Abstract

Smallholder farmers have been on the receiving end of the impacts of climate change due to the direct dependence of their livelihood portfolios on climate-related systems. In northern Ghana, smallholder agriculture is predominantly rainfed, making crop farming very vulnerable to changes and variability in rainfall and other extreme climatic events. Therefore, this paper examined how smallholder farmers in north-western Ghana have been adapting to climate change over the years to sustain household food security. The study employed a qualitative research design, relying on qualitative methods of selection of participants, data collection and analysis. The findings show that smallholder farmers employ a diversity of adaptation strategies. These include setting up of multiple farms, changes in the techniques of raising mounds (gbaala) to flat ploughed lands (pari-jabing) for planting, adoption of improved maize varieties and crop diversification. Others include pro-poor community-based credit schemes for financing farmer innovations and feminised crop farming. The paper underscores that local knowledge plays a critical role in enabling livelihood diversification among rural farmers, especially under conditions of high levels of poverty. Drawing on the benefits from the synergies arising from employing a wide range of farm and non-farm strategies, the paper advocates for the mainstreaming of local knowledge, farmer asset and infrastructure bolstering initiatives into climate change adaptation planning at local and broader levels of policy formulation and implementation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Smallholder food crop farmers have suffered and continue to suffer in disproportionate manner the impacts of climate change over the years. This is because smallholder agriculture is predominantly rainfed in north-western Ghana, making it very vulnerable to changes and variability in rainfall and other extreme climatic events. Adaptation has become very necessary for smallholder farmers to sustain food crop production and food security. However, farmers have low adaptive capacities due to several socio-economic factors, and hence rely much on their own local knowledge systems to develop and implement a diversity of adaptation strategies to enhance household food production and food security. These localised strategies need to be mainstreamed into adaptation planning to achieve sustainability.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a global challenge that has existed for quite some decades, and it is, therefore, not new to the world (Nyong et al., Citation2007; Ogunyiola et al., Citation2022; Tripathi & Mishra, Citation2017). The worst is that future global temperatures are projected to increase by 2.5°C–3.2°C whiles future precipitation is forecasted to decrease by 9%–27% by 2100 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], Citation2014). The manifestation of these changes will have severe implications for global food production and water availability, which will affect millions of people on a varying scale in different locations. It will also have significant rippling effects on other sectors of the economies of developing countries (Alhassan et al., Citation2018). This is because the major livelihoods of the people in developing countries are ecosystem dependent and are much influenced by changes in weather elements. This is particularly the case for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries and Africa at large where smallholder farmers have low abilities to withstand increasing threats of climate change due to low education, low access to information, technology, and credit facilities (Aswani et al., Citation2018; Dumenu & Obeng, Citation2016). The threats of climate change are already significantly impacting on smallholder farming communities and food systems both directly and indirectly in SSA (Guodaar et al., Citation2021). There is increasing low yields of major staple food crops such as maize, yam, and sorghum across SSA.

In Ghana, climate change is manifesting in observed increases in temperatures, unpredictable rainfall (reduced and erratic pattern), recurrent incidence of floods and droughts, increased bushfire outbreaks, changing planting season, increased extinction of species and others (Guodaar et al., Citation2021; Nyadzi et al., Citation2021). The impact of these changes on rain-fed agriculture has been dire for Ghanaian smallholder farmers over the years because of their dependence on rain-fed agriculture and other ecosystem-related livelihoods (Alhassan et al., Citation2018; File & Derbile, Citation2020). This presents them with the option of adapting to climate change through local knowledge systems to complement science-based strategies (Muyambo et al., Citation2017; Nkomwa et al., Citation2014). That is, local knowledge plays critical role in adopting and applying strategies among smallholder farmers to sustain food crop production under climate change. Smallholder farmers have over the years developed several adaptation strategies through their own knowledge systems to adapt to the increasing threats of climate change. These strategies include crop rotation, intercropping, mulching, use of crop residues for manure, animal feed, fuelwood, soil and stone bunding, grass strip and composting (Nkegbe, Citation2018; Taye & Megento, Citation2017). According to Alam et al. (Citation2017), smallholder farmers also employ multiple cropping, no-tillage, natural rehabilitation, contour tillage, ridging, terracing, agroforestry, afforestation, and organic farming to enhance food crop production. These are both crop and soil management strategies and are commonly practiced among smallholder farmers in SSA (Nkegbe, Citation2018). Moreover, these strategies mostly vary from community to community and from one agro-ecological zone to another (Sahu & Mishra, Citation2013).

However, centralised planning in Ghana has not paid much attention to smallholder farmers’ knowledge and practices in adaptation planning to enhance mainstreaming local adaptation systems into district level development plans for effective climate change adaptation in northern Ghana (Atanga et al., Citation2017). Derbile et al. (Citation2019) observed that there is also little focus by researchers on the dynamics of local knowledge of smallholder farmers and their contributions to adaptation planning for sustainable agriculture in northern Ghana. Hence, the ingenuity and innovations of smallholder farmers in the adaptation discourse in North-western Ghana has not been extensively examined. Therefore, this paper examines how smallholder farmers, through their own knowledge, are adapting to climate change in the Sissala East Municipality in North-western Ghana.

2. Conceptual overview

2.1. Climate change and its impact on smallholder agriculture

The impacts of climate change continue to be daunting for smallholder agriculture and other related sectors which are rainfall dependent. More worrying is the increasing disproportionate nature of the impacts of climate change on vulnerable people who have low adaptive capacities to build resilience to climatic shocks and stresses (IPCC, Citation2014). The uncertainty, unpredictability, and variability of rainfall pattern in African, including sub-Saharan Africa pose significant adverse risks to smallholder farmers whose livelihoods are intricately related to the ecosystem and rainfall (Nyadzi et al., Citation2021). These communities are already faced with a myriad of challenges including poverty, limited access to land and related natural resources, marginalisation, low access to finance, and low education (Guodaar et al., Citation2021). These challenges are further worsened by the rising incidents of floods, droughts, windstorms, heatwaves, and pests and diseases which adversely affect food production in the form of declining yields of major food crops (Abdulai, Citation2022). Yields of major staple crops such as maize, rice, millet, cassava, and yam, and are projected to further decline, if necessary, actions against climate change are not taken (Ayanlade et al., Citation2017).

In northern Ghana smallholders are confronted with the twin vulnerability of exposure to extreme floods and droughts which are perpetuated by rainfall variability (Derbile et al., Citation2016). Recurrent and prolonged dry spells (droughts) and floods, coupled with increasing temperatures are adversely affecting smallholder agricultural systems and related livelihoods in the form of low yields and post-harvest losses (Guodaar et al., Citation2021). These are aggravating the levels of household poverty and food insecurity in northern Ghana. Annual floods in northern Ghana for example, are reported to have caused significant levels of soil erosion leading to poor soil fertility, degraded soil structure, siltation of rivers and other water reservoirs, and reduced soil depth which do not support high crop yields (Tesfahunegn et al., Citation2021). These are estimated to be exacerbated by the levels of social exclusion and inequality among smallholder farmers which affect their access to climate justice and participation in planning and implementation of climate-resilient initiatives (Nyadzi et al., Citation2021).

Climate change in north-western Ghana manifests in recurrent floods and droughts, erratic rainfall pattern, rising extreme day and night temperatures, and increasing emergence of crop pests and diseases which hitherto were not commonly known among smallholder farmers (Mwinkom et al., Citation2021; Yiridomoh et al., Citation2021). The impacts of these on food crop production have been adverse and translate in poor yields, low food production and inadequate household food supply (Derbile et al., Citation2022). The uncertainty in the onset of the rainy and farming season affects farmers’ planting decisions and many farmers mostly plant late leading to poor productivity. There is late onset and early cessation of the rainy season and has contracted the planting season, exposing farmers to the effects of recurrent droughts and floods. Consequently, smallholder farmers tend to adopt strategies that can enable sustain food production in the mist of these extreme challenges through their own knowledge systems.

2.2. Local knowledge and climate change adaptation

In most literature, local knowledge has been synonymously used with indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge, local ecological knowledge, traditional ecological knowledge, indigenous knowledge systems, indigenous technical knowledge, indigenous ecological knowledge (Aswani et al., Citation2018; Claxton, Citation2010; Derbile, Citation2010; Kumar, Citation2010). These are mostly used interchangeably to refer to the use of the day-to-day knowledge and knowledge systems of rural people and communities in making decisions on social, economic, and environmental matters (Derbile et al., Citation2019). Even though this paper sets out to use local knowledge, it does not relegate the other terminologies in terms of meaning and usage.

According to Mafongoya and Ajayi (Citation2017, p. 17), local knowledge is the “knowledge and know-how that is accumulated over generations and guides human societies in their innumerable interactions with their surrounding environment”. It is indicated that successive generations tend to renew these knowledge systems to enhance their abilities in achieving food security, environmental conservation, and effective early warning systems for predicting and managing disasters (Mafongoya & Ajayi, Citation2017). Local knowledge is the foundation for decision-making in traditional communities on matters of food security and building resilient livelihoods (Zoundji et al., Citation2017). It is also helpful in making socio-economic decisions among farmers which go beyond cultural values to serve as entry point for the external community to improve living conditions in rural communities (Nyong et al., Citation2007). There is evidence that many adaptation initiatives have failed and/or are duplicated in SSA due to neglect for incorporation of local knowledge (Haque et al., Citation2017; Tabbo & Amadou, Citation2017). This has not enhanced an effective engagement among smallholder farmers and scientists and experts to achieve effective integration of traditional and scientific agriculture (Aksoy & Öz, Citation2020). Literature shows that smallholder farmers in SSA including Ghana, have over the past years developed and implemented mechanisms and strategies to cope with the effects of extreme events through local knowledge systems (Derbile et al., Citation2019; Elum et al., Citation2017; Iloka, Citation2016; Kupika et al., Citation2019; Mafongoya & Ajayi, Citation2017; Muyambo et al., Citation2017; Ogunyiola et al., Citation2022). These knowledge systems and applications vary and/or have similarities relative to location, economic and socio-cultural backgrounds of smallholder farmers (Torres-Bagur et al., Citation2019). Drawing on local knowledge systems, smallholder farmers are able to predict and respond to extreme climatic events by observing changes in weather elements (rainbow, fog, direction of wind, and cloud formation), plants (shedding of leaves and flowering of some plants) and behaviour of birds and insects species (hornbill, ducks, grasshoppers, millipedes and frogs) (Ansah & Siaw, Citation2017; Dube & Munsaka, Citation2018; Kolawole et al., Citation2014; Muyambo et al., Citation2017). Smallholder farmers respond to the impacts of climate change through various adaptation strategies including mulching, mixed cropping, mixed farming, use of improved crop variety and animal breeds, change in planting dates, adoption of different farming methods, use of fertilizer and manure, backyard/dry season gardening, charcoal production and sale, and crop diversification (Alhassan et al., Citation2018; Derbile et al., Citation2019). Other adaptation strategies include remittances from migration, petty trading, local micro-finance, gathering and sale of forest products (Negeri & Demissie, Citation2017). Many of these strategies are formulated from farmers’ own knowledge systems (Dube & Munsaka, Citation2018) and maybe diversified within the context of productivist and conservationist approaches (Morton et al., Citation2017).

In North-western Ghana, farmers are adapting crop farming to climatic impacts through diversification irrespective of their educational levels, gender, and age (Derbile et al., Citation2019). It has been suggested that rural smallholder farmers are increasingly diversifying their livelihoods by adopting both farm and non-farm activities including migration to cope with and adapt to climate change (Jarawura, Citation2021). These are mostly internal mechanisms employed by rural households to sustain agricultural livelihoods and enhance food security.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study area

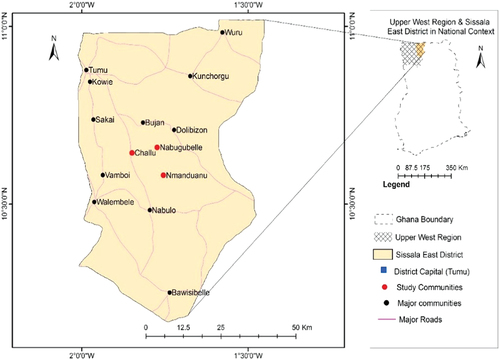

The Sissala East Municipal is one of the 11 administrative municipalities in the Upper West Region. It is located in the eastern part of the region with a population of 80,619 comprising of 39,868 male population and 40,751 female population (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], Citation2021). The municipality is predominantly agrarian, and the people are engaged in the cultivation of maize, groundnuts, soya, rice, beans, yams, cassava, and potatoes. Vegetables are also cultivated during the dry season along the rivers, dams, and valleys. Rearing of cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry is commonly engaged by households (Sissala East District Assembly [SEDA] Citation2018). The dependence on rainfed agriculture makes farmers more vulnerable to climatic variability. The municipality is within in the Guinea Savannah vegetation belt and experiences a single rainfall regime starting from March to October annually. Temperatures in the area are generally high with mean monthly temperatures ranging between 21ºC and 32ºC (GSS, Citation2014). The study was conducted in three purposively selected communities, namely, Challu, Nabugubelle and Nmanduanu as shown in Figure These communities are among the dominating farming communities in the municipality which contribute a significant proportion of grains, tubers, and other farm produce to the food needs of the municipality and the Upper West Region. The Sissala East Municipality was chosen for the study because of its significant contribution to food needs in the Upper West Region and northern Ghana at large. The land and soil are relatively fertile for food crop farming and other agricultural activities, and agricultural land is relatively availability and accessible to farmers for agricultural purposes.

3.2. Sampling procedure and methods of data collection and analyses

The study adopted the qualitative research approach and employed non-probability sampling techniques in the selection of the study participants. It also employed qualitative methods in the data collection and analysis. Firstly, we conducted in-depth interviews among 30 farming household heads in the three communities (10 household heads from each community). These household heads were purposively selected because they were considered to possess wealth of experience in farming accumulated over the years, according to preliminary interactions during community entry process. Household heads had over 20 years of farming experience as smallholder farmers and comprised 11 female heads and 19 male heads. The second level of in-depth interviews was conducted among 18 other key participants, which included chiefs (3), earth priests (Jantina) (3), indigenous chief farmers (3), and women leaders such as magazia (3). The others included leaders of women groups (3), and youth leaders (3). These persons were also targeted for their experience and knowledge in farming and related matters as leaders. Overall, the data collected centred on the experiences, knowledge, and observations of the interviewees on climate change and adaptation in relation to smallholder agriculture. The interviews were conducted in Sisaali and interactions were moderated using interview guide (See Appendix A).

In addition to the interviews, we also conducted nine (9) focus group discussions (FGDs) (3 FGDs in each community) among three categories of discussants in each community. These categories included the chiefs and council of elders, adult male farmers, and adult female farmers. We separated men groups from women groups for discussions to avoid the dominance of men in the discussions as it is common in northern Ghana (Derbile et al., Citation2022). The separation allowed each group members to freely express their views on the matters put forward. The number of discussants ranged between 6 and 12 per session (Bhattacherjee, Citation2012). An FGD guide (see Appendix B) was used to guide the discussions. These group discussions were relevant because they sparked in-depth discussions and analyses of local perspectives on how smallholder farmers were/are adapting to climate change in their respective communities. The researchers also made observations during interactions and on the farms of participants.

For purposes of trustworthiness of the qualitative data, the researchers ensured fairness among participants during engagements and never exhibited any bias towards any participants or group of participants during the data collection processes. The views and concerns of all participants were fairly captured and represented by the researchers during the data collection and analysis. The amount of time spent with participants during in-depth interviews and FGDs were the same and the same interview and FGD guides were used.

3.3. Ethical considerations

Participants’ consents were first sought by researchers before engagements. Participants were made to understand that the purpose of the study was purely academic and that their participations were voluntary. They were ensured of their confidentiality and anonymity. Audio recordings of conversations with participants were done by seeking the permission of participants and the researchers never used the names of participants.

4. Results

The results show a range of adaptation strategies employed by smallholder farmers in north-western Ghana mostly through their local knowledge. We have categorised these adaptation strategies into two levels of diversification as in Table .

Table 1. Categories of adaptation strategies

The farm-based strategies mostly concerned with direct farm practices while non-farm strategies are not related to farm practices. Many of these strategies were largely drawn from farmers’ own knowledge systems which were inherited from past generations and held as part of their culture and traditions. While on-farm adaptation measures have rather long history, non-farm measures except hunting and gathering, were relatively new. Although participants emphasised the rising importance of diversification in both areas, there was more concern about adding on non-farm strategies as these are not climate sensitive.

4.1. Farm-level adaptation strategies

The results from in-depth interviews and focus group discussions show that diversification in farmlands was a common practice among farmers. We found situations where farmers crop on different pieces of land with different landscape characteristics such as highlands, flat lands and lowlands or valleys to avert crop failure due to climate change. Farmers owned two or more farms concurrently in different locations which one is a new farm (locally called bakah fali) in addition to existing (old) farms, locally referred to as bakah bini. Both farms are in different places. An elder in Challu explained that

We have instituted bakah bini and bakah fali as a way of adapting to the variations in weather elements in different locations. We own farms in different locations where the land and forest (vegetation) are not the same. This is because the rainfall pattern, these days, is not reliable and highly discriminatory, it can be raining for farmers in one side while leaving out others on the other side of the same community. (in-depth interview)

A male household head in Nmanduanu, during an in-depth interview session, corroborated that;

The rains in recent years are not certain and cannot be predicted. The coverage is poor; rainfall is not evenly distributed in all locations. Another issue is that different lands have different characteristics for moisture retention and soil fertility. These are some of the issues we consider and engage in having more than one farm which are at different locations. (in-depth interview)

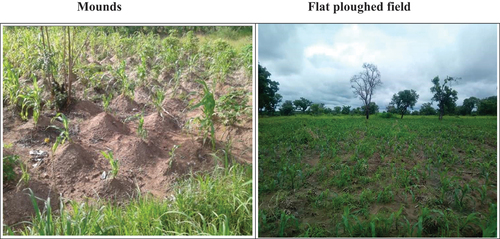

Also, there was a shift from the gbaala (mounds/ridging) to the parijabing (level-ground ploughed land) form of tillage as a strategy of adapting to erratic rainfall among crop farmers. It was found that most farmers were no longer planting crops on mounds and ridges (known locally as gbaala) as in the past. Rather, farmers mostly adopted the level-ground ploughing (locally called pari-jabing) using tractors, bullock ploughs and hand-hoes for planting (see Figure ). This form of tillage allows for easy moisturising of soil with little rains. The gbaala form of tillage was said to be common in the past when rainfall pattern was thought to be good for farmers. The earth priest (Jantina) in Nabugubelle revealed that;

We used to make mounds for planting during the days that the rains were more and abundant. Crops could do (yield) better when they were planted on mounds. In present years, the rains are not adequate and do not come frequently too. So, we have abandoned ‘gbaala’ for ‘pari-jabing’ which allow for easy rainwater penetration and moisture retention for crops. With the current rainfall pattern in our area, if you plant crops on mounds, you won’t get better yields. Mounds require heavy and continuous rains to get moisturised for plant germination and growth. (in-depth interview)

Although one could attribute the abandonment of ridging form of tillage to the use of modern farm implements such as tractors and bullocks for ploughing, farmers’ account suggests otherwise, rainfall variability was a key reason.

Moreover, the results show that multiple cropping was a common traditional adaptation strategy as farmers were observed to have cultivated maize, groundnuts, bambara beans, cassava, yam, potatoes, rice, soya beans, white beans on their farms. Results from FGDs revealed that most farmers cultivated at least two or more crops to avert total crop failure since different crops adapt differently to climate extreme events such as floods and droughts. In responding to a question on why most farmers cultivate many crops within the season, a female discussant in Nabugubelle queried that;

… what if the rains fail? We cultivate different crops because they [crops] respond differently to the variations in rainfall, … at least all the crops will not fail you when the rains are poor or excessive during the season. (FGD)

Another discussant affirmed with a local proverb; chua bi yorbor, nuung jang yor (“if dawadawa is not bought, shea butter will be bought”). This implies that if one crop fails, the other(s) will not fail. It was observed that cereal, leguminous, roots and tuber crops were cultivated in multiple manner among farming households. Different crops have different maturity periods. Crops such as beans, groundnuts and some varieties of maize were early maturing while others such as yam, potatoes, cassava, rice, white beans, traditional maize varieties, and bambara beans were long maturing crops. These crops have different water and soil nutrient requirements for growth and yields.

Mass adoption of maize farming among smallholder households was attributed to the fact that there were various early maturing varieties of maize available to farmers. A male household head in Challu community noted that:

Maize has several early maturing varieties that are available and accessible to many of us [farmers] through bachawiFootnote1 company unlike the other cereals. I can also easily get the seeds to buy on the market. The rainfall pattern, these days, does not support the cultivation of long maturing crops like millet, sorghum, guinea corn, and rice. The farming season has become shorter and makes it difficult to cultivate these crops which have long maturity periods. There is a recurrent pattern of late onset and early stop of the rains in recent years. (In-depth interview)

During a discussion, a farmer in Nmanduanu corroborated that;

Maize cultivation has become prominent because of the poor rainfall pattern. We [farmers] have now adopted some new varieties of maize which mature within short period and give maximum yields under chemical fertilization. We do not get improved varieties of the other crops like millet, rice, sorghum; these crops are still long maturing and are usually affected by the early cessation of the rains. So, why won’t farmers abandon them for maize?. (FGD)

It was observed that there were several new varieties of maize available to farmers through different out-grower companies. Some of these hybrid seeds included Panaar 12, Panaar 52, Pioneer, Lake, and SeedCo which were supplied to farmers. The Savannah Agricultural Research Institute (SARI) was credited for developing a drought-friendly maize variety for farmers in northern Ghana. The Government of Ghana’s Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ), and Planting for Food and Export (PFE) programmes also supplied to farmers a variety known as “SC719” and locally called Gemedi. The drive to diversify by adopting new maize varieties was also spurred by commercial organisations such as Wienco and Bachawi that employed contract farming techniques to reach a lot of farmers. According to participants, this initiative was helpful as they had opportunity to access new maize varieties to enhance food production. This also motivated many women into active cultivation of maize farming. During interviews, it was suggested that women were actively involved in crop farming in recent years than in the past. This was to supplement the efforts of male counterparts in household food production and supply. It is believed that food crop production has been severely compromised at the household level by the vicissitudes of climate change and variability which have overwhelmed men roles as sole providers of household food. Hence, women efforts are needed to supplement household food supply efforts. The findings revealed that women in the past were not active and full-time food crop farmers; they only got engaged in sowing, harvesting and transportation of farm produce from farms to homes. In Nabugubelle, a farmer revealed that;

Women were known for the cultivation of only vegetables such as okro, pepper, garden eggs, tomatoes, and other vegetables on the farm. Food crop farming was purely considered a masculine activity. You could not marry a woman and bring her to be a farmer in your home. Her parents will never accept that. You will lose her to another man. But today, what do we see? Women now farm and even compete with men. It is just because the rainfall pattern does not favour us (farmers) at all. We [farmers] cannot predict rainfall pattern for any farming season. So, production efforts by men alone are not enough to sufficiently feed families and provide other needs. The women are now augmenting our [men] efforts to feed and provide family needs through crop farming. (in-depth interview)

This means that women, in the past, were not involved in the cultivation of cereals and other staple food crops. Their involvement in active cereal cultivation is due to declining crop production because of climate change and variability.

The results revealed that farmers supplemented crop farming with rearing of poultry (fowls, guinea fowls, ducks, and turkeys), ruminants (cattle, goats, and sheep) as well as non-ruminants (pigs and donkeys). These were sold for income to purchase food and/or bartered for food stuff. The magazia (women leader) in Nmanduanu corroborated that;

My son sold two of his cows to purchase 10 bags of maize for the family when we had little from our farm. Could you imagine the situation we (family) would have found ourselves if he had not got livestock?. (in-depth interview)

In addition, the animals were reared to provide source of labour and means of transport. Donkeys were reared for purposes of carrying loads to and from farms and other places. A woman in Challu recounted during focus group session that donkeys have been very helpful to women. She noted that

Donkeys are very useful to us [women]. We keep donkeys for several reasons. We use them to carry loads to and from farm and markets. We can also exchange them for food stuff or other livestock such as goats, sheep, and cattle. As result, every woman wants to have a donkey. They are our helpers. (FGD)

4.2. Non-farm adaptation strategies

During FGDs, it emerged that gathering of forest products such as shea (Vitellaria paradoxa) nuts, dawadawa (Parkia biglobosa), baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) leaves and fruits and other fruits and leaves which are eaten, were harvested, and sold in their raw or processed forms for household income. Income from the sales of these forest products is used to provide for other needs such as health, education, and purchase of extra food items to supplement household food supply and consumption. These forest products could also be consumed at the household level as well as bartered for food stuff and other household needs. Gathering of forest products was reported as a common activity among women than men.

Moreover, charcoal production and sale were reported as alternative livelihood venture for households, especially for households whose harvest were poor due to climatic extremes. It was observed that charcoal was sold within and without the municipality in large quantities. Vehicles were often seen loaded with charcoal moving to Kumasi, Accra, and other cities for sale (see Figure ). It was revealed that sales from charcoal provided alternative source of income for meeting the needs of household members. A female household head in Challu revealed during an in-depth interview that;

I produce and sell charcoal to buy school uniforms, sandals, and books for my children. I also use the money to make and renew health insurance cards for my children and myself. I sometimes use the money to buy food items to supplement household food supply when I get little from my farm. (In-depth interview)

Charcoal production is a serious threat to environmental sustainability as it contributes significantly to deforestation and degradation. This is because it involves the felling of trees including trees of economic value such as shea (Vitellaria paradoxa), dawadawa (Parkia biglobosa), and other species.

Logging was also a supplementary livelihood activity in the area. The youth and landlords were engaged in logging of rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo), locally called butuma, and other species which were sold to Chinese merchants and local wood dealers. Ownership and the use of chainsaw machines for logging was a common thing in the study communities. These were sources of income to owners and the operators of these chainsaw machines who rented them for use during the off-farm season. Rosewood harvesting was a lucrative activity to landowners and loggers as Chinese merchants provided ready markets for harvested wood. Logged rosewood were loaded in containers (see Figure ) and sold to Chinese merchants who were their major sponsors for the logging. These containers were usually conveyed to Accra for export to China. A container of rosewood was sold at an average amount of between GHC 12,000.00 to GHC 25,000.00 based on the sizes of the logs. For instance, a container with a maximum of 100 logs was sold at GHC 12,000.00 whereas a container with a maximum load of 40 logs was sold at GHC 25,000.00. Consequently, many farmers were engaged in it as a supplementary source of income for their household needs. Sales from rosewood logging enabled some farmers to access farm inputs and services of farm implements.

It was revealed that most young men migrate to mining areas to engage in illegal mining (known locally as galamsey) where they make money and remit their families at home. Others will also go during the off-farm season but return during the farming season after having made some money to acquire farm inputs and services. Young women also migrate to urban centres where they engage in head portage known locally as kayaye for income. During a group discussion, a woman in Nmanduanu noted that;

Our harvests are not enough, and we cannot sell some for income to cater for other household needs. That is why we usually go to Kumasi, Accra, and other cities to engage in kayaye to earn income to cater for other needs like paying our children school fees and health needs. We also return home during the farming season and can pay for tractor services and farm inputs. (FGD)

Similarly, a youth leader in Challu community noted that;

During the off-farm season, many young men travel to the mining centres to engage in galamsey, to earn extra money to cater for other needs. When they earn money from galamsey, they return home and use the money for their farming activities. They can pay for tractor services and buy inputs”. (In-depth interview)

Migration has become a major means of coping with the fluctuations of rainfall which culminate in poor crop yields and harvest for many households. It was identified as an important means where farmers get themselves engaged in other livelihood activities elsewhere to earn income for farming and to cater for their household needs.

It was also found that village savings and loans associations (VSLAs) (locally called susu) were common among women. These were seen as means to empowering women and creating access to small credit through group weekly contributions. The VSLAs were mostly initiatives by NGOs working on alternative livelihoods and climate change programmes in the communities. Women were put into groups and trained on how to save money in metallic boxes. Three different keys were given to the executives of the groups. This made it difficult for one person to unlock the box without the others. Contributions were done on weekly basis and monies were given out to members as local loans to start petty businesses including farming. Therefore, the VSLAs served as credit facilities to members of the groups in the communities. This was helpful to a lot of the women to cope with impacts of climate change on farming.

5. Discussion

The adaptation strategies were mostly on-farm and non-farm strategies employed by smallholder farmers (Aniah et al., Citation2019; Kupika et al., Citation2019). Thus, smallholder farmers diversified their adaptation strategies to include both on-farm and non-farm portfolios as a mechanism to sustain their livelihoods and food supply for their households (Azumah et al., Citation2022). The on-farm adaptation strategies included crop and farm diversification, cultivation of early maturing and drought-tolerant crops, changes in forms of tillage, and women active engagement in crop farming. The non-farm strategies employed by smallholder households were charcoal production and sale, logging, gathering of forest products and seasonal migration of youth to find menial jobs.

Having two or more farms either within the same geographical area or different geographical areas with different land characteristics by smallholder farmers was strategic for climate change adaptation. These farmlands had the characteristics of upland, lowlands, flatlands, and others were closer to streams. Farmers concurrently owned new farm fields (bakah fali) in addition to the old or existing farms (bakah bini) to reduce the risk of total crop failure. This is particularly important considering the intra-seasonal variability and sub-spatial rainfall variability in northern Ghana. The produce from these farms supplements each other to enhance the household food needs of smallholder farmers. This is because any of these farms was lowland farms (fuo pele bakah), or upland farms (gandolo bakah) or having features of both lowland and upland. Therefore, this reduces the impacts of rainfall variability on farm crops. These agree with Derbile (Citation2010) that multiple farm characteristics are important in adapting to rainfall variability in northern Ghana. There was also a shift from making and planting on mounds and ridges (gbaala) to planting on flat tilled and/or level-ground ploughed fields (pari-jabing). The level-ground or flat-tilled land has replaced the mound and ridge form of tillage because of the ability of flat-ploughed lands to get wet or moisturised for planting and plant use with low rainfalls. Mounds and ridges were only common among yam, potato and vegetable farmers. Thus, this shift from the gbaala to the parijabing form of tillage is motivated by the changes and variability in rainfall pattern which manifests in low precipitation and consequently low soil moisture which affects crop growth and yields. Contrary to our findings, Derbile et al. (Citation2019) found that farmers in the Wa Municipality were rather adopted ridging and making mounds to plant crops as a way of adapting to poor rainfall pattern. These differences in practice may be attributed to the fact that smallholder farmers in these areas cultivate different crops and the land characteristics in these areas are not also the same.

Furthermore, the findings showed that smallholder farmers cultivated different types of food crops than relying on one staple crop. This corroborates with Dittoh and Akuriba’s (Citation2018) view that farmers in SSA are much concerned and motivated by cultivating different crops on their farmlands than a single farm crop. The findings revealed that farmers cultivated a mixed of cereals, legumes, roots, and tuber crops which have varied of levels of requirements of soil fertility, soil moisture, and different level of resistance to pests and diseases. This strategic combination of crops by farmers reduces the risk of food crop failure since they have different levels of soil nutrient and water requirements and pests and disease resistance. There is also a mixture of varieties including indigenous varieties, which helps to build local resilience and reduce agricultural vulnerability to rainfall and temperature variability. These crops have different duration of maturity in addition to the differences in the water retention and soil fertility levels to ensure minimum yields for households. This helps to reduce the risk of total crop and livelihood failures among farmers during years of extreme climatic conditions as suggested by Dumenu and Obeng (Citation2016). Other studies found that this strategy helps them to meet the varied food demands of households and maximises their incomes (Liu et al., Citation2022; Tene, Citation2022).

The findings also showed that maize cultivation was very common among farming households due to availability of various improved varieties which were relatively accessible to farmers through private farming companies. These varieties were maturing within a period of two to three months with better yields under the prevailing rainfall pattern. These findings were similar to the findings of Azumah et al. (Citation2021) who indicated that smallholder maize farmers have access to various maize seeds which enhance maize productivity in Ghana. The findings were also consistent with Dittoh and Akuriba’s (Citation2018) observation that maize is one of the few crops that SSA farmers, including Ghana, tend to emphasis its cultivation to the disadvantage of other crops. This, the authors noted, could be risky for future food and nutrition security in SSA.

Moreover, the findings suggested that women active engagement in crop farming was to complement efforts at sustaining household food security because of declining crop productivity due to climate change. This, hitherto, was not common in the past among farming households in north-western Ghana. Food security is increasingly compromised to the extent that men efforts in food crop production seem to be inadequate to meet household food demand. Therefore, women have become more actively involved in crop farming in present times than in the past to augment household food supply and other needs which were otherwise left to men as providers of household food (Jarawura, Citation2021). Najjar et al. (Citation2022) also observed that the impacts of climate change have made agriculture become feminised with increasing involvement of women in various forms of agriculture in both developing and developed countries. Pettengell (Citation2015) corroborated that, the impacts of droughts, deforestation, and erratic rainfall have made women front-liners, forcing them to work even harder to feed their families, communities, and countries. The findings showed that women were not engaged in crop farming, but they were also engaged in gathering of forest products to supplement crop farming. Shea nuts, dawadawa fruits, baobab fruits and leaves as well as other forest products were gathered mostly by women for consumption and sale for household income. Perez et al. (Citation2015) concorded that, indigenous women in Africa get engaged in harvesting natural resources as means to adapting to impacts of climate change and variability.

The findings showed that charcoal was produced large quantities and sold in major cities for household income. This corroborates the findings of other studies where charcoal production and sale among smallholder farmers has become a supplementary livelihood activity to households in northern Ghana (Abdulai et al., Citation2021; Alhassan et al., Citation2019). In addition to charcoal production, indiscriminate logging of rosewood trees and other species including shea trees was common alternative income activity among farmers. Rosewood trees were logged and sold to Chinese merchants in containers for export. Many young men and landlords got engaged due to its high demand and market value (Dumenu & Bandoh, Citation2016). Although, charcoal production and logging were supplementary livelihood activities to households, these activities could exacerbate the threats of climate change.

It also emerged that migration of young men and women to mining and urban centres to engage in mining and kayaye (head portage) respectively has become one of the many ways of coping and adapting to low yields and poor harvests. These young people go to work in these areas during the off-farm season to earn income which is remitted home for purchase of food stuff and farm inputs for the next farming season. Other studies have indicated that for the migration of young men and women to cities in southern Ghana during the off-farm season to engage in menial jobs for income to supplement household food supply and other needs is mostly driven by climate change (Alhassan et al., Citation2019; Aniah et al., Citation2019; Gyampoh & Asante, Citation2011). In this study, migration is discussed in two perspectives namely permanent and temporary migration. The permanent migration was usually common with young men who migrated to mining towns to engage in illegal mining activities known as galamsey. As they begin making money, they turned to settle in the cities and be remitting their families back at home to supplement household food supply. The temporary migration, on the other hand, was where young people migrated to urban and mining centres during the off-farm season to engage in menial jobs for income and return homes prior to the farming season. That is, the monies they make help them to pay for the cost of ploughing, seeds, fertilizer, and other inputs and farm services.

Village savings and loans associations were common sources of micro-credits to rural farmers particularly women farmers. Farmers were usually put into smaller groups where they make weekly contributions for savings. The savings are given out to members as loans. This strategy has been very helpful to rural farmers by providing access to micro-credit facilities to enhance farming. This system of local financial support for smallholder women farmers in rural communities without any external and formal support systems is an emerging strategy championed by NGOs in a bid to building smallholder farmers’ capacities and resilience to livelihood shocks. Hence, it may not be popular in climate change adaptation literature, to the best of our knowledge. However, there have been reports of farmers resorting to formal credit facilities for financial support as a coping strategy to the impacts of climate variability (Bryan et al., Citation2013; Derbile, Citation2010).

6. Conclusions

The findings showed that farmers adopted multiple strategies to adapt to climate change mostly based on their own knowledge systems and practices. They employed both farm-based and non-farm-based adaptation strategies to sustain household food supply. The study concludes that smallholder farmers’ knowledge in adaptation planning cannot be overemphasised as they continue to develop strategies against climate change through their own internal knowledge systems and practices. Therefore, the paper advocates for mainstreaming farmers’ knowledge systems into climate change adaptation planning at local and national level development planning to enhance effective community-based adaptation planning in Ghana.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our research participants for their time and decisions to participate in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dramani Juah M-Buu File

Dramani Juah M-Buu FILE holds PhD in Environmental Management from the University of South Africa, Pretoria. He is a Lecturer at the Department of Local Governance and City Management in the Faculty of Public Policy and Governance, SD Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies (SDD UBIDS), Wa-Ghana. He is an early career researcher in climate change, disaster management, sustainable development, and indigenous knowledge systems.

Francis Xavier Jarawura

Francis Xavier Jarawura is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Planning in the Faculty of Planning and Land management, SDD UBIDS, Wa-Ghana. He holds PhD and research in climate change and migration.

Emmanuel Kanchebe Derbile

Emmanuel Kanchebe Derbile is a Professor of Development Planning at the Department of Planning in the Faculty of Planning and Land management, SDD UBIDS, Ghana. He is a researcher in climate change, development planning, indigenous knowledge, sustainable development. He holds PhD in Development Studies from the University of Bonn, Germany. The paper aligns with the research interests (climate change) of the authors. Adaptation has become necessary for securing rural livelihoods, particularly smallholder food crop production due to increasing impacts of climate change.

Notes

1. Bachawi is a name of a company which locally means “let them look for an alternative”.

References

- Abdulai, I. A. (2022). The effects of urbanisation pressures on smallholder staple food crop production at the fringes of African cities: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2144872

- Abdulai, I. A., Derbile, E. K., & Fuseini, M. N. (2021). Livelihood diversification among indigenous peri-urban women in the Wa municipality, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 18(1), 72–19. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v18i1.4

- Aksoy, Z., & Öz, Ö. (2020). Protection of traditional agricultural knowledge and rethinking agricultural research from farmers’ perspective: A case from Turkey. Journal of Rural Studies, 80, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.09.017

- Alam, G. M. M., Alam, K., & Mushtaq, S. (2017). Climate change perceptions and local adaptation strategies of hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Climate Risk Management, 17, 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2017.06.006

- Alhassan, S. I., Kuwornu, J. K. M., & Osei-Asare, Y. B. (2019). Gender dimension of vulnerability to climate change and variability: Empirical evidence of smallholder farming households in Ghana. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 11(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-10-2016-0156

- Alhassan, S. I., Shaibu, M., Kuwornu, J. K., & Damba, O. (2018). Factors influencing farmers’ awareness and choice of indigenous practices in adapting to climate change and variability in Northern Ghana. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 26, 1–13.

- Aniah, P., Kaunza-Nu-Dem, M. K., & Ayembilla, J. A. (2019). Smallholder farmers’ livelihood adaptation to climate variability and ecological changes in the savanna agro ecological zone of Ghana. Heliyon, 5(4), e01492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01492

- Ansah, G. O., & Siaw, L. P. (2017). Indigenous knowledge: Sources, potency and practices to climate adaptation in the small-scale farming sector. Journal of Earth Science & Climatic Change, 8(12), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7617.1000431

- Aswani, S., Lemahieu, A., Sauer, W. H. H., & Viña, A. (2018). Global trends of local ecological knowledge and future implications. PLoS ONE, 13(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195440

- Atanga, R. A., Inkoom, D. K. B., & Derbile, E. K. (2017). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development planning in Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 14(2), 209. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v14i2.11

- Ayanlade, A., Radeny, M., & Morton, J. F. (2017). Comparing smallholder farmers’ perception of climate change with meteorological data: A case study from southwestern Nigeria. Weather and Climate Extremes, 15, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2016.12.001

- Azumah, S. B., Network, S., Africa, W., & Mahama, A. (2022). Climate perception, migration and productivity of maize farmers in Ghana. Journal of Agricultural Studies, 10(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.5296/jas.v10i1.19494

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices (2nd ed.). Textbooks Collection. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks/3

- Bryan, E., Ringler, C., Okoba, B., Roncoli, C., Silvestri, S., & Herrero, M. (2013). Adapting agriculture to climate change in Kenya: Household strategies and determinants. Journal of Environmental Management, 114, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.10.036

- Claxton, M. (2010). Indigenous knowledge and sustainable development third distinguished lecture, the cropper foundation UWI. St Augustine.

- Derbile, E. K. (2010). Local Knowledge and Livelihood Sustainability under Environmental Change in Northern Ghana. [ PhD thesis]. University of Bonn,

- Derbile, E. K., Bonye, S. Z., & Yiridomoh, G. Y. (2022). Mapping vulnerability of smallholder agriculture in Africa: Vulnerability assessment of food crop farming and climate change adaptation in Ghana. Environmental Challenges, 8, 100537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2022.100537

- Derbile, E. K., Chirawurah, D., & Naab, F. X. (2022). Vulnerability of smallholder agriculture to environmental change in North-Western Ghana and implications for development planning. Climate and Development, 14(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1881423

- Derbile, E. K., Dongzagla, A., & Dakyaga, F. (2019). Livelihood sustainability under environmental change: Exploring the dynamics of local knowledge in crop farming and implications for development planning in Ghana. Journal of Planning and Land Management, 1(1), 154–180. https://doi.org/10.36005/jplm.v1i1.11

- Derbile, E. K., File, D. J. M., & Dongzagla, A. (2016). The double tragedy of agriculture vulnerability to climate variability in Africa: How vulnerable is smallholder agriculture to rainfall variability in Ghana? Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 8(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/JAMBA.V8I3.249

- Dittoh, S., & Akuriba, M. (2018). Africa’s looming food and nutrition insecurity crisis a call for action. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Economics and Extension, 1(1), 148–170. .

- Dube, E., & Munsaka, E. (2018). The contribution of indigenous knowledge to disaster risk reduction activities in Zimbabwe: A big call to practitioners. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 10(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v10i1.493

- Dumenu, W. K., & Bandoh, W. N. (2016). Exploitation of African rosewood (Pterocarpus erinaceus) in Ghana: A situation analysis. Ghana Journal Forestry, 32(2016), 1–15.

- Dumenu, W. K., & Obeng, E. A. (2016). Climate change and rural communities in Ghana: Social vulnerability, impacts, adaptations and policy implications. Environmental Science and Policy, 55, 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.10.010

- Elum, Z. A., Modise, D. M., & Marr, A. (2017). Farmer’s perception of climate change and responsive strategies in three selected provinces of South Africa. Climate Risk Management, 16, 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2016.11.001

- File, D. J. M., & Derbile, E. K. (2020). Sunshine, temperature and wind: Community risk assessment of climate change, indigenous knowledge and climate change adaptation planning in Ghana. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 12(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-04-2019-0023

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 population and housing census: Sissala East District analytical report. Author.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census general report: Population of regions and districts, 3A. Author

- Guodaar, L., Bardsley, D. K., & Suh, J. (2021). Integrating local perceptions with scientific evidence to understand climate change variability in northern Ghana: A mixed-methods approach. Applied Geography, 130, 102440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2021.102440

- Gyampoh, B. A., & Asante, W. A. (2011). Mapping and documenting indigenous knowledge in climate change adaptation in Ghana. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4818.6640

- Haque, M. M., Bremer, S., Aziz, S. B., & van der Sluijs, J. P. (2017). A critical assessment of knowledge quality for climate adaptation in Sylhet Division, Bangladesh. Climate Risk Management, 16, 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2016.12.002

- Iloka, N. G. (2016). Indigenous knowledge for disaster risk reduction: An African perspective. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 8(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/JAMBA.V8I1.272

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2014). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Regional aspects. Cambridge University Press.

- Jarawura, F. X. (2021). Dynamics of drought-related migration among five villages in the savannah of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography, 13(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjg.v13i1.6

- Kumar, K. A. (2010). Local knowledge and agricultural sustainability: A case study of Pradhan tribe in Adilabad district. (Working Paper No. 81), Centre for Economic and Social Studies.

- Kupika, O. L., Gandiwa, E., Nhamo, G., & Kativu, S. (2019). Local ecological knowledge on climate change and ecosystem-based adaptation strategies promote resilience in the Middle Zambezi Biosphere Reserve, Zimbabwe. Scientifica, 2019, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3069254

- Liu, M., Zheng, W., & Zhong, T. (2022). Impact of migrant and returning farmer professionalization on food production diversity. Journal of Rural Studies, 94, 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.05.020

- Mafongoya, P. L., & Ajayi, O. C. (2017). Indigenous knowledge systems and climate change management in Africa. CTA, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 316.

- Morton, L. W., McGuire, J. M., & Cast, A. D. (2017). A good farmer pays attention to the weather. Climate Risk Management, 15, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2016.09.002

- Muyambo, F., Bahta, Y. T., & Jordaan, A. J. (2017). The role of indigenous knowledge in drought risk reduction: A case of communal farmers in South Africa. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 9(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v9i1.420

- Mwinkom, F. X. K., Damnyag, L., Abugre, S., & Alhassan, S. I. (2021). Factors influencing climate change adaptation strategies in North‑Western Ghana: evidence of farmers in the Black Volta Basin in Upper West Region. SN Applied Sciences, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04503-w

- Najjar, D., Devkota, R., & Feldman, S. (2022). Feminization, rural transformation, and wheat systems in post-soviet Uzbekistan. Journal of Rural Studies, 92, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.03.025

- Negeri, B., & Demissie, G. (2017). Livelihood Diversification: Strategies, Determinants and Challenges for Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Communities of Bale Zone, Ethiopia. American Journal of Environmental and Geoscience, 1(1), 19–28. www.scinzer.com

- Nkegbe, P. K. (2018). Soil and Water Conservation Practices and Smallholder Farmer Multi-Activity Technical Efficiency in Northern Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 15(1), 55–91. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v15i1.4

- Nkomwa, E. C., Joshua, M. K., Ngongondo, C., Monjerezi, M., & Chipungu, F. (2014). Assessing indigenous knowledge systems and climate change adaptation strategies in agriculture: A case study of Chagaka Village, Chikhwawa, Southern Malawi. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 67-69, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2013.10.002

- Nyadzi, E., Ajayi, O. C., & Ludwig, F. (2021). Indigenous knowledge and climate change adaptation in Africa: a systematic review. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition & Natural Resources, 2021(29), https://doi.org/10.1079/pavsnnr202116029

- Nyong, A., Adesina, F., & Osman Elasha, B. (2007). The value of indigenous knowledge in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the African Sahel. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 12(5), 787–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9099-0

- Ogunyiola, A., Gardezi, M., & Vij, S. (2022). Smallholder farmers’ engagement with climate smart agriculture in Africa: role of local knowledge and upscaling. Climate Policy, 22(4), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.2023451

- Perez, C., Jones, E. M., Kristjanson, P., Cramer, L., Thornton, P. K., Förch, W., & Barahona, C. C. (2015). How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Global Environmental Change, 34, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.003

- Pettengell, C. (2015). Africa’s smallholders adapting to climate change: The need for national governments and international climate finance to support women producers. Oxfam International.

- Sahu, N. C., & Mishra, D. (2013). Analysis of Perception and Adaptability Strategies of the Farmers to Climate Change in Odisha, India. APCBEE procedia, 5, 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcbee.2013.05.022

- Tabbo, A. M., & Amadou, Z. (2017). Assessing newly introduced climate change adaptation strategy packages among rural households: Evidence from Kaou local government area, Tahoua State, Niger Republic. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v9i1.383

- Taye, A., & Megento, T. L. (2017). The role of indigenous knowledge and practice in water and soil conservation management in Albuko Woreda, Ethiopia. Bonorowo Wetlands, 7(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.13057/bonorowo/w070206

- Tene, N. S. T. (2022). Cameroon’s adaptation to climate change and sorghum productivity. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2140510

- Tesfahunegn, G. B., Ayuk, E. T., & Adiku, S. G. K. (2021). Farmers’ perception on soil erosion in Ghana: Implication for developing sustainable soil management strategy. PLoS One, 16(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242444

- Torres-Bagur, M., Ribas Palom, A., & Vila-Subirós, J. (2019). Perceptions of climate change and water availability in the Mediterranean tourist sector: A case study of the Muga River basin (Girona, Spain). International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 11(4), 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-10-2018-0070

- Tripathi, A., & Mishra, A. K. (2017). Knowledge and passive adaptation to climate change: An example from Indian farmers. Climate Risk Management, 16, 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2016.11.002

- Yiridomoh, G. Y., Bonye, S. Z., Derbile, E. K., & Owusu, V. (2021). Women farmers’ perceived indices of occurrence and severity of observed climate extremes in rural Savannah, Ghana. Environment Development and Sustainability, 24(1), 810–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01471-4

- Zoundji, G., Witteveen, L., Vodouhê, S., & Lie, R. (2017). When baobab flowers and rainmakers define the season: Farmers’ perceptions and adaptation strategies to climate change in West Africa. International Journal of Plant Animal and Environmental Sciences, 7(2), https://doi.org/10.21276/Ijpaes

Appendix A:

In-depth Interviews Guide

We are researchers/staff from Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa. We are undertaking this research on how smallholders understand climate change using their own knowledge systems and how climate change is affecting food crop farming as well as how smallholder farmers are adapting to climate. The information provided here will be used for only academic purposes and shall be treated as confidential. Anonymity of respondents is also assured. Your identity will not be disclosed in any data published in the journals and any related platforms. There are no risks associated with this research and your participation is highly voluntary. You are free to withdraw from this interview at any point or time. I will appreciate it if you spend approximately 35 minutes of your time in this interview. I will also seek your kind permission to audio record our conversation and take photos. For more information, you may contact the lead researcher; Dramani Juah M-Buu File (0207784736).

Do you agree to participate in the research? Yes … … … No … … … .

In-depth interview guide

Demographic characteristics

Community … … … … … … … … Age … … … … … . Sex … … … .

Title … … … … … … … . Occupation … … … … … .

Education … … … … … … . Marital status … … … … … … .

Number of children/dependants … … … … … … .

For:

Household Heads

Local perceptions and understanding on climate change and variability

How has rainfall changed over the years?

How has temperature changed over the years?

How has sunshine changed over the years?

What do you think are the causes of these changes?

What sources of knowledge do you rely on for information in changes in climatic elements? Probe for information on the use of both local knowledge and scientific knowledge systems

Climate change and effects on agriculture

How often and how does drought affect food crop farming in your community? Which crops are affected the most?

How often and how does too much rainfall affect crop farming in your community? Which crops are affected the most?

How often and how do floods affect food crop farming in the community? Which crops are affected the most.

How often and how do high temperatures affect crop farming in your community? Which crops are affected the most?

Which crops have you stopped farming because droughts affect yields?

Which crops have you stopped farming because of too much rain?

Which crops have you stopped farming because of floods?

In general, how has climate change affected food supply for household consumption these days?

Adaptation strategies

Which crops do you cultivate to adapt to drought? (Crop varieties, local names, indigenous or new crop varieties).

Which crops do you cultivate to adapt to too much rainfall or floods? (Crop varieties, local names, whether indigenous or new crop varieties and inputs required).

Which crops do you cultivate to adapt to high temperatures or extreme sunshine? (Crop varieties, local names, whether indigenous or new crop varieties and inputs required).

What specific farming practices do you adopt to adapt to climate change?

In general, what non-farm activities and income sources do you and your families engage in to meet household food needs due to climate change? How effective are these strategies in providing household needs?

Thank you for your time

For: Opinion leaders

Are there changes in the pattern of rainfall, temperature, sunshine, and wind in this community over the years? How have they changed?

How do these changes affect food crop farming and food supply in this community?

How are households and farmers adapting to the impacts of climate change? Probe on the strategies (both farm-based and non-farm based) adopted by farmers and households.

How are these strategies developed? Probe for source for information and knowledge in developing these strategies.

How does your own local knowledge systems help in developing adaptation strategies?

What are some of the adaptation strategies that are common among men and women in this community?

Do you think farmers have changed and/or adopted crops and farming practices due to climate change in this community? What are some of these practices and methods that have been changed and adopted?

Thank you for your time.

Appendix B:

Focus Group Discussion guide.

What can you say about the pattern of rainfall and temperature over years as smallholder farmers? Are there changes and how have they changed?

How are these changes affecting your farming and household food supply?

What strategies do you adopt as measures to sustain household food supply?

What is role of your local knowledge systems in developing and implementing these strategies?

What crops do you cultivate under current climatic conditions to secure household food supply? And where and how do you acquire the seeds for planting? Why do you (farmers) cultivate many different crops?

In general, what non-farm activities and income sources do you and your families engage in to meet household food needs due to climate change? How effective are these strategies in providing household needs?

Thank you for your time.