Abstract

Certain kinds of bereavement are associated with cultural centers in Israel, known as “Yad-Labanim” (translated as “Memorial to the Sons”). The Yad Labanim organization is considered globally unique, as it aims to serve both as a commemorative institution and a hub for heritage studies. It provides everyday activities that are not always directly linked to bereavement. In this context, sadness and joy coexist, and grief finds expression through architecture and art oeuvres.This research elaborates on how architecture engages with memories, history, and perpetuation and how the environment can contribute to the unique atmosphere. The research emphasizes the relationships between architecture and Israeli society and explores the role of architecture in creating a national identity and the design of national consciousness. The exploration of Yad Labanim centers focuses on branches where public libraries are operated and examines the correlation between the centers’ two main functions: the memorial hall and the library. The research indicates the shift that has occurred in the approach to commemoration in Israeli society over the years, revealing that coping with grief has become increasingly embraced and widely acknowledged.

1. Bereavement in Israeli society

Bereavement-related buildings in Israel, known as Yad Labanim (translated “A Memorial to the Sons”), share unique qualities connecting Israeli war casualties and memorial buildings. These community centers are considered unique to Israel and support bereaved families and coordinate daily activities. The awareness of Israeli society passes through memories of the wars embodied in these types of buildings. These centers often include libraries as an everyday public function. Libraries in Israel are responsible for preserving the evidence of the different streams in the Zionist Movement and Jewish Heritage. Thus, bereavement is always present, and these libraries are part of the commemorative project, using architectural means to memorialize the casualties of wars.

Bereavement-related community centers can be found in different types of settlements in Israel, from small communities or kibbutzim (collective settlements) to large citiesFootnote1; Hence, the perpetuation can be related at any level (Bar-On, Citation1989). The project commenced before the establishment of the State of Israel, as the Yishuv (pre-state settlements) settlers dealt with frequent struggles, and the commemoration assisted in raising the morale of the settlers. Apart from monuments, statues, and places designated for commemoration, the Yad Labanim libraries’ advantage is that they provide a space that allows lingering for an extended time as the building is not entirely dedicated to commemoration and, therefore, more accessible to a diverse audience.

The Yad Labanim libraries emphasize collective memory through various physical and visual arts, as well as their contribution to the deepening of commemoration through books. It is important to note that this research primarily focuses on Yad Labanim branches, where public libraries operate as part of everyday community activities. Activities are offered to the community and the public, including live performances, art galleries, and workshops. Therefore, the libraries can initiate activities and content, not necessarily related to or dependent on bereavement. Hence, this paper aims to examine how bereavement and memories are manifested in the unique architectural design of these buildings. By analyzing elements that interact with grief, we can explore the connection between these libraries and the national characteristics of Israel. The research demonstrates how the memory of Israeli casualties holds a significant place in Israeli history and can be conveyed through monuments and elements found in Yad Labanim centers. Therefore, the research asserts that these places serve as mediators, agents, or components in the perpetuation of Israeli war casualties, while also providing a means to connect visitors to the broader history of Israel over time.

2. The Zionist-Israeli perpetuation

Perpetuation is a social-cultural process related to collective public memory composed of two complementary aspects regarding a semiotic process: integrating ingredients from the past within social communication and marking these ingredients significant for a community (Schwartz, Citation1982). The commemoration as a political act is part of a regime’s ideology, with different levels of public perpetuation, from the symbolic ceremonial to everyday commemoration (Azaryahu, Citation1993, p. 98). Commemoration does not attempt to present an all-encompassing truth or justify myths. Instead, the creation of unity often involves the integration of historical memories into everyday life. Furthermore, it relies on the sense of pride associated with belonging to a specific group, which extends beyond mere national heritage (Azaryahu, Citation1993, p. 125). Thus, perpetuation is realized by both physical monuments and by textual perpetuation, toponymy, literature, and ceremonies.

The concern for the perpetuation of modern societies engages theorists who approach the concept of collective memory from various perspectives. This concept serves the need to trace a society’s history and document its trajectory of perpetuation, transitioning from individual to shared memories within society. Collective memory is established through the exchange of information, the adoption of shared identities, and the documentation processes that shape both present and future recollections (Shefi, Citation2012, p. 171). It is motivated by agents that fashion and spread stories and myths. Yoav Gelber defines them as “collective memory designers” (Gelber, Citation2007, p. 308).

Pierre Nora delves into a discussion of communities or societies that document themselves out of social distress should they cease to exist. Nora claims that interest in places of memory (lieux de mémoire) can be considered as compensation for the loss of authentic embedded memory (milieux de mémoire) (Nora, Citation1989). Modern progress hurls the present into the abyss of the past, as affected by irreversible logical consequences (Lorenz et al., Citation2013).

Bereavement in Israel has become an inherent issue, touching the lives of many Israelis who have experienced the loss of someone dear or have empathized with their community. The collective memory of Israel encompasses diverse ethnic groups, reflecting the mosaic-like nature of Israeli society. In the 1950s, as the young State of Israel emerged, there was a need to cultivate “memory agents” who actively worked, driven by national, political, or social motivations, to perpetuate and establish a distinct, recognizable narrative. At times, this shared narrative may vary or be manipulated to construct a unified canon. The uniform indoctrination of political and military legacies in Israel underwent a shift in the 1980s, leading to a more pronounced diversity of opinions and a range of analytical perspectives that contribute to identity politics (Naveh, Citation2017, p. 76).

There are important Israeli researchers who adopt an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating insights from sociology, anthropology, psychology, and cultural studies. Through their work, they contribute to the understanding of memory and cultural processes in Israeli society. For instance, Maoz Azaryahu, in his book “Upon Their Demise,” presents various approaches through which architects sought to express the ideas, cultures, and unique directives they represent (Azaryahu, Citation2012). Yael Zerubavel examines how societies construct, maintain, and transmit memory, investigating the diverse interpretations and narratives of historical events (Zerubavel, Citation1995). Michael Feige explored the motivations and narratives of those involved in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and examined the impact of identity, memory, and collective trauma on political attitudes and behaviors. His writings also address topics such as nationalism, social movements, and the impact of violence on societies (Feige, Citation2009). Vered Vinitzky Seroussi’s research explores various aspects of Israeli society, including culture, memory, collective narratives, and national identity. Her work examines the intersection of politics, culture, and social dynamics in Israeli society (Olick et al., Citation2011).

2.1. Memorial monuments in the Jewish world

The language of memorial buildings, monuments and commemoration sites passes through the desire to express mourning and grief visually. The discourse of monuments evolved before the mid-20th century, elaborated mainly by Louis Mumford, Siegfried Giedion and Cecil Eliot (Elliott, Citation1964; Giedion, Citation1944, pp. 549–86). It refers to the modern movement and the purpose of efficiency in construction and good use of materials.

The monuments discourse related to the Jewish world refers to the remembrance of individuals, which is a reasonably new phenomenon aside from the consciousness of collective Israeli-Zionist memory (Stanislawski, Citation2004). Ancient Jewish communities cultivated this tradition over centuries, adapting it to different times and places (Barkay & Schiller, Citation2005, p. 134). Perpetuation serves as a tool to aid memory processes. Eyal Naveh argues that the Zionist project employs selective historical narratives to construct a truthful narrative that serves the Zionist Movement. In the pre-state era, there existed a contrast between the settlers in Mandatory Palestine and the Jewish diaspora. The debate was rooted in the ancient religious stage that characterizes Jewish tradition. While rebelling against the passive aspects of Jewish tradition, the Zionist movement embraced its core as a cultural mechanism. They regarded Jewish tradition as a foundation of collective memory to identify with, creating significant modern symbols and contributing to the cultural richness encompassing the diaspora Jewry’s diverse traditions (Naveh, p. 234).

2.2. Memorial monuments in Israel

Monuments in Israel were established following significant events, most of them to commemorate war battles, especially from the British Mandate through the Holocaust, and heroism themes to various casualties such as road accidents. The first monuments in Palestine served to establish the new society and were erected during the 1930s. The monuments cherished collective memories and commemorated those who had fought for the nation (Efrat, Citation2005, p. 462).

One of the main catalysts of perpetuation through monuments was the impact of the Holocaust on the memorial discourse in Israel (Rotenshtrich-Belberg, Citation1999). Before the establishment of the State of Israel, Holocaust memorials were not as prevalent. The recognition and commemoration of the Holocaust took different forms. The pioneers who arrived in the early 20th century left their homes, language and culture in Europe and started a psychological process of coming to terms with the situation of abandonment. The guilty feelings for families left behind during the Holocaust accelerated the foundation of monuments (Liebman & Don-Yehiya, Citation1984). In some cases, memorials were established in the aftermath of World War II, while in others, commemorative events and ceremonies served as the primary means of remembrance. Holocaust survivors and Jewish communities often organized gatherings and memorial services to honor the victims and ensure that the atrocities committed during the Holocaust were not forgotten. However, the construction of dedicated Holocaust memorial sites, such as the Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, became more widespread after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. These memorials serve as significant symbols of remembrance and education, preserving the memory of the Holocaust for future generations (Oz, Citation1992).

The erection of the monuments expresses a message related to memories and commemorations and serves as an educational affiliation by combining issues related to culture and heritage. It can be argued that monuments shape memory by visualization as well as ritual means that address the intangible side of memory and allow for a different kind of experience. Oz Almog argues that a monument for the victims of wars is both a tool for local commemoration and a significant pedagogical tool in the ideological mechanism created by Israeli society, which seeks to convey a message of commitment to society and the country by commemorating the fallen perpetrators of the “ultimate” patriotic act of giving life (Almog, Citation1992, p. 50).

Approximately 1500 commemorative memorials for fallen soldiers in Israeli wars have been erected since the late 19th century. Gabriel Barkai categorizes these monuments into different commemorative elements. Out of all the monuments in Israel, only around 30% are genuine sculptures, 10% are environmental elements, and the remaining consist of walls bearing the names of the fallen, large rocks, and memorial pillars. (Barkay & Schiller, p. 134)

After Israel’s War of Independence in 1949, the issue of memory shaping was considered a first-class question (Kolb & Shamir, Citation1996, p. 41). Protocols of the Central Competitions Committee of the Engineers and Architects Association between January 1949 and January 1951 reveal that almost all competitions were concerned with monuments and memorial sites. (Efrat, p.461) In 1949 the Soldier’s Commemoration Department was established concerning the law for planning military cemeteries. Also, in early 1951 David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s prime minister, convened a public committee to determine the nature of commemorating the fallen soldiers of Israel, which at its first meeting discussed the setting of National Memorial Day.Footnote2

2.3. The shift in approach to commemoration

Since the establishment of the state of Israel, significant political, social, and cultural transformations have occurred, shaping the nation’s identity and defining its characteristics and attitudes towards commemoration. Political parties and various institutions have worked towards building a robust political system, education networks and the public sector, all while grappling with security challenges and internal difficulties. Israel has experienced shifts in political voices and social divisions during different periods.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the mass immigration of immigrants and their incorporation into a new Israeli citizenry posed numerous challenges, including the implementation of an austerity policy and the management of tensions arising from the immigration and integration of various cultural groups.Footnote3 This immigration and integration led to tensions among Israel’s different cultures and raised aspirations to create a melting pot, which eventually failed (Nitzan-Shiftan, Citation2005).

In the 1960s, there was a shift in the discourse surrounding commemorative art. Local artists were influenced by global developments such as Pop Art and the anti-war movements. These artists increasingly focused on anti-heroism rather than heroism. For instance, figurative monuments transitioned from Nathan Rapaport’s depiction of heroic soldiers at Kibbutz Negba to David Polus’s poignant representation of a mother embracing her children at Kibbutz Ramat Rachel (Bar-Or & Yasky, Citation2010, p. 78).

During the 1970s and 1980s, Israel witnessed political changes marked by the rise of various political movements. Following the Six-Day War in 1967 and the resulting sense of euphoria, significant differences in lifestyle and the discourse surrounding architecture and art became evident. Architecture shifted from modest modernist buildings tailored to the economy to more expressive and ostentatious designs. Budgets and objectives increasingly prioritized the development of public buildings, including numerous libraries, thanks to increased funding. These changes in architecture and development directly manifested from the early 1970s until the parliamentary election of 1977 (Bernstein & Swirski, Citation1982). In 1977, the Likud Party won over The Labor Party and brought about a more conservative and nationalist approach to governance. Following those years, the government’s influence shifted towards pursuing a privatization policy instead of unification.

This period also saw significant changes in societal attitudes and practices surrounding mourning and bereavement. Three notable shifts in commemoration emerged during this time. First, there was a greater emphasis on commemorating individuals and their memories, recognizing the importance of providing support and resources for those experiencing grief. Second, new voices and an expanded understanding of Israeli history and memory emerged in society and public consciousness, revealing a more diverse and fragmented Israeli society. Lastly, there was an increased emphasis on identifying and accepting grief openly in the public sphere, focusing on acknowledging the experiences of marginalized groups within Israeli society.

2.4. Architecture recruited for the memory

Monuments attempt to define a mythical story in a permanent space; therefore, the architecture is recruited to guarantee the intention of the respective place. A structure built to commemorate death poses unique architectural challenges and highlights different perceptions and their expression in architecture (Heathcote, Citation1999). Gideon Ofrat asserts that a monument does not aim for dialectic interpretation, but to create a straightforward, accessible, unified commemoration, using fewer interpretations or metaphors; i.e., it is vital to create an unambiguity of action, time, and place and to be communicative for different audiences (Ofrat, Citation1982, p. 308).

Architecture can be regarded as an agent of memory in certain aspects. Throughout history, buildings’ representations and meanings have changed; building readability, as a transmitted quality, can be interpreted differently at different times.

The discourse of monument planning in Israel is a consequence of the Jewish dilemma of the commandment: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,”Footnote4 prevalent since the establishment of the state. The monuments exhibit a range of morphologies, from concrete figurative forms that depict the human figure and sacred social values, to abstract designs that aim for timeless and universal symbolism. The prevalence of abstract monuments increased notably after the Six-Day War in 1967.

2.4.1. Architectural monuments in Israel privatizing the perpetuation

The approach to perpetuation became fragmented as a result of the political agenda of privatization, which impacted various aspects of life, including the economy, social dynamics, and cultural affairs. This trend intensified following the Six-Day War, (1967) and more so after the Yom Kippur War (1973); the solidity and unification regarding institutional and national aspects of the country became more privatized and personalized. The perpetuation started focusing on individuals instead of communal or collective memories (Baumel-Schwartz, Citation2009).

It can be argued that architectural historians strive to analyze monuments within the context of collective memory. They examine how visitors’ prior experiences shape their interpretation of the monument’s message. However, this analysis may not always resonate with those who are unfamiliar with architectural symbolism, potentially leading to a misinterpretation of the monument’s meaning. To comprehensively examine these monuments and buildings, interdisciplinary studies that integrate architectural design with psychological, social, and cultural aspects should be employed.

3. The architecture of Yad Labanim libraries

Yad Labanim is a unique organization dedicated to perpetuating soldiers who lost their lives during their army services and organizing activities for bereaved families. The organization evokes the dilemma affiliated with nationality and the gap between the individual and the general public, which are eventually embodied in the building differently. Establishing a perpetuation institute was a bottom-up process, as a private or local enterprise, with the inspiration of becoming a national institution.

The idea was initiated in response to a letter sent to the press in December 1948 at the end of the War of Independence. The letter was written by Dr. Shapira, a mother whose son had been killed in the war.Footnote5 Shapira aspired to encourage the bereaved families, especially the mothers, to commemorate and reach for the families and draw them inside the circle of mourning. Her goal was to establish a center comprising memories of the casualties while revealing their stories through memorable items. Items that refer to both physical and intangible remembrance “both in stone and in spirit.” (Rozenson, Citation2009, p. 284) That is, make the place both a spiritual and a cultural center.

The first branch was established in Petach Tikva in 1951 by Miriam Shapira and the bereaved mothers who initiated the organization.Footnote6 The building combines both community and cultural centers with a designated place for a memorial. It contains an exhibition hall, archive, and memorial hall.Footnote7 The complex was an opening shot and served as a prototype for subsequent buildings to be evolved as fusing between the lively community center and the memorial place. The second complex, built in Hadera and inaugurated in 1955, contained the first Yad Labanim library. Over the years, 60 branches have been established, for example, Tel Aviv in 1962, Rishon LeZion in 1965, and mainly during the 1980s, more branches were opened in Netanya, Beersheba, Ramat Hasharon, and in the Druze town of Daliyat-el-Carmel in 1983. Today the Yad Labanim organization has more than 70 branches in Israel. The buildings are used as community centers for everyday activities and are considered accessible and inviting while also serving as a place of bereavement. These serve as executive branches of the organization, used as agencies in charge of commemoration and remembrance, welfare, and rehabilitation, which can be executed in communication with the public. Each branch is subordinate to the municipality and can therefore emphasize its placeness and local awareness. (Rozenson, p. 280)

The educational concept is sometimes hidden while offering a path to observe memories that are not always related directly to the visitors but accentuate the collective. The organization arranges different daily independent activities related to commemoration. These spaces are open to the public, serving both as a means to acquire knowledge and as destinations for private visits, thereby fostering a unified community that brings life to the surroundings. For instance, the Yad Labanim architectural competition program for the city of Nesher in 2010 emphasized the significance of incorporating everyday activities while also creating a designated space for mourning, stating, “Remember, the place should function in everyday life, while once a year there is a ceremony” (Riba, Citation2020).

Yad Labanim buildings, as lieux de mémoire, are intricately linked to history and memory in their physical, symbolic, and functional aspects. They serve as documentary and archival resources, preserving the collective memory. Additionally, the organization focuses on educating youth and the community about values such as heroism and volunteering while also providing suitable cultural activities.

Lieux de mémoire is defined as the same action or activity in the building, such as Memorial Day, battle heritage storytelling, commemoration ceremonies, and physical monuments. That said, multiple aggregations of knowledge and physical objects in a defined hierarchy from individual to general, assemble the fractions into a whole gestalt of commemoration. The narratives that are told in Yad Labanim are sometimes embellished and not accurate enough to glorify a figure or a battle. The visitors are not exposed to the whole plot, and the resulting image can be misleading (Naveh, Citation2005).

In all the Yad Labanim branches, a specific library is dedicated to commemorating the casualties with memorial books and personal information for each soldier. In some branches, public libraries are operated, serving the local public. Planning this library permits visitors not related directly to bereavement to come in contact with the commemoration. The acts of visiting, reading and experiencing those public libraries eventually create an affinity between the memorial and the public.

There are recurring elements in each Yad Labanim building, unifying the memorial heritage, spaces with names of the casualties, and private commemoration. A memory from the religious quotes of verses from the Bible or at the national level by quoting famous Israeli poets. Since the 1950s, designated Yad Labanim buildings have become a unique type of building in the Israeli landscape mainly because of the unification between commemoration and everyday activities. The examination includes different aspects of Yad Labanim libraries as commemoration elements and their relation to the local atmosphere, eventually influencing interior and exterior experiences. The research aims to elaborate on how architecture engages with memories, history, and perpetuation, i.e., how architecture can generate an environment of commemoration, contribute to the unique atmosphere, and influence its location within the urban context. Obviously, there is a uniqueness in Yad Labanim libraries compared to public libraries, although both address the same audience. Therefore, Yad Labanim’s architectural examination is done through the lens of the library as a function, among other functions.

Yad Labanim libraries to be investigated in this discussion are the branches in Tel Aviv (1960–1965) by architects Israel Lotan and Tzvi Toren; Ra’anana (1972–1976) by architect Avraham Tamir; Ramat Hasharon (1985) by architect Liat Preiss; Haifa (1990) by architect Giora Gur; Hod Hasharon (1993) by architect Liat Preiss. The outcome of the discussion is manifested in two case studies the Yad Labanim Kfar Saba (1963–1976) by architects Arie Elhanani and Nisan Cna’an; and Kiryat Tiv’on Library and memorial center (1987) by architect Israel Hochberg. Important to note that There are also libraries related to memorial centers in different settlements in the kibbutzim and moshavim. However, this research is focused mainly on libraries and Yad Labanim buildings in cities and urban settlements.

The overall architecture of Yad Labanim libraries is, therefore, a combination of various elements that are emphasized and, at times, unique to each building. These elements aim to establish a connection between visitors and the experience of grief. The following section of the paper elaborates on different aspects: the morphology of the library as a monumental perpetuation, the arrangement of the memorial hall and its effect on visitors, the connection and coexistence between the library and the memorial hall, and the elements of perpetuation that encompass the building and captivate the visitors.

3.1. The library monumental perpetuation morphology

A building’s morphology creates a ceremonial impact transmitting an extrovert message that influences the visitor even before entering the building. This strengthens the experience of a semi-sacred place through the sight and other senses as a phenomenological experience. Both building morphology and size enable us to examine the meanings behind the design, whether the purpose is to glorify the building as a monument or to dissolve it with the surroundings modestly.

Over the years, changes in designing these buildings were primarily expressed in morphology and complexity rather than size and volume. This form was acceptable because the main functions did not expand over the years despite the growth of the population; however, lack of funding did not justify larger buildings. Hence, what triggered the local design shift was the global architectural discourse. At first, Yad Labanim buildings were planned according to Brutalist principles, with their facades mostly composed of exposed concrete, such as Yad Labanim in Petach-Tikva, Kfar Saba and Tel Aviv. Over the years, shifts in the architectural discourse to post-modernism or deconstructivism, especially during the 1980s, espoused more complexity. Most of Yad Labanim’s buildings were then covered with chiseled stone, providing an impressive and honorable image.

The expression of monumentalism is manifested at the Ra’anana building. A monumental appearance of four floors covered with stone, with small square windows arranged in two rows. The entrance from the north is between two vast masses of east- and west-inclined walls (Figure ). The building is situated on the main street in front of a sizable plaza; thus, one can grasp the whole building’s form, which produces an effect of a fortress-like building. Another morphological complexity is the Hod Hasharon library. The building can be interpreted as an enormous segment of a round tent supported by concrete beams. The entrance is between two immense walls abutting the ceremonial walk axis to the entrance (Figure ).

In contrast to Ra’anana, the Haifa and Ramat Hasharon branches dissolve within their surroundings due to their size and location within an urban fabric. Both buildings are covered with stone and have two floors above ground. In Haifa, the building is located at the lower end of Hanadiv Boulevard, while the entrance is placed as a continuous virtual extension of the boulevard (Figure ). The entrance divides the façade into two semi-symmetrical sides between perpendicular walls. Entering the building goes through a glass wall shaped like a cone, referring to the monument inside. Ramat Hasharon is also situated inside a neighborhood as a stand-alone public building. The morphology is assembled of masses of different heights ascending from the entrance. The main facade was partially covered in 2011 with brown metal plates for the theater on the first floor.Footnote8 Hence, the change in the façade decreased the readability of the building by adding a different material (Figure ). The impact is created by the first impression, together with the accessible and inviting yet intriguing entrance, which influences the building’s readability and appreciation of its monumental characteristics. Over the years, visual conception had changed according to international architecture discourse, from modernism to postmodernism and the expression of shapes. As will be shown, not only the mass and size dictate the monumentality but the building’s expressionist morphology.

3.2. The memorial hall

All Yad Labanim branches or memorialization buildings have a memorial hall usually located at the core of the building. The halls are meant to be disconnected from their surroundings and other functions, both physically and conceptually. This isolation creates a unique atmosphere of seclusion, a timeless space where one can concentrate on the scene of a “sacred” memorial place. The hall holds symbolic meanings related to national commemoration and fostering unity among citizens through the use of familiar symbols. Additionally, it serves as a means to remember each casualty’s individual perpetuation as an integral part of the community.

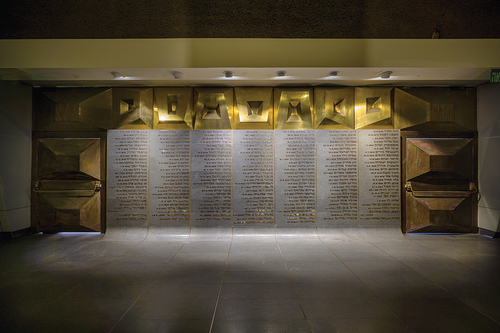

Each hall has recurring elements, making it common in terms of a collective bereavement connotation. Familiar associative texts from the Bible or written by famous poets are presented on the walls, such as the word Yizkor (remember), which always appears in different places in these buildings. The mystical meaning of the number 12 is also part of the Jewish consciousness for the number of the biblical tribes, the number of the months, the zodiac, etc. (Azaryahu, p. 100) Therefore, in each hall, the number 12 can appear in different contexts, as 12 great columns in the Tel Aviv or 12 wooded-golden pipes at the entrance of the Hod Hasharon hall (Figure ). Another feature lists all the stamped names of the casualties, usually carved on stones, as a hard earthen substance. Names are arranged chronically according to the date of death, especially for wars (Figures ). The list may be considered a mediator between the collective assembly of war casualties and individual commemoration by mentioning each name. The halls are, therefore, live archives of the casualties, telling their stories in words, pictures and symbols. The front wall of the hall in Ramat Hasharon is adorned with the engraved names of the casualties, and a monitor displays their names and pictures. In addition, a multimedia system is available for searching and locating specific names. Also, a small room attached to the hall contains files dedicated to each casualty, with personal stories aggregated in drawers.

Figure 5. Yad-Labanim Hod-Hasharon: the entrance to the memorial hall with 12 pipes; photo: author, 2022.

The barrel vault ceiling of Ra’anana memorial hall is discerned from the outside as the only spot of the overall composition with curved geometry. Regarding its volume, the monumental hall is three stories high, with windows only in the upper part below the vault. The entrance to the hall is from above, and a long staircase takes the visitor to the floor below. In the center, a metal column, shaped like an extrusion of the Star of David, cut into two pieces with a red Plexiglas cylinder inside, designed by Ilana Gur. (Figure ).

The Hod Hasharon memorial hall has different commemoration elements, such as a cupboard with drawers for each casualty for private commemoration where all the families can archive important objects.Footnote9 The drawers represent unity through their equal shape and sizes; every visitor can access these drawers that introduce the soldier (Figure ).

The vastest halls in proportion to population size are in Haifa and Tel Aviv. In Tel Aviv, the large rectangular plan is almost empty except for glass vitrines that stand in the middle of the space. The strength of the hall is manifested neither in decorative elements nor statues or paintings but by its emptiness and the names of the casualties dispersed on the walls. Haifa memorial hall is octagonal, with a monument at the center composed of two pyramids penetrating each other. The lower pyramid is made of black stone, the same as the floor tiles, and the upper one is coated with bronze plates (Figure ).

3.3. The symbiosis between the library and the memorial hall

At Yad Labanim libraries, there is an interaction between the two main functions—the library and the memorial hall. The sense of commemoration is presence in these buildings mainly through their physical components. However, the main function of the building is to commemorate, even though in some of the Yad Labanim branches, the library functions as the municipal central library. Each building takes a different approach to integrating both functions. Hence the metaphoric symbiosis strengthens the relationship between the library’s public uses and the commemorative representation of the memorial.

In most places, the foyer implies the location of the memorial hall. Apart from signposts, well-planned architectural elements can direct visitors; therefore, visual contact is done by architectural means. In both Haifa and Hod Hasharon the memorial hall is located opposite the entrance facing the foyer whereas the library is located at the side of the entrance (Figure ). In Haifa, the library is located on the second floor, facing the memorial hall double-height space from above (Figure ). In Ramat Hasharon the memorial hall is located on the lower floor below the entrance. A path leading to the library passes between two holes in the floor, providing a glimpse of the memorial hall underneath (Figure ). The entrance to Tel Aviv Yad Labanim goes through a long path alongside a tall wall that penetrates the building below the solid flat roof (Figure ). The path divides the interior square plan into two sections. The more extensive section, two-thirds of the space, is dedicated to commemoration and the assembly hall. The small northern section contains the offices and the library.

Figure 12. Yad-Labanim Hod Hasharon: ground floor plan; drawn by the author, based on historic drawings.

3.4. Elements of Perpetuation Encompassing the Building

Elements surrounding the building assist in the readability of its purposes. An acquaintance is created between the passers-by and the building, even without visiting the interior. These elements are intentional decoration and collective commemoration symbols related to community and nationality that create a sense of identity and belonging.

The Hod Hasharon building is surrounded by a large park and the entrance is through a path located between two memorial hubs that contain monuments. The memorial monuments are built of rough stones with engraved quotations of poets and Biblical verses that refer to the national consciousness of perpetuation (Figure ). In Ramat Hasharon, this attitude was realized by presenting “the unity of the land of Israel.” The geologist Akiva Flexer and the landscape architect Gideon Sarig planned a garden composed of stones transported from different places in Israel (Figure ) (Lisovsky & Alon-Mozes, Citation2017, p. 10).

Figure 16. Yad-Labanim Hod Hasharon: memorial hub with Yad Labanim in the background; photo: author, 2017.

There are also connections between the local vegetation and its uses around memorial places, especially Yad Labanim. At most branches, the building is juxtaposed with a park or garden. In Tel Aviv, the garden was designed by Avraham Karavan in 1964. Karavan emphasizes the building’s solitude, first by artificially flattening the topography of the kurkar sandstone mound and using local vegetation that isolates the building; however, it assists in exposing the building step-by-step as it is being approached (Moria & Barnir, Citation2003, pp. 248–50).

4. Experiencing memoire and preserving the heritage through everyday activities

Memorial buildings are used for the perpetuation of both collective and individual memories. In Israeli society, these buildings are examples of mixed-use as they commemorate while providing everyday activities even without a direct connection between the visitors and bereavement. Yad Labanim libraries were established as public buildings mainly in the center of settlements, to strengthen the bond between the bereaved families and their local community’s heritage. These libraries enable individual visits to experience the commemoration and enable annual ceremonies for the whole community. Their memorial characteristics are distinguished from other public buildings and other libraries.

4.1. Locality and everyday life: Yad Labanim as Lieux de Mémoire

Yad Labanim buildings are important for integrating perpetuation and commemoration related to the history of the place as part of the collective national existence. Architecture serves as a platform representing local history by means of different media such as texts, pictures and illustrations. The main concept transmitted is a collective education of contribution for “working the land” and “defending the land.” Therefore, the library building serves as a lieux de mémoire integrating past and present, individual and collective historical narratives of wars and individual heroic stories. The narrative is embodied through different items that are presented in the space not necessarily related to bereavement. For example, the Ra’anana branch hosts the Founders House (Beit Rishonim), and at the entrance to the library in Hod Hasharon, pictures of past mayors of the city are hung, along with important figures who contributed to the community.

Architect Liat Preiss, who was involved in designing three Yad Labanim library buildings in Hod Hasharon, Ramat Hasharon and Savyon, claims a different perception of commemoration in each place. However, all are composed of three primary elements: the commemoration, the library, and an events hall.

There is a debate as to whether the library is the primary function that contains the Yad Labanim or whether the Yad Labanim center contains a library as an inferior function. Hence, the importance of public participation in processes related to commemoration and community. For example, the mayor of Hod Hasharon, Ezra Binyamini, gathered the settlers in a tent where the building was designated to be built and asked for their opinions and desires regarding the building’s functions collaboration of the library and commemoration.Footnote10

4.2. Law practice perspective and the code of conduct

Even though the Yad Labanim organization was initialized in 1948, the Yad Labanim Law was only passed in 2007. The law details the uses and the purpose of regularizing the management of the branches within the local authorities. The law also defines the kinds of activities that may take place: memorialization, documentation, and preservation of the memoirs of the casualties.Footnote11 Thus, each place perpetuates the individual through the collective society up to national commemoration, with characteristics common to each branch. The law also defines that the municipality is responsible for funding the construction and management of the building. Therefore, the municipalities are adding more local content related to regional perpetuation.

Besides the purpose of perpetuating and maintaining the place and keeping it vivid throughout the year, various activities are held as in any community center. The building may host live performances, art galleries, workshops, and even comedy shows. Therefore, the libraries can initiate activities and content, not necessarily related to or dependent on bereavement. The individual operation of the library regarding activities of gaining knowledge through books or art exhibitions is not dependent on other facilities.

The combination of a place both for expressing bereavement and as a community center, with Yad Labanim libraries serving as sites for various activities, raises ethical questions concerning the code of conduct appropriate in a place of commemoration. The code of conduct is indeed related to a society’s cultural roots, as Israel has tried to follow Western-European culture since the British Mandate and throughout the first decades after its establishment.Footnote12 The emphasis of the perpetuation usually appears outside the memorial hall, embodied in the building’s morphology and through statues, paintings, and other artworks. The code of conduct is therefore influenced by the representation and functional arrangement of the building. Activities take place beside the commemoration and bereavement that have always existed even beyond the consciousness of the visitors.

The code of conduct in Israel is unique due to the sharp transitions between sorrow and joy, which reflect Israeli social life. Periods of daily terror attacks, wars, and battles showcase both the resilience of society, and the feeling of helplessness that, despite everything, prevents sinking into grief and encourages the continuation of everyday life. One of the most fundamental debates is about the Independence Day celebrations that are held immediately after visiting cemeteries on Memorial Day. This argument on the question of the proximity between the two days emerges every year.Footnote13 The expression of this social atmosphere is reflected at Yad Labanim in the contiguity between the spaces dedicated to perpetuation, the memorial hall, and the spaces for everyday activities and the library. Architectural planning and design elements, that combine sadness and joy side-by-side, are perceived as normal in Israeli society. By manipulating the spatial interior arrangement, the architecture can give the visitor the impression that they can control their exposure to bereavement while visiting the library.

Another matter related to placeness and knowledge is the embodiment of the books’ context related to history and memory. The library has the political strength to aggregate knowledge and spread it. Thus, the Yad Labanim libraries emphasize commemoration more than other libraries, especially on Memorial Days, when books related to fallen soldiers or stories that describe the wars are promoted to the front shelves. Therefore, Yad Labanim libraries, as lieux de mémoire, reflect both the casualties’ static memory and the library intellectually enables access to a different kind of knowledge aggregate complementary for both individual and collective.

4.3. The gaze and experiencing representation of the bereavement

The terminology of tlaw details the uses and the purf culture as a reflexive relation between two observers or between one observer and another. The gaze concerns how one is being seen and relates to inherent cultural perspective and spatial organization. The interpretation of the gaze aims to emphasize its importance at Yad Labanim libraries, enhancing the library’s experience and overall functions as part of the commemoration. Therefore, the gaze is the dialectic between the imaginary and the symbolic, as eventually is realized in Yad Labanim by architectural means.

The architectural gaze may be interpreted as a mediator between architectural language, as a signifier, and the perception of symbols as the signified. Thus, the architectural manipulation of the space causes uncanny feelings. In Yad Labanim, the impact of the gaze is interpreted in reference to bereavement. The visitors may believe they are in control of the eye’s gaze; however, any feeling of scopophilic power is always undone because the materiality of existence consistently exceeds and undercuts the meaning of structures of the symbolic order. The symbolic order is separated only by a fragile border from the materiality of the real, as the different perspectives of gaze may change the picture.Footnote14 (Lacan, Citation1977)

Regarding Yad Labanim, bereavement is always present; the gaze is a dual action between the visitor-observer and the monument. The architectural creation can impose a guided gaze, as a manipulative perspective of the space and focal point are enhanced. Therefore, a connection between the visitors and the commemoration elements occurs while questioning the exposure that enables moments of contemplation concerning the experience of this particular space.

Each Yad Labanim library has a different level of exposure to bereavement, starting from the exterior and continuing along with the foyer while observing elements and components related to commemoration. Therefore, planning the foyer of the building requires connectivity between the functions. In other words, between the libraries that provide everyday activity and the elements of commemoration. The design of the foyer and the overall building can transmit different references through its architecture by its volumes, light and shadow and glances towards focal points. These elements direct the visitor’s gaze consciously or unconsciously to a certain level of commemoration, even if the primary purpose of the visit is to use the library services. Hence, as appears in Yad Labanim buildings, the accumulation of knowledge is affected by the atmosphere of the surroundings. In Yad Labanim libraries, the presence of bereavement is conceived individually and subjectively.

For example, at Hod Hasharon, the entrance goes through a colonnade where the sunlight penetrates the building from the ceiling. The memorial hall is located at the end of the colonnade and is observed from the entrance at the end of the vanishing point (the interior was designed by Itzhak Shmueli). Entering the library in Ramat Hasharon goes through elements shaped as teardrops hanging from the ceiling by threads that reach the lower floor below through voids in the floor (created by the artist Dan Reisner). In this case, the memorial hall’s location is indicated and avoidably seen in every entrance to the library.

5. The shift in approaches to commemoration at Yad Labanim centers

Two libraries related to commemoration and present different approaches associate and accommodate the function of the library and a municipal center of bereavement. In both places, the library functions as the central library of the settlement. The two buildings were inaugurated in different decades, the Kfar Saba building in 1976 and Kiryat Tiv’on in 1987. Therefore, different approaches associate the function of the library and a municipal center of bereavement. Mainly dominance shifts occur related to the memorial hall. In Kfar Saba, all building functions are separated, while the tendency during the 1980s and later was to correlate between the library and commemoration. That is, bereavement is always a presence in the building.

5.1. Yad Labanim Kfar Saba

The library was designed as part of a complex comprising a concert hall, memorial hall, exhibition area and the central library of Kfar Saba. The complex was planned by architects Arie Elhanani and Nissan Cna’an. The complex is located adjacent to the main artery, which runs along the city center in front of the plaza’s buildings facing the main entrance to the concert hall from the east. The residents saw the importance of establishing a landmark that hosts and commemorates the history and heritage of the settlement as part of the history of Israel.Footnote15

The complex of Yad Labanim was built as part of a cultural center for the city, including a civic center and municipal museum (Beit Sapir). The Yad Labanim building has two floors. The most significant part of the ground level serves the concert hall and its facilities. Also, on the ground floor, the memorial hall is located on the northeast façade, the administration on the northwest facade, and the staircase leading to the library on the northwest side of the floor. On the second floor, the library’s L-shaped plan is located on the west and north façades (Figure ).

Figure 17. Yad-Labanim Kfar Saba: ground and first floor plans; drawn by the author, based on historic drawings.

The planning provides a separate independent operation for each function. Therefore, each function has a separate entrance, although one can traverse through the interior. As described in the journal Tvai, the functions are separated and do not “disturb” each other.Footnote16 Nevertheless, a question can be raised regarding the dimensions of the functions and their importance. The concert hall is the primary function as all other inferior functions are on a minor scale and thus are located on the rear façades. Although the library and the memorial hall entrances are both located on the north façade, there is no visual contact between them (Figure ).

Figure 18. Yad-Labanim Kfar Saba: North façade, entrance to the memorial hall on the left and to the library on the right; photo; author, 2022.

Brutalism is expressed as was familiar of the construction period; the building is a rectangle shape and is based on a tartan-grid by a division of nine squares by eight with each square’s side six meters (20 feet) long. The main east façade is primarily translucent with a division of columns that follows the grid of the plan and appears on the façade.Footnote17 The exposed concrete columns support the prominent roof emphasizing both the vertical construction and the horizontal line of the building (Figure ). The horizontal division in the vitrine at the main façade reflects the division into the two floors. The other façades are more sealed than the main façade; they are divided into the same grid with windows on the upper part and sides of each square.

The library on the second floor occupies a third of the floor’s area, about 500 m2 (5380 ft2). It contains a reading room, a stack, and a lecture hall. The library was planned as a closed-shelve system with all the books stored in the stack. The entrance to the library can be considered demoralizing due to its location on the rear façade, and second, entering the library requires climbing stairs to the second floor, which distances the visitors from the library’s entrance.

Several artworks in the building refer to the history of Kfar Saba and the perpetuation of the casualties of war who had grown up in the city. The main art piece is the memorial hall with its components, designed by Roda Reilinger between 1968 and 1973 (Figure ).Footnote18 The memorial hall is an oblong plan, 18 by 12 meters (26X40 feet) and almost four meters (13 feet) high. The space dimensions feel somewhat smaller because of the dark hue of the walls and ceiling. The main art piece is the great steel wall, composed of 12 heavy rough, distorted black metal plates, representing the powerful and impenetrable armor allegoric to Israel as a nation, as interpreted by the artist himself. On the other walls, the names of the casualties are recorded under the title of the war. There are five heavy wooden stands with information in the middle: memorial pages about the casualties arranged chronologically in ring binders.

Another important piece of artwork is located on the north side of the main east façade. An aluminum cast relief sculpture by the artist Naftali Bezem named The Holders of the Light dedicated to the residents of Kfar Saba, its builders, fighters, and defenders, as a theme through which the artist dealt with the fight for independence.Footnote19 A water garden reflects the sculpture and distances the observer from the façade, enabling them to grasp the entire art piece (Figure ).

Figure 21. Yad-Labanim Kfar Saba: Naftali Bezem’s oeuvre—“the Holders of the Light”; photo: author, 2022.

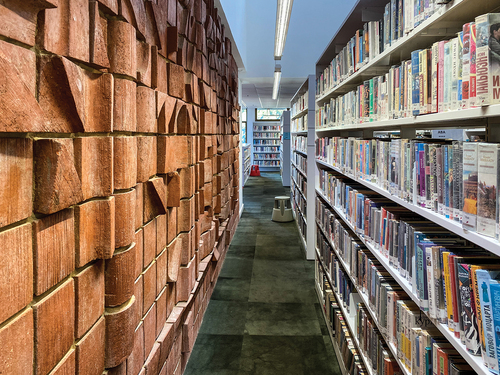

Two wall artworks are in the library; both communicate with the history of Israel and commemoration of past canonical events, even with their abstract visualization. The first is an abstract glazed tile wall created by the artist Eva Kaufman.Footnote20 This artwork is attached to the south wall of the patio encircled by the library. The wall appears as one enters the building and gives a feeling of climbing the stairs which lead to the library (Figure ). The second artwork is a sculptured red brick wall in the interior reading room created by Moshe Saidi (Figure ). The collaboration between architects and artists is of course not unique to Israel; however, the phenomenon was incredibly dominant in Israel during the 1960s-1970s.Footnote21 Moreover, these works of art are not stand-alone items but define architectural space; hence, they represent the characteristics of the local culture and history of the built environment.

5.2. Kiryat Tiv’on library and memorial center

The library building in Kiryat Tiv’on was inaugurated in 1987, more than a decade after the Kfar Saba library was opened to the public. The idea of establishing the building was evolved by local bereaved families a year after the Yom Kippur War, in which 21 local soldiers died, in addition to casualties from previous wars and attacks. The families, supporters, and the mayor of Kiryat Tiv’on, Dov Patishi, had the vision of creating a lively cultural center for all ages, with the library as the primary function of the building.Footnote22

The Kiryat Tiv’on board selected architect Israel Hochberg to plan the library and a memorial center, as part of the cultural center, including a community center, auditorium and sports facilities. The center was located in a vast area in the center of the town.Footnote23 The cornerstone for the library was set in 1982, nine years after the Yom Kippur War, after the acquisition of the funds with the assistance of the Jewish Agency and local public donations.Footnote24 The inauguration of the memorial center in 1987 took place when Kiryat Tiv’on celebrated50 years since its establishment.

Before establishing the building, a massive memorial monument was erected in 1973, together with a memorial garden, Gan HaBanim (The Garden of the Sons) (Figure ). The monument was designed by architect Chilik Arad in 1971, an enormous metal structure, 18 meters high (60 feet), is a blow-up of the “Czech hedgehog,” a static anti-tank obstacle composed of three beams leaning onto each other. The anti-tank obstacle refers to the phrase “Ad Kan” (up to here), meaning enough with the wars. The library, memorial center, and plaza are located on a hill juxtaposed to the road between Nazareth and Haifa, which crosses two former independent local councils, Kiryat Amal (1936) and Tiv’on (1940) that became a united authority in 1958. The gesture of establishing the monument symbolized the merger of the towns creating a gathering place for Memorial Day ceremonies for the whole community.

Figure 24. Kiryat Tiv’on memorial center: general planning; drawn by the author, based on historic drawings.

The library building has two floors above ground and a large basement with a shelter built in front of the building (Figure ). The library was built in two phases due to lack of funds; the second floor was realized in 1996, almost a decade after the building’s inauguration. The rhombus shape plan of the ground floor contains the main functions that appear as two masses in the roof plan. The library is located on the east and south sides; the north and west sides are exhibition and convention halls. Both functions wrap around the core of the building where the memorial hall is located. Between the two masses, a wide corridor encircles the memorial hall, which is almost constantly in sight so that the plan of the building can be interpreted as layers of a circle (Figure ). The outer layer, the library and the exhibition hall are considered the “layer of knowledge and culture,” the middle layer is used for circulation and represents liveliness and mobility. The memorial hall, which is the living heart of the building and the most important function, is at the core.

Figure 25. Kiryat Tiv’on memorial center: ground floor plan; drawn by the author, based on historic drawings.

Figure 26. Kiryat Tiv’on memorial center: view of the memorial hall from the entrance, the library (left); photo: author, 2021.

The small scale of the memorial hall allows hosting only a few people at a time, compared to other halls, which can host a dozen or more at the same time. The hall is 25 m2 (260 ft2) in a hexagon-shaped plan (Figure ). The envelope comprises six exposed concrete walls inclined inwards, creating a trimmed cone volume, two floors high. Each hexagon corner is trimmed with glass and the transparency enables a glimpse of the library interior. Inside the hall, daylight penetrates from the ceiling as well as between the segments of the hexagon. Thus, the intention was to create a representative “sacred hall” as a connotation for an ancient temple.

The memorial hall is visible when entering the building and from both the library and the exhibition hall. Moreover, part of the library’s internal walls are translucent glass, and the memorial hall is visible from the reading room. In addition to the memorial hall, pictures of the casualties are hung on the back wall of the reading room and translucent glass separates between the reading room and the memorial hall on the side. Thus, bereavement is always present within the building. However, the library provides different activities for the public that are not directly related to bereavement.

The two memorial centers in Kfar Saba and Kiryat Tiv’on represent distinct approaches to the relationship between the library and the memorial hall. In Kfar Saba, the functions are separated, with different entrances for each. As a result, the commemoration is subtly suggested through symbols outside the building, while the bereavement function is implicitly conveyed. In contrast, in Kiryat Tiv’on, the library surrounds and envelops the memorial hall, making the perpetuation a constant presence. This change in approach can be attributed to a shifting societal attitude that has become more accepting of the recognition that commemoration and bereavement are integral parts of life. In other libraries as well, the memorial hall is no longer excluded but has become an integrated part of the overall plan. Architecture, therefore, plays a significant role and bears great responsibility in creating these relationships between the functions of the buildings.

6. Summary: architectural commemoration and heritage

Commemoration processes are established at both the national level by official institutions and privately, driven by the desire to perpetuate a narrative associated with collective memory. In Yad Labanim, the physical buildings are established by local authorities, while the content is shaped by individuals and society. Memory agents play a role in shaping memory through personal stories, visual elements such as photographs, and the creation of monuments.

Architecture adds another dimension to commemoration by utilizing various elements such as the building’s location, design, interior circulation, and memorial features. In Yad Labanim centers, architecture plays a crucial role in integrating bereavement and everyday life, particularly in libraries that facilitate activities for both groups and individuals. Its purpose is to create a synthesis that harmoniously blends commemoration with the routines of daily life.

The presence of grief exists at different levels of visibility. When analyzing the morphological perspective, noticeable differences between the various buildings indicate that the architects were permitted to act freely in designing these centers. The outcomes reflect distinct approaches regarding the monumentality and visibility of the buildings. These buildings communicate a sense of collectivity through unique commemorative artifacts, aiming to evoke connotations of national consciousness and hegemony. The commemorative artifacts establish a shared element of symbolic abstraction that is unpretentious and accessible to diverse audiences of various ages.

The two main functions in Yad Labanim buildings that were examined are the library with its facilities and the memorial hall. Both functions are dichotomously complementary to each other. The library represents and symbolizes the living and the familiarity, whereas the memorial hall represents death and bereavement. Both aim to commemorate in different ways through knowledge and symbols. Each memorial hall contains repetitive elements with chronologically arranged names of the casualties, while the hall is separated from its surroundings enabling peaceful seclusion. The commemoration refers to both individual stories and national narratives, the perpetuation of the strength, fortitude, sacrifice, and resilience of the society.

This change in commemoration and the integration between the two functions indicates the shift that has occurred in Israeli society in confronting and coping with bereavement. The Israeli perspective on commemoration has transitioned from repression to externalization since the days when Zionism served as a surrogate for religion. This shift is evident in the examined libraries over time. In the initial Yad Labanim branches, where libraries were often secluded from the memorial hall (e.g., in Ra’anana and Kfar Saba). Later, the memorial hall design became a more prominent part of the overall plan and was more exposed to visitors, as seen in Hod Hasharon, Ramat Hasharon, Haifa, and Kiryat Tiv’on. As a result, Yad Labanim memorial centers serve as mediators, agents, or components in the chain of perpetuating the memory of Israeli war casualties, while also providing visitors with a means of connecting to the history and heritage of Israel.

Acknowledgments

Liat Preiss, Danny Lotan, Illana Leshem and Kiryat Tiv’on memorial center staff

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Letzter

Architect Jonathan Letzter (Ph.D). A trained architect specializes in historic building conservation and Brutalist architecture. Master and Ph.D. at Tel Aviv University; postdoctoral studies/visiting scholar at Columbia University, New York. Researcher at Azrieli Architectural Archive, professor assistant at Tel Aviv University and participates in curating exhibitions at Tel Aviv Museum of Art and Tel Aviv University. Field of research: architectural theory, philosophy, practice and design; historical and 20th-century architecture; architecture related cultural heritage, society and politics. Awarded by Azrieli Fellows Program for both Master studies (2014-16) and Ph.D. studies (2017-2022); Won the Dan David Prize for young researchers (2020-21). www.jletzter.com

Notes

1. Community centers were established in Muslim and Druze settlements. However, this paper focuses on places with a Jewish majority due to unique characteristics and traditions.

2. “Israel Defense Force & Defense Establishment Archives”, http://www.mod.gov.il/Memorial_Legacy/remembering_the_fallen/Pages/default.aspx.

3. For instance, the Canaanites movement emerged during this time, advocating for a distinct Israeli identity inspired by the ancient Canaanite civilization, and seeking to dissociate from Jewish religious and historical traditions.

4. Book of Deuteronomy 4:13.

5. The letter was published in several newspapers: Davar 28.12.48, HaAretz 19.12.48, Dvar HaPo’a lot (23.11.48).

6. Yad Labanim Petach-Tikva, https://petah-tikva.gal-ed.co.il/Web/He/YadLebanim/Default.aspx

7. The building was planned by architects Andre (Bundi) Leitersdorf and Iliya Belzitsman.

8. Building’s Permit: architect Roni Zeibert, 1.2.2011, Ramat Hasharon Engineering Administration archive.

9. Interview with architect Liat Preiss, 24.4.2018.

10. Liat Preiss (Architect of the building), in discussion with the author, April 2018.

11. “Yad Labanim Law, 2007”, http://main.knesset.gov.il/Activity/Legislation/Laws/Pages/LawPrimary.aspx?t=lawlaws&st=lawlaws&lawitemid=2000138.

12. Before the establishment of the state, the European immigrants effected the local culture, which proceed after the establishment while the eastern culture of Jewish immigrants from Arabic countries was Pushed to the margins and did not gain recognition, only years later. For example, see: Elihu Katz and Hed Sela, “Beracha Report: Cultural Policy in Israel” (Heb.) (Jerusalem: The Van Leer Institute, 1999).

13. An Israeli Perspective: Israeli Memorial and Independence Day: https://reformjudaism.org/jewish-holidays/yom-hazikaron-yom-haatzmaut/israeli-perspective-israeli-memorial-and-independence-day

14. Lacan interprets the symbols of power and desire in Holbein’s painting (Lacan, Citation1977).

15. The history of Kfar-Saba is described in several books, articles, as well as the conservation plan for the city made by Amnon Bar or Architects office and the city meetings protocols. History of Kfar-Saba (Angel, Citation1973; Giladi, Citation2011).

16. “Yad Labanim Kfar Saba”, Tvai 18 (1978): 29.

17. Historical pictures of the building: The Jewish National Fund, Judaica Division, Widener Library JPCDKKL13614, olvwork502395, Harvard Library Archive.

18. Roda Reilinger in the Information center for Israeli art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem: https://museum.imj.org.il/artcenter/newsite/en/?artist=Reilinger,%20Roda

19. Naftali Bezem in the Information center for Israeli art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Naftali Bezem: https://museum.imj.org.il/artcenter/newsite/en/?artist=Bezem,%20Naftali&list=B.

20. The color of the piece reminds another work of the artist at the Israeli Parliament building, at the entrance to the dining hall. Information center for Israeli art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Eva Kaufman: https://museum.imj.org.il/artcenter/newsite/en/?artist=Kaufman,%20Eva.

21. See: “Israeli Art Symposium”, Tvai 1, (1966): 57.

22. Itzhak Shani, Chairman of the association for the establishment of a Yad Library, Israel Revealed to the eye website. (2300.0036.302).

23. Kiryat Tiv’on Culture & Sport Community Center, Kiryat Tiv’on Archive.

24. Even today the operation of the library is based chiefly on volunteers and donations and the community continues to be very much involved with the maintenance of the library. see: Itzhak Shani.

References

- Almog, O. (1992). Israeli war memorials: A semiological analysis. (Heb.), Tel Aviv University.

- Angel, S. (1973). Kfar-Saba: 70 years since the founding of Kfar-Saba, 80 years since the redemption of the land. (Heb.), Kfar-Saba Municipality.

- Azaryahu, M. (1993). A tale of two cities: Commemorating the Israeli war on independence in Tel Aviv and Haifa (Heb.). Cathedra: For the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv, 68, 98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23403454

- Azaryahu, M. (2012). Upon their demise: Architecture of military cemeteries - the early years. (Heb.), Israel Ministry of Defense Publishing House.

- Barkay, G., & Schiller, E. (Eds.). (2005). The morning will rise through their blood, memory of Israel’s fallen soldiers. (Heb.), Ariel.

- Bar-On, D. (1989). The negation of the “light”’. In A. Shapira (Ed.), An individual soul in exchange for success in the struggle for national existence (Heb.) (pp. 28–38). The Kibbutz Movement Platform.

- Bar-Or, G., & Yasky, Y. (Eds.). (2010). Kibbutz: Architecture without precedents: The Israeli pavilion, the 12th international architecture exhibition, the Venice Biennial. Tel Aviv.

- Baumel-Schwartz, J. (2009). Commemoration of a memory or commemorative memory, article review (Heb.). Cathedra: For the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv, 133, 152–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23407370

- Bernstein, D., & Swirski, S. (1982). The rapid economic development of Israel and the emergence of the ethnic division of labour. The British Journal of Sociology, 33(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.2307/589337

- Efrat, Z. (2005). The object of zionism: Architecture of statehood in Israel 1948-1973. (Heb.), Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

- Elliott, C. D. (1964). Monuments and monumentality. Journal of Architectural Education, 18(4), 51–53. (1947-1974). https://doi.org/10.1080/00472239.1964.11102200

- Feige, M. (2009). Settling in the hearts: Jewish fundamentalism in the occupied territories. Wayne State University Press.

- Gelber, Y. (2007). History, memory and propaganda: The historical discipline at the beginning of the 21st century. (Heb.), Am Oved.

- Giedion, S. (1944). The need for a New monumentality, in new architecture and city planning. In P. Zucker (Ed.), A symposium (pp. 549–569). Philosophical Library.

- Giladi, D. (2011). Kfar Saba days: The village that became a city. (Heb.), Ariel.

- Heathcote, E. (1999). Monument builders: Modern architecture and death. Academy Editions.

- Kolb, E., & Shamir, I. (1996). Commemoration and remembrance: The way of Israeli society in designing memorial landscapes. (Heb.), Am Oved.

- Lacan, J. (1977). The four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis. Norton.

- Liebman, C. S., & Don-Yehiya, E. (Eds.). (1984). Religion and politics in Israel. Indiana University Press.

- Lisovsky, N., & Alon-Mozes, T. (Eds.). (2017). Gideon Sarig, garden are for people. (Heb.), A.R Publisher.

- Lorenz, C., Bevernage, B., Bevernage, B., Lorenz, C. (2013). Breaking up time. Negotiating the borders between present, past and future. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666310461

- Moria, Y., & Barnir, S. (2003). In the public domain: A tribute to Tel Aviv city gardener Avraham Karavan. (Heb.) Tel Aviv Museum of the Art.

- Naveh, E. (2005). Few against many: Reality, ethos, educational myth (Heb.). In A. Kaddish & B. Z. Kedar (Eds.), Few against the many? Studies on the balance of forces in the battles of Judas Maccabeus and Israel’s war of independence (Heb.) (pp. 183–196). Magnes.

- Naveh, E. (2017). Past in Turmoil: Debates over historical issues in Israel. (Heb.), Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

- Nitzan-Shiftan, A. (2005). Disputes in Zionist architecture: Erich Mendelsohn and the architects’ circle of Tel Aviv. In R. Kalush & T. Khatuka (Eds.), Architectural culture (pp. 201–230). Resling.

- Nora, P. (1989). Between memory and history: Les lieux de Mémoire. Representations, 26(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928520

- Ofrat, G. (1982). On the monument and the duties of the place (Heb.). Kav: Journal of Art and Literature, 4-5. 990020537570205171.

- Olick, J. K., Levy, D., & Vinitzky-Seroussi, V. (Eds.). (2011). The collective memory reader. Oxford University Press.

- Oz, I. (1992). War memorials: A semiological analysis. (Heb.), Tel Aviv University.

- Riba, N. (2020, September 8) What happens in Yad Labanim after the memorial-day. https://xnet.ynet.co.il/architecture/articles/0,14710,L-3100553,00.html

- Rotenshtrich-Belberg, E. (1999). Historiography, consciousness and memory: Educational implications. For the Memory, 34, 69–58. https://www.yadvashem.org/he/articles/general/historiography.html

- Rozenson, I. (2009). Both in spirit and stone: Yad Labanim as cultural and memorial centers (Heb.). In I. Rozenson & O. Israeli (Eds.), Might by spirit: Defence and educational philosophy in the heritage of the state of Israel (pp. 278–307). Ministry of Defence Publication.

- Schwartz, B. (1982). The social context of commemoration: A study in collective memory. Social Forces, 61(2), 376. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578232

- Shefi, N. (2012). The memory Archive: Media technologies and the struggle over memory (Heb.). In M. Chazan & U. Cohen (Eds.), Memory culture and history, essays in honor of Anita Shapira (pp. 161–180). Tel Aviv University.

- Stanislawski, M. (2004). Autobiographical Jews: Essays in Jewish self-fashioning. Washington University of Washington Press.

- Zerubavel, Y. (1995). Recovered roots: Collective memory and the making of Israeli national tradition. The University of Chicago Press.