Abstract

The relationship between sustainable tourism development and tourism branding has received rising attention among scholars. Due to the complex relationship between the two concepts results in inconsistent findings among previous research. However, bibliographic analysis studies that organize previous research in the field are lacking. Therefore, this study examines the Scopus database for articles on “sustainable tourism branding.” The searches were repeated twice on 31 March 2021, and 7 June 2022, yielding 55 and 68 valid documents, respectively, illustrating 15 years of subject area expansion from 2007 to 2022. Using Vosviewer software, the datasets were subsequently analyzed and visually represented. The results provide an overview of the topic’s expansion rate, including the top cited studies, authors, organizations, journals, and countries. In addition, the study investigates the foundational research that provides fundamental knowledge for researchers. Finally, a current research trend and a prospective research agenda have been proposed.

1. Introduction

Globalization has put a strain on our environment, resulting in undesirable outcomes such as air pollution, global warming, and natural resource depletion (Perkumienė et al., Citation2020). Humans have experienced extreme weather events and started to worry about their future (Capstick et al., Citation2015). From this point, people begin to cultivate their values towards the green practice advocation, such as anthropocentric, ecocentric (Soyez, Citation2012), self-transcendence, self-enhancement (Jacobs et al., Citation2018), environmental consciousness (Cheung & To, Citation2019), egoistic, altruistic and biospheric values (Rahman & Reynolds, Citation2019). These values are proven to influence our attitude toward a green and sustainable lifestyle, which shows the way to prioritize choosing green products (Kautish & Sharma, Citation2019). As time progressed, marketers began incorporating sustainable practice activities into their marketing and communication efforts to build a green and sustainable brand. In business, it is proven that the customers’ perceived green value plays an essential role in building green corporations’ brand equity (Kazmi et al., Citation2021).

Tourism is widely believed as an industry that significantly contributes to the greenhouse effects and CO2 emissions (Lenzen et al., Citation2018). In response to the rise in customer needs and values that promote sustainable activities, the tourism industry actively engages in green and sustainable practices (Groening et al., Citation2018; Visković, Citation2020). Research has demonstrated the effects of tourists’ values, such as economic, social, hedonic, and altruistic, on their intention to choose a tourism destination, implying sustainable development’s critical role in the tourism section (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020b). However, a sustainable tourism model not only focuses on the environment; it also considers other aspects of a location, including culture, economy, and society (Pan et al., Citation2018).

Unsurprisingly, Sustainable tourism practices have been recently focused on as part of the sustainable tourism branding effort (Ruiz et al., Citation2019). Corporate social responsibility activities (CSR) have been demonstrated to impact tourists’ perception of the tourism organizations’ brand equity (Janjua et al., Citation2022; Moise et al., Citation2019), brand trust and commitment (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020a), as well as brand love (Rodrigues et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the sustainable practices in Spanish gastronomic tourism are also able to influence the whole country’s brand (Vázquez-Martinez et al., Citation2019).

It is acknowledged that researchers are becoming increasingly interested in the topic of sustainable tourism branding. Previous study, however, has revealed inconsistent results regarding the relationship between tourist branding and sustainable tourism development. In certain instances, tourism branding activities can support the destination’s efforts toward sustainable development (Black & Thwaites, Citation2011; Jankovic et al., Citation2019), and vice versa (Janjua et al., Citation2022; Milman et al., Citation2021; Pham Hong et al., Citation2021). In other cases, the pressure to attain the eco-label standard compels organizations to embrace conspicuous sustainable development initiatives (Grydehøj & Kelman, Citation2017). Several studies also find that branding and marketing efforts may be utilized to conceal the detrimental effects of tourism (Bell, Citation2008; Büscher & Fletcher, Citation2017; Salazar, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2022). Even though Cavalcante de et al. (Citation2021) have provided a literature review on sustainable tourism marketing. There is a distinction between location marketing and branding because branding activities are more concerned with customer satisfaction than profit (Zenker & Martin, Citation2011). Furthermore, consider the complexity of tourism branding (Gartner, Citation2014; Hankinson, Citation2004) and the sustainable tourism concept (Pan et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it is necessary to initiate a literature review on sustainable tourism branding to develop an overview of the sustainable destination’s branding strategies and a future research agenda.

2. Literature review

2.1. Sustainable tourism

Tourism often being considered a service that negatively affects the environment (Wong, Citation2004). Acknowledging the fact, the industry has applied multiple measures to improve the situation, including green practices, which refer to a system of processes and procedures in management to minimize tourism’s negative impacts on the environment (Yusof et al., Citation2017).

From a broader perspective, sustainable tourism is not only reducing the adverse effects of tourism activity but also accomplishing ecologically sustainable, economically viable, as well as ethically and socially equitable outcomes for the society and economy (UNEP, Citation2005). Therefore, Pan et al. (Citation2018) have proposed a framework in which the tourism chain is linked to sustainable development through the implementation of green building, energy, agriculture, transportation, infrastructure, and smart technology.

From the perspective of customers, Yu et al. (Citation2017) noticed that many hotels had implemented green practice measures from minimum to advanced levels. From another perspective, hotel employees acknowledge green practices as a branding strategy, which leads to sustainable development (Alipour et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the trend of green and sustainable tourism can be found in many studies with diverse results (Bell, Citation2008; Samuels & Platts, Citation2020). Additionally, as suggested by Ahn and Kwon (Citation2020b), tourists do assess the value they receive (economic, social, hedonic, altruistic) and the cost they pay (price, effort, evaluation cost, and performance risk) before developing their attitude and intention to experience green services.

A combination of green practices and proposals to reform the tourism industry to make it more eco-friendly gave rise to the concept of green tourism, which aims to create cohesion with the nature of the tourism destination to achieve sustainable development (Jones, Citation1987). The concept was later converted into sustainable tourism, in which the industry thrives in balance within the economic, environmental, and social aspects (Pan et al., Citation2018). Sustainable tourism development is generally required to improve the quality of life in the destination community while maintaining the environment’s quality (Postma & Schmuecker, Citation2017).

2.2. Sustainable tourism branding

To answer the question, what is sustainable tourism branding? It is important first to understand the concept of a brand. At its basic function, a brand was a mark to distinguish one product/service from another (Murphy, Citation1987). From the customers’ perspective, brands symbolize quality, reduce risk, and foster a sense of trust. For corporations, brands are assets that could measure their branding and marketing efforts (Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006). Therefore, branding is a process of filling products or services with the sense, meaning, and power of a brand (Kotler & Keller, Citation2015).

Through the pressure of globalization, there was a shift from product branding to corporate branding (Aaker, Citation1996). Through the process, a strong brand image was demonstrated to increase the organization’s visibility, recognition, and reputation (Jo Hatch & Schultz, Citation2003). Additionally, the academic community has focused on the concept of brand equity, roughly defined as the net present value attributed to a brand (Shankar et al., Citation2008; Shocker & Weitz, Citation1988). On the one hand, brand equity is important to both consumers and corporations (Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006). On the other hand, brand equity is a complex and multidimensional concept consisting of various aspects, such as brand loyalty, brand awareness, brand quality, and brand image (Zhang et al., Citation2020).

Soon enough, brand management scholars have again transferred their branding knowledge to a new territory—place and destination branding (Hankinson, Citation2004; Hosany et al., Citation2006; Kavaratzis & Ashworth, Citation2005). While place branding focuses on applying marketing efforts in different location’s aspects, such as economic, political, and socio-cultural (Anholt, Citation2005), destination branding concentrates more on the tourists’ perspective and tourism approach (Hosany et al., Citation2006). As a result, the two concepts’ literature frequently overlaps, with destination branding considered a component of place branding (Hanna et al., Citation2021). In general, researchers will benefit from taking into account both concepts in tourism branding study (Hankinson, Citation2005). From the tourism perspective, destination brand equity is also applied to assess the destination brand’s performance (Shi et al., Citation2022)

According to Kotler and Gertner (Citation2002), a place’s brand equity might affect customers’ and investors’ attitudes toward its products and services. Then, Cai (Citation2002) connects the branding literature to the concept of tourism destination image. Moreover, by reviewing previous studies, Blain et al. (Citation2005) proposed the concept of destination branding and suggested various practical implications to enhance branding effectiveness. However, Pike (Citation2005) noted the difficulty of the tourism destination branding process due to the complicated nature of the industry. In many ways, tourism branding is a similar concept to place or destination branding (Scott et al., Citation2011).

As the trend of green and sustainable tourism development emerges, the tourists’ green values and attitudes impact their behaviors (Kautish & Sharma, Citation2019). Researchers notice the dynamic relationship between branding and sustainable tourism. In many cases, tourism branding could be used to support sustainable tourism development (Ndlovu & Heath, Citation2013; Ushakov et al., Citation2018). On the contrary, sustainable tourism destinations increase the competitiveness of a country’s brand in the marketplace (Hassan & Mahrous, Citation2019). In addition, cultural, environmental, infrastructure and service factors have been shown to influence tourism destination brand equity (Górska-Warsewicz, Citation2020; Menon et al., Citation2021). In order to solidify the relationship between branding and sustainable tourism development, it is crucial to undertake a systematic review on the topic of Sustainable tourism branding that incorporates both a place and a destination branding approach.

3. Methods

Bibliometrics analysis is a statistical investigation of the current state of the studies on a specific subject area that employs quantitative analysis of articles on a certain topic (Mayr & Scharnhorst, Citation2015). Consequently, the purpose of this work is to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the existing academic papers database on sustainable tourism branding.

3.1. The database of relevant papers

The information utilized to investigate the database is regarded as the most relevant in bibliometric analysis, according to Abramo et al. (Citation2011). As a result, the study makes use of the Scopus database, which comprises studies dating back to 1966, for a variety of reasons. According to Falagas et al. (Citation2008), Scopus has roughly 20 percent more coverage than Web of Science to make up for the paucity of research conducted prior to 1966. Regardless of the absence, previous research discovered a significant correlation between the two databases in terms of the number of papers and citations by country and rank (Archambault et al., Citation2009). Zhu and Liu (Citation2020) discovered that these two databases shared a substantial number of documents and that Scopus was more frequently used than Web of Science in 2018. More specifically, it is estimated that in the Social Science field, the overlaps between two databases are 34%, Scopus exclusive materials are 64%, and Web of Science exclusive documents are only 2% (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Citation2016). Considering the completeness of the databases and the risk of document duplication when integrating data from multiple sources, the authors have chosen Scopus as the primary database for this study.

The search proceeded using the syntax below:

TITLE-ABS-KEY

((”BRAND*‘AND(’GREEN*‘OR’SUSTAIN*‘)AND’PRACTIC*‘AND’TOUR*”))

The asterisk was included in the query to search for the keywords and their derivatives. Therefore, the query will search the Scopus database in each study’s Title—Abstract - Keyword sections for the simultaneous occurrence of the terms (1) “brand/branding,” (2) “green” or “sustainability/sustainable,” (3) “practice,” and (4) “tourist/tourism.” The term selection is based on Cavalcante de et al. (Citation2021) study on “sustainability and tourism marketing.” However, this research excludes the term “marketing” to concentrate solely on branding activities and includes the term “practice” to refine the results of the previous study further. Additionally, in order to focus on social science and economics, studies from the environment, energy, arts and humanities, engineering, agriculture, mathematics, and materials subject area were also excluded. The search’s syntax is designed to be an unordered combination of chosen terms to prevent ignoring any study regarding “branding tourism places or destinations that employ green or sustainable practices.” Therefore, it is possible that studies on unrelated topics will be included (such as “sustainable branding” or “branding practices”). Thus, the datasets’ documents will be carefully filtered through a data screening procedure to eradicate unsuitable studies before analyses.

The searches were conducted on 31 March 2021 (found 90 documents) and 7 June 2022 (found 112 documents). The two periods’ datasets are generated and exported in.csv format for analysis. The time gap between the two periods is conveniently chosen to examine the subject area expansion speed over a year (14 months). The data collection process applies the guidelines by PRISMA (Haddaway et al., Citation2022) and is effectively employed by Wang et al. (Citation2023), which represents in Figure .

3.2. Data filtering and refining

The documents listed in the datasets will be completely evaluated for compliance with the study requirements. (1) The documents must be full-text articles, book chapters, or conference proceedings papers (books will be excluded due to their broad scope of knowledge). (2) Articles not aligned with the study’s intended topic will be removed. (3) Duplicate documents will also be eliminated to ensure the credibility and validity of the result. Following the filtering process, the 31 March 2021 dataset has 55 valid papers, and the 7 June 2022 dataset has 68 valid papers left.

Besides, the Scopus database is recognized for its inconsistent citation style, which may compromise the accuracy of the co-citation and bibliographic coupling analysis, depending on how many times a study is cited in other research (van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020). As a result, before being evaluated, the datasets will be refined using Openrefine, following the guidelines of Openrefine (Citation2021). The process will (1) synchronize the studies’ citation style and (2) eliminate duplicate references in the same study. Therefore, the procedure will hopefully ensure the accuracy of the reference counting and the analyses.

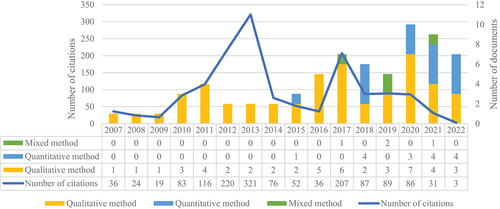

In general, the dataset comprised 68 documents that ranged from 2007 to the times the searches were conducted, demonstrating 15 years of the subject area (detailed in Figure ). It is worth noticing that the primary research method for the subject area is qualitative (48 studies − 70.59%), then quantitative (16 documents − 23.53%), and the mixed-method (4 papers − 5.88%).

In summary, scholars started recognizing the need for sustainable tourism branding research in 2007 with the study of Vitic and Ringer (Citation2007) on branding Montenegro as a sustainable tourism destination post-civil-war. Initially, the subject’s expansion rate was slow and uneven, with only two studies published in 2008 and 2009 by Bell (Citation2008) and Gronau and Kaufmann (Citation2009). However, in the next stage, it witnessed a flourish in published studies and citations in 2012, 2013, and 2017. Most citations of this period come from the contribution of Lockshin and Corsi (Citation2012) −213 citations; Braun et al. (Citation2013) −313 citations; and Büscher and Fletcher (Citation2017) −85 citations; the referenced papers are also the most cited documents in the datasets. Since 2017, research documents have been published consistently each year, reaching a peak of ten papers in 2020. Although the publication number witnessed a small decline to nine papers in 2021, it is worth noting that in only the first five months of 2022, seven papers have been published on this subject, with equal use of qualitative and quantitative methodologies. It is safe to say that the topic of sustainable tourism branding is rapidly developing and merits researchers’ attention. Also, it is acknowledged that although 68 documents in the datasets are on the same subject of “sustainable tourism branding,” they employ different approaches to the subject area, illustrating various topics and subtopics, which will be thoroughly addressed in the latter section of this study.

3.3. The data analyses proceeded using VOSviewer version 1.6.15

VOSviewer is an application for mapping and visualizing the network data of academic publications generated from databases’ files, such as Web of Science, Scopus, Dimensions, and PubMed (van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020). VOSviewer has been proven to be an appropriate bibliometric analysis program (van Eck & Waltman, Citation2010). It has been used in systematic review studies for green brand equity (Górska-Warsewicz et al., Citation2021), sustainability, and tourism marketing (Cavalcante de et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the study follows the guidelines of van Eck and Waltman (Citation2010), Waltman et al. (Citation2010), and Perianes-Rodriguez et al. (Citation2016) to process:

Citation analysis is a technique that counts and ranks the documents, authors, organizations, journals, and countries based on the number of citations they receive. Datasets from both periods are evaluated separately to provide an overview of the subject area and its evolution across 14 months. Besides, the studies will also present the top cited documents, authors, organizations, journals, and countries, illustrating their contributions to the research topic.

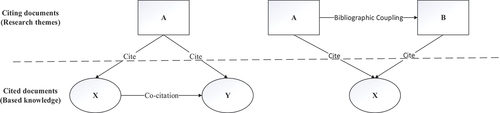

Co-citation analysis will identify publications cited at least three times by the dataset’s studies and connect them based on the number of times they have been cited together. If studies are frequently cited jointly in other papers, they may be related and can serve as a foundation of knowledge for the citing documents (Small, Citation1973). Therefore, a co-citation analysis on the June 7, 2022 dataset has been performed to investigate the core studies, which provide basic knowledge for researchers to take the first step toward the selected topic. Moreover, according to Mustafee, Katsaliak and Fishwick (Citation2014), many studies might refer to general books due to their expansive content, which would influence the cluster formation in the result and complicate their interpretation. Therefore, the study decided to exclude books from the result and place them into a separate section. This approach was also employed in previous co-citation analysis studies (Acedo & Casillas, Citation2005; Schildt et al., Citation2006).

Co-occurrence analysis based on keywords focuses on counting and analyzing the relation among author-defined and indexed keywords. The algorithm will look for keywords that appear more than twice across documents and group them into clusters based on how frequently they appear together (van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020). Therefore, a co-occurrence analysis was carried out on the June 7, 2022 dataset to determine the current research trend in the topic field via keyword presentation. Such practice has been applied in previous research (Narong & Hallinger, Citation2023; Zhao, Citation2022).

Bibliographic coupling analysis employs the shared references between two documents to assess their similarities (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). The key assumption is that if documents cite the same based studies, they might share the same topic (Cavalcante et al., 2021). Therefore, a bibliographic coupling analysis is performed on the June 7, 2022 dataset to delve deeper into the main themes of the designated research field. The documents’ minimum citation requirement is set to zero to avoid leaving out any research. However, there is a possibility that several documents will be unable to link with other studies due to their different approaches and reference documents, despite having the same theme. Hence, the authors will manually evaluate each document to discover the themes of the clusters and allocate any studies that the algorithm can not link to the clusters based on their contents.

Finally, according to Perianes-Rodriguez et al. (Citation2016), the fractional counting method is used rather than the full counting method to assure the accuracy of the analyses. The differences between co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling are illustrated in Figure .

Figure 3. Co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling adapted from Zupic and Čater (Citation2015).

4. Result

4.1. The citation analysis

4.1.1. The top cited papers

In 14 months, the total number of research in the designated subject area has risen by 13 documents, roughly equivalent to one paper per month on average. Table displays the top five publications in terms of citations, demonstrating their contribution to the subject area. It is essential to observe that the rankings of the studies have changed between the two time periods.

Table 1. The top five most cited papers

On the positive side, Braun et al. (Citation2013) - also one of the topic’s foundation studies, demonstrated multiple roles of residents in sustainable place branding. Stay firmly second place, the study by Lockshin and Corsi (Citation2012) illustrates sustainable and green practices’ effects on wine tourism’s brand.

On the negative side, Büscher and Fletcher (Citation2017) describe the capitalist tourism practices that destroy the destination’s infrastructure but are concealed by branding efforts. Smith and Font (Citation2014) also reveal the reality of greenwashing in volunteer tourism. Furthermore, Grydehøj and Kelman (Citation2017), which previously ranked fifth in terms of citations, criticize the eco-label system, as tourism destinations have been compelled to practice symbolic sustainable activities, also known as conspicuous sustainability, in order to pursue such standards.

Additionally, the current rank fifth in citations, the study of Jarvis et al. (Citation2010) presents the case of the Green Tourism Business Scheme (GTBS), which offers a set of criteria for evaluating the environmental practices of tourism businesses. The study also investigates the benefits of joining the GTBS.

The top cited authors and organizations are displayed in Tables ; their positions have remained unchanged over the past 14 months. During the mentioned duration, an increase of 32 authors and 30 organizations contributing to the topic has been observed. The top cited authors are experts in tourism, destination branding, and beverage marketing, with numerous citations.

Table 2. Top five authors in terms of citations

Table 3. Top five organizations that contributed to the field of research in terms of citations

The top cited journals and countries are detailed in Tables . The top journals in terms of citations are Scopus Q1 journals with significant citescores in diverse subject areas, including Economics, Business, Marketing, and Tourism—Hospitality management. It is observed that the Journal of Sustainable Tourism surpassed Wine Economics and Policy after 14 months due to the addition of two new studies and 87 additional citations. Eleven journals and five countries participated in the topic research between the timeframes.

Table 4. The top journals that contributed to the field of research in terms of citations

Table 5. The top five countries that contributed to the field of research in terms of citations

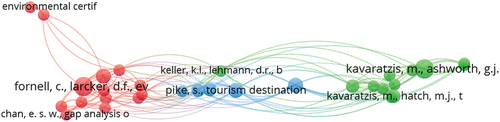

4.2. The foundation studies exploring through co-citation analysis

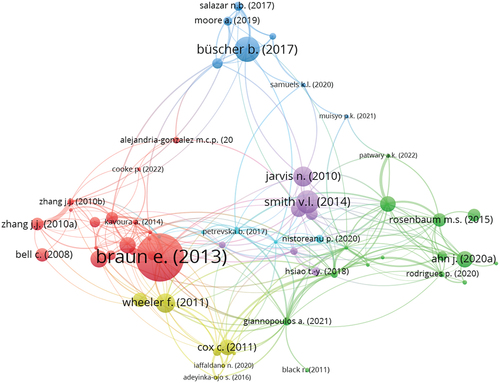

The co-citation analysis results in 31 based studies, which are divided into three clusters (detailed in Figure ): (1) Foundation studies for sustainable tourism branding research, (2) The application of traditional branding literature to place branding, (3) Tourism destination branding. Additionally, the books are placed in a separate section, as aforementioned, to ensure the accuracy of cluster interpretation.

4.2.1. Cluster 1 - Foundation studies for sustainable tourism branding research (14 documents)

The studies of this group belong to one of three sub-topics:

Research that defines concepts and frameworks for assessing marketing concepts from the standpoint of customers, such as perceived quality, value (Zeithaml, Citation1988), customer-based brand equity (Boo et al., Citation2009), destination brand equity (García et al., Citation2012).

Studies on research methods, including the study of Chan (Citation2013), analyze gaps in green tourism marketing, which are still being used in contemporary studies. Furthermore, it is critical to consider Gartner’s (Citation2014) proposal on the method to calculate brand equity and sustainable development. This collection also includes studies on the structural equation model method, which is frequently employed in marketing research (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Studies demonstrate the relationship among factors in tourism branding research, such as the Robinot and Giannelloni (Citation2010) efforts to assess the green attributes’ impacts on customer satisfaction. Han et al. (Citation2009) employ the Theory of Planned behavior to provide empirical evidence of perceived green practices’ impact on customer attitudes and behavior. Additionally, Aro et al. (Citation2018) investigate the antecedents of brand components and their influences on customers’ emotional and behavioral intentions.

Studies on tourism sustainable development policies, such as the environmental certification system and its application (Font, Citation2002), and applied sustainable development in tourism activities (Sharpley, Citation2000).

4.2.2. Cluster 2 - The application of traditional branding literature to place branding (12 documents)

This cluster begins with the branding literature, which can be summarized in the study of Keller and Lehmann (Citation2006). Soon after, traditional corporation branding was applied to place branding, resulting in the identification of two approaches: the urban planning approach and the tourism approach (Hankinson, Citation2004). This cluster represents the place and city branding approach, which focuses predominantly on the branding process and includes destination brand identity, brand positioning and brand image (Kavaratzis, Citation2004; Kavaratzis & Ashworth, Citation2005). The studies of Papadopoulos (Citation2004) and Dinnie (Citation2004) provide an overview of place branding’s concept, components, strategy and implications. The effectiveness of place branding depends on its relationships with various stakeholders, including primary services, infrastructure, the media, and consumers (Ashworth & Kavaratzis, Citation2009). While Warnaby (Citation2009) chooses the service-dominant approach in branding, Braun et al. (Citation2013) delve into residents’ roles, such as being a part of the brand, brand promoters, and voters in the political context. Therefore, it makes sense to include stakeholders in place and city branding activities (Kavaratzis, Citation2012). However, it is important to acknowledge that city branding practices are sensitive and politically dependent activities (Braun, Citation2012). Finally, Kavaratzis and Hatch (Citation2013) link place branding and identity through a succession of communications with stakeholders.

4.2.3. Cluster 3 - Tourism destination branding (5 documents)

It is acknowledged that the third cluster’s studies reside in the category of the tourism marketing approach, as designated by Hankinson (Citation2004). First, it is essential to understand the role of stakeholders in the tourism destination policy-making process (Bramwell & Sharman, Citation1999). Additionally, the destination marketing literature, including stakeholders’ relationships, strategies and practices, is summarized by Buhalis (Citation2000). From the practical standpoint, Kotler and Gertner (Citation2002) proposed that marketing practitioners should employ SWOT analysis to identify unique qualities and focus all marketing and branding efforts in the same direction to maintain consistency of place branding operations. Furthermore, the effectiveness of cooperative branding has been demonstrated in several cases of rural tourism destinations (Cai, Citation2002). However, the application of theory to practice has been hindered by destination marketing organizations’ inability to encapsulate the multifaceted nature of destinations in a condensed brand position (Pike, Citation2005).

4.2.4. The books cluster—excluded from co-citation analysis (14 documents)

Table represents books that the study excluded from co-citation analysis to maintain the cluster result’s straightforwardness. These documents, however, still represent the main themes mentioned above.

Table 6. Books that are excluded from the co-citation analysis

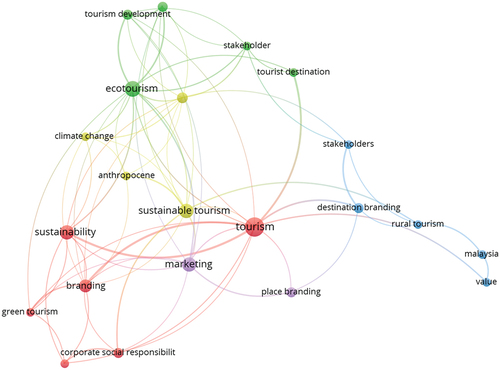

4.3. The co-occurrence analysis

The result is five keyword clusters (Figure and Table ). From this, several themes have been suggested as follows: Cluster 1 (red) represents the studies exploring the impact of Corporate social responsibility in green and sustainable tourism development, which affects its branding strategy and brand equity. Cluster 2 (green) illustrates the sustainable tourism development strategy research, which closely attaches to ecotourism. Cluster 3 (blue) demonstrates a recent focus on sustainable rural tourism development and its effects on destination branding; unsurprisingly, Malaysia is a primary example of green tourism development with four studies in the dataset. Cluster 4 (yellow) focuses on the Anthropocene theme in green and sustainable tourism, which exhibits the negative impacts of human activities on the environment and their consequences. Cluster 5 (purple) represents the tourism marketing and place branding studies, which consider multiple aspects of a place, such as economic, socio-political and cultural development, not necessarily using the tourism approach.

Table 7. Keyword clusters resulted from the co-occurrence analysis

4.4. The research topics explored through bibliographic coupling analysis

Among 68 documents, 62 have been categorized into six clusters representing the six main themes of the subject area (Figure ). The remaining six documents are manually placed in the suitable cluster by the authors based on their contents.

Cluster 1 illustrates “The knowledge of place and destination branding from the sustainable development approach.” Although place and destination branding concepts share a number of similarities and are often mentioned together in research, some distinctions between them exist (Hanna et al., Citation2021). On the one hand, destination branding views a location as a tourism opportunity and directs its branding efforts accordingly (Zenker & Martin, Citation2011). On the other hand, place branding adopts a more general approach, which aims to construct and sustain a place’s identity through supporting its infrastructure, marketing activities (e.g., events, stories), cooperation organizational system, and any symbolic presents (Jelinčić et al., Citation2017).

The first sub-group of the cluster provides in-depth knowledge of place branding (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2015; Zhang, Citation2010b), and its application to city branding (Alejandria-Gonzalez, Citation2016; Biçakçi & Genel, Citation2017; Braun et al., Citation2013; Campelo, Citation2021; Gold & Gold, Citation2012; Jelinčić et al., Citation2017; Kavoura & Bitsani, Citation2014; Knott et al., Citation2016; McCarthy & Wang, Citation2016).

The second sub-group investigates the effects of a variety of factors on destination branding, such as landscape (Doxiadis & Liveri, Citation2013; Vela de et al., Citation2017), event management (Van Niekerk, Citation2017), cultural participation (Cooke et al., Citation2022; Vitic & Ringer, Citation2008; Zhang, Citation2010a). Besides, several attempts at destination branding without considering the residents, socioeconomic factors (Klingmann, Citation2022), or over-promotion but lack of actual practices have also been examined (Bell, Citation2008).

Cluster 2 represents “The sustainable practice of the marketing and branding approach,” which is divided into three sub-groups:

First, from a marketing standpoint, it is essential to comprehend the effect of destination activities on its brand. The studies in this sub-group focus on enhancing customers’ experience through innovation in service (Aksoy, Alkire, Choi, Kim & Zhang, Citation2019), green service ecosystem (Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021; Malik et al., Citation2022), or technology inspiration through employing augmented reality (Huang & Liu, Citation2021). Others concentrate on green marketing, including information and communication technology (Janjua et al., Citation2022; Milman et al., Citation2021); green marketing (Rosenbaum & Wong, Citation2015); green e-WOM (Quoquab et al., Citation2021); green wash (Malik et al., Citation2022); or customers’ perception of the destination CSR activities (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020a; Rodrigues et al., Citation2020).

The second sub-group includes studies that show the impact of sustainable tourism development practices on customer behavior, such as customers’ perceived social and altruistic value (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020b); perceived CSR and green brand trust (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020a); perceived sustainable practices (Milman et al., Citation2021); and green marketing (Chin et al., Citation2018; Patwary et al., Citation2022).

The third sub-topic focuses on the influence of green and sustainable practices on the marketing and branding activities of hotels (Rosenbaum & Wong, Citation2015), tourism entrepreneurs (Alonso-Almeida & Alvarez-Gil, 2018), homestay (Chin et al., Citation2018; Patwary et al., Citation2022), and theme park (Milman et al., Citation2021).

In a number of instances, the branding strategy is also essential for communicating and supporting the area’s sustainable management (Black & Thwaites, Citation2011; Jankovic et al., Citation2019).

Cluster 3 illustrates “The current status and challenges in sustainable tourism development,” which is also divided into three small sub-topics:

Initially, it is crucial to comprehend the unsustainable nature of tourism activities, such as destination violence and capitalism (Büscher & Fletcher, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2022), but destination branding efforts can be used to cover this reality (Salazar, Citation2017).

On the brighter side, the tourism sustainable practices in Human resource management (Muisyo et al., Citation2021) and destination conservative (Hosseini et al., Citation2021; Samuels & Platts, Citation2020) are proven to be effective marketing and communication tools. However, the practices should avoid the conspicuous sustainability trap, which is carried out solely to meet the eco-brand standard (Grydehøj & Kelman, Citation2017).

Besides, the Anthropocene image can serve as a message of caution and attract tourists to support the sustainability approach (Moore, Citation2015, 2019)

Cluster 4 represents “The collaboration and co-creation in sustainable tourism development and branding.” It is acknowledged that stakeholders collaboration has various strategic benefits, such as maintaining the sustainability in general management (Adeyinka-Ojo & Nair, Citation2016), shaping culture and employee performance (Chigora, Citation2019), participating in strategic planning (Presas et al., Citation2011), marketing (Cox & Wray, Citation2011), and branding (Iaffaldano & Ferrari, Citation2020; Perkins et al., Citation2020; Wheeler et al., Citation2011).

Cluster 5 demonstrates “The Branding activities for different types of sustainable tourism models,” such as agro-food tourism Choo and Park (Citation2018), rural tourism (Gronau & Kaufmann, Citation2009; Matos & Barbosa, Citation2018), gastronomy tourism (Rinaldi et al., Citation2020), wine tourism (Lockshin & Corsi, Citation2012), culture tourism (Bohne, Citation2021; Koumara-Tsitsou & Karachalis, Citation2021; Taheri et al., Citation2018), volunteer tourism (Smith & Font, Citation2014), certified green tourism (Jarvis et al., Citation2010), and luxury tourism (Athwal et al., Citation2019).

Cluster 6 shows “The Impacts of tourism sustainable development’s stakeholders in branding,” such as community (Chigora et al., Citation2020; Šagovnović et al., Citation2022), tradition (Koumara-Tsitsou & Karachalis, Citation2021), policy and assessment criteria from the government (Petrevska & Cingoski, Citation2017; Visković, Citation2020), and non-government (Nistoreanu et al., Citation2020).

The summarized result is illustrated in Table .

Table 8. The main topics and sub-topics groups

5. Discussion and future research agenda

This study provides a systematic review of the subject of branding sustainable tourism destinations. Using a reputable academic database such as Scopus, the generated dataset is refined per PRISMA and OpenRefine guidelines to construct a research sample of 68 valid papers on the designated subject area from 2007 to June 2023. The documents are then subjected to a series of analyses and manual evaluations to provide an overview of the research field and insight into the future research agenda.

First, the results of the citation analyses based on the citation number of documents, authors, organizations, journals and nations summarize the specified topic. Despite fluctuations in the number of publications, the annual publication rate is rising, with ten papers in 2020 (equivalent to 0.83 paper/month), nine papers in 2021 (equivalent to 0.75 paper/month), and seven papers in only half of 2022 (equivalent to 1.17 paper/month). Additionally, the number of citations for the most cited documents in the dataset is gradually increasing, with Braun et al. (Citation2013) receiving 71 additional citations in 14 months, Lockshin and Corsi (Citation2012) receiving 44 additional citations, and a new study such as Ahn and Kwon (Citation2020b) receiving 19 citations in the time gap. Therefore, it is reasonable to imply that the topic of sustainable tourism branding destinations is a potential and promising research direction. Besides, the lack of quantitative and mixed-method research on the mentioned subject has also been witnessed (20 studies − 29.4%). This creates a research gap for researchers to fill in.

Second, to set the first step into the designated subject area, researchers can consider the findings of the co-citation analysis. The findings illustrate four document clusters and a collection of books that serve as the field’s foundational knowledge. It is important for scholars to understand the traditional branding literature and how it applies to place and destination branding (Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006); the difference between place and destination branding approach (Hankinson, Citation2004); or how the practices of sustainable development policies (Bramwell & Sharman, Citation1999; Font, Citation2002) link with place and destination branding (Sharpley, Citation2000), and also understand its challenges (Pike, Citation2005). Additionally, knowledge of several concepts of tourism, marketing, and branding is also provided (Boo et al., Citation2009; García et al., Citation2012; Zeithaml, Citation1988), as well as research methodology studies from both qualitative (Yin, Citation2009) and quantitative approach (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Chan, Citation2013; Cohen, Citation2013; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Gartner, Citation2014; Hair et al., Citation2014, Citation2014; Henseler et al., Citation2015).

The third contribution came from the result of the co-occurrence analysis in identifying current research themes. Based on the findings of co-occurrence analysis, three keyword clusters related to the indicated topic have been found. Cluster 1 represents the brand equity concept in the context of sustainable tourism development, in consideration of corporate social responsibility (Chigora, Citation2019; Iaffaldano & Ferrari, Citation2020; Janjua et al., Citation2022; Malik et al., Citation2022; Rosenbaum & Wong, Citation2015). Cluster 3 illustrates rural tourism destinations’ branding, which considers the destination’s value and stakeholders (Adeyinka-Ojo & Nair, Citation2016; Chin et al., Citation2018; Wheeler et al., Citation2011). Cluster 4 focuses on the Anthropocene theme as a marketing opportunity for sustainable tourism destinations’ branding tool (Moore, Citation2015, 2019). The mentioned clusters represent the potential research direction scholars could employ in their future studies.

Fourth, the bibliographic coupling analysis result demonstrates six general main topics, among which, several gaps can be provided. One potential research direction is to investigate the impact of various sustainable tourism activities on the destination brand (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020b; Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021; Huang & Liu, Citation2021; Janjua et al., Citation2022; Malik et al., Citation2022; Milman et al., Citation2021; Quoquab et al., Citation2021; Rodrigues et al., Citation2020), or the tourists’ organization brand (Janjua et al., Citation2022; Milman et al., Citation2021); or customers’ intention and behavior in such context (Ahn & Kwon, Citation2020a; Milman et al., Citation2021; Patwary et al., Citation2022). From this approach, future research might diversify research methodology (Patwary et al., Citation2022), considering the stakeholder participation in the post-Covid-19 era (Janjua et al., Citation2022; Reindrawati, Citation2023), and investigating different aspects of brand equity (Malik et al., Citation2022). Additionally, it is acknowledged that there is only a small number of sustainable tourism destination’s brand equity research among the dataset’s studies (5 studies − 7.35%), not to mention from the quantitative approach (3 studies − 4.41%). Therefore, it is critical to execute more studies following this direction, which applies various sustainable tourism models that link closely to the green supply chain and value (Liu et al., Citation2017; Pan et al., Citation2018).

From the perspective of collaboration and co-creation in sustainable tourism development and branding, it is important to understand the critical branding participation of different types of stakeholders (Iaffaldano & Ferrari, Citation2020; Perkins et al., Citation2020; Yuliati et al., Citation2023) and their impact on branding strategies (Chigora et al., Citation2020; Koumara-Tsitsou & Karachalis, Citation2021; Nistoreanu et al., Citation2020; Šagovnović et al., Citation2022; Visković, Citation2020). Following this path, a number of recommendations are also made, such as exploring both tourists’ and stakeholders’ perspectives on operation (Klingmann, Citation2022); delving into the context of inconsistencies in sustainable practices (Šagovnović et al., Citation2022); or investigating a diverse case of collaboration in sustainable tourism branding (Cooke et al., Citation2022).

Additionally, researchers could think about developing, improving, and implementing various sustainable tourism development models and how these practices affect destination branding (Bohne, Citation2021; Koumara-Tsitsou & Karachalis, Citation2021; Rinaldi et al., Citation2020). It is acknowledged that the academic will benefit as it investigates the impact of diverse sustainable practices on various sustainable tourism models’ branding activities. Following this approach, among the dataset’s studies, rural and agritourism were mentioned, although rarely in 7/68 papers (Chin et al., Citation2018; Choo & Park, Citation2018; Cox & Wray, Citation2011; Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021; Gronau & Kaufmann, Citation2009, Moore, Citation2019; Wheeler et al., Citation2011). This finding is consistent with the result of the co-occurrence analysis, which points to the direction of focusing on the different types of sustainable tourism (Chin et al., Citation2023; Giampiccoli et al., Citation2023), including rural tourism, or its special case—agritourism, as an efficient way to improve the environmental status, ensure the sustainable development and the effectiveness of destination branding strategy (Cluster 3 of co-occurrence analysis). Additionally, Liu et al. (Citation2017) proposed a conceptual paradigm for agri-food tourism that considers both the tourism and agriculture aspects. Moreover, this study has again checked the Scopus database for green and sustainable agritourism branding research. Only seven studies have been found that are related to this topic as Liu et al. (Citation2017) study that has been mentioned above: Matos de’s and Barbosa de (Citation2018) study on authenticity marketing of the case of Brazil’s agritourism; Choo and Park (Citation2018) on agricultural food festivals in Korea; Moore (Citation2019) on Anthropocene-theme to promote sustainable tourism in the Bahamas; Sidali et al. (Citation2019) on the impact of tourism websites factors on customers willing to pay for agritourism; Li et al. (Citation2020) on China’s Important agricultural heritage systems, which aims to conserve traditional agriculture alongside with sustainable development; Giordano (Citation2020) on Italia’s Vico Del Gargano sustainable tourism model. Therefore, this direction represents an opportunity for further research.

This study has some deficiencies, such as the fact that keywords were chosen and refined based on one previous study, as well as only one database was used. In the future, researchers should look into different keyword combinations that this study might have overlooked. In addition, the academic community will benefit from future studies that re-examine the validity of this research using the Web of Science, Google Scholar, and other databases./.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thanh-Binh Phung

Thanh-Binh Phung is a PhD and Lecturer at the Faculty of Business Administration at the University of Economics and Law, Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. His research interests are service marketing, brand management, and tourism marketing.

Doan Viet Phuong Nguyen

Doan Viet Phuong Nguyen* is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Business Administration at the University of Economics and Law, Vietnam National University; and Lecturer at the Faculty Marketing and International Business, Hutech University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. He is specialised in research on television broadcasting, web-based and online media.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165845

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Viel, F. (2011). The field-standardized average impact of national research systems compared to world average: The case of Italy. Scientometrics, 88(2), 599–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0406-x

- Acedo, F. J., & Casillas, J. C. (2005). Current paradigms in the international management field: An author co-citation analysis. International Business Review, 14(5), 619–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2005.05.003

- Adeyinka-Ojo, S., & Nair, V. (2016). Rural tourism destination accessibility: Exploring the stakeholders’ experience. In S. M. Radzi, M. H. M. Hanafiah, N. Sumarjan, Z. Mohi, D. Sukyadi, K. Suryadi, & P. Purnawarman (Eds.), Heritage, culture and society: Research agenda and best practices in the hospitality and tourism industry (pp. 441–446). Taylor & F. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315386980-79

- Ahn, J., & Kwon, J. (2020a). CSR perception and revisit intention: The roles of trust and commitment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(5), 607–623. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-02-2020-0022

- Ahn, J., & Kwon, J. (2020b). Green hotel brands in Malaysia: Perceived value, cost, anticipated emotion, and revisit intention. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(12), 1559–1574. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1646715

- Aksoy, L., Alkire (Née Nasr), L., Choi, S., Kim, P. B., & Zhang, L. (2019). Social innovation in service: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 30(3), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2018-0376

- Alejandria-Gonzalez, M. C. P. (2016). Cultural tourism development in the Philippines: An analysis of challenges and orientations. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(4), 496–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2015.1127194

- Alipour, H., Safaeimanesh, F., & Soosan, A. (2019). Investigating sustainable practices in hotel industry-from employees’ perspective: Evidence from a Mediterranean island. Sustainability, 11(23), 6556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236556

- Alonso-Almeida Del, M. M., & Alvarez-Gil, M. J. (2018). Green entrepreneurship in tourism. In The emerald handbook of entrepreneurship in tourism, travel and hospitality: Skills for successful ventures (pp. 369–386). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78743-529-220181027

- Anholt, S. (2005). Some important distinctions in place branding. Place Branding, 1(2), 116–121. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990011

- Archambault, É., Campbell, D., Gingras, Y., & Larivière, V. (2009). Comparing bibliometric statistics obtained from the Web of Science and Scopus. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(7), 1320–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21062

- Aro, K., Suomi, K., & Saraniemi, S. (2018). Antecedents and consequences of destination brand love — a case study from Finnish lapland. Tourism Management, 67, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.01.003

- Ashworth, G., & Kavaratzis, M. (2009). Beyond the logo: Brand management for cities. Journal of Brand Management, 16(8), 520–531. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550133

- Athwal, N., Wells, V. K., Carrigan, M., & Henninger, C. E. (2019). Sustainable luxury marketing: A synthesis and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(4), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12195

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Baker, B. (2007). Destination branding for small cities: The essentials for successful place branding. Creative Leap books.

- Bell, C. (2008). 100% PURE New Zealand: Branding for back-packers. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766708094755

- Biçakçi, A., & Genel, Z. (2017). A theoretical approach for sustainable communication in city branding: Multilateral symmetrical communication model. In F. Eggers, C. M. Hultman, R. Jones, E. V. Karniouchina, N. K. Malhotra, V. Pascal, S. (Yinghong) Wei, G. Yalcinkaya, & S. Yeniyurt (Eds.), Strategic Place Branding Methodologies and Theory for Tourist Attraction (pp. 41–66). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1793-1.ch004

- Black, R., & Thwaites, R. (2011). The challenges of interpreting fragmented landscapes in a regional context: A case study of the victorian box-ironbark forests, Australia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(8), 971–987. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.586464

- Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2005). Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505274646

- Bohne, H. (2021). Uniqueness of tea traditions and impacts on tourism: The East Frisian tea culture. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-08-2020-0189

- Boo, S., Busser, J., & Baloglu, S. (2009). A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tourism Management, 30(2), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.06.003

- Bramwell, B., & Sharman, A. (1999). Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 392–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00105-4

- Braun, E. (2012). Putting city branding into practice. Journal of Brand Management, 19(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2011.55

- Braun, E., Kavaratzis, M., & Zenker, S. (2013). My city - my brand: The different roles of residents in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331311306087

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

- Büscher, B., & Fletcher, R. (2017). Destructive creation: Capital accumulation and the structural violence of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 651–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1159214

- Cai, L. A. (2002). Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3), 720–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00080-9

- Campelo, A. (2021). Global city branding. In A research agenda for place branding (pp. 101–116). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839102851.00015

- Capstick, S., Whitmarsh, L., Poortinga, W., Pidgeon, N., & Upham, P. (2015). International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 6(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.321

- Cavalcante de, W. Q. F., Coelho, A., & Bairrada, C. M. (2021). Sustainability and tourism marketing: A bibliometric analysis of publications between 1997 and 2020 using vosviewer software. Sustainability, 13(9), 4987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094987

- Chan, E. S. W. (2013). Gap analysis of green hotel marketing. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(7), 1017–1048. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2012-0156

- Cheung, M. F. Y., & To, W. M. (2019). An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 50(December 2018), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.04.006

- Chigora, F. (2019). Branding culture: The missing link between top level managers and general employees in Zimbabwe’s small to medium tourism enterprises. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism & Leisure, 8(4), 1–13.

- Chigora, F., Mutambara, E., Ndlovu, J., Muzurura, J., & Zvavahera, P. (2020). Towards establishing Zimbabwe tourism destination brand equity variables through sustainable community involvement. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism & Leisure, 9(5), 1094–1110. https://doi.org/10.46222/AJHTL.19770720-71

- Chin, C.-H., Chin, C.-L., & Wong, W. P.-M. (2018). The implementation of green marketing tools in rural tourism: The readiness of tourists? Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 27(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2017.1359723

- Chin, S. W. L., Hassan, N. H., & Yong, G. Y. (2023). The new ecotourists of the 21st century: Brunei as a case study. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2191444

- Choo, H., & Park, D.-B. (2018). Potential for collaboration among agricultural food festivals in Korea for cross-retention of visitors. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(9), 1499–1515. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1478418

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statisticalpower analysis for the behavioral Sciences. In Cnbc. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Cooke, P., Nunes, S., Oliva, S., & Lazzeretti, L. (2022). Open innovation, soft branding and green influencers: Critiquing ‘Fast Fashion’ and ‘overtourism’. Journal of Open Innovation, 8(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010052

- Cox, C., & Wray, M. (2011). Best practice marketing for regional tourism destinations. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(5), 524–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.588112

- Dinnie, K. (2004). Place branding: Overview of an emerging literature. Place Branding, 1(1), 106–110. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990010

- Doxiadis, T., & Liveri, D. (2013). Symbiosis: Integrating tourism and Mediterranean landscapes. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(3), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-10-2012-0031

- Falagas, M. E., Pitsouni, E. I., Malietzis, G. A., & Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. The FASEB Journal, 22(2), 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-9492lsf

- Font, X. (2002). Environmental certification in tourism and hospitality: Progress, process and prospects. Tourism Management, 23(3), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00084-X

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge university press.

- García, J. A., Gómez, M., & Molina, A. (2012). A destination-branding model: An empirical analysis based on stakeholders. Tourism Management, 33(3), 646–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.07.006

- Gartner, W. C. (2014). Brand equity in a tourism destination. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 10(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2014.6

- Giampiccoli, A., Mnguni, E. M., Dłużewska, A., & Mtapuri, O. (2023). Potatoes: Food tourism and beyond. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2172789

- Giannopoulos, A., Piha, L., & Skourtis, G. (2021). Destination branding and co-creation: A service ecosystem perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(1), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2504

- Giordano, S. (2020). Agrarian landscapes: From marginal areas to cultural landscapes—paths to sustainable tourism in small villages—the case of Vico Del Gargano in the club of the borghi più belli d’Italia. Quality and Quantity, 54(5–6), 1725–1744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00939-w

- Gold, J. R., & Gold, M. M. (2012). Beijing-London-rio de janeiro: A never-ending global competition. In Handbook of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Volume one: Making the Games (pp. 291–303). Taylor and Francis, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203132517

- Górska-Warsewicz, H. (2020). Factors determining city brand equity—A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(19), 7858. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12197858

- Górska-Warsewicz, H., Dębski, M., Fabuš, M., & Kováč, M. (2021). Green brand equity—empirical experience from a systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(20), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011130

- Groening, C., Sarkis, J., & Zhu, Q. (2018). Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 1848–1866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.002

- Gronau, W., & Kaufmann, R. (2009). Tourism as a stimulus for sustainable development in rural areas: A cypriot perspective. Tourismos, 4(1), 83–96. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-68549110220&partnerID=40&md5=302cdffad44c1b5188ca67e46bccfd91

- Grydehøj, A., & Kelman, I. (2017). The eco‐island trap: Climate change mitigation and conspicuous sustainability. Area, 49(1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12300

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020‐compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230

- Hair, J. F. J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis. In Pearson new international edition (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Journal of Tourism Research, 6(2), 211–213. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v6i2.134

- Han, H., Hsu, L. T., & Lee, J. S. (2009). Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(4), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.02.004

- Hankinson, G. (2004). Relational network brands: Towards a conceptual model of place brands. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670401000202

- Hankinson, G. (2005). Destination brand images: A business tourism perspective. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040510579361

- Hanna, S., Rowley, J., & Keegan, B. (2021). Place and destination branding: A review and conceptual mapping of the domain. European Management Review, 18(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12433

- Hassan, S., & Mahrous, A. A. (2019). Nation branding: The strategic imperative for sustainable market competitiveness. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 1(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhass-08-2019-0025

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Honey, M. (1999). Ecotourism and sustainable development. Who owns paradise?. Island press.

- Hosany, S., Ekinci, Y., & Uysal, M. (2006). Destination image and destination personality: An application of branding theories to tourism places. Journal of Business Research, 59(5), 638–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.01.001

- Hosseini, K., Stefaniec, A., & Hosseini, S. P. (2021). World heritage Sites in developing countries: Assessing impacts and handling complexities toward sustainable tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20(September 2020), 100616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100616

- Hsiao, T.-Y. (2018). A study of the effects of co-branding between low-carbon islands and recreational activities. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(5), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1093466

- Huang, T.-L. T.-L., & Liu, B. S. C. C. (2021). Augmented reality is human-like: How the humanizing experience inspires destination brand love. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 170, 120853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120853

- Iaffaldano, N., & Ferrari, S. (2020). Storytelling as a value co-creation instrument for matera European capital of culture 2019. In K. V. & S. T. (Eds.), 6th International Conference of the International Association of Cultural and Digital Tourism, IACuDiT 2019 (pp. 53–65). Springer Science and Business Media B.V. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36342-0_4

- Jacobs, K., Petersen, L., Hörisch, J., & Battenfeld, D. (2018). Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 203, 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.320

- Janjua, Z. U. A., Krishnapillai, G., & Rehman, M. (2022). Importance of the sustainability tourism marketing practices: An insight from rural community-based homestays in Malaysia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(2), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-10-2021-0274

- Jankovic, M., Jaksic-Stojanovic, A., Vukilić, B., Seric, N., & Ibrahimi, A. (2019). Branding of protected areas and national parks: A case study of Montenegro. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism & Leisure, 8(2), 1–9.

- Jarvis, N., Weeden, C., & Simcock, N. (2010). The benefits and challenges of sustainable tourism certification: A case study of the green tourism business scheme in the West of England. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 17(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.17.1.83

- Jelinčić, D. A., Vukić, F., & Kostešić, I. (2017). The city is more than just a destination: An insight into city branding practices in Croatia. Sociologija i Prostor, 55(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.5673/sip.55.1.6

- Jernsand, E. M., & Kraff, H. (2015). Participatory place branding through design: The case of Dunga beach in Kisumu, Kenya. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 11(3), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2014.34

- Jo Hatch, M., & Schultz, M. (2003). Bringing the corporation into corporate branding. European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 1041–1064. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560310477654

- Jones, A. (1987). Green tourism. Tourism Management, 8(4), 354–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(87)90095-1

- Kautish, P., & Sharma, R. (2019). Value orientation, green attitude and green behavioral intentions: An empirical investigation among young consumers. Young Consumers, 20(4), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-11-2018-0881

- Kavaratzis, M. (2004). From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Branding, 1(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990005

- Kavaratzis, M. (2012). From “necessary evil” to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331211209013

- Kavaratzis, M., & Ashworth, G. J. (2005). City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale, 96(5), 506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00482.x

- Kavaratzis, M., & Hatch, M. J. (2013). The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Marketing Theory, 13(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593112467268

- Kavoura, A., & Bitsani, E. (2014). Investing in culture and intercultural relations for advertising and sustainable development of the contemporary European city within the framework of international city branding and marketing: The case study of the Intercultural Festival of Trieste, Italy. In Lucas, B. (Eds.), Advertising: Types of methods, perceptions and impact on consumer behavior (pp. 35–65). Nova Science Publishers.

- Kazmi, S. H. A., Shahbaz, M. S., Mubarik, M. S., & Ahmed, J. (2021). Switching behaviors toward green brands: Evidence from emerging economy. Environment Development and Sustainability, 23(8), 11357–11381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01116-y

- Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2006). Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25(6), 740–759. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1050.0153

- Keller, K. L., & Swaminathan, V. (2020). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Pearson.

- Klingmann, A. (2022). Re-scripting Riyadh’s historical downtown as a global destination: A sustainable model? Journal of Place Management and Development, 15(2), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-07-2020-0071

- Knott, B., Fyall, A., & Jones, I. (2016). Leveraging nation branding opportunities through sport mega-events. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-06-2015-0051

- Kotler, P., & Gertner, D. (2002). Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540076

- Kotler, P., Haider, D. H., & Rein, I. (1993). Marketing places: Attracting investment, industry, and tourism to cities, States, and Nations. Free Press.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2015). Marketing Management. Pearson Education. https://books.google.com.vn/books?id=PDUOrgEACAAJ

- Koumara-Tsitsou, S., & Karachalis, N. (2021). Traditional products and crafts as main elements in the effort to establish a city brand linked to sustainable tourism: Promoting silversmithing in Ioannina and silk production in Soufli, Greece. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 17(3), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-021-00200-y

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y.-Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y.-P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

- Li, Z., Rao, D., Liu, M., Wang, G., & Ding, L. (2020). Identifying factors driving income difference in China nationally important agricultural heritage systems site based on geographical detectors: Ar Horqin Banner as a case study. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture, 28(9), 1425–1434. https://doi.org/10.13930/j.cnki.cjea.200024

- Liu, S.-Y., Yen, C.-Y., Tsai, K.-N., & Lo, W.-S. (2017). A conceptual framework for agri-food tourism as an eco-innovation strategy in small farms. Sustainability, 9(10), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101683

- Lockshin, L., & Corsi, A. M. (2012). Consumer behaviour for wine 2.0: A review since 2003 and future directions. Wine Economics and Policy, 1(1), 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2012.11.003

- MacCannell, D. (2013). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. University of California Press.

- Malik, G., Gangwani, K. K., & Kaur, A. (2022). Do green attributes of destination matter? The effect on green trust and destination brand equity. Event Management, 26(4), 775–792. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599521X16367300695799

- Matos, M. B. A., & Barbosa, M. L. A. (2018). Marketing and authenticity in tourism: A cacao farm in Brazil. In Tourism social science series (Vol. 24. pp. 53–68). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1571-504320180000024004

- Matos de, M. B. A. A., & Barbosa de, M. L. A. (2018). Marketing and authenticity in tourism: A cacao farm in Brazil. Tourism Social Science Series, 24, 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1571-504320180000024004

- Mayr, P., & Scharnhorst, A. (2015). Scientometrics and information retrieval: Weak-links revitalized. Scientometrics, 102(3), 2193–2199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1484-3

- McCarthy, J., & Wang, Y. (2016). Culture, creativity and commerce: Trajectories and tensions in the case of Beijing’s 798 Art Zone. International Planning Studies, 21(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2015.1114446

- Menon, S., Bhatt, S., Sharma, S., & Crociata, A. (2021). A study on envisioning Indian tourism – through cultural tourism and sustainable digitalization. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1903149

- Milman, A., Tasci, A. D. A., & Panse, G. (2021). A comparison of consumer attitudes toward dynamic pricing strategies in the theme Park context. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 24(3), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2021.1988879

- Moise, M. S., Gil-Saura, I., Šerić, M., & Ruiz Molina, M. E. (2019). Influence of environmental practices on brand equity, satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Brand Management, 26(6), 646–657. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-019-00160-y

- Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Moore, A. (2015). Islands of difference: Design, urbanism, and sustainable tourism in the Anthropocene Caribbean. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 20(3), 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12170

- Moore, A. (2019). Selling Anthropocene space: Situated adventures in sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(4), 436–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1477783

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2007). Destination branding: Creating the unique destination proposition. Routledge.

- Muisyo, P. K., Qin, S., Julius, M. M., Ho, T. H., & Ho, T. H. (2021). Green HRM and employer branding: The role of collective affective commitment to environmental management change and environmental reputation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(8), 1897–1914. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1988621

- Murphy, J. M. (1987). What is branding? In J. M. Murphy (Ed.), Branding: A key marketing tool (pp. 1–12). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-08280-3_1

- Mustafee, N., Katsaliaki, K., & Fishwick, P. (2014). Exploring the modelling and simulation knowledge base through journal co-citation analysis. Scientometrics, 98(3), 2145–2159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1136-z

- Narong, D. K., & Hallinger, P. (2023). A keyword co-occurrence analysis of research on service learning: Conceptual foci and emerging research trends. Education Sciences, 13(4), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040339

- Ndlovu, J., & Heath, E. (2013). Re-branding of Zimbabwe to enhance sustainable tourism development: Panacea or Villain. African Journal of Business Management, 7(12), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM12.1201

- Nistoreanu, P., Aluculesei, A.-C., & Avram, D. (2020). Is green marketing a label for Ecotourism? The Romanian experience. Information, 11(8), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080389

- Openrefine. (2021). Curating data with OpenRefine to visualize them in VOSviewer curating data from Web of Science exporting data from the Web of Science. Universite the Lille. https://ged.univ-lille.fr/nuxeo/nxfile/default/9b2701b4-7b8f-4754-8693-7072ee219706/blobholder:0/tutorial_openrefine_v

- Pan, S. Y., Gao, M., Kim, H., Shah, K. J., Pei, S. L., & Chiang, P. C. (2018). Advances and challenges in sustainable tourism toward a green economy. Science of the Total Environment, 635, 452–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.134

- Papadopoulos, N. (2004). Place branding: Evolution, meaning and implications. Place Branding, 1(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990003

- Patwary, A. K., Mohamed, M., Rabiul, M. K., Mehmood, W., Ashraf, M. U., & Adamu, A. A. (2022). Green purchasing behaviour of international tourists in Malaysia using green marketing tools: Theory of planned behaviour perspective. Nankai Business Review International, 13(2), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-06-2021-0044

- Perianes-Rodriguez, A., Waltman, L., & van Eck, N. J. (2016). Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics, 10(4), 1178–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2016.10.006

- Perkins, R., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Arcodia, C. (2020). Understanding the contribution of stakeholder collaboration towards regional destination branding: A systematic narrative literature review. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 43(March), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.04.008

- Perkumienė, D., Pranskūnienė, R., Vienažindienė, M., & Grigienė, J. (2020). The right to a clean environment: Considering green logistics and sustainable tourism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093254

- Petrevska, B., & Cingoski, V. (2017). Branding the green tourism in Macedonia. Sociologija i Prostor, 55(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.5673/sip.55.1.5

- Pham Hong, L., Ngo, H. T., Pham, L. T., & Coetzee, W. (2021). Community-based tourism: Opportunities and challenges a case study in Thanh ha pottery village, hoi an city, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1926100

- Pike, S. (2005). Tourism destination branding complexity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 14(4), 258–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420510609267

- Postma, A., & Schmuecker, D. (2017). Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2017-0022

- Presas, P., Mũoz, D., & Guia, J. (2011). Branding familiness in tourism family firms. Journal of Brand Management, 18(4–5), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2010.41

- Quoquab, F., Mohammad, J., & Sobri, A. M. M. (2021). Psychological engagement drives brand loyalty: Evidence from Malaysian ecotourism destinations. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2019-2558