellectual-rational, emotional-heart and spiritual awareness. Theoretically, character education involves not only the aspects of “knowing the good” (moral knowing) but also “desiring the good” or “loving the good” (moral feeling) and “acting the good” (moral action) (Imron, Citation2011).

3. Method

3.1. Design

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify relevant previous research for inclusion in this study review (Siangchokyoo et al., Citation2020). The author uses the systematic review method to answer research questions and achieve predetermined goals. The systematic review has high academic value because it collaborates with experts who synthesize strong evidence by reviewing and summarizing secondary data relevant to the question under review (Amiri et al., Citation2020). The systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009).

3.2. Search strategy and sample

A search of the review literature includes three electronic databases: openknowledgemaps (BASE: all disciplines), Google scholar and litmaps. Search strings are used to search for things like “Healthy living character” AND “elementary school” OR “Primary school”, “healthy food” AND “strategy”, “nutrition education” AND”strategy” AND elementary school OR “Primary school”,”healthy eating” AND”strategy” AND “elementary school”, and “food OR ‘nutrition’ AND”strategy”. A literature search was conducted between 1973 and 2022 regarding healthy living character-building strategies in elementary schools.

Based on the PRISMA guidelines, 486 papers were found taken in a literature search; after duplicates and non-journals were deleted, there were still 240 articles that met the criteria. After the screening process was carried out by removing no strategy and treatment and not primary school level, 60 articles were found that met the inclusion criteria (Figure ). Table illustrates the list of articles included in the study.

Table 1. Healthy living character-building strategies through healthy food for elementary school students

3.3. Data analysis

In this study, the authors used content analysis—a research technique used to systematically explain and analyze the content of writings such as books, newspapers, and journal articles to make valid conclusions from the text to the context applied (Krippendorff, Citation2004; Vogt, Citation2005; Dami, Citation2021). Content analysis is related to critical and reflective studies on student management, especially strategies for building healthy living character through healthy food to strengthen students’ immunity. This study also seeks a deeper understanding of related research (Esen et al., Citation2018) based on a healthy living character to strengthen students’ immunity. The main purpose of content analysis is to find answers to questions such as: What is the right strategy in shaping the character of healthy living to promote healthy food to strengthen the immunity of elementary school students?

The content analysis method used in this study involves two steps. First, the authors selected texts relevant to the objectives of the study, based on a literature review that sought to obtain representative texts related to the prescriptive part (“what should be”)—the application of appropriate strategies in shaping the character of healthy living through promoting healthy foods (“what exists”)—in this case, strengthening the immunity of elementary school students through healthy food. At this stage, the author uses open Knowledge maps, Google scholar and Litmaps to conduct a literature review to obtain representative texts on strategies to form healthy living characters and healthy food for elementary school students. To determine the publications related to the topic of this study, then a combination of keywords and phrases is investigated. By searching with the keywords ‘healthy eatingʹ, ‘elementary school studentʹ, ‘strategies to promote healthy eatingʹ, nutrition education, and ‘food and nutrition. The search results found 60 primary articles related to the study topic, supported by articles, books, and proceedings.

The second step involves coding messages embedded in the text according to the concept of the student’s healthy living character. At this stage, the authors first unite or identify the right units of a message to code, using the technique suggested by Krippendorff (Citation2004), which identifies the number of main books and articles that discuss healthy living character-building strategies through healthy food to strengthen the immunity of elementary school students. These other sources come from other references used to support primary data and identify words, sentences, statements, and arguments related to this topic of study, thus finding the dominant strategy used to shape the character of healthy living of students through healthy food to strengthen students’ immunity.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive analysis

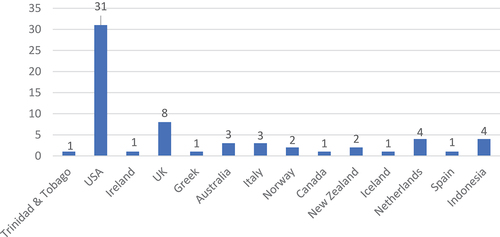

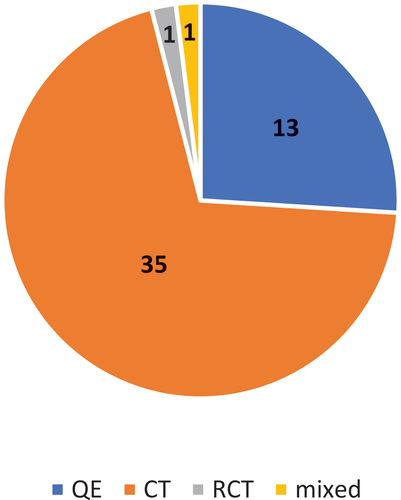

This review provides a descriptive analysis of the study. This includes geographical distribution, and research design (Figure ).

Most research on healthy living character-building strategies through healthy food for elementary school students was found in the United States of America, with 31 articles (Figure ). The second largest research concentration was found in the United Kingdom, with eight articles. These findings indicate that the topic of this study is mostly limited to countries other than the United States of America and the United Kingdom, including Indonesia, which is only four articles. This suggests that this topic still needs to be developed in research.

Most of the research conducted in the literature is quantitative with a cluster-controlled trial research design, contributing about 35 articles (Figure ). A total of 13 articles from the research design were quasi-experimental, and one article each used a randomised controlled trial and mixed. This indicates the need for further qualitative studies to be carried out.

4.2. Healthy living character building strategies

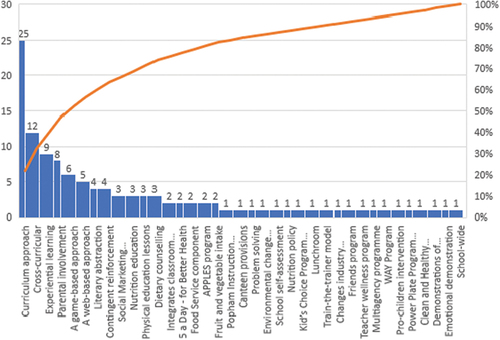

Eight dominant strategies for character-shaping healthy living address the predetermined areas of healthy food for primary school students (food consumption/energy intake, consumption or preference of fruits and vegetables, consumption or preference of sugar, and nutritional knowledge). Some studies include more than one of these teaching strategies in their intervention groups (Figure ).

Strategies for shaping the healthy living character of primary school students that are dominant are: 1) An enhanced curriculum approach (i.e. a special nutrition education program outside the existing health curriculum delivered by teachers or specialists); 2) a cross-curricular approach (i.e. a nutrition education program delivered in two or more traditional primary school subjects); 3) parental involvement (i.e. programs that require active participation or assistance from parents inside or outside the school environment); 4) experiential learning approaches (i.e. school or community garden activities, cooking and preparing meals); 5) a contingent reinforcement approach (an award or incentive given to a student in response to a desired behavior); 6) an approach to literary abstraction (i.e. literature read by/for children in which the character promotes or exemplifies positive behavior); 7) a game-based approach (a board or card game played by students at school designed to promote positive behavior and the learning of new knowledge); and 8) a web-based approach (i.e. an internet-based resource or feedback mechanism accessible to students at home or school).

4.3. Theory used in research on healthy character-building strategies

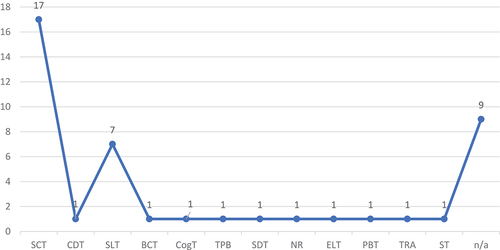

Figure provides an overview of the theoretical perspective on healthy character-building strategies through healthy living for healthy food for elementary school students.

Figure 5. Theory.

In all, 16 theories were identified. The two theories commonly used in the literature include social cognitive theory and social learning theory, while the ten theories are still little used in the literature, including the theory of planned behaviour; cognitive development theory; behavioural choice theory; cognitive theory; self-determination theory; group socialization theory; experiential learning theory; problem behaviour theory; theory of reasoned action and stakeholder theory, and nine studies do not use the theory dominated by Indonesia. The results of this review indicate that many theories still need to be used for future research. The findings of this review also prove that one of the dominant strategies used is experiential learning, but it is not supported by experiential learning theory.

4.4. Duration of treatment in the implementation of a healthy character-building strategy

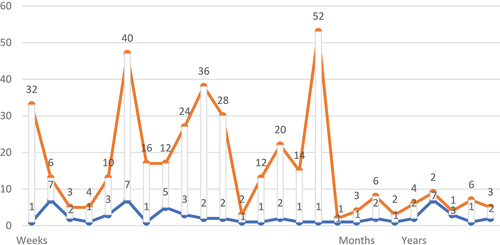

Based on Figure , it was found that the length of treatment was 40 weeks (curriculum approach, cross-curricular, parental involvement, and experiential learning), six months (Power Plate Program and fruit and vegetable provision), and six years (curriculum approach & literary abstraction).

5. Discussion

This study aims to identify and describe various intervention strategies for the healthy living character of learners in promoting healthy food to strengthen students’ immunity. Based on the content analysis approach, it was found that the application of the strategy cannot be done in a single piece but must be mixed because it supports and complements each other. First, curriculum-based strategies are the most popular or better that can reduce food consumption or energy intake results. In addition, other studies using experiential learning approaches (school/community gardens, cooking lessons, and food preparation) reported results related to reducing food consumption and energy intake. The study of first-graders aged 6–7 at three public elementary schools in Tokyo found that energy from healthy eating correlated with motor fitness in children and their physical activity. These findings suggest that consuming a healthy diet that includes whole grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy, fish and meat, and exercise habits is essential for childhood motor fitness (Hatta et al., Citation2022).

Second, curriculum-based strategies are once again the most popular regarding fruit and vegetable consumption or preference. The curriculum-based approach was statistically significant in increasing fruit and vegetable consumption or preferences among children of primary school age (Dudley et al., Citation2015). However, it is important to note that many studies that use a curriculum-based approach also combine their interventions with secondary approaches (experience-learning and parental involvement). The involvement of the person referred to in this study is communication between parents and teachers about lunch boxes, communication barriers and ways of improving the communication of parent and teacher engagement, and parents’ expectations of teachers, and especially schools need to prepare time allocations for children to have lunch (Aydin et al., Citation2022). The results of previous studies showed that parents should supervise and teach children about the dangers of consuming food carelessly so that children can distinguish foods that are good for consumption at school (Nasution et al., Citation2021). Thus, at this stage, it is difficult to determine the extent to which one’s curriculum-based approach contributes to forming a healthy living character to strengthen the immunity of elementary school students.

Third, in primary school, enhanced curriculum strategies (based mainly on behavioral or social cognitive theories) are required by students to reduce sugar consumption or sugar-laden drinks, fruit juices or carbohydrate consumption. Furthermore, Taylor et al. (Citation2007) found that cross-curricular strategies by reducing the consumption of sugar or fruit juices can improve the healthy living behaviors of elementary school students. Fourth, previous research also adopted a curriculum approach that needs improvement to develop primary school children’s nutritional knowledge. This suggests that quality curriculum interventions (largely based on behavioral or social cognitive learning theory) can improve primary school students’ nutritional knowledge with desired zones of effect (Hattie, Citation2009). In line with other studies (Reynolds et al., Citation2000; De Villiers et al., Citation2016), another study showed that receiving an education led to a significant increase in nutritional knowledge in primary school children. This increase in knowledge in children remains significant over the long term and is in line with previous studies, which identified a significant increase in the nutritional knowledge of primary school children after education. Increasing knowledge can be done through fruit and vegetable advertisements—which effectively increase fruit and vegetable consumption among children (Oke & Tan, Citation2022). The results of previous studies showed that whether school food policy is implemented or not can affect the potential of fruit and vegetable provision programs to affect the fruit and vegetable intake of primary school children. The effectiveness of healthy living character programs through healthy food will increase if school food policies are implemented (Verdonschot et al., Citation2020).

6. Conclusion

The results of this study show that many strategies can be used to shape the healthy living character of primary school children that lead to positive changes in the nutritional knowledge and behaviour of primary school children, especially healthy foods, to strengthen the immunity of elementary school students. The most effective strategies to facilitate healthy eating in children’s primary schools are improved curricula, cross-curricula, and experiential learning approaches. These strategies must be mixed with other strategies, such as parental involvement.

The dominant theories used include social cognitive theory and social learning theory, while still little used in the literature, namely the theory of planned behaviour; cognitive development theory; behavioural choice theory; cognitive theory; self-determination theory; group socialization theory; experiential learning theory; problem behaviour theory; theory of reasoned action and stakeholder theory. Finally, treatment lengths are categorized into 40 weeks, six months and six years.

The study’s results significantly contribute to policymakers, principals and teachers developing a curriculum and integrating appropriate mixed strategies in improving students’ healthy life character behaviour because it can strive for the quality of education and student outcomes. This mixed strategy is made into a national program, created guidelines, disseminated, implemented, and evaluated gradually.

7. Agenda for future research

In a systematic review on healthy living character-building strategies of elementary school students, we found that implementing strategies to improve the healthy living character of elementary school students cannot only use one strategy but must be a mix of strategies. The curriculum-based approach is integrated with cross-curricular, experience-learning, and parental involvement. Building a healthy living character in elementary schools needs to be supported by a mixed strategy because each strategy complements the other. Future research needs to consider mixed strategies so that there is a significant increase in healthy living character. Current research is still dominated by social cognitive theory and social learning theory.

In contrast to that, other studies do not use theory. Future research needs to adopt theories that are still rarely used, including behavioural choice theory, cognitive theory, theory of planned behaviour, self-determination theory, problem behaviour theory, theory of reasoned action, and stakeholder theory. Regarding the length of treatment, each strategy has its time duration. The literature review found that the most widely used strategy, the curriculum approach, had two different durations of time, 40 weeks, and six years. Thus, future research must use cultural variables to measure timing based on context. Based on this, the research methods that can be used are qualitative with case study approaches, phenomenology, site studies and ethnography. This qualitative research method is still scarce in this research topic. Future research will be interesting if studies examine comparisons between public and private schools to identify strategy implementation effectiveness. Finally, geographical research in Indonesia related to this topic needs to be followed up because it still needs to be improved.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ali Imron

Ali Imron is a Professor at the Department of Educational Management, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. His research interests are Educational Management, Character Building, Educational Administration and Educational Supervision in Primary Education.

Mustiningsih Mustiningsih

Mustiningsih is an Associate Professor at the Department of Educational Management, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Her research interests are Educational Management, Educational Leadership, and Educational Supervision.

Rochmawati Rochmawati

Rochmawati is a Lecturer at the Department of Educational Administration, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Her research interests are Quality Management Systems, Educational Management, Character Building, Quality Culture, Quality Assurance, Educational Administration and Supervision.

Rachma Putri Kasimbara

Rahma Putri Kasimbara is a lecturer at the Institute of Science Technology and Health, Dr. Soepraoen Kesdam V/Brawijaya Hospital Malang. Her research interests are Student Health Education and Student Health Services.

Zummy Anselmus Dami

Zummy Anselmus Dami is a Doctoral candidate in Educational Management at Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. He is a lecturer at the Faculty of Education, Universitas Persatuan Guru 1945 NTT. His research interests are Educational Leadership, Pedagogy and Christian Education.

Kamilatun Nisa

Kamilatun Nisa is a master's student at the Department of Educational Management, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Her research interests are a teacher's pedagogical abilities, professionalism, and academic supervision.

References

- Agozzino, E., Esposito, D., Genovese, S., Manzi, E., & Russo, K. P. (2007). Evaluation of the effectiveness of a nutrition education intervention performed by primary school teachers. Italian Journal of Public Health, 4(4), 131–20.

- Akbar, S. (2012). Pendidikan Karakter Melalui Pendekatan Menyeluruh. Kemendikbud.

- Amaro, S., Baccari, A., DiCostanzo, A., Madeo, I., Viggiano, M. E., Kaledo, E., Marchitelli, Marchitelli, E., Raia, M., Viggiano, E., Deepak, S., Monda, M., & De Luca, B. (2006). Kalèdo, a new educational board-game, gives nutritional rudiments and encourages healthy eating in children: A pilot cluster randomized trial. European Journal of Pediatrics, 165(9), 630–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0153-9

- Amiri, N. A., Rahima, R. E. A., & Ahmed, G. (2020). Leadership styles and organizational knowledge management activities: A systematic review. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 22(3), 250–275. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.49903

- Anderson, A. S., Porteous, L. E., Foster, E., Higgins, C., Stead, M., Hetherington, M., Ha, M. -A., & Adamson, A. J. (2005). The impact of a school-based nutrition education intervention on dietary intake and cognitive and attitudinal variables relating to fruits and vegetables. Public Health, 8(6), 650–656. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004721

- Auld, G. W., Romaniello, C., Heimendinger, J., Hambidge, C., & Hambidge, M. (1998). Outcomes from a school-based nutrition education program using resource teachers and cross-disciplinary models. Journal of Nutrition Education, 30(5), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(98)70336-X

- Aydin, G., Margerison, C., Worsley, A., & Booth, A. (2022). Parents’ communication with teachers about food and nutrition issues of primary school students. Children, 9(4), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9040510

- Baranowski, T., Davis, M., Resnicow, K., Baranowski, J., Doyle, C., Lin, L. S., Smith, M., & Wang, D. T. (2000). Gimme 5 fruit, juice, and vegetables for fun and health: Outcome evaluation. Health Education & Behavior, 27(1), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700109

- Bell, C. G., & Lamb, M. W. (1973). Nutrition education and dietary behavior of fifth graders. Journal of Nutrition Education, 5(3), 196–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(73)80086-X

- Bere, E., Veierod, M. B., Bjelland, M., & Klepp, K. I. (2006). Outcome and process evaluation of a Norwegian school-randomized fruit and vegetable intervention: Fruits and vegetables make the marks (FVMM). Health Education Research, 21(2), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyh062

- Bohlin, K., Farmer, D., & Ryan, K. (2001). Building character in schools resource guide. Jossey-Bass.

- Butland, B., Jebb, S., & Kopelman, P. (2007). Tackling obesities: Future choices-project report. 2nd edn. Government Office for Science. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287937/07-1184x-tacklingobesities-future-choices-report.Pdf

- Carter, V. G. (1981). Dictionary of education. McGraw Hill Book Company.

- Chen, W., Hammond Bennett, A., Hypnar, A., & Mason, S. (2018). Health-related physical fitness and physical activity in elementary school students. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5107-4

- Cohen, J. F. W., Eric, B. R. S., Austin, B., Hyatt, R. R., Kraak, V. I., & Economos, C. D. (2014). A food service intervention improves whole grain access at lunch in rural elementary schools. The Journal of School Health, 84(3), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12133

- Cooke, L. J., Chambers, L. C., Anez, E. V., Croker, H. A., Boniface, D., Yeomans, M. R., & Wardle, J. (2011). Eating for pleasure or profit: The effect of incentives on children’s enjoyment of vegetables. Psychological Science, 22(2), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610394662

- Dami, Z. A. (2021). Informal teacher leadership: Lessons from shepherd leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.1884749

- Day, M. E., Strange, K. S., McKay, H. A., & Naylor, P. (2008). Action schools! BC — healthy eating. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 99(4), 328–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403766

- de Villiers, A., Steyn, N. P., Draper, C. E., Hill, J., Gwebushe, N., Lambert, E. V., & Lombard, C. (2016). Primary School Children's Nutrition Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, and Behavior, after a Three-Year Healthy Lifestyle Intervention (HealthKick). Ethnicity & Disease, 26(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.26.2.171

- Domel, S. B., Baranowski, T., Davis, H., Thompson, W. O., Leonard, S. B., Riley, P., Baranowski, J., Dudovitz, B., & Smyth, M. (1993). Development and evaluation of a school intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among 4th and 5th grade students. Journal of Nutrition Education, 25(6), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(12)80224-X

- Dudley, D. A., Cotton, W. G., & Peralta, L. R. (2015). Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), 2–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0182-8

- Duncan, S., McPhee, J. C., Schluter, P. J., Zinn, C., Smith, R., & Schofield, G. (2011). Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: The healthy homework pilot study. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-127

- Edwards, C. S., & Hermann, J. R. (2011). Piloting a cooperative extension service nutrition education program on first-grade children’s willingness to try foods containing legumes. Journal of Extension, 49(1), 1–4.

- Emerson, M., Hudgens, M., Barnes, A., Hiller, E., Robison, D., Kipp, R., Bradshaw, U., & Siegel, R. (2017). Small prizes increased plain milk and vegetable selection by elementary school children without adversely affecting total milk purchase. Beverages, 3(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages3010014

- Emmett, P. M., & Jones, L. R. (2015). Diet, growth, and obesity development throughout childhood in the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Nutrition Reviews, 73(suppl 3), 175–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv054

- Esen, M., Bellibas, M. S., & Gumus, S. (2018). The evolution of leadership research in higher education for two decades (1995–2014): A bibliometric and content analysis. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(3), 2590273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1508753

- Fahlman, M. M., Dake, J. A., McCaughtry, N., & Martin, J. (2008). A pilot study to examine the effects of a nutrition intervention on nutrition knowledge, behaviors, and efficacy expectations in middle school children. The Journal of School Health, 78(4), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00289.x

- Foster, G. D., Sherman, S., Borradaile, K. E., Grundy, K. M., Vander Veur, S. S., & Nachmani, J. (2008). A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics, 121(4), e794–802. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1365

- Francis, M., Nichols, S. S. D., & Dalrymple, N. (2010). The effects of a school-based intervention programme on dietary intakes and physical activity among primary-school children in Trinidad and Tobago. Public Health Nutrition, 13(5), 738–747. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980010000182

- Friel, S., Kelleher, C., Campbell, P., & Nolan, G. (1999). Evaluation of the Nutrition Education at Primary School (NEAPS) programme. Public Health Nutrition, 2(4), 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980099000737

- García-Hermoso, A., Ramírez-Campillo, R., & Izquierdo, M. (2019). Is muscular fitness associated with future health benefits in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sports Medicine, 49(7), 1079–1094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01098-6

- Garden, E. M., Pallan, M., Clarke, J., Griffin, T., Hurley, K., Lancashire, E., Sitch, A. J., Passmore, S., & Adab, P. (2020). Relationship between primary school healthy eating and physical activity promoting environments and children’s dietary intake, physical activity and weight status: A longitudinal study in the West Midlands, UK. BMJ Open, 10(12), e040833. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040833

- Ghozali, A. (1995). Ihya Ulumuddin. Al Maarif.

- Gorely, T., Nevill, M. E., Morris, J. G., Stensel, D. J., & Nevill, A. (2009). Effect of a school-based intervention to promote healthy lifestyles in 7–11 year old children. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-5

- Gortmaker, S. L., Cheung, L. W. Y., Peterson, K. E., Chomitz, G., Cradle, J. H., Dart, H., Fox, M. K., Bullock, R. B., Sobol, A. M., Colditz, G., Field, A. E., & Laird, N. (1999). Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: Eat well and keep moving. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153(9), 975–983. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975

- Govula, C., Kattelman, K., & Ren, C. (2007). Culturally appropriate nutrition lessons increased fruit and vegetable consumption in American Indian children. Topics in Clinical Nutrition, 22(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.TIN.0000285378.01218.67

- Hatta, N., Tada, Y., Ishikawa-Takata, K., Furusho, T., Kanehara, R., Hata, T., Hida, A., & Kawano, Y. (2022). Energy intake from healthy foods is associated with motor fitness in addition to physical activity: A cross-sectional study of first-grade schoolchildren in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1819–1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031819

- Hattie, J. A. (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

- Hawkes, C., Smith, T. G., Jewell, J., Wardle, J., Hammond, R. A., Friel, S., Thow, A. M., & Kain, J. (2015). Smart food policies for obesity prevention. The Lancet, 385(9985), 2410–2421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61745-1

- Head, M. K. (1974). A nutrition education program at three grade levels. Journal of Nutrition Education, 6(2), 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(74)80059-2

- Hendy, H. M., Williams, K. E., & Camise, T. S. (2011). Kid’s Choice Program improves weight management behaviors and weight status in school children. Appetite, 56(2), 484–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.024

- Hoffman, J. A., Franko, D. L., Thompson, D. R., Power, T. J., & Stallings, V. A. (2010). Longitudinal behavioral effects of a school-based fruit and vegetable promotion program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp041

- Horne, P. J., Tapper, K., Lowe, C. F., Hardman, C. A., Jackson, M. C., & Woolner, J. (2004). Increasing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption: A peer-modelling and rewards-based intervention. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 58(12), 1649–1660. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602024

- Ibnu, I. F., Syafar, M., Awaluddin, & Awaluddin, A. (2021). Education of healthy hoods with emotional demonstration methods in primary schools. Jurnal Sinergitas PKM & CSR, 5(3), 515–524. https://doi.org/10.19166/jspc.v5i1.3437

- Imron, A. (2001). Sinergi antar Elit Lokal Pedesaan Dalam Layanan Wajib Belajar di Desa Sukolilo Kecamatan Jabung Kabupaten Malang. PPS Universitas Brawijaya.

- Imron, A. (2011). Panduan Pendidikan Karakter Melalui Kegiatan Ekstra Kurikuler. Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Dasar, Kemendikbud.

- Imron, A., Iriaji I., & Dayati, U. (2009). Peningkatan Ketahanan Mental Remaja Melalui Integrasi Soft Skill dan Nilai Kearifan Lokal dan Soft Skill dalam Pembelajaran di Sekolah Menengah. DP2M, Ditjen Dikti.

- Ismail, M. R., Gilliland, J. A., Matthews, J. I., & Battram, D. S. (2022). School-level perspectives of the Ontario student nutrition program. Children, 9(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020177

- James, J., Thomas, P., Cavan, D., & Kerr, D. (2005). Preventing childhood obesity by reducing consumption of carbonated drinks: Cluster randomised controlled trial. The BMJ, 328(1), 1237–1239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38077.458438.EE

- Kemendiknas, R. I. (2010). Kebijakan Nasional Pembangunan Karakter Bangsa. Kemendiknas.

- Kipping, R. R., Jago, R., & Lawlor, D. A. (2010). Diet outcomes of a pilot school-based randomised controlled obesity prevention study with 9–10 year olds in England. Preventive Medicine, 51(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.011

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x

- Kristjansdottir, A. G., Johannsson, E., & Thorsdottir, I. (2010). Effects of a school-based intervention on adherence of 7–9-year-olds to food-based dietary guidelines and intake of nutrients. Public Health Nutrition, 13(8), 1151–1161. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980010000716

- Kusmintardjo, K. (2007). Paket Diklat Manajemen Layanan Khusus di Sekolah. Dittendik Kemendiknas.

- Lee, A. (2009). Health-promoting schools: Evidence for a holistic approach to promoting health and improving health literacy. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 7(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256138

- Liquori, T., Koch, P. D., Contento, I. R., & Castle, J. (1998). The cookshop program: Outcome evaluation of a nutrition education program linking lunchroom food experiences with classroom cooking experiences. Journal of Nutrition Education, 30(5), 302–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(98)70339-5

- Luepker, R. V., Perry, C. L., McKinlay, S. M., Nader, P. R., Parcel, G. S., & Stone, E. J. (1996). Outcomes of a field trial to improve children’s dietary patterns and physical activity: The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health CATCH collaborative group. JAMA, 275(10), 768–776. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026

- Magurno, J. M., & Fenton, M. E. (2022). Nutrition education intervention increases dietary knowledge and fruit/vegetable consumption among 2nd grade students. In CHIP Project for Masters in Nutrition and Dietetics. SUNY Oneonta. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/7198

- Mangunkusumo, R. T., Brug, J., De Koning, H. J., Van Der Lei, J., & Raat, H. (2007). School based internet-tailored fruit and vegetable education combined with brief counselling increases children’s awareness of intake levels. Public Health Nutrition, 10(3), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007246671

- Manios, Y., Moschandreas, J., Hatzis, C., & Kafatos, A. (2002). Health and nutrition education in primary schools of Crete: Changes in chronic disease risk factors following a 6-year intervention programme. The British Journal of Nutrition, 88(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN2002672

- Mariza, Y. Y., & Kusumastuti, A. C. (2010). Kebiasan Sarapan dan Jajan Siswa SD Kecamatan Pedurungan Kota Semarang. Fakultas Kesehatan Masyarakat.

- McAleese, J., & Rankin, L. (2007). Garden-based nutrition education affects fruit and vegetable consumption in sixth-grade adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(4), 662–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.015

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Grp, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (reprinted from annals of internal medicine). Physical Therapy, 89(9), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/89.9.873

- Molina-Bonetto, C., de Rosas-Reta, M. L., Carril, R.M.B.D., & Weisstaub-Nuta, S. G. (2022). ¿Estudiantes o consumidores? Prácticas de comensalidad en escuelas primarias de Mendoza, Argentina. Hacia la Promoción de la Salud, 27(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.17151/hpsal.2022.27.1.7

- Morgan, P. J., Warren, J. M., Lubans, D. R., Saunders, K. L., Quick, G. I., & Collins, C. E. (2010). The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutrition, 13(11), 1931–1940.

- Muth, N. D., Chatterjee, A., Williams, D., Cross, A., & Flower, K. (2008). Making an IMPACT: Effect of a school-based pilot intervention. North Carolina Medical Journal, 69(6), 432–440. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.69.6.432

- Nasution, S. Z., Pulungan, S. W., Siregar, C. T., Ariga, R. A., Lufthiani, & Amal, M. R. H. (2021). Pattern of family care and food consumption of primary school students in medan, Indonesia. AIP Conference Proceedings 2342, 120005. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0045734

- Oke, S., & Tan, M. (2022). Techniques for advertising healthy food in school settings to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 59, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580221100165

- Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., Castillo, M. J., & Sjöström, M. (2008). Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: A powerful marker of health. International Journal of Obesity, 32(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774

- Panunzio, M. F., Antoniciello, A., Pisano, A., & Dalton, S. (2007). Nutrition education intervention by teachers may promote fruit and vegetable consumption in Italian students. Nutrition Research Review, 27(9), 524–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2007.06.012

- Parcel, G. S., Simons-Morton, B., O’hara, N. M., Baranowski, T., & Wilson, B. (1989). School promotion of healthful diet and physical activity: Impact on learning outcomes and self-reported behavior. Health Education Quarterly, 16(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818901600204

- Parmer, S. M., Salisbury-Glennon, J., Shannon, D., & Struempler, B. (2009). School gardens: An experiential learning approach for a nutrition education program to increase fruit and vegetable knowledge, preference, and consumption among second-grade students. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 41(3), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.002

- Pérez-Rodrigo, C., & Aranceta, J. (2001). School-based nutrition education: Lessons learned and new perspectives. Public Health Nutrition, 4(1a), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2000108

- Perry, C. L., Bishop, D. B., Taylor, G., Murray, D. M., Mays, R. W., Dudovitz, B. S., Smyth, M., & Story, M. (1998). Changing fruit and vegetable consumption among children: The 5-a-Day Power Plus Program in St. Paul, Minnesota. American Journal of Public Health, 88(4), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.4.603

- Perry, C. L., Mullis, R., & Maile, M. (1985). Modifying eating behavior of children: A pilot intervention study. The Journal of School Health, 55(10), 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1985.tb01163.x

- Powers, A. R., Struempler, B. J., Guarino, A., & Parmer, S. M. (2005). Effects of a nutrition education program on the dietary behavior and nutrition knowledge of second-grade and third grade students. The Journal of School Health, 75(4), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.tb06657.x

- Purwadarminta, W. J. S. (2008). Kamus Umum Bahasa Indonesia. Balai Pustaka.

- Purwani, E., & Muwakhidah, M. (2016). Peningkatan Pengetahuan Anak SD melalui Edukasi Gizi tentang Makanan Jajanan Sehat dan Gizi Seimbang dengan Media Buku Cerita Bergambar di SD Tiyaran 01 dan 03 Sukoharjo. WARTA LPM, 19(2), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.23917/warta.v19i2.2754

- Puskur, K. (2009). Pengembangan dan Pendidikan Budaya & Karakter Bangsa: Pedoman Sekolah. Puskur.

- Quinn, L. J., Horacek, T. M., & Castle, J. (2003). The impact of COOKSHOP on the dietary] habits and attitudes of fifth graders. Topics in Clinical Nutrition, 18(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008486-200301000-00006

- Resnicow, K., Davis, M., Smith, M., Baranowski, T., Lin, L. S., Baranowski, J., Doyle, C., & Wang, D. T. (1998). Results of the TeachWell worksite wellness program. American Journal of Public Health, 88(2), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.2.250

- Reynolds, K. D., Franklin, F. A., Binkley, D., Raczynski, J. M., Harrington, K. F., Kirk, K. A., & Person, S. (2000). Increasing the fruit and vegetable consumption of fourth graders: Results from the high 5 project. Preventive Medicine, 30(4), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1999.0630

- Ronitawati, P., Sitoayu, L., Nuzrina, R., Melani, V., Prabowo, M. D. Y., Budiarti, T., & Nabilah, A. (2020). Edukasi Bekal Sehat Berdasarkan Prinsip Seimbang dengan Media “Isi Bekalku” pada Siswa Sekolah Dasar. JMM (Jurnal Masyarakat Mandiri), 4(3), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.31764/jmm.v4i1.1773

- Sahertan, I., & Imron, A. (1996). Hubungan antara Tingkat Keterlibatan Orang Tua dalam Mendidik Anak Kaitannya dengan Motivasi dan Prestasi Belajar SD SD se Kacamatan Lowok Waru Kodya Malang. Lembaga Penelitian IKIP Malang.

- Sahota, P., Rudolf, M. C., Dixey, R., Hill, A. J., Barth, J. H., & Cade, J. (2001). Randomised controlled trial of primary school based intervention to reduce risk factors for obesity. The BMJ, 323(7320), 1029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1029

- Sandercock, G. R. H., Voss, C., & Dye, L. (2010). Associations between habitual school-day breakfast consumption, body mass index, physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in English schoolchildren. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(10), 1086–1092. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2010.145

- Shannon, B., & Chen, A. N. (1988). A three-year school-based nutrition education study. Journal of Nutrition Education, 20(3), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3182(88)80229-2

- Shloim, N., Edelson, L. R., Martin, N., & Hetherington, M. M. (2015). Parenting styles, feeding styles, feeding practices, and weight status in 4–12 year-old children: A systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01849

- Siangchokyoo, N., Klinger, R. L., & Campion, E. D. (2020). Follower transformation as the linchpin of transformational leadership theory: A systematic review and future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(1), 101341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101341

- Simons-Morton, B. G., Parcel, G. S., Baranowski, T., Forthofer, R., & O’hara, N. M. (1991). Promoting physical activity and a healthful diet among children: Results of a school-based intervention study. American Journal of Public Health, 81(8), 986–991. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.81.8.986

- Smolak, L., Levine, M. P., & Schermer, F. (1998). A controlled evaluation of an elementary school primary prevention program for eating problems. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 44(3–4), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00259-6

- Solikah, S. N. (2018). Upaya Peningkatan Kesadaran Perilaku Hidup Bersih dan Sehat pada Anak Usia Skeolah (SD). GEMASSIKA, 2(1), 56–64.

- Spiegel, S. A., & Foulk, D. (2006). Reducing overweight through a multidisciplinary school-based intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md), 14(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.11

- Syafitri, Y., Syarief, H., & Baliwati, Y. F. (2009). Kebiasaan Jajan Siswa Sekolah Dasar (Studi Kasus di SDN Lawanggintung 01 Kota Bogor). Jurnal Gizi Dan Pangan, 4(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.25182/jgp.2009.4.3.167-175

- Tanaka, C., Tremblay, M. S., Okuda, M., & Tanaka, S. (2020). Association between 24-hour movement guidelines and physical fitness in children. Pediatrics International, 62(12), 1381–1387. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.14322

- Taylor, R. W., McAuley, K. A., Barbezat, W., Strong, A., Williams, S. M., & Mann, J. I. (2007). APPLE Project: 2-y findings of a community-based obesity prevention program in primary school–age children. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 86(3), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.3.735

- Te Velde, S. J., Brug, J., Wind, M., Hildonen, C., Bjelland, M., Perez-Rodrigo, C., & Klepp, K. -I. (2008). Effects of a comprehensive fruit-and vegetable-promoting school-based intervention in three European countries: The Pro children study. The British Journal of Nutrition, 99(4), 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711450782513X

- Ulfatin, N., Imron, A., & Mukadis, M. (2010). Profil wajib wajib belajar 9 tahun dan upaya penuntasannya. Journal Ilmu Pendidik, 17(1), 36–45.

- Ulya, N. (2003). Analisis Deskriptif Pola Jajan dan Kontribusi Zat Gizi Makanan Jajanan Terhadap Konsumsi Sehari dan Status Gizi Anak Kelas IV, V, dan VI SD Negeri Cawang 05 Pagi Jakarta Timur Tahun 2003. Fakultas Kesehatan Masyarakat, Universitas Indonesia.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2013). Making education a priority in the post-2015 development agenda. UNESCO.

- Ventura, A. K., & Worobey, J. (2013). Early influences on the development of food preferences. Current Biology, 23(9), R401–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.037

- Verdonschot, A., de Vet, E., van Rossum, J., Mesch, A., Collins, A. E., Bucher, T., & Annemien Haveman-Nies, A. (2020). Education or Provision? A comparison of two school-based fruit and vegetable nutrition education programs in the Netherlands. Nutrients, 12(11), 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113280

- Verdonschot, A., Follong, B. M., de Vet, E., Haveman-Nies, A., Collins, C. E., Prieto-Rodriguez, E., Miller, A., & Bucher, T. (2021). Assessing teaching quality in nutrition education: A study of two programs in the Netherlands and Australia. International Journal of Educational Research, 2, 100086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100086

- Vogt, W. P. (2005). Dictionary of statistics and methodology. Sage Publications.

- Wiyono, B. B., & Imron, A. (2010). Laporan Evaluasi Pelaksanaan Ujian Akhir Berstandar Nasional untk Indonesia Wilayah Timur. Ditjen Dikdasmen, kemendiknas.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). European food and nutrition action plan 2015-2020. WHO. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/294474/European-FoodNutrition-Action-Plan-20152020-en.pdf (accessed 5 August. 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Global standards for health promoting schools. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/health-promoting-schools/global-standards-for-health-promoting-schools-who-unesco.pdf

- Zaqout, M., Vyncke, K., Moreno, L. A., De Miguel-Etayo, P., Lauria, F., Molnar, D., Lissner, L., Hunsberger, M., Veidebaum, T., Tornaritis, M., Reisch, L. A., Bammann, K., Sprengeler, O., Ahrens, W., & Michels, N. (2016). Determinant factors of physical fitness in European children. International Journal of Public Health, 61(5), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0811-2