Abstract

With the increasing level of global urbanization, cities have become protagonists, acquired multiple roles, and influence urban spaces’ transformation and strategic governance arrangements. A contemporary perspective of urban-territorial protagonism extends the debate to the image of destinations and the territorial brand focused on regional development. The objective is to understand the influence of destination image in the productive process of territorial branding in regional development. Multiple cases were analyzed using this method. The qualitative research employs a methodological-analytical matrix as a research protocol based on four macro variables. According to the results, a significant relationship exists between destination image and territorial brand, both dependent and independent. Research contributions include an examination of the inter-relationship between destination image and the concept of the territorial brand in regional development. As well, the research proposes a methodological protocol supported by the territorial brand as a framework for analyzing the destination image, introducing a novel approach in the field. The conclusion reiterates that destination image can influence the productive process of the territorial brand in regional development and vice-versa. However, each case will lead to distinct types of development.

1. Introduction

The tourism approach, especially the destination image, is integrated with cultural studies from a regional development perspective through territorial brands. Thus, tourism can be seen, in addition to the economic factor, as a social and cultural phenomenon. Destinations and their representations are dynamic historical units crossed by speeches (Saarinen, Citation2004). This debate extends to the image of destinations (P. Almeida, Citation2011) and the territorial brand focused on Regional Development (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018) that can become a new variable (dependent or independent) for the destination image from a contemporary perspective. An examination of the concept of the territorial brand in regional development as a sociocultural intervention project (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018) for lived territories (Raffestin, Citation1993) and their narratives (Pastak & Kährik, Citation2021). Consequently, the destination image and the territorial brand have new relationships, which is significant for tourism and other sectors.

Research problems include expectations and perceptions resulting from the image, one of the most important considerations in choosing a destination (P. Almeida, Citation2011, Ogunyankin, Citation2019; Buhalis, Citation2000). Cultural factors should be understood and managed to manage perceptions that affect destinations’ image (Currie, Citation2021). It is necessary to understand and manage them. Regarding territorial branding, it is necessary to understand the plurality of social actors present in the territory, the type of development generated (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018), and the reformulation of geographical imaginaries (Sotoudehnia & Redwood, Citation2019). It also encompasses the existence of a global map of places (Anholt, Citation2010) in which the image of destinations (P. Almeida, Citation2011) is present through the territorial brands arranged in urban rankings (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2019).

Thus, the objective of the research is to analyse the influence of the destination image in the productive process of the territorial brand in Regional Development. It is also intended to contribute with the deepening of the theoretical referential about destination image and territorial brand. Two constructs, territorial brand, and destination image are critically investigated. Their analysis is, however, based on theories of regional development (Furtado, Citation2009; Stöhr, Citation1981).

As part of the study, one construct was compared to another to understand how these components interact. Notably, the research focuses on more than analyzing the impact of this process but instead on understanding the influence exerted. The goal is to investigate how one construct affects and shapes the other, exploring the mechanisms and effects of this relationship. By examining this mutual influence, a deeper understanding of the underlying processes and implications resulting from the interaction between the constructs under study is sought.

Research justifications highlight the multiplicity of perspectives of destination image as the sum of beliefs, ideas, and impressions (Kotler et al., Citation2002) built around a destination, distinguishing it from another (Holloway, Citation1994). Furthermore, sociodemographic characteristics can influence the construction of a destination’s image (Pan et al., Citation2021) and the presence of big data in this image (Lalicics et al., Citation2021). When a destination has a negative image, the brand can improve it (Currie, Citation2021), depending on the strategies adopted and the type of development that the social actors who created the territorial brand aim for in the production and use of that territory (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018).

The study’s originality encompasses the research’s internationalization by investigating the image of urban destinations and understanding its relationship with the concept of the territorial brand in the context of regional development. Therefore, the relevance extends to the rethinking and planning the image of destinations based on territorial brands in multiple scales.

The relationship between Destination Branding and Territorial Branding can be explored in research due to the interconnection between these concepts. Both share the goal of creating a positive perception of a place. However, while Destination Branding focuses on promoting specific destinations, the Territorial Brand encompasses the identity of a territory. Research can investigate how the development of a Destination Brand influences the construction of the Territorial Brand and vice versa, examining how the distinctive characteristics of a destination are incorporated into both brands. A deeper understanding of brand-building processes, and their influence on the success of a destination, can provide insights to public and private sector managers in developing tourism destinations.

2. Backgrounds

2.1. Destination image

The image is one of the variables contained in the promotion and marketing of a product; being well-built can be a differentiation and reference factor. That image is a way the consumer perceives the company, its vision of the organization, and the products or services made available (Grönroos, Citation1994). In general, image is defined as an individual’s mental representation of a given product, service, or institution. For Stylidis (Citation2020), interactions with tourists also contribute to forming the destination image.

Burgess and Bramwell (Citation2002) emphasize that destination image is a critical factor in attracting visitors and that tourists’ perception of the producing region can influence their decision to visit. Jansson et al. (Citation2014), in turn, argue three issues

That the destination image should be authentic,

It should reflect the local cultural identity to generate more interest from tourists, and

It should contribute to community development.

In this same path, Vanolo (Citation2012) points out that destination image is a social construction influenced by several factors, such as history, culture, politics, and local economy.

The image of a tourist destination can be defined as the sum of beliefs, ideas, and impressions a person has about a destination (Crompton, Citation1979). P. Almeida (Citation2011) states that the image of a tourist destination is the mental positioning that an individual makes of the perception and/or interaction with the set of tourist attributes and components of a place. The image constitutes the main component of the promotion of a destination (Fakeye & Crompton, Citation1991), being a differentiating element for tourist destinations and, at the same time, influential for tourists to differentiate themselves according to the destinations they have chosen.

The destinations that manage to put a positive and solid image in the minds of potential tourists accumulate a greater probability of being elected and thus occupied (Telisman-Kosuta, Citation1994). For Chon (Citation1990), the objective reality of the destination is not the determining factor of its election, but the image perceived by the individual. The image seeks to build through perceptions and positive experiences of a brand, seeking to influence the decision and consumer behavior. Working the image seeking to achieve a brand can and should be part of the actions developed by destination managers and the development of products to attract more visitors. For Rafael (Citation2016), the tourist, or potential tourist, anticipates and makes predictions of the experiences (online and offline) he intends to have before traveling to a particular destination. These are based on the emotions that the destination evokes in his memory, comments from friends, reading information in the most varied media, and advertisements from the most varied sources of information. The Web has emerged as one of the most important sources of information, as it can provide various interactive information ranging from informative content, such as text and 2D e-brochures, to entertainment-oriented content, such as 3D virtual tours.

The development of digital marketing has changed the practices of organizations, both strategic and operational, and has changed destinations’ regional or global competitiveness (Cooper et al., Citation2008). The innovations caused by the web have contributed to the most various transformations in tourism with a particular effect on how tourist destinations are organized, promoted, and perceived in the virtual market. For Aranda et al. (Citation2021), tourism goes by other disruptive ways to manage and communicate products and services with a proliferation of smart information and consolidation of smart destinations. Tourism benefits a country’s branding, and a place’s image is considered a key factor for international investments (Souza & Nemer, Citation1993; Hakala et al. (Citation2013).

Recent studies have focused on different types of destination analysis. Hunter (Citation2022), for example, performed a semiotic analysis, and Luo et al. (Citation2022) conducted a discourse analysis. Qu et al. (Citation2022) applied a customized method in destinations, and Liu et al. (Citation2022) attempted to understand the environmentally responsible behavior of tourists. Cambra-Fierro et al. (Citation2022) brought up the discussion on the recovery of destinations during COVID-19. Luo et al. (Citation2022) addressed the perception of the image of a destination through a study examining the factors influencing tourists’ perceptions and attitudes toward the destination’s brand.

In summary, the destination image is people’s mental representation of a particular tourist location, composed of beliefs, ideas, and impressions. Destination image is a critical factor in attracting visitors and can influence tourists’ decision to visit the place. The authenticity of the image, its connection with the local cultural identity, and potential to contribute to community development are aspects highlighted in the literature. Destination image is socially constructed and influenced by history, culture, politics, and local economy. Managing and promoting a destination’s positive image is fundamental to attracting tourists and differentiating itself from competing destinations. Destination image is formed based on positive perceptions and experiences, both online and offline, and can be influenced by varied sources of information, such as the internet. The evolution of digital marketing has transformed organizations’ practices and destinations’ competitiveness in the global marketplace. Recent studies have applied different methods of destination analysis, such as semiotic analysis, discourse analysis, and personalized approaches to understand destination image perception and tourist behavior.

2.2. Territorial brand in regional development

The concept, created by G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018), refers to the creation of symbolic value, the articulation of actors regarding the plurality of identities presents in the territory and how they make use of that brand and make it a significant asset for the territory and, consequently, for the region. The referenced study is the only one that correlates the power relations arranged in the territory through a territorial brand. The relations that cross the brand are associated with the theories of endogenous regional development. In this way, the brand is perceived as a cultural product of regional development, presenting different power relations between social actors in the use and production of the territory. Moreover, brand, image, and place branding are discussed as a sustained basis of territorial development.

2.2.1. Brand, image, place branding and the endogenous regional development

The brand is a set of characteristics and attributes that identify and differentiate a product or service in the market, creating a unique perception in the minds of consumers (Aaker, Citation1996; Kapferer, Citation2012; Keller, Citation2008). However, brand and logo differ, with the logo being the graphic representation of the brand and not the brand itself (Aaker, Citation1996). A brand involves two distinct concepts: identity and image. Brand identity is the set of visual, verbal, and sensory elements that represent a brand. It is how the brand communicates with its audience, transmitting its values, personality, and positioning (Aaker, Citation1996; Keller, Citation2008).

On the other hand, the concept of image is related to consumers’ perception of a brand, either product or company. This perception can be influenced by several factors, such as advertising, packaging, product or service quality, and company reputation (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, Citation2000; Gartner, Citation1986; Keller, Citation1993; McCracken, Citation1989).

Place branding involves applying branding strategies (strategic brand management) in places (cities, regions, countries, or tourist destinations). The aim is to build and develop the image and reputation of these places, increasing the attraction of tourists, investments, and businesses and promoting economic development (Hankinson, Citation2004; Kavaratzis, Citation2004; Anholt, Citation2007; Ashworth & Kavaratzis, Citation2010; Warnaby & Medway, Citation2013). It is noteworthy that place branding has been discussed in the context of endogenous regional development from a multidimensional approach to build the brand of the region, considering the social, cultural, environmental, and economic dimensions (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018; Faria & Marques, Citation2017; Ferreira & Rebelo, Citation2014; Lucarelli, Citation2018; Warnaby, Citation2017).

The endogenous regional development concept is driven by local resources and potentialities, with emphasis on the active participation of social actors and the social, cultural, and human aspects of the communities involved (Boisier, Citation1999; Putnam, Citation1993; Santos, Citation2000; Sen, Citation2000; Stimson, Citation2019; Touraine, Citation2007). It seeks to strengthen a region’s capacities and competitive advantages through regional public policies and strategies that value cultural diversity, innovation, and cooperation between different local actors. Perroux (Citation1961) states that economic development does not occur homogeneously in all regions. It is necessary to encourage growth from local potentialities, and this incentive is what leads to endogenous development. In the area of regional development, three concepts differ between place, territory, and region, which leads “place branding” to differ from “territorial brand” and “regional brand.” As the focus of this study is the territory, the option was for the formal concept of the territorial brand.

The territorial brand is discussed concerning the interdisciplinary debate on (re)territorialization and resignification of urban spaces (Kavaratzis & Hatch, Citation2021), urban creative destruction (Perulli, Citation2012), patterns of cultural identity (Geertz, Citation2008), urban global imaginary (Anholt, Citation2010), experiences in the territory (Konecnik & Chernatony, Citation2013), strategies to create an image for the city (Anholt, Citation2010) and those that fix the brand in people’s minds, making tangible the identity of that brand, while representing a territory (Vela et al., Citation2014). It also involves the relations and articulations of territorial brands in the context of the cultural product of Regional Development (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018). These are renowned authors who approach the theme of place branding in which the territorial brand is involved. The originality of the territorial connection brand and regional development is attributed to G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018). Until that time, territorial brand discussions were primarily focused on economics. As a result of the discussion by G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018), place branding and territorial branding were separated, creating an unprecedented classification, a TRbrand Classification Model (G. G. F. Almeida & Cardoso, Citation2022).

It is noteworthy that the concept of the territorial brand is always associated with the idea of power relations, strategic construction of cultural narratives about the territory, symbolic disputes, and the articulation of values and beliefs of a given set of social actors that create a particular reputation about and for the territory (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018). Creating a territorial brand means being aware of the complexity of three interconnected strategic processes: productive, communicative, and creative. When addressing territorial brands, one observes, in particular, the presence of four interconnected elements that stand out: brand, territory, strategic articulation, and dual territoriality, forming a methodological-analytical matrix (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018).

A review of the scientific basis for the study led to an understanding of the scope of each construct (destination image, territorial brand, and regional development). As a means of gaining a deeper understanding of the territorial brand construct, the terms were examined in each database: “territorial brand,” “territorial branding,” “territorial brand,” “marca territoriale” and “place branding.” These terms were searched because “territorial brand” or “territorial brand” is not a standard universalized nomenclature. After the mentioned research and because there is no standard, it was decided to adhere to the term territorial brand.

The oldest construct founded was about regional development (Schmidt, Citation1926), referring to 1926, in contrast to the most recent one, published in 2018, the territorial branding in regional development (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018). Research on the destination image began in the late 1980s (Phelps, Citation1986). According to the Scopus database (Kumar & Panda, Citation2001), studies on place branding have been published since 2001. This study aimed to provide, at the time, an overview, systematic, and exhaustive of the literature on “place branding” and “place marketing,” analyzing 188 articles published from 1975 to 2018 by 370 authors in 67 academic Journals. This means that although the oldest article found (Kumar & Panda, Citation2001) in the Scopus base refers to the year 2001, place branding studies date back to 1975 (Hunt, Citation1975). It is emphasized that in the year 2018, the territorial brand was inserted in the discussions of the area of regional development (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018). However, G. G. F. Almeida’s (Citation2018) studies emphasized that territorial brands have been used since the twelfth century. When a territorial brand is extended to the scope of regional development (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018), one realizes that brands of this nature go beyond economic development and tourism promotion and may constitute, in the future, a theoretical basis of regional development. There is a time gap of 60 years between the first and second constructs, decreasing the time gap with the third construct, 15 years, and remaining the same in the fourth construct, 17 years. This scenario shows that the temporal space between the concepts of the investigated constructs has decreased over time due to society’s demand to understand social phenomena.

The studies on regional development refer to 3 studies. The first and only study found in full, “On the development of the regional survey in Soviet Russia” (Schmidt, Citation1926), deals with three significant periods of studies in the country. Schmidt’s (Citation1926) survey addresses Russia’s natural resources, the national economy’s development, and each region’s characteristic peculiarities. The study recommends that because each region has its peculiar conditions, it should be studied separately from the country. This Schmidt (Citation1926) called regional development. In the WoS base (2021) 3 studies on the theme of regional development were found: population studies of France (Perrin, Citation1956); the effects of industrial development on agriculture in the Tennessee Valley (Nicholls, Citation1956); and the regional development of the North of Paraná (Dozier, Citation1956), in Brazil, published by the Geographical Review.

Therefore, the three concepts investigated (destination image, territorial brand, and regional development) are interconnected. A territory’s narratives reinforce its brand and image as a destination. Therefore, studying these concepts together is justified because they influence territorial and regional development. Based on this information, we can identify destinations that have (or do not have) a territorial brand focused on regional development. Destination planners, managers, researchers, and students in regional development, tourism, and other fields will find this helpful information.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Method

The method adopted was the hypothetical-deductive associated with the multiple case study (Yin, Citation2015) to deepen the discussion about territorial brand and destination image. Destination images do not always have territorial brands, but every territorial brand uses an image associated with its narrative.

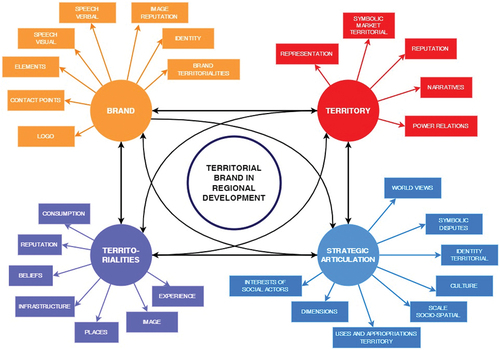

Research techniques were qualitative, using bibliographical research for the theoretical framework and multiple case studies. Furthermore, documentary research was used to collect data from the cases analyzed. Regarding the operational procedures, the research techniques were qualitative in the descriptions and analysis of the variables arranged in the MTnoDR matrix (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018) developed from the productive process of the territorial brand in regional development (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018) as a methodological protocol, anchored in four central axes or interconnected quadrants: brand, territory, strategic articulation, and territorialities (Figure ). It is the only technique, until the moment, that can analyze a territory, region, or destination as a territorial brand focused on regional development based on the MTnoDR matrix (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018). MTnoDR confirms if these spaces have a territorial brand on regional development or if they are spaces that only use advertising or marketing.

Figure 1. Matrix of the territorial brand in regional development (MTnoDR matrix).

The circuit format of the MTnoDR matrix (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018) allows the start to be in any of the axes. Due to this inter-relationship, the research can consider the circuit integrally, as well as in an isolated way, by axis, being that the methodological cutout will depend on the interest of each researcher. Thus, it is intended to analyze the image of destinations from this specific matrix in which the construct regional development is present. In this context are, power relations as a fundamental dimension of social life, which influence how people relate to each other and society’s institutions (Bourdieu, Citation1984; Foucault, Citation1990).

The strategic construction of cultural narratives about territory refers to the process of creation and dissemination of stories and symbolic representations about a given place to highlight particular identities and values (Anholt, Citation2007). Different actors can construct these narratives and involve selecting and articulating cultural, historical, geographical, and social elements to create an image of the territory. The constructed image influences how residents and visitors perceive and value the place, attracting investment, tourism, and other resources to the region (Harvey, Citation2001). The symbolic disputes, arising from the strategic constructions, involve the dispute for representations and cultural meanings, disputed and negotiated in different social and political contexts. These symbolic disputes may occur in various spheres of social life, such as politics, culture, economy, and power relations (Bourdieu, Citation1977; Hall, Citation1980; Thompson, Citation1990). All these concepts discussed territorial branding in the scope of regional development from G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018).

3.2. Research phases

There were six research phases, focusing on the stages of the investigated case study (Yin, Citation2015): data preparation and conceptual-theoretical framework, case planning, pilot test for adjustments, data collection and recording, data analysis, and, finally, research report and documentation.

3.3. Data collection

The data collected refer to the cities of Porto, in Portugal, and Pelotas, in Brazil, chosen for having territorial brands. Thus, the data collection process followed the following criteria:

3.3.1. City selection

The cities of Porto, in Portugal, and Pelotas, in Brazil, were chosen as study sites due to their specific contexts and strategies related to territorial brands, considering the influence of the destination’s image in the productive process of the territorial brand. The city of Porto is an international reference in place branding, with other territorial brands following its example. On the other hand, the city of Pelotas created a Municipal Decree to keep itself active during the change of government. Thus, specific contexts and strategies for the activation and survival of territorial brands are also analyzed, although the focus is on understanding the influence of one construct over the other.

3.3.2. Sources of evidence

The sources of the data referred to the different sources of evidence chained together and arranged in the temporal frame of analysis corresponding to 2013–2016: territorial brand, press releases; official website of the city; the historical-territorial context of the cities investigated, and the productive processes of both territorial brands analyzed (Yin, Citation2015).

Territorial brand: Information related to the territorial brands of the cities of Porto and Pelotas was analyzed using a specific analysis matrix, the MTnoDR matrix. It involves multiple variables based on four macro axes (Figure ). Therefore, information published on the internet of public access was the basis of the data collected.

Press releases: Relevant press releases from the cities of Porto and Pelotas were collected, focusing on the image of the destination and its relationship with the criteria of the territorial brand analysis matrix.

Official city website: The official website of the cities of Porto and Pelotas was examined for updated and official information about the territorial brands, considering the criteria of the analysis matrix.

Historical-territorial context: An analysis of the historical-territorial context of the investigated cities was carried out, emphasizing the relationship between the destination image and the regional development driven by the territorial brand, considering the criteria of the specific matrix.

Productive processes of the territorial brands: The productive processes related to the territorial brands of the cities of Porto and Pelotas were analyzed, considering the influence of the destination’s image and the criteria of the MTnoDR matrix.

3.3.3. Period of analysis

As mentioned earlier, the analysis of the collected data covered a specific period, from 2013 to 2016.

3.4. Data analysis procedure

Data analysis was carried out from the MTnoDR matrix (G. G. F. Almeida, Citation2018), having four macro variables: brand, territory, double territoriality (social actors and brand), and strategic articulations. It is highlighted that each macro variable has between 6 to 8 micro variables (Figure ), and it is not mandatory to cover all micro variables. The obligation lies in identifying the presence and interrelationships of macro variables (axes of the matrix).

Based on G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018), the MTnoDR matrix can be used at various scales and contexts, including country, state, city, street, tourist route, region, and others. One of these scales’ four quadrants or axes must be recognized and interconnected to be considered a territorial brand. Everything is interconnected when it comes to the territorial brand in regional development. Thus, the findings of both destinations as being (or not) territorial brands in the view of G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018) are based on the collection of qualitative data and the external perceptions of these destinations. We will see these findings in section 5.

3.5. Cases investigated

In this study, two cities served as case studies: Pelotas, in Brazil, for its national recognition as a tourist destination, and Porto, in Portugal, for its international recognition as a tourist destination. Through the MTnoDR matrix, we compared different tourist destinations to identify if they were territorial brands. The matrix provided here will still allow us to understand the influence of destination image on the production process of the territorial brand from the perspective of G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018).

The city of Pelotas, in Brazil, was selected for the study because it was the only case in which a municipal decree was created to keep its territorial brand active. The city is nationally recognized as the capital of sweets, and there is an annual event that strengthens this reputation. In 2017, Pelotas created its first territorial brand that remains active even after four years of government, which is uncommon in Brazil. Its territorial brand involves the feeling of local belonging from the slogan, Sou + pel, and its production process minimally inserted civil society through a contest among undergraduate students from six local universities. In Brazil, Pelotas is a national reference as a tourist destination, being one of the Brazilian tourist routes recommended by the Brazilian Tourism Company (Embratur, Citation2021). Pelotas is in the country’s Southern Region and became a Brazilian cultural heritage site in 2018 due to its sweet tradition as an intangible Brazilian heritage.

The city of Porto was chosen because it is a territorial brand of international recognition, being referenced as a successful case of studies focused on place branding. The production process of this brand adopts a top-down process in which the society was also minimally inserted through a contest of local designers. The brand, Porto, was created in 2016 and used a set of 60 pictograms that graphically represent parts of the city. This brand also draws attention for having been the victim of an alleged case of plagiarism by the city of Berlin, Germany (Marques, Citation2015; Ribeiro & Providência, Citation2015). Besides its territorial brand, Porto’s reputation refers to the recognition of the quality of its wines, the Port wine. The city is in the Northern Region of Portugal and is rich in history and cultural heritage. It is also a city that mixes antiquity with the contemporary, making Porto a cosmopolitan city.

The research was developed from January 2021 to June 2022 and updated in 2023.

4. Analyses

4.1. Analyses Porto (Portugal) and Pelotas (Brazil)

4.1.1. Territorial brand

The brand Porto was created in 2016, and Pelotas in 2017, the name of the cities being the verbal nomenclature of the brands (Figure ). Also, neither of the cities had previously planned territorial brands.

The Porto brand appropriated the port city’s function, using the slogan “Porto Ponto” and using, as a visual resource, a set of 60 pictograms. Pelotas’ brand is based on its national recognition in the production of sweets, the Pelotas sweets, which originated from the local festival called Fenadoce. The brand slogan, “Sou+Pel” (I am more Pel), generates a feeling of belonging in the citizens to value the history of the city that, from 1780 to 1910, was based on a salty cycle (charque production), from which derived its economic and cultural wealth; passing to the current sweet cycle (Fenadoce) for which it is nationally recognized.

The brand structure includes discursive, verbal, and visual elements. They are linked to the territories through distinctive signs and discourses based on local belonging with different strategies. Territorial identity is used as raw material, taking territory as a product of collective order. In general, the touchpoints of both brands, Porto and Pelotas, used traditional media in the Brazilian case and street furniture in the Portuguese case. The use of contact points, strategies, discourses, creation of identity for the brand, and logo (verbal and/or visual) refer to the universe of the brands, verifying that they are brands and not logos disguised as brands and applied to the territory (which would refer to isolated strategies of advertising marketing). In the case of the cities researched, both are territorial brands.

4.1.2. Territory

The construction of the city’s brand brought about the transition from “salt to sugar,” which was referenced in the briefing sent to the brand’s developers. That document contained information about the vision of the local government about the city and the features they wanted to highlight in that territory. They highlighted the connection of the territory with its productive cycles that generated economic development for the city. Besides, Pelotas is a Brazilian city of tourist nature, being Fenadoce nationally recognized and, annually, attracts countless tourists due to the reputation derived from its Portuguese gastronomy. In this sense, the representations of the city carried in the brand came mainly from the Portuguese culture, considered hegemonic. The narratives of this culture, especially the sweets produced, generated the city’s reputation until now.

In Porto City, the historical-territorial highlights the function of the port city in the sense of local valorization. This is stated in the brand slogan, “Porto. Ponto”. It is as if to say, “We are a port, and that is it; no more to declare.” At the same time, the brand’s set of pictograms, unlike the Brazilian brand, praises the plurality of its territory through distinctive icons. The brand itself is generic and only verbal, using a bold, traditional sans serif font, which can refer to the reading of the territory itself, which is also linked to its cultural heritage and recognized for its tradition of wine production. Using pictograms makes the narratives visually included in the brand logo, generating a verbal-visual discourse found in the brand slogan. In the case of the Pelotas brand, the narratives are concentrated on its slogan, “Sou+Pel,” and not on its logo.

4.1.3. Territorialities

Until 2021, Pelotas is the only city surveyed with a decree-law to maintain the brand post the government that created it in 2017, confirming that in Brazil, the character of territorial brands is promotional, while in Europe, it is institutional. This difference influences in two ways: the duration of the territorial brand’s validity (ephemerality of the brand) and the social actors’ vision of territory through a brand. This short- or long-term vision generates another reputation for the territory or maintains an existing territorial reputation. In Pelotas City, the reputation focuses on a sweet cycle of local production (Portuguese sweets) praised by a local festival of national scope (Fenadoce). The festival above also strengthens the local hegemonic culture’s beliefs and the city’s image, leading to physical and symbolic consumption.

In the case of Porto, the city’s image comes from the reputation of the brand design that went beyond the local context to the international context, which is rare. This brand was even involved in an alleged case of plagiarism by the city of Berlin, Germany, broadening the discussion on territorial brands and their closeness and differences with marketing brands. The city has a tourist infrastructure that generates two types of consumption, physical and symbolic, leading to the experiences provided by the brand. In this sense, there are also two types of experiences: one provided by local beliefs and cultures and the other fostered by the brand experience. Both cities surveyed have these two experiences, and the experiences of these brands centred on the feeling of local belonging and the worldview of a given set of social actors. Pelotas reinforces this feeling only in its slogan, “Sou+Pel.” Porto reinvigorates this feeling in three ways: logo (Figure ), slogan (Porto Ponto), and 60 pictograms.

4.1.4. Strategic articulations

One of the differences between a brand and a logo is the presence of unique strategies. Given this, both cities studied can be considered territorial brands. However, they appropriated different strategic articulations to establish the vision of the hegemonic social actors. It should also be noted that this set of actors may change over time, leading to other strategies to meet other visions of a new set of social actors.

Some articulations were similar between the Brazilian and the Portuguese city, as was the case of the production process of both brands through contests. The stratagems were different, but in essence, both used designer contests, and the starting point for creating the brands came from the local public power. In the investigated brands, there is the vision of social actors from the public power, leading to a top-down format of brand creation. However, the use of a contest that brings other social actors to the productive process, such as civil society, is also configured as a bottom-up format. Thus, there is a mixed or hybrid format in which territorial brands use both formats, as was the case in Porto and Pelotas, being, at the same time, articulations of social actors in the promotion of their brands for the city. Creating a municipal decree for the brand to be maintained after the four years of local government is also a strategy of the social actors to keep their worldviews active, as was the case of Pelotas.

These visions penetrate the territorial brands, generating symbolic disputes in different spatial scales. For the Porto brand, the scale is international; for Pelotas, the scale is regional, and the choice of these scales is a strategic articulation. Another strategy used is territorial identity as raw material in the city brand’s productive, communicative, and creative processes, impregnating it with multiple dimensions and interests of social actors. Moreover, the territorial brand from the regional development also refers to the use and appropriation of the territory by social actors.

5. Results and discussion

The variables analyzed corroborate that the destination image can influence the three processes of the territorial brand in regional development in the same way that the territorial brand can influence the emergence of a destination image. This demonstrates that both constructs are co-dependent of each other, while they are also independent, generating multidimensional relationships in multiple scales.

When a destination is seen in the light of the concept of territorial branding in regional development, it is also considered to analyze the plurality of social actors in the territory and the power relations established and in dispute. Not all destinations can be taken as territorial brands planned in a regional development context, but all destinations appropriate, at some point, territorial branding strategies. When linked to territorial brands in a broader sense, destinations promote economic development, where the focus is on local income generation. The brands of Porto (Portugal) and Pelotas (Brazil) analyzed in the mentioned methodological-analytical matrix allowed us to map both destinations’ images, differentiating them from each other from the variables of territorial branding in regional development.

The resulting analysis shows that the image of a destination is one of many ways it is perceived. However, it is a differentiation factor that can lead to the implementation of the territorial brand. Although the territorial brand literature is mainly focused on economic development, the concept of territorial branding in regional development by G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018) makes it evident that this is not the only type of development generated; there may be others, such as regional, cultural, environmental, social, tourism or political development. These developments may overlap and generate different uses and appropriations of the territory. The image of a destination reinforced in the matrix MTnoDR expands the worldview of social actors who produce and live in each territory. One can illustrate this result found with the case of Pelotas, which goes from local narratives focused on a salty cycle to another, more current, focused on a sweet cycle, arising from the local-regional boost of a festival with the intention of national tourism recognition. Thus, the image of a destination is confirmed as a communicator of expectations. This study goes even further, complementing that this communicator function refers to specific expectations, such as those of the social actors that foster both the image of the destination and the territorial brand. In doing so, it is necessary to have a set of beliefs that corroborate with the cultural-territorial manifestations.

It is believed that when a tourist destination has a territorial brand and considers the diversity of the territory and plurality of social actors present in this collectively produced space, this link between destination image and territorial brand can further influence the selection process of destinations and their return by tourists. The territorial brand further strengthens the positioning of a tourist destination because specific strategic articulations are peculiar to the universe of brands. In this sense, the image of a destination becomes a dependent variable of the territorial brand in regional development. Even this dependence can intervene in the set of attributes and local tourism components, linking tourism to other development beyond the economic. Thus, the image would not be the main component in promoting a destination, as highlighted by Fakeye and Crompton (Citation1991). However, it would be one of the components of the territorial brand that would generate a strategic image for destinations.

According to G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018), not always an image can build a brand because the brand can arise from the function of a destination, for example, as was the case of the city of Porto that reaffirmed its positioning as a port city (“Porto. Ponto”). This means that when a destination is analyzed through the analytical lens of Matriz MTnoDR, the destination is not always a product since the product and brand are distinct. The same applies to the destination having an image that represents it graphically without using singular strategies for its promotion, which refers to logos applied to destinations in the sense of only identifying them in some way. When a brand is being addressed, it goes beyond tourism promotion or economic growth, entering tourism development and territorial-regional development. The brand image evokes the diversity of the destination, and this peculiar characteristic generates an image of the destination and not the opposite.

Thus, the variable destination image can be seen both as dependent on the territorial brand and as an independent variable. When seen as independent, the postulates found in the literature consider that the brand is generated from the image of the destination, being the destination a product and the brand the image of this tourism product. When seen as a dependent variable of the territorial brand in regional development, the destination ceases to be a product. It becomes a territory signaled by some of its unique characteristics that may (or may not) become an image of the destination because the brand works with the idea of brand identity (how social actors use and appropriate the territory) different from brand image (how other social actors, such as tourists, for example, see the territory). In the case of the Pelotas brand, there is an appeal to a more marketing image (focused on a local event) than the Porto brand, where the appeal is institutional. However, this may be related to how both countries understand the brand concept, whether in an ephemeral vision (promotional) or the long term (institutional).

6. Conclusion

The increase in global urbanization has made cities protagonists, acquired multiple roles, and influenced the transformation of urban spaces and strategic governance arrangements. The reality that presents itself can no longer rely on the concept of the destination image of past centuries because there are new social and historical contexts inserted. One of them is the territorial brand focused on regional development that can become a new variable for the destination image in a contemporary perspective of urban-territorial protagonism.

The research objective was met to the extent that it allowed the analysis of the destination image in the productive process of the territorial brand in regional development, confirming to be a two-way influence (dependent and independent). There was a specific tool for analyzing the destination image’s influence on the territorial brand’s production process in Regional Development, the MTnoDR matrix.

6.1. Main results

The main results allude to the use of the concept and the MTnoDR matrix proposed by G. G. F. Almeida (Citation2018), which can be applied in analyzing tourist destinations’ images, allowing two distinct readings (one individual and one integral). It was also found that not always a destination image can build a brand in the breadth of G. G. F. Almeida’s (Citation2018) concept because, for this, it is necessary to consider, among other points, the diversity of the territory and the plurality of social actors going beyond economic development. At the same time, received space in the study of the dependence and independence between destination image and territorial brand, and there may still be a co-dependence between both. This discards the idea of the absence of dependence between the constructs.

6.2. Contributions

Among the research contributions is the originality in investigating the interrelationships between destination image and the concept of the territorial brand in Regional Development and unprecedentedness in the proposal of a methodological protocol supported in MTnoDR to analyze destination image. For the area of tourism, the study also contributes to the discussion of the correlation between destination image and territorial brand, being original in its discussion of the scope of regional development and its analysis through the lens of the territorial brand in a broader concept than those, frequently, found in the literature of tourism and place branding. The perspective of the study is supported by the set of variables investigated that discuss the image of urban destinations and their challenges concerning the contemporary urban. This interdisciplinary discussion includes urban-regional studies, tourism, cultural studies, branding, local-territorial-regional development, and related areas. As a result, managers, planners, and researchers can better plan strategies for destinations as valuable territorial assets.

6.3. Theoretical implications

The research presented has important theoretical implications for understanding the role of destination image and the concept of the territorial brand in regional development. In theoretical terms, the research shows that destination image and territorial brand are interdependent constructs that can influence the productive process of the territorial brand from the theories of regional development. This suggests that the construction of the territorial brand considers the image of destinations to be effective in promoting regional development. Furthermore, the research proposes a methodological protocol based on the territorial brand to analyze destination image in regional development contexts, different from place branding models. This new approach may be helpful in other studies, especially in interdisciplinary areas, because it offers a clear framework for analyzing these constructs.

The research uses a qualitative approach based on case studies, but a mixed approach could provide a more comprehensive and robust view of these relationships. This would allow researchers to identify more general patterns in the relationships between destination image and territorial brand and test broader hypotheses in different regional development contexts.

6.4. Practical implications

In practical terms, constructing the territorial brand can be an effective strategy to promote regional development and can consider the established destination image. This may involve promoting a clear and distinctive regional identity that reflects the unique characteristics and values of the region. This approach can attract investment, tourism, and other economic, social, and sustainable development forms. However, the research also highlights that each case of regional development is unique and that outcomes may vary according to the specific characteristics of the region. This suggests that strategies to build the territorial brand must be adapted to each specific context to be effective. Furthermore, the study highlights that public and private managers must work together to develop an effective territorial brand strategy that reflects the territory’s identity and can promote its development based on its destination image.

6.5. Limitations and futures research

Research limitations extend to having been investigated only in international databases, suggesting future research the investigation in Brazilian scientific databases to compare the results. In addition, only two cities were surveyed, making it possible to expand the scope of the study to more destinations and compare the results with each other. For further research, we suggest analyzing the impact of territorial branding linked to destination image in the context of regional development, addressing the work developed and empirical studies published.

6.6. Concluding remarks

The conclusion reiterates that the image of a destination influences the creation of the territorial brand and vice-versa, proposing multiple relations between brand, territory, and destination. It is also a two-way influence confirmed through the analytical and methodological matrix MTnoDR that investigates the relationship between brand and territory in regional development. In addition, the use of the territorial brand, considering the destination’s context-historical, can lead to different types of development. This happens because development is unique and varies according to the context, the specific characteristics of each territory, and the interests involved. Even though both are tourist destinations, Porto in Portugal and Pelotas in Brazil have different contexts and interests, which influence the approaches and priorities for development and the use of their territorial brand. A series of factors, such as available resources, geographical characteristics, and historical-cultural, political, and economic aspects, shape the development. Each territory has its own particularities and specific demands, and development strategies can be adapted to meet the needs and aspirations of each locality. The same happens with the use of the territorial brand that accompanies the development strategies of its cities. Development has international interests in Porto, and in Pelotas, development is more regional. These interests are also present in the territorial brand, but subtly, because it is a strategy of the social actors. Therefore, it is valid to state that development is not the same in any territory. Nuances and differences arise according to the particularities and interests of each region. These differences extend to creating the territorial brand, highlighting the influence of specific characteristics and individual interests in constructing a territory’s identity and image.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Giovana Goretti Feijó Almeida

Giovana Goretti Feijó de Almeida Mini currículo – PhD in Regional Development (UNISC, Brazil) with Post-Doctorate in Urban Management/Strategic Digital City (PUCPR, Brazil) and Post-Doctorate in Tourism/Destination Image/Destination Branding (Polytechnic University of Leiria, Portugal). My research involves discussions about Territorial Brand, Cultural Studies, Regional Development and Destination Image. I am member of the Centre for Tourism Research, Development, and Innovation (CiTUR - Polytechnic University of Leiria, Portugal).

Paulo Almeida

Paulo Almeida Mini currículo - PhD in Marketing and International Trade, University of Extremadura, Spain. Master’s degree in Tourism Management and Development from the University of Aveiro. Graduated in Hotel Management from the University of Algarve. I am Director of the Escola Superior de Turismo e Tecnologia do Mar (ESTM). I am effective member of the Academic Council of The IPL, an effective member of the Technical-Scientific Council of ESTM and an effective member of CiTUR - Research, Development and Innovation Group, being Executive Editor of EJTHR - European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation. As a researcher I am have published some works and articles in the area of Tourism Animation Management and the Image of Tourist Destinations, trying to understand the problem integrated in the development and promotion of tourist destinations. As a professor I teach and guide several dissertations in the Master’s degree in Hotel Management and Direction and in the Master’s degree in Marketing and Tourism Promotion, which take place at ESTM.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong brands. Simon and Schuster.

- Aaker, D. A., & Joachimsthaler, E. (2000). Brand leadership. Simon and Schuster.

- Almeida, G. G. F. (2018). Marca territorial como produto cultural no âmbito do Desenvolvimento Regional. Tese Doutorado em Desenvolvimento Regional, Universidade de Santa Cruz do Sul.

- Almeida, G. G. F. (2019). The role of urban rankings in the construction of perception on innovation in smart cities. International Journal of Innovation, 7, 119–17. https://doi.org/10.5585/iji.v7i1.391

- Almeida, P. (2011). La Imagen de un Destino Turístico como Antecedente de la Decisión de Visita: análisis comparativo entre los destinos Londres, Paris y Roma. Tese Doutoramento, Universidad de Extremadura.

- Almeida, G. G. F., & Cardoso, C. (2022). Discussions between place branding and territorial brand in regional development: A classification model proposal for a territorial brand. Sustainability, 14(11), 6669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116669

- Anholt, S. (2007). Competitive identity: The new brand management for nations, cities, and regions. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Anholt, S. (2010). Definitions of place branding: Working towards a resolution. Journal of Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.3

- Aranda, L., Férnandez, J., & Manzano, A. (2021). Tourism research after the Covid 19 outbreak: Insights for more sustainable, local and smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 73(103126), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103126

- Ashworth, G., & Kavaratzis, M. (2011). Towards Effective Place Brand Management: Branding European Cities and Regions. Journal of Regional Science, 51(3), 649–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00737_14.x

- Boisier, S. (1999). Desarrollo endógeno y descentralización. Revista de la CEPAL, 68, 63–75.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-51779900095-3

- Burgess, J. A., & Bramwell, B. (2002). Redefining wine tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 27(2), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2002.11081300

- Cambra-Fierro, Cambra-Fierro, J. J., Fuentes-Blasco, M., Huerta-Álvarez, R., & Olavarría-Jaraba, A. (2022). Destination recovery during COVID-19 in an emerging economy: Insights from Perú. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(3), 100188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100188

- Chon, K. (1990). The role of destination image in tourism: A review and discussion. The Tourist Review, 45(2), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb058040

- Cooper, C., Fletcher, J., Shepherd, R., Gilbert, D., & Wanhill, S. (2008). Turismo princípios e práticas (3 ed.). Bookman.

- Crompton, J. (1979). An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon the image. Journal of Travel Research, 17(4), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757901700404

- Currie, S. (2021). Measuring and improving the image of a post-conflict nation: The impact of destination branding. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100472

- Dozier, C. L. (1956). Northern Paraná, Brazil: An example of organized regional development. Geographical Review, 46(3), 318–333. https://doi.org/10.2307/211883

- Embratur. (2021) Empresa Brasileira de Turismo. Disponível em: https://embratur.com.br/ (Retrieved August 21, 2021).

- Fakeye, P., & Crompton, J. (1991). Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the lower rio grande valley. Journal of Travel Research, 30(2), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759103000202

- Faria, A. P., & Marques, R. C. (2017). Endogenous development and place branding: The case of Algarve. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(3), 231–240.

- Ferreira, J. M., & Rebelo, J. (2014). Place branding and endogenous development: A Portuguese case study. Journal of Place Management and Development, 7(2), 102–116.

- Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality, vol. 1: An introduction. Vintage.

- Furtado, C. (2009). Desenvolvimento e subdesenvolvimento. Contraponto: Centro internacional Celso Furtado.

- Gartner, W. B. (1986). Image formation process. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 472–482. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_12

- Geertz, C. (2008). A interpretação das culturas. LTC.

- Grönroos, C. (1994). Marketing y Gestión de Servicios. La Gestión de los Momentos de la Verdad y la Competencia en los Servicios. Ediciones Díaz de Santos: Madrid.

- Hakala, U., Lemmetyinen, A., Kantola, S., & Melewar, T. C. (2013). Country image as a nation-branding tool. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 31(5), 538–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-04-2013-0060

- Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/Decoding. Culture, Media, Language, 128–138.

- Hankinson, G. (2004). Relational Network Brands: Towards a Conceptual Model of Place Brands. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10, 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670401000202

- Harvey, D. (2001). Spaces of capital: Towards a critical geography. Routledge.

- Holloway, J. C. (1994). The business of tourism. Logman.

- Hunt, J. D. (1975). Image as a factor in tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 13(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757501300301

- Hunter, W. C. (2022). Semiotic fieldwork on chaordic tourism destination image management in Seoul during Covid-19. Tourism Management, 93, 104565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104565

- Jansson, J., Lucarelli, A., & Brorström, S. (2014). Marketing a destination’s cultural identity - the image of Sweden conveyed through destination branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.816059

- Kapferer, J. N. (2012). The new strategic brand management: Advanced insights and strategic thinking. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Kavaratzis, M. (2004). From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Branding, 1(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990005

- Kavaratzis, M., & Hatch, M. J. (2021, January). The elusive destination brand e o ATLAS wheel of place brand management. Journal of Travel Research, 60(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519892323

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Keller, K. L. (2008). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Pearson Education.

- Konecnik, M., & Chernatony, L. (2013). Developing and applying a place brand identity model: The case of Slovenia. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.05.023

- Kotler, N., Haider, D., & Rein, I. (2002). Mercadotecnia de Localidades. In M. Gallarza & I. Saura. and H. Garcia (Eds.), Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework (pp. 56–78). Annals of Tourism Research, 29.

- Kumar, N., & Panda, R. K. (2001). Place branding and place marketing: A contemporary analysis of the literature and usage of terminology. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 17(2), 255–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-019-00230-6

- Lalicics, L., Marine-Roig, E., Ferrer-Rosell, B., & Martin-Fuentes, E. (2021). Destination image analytics for tourism design: An approach through Airbnb reviews. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 103100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103100

- Liu, J., Li, J., Jang, S., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Understanding tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior at coastal tourism destinations. Marine Policy, 143, 105178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105178

- Lucarelli, A. (2018). Place branding and endogenous development. In Routledge handbook of place (pp. 487–500). Routledge.

- Luo, J., Okumus, F., & Taheri, B. (2022). Destination image perception of Shenzhen: An analysis of discourse based on Chinese and western visitors’ online reviews. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 13(4), 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-08-2020-0188

- Marques, R. O. (2015) Site Institucional da Meio e Publicidade. Berlim suspende imagem de projecto semelhante à marca Porto. Disponível em: https://www.meiosepublicidade.pt/2015/05/berlim-suspende-imagem-de-projecto-semelhante-a-marca-porto/. Acesso em: 28 out 2021.

- McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1086/209217

- Nicholls, W. H. (1956). The effects of industrial development on Tennessee Valley agriculture, 1900-1950. Journal of Farmaceutica Economics, 38(5), 1636–1649. https://doi.org/10.2307/1234597

- Ogunyankin, G. A. (2019). ‘The City of Our Dream’: Owambe Urbanism and Low-income Women's Resistance in Ibadan, Nigeria. International Journal of Urban & Regional Research, 43(3), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12732

- Pan, X., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2021). Investigating tourist destination choice: Effect of destination image from social network members. Tourism Management, 83, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104217

- Pastak, I., & Kährik, A. (2021). Symbolic displacement revisited: Place-making narratives in gentrifying neighbourhoods of Tallinn. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45(5), 814–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13054

- Perrin, N. (1956). La répartition géographique de la population française et l’aménagement du Territoire. Population (French Edition), 11(4), 701–724. French Edition. https://doi.org/10.2307/1524715

- Perroux, F. (1961). Economic space: Theory and applications. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 75(1), 89–104.

- Perulli, P. (2012). Visões da cidade: as formas do mundo espacial. Senac.

- Phelps, A. (1986). Holiday destination image — the problem of assessment: An example developed in Menorca. Tourism Management, 7(3), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(86)90003-8

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400820740

- Qu, Y., Dong, Y., & Gao, J. (2022). A customized method to compare the projected and perceived destination images of repeat tourists. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 25, 100727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2022.100727

- Rafael, C. (2016) Impacto de la Experiencia Virtual on-line en la Formación de la Imagem del Destino Turístico. PhD thesis não editada. Universidad de Extremadura,

- Raffestin, C. (1993). Por uma geografia do poder. Ática.

- Ribeiro, M., & Providência, F. (2015). A point between points: Brief reflection about creativity and innovation in design. Revista dos encontros internacionais de estudos luso-brasileiros em Design e Ergonomia, 5(1), 44–51.

- Saarinen, J. (2004). Destinations in change: The transformation process of tourist destinations. Tourist Studies, 4(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604054381

- Santos, M. (2000). A natureza do espaço: Técnica e tempo, razão e emoção. Editora da UFMG.

- Schmidt, P. J. (1926). On the development of the regional survey in Soviet Russia. The Sociological Review, 18(2), 106–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1926.tb01566.x

- Sen, A. (2000). Desenvolvimento como liberdade. Companhia das Letras.

- Sotoudehnia, M., & Rose-Redwood, R. (2019). ‘I am Burj Khalifa’: Entrepreneurial Urbanism, Toponymic Commodification and the Worlding of Dubai. International Journal of Urban & Regional Research, 43(6), 1014–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12763

- Souza, M., & Nemer, A. (1993). Marcas e distribuição. Makron Books.

- Stimson, R. J. (Ed.). (2019). Handbook of research methods and applications in regional science. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Stöhr, W. B. (1981). Development from below: The bottom-up and periphery –inward development paradigm. In W. Stöhr & T. Fraser (Eds.), Org. Development from above or below? The dialectics of regional planning in developing Countries J. Wiley & Sons.

- Stylidis, D. (2020). Exploring Resident–Tourist interaction and its impact on tourists’ destination image. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520969861

- Telisman-Kosuta, N. (1994). Tourist destination image. In S. Witt & L. Moutinho (Eds.), Tourism marketing and management handbook (pp. 557–561). Prentice Hall.

- Thompson, J. B. (1990). Ideology and modern culture: Critical social theory in the era of mass communication. Stanford University Press.

- Touraine, A. (2007). Un nouveau paradigme: Pour comprendre le monde d’aujourd’hui. Fayard.

- Vanolo, A. (2012). The image of the city in tourist literature. Routledge.

- Vela, S. E., Portet, G., & Algado, S. Y. X. (2014). De la marca comercial a la marca de território: los casos de la doc priorat y do montsant. Historia y Comunicación Social, 19, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_HICS.2014.v19.45011

- Warnaby, G. (2017). Place branding and endogenous regional development. In Handbook on place branding and marketing (pp. 295–307). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Warnaby, G., & Medway, D. (2013). What about the ‘place’ in place marketing?. Marketing Theory, 13(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593113492992

- Yin, R. (2015). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Applied Social Research Methods) (15. ed.). Publisher SAGE Publications.