?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In the framework of the sustainable development goals, this study aims to answer the question of how the higher degree of gender inequality may affect children’s health. Study findings confirm statistically significant associations (P-value <0.001) between Gender Inequality Index (GII), and children’s health. It reveals that more than 33% of the variation in immunization rate in children under the age of five is explained by the rate of inequality between genders. This rate is relatively higher for the other studied variables. For example, 76% of the variation in the prevalence of anaemia in children is explained by the rate of inequality between genders, and almost 75% and 80% of the crude birth rate and neonatal mortality rate, respectively, are explained by rate of the inequality between genders. We further study the impact of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, as an index of national wealth, on GII. Results indicate that almost 76% of the variation in GII is explained by countries’ GDP per capita. This might shed some lights on the importance of gender equality in labour force participation, and narrowing the gap in gross salaries between women and men.

1. Introduction

By many sociologists, gender is considered a social construct that outlines roles, behaviours, activities, cultural conventions, and attributes assigned to different genders (Veas et al., Citation2021). The GII provides insights into gender disparities, and measures the inequality between women and men in several aspects, such as: reproductive health (maternal mortality, adolescent birth rate), empowerment (at least some secondary education, share of seats in parliament), and involvement in the labour market (Dijkstra & Hanmer, Citation2000; Lee, Citation2022). It is also designed to capture women’s disadvantage in the mentioned three dimensions for as many countries as data of reasonable quality allow (Gaye et al., Citation2010). The GII ranges between 0 and 1, where a lower level of GII indicates lower inequality between women and men, and vice-versa (Gaye et al., Citation2010; Marphatia et al., Citation2016). There has been a great progress in balancing the advantages between genders in the past 20 years (UNDP, Citation2022), as most regions have reached gender parity in primary education and in the labour market. However, there are still large inequities in some regions, where women face systematic denial in comparison with men (Veas et al., Citation2021). For example, in agrarian societies, men have mostly greater control over the ownership of lands. Apart from agricultural society, women in any other paid employment account for 41%, and spend more time performing unpaid work (Adeosun & Owolabi, Citation2021). It is also reported that the COVID-19 pandemic caused an increase in the gender inequality in terms of total hours worked (Farré et al., Citation2022). A similar study in Germany revealed that COVID-19 pandemic had a stronger influence on women than men, as the paid work hours were reduced, and worries about childcare were increased for women (Czymara et al., Citation2021). As reported by Tvedten (Citation2012), in poor countries men usually have more power within the communities and inside families than women, and men-headed families are in better economic position than women-headed households. Gender inequalities influence access to fundamental human rights, including nutrition, education, employment, health care, autonomy and freedom (Veas et al., Citation2021). Mawere (Citation2012), argues that gender inequality may result in a higher weight of household duties on girls as well as unequal involvement of girls in learning due to social penalties in inconsistency of schooling or in favour of early age marriage or early age pregnancy.

The present study explores possible associations between GII and children’s health, focusing on childhood immunization level, neonatal mortality rate, crude birth rate, and prevalence of anaemia in children under the age of five, based on publicly available data from 161 countries. By focusing on the relationship between GII and the health of children, this study aims to increase the awareness of how the gender equality would shift the global burden of health issues for the next generation.

1.1. Literature review

The achievement of gender equality by 2030 is the fifth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) adopted by the United Nations (UNDP, Citation2022). Gender inequality is still a key barrier to human development. Although women have made major strides since 1990, they still suffer from gender inequity, resulting in being discriminated against health, education, and political representation (Gaye et al., Citation2010). For example, a recent study by Kennedy et al. (Citation2020) revealed that young women face extensive disadvantage in relation to reproductive health, with high rates of child marriage, fertility, and domestic violence in low-income countries. The GII is reported as a helpful index for measuring human development, as it measures losses in human development in case of the societal gender inequality (Lee, Citation2022). Country-level evidences show how investments in women and girls can promote long-term prospects for future growth and human development (Permanyer & Solsona, Citation2009). Several studies have reported how gender inequality has an impact on women’s health at the country level. For example, Yu (Citation2018) found that women suffer mentally more than men in societies with greater levels of gender inequality. Similarly, Kolip and Lange (Citation2018), concluded that gender inequality is positively correlated to the health of women, when considering gender gap in life expectancy, and GII.

Several studies reported that gender inequality affects children’s health and their survival through many direct and indirect pathways (Bhalotra & Rawlings, Citation2011; Chirowa et al., Citation2013; Dey & Chaudhuri, Citation2008; Iqbal et al., Citation2018). Iqbal et al. (Citation2018), studied an association between GII and low birth weight, child malnutrition, and child mortality based on statistical analyses of 96 countries and revealed that 41% of the variance in child mortality is related to GII, when adjusting for GDP. A research on the associations between gender inequality, health expenditure, and maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa highlighted that countries with higher GII were associated with higher maternal mortality ratios, though countries that spend more on health were associated with lower maternal deaths than the countries that spend less on health (Chirowa et al., Citation2013). A cross-sectional study in West Bengal showed the differences in nutritional status of under-five children, and it determined that 55.9%, 51.4% and 42.3% of the girls were underweight, stunted and wasted, respectively, compared to 46.6%, 40.5% and 35.3% of the boys (Dey & Chaudhuri, Citation2008). A study by Brinda et al. (Citation2015) claims that GII is positively associated with neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates. A similar study by Iqbal et al. (Citation2018) showed that worldwide, gender inequality is associated with increased child mortality (either as under-five child mortality rate ratio, or as excess female mortality per 1000 live births), and with higher prevalence among girls. On the other hand, simulations revealed that reducing GII would lead to major reduction in infants’ low birth weight, child malnutrition and child mortality in low- and middle-income countries (Marphatia et al., Citation2016). Bhalotra and Rawlings (Citation2011), explored the intergenerational persistence of health across time and region as well as across the distribution of maternal health. They used micro-data on 2.24 million children born of 0.6 million mothers in 38 developing countries over 31 years, and found a positive relationship between maternal and child health across the indicators. A study by Homan (Citation2017) investigated the relationship between political gender inequality in state parliament rates and state infant mortality rate in the United States from 1990 to 2012, where the results indicated that a higher proportion of women in state parliaments is associated with decreased infant mortality rates by 14.6%, both between states and within-states over time. Further, several studies reported wage inequality, and large differences in salary between men and women (Boll & Lagemann, Citation2018; Choudhury et al., Citation2000; Lo Sasso et al., Citation2020). Wage inequality may cause health disparities which directly affect adults and children’s health, morbidity and mortality rates, or exacerbate the health-poverty trap (Khullar et al., Citation2018).

1.1.1. Immunization level of infants

The World Health Organization (WHO) in their 2020 report declared that 17.1 million infants did not receive an initial dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine, and due to a lack of access to immunization and other health services, only an additional 5.6 million infants have been partially vaccinated. Approximately 23 million children under the age of 1 year did not receive basic vaccines in 2020, which is the highest number since 2009. There are several factors that play an important role in children’s immunization rates. For instance, Muhammad (Citation2014) studied the association between a child immunization aged 12–23 months, and the household socio-demographic variables, and the results indicate that child’s gender, the residence of the child, the parents’ education level, household income, and family size play a significant role in child immunization level. Similar study by Bernabe (Citation2021) examined the relationship between child’s gender, parent’s educational achievement, household wealth index, religion, ethnicity/language, urban-rural residency, and province/region with the child’s full immunization status in Mozambique, and their results revealed that parent’s educational achievement, household wealth index, religion, ethnicity/language, and province/region are significant factors affecting child’s full immunization status. A cross-sectional study among 380 parents or caretakers of children less than 2 years of age showed that immunization completion was correlated with marital status and age of the parents, age of the child, gender of the child, place of delivery of the current child, and the knowledge of what immunization is (Nakabuye, Citation2018). Östlin et al. (Citation2006) reported that health promotion campaigns regarding the importance of child immunization addressed to the family as a whole resulted in men taking greater responsibility for their children’s health, leading to increased vaccination rates, and earlier immunization. Oladepo et al. (Citation2021) observed that a reminder SMS sent to mothers of infants with phone ownership in rural communities on full and timely completion of routine immunization helped to improve immunization delivery. They recommend the integration of this method into the health system to increase national immunization coverage in developing countries.

However, there has not been a study conducted on how gender inequality may influence children’s health considering their immunization level. It would be of great importance to improve the existing literature focusing on this new aspect. Understanding the patterns in gender inequality levels in different regions and their possible relationship with children’s immunization level, would be a considerable contribution to the improvement of children’s health.

1.1.2. Prevalence of anaemia in children under the age of five

As reported by WHO (Citation2019), iron deficiency leads to anaemia, which has a prevalence of 39.8% in children aged 6–59 months, being equal to 269 million children worldwide. In early childhood, anaemia can cause low oxygenation of brain tissues, which may lead to impaired cognitive function, growth and psychomotor development (Santos et al., Citation2011). A study by Brotanek et al. (Citation2008) measured the prevalence of anaemia among one-year-old children in the USA over 26 years, and revealed that iron deficiency prevalence in US toddlers has not changed in the last 26 years. As reported by Lee (Citation2022), anaemia in children is affected by underlying factors of food insecurity, inadequate maternal and child care practices, as well as poor health environments. Usually, women are the primary caregivers for their children in most societies, and are responsible for their feeding practices (Smith et al., Citation2003). However, in societies where women have low power, it is more difficult to acquire the knowledge and skills to meet the best care practices for children (Smith et al., Citation2003).

1.1.3. Crude birth rate

According to WHO (Citation2019), the crude birth rate is the number of live births happening amongst the population during a given year, per 1000. As reported by several studies, in low-income countries such as South Africa, more than 30% of teenage girls fall pregnant, while almost 70% of the pregnancies among the teenage girls are unplanned (Wet et al., Citation2018; Willan, Citation2013). The teen birth rates are defined as the number of live births per 1000 women ages 15–19 years old (Murphy et al., Citation2013). A study on the association between income inequality and teenage pregnancy showed that teenage pregnancy rates are higher among girls who are living in disadvantaged communities and who are experiencing persistent poverty and lack of economic opportunities (Taylor-Jones, Citation2017). Several studies show that less educated teenage girls are more likely to get pregnant. Considering education inequality, teen mothers’ education is estimated to be approximately 2 years shorter compared to women who delay childbearing until the age of 30. Moreover, teenage mothers are less likely to complete high school and are less likely to attend college (Basch, Citation2011; Taylor-Jones, Citation2017). However, there has not been work conducted on how higher gender inequality may cause higher pregnancy rates. Thus, it is worth studying gender inequality levels in different regions and understand how the pregnancy level, and crude birth rate would be affected by a higher degree of gender inequality.

1.1.4. Neonatal mortality rate

As reported by UNICEF (Citation2023), the neonatal period is the first 28 days of life, which is the most vulnerable time for an infant’s survival. It has been reported that children face the highest risk of dying in their first month of life globally, and approximately 2.3 million children died in the first month of life in 2021, which corresponds to 6400 neonatal deaths every day. The association between gender inequality and child mortality rates has been reported in several studies. For example, as discussed by (Abdollahpour et al., Citation2022; Brinda et al., Citation2015), gender inequality is positively associated with neonatal, infant and under five years old mortality rates. A study by Rarani et al. (Citation2017), indicated that socio-economic inequality such as mother’s education, household’s economic status, availability of skilled birth attendants, mother’s age at the delivery time, and using modern contraceptives were associated with neonatal mortality rate.

This research aims to provide more insights to the relationship between GII and children’s health across 161 countries, using publicly available data. We further aim to study the impact of GDP per capita on GII. In particular, we seek to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Countries with higher level of gender inequalities are more likely to experience poor children’s health (measured through childhood immunization level, neonatal mortality rate, crude birth rate, and prevalence of anaemia).

Hypothesis 2: Countries with higher GDP per capita (as an index of national wealth) are more likely to experience lower level of gender inequalities.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

In the present study, we analyse the linkages between the GII, the immunization level, crude birth rate, neonatal mortality rate and anaemia among infants. Besides that, we also study the linkage between GII and GDP per capita. The immunization coverage rate of infants is defined by WHO (Citation2022) as the percentage of children aged 12–23 months who have received three doses of the combined diphtheria, tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DPT) vaccine in a given year. Neonatal mortality rate is defined by the WHO (Citation2022) as the number of deaths during the first 28 completed days of life per 1000 live births in a given year. The prevalence of anaemia among children aged 6–59 months is defined by the WHO (Citation2022) as the percentage of children whose haemoglobin level is less than 110 grams per litter, adjusted for altitude. GDP per capita is defined by the World Bank (Citation2022) as the index of national wealth per capita. The datasets containing the measurements of the five variables of our interest (immunization level, crude birth rate, neonatal mortality rate, anaemia and GDP) from 161 countries assessed in 2019 are publicly available at the official World Health Organization and World Bank sources.

2.2. Statistical analysis

First, we explore the descriptive statistics of the dataset, which includes 161 observations of the five continuous variables listed above. We analyse the pairwise correlation between these variables and the variance inflation factor (VIF), in order to decide whether any of the variables should be excluded from the analysis. We further explore the data based on previously suggested thresholds of low, medium, and high gender inequality index (Gaye, Citation2010), and by considering an appropriate sample size. We study the distribution of the data with the help of box plots for the four variables related to children’s health. With the help of the regression analysis, we explore whether the GII has any impact on children’s health, and if so, to what extent. We also analyse whether GDP per capita is a significant factor in affecting the GII in developed and undeveloped countries. Regression analysis is a statistical method that investigates the relationship between variables in a nondeterministic fashion (Devore, Citation2011). The process of performing a regression analysis allows us to confidently examine how a response variable changes as the value of predictor variable is changed. As reported by Myrskylä et al. (Citation2011), the quadratic regression model (1) is more accurate to model the relationship between the dependent variables (immunization rate at early childhood, neonatal mortality rate, crude birth rate, and prevalence of anaemia), and the independent variable (GII). In the quadratic model

Y represents the dependent variable, X represents the independent variable, is the quadratic form of the independent variable and

is the error term. We estimate the parameters

,

and

. We analyze the standard error of the estimates and the coefficient of the determination (

). The value of

helps in determining the degree to which the variation in the dependent variable can be explained by independent variables.

3. Results

We conduct the data analyses by using R-Studio (version 4.0.3). Descriptive statistics of the studied variables based on data from 161 countries are summarized in Table . There are five variables of interest: the GII, the immunization of children, anemia among children, crude birth rate and the neonatal mortality rate. All variables are continuous. We can observe that the average GII is 0.34, while the lowest GII is 0.03, indicating a negligible ratio of inequality between genders. The highest GII is 0.8, indicating a very high level of inequality between genders.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables

The analysis of the relationship between variables using the Pearson correlation coefficient reveals a strong negative correlation between the immunization of children and the other variables, with a correlation coefficient less than −0.4. However, the variance inflation factor (VIF) for every variable is less than 1.5, suggesting that none of the variables should be excluded from the analysis.

Based on the GII thresholds reported by (Gaye, Citation2010), values below 0.280 indicate a very low ratio of inequality between genders, while 0.512 is the threshold indicating a medium level of inequality between genders, and the values of GII above 0.674 indicate a high ratio of inequality between genders. The categorized data of the selected countries considering these thresholds are summarized in Table . There are three countries with critically high value of GII, 34 countries have a high value of GII (between 0.512 and 0.673). Most of the selected countries (123) have low (between 0.281 and 0.511) or very low (less than 0.280) GII values reported.

Table 2. Summary statistics for categorized GII, high, medium, low and very low

By using the referred thresholds, only three countries would be in the category of high GII, what might bias the further analyses. To overcome this issue, we categorize the GII only as high (above 0.512) and low (below 0.512). The number of countries in these two categories is more balanced (N = 37 and N = 123, respectively). The results of the t-test show a statistically significant difference in the average values of all variables between the high and low GII categories (P-values <0.001). We can observe that the average immunization is higher in countries with low GII. In countries with high gender inequality, anemia among children occurs much more frequently than in countries with low GII. The crude birth rates and neonatal mortality rates are much higher in countries with high gender inequality than in countries with low level of inequality between the genders.

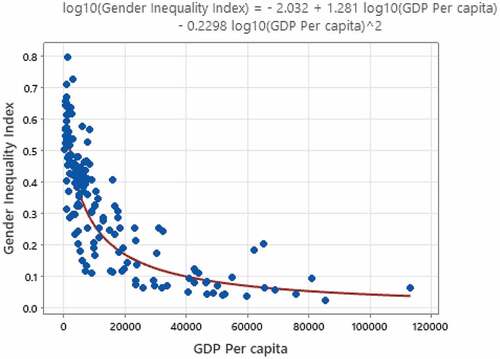

The results of the regression analysis are reported in Table , showing that the GII is significantly associated with the rate of immunization in early childhood, neonatal mortality rate, crude birth rate, and prevalence of anemia in children (at the significance level of 0.05). The findings for immunization levels reveal that more than 33% of the variation in immunization rate in infants is explained by the rate of inequality in genders. This rate is relatively higher for the other studied variables. We can observe that 76% of the variation in the prevalence of anemia among children is explained by the rate of the inequality between genders, and almost 75% and 80% of the crude birth rate, and neonatal mortality rate, respectively, are explained by the rate of the inequality between genders.

Table 3. Regression models for immunization rate, anemia, crude birth rate and neonatal mortality

Figure shows the association between GII and the childhood immunization rate, prevalence of anemia, crude birth rate and neonatal mortality rate. With the help of the fitted lines, we can observe that immunization is inversely associated with GII, while the other three variables show a positive association with GII.

Figure 1. Association between GII and childhood immunization rate, prevalence of anemia, crude birth rate and neonatal mortality rate.

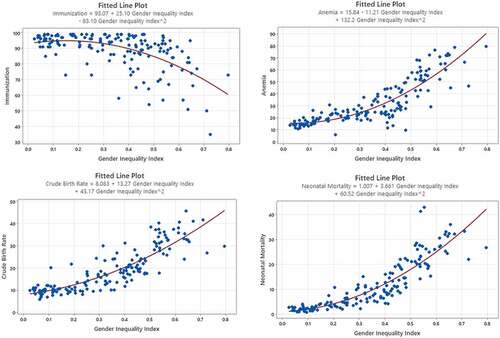

As Figure shows, there is a curvilinear negative relationship between GDP per capita and GII. The graph also confirms that wealthy countries with higher GDP per capita are experiencing lower inequality between genders.

The results of the log-log quadratic regression show a significant association (P-value <0.001) between GII and GDP per capita. We found out that almost 76% ( of the variation in GII is explained by GDP per capita (S.E. = 4.555).

4. Discussion

The achievement of gender equality is one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), which is crucial to accelerating sustainable development. In the present work, we study the GII as defined by UNDP, which captures gender inequality in three different dimensions: reproductive health, political empowerment, and economic status. GII is a fundamental dimension of human development; however, the number of scientific literature on how gender equality would shift the global burden of health issues for the next generation is not many. Therefore, it is of great importance to explore the associations between GII and children’s health. We analyzed the link between GII and children’s health considering the rate of childhood immunization, the prevalence of anemia, crude birth rate, and neonatal mortality rate. We built a quadratic regression model for all four variables related to children’s health. Based on this regression analysis, the findings for immunization levels reveal that more than 33% of the variation in immunization rate in children under the age of 5 is explained by the rate of inequality between genders. This rate is relatively higher for the prevalence of anemia, for crude birth rate, and for neonatal mortality rate. We found out that 76% of the variation in the prevalence of anemia in children is explained by the rate of inequality between genders. Also, a high percentage of crude birth rate and neonatal mortality rate (almost 75% and 80%, respectively) are explained by the rate of inequality between genders. Furthermore, our results also highlight that GDP per capita is a significant factor that affects the level of GII in both developed and undeveloped countries. Almost 76% of the variation in the gender inequality index is explained by GDP per capita. These findings indicate the importance of the involvement of women in the labor market and highlight the added value of their participation.

High level of gender inequality harms children’s health in several direct and indirect ways. There have been various studies conducted in this matter that have shown that GII affects infants’ low birth weight, child undernourishment and child mortality rate (Dey & Chaudhuri, Citation2008; Iqbal et al., Citation2018). However, there has not been any work conducted on how gender inequality may have an impact on children’s immunization level, the prevalence of anemia among infants, or crude birth rate. Thus, the present work is of great importance, as it contributes to the existing literature by discovering significant associations between the gender inequality index and children’s health.

5. Conclusion

Our study highlights the importance of societal gender equality by examining the link between GII and children’s health based on data from 161 developed and developing countries. We have documented statistically significant associations between GII and children’s health. In other words, when one gender fares poorly in all three measured dimensions of reproductive health, political empowerment, and economic status, then they are more likely to have children with anemia, higher level of pregnancies and birth rate, neonatal mortality rates, and are more likely to neglect their kids’ immunizations. As this study focuses on the relationship between GII and the health of children, it increases the awareness of need for social changes all around the world. Any effort to promote a balanced level of gender equality in the societies would have substantial benefits for children’s health and survival.

Besides children’s health, we considered another important aspect for GII, the index of national wealth expressed in terms of gross domestic product per capita. We studied the association between GDP per capita and GII, and identified a negative relationship between them. The results of our analyses indicate that increasing the equality in employment rate, and narrowing the gap in gross monthly salaries between women and men, which have a positive impact on economic growth in societies, would lead to the lower level of GII.

The GII measures losses in human development as a result of societal gender inequality (Gaye et al., Citation2010), thus systematic oppression of women’s rights of freedom and opportunities might lead to inconsistencies in the human development. Despite the economic growth over the past decades, standard indicators, such as the GDP per capita, the Human Development Index, or the Gender Development Index, reveal that still many countries around the world remain undeveloped (Tvedten, Citation2012). Even though poverty reduction and gender equality have been prioritized on the political agenda in many countries, in terms of GII, there are still several countries that need improvement.

As our study shows, gender inequality is strongly linked to children’s health; therefore, it is of high importance to balance the social and economic advantages between genders, to be able to raise a healthier generation. According to (Gaye et al., Citation2010) investing in the development and promotion of gender equality would actively contribute to long-term prospects in human development. Thus, gender equality can lead to an increment in added value in the labor market as well as in global economy. Based on the results of the statistical analyses, we recommend improvements in diminishing child mortality rates. Such initiatives should prioritize women’s rights and autonomy, and eliminate gender barriers. Advancements in the social well-being of women may augment the survival of children of both genders. Due to the scarcity of literature focusing on the discovery of links between GII and children’s health, our findings also greatly contribute to the development of policies regarding women empowerment. Our results suggest improvements in raising the awareness of a need for a social change. Mainly, promoting and supporting women’s access to economic and social resources, and providing means for a higher level of participation of women in decision-making.

5.1. Recommended policies

GII is unique in its focus on critical issues of educational attainment, economic and political participation, and in considering overlapping inequalities at the country level. Thus, it includes key advancements in existing global measures of gender equity. The GII is aimed at providing empirical foundations for policy analysis and advocacy efforts, as it highlights women’s disadvantage in three dimensions in different nations (Gaye et al., Citation2010).

Reviewing the social indicators around the world—albeit improving—reveal that in many undeveloped and developing countries, women are still not equal to men in terms of education, health and some forms of abuse (Veas et al., Citation2021). The present study proposes the following actions for eliminating gender equality barriers:

Our results suggest that without barriers in gender equality the survival of more children would be possible. As reported by Choudhury et al. (Citation2000) in some undeveloped countries where patriarchal societies are dominant, and women suffer from lack of basic health care and face life-threatening health issues, the well-being of women should be highlighted and promoted. We argue that such societies need fundamental aid to raise their awareness about the importance of the well-being of women. Helping them to understand the need for a social change would lead to increased concern not only about the well-being of the women but also of their progeny.

Financially poor women might tend to avoid using health services due to the fear of health expenditures. This can lead to worse health standards of women, and mainly to the lack of preventive medical interventions. Mothers lacking economic autonomy, have more difficulties in managing their household finances to provide better nutrition and health conditions for their children. Improving public health, free access to fundamental health services, with focusing on mothers’ and infants’ health can help to avoid low birth weight, child malnutrition, anemia and maternal and child mortality. To achieve this goal, collaborations between health services and social initiatives should prioritize women autonomy.

Education and access to information are important factors in gender equality and the empowerment of women. Currently, a larger proportion of men than women have access to mass media information, particularly in undeveloped nations, and rural areas. Recent industrialization in developing economies reduces the employment opportunities of women, who lack higher education (Taylor-Jones, Citation2017). We argue that such societies demand more skills that are needed to lead an autonomous life. Therefore, education policies for women should emphasize developing skills. With the help of government expenditure on education of women, the economic growth of such countries could get accelerated, and consequently, it would help in preventing child mortality and to reduce the expenses on health services.

External political and economic process affect gender relations at the level of households and individuals with socially established outlines of power (Homan, Citation2017). This means that structural transformation in access to employment and income would significantly changes gender relation. Thus, the higher chance for women to make use of increased opportunities and advance their lives depend on their paid position in the household and their relations with men, increases the women’s social empowerment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sahar Daghagh Yazd

Sahar Daghagh Yazd is an Assistant Professor of Statistics in the College of Engineering and Technology at American University of the Middle East in Kuwait. She graduated with her PhD in applied statistics/health economics at the University of Adelaide, Australia.

She is also a senior project manager in ‘Guidelines and Economics Network International’ in Australia. She has extensive experience in statistical analyses and micro-econometric analysis of large-scale panel survey data. She is experienced in government report writing and was a co-author of government reports brokered by the Sax Institute for the New South Wales Ministry of Health. She has several peer-reviewed and conferences outputs in the research areas of health, water scarcity, and climate change. Her current research interests focus on the sustainable development goals in engineering and social sciences.

Melinda Oroszlányová

Melinda Oroszlányová is an Assistant Professor in the Statistics Department of the College of Engineering and Technology at the American University of the Middle East in Kuwait. She is an experienced data analyst, with a demonstrated history of working in diverse research fields including industry (chemical, high-tech, and fishery), environment, public health, information science, genetics, and banking. She has technical experience with statistical software (R, SPSS, SQL, Python), performing statistical analyses, statistical modelling (predictions, forecasting), clustering, classification, operational reconciliation, extracting and analysing information from data warehouses, etc. Her current research interests focus on the sustainable development goals in social sciences and industry.

Nilüfer Pekin Alakoç

Nilüfer Pekin Alakoç is an Assistant Professor of Statistics in the College of Engineering and Technology, American University of the Middle East in Kuwait. She graduated from Middle East Technical University in Turkey with a major in Statistics and a minor in Operations Research. She received her MSc degree in Industrial Engineering and her Ph.D. in Statistics. She has experience in teaching and statistical data analyses for more than 17 years. Her research interests mainly include statistical applications in engineering, optimization, scheduling, fuzzy logic in data analysis, quality control, regression, and time series analyses.

References

- Abdollahpour, S., Heidarian Miri, H., Khademol Khamse, F., & Khadivzadeh, T. (2022). The relationship between global gender equality with maternal and neonatal health indicators: An ecological study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 35(6), 1093–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1743655

- Adeosun, O. T., & Owolabi, K. E. (2021). Gender inequality: Determinants and outcomes in Nigeria. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, 1(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-01-2021-0007

- Basch, C. E. (2011). Teen pregnancy and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. The Journal of School Health, 81(10), 614–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00635.x

- Bernabe, K. G. (2021). Social/Cultural factors in preschool immunizations, Mozambique. Walden University.

- Bhalotra, S., & Rawlings, S. B. (2011). Intergenerational persistence in health in developing countries: The penalty of gender inequality? Journal of Public Economics, 95(3–4), 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.10.016

- Boll, C., & Lagemann, A. (2018). Gender Pay Gap im öffentlichen Dienst und in der Privatwirtschaft. Wirtschaftsdienst, 98(7), 528–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10273-018-2326-3

- Brinda, E. M., Rajkumar, A. P., & Enemark, U. (2015). Association between gender inequality index and child mortality rates: A cross-national study of 138 countries. Biomedical Central Public Health, 15(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1449-3

- Brotanek, J. M., Gosz, J., Weitzman, M., & Flores, G. (2008). Secular trends in the prevalence of iron deficiency among US toddlers, 1976-2002. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(4), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.4.374

- Chirowa, F., Atwood, S., & Van der Putten, M. (2013). Gender inequality, health expenditure and maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: A secondary data analysis. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 5(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.471

- Choudhury, K. K., Hanifi, M. A., Rasheed, S., & Bhuiya, A. (2000). Gender inequality and severe malnutrition among children in a remote rural area of Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 18(3), 123–130.

- Czymara, C. S., Langenkamp, A., & Cano, T. (2021). Cause for concerns: Gender inequality in experiencing the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany. European Societies, 23(sup1), S68–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1808692

- Devore, J. L. (2011). Probability and Statistics: For Engineering and the Sciences (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Dey, I., & Chaudhuri, R. N. (2008). Gender inequality in nutritional status among under five children in a village in Hooghly district, West Bengal. Indian Journal of Public Health, 52(4), 218–220.

- Dijkstra, A. G., & Hanmer, L. C. (2000). Measuring socio-economic gender inequality: Toward an alternative to the UNDP gender-related development index. Feminist Economics, 6(2), 41–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700050076106

- Farré, L., Fawaz, Y., González, L., & Graves, J. (2022). Gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during Covid‐19 times. Review of Income and Wealth, 68(2), 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12563

- Gaye, A., Klugman, J., Kovacevic, M., Twigg, S., & Zambrano, E. (2010). Measuring key disparities in human development: The gender inequality index. Human Development Research Paper, 46, 1–37.

- Homan, P. (2017). Political gender inequality and infant mortality in the United States, 1990–2012. Social Science & Medicine, 182, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.024

- Iqbal, N., Gkiouleka, A., Milner, A., Montag, D., & Gallo, V. (2018). Girls’ hidden penalty: Analysis of gender inequality in child mortality with data from 195 countries. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e001028. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001028

- Kennedy, E., Binder, G., Humphries-Waa, K., Tidhar, T., Cini, K., Comrie-Thomson, L., Vaughan, C., Francis, K., Scott, N., Wulan, N., Patton, G., & Azzopardi, P. (2020). Gender inequalities in health and wellbeing across the first two decades of life: An analysis of 40 low-income and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific region. The Lancet Global Health, 8(12), e1473–1488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30354-5

- Khullar, D., Chokshi, D. A., Orav, E. J., Zheng, J., Frakt, A., & Jha, A. K. (2018). Health, income, & poverty: Where we are & what could help. Health Affairs, 37(6), 864–872. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935

- Kolip, P., & Lange, C. (2018). Gender inequality and the gender gap in life expectancy in the European Union. European Journal of Public Health, 28(5), 869–872. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky076

- Lee, A. (2022). Associations between Women’s Empowerment, Infant and Young Child Feeding, and Child Anemia in Rural Senegal. Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies.

- Lo Sasso, A. T., Armstrong, D., Forte, G., & Gerber, S. E. (2020). Differences in starting pay for male and female physicians persist; Explanations for the gender gap remain elusive. Health Affairs (Millwood), 39(2), 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00664

- Marphatia, A. A., Cole, T. J., Grijalva-Eternod, C., & Wells, J. C. K. (2016). Associations of gender inequality with child malnutrition and mortality across 96 countries. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics, 1, e6. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2016.1

- Mawere, M. (2012). Girl child dropouts in Zimbabwean secondary schools: A case study of Chadzamira secondary school in Gutu district. International Journal of Politics and Good Governance, 3(3), 1–18.

- Muhammad, A. (2014). Relationship between child immunisation and household socio-demographic characteristic in Pakistan. Statistics, 4(7), 82–89.

- Murphy, S. L., Xu, J., Kochanek, K. D., Curtin, S. C., & Arias, E. (2013). National vital statistics reports. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61(4), 1–118.

- Myrskylä, M., Kohler, H. -P., & Billari, F. (2011). High development and fertility: Fertility at older reproductive ages and gender equality explain the positive link.

- Nakabuye, S. (2018). Factors Influencing Completion of the Immunization Schedule of Children Below 2 Years in Madu Community Gomba District. International Health Sciences University.

- Oladepo, O., Dipeolu, I. O., & Oladunni, O. (2021). Outcome of reminder text messages intervention on completion of routine immunization in rural areas, Nigeria. Health Promotion International, 36(3), 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa092

- Östlin, P., Eckermann, E., Mishra, U. S., Nkowane, M., & Wallstam, E. (2006). Gender and health promotion: A multisectoral policy approach. Health Promotion International, 21(suppl_1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal048

- Permanyer, I., & Solsona, M. (2009). Gender equality, human development and demographic trends: Are they jointly evolving in the right direction? African Population Studies, 23, 45–60.

- Rarani, M. A., Rashidian, A., Khosravi, A., Arab, M., Abbasian, E., & Morasae, E. K. (2017). Changes in socio-economic inequality in neonatal mortality in Iran between 1995-2000 and 2005-2010: An Oaxaca decomposition analysis. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(4), 219. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.127

- Santos, R. F. D., Gonzalez, E. S. C., Albuquerque, E. C. D., Arruda, I. K. G. D., Diniz, A. D. S., Figueroa, J. N., & Pereira, A. P. C. (2011). Prevalence of anemia in under five-year-old children in a children’s hospital in Recife, Brazil. Revista brasileira de hematologia e hemoterapia, 33(2), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.5581/1516-8484.20110028

- Smith, L. C., Ramakrishnan, U., Ndiaye, A., Haddad, L., & Martorell, R. (2003). The importance of women’s status for child nutrition in developing countries: International food policy research institute (IFPRI) research report abstract 131. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 24(3), 287–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482650302400309

- Taylor-Jones, M. (2017). A review of the social determinants of health-income inequality and education inequality: Why place matters in US teenage pregnancy rates. Health Systems and Policy Research, 4(2), 0. https://doi.org/10.21767/2254-9137.100071

- Tvedten, I. (2012). Mozambique country case study: Gender equality and development. World Development Report, 7778105–1299699968583.

- UNDP, (2022). Gender equality strategy 2022-2025. Retrieved at March 19, 2023 https://genderequalitystrategy.undp.org/

- UNICEF, (2023). Neonatal mortality. Retrieved at March 19, 2023 https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/neonatal-mortality

- Veas, C., Crispi, F., & Cuadrado, C. (2021). Association between gender inequality and population-level health outcomes: Panel data analysis of organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. EClinicalMedicine, 39, 39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101051

- Wet, N. D., Somefun, O., Rambau, N., & Puebla, I. (2018). Perceptions of community safety and social activity participation among youth in South Africa. PloS One, 13(5), e0197549. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197549

- WHO, (2019). Anaemia in women and children. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children. Retrieved at March 19, 2023.

- WHO, (2022). Immunization coverage. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage. Accessed at 19 March. 2023.

- Willan, S. (2013). Cape Town: Partners in Sexual Health.

- World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/home. Retrieved at December 18, 2022.

- Yu, S. (2018). Uncovering the hidden impacts of inequality on mental health: A global study. Translational Psychiatry, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0148-0