Abstract

More than two years have passed, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is yet to be completely resolved. Campaigns on COVID-19 preventive behaviors have become crucial in tackling this issue among the public. Persuading the public to practice COVID-19 preventive behaviors remains to be a challenge. The current research aims to develop and test a model that can explain COVID-19 preventive behaviors by considering two factors: digital communication and psychological factors. This study employed a quantitative approach, wherein data were collected through an online survey. The sample consisted of 358 participants. Samples were selected using the purposive sampling method. SEM-PLS was used as an analytical tool in this study. The results of this research indicate that COVID-19 preventive behaviors are directly and positively influenced by behavioral intentions, digital media platforms, and communication exposure. Furthermore, COVID-19 preventive behaviors are indirectly influenced by perceived threat, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, awareness, knowledge, attitude, and message characteristics. Meanwhile, source credibility was proven to have neither direct nor indirect influence on COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

1. Introduction

In 2019, a new global health issue emerged, namely the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The disease is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Zewdie et al., Citation2022). The virus has become a global issue owing to its extremely high severity and rapid and expansive transmission (Aschwanden et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, Citation2020).

For more than two years, the global community has been living under the shadow of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and as of the end of 2022, COVID-19 is still not entirely over. Numerous countries and WHO have made various efforts to overcome COVID-19. One of the efforts that has been acknowledged as effective in preventing and controlling SARS-CoV-2 is to establish COVID-19 preventive behaviors in the population (Aschwanden et al., Citation2021). The WHO recommends several COVID-19 preventive behaviors, such as wearing face masks, social distancing, handwashing with soap and water, using hand sanitizer, self-isolation, avoiding spending time in crowded places, and taking a vaccine (Zewdie et al., Citation2022). Although COVID-19 preventive behaviors are needed by the public, getting them to practice COVID-19 preventive behaviors remains a challenge. In other words, it is important to improve COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

In order to improve COVID-19 preventive behaviors, health education associated with COVID-19 preventive behaviors is necessary to improve these behaviors (Bonell et al., Citation2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, health education related to COVID-19 preventive behaviors can be achieved through digital communication media, such as social media, websites, and health applications (Mheidly & Fares, Citation2020). Governments in many countries are using digital media to educate the public about COVID-19 preventive behaviors. For example, to deal with the COVID-19 problem, the Indian government conducts health education using digital communication media, such as Facebook and Twitter (Roy et al., Citation2022). This digital communication media is the main key for the Indian government in health education during the COVID-19 pandemic (Roy et al., Citation2022). In Indonesia, the Indonesian government also relies on digital communication media to educate the public on handling COVID-19, such as website (@covid19.go.id), Facebook (@lawancovid19indonesia), Instagram (@lawancovid19_id), Twitter (@lawancovid19_id), and Applications Play store (@United Against COVID-19).

Digital communication media is a revolutionary communication media capable of eliminating inequities of access to health promotion and communication (Roy et al., Citation2022). The advantages of digital communication media for educating COVID-19 preventive behaviors are as follows: (1) the media has a very large audience and extensive coverage; (2) it is popular among the public; (3) it can be used to engage in two-way communication among users; (4) it can be used at any time to the user’s liking; and (5) it can be used for virtual communication without having to meet face-to-face (Dutta & Bhattacharya, Citation2023; Mat Dawi et al., Citation2021; Wadham et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, several studies have recognized the significance of digital communication media during the COVID-19 pandemic in various contexts (e.g., Afifi et al., Citation2022; Biswas et al., Citation2022; Mahmood et al., Citation2021; Rather, Citation2021; Riady et al., Citation2022; Zanuddin et al., Citation2021).

Several studies have been conducted on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Most research on COVID-19 preventive behaviors has been conducted using psychological approaches, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Li et al., Citation2021, Aschwanden et al., Citation2022; Park & Oh, Citation2022), Health Belief Model (HBM) (Hong et al., Citation2021; Shahnazi et al., Citation2020; Zewdie et al., Citation2022), and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) (Barati et al., Citation2020; Ezati Rad et al., Citation2021; Prasetyo et al., Citation2020). Although the findings of some studies confirmed the theory used, several studies found a research result that was inconsistent with the theory (for example: Alagili & Bamashmous, Citation2021; Bronfman et al., Citation2021; Karimy et al., Citation2021; Mahindarathne, Citation2021; Mirzaei et al., Citation2021; Park & Oh, Citation2022). The inconsistent results of previous studies indicate that the COVID-19 preventive behavior model needs to be re-examined in a different context, including Indonesia.

Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of digital communication media experienced quite a significantly increased (Afifi et al., Citation2022; Kemp, Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2020). Digital media platforms have become the most widely used media by the public to obtain various types of information, including COVID-19 and health information (Patmanthara et al., Citation2019; Suwana et al., Citation2020). In Indonesia, the government has also used digital communication media to disseminate COVID-19 related health information. However, there is a lack of previous studies on COVID-19 preventive behavior models that involve psychological factors derived from TPB, PMT, and HBM and digital health communication media-related factors. In other words, it is important to conduct research on COVID-19 preventive behaviors that involve not only psychological factors, but also digital health communication media-related factors.

Regarding communication media-related factors, many researchers agree that there are two determining factors for successful communication: messages and sources (Collins et al., Citation2018; High & Young, Citation2018; Le et al., Citation2018). These factors have also been applied to health communication (Bakti et al., Citation2021; Fico & Lagoe, Citation2018). Communication exposure is another key factor that can affect a person’s behavior (Alrababa’h et al., Citation2022; den Hamer & Konijn, Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2016). Health communication exposure can also improve health behaviors (Luo et al., Citation2020; Melki et al., Citation2022; Mesch et al., Citation2022).

According to the previous explanation, to fill the gaps in the literature, the objective of this research is to study COVID-19 preventive behaviors by involving not only psychological factors derived from TPB, PMT, and HBM, but also digital health communication media-related factors. More specifically, this study aims to develop and test a COVID-19 preventive behavior model by involving awareness, knowledge, attitude, behavioral intention, perceived behavioral control (PBC), subjective norm, perceived threat, health communication exposure, source credibility, message characteristics, and digital health communication media platforms. The integration of psychological factors and communication media-related factors can be carried out considering that various previous studies have also integrated these factors in different contexts (e.g., Nguyen & Le, Citation2021; Riady et al., Citation2022; Rivas et al., Citation2021; Xin et al., Citation2021).

This research objective needs to be achieved because this research was needed theoretically and practically. Theoretically, this research filled a research gap that has not been done by previous studies. This research was able to empirically explain the COVID-19 prevention behaviors by involving psychological factors and digital health communication media-related factors. Practically, the government and other health education related parties can use this research model as a guide in carrying out a health education program about COVID-19 prevention behaviors. In other words, the research results can assist the government and other health education related parties in mitigating the risk of COVID-19 pandemic through an appropriate health education strategy.

2. Literature review and conceptual model

2.1. Covid 19 preventive behavior

Preventive behavior is defined as “any behavior that people engage in spontaneously or can be induced to perform with the intention of alleviating the impact of potential risks and hazards in their environment” (Kirscht, Citation1983). In the context of health, preventive behavior can be defined as “any behavior that according to professional medical and scientific standards, prevents disease or disability and/or detects disease in asymptomatic stage, and which is voluntarily undertaken by a person who believes himself to be healthy” (Langlie, Citation1979). Based on the definitions above, this study defined COVID-19 preventive behaviors as measures that can be undertaken by individuals to prevent the risks of COVID-19, in which the effectiveness of the measures has been recognized by health experts.

The existing literature explains that there are various measures that people can undertake to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Nguyen et al. (Citation2020) explains that COVID-19 preventive behaviors can focus on two aspects: personal and community. Personal preventive behaviors refer to measures that can be taken to avoid personally contracting the COVID-19 virus, such as physical distancing, wearing a face mask, cough etiquette, regular handwashing, use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, body temperature checks, and disinfecting mobile phones, et cetera (Nguyen et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, community preventive behaviors refer to communal measures that can be undertaken by individuals to avoid being infected by the COVID-19 virus within the community, such as avoiding meetings, large gatherings, going to the market, avoiding travel in a vehicle/bus with more than 10 persons, and not traveling outside the local area during lockdown (Nguyen et al., Citation2020).

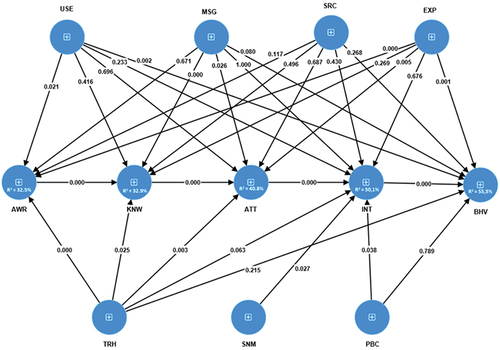

COVID-19 preventive behaviors can be explained using various theoretical approaches such as TPB (Aschwanden et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2021; Park & Oh, Citation2022), HBM (Hong et al., Citation2021; Shahnazi et al., Citation2020; Zewdie et al., Citation2022); and Hierarchy of Effect Theory/HET (Masek et al., Citation2022; Kolte et al., Citation2022). The combination of factors found in these models can provide a more comprehensive elaboration on the phenomenon of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Moreover, considering that health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic has tended to utilize digital communication media, digital communication media-related factors can provide more comprehensive explanations of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Given this, we proposed a COVID-19 preventive behavior model that involves awareness, knowledge, attitude, behavioral intention, perceived behavioral control (PBC), subjective norm, perceived threat, health communication exposure, source credibility, message characteristics, and digital health communication media platforms. Figure illustrates this conceptual model.

2.2. Behavioral intention (BI)

BI is a construct identified by the TPB. In TPB, behavioral intention can be described as a concept that represents a motivational factor that influences actual behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). This indicates a person’s readiness to engage in a particular behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). More specifically, BI can be measured by willingness to perform the behavior and plan to perform the behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Thus, in this study, BI represents a person’s motivation to engage in COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

This construct is used by the TPB to explain behavioral formation (Ajzen, Citation1991). Specifically, according to the TPB, BI positively influences behavior. In the context of COVID-19 preventive behaviors, several studies have found the positive impact of BI on COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Chen & Chen, Citation2020; Hong et al., Citation2021; Park & Oh, Citation2022; Sangeeta & Tandon, Citation2021). Thus, the first hypothesis of this study was formulated as follows:

H1:

BI influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.3. Attitude

A definition of attitude has been proposed by various researchers (Altmann, Citation2008). Ajzen (Citation1991) proposed the most popular definition of attitude. Attitude was defined as “the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question” (Ajzen, Citation1991). This definition has also been adopted in COVID-19 related studies, such as Twum et al. (Citation2021), Fenitra et al. (Citation2021), and Jain et al. (Citation2022).

According to the TPB, attitude is a significant determinant of BI (Ajzen, Citation1991). The positive impact of attitude on BI has been empirically proven in various contexts (Hasan, Citation2022; Sumaedi et al., Citation2016), including health behaviors (Astrini et al., Citation2021; Sumaedi et al., Citation2021b; Twum et al., Citation2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies also argued that attitude has a positive effect on BI of COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Ahmad et al., Citation2020; Chen & Chen, Citation2020; Fenitra et al, Citation2021; Sumaedi et al., Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Thus, the second hypothesis is as follows:

H2:

Attitude influences BI of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.4. Knowledge

Knowledge is a complex construct discussed by numerous scholars (Jiang & Rosenbloom, Citation2014). This construct reflects cognitive aspects (Duffett, Citation2020). Hosseinzadeh et al. (Citation2020) explained that knowledge is “the concept, skill, experience, and vision that provide a framework for creating, evaluating, and using information”. In the existing literature, the concept of health knowledge is specifically applied according to the examined context, such as knowledge of diseases (Jirattikorn et al., Citation2020; Khajebishak et al., Citation2021; Rajkumar & Romate, Citation2020), knowledge of oral nutrition (Aydin et al., Citation2022; Limbu et al., Citation2019; Tam et al., Citation2019), and oral health knowledge (Abu-Gharbieh et al., Citation2019; Al-Wesabi et al., Citation2019; Riad et al., Citation2022). Therefore, in this study, knowledge was examined in the context of knowledge related to COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

According to the HET, knowledge positively influences attitudes (Masek et al., Citation2022). Several empirical studies have confirmed the positive relationship between knowledge and attitudes in various contexts (Suki, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020; Xin & Seo, Citation2020), including health behaviors (Ghazali et al., Citation2017). Therefore, this research expected that knowledge would positively influence attitudes toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. The third hypothesis is as follows.

H3:

Knowledge influences attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.5. Awareness

Awareness can be defined as “the capacity to become the object of one’s own attention” (Morin, Citation2006). Awareness refers to an individual’s ability to understand and adapt to new situations (Anzanpour et al., Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2011). More briefly, awareness is “an affirmative response” to something, be it an object or a situation (Whaley-Connell et al., Citation2009).

Awareness is closely related to knowledge. Based on HET, awareness positively affects attitudes. Previous studies have shown that awareness positively influences knowledge (for example: Koohang et al., Citation2022; Mohiuddin et al., Citation2018; Zhao et al., Citation2020). Thus, this research expected that awareness would positively influence knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. The fourth hypothesis is as follows.

H4:

Awareness influences knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.6. Perceived behavior control (PBC)

The PBC is a construct identified by the TPB. PBC refers to an individual’s belief in his/her control over a behavior (Wallston, Citation2005). According to Ajzen (Citation1991), PBC can be defined as “perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior.” Furthermore, it represents the availability of resources and opportunities for an individual to perform an action (Ajzen, Citation1991). In other words, PBC describes the limits, obstacles, and struggles that occur when a person performs a behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Therefore, this study defined PBC as an individual’s perceived ease or difficulty in applying COVID-19 preventive behaviors by considering the resources one has and the opportunity to perform these behaviors.

The TPB argued that PBC has a positive impact on BI and actual behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Several empirical studies have shown that PBC is a predictor of BI (Sumaedi et al., Citation2021a). During COVID-19 pandemic, several scholars have found that PBC positively affects health behavior (e.g., Ahmad et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2021; Park & Oh, Citation2022; Twum et al., Citation2021). Thus, we expected that PBC would positively influence COVID-19 preventive behaviors and the BI for COVID-19 preventive behaviors. The fifth and sixth hypotheses of this study are formulated as follows:

H5:

Perceived behavioral control influences BI of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H6:

Perceived behavioral control influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.7. Subjective norm

Subjective norm is “the perceived social pressure to perform or not perform the behavior” (Ajzen, Citation1991). This definition has frequently been adopted by many scholars (Barbera & Ajzen, Citation2020; Twum et al., Citation2021; Sumaedi et al., Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). This definition was adopted in the present study. More clearly, subjective norm refers to an individual’s perception of social pressures from people they consider important to perform COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

TPB argues that a person’s BI can be positively influenced by subjective norms (Ajzen, Citation1991). Previous studies, such as Astrini et al. (Citation2021), Yarmen et al. (Citation2016), and Liu et al. (Citation2021), have shown the positive influence of subjective norms on BI. In the context of the COVID-19 study, the positive impact of subjective norms on the BI of health behaviors was also confirmed (e.g., Chen & Chen, Citation2020, Sumaedi et al., Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Park & Oh, Citation2022; Twum et al., Citation2021). The seventh hypothesis proposed in this study is as follows:

H7:

Subjective norm influences BI of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.8. Perceived threat of COVID-19

Perceived threat can be defined as “the anticipation of harm that is based on the cognitive appraisal of an event or cue that is capable of eliciting the individual’s stress response” (Carpenter, Citation2005). Three keywords can be used to describe perceived threats: anticipation of harm, cognitive appraisal, and stress response (Carpenter, Citation2005). In the health context, perceived threat is a construct that discusses two aspects: severity and susceptibility (Hong et al., Citation2021; Mirzaei et al., Citation2021).

Perceived threat is one of the constructs that play a crucial role in forming a person’s behavior. This has been observed in HBM (Alagili & Bamashmous, Citation2021; Hong et al., Citation2021; Mirzaei et al., Citation2021; Twum et al., Citation2021) and PTM (Barati et al., Citation2020; Ezati Rad et al., Citation2021). The positive influence of perceived threat on COVID-19 related-health behaviors has been shown by numerous researchers such as, Anaki & Sergay (Citation2021), Irigoyen-Camacho et al. (Citation2020), DeDonno et al. (Citation2022), Nguyen and Le (Citation2021) and Rayani et al. (Citation2021). The perceived threat of COVID-19 was also found by Rather (Citation2021) Wnuk et al. (Citation2020) and Anaki & Sergay (Citation2021) to have a positive influence on attitude toward COVID-19 related health behaviors. Furthermore, it may also affect knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This is because COVID-19 preventive behaviors can be categorized as risk-anticipation behaviors. Knowledge and awareness of risk-anticipation behavior are measures of risk preparedness (Nojang & Jensen, Citation2020). Empirically, perceived threats positively influence risk preparedness positively (Zheng et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth hypotheses of this study were formulated as follows:

H8:

The perceived threat of COVID-19 positively and significantly influences awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

H9:

Perceived threat of COVID-19 positively and significantly influences knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

H10:

The perceived threat of COVID-19 positively and significantly influences attitudes toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

H11:

The perceived threat of COVID-19 positively and significantly influences behavioral intention toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

H12:

Perceived threat of COVID-19 influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.9. Digital health communication media platforms (DHCMPs)

According to Boulianne and Theocharis (Citation2020), DHCMP is a communication facility, forum, or place relating to health information that relies on information technology and the Internet. Several types of DHCMP include: (1) social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, etc.), (2) mobile social networking apps (MSNs) (e.g., WhatsApp and WeChat), (3) online news media, and (4) social live streaming services (SLSSs) (e.g., YouNow and Tumblr) (Liu, Citation2020). In previous studies, many researchers viewed DMPs from the perspective of MP usage (for example (Biswas et al., Citation2022; Mahmood et al., Citation2021; Rather, Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2021)., This research adopted a similar view, which measured DHCMPs using the frequency and quantity of digital health communication media platforms used to gain information about COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

In the existing literature, digital media platforms are believed to have a significant effect on behaviour (Bedard & Tolmie, Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2016; Mcgloin & Eslami, Citation2014; Yang & Wu, Citation2019), behavioral intention (Yang & Wu, Citation2019), attitude toward behavior (Cheston et al., Citation2013; Choi & Noh, Citation2020; Lewis & Sznitman, Citation2019; Mat Dawi et al., Citation2021; Ortiz et al., Citation2018), knowledge of behavior (Cheston et al., Citation2013; Kahlor & Rosenthal, Citation2009; Ortiz et al., Citation2018), and awareness of behavior (Taddicken, Citation2013). Several COVID-19 pandemic studies have also indicated a significant effect of DHCMPs on COVID-19 related behavior (Li & Liu, Citation2020; Mahmood et al., Citation2021), attitude (Biswas et al., Citation2022; Melovic et al., Citation2020), knowledge (Wang et al., Citation2021; Xie et al., Citation2020; Yin et al., Citation2022), and awareness (Al-Dmour et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth hypotheses of this study are formulated as follows:

H13:

DHCMPs influences awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H14:

DHCMPs influences knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H15:

DHCMPs influences attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H16:

DHCMPs influences behavioral intention of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H17:

DHCMPs influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.10. Health communication exposure

Health communication exposure is a factor that needs to be considered in health education (Han & Xu, Citation2020). In communication literature, exposure is a part of the communication process that represents how often receivers receive and engage with an information message so that they respond to it (Lefevre et al., Citation2019). According to Nunez-Smith et al. (Citation2010), communication exposure covers two aspects: content (exposure from the aspect of information substance) and quantity (exposure from the aspect of the number of media). Thus, this study defined health communication exposure as how often someone receives and engages with COVID-19 preventive behavior information from a digital health communication media platform.

The existing health literature showed that health communication exposure has positive impact on health behavior (e.g., Faasse & Newby, Citation2020; Fenitra et al., Citation2021; Xin et al., Citation2021) It also empirically influences attitude toward health behavior (Rivas et al., Citation2021), knowledge of health behavior and awareness toward health behavior (Bago & Lompo, Citation2019). Therefore, this study expected health communication exposure positively influences COVID-19 Preventive behaviors, behavioral intention of COVID-19 Preventive behaviors, attitude toward COVID-19 Preventive behaviors, knowledge of COVID-19 Preventive behaviors and awareness of COVID-19 Preventive behaviors. Therefore, the eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth, twenty-first, and twenty-second hypotheses of this research are formulated as follows.

H18:

Health communication exposure influences awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H19:

Health communication exposure influences knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H20:

Health communication exposure influences attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H21:

Health communication exposure positively and significantly influences behavioral intention toward COVID-19 prevention.

H22:

Health communication exposure influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.11. Source credibility

According to Rains and Karmikel (Citation2009), source credibility can be defined as ‘‘judgements made by a perceiver concerning the believability of a communicator” (O’Keefe, Citation2016)”.” Source credibility may include judgements of the attractiveness, expertise, and trustworthiness of the message source (Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2020). Given this, this study defined source credibility as someone’s judgements of attractiveness, expertise, and trustworthiness of the message source in informing them about COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

In health communication literature, one of the factors that can influence health behavior is source credibility (Rains & Karmikel, Citation2009). Several studies have shown the positive influence of source credibility on COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Gehrau et al., Citation2021; Goldberg et al., Citation2020; Haytko et al., Citation2021; Nguyen & Le, Citation2021),; attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Conlin et al., Citation2022; Gomez-Aguinaga et al., Citation2021; Mai et al., Citation2021; Stasiuk et al., Citation2021) and COVID-19 preventive behaviors related knowledge (Vlasceanu & Coman, Citation2022). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, source credibility has also been proven to have a positive influence on health behaviors related to awareness (Hoda, Citation2016; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Therefore, the twenty-third, twenty-fourth, twenty-fifth, twenty-sixth, and twenty-seventh hypotheses are formulated as follows:

H23:

Source credibility influences awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H24:

Source credibility influences knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H25:

Source credibility influences attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H26:

Source credibility influences behavioral intention of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H27:

Source credibility influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

2.12. Message characteristics

Message characteristics represent information quality (Sumaedi et al., Citation2021b). It describes someone’s judgement of the relevancy, adequacy, accuracy, and punctuality of the message he/she received (Deng et al., Citation2015; Zhou, Citation2013). Tao et al. (Citation2017) considered message characteristics as the level of information completeness, accuracy, depth, clarity, and relevancy. Thus, this study viewed message characteristics as someone’s judgements of the information quality on COVID-19 preventive behaviors by considering various aspects, such as clarity, accuracy, relevancy, punctuality, and completeness.

Message characteristics play an important role in COVID-19 prevention. Several studies have shown that message characteristics positively influence COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Ceylan & Hayran, Citation2021) and behavioral intentions (Borah et al., Citation2021; Carfora & Catellani, Citation2021). Furthermore, empirically, message characteristics also positively influence attitudes toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Borah et al., Citation2021; Carfora & Catellani, Citation2021), knowledge, and awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors (Ezeah et al., Citation2020; Talabi et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the twenty-eighth, twenty-ninth, thirtieth, thirty-first, and thirty-second hypotheses are formulated as follows:

H28:

Message characteristics influences awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H29:

Message characteristics influences knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H30:

Message characteristics influences attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H31:

Message characteristics influences behavioral intention of COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

H32:

Message characteristics influences COVID-19 preventive behaviors positively and significantly.

3. Research method

3.1. Variables and measures

This study involved 12 research variables, namely digital health communication media platforms (DHCMPs), message characteristics, source credibility, health communication exposure, perceived threat of COVID-19, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, awareness, knowledge, attitude, behavioral intention, and COVID-19 preventive behavior. To ensure content validity, the indicators for each variable were adopted from previous human behaviour studies that discussed the relevant variable (Tari et al., Citation2007). For example, subjective norm was measured by three indicators that adapted from Astrini et al. (Citation2021), Bronfman et al. (Citation2021), and Sumaedi et al. (Citation2020; Citation2021b). More completely, Table lists the variables and indicators with the reference source. Since the indicators were adopted from diverse human behaviour literature, to ensure that the indicators are understood by respondents according to the operational definition of each variable, during the instrument development we performed wording test by asking 10 respondents whether they understood each question. They confirmed that every question in the questionnaire was understood. Indicators were assessed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely disagree) to 5 (extremely agree).

Table 1. Variables and indicators

3.2. Data collection and respondents

Owing to physical movement limitations during the COVID-19 pandemic, an online survey was used to collect data. There were 419 respondents wanted to participate voluntarily and gave informed consent for this survey. However, there were 61 respondents that can’t be analyzed further because they didn’t meet the sample criteria of this study and/or didn’t completely fill out the questionnaire. Thus, the samples of this research are 358 respondents. The number of these samples have met the sample size needed. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), the minimum sample size that must be taken in SEM is at least 5 times the number of indicators. In this study, the total of indicators used to measure 12 variables were 56 items. In other words, the minimum sample size for this study was 280 respondents. Moreover, calculating the minimum sample size can be performed by using G*Power analysis (Faul et al., Citation2009). This analysis is the best estimates the statistical power for sample size analysis (Soomro et al., Citation2023). Based on the calculation of G*Power software program (version 3), in order to achieve small effect size (Kang, Citation2021), the minimum number of samples that must be taken in this research was 178.

The sample criteria were as follows: (1) aged 17 years and above; (2) living in the Greater Jakarta area (Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi—Jabodetabek) and Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia; and (3) obtained/searched for information about COVID-19 preventive behaviors from digital media platforms (e.g., YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc.) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey involved only the residents of the Greater Jakarta area (Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi—Jabodetabek) and Yogyakarta Special Region, since these regions can be categorized as the regions with the highest rate of Internet use in Indonesia (BPS-Statistics Inodonesia, Citation2019). The respondents’ profiles are listed in Table . This research received ethical clearance from the Research Ethics Committee in Faculty of Psychology & Socio-Cultural Sciences at Universitas Islam Indonesia (No: 1365/Dek/70/DURT/VII/2022).

Table 2. Characteristics of respondents

In order to prevent potential survey bias, we have performed several procedural controls proposed by previous researchers. Based on Kock et al. (Citation2021), the source of survey bias consists of respondent related source and measurement related source. In order to mitigate the respondent related source, we didn’t ask the questions that potentially cause the social desirability bias in Indonesia, such as income, tribes, religion, race, and political preference (Conway & Lance, Citation2010). In order to mitigate the measurement related source, several actions were performed, such as performing wording test, providing clear questionnaire instructions, keeping simple and non-ambiguous survey items, concise survey length, and anonymous responses (Kock et al., Citation2021; Podsakoff et al., Citation2012) and ensuring that there is no overlap indicator for each variable (Conway & Lance, Citation2010).

3.3. Data analysis

A partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) was employed to verify the research model and test the hypotheses. Two stages of analysis were performed: a measurement model analysis and a structural model analysis. Construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests were conducted during measurement model analysis (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The software Smart PLS Version 4.0 was used to support the data analysis.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Results

4.1.1. Measurement model

Construct reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values, while convergent validity was tested using item loading and average variance extracted (AVE) values (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2010). As shown in Table , all variables have a significant item loading value, the item loading value (range 0.633–0.96) exceeds the minimum threshold of 0.6 (Hair et al., Citation2010), and the Cronbach’s alpha value (0.71–0.94) also exceeds the minimum threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2010). The CR values for all variables exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.7, and nearly all variables had an AVE greater than 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2010). The AVE value of a variable, DHCMPs, was slightly below 0.5 (AVE DHCMPs = 0.464). Previous studies claim that this condition is acceptable if other supporting indicators satisfy the standard (Lam, 2012). Based on these results, the measurement model is reliable and has convergent validity.

Table 3. Result of model constructs reliability and convergent validity Testing

The discriminant validity evaluation of all variables was performed by analyzing the square root of the AVE for each variable. The AVE square roots of the variables were compared to the correlation value of the variable against other variables. If the square roots of AVE have a greater value than the correlations with other variables, then the discriminant validity of the variable is satisfied (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). As shown in Table , the square root of the AVE (diagonal value) of each variable has a greater value than the correlations with the other variables (value below diagonal) (Hair et al., Citation2017). Another alternative to assess discriminant validity is the use of table cross loadings. Discriminant validity is met when the loading factor values of certain indicators are greater than the cross-loading values of the indicators (Hair et al., Citation2017). Table shows that the loading value of each indicator is greater than the cross-loading value among the indicators. This study also employed the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) test in addition to the discriminant validity test with AVE and cross loading. This was performed to instill confidence in the validity of the discriminant validity results. This method used a multitrait-multimethod matrix as the basis for measurement. The HTMT value must be less than 0.9 to ensure discriminant validity between the two reflective variables (Henseler et al., Citation2015). Table shows the discriminant validity test of HTMT in this study. The discriminant validity value between the two reflective variables less than 0.9, except for the relationship of two variables: behavior—awareness (0.925).

Table 4. Fornell-Larcker criterion analysis result

Table 5. Cross loading analysis result

Table 6. Discriminant validity: heterotrait-monotrait ratio Statistics (HTMT)

4.1.2. Structural model

Figure and Table present the results of the PLS analysis. Sixteen hypotheses are supported. Behavioral intention (β = 0.638, p-value < 0.05), DHCMPs (β = 0.114, p-value < 0.05), and communication exposure (β = 0.167, p-value < 0.05) had positive and significant influences on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Therefore, H1, H17, and H22 are confirmed. Attitude (β = 0.444, p-value < 0.05), perceived behavior control (β = 0.133, p-value < 0.05), and subjective norm (β = 0.155, p-value < 0.05) had positive and significant impacts on behavioral intention toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Thus, H2, H5, and H7 were confirmed. Knowledge (β = 0.385, p-value < 0.05), perceived threat of COVID-19 (β = 0.120, p-value < 0.05), communication exposure (β = 0.164, p-value < 0.05), and message characteristics (β = 0.164, p-value < 0.05) had positive and significant effects on attitudes toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Hence, H3, H10, H20, and H25 are confirmed. Awareness (β = 0.281, p-value < 0.05), perceived threat of COVID-19 (β = 0.109, p-value < 0.05), and message characteristics (β = 0.354, p-value < 0.05) were confirmed to have a positive and significant impact on knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Thus, H4, H9, and H24 are supported. Perceived threat of COVID-19 (β = 0.225, p-value < 0.05), digital media platforms (β = 0.104, p-value < 0.05), and communication exposure (β = 0.319, p-value < 0.05) had a positive and significant influence on awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Thus, H8, H13, and H18 were confirmed.

Figure 2. Empirical results of the structural path model. Value on path: p-value,R2: coefficient of determination.

Table 7. Hypothesis and path coefficients significance Testing results

4.2. Theoretical implications

To improve COVID-19 preventive behaviors, it is important to develop a model that can be used to understand COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Several researchers have developed a COVID-19 preventive behavior model. However, there is a lack of research that integrates psychological and digital health communication-related factors to understand COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This research fills this gap in the literature. More specifically, this research has developed and tested a COVID-19 preventive behavior model by considering not only psychological factors (e.g., perceived threat, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, awareness, knowledge, attitude, and behavioral intention) but also factors relating to digital health communication (e.g., platforms, message characteristics, source credibility, and exposure). This research found that digital health communication media-related factors can directly influence COVID-19 preventive behaviors. The digital health communication media-related factors can also indirectly affect COVID-19 preventive behaviors through the mediating role of psychological factors. This research has showed that digital health communication media-related factors can be integrated with psychological factors for improving COVID-19 preventive behaviors. More specifically, the explanations of the findings of this research are as follows.

This study revealed that behavioral intention, digital health communication platforms, and health communication exposure had positive, significant, and direct effects on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Perceived threat, subjective norm, PBC, awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors, knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors, attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors, and message characteristics had indirect effects on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Surprisingly, source credibility does not have either direct or indirect impacts on COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

Based on Lewis and Feiring (Citation1992) and Ashari et al. (Citation2022), the direct effect shows that a variable has an influence on COVID-19 preventive behaviors without going through a mediating variable. In other words, changing these variables will directly cause changes in COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Meanwhile, the indirect effect shows that the effect of a variable on COVID-19 preventive behaviors is through a mediating variable. Thus, changing these variables will not directly cause changes in COVID-19 preventive behaviors but it will cause changes in the mediating variables first.

This study revealed that awareness of COVID-19 preventive behaviors indirectly affects COVID-19 preventive behaviors through knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding is in line with that of the HET. According to HET, COVID-19 preventive behaviors occur in three stages: cognitive (i.e., awareness and knowledge), affective (i.e., attitude), and conative/behavioral (i.e., behavioral intention and COVID-19 preventive behavior). This finding also supports previous findings examined by Zhao et al. (Citation2020), Duffett (Citation2020), Wang et al. (Citation2020), Xin and Seo (Citation2020), Hong et al. (Citation2021), and Sangeeta and Tandon (Citation2021).

This study found that PBC had no direct impact on COVID-19 preventive behaviors, but PBC indirectly affected COVID-19 preventive behaviors through behavioral intention. This finding was supported by Park and Oh (Citation2022) and Trifiletti et al. (Citation2022). However, this finding differs from that of the TPB. According to the TPB, PBC has a direct and indirect effect on behavior. The absence of PBC’s direct influence on COVID-19 preventive behaviors may be due to the context of this research. Considering that COVID-19 is a new virus for the public, making it difficult for them to directly change their behaviors to COVID-19 preventive behaviors without strong motivation, even though they have enough capacity to perform these behaviors. This condition made PBC indirectly affect COVID-19 preventive behaviors through behavioral intentions.

This study showed that subjective norms have a positive and significant impact on behavioral intention toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding is in accordance with TPB. This finding is also supported by previous studies (e.g., Ahmad et al., Citation2020, Sumaedi et al., Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Liu et al., Citation2021; Twum et al., Citation2021).

This study found that perceived threat positively and significantly influences awareness, knowledge, and attitude toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding supports those of previous studies (e.g. (Rather, 2021Wnuk et al., Citation2020, Paige et al., Citation2018)., Perceived threat did not significantly influence behavioral intention and COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Although several previous studies also found a non-significant effect of perceived threat of COVID-19 on behavioral intention (e.g., Sumaedi et al., Citation2020; Walrave et al., Citation2020; Yang et al., Citation2022) and COVID-19 preventive behaviors, e.g Alagili and Bamashmous (Citation2021); Karimy et al. (Citation2021); Mahindarathne (Citation2021); Mirzaei et al. (Citation2021), this finding is not in line with HBM. This finding may also be due to the fact that COVID-19 is a new disease. This caused someone to lack awareness, knowledge, and attitudes toward the behaviors needed to face COVID-19. On the other hand, according to HET, behavior is formed through three stages: cognitive, affective, and conative. Someone who has a high perception of COVID-19 May not perform COVID-19 preventive behaviors since he/she was not aware, knew, and liked the behavior. This condition caused a non-significant direct effect of the perceived threat of COVID-19 on COVID-19 preventive behaviors and behavioral intention.

With regard to digital communication media factors, this study revealed several findings. First, digital health communication platforms have a significant and positive influence on awareness of and COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding is in accordance with previous findings by Mahmood et al. (Citation2021), Li and Liu (Citation2020), and Al-Dmour et al. (Citation2020). Second, health communication exposure had a positive and significant impact on awareness, attitude, and COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding is in line with those of previous studies, such as Faasse and Newby (Citation2020), Bago and Lompo (Citation2019), and Rivas et al. (Citation2021). Third, health communication message characteristics only had significant and positive effects on knowledge and attitudes toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding supports those of several other researchers (e.g., Borah et al., Citation2021; Carfora & Catellani, Citation2021; Ezeah et al., Citation2020; Rains & Karmikel, Citation2009).

Another finding related to digital communication media factors is the non-significant effect of health communication source credibility on awareness, knowledge, attitude, behavioral intention, and COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This finding differs from those of previous studies (Gehrau et al., Citation2021; Hoda, Citation2016; Vlasceanu & Coman, Citation2022). The difference may be due to the context of the research being different from other studies. COVID-19 is a novel disease, which implies that knowledge related to its handling of COVID-19 remains limited during the initial appearance of the virus. Furthermore, the condition also has an impact on the public, who often find different perspectives given by experts in handling the virus. This condition may reduce the importance of source credibility perceived by the public. Furthermore, several popular digital media platforms were still able to provide information in text format (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook, websites). Text format information might have made it difficult for digital media users to confirm whether the source of information is credible, even though the information already included the name of the author(s) with their medical expertise or degree. This might have occurred because anyone can create information that is actually hoaxes by mentioning that the source of information is a medical expert. This might have been the reason why many people do not consider the source credibility of digital communication media in practicing COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Theoretically, based on The Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1981), this finding indicated that the research subjects tended to select the central route rather than the peripheral route in information processing. In other words, in the context of COVID-19 preventive behaviours, the research subjects tended to consider the information content than information source. In the other context than COVID-19 preventive behaviours, this finding is in line with Park et al. (Citation2007) and Wu and Wang (Citation2011).

Based on the previous discussions, it can be stated that this research has offered at least two insights in addressing the complex problem, namely health behaviour during a pandemic, in the context of developing country. First, we can integrate psychological factors and communication media-related factors in order to explain health behaviour during a pandemic. We implemented this approach in the context of digital health communication media. Future research may apply this approach to other health communication media. Second, this research has identified that people tended to select the central route rather than the peripheral route in information processing in this context. In other words, message characteristic tended to be more important than source credibility in the context of health communication during a pandemic in developing country.

4.3. Managerial implications

Based on these theoretical implications, this study has several managerial implications. In general, the managerial implications proposed in this study are oriented toward psychological aspects and digital health communication media. First, regarding health education on COVID-19 preventive behaviors, the government needs to consider the public’s cognitive, affective, and conative/behavioral aspects. In terms of the cognitive aspect, health education on COVID-19 preventive behaviors should be able to increase public awareness and knowledge of COVID-19 preventive behaviors. In terms of the affective aspect, health education also needs to evoke feelings of positive emotions, fun, and a liking for COVID-19 preventive behaviors. As for the conative/behavioral aspect, COVID-19 preventive health education needs to motivate the public to practice such behaviors.

Second, when providing health education on COVID-19 preventive behaviors, fear of COVID-19 needs to be instilled among the public. People need to feel that the disease is extremely dangerous, and the chance of contracting COVID-19 is high. In relation to this, the government can periodically provide information on the death rate of COVID-19 to the public.

Third, the government can also inform the public that practicing COVID-19 preventive behaviors is easy and requires minimal effort. Fourth, when campaigning for COVID-19 preventive behaviors, the government can involve influential figures in the community. These influential figures may include celebrities, influencers, religious figures, health experts, public officials, etc. The government can also include housewives as drivers of household health. The objective was to create a mutually supportive social environment for practicing COVID-19 preventive behaviors. References from important figures may motivate individuals to practice COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

Fifth, the government needs to utilize various DHCMPs when campaigning for COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This means that a health message about COVID-19 prevention should be disseminated through a single medium. The message must be extensively distributed through various DMPs, such as WhatsApp, TikTok, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, websites, and health applications. Such measures are aimed at getting more people to receive information about COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

Sixth, information disseminated through various platforms must also be delivered intensively. If possible, information about COVID-19 preventive behaviors should be disseminated daily over a long period. This is intended to repeatedly expose the public to such information so that they are consciously or unconsciously encouraged to practice COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

Lastly, when campaigning for COVID-19 preventive behaviors, the government needs to ascertain that the contents of messages disseminated to the public are of good quality. This is so that each message that the public receives is true (not hoaxes) and easily understood. Accordingly, before the contents of messages pertaining to COVID-19 preventive behaviors are distributed to the wider public, the messages should be pre-tested on members of the public to ensure that the contents meet several criteria, that is, easy to understand, accurate/true, as necessary, up-to-date, and detailed.

5. Conclusion, limitation and future research

COVID-19 preventive behaviors can be viewed as an effective method for suppressing the spread of COVID-19 in the population. This study developed and tested a model that can explain COVID-19 preventive behaviors. This study revealed that COVID-19 preventive behaviors are not influenced only by psychological factors. Other factors related to digital health communication media have also been confirmed to have an impact on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. These effects can be applied both directly and indirectly. Behavioral intention is a psychological factor that has a direct and positive influence on COVID-19 preventive behaviors is behavioral intention. Other psychological factors that have been confirmed to have positive and indirect effects on COVID-19 preventive behaviors are perceived threat, subjective norms, PBC, awareness, knowledge, and attitude. On the other hand, DHCMPs and communication exposure have been proven to have positive and direct impacts on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Meanwhile, message characteristics have a positive and indirect effect on COVID-19 preventive behaviors. In the current study, source credibility was confirmed to have neither a direct nor indirect influence on COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

Although interesting findings were obtained in this study, some limitations remain. The main limitation of this research is that the data were obtained using the online survey method and purposive sampling technique. The online survey method was necessary because it facilitated enumerators/researchers to avoid direct physical contact with respondents. The purposive sampling technique caused the collected data to be disproportionate. In this study, the respondents were dominated by young students who were students and without income. Furthermore, it may be impossible to generalize these findings to other contexts. Accordingly, we suggest that future research use better sampling techniques. Future studies could test this research model in other regions. Several determinants of health behaviors can also be appended to enrich our findings. Examples of other determinants include personal characteristics, health consciousness, perceived healthiness, digital health literacy, attention to health information, and false information on digital communication media.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Subhan Afifi

Subhan Afifi is an associate professor at the Department of Communication, Universitas Islam Indonesia. His research interest includes Heath Communication, Digital Public Relations, and Islamic Communication.

I Gede Mahatma Yuda Bakti

I Gede Mahatma Yuda Bakti is a researcher at Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interest includes Quality Management, Perceived Quality, Consumer Behaviour and Social Marketing.

Aris Yaman

Aris Yaman is a researcher at Research Center for Computational, National Research and Innovation Agency, Bogor, Indonesia. His research interest includes statistics and scientometrics.

Sik Sumaedi

Sik Sumaedi is a researcher at Research Center for Testing Technology and Standards, National Research and Innovation Agency, Tangerang, Indonesia. His research interest includes Quality Management, Perceived Quality, and Consumer Behaviour.

References

- Abu-Gharbieh, E., Saddik, B., El-Faramawi, M., Hamidi, S., & Basheti, M. (2019). Oral health knowledge and behavior among adults in the United Arab Emirates. BioMed Research International, 2019, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7568679

- Afifi, S., Santoso, H. B., & Hasani, L. M. (2022). Investigating students’ online self-regulated learning skills and their e-learning experience in a prophetic communication course. Ingénierie des Systèmes d’Information, 27(3), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.18280/isi.270304

- Ahmad, M., Iram, K., & Jabeen, G. (2020). Perception-based influence factors of intention to adopt COVID-19 epidemic prevention in China. Environmental Research, 190(July), 109995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109995

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(1), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alagili, D. E., & Bamashmous, M. (2021). The health belief model as an explanatory framework for COVID-19 prevention practices. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 14(10), 1398–1403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.024

- Al-Dmour, H., Masa’deh, R., Salman, A., Abuhashesh, M., & Al-Dmour, R. (2020). Influence of social media platforms on public health protection against the COVID-19 pandemic via the mediating effects of public health awareness and behavioral changes: Integrated model. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.2196/19996

- Alrababa’h, A., Marble, W., Mousa, S., & Siegel, A. A. (2022). Can exposure to celebrities reduce prejudice? The effect of Mohamed Salah on Islamophobic behaviors and attitudes —CORRIGENDUM. American Political Science Review, 116(2), 775. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001258

- Altmann, T. K. (2008). Attitude: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 43(3), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00106.x

- Al-Wesabi, A. A., Abdelgawad, F., Sasahara, H., & el Motayam, K. (2019). Oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour of dental students in a private university. BDJ Open, 5(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41405-019-0024-x

- Anaki, D., Sergay, J. (2021). Predicting health behavior in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Worldwide survey results from early March 2020. PLoS ONE, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244534

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Anzanpour, A., Azimi, I., Gotzinger, M., Rahmani, A. M., Taherinejad, N., Liljeberg, P., Jantsch, A., & Dutt, N. (2017). Self-awareness in remote health monitoring systems using wearable electronics. Proceedings of the 2017 Design, Automation and Test in Europe, DATE 2017, 1056–1061. https://doi.org/10.23919/DATE.2017.7927146

- Aschwanden, D., Strickhouser, J. E., Sesker, A. A., Lee, J. H., Luchetti, M., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2021). Preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with perceived behavioral control, attitudes, and subjective norm. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.662835

- Ashari, H., Abbas, I., Abdul-Talib, A.-N., & Mohd Zamani, S. N. (2022). Entrepreneurship and sustainable development goals: A Multigroup analysis of the moderating effects of entrepreneurship education on Entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability, 14(1), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010431

- Astrini, N., Bakti, I. G. M. Y., Rakhmawati, T., Sumaedi, S., & Yarmen, M. (2021). A repurchase intention model of Indonesian herbal tea consumers: Integrating perceived enjoyment and health belief. British Food Journal, 124(1), 140–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2021-0189

- Aydin, S., Özkaya, H., Özbekkangay, E., Okan Bakir, B., Kaya Cebioglu, I., & Günalan, E. (2022). The comparison of the effects of different Nutrition education Methods on Nutrition knowledge level in high school students. Acibadem Universitesi Saglik Bilimleri Dergisi, 13(1), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.31067/acusaglik.963347

- Bago, J. L., & Lompo, M. L. (2019). Exploring the linkage between exposure to mass media and HIV awareness among adolescents in Uganda. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 21(April), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2019.04.004

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

- Bakti, I. G. M. Y., Sumardjo Fatchiya, A., & Syukri, A. F. (2021). An empirical Investigation of Equity of health promotion: The role of message source and content. Studies on Ethno-Medicine, 15(3–4), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.31901/24566772.2021/15.3-4.641

- Barati, M., Bashirian, S., Jenabi, E., Khazaei, S., Karimi-Shahanjarini, A., Zareian, S., Rezapur-Shahkolai, F., & Moeini, B. (2020). Factors associated with preventive behaviours of COVID-19 among hospital staff in Iran in 2020: An application of the protection motivation theory. Journal of Hospital Infection, 105(3), 430–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.035

- Barbera, F. L., & Ajzen, I. (2020). Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.2056

- Bedard, S. A. N., & Tolmie, C. R. (2018). Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(6), 1388–1396. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1654

- Biswas, M. R., Ali, H., Ali, R., & Shah, Z. (2022). Influences of social media usage on public attitudes and behavior toward COVID-19 vaccine in the Arab world. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2074205

- Bonell, C., Michie, S., Reicher, S., West, R., Bear, L., Yardley, L., Curtis, V., Amlôt, R., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain “social distancing” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Key principles. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(8), 617–619. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214290

- Borah, P., Hwang, J., Hsu, Y. C., & (Louise). (2021). COVID-19 vaccination attitudes and intention: Message framing and the moderating role of perceived vaccine benefits. Journal of Health Communication, 26(8), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1966687

- Boulianne, S., & Theocharis, Y. (2020). Young people, digital media, and engagement: A meta-analysis of research. Social Science Computer Review, 38(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318814190

- Boyle, S. C., LaBrie, J. W., Froidevaux, N. M., & Witkovic, Y. D. (2016). Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors, 57, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.011

- BPS-Statistics Inodonesia. (2019). Welfare Statistics 2019. BPS- Statistics Inodonesia.

- Bronfman, N. C., Repetto, P. B., Cisternas, P. C., & Castañeda, J. V. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption of COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Chile. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(10), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105331

- Carfora, V., & Catellani, P. (2021). The effect of persuasive messages in promoting home-based physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(April), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644050

- Carpenter, R. (2005). Perceived threat in compliance and adherence research. Nursing Inquiry, 12(3), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2005.00269.x

- Ceylan, M., & Hayran, C. (2021). Message framing effects on individuals’ social distancing and helping behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(March), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.579164

- Chen, X., & Chen, H. H. (2020). Differences in preventive behaviors of COVID-19 between urban and rural residents: Lessons learned from a cross-sectional study in china. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124437

- Cheston, C. C., Flickinger, T. E., & Chisolm, M. S. (2013). Social media use in medical education: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(6), 893–901. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23

- Choi, D. H., & Noh, G. Y. (2020). The influence of social media use on attitude toward suicide through psychological well-being, social isolation, and social support. Information Communication and Society, 23(10), 1427–1443. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1574860

- Collins, P. J., Hahn, U., von Gerber, Y., & Olsson, E. J. (2018). The bi-directional relationship between source characteristics and message content. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00018

- Conlin, J., Baker, M., Zhang, B., Shoenberger, H., & Shen, F. (2022). Facing the strain: The persuasive effects of conversion messages on COVID-19 vaccination attitudes and behavioral intentions. Health Communication, 38(11), 2302–2312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2065747

- Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6

- DeDonno, M. A., Longo, J., Levy, X., & Morris, J. D. (2022). Perceived susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 on prevention practices, early in the pandemic in the state of Florida. Journal of Community Health, 47(4), 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01090-8

- Deng, Z., Liu, S., & Hinz, O. (2015). The health information seeking and usage behavior intention of Chinese consumers through mobile phones. Information Technology & People, 28(2), 405–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-03-2014-0053

- den Hamer, A. H., & Konijn, E. A. (2015). Adolescents’ media exposure may increase their cyberbullying behavior: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.016

- Duffett, R. (2020). The youtube marketing communication effect on cognitive, affective and behavioural attitudes among generation Z consumers. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(12), 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125075

- Dutta, J., & Bhattacharya, M. (2023). Impact of social media influencers on brand awareness: A study on college students of Kolkata. Communications in Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.21924/chss.3.1.2023.44

- Ezati Rad, R., Mohseni, S., Kamalzadeh Takhti, H., Hassani Azad, M., Shahabi, N., Aghamolaei, T., & Norozian, F. (2021). Application of the protection motivation theory for predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Hormozgan, Iran: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 466. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10500-w

- Ezeah, G., Ogechi, E. O., Ohia, N. C., & Celestine, G. V. (2020). Measuring the effect of interpersonal communication on awareness and knowledge of COVID-19 among rural communities in Eastern Nigeria. Health Education Research, 35(5), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyaa033

- Faasse, K., & Newby, J. (2020). Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: Perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.551004

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Fenitra, R. M., Praptapa, A., Suyono, E., Kusuma, P. D. I., & Usman, I. (2021). Factors influencing preventive intention behavior towards COVID-19 in Indonesia. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 16(1), 14–27.

- Fico, A. E., & Lagoe, C. (2018). Patients’ perspectives of Oral Healthcare providers’ communication: Considering the impact of message source and content. Health Communication, 33(8), 1035–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1331188

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gehrau, V., Fujarski, S., Lorenz, H., Schieb, C., & Blöbaum, B. (2021). The impact of health information exposure and source credibility on COVID-19 vaccination intention in germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094678

- Ghazali, E., Soon, P. C., Mutum, D. S., & Nguyen, B. (2017). Health and cosmetics: Investigating consumers’ values for buying organic personal care products. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39, 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.08.002

- Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., Maibach, E. W., Ballew, M. T., Bergquist, P., Kotcher, J. E., Marlon, J. R., Rosenthal, S. A., & Leiserowitz, A. (2020). Mask-wearing increased after a government recommendation: A natural experiment in the U.S. During the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00044

- Gomez-Aguinaga, B., Oaxaca, A. L., Barreto, M. A., & Sanchez, G. R. (2021). Spanish-language news consumption and latino reactions to covid-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189629

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R., Babin, B., & Black, W. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (p. 165). Sage.

- Han, R., & Xu, J. (2020). A comparative study of the role of interpersonal communication, traditional media and social media in pro-environmental behavior: A China-based study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 7164. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061883

- Hasan, A. A.-T. (2022). Technology attachment, e-attitude, perceived value, and behavioral intentions towards uber-ridesharing services: The role of hedonic, utilitarian, epistemic, and symbolic value. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science, 5(3), 239–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcmars-01-2022-0002

- Haytko, D. L., Mai, E., Taillon, B. J., & Shirley. (2021). COVID-19 information: Does political affiliation impact consumer perceptions of trust in the source and intent to comply? Health Marketing Quarterly, 38(2–3), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2021.1986996

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- High, A. C., & Young, R. (2018). Supportive communication from bystanders of cyberbullying: Indirect effects and interactions between source and message characteristics. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 46(1), 28–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2017.1412085

- Hoda, J. (2016). Identification of information types and sources by the public for promoting awareness of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. Health Education Research, 31(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyv061

- Hong, W., Liu, R., de Ding, Y., Hwang, J., Wang, J., & Yang, Y. (2021). Cross-country differences in stay-at-home behaviors during peaks in the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the United States: The roles of health beliefs and behavioral intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042104

- Hosseinzadeh, M., Ahmed, O. H., Ehsani, A., Ahmed, A. M., Hama, H. K., & Vo, B. (2020). The impact of knowledge on e-health: A systematic literature review of the advanced systems. Kybernetes, 50(5), 1506–1520. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-12-2019-0803

- Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Velazquez-Alva, M. C., Zepeda-Zepeda, M. A., Cabrer-Rosales, M. F., Lazarevich, I., & Castaño-Seiquer, A. (2020). Effect of income level and perception of susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 on stay-at-home preventive behavior in a group of older adults in Mexico city. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207418

- Jain, T., Currie, G., & Aston, L. (2022). COVID and working from home: Long-term impacts and psycho-social determinants. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 156, 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.12.007

- Jiang, P., & Rosenbloom, B. (2014). Consumer knowledge and external pre-purchase information search: A meta-analysis of the evidence. In Consumer culture theory (Vol. 15, pp. 353–389). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0885-2111(2013)0000015023

- Jirattikorn, A., Tangmunkongvorakul, A., Musumari, P. M., Ayuttacorn, A., Srithanaviboonchai, K., Banwell, C., & Kelly, M. (2020). Sexual risk behaviours and HIV knowledge and beliefs of Shan migrants from Myanmar living with HIV in Chiang Mai, Thailand. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 16(4), 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-09-2019-0080

- Kahlor, L., & Rosenthal, S. (2009). If we seek, do we learn?: Predicting knowledge of global warming. Science Communication, 30(3), 380–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008328798

- Kang, H. (2021). Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18(17), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17

- Karimy, M., Bastami, F., Sharifat, R., Heydarabadi, A. B., Hatamzadeh, N., Pakpour, A. H., Cheraghian, B., Zamani-Alavijeh, F., Jasemzadeh, M., & Araban, M. (2021). Factors related to preventive COVID-19 behaviors using health belief model among general population: A cross-sectional study in Iran. BMC Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11983-3

- Kemp, S. (2020). Digital 2020: Indonesia. Datareportal.

- Khajebishak, Y., Faghfouri, A. H., Molaei, A., Rahmani, V., Amiri, S., Asghari Jafarabadi, M., & Payahoo, L. (2021). Investigation of the potential relationship between depression, diabetes knowledge and self-care management with the quality of life in diabetic patients – an analytical study. Nutrition & Food Science, 51(1), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/NFS-01-2020-0016

- Kim, Y., Wang, Y., & Oh, J. (2016). Digital media use and social engagement: How social media and smartphone use influence social activities of college students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0408

- Kirscht, J. P. (1983). Preventive health behavior: A review of research and issues. Health Psychology, 2(3), 277–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.2.3.277

- Kock, F., Berbekova, A., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tourism Management, 86, 104330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330

- Kolte, A., Mahajan, Y., Vasa, L., & Böckerman, P. (2022). Balanced diet and daily calorie consumption: Consumer attitude during the COVID-19 pandemic from an emerging economy. PLoS ONE, 17(8), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270843

- Koohang, A., Sargent, C. S., Nord, J. H., & Paliszkiewicz, J. (2022). Internet of things (IoT): From awareness to continued use. International Journal of Information Management, 62, 102442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102442

- Langlie, J. K. (1979). Interrelationships among preventive health behaviors: A test of competing hypotheses. Public Health Reports, 94(3), 216–225.

- Le, T. D., Dobele, A. R., & Robinson, L. J. (2018). WOM source characteristics and message quality: The receiver perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 36(4), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-10-2017-0249