Abstract

While both the prevailing media discourse and extant scholarship commonly posit that the religious beliefs of Muslim women may inhibit their inclination towards physical activities, a fresh wave of critical scholarship has proposed an alternative narrative. The emergent critical perspective posits that Muslim women might extract from their religious beliefs the catalyst for their involvement in physical activity. This research aimed to explore these possibilities in greater depth by employing the social identity theory perspective. In Study 1, the authors collected data from Muslim women (N = 177) living in the US. Results indicate that religious identity was positively associated with physical activity intentions (β = 4.746, p = .010), and this relationship was bolstered among Muslim women with high levels of health consciousness (moderator) (β = 2.826, p < .001). In Study 2, the authors collected data from Muslim women (N = 322) from 34 different countries to explore the intersection of the interplay between the individual and their sociocultural milieu. Again, religious identity was positively associated with self-reported physical activity (β = 7.344, p < .001). This study contributes to the limited knowledge concerning the relationship between religious identity and physical activity participation among Muslim women.

1. Introduction

Regular participation in physical activity relates to psychological, physical, cognitive, and social benefits (Bidzan-Bluma & Lipowski, Citation2018; Eigenschenk et al., Citation2019; Warburton & Bredin, Citation2017; Warburton et al., Citation2006). Nevertheless, disparities exist in access to physical activity and quality of experiences, with variations based on social class (Stalling et al., Citation2022), geographic location (Huston et al., Citation2003), race (Edwards & Cunningham, Citation2013; Mason et al., Citation2019), immigration status (Elshahat & Newbold, Citation2021), gender (Lopez, Citation2019), and sexual orientation (Calzo et al., Citation2014), among other characteristics. The unfortunate consequence of these disparities is an inequitable distribution of the bountiful advantages associated with physical activity, thereby exacerbating existing health disparities (Gordon-Larsen et al., Citation2006; Taylor et al., Citation2007). This inequity grows even more pronounced when we shift our gaze to the non-Western countries, where myriad additional factors might compound the issue’s complexity.

Likewise, researchers have previously underscored that Muslim women frequently report being less active and having fewer opportunities than their peers (Kahan, Citation2015). For example, Muslim women are more likely to lead sedentary lives than Muslim men, and people living in predominantly Muslim countries are less likely to be active than people living in other countries (Kahan, Citation2015; Li et al., Citation2015; Pfister, Citation2010). Scholars frequently point to religious and cultural influences to explain these patterns. Nakamura (Citation2002), for example, examined the physical activity experiences of Muslim women living in Canada, noting that limited access sometimes meant that the women adjusted their activities or stopped being active altogether. In their systematic review, Sharara et al. (Citation2018) registered that cultural aspects in the region constrained Arab women’s physical activity. Similarly, in a qualitative study of women college students in Pakistan, Laar et al. (Citation2019) observed that religious beliefs, along with cultural and socioeconomic factors, constrain physical activity rates.

Nevertheless, a critical body of academic discourse contests the perception that Muslim women’s religious beliefs invariably impede their engagement in physical activity. Sport practitioners, for example, frequently presume that Muslim women are a homogeneous group or encounter similar constraints—neither of which is the case (Agergaard, Citation2016; Ahmad et al., Citation2020; Knez et al., Citation2012). In lieu of this, qualitative examinations of the subject have unearthed that Muslim women often harbor a keen desire to participate in, and indeed frequently engage in physical activity, but in spaces and contexts that might vary from traditional Western practices (Hussain & Cunningham, Citation2021; Summers et al., Citation2018). Further, whereas women’s ethnic identities might serve to limit activity options, some Muslim girls and women feel that being active aligns closely with Islam’s emphasis on being healthy (Walseth, Citation2006).

The purpose of this paper is to explore (a) equivocal evidence concerning the role of religion in Muslim women’s desire and ability to be active and (b) heterogeneity in Muslim women’s experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. In the current research, we conducted two studies focusing on one factor that could help clarify these patterns: religious identity. As outlined in the following section, we suggest that Muslim women with a stronger religious identity (i.e., while having the desired freedom) are more likely to be physically active than their less religiously identified peers. We also note that other factors might influence the relationship between religious identity and exercise behavior, thereby signaling the importance of moderators (Cunningham & Ahn, Citation2019). In Study 1, we examine whether health consciousness moderates this relationship, and in Study 2, we examine the moderating effects of religious similarity to others.

2. Theoretical framework: Social identity theory

Howard (Citation2000) underscored that an individual’s identity embodies dual facets: the subjective and the collective. This interpretation catalyzed the evolution of two critical perspectives towards discerning an individual’s identity: the sociological and the socio-psychological (Howard, Citation2000). To begin with, proponents of symbolic interactionism, a sociological framework, have historically posited that individuals attribute specific meanings to their own identities and those of others, disseminating these meanings through social interactions (Mead, Citation1934). Consequently, adherents of symbolic interactionism situate the interpretation of identity in the realm of sociological parameters (Burke & Stets, Citation2009; Stryker, Citation1980). In contrast, theorists operating within the purview of social cognition have delineated how individuals compile and process information using cognitive schema (Fiske & Taylor, Citation1991). Tajfel (Citation1979, Citation1982) emphasized that these cognitive schemas are socio-psychologically established, which serves as a means for emerging social categories. This notion of Tajfel (Citation1979, Citation1982) aided in the advancement of the social categorization framework, which comprises two theoretical views: social identity theory (Tajfel, Citation1978; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner et al., Citation1987).

The core premise of social identity theory (Tajfel, Citation1979; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) posits that individuals articulate their identity via two primary axes: personal and social. The social aspect of identity is characterized by an individual’s perceived association or membership with a specific social group, termed the in-group (Tajfel, Citation1978; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Therefore, people define the group they perceive they fit into as the in-group (We), while individuals outline the other groups as out-groups (Tajfel, Citation1978; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). For instance, Muslim women athletes in the USA might contemplate themselves as an in-group because of robust religious attachment and all the other individuals as an out-group.

Moreover, viewed through the lens of social identity theory (Tajfel, Citation1978; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979), one’s personal identity emerges as a pivotal component of their self-concept, serving as a distinguishing factor within a specific environment (Brewer, Citation1991). The individual’s personal identity profoundly contributes to the creation of their self-image, embodying their uniqueness and significantly swaying their self-understanding (Luhtanen & Crocker, Citation1992; Randel & Jaussi, Citation2003). Ultimately, individuals construct their personal identity utilizing a plethora of characteristics—these may include race, gender, sexual orientation, and religion, among others.

Thus, religious identity mirrors the extent to which an individual’s religious convictions form the foundation for their personal identity (Cunningham, Citation2010; Ladd, Citation2007). In this case, religious attitudes and beliefs inform how people see themselves as relative to others, affect their self-image, and contribute to their feelings about themselves. Research across many domains suggests people’s religious identities have the potential to shape many parts of their lives, such as their work experiences, mental health, medical choices, and acculturation among immigrants, among other outcomes (Chu et al., Citation2021; Ellison et al., Citation2013; Héliot et al., Citation2020; Phalet et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, people who follow a particular religious tradition can express varying strengths of religious identity. Among Muslims, for instance, religious beliefs might strongly contribute to some people’s personal identity, whereas for others, it is less important. In the current study, we expected that, among Muslim women, those with a strong religious identity (provided the given freedom) would be more likely to be physically active than their less-identified peers. Walseth and Fasting’s (Citation2003) work contributes to this understanding. They collected qualitative data from 27 Muslim women in Egypt, who held that Islam emphasized health and sport participation. Those connections were most strongly endorsed among women who were closely connected with their religious views. Similarly, Rubio‐Rico et al. (Citation2021) interviewed Moroccan Muslim women about their involvement in physical activity. Some women viewed their physical activity as one part of a holistic view of Islam, and their physical activity helped them connect more closely with their religious tradition. These findings align with broader scholarship (i.e., not focused solely on Muslim women), showing that religious and spiritual beliefs can shape people’s physical activity and the well-being they derive from it (Noh & Shahdan, Citation2020). Drawing from this research, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1:

Religious identity will be positively associated with physical activity participation among Muslim women.

As previously noted, we examined the influence of religious identity across two studies and included two moderators. In the following section, we introduce Study 1 and offer the theoretical rationale for the first moderator: health consciousness.

3. Study 1

Health consciousness, or the degree to which people are aware of their health and express a willingness to improve it (Gould, Citation1990), is one such moderator. Health-conscious people will seek out information about ways to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and their behaviors frequently follow. Health-conscious people are likely to seek healthy eating options (Koinig, Citation2021), make travel and vacation decisions that promote healthiness (Pu et al., Citation2021), and even take steps to alleviate environmental contaminants that might adversely affect their health (Shimoda et al., Citation2020). Health-conscious people are also likely to pursue active lifestyles (Hong & Chung, Citation2022), even devising ways to exercise in the face of substantial barriers (Pu et al., Citation2020).

Individual differences potentially relate to health consciousness. In a study of Finnish adults, Ek (Citation2015) found that women were more likely than men to seek out health-related information and receive feedback from people close to them. Furthermore, women who perceive health risks are more likely to seek out health-related information online when they are health-conscious and believe the Internet is a valuable tool for obtaining said information (Ahadzadeh et al., Citation2018). Coupled with the research related to religious identity, this scholarship suggests that health-conscious people might engage in more physical activity and that the benefits might be amplified among women whose religious beliefs inform their identity. However, some researchers have found that health consciousness is most prevalent when other identities are low. For example, in a qualitative study out of Pakistan, Bukhari and colleagues found that religiosity influenced food choices for some of their participants, but for others, health consciousness was more salient (Bukhari et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Rogers and Papies conducted a qualitative study of adults from around the world. They found that health consciousness was related to water intake except when other identities (e.g., religious identity) were more salient (Rodger & Papies, Citation2022). Given the mixed pattern of findings, we developed a research question instead of a specific prediction:

Research Question 1:

What is the relationship between health consciousness, religious identity, and participation in physical activity?

3.1. Research method (Study 1)

3.1.1. Participants

The Muslim women living in the US (N = 177) participated in the study via Amazon mTurk. The mean age was 33.28 years (SD = 10.42) and ranged from 18 to 65 years. Most had earned an undergraduate degree (n = 114, 64.4%) or a graduate degree (n = 53, 29.9%). In terms of marital status, most identified as married (n = 130, 73.4%), followed by single (n = 40, 22.6%), in a domestic partnership (n = 3, 1.7%), separated (n = 2, 1.1%), widowed (n = 1, 0.6%), and divorced (n = 1, 0.6%). Finally, participants were asked to rate their family’s wealth, ranging from 1 (very poor) to 7 (very wealthy), and the mean score was 5.21 (SD = 1.33), with values ranging from 1 to 7.

3.1.2. Materials

Participants responded to a questionnaire measuring their demographics (as outlined in the previous paragraph), religious identity, health consciousness, and physical activity, as well as an attention check. We used three items adapted from Cunningham’s study (Cunningham, Citation2010): “in general, my religion (Islam) is an important part of my self-image,” “my religion (Islam) is an important part of who I am as a person,” and “overall, my religion (Islam) has a lot to do with how I feel about myself.” Participants responded on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The reliability (α = .75) for the scale was acceptable. We took the mean of the three items to reflect the final Religious Identity score.

We drew from Gould’s work to measure health consciousness (Gould, Citation1988). The measure included nine items, and examples include: “I am constantly examining my health,” “I am alert to changes in my health,” and “I am usually aware of my health.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The reliability estimate (α = .86) demonstrated acceptable levels of internal consistency. The mean of the nine items reflected the final Health Consciousness score.

Finally, we used a single item to assess physical activity: “What is the probability out of 100 that you will take moderate exercise for long enough to work up a sweat at least three days a week during the next three weeks?” Response options were in 10-point increments and ranged from 0–10 to 91–100. Bozionelos and Bennett demonstrated the efficacy of using this measure in their study of physical activity among students at the University of Bristol (Bozionelos & Bennett, Citation1999). Finally, consistent with recommendations for online data collection (Aguinis et al., Citation2020; Hauser & Schwarz, Citation2016), we included an attention check: “Your birthday is December 32, 2021.” We excluded the responses from those participants who marked “true” (n = 7).

3.1.3. Procedures

We first received approval from the Institutional Review Board (Texas A&M University: IRB2020–1367) to conduct the research. This research is part of a larger study examining Muslim women’s attitudes toward sport and physical activity. For this portion of the project, we collected data using the Amazon mTurk portal. This platform is useful when collecting data from what is otherwise hard to reach (Smith et al., Citation2015). We paid participants $1.50 for their time.

3.1.4. Analyses

We computed descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, or frequency) and bivariate correlations for each study variable. We then examined Hypothesis 1 and Research Question 1 through moderated regression, following Hayes’ PROCESS models (Hayes, Citation2022). We included four controls—age, marital status (married or not), education (college degree or not), and subjective family wealth—and standardized the religious identity and health consciousness to reduce multicollinearity (Cohen et al., Citation2003). We then specified Model 1 in the PROCESS macro.

3.2. Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table . Overall, Muslim women anticipated engaging in moderate physical activity levels over the next three weeks (M = 74.557, SD = 21.592). Women with a college degree and who came from wealthier families had greater physical activity intentions than their peers. This result is in line with previous investigations concerning a strong association among physical activity, education level, and the income level of a population. For example, in a study of Finnish adults, Kari et al. (Citation2015) found that income held a positive association with self-reported physical activity levels, and the patterns were consistent among women and men and were robust to the inclusion of control variables. Further, in a study of Polish adults, Puciato and colleagues reported that people with the most regular physical activity were also wealthy with little debt (Puciato et al., Citation2018). Further examination of the bivariate correlations shows that religious identity and health consciousness are positively associated with physical activity intentions. These relationships are consistent with our theorizing.

Table 1. Study 1 descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

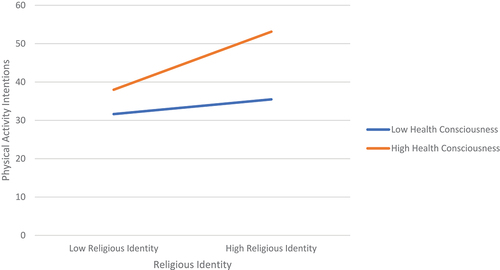

Turning to the regression model, the results are presented in Table . The model explained 43.2% (p < .001) of the variance in physical activity intentions. Age, marital status, and college degree were not significant, but family wealth had a significant positive effect. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, religious identity was positively associated with physical activity intentions (β = 4.746, SE = 1.821, p = .010). Health consciousness was also related to physical activity intentions (β = 6.002, SE = 1.844, p = .001). Finally, the religious identity × health consciousness interaction term was significant (β = 2.826, SE = .686, p < .001). We computed simple slopes and plotted the interactions in Figure . When health consciousness was low, the relationship between religious identity and physical activity intentions was not significant (β = 1.574, SE = 1.796, p = .382); however, when health consciousness was high, religious identity was highly predictive of physical activity intentions (β = 7.618, SE = 2.103, p < .001).

Figure 1. Relationship among religious identity, health consciousness, and physical activity intentions (Study 1).

Table 2. Study 1 results of moderated regression predicting physical activity intentions

In summation, findings from Study 1 corroborate preceding qualitative research in this domain, indicating that the potent religious identity of Muslim women should not be misconstrued as an impediment to sports participation (Agergaard, Citation2016; Hussain & Cunningham, Citation2021). Contrary to popular narratives, Muslim women research participants in our study perceived Islamic faith as conducive to engaging in sport activities (Agergaard, Citation2016; Walseth, Citation2006). The results of our investigation demonstrate that Muslim women possessing a heightened consciousness towards health strive towards physical activity. This observation fortifies the arguments posited by earlier researchers concerning the robust association between health consciousness and participation in physical activities (Hong & Chung, Citation2022; Pu et al., Citation2021).

4. Study 2

In Study 1, we showed how individual-level factors—religious identity and health consciousness—interacted to explain the physical activity among Muslim women. In the second study, we broadened the focus to examine the intersection of the individual relative to their social setting—an approach consistent with multilevel theorizing related to physical activity and sport (Cunningham, Citation2019; Golden & Earp, Citation2012). Specifically, we examined the potential role of being religiously similar to others.

We previously suggested that, among Muslim women, people with a strong religious identity would be more likely to be physically active than their less identified counterparts. This relationship stemmed partly from reports showing that Muslim women sometimes interpreted Islam as emphasizing health and wellness (Hussain & Cunningham, Citation2021; Rubio‐Rico et al., Citation2021; Walseth & Fasting, Citation2003); thus, being active was consistent with their religious beliefs. Being around others with similar religious beliefs might further strengthen these connections. In these instances, the religious precepts might (a) be embedded into the culture and accepted way of doing things, (b) shape expected behaviors for the self and others, and (c) exert considerable influence on people’s attitudes and behaviors. These ideas are consistent with Payne et al. (Citation2017) presentation of concept accessibility; that is, when a belief system is embedded within a community, people living in that setting are readily aware and able to cognitively access the attitudes, evaluations, and behaviors prescribed by that system. In the context of the current study, these dynamics suggest that when Muslim women are surrounded by other Muslims, Islam’s tenets (which religiously identified women use as the basis for their physical activity) might be salient. In these instances, religiously identified women might be more physically active than their similarly identified peers who do not live in areas with many Muslims.

We could not identify previous work that examined the links among religious identity, religious similarity, and physical activity, but there is related scholarship. For example, Sechrist et al. (Citation2010) examined parent-child religious similarity over time, finding that congruence in beliefs was predictive of quality relationships later in life. Similarly, older women report better health when they are in marriages with spouses who share their views (Upenieks et al., Citation2021). The opposite also occurs, as being religiously different from others is linked to the feeling of deeper, value-based differences and a lack of satisfaction with the group (Cunningham, Citation2010). Based on this research, we developed a second research question:

Research Question 2:

What is the relationship among religious similarity, religious identity, and physical activity participation?

4.1. Research method

4.1.1. Participants

Participants included 322 women who identified as Muslim and lived in 34 countries around the world. In terms of regions of the world, study participants living in Africa (n = 1, 0.3%), Asia (n = 109, 33.9%), the Caribbean (n = 3, 0.9%), Europe (n = 30, 9.3%), North America (n = 160, 49.7%), and South America (n = 15, 4.7%). The average age was 30.41 (SD = 8.54) and ranged from 18 to 65 years. The mean rating of family wealth, with 7 indicating very wealthy, was 4.88 (SD = 1.22). Most of the participants indicated they were married (n = 199, 61.8%) or single (n = 114, 35.4%). The sample was also educated, as 57.1% (n = 184) had an undergraduate degree, and 34.1% (n = 110) had earned a graduate degree.

4.1.2. Measures

Participants responded to a questionnaire where they provided their demographics (as noted in the previous paragraph) and responded to items measuring their religious identity (α = .83) and physical activity intentions. The measures were the same as those in Study 1. We also included the same attention check variable, excluding the responses from people who did not answer it correctly. Finally, drawing from a Pew Research Center report (Lipka, Citation2017), we assessed religious similarity by noting the percentage of Muslims in the country where the participant lived.

4.1.3. Procedures

We first received approval to conduct the research from the Institutional Review Board (Texas A&M University: IRB No. 2020–1367). The study participants were recruited from different countries globally through online communities (e.g., Reddit) and social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter). Prior scholarly dialogue has underscored the efficacy of utilizing digital landscapes (social media, in particular) as instrumental conduits to access and engage with heterogeneous demographic clusters on a global scale (Gelinas et al., Citation2017). For taking part in this research, we gave ten study participants a US$25 Amazon gift card each through a lucky draw, as offering research incentives can enhance the study response rate among various populations (Mercer et al., Citation2015). We collected data for two weeks. We employed power analysis (Hulley et al., Citation2013) to calculate the minimum sample size warranted for this study by using the below formula:

Total sample size = n = [(Zα+Zβ)/C]2 + 3 = 194 (minimum sample desired)

4.1.4. Analyses

We computed descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation, and frequencies) and bivariate correlations for all variables. We then tested Hypothesis 1 and Research Question 2 through moderated regression using the Hayes PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2018). As in Study 1, we included participant age, marital status, college education, and family wealth as controls. We standardized religious identity and percentage of Muslims in the country to reduce multicollinearity (Cohen et al., Citation2003) and specified Model 1 in the PROCESS macro.

4.2. Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are available in Table . The mean score for physical activity intentions was 58.782 (SD = 31.428), indicating that Muslim women in the sample were likely to engage in moderate physical activity three times a week over the next three weeks. From a purely descriptive standpoint, the mean score for the worldwide sample was lower than the US sample in Study 1 (M = 74.557, SD = 21.592). Results showed that only religious identity held a significant, bivariate association with physical activity intentions.

Table 3. Study 2 descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

The results of the moderated regression are presented in Table . The total model explained 6.2 percent of the variance (p = .006)—a small to moderate effect. None of the controls were significant. However, and again in support of Hypothesis 1, religious identity held a positive association with physical activity intentions (β = 7.344, SE = 1.809, p < .001). Finally, the percentage of Muslims in the country was unrelated to physical activity intentions, nor was the religious identity × percent Muslim interaction term (see Table ).

Table 4. Study 2 results of moderated regression predicting physical activity intentions

The distinguishing features of Study 2 are delineated by our findings and the lack thereof. Corresponding with Study 1, we once again affirmed a positive correlation between religious identity and self-reported physical activity. However, an unexpected finding (or the absence of one) emerged in the context of the percentage of the Muslim population in the respective countries, revealing no significant impact on the aforementioned relationships. Thus, other macro-level factors might affect Muslim women’s physical activity participation in various cultures. For instance, cultural factors, such as how women’s bodies are generally perceived to be socially admissible in various societies, might impact Muslim women’s physical activity participation. For example, Hussain and Cunningham (Citation2021) have previously posited that within the cultural context of the Indian sub-continent, women often harbor the perception that engaging in vigorous sports could engender a “masculine” physique, which clashes with the prevailing societal acceptance of feminine body forms in the region. Other macro-level factors, such as physical activity facilities, divergent sociocultural norms, and the interest of local and national level government agencies in improving physical activities (Wicker et al., Citation2012), might be more relevant factors to explore in future studies.

5. General discussion

Recently, an escalating curiosity has emerged concerning the barriers Muslim women encounter when partaking in physical and sports-related activities (Laar et al., Citation2019; Nakamura, Citation2002; Pfister, Citation2010). The discourse in current scholarship outlines two opposing viewpoints regarding Muslim women’s participation in physical activities. The dominant narrative, both in academic circles and mainstream media discourse, frames Islam as a significant impediment to the engagement of the Muslim community in physical activity (see Walseth & Fasting, Citation2003). Conversely, a cohort of scholars propounds the notion that religious tenets can function as a catalyst to physical activity, as some Muslims perceive Islam as an advocate of active physical engagement (Agergaard, Citation2016; Samie, Citation2013). To elucidate these contrasting paradigms, we executed two comprehensive studies involving Muslim women from diverse global regions engaging in physical activities. The findings indicate that Muslim women with robust religious identities exhibit higher intentions towards physical activity. Hence, the deeper the connection that Muslim women establish with Islam, the more they perceive their religious beliefs as a reflection of their identity and the more inclined they are towards physical exertion. However, their determination to involve themselves in physical activities may be contingent upon the degree of participatory freedom accorded to them by their respective societies.

Consistent with the multilevel approach to sport and physical activity (Cunningham, Citation2019; Golden & Earp, Citation2012), we examined individual- and societal-level factors that might influence these patterns. In Study 1, we found that the relationship between physical activity participation and religious identity is moderated by Muslim women’s level of health consciousness (i.e., an individual-level factor). These results are in accordance with previous studies regarding the role of health consciousness in shaping people’s attitudes toward health-related activities (Bukhari et al., Citation2019; Hong & Chung, Citation2022; Pu et al., Citation2021). In Study 2, we examined the potential influence of religiously similar others in the country (i.e., a macro-level factor). We found that overall, larger factors, such as the Muslim population, might not impact Muslim women’s physical activity participation.

Overall, the results suggest that (a) Muslim women differ in the extent to which their religious beliefs are an important part of their personal identity; (b) the influence of Muslim women’s religious identity on their physical activity intentions varies based on their health consciousness; and (c) the link between religious identity and physical activity intentions is consistent across contexts. Together, the results demonstrate the heterogeneity of Muslim women, their views, and their behaviors. Thus, rather than generalizing Muslim women’s experiences, it is important to focus on sociocultural forces affecting Muslim women’s physical activity participation in a certain context (Samie, Citation2013; Toffoletti & Palmer, Citation2015).

6. Limitations and future research

While our research presents numerous significant insights, our studies have inherent limitations. Primarily, the data for Study 1 was collected via the Amazon Mechanical Turk portal. The credibility of data sourced from this platform has been a subject of contention among researchers, casting a shadow of doubt over its reliability and validity. Various scholars, however, have offered best practice recommendations to assuage these concerns (Young & Young, Citation2019), and we followed this guidance in our study. Second, in our Study 1, participants had higher education levels than the general Muslim women population across the globe. Therefore, future data should be collected from Muslim women with diverse demographic backgrounds.

Third, in Study 2, we collected data from various online communities (e.g., Reddit) and social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) platforms. However, we recognize that some Muslim women might not have access to these forums or the Internet; thus, the findings are likely most relevant to women with access to the Internet and social media. Future researchers could explore whether such access (e.g., social media) influences religious identity or physical activity. Lastly, as mentioned previously, the Muslim world is diverse, and the Muslim community belongs to different sects (e.g., Shia and Sunni); our study does not consider sectarian differences. Hence, in the future, various sects can be taken as a moderator to test this study’s results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Umer Hussain

Umer Hussain is an Assistant Professor at Wilkes University, PA, USA. His areas of research include exploring the intersection of race, religion, and gender in sports. Hussain has more than nine years of experience in academia and practice. Hussain has published numerous scholarly journal articles and presented his research at many academic conferences globally. His Ph.D. dissertation was awarded as the Distinguished Dissertation in Social Sciences category for 2021-22 by Texas A&M University, USA.

George B. Cunningham

George B. Cunningham is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Sport Management. He is also director of the Laboratory for Diversity in Sport. His research focus is on diversity and inclusion in sport and physical activity. He has published over 200 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters and has authored an award-winning book (Diversity in Sport Organizations). He is a two-time President of the North American Society for Sport Management and is a member of the National Academy of Kinesiology.

References

- Agergaard, S. (2016). Religious culture as a barrier? A counter-narrative of Danish Muslim girls’ participation in sports. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 8(2), 213–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1121914

- Aguinis, H., Villamor, I., & Ramani, R. S. (2020). Mturk research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 47(4), 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320969787

- Ahadzadeh, A. S., Sharif, S. P., & Ong, F. S. (2018). Online health information seeking among women: The moderating role of health consciousness. Online Information Review, 42(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-02-2016-0066

- Ahmad, N., Thorpe, H., Richards, J., & Marfell, A. (2020). Building cultural diversity in sport: A critical dialogue with Muslim women and sports facilitators. International Journal of Sport Policy & Politics, 12(4), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1827006

- Bidzan-Bluma, I., & Lipowski, M. (2018). Physical activity and cognitive functioning of children: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040800

- Bozionelos, G., & Bennett, P. (1999). The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of exercise: The moderating influence of beliefs and personality variables. Journal of Health Psychology, 4(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539900400406

- Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001

- Bukhari, S. F. H., Woodside, F. M., Hassan, R., Shaikh, A. L., Hussain, S., & Mazhar, W. (2019). Is religiosity an important consideration in Muslim consumer behavior: Exploratory study in the context of western imported food in Pakistan. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(4), 1288–1307. https://doi.org/10.1108/jima-01-2018-0006

- Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory. Oxford University Press.

- Calzo, J. P., Roberts, A. L., Corliss, H. L., Blood, E. A., Kroshus, E., & Austin, S. B. (2014). Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12–22 years old: Roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9570-y

- Chu, J., Pink, S. L., & Willer, R. (2021). Religious identity cues increase vaccination intentions and trust in medical experts among American Christians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(49), e2106481118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2106481118

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Cunningham, G. B. (2010). The influence of religious personal identity on the relationships among religious dissimilarity, value dissimilarity, and job satisfaction. Social Justice Research, 23(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-010-0109-0

- Cunningham, G. B. (2019). Diversity and inclusion in sport organizations. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429504310

- Cunningham, G. B., & Ahn, N. Y. (2019). Moderation in sport management research: Room for growth. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 23(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2018.1472095

- Edwards, M. B., & Cunningham, G. (2013). Examining the associations of perceived community racism with self-reported physical activity levels and health among older racial minority adults. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 10(7), 932–939. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.10.7.932

- Eigenschenk, B., Thomann, A., McClure, M., Davies, L. E., Gregory, M., Dettweiler, U., & Inglés, E. (2019). Benefits of outdoor sports for society. A systematic literature review and reflections on evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060937

- Ek, S. (2015). Gender differences in health information behaviour: A Finnish population-based survey. Health Promotion International, 30(3), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat063

- Ellison, C. G., Fang, Q., Flannelly, K. J., & Steckler, R. A. (2013). Spiritual struggles and mental health: Exploring the moderating effects of religious identity. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 23(3), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2012.759868

- Elshahat, S., & Newbold, K. B. (2021). Physical activity participation among Arab immigrants and refugees in Western societies: A scoping review. Preventive Medicine Reports, 22, 101365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101365

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Gelinas, L., Pierce, R., Winkler, S., Cohen, I. G., Lynch, H. F., & Bierer, B. E. (2017). Using social media as a research recruitment tool: Ethical issues and recommendations. The American Journal of Bioethics, 17(3), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2016.1276644

- Golden, S. D., & Earp, J. A. L. (2012). Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior, 39(3), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111418634

- Gordon-Larsen, P., Nelson, M. C., Page, P., & Popkin, B. M. (2006). Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics, 117(2), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0058

- Gould, S. J. (1988). Consumer attitudes toward health and health care: A differential perspective. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 22(1), 96–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1988.tb00215.x

- Gould, S. J. (1990). Health consciousness and health behavior: The application of a new health consciousness scale. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 6(4), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(18)31009-2

- Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods, 48(1), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process Analysis: A regression-based approach (Methodology in the Social Sciences) (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Héliot, Y., Gleibs, I. H., Coyle, A., Rousseau, D. M., & Rojon, C. (2020). Religious identity in the workplace: A systematic review, research agenda, and practical implications. Human Resource Management, 59(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21983

- Hong, H., & Chung, W. (2022). Integrating health consciousness, self-efficacy, and habituation into the attitude-intention-behavior relationship for physical activity in college students. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 27(5), 965–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1822533

- Howard, J. A. (2000). Social psychology of identities. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.367

- Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D. G., & Newman, T. B. (2013). Designing cross-sectional and cohort studies (4th ed. ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW).

- Hussain, U., & Cunningham, G. B. (2021). ‘These are “our” sports’: Kabaddi and Kho-Kho women athletes from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(7), 1051–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220968111

- Huston, S. L., Evenson, K. R., Bors, P., & Gizlice, Z. (2003). Neighborhood environment, access to places for activity, and leisure-time physical activity in a diverse North Carolina population. American Journal of Health Promotion, 18(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.58

- Kahan, D. (2015). Adult physical inactivity prevalence in the Muslim world: Analysis of 38 countries. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2014.12.007

- Kari, J. T., Pehkonen, J., Hirvensalo, M., Yang, X., Hutri-Kähönen, N., Raitakari, O. T., Tammelin, T. H., & Harezlak, J. (2015). Income and physical activity among adults: Evidence from self-reported and pedometer-based physical activity measurements. PloS One, 10(8), e0135651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135651

- Knez, K., Macdonald, D., & Abbott, R. (2012). Challenging stereotypes: Muslim girls talk about physical activity, physical education and sport. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 3(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2012.700691

- Koinig, I. (2021). On the influence of message/audience specifics and message appeal type on message empowerment: The Austrian case of COVID-19 health risk messages. Health Communication, 37(13), 1682–1693. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1913822

- Laar, R. A., Shi, S., & Ashraf, M. A. (2019). Participation of Pakistani female students in physical activities: Religious, cultural, and socioeconomic factors. Religions, 10(11), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110617

- Ladd, K. L. (2007). Religiosity, the need for structure, death attitudes, and funeral preferences. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 10(5), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670600903064

- Lipka, M. (2017, August 9). Muslims and Islam: Key findings in the US and around the world. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/09/muslims-and-islam-key-findings-in-the-u-s-and-around-the-world/

- Li, C., Zayed, K., Muazzam, A., Li, M., Cheng, J., & Chen, A. (2015). Motives for exercise in undergraduate Muslim women and men in Oman and Pakistan compared to the United States. Sex Roles, 72(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0435-z

- Lopez, V. (2019). No Latina girls allowed: Gender-based teasing within school sports and physical activity contexts. Youth & Society, 51(3), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X18767772

- Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292183006

- Mason, C. W., McHugh, T.-L. F., Strachan, L., & Boule, K. (2019). Urban indigenous youth perspectives on access to physical activity programmes in Canada. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1514321

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. University of Chicago Press.

- Mercer, A., Caporaso, A., Cantor, D., & Townsend, R. (2015). How much gets you how much? Monetary incentives and response rates in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 79(1), 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu059

- Nakamura, Y. (2002). Beyond the hijab: Female Muslims and physical activity. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 11(2), 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.11.2.21

- Noh, Y.-E., & Shahdan, S. (2020). A systematic review of religion/spirituality and sport: A psychological perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 46, 101603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101603

- Payne, B. K., Vuletich, H. A., & Lundberg, K. B. (2017). The bias of crowds: How implicit bias bridges personal and systemic prejudice. Psychological Inquiry, 28(4), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2017.1335568

- Pfister, G. (2010). Outsiders: Muslim women and olympic games – barriers and opportunities. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 27(16–18), 2925–2957. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2010.508291

- Phalet, K., Fleischmann, F., & Hillekens, J. (2018). Religious identity and acculturation of immigrant minority youth: Toward a contextual and developmental approach. European Psychologist, 23(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000309

- Puciato, D., Rozpara, M., Mynarski, W., Oleśniewicz, P., Markiewicz-Patkowska, J., & Dębska, M. (2018). Physical activity of working-age people in view of their income status. BioMed Research International, 2018, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8298527

- Pu, B., Du, F., Zhang, L., & Qiu, Y. (2021). Subjective knowledge and health consciousness influences on health tourism intention after the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2021.1903181

- Pu, B., Zhang, L., Tang, Z., & Qiu, Y. (2020). The relationship between health consciousness and home-based exercise in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165693

- Randel, A. E., & Jaussi, K. S. (2003). Functional background identity, diversity, and individual performance in cross-functional teams. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 763–774. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040667

- Rodger, A., & Papies, E. K. (2022). “I don’t just drink water for the sake of it”: Understanding the influence of value, reward, self-identity and early life on water drinking behaviour. Food Quality and Preference, 99, 104576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104576

- Rubio‐Rico, L., de Molina‐Fernández, I., Font‐Jiménez, I., & Roca‐Biosca, A. (2021). Meanings and practices of the physical activity engaged in by Moroccan women in an Islamic urban environment: A quasi‐ethnography. Nursing Open, 8(5), 2801–2812. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.857

- Samie, S. F. (2013). Hetero-sexy self/body work and basketball: The invisible sporting women of British Pakistani Muslim heritage. South Asian Popular Culture, 11(3), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2013.820480

- Sechrist, J., Suitor, J. J., Vargas, N., & Pillemer, K. (2010). The role of perceived religious similarity in the quality of mother-child relations in later life: Differences within families and between races. Research on Aging, 33(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027510384711

- Sharara, E., Akik, C., Ghattas, H., & Makhlouf Obermeyer, C. (2018). Physical inactivity, gender and culture in Arab countries: A systematic assessment of the literature. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5472-z

- Shimoda, A., Hayashi, H., Sussman, D., Nansai, K., Fukuba, I., Kawachi, I., & Kondo, N. (2020). Our health, our planet: A cross-sectional analysis on the association between health consciousness and pro-environmental behavior among health professionals. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 30(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2019.1572871

- Smith, N. A., Sabat, I. E., Martinez, L. R., Weaver, K., & Xu, S. (2015). A convenient solution: Using MTurk to sample from hard-to-reach populations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.29

- Stalling, I., Albrecht, B. M., Foettinger, L., Recke, C., & Bammann, K. (2022). Associations between socioeconomic status and physical activity among older adults: Cross-sectional results from the outdoor active study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03075-7

- Stryker, S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Benjamin Cummings.

- Summers, J., Hassan, R., Ong, D., & Hossain, M. (2018). Australian Muslim women and fitness choices – myths debunked. Journal of Services Marketing, 32(5), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-07-2017-0261

- Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

- Tajfel, H. (1979). Individuals and groups in social psychology*. The British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 18(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1979.tb00324.x

- Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Taylor, W. C., Floyd, M. F., Whitt-Glover, M. C., & Brooks, J. (2007). Environmental justice: A framework for collaboration between the public health and parks and recreation fields to study disparities in physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 4(s1), S50–S63. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.4.s1.s50

- Toffoletti, K., & Palmer, C. (2015). New approaches for studies of Muslim women and sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(2), 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215589326

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reichter, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell.

- Upenieks, L., Uecker, J. E., & Schafer, M. H. (2021). Couple religiosity and well-being among older adults in the United States. Journal of Aging and Health, 34(2), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/08982643211042159

- Walseth, K. (2006). Young Muslim women and sport: The impact of identity work. Leisure Studies, 25(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360500200722

- Walseth, K., & Fasting, K. (2003). Islam’s view on physical activity and sport: Egyptian women interpreting Islam. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 38(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690203038001727

- Warburton, D. E. R., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2017). Health benefits of physical activity. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 32(5), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1097/hco.0000000000000437

- Warburton, D. E. R., Nicol, C. W., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(6), 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351

- Wicker, P., Hallmann, K., & Breuer, C. (2012). Micro and macro level determinants of sport participation. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 2(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426781211207665

- Young, J., & Young, K. M. (2019). Don’t get lost in the crowd: Best practices for using Amazon’s Mechanical turk in behavioral research. Journal of the Midwest Association for Information Systems (JMWAIS), 2019(2), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.17705/3jmwa.000050