?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, two important antiracist movements, namely, Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate, swept across the United States between 2020 and early 2021. Social media platforms such as Twitter have become an increasingly important tool for mobilizing social movements. To gain a comprehensive understanding of social media users’ attention and reactions to racial injustice during this unprecedented time, the current study explores and compares the discursive characteristics of Twitter discussions of these two movements: their volume changes, word diversities, and moral and emotional sentiments. By analyzing the text of approximately 5 million tweets from April 2020 to April 2021 using a dictionary-based word count method, this research showed that compared to #BlackLivesMatter, #StopAsianHate was less diverse, more morally charged, and less positive in emotional sentiment. Additionally, #StopAsianHate contained stronger moral emotions than #BlackLivesMatter. The study connects these distinct characteristics to the two movements’ differences in their objectives, progress and participants’ demographics and provides implications for effective antiracist activism on social media.

A turbulent history characterized 2020—amid the COVID-19 pandemic that took 4.2 million lives worldwide, racial tensions continued to escalate. With COVID-19—first reported in Wuhan, China—spreading across the United States, the former President Trump’s use of racist terms such as “Wuhan Virus” and “Kong Flu” placed blame on Asians for causing the pandemic, resulting in a proliferation of attacks targeting this group. The mass shooting of eight people, including six Asian Americans, at three Atlantic spas further gave rise to the Stop Asian Hate (SAH) movement that aims to combat discrimination against Asian people. Meanwhile, the police violence towards an African American George Floyd reignited the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which promotes anti-discrimination efforts for black people. Consequently, protesters from both the BLM and SAH movements took to the streets across the United States to fight against racial injustice.

When face-to-face interactions are limited in the pandemic, social media plays a particularly important role in informing, uniting, and motivating individuals in these movements (Grant & Smith, Citation2021). On social media platforms such as Twitter, users can continuously generate, sustain and spread information about protests. Therefore, social media serves as a useful tool to gauge public attention and sentiment toward these movements. To date, most social movement studies have focused on a single movement, such as the Arab Spring (e.g., Lotan et al., Citation2011), Occupy Wall Street (Caren & Gaby, Citation2012), and BLM (Clark, Citation2019). The (re)occurrence of BLM and SAH in approximately the same year allows us to explore and compare their discursive characteristics. An investigation of online conversations about the two largest racial movements in recent years can offer a comprehensive illustration of social media users’ attention and responses to racial injustice.

Furthermore, studying movement discourse on social media can enhance the understanding of the applicability and constraints of social media with respect to antiracist activism. Although social media is widely used in contemporary social movements, it is believed to be more suitable for certain movements. For example, researchers have pointed out that some unique characteristics of BLM, e.g., focusing on tangible issues such as police brutality, make BLM a topic well suited for online activism (Freelon et al., Citation2016). Although SAH shares BLM’s anti-racist aim, the movements differ in their specific objectives, participants’ demographics, and movement stages. Therefore, comparing SAH and BLM can reveal how these unique features influence the applicability of social media in activism. This comparison can also help organizers tailor online messages to each movement’s unique attributes.

Thus, this research compares the discourses of BLM and SAH, specifically focusing on word diversity, emotional and moral sentiment. Examining these aspects can present a picture of the distinct themes and opinions emerged in the online conversations related to the two movements, as well as the public’s emotional reactions and highlighted values. We expect that the social media discourse related to BLM will exhibit greater word diversity than SAH due to its broader range of subtopics and counter-protests. In terms of emotional sentiment, we predict that BLM’s sentiment will be more positive than SAH, because BLM has progressed to a later stage where successes have accumulated. We also expect to observe differences in moral sentiment in the discourse due to the cultural differences in moral values of participants. To unravel the rationale, we begin with a discussion of the role of social media in social movements.

1. Social media and diversity in social movement discourse

In the information age, social media has demonstrated remarkable potential in facilitating social changes, giving rise to concepts like “activism 2.0” or “social movement 2.0” (Foust & Hoyt, Citation2018) which denote activism based on digital platforms. Using social media for activism has clear advantages: from a functional perspective, the speed, ease of use, and interactivity of social media enable swift information generation and dissemination. This increases awareness about social issues and publicizes collective actions (Foust & Hoyt, Citation2018). Social media also forms a “decentralized” network where users from various backgrounds can self-generate information (Frangonikolopoulos & Chapsos, Citation2012), thereby breaking the control of traditional gatekeepers over information flow and adding to the diversity of conversations. Furthermore, scholars argue that social media is more than a communication tool for social movements; it contributes to shaping a collective identity (see Foust & Hoyt, Citation2018 for a review). In decentralized networks, individuals work together to create symbols and meanings for a given movement. Through this process, a collective identity is formed and expanded (Taylor & Whittier, Citation1992). Twitter hashtags linked to social movements are good examples of symbols with meanings that are codefined and refined by participants (Papacharissi, Citation2016).

At the same time, social media networks are not entirely decentralized. Scholars have argued that social media activism can be likened to “choreography”, wherein leaders act as choreographers. But they are less visible and were probably reluctant initially but nonetheless play key roles in “setting the scene for the movement’s gatherings in public space, by constructing common identifications and accumulating or triggering an emotional impulse toward public assembly” (Gerbaudo, Citation2012, p. 13). The central role of these leaders is likely to undermine the diversity that social media platforms are expected to foster within a movement’s discourse. For example, in the BLM movement, researchers found that Black celebrities exploited their connections to fans and their high visibility to discursively define the movement (Duvall & Heckemeyer, Citation2018). Opinion leaders, such as celebrities on social media networks, could easily sway conversations and change a movement’s agenda.

2. Emotional and moral elements in social movements

Movement discourses are often emotionally and morally charged because social movements involve moral judgments. Social movements typically originate when individuals witness or experience violations of their moral principles (a “moral shock”; Goodwin & Jasper, Citation2006). Witnessing moral transgressions induce strong emotional reactions (Jasper, Citation2011). For example, BLM protests are repeatedly ignited by instances of police hurting innocent Black victims, eliciting anger and fear within the Black community. Furthermore, participants in social movements don’t merely react passively to these moral breaches, they collectively take action to uphold moral values and achieve moral goals for society (Goodwin & Jasper, Citation2006), for example, protesting against injustices to safeguard the value of equality and advocate for the marginalized. In essence, a social movement serves as a means to articulate, practice, and fulfill a group’s moral beliefs.

Emotions are just as prevalent as moral reactions in social movements. They can be present inside or outside social groups. For example, among group members, one can observe compassion for victims, trust in movement leaders, and pride in their collective identity. In contrast, outside these groups, one can observe anger toward social injustice, fear of repression, and hatred toward an opposing group. These emotions not only reflect collective feelings but also serve as primary drivers for social movements, motivating actions and building connections among group members (Jasper, Citation2011).

Because emotion often responds to current conditions, it is logical to assume that different emotions may be more salient during different stages of a movement. Notably, social movements generally progress through four stages: emergence, coalescence, bureaucratization and decline (Christiansen, Citation2009). In the emergence stage, a small group of people shares frustration and discontent, but no organized actions occur (Christiansen, Citation2009). Later, a social organization is formed to initiate the social movement and raise people’s awareness of the central issue. In the coalescence stage, participants become aware of the group, identify those accountable for injustice and formulate strategies and mass demonstrations such as protests and marches. Once the movement has gained prominence, formal institutions come into play to fulfill long-term objectives and to maintain people’s interest in and the publicity of the movement. This marks the onset of the bureaucratization stage. Ultimately, each movement declines due to repression, cooptation, success or failure (Christiansen, Citation2009).

Each stage may emphasize different emotions. For example, in early stages, it is plausible that negative emotions such as anger, fear, shame and disgust are more prevalent than positive emotions because negative emotions are typical responses evoked by the appraisal of harmful events that give rise to such a movement (e.g., hate crimes; Roseman et al., Citation1990). Additionally, from a functional perspective, organizers may strategically emphasize negative emotions in a movement’s initial stages to push the movement forward. This is because negative emotions, such as anger, create a strong action tendency to oppose or resist (Frijda, Citation1987) and thus have great potential for fueling actions. Also, individuals tend to pay more attention to negative stimuli (Rozin & Royzman, Citation2001). Highlighting negative emotions can increase outsiders’ attention to issues, which may help recruit new members.

In contrast, positive emotions such as joy, pride, and hope may be more likely to emerge during the coalescence and bureaucratization stages when a group becomes relatively more permanent and structured. This change occurs because, first, the shared goals and victories of mass actions in the earlier stages can bring joy and pride to group members. Second, from a strategic perspective, the expression of positive emotions is necessary to sustain ongoing participation in mobilizations because they make a social movement pleasurable for its participants (Jasper, Citation1998). Positive emotions can continue to energize and boost group efficacy, creating emotional bonds that bring a group together (Jasper, Citation2011). Without these benefits, members may be overwhelmed by anger, fear and hopelessness. Ultimately, positive emotions work with negative emotions as a “moral battery” to drive a movement forward (Jasper, Citation2011).

Given the prevalence of moral and emotional elements throughout mobilizations, it is vital to examine the moral and emotional sentiments of public discussions of antiracist social movements to reveal how sentiment varies in movements with different stages and other characteristics so that organizers can better mobilize audiences by tuning into their emotions and moral concerns. Social media discourses on Twitter have provided an excellent avenue for studying the attention and reactions of social media users who constitute a solid network in recent antiracial movements (Freelon et al., Citation2016).

3. #BLM and #SAH

The study focuses on the Twitter discourses of BLM and SAH, two movements that heavily rely on Twitter and (re)occurred from 2020 to early 2021. The BLM movement centers around police brutality and racially motivated violence toward Black people. It began in 2013 after George Zimmerman was acquitted of the 2012 murder of African American teenager Trayvon Martin. The movement gained national prominence following the police killing of Michael Brown in 2014. It reached global attention when a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd on 25 May 2020, which led to the largest protest movement in US history (Buchanan et al., Citation2020).

As COVID-19 spreads across the US, Asian people become targets of blame, hatred and violent attacks. The attacks eventually led to the emergence of SAH, an antiracist movement focusing on discrimination against Asians. Stop AAPI Hate, an anti-Asian hate reporting center, was founded and became a major voice for SAH on social media. SAH was brought to the national public’s attention in March 2021 following a shooting that killed eight people, including six Asian women, in three Atlanta spas. SAH rallies soon swept across the country in response to the shooting.

Social media serves as a hotspot for conversations about BLM and SAH. In response to incidences of racism, hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter, #BLM, #StopAsianHate and #SAH were created and went viral on Twitter. When specific events occur, the use of #BlackLivesMatter increases drastically. For example, the usage of the hashtag reached a record level with approximately 3.7 million mentions on Twitter per day from May 25 to 7 June 2020, following the death of George Floyd (Anderson et al., Citation2020). These online conversations ultimately led to offline protests. Evidently, throughout the BLM movement, social media has helped build connections and coalitions, mobilize participants and tangible resources, and amplify alternatives to mainstream narratives (Mundt et al., Citation2018).

In addition to their reliance on social media, SAH and BLM share other commonalities; for example, both targeting racial injustice and overlapping temporally. For this reason, it can be expected that many activists endorse both movements. It is also argued that SAH, as an emerging movement, could learn a great deal from BLM (Chao, Citation2021; Wang, Citation2021). Meanwhile, SAH differs from BLM in several ways that may lead to different online conversations. Firstly, the scale of the BLM movement is larger than that of SAH. BLM is believed to be the largest movement in US history—15 to 25 million people in the United States have participated in George Floyd protests (Buchanan et al., Citation2020). The large scale of #BlackLivesMatter is also reflected in its many subtopics, such as #Ferguson, #ICan’tBreathe, and #TheyGunnedMeDown, and it generates prominent counterprotests in which protestors generate hashtags, such as #AllLivesMatter and #BlueLivesMatter, to compete with #BLM on Twitter (Carney, Citation2016). Compared to #BLM, #SAH does not have many subtopics and clear counterprotests. Secondly, SAH and BLM differ in the demographics of their most prominent participants. As expected, African Americans are the major contributors to the BLM conversation (Olteanu et al., Citation2016). White people also play an active role in the movement (Olteanu et al., Citation2016). In addition, members of groups oppressed for reasons other than race, such as women and LGBTQ people, are also outspoken advocates for the BLM movement (Nummi et al., Citation2019). Somewhat different from BLM, SAH attracts more participation from Asian and Black users, including women and younger adults from both groups, but fewer White users (Lyu et al., Citation2021). The greater diversity of participants and number of sub-protests within BLM may lead to a more varied use of words in its social media discourse.

Thirdly, SAH has a shorter history than BLM. Although the Asian community has long confronts racism in the US, SAH does not begin until 2021, whereas BLM starts in 2013. Over time, BLM protests have produced many successes, including pressing cities to cut law enforcement budgets and forcing the resignation of elected officials that are considered violent (Somvichian-Clausen, Citation2020). Moreover, BLM has grown into a national network. More than 30 local BLM chapters have been founded across the United States. A network called the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) comprising dozens of BLM-related groups and structured institutions was established, including the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation (Jones-Eversley et al., Citation2017). These are signals of BLM moving from the coalesce stage to the bureaucratization stage, which is characterized by the accumulation of success and the establishment of formal organizations to sustain the movement (Christiansen, Citation2009). In contrast, SAH can still be considered being in the coalescence stage, where people have started to come together to increase awareness and voice objection to hate crimes toward Asian Americans. Finally, the overarching goal of SAH seems less concrete than BLM’s. As hatred is not a specific policy but an attitude, SAH’s goal of combating hatred toward Asians may be more abstract and difficult to evaluate than BLM’s goal of policy reforms.

3.1. Hypotheses and research questions of the present research

With the aforementioned differences, it is expected that discussion related to SAH and BLM would exhibit different discursive characteristics regarding diversity and emotional and moral sentiments on Twitter. Hereafter, “#BLM” represents the tweet discourse of the social movement BLM and “#SAH” represents the tweet discourse of the social movement SAH. Specifically, in terms of diversity, the expansive scale and broader array of themes and participant demographics within BLM suggest that BLM has a larger number of individuals from diverse backgrounds engaging in discussions about various subjects. This leads us to expect greater word diversity in #BLM than in #SAH (Hypothesis1). In terms of emotional characteristics, as argued above, because BLM is considered to be in a later stage than SAH, the public could still be appraising the hate crimes relevant to SAH. As such, more positive emotions in #BLM than in #SAH would be observed (Hypothesis 2), whereas more negative emotions should appear in #SAH than in #BLM (Hypothesis 3).

However, despite their differences, since SAH and BLM are triggered by violence toward racial minorities, they should both exhibit a strong moral sentiment within their discourses. Moral sentiment is examined through the framework of moral foundations theory (MFT; Haidt & Joseph, Citation2004), which is consistent with past research analyzing the moral framing of the Twitter discourse of #HongKongPoliceBrutality (Wang & Liu, Citation2021).

MFT articulates that humans have five innate moral foundations that guide their moral judgments: care (i.e., concerns for the suffering of others), fairness (i.e., concerns about injustice and inequality), loyalty (i.e., concerns related to the obligations of ingroup members), authority (i.e., concerns about social orders and deference to authorities) and purity (i.e., concerns related to physical and spiritual contagions; Haidt et al., Citation2009). Depending on ideologies and cultures, individuals may prioritize some moral domains when making moral judgements. For example, liberals tend to emphasize care and fairness. In contrast, conservatives do not show much variance across the five foundations (Graham et al., Citation2009; Haidt & Graham, Citation2007). Research also indicates that people from Eastern cultures express greater loyalty and purity-based moral concerns than do individuals from Western cultures (Graham et al., Citation2011). Given that the two movements advocate for different racial groups, we expect to observe distinct patterns in moral sentiment related to the five foundations between the discourses of the two movements. Also, because BLM addresses police brutality and power hierarchies, its discourse should center around authority. As such, it is expected that authority is more salient in #BLM than in #SAH(Hypothesis 4).

Taken together, this study proposes the following questions and hypotheses:

Research Question 1:

How does the volume of #BLM and #SAH tweets change over time?

Hypothesis 1:

#BLM exhibits greater word diversity than #SAH.

Hypothesis 2:

#BLM displays more positive emotions than #SAH.

Hypothesis 3:

#SAH displays more negative emotions than #BLM.

Research Question 2:

What are the moral sentiment patterns in BLM and SAH?

Hypothesis 4:

The authority foundation is more salient in #BLM than in #SAH.

To answer these questions and test our hypotheses, this research employs an automated text analysis using a dictionary-based word-count approach, utilizing the corpus of tweets built through the process described below.

4. Method

4.1. Data sample

We queried tweets containing the case-sensitive hashtags #BlackLivesMatter, #BLM, #StopAAPIHate and #StopAsianHate from 15 April 2020, to 14 April 2021, through the Twitter API. This time range was selected because it covers the time periods when the major incidents (i.e., the killing of George Floyd and six Asian women) and when COVID-19 was serious, which serves as an important background for the movements.

Because Twitter only allows researchers to collect up to 10 million tweets per monthFootnote1, on average, 2.5 million tweets should be collected for each of the four hashtags in this research. Therefore, we needed to predetermine the maximum number of tweets collected for each day, which we set to 35,000 tweetsFootnote2.

Next, time for each day was divided into 10-minute time intervals, the order of which was then randomized. Tweets were collected from each interval one by one until the total number of tweets containing a hashtag reached the maximum quota or all tweets were collected within the year. After data collection, one tweet identified by Twitter as coming from a trolled account was removedFootnote3.As a result, approximately 4.5 million tweets with #BLM or #BlackLivesMatter from 356 days and 0.31 million tweets with #StopAsianHate or #StopAAPIHate from 348 days were collected. All of them are English tweets, including quote tweets but not retweets. Tweet features, such as creation time and tweet ID, were also collected alongside the tweet text. The same tweets containing both hashtags appear only once in the dataset.

4.2. Data preprocessing

We first cleaned the tweet text by removing duplicate tweets with identical tweet IDs and tweets with the same content posted by the same authors. We then lowercased all tweets, removed hyperlinks and the symbols “#” and “@”, and expanded common abbreviations. Clean tweets from #BlackLivesMatter and #BLM were then grouped by the date they were created to represent the tweet corpus of BLM movement. Likewise, tweets associated with #StopAsianHate and #StopAAPIHate were grouped to create the tweet corpus for the SAH movement. Duplicated tweets with the same tweet ID were removed. To prepare for word counts, we then tokenized tweet corpuses and removed common words that had no significant meanings, known as stopwords, as well as misspelled and uncommon words not listed in the word corpus specified in the Natural Language Toolkit (Bird et al., Citation2009). After these procedures, all words were considered valid words to be counted. Consequently, 356 bags of valid words for BLM and 348 bags of words for SAH were created, which served as the units of analyses for the word count method.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Moral sentiment

Moral sentiment was measured by the proportion of moral words among valid words. The Moral Foundations Dictionary 2.0 (MFD2.0; Frimer et al., Citation2019) was used to identify moral words. This dictionary includes 2,103 words and phrases manually identified by domain experts that convey the moral meanings of the vices and virtues of the five moral foundations, such as “love” in care and “betray” in (dis)loyalty. Moral sentiment was computed by dividing the number of words corresponding to each moral foundation, as identified in the dictionary, which occurred in the daily bag of words by the total number of valid words in the same bag of words.

4.3.2. Emotion

Emotion was measured by the proportion of words related to a specific emotion in tweets. The NRC Emotion Lexicon (EmoLex, version 0.92; Mohammad & Turney, Citation2013) was utilized to identify emotional words. EmoLexis a widely used dictionary of emotions that assesses emotions in written text, and it outperforms other lexica in detecting fear, anger, and joy (Kušen et al., Citation2017). EmoLex lists 14,182 English words and their associations with eight basic emotions. Four of them, including trust, surprise, anticipation and joy, are positive, and four, including anger, fear, sadness, and disgust, are negative. It also includes overall positive and negative sentiments. The dictionary indicates whether a word is associated with the above emotions through binary coding (0 = not associated, 1= associated) manually annotated by participants recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mohammad & Turney, Citation2013). Emotional sentiment was computed by dividing the number of words associated with each emotion in the dictionary that occurred in the daily bag of words by the total number of valid words in the same bag of words.

4.3.3. Diversity

To measure the diversity of words in the Twitter discourses, we employed Shannon entropy proposed by Shannon (Citation1948) in his seminal work on information theory. This approach is consistent with Gallagher et al. (Citation2018) method to compare word diversity within tweets containing #BlackLivesMatter and #AllLivesMatter. This method is defined as

where is the word frequency of ith words in tweets and

is the number of valid words in a text. A higher Shannon entropy indicates greater word diversity in a text.

5. Results

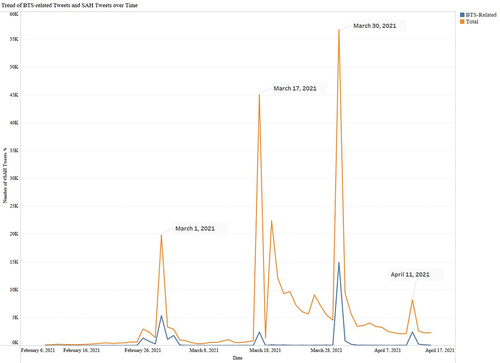

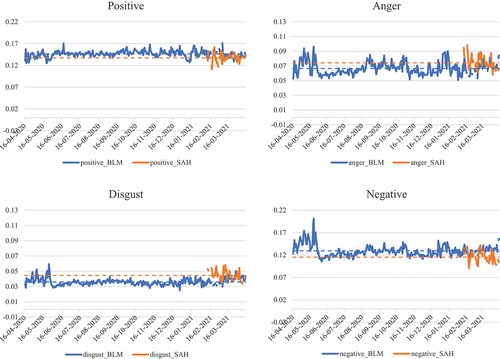

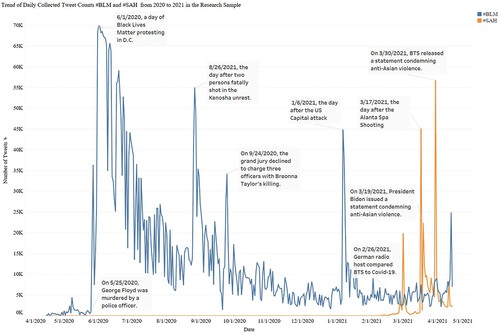

To answer RQ1, we examined the number of tweets collected in our sample in the two movements over time. Figure shows the trend of daily tweet counts throughout the year. It becomes evident that the Twitter discourses of both movements experienced several waves in response to major incidents. Overall, compared to #SAH, the peaks of #BLM were higher and wider. This suggested that the peaks for #BLM were not only more pronounced but also sustained over an extended period than those observed for #SAH.

Figure 1. Daily tweet volume of #BLM and #SAH from 2020 to 2021.

A close inspection of these peaks reveals that the first and most important peak period for #BLM started on 25 May 2020, the day George Floyd was murdered. As expected, the most prominent peak of #SAH started on 16 March 2021, when the Atlanta spa shooting occurred. Of additional interest is that several peaks of #SAH were directly linked to celebrities, specifically the Korean pop group BTS. For example, on 26 February 2021, a German radio host likened BTS to COVID-19, which made BTS a trending topic on Twitter. BTS fans soon took a stand by tweeting, “Racism is not an opinion,” a tweet quoted widely (31% of total collected tweets on that day). Another notable example appeared on March 30, when BTS published a letter on Twitter in support of SAH. That day, 26.19% of the tweets mentioned “BTS”. These anecdotal observations suggested that while #BLM’s periodic increase was often in response to events, #SAH was greatly influenced by celebrities.

The daily tweet volume of SAH combines the total number of daily tweets with #StopAAPIHate and #StopAsianHate.

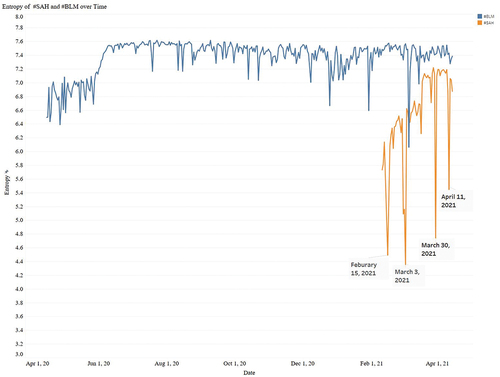

5.1. An adhoc analysis of BTS-related tweets

Given the prevalent occurrence of BTS in the SAH tweets, BTS-related tweets may exert influences on the word diversity and sentiment of #SAH. To provide a picture of the proportion of BTS-related tweets in #SAH before we proceeded with subsequent analyses, an adhoc analysis was conducted to count the percentage of BTS-related tweets. A few criteria were used to identify those tweets: 1) whether the cleaned tweets contained lowercase “BTS” or words that originated with BTS and were widely disbursed among their fans, including 2) “We stand against racial discrimination. We condemn violence”, 3) “You, I and we all have the right to be respected. We will stand together”, 4) “Racism is not an opinion” and 5) “Racism is not comedy.” It was found that tweets containing any of these phrases accounted for 10.78% of the tweets in #SAH and 0.3% in #BLM. Figure demonstrates the day-to-day changes in BTS-related tweets and total tweets in #SAH.

5.2. Word diversity

To test H1, entropy values for both discourses were computed. The results show that the overall entropy of #SAH is 6.90, lower than that of #BLM, which is 7.65. A t test was conducted to examine whether the daily entropy differed between the two discourses. The results suggest that daily entropy was greater in #BLM (M = 7.38, SD = .25) than in #SAH (M = 6.54, SD =.69), t (414) = 16.71, p < .001, supporting H1.

Before delving into the moral and emotional valence of each discourse, steps were taken to filter out noisy data. On the days when there were few words in the bag of words, the appearance of one moral word would greatly sway the moral sentiment of that day’s tweets, adding noise to the analysis; for this reason, days with fewer than 1,000 total words for each discourse was first excluded, resulting in 61 bags of words for #SAH and 355 for #BLM. Figure displays the trend of entropy over time for both movements. Additionally, because the above BTS sub-analysis suggested that celebrities play an important role in forming the Twitter discourse of SAH, the words they use could greatly sway the moral and emotional tone of a conversation. To prevent those factors from biasing the results, a statistical profiling approach was utilized to filter out abnormal time series data (Bhattacharya, Citation2020). Specifically, the 7-day moving average of entropy was calculated, and those days that fell beyond one standard deviation of the moving average were removed from the subsequent analysis. As a result, no extremely low entropy values were shown in the dataset, suggesting that the approach successfully eliminated data from dates when tweets were overly homogenous, thus systematically decreasing the influence of the dominating voices from celebrities on both #SAH and #BLM. After these procedures, the moral and emotional sentiment described in the next section was evaluated for the 50 bags of words for SAH and 301 for BLM.

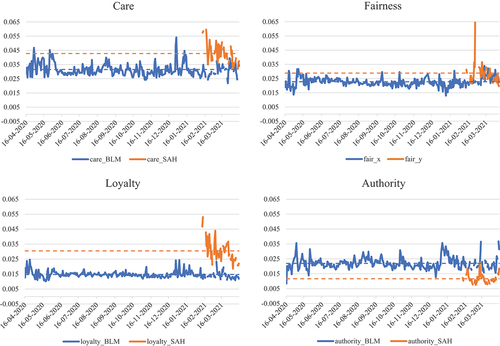

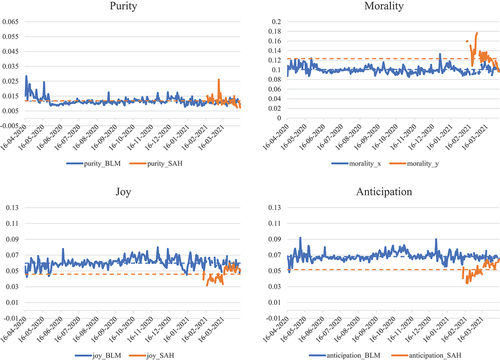

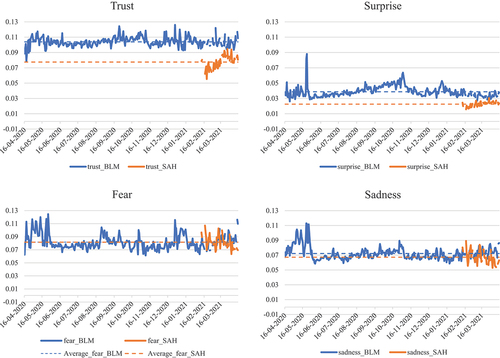

To test H2 and H3, a multivariate ANOVA was conducted to show whether #BLM and #SAH differ in their prevalence of positive and negative emotions. The results showed that the multivariate test was significant; Pillai’s Trace = .86, p < .001. Subsequent univariate tests suggested that all positive emotions, including joy, anticipation, trust, surprise and their positive sentiments, were more prevalent in #BLM. While anger and disgust were more prevalent in #SAH, sadness and overall negative sentiments were more prevalent for #BLM. Thus, H2 was supported, and the results for H3 were mixed.

A multivariate ANOVA was conducted to determine whether #BLM and #SAH differ in their salience of five moral foundations and overall morality. The results suggested that the multivariate test was significant; Pillai’s trace = .82, p < .001. Subsequent univariate tests showed that care, fairness, and loyalty were more prominent in #SAH than in #BLM, but purity did not differ between the two movements, thereby answering RQ2. More importantly, authority was more prominent in #BLM than in #SAH, thus supporting H4. Table shows the correlation matrix, and Table illustrates the findings regarding the moral and emotional characteristics of the two movements. Table demonstrates the examples for each sentiment category. Appendix A also illustrates the patterns of each moral and emotional sentiment across the two movement discourses.

Table 1. Correlation matrix

Table 2. Results of tests of between-subjects effects on emotion and moral sentiments of #BLM and #SAH

Table 3. Examples of tweets containing moral and emotional sentiments

6. Discussion

Applying an automated text analysis, this study presents preliminary insights into the characteristics of the Twitter discourse of SAH and BLM by comparing their discourses. The results shed lights on the emotional and moral reactions of social media users, an important group of actors in social activism in the internet age (Earl & Kimport, Citation2011), to racial injustice in different movements. It also offers a more nuanced understanding of the differences and similarities between the two most significant anti-racism movements in recent years. Overall, the study found that #SAH can be characterized as more centralized (as indicated by its lower lexical diversity), less anti-authority, less positive in emotional sentiment and more morally salient than #BLM. These differences may be attributed to socio-cultural contexts and the stages that the two movements are in, and the different objectives of the two movements, as discussed below.

As expected, we observe a lower level of word diversity in #SAH than #BLM. This could be due to the involvement of less diverse participants and fewer counter-protests in SAH. Interestingly, it is found that BTS plays a key role in shaping the online discussion of SAH. This finding resonates with the cultural phenomenon of BTS’s worldwide recognition and popularity, rendering them suitable endorsers for SAH. In fact, celebrity endorsement has been a prevalent strategy in advertising (Erdogan, Citation1999) and advocacy (Thrall et al., Citation2008). However, prior research indicates that the use of celebrities is more common in Asian countries than in Western ones (Choi et al., Citation2005). This is partly because Asian communities, a group that places greater value on collectivism (Hofstede, Citation1984), are more likely to conform to social norms and trends. Thus, this group may be more likely to follow opinions of celebrities. Indeed, our findings, showing BTS’s prominence within #SAH, provide additional evidence that celebrity endorsement in leading social movements could be a more effective strategy for the Asian community.

Notably, celebrity endorsements in social movements can yield both favorable and unfavorable outcomes. On the positive side, such endorsements can establish global connections that bring together audiences with diverse backgrounds, particularly for causes that may seem psychologically distant for some groups of audiences, such as anti-racism toward Asians. On the negative side, celebrity endorsement often provides a heuristic cue for fans to make a judgment (Bergkvist & Zhou, Citation2016), leading to weaker attitudes than those developed from careful evaluations (Chen & Chaiken, Citation1999). Given that K-pop fans are well known for their intense affections (Williams & Ho, Citation2016), the heuristic nature of judgment can be strong. This prompts questions regarding the persistence and genuineness of fan engagement in SAH and their sustained support for the movement.

The research also found that #BLM displays more positive emotions, including surprise, joy, trust, and anticipation, than does #SAH. In terms of negative emotions, #BLM has more sadness and overall negative sentiments, and #SAH contains more anger and disgust. As mentioned above, the differences in the prominent expressed emotions may be explained by the different stages the two movements are currently in. With over a decade of mobilization, BLM likely entered the late stages of a social movement, characterized by the accumulated success and establishment of formal organizations (Jones-Eversley et al., Citation2017). Positive emotions can stem from these achievements and a necessity to sustain the members’ support. In contrast, SAH is still in the early stage of coalescence, and violence toward Asian people can overwhelm community members. The greater anger and disgust people expressed in SAH discourse signals that participants are still grappling with the initial shock induced by moral transgressions. Expressing and spreading negative moral emotions is particularly necessary for SAH participants to motivate antiracist actions because Asian people have been characterized as a “model minority”, perceived to be nice and problem-free despite the prolonged unjust treatment they have endured (Lee, Citation2015).

The different stages can also explain why #SAH is more morally charged than that #BLM. Specifically, care, fairness, and loyalty were more salient in #SAH, whereas #BLM emphasizes authority more. This finding is reasonable because SAH focuses on hate crimes toward Asians, a topic more related to care and fairness, whereas BLM centers on police brutality that is more closely related to authority. The finding also supports the argument that witnessing or experiencing moral violations can activate individuals’ sensitivity to relevant moral intuitions (Tamborini, Citation2012). Nevertheless, to fully reveal how moral and emotional sentiment vary across different stages, future studies conducting a time-series analysis with full tweet archives would be beneficial.

The findings also confirm the applicability of social media in mobilizing racial movements. First, our study shows that tweet counts escalate immediately following major events in SAH and BLM, demonstrating the ability of social media to immediately share information among users. Second, the study identified the distinct discursive characteristics of BLM and SAH on Twitter, which demonstrates the ability of social media users to co-create a unique narrative for each movement. Finally, the research identified strong collective emotional and moral sentiments in the discourse, which reflects that emotions can be spread and expressed within an online social network.

At the same time, more questions related to the boundaries of social media in mobilizing anti-racist social movement discourse have yet to be answered. For example, how does the profit-driven nature of social media influence the meaning production and decoding process, and does the public discourse in the Twittersphere complement or contest the mainstream media representations of oppressed groups (Satchel & Bush, Citation2020)? To answer these questions, comparative discursive analysis that examines the information sources and contexts (Fairclough, Citation2013) may be warranted.

Ultimately, the current study suggests that much work remains for online activism to ensure the success of the two movements. For SAH, since the tweet volume is relatively low, activists should continue to encourage individuals to increase the public visibility of its primary issue. Additionally, due to the low word diversity in #SAH, it is important to involve a variety of opinion leaders—including community leaders and politicians—in the online discourse to enrich the conversation. For BLM, a movement that has already garnered much national and international attention, activists may consider how to continue this rich narrative while also sustaining its vitality on social media. Finally, although the research has stressed the differences between SAH and BLM, considering their shared anti-racism objectives, many activists and movement leaders should participate in both movements. Consequently, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of discourse characteristics, future research should explore how these movements intersect, i.e., how many conversations mention both movements and how discussants interact with each other. Did the SAH movement facilitate public discussion of BLM? Did it shift public attention away from it? Future research should incorporate social network analysis to uncover these interactions.

The study also has some limitations. The first pertains to the representativeness of the sample. The current research focuses on Twitter discourses because Twitter is a center for people to engage in the BLM and SAH (Edrington & Lee, Citation2018; Tillery, Citation2019). However, Twitter users tend to be younger, better educated, have a higher income, and are more likely to be Democrats than the general public (Wojcik & Adam, Citation2019). Thus, the results may not be generalizable to a broader public. In addition, Twitter has suffered from troll account issues and starts removing them since 2018. Although only one automated tweet was identified in our data, more extensive efforts on detecting bots and trolled accounts in future research would be beneficial. Second, offline conversations and activities in the case movements were not observed in this research, so it is unknown how either discourse may translate to offline protests. Third, moral emotions comprise a wide range of emotions—including contempt, empathy, and guilt—which this research has not examined. However, investigating these emotions would require an emotional lexicon that contains a wider range of moral emotions, which still need to be developed. Finally, the two movements happen during the COVID-19 pandemic, and scholars have argued that COVID-19 has amplified the spread of negative emotions across the US (Grant & Smith, Citation2021). It may be worthwhile to compare BLM discourse before and during the pandemic to show how the pandemic has affected the emotional and moral discussion of racial injustice.

7. Conclusion

This exploratory study sets out to characterize and compare the social media discourses of BLM and SAH during the COVID-19 pandemic. A large corpus of tweets was collected and analyzed via natural language processing techniques. The results showed that compared to BLM discourse on Twitter, SAH discourse was overall less diverse in words, stronger in moral sentiment, and less positive in emotional sentiment. Moreover, the SAH discourse contained more moral emotions such as anger and disgust than the BLM discourse. These findings revealed that although these two movements share much in common, the social media discourses they generated have been quite different in terms of sentiment and discursive development. We argued that these findings can be attributed in part to the different cultural backgrounds and demographics of the participants, the stages and the specific objectives of the movements. This research extends the scope of previous social movement research by comparing two social movements, and by analyzing a large scale of tweet data to gauge discursive characteristics. The findings reflect the public opinions on anti-racism issues, highlighting social media’s unique characteristics in fostering movement discourses. Taken together, the findings underscore the necessity for social media activism, an increasingly prevalent form of activism, to tailor its strategies to the unique characteristics of a movement, such as its stage, history, goal and participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jialing Huang

Jialing Huang (PhD, University at Buffalo, SUNY) is an associate professor in the School of Media and Communications at Shenzhen University. Her research examines the psychological influences of narratives and media entertainment.

Junjie Zhu

Junjie Zhu (PhD., New York University) is a quantitative researcher at Occudo Quantitative Strategies. He develops and implements investment strategies based on quantitative analysis and mathematical models using large datasets and statistical tools.

Notes

1. Please see more details at https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api/getting-started/about-twitter-api

2. When determining the predetermined daily limit, we need to ensure that the predetermined daily limit allows us to 1) collect a considerable number of tweets each day to show trends; 2) have enough tweets to aggregate into a large tweet corpus to reduce the noise of individual tweets; 3) avoid a situation where tweets of one or two single days exhaust the quota; and 4) make good use of the total tweet limit set by Twitter. To calculate the daily limit, we needed to first determine how many days we should collect tweets from. We first heuristically used 100 days of tweets as an anchor point for the decision, which means that we wanted to collect at least 100 days of tweets. This would set the daily limit of 25,000. However, the threshold of 25,000 still seems insufficient based on previous research on Tweet amounts related to BLM (Anderson et al., Citation2020), so we increased it to 35,000 tweets. Notably, if the collection exhausts all tweets of the day before reaching the daily limit, it would move on to the next randomly chosen day, but the leftover tweet quota would allow us to collect tweets from more days. Therefore, it is likely that the 35,000 daily limit would still allow us to select tweets from 100 days or even more.

3. Twitter released lists of trolled accounts and corresponding tweets onhttps://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2021/disclosing-state-linked-information-operations-we-ve-remove

References

- Anderson, M., Barthel, M., Perrin, A., & Vogels, E. (2020) #blacklivesmatter surges on Twitter after George Floyd’s death. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/10/blacklivesmatter-surges-on-twitter-after-george-floyds-death/

- Bergkvist, L., & Zhou, K. Q. (2016). Celebrity endorsements: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 642–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1137537

- Bhattacharya, A. (2020). Effective approaches for time series anomaly detection. https://towardsdatascience.com/effective-approaches-for-time-series-anomaly-detection-9485b40077f1

- Bird, S., Klein, E., & Loper, E. (2009). Natural language processing with Python: Analyzing text with the natural language toolkit. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- Buchanan, L., Bui, Q., & Patel, J. K. (2020, July 3). Black lives matter may be the largest movement in US history. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html

- Caren, N., & Gaby, S. (2012). Sociologist tracks social media’s role in occupy wall street movement. University of North Carolina.

- Carney, N. (2016). All lives matter, but so does race: Black lives matter and the evolving role of social media. Humanity & Society, 40(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616643868

- Chao, M. (2021). Can the anti-Asian hate movement learn from black lives matter? https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/2021/05/14/black-lives-matter-and-stop-asian-hate-movement-build-bridges-nj/4894190001/

- Chen, S., & Chaiken, S. (1999). The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 73–96). Guilford Press.

- Choi, S. M., Lee, W. N., & Kim, H. J. (2005). Lessons from the rich and famous: A cross-cultural comparison of celebrity endorsement in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 34(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639190

- Christiansen, J. (2009). Social movement and collective behavior: Four stages of social movement. EBSCO Research Starter.

- Clark, M. D. (2019). White folks’ work: Digital allyship praxis in the# BlackLivesMatter movement. Social Movement Studies, 18(5), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2019.1603104

- Duvall, S. S., & Heckemeyer, N. (2018). # BlackLivesMatter: Black celebrity hashtag activism and the discursive formation of a social movement. Celebrity Studies, 9(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2018.1440247

- Earl, J., & Kimport, K. (2011). Digitally enabled social change: Activism in the Internet age. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262015103.001.0001

- Edrington, C. L., & Lee, N. (2018). Tweeting a social movement: Black lives matter and its use of Twitter to share information, build community, and promote action. Journal of Public Interest Communications, 2(2), 289–289. https://doi.org/10.32473/jpic.v2.i2.p289

- Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870379

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Routledge.

- Foust, C. R., & Hoyt, K. D. (2018). Social movement 2.0: Integrating and assessing scholarship on social media and movement. Review of Communication, 18(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2017.1411970

- Frangonikolopoulos, C. A., & Chapsos, I. (2012). Explaining the role and the impact of the social media in the Arab Spring. Global Media Journal: Mediterranean Edition, 7(2), 10–20.

- Freelon, D., McIlwain, C. D., & Clark, M. (2016). Beyond the hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the online struggle for offline justice. Center for Media and Social Impact, American University. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2747066

- Frijda, N. H. (1987). Emotion, cognitive structure, and action tendency. Cognition and Emotion, 1(2), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699938708408043

- Frimer, J. A., Boghrati, R., Haidt, J., Graham, J., & Dehghani, M. (2019). Moral foundations dictionary for linguistic analyses 2.0. Unpublished Manuscript

- Gallagher, R. J., Reagan, A. J., Danforth, C. M., & Dodds, P. S. (2018). Divergent discourse between protests and counter-protests: # BlackLivesMatter and# AllLivesMatter. PloS One, 13(4), e0195644. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195644

- Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the streets: Social media and contemporary activism. Pluto Press.

- Goodwin, J., & Jasper, J. M. (2006). Emotions and social movements. In Handbook of the sociology of emotions (pp. 611–635). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30715-2_27

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015141

- Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

- Grant, P. R., & Smith, H. J. (2021). Activism in the time of COVID-19. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220985208

- Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z

- Haidt, J., Graham, J., & Joseph, C. (2009). Above and below left–right: Ideological narratives and moral foundations. Psychological Inquiry, 20(2–3), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400903028573

- Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2004). Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus, 133(4), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526042365555

- Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1(2), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01733682

- Jasper, J. M. (1998). The emotions of protest: Reactive and affective emotions in and around social movements. Sociology Forum, 13(3), 397–424. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022175308081

- Jasper, J. M. (2011). Emotions and social movements: Twenty years of theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 37(1), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150015

- Jones-Eversley, S., Adedoyin, A. C., Robinson, M. A., & Moore, S. E. (2017). Protesting black inequality: A commentary on the civil rights movement and black lives matter. Journal of Community Practice, 25(3–4), 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2017.1367343

- Kušen, E., Cascavilla, G., Figl, K., Conti, M., & Strembeck, M. (2017, August). Identifying emotions in social media: Comparison of word-emotion lexicons. Proceedings of the 2017 5th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud Workshops (FiCloudW), Prague, Czech Republic (pp. 132–137). IEEE.

- Lee, S. J. (2015). Unraveling the“model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. Teachers College Press.

- Lotan, G., Graeff, E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., & Pearce, I. (2011). The Arab Spring| the revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1375–1405.

- Lyu, H., Fan, Y., Xiong, Z., Komisarchik, M., & Luo, J. (2021). State-level racially motivated hate crimes contrast public opinion on the# StopAsianHate and# StopAAPIHate movement. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.14536

- Mohammad, S. M., & Turney, P. D. (2013). Crowdsourcing a word–emotion association lexicon. Computational Intelligence, 29(3), 436–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8640.2012.00460.x

- Mundt, M., Ross, K., & Burnett, C. M. (2018). Scaling social movements through social media: The case of black lives matter. Social Media + Society, 4(4), 2056305118807911. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118807911

- Nummi, J., Jennings, C., & Feagin, J. (2019). # BlackLivesMatter: Innovative black resistance. Sociological Forum, 34(S1), 1042–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12540

- Olteanu, A., Weber, I., & Gatica-Perez, D. (2016, March). Characterizing the demographics behind the# blacklivesmatter movement. Proceedings of the 2016 AAAI Spring Symposium Series, Stanford, CA.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2016). Affective publics and structures of storytelling: Sentiment, events and mediality. Information, Communication & Society, 19(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1109697

- Roseman, I. J., Spindel, M. S., & Jose, P. E. (1990). Appraisals of emotion-eliciting events: Testing a theory of discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 899–915. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.899

- Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296–320. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0504_2

- Satchel, R. M., & Bush, N. V. (2020). Social movements, media, and discourse: Using social media to challenge racist policing practices and mainstream media representations. In The rhetoric of social movements (pp. 172–190). Routledge.

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x

- Somvichian-Clausen, A. (2020). What the 2020 black lives matter protests have achieved so far. https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/equality/502121-what-the-2020-black-lives-matter-protests-have-achieved-so/

- Tamborini, R. (2012). A model of intuitive morality and exemplars. In R. Tamborini (Ed.), Media and the moral mind (pp. 43–74). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203127070

- Taylor, V., & Whittier, N. (1992). Collective identity in social movement communities: Lesbian feminist mobilization. In A. Morris & C. Mueller (Eds.), Frontiers in social movement theory (pp. 104–129). Yale University Press.

- Thrall, A. T., Lollio-Fakhreddine, J., Berent, J., Donnelly, L., Herrin, W., Paquette, Z., Wenglinski, R., & Wyatt, A. (2008). Star power: Celebrity advocacy and the evolution of the public sphere. The International Journal of Press/politics, 13(4), 362–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208319098

- Tillery, A. B. (2019). What kind of movement is black lives matter? The view from Twitter. Journal of Race, Ethnicity, & Politics, 4(2), 297–323. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.17

- Wang, W. (2021) What can Asian Americans learn from BLM movement? Retrieved from https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219123.shtml

- Wang, R., & Liu, W. (2021). Moral framing and information virality in social movements: A case study of# HongKongPoliceBrutality. Communication Monographs, 88(3), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2021.1918735

- Williams, J. P., & Ho, S. X. X. (2016). “Sasaengpaen” or K-pop fan? Singapore youths, authentic identities, and Asian media fandom. Deviant Behavior, 37(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2014.983011

- Wojcik, S., & Adam, H. (2019). Sizing up Twitter users. https://pewrsr.ch/2VUkzj4