Abstract

The unprecedented influx of forced migrants into Ethiopia and the number of urban refugees in cities have gained increasing attention in intellectual and humanitarian circles. This study employs a sustainable livelihood framework to gain insight into the livelihood strategies of refugees residing in Addis Ababa. Using 20 in-depth interviews, 10 key informant interviews, and four focus group discussions, this study scrutinized the livelihood strategies of Somali and Eritrean refugees in the city. The interviews and focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. Remarkably, this research demonstrates that the primary sources of income for these refugees were international aid, remittances, wages, self-employment, and support from families and acquaintances. High living expenses, acculturation issues, diminished self-worth, emotional instability and mobility, economic hardships, conflict, security issues, violence, theft, and robbery were identified as the main sociocultural and financial challenges to their livelihoods. The existence of beneficial policy frameworks and the shared cultural heritage of the host community and urban refugees indicate opportunities for their integration. This study provides insights for humanitarian and government agencies and future research that focuses on sustainable urban refugee livelihoods.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Ethiopia’s policy of welcoming refugees from 26 different nations and providing housing in 26 camps and cities has been widely praised by the international community. The country’s progressive refugee policy offers extended rights to those seeking asylum, and as of December 2022, Ethiopia had hosted 880,056 refugees. The majority of these refugees, 88 percent, were housed in camps, with 9 percent in urban areas and the remaining 3 percent in settlements. This qualitative study aims to investigate the obstacles and prospects in their pursuit of survival and livelihoods. While humanitarian assistance, support from friends and family, and diaspora aid can be essential, they may not be sufficient for refugees to establish sustainable livelihoods in urban areas. Consequently, to facilitate the establishment of sustainable livelihoods for refugees, the policy must be implemented in its entirety.

1. Introduction

By mid-2022, the number of displaced persons who fled their homes due to conflict, persecution, and environmental modifications had reached 103 million (hereafter cited as UNHCR, Citation2022, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Out of these, roughly 32.5 million were refugees, and 4.9 million were asylum seekers (UNHCR, Citation2022). Recognized as one of the most conflict-stricken regions in the world, the Horn of Africa is renowned for its vast exodus of refugees and is deemed a “zone of refugee-producing and receiving regions” (Assefaw, Citation2006). According to the UNHCR (Citation2022), 4.95 million people were displaced and sought asylum in the East and Horn of Africa, as well as the Great Lakes region, as of June 2022. This displacement is an outcome of a combination of long-standing conflicts in Somalia, South Sudan, Eritrea, and Sudan, political aggression, climate change, and food insecurity (Mbiyozo, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2018). Such forced migration frequently violates individuals’ rights and liberties. As a result, the majority have moved into settings that are woefully unfit to uphold even the most basic standards of human dignity.

The inflow of refugees into Ethiopia is not a recent event but rather has a long history going back to the seventh century, when it served as a meeting point for diverse civilizations, welcoming and accommodating individuals of varying origins and beliefs (Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs [ARRA], Citation2011; Adugna, Citation2021; Wondewosen, Citation1995). Since the 1960s, Ethiopia has upheld an open-door policy, providing a safe haven for refugees from neighboring nations, including South Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, Yemen, and the Great Lakes Region. As of December 2022, Ethiopia hosted 880,056 refugees and 2,220 asylum seekers, and approximately 76% of refugees arrived in the country from 2013 to 2022 (UNHCR, Citation2023). Of the total refugees, 772,024 (88%) were accommodated in camps, 83361 (9%) in urban areas, and 24,630 (3%) in settlements. Table presents the distribution and trends of urban refugees in Ethiopia.

Table 1. Distribution and trends of urban refugees in Addis Ababa, Asayita and Mekele

As shown in Table , the urban refugee population has been increasing, mainly in Addis Ababa. As of December 2022, 72951 refugees had resided in the city. There has been a huge increase in the refugee population because of Ethiopia’s Tigray War. Following the conflict, the urban refugee population in Addis Ababa saw a substantial rise, primarily attributed to the voluntary relocation of Eritrean refugees from Tigray’s camps. This figure constitutes approximately 60% of the overall urban refugee population (UNHCR, Citation2022). It nearly doubled between January 2021 and November 2021. Asayita has also witnessed an over 400% increment between December 2019 and August 2022.

The policy response towards the reception of refugees in Ethiopia has been driven by various interconnected factors. These include ties to the country of origin of refugees, concerns about national security, the need for support from international refugee regimes, the ability of the state to control its borders, and the desire to build a political reputation that goes beyond simple humanitarian hospitality (Assefaw, Citation2006). Prior to 2004, the 1951 United Nations (UN) Convention on Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, as well as the 1969 Organization for African Unity (OAU) Convention on Refugees, to which the country gave its consent, largely governed Ethiopia’s legal obligations and policy for hosting refugees. Ethiopia put the Refugee Proclamation No. 409/2004 into effect in 2004. Despite praise for the proclamation’s inclusion of the UN 1951 and OAU 1969 categories of refugees and the prohibition of arrest and persecution for any unauthorized immigration, it retained the reservation that had existed before it (Zelalem, Citation2017). The aforementioned proclamation does not include any measures for the livelihoods of refugees, although it does provide legal structures for their protection.

In 2015, the Government of Ethiopia (GoE) collaborated with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to prepare an urban livelihood strategy aimed at executing a comprehensive livelihood program aimed at enhancing self-sufficiency among refugees residing in Ethiopia’s urban areas (UNHCR, Citation2017). Nevertheless, the Refugee Proclamation No. 1110/2019, which offers dignified benefits to refugees and asylum seekers, was passed. A driver’s qualification certification license, their own identity papers, travel documents, access to banking and financial services, access to telecommunication services, and vital event registration, all of which are necessary for engaging in livelihood activities, are all made possible by this Proclamation for Refugees (FDRE, Citation2019). Additionally, the Proclamation grants refugees the right to freedom of movement, access to education, justice, healthcare services, and employment. One of the fundamental distinctions between Proclamation No. 1110/2019 and Proclamation No. 409/2004 is the incorporation of a provision that recognizes the entitlement of refugees to participate in remunerative activities.

The configuration of refugee settlements in Ethiopia is predominantly confined to encampments in remote rural areas owing to the perceived or actual financial obligations and security apprehensions of the government. Despite encampments being classified as provisional settlements for refugees, a significant number of refugees in the country have continued to reside in camps for a prolonged period. The trend of self-settlement and facilitated settlement of refugees in urban regions is on the rise due to the country’s out-of-camp policy and urban support programs. Refugees are situated in Addis Ababa, Asayita, and Samara-Logia. Somali and Eritrean refugees, among others, have been established in Addis Ababa for a prolonged period.

The Out-of-Camp Policy (OCP) and Urban Assistance Program (UAP) have enabled refugees to live in Addis Ababa through legal exemptions to encampment. The former is only accessible to Eritrean refugees who possess the capacity to provide for themselves or are backed by their families, whereas the latter is intended for refugees who require special medical care, protection, or humanitarian assistance that cannot be effectively provided by camp-level institutions. Although UAP refugees benefit from a monthly stipend as well as health and educational assistance, OCP refugees do not receive such provisions (Brown et al., Citation2018). As of 2019, about 35,000 Eritreans had the status of “out-of-camp” (OCP), and there were 5,000 UAP refugees in Addis Ababa as of 2018 (Betts et al. 2019). It is anticipated that this number will rise because of the city’s growing refugee population.

The study undertaken by Wogene (Citation2017) focused exclusively on the local integration of Eritrean and Somali refugees under the out-of-camp scheme, disregarding concerns pertinent to the livelihoods, challenges, and opportunities of urban refugees. In contrast, Aida (Citation2017) focused on the impact of the Out-of-Camp Scheme for Eritrean Refugees on the host community, with particular emphasis on self-sufficiency, food security, and safeguarding . Mekonnen (Citation2019) investigated refugees’ access to livelihood opportunities and services in Addis Ababa. Nonetheless, recent studies on urban refugee livelihood strategies are limited. With the exception of Mekonnen’s (Citation2019) endeavor, there is a dearth of research that specifically delves into the livelihood strategies of urban refugees while simultaneously taking into account the challenges and opportunities they encounter in the context of Addis Ababa. Consequently, this study employed a sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) to comprehend the livelihood strategies employed by Eritrean and Somali refugees residing in the Gofa Mebrat Hayil and Bole Michael areas of Addis Ababa.

2. Sustainable livelihood framework

This study employed a sustainable livelihood framework to explore livelihood strategies, challenges, and opportunities for urban refugees in the Bole and Nifas Silk Lafto sub-cities of Addis Ababa. According to Mistri and Das (Citation2020), understanding people’s livelihoods and the techniques they use to support them is made easier by using a sustainable livelihood approach. According to Wake and Barbelet (Citation2020), the SLF allows us to investigate how refugees view their environment, threats, opportunities, objectives, and courses of action.

Urban refugees are intricately linked to the host community in terms of economic, political, and cultural aspects. This inevitably results in their means of survival being intertwined with local processes and interactions. The urban environment presents specific possibilities and limitations for those striving to enhance their livelihood. Comparable to the impoverished, urban refugees encounter difficulties such as increasing rates of unemployment, insecure access to housing, heightened pressure on state and community resources, as well as obstacles such as xenophobia and an insecure legal status. These factors leave them at a higher risk of exploitation and marginalization, as stated by De Vriese (Citation2006).

According to Jacobson (Citation2006), the theory of refugee livelihood must consider the specific vulnerabilities of refugees and the strategies they employ to mitigate these vulnerabilities. To understand the situation of urban refugees, she proposed using DFID’s (Department for International Development) adapted livelihood framework, which considers power relations and places a lot of stress on the idea of vulnerability (Jacobson, Citation2006). Wake and Barbelet (Citation2020) conducted a study on the livelihoods of refugees using data from various regions, including Central African Republic (CAR) refugees in Cameroon, Rohingya refugees in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Syrian refugees in Zarqa, Jordan, and Syrian refugees in Istanbul, Turkey. A modified version of Levine (Citation2014) was used to study refugees. Following Chambers and Conway (Citation1991), Farrington et al. (Citation2002), and Jacobsen (Citation2002), the elements of the SLF are operationalized in the following paragraphs:

In this study, by refugee livelihood, we refer to the activities refugees engage in and their sources of income. Vulnerability refers to the unease or lack of well-being of urban refugees as a result of shifting social, economic, and political settings manifested as quick shocks, long-term trends, or seasonal cycles. The degree of vulnerability is correlated with both the severity of external threats to the welfare of urban refugees and their capacity to resist and recover from such external stressors.

Assets refer to a wide variety of financial, human, social, physical, natural and political resources. Urban refugees who employ assets in their livelihood strategies may not always own those assets; instead, they may have varying degrees of access to and control over those assets.

PIPs include a wide range of social, political, economic, and environmental elements, such as institutions, organizations, policies, and laws that influence urban refugees’ decisions and thus contribute to their livelihoods. They are crucial in deciding whether urban refugees have access to the many types of capital assets they employ to pursue their livelihood plans, either by acting as conduits to make assets accessible to them or as barriers to their access.

Livelihood strategies are planned actions that urban refugees engage in to increase their standards of living. They typically consist of various actions intended to increase their asset base and access commodities and services for consumer use.

Livelihood outcomes are the outcomes of urban refugee livelihood strategies that impact their asset bases. Successful livelihood strategies enable urban refugees to build asset bases as a buffer against shocks and stresses, whereas unsuccessful strategies lead to asset depletion and increased vulnerability (Rohwerder, Citation2016).

Given the foregoing, this study does not attempt to thoroughly analyze and evaluate every component of the framework, as it relates to urban refugees in the study area. The framework described above is limited to studying refugees’ urban livelihood strategies, challenges, and opportunities. The present study utilized the framework proposed by Levine (Citation2014), which was designed to effectively encapsulate a multitude of components that are pertinent to the research in question.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Context

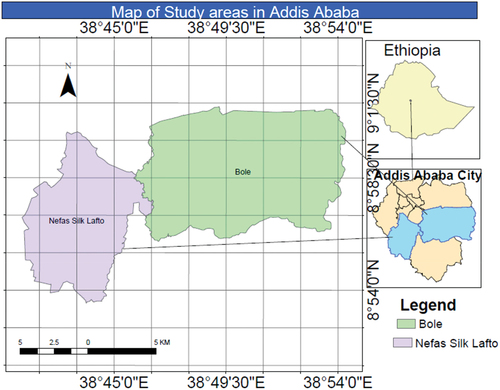

Addis Ababa, situated in Ethiopia, serves as the capital city and is one of the 11 member states of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). The city of Addis Ababa has chartered status, thereby accounting for its dual categorization as a city and state. It serves as the headquarters for several international organizations, such as the African Union (AU) and Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), and is identified as a rapidly expanding metropolis that attracts a vast population from both rural and urban areas of the nation. It currently has an estimated population of approximately 4 million out of the 20 million urban residents of the country. The city has been divided into 11 sub-cities (known as kifle-ketema in Amharic) and 99 administrative districts, or woredas. The subcities encompass Addis Ketema, Nifas Silk-Lafto, Bole, Gulele, Akaki-Kaliti, Kolfe-Keranyo, Yeka, Arada, Kirkos, Lideta, and Lemi-Kura. Among these subcities, as Figure shows, this study focuses only on two: Bole and Nifas-Silk Lafto. The Nefas Silk-Lafto subcity has 12 woredas (an administrative structure below a sub-city), whereas the Bole subcity has 14 woredas (CSA, Citation2018). These subcities were selected because Bole is the major hosting area for Somali refugees, whereas Nefas Silk-Lafto is one of the major areas in which Eritrean refugees are concentrated. Approximately 46% of refugees in Addis Ababa are concentrated in Nifas Silk-Lafto, while 29% are concentrated in Bole (UNHCR, Citation2022). Figure shows the subcities studied in Addis Ababa.

3.2. Research design

This study employs a qualitative approach. The use of a qualitative research design, as proposed by Catherine (Citation2007), entails the investigation of participant attitudes, experiences, and in-depth opinions, with a focus on the interpretation of observations in line with the subjects’ own understanding. In addition, Catherine (Citation2007) recognized that the implementation of this research is carried out within ever-changing social contexts, where the participants of the investigation are individuals and the emphasis is placed on their interrelationships. Furthermore, qualitative methodology entails the comprehension of personal experiences, phenomena, and processes in the social world, as highlighted by Kalof et al. (Citation2008). Therefore, to investigate the livelihoods of urban refugees in Addis Ababa, researchers opted for a qualitative approach. Specifically, within this approach, an exploratory and descriptive research design was utilized to gain insights into the livelihood strategies of Eritrean and Somali refugees in the Bole and Nifas Silk Lafto subcities.

3.2.1. Data gathering methods

This study drew upon both primary and secondary sources to gather data. Primary data were obtained via in-depth interviews conducted with various stakeholders in the study area, including local government officials, officials from the Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs, urban refugees, representatives of humanitarian organizations, and hosts. In addition, the researchers assessed secondary sources, such as published and unpublished research studies, proclamations, and data from both international and domestic humanitarian organizations, to supplement the primary data.

This study employed a range of data collection methods, including in-depth interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), and personal observations. In-depth interviews were conducted to obtain detailed insights into the participants’ opinions, emotions, experiences, and feelings. Semi-structured interview questions were used to examine the respondents’ perceptions of the challenges and opportunities associated with urban refugee livelihoods in the study area. Semi-structured interviews are particularly beneficial as they allow interviewees to reflect on their perceptions while remaining focused on a specific topic (Bryman, Citation1992).

3.2.2. Sampling

Among the various sub-cities located in Addis Ababa, Nefas Silk Lafto and Bole are recognized for their large populations of Eritrean and Somali refugees, respectively. The selection of these sub-cities was purposeful, as within them, the neighborhoods of Gofa Mebrat Hayil and Bole Michael exhibit a disproportionate number of refugees. To conduct the research, the Bole Michael and Gofa Mebrat Hayil areas were deliberately chosen as study sites to gain access to focus-group discussants and interviewees. Purposive sampling was used to select the participants. While other nationalities reside in Addis Ababa, this study focuses on Somali and Eritrean refugees because of their significant numbers. The study area and participants were selected using a purposive sampling technique, as the majority of Eritrean and Somali refugees dwell within these two neighborhoods. The distribution of Eritrean and Somali refugees and asylum seekers in Addis Ababa on 1 February 2018, is presented in Table .

Table 2. Number of Eritrean and Somali refugees estimated to have settled in Addis Ababa

Fifty-four individuals participated in this study. The research involved 20 in-depth interviews, 10 key informant interviews, and 4 focus group discussions. Gofa Mebrat Hayil was the designated area for the Gofa participants, while Somali urban refugees were handpicked from Bole Michael. Participants were selected from two distinct settings: residential areas and offices (ARRA and others), where they received diverse services. To gather data, key informants were selected from ARRA, the International Relief and Recovery Organization (ZOA), the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), Jesuit Refugee Services (JRS), Bole Subcity Woreda 1 and Woreda 6, and hosts.

Four FGDs were conducted: two with Somali refugees in Bole Michael and two with Eritrean refugees in Gofa Mebrat Hayil. Six participants participated in each FGD session. Discussants were chosen based on their protracted residence in the study areas and profound experiences with urban refugees. The gatekeepers in the respective neighborhoods discerningly chose discussants from among the Eritrean and Somali refugees. The sample size for this study, drawn from the Bole Michael and Gofa Mebrat Hayil areas, is summarized in Table .

Table 3. Study sample Eritrean and Somali refugees settled in Addis Ababa

3.2.3. Methods of data analysis

The researchers proceeded with the task of recording, transcribing, and analyzing the data thematically in alignment with the study objectives. The transcribed data were reduced to themes and analyzed. The process of analyzing the data commenced with the categorization and further classification of the data into themes based on livelihood strategies, challenges, and opportunities. The analysis process involved the amalgamation of data from various sources.

3.2.4. Ethical considerations

The fundamental ethical guidelines for this study were followed carefully. The research participants were informed of the purpose and confidentiality of data collection before they agreed to participate in the study. The participants were prompted to participate in the interviews and focus group discussions after receiving complete information about the study. To preserve privacy, both the study’s reporting and data analysis treated the participants’ identities as anonymous.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Profile of study participants

Participants (N = 44) for this qualitative study were purposefully chosen from among the urban refugees living in Addis Ababa’s Gofa Mebrat Hayil and Bole Michael areas in the Nifas-Silk-Lafto and Bole subcities. In addition, 10 key informants were selected from the host community and various humanitarian organizations operating in the study area. The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and aspirations of the respondents are presented in this section. During the interviews and focus group sessions, participants were gathered using a brief checklist. The variables considered were nationality, sex, age, marital status, years of stay, educational attainment, employment status, primary source of income, monthly income, reasons for migration, and future plans. Table summarizes the characteristics of the samples.

Table 4. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of sample urban refugees

This study primarily focuses on Eritrean and Somali refugees. Of the total sample, half were Eritreans and half were Somalis. Most participants were male (70%), while females accounted for only 30 percent. Age-wise, participants were predominantly young, with 70 percent aged ≤30 years. Seventy percent were single, whereas divorced and married individuals accounted for 30 percent of the sample. A total of 52 percent of the sample stayed in Ethiopia between one and three years, and 59 percent had secondary education. Most participants were unemployed (59%), with remittances as the primary source of their monthly income, and earned 2000 ETB or less. Regarding the reasons for their migration, conflict migrants accounted for the majority (43%), followed by economic and political migrants. More than four-fifths of study participants aspired to resettle in Western countries.

4.2. Refugees’ livelihood strategies in Addis Ababa

The study participants indicated that direct aid from humanitarian organizations, remittances, support from relatives and friends, wages, and self-employment were the primary sources of income. The government registers refugees and relocates them to the camps. Individualized monthly rations or assistance, such as 10 kg of wheat, a liter of oil, a kilogram of sugar, salt, and other goods, are provided to them in camps. The government and humanitarian organizations in the camps also provide free medical and educational services to residents. However, after spending a minimum of 45 days in the camp, refugees are given the opportunity to live independently in urban areas without assistance from any national or international agency. As a result, they must provide the full name and address of the guarantor, who must be an Ethiopian citizen, to be eligible for the out-of-camp policy and be classified as an urban refugee. Thus, a reliable individual is required in an emergency. The list of applicants to ARRA indicates that they are urban refugees within two weeks of their application, both at its main office and occasionally in various camps. Ultimately, they obtain a letter or identity number confirming their one-year residency, move from the camp to the city, and begin a new life. A new three-year residency permit or identification card is issued by ARRA when a one-year permit or card expires. According to previous research (Aida, Citation2017; Brown et al., Citation2018; Guesh, Citation2020), the livelihoods of urban refugees depend on humanitarian assistance, support from family members, wages, self-employment, and informal employment.

4.2.1. Remittances

According to research participants, remittances are the main source of income for urban refugees. As they transition from camping to urban life, they are expected to rely on self-employment, financial support from friends or family who reside in Addis Ababa, or wage jobs as their primary source of income. Remittances from friends or family, who reside abroad, mainly in Western nations, are the main source of income to meet their daily needs. One of the FGD participants who had previously emigrated from Somalia to Ethiopia explained this further by mentioning the following.

I am here with my family, and our only source of income is remittances. My relative lives in Canada, and he sends me 150 dollars (4794.12 birr) per month. I know that he is not rich enough to send that amount of money to us, but we have no option. He knows the challenges and does not hesitate to accept them. Sometimes he borrows money from his friends and sends it to us.

If refugees simply depend on remittances, they run the risk of surviving what they can obtain rather than developing plans for a sustainable life. A way of life is considered sustainable if it can withstand stressors and shocks, recover from them, and maintain or increase its capacities and assets (Carney, Citation1998). According to Jacobsen et al. (Citation2014), remittances were received by one-fourth of Sudanese refugees investigated in Cairo. As remittances are an unstable source of income, refugees borrow from other sources. Additionally, they increase their vulnerability.

4.2.2. Wage employment

Some urban refugees work for private businesses, performing activities such as painting, woodworking, tailoring, and garage labor. However, they acknowledged that it was difficult to obtain this employment. Instead, they should have friends or relatives who can recommend them for their positions. It also depends on how engaged and motivated refugees are when looking for work.

The prevalence of informal employment was extensive, where individuals from Eritrean and Somali refugee backgrounds were engaged in establishments owned by refugees or Ethiopians. Individuals of Eritrean origin were commonly hired in the recreational and hospitality domains or in various service industries such as hairdressing or laundry services. A substantial proportion of them exhibited proficiency in domains such as electrical work, welding, or mechanics. Somalis are often employed in shops owned by either Somalis or Ethiopians. This outcome is comparable with the findings of Omata and And (Citation2013) and Brown et al. (Citation2018).

An in-depth interviewee from Eritrea mentioned the following about his job in Addis Ababa:

Last time, I was fortunate enough to obtain a three-month painting contract with my resident acquaintance. Upon fulfillment of the contract, I regrettably found myself unemployed with no further prospects. Securing gainful employment is of paramount importance, as failure to do so would result in derogatory status. Currently, I am idle and largely reliant on my peers’ benevolence. Being compatriots, we share a mutual bond whereby those with increased financial resources resulting from remittances or daily labor generously contribute to the collective, with such communal acts cementing the fraternal and sororal relations within our group.

4.2.3. Self-employment

Interviews were conducted with officials and refugees in the host community and revealed that certain refugees were involved in petty trading. These refugees were found to operate informal enterprises that offered services such as hairdressing, laundry, translation, rental brokerage, plumbing, mechanics, retail, leisure, hospitality, and construction. Some of these enterprises have been established under Ethiopian licenses. The size and productivity of these refugee-owned enterprises vary, and they face different levels of challenges owing to a scarcity of capital and an unfavorable working environment, including limited rights to work. These findings are in line with those reported by Omata and And (Citation2013) and Brown et al. (Citation2018), who examine the role of the informal economy in refugee livelihoods. Brown et al. (Citation2018) further stated that the economies of refugees are assimilated into a city’s economy and make a significant contribution.

4.2.4. Support from relatives and friends

Eritreans have traditionally been assimilated into the Ethiopian population. They are widespread throughout the nation, not only in Addis Ababa. As a result, Addis Ababa is frequently home to the relatives and/or friends of Eritrean and Somali refugees. The same is true for Somali refugees, since the Bole Michael area is home to a sizable population of Ethiopian Somalis. They adhered to the same religious beliefs, traditions, practices, and values. As a result, some Eritrean and Somali refugees first arrived in Ethiopia at the insistence of their family or friends who lived there. These people are known as guarantors by urban refugees, who stay with them for many years until they find employment. In a study carried out in Kampala by Omata and And (Citation2013), in Addis Ababa by Brown et al. (Citation2018), and by Fekadu et al. (Citation2022), similar patterns of results were attained. They discovered that the livelihoods of refugees from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Congo, and Somalia are primarily based on ethnic relationships.

4.2.5. Humanitarian assistance

According to interviews conducted with officials of the Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs (ARRA), urban refugees consist of individuals who have decided to reside independently in urban regions without the direct support of local or international organizations. This group also includes those who require ongoing medical care, travel to cities for pleasure, or come from nations with insufficient refugee populations to warrant camps. It is crucial to remember that only refugees who have chosen to live independently in cities without the assistance of any organization receive aid or direct support. In contrast, other categories of refugees are given monthly assistance, which is often in the neighborhood of 2000 birr ($64.52) per month. Furthermore, in addition to monthly support, these refugees can also request financial assistance from friends and family living abroad, as the amount they receive is insufficient to cover their monthly expenses.

The provision of humanitarian aid varies across different types of organizations. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides monthly cash assistance to all enrolled urban refugees. Additionally, several governmental and non-governmental organizations, such as ARRA, NRC, DICAC, JRS, and ZOA, offer livelihood aid in the form of business grants, loans, and skill development. According to Brown et al., humanitarian aid from organizations provides a source of income for refugees living in Addis Ababa. Similarly, most refugees rely heavily on supplies of food and non-food items as well as cash aid from the government or assistance from humanitarian groups (World Bank, Citation2018). Refugees’ engagement in the labor market is minimal; as a result, they rely significantly on humanitarian aid.

4.3. Livelihood challenges for refugees in Addis Ababa

4.3.1. High cost of living

Participants indicated that Addis Ababa had a high cost of living. Housing is quite expensive, costing between 64.52 and 161.29 US dollars (2000 and 5000 birr), respectively. However, food prices remain a challenge. In line with this, a Somali refugee described himself as follows.

Living in Addis Ababa was challenging. Even those who live permanently and have permanent jobs face significant challenges in coping, let alone the urban refugees. No matter how much money you make, food, lodging, and other services are very expensive. Occasionally, we receive money and make timely rent payments. Otherwise, we typically borrow money from friends or family to pay for housing and food.

Participants in the study observed that it is challenging for an individual urban refugee to manage rising prices and survive in Addis Ababa unless that person has a relative or friend who can support him or her. Owing to the high cost of housing, most metropolitan migrants live in groups to share expenses. According to Brown et al. (Citation2018), refugees in Addis Ababa experience economic hardship and present problems to local and international authorities.

4.3.1. Cultural adaptability and language barriers

Eritrean and Somali refugees are more likely to integrate into the host community than other nationals because they share the same culture, language, way of life, and economic activities. Language remains a barrier to communication with the hosts. As a result, they occasionally use symbols to pay for things in host stores. Many refugees cited the inability to communicate fluently in Amharic as an obstacle to work and widespread assimilation. An in-depth interviewee, who was an Eritrean refugee, said,

On a particular day, I ventured out to procure footwear and invoked the Eritrean term “udd” to refer to the material. The proprietor of the store, inquiringly stated, “What do you mean, I do not understand?” Might you refer to Sunday? Despite employing symbolic language, the proprietor was unable to grasp my intentions. Subsequently, the availability of the desired material is determined. Upon seeing the material, I indicated it and procured it from my proprietor. Once again, the proprietor was unable to discern the meaning. Ultimately, I sought permission to enter the store to demonstrate the specific material visually. The proprietor acquiesced, and I proceeded to exhibit the material, tendered the payment, and then returned home. This impediment is common among refugees, particularly those from rural environments and recent arrivals. However, some of them have acquired proficiency in Amharic over time through interactions with acquaintances and relatives residing in Addis Ababa.

4.3.2. Refugees’ low self-esteem

Alternative avenues exist for engaging in diverse economic pursuits and income generation. Nevertheless, refugees demonstrate diminished self-regard, despondency, and reduced resolution of labor. They feel disheartened and believe that the situation in Ethiopia will not evolve to facilitate a superior existence in their original or current settlements, ultimately resulting in them waiting for financial assistance from acquaintances and leading an inert lifestyle. One member of the Somali refugee focus group expressed this notion.

The Ethiopian people are fortunate to have attained a state of peace, a privilege that we have yet to achieve. The absence of peace, freedom, and economic stability left me feeling despondent with no concrete plans for the future. It remains unclear whether my circumstances will improve in the future. To improve my situation, I am considering the possibility of seeking assistance in a European country, the United States, or another nation. Regrettably, the future for myself and my family appears bleak.

This elucidation was offered by a Somali refugee who initially migrated to Ethiopia, accompanied by his family, and endured an excess of 12 years in the camp. While conducting this research, he resided in Addis Ababa as an urban refugee. He expounded on his circumstances in the following manner.

Twelve years ago, I migrated from Somalia to Ethiopia and embarked on an unauthorized move to Sudan. During my stay in Sudan, I was confronted with a dearth of services provided to refugees, which made it an unpleasant experience. Conversely, the provision of services in Ethiopian refugee camps is better. In Ethiopia, I secured a job as a waiter before relocating to Egypt in search of improved economic opportunities, with the ultimate aim of transforming my family’s standard of living. Unfortunately, my tenure in Egypt was abruptly truncated by my detention and subsequent deportation to Ethiopia. Since then, I have been domiciled in Ethiopia, specifically in the Somali region, where I have worked in various towns, including Dire Dawa and Jigijiga. However, my life has remained largely unchanged, and I am presently residing in Addis Ababa, where I still rely on remittances to sustain myself.

Most refugees experience a sense of despair, struggle with diminished self-worth, view themselves as migrants, and lack opportunities to transform their lives positively.

4.3.3. Psychological instability and mobility

Urban refugees, as a whole, specifically those from Eritrea, manifest a reduced degree of dedication to participating in long-term employment opportunities in Addis Ababa. Their intended use in Ethiopia is primarily as a transit country en route to other African nations, including Europe, the USA, and Australia. A participant from Eritrea conveyed the following sentiments during focus group discussions:

My brother currently resides in Canada and seeks refuge from Ethiopia under the auspices of the UNHCR and other NGOs. While he encouraged me to follow suit, navigating bureaucratic channels and securing the necessary documentation to leave Eritrea lawfully remain formidable challenges. Even in instances of severe health crises, individuals must provide a substantial sum of 200,000 birr (equivalent to 6,452 USD) as collateral before departing from medical treatment in Sudan. Regrettably, this avenue of recourse is presently blocked, rendering international travel unfeasible.

As such, my sole recourse was to seek asylum in Ethiopia and register as a refugee. Three months ago, I spent 45 days at a refugee camp before relocating to an urban area. My brother is in the process of obtaining a visa for my emigration to Canada, which, barring any unforeseen complications, should occur within a year.

Urban refugees who participated in this study expressed a strong desire to relocate abroad. From a psychological standpoint, these individuals do not feel prepared to seek employment in Addis Ababa. Their ultimate goal is to leave Ethiopia and follow in the footsteps of Eritrean refugees who have found economic prosperity and a higher quality of life abroad. To achieve this objective, they are willing to pursue both legal avenues with the aid of friends or family members as well as illegal means such as traveling through Libya or South Africa. During the focus group discussion, the Somali participant offered the following insights:

I am currently inactive. Co-habitation with acquaintances is my current living arrangement, and we subsist on financial remittances from overseas relatives. My focus is on the conclusion of the visa process. Once finalized, my intention was to travel overseas to provide assistance to my family as well as my compatriots and associates. I am not inclined to pursue local employment opportunities in Addis Ababa. A monthly stipend of 100 dollars, frequently disseminated by an individual, suffices to meet my needs.

4.3.4. Conflict and security challenges

Most refugees hailing from Somalia and Eritrea have demonstrated an admirable capacity to coexist harmoniously with their host communities, assimilating and embracing the customs and traditions of the latter. Drug and alcohol addictions are exceptions. However, some of them frequently use alcohol and return to their families or relatives’ houses. Sometimes conflicts exist between refugees and the host community. An in-depth Eritrean interviewee stated:

Eritrean refugees who are specifically from Asmara are good; they have good communication skills, focus more on work than alcohol, live peacefully with their friends, and have better interaction and communication skills. However, refugees from rural areas sometimes face challenges living with their urban refugee friends and host communities. They do not easily communicate with the host community, and sometimes conflicts exist between refugees and host community members. In addition, some refugees have been receiving more remittances from their relatives and friends. They also spent time consuming alcohol. They do not care about anything; rather, they enjoy it every day and hope to go abroad. They did not want to work in Addis.

The study participants reported that, due to recurrent conflict and violence perpetrated by a subset of Eritrean and Somali refugees, the police resorted to categorizing and construing all urban refugees as potential threats. During the focus group discussion held in Addis Ababa, a Somali participant expounded on the manner in which the police responded to this particular issue.

Policemen do not want to see us outside at night. Sometimes we used to have tea or coffee together with our friends, and when we met them, the policemen would say, “You guys could be from the bar.” They insisted on it and ordered us to get in immediately with an oral warning, if not with a plastic stick.

In a comparable manner, Crea’s et al. (Citation2016) investigation delved into the challenges confronting urban refugees in South Africa as they endeavored to secure sustainable means of subsistence. These challenges include communal unrest, excessive population density, xenophobic attitudes, trepidation, state-sanctioned exploitation, and markets that are oversaturated with small-scale enterprises.

4.3.5. Theft and robbery

Urban refugees encounter several obstacles, including theft and robberies. Since hosts frequently observe refugees receiving remittances in foreign currency, it is assumed that Eritrean urban refugees are wealthy and possess a greater amount of money. Consequently, a small number of individuals from the host community attempt to steal their mobile phones, valuables, or money, both during the day and night. During an extensive interview, one of the Eritrean participants recounted their experiences of theft and robbery in the following manner:

The few hosting community members in our residential area consider Eritrean refugees to have more money. I know that some Eritreans lead luxurious lives as a result of the remittances they receive from different sources. However, most refugees live subsistence lives. They receive money from abroad and use it for housing and food production purposes. No additional money is left beyond this. As a result of this misperception, gangsters came to our rental houses and hanged refugees most frequently, just to snatch our money and mobile phones. They use magic. They just come and hang you peacefully, saying “hi.” Thus, we do not know how to obtain money from our pockets. However, this is a significant challenge. Most of my friends, including me, have faced such problems in one way or another.

A Somali in-depth interviewee who came to Ethiopia from Somalia with his family added the following:

As a collective cohort comprising myself, my mother, my sister, and a younger sibling, we embarked on a journey to Ethiopia. We derive our primary means of sustainability from remittances. A certain relative of ours who resides in Canada dutifully dispatches 100–150 dollars on a monthly basis for the benefit of our entire household. Subsequently, we proceeded to extract funds in a rotating fashion, with myself, my brother, and my sister taking turns. One fateful day, my younger brother was tasked with procuring remittances from a bank. However, upon his return, the miscreants accosted him and seized the entire sum. We were left with nothing to subsist on as this was our sole monthly endowment. We then appealed to our landlord to be patient while we endeavored to acquire the requisite funds. Concurrently, we implored our relatives to dispatch the sum. In mere days, he obliged us to pay a similar amount.

4.3.6. Legal and policy frameworks

The implementation of legal and policy provisions regarding refugee livelihoods has revealed a significant gap. Proclamation 1110/2019 provides access to services, wage-earning jobs, engagement in agriculture, industry, and small and micro enterprises, as well as skills training and education. However, access to employment remains limited due to the lack of a legal right to work, which poses a significant obstacle to securing the livelihoods of refugees. Although providing an affordable and accessible work permit system for refugees is critical, it is not sufficient to help establish a stable livelihood. The absence of labor protection for refugees results in workplace discrimination, such as low wages, withheld wages, payments in the form of “incentive money” instead of regular salaries, and arbitrary termination of employment. Additionally, urban refugees encounter problems related to a lack of access to business licenses, which limits the reinvestment and growth potential of most refugee-run businesses operating under Ethiopian business licenses. The findings of the study are similar to those of Tulibaleka et al. (Citation2022), who discovered that despite the Ugandan government’s refugee-friendly policies, protracted refugees face challenges such as limited access to labor market integration, youth employment, issues with urban integration, and environmental stress.

4.4. Opportunities for refugee livelihood enhancement in Addis Ababa

4.4.1. Legal and policy environment

The policy that granted refugees permission to reside in urban areas without the benefit of employment or other privileges is commonly referred to as the out-of-camp policy. They were not authorized to engage in any form of work, despite being allowed to dwell in urban areas. Conversely, urban-assisted refugees travel to the city for specific purposes and receive assistance from UNHCR.

During the Obama Summit in New York in 2016, the Ethiopian government committed nine pledges, resulting in policy modifications. These pledges provide refugees with the right to work, business licenses, driver qualification certification licenses, banking services, education, healthcare and other essential services. These rights have made life easier for urban refugees. The new refugee proclamation was endorsed and approved by the House of Representatives in February 2019, although it has yet to be fully implemented.

The Proclamation presents refugees with additional choices to enhance their independence and promote self-sufficient and sustainable livelihoods. Urban refugees now have access to education, the right to work, the right to association, freedom of movement, the right to acquire and transfer property, driver qualification certification licenses, banking services, telecommunications services, rationing, and vital event registration.

These and other rights are expected to empower urban refugees to decrease their dependency, increase their self-sufficiency, and improve their livelihood. The right to work allows refugees to search for employment, receive wages, and enhance their standard of living. Business and driving licenses also facilitate interactions and integration with local communities. Furthermore, freedom to move allows them to locate an area that is suitable for them to work and reside in according to their preferences and abilities. Nonetheless, these rights are not entirely observed in practice, making it difficult for refugees to sustain their livelihood.

4.4.2. Host-urban refugees cultural similarity

The people of Eritrea and Somalia shared strong bonds with Ethiopia. These groups exhibit analogous societal norms, cultural practices, linguistic patterns, and socioeconomic traits. Somali urban refugees residing in Addis Ababa are readily able to establish social connections with Somali ethnic groups within Ethiopia. They can effortlessly communicate with their counterparts, assimilate communal customs, and settle into new abodes. The same holds true for urban refugees originating from Eritrea, who share similar languages, religions, ways of life, and social structures with the Ethiopian people, especially the Tigrawai ethnic group (of Tigray). This mutual likeness enables them to interact with the local community and explore opportunities for livelihood. Most of these refugees had proficient knowledge of Amharic and other vernacular languages. During the focus group discussions, Somali and Eritrean participants expounded on this topic in the following manner:

We are fortunate to have come and lived in Ethiopia. We feel like we live in our own countries. We examine skin color, language, culture, religion, and other social contexts. It is almost the same. If an outsider evaluates us, they cannot easily identify that we are refugees. This helps to reduce the impact of a sense of loneliness. We believe that we live with friends, relatives, and similar people. However, friends and relatives who visited other European countries told us that they were discriminated against, stereotyped, and ridiculed. This is challenging because it undermines refugees’ personalities. However, nothing is considered a challenge in Ethiopia.

There are 26 refugee camps in Ethiopia. To promote interaction between refugees and host communities, the government deliberately placed refugees in camps where surrounding host communities shared similar cultural backgrounds. For instance, Eritrean refugees predominantly reside in camps in the Tigray and Afar regions, whereas Somali refugees tend to reside in camps in Ethiopia’s Somali National Regional State. This measure is intended to enhance the relationship between refugees and hosts and, in turn, improve relations between neighboring countries such as Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia. In pursuit of their livelihood objectives, refugees rely heavily on social capital, a social resource drawn upon through networks, connections, membership, and relationships of trust. These findings are consistent with other studies that have highlighted the integral role of social capital in the livelihoods and integration of urban refugees (for example, Brown et al., Citation2018; Fekadu et al., Citation2022; Fisseha, Citation2019; Omata & And, Citation2013; Wogene, Citation2017).

5. Conclusion

This research investigates the livelihood strategies adopted by refugees residing in urban areas, with a focus on Eritrean and Somali refugees in Addis Ababa. It uses a sustainable livelihood perspective to explore the context of vulnerability, livelihood strategies, challenges, and opportunities. Ethiopia, as a part of the Horn of Africa and East Africa, has been mentioned as the main producer and recipient of refugees. It has been receiving refugees and asylum seekers who flee adversity in their home countries because of its open-door policies. Most flee for conflict, political, or economic reasons and aspire to resettle in Western countries. The country has also witnessed a high level of internal displacement. The population of refugees in Addis Ababa showed a two-fold increase following the conflict that ensued in northern Ethiopia. This can be attributed primarily to the self-relocation of Eritrean refugees from the camps in Tigray. Given the possibility of an escalation in the number of displaced persons, including refugees, inquiries into their livelihoods, both generally and in urban settings, are of utmost significance.

This study identified remittances, paid work, self-employment, assistance from family and friends, and humanitarian assistance as major sources of livelihood and income for Somali and Eritrean refugees in Addis Ababa. The primary observation derived from this research is that a considerable number of urban refugees with relatives in Europe, Australia, and North America rely significantly on remittances to fulfill their essential necessities. This study shows that urban refugees have dealt with a variety of sociocultural and economic challenges. Refugees encounter various obstacles when adapting to a new culture. These barriers include the exorbitant cost of living and hindrances associated with cultural assimilation such as language barriers, low self-esteem, psychological instability, mobility restrictions, conflict and security issues, violence, theft, and robbery. Refugees face these hindrances as their primary challenges.

The study also highlights opportunities for urban refugees to pursue their livelihoods in Addis Ababa. The similarities in culture and language, as well as the presence of a supportive policy framework, are opportunities for better social and economic integration. The country has made progress in granting rights to refugees; however, in practice, its implementation has been limited. One of the rights that refugees have under the 2019 Refugee Proclamation is access to a driver’s qualification certification license and financial and telecommunications services. They also have the right to obtain and transfer property rights, as well as the right to access education, healthcare, employment, and associational rights. Refugees do not enjoy these rights. Most urban refugees live and interact with the host community with ease as they share a common culture and language, although some face language barriers.

The findings of this study provide insight into the livelihood dynamics of refugees in cities. The findings of this investigation partly complement those of earlier studies such as Aida (Citation2017), Brown et al. (Citation2018). The last two studies attempted to understand the concept of “refugee economies” in general based on their studies in Addis Ababa. This study contributes to our understanding of livelihood strategies, challenges, and opportunities for refugees in cities in the Global South. The scope of this study was limited by its small sample size, limited scope, and exploratory qualitative methodology, which did not allow inferences about urban refugees using large representative samples. Despite the relatively small sample size, this study makes significant contributions toward comprehending livelihood strategies, obstacles, and prospects for refugees. Further studies could assess the long-term effects of refugees on the city and the determinants of their livelihoods.

Therefore, a key refugee policy priority should be planning for the sustainability of urban refugee livelihoods. It is imperative to develop and implement all-encompassing strategies to strengthen and ensure the sustainability of refugees’ livelihoods. In addition, grounding any such strategy in the specific perspective and agency of refugees is of utmost significance. Moreover, it is crucial to emphasize the significance of refugee-host community relationships and social integration as essential elements of livelihood strategies, acknowledging that the livelihoods of refugees differ from those of non-refugees and supporting the livelihoods of refugees through advocacy, durable solutions, and innovative approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable contributions.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) made no mention of any potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fisseha Meseret Kindie

Fisseha Meseret Kindie is a PhD candidate in development studies at Addis Ababa University. He is a program officer at the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). He participates in the protracted displacement project funded by UKRI through the GCRF (February 2020–October 2023) and coordinates the project’s participatory forum component in Ethiopia.

Wondimu Abeje Kassie

Wondimu Abeje Kassie is an assistant of urban planning at the College of Development Studies at Addis Ababa University. He is also a practicing urban development planner and has been working on several planning and development projects and studies. His research areas focus on urban development spatial planning, regional development, urban resilience, low-carbon transport, green urban development and urban water, urban heritages, migration and urban dynamics.

Engida Esayas Dube

Engida Esayas Dube is an assistant professor of regional and urban studies at Dilla University, Ethiopia. His research focuses broadly on urban and regional studies, forced displacement, migration, urban informality, and livelihoods. Dr. Dube is Ethiopia’s country academic lead and co-investigator on a protracted displacement project funded by UKRI through the GCRF (February 2020–October 2023).

References

- Adugna, G. (2021). Once primarily an origin for refugees, Ethiopia experiences evolving migration patterns. Migration Policy Institute.

- Aida, E. (2017). The Out of Camp Scheme for Eritrean Refugees: The impact of the Scheme on their livelihood and Integration with the Host Community, MA Thesis in Social Work. School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- ARRA. (2011). Refugee population update. Addis Ababa.

- Assefaw, B. (2006). Conflict and the refugee experience: Flight, Exile and Repatriation in the Horn of Africa. London.Routledge.

- Brown, A., Mackie, P., Dickenson, K., & Tegegne, G. 2018. “Urban refugee economies”Working paper. Addis Ababa,

- Bryman, A. (1992). Quantitative and qualitative research: further reflections on their integration. In J. Brannen (Ed.), Mixed Methods: Qualitative and quantitative research (pp. 57–18). Avebury.

- Carney, D. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods:What contribution can we make?. DFID.

- Catherine, D. (2007). A practical Guide to research Methods: A User Friendly Manual for Mastering Research Techniques and Projects (3rd ed.). Oxfordshire.

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. 1991. Sustainable livelihoods for the 21st Century. IDS Discussion Paper 296, Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Brighton.

- Crea, C., Loughry, M., O’Halloran, C., & Flannery, G. J. (2016). Environmental risk: Urban refugees’ struggles to build livelihoods in South Africa International social work. International Social Work, 1(3), 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816631599

- CSA. 2018. Population Projections for Ethiopia: 20019- 2039. AddisAbaba

- De Vriese M.(2006). Refugee livelihoods: A review of the evidence, EPAU/2006/04. UNHCR.

- Farrington, J., Ramasut, T., & andWalker, J. (2002). Sustainable livelihoods approaches in urban areas: General Lessons, with Illustrations from Indian cases, department for Infrastructure and economic Cooperation. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

- FDRE. (2019). Ethiopia refugee Proclamation No. 1110/2019. Addis Ababa: Federal Negarit Gazette.

- Fekadu, A., Rudolf, M., & Mulu, G. (2022). A matter of time and contacts: Trans-local networks and long-term mobility of Eritrean refugees. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090155

- Fisseha, M. K. (2019). Challenges and opportunities of urban refugee livelihoods:The case of Addis Ababa, MA dissertation in regional and local Development Studies. College of Development Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- Guesh, T. W. 2020. Food Security and Livelihoods Challenges of Urban Refugees in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, MSc Thesis in Food Security and Development, College of Development Studies, Addis Ababa University

- Jacobsen, K. (2002). Livelihoods in conflict: The pursuit of livelihoods by refugees and the impact on the human security of host Communities.”International migration. International Migration, 40(5), 95–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00213

- Jacobsen, K., Ayoub, M., & Johnson, A. (2014). Sudanese refugees in Cairo: Remittances and livelihoods. Journal of Refugee Studies, 27(1), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fet029

- Jacobson, K. (2006). Refugees and asylum seekers in urban areas. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(3), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fel017

- Kalof, L., Dan, A., & Dietz, T. (2008). Essentials of social research. Open University Press.

- Levine, S. 2014. How to study livelihoods: Bringing a sustainable livelihoods framework to life. ODI, https://securelivelihoods.org/wp-content/uploads/How-to-study-livelihoods-Bringing-a-sustainable-livelihoods-framework-to-life.pdf (Retrieved June , 2021).

- Mbiyozo, A. (2023). Record numbers of displaced Africans face worsening prospects, Institute of security Studies (ISS) Today 16 February. https://issafrica.org

- Mekonnen, T. (2019). Access to livelihood opportunities and Basic services among urban refugees in Addis Ababa: Challenges and opportunities. Ethiopian Journal of Development Research, 41(2), 85–118.

- Mistri, A., & Das, B. (2020). Environmental change, livelihood issues and migration. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8735-7

- Omata, N., & And, K. J. 2013. “Refugee livelihoods in Kampala, Nakivale and Kyangwali refugee settlements patterns of engagement with the private sector.” Working Paper Series No. 95, Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford.

- Rohwerder, B. 2016.Sustainable livelihoods in Ugandan refugee settings (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1401). GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- Tulibaleka, P. O., Tumwesigye, K., & Nakalema, K. (2022). Protracted refugees: Understanding the challenges of refugees in protracted refugee situations in Uganda. Journal of African Studies and Development, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5897/JASD2021.0647

- UNHCR. 2017.Global focus: UNHCR operations worldwide. http://reporting.unhcr.org/node/5738.

- UNHCR. (2022). Ethiopia: Urban refugee population in Addis Ababa (as of November 2022). UNHCR.

- UNHCR. (2023) . Ethiopia refugee and asylum seekers (December 2022).

- Wake, C., & Barbelet, V. (2020). Towards a refugee livelihoods approach: Findings from Cameroon, Jordan, Malaysia and Turkey. Journal of Refugee Studies, 33(1), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez033

- Wogene, B. M. 2017.Assessing the Local Integration of Urban Refugees: A Comparative Study of Eritrean and Somali Refugees in Addis Ababa, MA Thesis in International Relations and Diplomacy, School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University.

- Wondewosen, L.1995. “The Ethiopian refugee Law and place of women in it.”Forced Migration Online. Retrieved from: http://refugees.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/USCRI-Report-Forgotten-Refugees.pdf.

- World Bank. (2018). A skills survey for refugees in Ethiopia, informing durable solutions by micro data. The World Bank Group.

- Zelalem, T. (2017). Delimiting the normative terrain of refugee protection: A critical appraisal of the Ethiopian refugee Proclamation No.409/2004.In. In B. Yonas (Ed.), Refugee protection in Ethiopia International Law Series (pp. 31–98). Addis Ababa University.